Volume 11, Issue 4 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(4): 621-626 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sohrabi M, Bakhtiarpour S, Sohrabi F, Eftekhar Saadi Z, Asgari P. Effect of Contextual Schema Therapy on Body Image and Psychosomatic Symptoms in Individuals with Perfectionism Disorder. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (4) :621-626

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-71245-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-71245-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Schema therapy [Mesh], Psychosomatic Medicine [MeSH], Body Image [MeSH], Perfectionism [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 781 kb]

(3263 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1831 Views)

Full-Text: (328 Views)

Introduction

Perfectionism is often defined as a positive trait that can lead to increased chances of individual success. However, this trait can give rise to negative thought patterns and make achieving goals more difficult [1]. Perfectionism can result in stress, anxiety, mental disorders, and other psychological issues in individuals [2, 3]. Negative perfectionism is a destructive personality trait with significant negative impacts on individuals' daily lives. Perfectionistic individuals set exceedingly high and unrealistic standards for their lives, and if they fail to meet these standards, they become dissatisfied and unhappy [4]. Negative perfectionism is a psychological disorder that has become increasingly prevalent in today's life full of stress and competition [5]. Humans have always been engaged in various concerns, such as body image about their biological and psychological well-being in the face of challenges and life problems [6].

Body image, beyond representing personal identity, indicates an individual's social identity. Research has shown an increasing prevalence of dissatisfaction with physical appearance and body image among adolescents, young adults, and adults [7]. How an individual perceives their body, in terms of self-concept, can significantly affect their ability to interact with others and influence the responses they receive from others [8]. Furthermore, this perception can affect an individual's body image, his/her confidence in social situations, and the nature of v social relationships. Prior research has demonstrated a relationship between dissatisfaction with body image and overall well-being. Individuals dissatisfied with their body image experience psychological pressures and exhibit a decline in general well-being [9]. In other words, individuals' dissatisfaction with their body image, influenced by personal and environmental factors, can lead to inaccurate evaluations, negative thoughts, and emotions. Concerns about body image are negatively related to irrational beliefs and mental health as a whole [10, 11]. Psychological health problems sometimes manifest as physical issues and psychosomatic complaints, which, if not identified and addressed promptly, can become chronic and lead to future problems [12].

In recent decades, a new type of illness categorized as psychosomatic disorder has emerged, in which emotional and cognitive factors play a role in their onset and persistence [13]. The emergence of psychosomatic disorders is often attributed to negative emotions, fears, and anxieties in individuals [14]. The average prevalence of psychosomatic disorders among clinical populations seeking medical services ranges from 6 to 15% and in some studies, it has been approximately 20% [15]. Psychosomatic symptoms, defined as the occurrence of bodily complaints, do not have fundamental reasons and are common in medical disorders and psychological issues. The results of a study indicated a prevalence of 17.7% for psychosomatic symptoms among Iranian students aged 10 to 18; thus, given the increasing prevalence of these symptoms, investigating the underlying factors of this issue is of significant importance [16]. Psychosomatic disorders can manifest as mental distress, unresolved life issues, major loss, deep personal injury, or disrespect [17]. According to the psychoanalytic perspective, these symptoms might indicate unmet desires being expressed in an incompatible manner. Unrealistic expectations, social tension, and various stresses, especially when lacking social or familial support, are among the influential factors in this context and can lead to immediate or delayed adverse consequences for the individual [18]. Emotions play a fundamental and influential role in the onset of psychological illnesses. Therefore, a study focusing on interventions that enhance emotional self-regulation can be an effective step toward improving the quality of life and promoting the mental health and well-being of individuals with negative perfectionism.

Schemas develop during childhood and serve as templates for processing subsequent experiences. The reflection of incompatible schemas often gives rise to unconditional beliefs about oneself [19]. Contextual schema therapy, while maintaining the integrity of Young's model through the integration of concepts and interventions derived from the third-wave cognitive therapy model, has been designed to expand traditional schema therapy [20]. Contextual schema therapy is an integrative therapeutic approach that combines traditional schema therapy with actual effects and treatments of the third wave. It is interspersed throughout with acceptance and commitment therapy. This approach exemplifies the adaptability of schema therapy to various perspectives within the same context. Contextual schema therapy, drawing from other therapeutic approaches, such as mindfulness, cognitive therapy, acceptance, metacognition, and human values, offers a comprehensive approach [21]. Young et al. [20] introduced schema therapy for the treatment of patients with personality issues and chronic mental disorders. A schema or cognitive structure is a relatively stable cognitive organization that categorizes, decodes, and evaluates incoming information; it is through schemas that raw data are transformed into cognition. Contextual schema therapy combines the four major therapeutic techniques and employs them based on therapeutic conditions. These techniques include cognitive, behavioral, experiential, and interpersonal techniques. The use of cognitive techniques enables patients to challenge schemas and question their validity on a logical level [22]. Teaching behavioral techniques reduces anxiety and stress and serves as a useful method for reducing behavioral disorders [23]. Ostadian Khani et al. [24] reported that the implementation of contextual schema therapy was effective in enhancing the flexibility of body image mental representation. Beckmann et al. [25] demonstrated that changes in body schema using cognitive-behavioral techniques could be efficient in improving neural anorexia. Moreover, Shaker Dioulagh and Salman Poor [26] indicated that contextual schema therapy led to an increase in positive mood and a decrease in negative mood among individuals with psychological-somatic disorders.

Most previous studies have examined the effectiveness of the traditional form of schema therapy. Thus, the present study aimed to test and determine the effectiveness of contextual schema therapy, an integrative therapeutic approach that combines traditional schema therapy with actual effects and third-wave treatments. This approach exemplifies the adaptability of schema therapy to various perspectives within the same context. Based on the issues outlined in the background, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of contextual schema therapy on body image and psychosomatic symptoms in individuals with perfectionism disorder.

Materials and Methods

The research method employed was quasi-experimental. To this end, 12 individuals diagnosed with negative perfectionism disorder who sought psychological services in Tehran in 2022 were purposefully selected. The inclusion criteria were willingness to participate, age between 20 and 40 years, diagnosis of negative perfectionism, body dysmorphic tendencies, and psychosomatic symptoms diagnosed by a psychologist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria and the research questionnaires. The exclusion criteria consisted of dissatisfaction with continued participation, absenteeism from more than two sessions, concurrent medication use, and failure to respond to over 10% of the questionnaire items. After conducting a pre-test, the participants attended 40 sessions of 60 minutes each of contextual schema therapy. Before completing the questionnaires, participants' readiness, justification, and sensitivity reduction were ensured through ethical considerations, including informed consent, privacy protection, confidentiality, as well as necessary explanations for questionnaire completion, and voluntary participation. Subsequently, the participants completed the research questionnaires in three stages: pre-test, mid-test, and post-test.

Tools

Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ): This questionnaire was developed by Cash et al. [27] with 46 items and employs a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "very dissatisfied" (1) to "very satisfied" (5). It consists of three subscales assessing evaluation, attention, and behavior, with the physical appearance evaluation scale primarily employed in body image studies. The questionnaire measures six components, including appearance evaluation, appearance orientation, body area satisfaction, appearance importance, body area overweight preoccupation, and appearance investment. The reliability of the MBSRQ Persian version was obtained as 0.98 using Cronbach’s alpha [28].

Psychosomatic Complaints Scale: This scale was designed by Takata and Sakata [29] and includes 30 items. Respondents indicate the frequency of experiencing each item through a selection from "never" (0) to "repeatedly" (3). The possible score range for this scale is 0 to 90. The reliability of its Persian version was obtained as 0.85 using Cronbach’s alpha [30].

Intervention

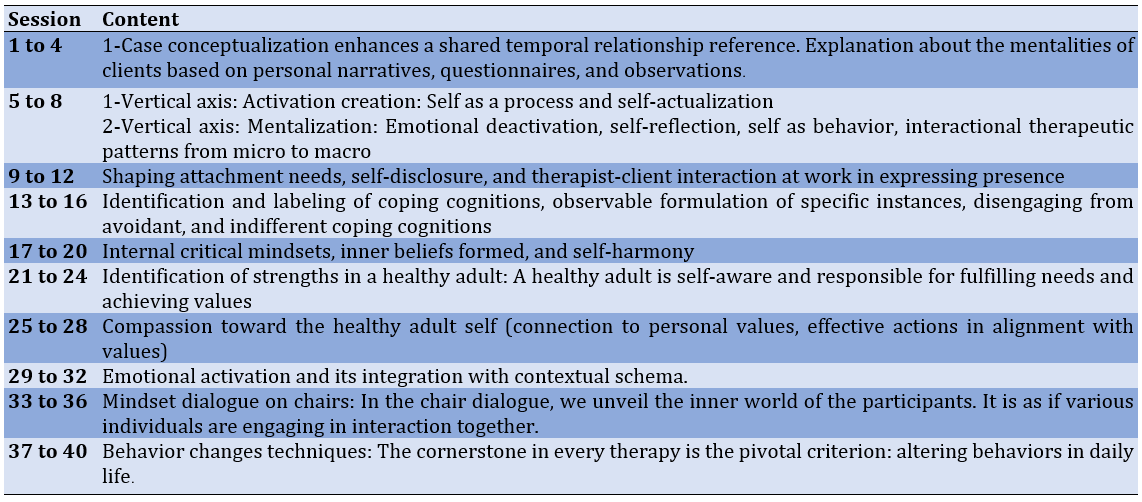

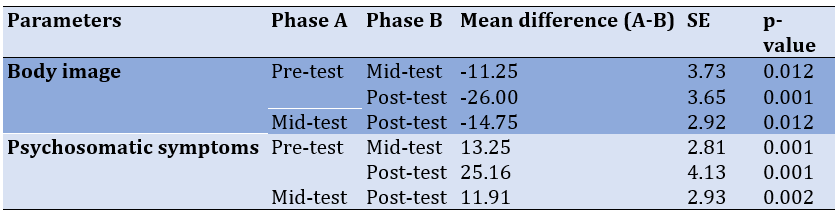

Contextual Schema Therapy: Contextual schema therapy was developed based on the contextual schema therapy approach by Young et al. [20], as further elaborated by Roediger et al. [21]. The intervention program was delivered over 40 therapy sessions, with each session tailored to the objectives of schema therapy, focusing on the tasks assigned to participants to reduce body dysmorphic tendencies and improve psychological well-being. A summary of the intervention sessions is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. A summary of the contextual schema therapy sessions

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26 software. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis (to assess the normal distribution of the data), as well as inferential statistical tests, such as repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), were utilized for the analysis of the research data.

Findings

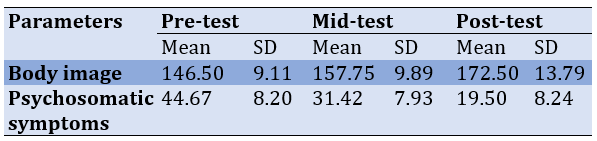

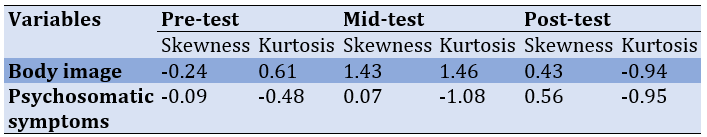

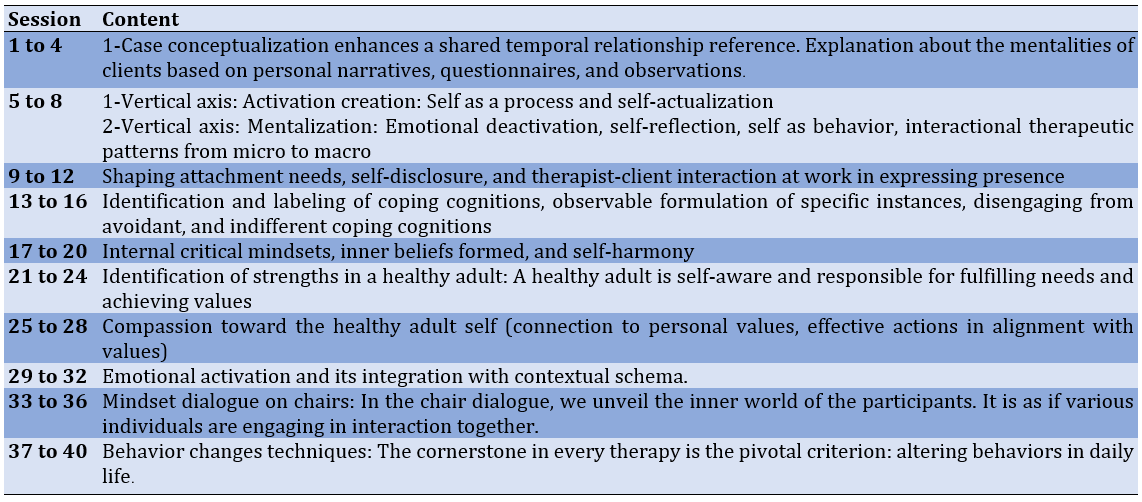

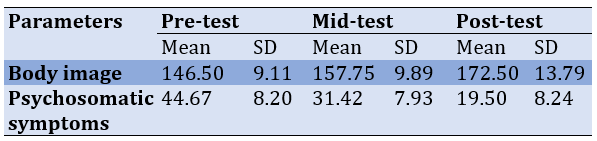

Descriptive results of body image and psychosomatic symptoms are detailed in Table 2. First, the assumptions of the repeated-measures ANOVA were scrutinized, including evaluating the normality of score distributions, the uniformity of covariances, and the assumption of sphericity. To assess the normality of the trait, kurtosis and skewness were applied (Table 3). Accordingly, the presumption of normality of score distributions about the variables within the research cohort was substantiated.

Table 2. Mean values of body image and psychosomatic symptoms in the pre-test, mid-test, and post-test stages

Table 3. The normality test results of the scores of body image and psychosomatic symptoms

Before the repeated measures ANOVA, the sphericity assumption was checked by performing Mauchly's sphericity test. Mauchly's test was not significant for the body image and emotional regulation variables, indicating that the sphericity assumption was met. However, for psychosomatic symptoms, Mauchly's test was significant, suggesting a violation of the sphericity assumption. Hence, the epsilon correction was applied to address this variable.

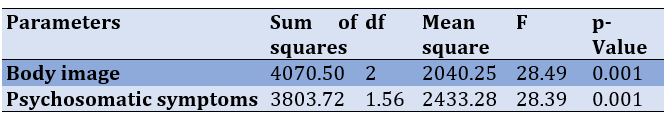

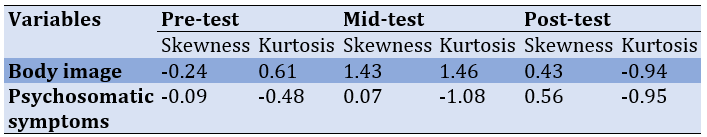

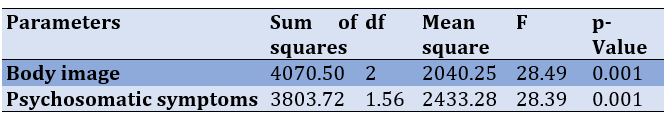

To discern notable discrepancies across distinct stages, a one-way repeated ANOVA was implemented (Table 4). The impact of contextual schema therapy intervention on both body image (F=27.49, p<0.001) and psychosomatic symptoms (F=28.38, p<0.001) was significant. For a more intricate examination of specific stages (pre-test, mid-test, and post-test) bearing significant disparities, an LSD post-hoc test was employed (Table 5).

Table 4. Results of repeated measures ANOVA to investigate within-group effects on body image and psychosomatic symptoms

Table 5. LSD post-hoc test for paired comparison of the body image and psychosomatic symptoms across time series

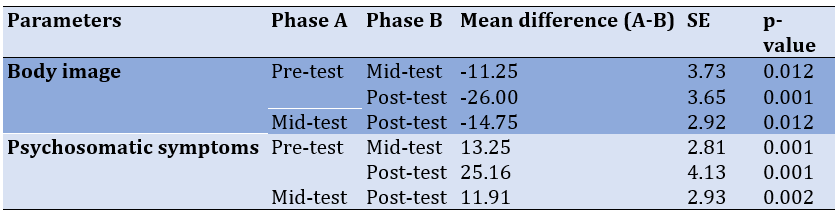

Substantial disparities were noted among the pre-test and mid-test, pre-test and post-test, as well as mid-test and post-test assessments for both body image and psychosomatic symptoms. The impact of time (or schema therapy intervention) on body image and psychosomatic symptoms was statistically significant, not only in the mid-test compared to the pre-test but also in the post-test compared to the mid-test (p<0.01).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of contextual schema therapy on body image and psychosomatic symptoms in individuals with perfectionism disorder. Contextual schema therapy had a significant impact on improving body image concerns in individuals with perfectionism disorder. These findings are consistent with those of Beckmann et al. [25] who suggested that individuals struggling with body image concerns unconsciously perceive their body size as larger than reality, possibly stemming from negative bodily schemata. Individuals with body image concerns are confronted with a distorted self-evaluation of their appearance and body, which is characterized by exaggerated self-criticism, doubts about their actions and mistakes, and concerns about personal standards and others' expectations [24]. In schema therapy, the goal is to first identify the initial maladaptive schemas and the initial experiences that resulted in the disorder and problem. In the next stage, by changing these schemas and mentalities, the person's drive to behaviors related to concern about body image is reduced. Therefore, interventions focusing on altering these negative body schemata are recommended.

People suffering from perfectionism have excessive mental preoccupation with their physical appearance so that their performance in different areas of life is affected and makes them susceptible to suffering from psychological disorders and disturbances in many aspects of life. Disturbing images and thoughts about their physical appearance reduce their quality of life and daily functioning. It seems that by using cognitive, experiential, behavioral, and interpersonal guides, the participants achieved the reconstruction of negative cognitions and bitter memories about the body. By correcting unhealthy patterns, they were able to improve their negative self-evaluation and have a more positive understanding of their body. As Ostadian Khani et al. [24] demonstrated, schema therapy significantly influenced participants' flexibility of body image.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of contextual schema therapy in mitigating psychosomatic symptoms among individuals diagnosed with perfectionism disorder exhibited notable significance. This result is in line with that of Stroink et al. [31]. In line with the findings of the present study, Sobhani et al. [32] indicated a decrease in maladaptive schemata and an increase in adaptive schemata among patients who underwent emotion-focused schema therapy. Shaker Dioulagh and Salman Poor [26] revealed that contextual schema therapy resulted in a noteworthy decrease in maladaptive initial schemata and an elevation in positive mood, along with a reduction in negative mood among individuals dealing with psychological and somatic disorders. Psychosomatic symptoms, characterized by somatic manifestations arising from psychological anguish, can potentially signify emotional distress or unresolved profound life encounters. According to psychoanalytic perspectives, these symptoms may indicate unmet desires in an incompatible manner [1]. Psychosomatic symptoms can act as a protective mechanism of the brain, directing attention to the body to avoid confronting repressed or threatening unconscious emotions. This increased focus on undesirable experiences can lead to negative consequences, like panic attacks, migraines, etc. Awareness of these events among individuals is crucial [13]. In other words, these incompatible schemata play a role in the development and progression of psychosomatic disorders [19]. Therefore, interventions targeting these schemata could effectively modify these maladaptive cognitive structures.

The goal of schema therapy is to moderate the maladaptive schemas of the person suffering from perfectionism and help the client align him/herself with new experiences that do not confirm the original schema and create more adaptive coping behaviors. Moreover, schema therapy's main goal is to weaken the primary maladaptive schema and, if possible, create a healthy schema. In schema therapy, the therapist helps the patient to make healthier choices, and abandon maladaptive coping behaviors and self-harming behavior patterns in life. As such, it is reasonable to hypothesize that contextual schema therapy initially ameliorates body image concerns and psychosomatic symptoms by mitigating incongruent and maladaptive emotional regulation strategies, such as self-criticism, mental self-blame, and catastrophic thinking.

This study had several limitations. Primarily, the restricted sample size stemming from temporal and resource limitations, alongside the absence of a control group, and the omission of an evaluation of treatment effectiveness accounting for participants' demographic attributes and individual variations, are notable. Thus, for forthcoming research endeavors in this domain, we advocate the utilization of a more expansive sample size to bolster the extensibility of findings. Additionally, we propose the incorporation of a control group to augment methodological rigor. Taking into account the demographic characteristics to control for individual differences among participants can lead to more accurate measurements.

Conclusion

Contextual schema therapy effectively reduces psychosomatic symptoms and improves body image concerns in individuals with perfectionism disorder. These results contribute to the advancement of psychological science, especially in the field of therapeutic interventions, advocating the use of contextual schema therapy to enhance psychosomatic symptoms and body image concerns in individuals seeking psychological services.

Ethics Considerations: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz branch (IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1401.151).

Acknowledgments: The researchers wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interests were declared.

Authors’ Contribution: Sohrabi M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (20%); Bakhtiarpour S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Sohrabi F (Third Author), Discussion Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Eftekhar Saadi Z (Fourth Author), Methodologist/ Discussion Writer (15%); Asgari P (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%)

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Perfectionism is often defined as a positive trait that can lead to increased chances of individual success. However, this trait can give rise to negative thought patterns and make achieving goals more difficult [1]. Perfectionism can result in stress, anxiety, mental disorders, and other psychological issues in individuals [2, 3]. Negative perfectionism is a destructive personality trait with significant negative impacts on individuals' daily lives. Perfectionistic individuals set exceedingly high and unrealistic standards for their lives, and if they fail to meet these standards, they become dissatisfied and unhappy [4]. Negative perfectionism is a psychological disorder that has become increasingly prevalent in today's life full of stress and competition [5]. Humans have always been engaged in various concerns, such as body image about their biological and psychological well-being in the face of challenges and life problems [6].

Body image, beyond representing personal identity, indicates an individual's social identity. Research has shown an increasing prevalence of dissatisfaction with physical appearance and body image among adolescents, young adults, and adults [7]. How an individual perceives their body, in terms of self-concept, can significantly affect their ability to interact with others and influence the responses they receive from others [8]. Furthermore, this perception can affect an individual's body image, his/her confidence in social situations, and the nature of v social relationships. Prior research has demonstrated a relationship between dissatisfaction with body image and overall well-being. Individuals dissatisfied with their body image experience psychological pressures and exhibit a decline in general well-being [9]. In other words, individuals' dissatisfaction with their body image, influenced by personal and environmental factors, can lead to inaccurate evaluations, negative thoughts, and emotions. Concerns about body image are negatively related to irrational beliefs and mental health as a whole [10, 11]. Psychological health problems sometimes manifest as physical issues and psychosomatic complaints, which, if not identified and addressed promptly, can become chronic and lead to future problems [12].

In recent decades, a new type of illness categorized as psychosomatic disorder has emerged, in which emotional and cognitive factors play a role in their onset and persistence [13]. The emergence of psychosomatic disorders is often attributed to negative emotions, fears, and anxieties in individuals [14]. The average prevalence of psychosomatic disorders among clinical populations seeking medical services ranges from 6 to 15% and in some studies, it has been approximately 20% [15]. Psychosomatic symptoms, defined as the occurrence of bodily complaints, do not have fundamental reasons and are common in medical disorders and psychological issues. The results of a study indicated a prevalence of 17.7% for psychosomatic symptoms among Iranian students aged 10 to 18; thus, given the increasing prevalence of these symptoms, investigating the underlying factors of this issue is of significant importance [16]. Psychosomatic disorders can manifest as mental distress, unresolved life issues, major loss, deep personal injury, or disrespect [17]. According to the psychoanalytic perspective, these symptoms might indicate unmet desires being expressed in an incompatible manner. Unrealistic expectations, social tension, and various stresses, especially when lacking social or familial support, are among the influential factors in this context and can lead to immediate or delayed adverse consequences for the individual [18]. Emotions play a fundamental and influential role in the onset of psychological illnesses. Therefore, a study focusing on interventions that enhance emotional self-regulation can be an effective step toward improving the quality of life and promoting the mental health and well-being of individuals with negative perfectionism.

Schemas develop during childhood and serve as templates for processing subsequent experiences. The reflection of incompatible schemas often gives rise to unconditional beliefs about oneself [19]. Contextual schema therapy, while maintaining the integrity of Young's model through the integration of concepts and interventions derived from the third-wave cognitive therapy model, has been designed to expand traditional schema therapy [20]. Contextual schema therapy is an integrative therapeutic approach that combines traditional schema therapy with actual effects and treatments of the third wave. It is interspersed throughout with acceptance and commitment therapy. This approach exemplifies the adaptability of schema therapy to various perspectives within the same context. Contextual schema therapy, drawing from other therapeutic approaches, such as mindfulness, cognitive therapy, acceptance, metacognition, and human values, offers a comprehensive approach [21]. Young et al. [20] introduced schema therapy for the treatment of patients with personality issues and chronic mental disorders. A schema or cognitive structure is a relatively stable cognitive organization that categorizes, decodes, and evaluates incoming information; it is through schemas that raw data are transformed into cognition. Contextual schema therapy combines the four major therapeutic techniques and employs them based on therapeutic conditions. These techniques include cognitive, behavioral, experiential, and interpersonal techniques. The use of cognitive techniques enables patients to challenge schemas and question their validity on a logical level [22]. Teaching behavioral techniques reduces anxiety and stress and serves as a useful method for reducing behavioral disorders [23]. Ostadian Khani et al. [24] reported that the implementation of contextual schema therapy was effective in enhancing the flexibility of body image mental representation. Beckmann et al. [25] demonstrated that changes in body schema using cognitive-behavioral techniques could be efficient in improving neural anorexia. Moreover, Shaker Dioulagh and Salman Poor [26] indicated that contextual schema therapy led to an increase in positive mood and a decrease in negative mood among individuals with psychological-somatic disorders.

Most previous studies have examined the effectiveness of the traditional form of schema therapy. Thus, the present study aimed to test and determine the effectiveness of contextual schema therapy, an integrative therapeutic approach that combines traditional schema therapy with actual effects and third-wave treatments. This approach exemplifies the adaptability of schema therapy to various perspectives within the same context. Based on the issues outlined in the background, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of contextual schema therapy on body image and psychosomatic symptoms in individuals with perfectionism disorder.

Materials and Methods

The research method employed was quasi-experimental. To this end, 12 individuals diagnosed with negative perfectionism disorder who sought psychological services in Tehran in 2022 were purposefully selected. The inclusion criteria were willingness to participate, age between 20 and 40 years, diagnosis of negative perfectionism, body dysmorphic tendencies, and psychosomatic symptoms diagnosed by a psychologist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria and the research questionnaires. The exclusion criteria consisted of dissatisfaction with continued participation, absenteeism from more than two sessions, concurrent medication use, and failure to respond to over 10% of the questionnaire items. After conducting a pre-test, the participants attended 40 sessions of 60 minutes each of contextual schema therapy. Before completing the questionnaires, participants' readiness, justification, and sensitivity reduction were ensured through ethical considerations, including informed consent, privacy protection, confidentiality, as well as necessary explanations for questionnaire completion, and voluntary participation. Subsequently, the participants completed the research questionnaires in three stages: pre-test, mid-test, and post-test.

Tools

Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ): This questionnaire was developed by Cash et al. [27] with 46 items and employs a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "very dissatisfied" (1) to "very satisfied" (5). It consists of three subscales assessing evaluation, attention, and behavior, with the physical appearance evaluation scale primarily employed in body image studies. The questionnaire measures six components, including appearance evaluation, appearance orientation, body area satisfaction, appearance importance, body area overweight preoccupation, and appearance investment. The reliability of the MBSRQ Persian version was obtained as 0.98 using Cronbach’s alpha [28].

Psychosomatic Complaints Scale: This scale was designed by Takata and Sakata [29] and includes 30 items. Respondents indicate the frequency of experiencing each item through a selection from "never" (0) to "repeatedly" (3). The possible score range for this scale is 0 to 90. The reliability of its Persian version was obtained as 0.85 using Cronbach’s alpha [30].

Intervention

Contextual Schema Therapy: Contextual schema therapy was developed based on the contextual schema therapy approach by Young et al. [20], as further elaborated by Roediger et al. [21]. The intervention program was delivered over 40 therapy sessions, with each session tailored to the objectives of schema therapy, focusing on the tasks assigned to participants to reduce body dysmorphic tendencies and improve psychological well-being. A summary of the intervention sessions is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. A summary of the contextual schema therapy sessions

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26 software. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis (to assess the normal distribution of the data), as well as inferential statistical tests, such as repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), were utilized for the analysis of the research data.

Findings

Descriptive results of body image and psychosomatic symptoms are detailed in Table 2. First, the assumptions of the repeated-measures ANOVA were scrutinized, including evaluating the normality of score distributions, the uniformity of covariances, and the assumption of sphericity. To assess the normality of the trait, kurtosis and skewness were applied (Table 3). Accordingly, the presumption of normality of score distributions about the variables within the research cohort was substantiated.

Table 2. Mean values of body image and psychosomatic symptoms in the pre-test, mid-test, and post-test stages

Table 3. The normality test results of the scores of body image and psychosomatic symptoms

Before the repeated measures ANOVA, the sphericity assumption was checked by performing Mauchly's sphericity test. Mauchly's test was not significant for the body image and emotional regulation variables, indicating that the sphericity assumption was met. However, for psychosomatic symptoms, Mauchly's test was significant, suggesting a violation of the sphericity assumption. Hence, the epsilon correction was applied to address this variable.

To discern notable discrepancies across distinct stages, a one-way repeated ANOVA was implemented (Table 4). The impact of contextual schema therapy intervention on both body image (F=27.49, p<0.001) and psychosomatic symptoms (F=28.38, p<0.001) was significant. For a more intricate examination of specific stages (pre-test, mid-test, and post-test) bearing significant disparities, an LSD post-hoc test was employed (Table 5).

Table 4. Results of repeated measures ANOVA to investigate within-group effects on body image and psychosomatic symptoms

Table 5. LSD post-hoc test for paired comparison of the body image and psychosomatic symptoms across time series

Substantial disparities were noted among the pre-test and mid-test, pre-test and post-test, as well as mid-test and post-test assessments for both body image and psychosomatic symptoms. The impact of time (or schema therapy intervention) on body image and psychosomatic symptoms was statistically significant, not only in the mid-test compared to the pre-test but also in the post-test compared to the mid-test (p<0.01).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of contextual schema therapy on body image and psychosomatic symptoms in individuals with perfectionism disorder. Contextual schema therapy had a significant impact on improving body image concerns in individuals with perfectionism disorder. These findings are consistent with those of Beckmann et al. [25] who suggested that individuals struggling with body image concerns unconsciously perceive their body size as larger than reality, possibly stemming from negative bodily schemata. Individuals with body image concerns are confronted with a distorted self-evaluation of their appearance and body, which is characterized by exaggerated self-criticism, doubts about their actions and mistakes, and concerns about personal standards and others' expectations [24]. In schema therapy, the goal is to first identify the initial maladaptive schemas and the initial experiences that resulted in the disorder and problem. In the next stage, by changing these schemas and mentalities, the person's drive to behaviors related to concern about body image is reduced. Therefore, interventions focusing on altering these negative body schemata are recommended.

People suffering from perfectionism have excessive mental preoccupation with their physical appearance so that their performance in different areas of life is affected and makes them susceptible to suffering from psychological disorders and disturbances in many aspects of life. Disturbing images and thoughts about their physical appearance reduce their quality of life and daily functioning. It seems that by using cognitive, experiential, behavioral, and interpersonal guides, the participants achieved the reconstruction of negative cognitions and bitter memories about the body. By correcting unhealthy patterns, they were able to improve their negative self-evaluation and have a more positive understanding of their body. As Ostadian Khani et al. [24] demonstrated, schema therapy significantly influenced participants' flexibility of body image.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of contextual schema therapy in mitigating psychosomatic symptoms among individuals diagnosed with perfectionism disorder exhibited notable significance. This result is in line with that of Stroink et al. [31]. In line with the findings of the present study, Sobhani et al. [32] indicated a decrease in maladaptive schemata and an increase in adaptive schemata among patients who underwent emotion-focused schema therapy. Shaker Dioulagh and Salman Poor [26] revealed that contextual schema therapy resulted in a noteworthy decrease in maladaptive initial schemata and an elevation in positive mood, along with a reduction in negative mood among individuals dealing with psychological and somatic disorders. Psychosomatic symptoms, characterized by somatic manifestations arising from psychological anguish, can potentially signify emotional distress or unresolved profound life encounters. According to psychoanalytic perspectives, these symptoms may indicate unmet desires in an incompatible manner [1]. Psychosomatic symptoms can act as a protective mechanism of the brain, directing attention to the body to avoid confronting repressed or threatening unconscious emotions. This increased focus on undesirable experiences can lead to negative consequences, like panic attacks, migraines, etc. Awareness of these events among individuals is crucial [13]. In other words, these incompatible schemata play a role in the development and progression of psychosomatic disorders [19]. Therefore, interventions targeting these schemata could effectively modify these maladaptive cognitive structures.

The goal of schema therapy is to moderate the maladaptive schemas of the person suffering from perfectionism and help the client align him/herself with new experiences that do not confirm the original schema and create more adaptive coping behaviors. Moreover, schema therapy's main goal is to weaken the primary maladaptive schema and, if possible, create a healthy schema. In schema therapy, the therapist helps the patient to make healthier choices, and abandon maladaptive coping behaviors and self-harming behavior patterns in life. As such, it is reasonable to hypothesize that contextual schema therapy initially ameliorates body image concerns and psychosomatic symptoms by mitigating incongruent and maladaptive emotional regulation strategies, such as self-criticism, mental self-blame, and catastrophic thinking.

This study had several limitations. Primarily, the restricted sample size stemming from temporal and resource limitations, alongside the absence of a control group, and the omission of an evaluation of treatment effectiveness accounting for participants' demographic attributes and individual variations, are notable. Thus, for forthcoming research endeavors in this domain, we advocate the utilization of a more expansive sample size to bolster the extensibility of findings. Additionally, we propose the incorporation of a control group to augment methodological rigor. Taking into account the demographic characteristics to control for individual differences among participants can lead to more accurate measurements.

Conclusion

Contextual schema therapy effectively reduces psychosomatic symptoms and improves body image concerns in individuals with perfectionism disorder. These results contribute to the advancement of psychological science, especially in the field of therapeutic interventions, advocating the use of contextual schema therapy to enhance psychosomatic symptoms and body image concerns in individuals seeking psychological services.

Ethics Considerations: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz branch (IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1401.151).

Acknowledgments: The researchers wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interests were declared.

Authors’ Contribution: Sohrabi M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (20%); Bakhtiarpour S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Sohrabi F (Third Author), Discussion Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Eftekhar Saadi Z (Fourth Author), Methodologist/ Discussion Writer (15%); Asgari P (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%)

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2023/08/25 | Accepted: 2023/11/4 | Published: 2023/11/19

Received: 2023/08/25 | Accepted: 2023/11/4 | Published: 2023/11/19

References

1. Feizollahi Z, Asadzadeh H, Mousavi SR. Prediction of symptoms of psychosomatic disorders in university students based on perfectionism mediated by smartphone addiction. Caspian J Health Res. 2022;7(3):151-8. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/CJHR.7.3.421.1.7]

2. Suh H, Liou PY, Jeong J, Kim SY. Perfectionism, prolonged stress reactivity, and depression: A two-wave cross-lagged analysis. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2022;1-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10942-022-00483-x]

3. Wang Y, Chen J, Zhang X, Lin X, Sun Y, Wang N, et al. The relationship between perfectionism and social anxiety: A moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12934. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph191912934]

4. Zhang Y, Bai X, Yang W. The chain mediating effect of negative perfectionism on procrastination: An ego depletion perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):9355. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19159355]

5. Nazari N. Perfectionism and mental health problems: Limitations and directions for future research. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(14):4709-12. [Link] [DOI:10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4709]

6. Kiani-Sheikhabadi M, Beigi M, Mohebbi-Dehnavi Z. The relationship between perfectionism and body image with eating disorder in pregnancy. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:242. [Link]

7. Jafari M, Lamiyan M, Hajizadeh E. Relationship between health literacy and special quality of life and body image in women undergone mastectomy in reproductive age. Health Educ Health Promot. 2018;6(3):109-15. [Link] [DOI:10.29252/HEHP.6.3.109]

8. Berry RA, Rodgers RF, Campagna J. Outperforming iBodies: A conceptual framework integrating body performance self-tracking technologies with body image and eating concerns. Sex Roles. 2021;85:1-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11199-020-01201-6]

9. Hicks RE, Kenny B, Stevenson S, Vanstone DM. Risk factors in body image dissatisfaction: Gender, maladaptive perfectionism, and psychological wellbeing. Heliyon. 2022;8(6):e09745. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09745]

10. Molaeinezhad M, Scheidt C, Afshar H, Jahanfar S, Sohran F, Salehi M, et al. Bodily map of emotions in Iranian people. Health Educ Health Promot. 2021;9(2):153-64. [Link] [DOI:10.31234/osf.io/m9qsv]

11. Prnjak K, Jukic I, Tufano JJ. Perfectionism, body satisfaction and dieting in athletes: The role of gender and sport type. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(8):181. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/sports7080181]

12. McComb SE, Mills JS. The effect of physical appearance perfectionism and social comparison to thin-, slim-thick-, and fit-ideal Instagram imagery on young women's body image. Body Image. 2022;40:165-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.003]

13. Desai KM, Kale AD, Shah PU, Rana S. Psychosomatic disorders: A clinical perspective and proposed classification system. Arch Iran Med. 2018;21(1):44-5. [Link]

14. Tatayeva R, Ossadchaya E, Sarculova S, Sembayeva Z, Koigeldinova S. Psychosomatic aspects of the development of comorbid pathology: A review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2022;36:152. [Link] [DOI:10.47176/mjiri.36.152]

15. Bakhshi Bajestani A, Shahabizadeh F, Vaziri S, Lotfi Kashani F. The effectiveness of short-term psychoanalysis treatment in decreasing psychological distress and psychosomatic symptoms in patients with gastrointestinal dysfunction with personality type D. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2022;13(4):1-11.[Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/nkums.13.4.1]

16. Rezapour M, Soori H, Nezam Tabar A, Khanjani N. Psychosomatic problems and their relation with types of involvement in school bullying in Iranian students: A cross-sectional study. Int J School Health. 2020;7(1):6-13. [Link]

17. Bransfield RC, Friedman KJ. Differentiating psychosomatic, somatopsychic, multisystem illnesses, and medical uncertainty. Healthcare (Basel). 2019;7(4):114. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare7040114]

18. Walsh SD, Kolobov T, Raiz Y, Boniel-Nissim M, Tesler R, Harel-Fisch Y. The role of identity and psychosomatic symptoms as mediating the relationship between discrimination and risk behaviors among first and second generation immigrant adolescents. J Adolesc. 2018;64:34-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.01.004]

19. Kaya Tezel F, Tutarel Kişlak Ş, Boysan M. Relationships between childhood traumatic experiences, early maladaptive schemas and interpersonal styles. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2015;52(3):226-32. [Link] [DOI:10.5152/npa.2015.7118]

20. Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME. Schema therapy: A practitioners guide. New York: The Guilford Press; 2003. [Link]

21. Roediger E, Stevens BA, Brockman R. Contextual schema therapy: An integrative approach to personality disorders, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal functioning. Oakland: context press; 2018. [Link]

22. Emamzamani Z, Rahimian Boogar I, Mashhadi A. Effectiveness of contextual schema therapy for fear of negative evaluation and fear of positive evaluation in individuals with social anxiety disorder: Single subject design. Psychol Achiev. 2023;30(2):1-8. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/shenakht.10.3.1]

23. Curtiss JE, Levine DS, Ander I, Baker AW. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety and stress-related disorders. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19(2):184-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1176/appi.focus.20200045]

24. Ostadian Khani Z, Hassani F, Sepahmansour S, Keshavarziarshad F. The comparison of the efficacy of therapy based on acceptance and commitment and schema therapy on body image flexibility of the body and impulsivity among women with Binge eating disorder. J Appl Family Ther. 2021;2(4):285-309. [Persian] [Link]

25. Beckmann N, Baumann P, Herpertz S, Trojan J, Diers M. How the unconscious mind controls body movements: Body schema distortion in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(4):578-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/eat.23451]

26. Shaker Dioulagh A, Salman Poor H. The effectiveness of schema therapy on modifying the first maladaptive schemas and reducing mood syndrome in suffers with skin disorders. Pars J Med Sci. 2022;15(4):46-52. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/jmj.15.4.46]

27. Cash TF. The multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. MBSRQ User's Manual (Third revision). Washington: APA PsycTests; 2000. [Link]

28. Shemshadi H, Shams A, Sahaf R, Shamsipour Dehkordi P, Zareian H, Moslem AR. Psychometric properties of Persian version of the multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire (MBSRQ) among Iranian elderly. Salmand: Iran J Ageing. 2020;15(3):298-311. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/sija.15.3.61.13]

29. Takata Y, Sakata Y. Development of a psychosomatic complaints scale for adolescents. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(1):3-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01184.x]

30. Hajloo N. Psychometric properties of Takata and Sakata's psychosomatic complaints scale among Iranian university students. J Res Behav Sci. 2012;10(3):204-12. [Link]

31. Stroink L, Mens E, Ooms MHP, Visser S. Maladaptive schemas of patients with functional neurological symptom disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2022;29(3):933-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2671]

32. Sobhani Z, Hosseini SV, Honarparvaran N, Khazraei H, Amini M, Hedayati A. The effectiveness of an online video-based group schema therapy in improvement of the cognitive emotion regulation strategies in women who have undergone bariatric surgery. BMC Surg. 2023;23(1):98. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12893-023-02010-w]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |