Volume 10, Issue 4 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(4): 827-833 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rahimi T, Faryabi R. Factors Predicting Prostate Cancer Screening Behavior in Iranian Men Based on the Protection Motivation Theory. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (4) :827-833

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-64056-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-64056-en.html

T. Rahimi1, R. Faryabi *2

1- Research Center for Social Determinants of Health, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Public Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Public Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 1374 kb]

(705 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (611 Views)

Full-Text: (132 Views)

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy in men and the fifth leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Studies have shown that in 2020, more than one million and 400.000 new cases of prostate cancer occurred, of which more than 375,000 cases led to death [2]. Although this figure is lower in Asian countries, including Iran, in recent years, the number of reports of patients has increased. Currently, prostate cancer in Iran is the third most common cancer in men and the sixth leading cause of death in all cancers [3].

Patients with prostate cancer need medication to relieve symptoms such as pain, bleeding, and urinary tract obstruction. Therefore, prostate cancer is also a major cause of pain and the cost of health care [4].

The main risk factors associated with prostate cancer have been reported in various studies, old age, race, and family history. In addition, there is evidence that lifestyle and diet, such as high-fat, low-fiber foods, and not eating fruits and vegetables, which are rich sources of vitamins and phytochemicals, increase the incidence of various cancers, including prostate cancer [5, 6].

Prostate cancer is a slow-growing disease, and in many patients, there are no serious warning signs, so the patient sees a doctor when he has advanced or metastasized to other parts of the body. Therefore, the diagnosis of the disease in the early stages has an important role in its monitoring and treatment [7].

The American Cancer Society and the American Urological Association recommend that men 50 years of age or older be tested annually for Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) serum and rectal examination for early detection of prostate cancer. Also, men at high risk for prostate cancer (including blacks and people with a strong family history) should be screened annually at age 40 because the cost of this screening is much less than the treatment of the disease after people get it [8]. In addition to individual and socio-cultural variables, some psychological variables such as beliefs, perceived risk, and attitudes toward being vulnerable to cancer play an important role in preventive behaviors such as cancer screening [9, 10].

The results of a study by Vapiwala et al. on Philadelphia residents show that while most participants acknowledge the importance of screening and early detection of prostate cancer, there are barriers such as misunderstanding of the cause of cancer, misinformation, insufficient knowledge, and distrust of physicians. Also, confusion over screening guidelines, religious barriers, fears, financial constraints, and access to service centers prevent screening behavior [11]. The results of a study by Adibe et al. on male university staff in Nigeria show that higher education and age are associated with knowledge about prostate cancer and that there is a positive attitude towards cancer screening and treatment in these individuals [12].

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) is a useful theoretical framework for predicting and performing early interventions in behaviors related to the prevention and early detection of cancer [13-15]. This theory was developed by Rogers in 1975 based on the theory of value expectation to explain the effects of fear on health attitudes and behaviors and that the effects of fear motivation have a significant effect on behavior choice [16]. This theory assumes that acceptance of recommended behavior health (protective behavior) is a direct result of a person's motivation to protect themselves. This theory explains the two processes of cognitive mediation, threat appraisal and coping appraisal, for protection motivation. To protect motivation to be called, perceived severity and vulnerability must overcome the rewards of maladaptive response (lack of self-protection), and perceived self-efficacy and perceived response efficacy must outweigh the costs of adaptive response (self-protection). Protection motivation is a mediating variable between the stages of threat appraisal, coping appraisal, and protective behavior [17].

Currently, there are limited studies on prostate cancer screening and its related factors, especially using behavioral theories. The available studies are more focused on the epidemiological factors and the men's knowledge or performance about this cancer [18-20]. Since little information is available regarding prostate cancer screening using theoretical frameworks, the purpose of this study was to investigate factors related to prostate cancer screening in Iranian men based on PMT.

Instruments and Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional study that was performed to investigate the factors associated with prostate cancer screening in men over 50 years of age in Jiroft, Iran using the PMT in 2018.

The statistical population included all men over 50 years old in Jiroft who were selected according to the sample size and random sampling method. Sampling was performed using a multi-stage method (stratified and random). In this way, at first, all six health centers of Jiroft were considered six stratums. Then from each stratum, 70 participants were selected randomly from the files in the health centers. Finally, a total of 414 people were included in the study. Inclusion criteria included literacy, living in Jiroft, not having prostate cancer at present, and willingness to participate in the study.

In this study, a researcher-made questionnaire was used, which consisted of 2 parts. The first part contained demographic characteristics with 8 items (age, marital status, occupation, education, income status, history of exposure to chemicals), general health status with 8 items, and family history of cancer with 5 items. The second part included items related to the constructs of PMT, including subscales of protective behavior (1 item), perceived severity (5 items), perceived vulnerability (5 items), fear (3 items), perceived response efficiency (6 items), self-efficacy (4 items), response cost (6 items), perceived rewards (2 items) and motivation to protect (5 items). The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Thus, considering the 5-point Likert scale with options from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree", each item is assigned a score between 1 and 5. Perceived severity and perceived vulnerability score was between 5-25, fear score between 3-15, perceived response efficiency score between 6-30, self-efficacy score between 4-20, response cost score between 6-30, perceived rewards scored between 2-10, and protection motivation from 5-25.

The validity of the questionnaire was done by measuring the content validity indices (CVR and CVI) and using the opinions obtained from the panel of experts (7 health education specialists and 2 general practitioners), and the numbers obtained for CVR and CVI were 0.87 and 0.83, respectively. Finally, Cronbach's alpha calculation method was used to assess the reliability of the questionnaire for the constructs of protection motivation (0.75), self-efficacy (0.70), perceived vulnerability (0.88), response cost (0.80), response efficiency (0.85), perceived severity (0.71), perceived reward (0.89), and fear (0.76). In the implementation phase, the trained interviewer was deployed in selected health centers, and the objectives of the study were explained to participants. Informed consent was obtained from parent of participants, and then questionnaire was provided to them, and enough time was considered to complete it.

Data were analyzed by SPSS 18 software using one-way ANOVA and independent t-test to determine the relationship between behavior and demographic variables, Pearson correlation to determine the relationship between prostate cancer screening behavior and other PMT constructs, and linear regression to predict behavior changes at a significance level of 0.05.

Findings

53.9% of the subjects were in the age group of 60-69 years old. The occupation of the majority (29.2%) was farming, and 65.4% were a diploma or less. Most participants (83.8%) were married, and 55.3% had farm experience. The monthly income of 64% of men participating in the study was 2 million Tomans or less (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between demographic variables and prostate cancer screening behavior (p>0.05).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of participants' demographic variables (n=414)

Most men over 50 years in Jiroft (75.6%) reported their health status well. Only 11.8% smoked. 95.7% had at least one share of daily consumption of fruits and vegetables. 93.5% of people had seen a doctor in the past year and, a history of other screenings was reported in 24.4%. Most people (94.7%) went to the doctor only at the time of illness, and 60.1% reported a history of an underlying disease. Only 12.3% of the participant’s family members had a history of some type of cancer, and only 22.9% had information about prostate cancer (Table 2).

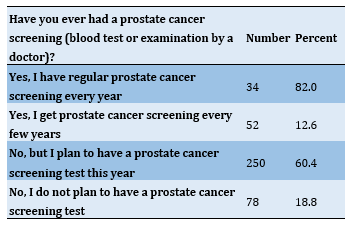

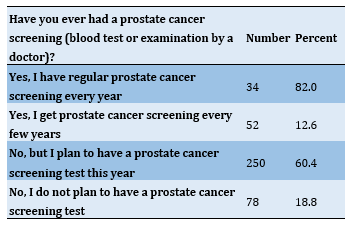

Only 8.2% of subjects reported regular annual prostate cancer screening, and 60.4% said they planned to do so this year (Table 3).

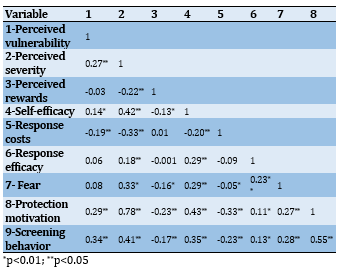

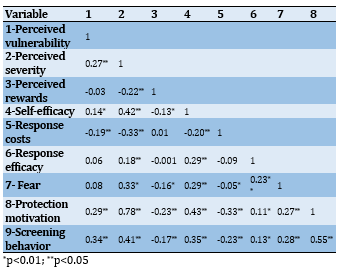

Perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, response efficiency, fear and protection motivation had a significant positive correlation, and the response cost and perceived rewards had a significant inverse relationship with prostate cancer screening behavior (p<0.05; Table 4).

Table 2) General health status of participants (n=414)

Table 3) Prostate cancer screening behavior in participants (n=414)

Perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and protection motivation constructs could explain 37% of the variance of prostate cancer screening behavior (p<0.05; Table 5).

Table 4) Correlation matrix between prostate cancer screening behavior and PMT constructs

Table 5) Results of linear regression to predict prostate cancer screening behavior based on the structures of Protection Motivation Theory

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that only 8.2% of people reported regular and annual PSA performance, which is similar to the results obtained by Nderitu et al. in men over 40 years old in London [21]. Scientific evidence in other studies also show that most men are reluctant to take PSA, unless they have problems with their urinary system and their doctor says they should. A study by Morrison et al. showed that although prostate cancer is common in Jamaica, screening rates are low in the male population, and only older men with problems are more likely to be screened [22]. Because screening is an early method of diagnosing cancers, early population intervention seems necessary.

The findings of our study showed that the constructs of perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and protection motivation could explain 37% of the PSA variance, and protection motivation was a stronger predictor. There are other studies that show that the constructs of PMT can predict cancer screening behaviors. For example, the results of a study by Rahaei et al., which examined the predictors of early detection of cancers in the over-20 population of Yazd in Iran, showed that self-efficacy, perceived severity, rewards, and protection motivation explain 9.6% of the changes in screening behavior [14]. The results of a study by Vadaparampil et al. also showed that demographic factors such as age and income, as well as health beliefs such as perceived self-efficacy, are important predictors of prostate cancer screening behavior and, in contrast to our study, perceived vulnerability and severity were not significant with prostate cancer screening behavior [23]. In some studies, with other behavioral models that have common constructs with PMT, behavioral predictor constructs regarding PSA have been mentioned. A study by Abuadas et al. using the Health Belief Model show that only 13% of Jordanian men in the past decade underwent PSA, and the likelihood of participating in prostate cancer screening was higher in Jordanian men with higher levels of perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and health motivation as well as lower levels of barriers to PSA. Among demographic variables, family history, urinary symptoms, age, and awareness of prostate cancer, significantly predicted participation in prostate cancer screening [20].

In the present study, protection motivation was the most important predictor of behavior. Protection motivation or intention is an important mediator for performing a behavior in studies predicting cancer screening behaviors that are influenced by various factors such as past information from doctors that one has any prostate disease, perceived general health, and perceived threat [24]. Therefore, during educational interventions, strategies should be developed that affect the other factors affecting protection motivation and can increase the number of referrals for prostate cancer screening.

Perceived vulnerability and perceived severity constructs were two other predictors of behavior. Scientific evidence shows that when people perceive a disease as dangerous, that is, consider themselves vulnerable to the disease and take its consequences seriously, their adherence to screening programs will be greater [25]. The results of an educational intervention by Zare et al. also emphasize sensitizing the development of asymptomatic cancer and reminding participants of the serious complications and chronic nature of prostate cancer, along with problems caused by the disease, such as high treatment costs, which can increase participants' perceived vulnerability and severity levels and through this, affect PSA performance [26].

Our study findings showed that fear is also an important factor in predicting PSA. It means that people who are more afraid of prostate cancer are more likely to get PSA. Although the findings of some other studies confirm that the fear of most people is associated with the frequency of screening [27], however, Patel et al. note that fear of a positive cancer diagnosis could be an important barrier to prostate cancer screening in African American men [28]. Brown et al. suggest that by addressing prostate cancer concerns in men with urinary tract problems and informing these men of the true threat of prostate cancer, many of the discomforts associated with their symptoms may be alleviated and encouraged to use medicine services in this area [29].

Self-efficacy was the last predictor of PSA in the participants of the present study, which is similar to the findings of other studies [14, 23]. Therefore, health-promoting interventions need to focus on creating men's beliefs to ensure their ability to overcome anxiety, fear, existing psychological or physical barriers to PSA, and regular annual visits. Role modeling by men with or without urinary tract problems who previously had PSA can also be helpful.

The strength of the current study is using a theoretical framework to investigate screening behavior among men as the target group, who are less studied in health researches. Also the instrument of this study can be a suitable framework for implementing educational interventions. The limitations of the present study were the completion of questionnaires by the self-report method. Longitudinal studies can be used in other populations instead of cross-sectional studies to study causal relationships.

Due to the low level of prostate cancer screening behavior in the study population, the extensive educational interventions in Jiroft is necessary. For the success of intervention programs, strategies that strengthen the structures of vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and motivation to perform behavior should be emphasized.

Conclusion

The constructs of perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and protection motivation can explain 37% of the PSA variance, and protection motivation is a stronger predictor.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their gratitude to all those who assisted us in conducting this study and the participants for their contribution to filling out the questionnaires.

Ethical Permission: The protocol of study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences with code IR.JMU.REC.1396.037.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Rahimi T (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Faryabi R (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (50%)

Funding: This work has been financially supported by the research deputy of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences.

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy in men and the fifth leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Studies have shown that in 2020, more than one million and 400.000 new cases of prostate cancer occurred, of which more than 375,000 cases led to death [2]. Although this figure is lower in Asian countries, including Iran, in recent years, the number of reports of patients has increased. Currently, prostate cancer in Iran is the third most common cancer in men and the sixth leading cause of death in all cancers [3].

Patients with prostate cancer need medication to relieve symptoms such as pain, bleeding, and urinary tract obstruction. Therefore, prostate cancer is also a major cause of pain and the cost of health care [4].

The main risk factors associated with prostate cancer have been reported in various studies, old age, race, and family history. In addition, there is evidence that lifestyle and diet, such as high-fat, low-fiber foods, and not eating fruits and vegetables, which are rich sources of vitamins and phytochemicals, increase the incidence of various cancers, including prostate cancer [5, 6].

Prostate cancer is a slow-growing disease, and in many patients, there are no serious warning signs, so the patient sees a doctor when he has advanced or metastasized to other parts of the body. Therefore, the diagnosis of the disease in the early stages has an important role in its monitoring and treatment [7].

The American Cancer Society and the American Urological Association recommend that men 50 years of age or older be tested annually for Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) serum and rectal examination for early detection of prostate cancer. Also, men at high risk for prostate cancer (including blacks and people with a strong family history) should be screened annually at age 40 because the cost of this screening is much less than the treatment of the disease after people get it [8]. In addition to individual and socio-cultural variables, some psychological variables such as beliefs, perceived risk, and attitudes toward being vulnerable to cancer play an important role in preventive behaviors such as cancer screening [9, 10].

The results of a study by Vapiwala et al. on Philadelphia residents show that while most participants acknowledge the importance of screening and early detection of prostate cancer, there are barriers such as misunderstanding of the cause of cancer, misinformation, insufficient knowledge, and distrust of physicians. Also, confusion over screening guidelines, religious barriers, fears, financial constraints, and access to service centers prevent screening behavior [11]. The results of a study by Adibe et al. on male university staff in Nigeria show that higher education and age are associated with knowledge about prostate cancer and that there is a positive attitude towards cancer screening and treatment in these individuals [12].

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) is a useful theoretical framework for predicting and performing early interventions in behaviors related to the prevention and early detection of cancer [13-15]. This theory was developed by Rogers in 1975 based on the theory of value expectation to explain the effects of fear on health attitudes and behaviors and that the effects of fear motivation have a significant effect on behavior choice [16]. This theory assumes that acceptance of recommended behavior health (protective behavior) is a direct result of a person's motivation to protect themselves. This theory explains the two processes of cognitive mediation, threat appraisal and coping appraisal, for protection motivation. To protect motivation to be called, perceived severity and vulnerability must overcome the rewards of maladaptive response (lack of self-protection), and perceived self-efficacy and perceived response efficacy must outweigh the costs of adaptive response (self-protection). Protection motivation is a mediating variable between the stages of threat appraisal, coping appraisal, and protective behavior [17].

Currently, there are limited studies on prostate cancer screening and its related factors, especially using behavioral theories. The available studies are more focused on the epidemiological factors and the men's knowledge or performance about this cancer [18-20]. Since little information is available regarding prostate cancer screening using theoretical frameworks, the purpose of this study was to investigate factors related to prostate cancer screening in Iranian men based on PMT.

Instruments and Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional study that was performed to investigate the factors associated with prostate cancer screening in men over 50 years of age in Jiroft, Iran using the PMT in 2018.

The statistical population included all men over 50 years old in Jiroft who were selected according to the sample size and random sampling method. Sampling was performed using a multi-stage method (stratified and random). In this way, at first, all six health centers of Jiroft were considered six stratums. Then from each stratum, 70 participants were selected randomly from the files in the health centers. Finally, a total of 414 people were included in the study. Inclusion criteria included literacy, living in Jiroft, not having prostate cancer at present, and willingness to participate in the study.

In this study, a researcher-made questionnaire was used, which consisted of 2 parts. The first part contained demographic characteristics with 8 items (age, marital status, occupation, education, income status, history of exposure to chemicals), general health status with 8 items, and family history of cancer with 5 items. The second part included items related to the constructs of PMT, including subscales of protective behavior (1 item), perceived severity (5 items), perceived vulnerability (5 items), fear (3 items), perceived response efficiency (6 items), self-efficacy (4 items), response cost (6 items), perceived rewards (2 items) and motivation to protect (5 items). The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Thus, considering the 5-point Likert scale with options from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree", each item is assigned a score between 1 and 5. Perceived severity and perceived vulnerability score was between 5-25, fear score between 3-15, perceived response efficiency score between 6-30, self-efficacy score between 4-20, response cost score between 6-30, perceived rewards scored between 2-10, and protection motivation from 5-25.

The validity of the questionnaire was done by measuring the content validity indices (CVR and CVI) and using the opinions obtained from the panel of experts (7 health education specialists and 2 general practitioners), and the numbers obtained for CVR and CVI were 0.87 and 0.83, respectively. Finally, Cronbach's alpha calculation method was used to assess the reliability of the questionnaire for the constructs of protection motivation (0.75), self-efficacy (0.70), perceived vulnerability (0.88), response cost (0.80), response efficiency (0.85), perceived severity (0.71), perceived reward (0.89), and fear (0.76). In the implementation phase, the trained interviewer was deployed in selected health centers, and the objectives of the study were explained to participants. Informed consent was obtained from parent of participants, and then questionnaire was provided to them, and enough time was considered to complete it.

Data were analyzed by SPSS 18 software using one-way ANOVA and independent t-test to determine the relationship between behavior and demographic variables, Pearson correlation to determine the relationship between prostate cancer screening behavior and other PMT constructs, and linear regression to predict behavior changes at a significance level of 0.05.

Findings

53.9% of the subjects were in the age group of 60-69 years old. The occupation of the majority (29.2%) was farming, and 65.4% were a diploma or less. Most participants (83.8%) were married, and 55.3% had farm experience. The monthly income of 64% of men participating in the study was 2 million Tomans or less (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between demographic variables and prostate cancer screening behavior (p>0.05).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of participants' demographic variables (n=414)

Most men over 50 years in Jiroft (75.6%) reported their health status well. Only 11.8% smoked. 95.7% had at least one share of daily consumption of fruits and vegetables. 93.5% of people had seen a doctor in the past year and, a history of other screenings was reported in 24.4%. Most people (94.7%) went to the doctor only at the time of illness, and 60.1% reported a history of an underlying disease. Only 12.3% of the participant’s family members had a history of some type of cancer, and only 22.9% had information about prostate cancer (Table 2).

Only 8.2% of subjects reported regular annual prostate cancer screening, and 60.4% said they planned to do so this year (Table 3).

Perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, response efficiency, fear and protection motivation had a significant positive correlation, and the response cost and perceived rewards had a significant inverse relationship with prostate cancer screening behavior (p<0.05; Table 4).

Table 2) General health status of participants (n=414)

Table 3) Prostate cancer screening behavior in participants (n=414)

Perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and protection motivation constructs could explain 37% of the variance of prostate cancer screening behavior (p<0.05; Table 5).

Table 4) Correlation matrix between prostate cancer screening behavior and PMT constructs

Table 5) Results of linear regression to predict prostate cancer screening behavior based on the structures of Protection Motivation Theory

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that only 8.2% of people reported regular and annual PSA performance, which is similar to the results obtained by Nderitu et al. in men over 40 years old in London [21]. Scientific evidence in other studies also show that most men are reluctant to take PSA, unless they have problems with their urinary system and their doctor says they should. A study by Morrison et al. showed that although prostate cancer is common in Jamaica, screening rates are low in the male population, and only older men with problems are more likely to be screened [22]. Because screening is an early method of diagnosing cancers, early population intervention seems necessary.

The findings of our study showed that the constructs of perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and protection motivation could explain 37% of the PSA variance, and protection motivation was a stronger predictor. There are other studies that show that the constructs of PMT can predict cancer screening behaviors. For example, the results of a study by Rahaei et al., which examined the predictors of early detection of cancers in the over-20 population of Yazd in Iran, showed that self-efficacy, perceived severity, rewards, and protection motivation explain 9.6% of the changes in screening behavior [14]. The results of a study by Vadaparampil et al. also showed that demographic factors such as age and income, as well as health beliefs such as perceived self-efficacy, are important predictors of prostate cancer screening behavior and, in contrast to our study, perceived vulnerability and severity were not significant with prostate cancer screening behavior [23]. In some studies, with other behavioral models that have common constructs with PMT, behavioral predictor constructs regarding PSA have been mentioned. A study by Abuadas et al. using the Health Belief Model show that only 13% of Jordanian men in the past decade underwent PSA, and the likelihood of participating in prostate cancer screening was higher in Jordanian men with higher levels of perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and health motivation as well as lower levels of barriers to PSA. Among demographic variables, family history, urinary symptoms, age, and awareness of prostate cancer, significantly predicted participation in prostate cancer screening [20].

In the present study, protection motivation was the most important predictor of behavior. Protection motivation or intention is an important mediator for performing a behavior in studies predicting cancer screening behaviors that are influenced by various factors such as past information from doctors that one has any prostate disease, perceived general health, and perceived threat [24]. Therefore, during educational interventions, strategies should be developed that affect the other factors affecting protection motivation and can increase the number of referrals for prostate cancer screening.

Perceived vulnerability and perceived severity constructs were two other predictors of behavior. Scientific evidence shows that when people perceive a disease as dangerous, that is, consider themselves vulnerable to the disease and take its consequences seriously, their adherence to screening programs will be greater [25]. The results of an educational intervention by Zare et al. also emphasize sensitizing the development of asymptomatic cancer and reminding participants of the serious complications and chronic nature of prostate cancer, along with problems caused by the disease, such as high treatment costs, which can increase participants' perceived vulnerability and severity levels and through this, affect PSA performance [26].

Our study findings showed that fear is also an important factor in predicting PSA. It means that people who are more afraid of prostate cancer are more likely to get PSA. Although the findings of some other studies confirm that the fear of most people is associated with the frequency of screening [27], however, Patel et al. note that fear of a positive cancer diagnosis could be an important barrier to prostate cancer screening in African American men [28]. Brown et al. suggest that by addressing prostate cancer concerns in men with urinary tract problems and informing these men of the true threat of prostate cancer, many of the discomforts associated with their symptoms may be alleviated and encouraged to use medicine services in this area [29].

Self-efficacy was the last predictor of PSA in the participants of the present study, which is similar to the findings of other studies [14, 23]. Therefore, health-promoting interventions need to focus on creating men's beliefs to ensure their ability to overcome anxiety, fear, existing psychological or physical barriers to PSA, and regular annual visits. Role modeling by men with or without urinary tract problems who previously had PSA can also be helpful.

The strength of the current study is using a theoretical framework to investigate screening behavior among men as the target group, who are less studied in health researches. Also the instrument of this study can be a suitable framework for implementing educational interventions. The limitations of the present study were the completion of questionnaires by the self-report method. Longitudinal studies can be used in other populations instead of cross-sectional studies to study causal relationships.

Due to the low level of prostate cancer screening behavior in the study population, the extensive educational interventions in Jiroft is necessary. For the success of intervention programs, strategies that strengthen the structures of vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and motivation to perform behavior should be emphasized.

Conclusion

The constructs of perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, self-efficacy, fear, and protection motivation can explain 37% of the PSA variance, and protection motivation is a stronger predictor.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their gratitude to all those who assisted us in conducting this study and the participants for their contribution to filling out the questionnaires.

Ethical Permission: The protocol of study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences with code IR.JMU.REC.1396.037.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Rahimi T (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Faryabi R (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (50%)

Funding: This work has been financially supported by the research deputy of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2022/09/7 | Accepted: 2022/11/13 | Published: 2022/11/30

Received: 2022/09/7 | Accepted: 2022/11/13 | Published: 2022/11/30

References

1. Rawla P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J Oncol. 2019;10(2):63-89. [Link] [DOI:10.14740/wjon1191]

2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49 [Link] [DOI:10.3322/caac.21660]

3. Pakzad R, Rafiemanesh H, Ghoncheh M, Sarmad A, Salehiniya H, Hosseini S, et al. Prostate cancer in Iran: Trends in incidence and morphological and epidemiological characteristics. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(2):839-43. [Link] [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.2.839]

4. Catalona WJ, Loeb S. Prostate cancer screening and determining the appropriate prostate-specific antigen cutoff values. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8(2):265-70. [Link] [DOI:10.6004/jnccn.2010.0017]

5. Leitzmann MF, Rohrmann S. Risk factors for the onset of prostatic cancer: age, location, and behavioral correlates. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:1-11. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/CLEP.S16747]

6. Tabari F, Zakeri Moghadam M, Bahrani N, Monjamed Z. Evaluation of the Quality of Life in newly recognized cancer patients. Hayat. 2007; 13(2): 5-12. [Persian] [Link]

7. Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Ward E, Ferlay J, Brawley O, et al. International variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol. 2012;61(6):1079-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.054]

8. Hankey BF, Feuer EJ, Clegg LX, Hayes RB, Legler JM, Prorok PC, et al. Cancer surveillance series: interpreting trends in prostate cancer-part I: Evidence of the effects of screening in recent prostate cancer incidence, mortality, and survival rates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(12):1017-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jnci/91.12.1017]

9. Meyerowitz BE, Richardson J, Hudson S. Ethnicity and cancer outcomes: Behavioral and psychosocial considerations. Psychol Bull. 1998;123(1):47-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.47]

10. McDavid K, Melnik TA, Derderian H. Prostate cancer screening trends of New York state men at least 50 years of age 1994 -1997. Prev Med. 2000;31(3):195-202. [Link] [DOI:10.1006/pmed.2000.0709]

11. Vapiwala N, Miller D, Laventure B, Woodhouse K, Kelly S, Avelis, et al. Stigma, beliefs and perceptions regarding prostate cancer among Black and Latino men and women. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1);758. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10793-x]

12. Adibe MO, Aluh DO, Isah A, Anosike C. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of prostate cancer among male staff of the University of Nigeria. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(7):1961-6. [Link]

13. Inukai S, Ninomiya K. Cognitive factors relating to mammographic breast cancer screening. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2010;57(9):796-806. [Japanese] [Link]

14. Rahaei Z, Ghofranipour F, Morowatisharifabad MA, Mohammadi E. Determinants of cancer early detection behaviors:application of protection motivation theory. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5(2):138-46. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2015.016]

15. Asadi Z, Abdi N, Miri S, Safari A. Predictors of behavioral intention for pap smear testing based on the theory of protection motivation in women. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;10(3):427-31. [Link]

16. Milne S, Sheeran P, Orbell SH. Prediction and intervention in health- related behavior: a meta- analytic review of protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(1):106-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02308.x]

17. Floyd DL, Prentic- Dunn S, Rogers RW. A meta- analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(2):407-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x]

18. Makado E, Makado RK, Rusere MT. An assessment of knowledge of and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening among men aged 40 to 60 years at Chitungwiza Central Hospital in Zimbabwe. Int J Hum Soc Stud. 2015;3(4):45-55. [Link]

19. Tasian GE, Cooperberg MR, Cowan JE, Keyashian K, Greene KL, Daniels NA, et al. Prostate specific antigen screening for prostate cancer: knowledge of, attitudes towards, and utilization among primary care physicians. Urol Oncol. 2012;30(2):155-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.12.019]

20. Abuadas MH, Petro-Nustas W, Albikawi ZF. Predictors of participation in prostate cancer screening among older men in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(13):5377-83. [Link] [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.13.5377]

21. Nderitu P, Van Hemelrijck M, Ashworth M, Mathur R, Hull S, DudekA, et al. Prostate-specific antigen testing in inner London general practices: are those at higher risk most likely to get tested? BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011356. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011356]

22. Morrison BF, Aiken W, Mayhew R, Gordon Y, Reid M. Prostate cancer screening in Jamaica: Results of the largest national screening clinic. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;2016:2606805. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2016/2606805]

23. Vadaparampil ST, Jacobsen PB, Iryna SKK, Saloup WR, Pow-Sang J. Factors predicting prostate specific antigen testing among first-degree relatives of prostate cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(5):753-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.753.13.5]

24. Muliira JK, Al-Saidi HS, Al-Yahyai AN. Determinants of behavioral intentions to screen for prostate cancer in Omani men. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017;4(4):348-55. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/apjon.apjon_34_17]

25. Matthew AG, Paradisco C, Currie KL, Finelli A. Examining risk perception among men with family history of prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):251-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2010.11.020]

26. Zare M, Ghodsbin F, Jahanbin I, Ariafar A, Keshavarzi S, Izadi T. The effect of health belief model-based education on knowledge and prostate cancer screening behaviors: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2016;4(1):57-68. [Link]

27. Consedine NS, Morgenstern AH, Kudadjie-Gyamfi E, Magai C, Neugut AI. Prostate cancer screening behavior in men from seven ethnic groups: the fear factor. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):228-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0019]

28. Patel K, Kenerson D, Wang H, Brown B, Pinkerton H, Burress M, et al. Factors influencing prostate cancer screening in low-income African Americans in Tennessee. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1 Suppl):114-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1353/hpu.0.0235]

29. Brown CT, O'Flynn E, Van Der Meulen J, Newman S, Mundy AR, Emberton M. The fear of prostate cancer in men with lower urinary tract symptoms: should symptomatic men be screened? BJU Int. 2003;91(1):30-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04013.x]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |