Volume 10, Issue 2 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(2): 323-332 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Diorditsa I, Katerynchuk K, Kyrenko S, Vasylkivska I, Bespal O. Interpretation of “Health”, “Pain” and “Suffering” Concepts in Modern Multidisciplinary Sciences. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (2) :323-332

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61545-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61545-en.html

1- Department of Private and Public Law, Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design, Kyiv, Ukraine

2- Department of Law, Kyiv National Linguistic University, Kyiv, Ukraine

3- Department of Constitutional, Administrative and Criminal Law, Kyiv National Economic University named after Vadym Hetman, Kyiv, Ukraine

2- Department of Law, Kyiv National Linguistic University, Kyiv, Ukraine

3- Department of Constitutional, Administrative and Criminal Law, Kyiv National Economic University named after Vadym Hetman, Kyiv, Ukraine

Full-Text [PDF 765 kb]

(873 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (693 Views)

Full-Text: (191 Views)

Introduction

The formation and effective implementation of state policy in criminal law protection of an individual's health is necessary for ensuring human rights and freedoms in Ukraine. In the globalization of criminal offenses against an individual’s health, the world’s leading countries' governments are focusing more and more on the creation and improvement of effective mechanisms of criminal law counteraction to encroachment on an individual’s health. Ukraine is entering a new era of the global information society, which requires the full provision of human rights and freedoms. In this era, anthropocentrism should become a priority in state policy. The implementation of national interests in strengthening criminal law protection of a person’s health is clear evidence that anthropocentrism is the main basis of the most important areas of such state transformation. Some aspects of the problematic issues of forming an understanding, such concepts as “health”, “pain” and “suffering” in one way or another have been studied in the scientific works of researchers that we will be mentioned below. However, these studies revealing some aspects of criminal offenses against the health of an individual, leave a range of issues in this field that is not examined in detail [1].

The collective monograph “Prevention of Tortures” [2] covers international standards for preventing tortures, inhuman treatment, lowering dignity, or punishment in detail. The classification of international documents, existing in human rights is proposed: by content, scope, and legal force. Thus, Chervyatsova states: “… every violation of human rights contains an element of lowering human dignity and every violation leads to negative consequences, physical and spiritual suffering for injured people” [2]. We do not agree with such a statement since, firstly, pain and suffering are the consequences of torture as stipulated in Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] and international acts; secondly, at first the author states that torture contains elements of lowering human dignity, then – it is the form of inhuman treatment leading to severe suffering [2]. Article 3 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms stipulates the absolute prohibition of torture or inhuman treatment, lowering human dignity, or punishment. Therefore, these concepts are independent, separate from each other, but at the same time, closely related.

In 2013, Telesnitskyi [4] analyzed the theoretical and methodological grounds for comparative legal research and the genesis of criminal liability for torture. Moreover, he provided criminal law of torture's objective and subjective features under the laws of Ukraine and foreign countries, comparative characteristics of qualifying torture features, and analyzed the problems of sanctions. Denisova analyzed the terminology widely used in the Constitution of Ukraine as well as providing the author’s definition of torture [5].

Grishchenko [6] provided a comprehensive criminal law characteristic of battery and torment (objective and subjective features of the criminal offense provided in the description of Article 126 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, and its qualifying features) and proposed to expand the content of the criminal offense object provided by the description of Article 126 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, namely: an additional direct object can be person’s honor and dignity. In our opinion, the following issues remain controversial: first, the provision that this composition of the criminal offense is formal in terms of the objective structure; second, proposals to determine the special subject among qualifying features of the criminal offense composition, as well as to determine the composition of the subject of this criminal offense composition – father, mother, stepfather, stepmother, custodian or trustee, the person authorized to upbring or take care about him or her. Today, not only this criminal offense is often committed in the family area, but also other criminal offenses against the health of an individual, so, according to the author’s reasoning, it is necessary to separate special subject of a criminal offense in each article. These suggestions aggravate this article, not considering that in case of sentencing, the court will take into account the provisions of Paragraph 6, Part 1, Article 67 “Aggravating Circumstances” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3]. Dissertation of Lakhova [7] “Criminal Liability for Causing Intentional Minor Injuries, Battery, Torment” contains insufficiently justified provision of the author; the phrase “harm to health” used by the author in interpreting the concept “body injury” contradicts its content, “suffering caused to a person due to physical or mental exposure; deterioration or deprivation of opportunities to exercise his or her habits or wishes by a person.

In the textbook “Criminal Liability for Torture in Ukraine and foreign countries” [8] the authors identified the peculiarities of objective and subjective features of torture criminal offense composition provided by the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] and the Criminal Codes of other countries. Theoretical foundations and genesis of criminal liability for torture are studied, and the social conditionality of criminal liability for torture is described (the following factors are distinguished: international law, national law, criminological, and socio-psychological factors). The authors emphasize that torture – a criminal offense, is materially defined. The textbook pays considerable attention to legally defined torture methods (battery, excruciation, and other violent acts). Still, the consequences being a mandatory feature of the objective part of such criminal offense composition are briefly described in work.

The purpose of the article was to consider the problematic issues of forming an understanding of such concepts as health, pain, and suffering.

Information and Methods

The work used a set of general scientific and special methods to achieve the goals and solve the scientific tasks. The dialectical method was used in all parts of the work, which provided an analysis of the components of area-specific (criminal law) characteristics of illegal consequences (physical pain, physical and moral suffering). Dogmatic and hermeneutic methods ensured the content interpretation of concepts and terms to clarify the categories of national criminal, international humanitarian law, and other sciences to compare the concepts. The comparative legal method allowed identifying the advantages and disadvantages inherent to the legal norms of national legislation compared with the relevant provisions of the legislation of foreign countries; the statistic method contributed to the development of the empirical base as a source of data about the subject of research; sociological methods were applied during the survey of forensic experts of general profile and judges – summary data of surveys of judges and forensic experts of the general profile from different regions of Ukraine except from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk region from October 2018 to May 2019.

The questionnaire aims to clarify the opinion of court employees and forensic experts of general profile concerning the condition of criminal law protection of person’s health from illegal encroachments in Ukraine, as well as to use the results obtained in formulating conclusions and developing practical proposals. The category of the respondents interviewed included: 114 court employees and 272 forensic experts of general profile. The questionnaire form was written by filling in/giving answers by respondents. The content of the proposed questions is determined by the content of the scientifically substantiated conclusions obtained in the article that can be refuted, confirmed, or clarified in the process of questioning. The peculiarity of the proposed answer options is that a simplified approach was used, including the following: the respondent chose one of the three answers already formulated (“yes”, “no”, “difficult to define”). The questions were formulated in the written questionnaire offered to the respondents to obtain the most accurate, reasonable, and logical answers. At the same time, the respondents needed practical experience and relevant professional skills that are valuable in scientific terms.

Among the global objectives of sustainable development for 2015-2030, it is mentioned under number 3: Strong health and well-being [9]. However, the terminology used is controversial. First, the prerequisite is that “health” as a category is studied in medical science and widely used in law science. Thus, Section II is in the Special Part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (hereinafter – the CC of Ukraine). “Criminal offenses against the life and health of an individual” contains Articles 121-128, 130, 133 in which the object is “social relations in the field of protection of human rights and freedoms against illegal encroachments that cause or may cause harm to the heal of an individual” [10]. The study of criminal law science proves that “health” as a category has not been studied in detail, and the legal acts of Ukraine do not contain its definition. For instance, in the Criminal Code of Ukraine Article, such task as “legal support of protection of rights and freedoms of a person and a citizen” is defined. This provision is supported by the Constitution of Ukraine [11] in Articles 3, 27, 28, 35, 49, which guarantee that a person, his or her life and health, honor and dignity, inviolability, and security are recognized as the highest social value. Everyone has the right to protect his or her life and health, lives, and health of other people from illegal encroachment. No one can be subjected to torture, inhuman treatment, lowering human dignity, or punishment. Everyone has the right to freedom of worldview and religion. Everyone has the right to health care, medical aid, and insurance.

All these values and other ones are enshrined in the provisions of the Basic Law of Ukraine, as well as they meet the provisions of international treaties ratified by Ukraine but do not contain the definition of “health”. Only in the preamble of the Charter of the World Health Organization (from now on – WHO) the definition of “health” is given, which was later reflected in the Law of Ukraine “Fundamentals of Ukrainian legislation on health care” [12]. Thus, “health” is the condition of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of diseases or infirmity [13]. The definition of “health” mentioned in the preamble of the WHO Charter and the Law of Ukraine “Fundamentals of Ukrainian legislation on health care” is controversial to some extent. First, the concept of social well-being is subjective, too broad, and requires a clear definition. Second, a person’s full social value is not always characterized by quantitative criteria and his or her biological condition. Third, according to this definition, it is almost impossible to find a healthy person [14].

Findings

As a result of the study of the “health” definition, scientists in the field of criminal law have concluded that this concept has been studied in the medical aspect more thoroughly. At the same time, there are some discussions concerning this issue since “heath” is a dynamic category constantly improving. Moreover, “person’s health has been under criminal law protection from the moment of starting the child-birth to the onset of biological death” [15], so, taking into account this definition, from the very beginning of life, not considering other mandatory components. From birth, a live-born, viable person possesses health. Therefore, these categories of “life” and “health” have the same initial stage of formation and development, and both are dynamic. That is why “life” and “health” categories are inseparable and complement each other.

There is no unified view among scientists on the definition of health covering all the possibility’s inherent features. Scientists in the medical field [16] note that the health of an individual is a dynamic condition (process) of preservation and development of its biological, physiological, and mental functions, optimal working ability, and social commitment with maximum prolongation of active life. Later, in co-authorship with another scientist, [17] presented a more improved definition of health: health as a biological category reflects the body’s ability to maintain and restore sufficient functional reserves to ensure adaptation to changing conditions of environment and activity. Lishchiuk [18] provided a socially adapted definition of health – the ability for adaptation, self-preservation, and self-development, resisting degradation and aging, and preventing diseases and overcoming them.

Researchers [19] noted that a holistic view of health is presented in the form of a three-component pyramidal model which is expressed by the trinity of such components as physical, mental and spiritual”. Some authors among these three components also distinguish social or spiritual components of health, for example, WHO. However, most authors emphasize the four mandatory components of this category. Spiritual health is an element of personality; therefore, it is human social nature. Naumenko [20] notes that the spiritual health of personality exactly is “the person’s desire to master universal human values: truth, verity, good; the ability to feel as a part of the world around us, the desire to make it better and actively contribute to it and in connection with it to be able to empathize, sympathize, help others, build relationships with people, to treat themselves and their lives responsibly. A materialistic person cannot be healthy”. This way, the components of health cannot be considered alone; it is not just a combination but the preservation of a balance of social, spiritual, mental, and physical health, which is under the constant influence of external and internal factors [21].

Thus, Vasilieva & Filatov [1] distinguish the following approaches to understanding the category of “health”:

The formation and effective implementation of state policy in criminal law protection of an individual's health is necessary for ensuring human rights and freedoms in Ukraine. In the globalization of criminal offenses against an individual’s health, the world’s leading countries' governments are focusing more and more on the creation and improvement of effective mechanisms of criminal law counteraction to encroachment on an individual’s health. Ukraine is entering a new era of the global information society, which requires the full provision of human rights and freedoms. In this era, anthropocentrism should become a priority in state policy. The implementation of national interests in strengthening criminal law protection of a person’s health is clear evidence that anthropocentrism is the main basis of the most important areas of such state transformation. Some aspects of the problematic issues of forming an understanding, such concepts as “health”, “pain” and “suffering” in one way or another have been studied in the scientific works of researchers that we will be mentioned below. However, these studies revealing some aspects of criminal offenses against the health of an individual, leave a range of issues in this field that is not examined in detail [1].

The collective monograph “Prevention of Tortures” [2] covers international standards for preventing tortures, inhuman treatment, lowering dignity, or punishment in detail. The classification of international documents, existing in human rights is proposed: by content, scope, and legal force. Thus, Chervyatsova states: “… every violation of human rights contains an element of lowering human dignity and every violation leads to negative consequences, physical and spiritual suffering for injured people” [2]. We do not agree with such a statement since, firstly, pain and suffering are the consequences of torture as stipulated in Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] and international acts; secondly, at first the author states that torture contains elements of lowering human dignity, then – it is the form of inhuman treatment leading to severe suffering [2]. Article 3 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms stipulates the absolute prohibition of torture or inhuman treatment, lowering human dignity, or punishment. Therefore, these concepts are independent, separate from each other, but at the same time, closely related.

In 2013, Telesnitskyi [4] analyzed the theoretical and methodological grounds for comparative legal research and the genesis of criminal liability for torture. Moreover, he provided criminal law of torture's objective and subjective features under the laws of Ukraine and foreign countries, comparative characteristics of qualifying torture features, and analyzed the problems of sanctions. Denisova analyzed the terminology widely used in the Constitution of Ukraine as well as providing the author’s definition of torture [5].

Grishchenko [6] provided a comprehensive criminal law characteristic of battery and torment (objective and subjective features of the criminal offense provided in the description of Article 126 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, and its qualifying features) and proposed to expand the content of the criminal offense object provided by the description of Article 126 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, namely: an additional direct object can be person’s honor and dignity. In our opinion, the following issues remain controversial: first, the provision that this composition of the criminal offense is formal in terms of the objective structure; second, proposals to determine the special subject among qualifying features of the criminal offense composition, as well as to determine the composition of the subject of this criminal offense composition – father, mother, stepfather, stepmother, custodian or trustee, the person authorized to upbring or take care about him or her. Today, not only this criminal offense is often committed in the family area, but also other criminal offenses against the health of an individual, so, according to the author’s reasoning, it is necessary to separate special subject of a criminal offense in each article. These suggestions aggravate this article, not considering that in case of sentencing, the court will take into account the provisions of Paragraph 6, Part 1, Article 67 “Aggravating Circumstances” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3]. Dissertation of Lakhova [7] “Criminal Liability for Causing Intentional Minor Injuries, Battery, Torment” contains insufficiently justified provision of the author; the phrase “harm to health” used by the author in interpreting the concept “body injury” contradicts its content, “suffering caused to a person due to physical or mental exposure; deterioration or deprivation of opportunities to exercise his or her habits or wishes by a person.

In the textbook “Criminal Liability for Torture in Ukraine and foreign countries” [8] the authors identified the peculiarities of objective and subjective features of torture criminal offense composition provided by the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] and the Criminal Codes of other countries. Theoretical foundations and genesis of criminal liability for torture are studied, and the social conditionality of criminal liability for torture is described (the following factors are distinguished: international law, national law, criminological, and socio-psychological factors). The authors emphasize that torture – a criminal offense, is materially defined. The textbook pays considerable attention to legally defined torture methods (battery, excruciation, and other violent acts). Still, the consequences being a mandatory feature of the objective part of such criminal offense composition are briefly described in work.

The purpose of the article was to consider the problematic issues of forming an understanding of such concepts as health, pain, and suffering.

Information and Methods

The work used a set of general scientific and special methods to achieve the goals and solve the scientific tasks. The dialectical method was used in all parts of the work, which provided an analysis of the components of area-specific (criminal law) characteristics of illegal consequences (physical pain, physical and moral suffering). Dogmatic and hermeneutic methods ensured the content interpretation of concepts and terms to clarify the categories of national criminal, international humanitarian law, and other sciences to compare the concepts. The comparative legal method allowed identifying the advantages and disadvantages inherent to the legal norms of national legislation compared with the relevant provisions of the legislation of foreign countries; the statistic method contributed to the development of the empirical base as a source of data about the subject of research; sociological methods were applied during the survey of forensic experts of general profile and judges – summary data of surveys of judges and forensic experts of the general profile from different regions of Ukraine except from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk region from October 2018 to May 2019.

The questionnaire aims to clarify the opinion of court employees and forensic experts of general profile concerning the condition of criminal law protection of person’s health from illegal encroachments in Ukraine, as well as to use the results obtained in formulating conclusions and developing practical proposals. The category of the respondents interviewed included: 114 court employees and 272 forensic experts of general profile. The questionnaire form was written by filling in/giving answers by respondents. The content of the proposed questions is determined by the content of the scientifically substantiated conclusions obtained in the article that can be refuted, confirmed, or clarified in the process of questioning. The peculiarity of the proposed answer options is that a simplified approach was used, including the following: the respondent chose one of the three answers already formulated (“yes”, “no”, “difficult to define”). The questions were formulated in the written questionnaire offered to the respondents to obtain the most accurate, reasonable, and logical answers. At the same time, the respondents needed practical experience and relevant professional skills that are valuable in scientific terms.

Among the global objectives of sustainable development for 2015-2030, it is mentioned under number 3: Strong health and well-being [9]. However, the terminology used is controversial. First, the prerequisite is that “health” as a category is studied in medical science and widely used in law science. Thus, Section II is in the Special Part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (hereinafter – the CC of Ukraine). “Criminal offenses against the life and health of an individual” contains Articles 121-128, 130, 133 in which the object is “social relations in the field of protection of human rights and freedoms against illegal encroachments that cause or may cause harm to the heal of an individual” [10]. The study of criminal law science proves that “health” as a category has not been studied in detail, and the legal acts of Ukraine do not contain its definition. For instance, in the Criminal Code of Ukraine Article, such task as “legal support of protection of rights and freedoms of a person and a citizen” is defined. This provision is supported by the Constitution of Ukraine [11] in Articles 3, 27, 28, 35, 49, which guarantee that a person, his or her life and health, honor and dignity, inviolability, and security are recognized as the highest social value. Everyone has the right to protect his or her life and health, lives, and health of other people from illegal encroachment. No one can be subjected to torture, inhuman treatment, lowering human dignity, or punishment. Everyone has the right to freedom of worldview and religion. Everyone has the right to health care, medical aid, and insurance.

All these values and other ones are enshrined in the provisions of the Basic Law of Ukraine, as well as they meet the provisions of international treaties ratified by Ukraine but do not contain the definition of “health”. Only in the preamble of the Charter of the World Health Organization (from now on – WHO) the definition of “health” is given, which was later reflected in the Law of Ukraine “Fundamentals of Ukrainian legislation on health care” [12]. Thus, “health” is the condition of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of diseases or infirmity [13]. The definition of “health” mentioned in the preamble of the WHO Charter and the Law of Ukraine “Fundamentals of Ukrainian legislation on health care” is controversial to some extent. First, the concept of social well-being is subjective, too broad, and requires a clear definition. Second, a person’s full social value is not always characterized by quantitative criteria and his or her biological condition. Third, according to this definition, it is almost impossible to find a healthy person [14].

Findings

As a result of the study of the “health” definition, scientists in the field of criminal law have concluded that this concept has been studied in the medical aspect more thoroughly. At the same time, there are some discussions concerning this issue since “heath” is a dynamic category constantly improving. Moreover, “person’s health has been under criminal law protection from the moment of starting the child-birth to the onset of biological death” [15], so, taking into account this definition, from the very beginning of life, not considering other mandatory components. From birth, a live-born, viable person possesses health. Therefore, these categories of “life” and “health” have the same initial stage of formation and development, and both are dynamic. That is why “life” and “health” categories are inseparable and complement each other.

There is no unified view among scientists on the definition of health covering all the possibility’s inherent features. Scientists in the medical field [16] note that the health of an individual is a dynamic condition (process) of preservation and development of its biological, physiological, and mental functions, optimal working ability, and social commitment with maximum prolongation of active life. Later, in co-authorship with another scientist, [17] presented a more improved definition of health: health as a biological category reflects the body’s ability to maintain and restore sufficient functional reserves to ensure adaptation to changing conditions of environment and activity. Lishchiuk [18] provided a socially adapted definition of health – the ability for adaptation, self-preservation, and self-development, resisting degradation and aging, and preventing diseases and overcoming them.

Researchers [19] noted that a holistic view of health is presented in the form of a three-component pyramidal model which is expressed by the trinity of such components as physical, mental and spiritual”. Some authors among these three components also distinguish social or spiritual components of health, for example, WHO. However, most authors emphasize the four mandatory components of this category. Spiritual health is an element of personality; therefore, it is human social nature. Naumenko [20] notes that the spiritual health of personality exactly is “the person’s desire to master universal human values: truth, verity, good; the ability to feel as a part of the world around us, the desire to make it better and actively contribute to it and in connection with it to be able to empathize, sympathize, help others, build relationships with people, to treat themselves and their lives responsibly. A materialistic person cannot be healthy”. This way, the components of health cannot be considered alone; it is not just a combination but the preservation of a balance of social, spiritual, mental, and physical health, which is under the constant influence of external and internal factors [21].

Thus, Vasilieva & Filatov [1] distinguish the following approaches to understanding the category of “health”:

• Normo-centric (health as the optimal level of functioning of a person’s body);

• Phenomenological (health as an indirect experience of physical illness, the greater this experience, the more multidimensional and wider the ideas about health become);

• Holistic (health as a whole that is acquired by a person throughout life and involves personal maturity, life experience integration, synthesis of fundamental contradictions of human existence or intrapsychic polarities, etc.);

• Axiological (health as a universal human value influenced by value orientations and their dominance, reassessment of values, as well as the crisis in a person’s life);

• Cross-cultural (health is considered through a set of characteristics determined by specific social conditions, cultural context, originality of lifestyle, and image of the world);

• Discursive (health as a product of a certain discourse with its internal logic of constructing or conceptualizing social and mental reality);

Integrative (integration of the models mentioned above and schemes on a unified conceptual basis, under the principles of systems theory.

However, studying these four components of “health”, scientists believe that these components are interconnected and balanced. However, in some cases, a person can only have a physical component and be healthy simultaneously; this is the case of the birth of a child without a range of spiritual and social components. First, the problem is that every person perceives the term “health” by analyzing the peculiarities of his or her body or acquired knowledge. For instance, a person with certain physical disabilities will initially focus on the absence of such defects in the definition. The acquired knowledge will also impact the understanding of this category. Sociology, as a science studying various aspects of society and a person, interpreting the term “health” uses social factors and phenomena (socialization of a person in society, namely, self-fulfillment – education, work, marital status, etc.). Scientists [22] distinguish “health” at three rather specific levels of life activities in the field of psychology. At the biological level, health implies a dynamic balance of functions of all internal organs and their adequate response to environmental influence. At the psychological level mental health is in some way or other related to the personality context within which a person appears as the mental whole. The main task of this level is to understand the main thing: what a healthy personality is.

At the social level health is understood rather conventionally because the psychological features of the personality simply do not exist outside the system of social relations in which it is included. At this level, a person appears, first of all, as a social being. So, scientists in different fields (medical, sociological, legal, etc.) perceive the term “health” in different ways, which is why there are problems with its interpretation. For instance, law scientists define health as “the normal functioning of the whole body” [23]. Nikiforov [24] understands health as a normal condition of the human body in general, or “a normal functioning of human tissues or organs” [25]. Petrovsky [26] defines a person’s health as body integrity and normal functioning of human body organs [27]. A researcher [28] notes that health as personal well-being is one of the most important conditions for normal life activity of a certain person of all his or her parts, organs, and systems, it is such a condition of a person that ensures the performance of various biological and sociological functions. Other researcher [29] defines health as integrity, normal functioning of the most important organs and systems of the human body, without which it is inconceivable to ensure its normal life activities. Or “normal functioning of tissues and organs of human body” [30].

Analyzing the definition of “health” in scientific studies, a certain tendency can be observed. Scientists of the earlier period in the definition of “health” talked about the “organism” without separating its components – organs [23-24]. In further studies by scientists [25], such specification has already been present in the definition of “health”. By the end of the twentieth century, the following mandatory components had appeared in the definition: social, so the scientists talked not only about the physical structural elements of a person but also about the actualization of a person in the world as a social being. A researcher [29], in his definition of “health” is referred to as “the most important organs and systems of the human body”. However, it should be taken into account that the human body is constructed in such a way that each organ performs a certain function; therefore, all organs and systems are important because they are all connected anatomically and topographically and perform certain functions. Therefore, the definition of “health” in law science requires clarification.

There are a lot of definitions of such categories, which remain relevant today. However, in our opinion, it is necessary to use the term “a person” along with this term because this category is studied in a person exactly, as a biological category that determines the affiliation of a living being to humanity according to certain anatomical peculiarities and physiological functions with his or her transformation into the socially significant category of “a person”, and later on – “a citizen”. At the same time, the term “individual” is used in the legislation in the establishment of the object of a criminal offense and the title of Section II. “Criminal offenses against life and health of an individual” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, not because the term “a person” includes all sociological categories.

Analysis of the Basic Law of Ukraine as the basis for criminal legislation defines this term as a key term stating that: “A person, his or her life and health, honor and dignity, inviolability and security are recognized as the highest social value in Ukraine. Human rights and freedoms and their guarantees determine the content and direction of state activity. The state is responsible to a person for its activity. The establishment and protection of human rights and freedoms are the main duty of the state (Article 3). As for criminal law, then the legislator does not always approach the use of terminology consistently, as evidenced by the titles of Sections II-V. of a special part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3], in which the legislator mainly uses the term “individual” concerning the life, health, will, honor, dignity, sexual freedom, sexual integrity, electoral, labor, and other personal rights and freedoms.

The collapse of the Soviet socialist system at the verge of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and the transition to market relations, not taking into account economic, social, political, and other difficulties and crisis phenomena on the way to young democracy, the criminal law in Ukraine is directed in anthropocentric dimension. Anthropocentrism should be at the heart of our legislation and law enforcement practice, although criminal law contains different terminology “an individual”, “a person”, “a citizen”. In recent years there have been discussions on the use of such social categories as: “an individual”, “a person”, and “a citizen”, describing peculiarities of their status and opportunities for protection of subjective interests.

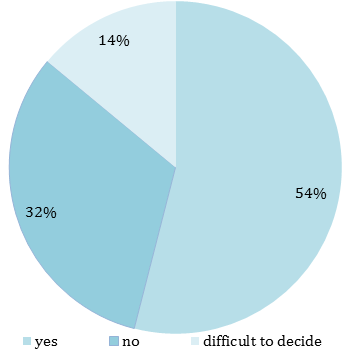

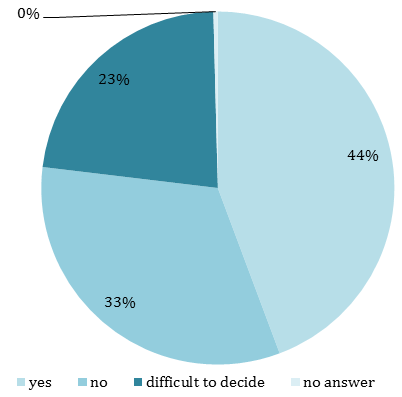

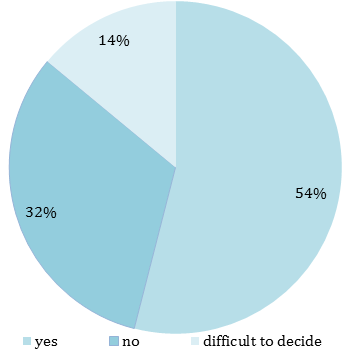

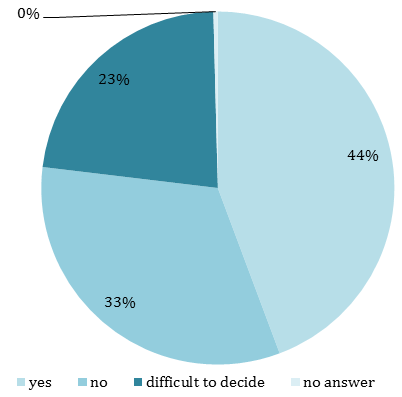

However, unfortunately, there is no legal definition of “a person” currently. This way, we consider it necessary to provide a legal definition of such terminology, which would be the result of the work of specialists in various branches of law (civil, criminal, labor, etc.). Today it is reasonable to use the term most common in current legislation – an individual. The lawmaker establishes physical pain (severe physical pain) as one of the consequences of criminal offenses against the health of an individual in Articles 126 “Battery and Torment” and 127 “Torture” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. The survey of judges and forensic experts concerning the presence of evaluative concepts in the Criminal Code of Ukraine (physical pain, severe physical pain, physical or moral suffering) allows summarizing that 54% (judges) out of the total number of respondents said that the provision of the Criminal Code should have evaluative concepts (Figure 1). The forensic experts gave less percentage of positive answers (44.3%) to the same question (Figure 2).

Thus, the analysis of questionnaire data allows stating that despite the controversial peculiarity of such terminology in practice, as well as disputes that arise among scientists, the articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] enable the existence of such terminology that hardly promotes the unity of understanding of relevant concepts. At the same time, there is no legal definition of physical pain, and law science does not provide a unified view of such a concept definition.

Figure 1) Survey results for jungles

Figure 2) Survey results for forensic experts

Physical pain is understood as a mental state of an individual characterized by the suffering caused by a physical impact on his or her body [31]. Pain (in the medical sense) is not only a human sense but also an indicator of the onset of negative health changes: any painful senses are accompanied by changes in the body related to various human functional systems (respiration, blood circulation, body statics, and kinetics provision, etc.) [26]. The medical literature states the following: “pain is the sense of not only physical suffering, but a sense of sadness, hurt, sorrow” [32]. Sharapov [33] emphasizes that a specific form of physical pain is physical suffering – a consequence of violence indicating the manifestation of special cruelty to the victim by a guilty person. In the Scientific and Practical Commentary of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, edited by Lohvynenko et al. [31], it is stated that physical suffering is such suffering that occurs because of a negative influence on the physical area of an individual, so physical pain is a certain mental condition of a person defined by a set of physiological processes of the central nervous system caused by excessively strong or destructive stimuli. Physical pain is severely depressing. Suppose a person is healthy in mental terms. In that case, physical suffering inevitably causes moral suffering, which may manifest as hurt, shame, grief, depression, a sense of irreversible loss, etc. Thus, not all scientists distinguish between the concepts of physical pain and physical suffering.

Analyzing Article 127 “Torture” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, the law-maker emphasizes the “severe physical pain”, “since during torture an individual suffers from not just pain but excruciating pain, the pain of the “highest quality”. It depends on the victim's subjective (personality) peculiarities, objective conditions of the criminal offense, and the severity of bodily injuries. Moreover, this same term is following international practice” [34]. At present, it is impossible to establish the criterion of physical pain (intensity) in practice. Questionnaire data according to the results of a survey of forensic experts on identifying signs of physical pain, severe physical pain, and physical or moral suffering allow concluding that only 29.6% of forensic experts had to conduct examinations to establish illegal consequences defined by a lawmaker in Article 126, 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3]. It is caused by the fact that there is no such term in medicine. Namely, there is no specification that “pain” must be physical. At present, it is possible to define the qualitative criterion of pain due to the subjective reaction of an individual – verbal rating scale of pain (verbal descriptive scale of pain, facial pain scale, modified facial pain scale visual analog scale, numerical pain scale, Bloechle pain scale, pain scale assessment in the ICU based on observation [35]. However, every individual has different pain sensitivity (perception); that is, under the physical impact on an individual’s body, people will assess the sense of pain differently: from no pain at all to excruciating pain.

Moreover, it is possible to determine the following characteristics of pain: origin, location (localization), duration, attribute (acute, burning), and factors aggravating or alleviating pain. Therefore, by the above mentioned, it is impossible to measure the strength of pain (qualitative). So, it is unreasonable to separate that pain must be physical and severe in Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3].

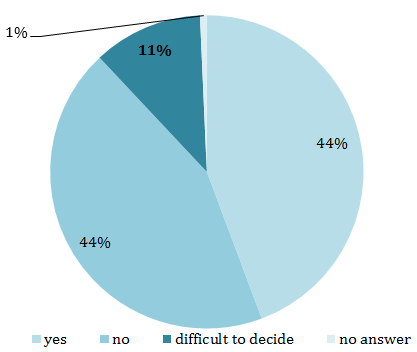

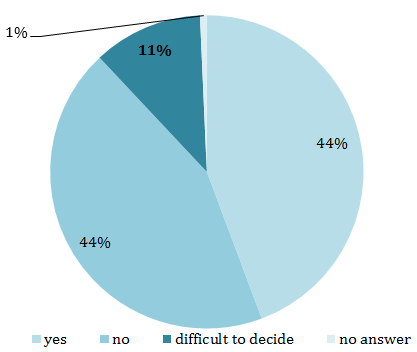

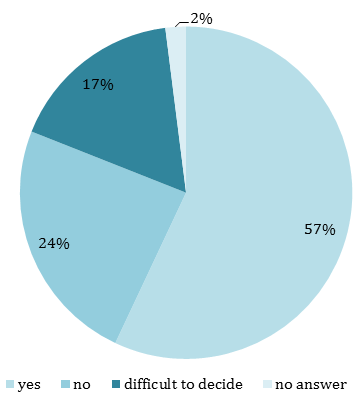

In the questionnaire, 57% of judges answered positively about whether changes and amendments were necessary for the articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (Figure 3). Forensic experts 44.3% supported such judges’ initiatives (Figure 4).

Carrying out a comparative law characteristic of criminal legislation (Israel, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Lithuania, as well as the Republic of Tajikistan and the Russian Federation), it was found that some articles contained the terminology of “physical pain”. At the federal level, American criminal law does not clearly distinguish between groups of criminal offenses against an individual’s life and health and their separate subgroups [36], and criminal offenses against health include injuries and battery [37]. It distinguishes “bodily injuries”, namely: physical pain, illness, or any other deterioration of physical condition; “grave bodily injury” means a bodily injury is posing a significant risk of death or an injury causing severe permanent mutilation or prolonged loss or impairment of the function of any body part or organ. These terms are used by the US lawmaker as consequences of an attack.

Figure 3) Survey results for jungles

Figure 4) Survey results for forensic experts

Discussion

The judgments of the European Court of Human Rights give criteria for determining cruel forms of treatment of a person, including inflicting severe physical pain on him or her: inflicting hits on feet [38]; physical violence, the so-called “Palestinian hanging” [39]; applying electricity to a person is the most serious form of a poor treatment that may cause severe pain and severe suffering and, therefore, should be considered torture, even if it does not lead to any long-term health problems [40] and many other judgments. Thus, the criminal law of some countries contains the terminology of “physical pain”. However, there are some exceptions, namely: criminal legislation of Austria, Australia, Sweden, Norway, the Republic of Belarus, and Bulgaria does not mention that pain must be physical; this way, the understanding of this terminology is simplified.

The problems in understanding and applying some provisions of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, namely “physical pain” and “physical suffering” lead to irreversible mistakes in practice. A researcher notes that it hardly makes sense to separate the concepts “severe physical pain” and “physical suffering” in defining torture (as well as torment) because they are interrelated: when a person experiences severe physical pain, he or she suffers. It is better to use only the “physical suffering” concept by which severe physical pain can be characterized [41]. Other researchers do not agree with the above-mentioned and notes that suffering is not pain, although these words are used as synonyms in everyday language. To determine the content of this term, we will define the terms “physical suffering” and “moral suffering” that will allow us to separate the terms “pain” and “suffering” [5].

To better understand these terms, we offer to study suffering as a criminal law category. Thus, considering the objective criteria of suffering, it is necessary to distinguish the time indicator as the main one, and the nature of the impact on the human body as a subsidiary indicator [42]. So, in analyzing suffering, it is necessary to note regularity, although scientists understand this term differently. Thus, regularity is the same bodily injury more or less often caused by different objects [43]; not less than three times [44]; physical violence, consisting of at least two socially dangerous acts, interrupted in time, at establishing the intent to commit a certain number of them in the future [45]; the main legal criterion for assessing the consequences such as mental suffering is not the depth of negative mental reactions but the time of their implementation [46]. However, it is necessary to consider not only quantitative but also qualitative characteristics of the act, taking into account all the case circumstances when characterizing the regularity [42]. In medical terms, a typical feature of this condition is a stretch in time (up to several days, months, or even years), “during which a more or less prolonged psycho-traumatic situation, protracted psychogenesis develops causing accumulation” of negative emotions in the victim [47].

The definition of physical and moral suffering is not provided by the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] which creates prerequisites for discussions related to the understanding of such terms. Some scientists do not separate them and do not see any sense in their “dual” existence. “Physical suffering” has no clear criteria for its definition and cannot have them because, unlike trauma it is not a disease, pathological condition, and pain, a medical term defining harm to health [48]. The suffering, which is either pain with the constant expectation of the possibility of its reoccurrence or especially severe pain or a specific form of pain, has no solid legal framework [45]. Researcher [49] notes that the same actions can affect a person both physically and morally simultaneously. Thus, it is quite possible to state that the physical torture of a person, as a rule, is accompanied by moral suffering. The same point of view is supported by other scientists who note that physical impact on a person is often combined with mental one, and vice versa [50]. There is also a belief that it is difficult to assess unambiguously the appropriateness of introducing these socially dangerous consequences into the criminal offense composition of torture [34].

Yessimov et al. [51] notes that the concept of moral damage contains both moral experiences and moral suffering. Moral experiences are more likely to be involved in all cases of a criminal offense where there is a victim. To understand moral suffering, the author gives an example of the theft of property that has been not only money but also “an ideal value” for the owner (for instance, the theft of rare photographs, family jewelry, etc.) In this case, one should consider not only the moral experiences suffered by the victim about the theft of property but also the moral suffering to be indemnified within civil proceedings (Part 3, Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine). In our opinion, the author studied suffering only in the context of the loss of a certain thing being of some value to the victim but without considering one of the possible consequences of Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3], namely: moral suffering. At the same time, in his research Yessimov et al. [51] notes that moral suffering is the only consequence of Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which does not correspond to reality.

Some legal acts of Ukraine have combined the terms “pain” and “suffering” into one “moral damage”. Thus, according to Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine, moral damage is the following: 1) physical pain and suffering that an individual has experienced in connection with a mutilation or other damage to health; 2) mental suffering that an individual has experienced in connection with illegal behavior towards him- or herself, their family members or close relatives; mental suffering that an individual has experienced in connection with the destruction or damage to his or her property; 4) lowering of honor, dignity as well as the business reputation of an individual or a legal entity. Therefore, a lawmaker in the Civil Code of Ukraine and the Criminal Code of Ukraine distinguishes physical pain and suffering and uses the terminology “mental suffering” (Paragraph 2, 3, Part 23 Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine) also controversial.

Conclusion

The health of an individual, being determinative and controversial category, remains one of the fundamental natural values (benefits) protected not only by criminal legislation but all countries of the world. Its theoretical content is still debatable in the various fields of science (medicine, forensic medicine, psychology, law science, etc.) Along with the definition of “health”, its component (components) model (categories, levels) remains controversial, too. We believe that it should be used based on our legislation and law enforcement practice in the administration of law; therefore, it is reasonable to develop a legal definition of the term “a person” using the knowledge of specialists from various fields of law. The terminology which is widely used in criminal law, such as “physical pain”, and “physical and moral suffering”, as consequences of criminal offenses, provided by Articles 126 (Battery and Torment) and 127 (Torture) of the criminal code of Ukraine is problematic both in the administration of law and understanding. Current legislation does not provide definitions of such terminology. Scientists sometimes substitute these terms in their research without separating them from each other. Certain scientific studies on the issues mentioned had been conducted and published before the adoption of the Criminal Code of Ukraine in 2001. Hence, the content of Section II of the Special Part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, remained without any significant changes in terms of criminal offenses against the health of an individual. However, there are still many issues not studied in detail at present.

Acknowledgments: None.

Ethical Permissions: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. A study was approved by the National Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, January 22, 2022, No 2201-3.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Ihor Diorditsa (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (25%); Kateryna Katerynchuk (Second Author), Methodologist (25%); Sergiy Kyrenko (Third Author), Discussion Writer/Methodologist (20%); Iryna Vasylkivska (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (15%); Olha Bespal (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%)

Funding/Support: None.

At the social level health is understood rather conventionally because the psychological features of the personality simply do not exist outside the system of social relations in which it is included. At this level, a person appears, first of all, as a social being. So, scientists in different fields (medical, sociological, legal, etc.) perceive the term “health” in different ways, which is why there are problems with its interpretation. For instance, law scientists define health as “the normal functioning of the whole body” [23]. Nikiforov [24] understands health as a normal condition of the human body in general, or “a normal functioning of human tissues or organs” [25]. Petrovsky [26] defines a person’s health as body integrity and normal functioning of human body organs [27]. A researcher [28] notes that health as personal well-being is one of the most important conditions for normal life activity of a certain person of all his or her parts, organs, and systems, it is such a condition of a person that ensures the performance of various biological and sociological functions. Other researcher [29] defines health as integrity, normal functioning of the most important organs and systems of the human body, without which it is inconceivable to ensure its normal life activities. Or “normal functioning of tissues and organs of human body” [30].

Analyzing the definition of “health” in scientific studies, a certain tendency can be observed. Scientists of the earlier period in the definition of “health” talked about the “organism” without separating its components – organs [23-24]. In further studies by scientists [25], such specification has already been present in the definition of “health”. By the end of the twentieth century, the following mandatory components had appeared in the definition: social, so the scientists talked not only about the physical structural elements of a person but also about the actualization of a person in the world as a social being. A researcher [29], in his definition of “health” is referred to as “the most important organs and systems of the human body”. However, it should be taken into account that the human body is constructed in such a way that each organ performs a certain function; therefore, all organs and systems are important because they are all connected anatomically and topographically and perform certain functions. Therefore, the definition of “health” in law science requires clarification.

There are a lot of definitions of such categories, which remain relevant today. However, in our opinion, it is necessary to use the term “a person” along with this term because this category is studied in a person exactly, as a biological category that determines the affiliation of a living being to humanity according to certain anatomical peculiarities and physiological functions with his or her transformation into the socially significant category of “a person”, and later on – “a citizen”. At the same time, the term “individual” is used in the legislation in the establishment of the object of a criminal offense and the title of Section II. “Criminal offenses against life and health of an individual” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, not because the term “a person” includes all sociological categories.

Analysis of the Basic Law of Ukraine as the basis for criminal legislation defines this term as a key term stating that: “A person, his or her life and health, honor and dignity, inviolability and security are recognized as the highest social value in Ukraine. Human rights and freedoms and their guarantees determine the content and direction of state activity. The state is responsible to a person for its activity. The establishment and protection of human rights and freedoms are the main duty of the state (Article 3). As for criminal law, then the legislator does not always approach the use of terminology consistently, as evidenced by the titles of Sections II-V. of a special part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3], in which the legislator mainly uses the term “individual” concerning the life, health, will, honor, dignity, sexual freedom, sexual integrity, electoral, labor, and other personal rights and freedoms.

The collapse of the Soviet socialist system at the verge of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and the transition to market relations, not taking into account economic, social, political, and other difficulties and crisis phenomena on the way to young democracy, the criminal law in Ukraine is directed in anthropocentric dimension. Anthropocentrism should be at the heart of our legislation and law enforcement practice, although criminal law contains different terminology “an individual”, “a person”, “a citizen”. In recent years there have been discussions on the use of such social categories as: “an individual”, “a person”, and “a citizen”, describing peculiarities of their status and opportunities for protection of subjective interests.

However, unfortunately, there is no legal definition of “a person” currently. This way, we consider it necessary to provide a legal definition of such terminology, which would be the result of the work of specialists in various branches of law (civil, criminal, labor, etc.). Today it is reasonable to use the term most common in current legislation – an individual. The lawmaker establishes physical pain (severe physical pain) as one of the consequences of criminal offenses against the health of an individual in Articles 126 “Battery and Torment” and 127 “Torture” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. The survey of judges and forensic experts concerning the presence of evaluative concepts in the Criminal Code of Ukraine (physical pain, severe physical pain, physical or moral suffering) allows summarizing that 54% (judges) out of the total number of respondents said that the provision of the Criminal Code should have evaluative concepts (Figure 1). The forensic experts gave less percentage of positive answers (44.3%) to the same question (Figure 2).

Thus, the analysis of questionnaire data allows stating that despite the controversial peculiarity of such terminology in practice, as well as disputes that arise among scientists, the articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] enable the existence of such terminology that hardly promotes the unity of understanding of relevant concepts. At the same time, there is no legal definition of physical pain, and law science does not provide a unified view of such a concept definition.

Figure 1) Survey results for jungles

Figure 2) Survey results for forensic experts

Physical pain is understood as a mental state of an individual characterized by the suffering caused by a physical impact on his or her body [31]. Pain (in the medical sense) is not only a human sense but also an indicator of the onset of negative health changes: any painful senses are accompanied by changes in the body related to various human functional systems (respiration, blood circulation, body statics, and kinetics provision, etc.) [26]. The medical literature states the following: “pain is the sense of not only physical suffering, but a sense of sadness, hurt, sorrow” [32]. Sharapov [33] emphasizes that a specific form of physical pain is physical suffering – a consequence of violence indicating the manifestation of special cruelty to the victim by a guilty person. In the Scientific and Practical Commentary of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, edited by Lohvynenko et al. [31], it is stated that physical suffering is such suffering that occurs because of a negative influence on the physical area of an individual, so physical pain is a certain mental condition of a person defined by a set of physiological processes of the central nervous system caused by excessively strong or destructive stimuli. Physical pain is severely depressing. Suppose a person is healthy in mental terms. In that case, physical suffering inevitably causes moral suffering, which may manifest as hurt, shame, grief, depression, a sense of irreversible loss, etc. Thus, not all scientists distinguish between the concepts of physical pain and physical suffering.

Analyzing Article 127 “Torture” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, the law-maker emphasizes the “severe physical pain”, “since during torture an individual suffers from not just pain but excruciating pain, the pain of the “highest quality”. It depends on the victim's subjective (personality) peculiarities, objective conditions of the criminal offense, and the severity of bodily injuries. Moreover, this same term is following international practice” [34]. At present, it is impossible to establish the criterion of physical pain (intensity) in practice. Questionnaire data according to the results of a survey of forensic experts on identifying signs of physical pain, severe physical pain, and physical or moral suffering allow concluding that only 29.6% of forensic experts had to conduct examinations to establish illegal consequences defined by a lawmaker in Article 126, 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3]. It is caused by the fact that there is no such term in medicine. Namely, there is no specification that “pain” must be physical. At present, it is possible to define the qualitative criterion of pain due to the subjective reaction of an individual – verbal rating scale of pain (verbal descriptive scale of pain, facial pain scale, modified facial pain scale visual analog scale, numerical pain scale, Bloechle pain scale, pain scale assessment in the ICU based on observation [35]. However, every individual has different pain sensitivity (perception); that is, under the physical impact on an individual’s body, people will assess the sense of pain differently: from no pain at all to excruciating pain.

Moreover, it is possible to determine the following characteristics of pain: origin, location (localization), duration, attribute (acute, burning), and factors aggravating or alleviating pain. Therefore, by the above mentioned, it is impossible to measure the strength of pain (qualitative). So, it is unreasonable to separate that pain must be physical and severe in Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3].

In the questionnaire, 57% of judges answered positively about whether changes and amendments were necessary for the articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (Figure 3). Forensic experts 44.3% supported such judges’ initiatives (Figure 4).

Carrying out a comparative law characteristic of criminal legislation (Israel, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Lithuania, as well as the Republic of Tajikistan and the Russian Federation), it was found that some articles contained the terminology of “physical pain”. At the federal level, American criminal law does not clearly distinguish between groups of criminal offenses against an individual’s life and health and their separate subgroups [36], and criminal offenses against health include injuries and battery [37]. It distinguishes “bodily injuries”, namely: physical pain, illness, or any other deterioration of physical condition; “grave bodily injury” means a bodily injury is posing a significant risk of death or an injury causing severe permanent mutilation or prolonged loss or impairment of the function of any body part or organ. These terms are used by the US lawmaker as consequences of an attack.

Figure 3) Survey results for jungles

Figure 4) Survey results for forensic experts

Discussion

The judgments of the European Court of Human Rights give criteria for determining cruel forms of treatment of a person, including inflicting severe physical pain on him or her: inflicting hits on feet [38]; physical violence, the so-called “Palestinian hanging” [39]; applying electricity to a person is the most serious form of a poor treatment that may cause severe pain and severe suffering and, therefore, should be considered torture, even if it does not lead to any long-term health problems [40] and many other judgments. Thus, the criminal law of some countries contains the terminology of “physical pain”. However, there are some exceptions, namely: criminal legislation of Austria, Australia, Sweden, Norway, the Republic of Belarus, and Bulgaria does not mention that pain must be physical; this way, the understanding of this terminology is simplified.

The problems in understanding and applying some provisions of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, namely “physical pain” and “physical suffering” lead to irreversible mistakes in practice. A researcher notes that it hardly makes sense to separate the concepts “severe physical pain” and “physical suffering” in defining torture (as well as torment) because they are interrelated: when a person experiences severe physical pain, he or she suffers. It is better to use only the “physical suffering” concept by which severe physical pain can be characterized [41]. Other researchers do not agree with the above-mentioned and notes that suffering is not pain, although these words are used as synonyms in everyday language. To determine the content of this term, we will define the terms “physical suffering” and “moral suffering” that will allow us to separate the terms “pain” and “suffering” [5].

To better understand these terms, we offer to study suffering as a criminal law category. Thus, considering the objective criteria of suffering, it is necessary to distinguish the time indicator as the main one, and the nature of the impact on the human body as a subsidiary indicator [42]. So, in analyzing suffering, it is necessary to note regularity, although scientists understand this term differently. Thus, regularity is the same bodily injury more or less often caused by different objects [43]; not less than three times [44]; physical violence, consisting of at least two socially dangerous acts, interrupted in time, at establishing the intent to commit a certain number of them in the future [45]; the main legal criterion for assessing the consequences such as mental suffering is not the depth of negative mental reactions but the time of their implementation [46]. However, it is necessary to consider not only quantitative but also qualitative characteristics of the act, taking into account all the case circumstances when characterizing the regularity [42]. In medical terms, a typical feature of this condition is a stretch in time (up to several days, months, or even years), “during which a more or less prolonged psycho-traumatic situation, protracted psychogenesis develops causing accumulation” of negative emotions in the victim [47].

The definition of physical and moral suffering is not provided by the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3] which creates prerequisites for discussions related to the understanding of such terms. Some scientists do not separate them and do not see any sense in their “dual” existence. “Physical suffering” has no clear criteria for its definition and cannot have them because, unlike trauma it is not a disease, pathological condition, and pain, a medical term defining harm to health [48]. The suffering, which is either pain with the constant expectation of the possibility of its reoccurrence or especially severe pain or a specific form of pain, has no solid legal framework [45]. Researcher [49] notes that the same actions can affect a person both physically and morally simultaneously. Thus, it is quite possible to state that the physical torture of a person, as a rule, is accompanied by moral suffering. The same point of view is supported by other scientists who note that physical impact on a person is often combined with mental one, and vice versa [50]. There is also a belief that it is difficult to assess unambiguously the appropriateness of introducing these socially dangerous consequences into the criminal offense composition of torture [34].

Yessimov et al. [51] notes that the concept of moral damage contains both moral experiences and moral suffering. Moral experiences are more likely to be involved in all cases of a criminal offense where there is a victim. To understand moral suffering, the author gives an example of the theft of property that has been not only money but also “an ideal value” for the owner (for instance, the theft of rare photographs, family jewelry, etc.) In this case, one should consider not only the moral experiences suffered by the victim about the theft of property but also the moral suffering to be indemnified within civil proceedings (Part 3, Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine). In our opinion, the author studied suffering only in the context of the loss of a certain thing being of some value to the victim but without considering one of the possible consequences of Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine [3], namely: moral suffering. At the same time, in his research Yessimov et al. [51] notes that moral suffering is the only consequence of Article 127 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which does not correspond to reality.

Some legal acts of Ukraine have combined the terms “pain” and “suffering” into one “moral damage”. Thus, according to Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine, moral damage is the following: 1) physical pain and suffering that an individual has experienced in connection with a mutilation or other damage to health; 2) mental suffering that an individual has experienced in connection with illegal behavior towards him- or herself, their family members or close relatives; mental suffering that an individual has experienced in connection with the destruction or damage to his or her property; 4) lowering of honor, dignity as well as the business reputation of an individual or a legal entity. Therefore, a lawmaker in the Civil Code of Ukraine and the Criminal Code of Ukraine distinguishes physical pain and suffering and uses the terminology “mental suffering” (Paragraph 2, 3, Part 23 Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine) also controversial.

Conclusion

The health of an individual, being determinative and controversial category, remains one of the fundamental natural values (benefits) protected not only by criminal legislation but all countries of the world. Its theoretical content is still debatable in the various fields of science (medicine, forensic medicine, psychology, law science, etc.) Along with the definition of “health”, its component (components) model (categories, levels) remains controversial, too. We believe that it should be used based on our legislation and law enforcement practice in the administration of law; therefore, it is reasonable to develop a legal definition of the term “a person” using the knowledge of specialists from various fields of law. The terminology which is widely used in criminal law, such as “physical pain”, and “physical and moral suffering”, as consequences of criminal offenses, provided by Articles 126 (Battery and Torment) and 127 (Torture) of the criminal code of Ukraine is problematic both in the administration of law and understanding. Current legislation does not provide definitions of such terminology. Scientists sometimes substitute these terms in their research without separating them from each other. Certain scientific studies on the issues mentioned had been conducted and published before the adoption of the Criminal Code of Ukraine in 2001. Hence, the content of Section II of the Special Part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, remained without any significant changes in terms of criminal offenses against the health of an individual. However, there are still many issues not studied in detail at present.

Acknowledgments: None.

Ethical Permissions: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. A study was approved by the National Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, January 22, 2022, No 2201-3.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Ihor Diorditsa (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (25%); Kateryna Katerynchuk (Second Author), Methodologist (25%); Sergiy Kyrenko (Third Author), Discussion Writer/Methodologist (20%); Iryna Vasylkivska (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (15%); Olha Bespal (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%)

Funding/Support: None.

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Health Literacy

Received: 2022/04/4 | Accepted: 2022/05/25 | Published: 2022/06/18

Received: 2022/04/4 | Accepted: 2022/05/25 | Published: 2022/06/18

References

1. Vasilyeva OS, Filatov FR. Human health psychology [Internet]. Moscow: Publishing Center "Akademiya"; 2001. [cited 2022 March 5]. Available from: https://www.studmed.ru/view/vasileva-os-filatov-fr-psihologiya-zdorovya-cheloveka-etalony-predstavleniya-ustanovki_2472d51adcb.html [Russian] [Link]

2. Kovalenko VV, Chervyatsova AA, Yarmysh ON. Prevention of tortures. Kyiv: Attica; 2010. [Ukrainian] [Link]

3. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Criminal code of Ukraine [Internet]. Kyiv: Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine; 2001 [cited 2022 March 9]. Available from: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2341-14#Text [Ukrainian] [Link]

4. Telesnitskyi GN. Criminal liability for torture: a comparative legal study [Internet]. Kyiv: National Academy of Internal Affairs; 2013. [cited 2022 March 3]. Available from: https://mydisser.com/ua/catalog/view/6/348/15378.html [Ukrainian] [Link]

5. Firszt-Adamczyk A, Ruszkowska-Ciastek B, Adamczyk P, Szafkowski R, Firszt M, Ponikowska I, et al. Effect of a 3-week low-calorie diet and balneological treatment on selected coagulation parameters in morbidly obese patients. Adv Clinic Experim Med. 2016;25(4):755-61. [Link] [DOI:10.17219/acem/42414]

6. Balynska O, Blahuta R, Sereda V, Shelukhin N, Kharaberiush I. Neurolaw: Branch or section of new sciences, a complex branch of law or a way to justify criminals (review). Georg Med News. 2019;(289):162-8. [Link]

7. Lakhova OV. Criminal liability for causing intentional minor injuries, battery, torment. Dnipro: Dnipropetrovsk State University of Internal Affairs; 2017. [Ukrainian] [Link]

8. Savchenko AV. Criminal liability for torture in Ukraine and foreign countries. Kyiv: Condor Publishing House; 2018. [Ukrainian] [Link]

9. ua.undp.org [Internet]. Kyiv: United Nations Development Programme; 2021 [cited 2022 March 17]. Available from: https://www.undp.org/ukraine [Link]

10. Katerinchuk KV. Criminal legal protection of personal health: doctrinal, legislative and law enforcement issues. Kyiv: V.I. Vernadsky Taurida National University; 2019. [Ukrainian] [Link]

11. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Constitution of Ukraine [Internet]. Kyiv: Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine; 1996 [cited 2022 March 12]. Available from: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/254%D0%BA/96-%D0%B2%D1%80#Text [Ukrainian] [Link]

12. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Law of Ukraine No. 2801-XII "On Fundamentals of Ukrainian legislation on health care" [Internet]. Kyiv: Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine; 1992 [cited 2022 March 10]. Available from: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2801-12#Text [Ukrainian] [Link]

13. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Statute (constitution) of the all-world organization for the protection of health [Internet]. Kyiv: Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine; 1946. [cited 2022 March 7]. Available from: http://zakon2.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/995_599 [Ukrainian] [Link]

14. MedicLab. Definition of health concepts and criteria [Internet]. Kyiv: Medical portal MedicLab; 2012 [cited 2022 March 6]. Available from: http://mediclab.com.ua/index.php?newsid=13198 [Ukrainian] [Link]

15. Kerniakevych-Tanasiichuk YV, Sezonov VS, Nychytailo IM, Savchuk MA, Tsareva IV. Problems of forensic identification of handwriting in forensic examination. J Nat Acad Leg Sci Ukr. 2021;28(1):195-204. [Link] [DOI:10.37635/jnalsu.28(1).2021.195-204]

16. Dobrovanov O, Králinský K. The role of prenatal diagnostics in the identification congenital malformations of urogenital system in Slovakia. Lek Obz. 2019;68(2):59-62. [Slovak] [Link]

17. Tazhbenova ST, Millere I, Yermukhanova LS, Sultanova G, Turebaev M, Sultanova BP. Effectiveness of diabetes mellitus management program at primary health care level. Electron J Gen Med. 2019;16(6):em172. [Link] [DOI:10.29333/ejgm/115848]

18. Lishchuk VA. Fundamentality of medical science and valeology. Valeology. 2010;1:15-25. [Russian] [Link]

19. Yessimov N, Izmailova N, Yessimov D. Study of psychological satisfaction of population with services of the primary health care integrated into public health. J Intel Dis Diagn Treat. 2020;8(4):662-72. [Link] [DOI:10.6000/2292-2598.2020.08.04.9]

20. Naumenko NV. The formation of spiritual health of the individual as a modern pedagogical problem. Sci Notes Nizhyn State Univ. 2012;2:32-5. [Ukrainian] [Link]

21. Grandt VV, Titenkova GV. Theoretical analysis of the problem of personal health in modern psychological research. Probl Modern Psychol. 2013;2:30-4. [Ukrainian] [Link]

22. Kotsan IYa, Lozhkin GV, Mushkevich MI. Psychology of human health. Lutsk: Vezha; 2011. [Ukrainian] [Link]

23. Gurevich LI. The fight against bodily injury under Soviet criminal law. Moscow: Institute of Legislation and Comparative Law Under the Government of the Russian Federation; 1950. [Russian] [Link]

24. Nikiforov OS. Responsibility for bodily injury under Soviet criminal law. Moscow: Nauka; 1959. [Russian] [Link]

25. Dubovets AP. Responsibility for bodily injury under Soviet criminal law. Moscow: Nauka; 1964. [Russian] [Link]

26. Petrovsky BV. Great medical encyclopedia. Moscow: Sovetskaya entsiklopediya; 1976. [Russian] [Link]

27. Krieger GL, Piontkovsky AA, Romashkin PS. Course of soviet criminal law: particular. In: Crimes against the person, her rights. Commercial crimes. Moscow: Nauka; 1971. [Russian] [Link]

28. Yessimov N, Izmailova N, Yessimov D. Integration of primary healthcare and public health. Int J Electron Healthcare. 2021;11(4):289-306. [Link] [DOI:10.1504/IJEH.2021.117826]

29. Chekhovska IV, Balynska OM, Blahuta RI, Sereda VV, Mosondz SO. Euthanasia or palliative care: legal principles of the implementation in the context of the realization of human rights to life. Wiad Lek. 2019;72(4):677-81. [Link] [DOI:10.36740/WLek201904133]

30. Balynska O, Teremetskyi V, Zharovska I, Shchyrba M, Novytska N. Patient's right to privacy in the health care sector. Georg Med News. 2021;(321):147-53. [Link]