Volume 10, Issue 4 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(4): 771-778 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yunus S, Mohamed M, Fauzi M, Marimuthu G, Anuar M, Ithnain N et al . Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice towards COVID-19; A Community Survey in North-Borneo (Sabah), Malaysia. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (4) :771-778

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-64139-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-64139-en.html

S.Z.S.A. Yunus1, M.H. Mohamed *2, M.A.M. Fauzi3, G. Marimuthu1, M.F.M. Anuar1, N. Ithnain1, S.S.S.A. Rahim4

1- National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia

2- Faculty of Psychology & Education, University Malaysia Sabah, Sabah, Malaysia

3- Department of Medical Social Work, University Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia

4- Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciene, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Sabah, Malaysia

2- Faculty of Psychology & Education, University Malaysia Sabah, Sabah, Malaysia

3- Department of Medical Social Work, University Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia

4- Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciene, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Sabah, Malaysia

Keywords: Knowledge [MeSH], Attitude [MeSH], General Practice [MeSH], COVID-19 [MeSH], Borneo [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 1411 kb]

(698 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (936 Views)

Table 3) Attitude towards COVID-19 by demographic using Pearson Chi-square analysis

Table 4) Results of multiple logistic regression analysis on factors associated with attitude towards COVID-19

Table 5) Practice towards COVID-19 by demographic using Chi-square analysis

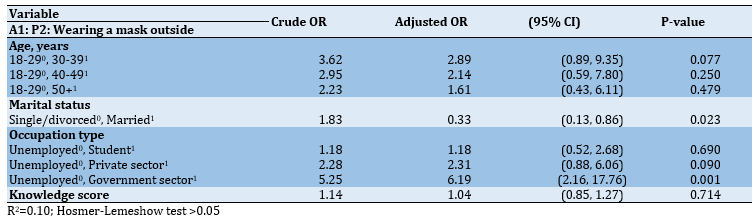

Table 6) Results of multiple logistic regression analysis on factors associated with practice towards COVID-19

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the respondents in North Borneo Malaysia, Sabah have adequate knowledge about the clinical presentations of the COVID-19 virus as well as the prevention and control of the virus. The result showed a similar correct rate for knowledge score at 84.2% with the previous study conducted in multiple regions in Malaysia [12]. The high knowledge score in this study may be due to the characteristics of the respondents, who were mostly highly educated. However, there were some misconceptions in our study and another study in which 75.6% of respondents believed that COVID-19 infection occurs through eating or contact with wild animals [13]. Although education level does not show a significant association with knowledge about the COVID-19 virus, several other studies conducted in China [11], the United Arab Emirates [14], Nepal [15], Indonesia [16], and a recent study in Malaysia [13] suggested that higher education level was associated with higher COVID-19 knowledge. We suggest that the educational awareness program for COVID-19 should focus on communities with lower education levels. The transition from pandemic to endemic status will take some time, and educating the public about the effects of COVID-19 as well as, harm reduction must be ongoing. It is recommended to emphasize educating the communities with lower education levels in North Borneo, such as those unable to use modern technology and those living in rural areas with limited network access. Educational programs should be more informative, interesting, and interactive to meet the level of understanding of the communities. Introducing social workers and health education officers as a facilitator in promoting education about COVID-19 to such communities would be beneficial as they are experts in behavior modification with cultural competencies. In addition, having COVID-19 survivors as part of the education program could improve the reachability of the programs, especially among the indigenous community in North Borneo.

Our study found that age, marital status, and occupation type are significantly associated with a higher average knowledge score on COVID-19. The results showed that both males and females have similar knowledge scores on COVID-19. Another study conducted in Indonesia also showed a similar finding that there was a significant difference in average knowledge score between age groups, marital status, education levels, and occupation types [16]. In the present study, the respondents aged 40 to 49 obtained the highest knowledge score compared to other age groups. The high rate of knowledge scores among the older generation groups in this study might be associated with the concerns that COVID-19 has a huge impact on the health of older people, especially those with comorbidities [17]. This suggests that older age groups are likely to have more health care concerns due to a higher risk of complications. However, other studies in Nepal and Bangladesh have shown that younger generations are more knowledgeable about COVID-19 compared to older generations [15, 18]. Therefore, any educational program related to COVID-19 should be focused on all age groups. More measures should also be done to address such misconceptions and misinformation with correct health information.

Based on the analysis, married people had a higher average knowledge score about COVID-19 compared to single/divorced people. Similar findings have been shown by other studies in China and North Sulawesi, Indonesia [19, 20]. Married respondents may want to know more about COVID-19 so they can protect their children and family members and make informed decisions. Moreover, the concept of individualism of the respondents could result in lower knowledge scores among the single respondents. A recent study showed that the more individualistic the participants, the higher the chance of non-compliance with epidemic prevention measures [21]. We suggest authorities foster and promote a collective mindset among single people regarding COVID-19 in creating safe environments, especially during the outbreak of COVID-19.

People who worked in the public sector showed a higher knowledge score about COVID-19. Recent studies that were also done in Malaysia and Ethiopia found that respondents that work in the public sector have high knowledge scores compared with unemployed respondents [13, 22]. Higher average knowledge scores among those who worked in the government sector may be attributed to the fact that government’s promotion towards strict Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) in the working place, especially during the MCO. It is also important to note that many efforts have been made by governments at all levels, such as public awareness campaigns on several media platforms conducted by the Ministry of Health. Results showed that unemployed respondents have the lowest knowledge score about COVID-19. A recent data collection showed that the majority of those suffering from their jobs in Sabah are people in low-income groups, and the unemployment that happens in Sabah is more severe rather than in other states in Malaysia [23]. It indicates that unemployed respondents know less about COVID-19 and focus on making financial stability. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected working hours, causing many people to lose their jobs, reduce total household income, and struggle to find new sources of income.

In this study, respondents who disagreed with the success of controlling the COVID-19 virus had significantly lower knowledge scores than those who agreed. A stream of similar studies in various countries among the general population on knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to COVID-19 depicted a higher knowledge score among those who reported a favorable attitude toward final success in controlling COVID-19 [24-27]. This study provides further empirical evidence of the prediction of higher knowledge scores, which is probably related to the feasible data collection method during the outbreak through an online survey where most of the online respondents are from the younger group with higher education who are students.

A survey during the same period of the present study [12] similarly reported a high score of knowledge and positive attitude towards successful outbreak control. Generally, the favorable attitude and high knowledge score towards COVID-19 [18, 26, 28-30] can probably be reflected by the ease of access to various sources of information as well as active and potentially skilled information seeking during the outbreak among the population of this study. Multiple logistic regression showed that as the knowledge score about COVID-19 increased, it was 1.35 more likely to have a positive attitude toward the eventual success in controlling the epidemic. According to a study on the relationship between COVID-19 information sources and attitudes in battling the pandemic, the Ministry of Health (MOH) was the most preferred source of information among respondents during the MCO in Malaysia [25]. The information by MOH Malaysia was instantaneously updated online through the official website and social media. Those who referred most to the official information were more likely to be confident that Malaysia could win the battle against COVID-19, which could be the reason this study witnessed similar high confidence in winning the COVID-19 battle. The optimism and confidence could also be related to strict SOP during the MCO along with the "flatten the curve" notion widely relayed during the initial phase of the outbreak. There was a strong hint of confidence in the Government of Malaysia when it comes to consistent SOP implementation and responses to contain COVID-19 [10].

Practice

In terms of information-seeking behavior, an obvious global increase in searching for COVID-19 information was also observed in Malaysia and was highly related to learning about recommended precautionary measures, with a clear increase in searches since the announcement of the first MCO, which was phasing through this survey period. Google Trend analysis showed that the searches were on the mask, hand sanitizer, and COVID-19 [31]. This could explain why the majority of respondents reported good compliance with COVID-19 preventive practices, where 98.1% (n=526) claimed not to have visited crowded places, which could be due to the recent implementation of the MCO. A total of 82.8% (444 people) wore masks whenever they went out in recent days. A study on new norm practice also reported high compliance with avoiding public gatherings, social distancing, hand hygiene, and mask-wearing. Fear of losing the job, income, and social life may also be a motivation for compliance [32]. The rate of wearing mask practice was significantly different in age groups, marital status, and occupation type. Based on the analysis, people who worked in the government sector were 6.19 times more likely to wear a mask outside than unemployed respondents. People in government sectors predicted high compliance in wearing masks, as they are usually the first adopters of any government measures [32].

According to the results of this study, health education programs and activities to improve the literacy of the people of Sabah state regarding COVID-19 should be done based on specific groups with more aggressiveness and creativity so that the information provided is acceptable by all levels of society in the state of Sabah.

There were three limitations of this study: First, this study was only conducted online and widely disseminated when the new COVID-19 pandemic hit Malaysia. Therefore this study cannot be conducted using a systematic sample population.

Secondly, since this study was conducted using a cross-sectional study method, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the population in the state of Sabah.

Thirdly, this study was self-administered. Therefore, the researcher cannot control all the answers filled in by the respondents in this study.

It is recommended to conduct qualitative studies at different levels of society and stakeholders to improve the quality of health education services in this country in the future.

Conclusion

The level of knowledge of the residents in Sabah, Malaysia, about COVID-19 is quite satisfactory. Meanwhile, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 differ according to the socio-demography of the population in Sabah.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Director General of Health, Ministry of Health, Malaysia, for approval to publish this article. Ethical Permission: Since this study was conducted during the early stages of the COVID-19 infection in Malaysia, ethical considerations did not apply. However, this study has received publication approval from the MALAYSIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contribution: Yunus SZSA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mohamed MH (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (40%); Fauzi MAM (Third Author), Discussion Writer (10%); Marimuthu G (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (5%); Anuar MFM (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (5%); Ithnain N (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Rahim SSSA (Seventh Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (5%)

Funding: None.

Full-Text: (148 Views)

Introduction

Since December 2019, Malaysia, like other countries, has been facing the pandemic of novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a public health emergency and urged countries to take urgent measures against the spread of the virus [1]. As of December 2020, there were more than 300 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, with more than 5 million deaths [2]. In Malaysia, there were more that 2 million positive cases, with approximately 200 thousand positive cases in North-Borneo Malaysia, Sabah. To date, there were a total of 434 clusters in Sabah [3].

Malaysia recorded its first case of COVID-19 on 25 January 2020, involving three tourists from China who had traveled to Malaysia from Singapore via Johor. The first wave started when the number of cases increased to 22 on 16 February 2020, followed by the second wave that began on 27 February [4]. Day by day, the number of people infected with this virus increases, and more than 100 people die. The situation prompted the Malaysian government to implement a two-week Movement Control Order (MCO) from 18 March to 31 March 2020, where the MCO was enforced under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 and the Police Act 1967. This drastic immediate action was taken to stop the spread of COVID-19, and everyone in Malaysia must follow this order [5].

The MCO was later extended into several different phases, including a recovery phase from June until the end of 2020. At that time, responding to the pandemic was a challenge especially with no effective vaccine or treatments yet to be clinically proven. To combat the virus, the public must have a good knowledge and attitude to practice (KAP) and good behavior during this pandemic. Since the earlier cases reported in Sabah, all direct flights from mainland China have been stopped. Further travel restrictions towards the three most affected countries, namely Iran, Italy, and South Korea, were imposed by the government by March 2020. In line with the MCO, non-Sabahan wares were banned from entering the state as additional efforts to counter the increased number of positive cases [6, 7]. China has shown that quarantine, social distancing, and isolation of infected populations can contain the pandemic [8]. With the lack of clinical measures, it was important for the general public to participate in preventive behaviors and disease surveillance and response at the policy level. Educating, engaging, and mobilizing the public to become active participants may assist in public health emergency preparedness. Therefore, the overall vulnerability of the population decreased [9]. Following this, a vast amount of public health messages has been distributed on many platforms to disseminate information on preventive measures that can be taken by the public to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Effective management of pandemics requires understanding the factors affecting population behavior. This study aimed to describe the knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among the residents in Sabah, Malaysia, during the movement control period.

Instruments and Methods

Study design and data collection

This cross-sectional study was conducted from March to April 2020 during the first MCO using the convenience sampling method. Due to the movement restriction, this survey was conducted online via Google Sheets, similar to the online method used by De Man in 2019 [10]. The questionnaires were distributed to the public using personal network resources available from the researchers and assisted by students from the Social Work Program, University Malaysia Sabah (UMS). Study information, along with the questionnaire’s link, was disseminated through various platforms of social media, including WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter. Information about the survey and researchers’ details included at the beginning of the page. Participants 18 years and older were allowed to voluntarily complete the questionnaire after agreeing to the consent form. All data were kept private and confidential. All personal identifiers were removed before the analysis.

Study instrument

The questionnaire in this study was adopted by an online study on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 during the outbreak in Wuhan, China [11]. This questionnaire undergones a direct translation process (English-Malay) by a translator from the Health Education Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH) and was pretested prior to data collection. The questionnaire consisted of four parts: 1) Demographics variables, 2) 12 questions on knowledge of COVID-19, including clinical presentations (K1-K4), transmission routes (K5-K7), and prevention and controls (K8-K12), 3) Two questions on attitudes towards COVID-19 (A1-A2), and 4) Two questions on practice towards COVID-19 (P1-P2). All questions were provided with “true”, ‘false”, and “not sure” as the answers. All right answers were scored with “1”, and the wrong and uncertain answers were scored with “0”. The total score for knowledge was 12, and those with higher score were considered as higher knowledge about COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 software. All results of quantitative variables were reported either with mean and standard deviation (SD) or frequency. Pearson chi-square analysis and multiple logistic regression analysis were performed to identify factors associated with knowledge, attitude, and practice among the respondents in Sabah. Model fitness was checked by using Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test. Adjusted odds ratio was used to determine the strength association between the dependent and independent variables.

Findings

A total of 536 participants from Sabah completed the questionnaire online. Table 1 details the demographic characteristics of the respondents and the knowledge score of COVID-19.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of the respondents in Sabah and knowledge score of COVID-19 (n=536)

Since December 2019, Malaysia, like other countries, has been facing the pandemic of novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a public health emergency and urged countries to take urgent measures against the spread of the virus [1]. As of December 2020, there were more than 300 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, with more than 5 million deaths [2]. In Malaysia, there were more that 2 million positive cases, with approximately 200 thousand positive cases in North-Borneo Malaysia, Sabah. To date, there were a total of 434 clusters in Sabah [3].

Malaysia recorded its first case of COVID-19 on 25 January 2020, involving three tourists from China who had traveled to Malaysia from Singapore via Johor. The first wave started when the number of cases increased to 22 on 16 February 2020, followed by the second wave that began on 27 February [4]. Day by day, the number of people infected with this virus increases, and more than 100 people die. The situation prompted the Malaysian government to implement a two-week Movement Control Order (MCO) from 18 March to 31 March 2020, where the MCO was enforced under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 and the Police Act 1967. This drastic immediate action was taken to stop the spread of COVID-19, and everyone in Malaysia must follow this order [5].

The MCO was later extended into several different phases, including a recovery phase from June until the end of 2020. At that time, responding to the pandemic was a challenge especially with no effective vaccine or treatments yet to be clinically proven. To combat the virus, the public must have a good knowledge and attitude to practice (KAP) and good behavior during this pandemic. Since the earlier cases reported in Sabah, all direct flights from mainland China have been stopped. Further travel restrictions towards the three most affected countries, namely Iran, Italy, and South Korea, were imposed by the government by March 2020. In line with the MCO, non-Sabahan wares were banned from entering the state as additional efforts to counter the increased number of positive cases [6, 7]. China has shown that quarantine, social distancing, and isolation of infected populations can contain the pandemic [8]. With the lack of clinical measures, it was important for the general public to participate in preventive behaviors and disease surveillance and response at the policy level. Educating, engaging, and mobilizing the public to become active participants may assist in public health emergency preparedness. Therefore, the overall vulnerability of the population decreased [9]. Following this, a vast amount of public health messages has been distributed on many platforms to disseminate information on preventive measures that can be taken by the public to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Effective management of pandemics requires understanding the factors affecting population behavior. This study aimed to describe the knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among the residents in Sabah, Malaysia, during the movement control period.

Instruments and Methods

Study design and data collection

This cross-sectional study was conducted from March to April 2020 during the first MCO using the convenience sampling method. Due to the movement restriction, this survey was conducted online via Google Sheets, similar to the online method used by De Man in 2019 [10]. The questionnaires were distributed to the public using personal network resources available from the researchers and assisted by students from the Social Work Program, University Malaysia Sabah (UMS). Study information, along with the questionnaire’s link, was disseminated through various platforms of social media, including WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter. Information about the survey and researchers’ details included at the beginning of the page. Participants 18 years and older were allowed to voluntarily complete the questionnaire after agreeing to the consent form. All data were kept private and confidential. All personal identifiers were removed before the analysis.

Study instrument

The questionnaire in this study was adopted by an online study on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 during the outbreak in Wuhan, China [11]. This questionnaire undergones a direct translation process (English-Malay) by a translator from the Health Education Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH) and was pretested prior to data collection. The questionnaire consisted of four parts: 1) Demographics variables, 2) 12 questions on knowledge of COVID-19, including clinical presentations (K1-K4), transmission routes (K5-K7), and prevention and controls (K8-K12), 3) Two questions on attitudes towards COVID-19 (A1-A2), and 4) Two questions on practice towards COVID-19 (P1-P2). All questions were provided with “true”, ‘false”, and “not sure” as the answers. All right answers were scored with “1”, and the wrong and uncertain answers were scored with “0”. The total score for knowledge was 12, and those with higher score were considered as higher knowledge about COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 software. All results of quantitative variables were reported either with mean and standard deviation (SD) or frequency. Pearson chi-square analysis and multiple logistic regression analysis were performed to identify factors associated with knowledge, attitude, and practice among the respondents in Sabah. Model fitness was checked by using Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test. Adjusted odds ratio was used to determine the strength association between the dependent and independent variables.

Findings

A total of 536 participants from Sabah completed the questionnaire online. Table 1 details the demographic characteristics of the respondents and the knowledge score of COVID-19.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of the respondents in Sabah and knowledge score of COVID-19 (n=536)

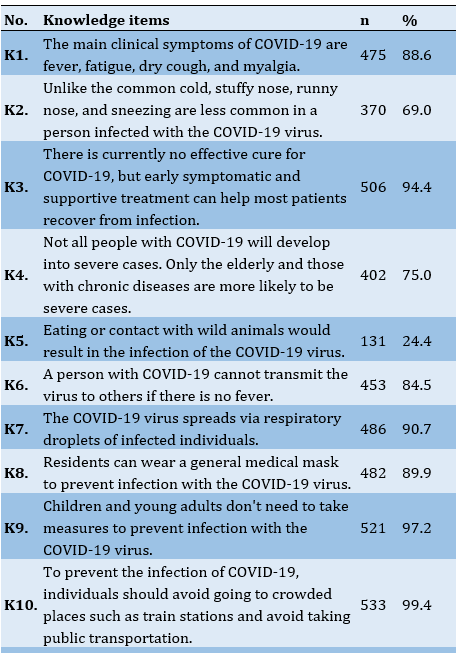

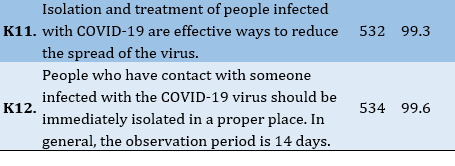

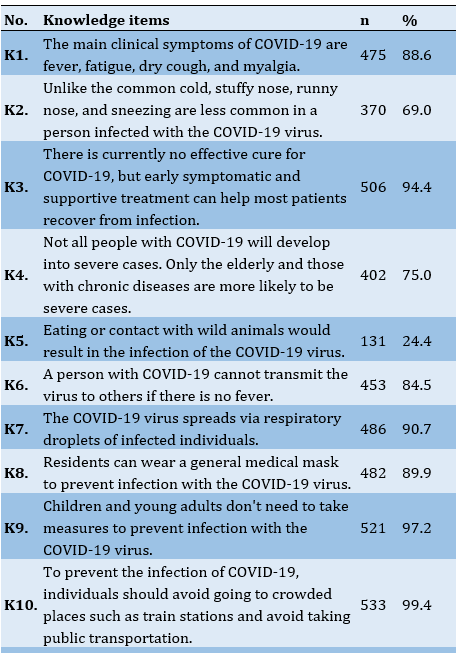

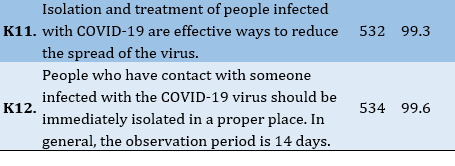

Of the 12 questions on the knowledge of COVID-19, the mean score was 10.1±1.2 (ranged 0–12), suggesting an overall 84.2% (10.1/12 × 100) correct rate on this knowledge test. Knowledge scores were significantly different in terms of age group, marital status, and occupation type. The high prevalence of misunderstanding was discovered in a knowledge item where 75.6 (n=405) believed that infection of COVID-19 is caused by eating or having contact with wild animals. In general, the respondents were well aware of the prevention and control of the COVID-19 virus (Table 2).

A total of 58.4% (n=313) of respondents agreed that COVID-19 will finally be successfully controlled. While 41.6% (n=223) disagreed. The attitude towards the final success in controlling COVID-19 was significantly different in age groups, marital status, and occupation types (p<0.05). In addition, respondents reporting disagreement had significantly lower knowledge scores than those reporting agreement (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 2) Frequency of correct answers to knowledge items

Multiple logistic regression showed that respondents with higher COVID-19 knowledge scores [aOR: 1.35; 95% CI: (1.15, 1.59)] were significantly associated with confidence towards the final success in controlling COVID-19. A large percentage of respondents, 94.4% (n=506), was confident that Malaysia will win the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4).

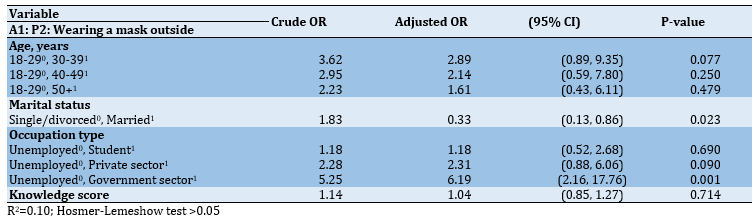

The majority of the respondents, 98.1% (n=526), had not visited any crowded places, and a total of 82.8% (n=444) had worn a mask whenever they went out in recent days. The rates of wearing mask practice were significantly different in age groups, marital status, and occupation type (Table 5).

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that 67% of married people are less likely to wear masks outside. Meanwhile, those who are working in the government sector were 6.19 times more likely to be wearing masks outside [aOR: 6.19; 95% (CI): (2.16, 17.76); Table 6].

A total of 58.4% (n=313) of respondents agreed that COVID-19 will finally be successfully controlled. While 41.6% (n=223) disagreed. The attitude towards the final success in controlling COVID-19 was significantly different in age groups, marital status, and occupation types (p<0.05). In addition, respondents reporting disagreement had significantly lower knowledge scores than those reporting agreement (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 2) Frequency of correct answers to knowledge items

Multiple logistic regression showed that respondents with higher COVID-19 knowledge scores [aOR: 1.35; 95% CI: (1.15, 1.59)] were significantly associated with confidence towards the final success in controlling COVID-19. A large percentage of respondents, 94.4% (n=506), was confident that Malaysia will win the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4).

The majority of the respondents, 98.1% (n=526), had not visited any crowded places, and a total of 82.8% (n=444) had worn a mask whenever they went out in recent days. The rates of wearing mask practice were significantly different in age groups, marital status, and occupation type (Table 5).

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that 67% of married people are less likely to wear masks outside. Meanwhile, those who are working in the government sector were 6.19 times more likely to be wearing masks outside [aOR: 6.19; 95% (CI): (2.16, 17.76); Table 6].

Table 3) Attitude towards COVID-19 by demographic using Pearson Chi-square analysis

Table 4) Results of multiple logistic regression analysis on factors associated with attitude towards COVID-19

Table 5) Practice towards COVID-19 by demographic using Chi-square analysis

Table 6) Results of multiple logistic regression analysis on factors associated with practice towards COVID-19

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the respondents in North Borneo Malaysia, Sabah have adequate knowledge about the clinical presentations of the COVID-19 virus as well as the prevention and control of the virus. The result showed a similar correct rate for knowledge score at 84.2% with the previous study conducted in multiple regions in Malaysia [12]. The high knowledge score in this study may be due to the characteristics of the respondents, who were mostly highly educated. However, there were some misconceptions in our study and another study in which 75.6% of respondents believed that COVID-19 infection occurs through eating or contact with wild animals [13]. Although education level does not show a significant association with knowledge about the COVID-19 virus, several other studies conducted in China [11], the United Arab Emirates [14], Nepal [15], Indonesia [16], and a recent study in Malaysia [13] suggested that higher education level was associated with higher COVID-19 knowledge. We suggest that the educational awareness program for COVID-19 should focus on communities with lower education levels. The transition from pandemic to endemic status will take some time, and educating the public about the effects of COVID-19 as well as, harm reduction must be ongoing. It is recommended to emphasize educating the communities with lower education levels in North Borneo, such as those unable to use modern technology and those living in rural areas with limited network access. Educational programs should be more informative, interesting, and interactive to meet the level of understanding of the communities. Introducing social workers and health education officers as a facilitator in promoting education about COVID-19 to such communities would be beneficial as they are experts in behavior modification with cultural competencies. In addition, having COVID-19 survivors as part of the education program could improve the reachability of the programs, especially among the indigenous community in North Borneo.

Our study found that age, marital status, and occupation type are significantly associated with a higher average knowledge score on COVID-19. The results showed that both males and females have similar knowledge scores on COVID-19. Another study conducted in Indonesia also showed a similar finding that there was a significant difference in average knowledge score between age groups, marital status, education levels, and occupation types [16]. In the present study, the respondents aged 40 to 49 obtained the highest knowledge score compared to other age groups. The high rate of knowledge scores among the older generation groups in this study might be associated with the concerns that COVID-19 has a huge impact on the health of older people, especially those with comorbidities [17]. This suggests that older age groups are likely to have more health care concerns due to a higher risk of complications. However, other studies in Nepal and Bangladesh have shown that younger generations are more knowledgeable about COVID-19 compared to older generations [15, 18]. Therefore, any educational program related to COVID-19 should be focused on all age groups. More measures should also be done to address such misconceptions and misinformation with correct health information.

Based on the analysis, married people had a higher average knowledge score about COVID-19 compared to single/divorced people. Similar findings have been shown by other studies in China and North Sulawesi, Indonesia [19, 20]. Married respondents may want to know more about COVID-19 so they can protect their children and family members and make informed decisions. Moreover, the concept of individualism of the respondents could result in lower knowledge scores among the single respondents. A recent study showed that the more individualistic the participants, the higher the chance of non-compliance with epidemic prevention measures [21]. We suggest authorities foster and promote a collective mindset among single people regarding COVID-19 in creating safe environments, especially during the outbreak of COVID-19.

People who worked in the public sector showed a higher knowledge score about COVID-19. Recent studies that were also done in Malaysia and Ethiopia found that respondents that work in the public sector have high knowledge scores compared with unemployed respondents [13, 22]. Higher average knowledge scores among those who worked in the government sector may be attributed to the fact that government’s promotion towards strict Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) in the working place, especially during the MCO. It is also important to note that many efforts have been made by governments at all levels, such as public awareness campaigns on several media platforms conducted by the Ministry of Health. Results showed that unemployed respondents have the lowest knowledge score about COVID-19. A recent data collection showed that the majority of those suffering from their jobs in Sabah are people in low-income groups, and the unemployment that happens in Sabah is more severe rather than in other states in Malaysia [23]. It indicates that unemployed respondents know less about COVID-19 and focus on making financial stability. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected working hours, causing many people to lose their jobs, reduce total household income, and struggle to find new sources of income.

In this study, respondents who disagreed with the success of controlling the COVID-19 virus had significantly lower knowledge scores than those who agreed. A stream of similar studies in various countries among the general population on knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to COVID-19 depicted a higher knowledge score among those who reported a favorable attitude toward final success in controlling COVID-19 [24-27]. This study provides further empirical evidence of the prediction of higher knowledge scores, which is probably related to the feasible data collection method during the outbreak through an online survey where most of the online respondents are from the younger group with higher education who are students.

A survey during the same period of the present study [12] similarly reported a high score of knowledge and positive attitude towards successful outbreak control. Generally, the favorable attitude and high knowledge score towards COVID-19 [18, 26, 28-30] can probably be reflected by the ease of access to various sources of information as well as active and potentially skilled information seeking during the outbreak among the population of this study. Multiple logistic regression showed that as the knowledge score about COVID-19 increased, it was 1.35 more likely to have a positive attitude toward the eventual success in controlling the epidemic. According to a study on the relationship between COVID-19 information sources and attitudes in battling the pandemic, the Ministry of Health (MOH) was the most preferred source of information among respondents during the MCO in Malaysia [25]. The information by MOH Malaysia was instantaneously updated online through the official website and social media. Those who referred most to the official information were more likely to be confident that Malaysia could win the battle against COVID-19, which could be the reason this study witnessed similar high confidence in winning the COVID-19 battle. The optimism and confidence could also be related to strict SOP during the MCO along with the "flatten the curve" notion widely relayed during the initial phase of the outbreak. There was a strong hint of confidence in the Government of Malaysia when it comes to consistent SOP implementation and responses to contain COVID-19 [10].

Practice

In terms of information-seeking behavior, an obvious global increase in searching for COVID-19 information was also observed in Malaysia and was highly related to learning about recommended precautionary measures, with a clear increase in searches since the announcement of the first MCO, which was phasing through this survey period. Google Trend analysis showed that the searches were on the mask, hand sanitizer, and COVID-19 [31]. This could explain why the majority of respondents reported good compliance with COVID-19 preventive practices, where 98.1% (n=526) claimed not to have visited crowded places, which could be due to the recent implementation of the MCO. A total of 82.8% (444 people) wore masks whenever they went out in recent days. A study on new norm practice also reported high compliance with avoiding public gatherings, social distancing, hand hygiene, and mask-wearing. Fear of losing the job, income, and social life may also be a motivation for compliance [32]. The rate of wearing mask practice was significantly different in age groups, marital status, and occupation type. Based on the analysis, people who worked in the government sector were 6.19 times more likely to wear a mask outside than unemployed respondents. People in government sectors predicted high compliance in wearing masks, as they are usually the first adopters of any government measures [32].

According to the results of this study, health education programs and activities to improve the literacy of the people of Sabah state regarding COVID-19 should be done based on specific groups with more aggressiveness and creativity so that the information provided is acceptable by all levels of society in the state of Sabah.

There were three limitations of this study: First, this study was only conducted online and widely disseminated when the new COVID-19 pandemic hit Malaysia. Therefore this study cannot be conducted using a systematic sample population.

Secondly, since this study was conducted using a cross-sectional study method, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the population in the state of Sabah.

Thirdly, this study was self-administered. Therefore, the researcher cannot control all the answers filled in by the respondents in this study.

It is recommended to conduct qualitative studies at different levels of society and stakeholders to improve the quality of health education services in this country in the future.

Conclusion

The level of knowledge of the residents in Sabah, Malaysia, about COVID-19 is quite satisfactory. Meanwhile, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 differ according to the socio-demography of the population in Sabah.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Director General of Health, Ministry of Health, Malaysia, for approval to publish this article. Ethical Permission: Since this study was conducted during the early stages of the COVID-19 infection in Malaysia, ethical considerations did not apply. However, this study has received publication approval from the MALAYSIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contribution: Yunus SZSA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mohamed MH (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (40%); Fauzi MAM (Third Author), Discussion Writer (10%); Marimuthu G (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (5%); Anuar MFM (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (5%); Ithnain N (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Rahim SSSA (Seventh Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (5%)

Funding: None.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Literacy

Received: 2022/09/11 | Accepted: 2022/11/13 | Published: 2022/12/11

Received: 2022/09/11 | Accepted: 2022/11/13 | Published: 2022/12/11

References

1. World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) [Link]

2. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2022 Oct 15]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [Link]

3. Ministry of Health Malaysia. COVIDNOW [Internet]. Malaysia: Ministry Of Health Malaysia [cited 2022 Feb 3]. Available from: https://covidnow.moh.gov.my/ [Link]

4. Pfordten D, Ahmad R. Covid-19: Cases up by 2,875 bringing total to 384,688 [Internet]. Malaysia: The Star; 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/23/covid-19-current-situation-in-malaysia-updated-daily [Link]

5. Sazali MF, Rahim SSSA, Mohamed MH, Omar A, Pang NTP, Jeffree MS, et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Covid-19 among Students during the Early Phase of Pandemic in a University in Borneo, Malaysia. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(3):2122 [Link] [DOI:10.4081/jphr.2021.2122]

6. Prime Minister's Office of Malaysia. Movement control order: FAQ & Info [Internet]. Putrajaya: Prime Minister's Office of Malaysia, Official Website; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.pmo.gov.my/2020/03/movement-control-order-faq-info/ [Link]

7. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Movement Control Order (MCO) [Internet]. Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia [cited 2021 Feb 2021]. Available from: http://covid-19.moh.gov.my/faqsop/sop-perintah-kawalan-pergerakan-pkp [Link]

8. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Weekly epidemiological update and weekly operational update [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200304-sitrep-44-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=783b4c9d_2 [Link]

9. Lee M, You M. Psychological and behavioral responses in South Korea during the early stages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):2977. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17092977]

10. De Man J, Campbell L, Tabana H, Wouters E. The pandemic of online research in times of COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e043866. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043866]

11. Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745-52. [Link] [DOI:10.7150/ijbs.45221]

12. Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sern TJ, Ayub SH, Mohamad E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233668. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0233668]

13. Chai CS, Ng DL, Chua WJ, Tung YZ, Sindeh W, Ibrahim MA, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices among the general population during the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2022;15:389-401. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/RMHP.S349798]

14. Alremeithi HM, Alghefli AK, Almadhani R, Baynouna AlKetbi LM. Knowledge, attitude, and practices toward SARS-COV-2 infection in the United Arab Emirates population: An online community-based cross-sectional survey. Front Public Health. 2021;9:687628. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2021.687628]

15. Devkota HR, Sijali TR, Bogati R, Clarke A, Adhikary P, Karkee R. How does public knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors correlate in relation to COVID-19? A community-based cross-sectional study in Nepal. Front Public Health. 2021;8:589372. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2020.589372]

16. Muslih M, Susanti HD, Rias YA, Chung MH. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of Indonesian residents toward COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4473. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18094473]

17. Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017]

18. Ferdous MZ, Islam MS, Sikder MT, Mosaddek ASM, Zegarra-Valdivia JA, Gozal D. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: An online-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0239254. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0239254]

19. Cao J, Hu X, Cheng W, Yu L, Tu WJ, Liu Q. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 18 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):851-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00134-020-05987-7]

20. Simanjorang C, Tooy GC, Wuaten G, Pangandaheng N. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among North Sulawesi Indonesia residents. J Health Educ. 2021;6(2):57-64. [Link] [DOI:10.15294/jhe.v6i2.42869]

21. Maaravi Y, Levy A, Gur T, Confino D, Segal S. "The tragedy of the commons": How individualism and collectivism affected the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9:627559. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2021.627559]

22. Desalegn Z, Deyessa N, Teka B, Shiferaw W, Hailemariam D, Addissie A, et al. COVID-19 and the public response: Knowledge, attitude and practice of the public in mitigating the pandemic in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0244780. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0244780]

23. Nga JLH, Ramlan WK, Naim S. Covid-19 pandemic and unemployment in Malaysia: A case study from Sabah. Cosmop Civ Soci Interdiscip J. 2021;13(2):73-90. [Link] [DOI:10.5130/ccs.v13.i2.7591]

24. Masoud AT, Zaazouee MS, Elsayed SM, Ragab KM, Kamal EM, Alnasser YT, et al. KAP-COVIDGLOBAL: a multinational survey of the levels and determinants of public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e043971. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043971]

25. Mohamad E, Tham JS, Ayub SH, Hamzah MR, Hashim H, Azlan AA. Relationship between COVID-19 information sources and attitudes in battling the pandemic among the Malaysian public: Cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e23922. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/23922]

26. Sakr S, Ghaddar A, Sheet I, Eid AH, Hamam B. Knowledge, attitude and practices related to COVID-19 among young Lebanese population. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):653. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10575-5]

27. Siddiquea BN, Shetty A, Bhattacharya O, Afroz A, Billah B. Global epidemiology of COVID-19 knowledge, attitude and practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e051447 [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051447]

28. Adli I, Widyahening IS, Lazarus G, Phowira J, Baihaqi LA, Ariffandi B, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice related to the COVID-19 pandemic among undergraduate medical students in Indonesia: A nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262827. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0262827]

29. Al-Hussami M, El-Hneiti M, Bani Salameh A, Abu Sharour L, Al-Hussami R. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior toward COVID-19 among Jordanian residents during the quarantine period of the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021;16(4):1438-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2021.34]

30. Lee M, Kang BA, You M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(295):1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10285-y]

31. Lim JL, Ong CY, Xie B, Low LL. Estimating information seeking-behaviour of public in Malaysia during COVID-19 by using Google Trends. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27(5):202-4. [Link] [DOI:10.21315/mjms2020.27.5.16]

32. Ganasegeran K, Ch'ng ASH, Looi I. COVID-19 in Malaysia: Crucial measures in critical times. J Glob Health. 2020 Dec;10(2):020333. [Link] [DOI:10.7189/jogh.10.020333]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |