Volume 10, Issue 1 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(1): 33-41 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Behforouz A, Razeghi S, Shamshiri A, Mohebbi S. General and Dental COVID-19-related Knowledge of Iranian Dental Academics; a Cross-Sectional Online Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (1) :33-41

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-54149-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-54149-en.html

1- Dental Students’ Scientific Research Center, School of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Research Center for Caries Prevention, Dentistry Research Institute” and “Department of Community Oral Health, School of Dentistry”, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Research Center for Caries Prevention, Dentistry Research Institute” and “Department of Community Oral Health, School of Dentistry”, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: COVID-19 [MeSH], Pandemics [MeSH], Dental Faculty [MeSH], Dentists [MeSH], Knowledge [MeSH], Awareness [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 524 kb]

(3463 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2517 Views)

Full-Text: (702 Views)

Introduction

China reported the outbreak of an emerging viral infection named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in December 2019, and since then, it has quickly reached the state of a pandemic [1, 2]. As of July 17th, 2021, about 190 million COVID-19 cases and 4.1 million related deaths have occurred [3]. To date, there is no approved antiviral treatment for COVID-19, so COVID-19 management has been largely supportive [4]. Although, vaccines have recently received permission for use [5].

Dentists are the highest-risk healthcare workers (HCWs) at risk for COVID-19 contraction [6]. This is due to the number of patients they come in contact with per day and the aerosol-generating procedures that they perform at very short distances from patients [7]. Dental students and academics are also highly vulnerable to infection during education and training. Dental offices may also play a role in cross-contamination between patients.

World Health Organization (WHO) [4], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [8], and American Dental Association (ADA) [9] have published guidelines for dental staff to control the transmission of COVID-19. Waiting and treatment room hygiene, tele/online patient evaluation, hand washing, antibacterial mouthwash before dental procedures, personal protective equipment (PPE), reduction of aerosol production, rubber dam utilization, anti-retraction handpieces, high volume saliva ejectors, disposable devices, and extra-oral imaging are among these recommendations. Also, some of the guidelines provide useful information on the transmission pathways, disease signs and symptoms, and referral mechanisms to increase dental staff knowledge to control the disease at the population level [4, 10].

Limited infection control materials and poor knowledge of transmission were reported as major barriers to infection control in the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. Knowledge of disease can affect HCWs’ attitudes and practices, and misguided attitudes and practices directly increase the risk of infection. Dentists were also reported to have limited knowledge of some preventive measures [12]. Moreover, as a result of another study, a targeted continued professional education was recommended to avert specific knowledge gaps in HCWs [13]. Despite all said, dental academics of Ammar et al.’s international study [14] correctly answered 73.2% of the COVID-19-related knowledge questions on average.

In addition to their clinical role in the practice as a dentist, dental academics have an important role in the education and training of dentists and dental students. Therefore, their knowledge is critical for better infection control by themselves and other dentists and increasing awareness among their students and patients. Evidence on COVID-19 related knowledge among dental academics is not much. Identifying topics about which Iranian dental academic knowledge is undesirable can help tackle them through effective policies, training, and education [13]. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge of Iranian dental academics regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and identify the associating factors.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted online in April 2020 in the dental school of Tehran University of Medical Sciences as a part of a multinational study [14]. The study consisted of all dental academics of all 36 dental schools of Iran (N=1826) [15]. The inclusion criterion was working as a faculty member in dental schools. Quadri et al. [16] reported a standard deviation (SD) of 1.39 for a knowledge score out of 17, equivalent to an SD of 8.18 for the present study’s knowledge score of 100. We considered α to be 0.05 and margin of error (MOE) to be 1 point and calculated a minimum sample size of 226 using the following formula:

n=N × (Zα/22 × σ2 / MOE2) / (N + Zα/22 × σ2 / MOE2 – 1)

First, we used the convenient sampling method. We shared the survey link on social media (WhatsApp, Telegram) groups and channels that only dental academics were present. It was also sent to the dental academics on the contact list of the authors through e-mail or social media. Along with the link was a brief description of the current study and the approximate completion time of 10 minutes, and dental academics were asked to complete it. We also asked them to share the survey with dental academics they knew and, in other words, used snowball sampling as well. A reminder was sent one week after the invitation to maximize the response rate. The survey was open from April 8th to April 21st, 2020.

The questionnaire of the study was originally developed by an international team [14] according to CDC [17, 18], WHO [19, 20], and Meng et al. [10], and it consisted of two sections:

China reported the outbreak of an emerging viral infection named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in December 2019, and since then, it has quickly reached the state of a pandemic [1, 2]. As of July 17th, 2021, about 190 million COVID-19 cases and 4.1 million related deaths have occurred [3]. To date, there is no approved antiviral treatment for COVID-19, so COVID-19 management has been largely supportive [4]. Although, vaccines have recently received permission for use [5].

Dentists are the highest-risk healthcare workers (HCWs) at risk for COVID-19 contraction [6]. This is due to the number of patients they come in contact with per day and the aerosol-generating procedures that they perform at very short distances from patients [7]. Dental students and academics are also highly vulnerable to infection during education and training. Dental offices may also play a role in cross-contamination between patients.

World Health Organization (WHO) [4], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [8], and American Dental Association (ADA) [9] have published guidelines for dental staff to control the transmission of COVID-19. Waiting and treatment room hygiene, tele/online patient evaluation, hand washing, antibacterial mouthwash before dental procedures, personal protective equipment (PPE), reduction of aerosol production, rubber dam utilization, anti-retraction handpieces, high volume saliva ejectors, disposable devices, and extra-oral imaging are among these recommendations. Also, some of the guidelines provide useful information on the transmission pathways, disease signs and symptoms, and referral mechanisms to increase dental staff knowledge to control the disease at the population level [4, 10].

Limited infection control materials and poor knowledge of transmission were reported as major barriers to infection control in the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. Knowledge of disease can affect HCWs’ attitudes and practices, and misguided attitudes and practices directly increase the risk of infection. Dentists were also reported to have limited knowledge of some preventive measures [12]. Moreover, as a result of another study, a targeted continued professional education was recommended to avert specific knowledge gaps in HCWs [13]. Despite all said, dental academics of Ammar et al.’s international study [14] correctly answered 73.2% of the COVID-19-related knowledge questions on average.

In addition to their clinical role in the practice as a dentist, dental academics have an important role in the education and training of dentists and dental students. Therefore, their knowledge is critical for better infection control by themselves and other dentists and increasing awareness among their students and patients. Evidence on COVID-19 related knowledge among dental academics is not much. Identifying topics about which Iranian dental academic knowledge is undesirable can help tackle them through effective policies, training, and education [13]. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge of Iranian dental academics regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and identify the associating factors.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted online in April 2020 in the dental school of Tehran University of Medical Sciences as a part of a multinational study [14]. The study consisted of all dental academics of all 36 dental schools of Iran (N=1826) [15]. The inclusion criterion was working as a faculty member in dental schools. Quadri et al. [16] reported a standard deviation (SD) of 1.39 for a knowledge score out of 17, equivalent to an SD of 8.18 for the present study’s knowledge score of 100. We considered α to be 0.05 and margin of error (MOE) to be 1 point and calculated a minimum sample size of 226 using the following formula:

n=N × (Zα/22 × σ2 / MOE2) / (N + Zα/22 × σ2 / MOE2 – 1)

First, we used the convenient sampling method. We shared the survey link on social media (WhatsApp, Telegram) groups and channels that only dental academics were present. It was also sent to the dental academics on the contact list of the authors through e-mail or social media. Along with the link was a brief description of the current study and the approximate completion time of 10 minutes, and dental academics were asked to complete it. We also asked them to share the survey with dental academics they knew and, in other words, used snowball sampling as well. A reminder was sent one week after the invitation to maximize the response rate. The survey was open from April 8th to April 21st, 2020.

The questionnaire of the study was originally developed by an international team [14] according to CDC [17, 18], WHO [19, 20], and Meng et al. [10], and it consisted of two sections:

- Background information (nine items): Participants’ gender, age, living status, specialty, academic experience, number of daily patient visits, number of courses coordinating per semester, number of students dealing with per semester, and administrative role.

- Knowledge (six main questions): Participants' knowledge of COVID-19 transmission pathways, warning signs which call for emergency treatment, methods of diagnosis, treatment guidelines, related protection, and dental precautions that should be considered while providing dental treatment for COVID-19 suspected/infected patients.

Each of the six questions in the knowledge section presented a separate domain of COVID-19 knowledge. Options listed under each question were a true or a false statement. These domains were transmission (six items), warning signs (four items), treatment (five items), diagnosis (four items), protection (five items), and dental precautions (five items). The questionnaire was translated into Persian and back-translated into English to check the translation quality. To ensure the face and content validity of the questionnaire, two community oral health, one oral and maxillofacial surgery, one pediatric dentistry academics, and one epidemiologist reviewed and commented on it, and we revised the questionnaire accordingly. Content Validity Indices (CVIs) were at least 0.7, and Content Validity Ratios (CVRs) were more than 0.95. Finally, the pilot study was conducted among ten dental academics twice fortnightly to assess the reliability of the questions (actual agreement >0.9 for all questions).

The study was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethics committee. The survey was fully confidential, and it was voluntary to participate. The online survey was certainly the choice because of the pandemic condition, and the survey was uploaded on Google Forms (link: https://forms.gle/MHB2G23ZqMPiE6Ex7). We modified the settings so that the responders’ details were not asked and their answers could not be traced. This feature, alongside statements addressing the voluntary participation and objectives of the study, was mentioned on the first page of the survey to ensure the participants of a confidential study. Participants implied the consent to participate in the study by responding to the survey after reading the first page. Submission of the survey required answers to all the questions.

We downloaded all the responses from Google Forms in a Microsoft Excel 2013 file. After coding and cleaning the data, they were transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 for windows [21], and this software was used for further statistical tests. The percentage of the correct answers to the items in each domain of COVID-19 knowledge is considered the domain’s score for each respondent. Also, the percentage of total correct answers to the items in the knowledge section (out of 29 items) is considered the total knowledge score for each respondent. As answering all the questions were required to submit the survey, there would be no missing data from the participants. We performed backward stepwise multilevel linear regression to assess the association of background factors with knowledge domains and total scores. We set the level of significance at 5%.

Findings

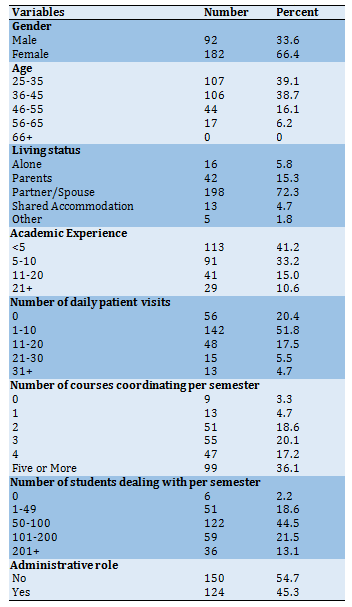

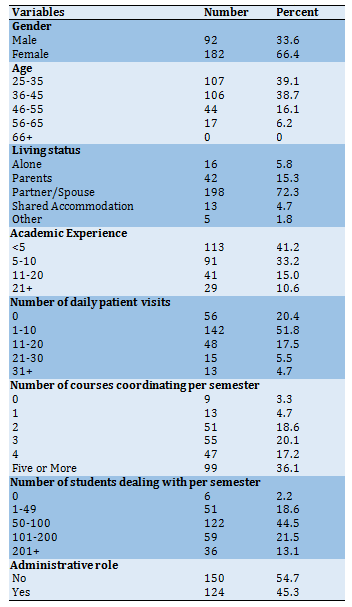

A total of 274 respondents completed the survey. The majority of the participants were female (182 cases) under 46 years (213 cases) and lived with their partner/spouse (198 cases; Table 1).

Table 1) Background characteristics of the dental academics attending COVID-19 knowledge survey in Iran (N=274)

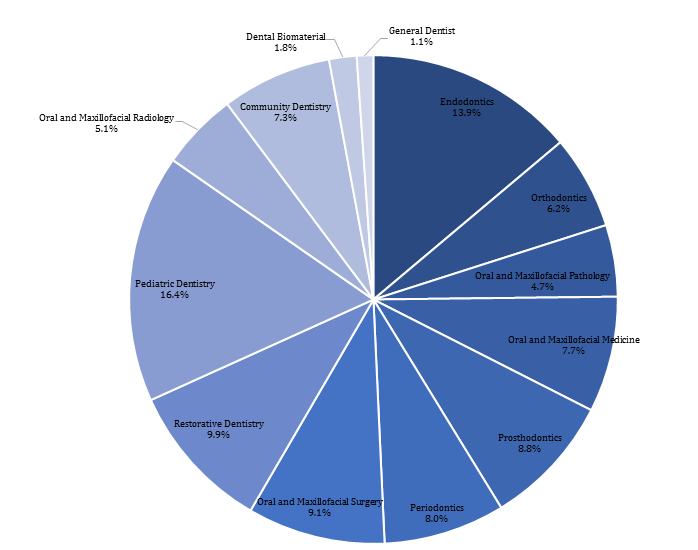

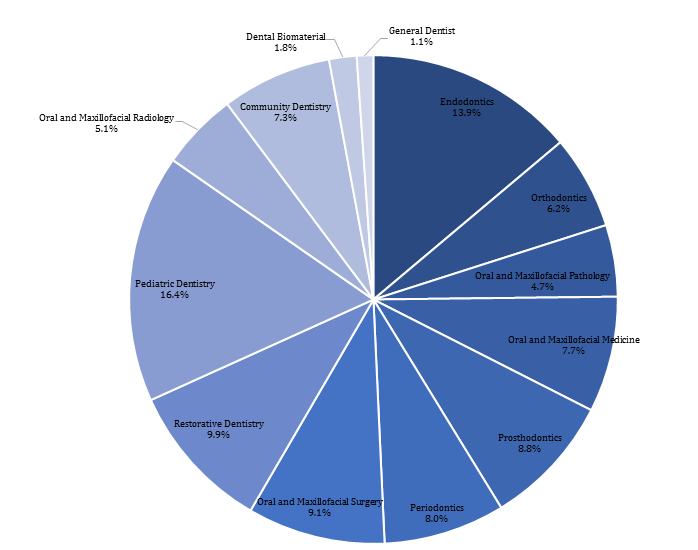

According to Iran’s postgraduate education in dentistry, the specialty was shown in Diagram 1.

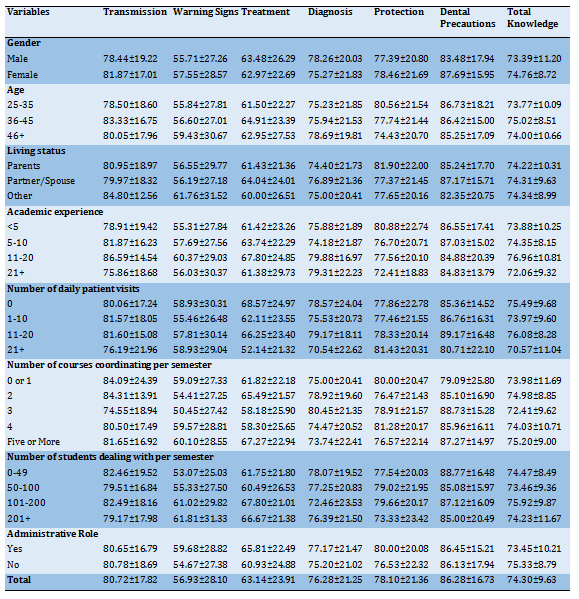

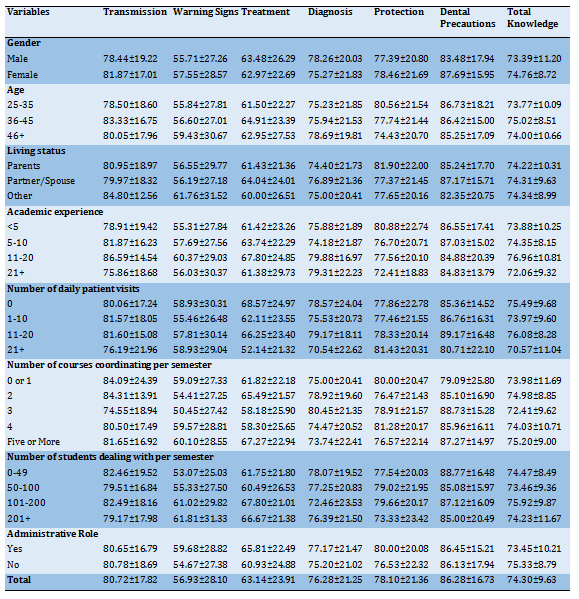

The scores of knowledge domains of dental academics considering background variables were presented in Table 2. The mean for the COVID-19 knowledge total score was 74.30±9.63, with dental precautions having the highest domain score (86.28±16.73) and warning signs having the lowest domain score (56.93±28.10).

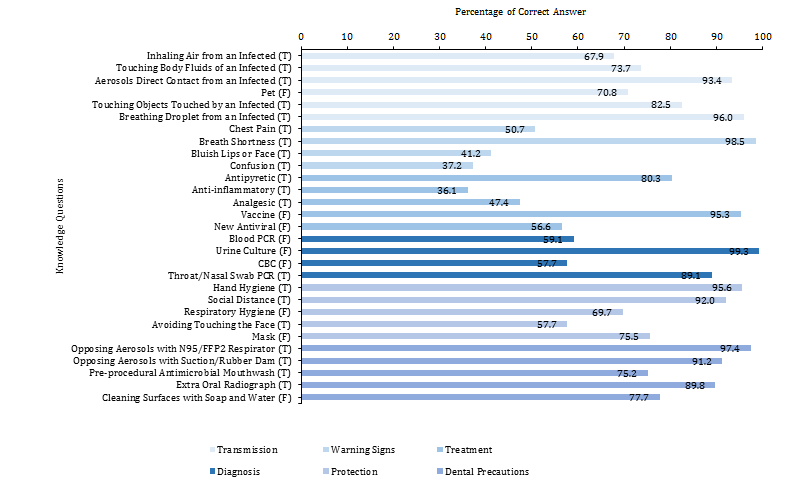

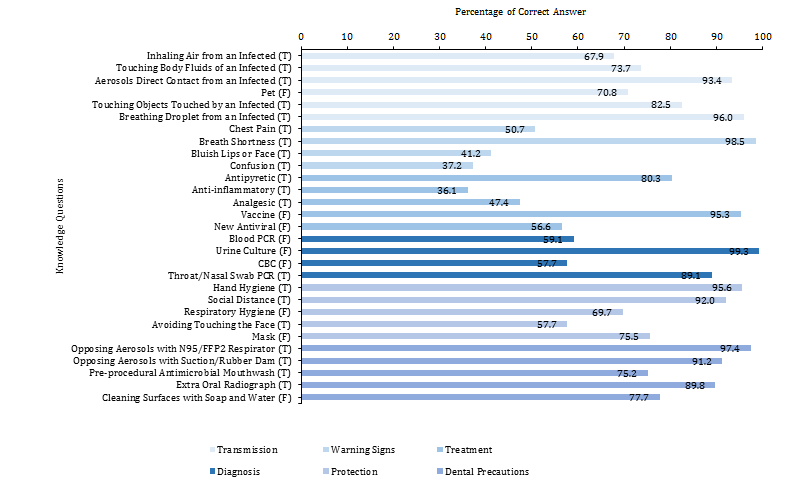

Percentages of the correct answers to all of the items in the knowledge section are evident in Diagram 2. In the transmission domain (question: Which of the following can transmit COVID-19 virus to compromised skin or mucous membranes?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “breathing droplets exhaled or coughed from an infected” (96.0%) and “inhaling air from an infected” (67.9%). In the warning signs domain (question: Which of the following are major emergency warning signs in patients with COVID-19 infection that require immediate medical attention?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “breath shortness” (98.5%) and “confusion” (37.2%). In the treatment domain (question: Which of the following is used to treat COVID-19 infection?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “vaccine” (95.3%) and “anti-inflammatory” (36.1%). In the diagnosis domain (question: Which of the following methods is used to diagnose COVID-19?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “urine culture” (99.3%) and “complete blood count (CBC)” (57.7%). In the protection domain (question: Which of these are the three best methods to protect against infection?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “hand hygiene” (95.6%) and “avoiding touching the face” (57.7%). In the dental precautions domain (question: According to the WHO guidelines, in case of patients infected with/suspected of COVID-19 infection, which of the following should be done during dental treatment?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “opposing aerosols with N95/FFP2 (filter facepiece 2) respirator” (97.4%) and “pre-procedural antimicrobial mouthwash” (75.2%). Among all the items in the knowledge section, the most and least correctly answered items were respectively “urine culture” in the diagnosis domain (99.3%) and “anti-inflammatory” in the treatment domain (36.1%).

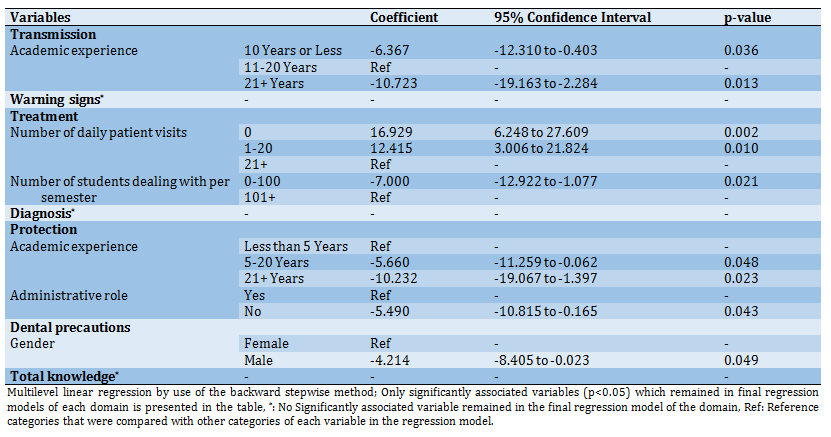

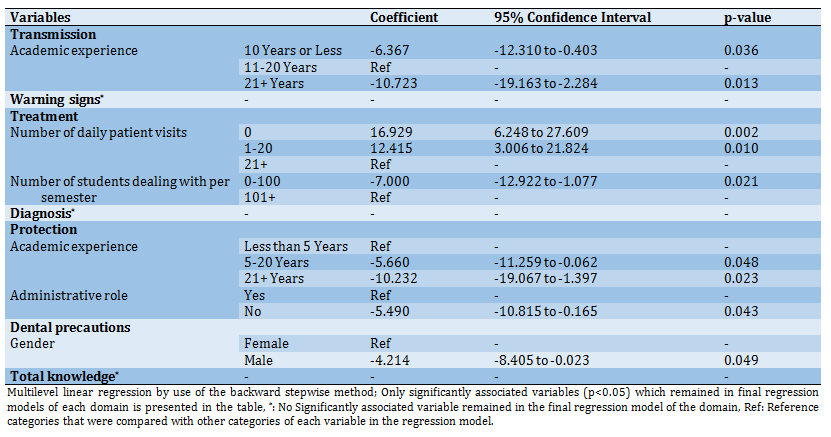

Table 3 reveals background data associated with COVID-19 knowledge in dental academics attending the survey by domains and in total. Dental academics with 11 to 20 years of academic experience had significantly more knowledge about COVID-19 transmission. Those with the academic experience of fewer than five years had significantly more knowledge about protection against COVID-19 than others. In addition, those who visited more than 20 patients daily and dealt with 100 students or less per semester had significantly less knowledge about COVID-19 treatment than other participants did. Furthermore, participants with administrative roles had more knowledge about protection against COVID-19, and men had less knowledge of dental precautions against COVID-19. No background variable was associated with these knowledge domains regarding the warning signs and diagnosis. Likewise, no association existed between the background information and the total knowledge score.

Diagram 1) Specialty of Iranian dental academics attending COVID-19 knowledge survey (N=274)

Table 2) The COVID-19 knowledge scores of dental academics in Iran (N=274)

Diagram 2) Rate of correct responses (T: True; F: False) to COVID-19 knowledge questions by Iranian dental academics (N=274).

Table 3) Background characteristics associated with Iranian dental academics’ COVID-19 knowledge (N=274)

Discussion

Iran was one of the first group of countries to be involved in the pandemic and first reported Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) infection on February 19th, 2020 [22], and is one of the countries with the most number of cases and deaths due to the virus. Dentists are at the highest risk of COVID-19 contraction [6], and poor knowledge is a major barrier to infection control in the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. With regards to the wide communication network and role of academics in education and training of the dentists, dental students, and community, their good knowledge will result in better preparedness of dental team in practice, patients’ protection, and fulfillment of public responsibility as a group of people who are looked up to.

An overall knowledge score of 74.30 in the present study is a relatively good score, and it shows that dental academics are knowledgeable on the COVID-19 topic. In two similar studies, one international [23] and one from India [24], good knowledge scores were significantly associated with the higher academic degree of the dentists, showing the impact of education; and in the latter [24], dentists working as academics alongside their private practice had more knowledge about COVID-19. However, this study was conducted only on academics, and only 1.1% of the participants were general dentists. Therefore no such comparisons could be made. Furthermore, dental health professionals consisting of students, auxiliaries, and practitioners are aware of the droplet and airborne isolation precautions. This knowledge was more present in females, postgraduates, more experienced, and governmentally occupied [25]. Studies on Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) [25] and COVID-19 [23] have shown that there is a positive linear association between good knowledge and practice scores in clinical management and prevention during pandemics. Almost all dentists believe educating others on COVID-19 is important [12, 23, 26], which emphasizes the crucial role of academic people in the community awareness regarding the pandemic.

Knowledge about COVID-19 transmission is crucial for dental staff as the dental setting is a high-risk environment; fortunately, the score for this domain was quite good (80.72) in the present study. The important point is to inform the dentists that inhaling air exhaled by an infected person is similar to breathing droplets, as some participants were unaware of it. Dentists participating in other studies have also shown desirable knowledge of transmission routes [12, 23, 24, 26, 27]. Nevertheless, dentists lack awareness of the COVID-19 incubation period of 1 to 14 days [12, 16], which disturbs their justification for a safe period to treat suspected patients. In the present study, academics with moderate experience of 11 to 20 years were more knowledgeable on this topic than less and more experienced ones. This is probably because they are of higher academic degree and their work hours are less than juniors so that they may have time to update themselves on COVID-19, while their concerns to infection control are greater than the older ones.

It’s crucial for dentists to know the warning signs of COVID-19, while such knowledge was insufficient among the dental academics of our study (56.93). Almost all the respondents recognized breath-shortness as a warning sign, but many of them did not know that chest pain, bluish lips or face, and new onset of confusion or inability to arouse are also warning signs. However, dentists are shown to be aware of the main symptoms of COVID-19 and the possibility of being asymptomatic, which is essential in the management and control of the disease [10, 12, 23, 24, 26].

Dental academics who participated in the present study had moderate and acceptable knowledge scores in treatment (63.14) and diagnosis (76.28) domains of COVID-19 knowledge. This seems to be sufficient as they are not considered the first-line professionals in the field. It has been shown that dental health care workers have moderate knowledge of the ineffectiveness of antibiotics for the treatment of COVID-19 [16]. According to Wang et al. [28] and Meng et al. [10], the approach to COVID-19 is to prevent the infection, reduce the risk of transmission, early diagnosis, and encourage quarantine on suspected or infected patients. Dentists are mostly aware of these approaches [24, 26]. Some of the present study’s participants didn’t know that no antiviral existed to treat COVID-19. Some were unaware of anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics usage alongside antipyretics to directly alleviate disease symptoms.

Dental academics visiting more than 20 patients daily had less knowledge about COVID-19 treatment, mainly because they are overtly engaged in their practice and have less time to gather information. In addition, dental academics dealing with less than 100 students per semester had less knowledge about treatment. This is probably due to less time in the academic environment, less contact with fellow knowledgeable academics, and less sense of duty due to fewer students.

Dentists should be aware that they could be carriers and transmit the disease to their patients. Hopefully, participants of this study had fairly good knowledge about general protection against COVID-19 (78.10), and it is expected that they protect themselves from the virus and ultimately protect their patients. As newer concepts on protection against infectious diseases, less experienced and younger academics were more knowledgeable. Also, those who had administrative roles had more knowledge about protection against COVID-19; this may be due to their sense of duty and attitude of being a role model for fellow academics.

Our study’s knowledge about dental precautions was relatively high (86.28) , which is a good sign revealing that most dental academics were informed about the guidelines. Nevertheless, some of them had little knowledge of the usefulness of pre-procedural mouth rinsing. It’s good to mention that female academics were more knowledgeable on dental precautions against COVID-19, which is in accordance with another study that reported that females, postgraduates, more experienced, and governmentally occupied dental health professionals are more knowledgeable in droplet and airborne isolation precautions [25]. However, in

Althomairy et al. study on MERS [29], females, PhD (doctor of philosophy) degree holders, and dentists working in private sectors showed better attitudes about needing additional precautions while performing AGPs.

In Khader et al. study [12], cleaning hands with alcohol-based hand rubs or soap and water, disinfecting surfaces, using PPE, and using ventilated rooms were also well known by the dentists. In contrast, Gambhir et al. [24] showed that one-third of the Indian dentists were not aware of mandatory PPE, probably showing the effect of regional health policies. Despite most of the dentists in Ahmed et al. study [27] recommended using N95 masks and universal precautions of infection control for dental procedures, most of them didn’t apply N95 masks, rubber dams, or pre-procedural antimicrobial mouthwash, and a lot of them didn’t use high-volume suction. It seems that good knowledge in this domain is insufficient, and it should become apparent in practice.

The major strength of the present study is the use of a valid and reliable international questionnaire which facilitates the between-country comparisons in the future. Moreover, multiple regression models were applied to control all the factors and discover the more associated ones. We initially looked for the independent variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in the simple linear regression with various knowledge domains and total scores acting as the dependent variable separately. Then we used multiple linear regression models for each domain and total score separately with their associated variables from the previous stage. Then we eliminated variables one by one using backward stepwise method to reach the best possible model.

This study had some limitations too. The survey link was sent to several dental academics by different possible routes to decrease the selection bias of online surveys with convenient sampling; nevertheless, self-selection bias could have occurred and influenced the results. Furthermore, female and younger dental academics were more eager to complete this survey. Unlike Kharma et al. [30], who interpreted this as these groups being more concerned with disease outbreaks, we think this may be due to more time spent online and on social media by these groups.

To encounter the inevitable limitations of the representativeness of online surveys, we tried to send the questionnaire’s link through all possible social media groups and academic emails, as well as sending reminders. Despite all said, we think that the present study’s sample was representative of the target population of Iranian dental academics and large enough to conduct the required statistical analysis. Nevertheless, generalization to other countries' dental academics or all dentists in Iran must be avoided. Finally, changes in knowledge through time are ignored due to the study’s cross-sectional nature, and no cause-effect relationship is reachable.

We suggest the study be implemented in a larger population with a more robust sampling methodology so that the results might be more generalizable. Extensive educational programs should be continued and updated to improve the knowledge of dental academics as they serve as an important source of information for students, dentists, and patients.

Conclusion

Dental academics have an overall desirable knowledge about COVID-19. Knowledge about transmission, protection, and dental precautions is good, and knowledge about treatment and diagnosis is moderate but acceptable. The lowest domain score is for the warning signs.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to all dental academics for responding to the study questionnaire. We also thank Dr. Mahsa Karimi for the back-translation of the questionnaire.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (approval ID: IR.TUMS.DENTISTRY.REC.1399.001).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose, and the funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution: Behforouz A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (30%); Razeghi S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/

Discussion Writer (20%); Shamshiri AR (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Mohebbi SZ (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist

/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: The study was funded by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 99-3-234-50465).

The study was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethics committee. The survey was fully confidential, and it was voluntary to participate. The online survey was certainly the choice because of the pandemic condition, and the survey was uploaded on Google Forms (link: https://forms.gle/MHB2G23ZqMPiE6Ex7). We modified the settings so that the responders’ details were not asked and their answers could not be traced. This feature, alongside statements addressing the voluntary participation and objectives of the study, was mentioned on the first page of the survey to ensure the participants of a confidential study. Participants implied the consent to participate in the study by responding to the survey after reading the first page. Submission of the survey required answers to all the questions.

We downloaded all the responses from Google Forms in a Microsoft Excel 2013 file. After coding and cleaning the data, they were transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 for windows [21], and this software was used for further statistical tests. The percentage of the correct answers to the items in each domain of COVID-19 knowledge is considered the domain’s score for each respondent. Also, the percentage of total correct answers to the items in the knowledge section (out of 29 items) is considered the total knowledge score for each respondent. As answering all the questions were required to submit the survey, there would be no missing data from the participants. We performed backward stepwise multilevel linear regression to assess the association of background factors with knowledge domains and total scores. We set the level of significance at 5%.

Findings

A total of 274 respondents completed the survey. The majority of the participants were female (182 cases) under 46 years (213 cases) and lived with their partner/spouse (198 cases; Table 1).

Table 1) Background characteristics of the dental academics attending COVID-19 knowledge survey in Iran (N=274)

According to Iran’s postgraduate education in dentistry, the specialty was shown in Diagram 1.

The scores of knowledge domains of dental academics considering background variables were presented in Table 2. The mean for the COVID-19 knowledge total score was 74.30±9.63, with dental precautions having the highest domain score (86.28±16.73) and warning signs having the lowest domain score (56.93±28.10).

Percentages of the correct answers to all of the items in the knowledge section are evident in Diagram 2. In the transmission domain (question: Which of the following can transmit COVID-19 virus to compromised skin or mucous membranes?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “breathing droplets exhaled or coughed from an infected” (96.0%) and “inhaling air from an infected” (67.9%). In the warning signs domain (question: Which of the following are major emergency warning signs in patients with COVID-19 infection that require immediate medical attention?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “breath shortness” (98.5%) and “confusion” (37.2%). In the treatment domain (question: Which of the following is used to treat COVID-19 infection?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “vaccine” (95.3%) and “anti-inflammatory” (36.1%). In the diagnosis domain (question: Which of the following methods is used to diagnose COVID-19?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “urine culture” (99.3%) and “complete blood count (CBC)” (57.7%). In the protection domain (question: Which of these are the three best methods to protect against infection?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “hand hygiene” (95.6%) and “avoiding touching the face” (57.7%). In the dental precautions domain (question: According to the WHO guidelines, in case of patients infected with/suspected of COVID-19 infection, which of the following should be done during dental treatment?), the most and the least correctly answered items were respectively “opposing aerosols with N95/FFP2 (filter facepiece 2) respirator” (97.4%) and “pre-procedural antimicrobial mouthwash” (75.2%). Among all the items in the knowledge section, the most and least correctly answered items were respectively “urine culture” in the diagnosis domain (99.3%) and “anti-inflammatory” in the treatment domain (36.1%).

Table 3 reveals background data associated with COVID-19 knowledge in dental academics attending the survey by domains and in total. Dental academics with 11 to 20 years of academic experience had significantly more knowledge about COVID-19 transmission. Those with the academic experience of fewer than five years had significantly more knowledge about protection against COVID-19 than others. In addition, those who visited more than 20 patients daily and dealt with 100 students or less per semester had significantly less knowledge about COVID-19 treatment than other participants did. Furthermore, participants with administrative roles had more knowledge about protection against COVID-19, and men had less knowledge of dental precautions against COVID-19. No background variable was associated with these knowledge domains regarding the warning signs and diagnosis. Likewise, no association existed between the background information and the total knowledge score.

Diagram 1) Specialty of Iranian dental academics attending COVID-19 knowledge survey (N=274)

Table 2) The COVID-19 knowledge scores of dental academics in Iran (N=274)

Diagram 2) Rate of correct responses (T: True; F: False) to COVID-19 knowledge questions by Iranian dental academics (N=274).

Table 3) Background characteristics associated with Iranian dental academics’ COVID-19 knowledge (N=274)

Discussion

Iran was one of the first group of countries to be involved in the pandemic and first reported Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) infection on February 19th, 2020 [22], and is one of the countries with the most number of cases and deaths due to the virus. Dentists are at the highest risk of COVID-19 contraction [6], and poor knowledge is a major barrier to infection control in the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. With regards to the wide communication network and role of academics in education and training of the dentists, dental students, and community, their good knowledge will result in better preparedness of dental team in practice, patients’ protection, and fulfillment of public responsibility as a group of people who are looked up to.

An overall knowledge score of 74.30 in the present study is a relatively good score, and it shows that dental academics are knowledgeable on the COVID-19 topic. In two similar studies, one international [23] and one from India [24], good knowledge scores were significantly associated with the higher academic degree of the dentists, showing the impact of education; and in the latter [24], dentists working as academics alongside their private practice had more knowledge about COVID-19. However, this study was conducted only on academics, and only 1.1% of the participants were general dentists. Therefore no such comparisons could be made. Furthermore, dental health professionals consisting of students, auxiliaries, and practitioners are aware of the droplet and airborne isolation precautions. This knowledge was more present in females, postgraduates, more experienced, and governmentally occupied [25]. Studies on Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) [25] and COVID-19 [23] have shown that there is a positive linear association between good knowledge and practice scores in clinical management and prevention during pandemics. Almost all dentists believe educating others on COVID-19 is important [12, 23, 26], which emphasizes the crucial role of academic people in the community awareness regarding the pandemic.

Knowledge about COVID-19 transmission is crucial for dental staff as the dental setting is a high-risk environment; fortunately, the score for this domain was quite good (80.72) in the present study. The important point is to inform the dentists that inhaling air exhaled by an infected person is similar to breathing droplets, as some participants were unaware of it. Dentists participating in other studies have also shown desirable knowledge of transmission routes [12, 23, 24, 26, 27]. Nevertheless, dentists lack awareness of the COVID-19 incubation period of 1 to 14 days [12, 16], which disturbs their justification for a safe period to treat suspected patients. In the present study, academics with moderate experience of 11 to 20 years were more knowledgeable on this topic than less and more experienced ones. This is probably because they are of higher academic degree and their work hours are less than juniors so that they may have time to update themselves on COVID-19, while their concerns to infection control are greater than the older ones.

It’s crucial for dentists to know the warning signs of COVID-19, while such knowledge was insufficient among the dental academics of our study (56.93). Almost all the respondents recognized breath-shortness as a warning sign, but many of them did not know that chest pain, bluish lips or face, and new onset of confusion or inability to arouse are also warning signs. However, dentists are shown to be aware of the main symptoms of COVID-19 and the possibility of being asymptomatic, which is essential in the management and control of the disease [10, 12, 23, 24, 26].

Dental academics who participated in the present study had moderate and acceptable knowledge scores in treatment (63.14) and diagnosis (76.28) domains of COVID-19 knowledge. This seems to be sufficient as they are not considered the first-line professionals in the field. It has been shown that dental health care workers have moderate knowledge of the ineffectiveness of antibiotics for the treatment of COVID-19 [16]. According to Wang et al. [28] and Meng et al. [10], the approach to COVID-19 is to prevent the infection, reduce the risk of transmission, early diagnosis, and encourage quarantine on suspected or infected patients. Dentists are mostly aware of these approaches [24, 26]. Some of the present study’s participants didn’t know that no antiviral existed to treat COVID-19. Some were unaware of anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics usage alongside antipyretics to directly alleviate disease symptoms.

Dental academics visiting more than 20 patients daily had less knowledge about COVID-19 treatment, mainly because they are overtly engaged in their practice and have less time to gather information. In addition, dental academics dealing with less than 100 students per semester had less knowledge about treatment. This is probably due to less time in the academic environment, less contact with fellow knowledgeable academics, and less sense of duty due to fewer students.

Dentists should be aware that they could be carriers and transmit the disease to their patients. Hopefully, participants of this study had fairly good knowledge about general protection against COVID-19 (78.10), and it is expected that they protect themselves from the virus and ultimately protect their patients. As newer concepts on protection against infectious diseases, less experienced and younger academics were more knowledgeable. Also, those who had administrative roles had more knowledge about protection against COVID-19; this may be due to their sense of duty and attitude of being a role model for fellow academics.

Our study’s knowledge about dental precautions was relatively high (86.28) , which is a good sign revealing that most dental academics were informed about the guidelines. Nevertheless, some of them had little knowledge of the usefulness of pre-procedural mouth rinsing. It’s good to mention that female academics were more knowledgeable on dental precautions against COVID-19, which is in accordance with another study that reported that females, postgraduates, more experienced, and governmentally occupied dental health professionals are more knowledgeable in droplet and airborne isolation precautions [25]. However, in

Althomairy et al. study on MERS [29], females, PhD (doctor of philosophy) degree holders, and dentists working in private sectors showed better attitudes about needing additional precautions while performing AGPs.

In Khader et al. study [12], cleaning hands with alcohol-based hand rubs or soap and water, disinfecting surfaces, using PPE, and using ventilated rooms were also well known by the dentists. In contrast, Gambhir et al. [24] showed that one-third of the Indian dentists were not aware of mandatory PPE, probably showing the effect of regional health policies. Despite most of the dentists in Ahmed et al. study [27] recommended using N95 masks and universal precautions of infection control for dental procedures, most of them didn’t apply N95 masks, rubber dams, or pre-procedural antimicrobial mouthwash, and a lot of them didn’t use high-volume suction. It seems that good knowledge in this domain is insufficient, and it should become apparent in practice.

The major strength of the present study is the use of a valid and reliable international questionnaire which facilitates the between-country comparisons in the future. Moreover, multiple regression models were applied to control all the factors and discover the more associated ones. We initially looked for the independent variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in the simple linear regression with various knowledge domains and total scores acting as the dependent variable separately. Then we used multiple linear regression models for each domain and total score separately with their associated variables from the previous stage. Then we eliminated variables one by one using backward stepwise method to reach the best possible model.

This study had some limitations too. The survey link was sent to several dental academics by different possible routes to decrease the selection bias of online surveys with convenient sampling; nevertheless, self-selection bias could have occurred and influenced the results. Furthermore, female and younger dental academics were more eager to complete this survey. Unlike Kharma et al. [30], who interpreted this as these groups being more concerned with disease outbreaks, we think this may be due to more time spent online and on social media by these groups.

To encounter the inevitable limitations of the representativeness of online surveys, we tried to send the questionnaire’s link through all possible social media groups and academic emails, as well as sending reminders. Despite all said, we think that the present study’s sample was representative of the target population of Iranian dental academics and large enough to conduct the required statistical analysis. Nevertheless, generalization to other countries' dental academics or all dentists in Iran must be avoided. Finally, changes in knowledge through time are ignored due to the study’s cross-sectional nature, and no cause-effect relationship is reachable.

We suggest the study be implemented in a larger population with a more robust sampling methodology so that the results might be more generalizable. Extensive educational programs should be continued and updated to improve the knowledge of dental academics as they serve as an important source of information for students, dentists, and patients.

Conclusion

Dental academics have an overall desirable knowledge about COVID-19. Knowledge about transmission, protection, and dental precautions is good, and knowledge about treatment and diagnosis is moderate but acceptable. The lowest domain score is for the warning signs.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to all dental academics for responding to the study questionnaire. We also thank Dr. Mahsa Karimi for the back-translation of the questionnaire.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (approval ID: IR.TUMS.DENTISTRY.REC.1399.001).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose, and the funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution: Behforouz A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (30%); Razeghi S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/

Discussion Writer (20%); Shamshiri AR (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Mohebbi SZ (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist

/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: The study was funded by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 99-3-234-50465).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2021/06/16 | Accepted: 2021/09/5 | Published: 2022/01/24

Received: 2021/06/16 | Accepted: 2021/09/5 | Published: 2022/01/24

References

1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel Coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel Coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9]

3. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic [Internet]. Worldometer; 2020 Jan 22 [cited 2021 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ [Link]

4. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected: Interim guidance [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 Jan 28 [cited 2021 Jul 17]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893 [Link]

5. COVID-19 vaccination [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/index.html [Link]

6. Spagnuolo G, De Vito D, Rengo S, Tatullo M. COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview on Dentistry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2094. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17062094] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(9). [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Guidance for Dental Settings [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html [Link]

9. ADA releases interim guidance for minimizing COVID-19 transmission risl when treating dental emergencies [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2020 May 24]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/april/ada-releases-interim-guidance-on-minimizing-covid-19-transmission-risk-when-treating-emergencies [Link]

10. Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):481-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0022034520914246] [PMID] [PMCID]

11. Saqlain M, Munir MM, Rehman SU, Gulzar A, Naz S, Ahmed Z, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare professionals regarding COVID-19: A Cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(3):419-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.05.007] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Khader Y, Al Nsour M, Al-Batayneh OB, Saadeh R, Bashier H, Alfaqih M, et al. Dentists' awareness, perception, and attitude regarding COVID-19 and infection control: Cross-sectional study among Jordanian dentists. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18798. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/18798] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. Olum R, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR, Bongomin F. Coronavirus disease-2019: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front Public Health. 2020;8:181. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Ammar N, Aly NM, Folayan MO, Mohebbi SZ, Attia S, Howaldt HP, et al. Knowledge of dental academics about the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country online survey. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:399. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02308-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

15. Iranian Scientometric Information Database- ISID [Internet]. Islamic Republic of Iran: Deputy of Research and Technology of Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Islamic Republic of Iran; 2015 [cited 2020 Apr 7]. Available from: http://isid.research.ac.ir/ [Link]

16. Quadri MFA, Jafer MA, Alqahtani AS, Al-Mutaher SAB, Odabi NI, Daghriri AA, et al. Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) awareness among the dental interns, dental auxiliaries and dental specialists in Saudi Arabia: A nationwide study. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(6):856-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.010] [PMID] [PMCID]

17. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Link]

18. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html [Link]

19. Managing Healthcare Operations During COVID-19 [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-hcf.html [Link]

20. Questions and answers on coronaviruses (COVID-19) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses [Link]

21. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Interim guidance [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 Feb 27 [cited 2021 Jul 17]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331215 [Link]

22. International Business Machines Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics [Software]. Version 21.0. Armonk, New York: IBM Corp; 2012. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/spss-statistics-210-available-download [Link]

23. Gholami E, Mansori K, Soltani-Kermanshahi M. Statistical distribution of novel coronavirus in Iran. Int J One Health. 2020;6(2):143-6. [Link] [DOI:10.14202/IJOH.2020.143-146]

24. Kamate SK, Sharma S, Thakar S, Srivastava D, Sengupta K, Hadi AJ, et al. Assessing knowledge, attitudes and practices of dental practitioners regarding the COVID-19 pandemic: A multinational study. Dent Med Probl. 2020;57(1):11-7. [Link] [DOI:10.17219/dmp/119743] [PMID]

25. Singh Gambhir R, Singh Dhaliwal J, Aggarwal A, Anand S, Anand V, Kaur Bhangu A. COVID-19: A survey on knowledge, awareness and hygiene practices among dental health professionals in an Indian scenario. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2020;71(2):223-9. [Link] [DOI:10.32394/rpzh.2020.0115] [PMID]

26. Baseer MA, Ansari SH, AlShamrani SS, Alakras AR, Mahrous R, Alenazi AM. Awareness of droplet and airborne isolation precautions among dental health professionals during the outbreak of Corona virus infection in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8(4):379-87. [Link] [DOI:10.4317/jced.52811] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. De Stefani A, Bruno G, Mutinelli S, Gracco A. COVID-19 outbreak perception in Italian dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3867. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17113867] [PMID] [PMCID]

28. Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, Adnan S, Aftab M, Zafar MS, et al. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat Novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17082821] [PMID] [PMCID]

29. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.1585] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Althomairy SA, Baseer MA, Assery M, Alsaffan AD. Knowledge and attitude of dental health professionals about Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi Arabia. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2018;8(2):137-44. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_9_18] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Kharma MY, Alalwani MS, Amer MF, Tarakji B, Aws G. Assessment of the awareness level of dental students toward Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-coronavirus. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5(3):163-9. [DOI:10.4103/2231-0762.159951] [PMID] [PMCID]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |