Volume 9, Issue 3 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(3): 185-192 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Momenabadi V, Pourtaheri A, Moayedi S. Predicting the Self-Care Behaviors Associated with COVID-19 in Southeastern Iran; a Cross-Sectional Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (3) :185-192

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-46640-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-46640-en.html

1- School of Public Health, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran

2- School of Public Health, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran ,asmapourtaheri@yahoo.com

3- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran

2- School of Public Health, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran ,

3- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 595 kb]

(3095 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2420 Views)

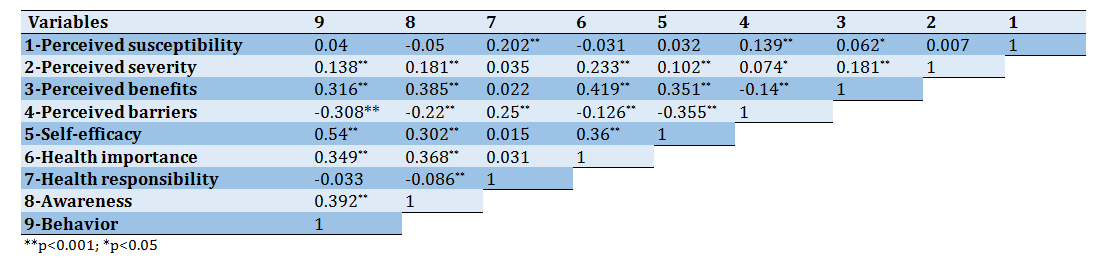

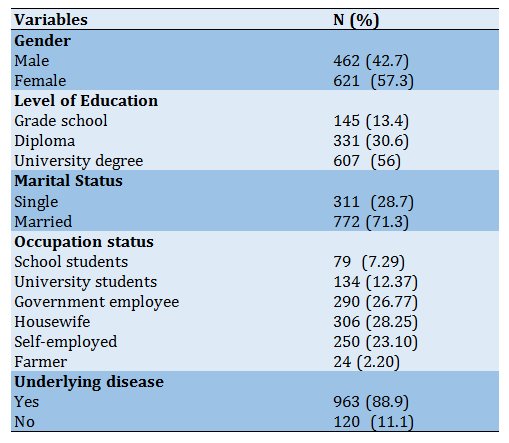

Table 2) Results of the correlation matrix of the health-promoting self-care behavior model (N=1083)

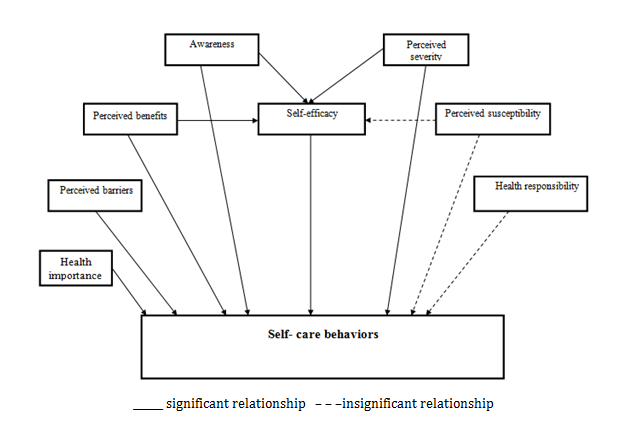

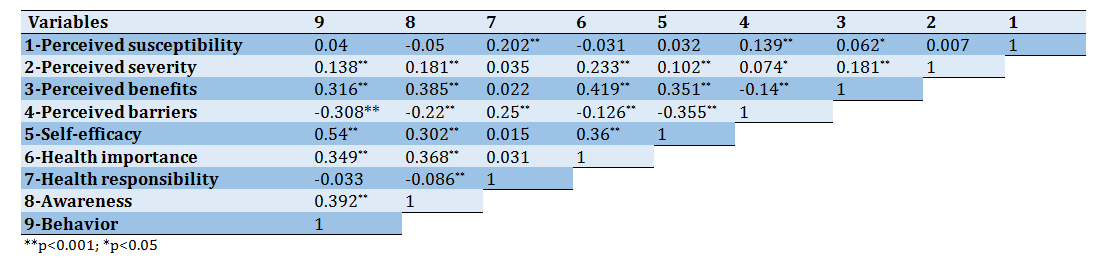

Figure 2) Primary model of self-care behaviors based on Pearson correlation results

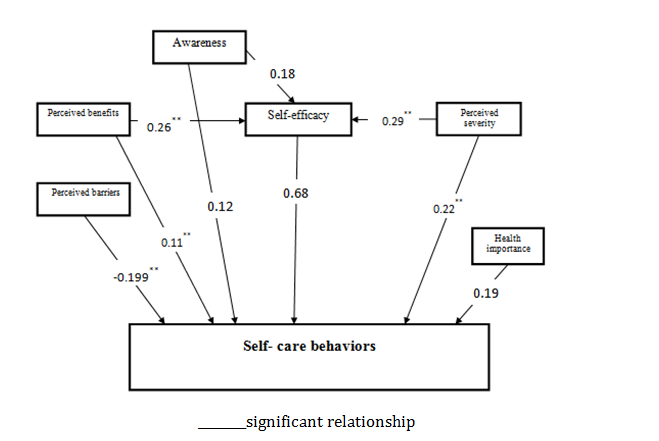

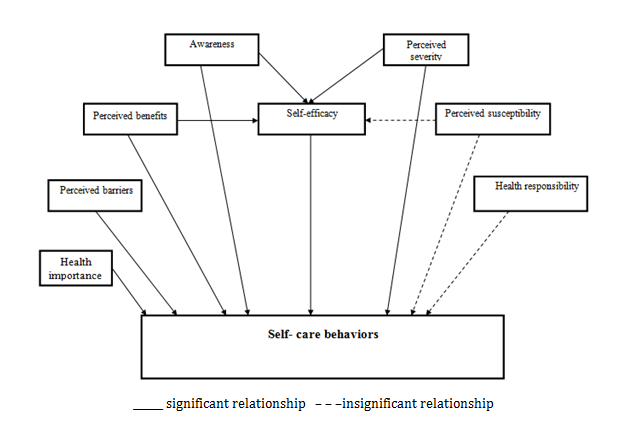

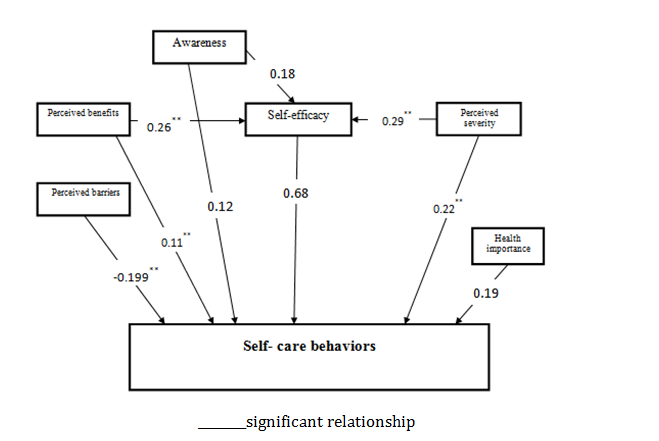

Figure 3) Final model for the pathway analysis of self-care behaviors; numbers indicate standardized path coefficient of the model

Table 3) Fit indexes of model

Table 4) Directions and standard coefficients of pathway model (p<0.05)

Discussion

The findings exhibit a positive and significant correlation between self-efficacy and self-care behaviors. According to the results of path analysis, in the direct path, improved self-efficacy raises the mean self-care behaviors to score by 0.685. Also, the self-efficacy variable exerts the highest effect on self-care behaviors, which agrees with the findings of previous studies [21, 22]. In study by Rezasefat on adolescent patients with type-2 diabetes, self-care behaviors were positively and significantly correlated with outcome expectation and self-efficacy of patients [5]. The researchers concluded that self-efficacy improvement models contributed to the adoption of self-care behaviors [23]. In his model of self-promotion, Buck et al. [24] found that self-efficacy was one of the major predictors of health and self-care.

Moreover, 86% of studies on health promotion models have confirmed the role of self-efficacy as a predictor of behavior [24]. However, Wendling et al. did not find any significant relationship between patients' self-efficacy and self-care behaviors [25]. This could be attributed to the diversity of research settings and subjects or data gathering tools.

Furthermore, the current study exhibited a positive and significant correlation between perceived severity and self-care behaviors, confirmed by SEM results. The results of the path analysis model suggested that, both in direct and indirect paths, a one-unit increase in the perceived severity increased the mean self-care behaviors score by 0.22 and 0.199, respectively. Some studies have reported a significant correlation between perceived severity and health behaviors, concluding that improved perceived severity may promote self-care behaviors among people and patients, [26] while others have not reported such a relationship [27]. This may be due to different research settings and subjects or data-gathering instruments. In a review of studies on HBM, Glanz et al. [28] reported that the predictive power of perceived susceptibility is more evident in non-repetitive preventive behaviors (e.g., screening behaviors), and perceived severity is the weakest predictor of health behaviors.

According to the results, perceived benefits are also positively and significantly correlated with self-care behaviors, corroborating with the SEM results. Moreover, according to the final path analysis model, the standardized coefficients of direct and indirect paths of perceived benefits of self-care behaviors were 0.11 and 0.178, respectively. In other words, amplifying perceived benefits increases mean self-care behaviors score by 0.11

Full-Text: (1007 Views)

Introduction

On December 31, 2019, an unusual outbreak of pneumonia caused by COVID-19 was reported in Wuhan, China [1, 2]. Presently, the disease has spread worldwide as a pandemic [3, 4]. To date, 36,237,403 people in the world have been infected with COVID-19, and 1,054,868 have lost their life. The prevalence of the disease in Iran is high. Today, all provinces of Iran are struggling with the novel coronavirus. The confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Iran were 488,236 people as of October 09, 2020.

Furthermore, the number of deaths in Iran is reported to be 27,888 so far [5]. The main transmission route of the virus is the inhalation of respiratory droplets contaminated with the virus, close contact (less than six steps or less than two meters) with an infected person, contact with the patient's nasal and laryngeal discharges, and subsequent touching of one's mouth, nose and eyes [6, 7] Due to the novelty of the COVID-19. The lack of standard treatment and effective vaccine, self-care, and infection prevention is the best and most effective strategy to break the transmission change of this disease. Therefore, it is necessary to teach people how to prevent the disease by taking measures such as covering the mouth and nose during coughing and sneezing, washing hands thoroughly with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoiding crowded places, or travel to epicenters of the disease and practicing self-quarantine for 14 days upon witnessing any suspicious symptoms. Self-care and disease prevention measures are activities undertaken by people to protect their lives and maintain their vitality and well-being [8].

As never before, the pandemic has demonstrated the importance of efficient self-care for people and societies in responding to communicable diseases [9]. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a clear contemporary illumination and affirmation of the need for population-level self-care capacities and self-care help [10].

One of the most coherent and comprehensive models that focuses on disease prevention and the factors affecting preventive measures and healthy behaviors is the 6-construct Health Belief Model (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cue to action, self-efficacy) [1]. In 2020, Marcelo Fernandes Costa [11] explored risk determinants by using the Health Belief Model (HBM). The finding showed that this model was a good predictor of preventive behavior [11] Mo et al. [12], Fall et al. [13], and Mo et al. [14] also reported that the HBM is effective in predicting the behavior of influenza vaccination and ultimately prevention of the disease. Therefore, the novelty of COVID-19 and its importance, the sense of threat and the proliferation of this disease worldwide (the disease has been recognized as a major threat to public health), and the paucity of studies on determining the predictors of self-care and preventive behaviors against the new coronavirus justify the importance of conducting this study. The first step in planning and implementing educational interventions related to health and self-care behaviors is to select the appropriate model. In this study, the dimensions of HBM and its constructs are investigated concerning the new coronavirus. The results of an extensive review of studies also indicate the role of other important factors such as awareness, health importance, and health responsibility in practicing self-care and preventive behaviors.

As the capital of Kerman province, Kerman is the largest province of Iran. With a development coefficient of 0.251, this province is one of the deprived areas of Iran (rank 10) in terms of health indicators [15]. According to the latest census in 2016, Kerman province has a population of about 3,164,718 inhabitants [16].

The novelty of coronavirus (COVID-19) and its importance, the sense of threat and the proliferation of this disease worldwide, and the paucity of studies on determining the predictors of self-care and preventive behaviors against the new coronavirus disease justify the importance of conducting this study. The first step in the process of planning and implementing educational interventions related to health and self-care behaviors is to select the appropriate model. In this study, the dimensions of HBM and its constructs are investigated in relation to the new coronavirus. By adopting a cross-sectional approach, the present study employs the main constructs of the HBM and important variables affecting self-care behavior to present a model of self-care behaviors that promotes health, therefore, this study aimed to model and determine the predictors of self-care behavior about the COVID-19.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was undertaken in 2020 on 1,083 people in Kerman province. In this web-based descriptive-analytical study, a nonrandom sampling method or volunteer sampling was used. The questionnaire link was made accessible to the people of Kerman province by relevant legal authorities, and people completed the questionnaire completely voluntarily. Schumacher et al. [17] noted that the minimum sample size for structural equations is N=200 people. However, an acceptable sample size for structural equations should not be less than 200 [18]. In this study, considering the questionnaire items (64 items), a sample size of N=700was estimated. In the end, a sample size of 1,083 people was used for statistical analysis. Unwillingness to participate in the research and failure to answer questions were exclusion criteria.

Data were collected using a self-report questionnaire, as described below:

The data collection instrument was a researcher-made questionnaire based on the constructs of the HBM [18-20]. The questionnaire consisted of 9 sections and 64 items. The demographic information section comprised six items about age, gender, marital status, occupation, level of education, and Underlying disease. Regarding the constructs of HBM, there were five items related to perceived susceptibility (Coronary heart disease is easily transmitted, so I am at risk. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). 7 items related to perceived severity (Coronary heart disease can be fatal. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). 11 items related to perceived barriers (I cannot stand the mask on my face. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). 4 items related to perceived benefits (If I follow the recommended health behaviors, my family members' chances of getting the COVID-19 will decrease. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree) and six items related to self-efficacy (I can cover my mouth and nose with a mask or a clean towel when sneezing and coughing. 3-point Likert scale I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). The constructs of awareness (8 items. Sample Awareness Question: If a patient with COVID-19 sneezes or coughs close to my face, will I get the disease? 3-point Likert scale: Yes, No, No idea), health importance (3 items. Sample Health Importance Question: I try to stay healthy. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree) and health responsibility (4 items. Sample Health Responsibility Question: to prevent COVID-19 infection, everyone in the community should follow the recommended health behaviors. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree) were examined to develop a pattern of health belief. Self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19 disease were also assessed by eight items. For example: After sneezing and coughing, I throw my handkerchief or mask in the trash, which was answered on a 3-point Likert scale; Always, sometimes, Never. The highest and lowest scores of the questionnaire were 168 and 56, respectively. The higher score indicated the better position of the participants in each of the structures. The face and content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by a five-member panel of experts (health education and health promotion specialists). The reliability of the questionnaire was also evaluated in a pilot study, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 84.0 and R=0.98 were obtained.

The Ethics Permit was obtained from the Ethics Committee of a Vice Chancellor for Research & Technology and Bam University Of Medical Science on April 25, 2020. After obtaining the necessary permits for conducting the research and making arrangements with the relevant authorities, a written informed consent form regarding the voluntary nature of participation in the study was signed by participants. They were also assured about the confidentiality of the information and guaranteed that they would not suffer any physical or moral harm if the research were terminated. The link to the questionnaire was made accessible to internet users for two weeks.

Before the analysis, the normality of research variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk Test. the result of this test confirmed the normality of the data (p>0.05). Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 22 and AMOS 18 software. Mean, standard deviation, frequency, and frequency percentages were used as descriptive statistics. Also, descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, and path analysis were used to test the primary version of the conceptual model, provide a final model and identify the direct and indirect effects of each path and standardized effects. For data analysis, various model indicators such as the goodness of fit, comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) (above 0.9), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (below 0.08), and Chi-square index/degrees of freedom (below 3) were evaluated, all of which indicating the suitability of the model. The primary conceptual model for improving self-care behaviors associated with the COVID-19 virus based on the main constructs of HBM and the literature review was presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1) Conceptual framework of self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19

Findings

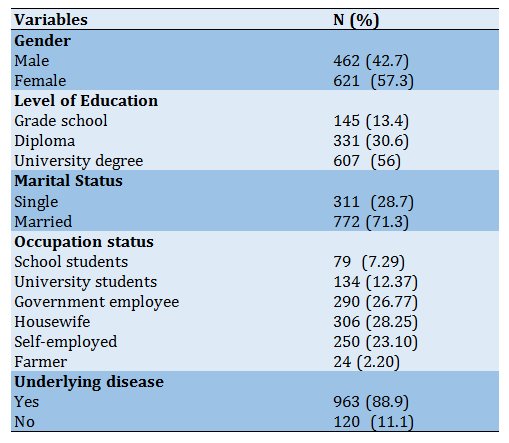

The mean age of the participants was 32.36±9.34, with an age range of 10 to 65 years. 57.3% (621 subjects) were women. 86.6% had a high school diploma and university degree, and the rest had primary and Middle school education (Table 1).

Based on the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient, the variables of perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, health importance, and awareness except for perceived susceptibility and health responsibility, were directly related to the self-care behaviors at a significant level of less than 0.001 (Table 2). Therefore, the perceived susceptibility and health responsibility variables were removed from the primary conceptual model (Figure 2), and the model was adjusted using pathway analysis.

Table 1) Demographic and social characteristics of participants

The final model of pathway analysis was presented in Figure 3. The final model's goodness-of-fit was tested, and its CFI, GFI, IFI, RMSEA, and Chi-Square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/Df) indicators were estimated. The results exhibited an acceptable fit of the model (Table 3).

In the final model, the pathway analysis results

revealed that variables of awareness, perceived benefits, and perceived severity have a significant and positive relationship with self-care behavior in both direct and indirect paths (Table 3).

The standardized beta coefficients in the direct path showed that with a one-unit increase in awareness variables, perceived benefits, and perceived severity, the mean score of self-care behavior rose by 0.125, 0.11, and 0.22, respectively, and vice versa (Figure 3). Self-efficacy variables (β=0.685, SE=0.097, p=0.001) and health importance (β=0.19, SE=0.63, p=0.001) were positively and significantly related to self-care behavior only through the direct path. The variable of perceived barriers with a coefficient of −0.199 also had a negative and significant statistical relationship with self-care behavior only in a direct path. Hence, by alleviating barriers to the behavior, the self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19 were promoted by individuals (β=−0.199, SE=0.063, p=0.001).

Considering the effect of all variables on self-care behaviors, the self-efficacy variable with a coefficient of 0.654 had the highest effect on self-care behaviors, followed by perceived severity with a coefficient of 0.419 (Table 4). According to the coefficient of determination (0.72) and the final adjusted model, 72% of the variations in self-care behaviors (R2=0.72) are explained by six constructs of perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, health importance, and awareness, and 28% of variations are justified by other variables not included in the model.

On December 31, 2019, an unusual outbreak of pneumonia caused by COVID-19 was reported in Wuhan, China [1, 2]. Presently, the disease has spread worldwide as a pandemic [3, 4]. To date, 36,237,403 people in the world have been infected with COVID-19, and 1,054,868 have lost their life. The prevalence of the disease in Iran is high. Today, all provinces of Iran are struggling with the novel coronavirus. The confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Iran were 488,236 people as of October 09, 2020.

Furthermore, the number of deaths in Iran is reported to be 27,888 so far [5]. The main transmission route of the virus is the inhalation of respiratory droplets contaminated with the virus, close contact (less than six steps or less than two meters) with an infected person, contact with the patient's nasal and laryngeal discharges, and subsequent touching of one's mouth, nose and eyes [6, 7] Due to the novelty of the COVID-19. The lack of standard treatment and effective vaccine, self-care, and infection prevention is the best and most effective strategy to break the transmission change of this disease. Therefore, it is necessary to teach people how to prevent the disease by taking measures such as covering the mouth and nose during coughing and sneezing, washing hands thoroughly with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoiding crowded places, or travel to epicenters of the disease and practicing self-quarantine for 14 days upon witnessing any suspicious symptoms. Self-care and disease prevention measures are activities undertaken by people to protect their lives and maintain their vitality and well-being [8].

As never before, the pandemic has demonstrated the importance of efficient self-care for people and societies in responding to communicable diseases [9]. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a clear contemporary illumination and affirmation of the need for population-level self-care capacities and self-care help [10].

One of the most coherent and comprehensive models that focuses on disease prevention and the factors affecting preventive measures and healthy behaviors is the 6-construct Health Belief Model (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cue to action, self-efficacy) [1]. In 2020, Marcelo Fernandes Costa [11] explored risk determinants by using the Health Belief Model (HBM). The finding showed that this model was a good predictor of preventive behavior [11] Mo et al. [12], Fall et al. [13], and Mo et al. [14] also reported that the HBM is effective in predicting the behavior of influenza vaccination and ultimately prevention of the disease. Therefore, the novelty of COVID-19 and its importance, the sense of threat and the proliferation of this disease worldwide (the disease has been recognized as a major threat to public health), and the paucity of studies on determining the predictors of self-care and preventive behaviors against the new coronavirus justify the importance of conducting this study. The first step in planning and implementing educational interventions related to health and self-care behaviors is to select the appropriate model. In this study, the dimensions of HBM and its constructs are investigated concerning the new coronavirus. The results of an extensive review of studies also indicate the role of other important factors such as awareness, health importance, and health responsibility in practicing self-care and preventive behaviors.

As the capital of Kerman province, Kerman is the largest province of Iran. With a development coefficient of 0.251, this province is one of the deprived areas of Iran (rank 10) in terms of health indicators [15]. According to the latest census in 2016, Kerman province has a population of about 3,164,718 inhabitants [16].

The novelty of coronavirus (COVID-19) and its importance, the sense of threat and the proliferation of this disease worldwide, and the paucity of studies on determining the predictors of self-care and preventive behaviors against the new coronavirus disease justify the importance of conducting this study. The first step in the process of planning and implementing educational interventions related to health and self-care behaviors is to select the appropriate model. In this study, the dimensions of HBM and its constructs are investigated in relation to the new coronavirus. By adopting a cross-sectional approach, the present study employs the main constructs of the HBM and important variables affecting self-care behavior to present a model of self-care behaviors that promotes health, therefore, this study aimed to model and determine the predictors of self-care behavior about the COVID-19.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was undertaken in 2020 on 1,083 people in Kerman province. In this web-based descriptive-analytical study, a nonrandom sampling method or volunteer sampling was used. The questionnaire link was made accessible to the people of Kerman province by relevant legal authorities, and people completed the questionnaire completely voluntarily. Schumacher et al. [17] noted that the minimum sample size for structural equations is N=200 people. However, an acceptable sample size for structural equations should not be less than 200 [18]. In this study, considering the questionnaire items (64 items), a sample size of N=700was estimated. In the end, a sample size of 1,083 people was used for statistical analysis. Unwillingness to participate in the research and failure to answer questions were exclusion criteria.

Data were collected using a self-report questionnaire, as described below:

The data collection instrument was a researcher-made questionnaire based on the constructs of the HBM [18-20]. The questionnaire consisted of 9 sections and 64 items. The demographic information section comprised six items about age, gender, marital status, occupation, level of education, and Underlying disease. Regarding the constructs of HBM, there were five items related to perceived susceptibility (Coronary heart disease is easily transmitted, so I am at risk. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). 7 items related to perceived severity (Coronary heart disease can be fatal. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). 11 items related to perceived barriers (I cannot stand the mask on my face. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). 4 items related to perceived benefits (If I follow the recommended health behaviors, my family members' chances of getting the COVID-19 will decrease. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree) and six items related to self-efficacy (I can cover my mouth and nose with a mask or a clean towel when sneezing and coughing. 3-point Likert scale I agree, I have no idea, I disagree). The constructs of awareness (8 items. Sample Awareness Question: If a patient with COVID-19 sneezes or coughs close to my face, will I get the disease? 3-point Likert scale: Yes, No, No idea), health importance (3 items. Sample Health Importance Question: I try to stay healthy. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree) and health responsibility (4 items. Sample Health Responsibility Question: to prevent COVID-19 infection, everyone in the community should follow the recommended health behaviors. 3-point Likert scale; I agree, I have no idea, I disagree) were examined to develop a pattern of health belief. Self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19 disease were also assessed by eight items. For example: After sneezing and coughing, I throw my handkerchief or mask in the trash, which was answered on a 3-point Likert scale; Always, sometimes, Never. The highest and lowest scores of the questionnaire were 168 and 56, respectively. The higher score indicated the better position of the participants in each of the structures. The face and content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by a five-member panel of experts (health education and health promotion specialists). The reliability of the questionnaire was also evaluated in a pilot study, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 84.0 and R=0.98 were obtained.

The Ethics Permit was obtained from the Ethics Committee of a Vice Chancellor for Research & Technology and Bam University Of Medical Science on April 25, 2020. After obtaining the necessary permits for conducting the research and making arrangements with the relevant authorities, a written informed consent form regarding the voluntary nature of participation in the study was signed by participants. They were also assured about the confidentiality of the information and guaranteed that they would not suffer any physical or moral harm if the research were terminated. The link to the questionnaire was made accessible to internet users for two weeks.

Before the analysis, the normality of research variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk Test. the result of this test confirmed the normality of the data (p>0.05). Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 22 and AMOS 18 software. Mean, standard deviation, frequency, and frequency percentages were used as descriptive statistics. Also, descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, and path analysis were used to test the primary version of the conceptual model, provide a final model and identify the direct and indirect effects of each path and standardized effects. For data analysis, various model indicators such as the goodness of fit, comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) (above 0.9), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (below 0.08), and Chi-square index/degrees of freedom (below 3) were evaluated, all of which indicating the suitability of the model. The primary conceptual model for improving self-care behaviors associated with the COVID-19 virus based on the main constructs of HBM and the literature review was presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1) Conceptual framework of self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 32.36±9.34, with an age range of 10 to 65 years. 57.3% (621 subjects) were women. 86.6% had a high school diploma and university degree, and the rest had primary and Middle school education (Table 1).

Based on the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient, the variables of perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, health importance, and awareness except for perceived susceptibility and health responsibility, were directly related to the self-care behaviors at a significant level of less than 0.001 (Table 2). Therefore, the perceived susceptibility and health responsibility variables were removed from the primary conceptual model (Figure 2), and the model was adjusted using pathway analysis.

Table 1) Demographic and social characteristics of participants

The final model of pathway analysis was presented in Figure 3. The final model's goodness-of-fit was tested, and its CFI, GFI, IFI, RMSEA, and Chi-Square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/Df) indicators were estimated. The results exhibited an acceptable fit of the model (Table 3).

In the final model, the pathway analysis results

revealed that variables of awareness, perceived benefits, and perceived severity have a significant and positive relationship with self-care behavior in both direct and indirect paths (Table 3).

The standardized beta coefficients in the direct path showed that with a one-unit increase in awareness variables, perceived benefits, and perceived severity, the mean score of self-care behavior rose by 0.125, 0.11, and 0.22, respectively, and vice versa (Figure 3). Self-efficacy variables (β=0.685, SE=0.097, p=0.001) and health importance (β=0.19, SE=0.63, p=0.001) were positively and significantly related to self-care behavior only through the direct path. The variable of perceived barriers with a coefficient of −0.199 also had a negative and significant statistical relationship with self-care behavior only in a direct path. Hence, by alleviating barriers to the behavior, the self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19 were promoted by individuals (β=−0.199, SE=0.063, p=0.001).

Considering the effect of all variables on self-care behaviors, the self-efficacy variable with a coefficient of 0.654 had the highest effect on self-care behaviors, followed by perceived severity with a coefficient of 0.419 (Table 4). According to the coefficient of determination (0.72) and the final adjusted model, 72% of the variations in self-care behaviors (R2=0.72) are explained by six constructs of perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, health importance, and awareness, and 28% of variations are justified by other variables not included in the model.

Table 2) Results of the correlation matrix of the health-promoting self-care behavior model (N=1083)

Figure 2) Primary model of self-care behaviors based on Pearson correlation results

Figure 3) Final model for the pathway analysis of self-care behaviors; numbers indicate standardized path coefficient of the model

Table 3) Fit indexes of model

Table 4) Directions and standard coefficients of pathway model (p<0.05)

Discussion

The findings exhibit a positive and significant correlation between self-efficacy and self-care behaviors. According to the results of path analysis, in the direct path, improved self-efficacy raises the mean self-care behaviors to score by 0.685. Also, the self-efficacy variable exerts the highest effect on self-care behaviors, which agrees with the findings of previous studies [21, 22]. In study by Rezasefat on adolescent patients with type-2 diabetes, self-care behaviors were positively and significantly correlated with outcome expectation and self-efficacy of patients [5]. The researchers concluded that self-efficacy improvement models contributed to the adoption of self-care behaviors [23]. In his model of self-promotion, Buck et al. [24] found that self-efficacy was one of the major predictors of health and self-care.

Moreover, 86% of studies on health promotion models have confirmed the role of self-efficacy as a predictor of behavior [24]. However, Wendling et al. did not find any significant relationship between patients' self-efficacy and self-care behaviors [25]. This could be attributed to the diversity of research settings and subjects or data gathering tools.

Furthermore, the current study exhibited a positive and significant correlation between perceived severity and self-care behaviors, confirmed by SEM results. The results of the path analysis model suggested that, both in direct and indirect paths, a one-unit increase in the perceived severity increased the mean self-care behaviors score by 0.22 and 0.199, respectively. Some studies have reported a significant correlation between perceived severity and health behaviors, concluding that improved perceived severity may promote self-care behaviors among people and patients, [26] while others have not reported such a relationship [27]. This may be due to different research settings and subjects or data-gathering instruments. In a review of studies on HBM, Glanz et al. [28] reported that the predictive power of perceived susceptibility is more evident in non-repetitive preventive behaviors (e.g., screening behaviors), and perceived severity is the weakest predictor of health behaviors.

According to the results, perceived benefits are also positively and significantly correlated with self-care behaviors, corroborating with the SEM results. Moreover, according to the final path analysis model, the standardized coefficients of direct and indirect paths of perceived benefits of self-care behaviors were 0.11 and 0.178, respectively. In other words, amplifying perceived benefits increases mean self-care behaviors score by 0.11

and 0.178, which is statistically significant. In this regard, some studies have reported a significant correlation between perceived benefits and self-care behavior in chronic diseases [29]. Thus, it can be argued that the perceived benefits of healthy behaviors positively impact preventive behavior and active health-seeking behaviors [30, 31]. Nevertheless, this correlation was not noted by Rahaei et al. [32]. The discrepancy of results could be attributed to different research settings, types of disease, and/or data gathering tools.

The results also exhibit a significant negative correlation between perceived barriers and self-care behaviors. In the direct path, a one-unit increase in the perceived barriers decreased the average self-care behaviors score by −0.199, which aligns with the findings reported by other researchers [33]. Dehghani-Tafti, in her study, showed that perceived benefits and barriers are related to self-care behavior in diabetic patients [34]. Therefore, it is necessary to dismantle barriers perceived in the target groups. For this purpose, we need to perform a need assessment and offer relevant training using different methods and educational materials in accordance with the cultural conditions of specific groups. To this end, barriers to self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19 should be discussed in group meetings to help reduce such barriers by exchanging experiences.

According to the results, knowledge is also positively and significantly correlated with self-care behaviors, verified by SEM results. Moreover, according to the final path analysis model results, the standardized coefficients of direct and indirect paths of knowledge in self-care behaviors were 0.125 and 0.123, respectively. In other words, increasing knowledge raises the mean self-care behaviors to score by 0.125 and 0.123, which is statistically significant. Similar results have been reported in other studies [30, 33]. The analysis of factors related to the preventive and self-care behaviors of COVID-19 and the application of HBM reveals that COVID-19 knowledge and perceived severity of the disease are major factors.

The knowledge of COVID-19 has a positive effect on practicing the behavior of 'covering nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing' and active health-seeking intention. The knowledge of COVID-19, the perceived severity of disease, the perceived benefits of healthy and self-care behaviors, and the cognition of less/free policy directly and positively impact health-seeking intention [30].

The results also exhibited a significant positive correlation between health importance and self-care behaviors. In the direct path, a one-unit increase in health importance improved the average self-care behaviors score by 0.19. The importance that people attach to their health has a bearing on how they perform self-care measures to improve their health status. Therefore, highlighting this importance will facilitate people's participation in health promotion actions [35]. The present study results also showed a positive relationship between health importance and self-care behaviors, which can heighten the motivation and hope of health workers to execute health promotion programs. The study of Tavousi et al. also showed that 69.6% of Iranians care about their health and therefore perform self-care behaviors related to protecting and promoting their health [35].

Based on the findings of this study and the constructs that play a major role in predicting self-care and health behavior, more coherent educational programs and interventions based on health education and health promotion models can be designed in the future to encourage people to adopt self-care behaviors associated with the novel coronavirus disease. The long-term results of such planning can restrict the spread and mortality of COVID-19.

This is the first study to adopt SEM to test a comprehensive theoretical model that merges the constructs of HBM and other constructs derived from the literature review as predictors of self-care behaviors associated with coronavirus in southeastern Iran. The new model presented in the study, the "Self-Care Empowerment Model", demonstrates strong predictors of self-care behaviors (both direct and indirect) among Iranian people. This is one of the major strengths of this study besides its innovation.

Our study also had several limitations. The major limitation of the present study was that not all people had access to the internet to fill out the questionnaires and that the questioner was not present when participants filled out the questionnaire. One of the limitations of the present study was that data were collected from the digital space due to specific conditions caused by limitations of the disease; hence, it did not allow random sampling to select individuals. Another limitation was concerned with data gathering based on patients' self-reports, which precluded the researcher's accurate observations.

Accordingly, it is suggested that future interventional studies on self-care behaviors associated with coronavirus based on the above model and qualitative studies identify other predictors of health-promoting self-care behaviors. Moreover, since it was impossible to evaluate health status in the research environment and people's residence, future research is recommended to consider this issue to account for marginalized people.

Conclusion

People's health and self-care behaviors against COVID-19 would be improved by enhancing self-efficacy and perceiving the benefits of self-care behavior. In addition to the main constructs of HBM, factors such as awareness and health importance also play a key role in adopting health-promoting and self-care behaviors. Finally, the self-care empowerment model is recommended as a model to improve and adopt self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful to all the participants for their cooperation in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Permit was obtained from the Ethics Committee of a Bam University of Medical Science (IR.MUBAM.REC.1399.004 and Project no: 99000004).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Momenabadi V. (First Author), Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (40%); Pourtaheri A. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Methodologist (40%); Moayedi S. (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (20%).

Funding/Support: The research project was financially supported by Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran (grant No:99000004).

The results also exhibit a significant negative correlation between perceived barriers and self-care behaviors. In the direct path, a one-unit increase in the perceived barriers decreased the average self-care behaviors score by −0.199, which aligns with the findings reported by other researchers [33]. Dehghani-Tafti, in her study, showed that perceived benefits and barriers are related to self-care behavior in diabetic patients [34]. Therefore, it is necessary to dismantle barriers perceived in the target groups. For this purpose, we need to perform a need assessment and offer relevant training using different methods and educational materials in accordance with the cultural conditions of specific groups. To this end, barriers to self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19 should be discussed in group meetings to help reduce such barriers by exchanging experiences.

According to the results, knowledge is also positively and significantly correlated with self-care behaviors, verified by SEM results. Moreover, according to the final path analysis model results, the standardized coefficients of direct and indirect paths of knowledge in self-care behaviors were 0.125 and 0.123, respectively. In other words, increasing knowledge raises the mean self-care behaviors to score by 0.125 and 0.123, which is statistically significant. Similar results have been reported in other studies [30, 33]. The analysis of factors related to the preventive and self-care behaviors of COVID-19 and the application of HBM reveals that COVID-19 knowledge and perceived severity of the disease are major factors.

The knowledge of COVID-19 has a positive effect on practicing the behavior of 'covering nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing' and active health-seeking intention. The knowledge of COVID-19, the perceived severity of disease, the perceived benefits of healthy and self-care behaviors, and the cognition of less/free policy directly and positively impact health-seeking intention [30].

The results also exhibited a significant positive correlation between health importance and self-care behaviors. In the direct path, a one-unit increase in health importance improved the average self-care behaviors score by 0.19. The importance that people attach to their health has a bearing on how they perform self-care measures to improve their health status. Therefore, highlighting this importance will facilitate people's participation in health promotion actions [35]. The present study results also showed a positive relationship between health importance and self-care behaviors, which can heighten the motivation and hope of health workers to execute health promotion programs. The study of Tavousi et al. also showed that 69.6% of Iranians care about their health and therefore perform self-care behaviors related to protecting and promoting their health [35].

Based on the findings of this study and the constructs that play a major role in predicting self-care and health behavior, more coherent educational programs and interventions based on health education and health promotion models can be designed in the future to encourage people to adopt self-care behaviors associated with the novel coronavirus disease. The long-term results of such planning can restrict the spread and mortality of COVID-19.

This is the first study to adopt SEM to test a comprehensive theoretical model that merges the constructs of HBM and other constructs derived from the literature review as predictors of self-care behaviors associated with coronavirus in southeastern Iran. The new model presented in the study, the "Self-Care Empowerment Model", demonstrates strong predictors of self-care behaviors (both direct and indirect) among Iranian people. This is one of the major strengths of this study besides its innovation.

Our study also had several limitations. The major limitation of the present study was that not all people had access to the internet to fill out the questionnaires and that the questioner was not present when participants filled out the questionnaire. One of the limitations of the present study was that data were collected from the digital space due to specific conditions caused by limitations of the disease; hence, it did not allow random sampling to select individuals. Another limitation was concerned with data gathering based on patients' self-reports, which precluded the researcher's accurate observations.

Accordingly, it is suggested that future interventional studies on self-care behaviors associated with coronavirus based on the above model and qualitative studies identify other predictors of health-promoting self-care behaviors. Moreover, since it was impossible to evaluate health status in the research environment and people's residence, future research is recommended to consider this issue to account for marginalized people.

Conclusion

People's health and self-care behaviors against COVID-19 would be improved by enhancing self-efficacy and perceiving the benefits of self-care behavior. In addition to the main constructs of HBM, factors such as awareness and health importance also play a key role in adopting health-promoting and self-care behaviors. Finally, the self-care empowerment model is recommended as a model to improve and adopt self-care behaviors associated with COVID-19.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful to all the participants for their cooperation in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Permit was obtained from the Ethics Committee of a Bam University of Medical Science (IR.MUBAM.REC.1399.004 and Project no: 99000004).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Momenabadi V. (First Author), Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (40%); Pourtaheri A. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Methodologist (40%); Moayedi S. (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (20%).

Funding/Support: The research project was financially supported by Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran (grant No:99000004).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2020/10/17 | Accepted: 2021/03/17 | Published: 2021/08/31

Received: 2020/10/17 | Accepted: 2021/03/17 | Published: 2021/08/31

References

1. Wu JT LK, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: A modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9]

2. Lai CC, Shi TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(3):105924. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157-60. [Link]

4. World health organization. WHO Coronavirus dashboard [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited Unknown]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. [Link]

5. World health organization. Coronavirus in Iran (Islamic Republic of) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited Unknown]. Available from: https://www.who.int/countries/irn. [Link]

6. Bekele D, Tolossa T, Tsegaye R, Teshome W. The knowledge and practice towards COVID-19 pandemic prevention among residents of Ethiopia: An online cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2021;16(1):0234585. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0234585] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. World health organization. Self-care during COVID-19 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited Unknown]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/self-care-during-covid-19. [Link]

8. Salimian S, Esmaieli R, Dabirian A, Mansoorin S, Zohari Anboohi S. The survey of factors related to self-efficacy based on Orem's theory in patients with coronary artery bypass surgery in Tehran in 2014. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2015;25(90):9-16. [Persian] [Link]

9. Mehraeen E, Hayati B, Saeidi S, Heydari M, Seyedalinaghi S. Self-care instructions for people not requiring hospitalization for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2020;15:102978. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/archcid.102978]

10. Shahnazi H, Ahmadi-Livani M, Pahlavanzadeh B, Rajabi A, Hamrah MS, Charkazi A. Assessing preventive health behaviors from COVID-19: a cross sectional study with health belief model in Golestan province, northern of Iran. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):157. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40249-020-00776-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

11. Costa MF. Health belief model for coronavirus infection risk determinants. Rev Saude Public. 2020;54:47. [Link] [DOI:10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054002494] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Mo PKH, Wong CH, Lam EHK. Can the health belief model and moral responsibility explain influenza vaccination uptake among nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(6):1188-206. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jan.13894] [PMID]

13. Fall E, Izaute M, Chakroun-Baggioni N. How can the health belief model and self-determination theory predict both influenza vaccination and vaccination intention? a longitudinal study among university students. Psychol Health. 2018;33(6):746-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2017.1401623] [PMID]

14. Mo PKH, Lau JTF. Influenza vaccination uptake and associated factors among elderly population in Hong Kong: The application of the health belief model. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(5):706-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/her/cyv038] [PMID]

15. Yazdani MH, Montazer F. Analysis of indicators of health status in provinces and ten regions of Iran. Health Dev J. 2020;6(4):290-301. [Persian] [Link]

16. Ahmadi Tabatabaei SV, Ardabili HE, Haghdoost AA, Dastoorpoor M, Nakhaee N, Shams M. Factors affecting physical activity behavior among women in Kerman based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2017;19(10). [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.14057]

17. Tarka P. An overview of structural equation modeling: its beginnings, historical development, usefulness and controversies in the social sciences. Qual Quant Int J Methodol. 2018;52(1):313-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11135-017-0469-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Carico R, Sheppard J, Thomas CB. Community pharmacists and communication in the time of COVID-19: Applying the health belief model. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1984-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.017] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Wong LP, Alias H, Wong PF, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279] [PMID] [PMCID]

20. Shewasinad Yehualashet S, Asefa KK, Mekonnen AG, Gemeda BN, Shiferaw WS, Aynalem YA, et al. Predictors of adherence to COVID-19 prevention measure among communities in north Shoa zone, Ethiopia based on health belief model: A cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2021;16(1):0246006. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0246006] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Salahshoori A, Harooni J, Salahshouri S, Hasanzadeh A, Mostafavi F, Molaei M. Investigation on association between self-efficacy, perceived barriers and social supports with health promoting behaviors in elderly in Dena city. Health Syst Res. 2015;11(1):30-42. [Persian] [Link]

22. Rezasefat Balesbaneh A, Mirhaghjou N, Jafsri Asl M, Kohmanaee S, Kazemnejad Leili E, Monfared A. Correlation between self-care and self-efficacy in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2014;24(2):18-24. [Persian] [Link]

23. Buglar ME, White KM, Robinson NG. The role of self-efficacy in dental patients' brushing and flossing: Testing an extended health belief model. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):269-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.014] [PMID]

24. Buck HG, Dickson VV, Fida R, Riegel B, D'Agostino F, Alvaro R, et al. Predictors of hospitalization and quality of life in heart failure: A model of comorbidity, self-efficacy and self-care. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(11):1714-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.06.018] [PMID]

25. Wendling S, Beadle V. The relationship between self-efficacy and diabetic foot self-care. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(1):37-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcte.2015.01.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Kasmaei P, Shokravi FA, Hidarnia A, Hajizadeh E, Atrkar-Roushan Z, Shirazi KK, et al. Brushing behavior among young adolescents: does perceived severity matter. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:8. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-14-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Solhi M, Shojaei Zadeh D, Seraj B, Faghih Zadeh S. The application of the health belief model in oral health education. Iran J Public Health. 2010;39(4):114-9. [Link]

28. Sulat JS, Prabandari YS, Sanusi R, Hapsari ED, Santoso B. The validity of health belief model variables in predicting behavioral change: A scoping review. Health Educ. 2018;118(16). [Link] [DOI:10.1108/HE-05-2018-0027]

29. Mohebi S, Azadbakht L, Feizi A, Sharifirad G, Kargar M. Structural role of perceived benefits and barriers to self-care in patients with diabetes. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:37. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.115831] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Li ZT, Yang SS, Zhang XX, Fisher EB, Tian BC, Sun XY. Complex relation among Health Belief Model components in TB prevention and care. Public Health. 2015;129(7):907-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.008] [PMID]

31. Baghianimoghadam MH, Mirzaei M, Rahimdel T. Role of health beliefs in preventive behaviors of individuals at risk of cardiovascular diseases. Health Syst Res. 2013;8(7):1151-8. [Persian] [Link]

32. Rahaei Z, Morowatisharifabad MA, Zareiyan M, Shojaefard J, Lesan S. Perceived benefits and barriers of preventive behaviours of relapsed myocardial infraction. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2011;13(2):117-22. [Persian] [Link]

33. Namdar A, Bigizadeh S, Naghizadeh MM. Measuring health belief model components in adopting preventive behaviors of cervical cancer. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2012;2(1):34-44. [Persian] [Link]

34. Dehghani-Tafti A, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Morowatisharifabad MA, Ardakani MA, Rezaeipandari H, Lotfi MH. Determinants of self-care in diabetic patients based on health belief model. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7(5):33-42. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n5p33] [PMID] [PMCID]

35. Zareipour MA, Ardakani MF, Moradali MR, Jadgal MS, Movahed E. Determinants of COVID-19 prevention behavior in the elderly in Urmia: Application of health belief model. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020;8(1):646-50. [Link] [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2020.5653]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |