Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 95-101 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sarafraz M, Mahmoudi Tabar M, Pourshams M. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Social Effort and Conscientiousness Scale in Schizophrenia Patients. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :95-101

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79152-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79152-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran

2- Department of Psychiatry, Golestan Hospital, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Department of Psychiatry, Golestan Hospital, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Keywords: Factor Analysis [MeSH], Psychometrics [MeSH], Schizophrenia [MeSH], Social Interaction [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 661 kb]

(517 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (620 Views)

Full-Text: (58 Views)

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating mental disorder [1] affecting approximately 1% of the global population across the lifespan [2]. The relatively consistent risk of developing this disorder across diverse geographical and cultural contexts suggests the influence of underlying biological factors. Characterized by a complex interplay of positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms [3], schizophrenia presents with varied manifestations. Positive symptoms involve distortions of reality, such as delusions (fixed false beliefs) and hallucinations (perceptual experiences in the absence of external stimuli). Negative symptoms reflect a diminution or absence of normal functions, including affective flattening (reduced emotional expression), alogia (poverty of speech), avolition (lack of motivation), and anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure). Cognitive symptoms encompass attention, memory, executive functions, and processing speed impairments. These symptom clusters contribute significantly to the substantial social dysfunction frequently observed in individuals with schizophrenia [4]. Diminished social functioning is a hallmark of the disorder [5], impacting various life domains, including interpersonal relationships, occupational performance, and independent living skills [6]. Consequently, impaired social functioning plays a crucial role in predicting the course of illness, risk of relapse, and overall prognosis [7], underscoring the importance of interventions targeting social skills and community integration.

Unemployment and financial hardship, frequently experienced by individuals with schizophrenia, significantly limit opportunities for social interaction and engagement [8], contributing to the erosion of social networks and the weakening of social bonds [9]. These socioeconomic challenges can create barriers to accessing social activities, maintaining stable housing, and participating in community life, further exacerbating social isolation. Social motivation, analogous to general motivation, is a multifaceted construct encompassing reward learning (the process of associating actions with positive outcomes), hedonic experience (the capacity to derive pleasure from rewarding stimuli), and effort computation (the assessment of the cost-benefit ratio of pursuing a goal) [10]. Within social interaction, social motivation specifically pertains to the drive to approach or avoid social stimuli based on their perceived desirability or aversiveness [11]. This involves evaluating the potential rewards of social engagement (e.g., companionship, support, positive feedback) against potential costs (e.g., social anxiety, fear of rejection, past negative experiences). Deficits in any of these components can significantly impair an individual's ability to initiate and maintain meaningful social relationships, further contributing to social dysfunction.

Establishing and maintaining friendships requires a fundamental desire for social connection and engagement, manifested through specific behaviors [12], such as initiating contact, expressing interest in others, and demonstrating reciprocal engagement. Social effort, a crucial component of social motivation, encompasses the behavioral tendencies to actively pursue positive social outcomes (e.g., building relationships, seeking support, engaging in enjoyable activities) or to avoid negative social consequences (e.g., social rejection, conflict, embarrassment) within social communication contexts [12]. This construct highlights the proactive role individuals play in shaping their social experiences. Contemporary psychopathology research increasingly emphasizes approach/avoidance motivation theories [13] as a framework for understanding various behavioral patterns and psychological processes. These theories posit two fundamental motivational systems: An approach system, which promotes engagement with rewarding stimuli and the pursuit of positive goals, and an avoidance system, which promotes withdrawal from threatening stimuli and the prevention of negative outcomes. Within the context of social functioning in schizophrenia, examining the interplay between these systems can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying social withdrawal and isolation.

While social skills training (SST) has demonstrated efficacy in improving interpersonal functioning, adaptive social behavior, and overall quality of life for individuals with various mental health conditions, including schizophrenia [14], the concept of social effort and its measurement have received comparatively less attention [15]. SST interventions typically teach specific social skills, such as initiating conversations, expressing emotions, and resolving conflicts. This relative lack of focus on social effort (the willingness to invest energy and resources in social interactions) represents a significant gap, as it may be a crucial factor influencing the effectiveness of SST and the overall trajectory of social recovery.

The Social Effort and Conscientiousness Scale (SEACS) has been previously validated and has demonstrated associations with depressive symptoms and comorbid anxiety [12], suggesting its relevance to affective and motivational processes. This scale is valuable for assessing individuals' willingness to invest effort in social interactions and adhere to social norms. A recent study validating the SEACS in individuals with schizophrenia [16] provided crucial insights into the role of social effort in this population, revealing a significant correlation between heightened social effort and improved social functioning, as well as an inverse relationship between social effort and the severity of negative symptoms. However, while this study [16] provided initial evidence of the SEACS's utility in schizophrenia, it did not examine the psychometric properties of the SEACS in diverse cultural contexts. Specifically, the psychometric properties of the Persian language version of the SEACS had not been established. Furthermore, the absence of a culturally adapted instrument can hinder accurate assessment and limit the applicability of research findings across different populations. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation are essential in ensuring that psychological instruments are culturally relevant and psychometrically sound when used in different linguistic and cultural groups. Given the absence of research investigating the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the SEACS in individuals with schizophrenia in Iran, this study evaluated these properties within this specific population.

This study addressed a critical gap in the literature by providing a validated Persian SEACS for use with Iranian individuals experiencing schizophrenia, enabling more culturally sensitive and accurate assessments of social effort and conscientiousness.

Instrument and Methods

Design and participants

This study employed a cross-sectional correlational design to examine 83 Iranian adults diagnosed with schizophrenia and receiving treatment at Golestan, Salamat, and Sina medical centers in Ahvaz City in 2023. The sample size was determined a priori using a power analysis conducted with G*Power software. Based on an estimated medium effect size (Cohen’s f²=0.15), a desired power of 0.80, and an alpha level of 0.05, the power analysis indicated a sample size of 83 would provide adequate statistical power to detect significant relationships among the variables of interest. Participants were selected through purposive sampling. The research team collaborated with the medical centers to identify potential participants meeting the inclusion criteria: A diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [17]; Illness duration within five years of diagnosis; Age between 18 and 65 years; And current receipt of medication and psychotherapy. Trained research assistants approached potential participants during routine medical center visits, providing detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and participant rights. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals. Exclusion criteria included: A diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or a related disorder; A diagnosis of major depressive disorder; A diagnosis of a substance use disorder; Unwillingness to participate; Or self-reported drug use within the past month. The final sample comprised 83 participants who met all inclusion and exclusion criteria and completed the study procedures.

Instrument

The Social Effort and Conscientiousness Scale (SEACS): The SEACS, developed by Abplanalp et al. in 2022 [12], employs a six-point Likert scale ranging from "very strongly disagree" to "very strongly agree". The SEACS comprises two subscales: Social effort (8 items) and social conscientiousness (4 items). The original 17-item version included filler items, and one item was subsequently removed by the developers due to insufficient item performance, resulting in the 12-item version used for analysis. Lower SEACS scores indicate greater impairment in social effort and conscientiousness. Abplanalp et al. [12] established the content validity of the SEACS, defining it as encompassing both general social effort and social effort in adherence to social norms. Their research, conducted on two college student samples, found no significant gender differences in SEACS scores but revealed differences based on race and age categories, suggesting that the SEACS is a reliable and valid measure of social effort and conscientiousness. Furthermore, lower SEACS scores were associated with increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, highlighting the scale's potential utility in clinical populations.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): The PANSS, developed in 1986, is a widely used instrument for assessing the severity of positive and negative symptoms in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia [18]. It comprises several subscales measuring distinct symptom dimensions. Two studies conducted in Iran reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.8 [19] and 0.77 [20] for the PANSS, indicating acceptable internal consistency. These values suggest that the items within the Iranian versions of the PANSS consistently measure the intended constructs of positive and negative symptoms.

The Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ): The SFQ assesses an individual's social performance over the past two weeks across several domains, including home life, work (or other productive activity), financial management, family relationships, sexual relationships, social relationships, and leisure activities [21]. The reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients for this scale are 0.77 [22]. A Cronbach's alpha of 0.77 suggests good internal consistency for the SFQ in the samples where it was measured [22]. This indicates that the items within the SFQ consistently measure the intended construct of social functioning.

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS): The CDSS is a specific instrument designed to assess depressive symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia and distinguish them from negative symptoms. Comprising nine items, the CDSS was developed by Addington et al. in 1992 [23]. Confirmatory factor analysis has demonstrated that the CDSS exhibits a unidimensional structure, measuring a single underlying construct of depressive severity consistently across both inpatient and outpatient settings. It has also been established as a reliable instrument for assessing depression in both acute and residual phases of schizophrenia. The validity and reliability of the CDSS have been investigated and confirmed in Iranian samples [24].

Procedure

The questionnaire underwent a forward-backward translation process. Initially, two independent translations from English to Persian were conducted by two English language experts, one with expertise in psychology. Discrepancies between these translations were resolved through discussion and consensus, resulting in a preliminary Persian version. Subsequently, two different English language experts back-translated this Persian version into English. A meeting was then convened by a psychiatrist, a psychologist, and the translators to compare the original English version with the back-translated version. Following this review, the final Persian version was presented to five psychiatrists and psychologists to assess the overall structure and clarity of the questions. Additionally, ten individuals with schizophrenia reviewed the questionnaire to ensure its comprehensibility. The final Persian version of the questionnaire was finalized based on the feedback received.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27 and SmartPLS version 3 software. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to assess the construct validity of the SEACS, examining the hypothesized relationships between the scale's items and its underlying factors. CFA was deemed appropriate as it allows testing a pre-defined theoretical model of the factor structure. Model fit was evaluated using several indices, including the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and the comparative fit index (CFI). Factor loadings were also examined, reflecting the strength of the relationship between each item and its respective factor. Convergent validity, the extent to which the scale correlates with other measures of the same construct, was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE). An AVE value of 0.5 or greater is generally considered acceptable, indicating that the variance explained by the latent construct is greater than the error variance. Discriminant validity, the extent to which the scale does not correlate with measures of different constructs, was examined using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) and the Fornell-Larcker criterion. HTMT is considered a more robust measure of discriminant validity than the Fornell-Larcker criterion. An HTMT value below 0.90 suggests adequate discriminant validity. These analyses, comparing the SEACS with the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), evaluated whether the SEACS measures a construct distinct from these other measures. Reliability, the consistency of the scale's measurements, was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (α) and composite reliability. Cronbach's alpha assesses the internal consistency of the items within each scale/subscale, while composite reliability is an alternative measure of internal consistency, especially relevant in structural equation modeling. Values of 0.70 or higher are generally considered acceptable for both Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, indicating good internal consistency.

Findings

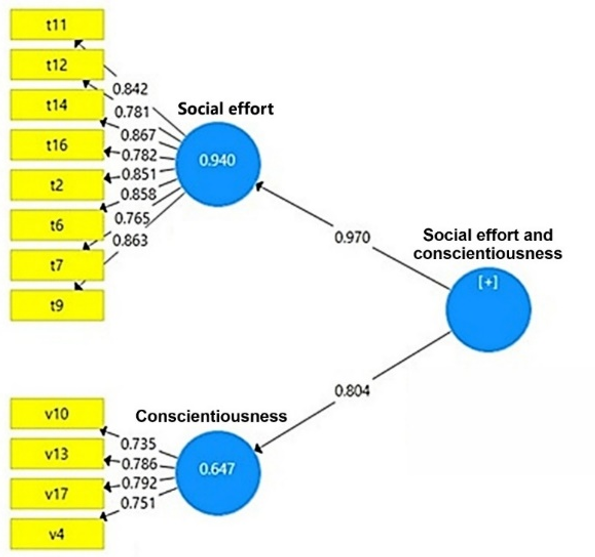

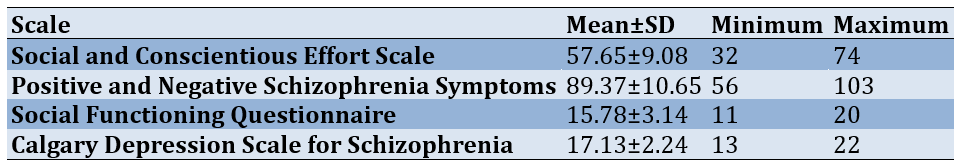

Eighty-three individuals with schizophrenia (55 men and 28 women) participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 39.71±10.38 (18 to 65) years (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive findings related to queSstionnaires

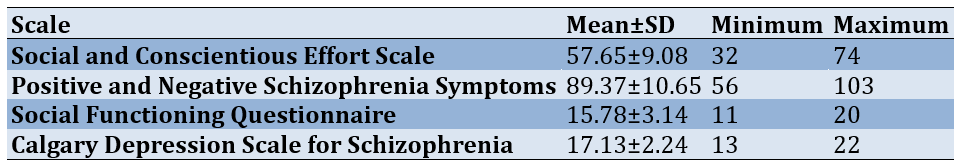

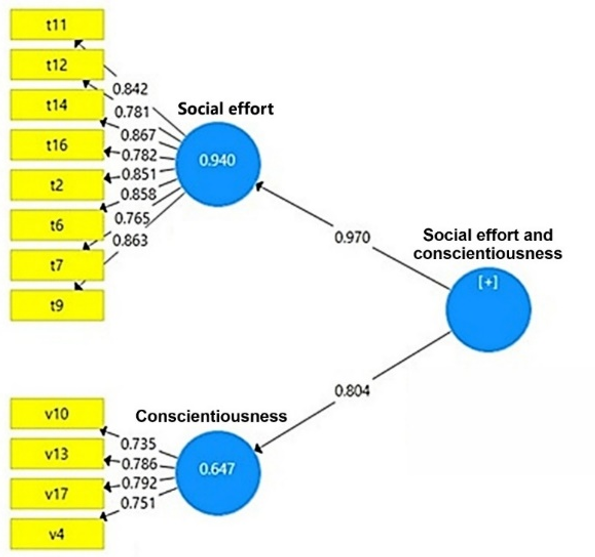

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the SEACS's construct validity (Figure 1). The hypothesized model demonstrated acceptable fit, as indicated by a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of 0.067 and a comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.94.

Figure 1. The hypothesized construct validity model of the questionnaire

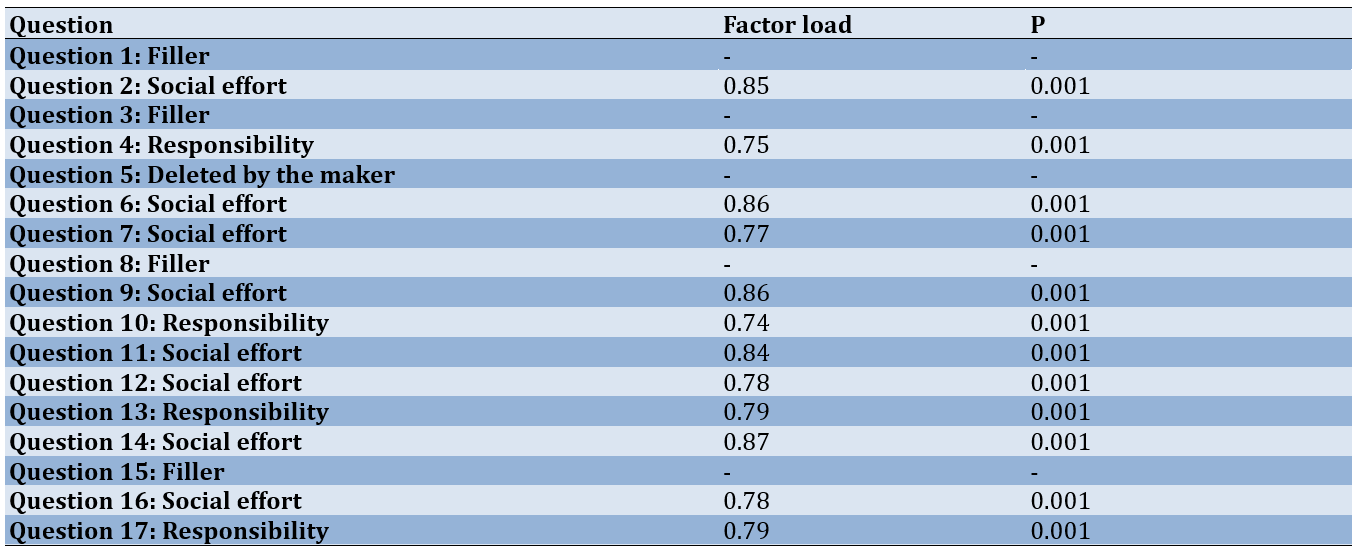

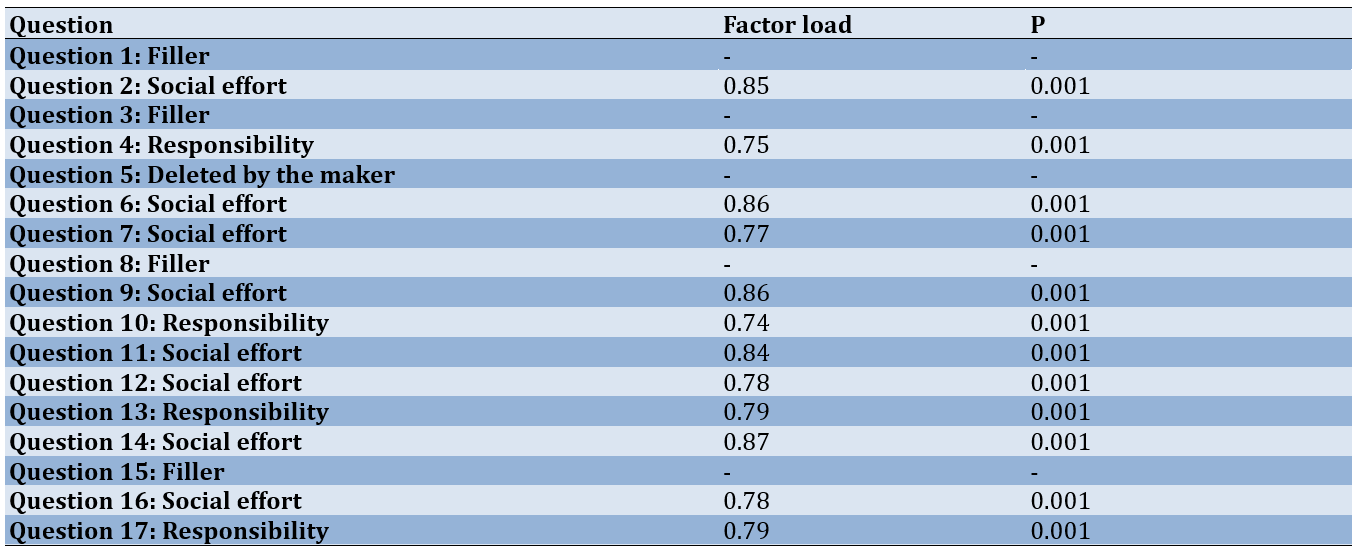

Of the original 17 items, the scale developers removed one due to insufficient item performance, and four were designated as filler items. Consequently, 12 items were retained for analysis. As shown in Table 2, all retained items exhibited factor loadings exceeding 0.4 (Table 2).

Table 2. Factor loadings for questionnaire items

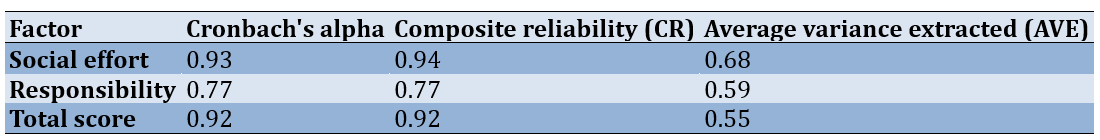

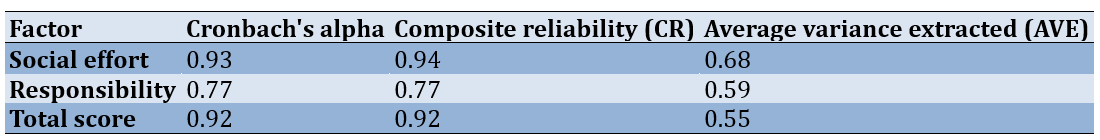

Reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (α) and composite reliability (Table 3). The Cronbach's α values for the overall questionnaire and its subscales were satisfactory, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Furthermore, the composite reliability values for the overall questionnaire and its subscales were also satisfactory, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the 0.5 threshold. According to Fornell & Larcker [25], convergent validity is established when composite reliability (CR) exceeds AVE, AVE exceeds 0.5, and CR exceeds 0.7. As these criteria (CR>AVE, AVE>0.5, and CR>0.7) were met, convergent validity was confirmed.

Table 3. Reliability, composite reliability, and average variance extracted

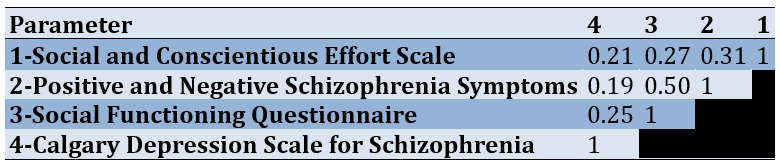

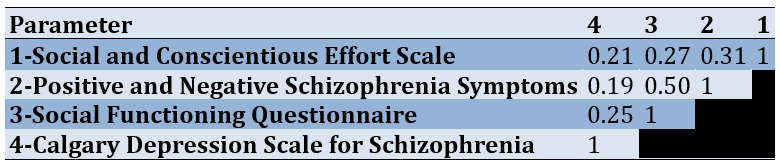

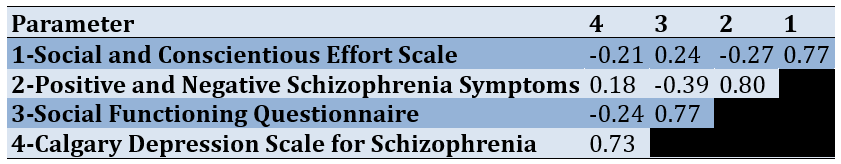

Discriminant validity assesses the extent to which a construct is distinct from other conceptually unrelated constructs. This study evaluated discriminant validity using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT), a robust and widely accepted index for this purpose [26]. While the HTMT criterion has gained prominence and is considered a more reliable alternative, both the HTMT and the traditional Fornell-Larcker criterion were employed and are reported here to provide comprehensive evidence. An HTMT value below 0.9 indicates acceptable discriminant validity. The HTMT calculation, based on the Monte Carlo simulation method, is considered a reliable approach for assessing discriminant validity [26]. Specifically, discriminant validity is established if all pairwise HTMT values between reflective constructs are below 0.9. The Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) were used to assess the discriminant validity of the SEACS (Table 4).

Table 4. HTMT coefficients for the social effort and conscientiousness scale (overall score) with three other scales

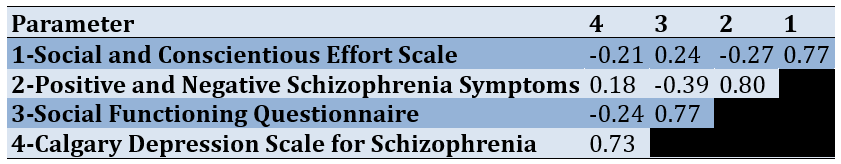

Consistent with the HTMT results (where all values were below 0.9), the Fornell-Larcker criterion supports discriminant validity. The diagonal elements of the Fornell-Larcker matrix represent the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct. In contrast, the off-diagonal elements represent the correlations between constructs. Because the AVE square roots on the diagonal were greater than the inter-construct correlations in the off-diagonal elements, discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. Therefore, the discriminant validity of the SEACS (overall score) was established (Table 5).

Table 5. Fornell-Larcker criterion results for the social effort and conscientiousness scale

Discussion

This study investigated the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the SEACS among individuals with schizophrenia. Given that social functioning is often an important treatment goal and outcome for people with schizophrenia. Since people with schizophrenia often have poorer social functioning [5], also considering the potential role of social effort in creating social disorder [12], it is important and necessary to have an instrument with satisfactory psychometric properties that assess the domain of social effort. This is the first study to examine the psychometric properties of the Farsi version of the SEACS. In summary, the findings indicate that the Persian version of the SEACS demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties and is a valid instrument for assessing social effort and conscientiousness among Iranian individuals with schizophrenia. CFA supported the two-factor structure of social effort and conscientiousness, with all items exhibiting acceptable factor loadings above 0.4. As assessed by Cronbach's alpha (α), internal consistency reliability was 0.92 for the overall scale and ranged from 0.81 to 0.89 for the subscales. These results indicate strong internal consistency reliability for the scale in measuring social effort and conscientiousness among individuals with schizophrenia.

The literature on the psychometric properties of social effort and conscientiousness measures remains limited. Among the existing research, the study by Botello et al. [16] provides some initial, albeit not fully consistent, findings. Their investigation involved 31 participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and focused on measuring changes in social functioning during a 60-day smartphone-based intervention. While their results indicated a positive association between higher social effort and improved social performance, as well as a correlation between higher social effort and reduced intensity of negative symptoms, they also found that social effort did not predict changes in social performance over the course of the intervention [16]. This latter finding, which deviates from the expected positive linear relationship between social effort and social performance, suggests a complex relationship between social effort and social outcomes. This unexpected result may indicate that other factors, such as social skills acquisition or environmental context, may mediate the impact of social effort on actual social performance. For example, individuals may exert high social effort. Still, if they lack the requisite social skills or are in an unsupportive environment, that effort may not translate into improved social performance. Alternatively, the relatively small sample size in Botello et al. [16] may have limited their power to detect a statistically significant predictive relationship. This highlights the need for further research, with larger samples and incorporating measures of potential mediating factors like social skills and environmental context, to clarify these relationships and develop more comprehensive models of social functioning in schizophrenia.

In addition to the limited research on social effort in clinical populations, Abplanalp et al. [12] conducted a study to develop and validate a self-report measure of social effort in a general population sample [12]. Their study, involving 981 master's degree students, focused on developing and validating the SEACS within this demographic. Interestingly, the results indicated that students with lower SEACS scores reported higher levels of depressive symptoms and comorbid anxiety. This finding, observed in a non-clinical sample, underscores the potential utility of the SEACS as a screening tool for identifying individuals at risk for mental health difficulties, even in seemingly high-functioning populations. It also suggests that lower social effort may be a transdiagnostic factor associated with various forms of psychological distress, further emphasizing the importance of social motivation in research and clinical practice. This study provided important preliminary evidence for the validity and reliability of the SEACS and laid the groundwork for further investigations in clinical samples, such as the current study.

This study has several limitations. The sample size, while adequate for the present analyses, could be increased in future research to strengthen further the evidence for the factor structure and reliability of the scale, particularly for exploring more nuanced relationships between social effort and other clinical variables. A larger sample size would also increase the precision of parameter estimates and reduce the potential impact of outliers. Furthermore, the use of purposive sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings, as the sample may not be fully representative of all individuals with schizophrenia in Iran. Future studies employing random sampling methods would enhance generalizability. Another limitation is the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inferences about the relationships between social effort, conscientiousness, and other variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to provide insights into the stability of social effort and conscientiousness over time among individuals with schizophrenia, as well as to examine potential changes in these constructs in response to interventions. Additionally, while this study focused on individuals with schizophrenia, future research could explore the psychometric properties of the Persian SEACS in other clinical populations (e.g., individuals with depression or social anxiety) to determine its broader applicability. Finally, the reliance on self-report measures, including the SEACS itself, introduces the possibility of response bias (e.g., social desirability bias). Future studies could consider incorporating more objective measures of social functioning to complement self-report data.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study have several practical implications. The validated Persian version of the SEACS provides clinicians and researchers in Iran with a valuable tool for assessing social effort and conscientiousness in individuals with schizophrenia. This can inform treatment planning by identifying specific areas of social motivation that may be targeted for intervention. For example, individuals with low social effort might benefit from interventions designed to enhance their motivation to engage in social interactions, such as motivational interviewing or interventions focused on increasing reward learning in social contexts. Furthermore, the SEACS can be used to track changes in social effort and conscientiousness throughout treatment, providing valuable feedback on treatment effectiveness. Researchers can also use the Persian SEACS to investigate the relationship between social effort and other important clinical variables in Iranian samples, contributing to a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to social dysfunction in schizophrenia.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the SEACS possesses satisfactory psychometric properties. These findings support its use as a valid and reliable instrument in research and clinical settings for assessing social effort and conscientiousness among individuals with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments: This article was extracted from a part of the PhD research project of Ms. Mina Mahmoudi Tabar at the Department of Clinical Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. The researchers wish to thank all the participants for contributing to this study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Review Board of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1402.574).

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interest declared.

Authors' Contribution: Sarafraz MR (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mahmoudi Tabar M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Pourshams M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: This research was conducted using the researcher's personal funds. No external funding was received for this study.

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating mental disorder [1] affecting approximately 1% of the global population across the lifespan [2]. The relatively consistent risk of developing this disorder across diverse geographical and cultural contexts suggests the influence of underlying biological factors. Characterized by a complex interplay of positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms [3], schizophrenia presents with varied manifestations. Positive symptoms involve distortions of reality, such as delusions (fixed false beliefs) and hallucinations (perceptual experiences in the absence of external stimuli). Negative symptoms reflect a diminution or absence of normal functions, including affective flattening (reduced emotional expression), alogia (poverty of speech), avolition (lack of motivation), and anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure). Cognitive symptoms encompass attention, memory, executive functions, and processing speed impairments. These symptom clusters contribute significantly to the substantial social dysfunction frequently observed in individuals with schizophrenia [4]. Diminished social functioning is a hallmark of the disorder [5], impacting various life domains, including interpersonal relationships, occupational performance, and independent living skills [6]. Consequently, impaired social functioning plays a crucial role in predicting the course of illness, risk of relapse, and overall prognosis [7], underscoring the importance of interventions targeting social skills and community integration.

Unemployment and financial hardship, frequently experienced by individuals with schizophrenia, significantly limit opportunities for social interaction and engagement [8], contributing to the erosion of social networks and the weakening of social bonds [9]. These socioeconomic challenges can create barriers to accessing social activities, maintaining stable housing, and participating in community life, further exacerbating social isolation. Social motivation, analogous to general motivation, is a multifaceted construct encompassing reward learning (the process of associating actions with positive outcomes), hedonic experience (the capacity to derive pleasure from rewarding stimuli), and effort computation (the assessment of the cost-benefit ratio of pursuing a goal) [10]. Within social interaction, social motivation specifically pertains to the drive to approach or avoid social stimuli based on their perceived desirability or aversiveness [11]. This involves evaluating the potential rewards of social engagement (e.g., companionship, support, positive feedback) against potential costs (e.g., social anxiety, fear of rejection, past negative experiences). Deficits in any of these components can significantly impair an individual's ability to initiate and maintain meaningful social relationships, further contributing to social dysfunction.

Establishing and maintaining friendships requires a fundamental desire for social connection and engagement, manifested through specific behaviors [12], such as initiating contact, expressing interest in others, and demonstrating reciprocal engagement. Social effort, a crucial component of social motivation, encompasses the behavioral tendencies to actively pursue positive social outcomes (e.g., building relationships, seeking support, engaging in enjoyable activities) or to avoid negative social consequences (e.g., social rejection, conflict, embarrassment) within social communication contexts [12]. This construct highlights the proactive role individuals play in shaping their social experiences. Contemporary psychopathology research increasingly emphasizes approach/avoidance motivation theories [13] as a framework for understanding various behavioral patterns and psychological processes. These theories posit two fundamental motivational systems: An approach system, which promotes engagement with rewarding stimuli and the pursuit of positive goals, and an avoidance system, which promotes withdrawal from threatening stimuli and the prevention of negative outcomes. Within the context of social functioning in schizophrenia, examining the interplay between these systems can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying social withdrawal and isolation.

While social skills training (SST) has demonstrated efficacy in improving interpersonal functioning, adaptive social behavior, and overall quality of life for individuals with various mental health conditions, including schizophrenia [14], the concept of social effort and its measurement have received comparatively less attention [15]. SST interventions typically teach specific social skills, such as initiating conversations, expressing emotions, and resolving conflicts. This relative lack of focus on social effort (the willingness to invest energy and resources in social interactions) represents a significant gap, as it may be a crucial factor influencing the effectiveness of SST and the overall trajectory of social recovery.

The Social Effort and Conscientiousness Scale (SEACS) has been previously validated and has demonstrated associations with depressive symptoms and comorbid anxiety [12], suggesting its relevance to affective and motivational processes. This scale is valuable for assessing individuals' willingness to invest effort in social interactions and adhere to social norms. A recent study validating the SEACS in individuals with schizophrenia [16] provided crucial insights into the role of social effort in this population, revealing a significant correlation between heightened social effort and improved social functioning, as well as an inverse relationship between social effort and the severity of negative symptoms. However, while this study [16] provided initial evidence of the SEACS's utility in schizophrenia, it did not examine the psychometric properties of the SEACS in diverse cultural contexts. Specifically, the psychometric properties of the Persian language version of the SEACS had not been established. Furthermore, the absence of a culturally adapted instrument can hinder accurate assessment and limit the applicability of research findings across different populations. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation are essential in ensuring that psychological instruments are culturally relevant and psychometrically sound when used in different linguistic and cultural groups. Given the absence of research investigating the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the SEACS in individuals with schizophrenia in Iran, this study evaluated these properties within this specific population.

This study addressed a critical gap in the literature by providing a validated Persian SEACS for use with Iranian individuals experiencing schizophrenia, enabling more culturally sensitive and accurate assessments of social effort and conscientiousness.

Instrument and Methods

Design and participants

This study employed a cross-sectional correlational design to examine 83 Iranian adults diagnosed with schizophrenia and receiving treatment at Golestan, Salamat, and Sina medical centers in Ahvaz City in 2023. The sample size was determined a priori using a power analysis conducted with G*Power software. Based on an estimated medium effect size (Cohen’s f²=0.15), a desired power of 0.80, and an alpha level of 0.05, the power analysis indicated a sample size of 83 would provide adequate statistical power to detect significant relationships among the variables of interest. Participants were selected through purposive sampling. The research team collaborated with the medical centers to identify potential participants meeting the inclusion criteria: A diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [17]; Illness duration within five years of diagnosis; Age between 18 and 65 years; And current receipt of medication and psychotherapy. Trained research assistants approached potential participants during routine medical center visits, providing detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and participant rights. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals. Exclusion criteria included: A diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or a related disorder; A diagnosis of major depressive disorder; A diagnosis of a substance use disorder; Unwillingness to participate; Or self-reported drug use within the past month. The final sample comprised 83 participants who met all inclusion and exclusion criteria and completed the study procedures.

Instrument

The Social Effort and Conscientiousness Scale (SEACS): The SEACS, developed by Abplanalp et al. in 2022 [12], employs a six-point Likert scale ranging from "very strongly disagree" to "very strongly agree". The SEACS comprises two subscales: Social effort (8 items) and social conscientiousness (4 items). The original 17-item version included filler items, and one item was subsequently removed by the developers due to insufficient item performance, resulting in the 12-item version used for analysis. Lower SEACS scores indicate greater impairment in social effort and conscientiousness. Abplanalp et al. [12] established the content validity of the SEACS, defining it as encompassing both general social effort and social effort in adherence to social norms. Their research, conducted on two college student samples, found no significant gender differences in SEACS scores but revealed differences based on race and age categories, suggesting that the SEACS is a reliable and valid measure of social effort and conscientiousness. Furthermore, lower SEACS scores were associated with increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, highlighting the scale's potential utility in clinical populations.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): The PANSS, developed in 1986, is a widely used instrument for assessing the severity of positive and negative symptoms in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia [18]. It comprises several subscales measuring distinct symptom dimensions. Two studies conducted in Iran reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.8 [19] and 0.77 [20] for the PANSS, indicating acceptable internal consistency. These values suggest that the items within the Iranian versions of the PANSS consistently measure the intended constructs of positive and negative symptoms.

The Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ): The SFQ assesses an individual's social performance over the past two weeks across several domains, including home life, work (or other productive activity), financial management, family relationships, sexual relationships, social relationships, and leisure activities [21]. The reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients for this scale are 0.77 [22]. A Cronbach's alpha of 0.77 suggests good internal consistency for the SFQ in the samples where it was measured [22]. This indicates that the items within the SFQ consistently measure the intended construct of social functioning.

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS): The CDSS is a specific instrument designed to assess depressive symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia and distinguish them from negative symptoms. Comprising nine items, the CDSS was developed by Addington et al. in 1992 [23]. Confirmatory factor analysis has demonstrated that the CDSS exhibits a unidimensional structure, measuring a single underlying construct of depressive severity consistently across both inpatient and outpatient settings. It has also been established as a reliable instrument for assessing depression in both acute and residual phases of schizophrenia. The validity and reliability of the CDSS have been investigated and confirmed in Iranian samples [24].

Procedure

The questionnaire underwent a forward-backward translation process. Initially, two independent translations from English to Persian were conducted by two English language experts, one with expertise in psychology. Discrepancies between these translations were resolved through discussion and consensus, resulting in a preliminary Persian version. Subsequently, two different English language experts back-translated this Persian version into English. A meeting was then convened by a psychiatrist, a psychologist, and the translators to compare the original English version with the back-translated version. Following this review, the final Persian version was presented to five psychiatrists and psychologists to assess the overall structure and clarity of the questions. Additionally, ten individuals with schizophrenia reviewed the questionnaire to ensure its comprehensibility. The final Persian version of the questionnaire was finalized based on the feedback received.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27 and SmartPLS version 3 software. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to assess the construct validity of the SEACS, examining the hypothesized relationships between the scale's items and its underlying factors. CFA was deemed appropriate as it allows testing a pre-defined theoretical model of the factor structure. Model fit was evaluated using several indices, including the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and the comparative fit index (CFI). Factor loadings were also examined, reflecting the strength of the relationship between each item and its respective factor. Convergent validity, the extent to which the scale correlates with other measures of the same construct, was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE). An AVE value of 0.5 or greater is generally considered acceptable, indicating that the variance explained by the latent construct is greater than the error variance. Discriminant validity, the extent to which the scale does not correlate with measures of different constructs, was examined using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) and the Fornell-Larcker criterion. HTMT is considered a more robust measure of discriminant validity than the Fornell-Larcker criterion. An HTMT value below 0.90 suggests adequate discriminant validity. These analyses, comparing the SEACS with the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), evaluated whether the SEACS measures a construct distinct from these other measures. Reliability, the consistency of the scale's measurements, was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (α) and composite reliability. Cronbach's alpha assesses the internal consistency of the items within each scale/subscale, while composite reliability is an alternative measure of internal consistency, especially relevant in structural equation modeling. Values of 0.70 or higher are generally considered acceptable for both Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, indicating good internal consistency.

Findings

Eighty-three individuals with schizophrenia (55 men and 28 women) participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 39.71±10.38 (18 to 65) years (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive findings related to queSstionnaires

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the SEACS's construct validity (Figure 1). The hypothesized model demonstrated acceptable fit, as indicated by a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of 0.067 and a comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.94.

Figure 1. The hypothesized construct validity model of the questionnaire

Of the original 17 items, the scale developers removed one due to insufficient item performance, and four were designated as filler items. Consequently, 12 items were retained for analysis. As shown in Table 2, all retained items exhibited factor loadings exceeding 0.4 (Table 2).

Table 2. Factor loadings for questionnaire items

Reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (α) and composite reliability (Table 3). The Cronbach's α values for the overall questionnaire and its subscales were satisfactory, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Furthermore, the composite reliability values for the overall questionnaire and its subscales were also satisfactory, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the 0.5 threshold. According to Fornell & Larcker [25], convergent validity is established when composite reliability (CR) exceeds AVE, AVE exceeds 0.5, and CR exceeds 0.7. As these criteria (CR>AVE, AVE>0.5, and CR>0.7) were met, convergent validity was confirmed.

Table 3. Reliability, composite reliability, and average variance extracted

Discriminant validity assesses the extent to which a construct is distinct from other conceptually unrelated constructs. This study evaluated discriminant validity using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT), a robust and widely accepted index for this purpose [26]. While the HTMT criterion has gained prominence and is considered a more reliable alternative, both the HTMT and the traditional Fornell-Larcker criterion were employed and are reported here to provide comprehensive evidence. An HTMT value below 0.9 indicates acceptable discriminant validity. The HTMT calculation, based on the Monte Carlo simulation method, is considered a reliable approach for assessing discriminant validity [26]. Specifically, discriminant validity is established if all pairwise HTMT values between reflective constructs are below 0.9. The Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) were used to assess the discriminant validity of the SEACS (Table 4).

Table 4. HTMT coefficients for the social effort and conscientiousness scale (overall score) with three other scales

Consistent with the HTMT results (where all values were below 0.9), the Fornell-Larcker criterion supports discriminant validity. The diagonal elements of the Fornell-Larcker matrix represent the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct. In contrast, the off-diagonal elements represent the correlations between constructs. Because the AVE square roots on the diagonal were greater than the inter-construct correlations in the off-diagonal elements, discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. Therefore, the discriminant validity of the SEACS (overall score) was established (Table 5).

Table 5. Fornell-Larcker criterion results for the social effort and conscientiousness scale

Discussion

This study investigated the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the SEACS among individuals with schizophrenia. Given that social functioning is often an important treatment goal and outcome for people with schizophrenia. Since people with schizophrenia often have poorer social functioning [5], also considering the potential role of social effort in creating social disorder [12], it is important and necessary to have an instrument with satisfactory psychometric properties that assess the domain of social effort. This is the first study to examine the psychometric properties of the Farsi version of the SEACS. In summary, the findings indicate that the Persian version of the SEACS demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties and is a valid instrument for assessing social effort and conscientiousness among Iranian individuals with schizophrenia. CFA supported the two-factor structure of social effort and conscientiousness, with all items exhibiting acceptable factor loadings above 0.4. As assessed by Cronbach's alpha (α), internal consistency reliability was 0.92 for the overall scale and ranged from 0.81 to 0.89 for the subscales. These results indicate strong internal consistency reliability for the scale in measuring social effort and conscientiousness among individuals with schizophrenia.

The literature on the psychometric properties of social effort and conscientiousness measures remains limited. Among the existing research, the study by Botello et al. [16] provides some initial, albeit not fully consistent, findings. Their investigation involved 31 participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and focused on measuring changes in social functioning during a 60-day smartphone-based intervention. While their results indicated a positive association between higher social effort and improved social performance, as well as a correlation between higher social effort and reduced intensity of negative symptoms, they also found that social effort did not predict changes in social performance over the course of the intervention [16]. This latter finding, which deviates from the expected positive linear relationship between social effort and social performance, suggests a complex relationship between social effort and social outcomes. This unexpected result may indicate that other factors, such as social skills acquisition or environmental context, may mediate the impact of social effort on actual social performance. For example, individuals may exert high social effort. Still, if they lack the requisite social skills or are in an unsupportive environment, that effort may not translate into improved social performance. Alternatively, the relatively small sample size in Botello et al. [16] may have limited their power to detect a statistically significant predictive relationship. This highlights the need for further research, with larger samples and incorporating measures of potential mediating factors like social skills and environmental context, to clarify these relationships and develop more comprehensive models of social functioning in schizophrenia.

In addition to the limited research on social effort in clinical populations, Abplanalp et al. [12] conducted a study to develop and validate a self-report measure of social effort in a general population sample [12]. Their study, involving 981 master's degree students, focused on developing and validating the SEACS within this demographic. Interestingly, the results indicated that students with lower SEACS scores reported higher levels of depressive symptoms and comorbid anxiety. This finding, observed in a non-clinical sample, underscores the potential utility of the SEACS as a screening tool for identifying individuals at risk for mental health difficulties, even in seemingly high-functioning populations. It also suggests that lower social effort may be a transdiagnostic factor associated with various forms of psychological distress, further emphasizing the importance of social motivation in research and clinical practice. This study provided important preliminary evidence for the validity and reliability of the SEACS and laid the groundwork for further investigations in clinical samples, such as the current study.

This study has several limitations. The sample size, while adequate for the present analyses, could be increased in future research to strengthen further the evidence for the factor structure and reliability of the scale, particularly for exploring more nuanced relationships between social effort and other clinical variables. A larger sample size would also increase the precision of parameter estimates and reduce the potential impact of outliers. Furthermore, the use of purposive sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings, as the sample may not be fully representative of all individuals with schizophrenia in Iran. Future studies employing random sampling methods would enhance generalizability. Another limitation is the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inferences about the relationships between social effort, conscientiousness, and other variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to provide insights into the stability of social effort and conscientiousness over time among individuals with schizophrenia, as well as to examine potential changes in these constructs in response to interventions. Additionally, while this study focused on individuals with schizophrenia, future research could explore the psychometric properties of the Persian SEACS in other clinical populations (e.g., individuals with depression or social anxiety) to determine its broader applicability. Finally, the reliance on self-report measures, including the SEACS itself, introduces the possibility of response bias (e.g., social desirability bias). Future studies could consider incorporating more objective measures of social functioning to complement self-report data.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study have several practical implications. The validated Persian version of the SEACS provides clinicians and researchers in Iran with a valuable tool for assessing social effort and conscientiousness in individuals with schizophrenia. This can inform treatment planning by identifying specific areas of social motivation that may be targeted for intervention. For example, individuals with low social effort might benefit from interventions designed to enhance their motivation to engage in social interactions, such as motivational interviewing or interventions focused on increasing reward learning in social contexts. Furthermore, the SEACS can be used to track changes in social effort and conscientiousness throughout treatment, providing valuable feedback on treatment effectiveness. Researchers can also use the Persian SEACS to investigate the relationship between social effort and other important clinical variables in Iranian samples, contributing to a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to social dysfunction in schizophrenia.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the SEACS possesses satisfactory psychometric properties. These findings support its use as a valid and reliable instrument in research and clinical settings for assessing social effort and conscientiousness among individuals with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments: This article was extracted from a part of the PhD research project of Ms. Mina Mahmoudi Tabar at the Department of Clinical Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. The researchers wish to thank all the participants for contributing to this study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Review Board of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1402.574).

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interest declared.

Authors' Contribution: Sarafraz MR (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mahmoudi Tabar M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Pourshams M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: This research was conducted using the researcher's personal funds. No external funding was received for this study.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Setting

Received: 2025/01/8 | Accepted: 2025/02/15 | Published: 2025/02/27

Received: 2025/01/8 | Accepted: 2025/02/15 | Published: 2025/02/27

References

1. Mohammadi J, Narimani M, Bagyan MJ, Dereke M. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Stud Med Sci. 2014;25(3):182-90. [Persian] [Link]

2. Owen M, Sawa A, Mortensen P. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):86-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6]

3. First MB. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, and clinical utility. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(9):727-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a2168a]

4. Sarkhel S. Kaplan and Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 10th edition. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(4):331. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.58308]

5. Oorschot M, Lataster T, Thewissen V, Lardinois M, Wichers M, Van Os J, et al. Emotional experience in negative symptoms of schizophrenia-no evidence for a generalized hedonic deficit. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(1):217-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbr137]

6. Hooley JM. Social factors in schizophrenia. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(4):238-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0963721410377597]

7. Robertson BR, Prestia D, Twamley EW, Patterson TL, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Social competence versus negative symptoms as predictors of real world social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;160(1-3):136-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.037]

8. Fulford D, Mote J, Gonzalez R, Abplanalp S, Zhang Y, Luckenbaugh J, et al. Smartphone sensing of social interactions in people with and without schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;137:613-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.11.002]

9. Fulford D, Treadway M, Woolley J. Social motivation in schizophrenia: The impact of oxytocin on vigor in the context of social and nonsocial reinforcement. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(1):116-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/abn0000320]

10. Salamone JD, Correa M. The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. 2012;76(3):470-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.021]

11. Green R. Social motivation. Annu Rev Psychol. 1991;42:377-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.002113]

12. Abplanalp SJ, Mote J, Uhlman AC, Weizenbaum E, Alvi T, Tabak BA, et al. Parsing social motivation: Development and validation of a self-report measure of social effort. J Ment Health. 2022;31(3):366-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09638237.2021.1952948]

13. Carver CS, Johnson SL, Joormann J. Serotonergic function, two-mode models of self-regulation, and vulnerability to depression: What depression has in common with impulsive aggression. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(6):912-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0013740]

14. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa051688]

15. Fulford D, Campellone T, Gard DE. Social motivation in schizophrenia: How research on basic reward processes informs and limits our understanding. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:12-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.007]

16. Botello R, Gill K, Mow JL, Leung L, Mote J, Mueser KT, et al. Validation of the social effort and conscientious scale (SEACS) in schizophrenia. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2023;45(3):844-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10862-023-10031-1]

17. Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):92-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/wps.20050]

18. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/schbul/13.2.261]

19. Ghamari Givi H, Moulavi P, Heshmati R. Exploration of the factor structure of positive and negative syndrome scale in schizophernia spectrum disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2010;2(2):1-10. [Persian] [Link]

20. Abolghasemi A. The relationship between metacognitive beliefs and positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients. Clin Psychol Personal. 2017;5(2):1-10. [Persian] [Link]

21. Tyrer PE, Casey PE. Social function in psychiatry: The hidden axis of classification exposed. Petersfield: Wrightson Biomedical Publishing; 1993. [Link]

22. Tyrer P, Nur U, Crawford M, Karlsen S, MacLean C, Rao B, et al. The social functioning questionnaire: A rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2005;51(3):265-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0020764005057391]

23. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E, Joyce J. Reliability and validity of a depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1992;6(3):201-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0920-9964(92)90003-N]

24. Rostami R, Kazemi R, Khodaie-Ardakani MR, Sohrabi L, Ghiasi S, Kamali ZS, et al. The Persian version of the Calgary depression scale for schizophrenia (CDSS-P). Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;45:44-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.08.017]

25. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/002224378101800104]

26. Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015;43(1):115-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |