Volume 11, Issue 5 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(5): 733-742 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mardalena I, Wahyuni H, Wastutiningsih S. Stakeholders’ Communication of COVID-19 Pandemic in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (5) :733-742

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73741-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73741-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Health Polytechnic Ministry of Health Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2- Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Coordination [MeSH], Communication [MeSH], COVID-19 [MeSH], Indonesia [MeSH], Phenomenology [MeSH], Stakeholder [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 706 kb]

(3484 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1275 Views)

Full-Text: (203 Views)

Introduction

During the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, day by day, the number of COVID-19 cases has been increasing and has affected 215 countries worldwide [1]. By August 31, 2022, the total number of confirmed cases in the Special Region of Yogyakarta had reached 224,382 individuals. Among them, 5,930 people had sadly lost their lives due to COVID-19. As of that date, the mortality rate stood at 2.64%, with a recovery rate of 97.07%. These confirmed cases were identified through testing conducted on a total of 2,799,507 individuals, encompassing contact tracing and travel-related examinations [2].

The increasing number of COVID-19 cases in the Special Region of Yogyakarta has raised concerns among various stakeholders because the uncontrolled situation of the pandemic could lead to a crisis. A crisis is characterized by chaotic and abnormal conditions, posing significant risks if intervention is not taken to rectify the situation. Communication is a key factor contributing to this crisis. Effective communication is also a crucial element in disaster management, including the handling of COVID-19. The government's role in disaster management governance places them at the forefront, with the responsibility for all planning and implementation of disaster management [3].

Effective communication is a crucial pillar for a nation to manage health emergencies. It involves clear, timely, transparent, and well-coordinated information provided by both central and local governments before, during, and after health emergencies [4]. The success of COVID-19 disaster mitigation relies heavily on communication systems between government and non-government entities, the public, and private sectors. Government agencies, particularly health departments, need to be present and responsive during crises like pandemics [5]. Ineffective government communication can cause confusion, public misconceptions, and serious errors in responding to evolving health threats, thereby prolonging the pandemic [6].

An interesting lesson on effective risk communication for COVID-19 prevention can be drawn from Wuhan, China. As of May 8, 2020, when the outbreak initially occurred, reported a total of 84,415 confirmed cases with 4,643 deaths, a notably lower figure compared to the United States, which recorded 1,215,571 cases and 67,146 deaths [7]. Another successful example in handling COVID-19 is South Korea, which managed to keep the death rate due to the coronavirus at a relatively low 2.1% without implementing a lockdown [8]. Norway's government successfully controlled the pandemic swiftly by adopting a suppression strategy followed by a control strategy. This was based on a collaborative and pragmatic decision-making approach, effective public communication using abundant resources, crisis management skills, and gaining legitimacy from the public [9].

The severity of the infection is determined by the virulence of the COVID-19 causative agent, which can be estimated by assessing the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) in all infected cases. CFR estimates can influence policy decisions and efforts to control and mitigate COVID-19. Control efforts, involving political decisions such as travel restrictions, containment measures, and mitigation strategies, were based on data [10]. During the early stages of the pandemic, the government did not use CFR data in policymaking for different community conditions. In the early stages of managing the outbreak, the government initially adopted an economic developmental mindset, potentially sacrificing the health emergency situation [11]. The lack of transparency in information during the early phases diminished the effectiveness of risk communication and broadened the impact caused by the virus [12].

Facing the COVID-19 pandemic is a novel challenge for both the Indonesian government and the Special Region of Yogyakarta. There is no prior experience in dealing with such a pandemic. The significant escalation of its impact and high mortality rates requires proper coordination and collaboration. To prevent the situation from becoming a crisis, the Health Department must make informed decisions for effective risk communication during a pandemic. It is crucial to assess communication aspects throughout the pandemic cycle in each phase and explore ways to enhance the Health Department's role as the primary communicator in Yogyakarta's health development. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore the coordination and communication governance processes utilized by the Yogyakarta provincial government in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants and Methods

Study design

This study, employing a qualitative research design, was carried out using a phenomenological approach in 2023-2024.

Participants

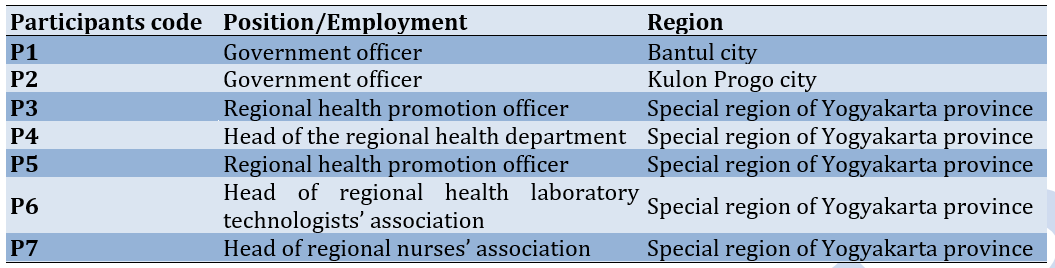

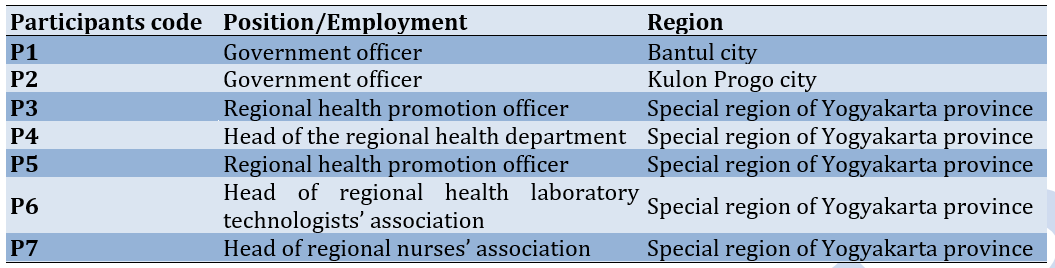

The participants were individuals or actors who possessed comprehensive knowledge of the issue and were directly involved in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. The statistical population of the study included a diverse range of stakeholders, including various institutions, professional organizations, and task forces collaborating with the Yogyakarta Provincial Health Office to address the challenges posed by COVID-19 in the region. The samples were selected by a purposive sampling method (n=7; Table 1).

Table 1. ParSticipants description

The sample size was determined by snowball sampling.

The inclusion criteria for key informants in this study on health development communication by the Yogyakarta Provincial Health Office in COVID-19 mitigation were as follows: a) Officials from the provincial health office involved in COVID-19 control; b) Representatives from organizations actively engaged in COVID-19 mitigation; c) Partners consisting of institutions, experts (doctors/nurses/epidemiologists), and professional organizations involved in COVID-19 mitigation; d) The public or community, which is the target audience of the Health Office's information.

Data collection

Data were collected using in-depth interviews and observations.

The structured and unstructured interviews were selected to obtain verbal statements or opinions from informants directly involved in the coordination, collaboration, decision-making, and communication processes in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Yogyakarta. The interview method was utilized to collect primary data, which involved obtaining information directly from informants for subsequent processing.

Observation involved direct observation of the research subject, specifically focusing on the stages of coordination, collaboration, decision-making, and health communication processes in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Yogyakarta. The researcher systematically observed and recorded elements, symptoms, and actual behaviors of the involved subjects to ascertain the real conditions.

Data analysis

Data were manually analyzed using three interrelated processes including data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing/verification [13]. The analysis in this study also employed the Colaizzi method as a method for analyzing qualitative research data using a phenomenological approach [14].

The credibility was assessed through triangulation methods. To enhance the study's credibility, all interviews were recorded using an electronic audio recorder to ensure all information was captured accurately. Subsequently, the interview transcripts were shared with the participants for validation. The researchers translated the interview transcripts to minimize any risk of imprecise meaning. Dependability was established through an agreement between the two researchers regarding the data analysis process, ensuring consistent and reliable results. To ensure conformability, clear research steps were provided, and the research process was transparent.

Ethical permission for this research was obtained on September 2021 with protocol number e-KEPK/POLKESYO/0724/IX/2021 from the Ethical Committee of Health Research of Health Polytechnic Ministry of Health Yogyakarta. Before collecting data, the researchers obtained informed consent from all study participants. Throughout this research, ethical principles such as participant confidentiality and autonomy were strictly upheld. Each participant was granted the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time if they felt uncomfortable, and there were no consequences for doing so.

Findings

The data analysis identified a total of 74 codes, which were grouped into a cluster based on their similarities, forming 18 categories. These 18 categories were then further grouped to create six themes in another cluster.

Theme 1: Training and development of human resources for the management of the crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic was perceived as a newly encountered case throughout history in Indonesia, so the government does not have sufficient experience in handling the COVID-19 pandemic quickly and accurately. This theme was formed from four sub-themes, namely the health care stage in handling, recruitment in human resources fulfillment, and new cases requiring development as the basis for the acceptance stage towards cases.

Healthcare stage in handling: The COVID-19 pandemic was managed comprehensively, covering prevention, treatment, and early rehabilitation. Promotions include information on prevention, self-care, rehabilitation, service locations, and vaccination details. Identification, planning, and continuous monitoring of cases, infrastructure, and collaborations are integral. Reporting on contamination, deaths, clusters, and bed occupancy was done promptly through various media. Ongoing evaluation ensures the effectiveness of processes, programs, and policies. Immediate feedback was provided for monitoring, reporting, and coordination actions.

“The message focuses on various control stages, with emphasis on promotive and preventive information due to better public reception compared to curative information." (P2)

"Verification serves as feedback. For example, in recovery cases, individual clicks were required, but group clicks received immediate clarification, indicating prompt feedback." (P5)

"The provincial task force, not the health department itself, provides regular updates on the current situation, including the number of affected individuals, recoveries, and exposures." (PTE2)

Recruitment in human resources fulfillment: The demand for human resources increased with increasing incidents, especially in curative, rehabilitation, and preventive stages, necessitating additional healthcare personnel. To meet these needs, voluntary recruitment through relevant institutions, possibly during student fieldwork, was essential for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Our policy processes output to utilize all available resources, including human resources." (P1)

"For health partners, each vaccination requires many healthcare workers. However, our province lacks sufficient human resources for mass vaccinations of 3,000 to 6,000 people per session." (P2)

"Nursing and midwifery academy students serve as volunteer tracers during internships, assisting health centers in tracking and recording." (P3)

Theme 2: The communication governance of the Yogyakarta Special Region's government

During the pandemic, initial funding for risk communication came from the local government. In subsequent periods, support for information channels came from various sources, including the Ministry of Health, other government ministries and agencies, educational institutions, and community organizations. The communication governance of the Yogyakarta Special Region's government can be categorized into four key themes, which encompass effective information through easily accessible applications, comprehensive information from reliable sources, diverse media for socialization meetings during coordination, and the dissemination of recommendations.

Effective information through easily accessible applications: All information related to the COVID-19 pandemic was readily and freely accessible through various social media channels to ensure that the absorption of information and coordination implementation can receive swift responses and follow-ups. Information via software applications can be accessed by a portion of the population, while areas less accessible through such applications can receive information through television channels or direct advisories from competent personnel. Enhancing public knowledge and understanding of potential risks was essential so that the public can anticipate and address these risks through various informational media.

"It's quite good, actually. It's quite good. So, the province utilizes all available media to convey information, from preventive and promotional aspects to rehabilitation. This means that with the presence of shelters in Yogyakarta Special Region, they are available everywhere." (Participant 1)

"But it's also like this; Since we verify it every day, we need to verify it, right? So, it needs to be uploaded on the health department's website. Actually, the data can be accessed immediately by anyone, it's available to the public at dinkes.kulonprogokab.go.id_corona." (P2)

"So, eventually, we created a COVID-19 bulletin. The schedule can be updated, and it's been published every day. The bulletin is created every day, and there have been so many editions; I've lost count. It's due to be published around 5 PM today." (P5)

Comprehensive information from reliable sources: Before being published, all information was subject to validation by third-level authorities to prevent the spread of misinformation or hoaxes. As part of this process, it has been established that all forms of information and complaints from various sectors are consolidated and coordinated before publication. The public eagerly awaited crucial information that can serve as guidance in addressing the challenges posed by the impact of COVID-19. Information related to vaccination, in particular, was highly anticipated by the public, as it helped them make informed decisions regarding the vaccination process. This sentiment was illustrated by the following statements from participants:

"Like earlier, there has to be validation from the relevant third-level authorities. Once it's validated, it can be released. So, when it comes to coordination, internal coordination is strong, then there's validation, and there's also communication with districts/cities, and only then it's released." (P3)

"Information provided to the public is processed and consolidated into a procedure that can be collectively implemented; That's the first step." (P4)

"So, it's basically a team decision, whether it's appropriate or not. Like this. Okay, let's disseminate it, disseminate it all. The core of the message is this, and the format can be varied, but it must be this, and it must be circulated immediately." (P5)

Diverse media for socialization meetings during coordination: The communication and coordination process was carried out both directly and indirectly. Virtual communication with the public, especially during tense situations, is employed, while in-person communication was conducted alongside the personnel involved in managing the pandemic. The following statements from participants illustrate this:

"When the situation was still tense, it remained the same because the health department didn't switch to remote work; We continued to go to the office. Besides, there was no remote process; There was no online. We held meetings in person, even the COVID task force met in person. No one was working from home or doing it online." (PTE1)

"But after some time had passed at the beginning of the COVID situation, and there were directives from the health authorities, the Yogyakarta regional government began to engage in what's called risk communication. The first step, of course, was to help the public understand what COVID is, how to prevent it, and what to do if they contracted it." (P3)

"Then, there are others, like Orari and so on. So, we utilize our potential, and coordination is there. How do we coordinate all of them? We use WhatsApp groups or direct messages, and so on. So, we don't follow the conventional procedure of having meetings; It's not like that because the circumstances are different." (P5)

Dissemination of recommendations: Numerous pieces of information needed to be conveyed to the public because they required updates on the COVID-19 situation. With this demand, it was essential to provide information regarding positive recommendations on how to collectively address the COVID-19 pandemic. The following statements from participants exemplify this:

"Well, from our observations at the health department, the information that the public needs most is the development of cases. That's what the public eagerly awaits, the updates on cases, whether they're new positive cases, recoveries, or fatalities. That's the information they need." (P1)

"I believe that, normatively, several pieces of information need to be clarified, and it must be packaged as a benefit for the public, which is crucial. We shouldn't have situations where, at the beginning, people were saying, 'I'm afraid I'll get COVID if I participate in this event.' That's kind of funny, but the key is that we have to communicate that by complying with these measures, you're protecting the community." (P2)

"Yes, for those who are in isolation at home or in shelters, they need further guidance. Even those in home isolation need instructions on how not to transmit the virus. Home isolation is often not possible due to the confined living spaces and the number of occupants. In such cases, we direct them to the regional government's isolation facilities." (P3)

Theme 3: Cross-Sectoral Support According to Authority in Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic

The handling of the COVID-19 pandemic exhibited discrepancies in implementation among different agencies, especially in transportation services, despite unified guidelines. These differences posed challenges. Cross-sectoral involvement provided essential support in managing the pandemic. Various government sectors, private institutions, educational bodies, and community groups contributed according to their authority and roles. They independently engaged in promotional, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative activities.

Collaboration with Cross-Sectoral Partners. The health department involved multiple sectors, both health and non-health, in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Cooperation included voluntary community participation in addressing local issues through coordination with relevant sectors. Community organizations participated in promotional, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative efforts, such as monitoring local conditions, controlling entry points, assisting with patient transport, and distributing food. Quick and direct coordination was facilitated through various media. Educational institutions, both public and private, health and non-health agencies, religious leaders, and the military were consistent partners in providing services. Policy implementation was interconnected between central and local levels.

"We have numerous entities involved in risk communication, including social and professional entities. Collaboration spans formal bureaucracy, social, academic, and other sectors." (P1)

"Media collaboration involves cross-sectors, districts, institutions like schools, religious centers, markets, and others. For example, markets work with APPSI, religious centers with the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and schools with the Education Office." (P2)

"Experiences from places like Kulon Progo can inform provincial policies and vice versa. This interconnection influences implementation." (P5)

Authority According to Functional Roles

Each sector involved in the pandemic response operated within its defined role, executing tasks according to their job descriptions. Health promotion was conducted by the health promotion division, with task allocation based on each sector’s competencies. Most sectors provided information on their activities, monitoring results, and evaluations during the pandemic response.

"Roles within the task force were designated according to each sector’s instructions, not solely health." (P5)

"Our organization (Association of Indonesian Medical Laboratory Technologists) policy greatly assisted the health department by training members as frontline workers for sample collection and lab tests, crucial for COVID-19 testing." (P1)

" Our organization (Indonesian National Nurses Association) does not handle data processing; the health department collects data from related agencies like district health offices and health facilities." (P2)

Even Distribution of Support

Managing the pandemic required significant resources, leading to increased funding needs. Numerous organizations and institutions provided support, including sponsorships. For instance, some institutions provided operational support for vaccination, free transportation for those with limited access, and funding from educational institutions for operational costs. Support distribution was based on identified needs and mapped out accordingly.

"During significant events like a pandemic, standardized resources are essential to prevent risks. We leverage available resources from communities and technology." (P1)

"Mass vaccination events had operational costs covered by sponsors like Traveloka and Grab, including waste management and transportation for disabled individuals. Universities also provided financial support for operations." (P2)

"Community collaboration is vital for implementing health department policies." (P2)

Dilemmas and Challenges

Despite unified guidelines, differences in pandemic management still existed. Protocol discrepancies among agencies for travel control led to conflicts. Political and publicity interests sometimes resulted in information being withheld. The government faced dilemmas between adhering to regulations and meeting public needs. Challenges included uneven distribution of logistics and public reluctance to accept healthcare workers in their communities.

"Initially, COVID-19 case numbers were sensitive and kept confidential, reflecting early pandemic communication challenges." (P1)

"Obstacles included misinformation and the desire to broadcast accurate information widely." (P2)

"Discrepancies in health protocol enforcement among transportation modes (terminals, stations, airports) despite clear national task force guidelines highlighted implementation issues." (P3)

Theme 4: Central Guidelines as Decision-Making Basis for Regional Leaders

All decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic were based on central guidelines, which regional leaders adapted into local policies. In urgent situations requiring new decisions, local input was swiftly communicated to higher levels for prompt responses. Policymakers and experts acknowledged that the pandemic response was effective and swift, with monitoring, identification, information dissemination, and coordination occurring directly and responsively.

Regional Leaders as Policy Makers Based on Central Guidelines

Management of the COVID-19 pandemic, from planning to evaluation, was conducted by each region based on central decisions, albeit developed locally. Coordination within each region was centralized under a single command, led by the deputy governor or deputy regent, who acted as the task force head. When modifications in handling the pandemic were necessary, they were communicated to central authorities for approval. Once approved, these modifications became national regulations and were subsequently adapted into local policies.

"Risk communication during the pandemic benefited from a unified focus, enabling centralized management like a single command point." (P1)

"COVID-19 control at the local level is based on central policies, including Ministry of Health directives and national task force regulations, which are then adapted into regional regulations." (P3)

"Provincial guidelines form the basis for implementation at the local level, with consistent government policies across central, provincial, and local levels driving community mobilization." (P5)

Maintaining Quality Through Commitment

Policymakers and experts recognized that Indonesia’s COVID-19 response was more effective compared to other countries. Yogyakarta (DIY) received positive recognition for its pandemic management, despite occasional increases in cases due to its popularity as a tourist destination. The region’s coordination and collaboration enhanced the quality of its pandemic response. Both governmental and non-governmental sectors, including the community, demonstrated a high commitment to collaboration, contributing to the successful pandemic management in DIY.

"Despite challenges, Indonesia’s COVID-19 control was successful compared to other countries." (P3)

"DIY received praise for its COVID-19 management, though increased vigilance was required due to its status as a tourist destination." (P1)

"DIY’s health department excelled in COVID-19 control through coordination and collaboration with various sectors, including government and non-health sectors." (P2)

Rapid Response to Opportunities

Quick and direct responses were crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collection, incident analysis, emergency policy-making, and information dissemination were conducted rapidly. Policymakers and experts recognized this responsiveness as essential for effective pandemic management. Coordination and information were managed through multiple programs using various types of media.

"Risk communication design during the pandemic required speed in data collection, analysis, information dissemination, and innovation." (P1)

"Despite busy schedules, the task force's effective and timely responses were facilitated by early information gathering and coordination." (P5)

"The response was very good, with continuous coordination with INNA (Indonesian National Nurses Association) throughout the pandemic." (P2)

Theme 5: Community Leaders as Role Models Influencing Public Behavior

In managing the COVID-19 pandemic, community trust in the government is crucial. Community leaders play a vital role in fostering awareness and ensuring adherence to regulations established by central authorities. Initially, skepticism about the pandemic threat led to increased spread. Over time, prolonged pandemic conditions caused public fatigue, reducing compliance with ongoing regulations and attentiveness to government communications. In Yogyakarta (DIY), where cultural values are strong, the populace is more inclined to follow directives from Sri Sultan.

Trust and Stimuli to Remain Active

The prolonged nature of the COVID-19 pandemic led to public fatigue and diminished attention to pandemic-related information. Initial efforts to engage volunteers and donors were high due to strong awareness, but this enthusiasm waned over time. Policymakers needed to continually foster trust and raise awareness.

"The gap from not being afraid to being afraid has decreased over time due to social fatigue and reduced media focus on COVID, leading to a diversification of information sources and decreased focus on the pandemic." (P1)

"All layers of society in DIY initially had high enthusiasm due to strong awareness, but over time, interest decreased, as evidenced by the reduced engagement with shared information." (P2)

"Continuous efforts to involve the community are necessary, depending on the cutoff point, such as adherence to self-testing when symptomatic, which needs constant reinforcement." (P5)

Culturally Appropriate Role Models Have a Strong Influence

The strong cultural values in Yogyakarta (DIY) mean that directives from the Sultan are more likely to be followed than those from the central government alone. Local cultural leaders, including religious figures and community organization heads, play crucial roles in guiding the community to collectively manage the pandemic.

"The Sultan's figure is highly influential. Initially, people were reluctant to follow health protocols, but a video message from the Sultan significantly improved compliance." (P2)

"Bantul's initiative to set up shelters influenced DIY's policy for all regions to have similar facilities." (P3)

"In rural areas, the Sultan's messages in Javanese were highly effective. His charisma and cultural resonance significantly aided pandemic management efforts." (P1)

Theme 6: Need for Honest and Transparent Information Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic

Effective information management is critical in delivering important information to the public about the COVID-19 pandemic. From the pandemic's onset, people required accurate and comprehensive information about the virus and necessary measures. Transparent communication is essential to build public trust and counter misinformation. Various media platforms can be used to disseminate information widely and facilitate public inquiries.

Accurate Information to Build Trust and Avoid Hoaxes

The public needs reliable information to maintain trust and avoid misinformation. Centralized information management ensures that all disseminated information is accurate and consistent.

"Behavioral data is lacking; only clinical and laboratory data are available. Comprehensive data collection and dissemination are necessary for effective communication." (P1)

"A single point of entry for information ensures its validity, preventing misinformation. Only authorized individuals can disseminate information to avoid bias." (P2)

"Sector collaboration is evident during high case periods, with socialization efforts to enforce compliance with health protocols." (P5)

Essential Information About the COVID-19 Pandemic

The public needs detailed information about COVID-19, including its nature, transmission, management, prevention, and governmental regulations. Accessible information through various media is crucial for the public to stay informed and engage with pandemic management efforts.

"Public transparency about data is necessary. A process for disseminating essential data to the public and creating channels for questions and feedback is important." (P1)

"Key information sought by the public includes case developments, social restrictions, and vaccination details. These areas are crucial and eagerly awaited by the public." (P3)

"Expert findings on epidemiology and transmission must be communicated to the public, aiming to create awareness without causing fear, thus maintaining vigilance." (P1)

Discussion

The objective of this study is to explore the coordination and communication governance processes utilized by the Yogyakarta provincial government in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study is one of the first qualitative investigations involving various stakeholders to delineate the coordination and communication governance procedures in place during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Government policies should not be limited to partial or fragmented measures undertaken in isolation. Ideally, government policies should be comprehensive and integrated. Comprehensive policies are those that are established after a thorough examination of the root causes from their inception to the end. In this regard, it is essential to first assess the initial causes of the issue, and modes of transmission, map the affected areas and residents, and devise strategies to break the chain of transmission, leading to the discovery of a vaccine [15].

The COVID-19 pandemic, as a new outbreak with biopsychosocial and spiritual implications, requires comprehensive handling and collective responsibility to address the challenges. According to previous research, the COVID-19 pandemic is not an entirely new global experience, with occurrences spanning various timelines, ranging from hundreds of years to more recent outbreaks that happened just a few years ago. In general, the community should still remember previous similar outbreaks caused by similar viruses. However, in reality, the community was late in responding, as evidenced by the high number of casualties [16, 17].

The initial spread of the Corona Disease 2019 virus from Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 was extensive, with almost every country reporting the discovery of COVID-19, including Indonesia, which identified cases in early March 2020 [18]. Each country implemented policies based on its unique situation and conditions, resulting in strained relations between some nations. However, the most commonly employed policy was the imposition of lockdowns, believed to be the swiftest strategy for breaking the chain of COVID-19 transmission [19].

Sharing information, sharing resources, and acting together are three key activities in coordination. These three elements are of utmost importance in the coordination process to ensure that each involved party comprehends their roles, understands resource allocation, and subsequently collaborates to achieve common objectives [20]. Coordination and communication are inseparable partners, as are coordination and leadership; They mutually influence each other. In any organizational endeavor, be it small or large, coordination is invariably present because organizational goals involve interconnected components that require coordination [21].

Media plays a vital role in COVID-19 coordination, providing various accessible platforms for disseminating crucial information during the pandemic. Many scholars emphasize the significance of media in addressing the challenges of COVID-19. Mass media and mass communication are essential tools for effectively managing the COVID-19 pandemic and minimizing its global impact. They serve to inform the public about the dangers of COVID-19, how to recognize its symptoms, and the importance of adopting healthy behaviors to prevent infection [22]. Additionally, mass media facilitates the rapid, accurate, and trustworthy dissemination of statistical data, aiding the government in issuing timely warnings. However, there can be negative consequences, such as the spread of misinformation, causing fear and anxiety among the public, and fostering stigmatization of COVID-19-affected individuals [23].

Previous study suggests that many people's non-compliance with government COVID-19 policies is due to cognitive bias, leading to information misinterpretation and flawed decision-making [24]. Other research indicates that some perceive COVID-19 as being exploited for political and hospital economic gains, while others link it to job loss and economic problems. People's pandemic response involves vigilance, adherence or violation of health protocols, and denial of hospital test results. Influencing factors include figures, religious beliefs, knowledge, social habits, mask-wearing, and the sense of security from COVID-19. Modern leadership is intertwined with community presence and shaped by leaders and the local culture [25].

Indonesia, a culturally and religiously rich country, has significant potential to aid the COVID-19 pandemic response. Central Java and Bali, known for their well-preserved cultural and religious traditions, have utilized these values in pandemic response leadership. Bali's leadership draws from cultural values like Tri Hita Karana in Hinduism, while Central Java emphasizes solidarity and the Islamic concept of Hablumminannas. Both leaders employ collaborative and transformational leadership styles. In the integrated approach in Denpasar, the community-based Desa Adat task force aims to reduce and control the spread of COVID-19. Using the Desa Adat as a base allows for the involvement of all community members, not just government efforts [26].

Finally, collaboration among various stakeholders is expected to enhance the effectiveness of COVID-19 management [27]. Existing literature has demonstrated that implementing open-risk communication is challenging and involves difficulties in deciding what to communicate and what not to do. For instance, complete transparency may lead to potential fear among community members [28].

Strengths and limitations

This study offers significant strengths, primarily through its use of a qualitative research design with a phenomenological approach, enabling an in-depth understanding of stakeholder coordination and communication governance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Yogyakarta. The inclusion of diverse informants, such as government officials, healthcare professionals, and community leaders, provides a comprehensive view of the crisis management processes.

However, the study also has limitations. The relatively small sample size of twelve informants may not fully capture the diversity of experiences and perspectives across all stakeholders involved in the pandemic response. Furthermore, the study is context-specific, focusing solely on the Yogyakarta region, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or countries with different socio-political contexts and healthcare infrastructures.

Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the complexities of managing a health crisis and highlights the critical role of effective communication and coordination among stakeholders.

Conclusion

The coordination and communication governance processes utilized by the Yogyakarta provincial government in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic involves 6 main themes including training and development of human resources for the management of the crisis, the communication governance of the Yogyakarta Special Region's government, cross-sectoral support according to authority in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, central guidelines as decision-making basis for regional leaders,

community leaders as role models influencing public behavior, and need for honest and transparent information regarding the COVID -19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their gratitude to the study participants for their keen involvement and generous contributions. They also extend special thanks to the Department of Health in the Special Region of Yogyakarta and Politeknik Kesehatan Kementerian Kesehatan Yogyakarta for their invaluable data support and contributions to the research, as well as to the latter for granting permission to conduct this study.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical permission for this research was obtained on September 2021 with protocol number e-KEPK/POLKESYO/0724/IX/2021 from the Ethical Committee of Health Research of Politeknik Kesehatan Kementerian Kesehatan Yogyakarta.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors affirm that there were no financial or commercial conflicts of interest throughout the conduct of this study and state that they have no competing interests with the funders.

Authors’ Contribution: Mardalena I (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (60%); Wahyuni HI (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%); Wahtutiningsih SP (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This study does not receive any external funding.

During the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, day by day, the number of COVID-19 cases has been increasing and has affected 215 countries worldwide [1]. By August 31, 2022, the total number of confirmed cases in the Special Region of Yogyakarta had reached 224,382 individuals. Among them, 5,930 people had sadly lost their lives due to COVID-19. As of that date, the mortality rate stood at 2.64%, with a recovery rate of 97.07%. These confirmed cases were identified through testing conducted on a total of 2,799,507 individuals, encompassing contact tracing and travel-related examinations [2].

The increasing number of COVID-19 cases in the Special Region of Yogyakarta has raised concerns among various stakeholders because the uncontrolled situation of the pandemic could lead to a crisis. A crisis is characterized by chaotic and abnormal conditions, posing significant risks if intervention is not taken to rectify the situation. Communication is a key factor contributing to this crisis. Effective communication is also a crucial element in disaster management, including the handling of COVID-19. The government's role in disaster management governance places them at the forefront, with the responsibility for all planning and implementation of disaster management [3].

Effective communication is a crucial pillar for a nation to manage health emergencies. It involves clear, timely, transparent, and well-coordinated information provided by both central and local governments before, during, and after health emergencies [4]. The success of COVID-19 disaster mitigation relies heavily on communication systems between government and non-government entities, the public, and private sectors. Government agencies, particularly health departments, need to be present and responsive during crises like pandemics [5]. Ineffective government communication can cause confusion, public misconceptions, and serious errors in responding to evolving health threats, thereby prolonging the pandemic [6].

An interesting lesson on effective risk communication for COVID-19 prevention can be drawn from Wuhan, China. As of May 8, 2020, when the outbreak initially occurred, reported a total of 84,415 confirmed cases with 4,643 deaths, a notably lower figure compared to the United States, which recorded 1,215,571 cases and 67,146 deaths [7]. Another successful example in handling COVID-19 is South Korea, which managed to keep the death rate due to the coronavirus at a relatively low 2.1% without implementing a lockdown [8]. Norway's government successfully controlled the pandemic swiftly by adopting a suppression strategy followed by a control strategy. This was based on a collaborative and pragmatic decision-making approach, effective public communication using abundant resources, crisis management skills, and gaining legitimacy from the public [9].

The severity of the infection is determined by the virulence of the COVID-19 causative agent, which can be estimated by assessing the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) in all infected cases. CFR estimates can influence policy decisions and efforts to control and mitigate COVID-19. Control efforts, involving political decisions such as travel restrictions, containment measures, and mitigation strategies, were based on data [10]. During the early stages of the pandemic, the government did not use CFR data in policymaking for different community conditions. In the early stages of managing the outbreak, the government initially adopted an economic developmental mindset, potentially sacrificing the health emergency situation [11]. The lack of transparency in information during the early phases diminished the effectiveness of risk communication and broadened the impact caused by the virus [12].

Facing the COVID-19 pandemic is a novel challenge for both the Indonesian government and the Special Region of Yogyakarta. There is no prior experience in dealing with such a pandemic. The significant escalation of its impact and high mortality rates requires proper coordination and collaboration. To prevent the situation from becoming a crisis, the Health Department must make informed decisions for effective risk communication during a pandemic. It is crucial to assess communication aspects throughout the pandemic cycle in each phase and explore ways to enhance the Health Department's role as the primary communicator in Yogyakarta's health development. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore the coordination and communication governance processes utilized by the Yogyakarta provincial government in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants and Methods

Study design

This study, employing a qualitative research design, was carried out using a phenomenological approach in 2023-2024.

Participants

The participants were individuals or actors who possessed comprehensive knowledge of the issue and were directly involved in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. The statistical population of the study included a diverse range of stakeholders, including various institutions, professional organizations, and task forces collaborating with the Yogyakarta Provincial Health Office to address the challenges posed by COVID-19 in the region. The samples were selected by a purposive sampling method (n=7; Table 1).

Table 1. ParSticipants description

The sample size was determined by snowball sampling.

The inclusion criteria for key informants in this study on health development communication by the Yogyakarta Provincial Health Office in COVID-19 mitigation were as follows: a) Officials from the provincial health office involved in COVID-19 control; b) Representatives from organizations actively engaged in COVID-19 mitigation; c) Partners consisting of institutions, experts (doctors/nurses/epidemiologists), and professional organizations involved in COVID-19 mitigation; d) The public or community, which is the target audience of the Health Office's information.

Data collection

Data were collected using in-depth interviews and observations.

The structured and unstructured interviews were selected to obtain verbal statements or opinions from informants directly involved in the coordination, collaboration, decision-making, and communication processes in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Yogyakarta. The interview method was utilized to collect primary data, which involved obtaining information directly from informants for subsequent processing.

Observation involved direct observation of the research subject, specifically focusing on the stages of coordination, collaboration, decision-making, and health communication processes in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Yogyakarta. The researcher systematically observed and recorded elements, symptoms, and actual behaviors of the involved subjects to ascertain the real conditions.

Data analysis

Data were manually analyzed using three interrelated processes including data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing/verification [13]. The analysis in this study also employed the Colaizzi method as a method for analyzing qualitative research data using a phenomenological approach [14].

The credibility was assessed through triangulation methods. To enhance the study's credibility, all interviews were recorded using an electronic audio recorder to ensure all information was captured accurately. Subsequently, the interview transcripts were shared with the participants for validation. The researchers translated the interview transcripts to minimize any risk of imprecise meaning. Dependability was established through an agreement between the two researchers regarding the data analysis process, ensuring consistent and reliable results. To ensure conformability, clear research steps were provided, and the research process was transparent.

Ethical permission for this research was obtained on September 2021 with protocol number e-KEPK/POLKESYO/0724/IX/2021 from the Ethical Committee of Health Research of Health Polytechnic Ministry of Health Yogyakarta. Before collecting data, the researchers obtained informed consent from all study participants. Throughout this research, ethical principles such as participant confidentiality and autonomy were strictly upheld. Each participant was granted the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time if they felt uncomfortable, and there were no consequences for doing so.

Findings

The data analysis identified a total of 74 codes, which were grouped into a cluster based on their similarities, forming 18 categories. These 18 categories were then further grouped to create six themes in another cluster.

Theme 1: Training and development of human resources for the management of the crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic was perceived as a newly encountered case throughout history in Indonesia, so the government does not have sufficient experience in handling the COVID-19 pandemic quickly and accurately. This theme was formed from four sub-themes, namely the health care stage in handling, recruitment in human resources fulfillment, and new cases requiring development as the basis for the acceptance stage towards cases.

Healthcare stage in handling: The COVID-19 pandemic was managed comprehensively, covering prevention, treatment, and early rehabilitation. Promotions include information on prevention, self-care, rehabilitation, service locations, and vaccination details. Identification, planning, and continuous monitoring of cases, infrastructure, and collaborations are integral. Reporting on contamination, deaths, clusters, and bed occupancy was done promptly through various media. Ongoing evaluation ensures the effectiveness of processes, programs, and policies. Immediate feedback was provided for monitoring, reporting, and coordination actions.

“The message focuses on various control stages, with emphasis on promotive and preventive information due to better public reception compared to curative information." (P2)

"Verification serves as feedback. For example, in recovery cases, individual clicks were required, but group clicks received immediate clarification, indicating prompt feedback." (P5)

"The provincial task force, not the health department itself, provides regular updates on the current situation, including the number of affected individuals, recoveries, and exposures." (PTE2)

Recruitment in human resources fulfillment: The demand for human resources increased with increasing incidents, especially in curative, rehabilitation, and preventive stages, necessitating additional healthcare personnel. To meet these needs, voluntary recruitment through relevant institutions, possibly during student fieldwork, was essential for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Our policy processes output to utilize all available resources, including human resources." (P1)

"For health partners, each vaccination requires many healthcare workers. However, our province lacks sufficient human resources for mass vaccinations of 3,000 to 6,000 people per session." (P2)

"Nursing and midwifery academy students serve as volunteer tracers during internships, assisting health centers in tracking and recording." (P3)

Theme 2: The communication governance of the Yogyakarta Special Region's government

During the pandemic, initial funding for risk communication came from the local government. In subsequent periods, support for information channels came from various sources, including the Ministry of Health, other government ministries and agencies, educational institutions, and community organizations. The communication governance of the Yogyakarta Special Region's government can be categorized into four key themes, which encompass effective information through easily accessible applications, comprehensive information from reliable sources, diverse media for socialization meetings during coordination, and the dissemination of recommendations.

Effective information through easily accessible applications: All information related to the COVID-19 pandemic was readily and freely accessible through various social media channels to ensure that the absorption of information and coordination implementation can receive swift responses and follow-ups. Information via software applications can be accessed by a portion of the population, while areas less accessible through such applications can receive information through television channels or direct advisories from competent personnel. Enhancing public knowledge and understanding of potential risks was essential so that the public can anticipate and address these risks through various informational media.

"It's quite good, actually. It's quite good. So, the province utilizes all available media to convey information, from preventive and promotional aspects to rehabilitation. This means that with the presence of shelters in Yogyakarta Special Region, they are available everywhere." (Participant 1)

"But it's also like this; Since we verify it every day, we need to verify it, right? So, it needs to be uploaded on the health department's website. Actually, the data can be accessed immediately by anyone, it's available to the public at dinkes.kulonprogokab.go.id_corona." (P2)

"So, eventually, we created a COVID-19 bulletin. The schedule can be updated, and it's been published every day. The bulletin is created every day, and there have been so many editions; I've lost count. It's due to be published around 5 PM today." (P5)

Comprehensive information from reliable sources: Before being published, all information was subject to validation by third-level authorities to prevent the spread of misinformation or hoaxes. As part of this process, it has been established that all forms of information and complaints from various sectors are consolidated and coordinated before publication. The public eagerly awaited crucial information that can serve as guidance in addressing the challenges posed by the impact of COVID-19. Information related to vaccination, in particular, was highly anticipated by the public, as it helped them make informed decisions regarding the vaccination process. This sentiment was illustrated by the following statements from participants:

"Like earlier, there has to be validation from the relevant third-level authorities. Once it's validated, it can be released. So, when it comes to coordination, internal coordination is strong, then there's validation, and there's also communication with districts/cities, and only then it's released." (P3)

"Information provided to the public is processed and consolidated into a procedure that can be collectively implemented; That's the first step." (P4)

"So, it's basically a team decision, whether it's appropriate or not. Like this. Okay, let's disseminate it, disseminate it all. The core of the message is this, and the format can be varied, but it must be this, and it must be circulated immediately." (P5)

Diverse media for socialization meetings during coordination: The communication and coordination process was carried out both directly and indirectly. Virtual communication with the public, especially during tense situations, is employed, while in-person communication was conducted alongside the personnel involved in managing the pandemic. The following statements from participants illustrate this:

"When the situation was still tense, it remained the same because the health department didn't switch to remote work; We continued to go to the office. Besides, there was no remote process; There was no online. We held meetings in person, even the COVID task force met in person. No one was working from home or doing it online." (PTE1)

"But after some time had passed at the beginning of the COVID situation, and there were directives from the health authorities, the Yogyakarta regional government began to engage in what's called risk communication. The first step, of course, was to help the public understand what COVID is, how to prevent it, and what to do if they contracted it." (P3)

"Then, there are others, like Orari and so on. So, we utilize our potential, and coordination is there. How do we coordinate all of them? We use WhatsApp groups or direct messages, and so on. So, we don't follow the conventional procedure of having meetings; It's not like that because the circumstances are different." (P5)

Dissemination of recommendations: Numerous pieces of information needed to be conveyed to the public because they required updates on the COVID-19 situation. With this demand, it was essential to provide information regarding positive recommendations on how to collectively address the COVID-19 pandemic. The following statements from participants exemplify this:

"Well, from our observations at the health department, the information that the public needs most is the development of cases. That's what the public eagerly awaits, the updates on cases, whether they're new positive cases, recoveries, or fatalities. That's the information they need." (P1)

"I believe that, normatively, several pieces of information need to be clarified, and it must be packaged as a benefit for the public, which is crucial. We shouldn't have situations where, at the beginning, people were saying, 'I'm afraid I'll get COVID if I participate in this event.' That's kind of funny, but the key is that we have to communicate that by complying with these measures, you're protecting the community." (P2)

"Yes, for those who are in isolation at home or in shelters, they need further guidance. Even those in home isolation need instructions on how not to transmit the virus. Home isolation is often not possible due to the confined living spaces and the number of occupants. In such cases, we direct them to the regional government's isolation facilities." (P3)

Theme 3: Cross-Sectoral Support According to Authority in Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic

The handling of the COVID-19 pandemic exhibited discrepancies in implementation among different agencies, especially in transportation services, despite unified guidelines. These differences posed challenges. Cross-sectoral involvement provided essential support in managing the pandemic. Various government sectors, private institutions, educational bodies, and community groups contributed according to their authority and roles. They independently engaged in promotional, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative activities.

Collaboration with Cross-Sectoral Partners. The health department involved multiple sectors, both health and non-health, in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Cooperation included voluntary community participation in addressing local issues through coordination with relevant sectors. Community organizations participated in promotional, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative efforts, such as monitoring local conditions, controlling entry points, assisting with patient transport, and distributing food. Quick and direct coordination was facilitated through various media. Educational institutions, both public and private, health and non-health agencies, religious leaders, and the military were consistent partners in providing services. Policy implementation was interconnected between central and local levels.

"We have numerous entities involved in risk communication, including social and professional entities. Collaboration spans formal bureaucracy, social, academic, and other sectors." (P1)

"Media collaboration involves cross-sectors, districts, institutions like schools, religious centers, markets, and others. For example, markets work with APPSI, religious centers with the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and schools with the Education Office." (P2)

"Experiences from places like Kulon Progo can inform provincial policies and vice versa. This interconnection influences implementation." (P5)

Authority According to Functional Roles

Each sector involved in the pandemic response operated within its defined role, executing tasks according to their job descriptions. Health promotion was conducted by the health promotion division, with task allocation based on each sector’s competencies. Most sectors provided information on their activities, monitoring results, and evaluations during the pandemic response.

"Roles within the task force were designated according to each sector’s instructions, not solely health." (P5)

"Our organization (Association of Indonesian Medical Laboratory Technologists) policy greatly assisted the health department by training members as frontline workers for sample collection and lab tests, crucial for COVID-19 testing." (P1)

" Our organization (Indonesian National Nurses Association) does not handle data processing; the health department collects data from related agencies like district health offices and health facilities." (P2)

Even Distribution of Support

Managing the pandemic required significant resources, leading to increased funding needs. Numerous organizations and institutions provided support, including sponsorships. For instance, some institutions provided operational support for vaccination, free transportation for those with limited access, and funding from educational institutions for operational costs. Support distribution was based on identified needs and mapped out accordingly.

"During significant events like a pandemic, standardized resources are essential to prevent risks. We leverage available resources from communities and technology." (P1)

"Mass vaccination events had operational costs covered by sponsors like Traveloka and Grab, including waste management and transportation for disabled individuals. Universities also provided financial support for operations." (P2)

"Community collaboration is vital for implementing health department policies." (P2)

Dilemmas and Challenges

Despite unified guidelines, differences in pandemic management still existed. Protocol discrepancies among agencies for travel control led to conflicts. Political and publicity interests sometimes resulted in information being withheld. The government faced dilemmas between adhering to regulations and meeting public needs. Challenges included uneven distribution of logistics and public reluctance to accept healthcare workers in their communities.

"Initially, COVID-19 case numbers were sensitive and kept confidential, reflecting early pandemic communication challenges." (P1)

"Obstacles included misinformation and the desire to broadcast accurate information widely." (P2)

"Discrepancies in health protocol enforcement among transportation modes (terminals, stations, airports) despite clear national task force guidelines highlighted implementation issues." (P3)

Theme 4: Central Guidelines as Decision-Making Basis for Regional Leaders

All decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic were based on central guidelines, which regional leaders adapted into local policies. In urgent situations requiring new decisions, local input was swiftly communicated to higher levels for prompt responses. Policymakers and experts acknowledged that the pandemic response was effective and swift, with monitoring, identification, information dissemination, and coordination occurring directly and responsively.

Regional Leaders as Policy Makers Based on Central Guidelines

Management of the COVID-19 pandemic, from planning to evaluation, was conducted by each region based on central decisions, albeit developed locally. Coordination within each region was centralized under a single command, led by the deputy governor or deputy regent, who acted as the task force head. When modifications in handling the pandemic were necessary, they were communicated to central authorities for approval. Once approved, these modifications became national regulations and were subsequently adapted into local policies.

"Risk communication during the pandemic benefited from a unified focus, enabling centralized management like a single command point." (P1)

"COVID-19 control at the local level is based on central policies, including Ministry of Health directives and national task force regulations, which are then adapted into regional regulations." (P3)

"Provincial guidelines form the basis for implementation at the local level, with consistent government policies across central, provincial, and local levels driving community mobilization." (P5)

Maintaining Quality Through Commitment

Policymakers and experts recognized that Indonesia’s COVID-19 response was more effective compared to other countries. Yogyakarta (DIY) received positive recognition for its pandemic management, despite occasional increases in cases due to its popularity as a tourist destination. The region’s coordination and collaboration enhanced the quality of its pandemic response. Both governmental and non-governmental sectors, including the community, demonstrated a high commitment to collaboration, contributing to the successful pandemic management in DIY.

"Despite challenges, Indonesia’s COVID-19 control was successful compared to other countries." (P3)

"DIY received praise for its COVID-19 management, though increased vigilance was required due to its status as a tourist destination." (P1)

"DIY’s health department excelled in COVID-19 control through coordination and collaboration with various sectors, including government and non-health sectors." (P2)

Rapid Response to Opportunities

Quick and direct responses were crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collection, incident analysis, emergency policy-making, and information dissemination were conducted rapidly. Policymakers and experts recognized this responsiveness as essential for effective pandemic management. Coordination and information were managed through multiple programs using various types of media.

"Risk communication design during the pandemic required speed in data collection, analysis, information dissemination, and innovation." (P1)

"Despite busy schedules, the task force's effective and timely responses were facilitated by early information gathering and coordination." (P5)

"The response was very good, with continuous coordination with INNA (Indonesian National Nurses Association) throughout the pandemic." (P2)

Theme 5: Community Leaders as Role Models Influencing Public Behavior

In managing the COVID-19 pandemic, community trust in the government is crucial. Community leaders play a vital role in fostering awareness and ensuring adherence to regulations established by central authorities. Initially, skepticism about the pandemic threat led to increased spread. Over time, prolonged pandemic conditions caused public fatigue, reducing compliance with ongoing regulations and attentiveness to government communications. In Yogyakarta (DIY), where cultural values are strong, the populace is more inclined to follow directives from Sri Sultan.

Trust and Stimuli to Remain Active

The prolonged nature of the COVID-19 pandemic led to public fatigue and diminished attention to pandemic-related information. Initial efforts to engage volunteers and donors were high due to strong awareness, but this enthusiasm waned over time. Policymakers needed to continually foster trust and raise awareness.

"The gap from not being afraid to being afraid has decreased over time due to social fatigue and reduced media focus on COVID, leading to a diversification of information sources and decreased focus on the pandemic." (P1)

"All layers of society in DIY initially had high enthusiasm due to strong awareness, but over time, interest decreased, as evidenced by the reduced engagement with shared information." (P2)

"Continuous efforts to involve the community are necessary, depending on the cutoff point, such as adherence to self-testing when symptomatic, which needs constant reinforcement." (P5)

Culturally Appropriate Role Models Have a Strong Influence

The strong cultural values in Yogyakarta (DIY) mean that directives from the Sultan are more likely to be followed than those from the central government alone. Local cultural leaders, including religious figures and community organization heads, play crucial roles in guiding the community to collectively manage the pandemic.

"The Sultan's figure is highly influential. Initially, people were reluctant to follow health protocols, but a video message from the Sultan significantly improved compliance." (P2)

"Bantul's initiative to set up shelters influenced DIY's policy for all regions to have similar facilities." (P3)

"In rural areas, the Sultan's messages in Javanese were highly effective. His charisma and cultural resonance significantly aided pandemic management efforts." (P1)

Theme 6: Need for Honest and Transparent Information Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic

Effective information management is critical in delivering important information to the public about the COVID-19 pandemic. From the pandemic's onset, people required accurate and comprehensive information about the virus and necessary measures. Transparent communication is essential to build public trust and counter misinformation. Various media platforms can be used to disseminate information widely and facilitate public inquiries.

Accurate Information to Build Trust and Avoid Hoaxes

The public needs reliable information to maintain trust and avoid misinformation. Centralized information management ensures that all disseminated information is accurate and consistent.

"Behavioral data is lacking; only clinical and laboratory data are available. Comprehensive data collection and dissemination are necessary for effective communication." (P1)

"A single point of entry for information ensures its validity, preventing misinformation. Only authorized individuals can disseminate information to avoid bias." (P2)

"Sector collaboration is evident during high case periods, with socialization efforts to enforce compliance with health protocols." (P5)

Essential Information About the COVID-19 Pandemic

The public needs detailed information about COVID-19, including its nature, transmission, management, prevention, and governmental regulations. Accessible information through various media is crucial for the public to stay informed and engage with pandemic management efforts.

"Public transparency about data is necessary. A process for disseminating essential data to the public and creating channels for questions and feedback is important." (P1)

"Key information sought by the public includes case developments, social restrictions, and vaccination details. These areas are crucial and eagerly awaited by the public." (P3)

"Expert findings on epidemiology and transmission must be communicated to the public, aiming to create awareness without causing fear, thus maintaining vigilance." (P1)

Discussion

The objective of this study is to explore the coordination and communication governance processes utilized by the Yogyakarta provincial government in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study is one of the first qualitative investigations involving various stakeholders to delineate the coordination and communication governance procedures in place during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Government policies should not be limited to partial or fragmented measures undertaken in isolation. Ideally, government policies should be comprehensive and integrated. Comprehensive policies are those that are established after a thorough examination of the root causes from their inception to the end. In this regard, it is essential to first assess the initial causes of the issue, and modes of transmission, map the affected areas and residents, and devise strategies to break the chain of transmission, leading to the discovery of a vaccine [15].

The COVID-19 pandemic, as a new outbreak with biopsychosocial and spiritual implications, requires comprehensive handling and collective responsibility to address the challenges. According to previous research, the COVID-19 pandemic is not an entirely new global experience, with occurrences spanning various timelines, ranging from hundreds of years to more recent outbreaks that happened just a few years ago. In general, the community should still remember previous similar outbreaks caused by similar viruses. However, in reality, the community was late in responding, as evidenced by the high number of casualties [16, 17].

The initial spread of the Corona Disease 2019 virus from Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 was extensive, with almost every country reporting the discovery of COVID-19, including Indonesia, which identified cases in early March 2020 [18]. Each country implemented policies based on its unique situation and conditions, resulting in strained relations between some nations. However, the most commonly employed policy was the imposition of lockdowns, believed to be the swiftest strategy for breaking the chain of COVID-19 transmission [19].

Sharing information, sharing resources, and acting together are three key activities in coordination. These three elements are of utmost importance in the coordination process to ensure that each involved party comprehends their roles, understands resource allocation, and subsequently collaborates to achieve common objectives [20]. Coordination and communication are inseparable partners, as are coordination and leadership; They mutually influence each other. In any organizational endeavor, be it small or large, coordination is invariably present because organizational goals involve interconnected components that require coordination [21].

Media plays a vital role in COVID-19 coordination, providing various accessible platforms for disseminating crucial information during the pandemic. Many scholars emphasize the significance of media in addressing the challenges of COVID-19. Mass media and mass communication are essential tools for effectively managing the COVID-19 pandemic and minimizing its global impact. They serve to inform the public about the dangers of COVID-19, how to recognize its symptoms, and the importance of adopting healthy behaviors to prevent infection [22]. Additionally, mass media facilitates the rapid, accurate, and trustworthy dissemination of statistical data, aiding the government in issuing timely warnings. However, there can be negative consequences, such as the spread of misinformation, causing fear and anxiety among the public, and fostering stigmatization of COVID-19-affected individuals [23].

Previous study suggests that many people's non-compliance with government COVID-19 policies is due to cognitive bias, leading to information misinterpretation and flawed decision-making [24]. Other research indicates that some perceive COVID-19 as being exploited for political and hospital economic gains, while others link it to job loss and economic problems. People's pandemic response involves vigilance, adherence or violation of health protocols, and denial of hospital test results. Influencing factors include figures, religious beliefs, knowledge, social habits, mask-wearing, and the sense of security from COVID-19. Modern leadership is intertwined with community presence and shaped by leaders and the local culture [25].

Indonesia, a culturally and religiously rich country, has significant potential to aid the COVID-19 pandemic response. Central Java and Bali, known for their well-preserved cultural and religious traditions, have utilized these values in pandemic response leadership. Bali's leadership draws from cultural values like Tri Hita Karana in Hinduism, while Central Java emphasizes solidarity and the Islamic concept of Hablumminannas. Both leaders employ collaborative and transformational leadership styles. In the integrated approach in Denpasar, the community-based Desa Adat task force aims to reduce and control the spread of COVID-19. Using the Desa Adat as a base allows for the involvement of all community members, not just government efforts [26].

Finally, collaboration among various stakeholders is expected to enhance the effectiveness of COVID-19 management [27]. Existing literature has demonstrated that implementing open-risk communication is challenging and involves difficulties in deciding what to communicate and what not to do. For instance, complete transparency may lead to potential fear among community members [28].

Strengths and limitations

This study offers significant strengths, primarily through its use of a qualitative research design with a phenomenological approach, enabling an in-depth understanding of stakeholder coordination and communication governance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Yogyakarta. The inclusion of diverse informants, such as government officials, healthcare professionals, and community leaders, provides a comprehensive view of the crisis management processes.

However, the study also has limitations. The relatively small sample size of twelve informants may not fully capture the diversity of experiences and perspectives across all stakeholders involved in the pandemic response. Furthermore, the study is context-specific, focusing solely on the Yogyakarta region, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or countries with different socio-political contexts and healthcare infrastructures.

Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the complexities of managing a health crisis and highlights the critical role of effective communication and coordination among stakeholders.

Conclusion

The coordination and communication governance processes utilized by the Yogyakarta provincial government in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic involves 6 main themes including training and development of human resources for the management of the crisis, the communication governance of the Yogyakarta Special Region's government, cross-sectoral support according to authority in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, central guidelines as decision-making basis for regional leaders,

community leaders as role models influencing public behavior, and need for honest and transparent information regarding the COVID -19 pandemic.