Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 119-124 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zamanlu E, Sadooghiasl A, Kazemnejad A. Effectiveness of a Designed Educational Intervention on the Rate of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnant Women; A Randomized Clinical Trial. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :119-124

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72482-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72482-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Anemia [Mesh], Anemia, Iron-Deficiency [MeSH], Iron Deficiencies [MeSH], Pregnancy [MeSH], Women [MeSH], Pregnant Women [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 692 kb]

(2703 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1856 Views)

Full-Text: (666 Views)

Introduction

Anemia is the most prevalent nutritional deficiency among pregnant women worldwide [1]. Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA) constitutes half of these anemia cases [2]. More than 80% of countries globally report a prevalence of anemia in pregnancy exceeding 20%, marking it as a significant concern during pregnancy, particularly in developing countries [4].

Anemia is a condition where the number of red blood cells and their oxygen-carrying capacity are insufficient to meet the body's physiological demands. Anemia during pregnancy is diagnosed when hemoglobin levels fall below 11 grams per deciliter in the first and third trimesters, and below 10.5g/dL in the second trimester [5]. It is categorized based on hemoglobin levels into severe (less than 7g/dL), moderate (7-10g/dL), and mild (10-11g/dL) [3].

The prevalence of IDA ranges from 3% in Europe to 50% in Africa [6], with a global prevalence during pregnancy of 41.8% [3] and 28% in Iran [2]. Anemia in pregnancy poses risks to both maternal and fetal health. While mild IDA typically does not lead to significant fetal complications, severe anemia can result in serious outcomes for both mother and fetus, including spontaneous abortion, premature birth, low birth weight, fetal death, and even an increased risk of maternal mortality [6, 7].

Oral iron supplementation is a widely used treatment for anemia in pregnant women [8]. This cost-effective and safe approach is recommended by both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) for all pregnant women. The most common side effects associated with oral iron supplements are gastrointestinal issues, which can pose challenges to patient compliance [7]. Gastrointestinal complications often lead to reduced adherence to treatment [9].

In order to increase treatment adherence and effective management of IDA in pregnancy, several interventions have been suggested. The World Health Organization has emphasized maintaining and improving the health of the people of the society and introduces it as one of the duties of governments [10]. Therefore, to provide quality services to pregnant women and prevent problems and deaths caused by problems associated with pregnancy, national guidelines based on evidence and in accordance with the latest international standards are prepared and implemented in the Department of Maternal Health of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. All centers have been notified. The National Guide for Providing Midwifery and Childbirth Services (2016) specifically deals with the issues and health and care needs of women during fertility and pregnancy [11].

Despite initiatives that began in Iran in 2015 aimed at preventing and managing IDA, research by Asghari et al. [2], Faghir-Gangi et al. [1], Khani et al. [12], and Heydarpour et al. [13] indicates that the prevalence of IDA among Iranian pregnant women varies significantly and calls for enhanced attention and revision of prevention program designs and implementations. These studies suggest that existing preventive efforts in prenatal care have not sufficiently addressed this issue. Surveys indicate that IDA prevention activities during pregnancy are currently at an average level and require more focused attention [14].

One key factor in the success of healthcare programs is client participation in health-promoting behaviors [15]. Many interventions aimed at improving health behaviors have concentrated on engaging pregnant women with anemia [5, 12, 16-20].

Additionally, the role of nurses in designing and implementing educational programs for the community is invaluable. Nurses apply current, evidence-based knowledge using valid and effective educational methods to provide care to community members [21]. This study was designed and conducted to determine the impact of a specially designed educational program on the rate of IDA in pregnant women visiting healthcare centers in West Azerbaijan.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This study was conducted in 2020 using a two-arm parallel randomized clinical trial with a control group. The protocol for this study was registered at the Iran Clinical Trial Center (IRCT20170218032635N1) and can be accessed at https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/trial/46685.

Participants

The study population included all pregnant women diagnosed with IDA who were referred to healthcare centers in Khoy.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were pregnant women between 3-6 months gestational age, diagnosed with IDA by a specialist doctor based on tests conducted at the Khoy University of Medical Sciences hospital laboratory, willingness to participate in the research, ability to communicate with researchers in Persian or Azerbaijani language, and availability to attend educational sessions.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included non-participation in the follow-up, non-attendance at training sessions, changes in the mother's physical condition that precluded her from participating in the study, and hospital admission for any reason.

The study was conducted in the city of Khoy, located in the West Azerbaijan province of Iran. Khoy is home to ten healthcare centers that provided primary care during the study period. These centers offered free prenatal care to all pregnant women. The staff included general physicians, nurses, midwives, and other healthcare workers. All pregnant women received prenatal care in accordance with the Iranian national guidelines for gynecology and obstetrics. Two midwives working at the healthcare center were responsible for providing care.

Intervention

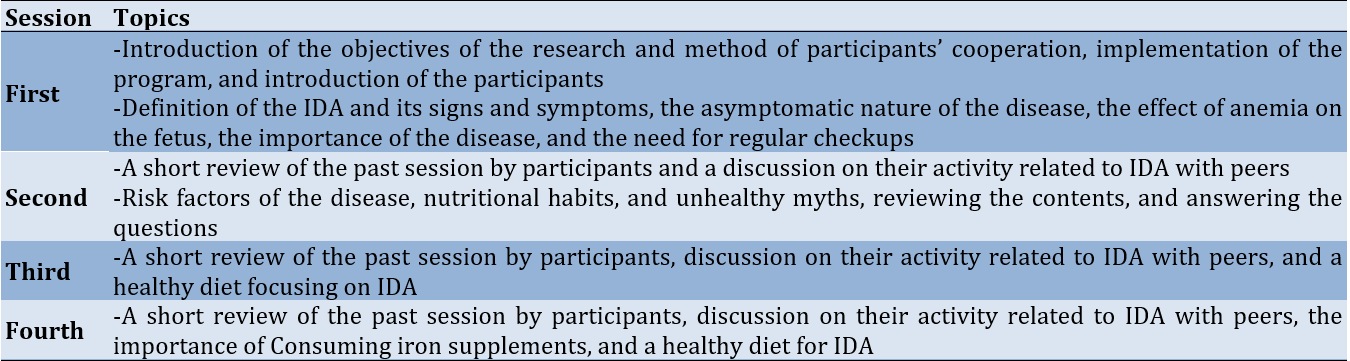

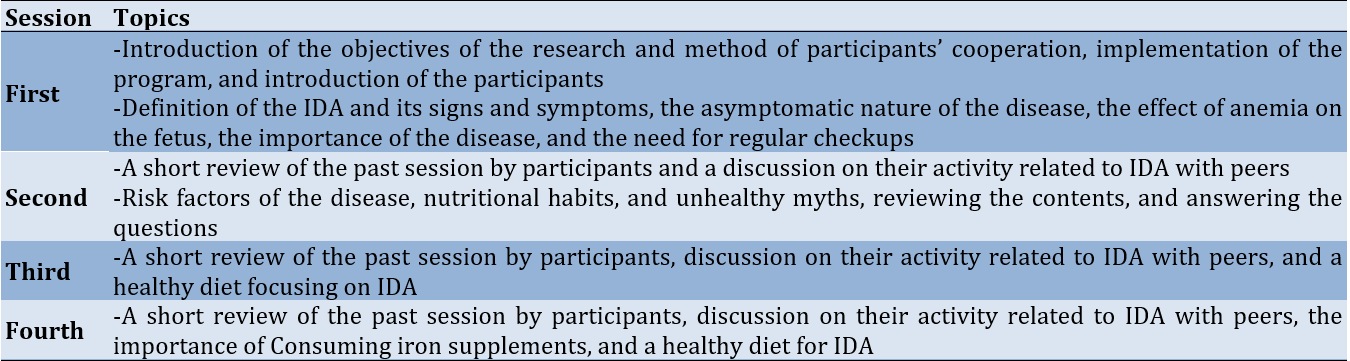

The intervention consisted of four training sessions for the intervention group, with each session lasting 45-55 minutes. The sessions were held weekly, and participants were allowed to choose their preferred day. Each session included 5-8 participants and featured lectures, group discussions, and question-and-answer segments. Educational materials used in each session included slide presentations, educational videos, pamphlets, and individual counseling. We also requested that an adult, preferably a woman, accompany each participant in the intervention group to the sessions. Additionally, we encouraged all participants to share the information and pamphlets with their families *Table 1 details the specifics of the educational sessions.

Table 1. Details of the educational intervention for the intervention group

Educational topics covered included understanding IDA in pregnancy and its effects on the mother and fetus, symptoms of IDA, prevention methods, risk factors, treatments, and the importance of testing for common anemia in pregnancy. All educational topics were presented by a community health nurse (first author).

The control group received the routine program available in the study setting. This program involved providing every pregnant woman with an oral iron supplement and individual instructions on its use, along with an educational pamphlet on IDA printed in A4 format. After the completion of the study and the collection of all data, we provided educational recorded files to the control group.

Outcome and measurements

The primary outcome of our study was the rate of IDA among participants.

To collect data, we used three following questionnaires:

1. Demographic Characteristics Form: This form gathered information on age, marital status, education level, occupational status, type of job, number of pregnancies, gestational age (in weeks) of pregnancy, past medical history, and presence of any chronic diseases.

2. IDA Report Form: This form recorded hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, using reports from laboratory tests performed at the hospital laboratory affiliated with Khoy University of Medical Sciences. All participants were referred to the same laboratory.

3. Educational Need Assessment Form: This form was used to evaluate participants’ educational needs through open-ended questions. It was completed during the first session via an interview conducted by a community health nurse (the first author). The form covered topics such as IDA and its importance during pregnancy, iron supplement consumption, and nutritional myths and unhealthy habits.

All data were collected before starting the intervention. A community health nurse (the first author) conducted interviews to complete the informed consent, demographic characteristics form, and educational need assessment form. The IDA report form was filled out using participants' prenatal care records. A post-test was conducted two months after the final intervention session. The data obtained from these forms helped to categorize the main educational topics.

Sample size

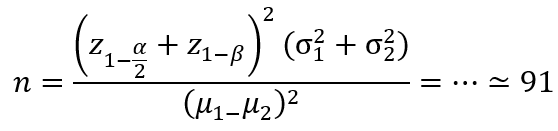

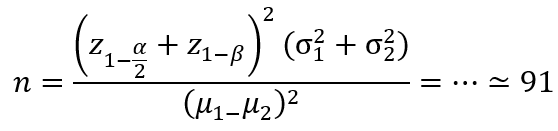

We calculated the sample size based on the results of Jalambadani et al. [22]. Considering a confidence interval of 95% and a power of 80%, the number of samples required in each group was equal to 91.

We added an additional 10% to account for the attrition rate, ultimately selecting 100 participants for each group. We employed a simple random sampling method to select participants. To avoid contamination between the intervention and control groups, we recorded the name of the midwife responsible for each selected participant. We used the quadruple block allocation method. Sampling and follow-up were conducted from November 24, 2019, to April 23, 2020.

We implemented double-blinding in the study. Participants, data analysts, and outcome assessors were blinded. All participants were informed about the aim and study methods but were unaware of their group assignment. Data analysts and outcome assessors did not know which group the participants were in.

Data analysis

We conducted data analysis in two parts: descriptive (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential (Mann-Whitney and Chi-square tests) using SPSS 16. Initially, we applied the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to evaluate the normality of the distribution of quantitative variables. Subsequently, we employed the Chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests to assess the relationships between variables. We considered a p-value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

Findings

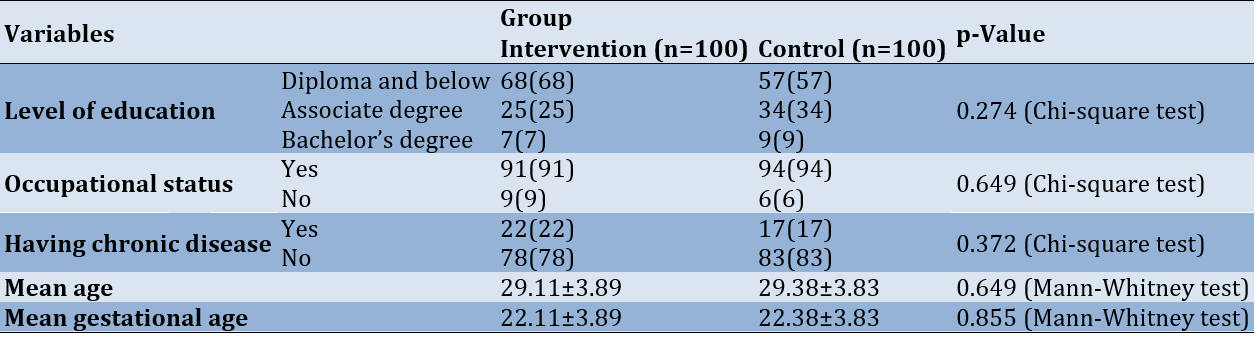

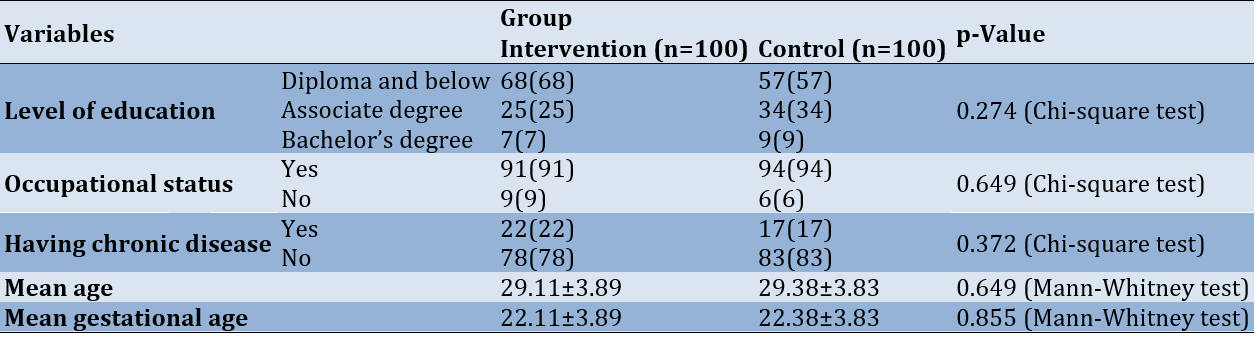

The control group had an average age of 29.38 years, 57% had a diploma or lower level of education, 94% were employed, 83% had no underlying disease, and the average gestational age was 22.38 weeks. The intervention group had an average age of 29.11 years, 68% had a diploma or lower level of education, 91% were employed, 78% had no underlying disease, and the average gestational age was 22.11 weeks.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated non-normality in age- and related data for the control (p=0.01) and the intervention (p=0.02) groups. Accordingly, the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the average ages between the intervention and control groups; the result indicated homogeneity in age across both groups (p=0.649).

Additionally, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed non-normality in gestational age for both the control and intervention groups (p<0.001). Consequently, the Mann-Whitney test (p=0.855) showed that the groups were homogeneous in terms of average gestational age. The Chi-square test indicated homogeneity in terms of education level (p=0.274), employment status (p=0.649), and underlying disease status (p=0.372), with no significant differences noted (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency and mean values of participants’ demographic characteristics in the intervention and control groups

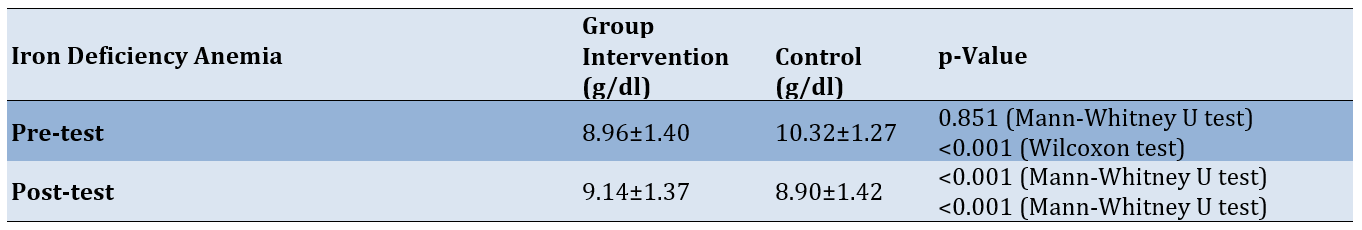

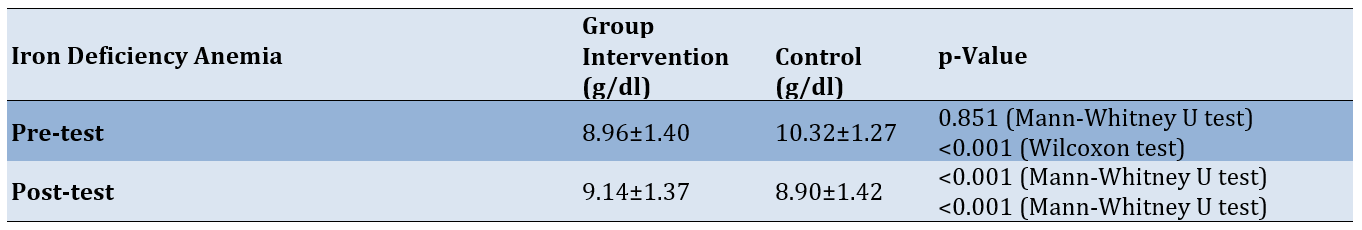

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted to evaluate the normality of the IDA variable in both the intervention and control groups, and its results led to the rejection of the normality assumption for the control group both before and after the test (p=0.006 and p=0.06, respectively). Similarly, this hypothesis was rejected in the intervention group before and after the intervention (p=0.023 and p=0.031, respectively). Initially, the Mann-Whitney U test showed no significant difference in the mean IDA scores between the control and intervention groups prior to the intervention. However, post-intervention, the Mann-Whitney U test revealed a significant difference between the mean IDA scores in the control and intervention groups (p<0.001). In the control group, the Wilcoxon test indicated a significant difference in the mean IDA score before and after the intervention. In the intervention group, based on the Mann-Whitney test results, the difference in the mean IDA score before and after the intervention was also significant (p<0.001). These results affirm the effectiveness of the designed program based on the theory of planned behavior in addressing IDA in pregnant women (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of mean iron deficiency anemia score between the two groups before and after the intervention

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which checked the normality of changes in IDA before and after the intervention, showed non-normality in the changes in IDA before and after the intervention in the intervention (p<0.001) and control (p=0.001) groups. Thus, the Mann-Whitney test was employed, revealing a statistically significant difference between the intervention (1.41±1.41 g/dl) and control groups (0.18±0.18g/dl) (p<0.001). This result demonstrates the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing IDA among pregnant women.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effect of an educational intervention on IDA in pregnant women. Data analysis indicated that the educational intervention had a statistically significant impact on reducing IDA among pregnant women, with significant changes observed in the rate of anemia in the intervention group.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies conducted in Iran. For example, the study by Jalambadani et al. [22] demonstrated that an educational intervention significantly increased participants' consumption of iron pills. Additionally, the study by Khani et al. [12] found that educational programs effectively promoted nutritional behavior for preventing anemia among pregnant women.

Studies conducted in different countries have similar findings to our results. The study by Sunuwar et al. showed that nutrition education had an effect on the hemoglobin level of pregnant women in Nepal [17]. The study by Abd Rahman et al. showed the effectiveness of a theory-based intervention program on hemoglobin level, and adherence to iron supplements, dietary iron, and dietary vitamin C intake among pregnant women with anemia [5].

These studies showed that using educational intervention helps women gain enough knowledge and awareness about the consequences of anemia during pregnancy, consider themselves at risk of contracting it, take the risk seriously, and have a high understanding of the control of anemia prevention behavior [5, 17].

In the current study, we used different methods, including giving lectures, slide presentations, educational videos, group discussions, individual counseling, and questions and answers to deliver the educational content. Chick et al. reported that using video clips to demonstrate health behaviors and in-person lectures increased the retention of educational content among patients [23].

We also asked participants to explain their understanding and share their learning with peers every session. During the content review, we ensured a clear understanding of the participants. We also asked participants to review the contents of prior sessions. Yen et al. noted that active participation during the training session and training methods increased self-management and the health outcome of a health training intervention [24]. In another study, during a teach-back method, healthcare providers asked patients to repeat in their own words regarding previous information provided during an educational or counseling session [25].

In the current study, educational intervention was prepared according to participants’ needs. According to Yen et al., focusing on individual needs while providing health information increased patients' understanding of their health needs, improved their health literacy, supported self-management, and enhanced health outcomes [24].

The research community in this research was pregnant women a vulnerable group that are an important population of any country that should be considered in terms of management and policy in development programs. Our findings revealed significant points that will help stakeholders design and deliver substantive solutions. Paying attention to the role of nurses especially, the community health nurses in designing and implementing health promotion and preventive programs, the theory of planned behavior was used in designing educational programs among pregnant women.

According to the findings, the prevalence of IDA in pregnant women in the research community was significant, and the implementation of the national pregnancy care program and the referral of pregnant women to medical centers and receiving midwifery care still require more attention and focus.

Our findings could be used in different areas of the nursing profession. Nurses are in contact with the individual, family, and society in different fields, and by designing and implementing educational programs in different groups, they can increase health and disease prevention. Our designed program can be used by nurses for other patients. Also, the educational content of this program, with a slight improvement, can be used for patients suffering from IDA. Also, with the implementation of the training program by nurses, the professional position of nurses among the people of the society is recognized and their role in promoting the health of the society is more considered. In this study, the theory of planned behavior was used; however, nurses can design other programs using it as an operating model. This study was conducted in several health centers in Khoy city; therefore, regarding the generalizability of the results, it is necessary to pay attention to the characteristics of the society and the research environment.

Conclusion

The designed educational intervention is effective in reducing IDA among pregnant women.

Acknowledgments: This study is the result of the thesis of the first author in the master's degree in community health nursing, which was approved by Tarbiat Modares University. We hereby express our thanks and appreciation to the honorable research assistant of that university. Also, the authors express their gratitude to the Khoi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services for the implementation of this study, as well as all the pregnant women participating in this study.

Ethical Permission: Ethical considerations in this study included obtaining ethics approval (IR.MODARES.REC.1398.031) from the Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, obtaining permission to enter the research environment, obtaining written informed consent from the participants, and maintaining anonymity and confidentiality. The participants were allowed to leave the study freely at any stage, and the training program was presented to the control group at the end of the study. We also registered the protocol of this study at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20170218032635N1).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Zamanlu E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Sadooghiasl A (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Kazemnejad A (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Tarbiat Modares University.

Anemia is the most prevalent nutritional deficiency among pregnant women worldwide [1]. Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA) constitutes half of these anemia cases [2]. More than 80% of countries globally report a prevalence of anemia in pregnancy exceeding 20%, marking it as a significant concern during pregnancy, particularly in developing countries [4].

Anemia is a condition where the number of red blood cells and their oxygen-carrying capacity are insufficient to meet the body's physiological demands. Anemia during pregnancy is diagnosed when hemoglobin levels fall below 11 grams per deciliter in the first and third trimesters, and below 10.5g/dL in the second trimester [5]. It is categorized based on hemoglobin levels into severe (less than 7g/dL), moderate (7-10g/dL), and mild (10-11g/dL) [3].

The prevalence of IDA ranges from 3% in Europe to 50% in Africa [6], with a global prevalence during pregnancy of 41.8% [3] and 28% in Iran [2]. Anemia in pregnancy poses risks to both maternal and fetal health. While mild IDA typically does not lead to significant fetal complications, severe anemia can result in serious outcomes for both mother and fetus, including spontaneous abortion, premature birth, low birth weight, fetal death, and even an increased risk of maternal mortality [6, 7].

Oral iron supplementation is a widely used treatment for anemia in pregnant women [8]. This cost-effective and safe approach is recommended by both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) for all pregnant women. The most common side effects associated with oral iron supplements are gastrointestinal issues, which can pose challenges to patient compliance [7]. Gastrointestinal complications often lead to reduced adherence to treatment [9].

In order to increase treatment adherence and effective management of IDA in pregnancy, several interventions have been suggested. The World Health Organization has emphasized maintaining and improving the health of the people of the society and introduces it as one of the duties of governments [10]. Therefore, to provide quality services to pregnant women and prevent problems and deaths caused by problems associated with pregnancy, national guidelines based on evidence and in accordance with the latest international standards are prepared and implemented in the Department of Maternal Health of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. All centers have been notified. The National Guide for Providing Midwifery and Childbirth Services (2016) specifically deals with the issues and health and care needs of women during fertility and pregnancy [11].

Despite initiatives that began in Iran in 2015 aimed at preventing and managing IDA, research by Asghari et al. [2], Faghir-Gangi et al. [1], Khani et al. [12], and Heydarpour et al. [13] indicates that the prevalence of IDA among Iranian pregnant women varies significantly and calls for enhanced attention and revision of prevention program designs and implementations. These studies suggest that existing preventive efforts in prenatal care have not sufficiently addressed this issue. Surveys indicate that IDA prevention activities during pregnancy are currently at an average level and require more focused attention [14].

One key factor in the success of healthcare programs is client participation in health-promoting behaviors [15]. Many interventions aimed at improving health behaviors have concentrated on engaging pregnant women with anemia [5, 12, 16-20].

Additionally, the role of nurses in designing and implementing educational programs for the community is invaluable. Nurses apply current, evidence-based knowledge using valid and effective educational methods to provide care to community members [21]. This study was designed and conducted to determine the impact of a specially designed educational program on the rate of IDA in pregnant women visiting healthcare centers in West Azerbaijan.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This study was conducted in 2020 using a two-arm parallel randomized clinical trial with a control group. The protocol for this study was registered at the Iran Clinical Trial Center (IRCT20170218032635N1) and can be accessed at https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/trial/46685.

Participants

The study population included all pregnant women diagnosed with IDA who were referred to healthcare centers in Khoy.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were pregnant women between 3-6 months gestational age, diagnosed with IDA by a specialist doctor based on tests conducted at the Khoy University of Medical Sciences hospital laboratory, willingness to participate in the research, ability to communicate with researchers in Persian or Azerbaijani language, and availability to attend educational sessions.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included non-participation in the follow-up, non-attendance at training sessions, changes in the mother's physical condition that precluded her from participating in the study, and hospital admission for any reason.

The study was conducted in the city of Khoy, located in the West Azerbaijan province of Iran. Khoy is home to ten healthcare centers that provided primary care during the study period. These centers offered free prenatal care to all pregnant women. The staff included general physicians, nurses, midwives, and other healthcare workers. All pregnant women received prenatal care in accordance with the Iranian national guidelines for gynecology and obstetrics. Two midwives working at the healthcare center were responsible for providing care.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of four training sessions for the intervention group, with each session lasting 45-55 minutes. The sessions were held weekly, and participants were allowed to choose their preferred day. Each session included 5-8 participants and featured lectures, group discussions, and question-and-answer segments. Educational materials used in each session included slide presentations, educational videos, pamphlets, and individual counseling. We also requested that an adult, preferably a woman, accompany each participant in the intervention group to the sessions. Additionally, we encouraged all participants to share the information and pamphlets with their families *Table 1 details the specifics of the educational sessions.

Table 1. Details of the educational intervention for the intervention group

Educational topics covered included understanding IDA in pregnancy and its effects on the mother and fetus, symptoms of IDA, prevention methods, risk factors, treatments, and the importance of testing for common anemia in pregnancy. All educational topics were presented by a community health nurse (first author).

The control group received the routine program available in the study setting. This program involved providing every pregnant woman with an oral iron supplement and individual instructions on its use, along with an educational pamphlet on IDA printed in A4 format. After the completion of the study and the collection of all data, we provided educational recorded files to the control group.

Outcome and measurements

The primary outcome of our study was the rate of IDA among participants.

To collect data, we used three following questionnaires:

1. Demographic Characteristics Form: This form gathered information on age, marital status, education level, occupational status, type of job, number of pregnancies, gestational age (in weeks) of pregnancy, past medical history, and presence of any chronic diseases.

2. IDA Report Form: This form recorded hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, using reports from laboratory tests performed at the hospital laboratory affiliated with Khoy University of Medical Sciences. All participants were referred to the same laboratory.

3. Educational Need Assessment Form: This form was used to evaluate participants’ educational needs through open-ended questions. It was completed during the first session via an interview conducted by a community health nurse (the first author). The form covered topics such as IDA and its importance during pregnancy, iron supplement consumption, and nutritional myths and unhealthy habits.

All data were collected before starting the intervention. A community health nurse (the first author) conducted interviews to complete the informed consent, demographic characteristics form, and educational need assessment form. The IDA report form was filled out using participants' prenatal care records. A post-test was conducted two months after the final intervention session. The data obtained from these forms helped to categorize the main educational topics.

Sample size

We calculated the sample size based on the results of Jalambadani et al. [22]. Considering a confidence interval of 95% and a power of 80%, the number of samples required in each group was equal to 91.

We added an additional 10% to account for the attrition rate, ultimately selecting 100 participants for each group. We employed a simple random sampling method to select participants. To avoid contamination between the intervention and control groups, we recorded the name of the midwife responsible for each selected participant. We used the quadruple block allocation method. Sampling and follow-up were conducted from November 24, 2019, to April 23, 2020.

We implemented double-blinding in the study. Participants, data analysts, and outcome assessors were blinded. All participants were informed about the aim and study methods but were unaware of their group assignment. Data analysts and outcome assessors did not know which group the participants were in.

Data analysis

We conducted data analysis in two parts: descriptive (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential (Mann-Whitney and Chi-square tests) using SPSS 16. Initially, we applied the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to evaluate the normality of the distribution of quantitative variables. Subsequently, we employed the Chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests to assess the relationships between variables. We considered a p-value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

Findings

The control group had an average age of 29.38 years, 57% had a diploma or lower level of education, 94% were employed, 83% had no underlying disease, and the average gestational age was 22.38 weeks. The intervention group had an average age of 29.11 years, 68% had a diploma or lower level of education, 91% were employed, 78% had no underlying disease, and the average gestational age was 22.11 weeks.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated non-normality in age- and related data for the control (p=0.01) and the intervention (p=0.02) groups. Accordingly, the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the average ages between the intervention and control groups; the result indicated homogeneity in age across both groups (p=0.649).

Additionally, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed non-normality in gestational age for both the control and intervention groups (p<0.001). Consequently, the Mann-Whitney test (p=0.855) showed that the groups were homogeneous in terms of average gestational age. The Chi-square test indicated homogeneity in terms of education level (p=0.274), employment status (p=0.649), and underlying disease status (p=0.372), with no significant differences noted (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency and mean values of participants’ demographic characteristics in the intervention and control groups

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted to evaluate the normality of the IDA variable in both the intervention and control groups, and its results led to the rejection of the normality assumption for the control group both before and after the test (p=0.006 and p=0.06, respectively). Similarly, this hypothesis was rejected in the intervention group before and after the intervention (p=0.023 and p=0.031, respectively). Initially, the Mann-Whitney U test showed no significant difference in the mean IDA scores between the control and intervention groups prior to the intervention. However, post-intervention, the Mann-Whitney U test revealed a significant difference between the mean IDA scores in the control and intervention groups (p<0.001). In the control group, the Wilcoxon test indicated a significant difference in the mean IDA score before and after the intervention. In the intervention group, based on the Mann-Whitney test results, the difference in the mean IDA score before and after the intervention was also significant (p<0.001). These results affirm the effectiveness of the designed program based on the theory of planned behavior in addressing IDA in pregnant women (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of mean iron deficiency anemia score between the two groups before and after the intervention

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which checked the normality of changes in IDA before and after the intervention, showed non-normality in the changes in IDA before and after the intervention in the intervention (p<0.001) and control (p=0.001) groups. Thus, the Mann-Whitney test was employed, revealing a statistically significant difference between the intervention (1.41±1.41 g/dl) and control groups (0.18±0.18g/dl) (p<0.001). This result demonstrates the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing IDA among pregnant women.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effect of an educational intervention on IDA in pregnant women. Data analysis indicated that the educational intervention had a statistically significant impact on reducing IDA among pregnant women, with significant changes observed in the rate of anemia in the intervention group.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies conducted in Iran. For example, the study by Jalambadani et al. [22] demonstrated that an educational intervention significantly increased participants' consumption of iron pills. Additionally, the study by Khani et al. [12] found that educational programs effectively promoted nutritional behavior for preventing anemia among pregnant women.

Studies conducted in different countries have similar findings to our results. The study by Sunuwar et al. showed that nutrition education had an effect on the hemoglobin level of pregnant women in Nepal [17]. The study by Abd Rahman et al. showed the effectiveness of a theory-based intervention program on hemoglobin level, and adherence to iron supplements, dietary iron, and dietary vitamin C intake among pregnant women with anemia [5].

These studies showed that using educational intervention helps women gain enough knowledge and awareness about the consequences of anemia during pregnancy, consider themselves at risk of contracting it, take the risk seriously, and have a high understanding of the control of anemia prevention behavior [5, 17].

In the current study, we used different methods, including giving lectures, slide presentations, educational videos, group discussions, individual counseling, and questions and answers to deliver the educational content. Chick et al. reported that using video clips to demonstrate health behaviors and in-person lectures increased the retention of educational content among patients [23].

We also asked participants to explain their understanding and share their learning with peers every session. During the content review, we ensured a clear understanding of the participants. We also asked participants to review the contents of prior sessions. Yen et al. noted that active participation during the training session and training methods increased self-management and the health outcome of a health training intervention [24]. In another study, during a teach-back method, healthcare providers asked patients to repeat in their own words regarding previous information provided during an educational or counseling session [25].

In the current study, educational intervention was prepared according to participants’ needs. According to Yen et al., focusing on individual needs while providing health information increased patients' understanding of their health needs, improved their health literacy, supported self-management, and enhanced health outcomes [24].

The research community in this research was pregnant women a vulnerable group that are an important population of any country that should be considered in terms of management and policy in development programs. Our findings revealed significant points that will help stakeholders design and deliver substantive solutions. Paying attention to the role of nurses especially, the community health nurses in designing and implementing health promotion and preventive programs, the theory of planned behavior was used in designing educational programs among pregnant women.

According to the findings, the prevalence of IDA in pregnant women in the research community was significant, and the implementation of the national pregnancy care program and the referral of pregnant women to medical centers and receiving midwifery care still require more attention and focus.

Our findings could be used in different areas of the nursing profession. Nurses are in contact with the individual, family, and society in different fields, and by designing and implementing educational programs in different groups, they can increase health and disease prevention. Our designed program can be used by nurses for other patients. Also, the educational content of this program, with a slight improvement, can be used for patients suffering from IDA. Also, with the implementation of the training program by nurses, the professional position of nurses among the people of the society is recognized and their role in promoting the health of the society is more considered. In this study, the theory of planned behavior was used; however, nurses can design other programs using it as an operating model. This study was conducted in several health centers in Khoy city; therefore, regarding the generalizability of the results, it is necessary to pay attention to the characteristics of the society and the research environment.

Conclusion

The designed educational intervention is effective in reducing IDA among pregnant women.

Acknowledgments: This study is the result of the thesis of the first author in the master's degree in community health nursing, which was approved by Tarbiat Modares University. We hereby express our thanks and appreciation to the honorable research assistant of that university. Also, the authors express their gratitude to the Khoi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services for the implementation of this study, as well as all the pregnant women participating in this study.

Ethical Permission: Ethical considerations in this study included obtaining ethics approval (IR.MODARES.REC.1398.031) from the Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, obtaining permission to enter the research environment, obtaining written informed consent from the participants, and maintaining anonymity and confidentiality. The participants were allowed to leave the study freely at any stage, and the training program was presented to the control group at the end of the study. We also registered the protocol of this study at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20170218032635N1).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Zamanlu E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Sadooghiasl A (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Kazemnejad A (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Tarbiat Modares University.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2023/12/17 | Accepted: 2024/04/5 | Published: 2024/04/15

Received: 2023/12/17 | Accepted: 2024/04/5 | Published: 2024/04/15

References

1. Faghir-Gangi M, Amanollahi A, Nikbina M, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Abdolmohamadi N. Prevalence and risk factors of anemia in first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e14197. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14197]

2. Asghari S, Mohammadzadegan-Tabrizi R, Rafraf M, Sarbakhsh P, Babaie J. Prevalence and predictors of iron-deficiency anemia: Women's health perspective at reproductive age in the suburb of dried Urmia Lake, Northwest of Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:332. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_166_20]

3. Garzon S, Cacciato PM, Certelli C, Salvaggio C, Magliarditi M, Rizzo G. Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy: Novel approaches for an old problem. Oman Med J. 2020;35(5):e166. [Link] [DOI:10.5001/omj.2020.108]

4. Tang G, Lausman A, Abdulrehman J, Petrucci J, Nisenbaum R, Hicks LK, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy: A single centre Canadian study. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):3389. [Link] [DOI:10.1182/blood-2019-127602]

5. Abd Rahman R, Idris IB, Md Isa Z, Abd Rahman R. The effectiveness of a theory-based intervention program for pregnant women with anemia: A randomized control trial. PloS one. 2022;17(12):e0278192. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0278192]

6. Tan J, He G, Qi Y, Yang H, Xiong Y, Liu C, et al. Prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency anemia in Chinese pregnant women (IRON WOMEN): A national cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:670. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-03359-z]

7. Benson AE, Shatzel JJ, Ryan KS, Hedges MA, Martens K, Aslan JE, et al. The incidence, complications, and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy. Eur J Haematol. 2022;109(6):633-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/ejh.13870]

8. Igbinosa I, Berube C, Lyell DJ. Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34(2):69-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000772]

9. Mintsopoulos V, Tannenbaum E, Malinowski AK, Shehata N, Walker M. Identification and treatment of iron‐deficiency anemia in pregnancy and postpartum: A systematic review and quality appraisal of guidelines using AGREE II. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2024;164(2):460-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ijgo.14978]

10. Sadooghiasl A, Ghalenow HR, Mahinfar K, Hashemi SS. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction program in improving mental well-being of patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26(4):439-45. [Link] [DOI:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24164]

11. National guide to providing midwifery and childbirth services (3d Revision). Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education punlishing; 2018. [Link]

12. Khani Jeihooni A, Rakhshani T, Harsini PA, Layeghiasl M. Effect of educational program based on theory of planned behavior on promoting nutritional behaviors preventing Anemia in a sample of Iranian pregnant women. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:2198. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-12270-x]

13. Heydarpour F, Soltani M, Najafi F, Tabatabaee HR, Etemad K, Hajipour M, et al. Maternal anemia in various trimesters and related pregnancy outcomes: Results from a large cohort study in Iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2019;29(1):e69741. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijp.69741]

14. Ghaffari Sardasht F, Motaghi Z, Shariati M, Keramat A, Akbari N. The status, policies, and programs of preconception risk assessment in Iran: A narrative review. J Caring Sci. 2022;11(2):105-17. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/jcs.2022.15]

15. Dahmardeh H, Sadooghiasl A, Mohammadi E, Kazemnejad A. The experiences of patients with multiple sclerosis of self-compassion: A qualitative content analysis. BioMedicine. 2021;11(4):35-42. [Link] [DOI:10.37796/2211-8039.1211]

16. Abujilban S, Hatamleh R, Al-Shuqerat S. The impact of a planned health educational program on the compliance and knowledge of Jordanian pregnant women with anemia. Women Health. 2019;59(7):748-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03630242.2018.1549644]

17. Sunuwar DR, Sangroula RK, Shakya NS, Yadav R, Chaudhary NK, Pradhan PMS. Effect of nutrition education on hemoglobin level in pregnant women: A quasi-experimental study. PloS One. 2019;14(3):e0213982. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0213982]

18. Nahrisah P, Somrongthong R, Viriyautsahakul N, Viwattanakulvanid P, Plianbangchang S. Effect of integrated pictorial handbook education and counseling on improving anemia status, knowledge, food intake, and iron tablet compliance among anemic pregnant women in Indonesia: A quasi-experimental study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:43-52. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S213550]

19. Meiranny A, Arisanti AZ, Rahmawati PN. Literature review: The influence of educational media on pregnant mothers' knowledge about anemia. Faletehan Health J. 2023;10(2):222-30. [Indonesian] [Link]

20. Salam SS, Ramadurg U, Charantimath U, Katageri G, Gillespie B, Mhetri J, et al. Impact of a school‐based nutrition educational intervention on knowledge related to iron deficiency anaemia in rural Karnataka, India: A mixed methods pre-post interventional study. BJOG. 2023;130(S3):113-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.17619]

21. Salisu WJ, Sadooghiasl A, Yakubu I, Abdul-Rashid H, Mohammed S. The experiences of nurses and midwives regarding nursing education in Ghana: A qualitative content analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;92:104507. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104507]

22. Jalambadani Z, Shojaei Zadeh D, Hoseini M, Sadeghi R. The effect of education for iron consumption based on the theory of planned behavior in pregnant women in Mashhad. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2015;4(2):59-68. [Link]

23. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, Propper BW, Hale DF, Alseidi AA, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018]

24. Yen PH, Leasure AR. Use and effectiveness of the teach-back method in patient education and health outcomes. Fed Pract. 2019;36(6):284-9. [Link]

25. Shersher V, Haines TP, Sturgiss L, Weller C, Williams C. Definitions and use of the teach-back method in healthcare consultations with patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(1):118-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2020.07.026]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |