Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 561-569 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Qorib F, Nurdiarti R, Septiani F, Setiawan R. Teacher-Parent Collaboration; Enhancing Education for Children with Intellectual Disabilities. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :561-569

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76870-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76870-en.html

1- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Tribhuwana Tunggadewi, Malang, Indonesia

2- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Communication and Multimedia, University of Mercubuana Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

3- Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Bandar Lampung, Bandar Lampung, Indonesia

2- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Communication and Multimedia, University of Mercubuana Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

3- Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Bandar Lampung, Bandar Lampung, Indonesia

Keywords: Intellectual Disabilities [MeSH], Education of Intellectually Disabled [MeSH], Persuasive Communication [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 609 kb]

(2838 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1204 Views)

Full-Text: (286 Views)

Introduction

Children with intellectual disabilities (ID) face profound challenges, significantly affecting their cognitive, emotional, and social development. These challenges not only stem from the inherent limitations of the disability itself but are also compounded by societal perceptions, limited access to healthcare, and inclusive educational opportunities. According to Glasson et al. [1], the prevalence of intellectual disabilities is estimated at 1% to 2% of the child population, indicating an urgent need for specialized support and interventions that can address these challenges.

Cognitive challenges are one of the most prominent aspects among children with ID. These children often show deficits in various cognitive domains, including learning, memory, and problem-solving abilities. For example, limitations in cognitive processing make it difficult for these children to assimilate new educational material, ultimately impacting their academic performance [2]. In addition, research shows that children with ID often experience significant delays in developing adaptive behaviors, which are critical for daily functioning and independence. These cognitive delays are a major obstacle in academic settings, where children with ID require customized educational strategies to facilitate their learning [3].

Furthermore, children with intellectual disabilities often encounter significant challenges in developing a sense of independence. This independence is typically linked to the ability to carry out daily tasks on their own, such as dressing, bathing, and eating. However, children with intellectual disabilities often experience delays in acquiring essential self-care skills, which can hinder their development and self-esteem [4, 5]. Research suggests that efforts to foster independence should begin early in a child's life; If independence is not nurtured from a young age, the likelihood of achieving full independence later in life is significantly reduced [6]. This confirms the importance of targeted interventions to promote independence and adaptive skills in children with special needs.

Communication is a vital element in the education of students with cognitive impairments, particularly when it comes to teaching the skills necessary for achieving independence. Effective communication strategies can enhance learning, allowing children to understand better and practice self-care tasks [7]. For example, video modeling is an effective method for teaching dressing skills to children with intellectual disabilities, as it provides visual cues that facilitate learning [8]. In addition, parents and caregivers should be equipped with the necessary skills to support their children in developing independence. Training programs that educate parents on how to teach self-care skills at home can significantly improve children's ability to perform daily tasks independently [9].

Motor skills are also integral to fostering independence in children with intellectual disabilities. Research shows that children with these disabilities often experience gross and fine motor development delays, which can hinder their ability to engage in self-care activities [4, 10]. For example, children may have difficulty in tasks such as tying shoelaces or using cutlery, which are essential for daily life [5]. Interventions focusing on improving motor skills can improve children's abilities and promote greater independence [11]. In addition, research shows a correlation between motor skills and self-concept, suggesting that as children's motor skills improve, their self-esteem and confidence in performing tasks independently may also increase [12].

Educational institutions are very important in promoting independence among children with special needs. Schools that implement individualized education programs (IEPs) tailored to the specific needs of children with intellectual disabilities can significantly impact their ability to develop independence [13]. These programs should include objectives related to self-care, social skills, and communication so that children receive comprehensive support in all aspects of development. In addition, inclusive education practices that encourage peer interaction can foster social skills and self-confidence, further contributing to a child's sense of independence [14].

Schools that serve children with special needs in Indonesia are known as Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB) or extraordinary schools. One example is SLB Bina Siwi, located in Manukan, Bantul Regency, Indonesia. This school focuses on teaching skills to students with mental and physical disabilities, with the aim that they can survive despite their imperfections [15, 16]. In addition, the learning materials and methods delivered at this school are designed to be interesting and appropriate to the needs of the students. Bina Siwi SLB also pays special attention to teaching how to communicate with children with disabilities. Children with disabilities have diverse abilities that need to be honed. However, they often need help channeling and utilizing these abilities and skills because their intelligence is below the average child in general. Therefore, therapeutic communication is indispensable to help children with disabilities express their talents and skills, even if they are not as optimal as their non-disabled peers [17, 18].

Although many studies have explored the importance of therapeutic communication and inclusive education strategies for children with intellectual disabilities, there is still a significant gap regarding how collaboration between teachers and parents can play a crucial role in implementing therapeutic communication in special schools. While previous research [19, 20] emphasizes the importance of parental involvement in the education of children with special needs, very few studies have specifically explored the interaction and synergy between teachers and parents in therapeutic communication. This area of research still needs to be touched upon, especially in the Indonesian context, which has different educational and cultural dynamics.

Research on therapeutic communication in education, particularly in Indonesia, remains limited. Most existing studies focus on its role in healthcare settings, neglecting its crucial application in the education of children with intellectual disabilities. Teachers in schools like Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB) face unique challenges that require not only pedagogical skills but also emotional support to address each child's individual needs. Despite its significance, the use of therapeutic communication in these educational environments is under-researched, creating a gap in understanding how teachers can effectively nurture emotional, cognitive, and social development in special education students. Additionally, in many cases, teachers in special schools do not initially aim to work in this field. However, they must adapt to its demands, further complicating the integration of therapeutic communication into their teaching strategies.

To tackle these challenges, collaboration between teachers and parents is essential in implementing therapeutic communication. This partnership ensures that consistent educational strategies are employed both at home and in school, allowing both parties to share methods that improve educational outcomes for children. For instance, research has shown that parental involvement reinforces school-based interventions and provides emotional support for children with special needs [21]. Moreover, observations from SLB Bina Siwi reveal that teachers often face the additional obstacle of limited training in therapeutic communication, making the collaboration with parents even more critical. By focusing on how teachers and parents interact and use therapeutic communication strategies together, this research aims to explore its impact on the overall development of children with intellectual disabilities in the Indonesian context, where educational and cultural dynamics present unique challenges. Understanding these dynamics is essential for improving both teacher training and educational practices, ensuring better outcomes for students in special education settings.

This study aims to investigate how collaboration between teachers and parents is specifically utilized to implement therapeutic communication tailored to each child's unique needs. It explores the challenges of maintaining this collaborative approach and its impact on the cognitive, emotional, and social development of children with intellectual disabilities. By examining the strategies employed to overcome these challenges, the research also seeks to highlight the critical role of emotional support in enhancing the overall effectiveness of therapeutic communication. Through this, the study hopes to shed light on how collaborative efforts can address the diverse needs of children and create a more supportive learning environment in special schools.

Furthermore, this research seeks to provide valuable insights into the forms of collaboration between teachers and parents and their influence on educational outcomes for children with disabilities. It aims to show how synergies between home and school environments offer a more holistic support system for these children. Given that children with intellectual disabilities require consistent, integrated approaches, the research's findings could inform more inclusive and adaptive education policies in Indonesia. Although focused on one particular school, the results are expected to provide a model for similar schools, contributing practical and theoretical insights that could improve the quality of education for children with disabilities across the country.

Participants and Methods

This research used a qualitative case study approach to explore the collaboration between teachers and parents in implementing therapeutic communication at Sekolah Luar Biasa Bina Siwi, Bantul, Indonesia. This approach allows for a more in-depth understanding of the complex dynamics of educating children with intellectual disabilities [22, 23]. Data were collected through in-depth interviews which were semi-structured and conducted over 3 to 6 sessions, depending on data saturation and the need for additional data verification, with each session lasting approximately 45-60 minutes.Ddirect observation and document analysis were also employed involving five teachers and three parents in the educational and therapeutic communication process.

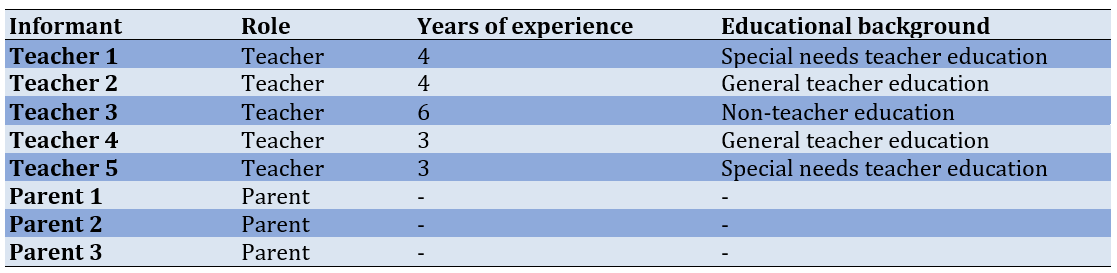

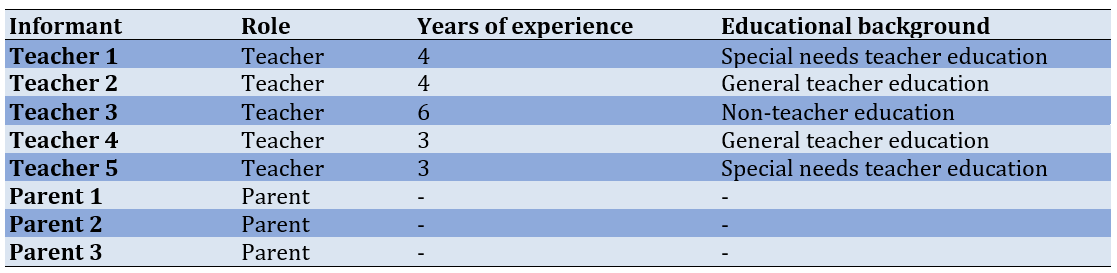

The participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure experiences and insights that fit the needs of this study [24]. Although the original plan involved 11 teachers and 5 parents, only 5 teachers met the criteria of having at least three years of experience, being willing to be interviewed, and having diverse educational backgrounds. Similarly, only 3 parents were willing to be interviewed for 3 months (Table 1). Extended observation and snowball sampling ensured data saturation, providing a comprehensive view of how therapeutic communication was implemented. To ensure data reliability and validity, the researchers cross-checked the findings, and data saturation was confirmed when no new information emerged, indicating that the data collected was sufficient to support the research analysis and conclusions.

Table 1. Research informant data determined based on purposive sampling

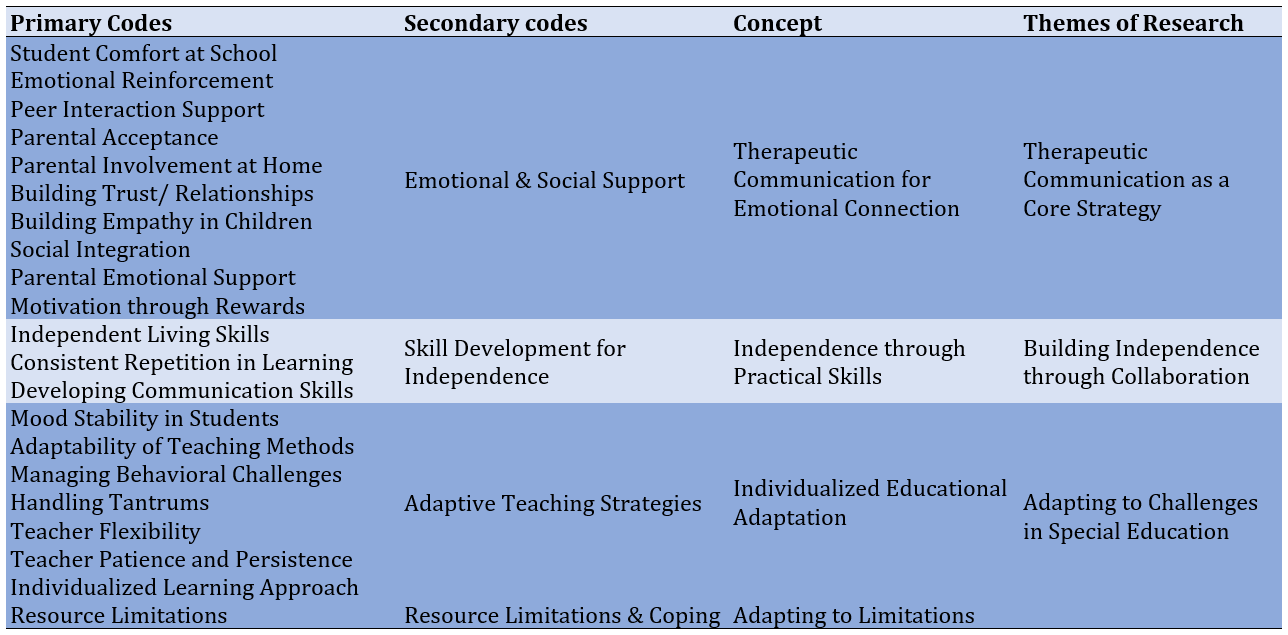

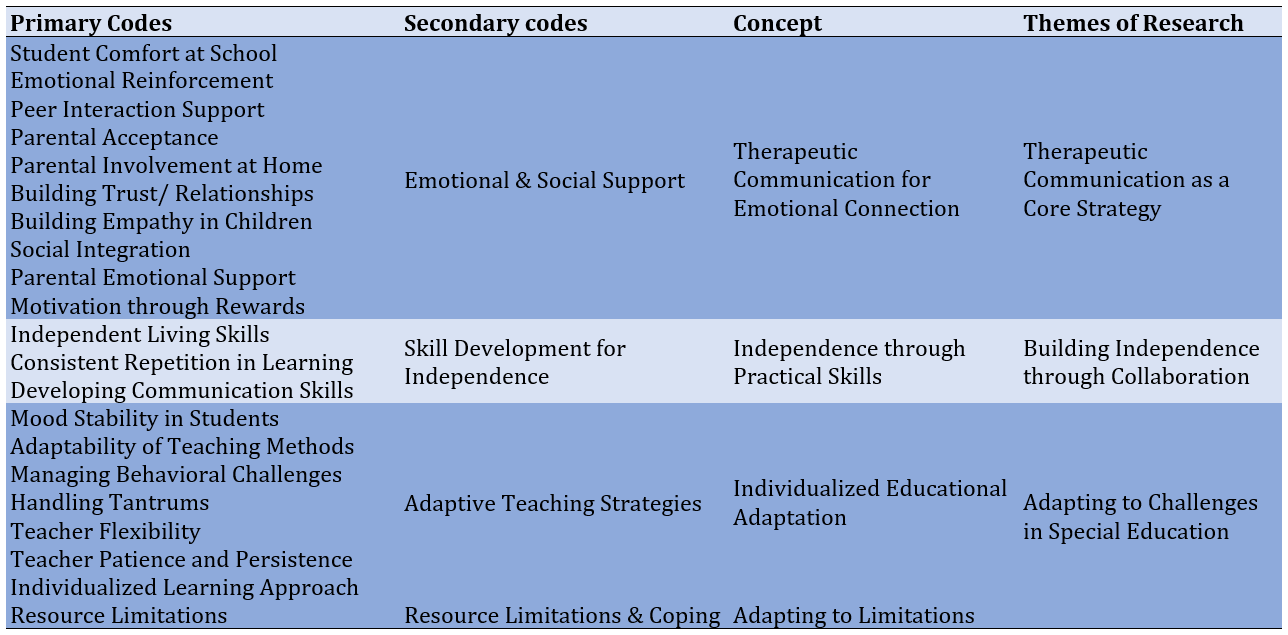

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. This method is widely used in qualitative research to identify, analyze and report patterns [25]. The first stage of analysis was familiarization, where the research team reread the interview transcripts and observation notes to identify potential codes. In the next step, we created 21 primary codes from the data extracted from recurring statements and themes in the interviews. These primary codes captured various aspects such as student comfort, emotional reinforcement, parental acceptance, independent living skills, and tantrum handling (Table 2).

Table 2. Thematic Coding Framework for Therapeutic Communication and Adaptive Strategies

These primary codes were then grouped into four secondary codes for better categorization and organization. For example, primary codes related to student comfort, emotional reinforcement, and parental acceptance were combined into the secondary code “emotional and social support”. From these secondary codes, three concepts were formed; Therapeutic communication for emotional connection, individualized educational adaptations, and fostering independence through practical skills. The final stage of analysis was to make sense of all these concepts and turn them into three themes related to therapeutic communication; Therapeutic communication as a core strategy, building independence through collaboration, and adapting to challenges in special education.

Data triangulation was employed to ensure the credibility and consistency of the findings. This was achieved by cross-verifying data from interviews, observations, and documents, which helped maintain the robustness of the analysis. To enhance validity, member checks were conducted, where researchers reviewed the identified codes and themes to confirm their accuracy and representation of participants’ perspectives. Additionally, peer debriefing sessions were held regularly, allowing colleagues to review and refine interpretations, thus minimizing potential bias and improving analytical rigor [26]. Furthermore, prolonged engagement, through three months of direct observation, contributed to a deeper understanding of the context, increasing the overall reliability of the results [27].

Findings

Children with mental disabilities in the view of teachers and parents

Teachers at SLB Bina Siwi face challenges teaching children with mental disabilities, but they remain determined and patient. These children need more than academic instruction; They require emotional support and an individualized approach. Teachers focus on making children feel comfortable and accepted, using therapeutic communication to create a safe environment. This method builds trust, fosters positive relationships, and reduces stress and anxiety, helping children learn at their own pace.

“Teachers in special schools cannot apply the same learning process as in regular schools ... The first thing teachers do at school is to make children feel comfortable by meeting new people, as these children find it difficult to accept new people, especially in large numbers” (Interview with SLB teacher).

Parents also play a key role, supporting education at home and embracing their child's condition as a gift. One parent shared, “At first, I felt sad ... I must accept my child's condition because this is a gift from God, so no matter what, I must sincerely care for and raise him”. Collaboration between teachers and parents creates a consistent, supportive environment. A parent explained, “At home, we also teach independent behavior. My child now showers by himself, wears his own uniform, and buttons his clothes”.

With this collaborative and supportive approach, children at SLB Bina Siwi benefit from therapeutic communication that promotes their social, emotional, and cognitive development, fostering independence and self-confidence.

Teacher and parent cooperation in educating children with special needs

At SLB Bina Siwi, teachers play a crucial role in using therapeutic communication to promote the independence of children with disabilities. This approach combines empathy with effective communication techniques, creating a supportive learning environment. Teachers encourage independence in daily activities like eating, bathing, and dressing, ensuring each child feels valued and supported.

“We always try to communicate with parents about what we teach at school, so they can continue it at home” (Interview with SLB teacher).

This highlights the importance of therapeutic communication that involves not only teachers and students but also parents, ensuring consistent learning both at school and home. Teachers serve as consultants, offering parents strategies to foster independence.

“At first, I didn’t know how to teach independence to my child. After communicating with the teachers and following their advice, I saw many positive changes” (Interview with SLB parent).

This quote reflects the significance of teacher support in guiding parents. Teachers also use praise to motivate children, fostering emotional connections that enhance learning.

“They like to be praised, like ‘come on to school to get smarter,’ ... we have to be smart to make them happy and motivated to attend school” (Interview with SLB teacher).

Verbal praise and emotional support are central to building confidence and independence in children. Teachers adapt their communication style to meet each child’s needs, demonstrating flexibility.

“Children with intellectual disabilities cannot be taught only once; It must be repeated continuously” (Interview with SLB teacher).

This patient and personalized approach ensures that children can master skills at their own pace. Collaboration between teachers and parents is essential for tracking progress and adjusting teaching methods.

“Teachers in SLB cannot apply the learning process like in schools in general ... The first thing teachers apply at school is to make children feel comfortable” (Interview with SLB teacher).

Regular meetings between teachers and parents foster open communication, helping children thrive both emotionally and academically. This partnership between home and school is key to the holistic development of children with intellectual disabilities at SLB Bina Siwi.

Obstacles in the learning process in special schools

The learning process at Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB) Bina Siwi faces unique challenges, especially when teaching children with intellectual disabilities. One major obstacle is managing the children's mood during the learning process. Since these children often arrive at school in a bad mood, teachers must make extra efforts to stabilize their emotions for effective learning.

"If we keep them in a good mood all the time, it's impossible because sometimes even at home they are not in the mood to go to school, so at school, it is quite difficult to restore or change their mood" (Interview with SLB teacher).

This statement highlights the need for therapeutic communication, where teachers use empathy and understanding to respond to the children's mood changes. Techniques like active listening and emotional support are crucial in overcoming these challenges. Another challenge is the need for repetition in teaching. Children with intellectual disabilities require repeated lessons to fully grasp new concepts, which demands patience and persistence from teachers.

"Children with intellectual disabilities cannot be taught just once ... So, the repetition of each lesson or skill must always be repeated so that they can apply it" (Interview with SLB teacher).

Repetition aligns with therapeutic communication principles, helping children internalize information at their own pace. Teachers also face tantrums, which can disrupt the learning process. Recognizing when to pause and give children time to calm down is essential.

"There is no learning process for children who are having tantrums, because they cannot communicate and certainly cannot accept what the teacher teaches" (Interview with SLB teacher).

Therapeutic communication helps create a calm and supportive environment for children to refocus on learning after such episodes. Making children feel safe and comfortable at school is another obstacle, as fear of a new environment can hinder their adaptation and learning.

"The first obstacle when doing the teaching and learning process is how to make children feel at home at school and without being waited on by their parents" (Interview with SLB teacher).

Using affectionate interactions and consistent routines, teachers build trust, helping children feel secure and ready to learn. Teachers must also navigate challenges related to assertiveness, as children with intellectual disabilities require a more flexible and understanding approach compared to regular schools.

"Assertiveness cannot be used to train or teach children with intellectual disabilities because their IQ is different from other normal people" (Interview with SLB teacher).

This underscores the importance of adapting teaching methods to each child's individual needs. Despite resource and time limitations, teachers at SLB Bina Siwi apply therapeutic communication to overcome these challenges. Collaboration with parents and the school community is essential to support the optimal development of these children, ensuring they learn and grow in a nurturing and understanding environment.

Discussion

This study found that the high level of acceptance and understanding demonstrated by teachers and parents towards children with intellectual disabilities at SLB Bina Siwi is pivotal to their educational success. Such acceptance forms a fundamental component of the educational process for these children, as the positive attitudes of teachers and parents can significantly enhance the overall learning experience and academic outcomes for the students [28]. When children feel accepted and supported by their environment, they tend to be more open to learning and more motivated to participate in school activities. The consistent use of therapeutic communication enhances this positive atmosphere, creating a foundation of trust that promotes both engagement and emotional growth.

The individualized and customized approach to teaching at SLB Bina Siwi demonstrates the importance of flexibility and adaptation in educating children with intellectual disabilities. Teachers at this school use a highly personalized approach tailored to each child’s needs. No one method is applied uniformly; Teachers must adapt to the uniqueness of each child. For example, some children respond positively to praise, while others require a different approach, such as unique timing or individualized treatment. By implementing adaptive communication techniques, teachers not only address cognitive development but also encourage children’s independence, helping them become more confident in navigating their learning journey. The findings underscore that education in SLB is not just about cognitive skills but also adaptive and emotional skills, which are crucial for long-term success.

Another unique approach found at Bina Siwi SLB is the integration of independence and emotional warmth. Teachers at this school not only teach practical skills but also create an environment of compassion and emotional support. They combine teaching independence with providing emotional warmth, such as giving praise or extra attention. Such a combination not only aids skill development but also aligns with therapeutic communication principles, where emotional nurturing supports the learning process, fostering resilience among children. This suggests that a balance between fostering autonomy and emotional support is key to achieving success in special education.

Collaboration between teachers and parents at SLB Bina Siwi exemplifies a cooperative and supportive approach to educating children with special needs. Through this collaboration, teachers and parents can create an environment where children feel understood and supported, which is crucial for their growth and learning [29]. Despite limitations in resources, Bina Siwi SLB can maintain an effective learning environment through close coordination between teachers and parents. Such coordination not only reinforces learning outcomes but also helps children adapt more effectively across different settings, emphasizing that consistent communication often outweighs material resources in achieving educational success.

Specific challenges and solutions in the education of children with disabilities were also identified in this study. One of the biggest challenges is maintaining children’s motivation and interest in learning, which often fluctuates. SLB Bina Siwi teachers apply various creative strategies, such as providing small challenges with simple rewards, to keep children’s interests high. These strategies are not only motivational but also reflect therapeutic communication’s core focus on addressing both emotional and cognitive needs, allowing for sustained engagement. This highlights the need for a more dynamic and responsive approach to students’ emotional and motivational needs, which differs from the more rigid approach in many other education systems.

Therapeutic communication plays a central role in overcoming these challenges. By using therapeutic communication techniques, teachers can connect with students on a deeper level, building trust and better understanding. This approach allows teachers to respond more appropriately to students’ emotional needs, creating a more conducive learning environment [30]. Parental involvement is also crucial in the education of children with intellectual disabilities. When parents actively participate and understand their children’s unique needs, they are more likely to collaborate effectively with teachers in implementing educational strategies [28, 29]. Active involvement not only supports academic outcomes but also reinforces therapeutic communication methods, providing consistent emotional and educational support across home and school settings. This parental involvement reduces the stress and anxiety that parents often feel in parenting children with intellectual disabilities [31].

Parental involvement also contributes to children’s increased independence at home, which is important to support the learning process at school. When parents can continue the therapeutic communication practices initiated at school, children receive more consistent and comprehensive support, which is crucial for their emotional and social development [32, 33]. However, this study also found some obstacles in the learning process at SLB Bina Siwi. The main challenge is stabilizing children’s moods during lessons, as they often arrive at school already in a negative emotional state. Teachers must work diligently to restore their mood to create an effective learning environment. Adjusting communication strategies in real-time, such as using calming tones or gentle prompts, helps manage these emotional shifts and maintains a supportive atmosphere. This requires great flexibility and adaptability from teachers, who must constantly modify their teaching methods to align with the student’s emotional and cognitive states [34].

Another obstacle faced by teachers is the need for repetitive instruction, which is essential for solidifying children’s understanding and retention of information [35]. While repetition may be challenging, it also serves as a tool for reinforcing both knowledge and confidence as children become more familiar with the material and feel a sense of mastery. This process, although demanding, aligns well with therapeutic communication’s emphasis on consistency and patience.

Managing tantrum behavior among children with intellectual disabilities presents an additional challenge. Teachers must be sensitive to each child’s emotional state, pausing when necessary to allow for calming before resuming lessons. Limited resources at SLB Bina Siwi also pose significant challenges. Teachers often need to innovate and adjust their methods to accommodate the available resources while still providing effective learning experiences. Therapeutic communication becomes even more essential here, helping teachers maximize the impact of their interactions despite resource constraints [36].

In addition to resource limitations, teachers at SLB Bina Siwi also face challenges in adapting their teaching methods to each child’s individual needs. This requires great flexibility and the ability to adapt teaching strategies quickly based on children’s responses and progress. Therapeutic communication assists teachers in navigating these challenges by providing a framework to listen better and respond to children’s emotional and cognitive needs.

This research shows that the successful education of children with intellectual disabilities relies heavily on a close partnership between teachers and parents. A positive and collaborative relationship between the two parties allows for the continuous exchange of information and the development of more effective educational strategies. This helps children thrive academically and improves their emotional well-being by creating a safe and supportive environment. Although this study was limited to one school, the findings provide important insights into the importance of therapeutic communication and collaboration between teachers and parents in educating children with intellectual disabilities. Further research is needed to understand how these practices can be applied across different educational contexts. This includes further exploration of how differences in culture, school resources, and individual backgrounds affect the effectiveness of therapeutic communication and collaboration in special education.

It is recommended that further research be conducted across different school contexts and environments to gain deeper insights into the differences in educational practices and collaboration in educating children with intellectual disabilities. In addition, the government and educational institutions should develop more inclusive and supportive policies for children with special needs by ensuring adequate resource allocation and providing ongoing training for educators. The limitations of this study, including its focus on one institution, suggest that a broader policy framework is needed to ensure the sustainability and scalability of adaptive teaching methods and therapeutic communication strategies. Future research should also examine the long-term impact of these strategies on children's academic achievement, emotional development and social integration, to ensure that adaptive education truly meets the needs of the whole student. This will help ensure that every child has an equal opportunity to learn and thrive in a nurturing and inclusive environment, regardless of their limitations.

Conclusion

The research findings show that flexible and individualized approaches to teaching and therapeutic communication play an important role in supporting the academic and emotional development of children with intellectual disabilities.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Tribhuwana Tunggadewi University, Universitas Mercubuana Yogyakarta, and Bandar Lampung University for their support during this research. We also gratefully acknowledge the teachers and parents of Bina Siwi SLB students for their cooperation and valuable input in making this research a success.

Ethical Permissions: This research adhered to all ethical guidelines and standards. Since the study focused on gathering opinions from informants through interviews and observations without conducting any experiments or interventions. Additionally, full informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their confidentiality was strictly maintained throughout the study. Therefore, no ethical issues arose during the research process.

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing is declared by the authors.

Authors' Contribution: Qorib F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Original Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Nurdiarti RP (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Septiani F (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Setiawan R (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit agencies.

Children with intellectual disabilities (ID) face profound challenges, significantly affecting their cognitive, emotional, and social development. These challenges not only stem from the inherent limitations of the disability itself but are also compounded by societal perceptions, limited access to healthcare, and inclusive educational opportunities. According to Glasson et al. [1], the prevalence of intellectual disabilities is estimated at 1% to 2% of the child population, indicating an urgent need for specialized support and interventions that can address these challenges.

Cognitive challenges are one of the most prominent aspects among children with ID. These children often show deficits in various cognitive domains, including learning, memory, and problem-solving abilities. For example, limitations in cognitive processing make it difficult for these children to assimilate new educational material, ultimately impacting their academic performance [2]. In addition, research shows that children with ID often experience significant delays in developing adaptive behaviors, which are critical for daily functioning and independence. These cognitive delays are a major obstacle in academic settings, where children with ID require customized educational strategies to facilitate their learning [3].

Furthermore, children with intellectual disabilities often encounter significant challenges in developing a sense of independence. This independence is typically linked to the ability to carry out daily tasks on their own, such as dressing, bathing, and eating. However, children with intellectual disabilities often experience delays in acquiring essential self-care skills, which can hinder their development and self-esteem [4, 5]. Research suggests that efforts to foster independence should begin early in a child's life; If independence is not nurtured from a young age, the likelihood of achieving full independence later in life is significantly reduced [6]. This confirms the importance of targeted interventions to promote independence and adaptive skills in children with special needs.

Communication is a vital element in the education of students with cognitive impairments, particularly when it comes to teaching the skills necessary for achieving independence. Effective communication strategies can enhance learning, allowing children to understand better and practice self-care tasks [7]. For example, video modeling is an effective method for teaching dressing skills to children with intellectual disabilities, as it provides visual cues that facilitate learning [8]. In addition, parents and caregivers should be equipped with the necessary skills to support their children in developing independence. Training programs that educate parents on how to teach self-care skills at home can significantly improve children's ability to perform daily tasks independently [9].

Motor skills are also integral to fostering independence in children with intellectual disabilities. Research shows that children with these disabilities often experience gross and fine motor development delays, which can hinder their ability to engage in self-care activities [4, 10]. For example, children may have difficulty in tasks such as tying shoelaces or using cutlery, which are essential for daily life [5]. Interventions focusing on improving motor skills can improve children's abilities and promote greater independence [11]. In addition, research shows a correlation between motor skills and self-concept, suggesting that as children's motor skills improve, their self-esteem and confidence in performing tasks independently may also increase [12].

Educational institutions are very important in promoting independence among children with special needs. Schools that implement individualized education programs (IEPs) tailored to the specific needs of children with intellectual disabilities can significantly impact their ability to develop independence [13]. These programs should include objectives related to self-care, social skills, and communication so that children receive comprehensive support in all aspects of development. In addition, inclusive education practices that encourage peer interaction can foster social skills and self-confidence, further contributing to a child's sense of independence [14].

Schools that serve children with special needs in Indonesia are known as Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB) or extraordinary schools. One example is SLB Bina Siwi, located in Manukan, Bantul Regency, Indonesia. This school focuses on teaching skills to students with mental and physical disabilities, with the aim that they can survive despite their imperfections [15, 16]. In addition, the learning materials and methods delivered at this school are designed to be interesting and appropriate to the needs of the students. Bina Siwi SLB also pays special attention to teaching how to communicate with children with disabilities. Children with disabilities have diverse abilities that need to be honed. However, they often need help channeling and utilizing these abilities and skills because their intelligence is below the average child in general. Therefore, therapeutic communication is indispensable to help children with disabilities express their talents and skills, even if they are not as optimal as their non-disabled peers [17, 18].

Although many studies have explored the importance of therapeutic communication and inclusive education strategies for children with intellectual disabilities, there is still a significant gap regarding how collaboration between teachers and parents can play a crucial role in implementing therapeutic communication in special schools. While previous research [19, 20] emphasizes the importance of parental involvement in the education of children with special needs, very few studies have specifically explored the interaction and synergy between teachers and parents in therapeutic communication. This area of research still needs to be touched upon, especially in the Indonesian context, which has different educational and cultural dynamics.

Research on therapeutic communication in education, particularly in Indonesia, remains limited. Most existing studies focus on its role in healthcare settings, neglecting its crucial application in the education of children with intellectual disabilities. Teachers in schools like Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB) face unique challenges that require not only pedagogical skills but also emotional support to address each child's individual needs. Despite its significance, the use of therapeutic communication in these educational environments is under-researched, creating a gap in understanding how teachers can effectively nurture emotional, cognitive, and social development in special education students. Additionally, in many cases, teachers in special schools do not initially aim to work in this field. However, they must adapt to its demands, further complicating the integration of therapeutic communication into their teaching strategies.

To tackle these challenges, collaboration between teachers and parents is essential in implementing therapeutic communication. This partnership ensures that consistent educational strategies are employed both at home and in school, allowing both parties to share methods that improve educational outcomes for children. For instance, research has shown that parental involvement reinforces school-based interventions and provides emotional support for children with special needs [21]. Moreover, observations from SLB Bina Siwi reveal that teachers often face the additional obstacle of limited training in therapeutic communication, making the collaboration with parents even more critical. By focusing on how teachers and parents interact and use therapeutic communication strategies together, this research aims to explore its impact on the overall development of children with intellectual disabilities in the Indonesian context, where educational and cultural dynamics present unique challenges. Understanding these dynamics is essential for improving both teacher training and educational practices, ensuring better outcomes for students in special education settings.

This study aims to investigate how collaboration between teachers and parents is specifically utilized to implement therapeutic communication tailored to each child's unique needs. It explores the challenges of maintaining this collaborative approach and its impact on the cognitive, emotional, and social development of children with intellectual disabilities. By examining the strategies employed to overcome these challenges, the research also seeks to highlight the critical role of emotional support in enhancing the overall effectiveness of therapeutic communication. Through this, the study hopes to shed light on how collaborative efforts can address the diverse needs of children and create a more supportive learning environment in special schools.

Furthermore, this research seeks to provide valuable insights into the forms of collaboration between teachers and parents and their influence on educational outcomes for children with disabilities. It aims to show how synergies between home and school environments offer a more holistic support system for these children. Given that children with intellectual disabilities require consistent, integrated approaches, the research's findings could inform more inclusive and adaptive education policies in Indonesia. Although focused on one particular school, the results are expected to provide a model for similar schools, contributing practical and theoretical insights that could improve the quality of education for children with disabilities across the country.

Participants and Methods

This research used a qualitative case study approach to explore the collaboration between teachers and parents in implementing therapeutic communication at Sekolah Luar Biasa Bina Siwi, Bantul, Indonesia. This approach allows for a more in-depth understanding of the complex dynamics of educating children with intellectual disabilities [22, 23]. Data were collected through in-depth interviews which were semi-structured and conducted over 3 to 6 sessions, depending on data saturation and the need for additional data verification, with each session lasting approximately 45-60 minutes.Ddirect observation and document analysis were also employed involving five teachers and three parents in the educational and therapeutic communication process.

The participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure experiences and insights that fit the needs of this study [24]. Although the original plan involved 11 teachers and 5 parents, only 5 teachers met the criteria of having at least three years of experience, being willing to be interviewed, and having diverse educational backgrounds. Similarly, only 3 parents were willing to be interviewed for 3 months (Table 1). Extended observation and snowball sampling ensured data saturation, providing a comprehensive view of how therapeutic communication was implemented. To ensure data reliability and validity, the researchers cross-checked the findings, and data saturation was confirmed when no new information emerged, indicating that the data collected was sufficient to support the research analysis and conclusions.

Table 1. Research informant data determined based on purposive sampling

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. This method is widely used in qualitative research to identify, analyze and report patterns [25]. The first stage of analysis was familiarization, where the research team reread the interview transcripts and observation notes to identify potential codes. In the next step, we created 21 primary codes from the data extracted from recurring statements and themes in the interviews. These primary codes captured various aspects such as student comfort, emotional reinforcement, parental acceptance, independent living skills, and tantrum handling (Table 2).

Table 2. Thematic Coding Framework for Therapeutic Communication and Adaptive Strategies

These primary codes were then grouped into four secondary codes for better categorization and organization. For example, primary codes related to student comfort, emotional reinforcement, and parental acceptance were combined into the secondary code “emotional and social support”. From these secondary codes, three concepts were formed; Therapeutic communication for emotional connection, individualized educational adaptations, and fostering independence through practical skills. The final stage of analysis was to make sense of all these concepts and turn them into three themes related to therapeutic communication; Therapeutic communication as a core strategy, building independence through collaboration, and adapting to challenges in special education.

Data triangulation was employed to ensure the credibility and consistency of the findings. This was achieved by cross-verifying data from interviews, observations, and documents, which helped maintain the robustness of the analysis. To enhance validity, member checks were conducted, where researchers reviewed the identified codes and themes to confirm their accuracy and representation of participants’ perspectives. Additionally, peer debriefing sessions were held regularly, allowing colleagues to review and refine interpretations, thus minimizing potential bias and improving analytical rigor [26]. Furthermore, prolonged engagement, through three months of direct observation, contributed to a deeper understanding of the context, increasing the overall reliability of the results [27].

Findings

Children with mental disabilities in the view of teachers and parents

Teachers at SLB Bina Siwi face challenges teaching children with mental disabilities, but they remain determined and patient. These children need more than academic instruction; They require emotional support and an individualized approach. Teachers focus on making children feel comfortable and accepted, using therapeutic communication to create a safe environment. This method builds trust, fosters positive relationships, and reduces stress and anxiety, helping children learn at their own pace.

“Teachers in special schools cannot apply the same learning process as in regular schools ... The first thing teachers do at school is to make children feel comfortable by meeting new people, as these children find it difficult to accept new people, especially in large numbers” (Interview with SLB teacher).

Parents also play a key role, supporting education at home and embracing their child's condition as a gift. One parent shared, “At first, I felt sad ... I must accept my child's condition because this is a gift from God, so no matter what, I must sincerely care for and raise him”. Collaboration between teachers and parents creates a consistent, supportive environment. A parent explained, “At home, we also teach independent behavior. My child now showers by himself, wears his own uniform, and buttons his clothes”.

With this collaborative and supportive approach, children at SLB Bina Siwi benefit from therapeutic communication that promotes their social, emotional, and cognitive development, fostering independence and self-confidence.

Teacher and parent cooperation in educating children with special needs

At SLB Bina Siwi, teachers play a crucial role in using therapeutic communication to promote the independence of children with disabilities. This approach combines empathy with effective communication techniques, creating a supportive learning environment. Teachers encourage independence in daily activities like eating, bathing, and dressing, ensuring each child feels valued and supported.

“We always try to communicate with parents about what we teach at school, so they can continue it at home” (Interview with SLB teacher).

This highlights the importance of therapeutic communication that involves not only teachers and students but also parents, ensuring consistent learning both at school and home. Teachers serve as consultants, offering parents strategies to foster independence.

“At first, I didn’t know how to teach independence to my child. After communicating with the teachers and following their advice, I saw many positive changes” (Interview with SLB parent).

This quote reflects the significance of teacher support in guiding parents. Teachers also use praise to motivate children, fostering emotional connections that enhance learning.

“They like to be praised, like ‘come on to school to get smarter,’ ... we have to be smart to make them happy and motivated to attend school” (Interview with SLB teacher).

Verbal praise and emotional support are central to building confidence and independence in children. Teachers adapt their communication style to meet each child’s needs, demonstrating flexibility.

“Children with intellectual disabilities cannot be taught only once; It must be repeated continuously” (Interview with SLB teacher).

This patient and personalized approach ensures that children can master skills at their own pace. Collaboration between teachers and parents is essential for tracking progress and adjusting teaching methods.

“Teachers in SLB cannot apply the learning process like in schools in general ... The first thing teachers apply at school is to make children feel comfortable” (Interview with SLB teacher).

Regular meetings between teachers and parents foster open communication, helping children thrive both emotionally and academically. This partnership between home and school is key to the holistic development of children with intellectual disabilities at SLB Bina Siwi.

Obstacles in the learning process in special schools

The learning process at Sekolah Luar Biasa (SLB) Bina Siwi faces unique challenges, especially when teaching children with intellectual disabilities. One major obstacle is managing the children's mood during the learning process. Since these children often arrive at school in a bad mood, teachers must make extra efforts to stabilize their emotions for effective learning.

"If we keep them in a good mood all the time, it's impossible because sometimes even at home they are not in the mood to go to school, so at school, it is quite difficult to restore or change their mood" (Interview with SLB teacher).

This statement highlights the need for therapeutic communication, where teachers use empathy and understanding to respond to the children's mood changes. Techniques like active listening and emotional support are crucial in overcoming these challenges. Another challenge is the need for repetition in teaching. Children with intellectual disabilities require repeated lessons to fully grasp new concepts, which demands patience and persistence from teachers.

"Children with intellectual disabilities cannot be taught just once ... So, the repetition of each lesson or skill must always be repeated so that they can apply it" (Interview with SLB teacher).

Repetition aligns with therapeutic communication principles, helping children internalize information at their own pace. Teachers also face tantrums, which can disrupt the learning process. Recognizing when to pause and give children time to calm down is essential.

"There is no learning process for children who are having tantrums, because they cannot communicate and certainly cannot accept what the teacher teaches" (Interview with SLB teacher).

Therapeutic communication helps create a calm and supportive environment for children to refocus on learning after such episodes. Making children feel safe and comfortable at school is another obstacle, as fear of a new environment can hinder their adaptation and learning.

"The first obstacle when doing the teaching and learning process is how to make children feel at home at school and without being waited on by their parents" (Interview with SLB teacher).

Using affectionate interactions and consistent routines, teachers build trust, helping children feel secure and ready to learn. Teachers must also navigate challenges related to assertiveness, as children with intellectual disabilities require a more flexible and understanding approach compared to regular schools.

"Assertiveness cannot be used to train or teach children with intellectual disabilities because their IQ is different from other normal people" (Interview with SLB teacher).

This underscores the importance of adapting teaching methods to each child's individual needs. Despite resource and time limitations, teachers at SLB Bina Siwi apply therapeutic communication to overcome these challenges. Collaboration with parents and the school community is essential to support the optimal development of these children, ensuring they learn and grow in a nurturing and understanding environment.

Discussion

This study found that the high level of acceptance and understanding demonstrated by teachers and parents towards children with intellectual disabilities at SLB Bina Siwi is pivotal to their educational success. Such acceptance forms a fundamental component of the educational process for these children, as the positive attitudes of teachers and parents can significantly enhance the overall learning experience and academic outcomes for the students [28]. When children feel accepted and supported by their environment, they tend to be more open to learning and more motivated to participate in school activities. The consistent use of therapeutic communication enhances this positive atmosphere, creating a foundation of trust that promotes both engagement and emotional growth.

The individualized and customized approach to teaching at SLB Bina Siwi demonstrates the importance of flexibility and adaptation in educating children with intellectual disabilities. Teachers at this school use a highly personalized approach tailored to each child’s needs. No one method is applied uniformly; Teachers must adapt to the uniqueness of each child. For example, some children respond positively to praise, while others require a different approach, such as unique timing or individualized treatment. By implementing adaptive communication techniques, teachers not only address cognitive development but also encourage children’s independence, helping them become more confident in navigating their learning journey. The findings underscore that education in SLB is not just about cognitive skills but also adaptive and emotional skills, which are crucial for long-term success.

Another unique approach found at Bina Siwi SLB is the integration of independence and emotional warmth. Teachers at this school not only teach practical skills but also create an environment of compassion and emotional support. They combine teaching independence with providing emotional warmth, such as giving praise or extra attention. Such a combination not only aids skill development but also aligns with therapeutic communication principles, where emotional nurturing supports the learning process, fostering resilience among children. This suggests that a balance between fostering autonomy and emotional support is key to achieving success in special education.

Collaboration between teachers and parents at SLB Bina Siwi exemplifies a cooperative and supportive approach to educating children with special needs. Through this collaboration, teachers and parents can create an environment where children feel understood and supported, which is crucial for their growth and learning [29]. Despite limitations in resources, Bina Siwi SLB can maintain an effective learning environment through close coordination between teachers and parents. Such coordination not only reinforces learning outcomes but also helps children adapt more effectively across different settings, emphasizing that consistent communication often outweighs material resources in achieving educational success.

Specific challenges and solutions in the education of children with disabilities were also identified in this study. One of the biggest challenges is maintaining children’s motivation and interest in learning, which often fluctuates. SLB Bina Siwi teachers apply various creative strategies, such as providing small challenges with simple rewards, to keep children’s interests high. These strategies are not only motivational but also reflect therapeutic communication’s core focus on addressing both emotional and cognitive needs, allowing for sustained engagement. This highlights the need for a more dynamic and responsive approach to students’ emotional and motivational needs, which differs from the more rigid approach in many other education systems.

Therapeutic communication plays a central role in overcoming these challenges. By using therapeutic communication techniques, teachers can connect with students on a deeper level, building trust and better understanding. This approach allows teachers to respond more appropriately to students’ emotional needs, creating a more conducive learning environment [30]. Parental involvement is also crucial in the education of children with intellectual disabilities. When parents actively participate and understand their children’s unique needs, they are more likely to collaborate effectively with teachers in implementing educational strategies [28, 29]. Active involvement not only supports academic outcomes but also reinforces therapeutic communication methods, providing consistent emotional and educational support across home and school settings. This parental involvement reduces the stress and anxiety that parents often feel in parenting children with intellectual disabilities [31].

Parental involvement also contributes to children’s increased independence at home, which is important to support the learning process at school. When parents can continue the therapeutic communication practices initiated at school, children receive more consistent and comprehensive support, which is crucial for their emotional and social development [32, 33]. However, this study also found some obstacles in the learning process at SLB Bina Siwi. The main challenge is stabilizing children’s moods during lessons, as they often arrive at school already in a negative emotional state. Teachers must work diligently to restore their mood to create an effective learning environment. Adjusting communication strategies in real-time, such as using calming tones or gentle prompts, helps manage these emotional shifts and maintains a supportive atmosphere. This requires great flexibility and adaptability from teachers, who must constantly modify their teaching methods to align with the student’s emotional and cognitive states [34].

Another obstacle faced by teachers is the need for repetitive instruction, which is essential for solidifying children’s understanding and retention of information [35]. While repetition may be challenging, it also serves as a tool for reinforcing both knowledge and confidence as children become more familiar with the material and feel a sense of mastery. This process, although demanding, aligns well with therapeutic communication’s emphasis on consistency and patience.

Managing tantrum behavior among children with intellectual disabilities presents an additional challenge. Teachers must be sensitive to each child’s emotional state, pausing when necessary to allow for calming before resuming lessons. Limited resources at SLB Bina Siwi also pose significant challenges. Teachers often need to innovate and adjust their methods to accommodate the available resources while still providing effective learning experiences. Therapeutic communication becomes even more essential here, helping teachers maximize the impact of their interactions despite resource constraints [36].

In addition to resource limitations, teachers at SLB Bina Siwi also face challenges in adapting their teaching methods to each child’s individual needs. This requires great flexibility and the ability to adapt teaching strategies quickly based on children’s responses and progress. Therapeutic communication assists teachers in navigating these challenges by providing a framework to listen better and respond to children’s emotional and cognitive needs.

This research shows that the successful education of children with intellectual disabilities relies heavily on a close partnership between teachers and parents. A positive and collaborative relationship between the two parties allows for the continuous exchange of information and the development of more effective educational strategies. This helps children thrive academically and improves their emotional well-being by creating a safe and supportive environment. Although this study was limited to one school, the findings provide important insights into the importance of therapeutic communication and collaboration between teachers and parents in educating children with intellectual disabilities. Further research is needed to understand how these practices can be applied across different educational contexts. This includes further exploration of how differences in culture, school resources, and individual backgrounds affect the effectiveness of therapeutic communication and collaboration in special education.

It is recommended that further research be conducted across different school contexts and environments to gain deeper insights into the differences in educational practices and collaboration in educating children with intellectual disabilities. In addition, the government and educational institutions should develop more inclusive and supportive policies for children with special needs by ensuring adequate resource allocation and providing ongoing training for educators. The limitations of this study, including its focus on one institution, suggest that a broader policy framework is needed to ensure the sustainability and scalability of adaptive teaching methods and therapeutic communication strategies. Future research should also examine the long-term impact of these strategies on children's academic achievement, emotional development and social integration, to ensure that adaptive education truly meets the needs of the whole student. This will help ensure that every child has an equal opportunity to learn and thrive in a nurturing and inclusive environment, regardless of their limitations.

Conclusion

The research findings show that flexible and individualized approaches to teaching and therapeutic communication play an important role in supporting the academic and emotional development of children with intellectual disabilities.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Tribhuwana Tunggadewi University, Universitas Mercubuana Yogyakarta, and Bandar Lampung University for their support during this research. We also gratefully acknowledge the teachers and parents of Bina Siwi SLB students for their cooperation and valuable input in making this research a success.

Ethical Permissions: This research adhered to all ethical guidelines and standards. Since the study focused on gathering opinions from informants through interviews and observations without conducting any experiments or interventions. Additionally, full informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their confidentiality was strictly maintained throughout the study. Therefore, no ethical issues arose during the research process.

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing is declared by the authors.

Authors' Contribution: Qorib F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Original Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Nurdiarti RP (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Septiani F (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Setiawan R (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit agencies.

Article Type: Qualitative Research |

Subject:

Health Communication

Received: 2024/09/4 | Accepted: 2024/10/25 | Published: 2024/11/1

Received: 2024/09/4 | Accepted: 2024/10/25 | Published: 2024/11/1

References

1. Glasson EJ, Forbes D, Ravikumara M, Nagarajan L, Wilson A, Jacoby P, et al. Gastrostomy and quality of life in children with intellectual disability: A qualitative study. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(10):969-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2020-318796]

2. Zashchirinskaia OV. Specificities of communication in children with intellectual disorders. J Intellect Disabil Diagn Treat. 2020;8(4):602-9. [Link] [DOI:10.6000/2292-2598.2020.08.04.2]

3. Noviyanti AD, Tarsidi I, Ginintasasi R, Mutaqin RS. The effectiveness of token economy in improving adaptive daily living for children with intellectual disability. Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Psychology and Pedagogy-"Diversity in Education" (ICEPP 2019). Paris: Atlantis Press; 2020. [Link] [DOI:10.2991/assehr.k.200130.068]

4. Maïano C, Hue O, April J. Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(5):1018-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jar.12606]

5. Pesau HG, Widyorini E, Sumijati S. Self-care skills of children with moderate intellectual disability. J Health Promot Behav. 2020;5(1):43-9. [Link] [DOI:10.26911/thejhpb.2020.05.01.06]

6. Carter EW, Lane KL, Cooney M, Weir K, Moss CK, Machalicek W. Parent assessments of self-determination importance and performance for students with autism or intellectual disability. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;118(1):16-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1352/1944-7558-118.1.16]

7. Amangeldinovna IT, Kulmagambetovna SA, Abuovna MG, Amanovna MA. Social media communicative skills of younger students with intellectual disabilities in science education course. World J Educ Technol Curr Issues. 2021;13(3):450-66. [Link] [DOI:10.18844/wjet.v13i3.5953]

8. Susilowati L, Rustiyaningsih A, Hartini S. Effect of self development program and training using video modeling method on dressing skills in children with intellectual disability. Belitung Nurs J. 2018;4(4):420-7. [Link] [DOI:10.33546/bnj.331]

9. Kuzu A, Cavkaytar A, Odabaşı HF, Erişti SD, Çankaya S. Development of mobile skill teaching software for parents of individuals with intellectual disability. Turk Online J Qual Inq. 2014;5(2). [Link] [DOI:10.17569/tojqi.24629]

10. Endo S, Asano D, Asai H. Contribution of static and dynamic balance skills to activities of daily living in children with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2024;37(3):e13236. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jar.13236]

11. Jeoung B. Motor proficiency differences among students with intellectual disabilities, autism, and developmental disability. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14(2):275-81. [Link] [DOI:10.12965/jer.1836046.023]

12. Schluchter T, Nagel S, Valkanover S, Eckhart M. Correlations between motor competencies, physical activity and SELF‐CONCEPT in children with intellectual disabilities in inclusive education. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2023;36(5):1054-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jar.13115]

13. Yao L, Li P, Wildy H. Health-promoting leadership: Concept, measurement, and research framework. Front Psychol. 2021;12:602333. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.602333]

14. Makharadze T, Kitiashvili A, Bricout JC. Community-based day-care services for people with intellectual disabilities in Georgia: A step towards their social integration. J Intellect Disabil. 2010;14(4):289-301. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1744629510393186]

15. Arzeen N, Irshad E, Arzeen S, Shah SM. Stress, depression, anxiety, and coping strategies of parents of intellectually disabled and non-disabled children. J Med Sci. 2020;28(4):380-3. [Link] [DOI:10.52764/jms.20.28.4.17]

16. Bates A, Forrester‐Jones R, McCarthy M. Specialist hospital treatment and care as reported by children with intellectual disabilities and a cleft lip and/or palate, their parents and healthcare professionals. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(2):283-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jar.12672]

17. Armstrong J, Elliott C, Davidson E, Mizen J, Wray J, Girdler S. The power of playgroups: Key components of supported and therapeutic playgroups from the perspective of parents. Aust Occup Ther J. 2021;68(2):144-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1440-1630.12708]

18. Ghanbari-afra L, Ghanbari-afra M. Occupational stress of nurses and its related factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2023;16(10):774-85. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/qums.16.10.949.9]

19. Boesley L, Crane L. 'Forget the health and care and just call them education plans': SENCOs' perspectives on education, health and care plans. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2018;18(S1):36-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1471-3802.12416]

20. Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Psychological well-being of caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities: Using parental stress as a mediating factor. J Intellect Disabil. 2011;15(2):101-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1744629511410922]

21. Fenning RM, Baker JK, Baker BL, Crnic KA. Parent-child interaction over time in families of young children with borderline intellectual functioning. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(3):326-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0036537]

22. Rosenthal M. Qualitative research methods: Why, when, and how to conduct interviews and focus groups in pharmacy research. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2016;8(4):509-16. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cptl.2016.03.021]

23. Small ML. What is "qualitative" in qualitative research? Why the answer does not matter but the question is important. Qual Sociol. 2021;44(4):567-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11133-021-09501-3]

24. Borgstede M, Scholz M. Quantitative and qualitative approaches to generalization and replication-A representationalist view. Front Psychol. 2021;12:605191. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.605191]

25. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J. 2009;9(2):27-40. [Link] [DOI:10.3316/QRJ0902027]

26. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. California: SAGE; 2006. [Link]

27. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. California: SAGE; 2016. [Link]

28. Ummah US, Tahar MM, Yasin MHBM. Parents' perspective towards inclusive education for children with intellectual disabilities in Indonesia. Paris: Atlantis Press; 2021. [Link] [DOI:10.2991/assehr.k.211210.006]

29. Mushtaq A, Inam A, Abiodullah M. Attitudes of parents towards the behavioural management of their children with intellectual disability. Disabil CBR Incl Dev. 2015;26(3):111-22. [Link] [DOI:10.5463/dcid.v26i3.439]

30. Zulfiana U, Achni Fathurrahman A, Normalasari N, Nurul Milah W. Disaster mitigation for students with intellectual disabilities. KnE Soc Sci. 2024 Feb:45-58. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/kss.v9i5.15162]

31. Bhattacharyya R, Ghoshal MK, Sanyal D, Bhattacharyya S, Majumder S, Mondal SK. Magnitude of problem of persons having intellectual disability its impact on parents and their unmet needs in Indian subcontinent. Bengal J Psychiatry. 2015;4(1):34-9. [Link] [DOI:10.51332/bjp.2015.v20.i1.42]

32. Arvin H, Rohbanfard H, Arsham S, Moghadasi M. Physical activity reduces the malondialdehyde level in boy children with intellectual disability. Pathobiol Res. 2022;25(1):51-6. [Link]

33. Monteiro MJ. Individualizing the autism assessment process: A framework for school psychologists. Psychol Sch. 2022;59(7):1377-89. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pits.22624]

34. Goodwin J, Behan L, O'Brien N. Teachers' views and experiences of student mental health and well-being programmes: A systematic review. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;33(1-3):55-74. [Link] [DOI:10.2989/17280583.2023.2229876]

35. Badu E. Experiences of parents of children with intellectual disabilities in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. J Soc Incl. 2016;7(1):20-30. [Link] [DOI:10.36251/josi100]

36. Islam MA, Rahman MdA, Akhtar S. Psychosocial impact of parenting children with intellectual disabilities in Bangladesh. Int J Public Health Sci. 2022;11(1):211. [Link] [DOI:10.11591/ijphs.v11i1.21072]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |