Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 43-46 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kusumawati P, Samdin S, Takdir D, Tosepu R, Saimin J, Zaid S et al . Role of Affective Commitment as a Mediator in the Relationship between the Infection Prevention and Control Committee Members’ Performance and Work Competency and Compensation. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :43-46

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72168-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72168-en.html

1- Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Halu Oleo University, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

2- Department of Public Health, Faculty of Public Health, Halu Oleo University, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

3- Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Halu Oleo University, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

2- Department of Public Health, Faculty of Public Health, Halu Oleo University, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

3- Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Halu Oleo University, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

Keywords: Work Performance [Mesh], Mental Competency [MeSH], Compensation and Redress [MeSH], Work [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 739 kb]

(3450 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1403 Views)

Full-Text: (298 Views)

Introduction

In recent times, there has been a global focus on the quality of health services, driven by increasing demands from all sectors of society [1, 2]. In response to this demand, numerous countries have initiated the development of various indicators to assess the quality of health services, with accreditation being one such important measure [3, 4]. A primary objective of hospital accreditation is the reduction of infection risks. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) refer to infections that occur in patients during their treatment in hospitals or other healthcare facilities, and which were either not present or dormant at the time of admission [5]. This definition also encompasses infections acquired in the hospital but only manifesting after the patient's discharge. It is worth noting that IPC can affect not only patients but also healthcare workers and hospital staff. According to a survey conducted in the United States, HAIs reached a staggering 722,000 cases in acute care units, resulting in 75,000 patient deaths in 2016 [3]. HAIs are also a concern in Indonesia, where several studies have documented their prevalence [6].

Infection prevention and control (IPC) should not be perceived as an isolated professional component but rather as a set of principles that, when implemented effectively, can reduce the risk of patients or individuals contracting infections [7]. To enhance service quality, the establishment of a patient safety (patient and public involvement (PPI)) committee within hospitals is imperative [8]. In Southeast Sulawesi, healthcare facilities under the Southeast Sulawesi Provincial Health Service have established IPC committees. These committees comprise various healthcare professionals, including IPC doctors, IPC nurses, general practitioners, specialist doctors, dentists, ward nurses, and other healthcare workers. As of March 31, 2023, the Southeast Sulawesi IPC Committee consisted of 447 members. However, there is room for improvement in the performance of the Southeast Sulawesi PPI committee, as evidenced by the prevalence of infections (HAIs) in Southeast Sulawesi District Hospitals exceeding the national average (more than 1%).

Employee performance, particularly within the IPC committee, is influenced by various factors, with work competency being a significant one [7, 9]. Employees who possess strong competencies consistently exhibit intelligent thinking, reliability, experience, skills, and professionalism, resulting in optimal work outcomes in terms of quantity, quality, time efficiency, and budgetary effectiveness within the organization [10, 11]. Martini et al. [12] have shown a direct correlation between work competency and employee performance; higher competence in a job typically leads to enhanced performance. In contrast, Efendi & Yusuf [13] did not identify a significant impact of work competency on employee performance. In our study, we have refined the measure of work competency by categorizing skills into two distinct areas: soft skills and hard skills. This categorization is particularly relevant because PPI committee members are healthcare professionals who employ numerous technical skills in their roles yet are required to master several soft skills when joining the committee.

Compensation is another pivotal factor that can influence employee performance. Employee dissatisfaction often arises from inadequate remuneration, whether in the form of monetary rewards or facilities provided as recognition for their work [14]. Employees engage in work with the expectation that their livelihood needs will be fulfilled, and organizations are expected to compensate employees commensurately for their contributions. Ekhsan and Septian [15] found that favorable compensation positively impacts employee performance, while Astuti [16] has demonstrated that fair and adequate compensation can enhance employee performance within the healthcare sector. Indeed, there exists a positive correlation between good compensation and employee performance, although some research suggests no direct influence of compensation on employee performance, as evidenced by Idris et al. [17] in the study conducted on the three main campuses in Indonesia.

In addition to work competency and compensation, a staff's dedication to the organization can significantly impact their performance. As per Robbins [18], there are three types of work commitment: affective commitment, norm-based commitment, and continuance commitment. Among these, affective commitment holds particular importance as it encapsulates the core essence of commitment—the emotional bond between employees and their organization—and forms the most steadfast connection within its conceptual framework [19].

Our study departs from previous research by evaluating the performance of IPC committee members and includes affective commitment as a mediating variable between work competency and compensation. This innovative approach adds novelty to our research in comparison to prior studies. The present study seeks to explore and evaluate how the capabilities and incentives of committee members influence their performance, with emotional commitment serving as a linking factor.

Instrument and Methods

Study Design

This explanatory research aimed to provide explanations for causal relationships between variables.

Participants

The research was conducted at the regional general hospital (RSUD), under the auspices of the Southeast Sulawesi Provincial Health Service, from April to September 2023. The study's population consisted of Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Committee members (n=447) working in 17 regional hospitals throughout Southeast Sulawesi.

Sample Size

The sample size was 447 individuals determined by cluster random sampling using the Slovin formula considering a 5% margin of error.

Research Tools and Data Collection

For data collection, a questionnaire-based survey was chosen as the primary instrument. The advantage of using questionnaire surveys is their ability to accommodate large sample sizes without being constrained by geographical boundaries. The data collection process utilized closed-ended questions, with predetermined response options for the respondents to select from. The researchers adapted instruments from previous studies to measure various variables. Competency was evaluated using knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA)-based competency indicators developed by Huang et al. [20] and Zhang [21]. Compensation was assessed using indicators formulated by Teclemichael Tessema and Soeters [22], whereas affective commitment was measured with indicators devised by Meyer et al. [23]. Employee performance was assessed using task performance indicators developed by Koopmans et al. [24]. The survey utilized a five-point Likert scale, allowing participants to assign ratings to each statement as follows: 1 for strongly disagree, 2 for disagree, 3 for neutral, 4 for agree, and 5 for strongly agree.

A series of tests were conducted to evaluate the reliability and validity of the indicators used in this study. These evaluations included assessing outer loading and convergent validity (average variance extracted, AVE) for validity, alongside composite reliability and Cronbach's alpha for reliability. The outcomes of these tests confirmed that the indicators were both reliable and valid, thus supporting the model used. In particular, the indicators showed an outer loading value greater than 0.50, a composite reliability exceeding 0.70, and an AVE value above 0.5, all of which signify strong validity and reliability. Each indicator achieved outer loading and AVE values above 0.5, and composite reliability and Cronbach's Alpha values higher than 0.60.

Ethics

The ethics committee of the Indonesian Association of Public Health Experts, Southeast Sulawesi Province approved this study (80/KEPK-IAKMI/VI.2023).

Statistical Tests

After collecting the data and conducting validity and reliability tests, the data was analyzed by SPSS 24. The analysis was carried out using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method, which involved three stages of evaluation: the measurement model assessment, the structural model assessment, and the hypothesis testing phase.

Findings

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. The frequency of respondents’ demographic characteristics

The participants in this study were health workers who were members of the IPC Committee, with the majority being room nurses and other health workers, comprising 65 (30.66%) and 94 (44.34%) individuals, respectively.

The study applied R-square (R2), Q-square (Q2), and goodness of fit (GoF) measures to assess the model's fit. Based on the evaluation of the model's appropriateness criteria, all indicators suggested that the research model was highly accurate. The results of the model fit test indicated that the affective commitment variable had an R2 of 0.643 and a Q2 of 0.466. The employee performance showed an R2 of 0.755 and a Q2 of 0.553. Furthermore, the GoF demonstrated a value of 0.683.

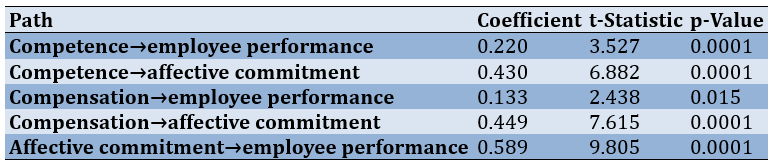

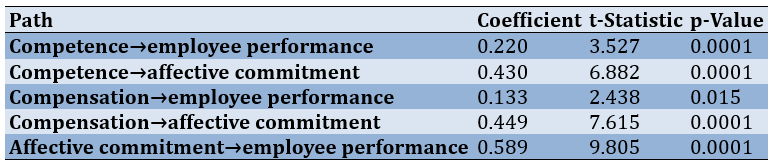

There was a significant positive relationship between competence and employee performance (R2: 0.220; p-value=0.0001). Similarly, a significant positive effect of competence on emotional commitment was observed (R2: 0.430; p-value=0.0001). Compensation had a significant positive effect on the performance of committee members (R2=0.133; p-value=0.015). Likewise, a strong significant effect of compensation on emotional commitment was found (R2=0.449; p-value=0.000). Additionally, affective commitment had a strong significant effect on the performance of committee members (R2=0.589; p-value=0.000) (Table 2).

Table 2. Direct effect analysis

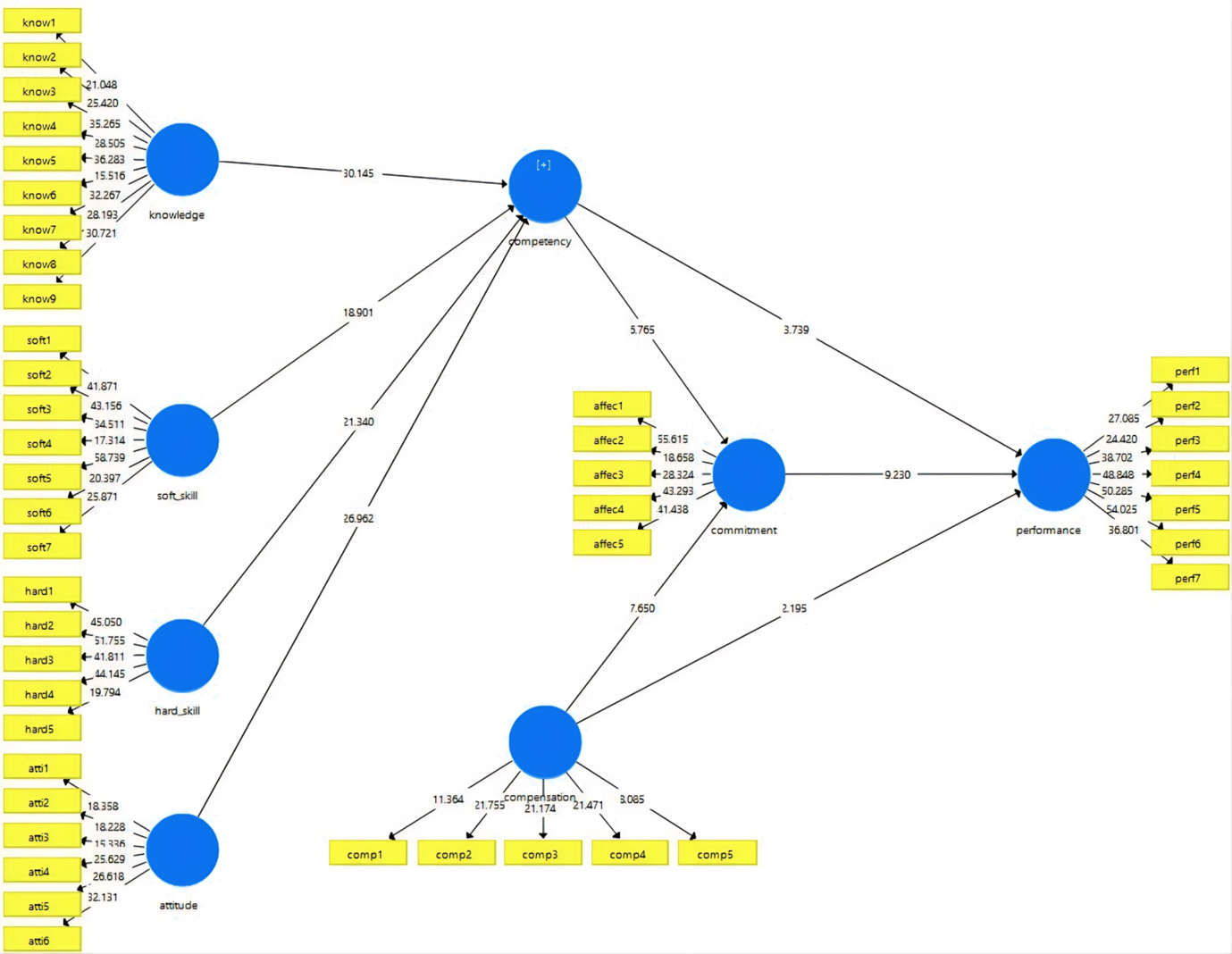

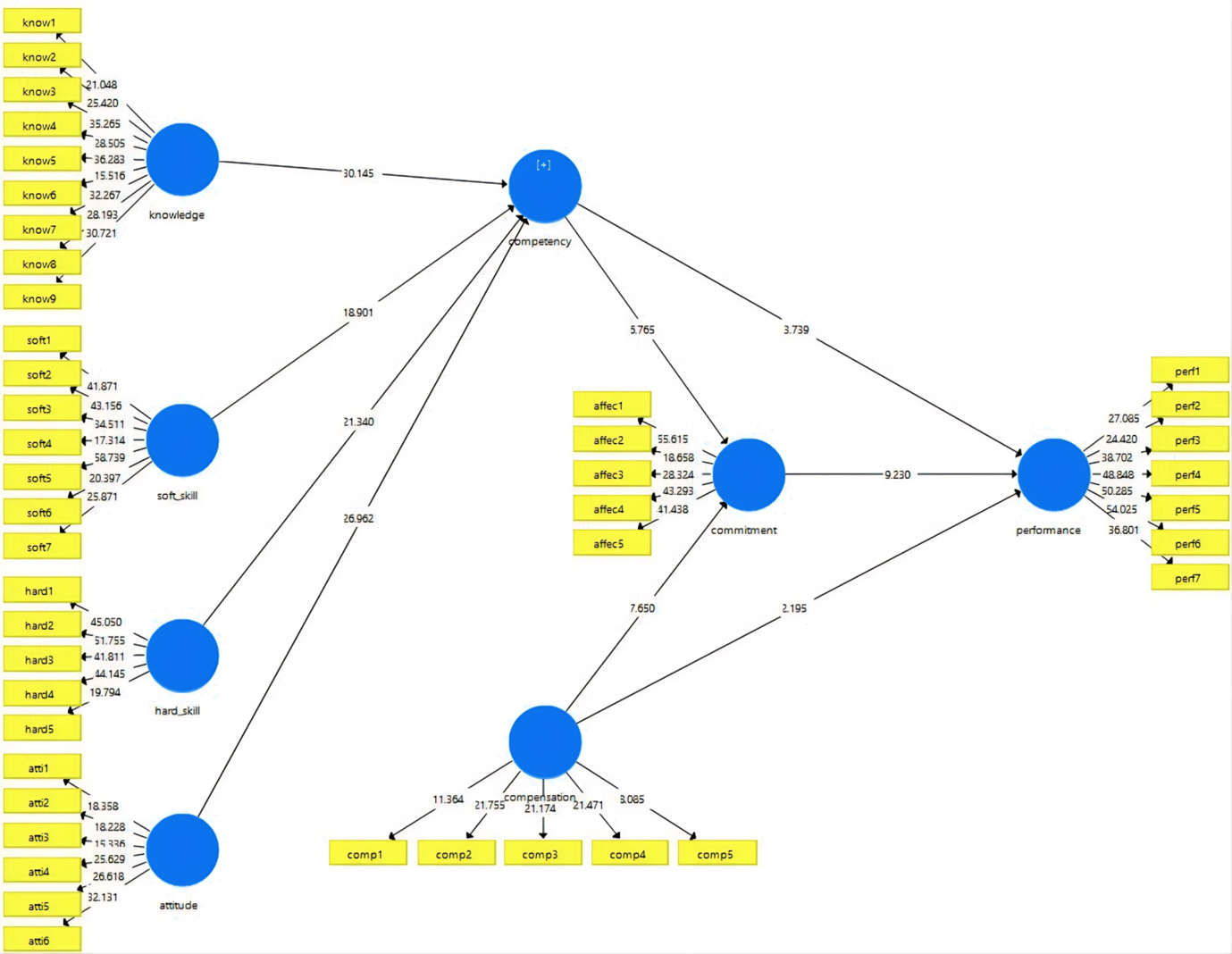

Figure 1 shows the results of the hypothesis analysis.

Figure 1. Hypothesis analysis results.

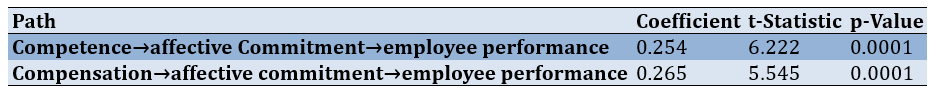

The results presented in Table 3 illustrate the role of affective commitment as a mediator in the relationship between competence and the performance of committee members (r=0.254; p<0.0001). Statistically, there was a significant increase in the path value from 0.220, which indicates the direct effect of competence on committee members' performance, to 0.254, representing the indirect impact of competence on performance through affective commitment. This indicates that affective commitment enhances the link between competence and employee performance. Also, affective commitment played a mediating role in the relationship between compensation and employee performance (r=0.265, p-value=0.0001). Compensation had a significant effect on affective commitment and employee performance, suggesting that affective commitment acted as a partial mediator.

Table 3. Indirect effect analysis

Discussion

The findings of the current study validate the proposed model and notably emphasize the mediating role of emotional commitment in its relationship with employee competence, compensation, and performance. Moreover, the study discovered that proficiencies, including knowledge, soft skills, hard skills, and attitudes, significantly and positively affect the emotional commitment and performance of committee members of the Southeast Sulawesi IPC. The results strongly indicate that substantial improvements in knowledge, soft skills, hard skills, and attitudes enhance emotional commitment and employee performance. The analysis showed that the contribution of knowledge surpasses that of other competency elements, suggesting that enhancing knowledge would have a more significant impact compared to other competency elements. Therefore, to improve commitment and performance, IPC committee members in Southeast Sulawesi should give priority to increasing knowledge, followed by improving other competency elements. It is also important to acknowledge that other competency elements, such as soft skills, hard skills, and attitudes, significantly impact the performance of committee members.

Knowledge is identified as the primary individual factor. This aligns with research conducted in Intensive Care Units (ICU), which demonstrates a significant correlation between knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, and nurses' occupational health and safety measures in infection control. Adequate knowledge is essential for motivating updated practices in infection prevention and control, becoming the knowledge that informs one's actions [25].

Work motivation is a force that generates enthusiasm or incentive for individuals or groups to engage in their tasks to achieve objectives. High work motivation among IPC officers fuels energy for work and guides activities during their professional duties. Research conducted in several regional hospitals indicates that the factors most correlated with the performance of IPC officers are work motivation, length of service, and education (p<0.05) [26]. High motivation can enhance IPC officers' performance, leading to quality patient care, effective infection prevention, and optimal service delivery.

Compensation refers to any form of payment provided to an individual for services rendered to an organization. Consequently, compensation serves as a mechanism that boosts employees' affective commitment to their work and fosters a strong sense of belonging to their organization. Affective commitment is a critical element through which an organization's vision and mission can be realized within a set timeframe [27]. It is the responsibility of leadership to assess and improve payment model factors as well as non-monetary factors to enhance employee affective commitment

[28].

The analysis of the hypotheses further indicates that emotional commitment positively correlates with the performance of IPC Committee members in Southeast Sulawesi. Enhanced emotional engagement among employees results in a higher readiness to invest effort and energy in achieving organizational objectives. In the healthcare sector, a study demonstrated that strong dedication to work significantly affects work-related behaviors [29]. Earlier research also confirms a strong positive relationship between emotional commitment and employee performance.

According to the findings of the analysis, improving the competencies of committee members (particularly in areas of knowledge, soft skills, and hard skills), along with their well-being and recognition of their contributions, will lead to an increased focus on achieving organizational goals by the committee members. Moreover, employees who have developed emotional connections with the organization will ultimately see a positive impact on their performance [30]. Therefore, fostering the affective commitment of committee members is essential to inspire and motivate them to excel. This can be accomplished by meeting their socio-emotional needs and introducing initiatives to enhance their skills.

To boost the commitment of committee members towards achieving organizational goals, it is essential to consider several key factors, such as enhancing the competencies of committee members, particularly in knowledge, soft skills, and hard skills, improving the welfare of committee members, and recognizing their contributions. This strategy will indirectly nurture an emotional bond between the committee members and the organization, ultimately having a positive effect on their performance [30]. Therefore, to motivate and encourage employees to perform effectively, organizations should cultivate emotional commitment among employees. This can be achieved by meeting their socio-emotional needs and organizing activities to improve their competencies.

Both theoretical and empirical evidence indicate that employee performance is influenced by a complex array of factors. Yet, current research has been limited to examining the roles of work competence, compensation, and emotional commitment in relation to employee performance. Moving forward, it is crucial to include other relevant variables to fully address the complexity of this issue. To strengthen the findings of this study, the research model could be expanded to cover additional subjects or locations. This would allow for a more comprehensive and varied understanding of the factors affecting employee performance.

Conclusion

Compensation and emotional commitment have a significant impact on the performance of committee members, with employee competence emerging as a notable factor among others. It is also vital to maintain employees' strong commitment to their work, as this significantly influences the performance of the PPI committee members in Southeast Sulawesi. The combination of job competence, compensation, and affective commitment has a significant impact on employee performance, highlighting the importance of addressing these three factors collectively to improve performance. Effectively enhancing commitment, which can be achieved by providing appropriate recognition, can lead to improved employee performance.

Acknowledgments: We express our deepest gratitude to the director of Halu Oleo University, Indonesia for supporting this research.

Ethical Permissions: The ethics committee of the Indonesian Association of Public Health Experts, Southeast Sulawesi Province approved this study (80/KEPK-IAKMI/VI.2023).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Kusumawati PA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Samdin S (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (15%); Takdir D (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Tosepu R. (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Saimin J (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (10%); Zaid S (Sixth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (10%); Sudayasa IP (Seventh Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

In recent times, there has been a global focus on the quality of health services, driven by increasing demands from all sectors of society [1, 2]. In response to this demand, numerous countries have initiated the development of various indicators to assess the quality of health services, with accreditation being one such important measure [3, 4]. A primary objective of hospital accreditation is the reduction of infection risks. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) refer to infections that occur in patients during their treatment in hospitals or other healthcare facilities, and which were either not present or dormant at the time of admission [5]. This definition also encompasses infections acquired in the hospital but only manifesting after the patient's discharge. It is worth noting that IPC can affect not only patients but also healthcare workers and hospital staff. According to a survey conducted in the United States, HAIs reached a staggering 722,000 cases in acute care units, resulting in 75,000 patient deaths in 2016 [3]. HAIs are also a concern in Indonesia, where several studies have documented their prevalence [6].

Infection prevention and control (IPC) should not be perceived as an isolated professional component but rather as a set of principles that, when implemented effectively, can reduce the risk of patients or individuals contracting infections [7]. To enhance service quality, the establishment of a patient safety (patient and public involvement (PPI)) committee within hospitals is imperative [8]. In Southeast Sulawesi, healthcare facilities under the Southeast Sulawesi Provincial Health Service have established IPC committees. These committees comprise various healthcare professionals, including IPC doctors, IPC nurses, general practitioners, specialist doctors, dentists, ward nurses, and other healthcare workers. As of March 31, 2023, the Southeast Sulawesi IPC Committee consisted of 447 members. However, there is room for improvement in the performance of the Southeast Sulawesi PPI committee, as evidenced by the prevalence of infections (HAIs) in Southeast Sulawesi District Hospitals exceeding the national average (more than 1%).

Employee performance, particularly within the IPC committee, is influenced by various factors, with work competency being a significant one [7, 9]. Employees who possess strong competencies consistently exhibit intelligent thinking, reliability, experience, skills, and professionalism, resulting in optimal work outcomes in terms of quantity, quality, time efficiency, and budgetary effectiveness within the organization [10, 11]. Martini et al. [12] have shown a direct correlation between work competency and employee performance; higher competence in a job typically leads to enhanced performance. In contrast, Efendi & Yusuf [13] did not identify a significant impact of work competency on employee performance. In our study, we have refined the measure of work competency by categorizing skills into two distinct areas: soft skills and hard skills. This categorization is particularly relevant because PPI committee members are healthcare professionals who employ numerous technical skills in their roles yet are required to master several soft skills when joining the committee.

Compensation is another pivotal factor that can influence employee performance. Employee dissatisfaction often arises from inadequate remuneration, whether in the form of monetary rewards or facilities provided as recognition for their work [14]. Employees engage in work with the expectation that their livelihood needs will be fulfilled, and organizations are expected to compensate employees commensurately for their contributions. Ekhsan and Septian [15] found that favorable compensation positively impacts employee performance, while Astuti [16] has demonstrated that fair and adequate compensation can enhance employee performance within the healthcare sector. Indeed, there exists a positive correlation between good compensation and employee performance, although some research suggests no direct influence of compensation on employee performance, as evidenced by Idris et al. [17] in the study conducted on the three main campuses in Indonesia.

In addition to work competency and compensation, a staff's dedication to the organization can significantly impact their performance. As per Robbins [18], there are three types of work commitment: affective commitment, norm-based commitment, and continuance commitment. Among these, affective commitment holds particular importance as it encapsulates the core essence of commitment—the emotional bond between employees and their organization—and forms the most steadfast connection within its conceptual framework [19].

Our study departs from previous research by evaluating the performance of IPC committee members and includes affective commitment as a mediating variable between work competency and compensation. This innovative approach adds novelty to our research in comparison to prior studies. The present study seeks to explore and evaluate how the capabilities and incentives of committee members influence their performance, with emotional commitment serving as a linking factor.

Instrument and Methods

Study Design

This explanatory research aimed to provide explanations for causal relationships between variables.

Participants

The research was conducted at the regional general hospital (RSUD), under the auspices of the Southeast Sulawesi Provincial Health Service, from April to September 2023. The study's population consisted of Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Committee members (n=447) working in 17 regional hospitals throughout Southeast Sulawesi.

Sample Size

The sample size was 447 individuals determined by cluster random sampling using the Slovin formula considering a 5% margin of error.

Research Tools and Data Collection

For data collection, a questionnaire-based survey was chosen as the primary instrument. The advantage of using questionnaire surveys is their ability to accommodate large sample sizes without being constrained by geographical boundaries. The data collection process utilized closed-ended questions, with predetermined response options for the respondents to select from. The researchers adapted instruments from previous studies to measure various variables. Competency was evaluated using knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA)-based competency indicators developed by Huang et al. [20] and Zhang [21]. Compensation was assessed using indicators formulated by Teclemichael Tessema and Soeters [22], whereas affective commitment was measured with indicators devised by Meyer et al. [23]. Employee performance was assessed using task performance indicators developed by Koopmans et al. [24]. The survey utilized a five-point Likert scale, allowing participants to assign ratings to each statement as follows: 1 for strongly disagree, 2 for disagree, 3 for neutral, 4 for agree, and 5 for strongly agree.

A series of tests were conducted to evaluate the reliability and validity of the indicators used in this study. These evaluations included assessing outer loading and convergent validity (average variance extracted, AVE) for validity, alongside composite reliability and Cronbach's alpha for reliability. The outcomes of these tests confirmed that the indicators were both reliable and valid, thus supporting the model used. In particular, the indicators showed an outer loading value greater than 0.50, a composite reliability exceeding 0.70, and an AVE value above 0.5, all of which signify strong validity and reliability. Each indicator achieved outer loading and AVE values above 0.5, and composite reliability and Cronbach's Alpha values higher than 0.60.

Ethics

The ethics committee of the Indonesian Association of Public Health Experts, Southeast Sulawesi Province approved this study (80/KEPK-IAKMI/VI.2023).

Statistical Tests

After collecting the data and conducting validity and reliability tests, the data was analyzed by SPSS 24. The analysis was carried out using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method, which involved three stages of evaluation: the measurement model assessment, the structural model assessment, and the hypothesis testing phase.

Findings

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. The frequency of respondents’ demographic characteristics

The participants in this study were health workers who were members of the IPC Committee, with the majority being room nurses and other health workers, comprising 65 (30.66%) and 94 (44.34%) individuals, respectively.

The study applied R-square (R2), Q-square (Q2), and goodness of fit (GoF) measures to assess the model's fit. Based on the evaluation of the model's appropriateness criteria, all indicators suggested that the research model was highly accurate. The results of the model fit test indicated that the affective commitment variable had an R2 of 0.643 and a Q2 of 0.466. The employee performance showed an R2 of 0.755 and a Q2 of 0.553. Furthermore, the GoF demonstrated a value of 0.683.

There was a significant positive relationship between competence and employee performance (R2: 0.220; p-value=0.0001). Similarly, a significant positive effect of competence on emotional commitment was observed (R2: 0.430; p-value=0.0001). Compensation had a significant positive effect on the performance of committee members (R2=0.133; p-value=0.015). Likewise, a strong significant effect of compensation on emotional commitment was found (R2=0.449; p-value=0.000). Additionally, affective commitment had a strong significant effect on the performance of committee members (R2=0.589; p-value=0.000) (Table 2).

Table 2. Direct effect analysis

Figure 1 shows the results of the hypothesis analysis.

Figure 1. Hypothesis analysis results.

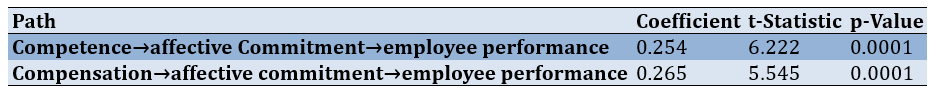

The results presented in Table 3 illustrate the role of affective commitment as a mediator in the relationship between competence and the performance of committee members (r=0.254; p<0.0001). Statistically, there was a significant increase in the path value from 0.220, which indicates the direct effect of competence on committee members' performance, to 0.254, representing the indirect impact of competence on performance through affective commitment. This indicates that affective commitment enhances the link between competence and employee performance. Also, affective commitment played a mediating role in the relationship between compensation and employee performance (r=0.265, p-value=0.0001). Compensation had a significant effect on affective commitment and employee performance, suggesting that affective commitment acted as a partial mediator.

Table 3. Indirect effect analysis

Discussion

The findings of the current study validate the proposed model and notably emphasize the mediating role of emotional commitment in its relationship with employee competence, compensation, and performance. Moreover, the study discovered that proficiencies, including knowledge, soft skills, hard skills, and attitudes, significantly and positively affect the emotional commitment and performance of committee members of the Southeast Sulawesi IPC. The results strongly indicate that substantial improvements in knowledge, soft skills, hard skills, and attitudes enhance emotional commitment and employee performance. The analysis showed that the contribution of knowledge surpasses that of other competency elements, suggesting that enhancing knowledge would have a more significant impact compared to other competency elements. Therefore, to improve commitment and performance, IPC committee members in Southeast Sulawesi should give priority to increasing knowledge, followed by improving other competency elements. It is also important to acknowledge that other competency elements, such as soft skills, hard skills, and attitudes, significantly impact the performance of committee members.

Knowledge is identified as the primary individual factor. This aligns with research conducted in Intensive Care Units (ICU), which demonstrates a significant correlation between knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, and nurses' occupational health and safety measures in infection control. Adequate knowledge is essential for motivating updated practices in infection prevention and control, becoming the knowledge that informs one's actions [25].

Work motivation is a force that generates enthusiasm or incentive for individuals or groups to engage in their tasks to achieve objectives. High work motivation among IPC officers fuels energy for work and guides activities during their professional duties. Research conducted in several regional hospitals indicates that the factors most correlated with the performance of IPC officers are work motivation, length of service, and education (p<0.05) [26]. High motivation can enhance IPC officers' performance, leading to quality patient care, effective infection prevention, and optimal service delivery.

Compensation refers to any form of payment provided to an individual for services rendered to an organization. Consequently, compensation serves as a mechanism that boosts employees' affective commitment to their work and fosters a strong sense of belonging to their organization. Affective commitment is a critical element through which an organization's vision and mission can be realized within a set timeframe [27]. It is the responsibility of leadership to assess and improve payment model factors as well as non-monetary factors to enhance employee affective commitment

[28].

The analysis of the hypotheses further indicates that emotional commitment positively correlates with the performance of IPC Committee members in Southeast Sulawesi. Enhanced emotional engagement among employees results in a higher readiness to invest effort and energy in achieving organizational objectives. In the healthcare sector, a study demonstrated that strong dedication to work significantly affects work-related behaviors [29]. Earlier research also confirms a strong positive relationship between emotional commitment and employee performance.

According to the findings of the analysis, improving the competencies of committee members (particularly in areas of knowledge, soft skills, and hard skills), along with their well-being and recognition of their contributions, will lead to an increased focus on achieving organizational goals by the committee members. Moreover, employees who have developed emotional connections with the organization will ultimately see a positive impact on their performance [30]. Therefore, fostering the affective commitment of committee members is essential to inspire and motivate them to excel. This can be accomplished by meeting their socio-emotional needs and introducing initiatives to enhance their skills.

To boost the commitment of committee members towards achieving organizational goals, it is essential to consider several key factors, such as enhancing the competencies of committee members, particularly in knowledge, soft skills, and hard skills, improving the welfare of committee members, and recognizing their contributions. This strategy will indirectly nurture an emotional bond between the committee members and the organization, ultimately having a positive effect on their performance [30]. Therefore, to motivate and encourage employees to perform effectively, organizations should cultivate emotional commitment among employees. This can be achieved by meeting their socio-emotional needs and organizing activities to improve their competencies.

Both theoretical and empirical evidence indicate that employee performance is influenced by a complex array of factors. Yet, current research has been limited to examining the roles of work competence, compensation, and emotional commitment in relation to employee performance. Moving forward, it is crucial to include other relevant variables to fully address the complexity of this issue. To strengthen the findings of this study, the research model could be expanded to cover additional subjects or locations. This would allow for a more comprehensive and varied understanding of the factors affecting employee performance.

Conclusion

Compensation and emotional commitment have a significant impact on the performance of committee members, with employee competence emerging as a notable factor among others. It is also vital to maintain employees' strong commitment to their work, as this significantly influences the performance of the PPI committee members in Southeast Sulawesi. The combination of job competence, compensation, and affective commitment has a significant impact on employee performance, highlighting the importance of addressing these three factors collectively to improve performance. Effectively enhancing commitment, which can be achieved by providing appropriate recognition, can lead to improved employee performance.

Acknowledgments: We express our deepest gratitude to the director of Halu Oleo University, Indonesia for supporting this research.

Ethical Permissions: The ethics committee of the Indonesian Association of Public Health Experts, Southeast Sulawesi Province approved this study (80/KEPK-IAKMI/VI.2023).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Kusumawati PA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Samdin S (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (15%); Takdir D (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Tosepu R. (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Saimin J (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (10%); Zaid S (Sixth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (10%); Sudayasa IP (Seventh Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Communication

Received: 2023/10/29 | Accepted: 2023/11/13 | Published: 2024/01/20

Received: 2023/10/29 | Accepted: 2023/11/13 | Published: 2024/01/20

References

1. Anell A, Glenngård AH, Merkur S. Sweden: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012;14(5):1-159. [Link]

2. Panzer RJ, Gitomer RS, Greene WH, Webster PR, Landry KR, Riccobono CA. Increasing demands for quality measurement. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1971-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.282047]

3. World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Link]

4. Nair M, Baltag V, Bose K, Boschi-Pinto C, Lambrechts T, Mathai M. Improving the quality of health care services for adolescents, globally: A standards-driven approach. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(3):288-98. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.011]

5. Al-Tawfiq JA, Tambyah PA. Healthcare associated infections (HAI) perspectives. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(4):339-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jiph.2014.04.003]

6. Gantz NR, Sherman R, Jasper M, Choo CG, Herrin‐Griffith D, Harris K. Global nurse leader perspectives on health systems and workforce challenges. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20(4):433-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01393.x]

7. Danasekaran R, Mani G, Annadurai K. Prevention of healthcare-associated infections: protecting patients, saving lives. I J Community Med Public Health. 2014;1(1):67-8. [Link] [DOI:10.5455/2394-6040.ijcmph20141114]

8. Albano GD, Bertozzi G, Maglietta F, Montana A, Di Mizio G, Esposito M, et al. Medical records quality as prevention tool for healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) related litigation: A case series. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2019;20(8):653-7. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1389201020666190408102221]

9. De Angelis G, Murthy A, Beyersmann J, Harbarth S. Estimating the impact of healthcare-associated infections on length of stay and costs. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(12):1729-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03332.x]

10. Garg N. Workplace spirituality and organizational performance in Indian context: Mediating effect of organizational commitment, work motivation and employee engagement. South Asian J Human Resource Manag. 2017;4(2):191-211. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2322093717736134]

11. Chong VK, Law MBC. The effect of a budget-based incentive compensation scheme on job performance: The mediating role of trust-in-supervisor and organizational commitment. J Account Organizational Change. 2016;12(4):590-613. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/JAOC-02-2015-0024]

12. Martini IAO, Supriyadinata AANE, Sutrisni KE, Sarmawa IWG. The dimensions of competency on worker performance mediated by work commitment. Cogent Business Management. 2020;7(1). [Link] [DOI:10.1080/23311975.2020.1794677]

13. Efendi S, Yusuf A. Influence of competence, compensation and motivation on employee performance with job satisfaction as intervening variable in the environment of indonesian professional certification authority. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research (IJEBAR). 2021;5(3):1078-88. [Link]

14. Hendri MI. The mediation effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on the organizational learning effect of the employee performance. Int J Productivity Performance Manag. 2019;68(7):1208-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/IJPPM-05-2018-0174]

15. Ekhsan M, Septian B. The influence of work stress, work conflict and compensation on employee performance. MASTER: Journal of Entrepreneurial Strategic Management. 2021;1(1):11-8. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.37366/master.v1i1.25]

16. Astuti R. The influence of compensation and motivation on employee performance at PT. Tunas Jaya Utama. JBusiness Management Eka Prasetya Management Science Research. 2019;5(2):1-10. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.47663/jmbep.v5i2.22]

17. Idris, Adi KR, Soetjipto BE, Supriyanto AS. The mediating role of job satisfaction on compensation, work environment, and employee performance: Evidence from Indonesia. J Entrepreneurship Sustainability Issues. 2020;8(2):735-50. [Link] [DOI:10.9770/jesi.2020.8.2(44)]

18. Robbins SPTA. Judge, Organizational Behavior, 12th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2006. [Link]

19. Cohen A. Multiple Commitments in the Workplace: An Integrative Approach. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Link]

20. Huang X, Li Z, Wang J, Cao E, Zhuang G, Xiao F, et al. A KSA system for competency-based assessment of clinicians' professional development in China and quality gap analysis. Medical Educ Online. 2022;27(1):2037401. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10872981.2022.2037401]

21. Zhang A. Peer assessment of soft skills and hard skills. J Inform Technol Educ Res. 2012;11(1):155-68. [Link] [DOI:10.28945/1634]

22. Teclemichael Tessema M, Soeters JL. Challenges and prospects of HRM in developing countries: Testing the HRM-performance link in the Eritrean civil service. Int J Human Resource Manag. 2006;17(1):86-105. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09585190500366532]

23. Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appli Psychol. 1993;78(4):538-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538]

24. Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, van Buuren S, van der Beek AJ, de Vet HCW. Improving the Individual Work Performance Questionnaire using Rasch analysis. J Appl Meas. 2014;15(2):160-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t35489-000]

25. Salawati L. Control of Nosocomial Infections in Hospital Intensive Care Units. J Syiah Kuala Medicine. 2012;12(1):47-52. [Indonesian] [Link]

26. Gunawan H. Motivation as a factor affecting nurse performance in Regional General Hospitals: A factors analysis. Enfermería Clín. 2019;29(2):515-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.04.078]

27. Kim S. Individual-level factors and organizational performance in government organizations. J Public Administration Res Theory. 2004;15(2):245-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jopart/mui013]

28. Bartlett KR. The relationship between training and organizational commitment: A study in the health care field. Human Resource Dev Qua. 2001;12(4):335-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/hrdq.1001]

29. Sharma J, Dhar RL. Factors influencing job performance of nursing staff: Mediating role of affective commitment. Personnel Rev. 2016;45(1):161-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/PR-01-2014-0007]

30. Kuvaas B. Work performance, affective commitment, and work motivation: the roles of pay administration and pay level. J Organizational Behav. 2006;27(3):365-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/job.377]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |