Volume 11, Issue 2 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(2): 189-194 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Baihaqi B, Hidayah A, Rujito L. Awareness of Non-Health Students about Premarital Genetic Screening; A Study in Indonesia. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (2) :189-194

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-67348-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-67348-en.html

1- Department of Genetics and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Purwokerto, Indonesia

Keywords: Premarital Examinations [MeSH], Screening [MeSH], Genetic Screening [MeSH], Medicine [MeSH], Medical Student [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 811 kb]

(3771 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1997 Views)

Full-Text: (524 Views)

Introduction

In Indonesia, health concerns are not limited to infectious or communicable diseases but also include non-infectious diseases like genetic, geriatric, and occupational diseases or trauma. To address these issues, the government has implemented several health initiatives aimed at improving facilities and infrastructure, enhancing healthcare accessibility at peripheral levels, and promoting the equalization and empowerment of health human resources [1]. Vaccines and widespread immunization efforts can prevent some infectious diseases. Although the government has focused on promotive, preventive, and educational efforts for non-communicable diseases, implementing these measures has not been optimal. This is evident in the government's failure to meet targets such as reducing maternal and infant mortality rates, decreasing stunting, and alleviating the financial burden of catastrophic infections on the healthcare system [2].

Couples in Indonesia must undergo premarital health screenings or check-ups before getting married to assess the health of both individuals [3]. Unfortunately, premarital health screenings only focus on basic health determinants such as hemoglobin levels, tetanus vaccination, and vital signs. These check-ups have not been effectively utilized for more comprehensive purposes, such as preventing catastrophic diseases. In fact, according to national health system reports, the most common catastrophic conditions are heart disease, cancer, stroke, thalassemia, and hemophilia, which can incur high costs. Genetic diseases like thalassemia and hemophilia, in particular, could be prevented through targeted screening, such as premarital genetic screening [4].

Premarital screening involves a series of tests conducted on couples who are planning to get married. The purpose of these tests is to identify any genetic, infectious, or blood-borne diseases that could pose a risk of transmission to their offspring. This measure is taken to prevent the risk of transmitting any diseases from the parents to their children [5]. The incidence of hereditary diseases, such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia, as well as infectious diseases like hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS, has been reduced by premarital screening [6]. Mediterranean countries can suppress the birth of Talasemia up to zero [7]. Carriers of other recessive genetic diseases, such as Phenylketonuria and Cystic Fibrosis, can be detected during premarital screening with appropriate methods. Premarital screening can generally include examination of children and adolescents and premarital examinations [8].

Effective premarital and genetic screening implementation requires education on the purpose, procedures, interpretation of results, and follow-up of test results. Countries such as Saudi Arabia have experienced a significant decrease in the number of high-risk marriages after six years of implementing the effective premarital program. This may lead to a substantial reduction in the genetic disease burden in the country over the next few decades [9]. They reported that knowledge of genetics and the prevention of genetic diseases was essential for achieving the desired outcomes of these screenings [9, 10]. Studies indicated that the decision of couples, after receiving their premarital screening results and counseling, is influenced by their knowledge and perceptions of the screening program as well as the consequences of related diseases. Thus, higher levels of knowledge are associated with a lower probability of engaging in high-risk marriages [11].

There is a lack of awareness regarding premarital screening among the general public in Indonesia, partly due to insufficient information provided during college education. Even among healthcare professionals, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to premarital screening are still limited, as evidenced by the data. Although healthcare professionals have a slight advantage in terms of knowledge, their utilization of this knowledge for screening purposes is relatively low compared to other developed countries [12].

Non-healthcare professionals represent a significant portion of the population who will be impacted by the implementation of premarital and genetic screening. Nonetheless, data are scarce on the readiness of this group for the adoption of premarital screening, especially genetic disease screening, in Indonesia. This study aimed to collect information on the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of non-healthcare professionals concerning the implementation of premarital screening in Indonesia. The insights gained from this study could aid policy-makers in developing evidence-based policies.

Instruments and Methods

The research is a cross-sectional descriptive study that was conducted on non-healthcare students from the southern region of Central Java as participants. The Slovin formula was used to determine an appropriate research subject sample size. In this case, 400 subjects were selected from a student population of 59,844 using simple random sampling and in proportion to the size of the universities they attended. The recruitment process took place over a period of four weeks, between December 2020 and January 2021, from a total of 15 universities.

One of the study variables was knowledge of premarital screening, which was measured using a 15-question questionnaire on genetics, mode of inheritance, and screening. The correct answer to 76-100% of the questions was considered as good knowledge, the correct answer to 56-75% of the questions was considered as sufficient knowledge, and the correct answer to less than 55% of the questions was considered as poor knowledge.

The attitude of the respondents were assessed using a 12-question questionnaire that was divided into positive and negative attitudes. If the mean score of the questionnaire was higher than the average, the attitude was classified as positive, and if the mean score was lower than the average, it was classified as negative. The questionnaire included 7 statements related to the respondent's tendency to engage in premarital screening. The behavior of the respondents was judged based on their willingness to support and actively participate in premarital screening efforts, with responses classified as good or bad. All questionnaires were tested for validity and reliability. The questionnaires were distributed to participants in online form using the Google Form application as part of the research process. The researchers and enumerators visited the university as scheduled, where they obtained informed consent from all participants. The researcher gathered the participants in large groups and provided them with an overview of the research goals and the steps involved in completing the questionnaire.

Each participant filled out the questionnaire independently, under the supervision of the enumerator and the researcher. The information was documented and later analyzed through univariate and bivariate statistical tests, including the Chi-Square test, with a significance level of 0.05.

Findings

The knowledge level in 55.5% of respondents was sufficient, in 42.5% was poor, and only in 2% was good. Most respondents (57.3%) had a positive attitude, while 42.8% had a negative attitude. The majority of the respondents exhibited a positive attitude toward all indicators, except for actively seeking information. Specifically, 230 respondents (57.5%) had a negative attitude toward this indicator, while 170 respondents (42.5%) had a positive attitude (Table 1).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of attitude picture toward premarital and genetic screening based on indicators

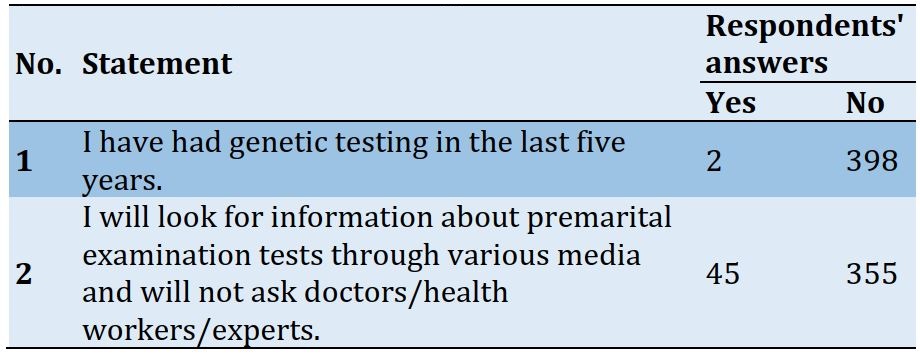

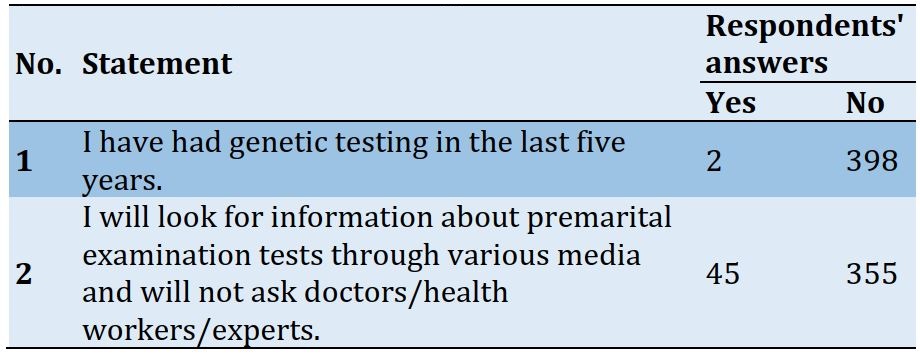

355 respondents (88.75%) displayed positive behavior toward premarital genetic screening, while the remaining 45 respondents (11.25%) exhibited negative behavior (Table 2).

Table 2) Frequency distribution of respondents' behavior toward premarital and genetic screening

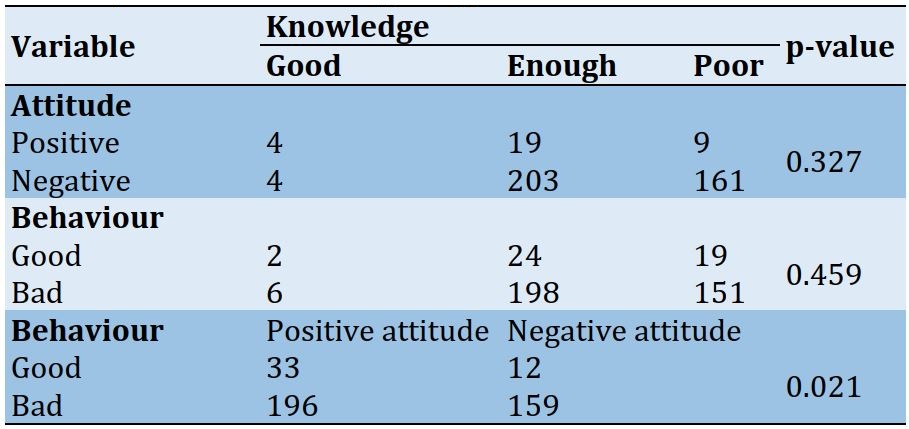

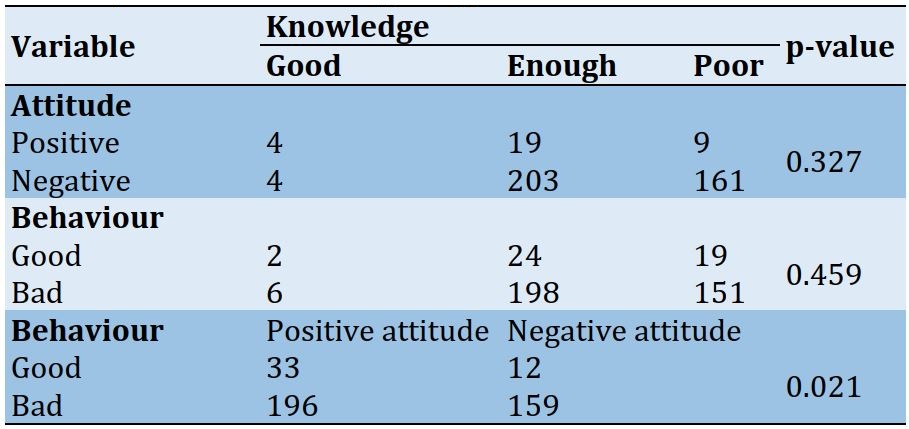

There was no significant relationship between knowledge with attitude and behavior (p>0.05). On the other hand, a significant relationship was observed between attitude and behavior (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 3) Relationship between knowledge, behavior and attitude toward premarital screening and genetics

Discussion

Based on the findings, non-medical and health students in Indonesia possessed a relatively lower level of knowledge regarding premarital and genetic screening compared to other countries. Out of the 400 participants in this study, a mere 2% demonstrated a commendable level of knowledge. Conversely, a study conducted in Jordan that involved the general public as respondents found that an impressive 65.4% of participants displayed a good understanding of genetics [13]. In the United States, a survey on knowledge of genetics indicated that 57.6% of respondents were familiar with genetic terminologies. However, when participants were asked to provide detailed responses to test their comprehension, only 22.2% could furnish correct answers [14]. Furthermore, in Saudi Arabia, a study involving students showed that 42.9% had a satisfactory level of knowledge [15].

There exist several factors that can affect an individual's level of knowledge, which include education, interests, information, experience, and age [16]. Typically, an individual's comprehension of genetics develops during their academic years. In this regard, teachers play an integral role, as their level of understanding and critical approach toward scientific subjects can significantly influence a student's ability to grasp the concept of genetics and its practical applications [17]. Insufficient knowledge can result in attitudes that fail to reflect the significance or reality of the need for screening programs. One approach to enhancing knowledge and encouraging positive attitudes is to enhance the quality of education by integrating the latest genetic and genomic information into the curriculum taught in schools [18].

The perception that genetics is an intricate and abstract subject is another element that could contribute to low levels of knowledge. Prior research has consistently revealed that students often find genetics to be a challenging subject to grasp. Some of the primary challenges experienced by students include domain-specific jargon and vocabulary, mathematical concepts related to Mendel's laws of genetics, the process of cytology, and the intricate and abstract nature of genetics. Moreover, genetics can be especially daunting for learners since genetic phenomena are not visible and are not directly observable [19].

Another factor that may contribute to low levels of knowledge about premarital and genetic screening is the lack of awareness and interest among students in seeking information on these topics. According to the data collected, only 45 out of 400 respondents have ever sought information about genetics, either from healthcare professionals or other sources. Indonesia is ranked 60th out of 61 countries in the World's Most Literate Nations survey for 2017 in terms of literacy skills [20]. According to the Ministry of Education and Culture, data from the Indonesia National Assessment Program in 2016 showed that 46.83% of Indonesian students had low reading abilities, 6.06% had good reading abilities, and 47.11% had sufficient reading abilities [21]. The low literacy rate in Indonesia is a multifaceted issue that stems from several factors. One of the contributing factors is the inadequate emphasis on reading habits within the school system, which is further compounded by a scarcity of reading and information resources. Additionally, an unsupportive reading environment has also been identified as a crucial factor in the low literacy rate in Indonesia [22].

Notwithstanding, our findings indicated that the majority of non-medical and health students exhibited a favorable disposition toward genetic and premarital screening. This is a positive finding from a health perspective, as it suggests that the respondents understand and appreciate the importance of these screenings, as well as their potential advantages and disadvantages. However, this positive attitude does not necessarily translate into good behavior. The issue of privacy and stigmatization is a sensitive subject matter concerning premarital and genetic screening, particularly with regards to the results emanating from these evaluations. The society's stigma of individuals with disorders revealed through premarital and genetic screening can be especially prevalent in cases of hereditary illnesses [23].

In this study, the majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the results of genetic and premarital screenings should be shared with others, such as family members and partners, as indicated in the "openness of results" indicator. There is a need for more public education from the government about genetic and premarital screening, including Thalassemia screening [24]. The presence of healthcare professionals, such as doctors, who can provide education and information about genetics can also influence the decision to undergo premarital and genetic screening. According to Di Mattei et al. in 2018, effective counseling by healthcare workers about the benefits, risks, and processes involved in genetic screening can impact an individual's decision to undergo this type of screening. In addition to the availability of information, the cost of genetic screening can also be a factor that influences behavior. The high cost of these tests may make them unaffordable for some people [25]. The lack of facilities and the high cost of genetic screening services have hindered the optimal implementation of premarital and genetic screening programs to support public health.

Out of 400 respondents, 355 (88.75%) had bad or poor behaviors toward screening. This behavior could indicate a lack of support for premarital screening programs. The statistical association between knowledge and behaviors toward premarital and genetic screening did not attain significance. Typically, insufficient knowledge of scientific concepts can lead to unfavorable attitudes and conducts toward scientific technologies. Thus, if society has a more comprehensive knowledge of science, including genetics, it may harbor a more positive attitude and exhibit more favorable behavior toward technological advancements and their implementation [26]. However, there may be other factors that influence an individual's behavior toward premarital and genetic screening. In some cases, societies with greater knowledge may be more critical of genetic testing, including premarital screening [27]. Further research has produced consistent findings suggesting that more informed societies may exhibit more discrimination and a critical attitude toward certain science-related issues, particularly those with social or moral implications, which are commonly highlighted in the field of genetics [28].

According to theories of behavior formation, an individual's behavior is influenced by three groups of factors: predisposing factors, enabling factors, and reinforcing factors. Predisposing factors include knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values, and culture. Enabling factors include physical resources such as facilities and infrastructure. Reinforcing factors include the support of community leaders and healthcare professionals [29].

Premarital and genetic screening behaviors can also be influenced by the experiences and opinions of others. Healthcare professionals, particularly doctors, can play a vital role in shaping the public's understanding of complex genetic information and serve as a valuable source of guidance for individuals making decisions about genetic screening [30, 31]. Limited resources and facilities can also be a factor influencing behavior. In Indonesia, the availability of genetic screening facilities and the cost of these tests are not a priority for the government. Genetic screening facilities are only available in major cities and are not widely accessible throughout the country. As a result, the government has not established regulations and referral systems for patients with genetic disorders. This lack of access to care results in a high number of untreated genetic disease patients at the primary care level [32].

The study data corroborate previous research, indicating a correlation between attitudes and behaviors toward genetic screening. While attitudes and behaviors typically align, this is not always the case. A person's attitude is a crucial factor that influences decision-making. Although a child's favorable attitude toward health may not necessarily translate to positive behaviors, an unfavorable attitude toward health is likely to impede one's behavior [33]. According to the theory of planned behavior, a person's attitude toward a particular behavior is a subjective evaluation (positive or negative) based on their perception of the benefits and drawbacks of the behavior [34]. In general, the respondents in this study had a positive attitude toward genetic and premarital screening programs, but it is interesting to note that the majority of them had negative behaviors related to these programs. One indicator of behavior is the initiative of respondents to seek information about genetic and premarital screening, both through health workers and other sources.

In this study, most respondents indicated that they had never sought information about genetic and premarital screening programs. This is consistent with their general reluctance to actively seek out information, as most of the respondents held negative attitudes toward doing so. Nevertheless, despite their negative attitudes, the respondents still expressed support for these programs. Another noteworthy finding is that the majority of respondents reported never having undergone genetic or premarital screening. This could be due to a lack of information sources that raise awareness about the importance of these programs, as well as a lack of information from authorities, which may reduce respondents' willingness to participate. Another possible explanation for respondents' reluctance or lack of interest in these programs is that they are misinformed or indifferent. By examining how people behaved during the Covid-19 pandemic, health sector actors may be able to gain insights into the factors that influence individuals' behavior toward health programs [35, 36].

The results of this study have important implications for government officials in the development of healthcare policies. Specifically, these findings suggest that it is necessary to establish a comprehensive healthcare system that includes the proper implementation of premarital and genetic screening programs. Therefore, policymakers should take these findings into account when formulating health policies.

The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which imposed restrictions on various activities and learning practices. The study employed an online questionnaire, which allowed subjects to potentially cheat in answering the questions, particularly in terms of knowledge aspects. Future studies would benefit from gathering data during non-pandemic times and employing additional methods to ensure respondent accountability in answering the questions.

Conclusion

There is no relationship between the level of knowledge about genetics and the attitudes and behaviors toward premarital and genetic screening in non-medical and health students in Indonesia. However, there is a significant relationship between attitudes and behaviors toward genetic and premarital screening in these students.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the respondents who participated in this study, as well as to the Banyumas District Education Office for granting permission. This study was partially funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia.

Ethical Permission: The study has been approved by the ethical committee of Jenderal Soedirman University with number 017/KEPK/I/2021.

Conflict of Interests: Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in submitting and publishing this manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution: Baihaqi BS (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Hidayah AN (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Rujito L (Third Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer (35%)

Funding: This study was partially funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia.

In Indonesia, health concerns are not limited to infectious or communicable diseases but also include non-infectious diseases like genetic, geriatric, and occupational diseases or trauma. To address these issues, the government has implemented several health initiatives aimed at improving facilities and infrastructure, enhancing healthcare accessibility at peripheral levels, and promoting the equalization and empowerment of health human resources [1]. Vaccines and widespread immunization efforts can prevent some infectious diseases. Although the government has focused on promotive, preventive, and educational efforts for non-communicable diseases, implementing these measures has not been optimal. This is evident in the government's failure to meet targets such as reducing maternal and infant mortality rates, decreasing stunting, and alleviating the financial burden of catastrophic infections on the healthcare system [2].

Couples in Indonesia must undergo premarital health screenings or check-ups before getting married to assess the health of both individuals [3]. Unfortunately, premarital health screenings only focus on basic health determinants such as hemoglobin levels, tetanus vaccination, and vital signs. These check-ups have not been effectively utilized for more comprehensive purposes, such as preventing catastrophic diseases. In fact, according to national health system reports, the most common catastrophic conditions are heart disease, cancer, stroke, thalassemia, and hemophilia, which can incur high costs. Genetic diseases like thalassemia and hemophilia, in particular, could be prevented through targeted screening, such as premarital genetic screening [4].

Premarital screening involves a series of tests conducted on couples who are planning to get married. The purpose of these tests is to identify any genetic, infectious, or blood-borne diseases that could pose a risk of transmission to their offspring. This measure is taken to prevent the risk of transmitting any diseases from the parents to their children [5]. The incidence of hereditary diseases, such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia, as well as infectious diseases like hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS, has been reduced by premarital screening [6]. Mediterranean countries can suppress the birth of Talasemia up to zero [7]. Carriers of other recessive genetic diseases, such as Phenylketonuria and Cystic Fibrosis, can be detected during premarital screening with appropriate methods. Premarital screening can generally include examination of children and adolescents and premarital examinations [8].

Effective premarital and genetic screening implementation requires education on the purpose, procedures, interpretation of results, and follow-up of test results. Countries such as Saudi Arabia have experienced a significant decrease in the number of high-risk marriages after six years of implementing the effective premarital program. This may lead to a substantial reduction in the genetic disease burden in the country over the next few decades [9]. They reported that knowledge of genetics and the prevention of genetic diseases was essential for achieving the desired outcomes of these screenings [9, 10]. Studies indicated that the decision of couples, after receiving their premarital screening results and counseling, is influenced by their knowledge and perceptions of the screening program as well as the consequences of related diseases. Thus, higher levels of knowledge are associated with a lower probability of engaging in high-risk marriages [11].

There is a lack of awareness regarding premarital screening among the general public in Indonesia, partly due to insufficient information provided during college education. Even among healthcare professionals, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to premarital screening are still limited, as evidenced by the data. Although healthcare professionals have a slight advantage in terms of knowledge, their utilization of this knowledge for screening purposes is relatively low compared to other developed countries [12].

Non-healthcare professionals represent a significant portion of the population who will be impacted by the implementation of premarital and genetic screening. Nonetheless, data are scarce on the readiness of this group for the adoption of premarital screening, especially genetic disease screening, in Indonesia. This study aimed to collect information on the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of non-healthcare professionals concerning the implementation of premarital screening in Indonesia. The insights gained from this study could aid policy-makers in developing evidence-based policies.

Instruments and Methods

The research is a cross-sectional descriptive study that was conducted on non-healthcare students from the southern region of Central Java as participants. The Slovin formula was used to determine an appropriate research subject sample size. In this case, 400 subjects were selected from a student population of 59,844 using simple random sampling and in proportion to the size of the universities they attended. The recruitment process took place over a period of four weeks, between December 2020 and January 2021, from a total of 15 universities.

One of the study variables was knowledge of premarital screening, which was measured using a 15-question questionnaire on genetics, mode of inheritance, and screening. The correct answer to 76-100% of the questions was considered as good knowledge, the correct answer to 56-75% of the questions was considered as sufficient knowledge, and the correct answer to less than 55% of the questions was considered as poor knowledge.

The attitude of the respondents were assessed using a 12-question questionnaire that was divided into positive and negative attitudes. If the mean score of the questionnaire was higher than the average, the attitude was classified as positive, and if the mean score was lower than the average, it was classified as negative. The questionnaire included 7 statements related to the respondent's tendency to engage in premarital screening. The behavior of the respondents was judged based on their willingness to support and actively participate in premarital screening efforts, with responses classified as good or bad. All questionnaires were tested for validity and reliability. The questionnaires were distributed to participants in online form using the Google Form application as part of the research process. The researchers and enumerators visited the university as scheduled, where they obtained informed consent from all participants. The researcher gathered the participants in large groups and provided them with an overview of the research goals and the steps involved in completing the questionnaire.

Each participant filled out the questionnaire independently, under the supervision of the enumerator and the researcher. The information was documented and later analyzed through univariate and bivariate statistical tests, including the Chi-Square test, with a significance level of 0.05.

Findings

The knowledge level in 55.5% of respondents was sufficient, in 42.5% was poor, and only in 2% was good. Most respondents (57.3%) had a positive attitude, while 42.8% had a negative attitude. The majority of the respondents exhibited a positive attitude toward all indicators, except for actively seeking information. Specifically, 230 respondents (57.5%) had a negative attitude toward this indicator, while 170 respondents (42.5%) had a positive attitude (Table 1).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of attitude picture toward premarital and genetic screening based on indicators

355 respondents (88.75%) displayed positive behavior toward premarital genetic screening, while the remaining 45 respondents (11.25%) exhibited negative behavior (Table 2).

Table 2) Frequency distribution of respondents' behavior toward premarital and genetic screening

There was no significant relationship between knowledge with attitude and behavior (p>0.05). On the other hand, a significant relationship was observed between attitude and behavior (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 3) Relationship between knowledge, behavior and attitude toward premarital screening and genetics

Discussion

Based on the findings, non-medical and health students in Indonesia possessed a relatively lower level of knowledge regarding premarital and genetic screening compared to other countries. Out of the 400 participants in this study, a mere 2% demonstrated a commendable level of knowledge. Conversely, a study conducted in Jordan that involved the general public as respondents found that an impressive 65.4% of participants displayed a good understanding of genetics [13]. In the United States, a survey on knowledge of genetics indicated that 57.6% of respondents were familiar with genetic terminologies. However, when participants were asked to provide detailed responses to test their comprehension, only 22.2% could furnish correct answers [14]. Furthermore, in Saudi Arabia, a study involving students showed that 42.9% had a satisfactory level of knowledge [15].

There exist several factors that can affect an individual's level of knowledge, which include education, interests, information, experience, and age [16]. Typically, an individual's comprehension of genetics develops during their academic years. In this regard, teachers play an integral role, as their level of understanding and critical approach toward scientific subjects can significantly influence a student's ability to grasp the concept of genetics and its practical applications [17]. Insufficient knowledge can result in attitudes that fail to reflect the significance or reality of the need for screening programs. One approach to enhancing knowledge and encouraging positive attitudes is to enhance the quality of education by integrating the latest genetic and genomic information into the curriculum taught in schools [18].

The perception that genetics is an intricate and abstract subject is another element that could contribute to low levels of knowledge. Prior research has consistently revealed that students often find genetics to be a challenging subject to grasp. Some of the primary challenges experienced by students include domain-specific jargon and vocabulary, mathematical concepts related to Mendel's laws of genetics, the process of cytology, and the intricate and abstract nature of genetics. Moreover, genetics can be especially daunting for learners since genetic phenomena are not visible and are not directly observable [19].

Another factor that may contribute to low levels of knowledge about premarital and genetic screening is the lack of awareness and interest among students in seeking information on these topics. According to the data collected, only 45 out of 400 respondents have ever sought information about genetics, either from healthcare professionals or other sources. Indonesia is ranked 60th out of 61 countries in the World's Most Literate Nations survey for 2017 in terms of literacy skills [20]. According to the Ministry of Education and Culture, data from the Indonesia National Assessment Program in 2016 showed that 46.83% of Indonesian students had low reading abilities, 6.06% had good reading abilities, and 47.11% had sufficient reading abilities [21]. The low literacy rate in Indonesia is a multifaceted issue that stems from several factors. One of the contributing factors is the inadequate emphasis on reading habits within the school system, which is further compounded by a scarcity of reading and information resources. Additionally, an unsupportive reading environment has also been identified as a crucial factor in the low literacy rate in Indonesia [22].

Notwithstanding, our findings indicated that the majority of non-medical and health students exhibited a favorable disposition toward genetic and premarital screening. This is a positive finding from a health perspective, as it suggests that the respondents understand and appreciate the importance of these screenings, as well as their potential advantages and disadvantages. However, this positive attitude does not necessarily translate into good behavior. The issue of privacy and stigmatization is a sensitive subject matter concerning premarital and genetic screening, particularly with regards to the results emanating from these evaluations. The society's stigma of individuals with disorders revealed through premarital and genetic screening can be especially prevalent in cases of hereditary illnesses [23].

In this study, the majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the results of genetic and premarital screenings should be shared with others, such as family members and partners, as indicated in the "openness of results" indicator. There is a need for more public education from the government about genetic and premarital screening, including Thalassemia screening [24]. The presence of healthcare professionals, such as doctors, who can provide education and information about genetics can also influence the decision to undergo premarital and genetic screening. According to Di Mattei et al. in 2018, effective counseling by healthcare workers about the benefits, risks, and processes involved in genetic screening can impact an individual's decision to undergo this type of screening. In addition to the availability of information, the cost of genetic screening can also be a factor that influences behavior. The high cost of these tests may make them unaffordable for some people [25]. The lack of facilities and the high cost of genetic screening services have hindered the optimal implementation of premarital and genetic screening programs to support public health.

Out of 400 respondents, 355 (88.75%) had bad or poor behaviors toward screening. This behavior could indicate a lack of support for premarital screening programs. The statistical association between knowledge and behaviors toward premarital and genetic screening did not attain significance. Typically, insufficient knowledge of scientific concepts can lead to unfavorable attitudes and conducts toward scientific technologies. Thus, if society has a more comprehensive knowledge of science, including genetics, it may harbor a more positive attitude and exhibit more favorable behavior toward technological advancements and their implementation [26]. However, there may be other factors that influence an individual's behavior toward premarital and genetic screening. In some cases, societies with greater knowledge may be more critical of genetic testing, including premarital screening [27]. Further research has produced consistent findings suggesting that more informed societies may exhibit more discrimination and a critical attitude toward certain science-related issues, particularly those with social or moral implications, which are commonly highlighted in the field of genetics [28].

According to theories of behavior formation, an individual's behavior is influenced by three groups of factors: predisposing factors, enabling factors, and reinforcing factors. Predisposing factors include knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values, and culture. Enabling factors include physical resources such as facilities and infrastructure. Reinforcing factors include the support of community leaders and healthcare professionals [29].

Premarital and genetic screening behaviors can also be influenced by the experiences and opinions of others. Healthcare professionals, particularly doctors, can play a vital role in shaping the public's understanding of complex genetic information and serve as a valuable source of guidance for individuals making decisions about genetic screening [30, 31]. Limited resources and facilities can also be a factor influencing behavior. In Indonesia, the availability of genetic screening facilities and the cost of these tests are not a priority for the government. Genetic screening facilities are only available in major cities and are not widely accessible throughout the country. As a result, the government has not established regulations and referral systems for patients with genetic disorders. This lack of access to care results in a high number of untreated genetic disease patients at the primary care level [32].

The study data corroborate previous research, indicating a correlation between attitudes and behaviors toward genetic screening. While attitudes and behaviors typically align, this is not always the case. A person's attitude is a crucial factor that influences decision-making. Although a child's favorable attitude toward health may not necessarily translate to positive behaviors, an unfavorable attitude toward health is likely to impede one's behavior [33]. According to the theory of planned behavior, a person's attitude toward a particular behavior is a subjective evaluation (positive or negative) based on their perception of the benefits and drawbacks of the behavior [34]. In general, the respondents in this study had a positive attitude toward genetic and premarital screening programs, but it is interesting to note that the majority of them had negative behaviors related to these programs. One indicator of behavior is the initiative of respondents to seek information about genetic and premarital screening, both through health workers and other sources.

In this study, most respondents indicated that they had never sought information about genetic and premarital screening programs. This is consistent with their general reluctance to actively seek out information, as most of the respondents held negative attitudes toward doing so. Nevertheless, despite their negative attitudes, the respondents still expressed support for these programs. Another noteworthy finding is that the majority of respondents reported never having undergone genetic or premarital screening. This could be due to a lack of information sources that raise awareness about the importance of these programs, as well as a lack of information from authorities, which may reduce respondents' willingness to participate. Another possible explanation for respondents' reluctance or lack of interest in these programs is that they are misinformed or indifferent. By examining how people behaved during the Covid-19 pandemic, health sector actors may be able to gain insights into the factors that influence individuals' behavior toward health programs [35, 36].

The results of this study have important implications for government officials in the development of healthcare policies. Specifically, these findings suggest that it is necessary to establish a comprehensive healthcare system that includes the proper implementation of premarital and genetic screening programs. Therefore, policymakers should take these findings into account when formulating health policies.

The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which imposed restrictions on various activities and learning practices. The study employed an online questionnaire, which allowed subjects to potentially cheat in answering the questions, particularly in terms of knowledge aspects. Future studies would benefit from gathering data during non-pandemic times and employing additional methods to ensure respondent accountability in answering the questions.

Conclusion

There is no relationship between the level of knowledge about genetics and the attitudes and behaviors toward premarital and genetic screening in non-medical and health students in Indonesia. However, there is a significant relationship between attitudes and behaviors toward genetic and premarital screening in these students.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the respondents who participated in this study, as well as to the Banyumas District Education Office for granting permission. This study was partially funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia.

Ethical Permission: The study has been approved by the ethical committee of Jenderal Soedirman University with number 017/KEPK/I/2021.

Conflict of Interests: Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in submitting and publishing this manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution: Baihaqi BS (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Hidayah AN (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Rujito L (Third Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer (35%)

Funding: This study was partially funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2023/02/7 | Accepted: 2023/03/9 | Published: 2023/05/22

Received: 2023/02/7 | Accepted: 2023/03/9 | Published: 2023/05/22

References

1. Idaiani S, Riyadi E. Sistem Kesehatan Jiwa di Indonesia: Tantangan untuk Memenuhi Kebutuhan. J Penelit dan Pengemb Pelayanan Kesehat. 2018;2(2 SE). [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.22435/jpppk.v2i2.134]

2. Widari S, Bachtiar N, Primayesa E. Faktor Penentu Stunting: Analisis Komparasi Masa Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) dan Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) di Indonesia. J Ilm Univ Batanghari Jambi. 2021;21(3):24. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.33087/jiubj.v21i3.1726]

3. Nawawi K, Lestari DW, Rujito L. Distribusi Pandangan Masyarakat Umum Terhadap Skrining Premarital di Banyumas. Mandala Heal. 2022;15(1):17-29. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.20884/1.mandala.2022.15.1.5743]

4. Rujito L, Mulyanto J. Adopting mass thalassemia prevention program in indonesia: a proposal. J Kedokt dan Kesehat Indones. 2019;10(1):1-4. [Link] [DOI:10.20885/JKKI.Vol10.Iss1.art1]

5. Alkalbani A, Alharrasi M, Achura S, Al Badi A, Al Rumhi A, Alqassabi K, et al. Factors Affecting the willingness to undertake premarital screening test among prospective marital individuals. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022;8:23779608221078156. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/23779608221078156]

6. Hiebert L, Hecht R, Soe-Lin S, Mohamed R, Shabaruddin FH, Syed Mansor SM, et al. A stepwise approach to a national hepatitis c screening strategy in Malaysia to meet the WHO 2030 targets: proposed strategy, coverage, and costs. Value Heal Reg issues. 2019;18:112-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vhri.2018.12.005]

7. Angastiniotis M, Petrou M, Loukopoulos D, Modell B, Farmakis D, Englezos P, et al. The prevention of thalassemia revisited: a historical and ethical perspective by the thalassemia international federation. Hemoglobin. 2021;45(1):5-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03630269.2021.1872612]

8. Hamed EM, Eshra DM, Qasem E, Khalil AK. Knowledge, perception, and attitude of future couples towards premarital screening. Menoufia Nurs J. 2022;7(2):1-21. [Link] [DOI:10.21608/menj.2022.254007]

9. Memish ZA, Saeedi MY. Six-year outcome of the national premarital screening and genetic counseling program for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(3):229-35. [Link] [DOI:10.5144/0256-4947.2011.229]

10. Haga SB, Kim E, Myers RA, Ginsburg GS. Primary care physicians' knowledge, attitudes, and experience with personal genetic testing. J Pers Med. 2019;9(2):29. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jpm9020029]

11. Alkhaldi SM, Khatatbeh MM, Berggren VEM, Taha HA. Knowledge and attitudes toward mandatory premarital screening among university students in North Jordan. Hemoglobin. 2016;40(2):118-24. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/03630269.2015.1135159]

12. Keandre N, Rujito L, Munfiah S. Knowledge, attitude, and behavior in genetic and premarital screening among medical and health students in Banyumas Regency. Med Heal J. 2021;1(1):22-31. [Link] [DOI:10.20884/1.mhj.2021.1.1.4670]

13. Khdair SI, Al-Qerem W, Jarrar W. Knowledge and attitudes regarding genetic testing among Jordanians: An approach towards genomic medicine. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(7):3989-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.04.004]

14. Abrams LR, McBride CM, Hooker GW, Cappella JN, Koehly LM. The many facets of genetic literacy: assessing the scalability of multiple measures for broad use in survey research. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141532. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0141532]

15. Rahma AT, Elsheik M, Elbarazi I, Ali BR, Patrinos GP, Kazim MA, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of medical and health science students in the United Arab Emirates toward genomic medicine and pharmacogenomics: a cross-sectional study. J Pers Med. 2020;10(4):191. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jpm10040191]

16. Horton B, Bridle H, Alexander CL, Katzer F. Giardia duodenalis in the UK: current knowledge of risk factors and public health implications. Parasitology. 2019;146(4):413-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0031182018001683]

17. Yli-Panula E, Jeronen E, Lemmetty P, Pauna A. Teaching methods in biology promoting biodiversity education. Sustainability. 2018;10(10):3812. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/su10103812]

18. Tognetto A, Michelazzo MB, Ricciardi W, Federici A, Boccia S. Core competencies in genetics for healthcare professionals: results from a literature review and a Delphi method. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):19. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-019-1456-7]

19. Ezechi NG. The problems of teaching and learning genetics in secondary schools in Enugu South local government area of Enugu State. Br Int J Educ Soc Sci. 2021;8(4 SE):13-9. [Link]

20. World Atlas. List of countries by literacy rate [Internet]. World Atlas; 2022 [cited 2022 July 21]. Available from: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-highest-literacy-rates-in-the-world.html [Link]

21. Tahmidaten L, Krismanto W. Permasalahan Budaya Membaca di Indonesia (Studi Pustaka Tentang Problematika & Solusinya). J Pendidik dan Kebud. 2020;10(1):22-33. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.24246/j.js.2020.v10.i1.p22-33]

22. Akbar A. Membudayakan Literasi Dengan Program 6M di Sekolah Dasar. J Pendidik Sekol Dasar. 2017;3(1):42. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.30870/jpsd.v3i1.1093]

23. Boardman FK, Clark C, Jungkurth E, Young PJ. Social and cultural influences on genetic screening programme acceptability: A mixed-methods study of the views of adults, carriers, and family members living with thalassemia in the UK. J Genet Couns. 2020;29(6):1026-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jgc4.1231]

24. Jaka P De, Lestari DW, Rujito L. Perception of prospective couples in Banyumas towards thalassemia screening: a qualitative study. Bul Penelit Kesehat. 2019;47(2 SE). [Link] [DOI:10.22435/bpk.v47i2.1261]

25. Di Mattei VE, Carnelli L, Bernardi M, Bienati R, Brombin C, Cugnata F, et al. Coping mechanisms, psychological distress, and quality of life prior to cancer genetic counseling. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1218. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01218]

26. Saylor KW, Ekunwe L, Antoine-LaVigne D, Sellers DE, McGraw S, Levy D, et al. Attitudes toward genetics and genetic testing among participants in the Jackson and Framingham Heart Studies. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(3):262-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1556264619844851]

27. Cheung R, Jolly S, Vimal M, Kim HL, McGonigle I. Who's afraid of genetic tests?: An assessment of Singapore's public attitudes and changes in attitudes after taking a genetic test. BMC Med Ethics. 2022;23(1):5. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12910-022-00744-5]

28. Kim H, Ho CWL, Ho CH, Athira PS, Kato K, De Castro L, et al. Genetic discrimination: introducing the Asian perspective to the debate. NPJ Genomic Med. 2021;6(1):54. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41525-021-00218-4]

29. Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1998;28(15):1429-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x]

30. Bener A, Al-Mulla M, Clarke A. Premarital screening and genetic counseling program: Studies from an Endogamous Population. Int J Appl basic Med Res. 2019;9(1):20-6. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijabmr.IJABMR_42_18]

31. Zhong A, Darren B, Dimaras H. Ethical, social, and cultural issues related to clinical genetic testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):140. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13643-017-0535-2]

32. Nurhendriyana H, Brajadenta GS. Pengembangan Layanan Diagnosis Genomics di Bidang Kesehatan Reproduksi. Tunas Med J Kedokt Kesehat. 2019;5(2):6-8. [Indonesian] [Link]

33. Botoseneanu A, Alexander JA, Banaszak-Holl J. To test or not to test? The role of attitudes, knowledge, and religious involvement among U.S. adults on intent-to-obtain adult genetic testing. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(6):617-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1090198110389711]

34. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2020;2(4):314-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/hbe2.195]

35. Reed-Weston AE, Espinal A, Hasar B, Chiuzan C, Lazarin G, Weng C, et al. Choices, attitudes, and experiences of genetic screening in Latino/a and Ashkenazi Jewish individuals. J Community Genet. 2020;11(4):391-403. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12687-020-00464-6]

36. Luthfiyana NU, Putri SI, Halu SAN. Perilaku Mahasiswa Kesehatan dalam Memberikan Edukasi Pencegahan COVID-19 kepada Masyarakat. Wind Health. 2022;5(2):501-10. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.33096/woh.v5i02.10]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |