Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 467-475 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Arefi Z, Sadeghi R, Shojaeizadeh D, Yaseri M, Shahbazi Sighaldeh S. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Physical Activity Scale for Pregnant Women. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :467-475

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60728-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60728-en.html

1- Department of Health Promotion and Education, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Physical Activity [MeSH], Scale Development [MeSH], Psychometrics [MeSH], Pregnant Women [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 760 kb]

(3556 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2571 Views)

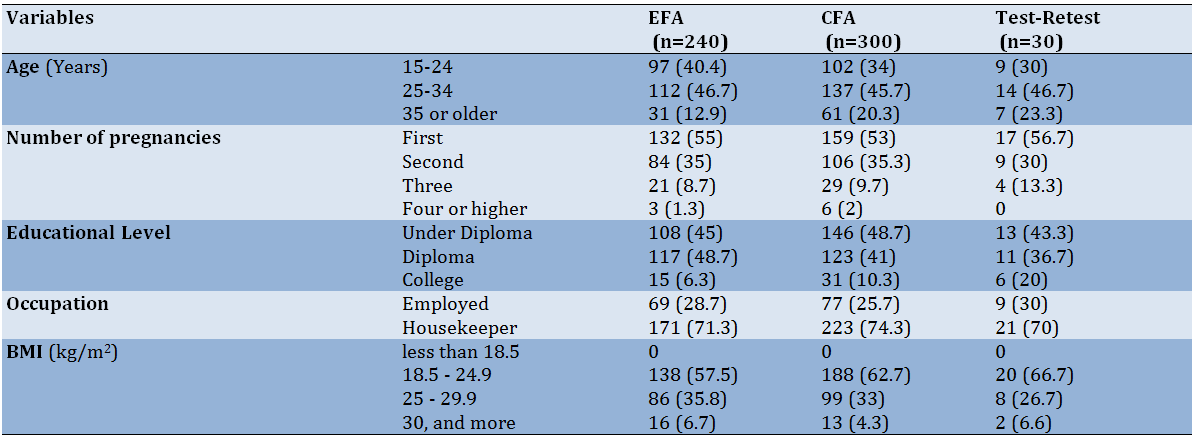

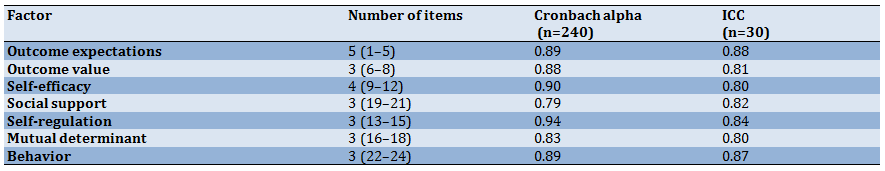

Table1) Participant's demographic characteristics in three stages (Numbers in parentheses are in percent)

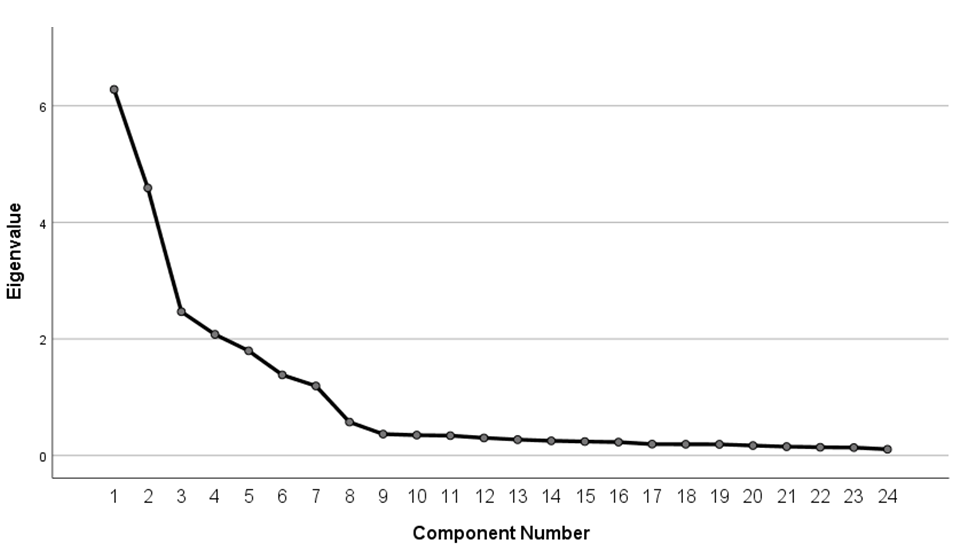

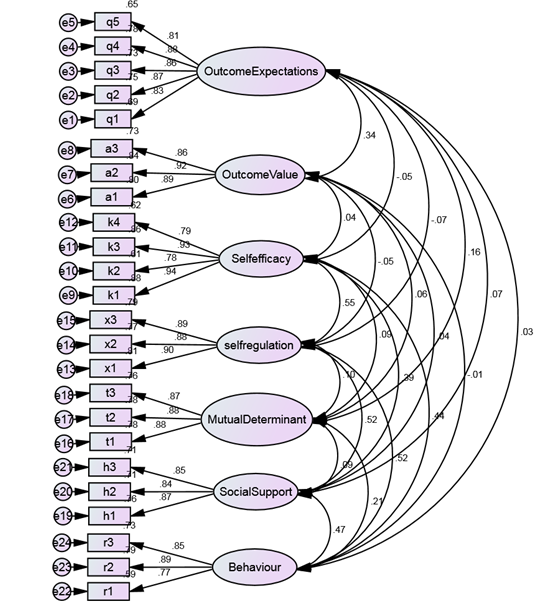

Diagram 1) Scree plot for determining the factors

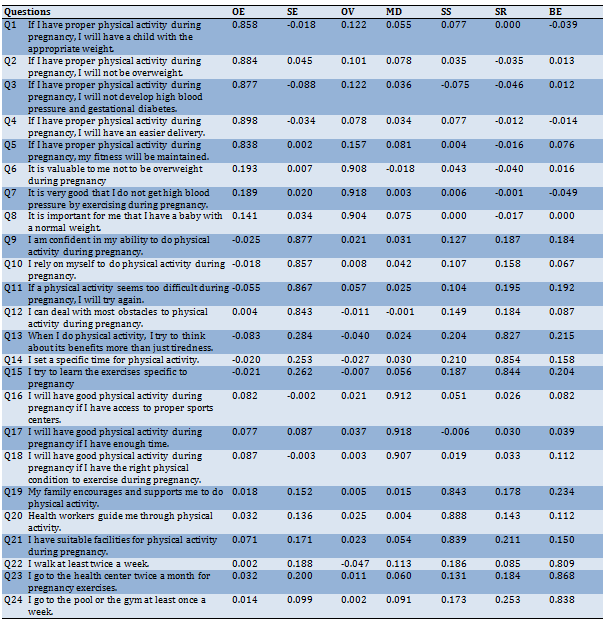

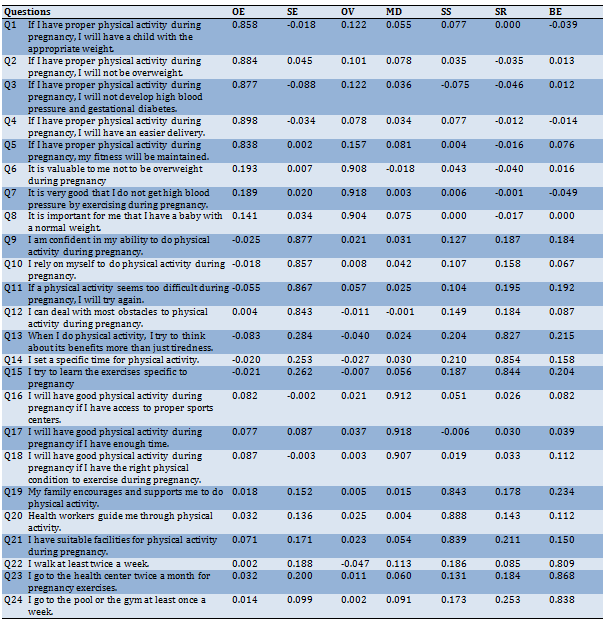

Table 2) Exploratory factor analysis of the PAP-SCT (n=240)

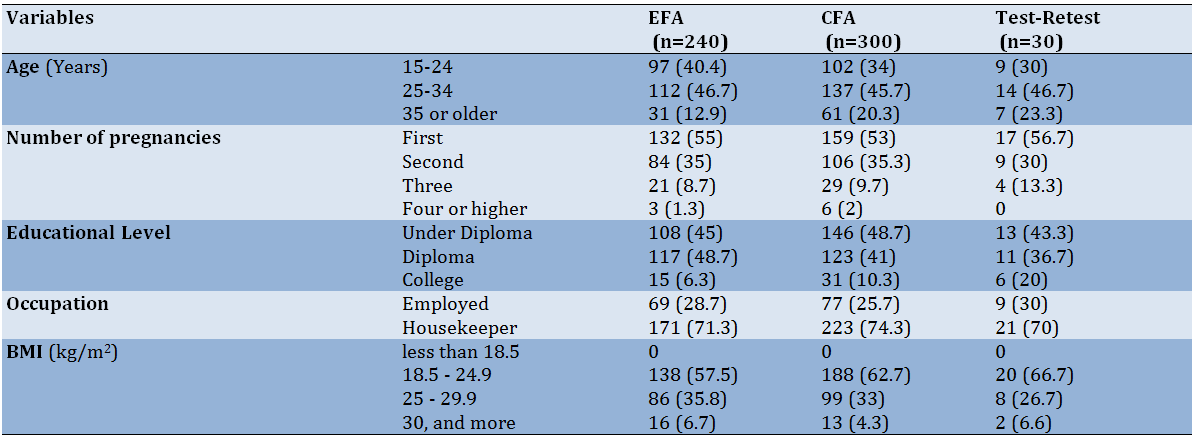

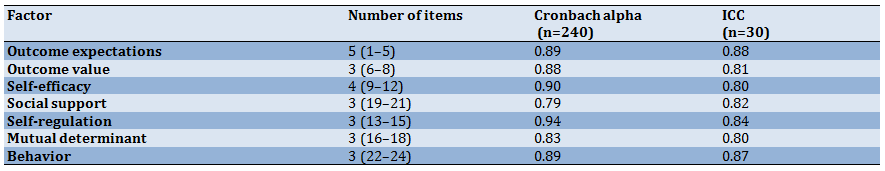

Table 3) Internal consistency and stability

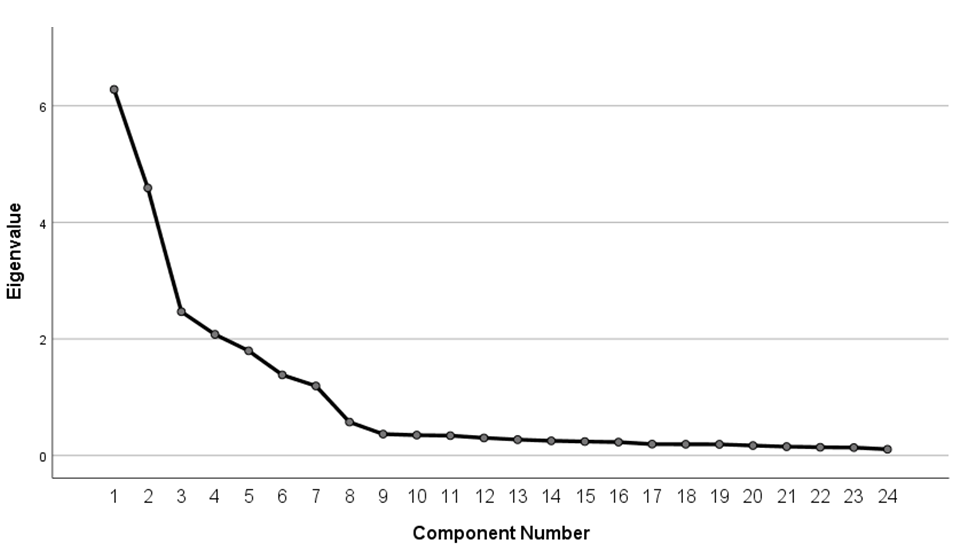

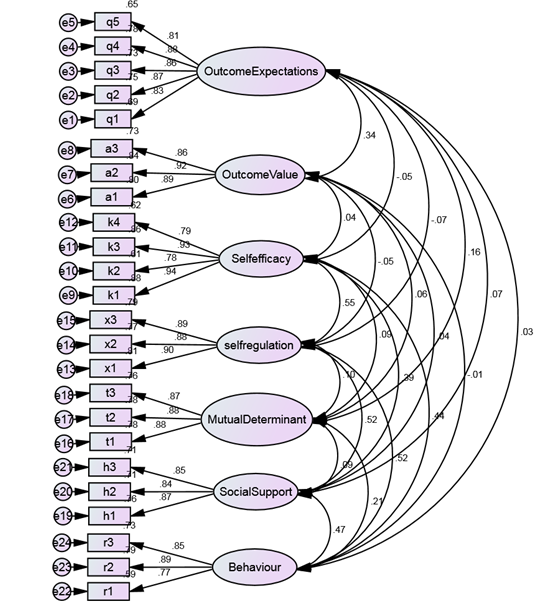

Figure 1) An obtained model for the questionnaire from the confirmatory factor analysis (n=300)

Full-Text: (459 Views)

Introduction

Physical activity (PA), as defined by the World Health Organization, is described as any movement requiring energy expenditure conducted by skeletal muscles, which includes exercise, work, family, and leisure activities [1]. The reduction in physical activity is rising in many countries around the world, which has a significant influence on health including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity [2]. Overall, a quarter of the world's female population does not reach the recommended levels of physical activity [3]. Pregnancy is a period in a woman's life when her physiological, physical, and psychological systems adapt to meet the growing needs of fetal [4, 5]. These adaptive changes can result in many pregnancy-related health issues such as gestational diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and maternal obesity [6]. For pregnant women, 30 minutes (or more) of moderate daily exercise is suggested by the American College of Obstetricians, and Gynecologists [7]. Pregnant women, who meet the recommended PA levels during their pregnancy, have a lower risk of the health problems listed above [8].

Moderate PA is beneficial for maternal, and fetal health among pregnant women [9]. Physical activity has been linked to several health benefits during pregnancy including the metabolism improvement of both the mother, and fetus, the enhancement of cardiopulmonary function, higher mother-infant immunity, the increase of nervous system function in pregnant mothers, physical fitness improvement or maintenance, the reduction of depression symptoms, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia. Although physical activity has many health benefits during pregnancy, few women engage in regular physical activity during pregnancy [10-12].

Several factors are avoiding PA during pregnancy such as behavioral intention, and attitude, fatigue, self-efficacy for behavior change, change in body shape, pregnancy-related symptoms, the lack of information, lack of time, and social support [13-17].

One of the most potent theories commonly used to anticipate, and show behaviors, is Albert Bandura's social cognitive theory (SCT). SCT emphasizes that personal, and environmental features modify behavior. This theory also considers the two-way interactions of person, behavior, and environment. It provides solutions to change behavior by determining the predictors, and effective principles in shaping behavior [18]. This study aimed to identify the factors affecting the physical activity of pregnant women based on the framework of social cognitive theory, and provide a standard, and practical tool for further research.

Instrument and Methods

The research was conducted in two stages. Items were designed to expand the scale in the initial phase (in the Persian language). Based on the structures of social cognitive theory, a qualitative study was done to develop key suggestions for potential elements of physical activity in pregnant women. After determining the most appropriate phrase for each element, the validity of the face, and content were evaluated.

The items were administered from a new sample in the second phase. To begin, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to determine the major factor structure, and items with insufficient loadings were removed. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then used to assess the coherence between the data, and the structure. To ensure that the final instrument's factor structure was correct, it was administered to an independent sample. Following that, an independent sample of 30 pregnant women was used to assess test-retest reliability.

Phase 1: Item generation, and instrument development phase

A qualitative study was done to build a scale for measuring physical activity based on structures of social cognitive theory in pregnant women. Two focus group discussions (FGD) among 16 pregnant women (8 members per each group), and 9 semi-structured interviews were done with an emphasis on physical activity based on structures of SCT. Overall, 16 pregnant women (Mean= 28.13, SD=6.48) were recruited who were referred to health centers in Karaj from January through April 2021. To maximize diversity, interviews were performed with women who had different demographic characteristics (age, number of pregnancies, socioeconomic background), and these questions have been asked in group discussions. What is your view on physical activity during pregnancy? Why is physical activity important in pregnancy? What do you think are the important consequences of physical activity in pregnancy? What are the barriers to physical activity during pregnancy? What are the important facilitators of physical activity in pregnancy? What individual factors can contribute to physical activity in pregnancy? How can people around you help you with physical activity during pregnancy? What do you think are the best exercises for pregnancy? This information was utilized to create the item's phrasing.

-Data analysis: Themes were clustered based on SCT structures, and participants' views about physical activity. The primary codes and categories are used to identify themes. As such, the interviews are the analysis units. During the data collection process, data analysis began. Before proceeding to the next FGD or interview, each FGD, and the individual interview was analyzed. As mentioned above, the findings of the focus groups and individual interviews were used to develop the first draft of the scale. The pre-final draft of the physical activity in pregnant women based on the social cognitive theory Scale (PAP-SCT) contained 36 items (in the Persian language) that could be graded on a 5-point scale. The pre-final version of the scale was then tested for content, and face validity.

-Content validity: For PAP-SCT, we used both qualitative, and quantitative content validity. The instrument was evaluated in terms of wording, item allocation, grammar, and scaling during the qualitative phase. The content validity index (CVI), and the content validity ratio (CVR) were assessed during the quantitative phase. The items' clarity, simplicity, and relevance were determined using a CVI assessment. A Likert-type ordinal scale with four potential responses was used to calculate the CVI. The responses were graded on a scale of 1 (not relevant, not simple, and not clear) to 4 (very relevant, very simple, and very clear). The CVI was calculated as the proportion of items rated 3 or 4 by experts. Each item had to have a CVI score of at least 0.79 to be considered acceptable. In addition, the CVR assessed the essentiality of each item. Experts for measuring the CVR rated each item as 1=essential, 2=useful but not essential, or 3=not essential. Any item with a CVR greater than 0.78 was considered to be satisfactory and was kept [19]. In total, eleven items were deleted, resulting in a 25-item scale.

-Face validity: Qualitative, and quantitative approaches have been utilized to assess the face validity of the PAP-SCT. In the qualitative stage, twelve pregnant women have been requested to assess every item of the PAP-SCT, and whether they found it difficult or ambiguous to respond to the questions. On the first of the views of the participants, vague items have been revised. The impact score (frequency × importance) was generated during the quantitative phase to indicate the percentage of women who identified items on a five-point Likert scale as important or very important. It was regarded appropriate if an item's impact score was 1.5 or above. One item got an impact score of less than1.5, and 24 items had an impact score of 1.8 to 5. As a result, the instrument's original version included 24 items.

Phase 2: Psychometric evaluation of the Physical activity in pregnant women based on the social cognitive theory Scale (PAP-SCT)

A cross-sectional study was done to investigate the psychometric features of PAP-SCT in a larger setting in Karaj, Iran, from January to April 2021. Participants included pregnant women referred to health centers. 300 pregnant women referring to health centers were selected by multistage random sampling method. After providing information about the research objectives, pregnant women who have accepted to participate, have completed the PAP-SCT.

-Statistical analysis: Some statistical methods have been carried out to assess the psychometric properties of the PAP-SCT. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 20 and AMOS 23 software. They are presented as follows.

-Construct validity: Following the item analysis, the final 24 items were utilized to measure construct validity using EFA, and CFA. The EFA was used to determine the main factors of the PAP-SCT. The number of samples required to perform the EFA is 5 to 10 people per item. Since the PAP-SCT has 24 items, 240 pregnant women were recruited for the EFA phase. To determine the sample's adequacy for factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), and Bartlett's sphericity tests were used. For factor extraction, any factor with an eigenvalue greater than one was considered acceptable [20].

-Confirmatory factor analysis: The coherence between the data, and the structure was assessed using a CFA [21]. The model fit was assessed using several fit indices such as chi-square (Chi-Square/df), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness of fit (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), tucker-lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), relative fit index (RFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The TLI, CFI, IFI, RFI, and NFI ranged between 0, and 1, but the value of 0.9 or higher are generally considered appropriate. An RMSEA value below 0.08 represents a good fit. The appropriate value for the Chi-square/df index should be less than 3. Also, the GFI and AGFI ranged between 0, and 1, but values of 0.8 or higher are typically regarded as acceptable [22].

-Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was utilized to assess the internal consistency of each subscale of the PAP-SCT (outcome expectations, outcome value, self-efficacy, social support, self-regulation, mutual determinant, and behavior). Alpha values of 0.70 or higher were considered suitable [23].

-Test-retest reliability: The PAP-SCT stability was evaluated via test-retest reliability. Thirty pregnant women participated in this stage; they completed the PAP-SCT questionnaire. After two weeks, they completed the questionnaires again.

Findings

Two hundred-forty pregnant women were participating in the EFA phase. The mean age of the women was 28.11±6.54 years. Almost half of the women were aged between 25, and 34 years, and experiencing their first pregnancy. The demographic properties of pregnant women in the three analyses are described in Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis

The measurement of the adequacy of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) was 0.837, and Bartlett’s sphericity test was χ2=4410.72, which indicates that the sample was adequate for EFA. For the 24-item scale, seven factors revealed eigenvalues greater than 1 (Diagram 1).

Subsequently, item loads were measured, and a seven-factor scale was generated. Table 2 shows that seven factors were identified: factor 1 (outcome expectations) included 5 items, factor 2 (outcome value) included 3 items, factor 3 (self-efficacy) included 4 items, factor 4 (social support) included 3 items, factor 5 (self-regulation) included 3 items, factor 6 (mutual determinant included 3 items, and factor 7 (behavior) included 3 items.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

A CFA was carried out on the 24-item scale to check the fitness of the model derived from the EFA. The measurement model provided a good fit (Figure 1). The χ2/df was equal to 1.47, RMSEA=0.045, which was lower than 0.08, thus indicating a good fit of the model. The CFI, TLI, IFI, RFI, and NFI were higher than 0.90 (0.97, 0.96, 0.97, 0.91, and 0.92 respectively). The GFI and AGFI were higher than 0.80 (0.97, and 0.85 respectively).

Reliability

To measure reliability, the Cronbach alpha was calculated for each subscale of the PAP-SCT. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the PAP-SCT subscales ranged from 0.83 to 0.94. As a result, no items from the questionnaire were removed during this step.

Furthermore, a test-retest analysis was done to check the stability of the instrument. The results indicate satisfactory reliability. The test-retest correlation coefficient was 0.86 for the PAP-SCT, and for the subscales ranged from 0.80 to 0.88.

The results of the reliability tests were reported in Table 3.

Physical activity (PA), as defined by the World Health Organization, is described as any movement requiring energy expenditure conducted by skeletal muscles, which includes exercise, work, family, and leisure activities [1]. The reduction in physical activity is rising in many countries around the world, which has a significant influence on health including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity [2]. Overall, a quarter of the world's female population does not reach the recommended levels of physical activity [3]. Pregnancy is a period in a woman's life when her physiological, physical, and psychological systems adapt to meet the growing needs of fetal [4, 5]. These adaptive changes can result in many pregnancy-related health issues such as gestational diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and maternal obesity [6]. For pregnant women, 30 minutes (or more) of moderate daily exercise is suggested by the American College of Obstetricians, and Gynecologists [7]. Pregnant women, who meet the recommended PA levels during their pregnancy, have a lower risk of the health problems listed above [8].

Moderate PA is beneficial for maternal, and fetal health among pregnant women [9]. Physical activity has been linked to several health benefits during pregnancy including the metabolism improvement of both the mother, and fetus, the enhancement of cardiopulmonary function, higher mother-infant immunity, the increase of nervous system function in pregnant mothers, physical fitness improvement or maintenance, the reduction of depression symptoms, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia. Although physical activity has many health benefits during pregnancy, few women engage in regular physical activity during pregnancy [10-12].

Several factors are avoiding PA during pregnancy such as behavioral intention, and attitude, fatigue, self-efficacy for behavior change, change in body shape, pregnancy-related symptoms, the lack of information, lack of time, and social support [13-17].

One of the most potent theories commonly used to anticipate, and show behaviors, is Albert Bandura's social cognitive theory (SCT). SCT emphasizes that personal, and environmental features modify behavior. This theory also considers the two-way interactions of person, behavior, and environment. It provides solutions to change behavior by determining the predictors, and effective principles in shaping behavior [18]. This study aimed to identify the factors affecting the physical activity of pregnant women based on the framework of social cognitive theory, and provide a standard, and practical tool for further research.

Instrument and Methods

The research was conducted in two stages. Items were designed to expand the scale in the initial phase (in the Persian language). Based on the structures of social cognitive theory, a qualitative study was done to develop key suggestions for potential elements of physical activity in pregnant women. After determining the most appropriate phrase for each element, the validity of the face, and content were evaluated.

The items were administered from a new sample in the second phase. To begin, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to determine the major factor structure, and items with insufficient loadings were removed. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then used to assess the coherence between the data, and the structure. To ensure that the final instrument's factor structure was correct, it was administered to an independent sample. Following that, an independent sample of 30 pregnant women was used to assess test-retest reliability.

Phase 1: Item generation, and instrument development phase

A qualitative study was done to build a scale for measuring physical activity based on structures of social cognitive theory in pregnant women. Two focus group discussions (FGD) among 16 pregnant women (8 members per each group), and 9 semi-structured interviews were done with an emphasis on physical activity based on structures of SCT. Overall, 16 pregnant women (Mean= 28.13, SD=6.48) were recruited who were referred to health centers in Karaj from January through April 2021. To maximize diversity, interviews were performed with women who had different demographic characteristics (age, number of pregnancies, socioeconomic background), and these questions have been asked in group discussions. What is your view on physical activity during pregnancy? Why is physical activity important in pregnancy? What do you think are the important consequences of physical activity in pregnancy? What are the barriers to physical activity during pregnancy? What are the important facilitators of physical activity in pregnancy? What individual factors can contribute to physical activity in pregnancy? How can people around you help you with physical activity during pregnancy? What do you think are the best exercises for pregnancy? This information was utilized to create the item's phrasing.

-Data analysis: Themes were clustered based on SCT structures, and participants' views about physical activity. The primary codes and categories are used to identify themes. As such, the interviews are the analysis units. During the data collection process, data analysis began. Before proceeding to the next FGD or interview, each FGD, and the individual interview was analyzed. As mentioned above, the findings of the focus groups and individual interviews were used to develop the first draft of the scale. The pre-final draft of the physical activity in pregnant women based on the social cognitive theory Scale (PAP-SCT) contained 36 items (in the Persian language) that could be graded on a 5-point scale. The pre-final version of the scale was then tested for content, and face validity.

-Content validity: For PAP-SCT, we used both qualitative, and quantitative content validity. The instrument was evaluated in terms of wording, item allocation, grammar, and scaling during the qualitative phase. The content validity index (CVI), and the content validity ratio (CVR) were assessed during the quantitative phase. The items' clarity, simplicity, and relevance were determined using a CVI assessment. A Likert-type ordinal scale with four potential responses was used to calculate the CVI. The responses were graded on a scale of 1 (not relevant, not simple, and not clear) to 4 (very relevant, very simple, and very clear). The CVI was calculated as the proportion of items rated 3 or 4 by experts. Each item had to have a CVI score of at least 0.79 to be considered acceptable. In addition, the CVR assessed the essentiality of each item. Experts for measuring the CVR rated each item as 1=essential, 2=useful but not essential, or 3=not essential. Any item with a CVR greater than 0.78 was considered to be satisfactory and was kept [19]. In total, eleven items were deleted, resulting in a 25-item scale.

-Face validity: Qualitative, and quantitative approaches have been utilized to assess the face validity of the PAP-SCT. In the qualitative stage, twelve pregnant women have been requested to assess every item of the PAP-SCT, and whether they found it difficult or ambiguous to respond to the questions. On the first of the views of the participants, vague items have been revised. The impact score (frequency × importance) was generated during the quantitative phase to indicate the percentage of women who identified items on a five-point Likert scale as important or very important. It was regarded appropriate if an item's impact score was 1.5 or above. One item got an impact score of less than1.5, and 24 items had an impact score of 1.8 to 5. As a result, the instrument's original version included 24 items.

Phase 2: Psychometric evaluation of the Physical activity in pregnant women based on the social cognitive theory Scale (PAP-SCT)

A cross-sectional study was done to investigate the psychometric features of PAP-SCT in a larger setting in Karaj, Iran, from January to April 2021. Participants included pregnant women referred to health centers. 300 pregnant women referring to health centers were selected by multistage random sampling method. After providing information about the research objectives, pregnant women who have accepted to participate, have completed the PAP-SCT.

-Statistical analysis: Some statistical methods have been carried out to assess the psychometric properties of the PAP-SCT. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 20 and AMOS 23 software. They are presented as follows.

-Construct validity: Following the item analysis, the final 24 items were utilized to measure construct validity using EFA, and CFA. The EFA was used to determine the main factors of the PAP-SCT. The number of samples required to perform the EFA is 5 to 10 people per item. Since the PAP-SCT has 24 items, 240 pregnant women were recruited for the EFA phase. To determine the sample's adequacy for factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), and Bartlett's sphericity tests were used. For factor extraction, any factor with an eigenvalue greater than one was considered acceptable [20].

-Confirmatory factor analysis: The coherence between the data, and the structure was assessed using a CFA [21]. The model fit was assessed using several fit indices such as chi-square (Chi-Square/df), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness of fit (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), tucker-lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), relative fit index (RFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The TLI, CFI, IFI, RFI, and NFI ranged between 0, and 1, but the value of 0.9 or higher are generally considered appropriate. An RMSEA value below 0.08 represents a good fit. The appropriate value for the Chi-square/df index should be less than 3. Also, the GFI and AGFI ranged between 0, and 1, but values of 0.8 or higher are typically regarded as acceptable [22].

-Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was utilized to assess the internal consistency of each subscale of the PAP-SCT (outcome expectations, outcome value, self-efficacy, social support, self-regulation, mutual determinant, and behavior). Alpha values of 0.70 or higher were considered suitable [23].

-Test-retest reliability: The PAP-SCT stability was evaluated via test-retest reliability. Thirty pregnant women participated in this stage; they completed the PAP-SCT questionnaire. After two weeks, they completed the questionnaires again.

Findings

Two hundred-forty pregnant women were participating in the EFA phase. The mean age of the women was 28.11±6.54 years. Almost half of the women were aged between 25, and 34 years, and experiencing their first pregnancy. The demographic properties of pregnant women in the three analyses are described in Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis

The measurement of the adequacy of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) was 0.837, and Bartlett’s sphericity test was χ2=4410.72, which indicates that the sample was adequate for EFA. For the 24-item scale, seven factors revealed eigenvalues greater than 1 (Diagram 1).

Subsequently, item loads were measured, and a seven-factor scale was generated. Table 2 shows that seven factors were identified: factor 1 (outcome expectations) included 5 items, factor 2 (outcome value) included 3 items, factor 3 (self-efficacy) included 4 items, factor 4 (social support) included 3 items, factor 5 (self-regulation) included 3 items, factor 6 (mutual determinant included 3 items, and factor 7 (behavior) included 3 items.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

A CFA was carried out on the 24-item scale to check the fitness of the model derived from the EFA. The measurement model provided a good fit (Figure 1). The χ2/df was equal to 1.47, RMSEA=0.045, which was lower than 0.08, thus indicating a good fit of the model. The CFI, TLI, IFI, RFI, and NFI were higher than 0.90 (0.97, 0.96, 0.97, 0.91, and 0.92 respectively). The GFI and AGFI were higher than 0.80 (0.97, and 0.85 respectively).

Reliability

To measure reliability, the Cronbach alpha was calculated for each subscale of the PAP-SCT. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the PAP-SCT subscales ranged from 0.83 to 0.94. As a result, no items from the questionnaire were removed during this step.

Furthermore, a test-retest analysis was done to check the stability of the instrument. The results indicate satisfactory reliability. The test-retest correlation coefficient was 0.86 for the PAP-SCT, and for the subscales ranged from 0.80 to 0.88.

The results of the reliability tests were reported in Table 3.

Table1) Participant's demographic characteristics in three stages (Numbers in parentheses are in percent)

Diagram 1) Scree plot for determining the factors

Table 2) Exploratory factor analysis of the PAP-SCT (n=240)

Table 3) Internal consistency and stability

Figure 1) An obtained model for the questionnaire from the confirmatory factor analysis (n=300)

Discussion

In this study, we developed a physical activity scale for pregnant women (PAP-SCT). This is the first study to develop a scale for measuring physical activity based on social cognitive theory in Iranian pregnant women. Results from this study demonstrated that PAP-SCT can predict physical activity during pregnancy; so 52% of the variance of physical activity can be explained by this scale.

The scale's content was originally constructed based on a qualitative investigation to ensure that it encompassed all theoretical topics linked to physical exercise. Following EFA, a seven-domain scale was developed. The fit of the data was acceptable, according to the CFA. As a result, there were 24 items on the final PAP-SCT scale, with 5 items representing outcome expectations, 3 items representing outcome value, 4 items representing self-efficacy, 3 items representing social support, 3 items representing self-regulation, and 3 items representing mutual determinant, and 3 items representing behavior.

Self-efficacy indicates beliefs about personal ability to perform behaviors that bring desired outcomes. People with high self-efficacy show a greater tendency to participate in challenging behaviors [24]. Based on the results of the final model, self-efficacy had the highest effect on physical activity in pregnant women; it predicted a 41% variance in physical activity. This finding is consistent with the assumptions of Bandura's social cognitive theory that self-efficacy is the strongest construct in predicting individual behavior change [25]. In the study of Mahmoodi et al., which examined the factors explaining regular physical activity based on social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is the most important predictor of physical activity [26].

The concept of outcome expectations is the belief about the likelihood, and value of the consequences of behavioral choices [24]. In this study, the outcome expectations were predicted as 18% of the variance of physical activity in pregnant women. Son et al. have found that the outcome expectations are most effective in performing physical activities in individuals [27]. In the study of Mirkarimi et al., a positive relationship was observed between outcome expectations, and physical activity behavior [28].

According to Bandura, self-regulation is defined as controlling oneself through self-monitoring, goal-setting, feedback, self-reward, self-instruction, and enlistment of social support [24]. In the present study, the self-regulatory predicted 32% of the variance of physical activity behavior in pregnant women. The results of Peyman et al. showed that self-regulation has a significant relationship with physical activity [29]. In the study by Wadsworth et al., self-regulation was an important predictor of women's physical activity behavior [30]. Joseph et al. reported that there was a significant relationship between physical activity and self-regulation in female students [31].

The concept of outcome expectations is defined as environmental factors that influence individuals, and groups, but individuals, and groups can also influence their environments, and regulate their behavior [24]. In the present study, the mutual determinant construct predicted 15% of the variance of physical activity in pregnant women. The study by Bashirian et al. Reported that the construct of mutual determinants predicts healthy eating behavior in pregnant women [32].

Social support is the perception, and actuality that one is cared for, has assistance available from other people, and most popularly, that one is part of a supportive social network. These supportive resources can be emotional, informational, or companionship [24]. Studies have shown that social support during pregnancy is associated with better mental health, and these people are better able to adapt to problems. In this study, the social support structure predicted 26% of the variance of physical activity in pregnant women. Taecha showed a positive, and significant effect of social support on physical activity [33]. Hosseini's study showed that increasing social support leads to improved health-promoting behaviors [34].

The concept of outcome value refers to the degree of satisfaction obtained from the outcome of behavior. In the present study, the construct outcome value predicted 12% of the variance of physical activity behavior in pregnancy. In a study of Rajabalipour, the construct of outcome value was the predictor for behavior [35]. In Aghdasi et al.'s study, which was conducted to determine the effect of education based on social cognitive theory, the construct of outcome value had a significant relationship with behavior [36].

Ardestani et al. investigated the validity, and reliability of a scale based on SCT for assessing adolescent girls' physical activity behavior. They showed a six-factor structure comprising self-efficacy, self-regulation, family support, friend support, outcome expectancy, and self-efficacy in overcoming impediments. The SCT model was fitted to the data based on factor loadings, t-values, and fit indices [37]. Ramirez et al. after performing the confirmatory factor analysis, four factors were obtained including self-efficacy, outcome expectations, social support, and barriers. In addition, their findings backed up the usage of SCT components to better understand physical activity behavior [38].

Internal consistency was shown to be excellent in reliability analyses. As a result, we believe a PAP-SCT scale is a novel tool for assessing physical activity in pregnant women. Based on social cognitive theory, Ramirez et al. validated the scale with five factors (self-efficacy, outcome expectations, social support, barriers, and goals). The confirmatory factor analyses revealed that the model had a good fit for the data [38].

In general, our findings revealed that the PAP-SCT had acceptable psychometric properties. The content validity was found to be satisfactory using the CVI, and CVR. Furthermore, the CFA showed that the present model had good fit indices. Cronbach's alpha coefficient demonstrated satisfactory reliability in the final scale. In addition, the ICC score demonstrated adequate stability for the scale when it was tested by 30 pregnant women over 2 weeks.

Conclusion

The PAP-SCT is a useful scale for understanding what factors influence pregnant women's physical activity. As a result, we anticipate that this newly established scale will be especially useful for health care teams in analyzing, and designing practical situations.

Acknowledgments: This paper was part of the Ph.D. thesis of Zohreh Arefi in the field of health education, and promotion at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors appreciate all women who participated in this research.

Ethical Permissions: This research was accepted by the Ethics Board of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1397.246. All women were made aware of the goals of the research, and signed the consent form.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare

Authors’ Contributions: Arefi Z (First author), Introduction writer/Main Researcher/Discussion writer (25%); Sadeghi R (Second author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (25%), Shojaeizadeh D (Third author), Methodologist (20%); Yaseri M (Fourth author), Statistical Analyst (15%); Shahbazi Sighaldeh Sh (Fifth author), Discussion writer (15%)

Funding/Support: The study was supported financially by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

In this study, we developed a physical activity scale for pregnant women (PAP-SCT). This is the first study to develop a scale for measuring physical activity based on social cognitive theory in Iranian pregnant women. Results from this study demonstrated that PAP-SCT can predict physical activity during pregnancy; so 52% of the variance of physical activity can be explained by this scale.

The scale's content was originally constructed based on a qualitative investigation to ensure that it encompassed all theoretical topics linked to physical exercise. Following EFA, a seven-domain scale was developed. The fit of the data was acceptable, according to the CFA. As a result, there were 24 items on the final PAP-SCT scale, with 5 items representing outcome expectations, 3 items representing outcome value, 4 items representing self-efficacy, 3 items representing social support, 3 items representing self-regulation, and 3 items representing mutual determinant, and 3 items representing behavior.

Self-efficacy indicates beliefs about personal ability to perform behaviors that bring desired outcomes. People with high self-efficacy show a greater tendency to participate in challenging behaviors [24]. Based on the results of the final model, self-efficacy had the highest effect on physical activity in pregnant women; it predicted a 41% variance in physical activity. This finding is consistent with the assumptions of Bandura's social cognitive theory that self-efficacy is the strongest construct in predicting individual behavior change [25]. In the study of Mahmoodi et al., which examined the factors explaining regular physical activity based on social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is the most important predictor of physical activity [26].

The concept of outcome expectations is the belief about the likelihood, and value of the consequences of behavioral choices [24]. In this study, the outcome expectations were predicted as 18% of the variance of physical activity in pregnant women. Son et al. have found that the outcome expectations are most effective in performing physical activities in individuals [27]. In the study of Mirkarimi et al., a positive relationship was observed between outcome expectations, and physical activity behavior [28].

According to Bandura, self-regulation is defined as controlling oneself through self-monitoring, goal-setting, feedback, self-reward, self-instruction, and enlistment of social support [24]. In the present study, the self-regulatory predicted 32% of the variance of physical activity behavior in pregnant women. The results of Peyman et al. showed that self-regulation has a significant relationship with physical activity [29]. In the study by Wadsworth et al., self-regulation was an important predictor of women's physical activity behavior [30]. Joseph et al. reported that there was a significant relationship between physical activity and self-regulation in female students [31].

The concept of outcome expectations is defined as environmental factors that influence individuals, and groups, but individuals, and groups can also influence their environments, and regulate their behavior [24]. In the present study, the mutual determinant construct predicted 15% of the variance of physical activity in pregnant women. The study by Bashirian et al. Reported that the construct of mutual determinants predicts healthy eating behavior in pregnant women [32].

Social support is the perception, and actuality that one is cared for, has assistance available from other people, and most popularly, that one is part of a supportive social network. These supportive resources can be emotional, informational, or companionship [24]. Studies have shown that social support during pregnancy is associated with better mental health, and these people are better able to adapt to problems. In this study, the social support structure predicted 26% of the variance of physical activity in pregnant women. Taecha showed a positive, and significant effect of social support on physical activity [33]. Hosseini's study showed that increasing social support leads to improved health-promoting behaviors [34].

The concept of outcome value refers to the degree of satisfaction obtained from the outcome of behavior. In the present study, the construct outcome value predicted 12% of the variance of physical activity behavior in pregnancy. In a study of Rajabalipour, the construct of outcome value was the predictor for behavior [35]. In Aghdasi et al.'s study, which was conducted to determine the effect of education based on social cognitive theory, the construct of outcome value had a significant relationship with behavior [36].

Ardestani et al. investigated the validity, and reliability of a scale based on SCT for assessing adolescent girls' physical activity behavior. They showed a six-factor structure comprising self-efficacy, self-regulation, family support, friend support, outcome expectancy, and self-efficacy in overcoming impediments. The SCT model was fitted to the data based on factor loadings, t-values, and fit indices [37]. Ramirez et al. after performing the confirmatory factor analysis, four factors were obtained including self-efficacy, outcome expectations, social support, and barriers. In addition, their findings backed up the usage of SCT components to better understand physical activity behavior [38].

Internal consistency was shown to be excellent in reliability analyses. As a result, we believe a PAP-SCT scale is a novel tool for assessing physical activity in pregnant women. Based on social cognitive theory, Ramirez et al. validated the scale with five factors (self-efficacy, outcome expectations, social support, barriers, and goals). The confirmatory factor analyses revealed that the model had a good fit for the data [38].

In general, our findings revealed that the PAP-SCT had acceptable psychometric properties. The content validity was found to be satisfactory using the CVI, and CVR. Furthermore, the CFA showed that the present model had good fit indices. Cronbach's alpha coefficient demonstrated satisfactory reliability in the final scale. In addition, the ICC score demonstrated adequate stability for the scale when it was tested by 30 pregnant women over 2 weeks.

Conclusion

The PAP-SCT is a useful scale for understanding what factors influence pregnant women's physical activity. As a result, we anticipate that this newly established scale will be especially useful for health care teams in analyzing, and designing practical situations.

Acknowledgments: This paper was part of the Ph.D. thesis of Zohreh Arefi in the field of health education, and promotion at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors appreciate all women who participated in this research.

Ethical Permissions: This research was accepted by the Ethics Board of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1397.246. All women were made aware of the goals of the research, and signed the consent form.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare

Authors’ Contributions: Arefi Z (First author), Introduction writer/Main Researcher/Discussion writer (25%); Sadeghi R (Second author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (25%), Shojaeizadeh D (Third author), Methodologist (20%); Yaseri M (Fourth author), Statistical Analyst (15%); Shahbazi Sighaldeh Sh (Fifth author), Discussion writer (15%)

Funding/Support: The study was supported financially by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2022/03/15 | Accepted: 2022/05/15 | Published: 2022/07/4

Received: 2022/03/15 | Accepted: 2022/05/15 | Published: 2022/07/4

References

1. Zhu G, Qian X, Qi L, Xia C, Ming Y, Zeng Z, et al. The intention to undertake physical activity in pregnant Women using the theory of planned behaviour. JAN. 2020;76(7):1647-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jan.14347]

2. Hailemariam TT, Gebregiorgis YS, Gebremeskel BF, Haile TG, Spitznagle TM. Physical activity, and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: Facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:92. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-2777-6]

3. Sallis J, Bull F, Guthold R, Heath G, Inoue S, Kelly P. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1325-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5]

4. da Silva SG, Ricardo LI, Evenson KR, Hallal PC. Leisure-time physical activity in pregnancy, and maternal-child health: a systematic review, and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, and cohort studies. Sports Med. 2017;47(2):295-317. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40279-016-0565-2]

5. Watson ED, van Poppel MN, Jones RA, Norris SA, Micklesfield LK. Are south African mothers moving? Patterns, and correlates of physical activity, and sedentary behavior in pregnant black south African women. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(5):329-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/jpah.2016-0388]

6. de Haas S, Ghossein‐Doha C, van Kuijk S, van Drongelen J, Spaanderman M. Physiological adaptation of maternal plasma volume during pregnancy: A systematic review, and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(2):177-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/uog.17360]

7. Obstetricians ACo, Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 650: Physical activity, and exercise during pregnancy, and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):e135-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001214]

8. Okafor UB, Goon DT. Developing a physical activity intervention strategy for pregnant women in Buffalo City Municipality, South Africa: A study protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6694. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17186694]

9. Ribeiro MM, Andrade A, Nunes I. Physical exercise in pregnancy: Benefits, risks, and prescription. J Perinat Med. 2022;50(1):4-17. [Link] [DOI:10.1515/jpm-2021-0315]

10. Davenport MH, Ruchat SM, Sobierajski F, Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Yoo C, et al. Impact of prenatal exercise on maternal harms, labour, and delivery outcomes: A systematic review, and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(2):99-107. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099821]

11. Bauer I, Hartkopf J, Kullmann S, Schleger F, Hallschmid M, Pauluschke-Fröhlich J, et al. Spotlight on the fetus: How physical activity during pregnancy influences fetal health: A narrative review. BMJ Open Sport Exer Med. 2020;6(1):e000658. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000658]

12. Pathirathna ML, Sekijima K, Sadakata M, Fujiwara N, Muramatsu Y, Wimalasiri K. Effects of physical activity during pregnancy on neonatal birth weight. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6000. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-42473-7]

13. Merkx A, Ausems M, Budé L, de Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze MJ. Factors affecting perceived change in physical activity in pregnancy. Midwifery. 2017;51:16-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.007]

14. Harrison AL, Taylor NF, Shields N, Frawley HC. Attitudes, barriers, and enablers to physical activity in pregnant women: A systematic review. J Physiother. 2018;64(1):24-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jphys.2017.11.012]

15. Ahmadi K, Amiri-Farahani L. The perceived barriers to physical activity in pregnant women: A review study. J Client Cent Nurs Care. 2021;7(4):245-54. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.7.4.253.2]

16. Koleilat M, Vargas N, van Twist V, Kodjebacheva GD. Perceived barriers to, and suggested interventions for physical activity during pregnancy among participants of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children(WIC) in Southern California. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:69. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-03553-7]

17. Toghiyani Z, Kazemi A, Nekuei N. Physical activity for healthy pregnancy among Iranian women: Perception of facilities versus perceived barriers. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8. [Link]

18. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior, and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th Edition. New York: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Link]

19. Almanasreh E, Moles R, Chen TF. Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Rese Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(2):214-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.03.066]

20. Watkins MW. Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice. J Black Psychol. 2018;44(3):219-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0095798418771807]

21. Orcan F. Exploratory, and confirmatory factor analysis: which one to use first?. J Measurement Evaluat Educ Psychol. 2018;9(4):414-21. [Link] [DOI:10.21031/epod.394323]

22. Civelek ME. Essentials of structural equation modeling. Essent Struct Equ Model. 2018 Feb. [Link] [DOI:10.13014/K2SJ1HR5]

23. McCrae RR, Kurtz JE, Yamagata S, Terracciano A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Person Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(1):28-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1088868310366253]

24. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Link]

25. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191-215. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191]

26. Mahmoodi H, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Babazadeh T, Mohammadi Y, Shirzadi S, Sharifi-Saqezi P, et al. Health promoting behaviors in pregnant women admitted to the prenatal care unit of imam khomeini hospital of saqqez. J Educ Community Health. 2015;1(4):58-65. [Link] [DOI:10.20286/jech-010458]

27. Son JS, Kerstetter DL, Mowen AJ, Payne LL. Global self-regulation, and outcome expectations: Influences on constraint self-regulation, and physical activity. J Aging Phys Act. 2009;17(3):307-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/japa.17.3.307]

28. Mirkarimi SK, Ozoni Doji R, Honarvar M, Aref LF. Correlation between physical activities, consumption of fruits, and vegetables, and using social cognitive theory constructs in obese or overweight women referring to health centers in Gorgan. Jorjani Biomed J. 2017;5(1):52-42. [Persian] [Link]

29. Peyman N, Mahdizadeh M, Taghipour A, Esmaily H. Using of social cognitive theory: predictors of physical activity among women with diabetestype 2. J Res Health. 2013;3(2):345-54. [Link]

30. Wadsworth DD, Hallam JS. Effect of a web site intervention on physical activity of college females. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(1):60-9. [Link] [DOI:10.5993/AJHB.34.1.8]

31. Joseph RP, Pekmezi DW, Lewis T, Dutton G, Turner LW, Durant NH. Physical activity, and social cognitive theory outcomes of an internet-enhanced physical activity intervention for African American female college students. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2013;6(2):1-8. [Link]

32. Bashirian S, Jalily M, Barati M. Nutritional behaviors status, and its related factors among pregnant women in Tabriz: A cross-sectional study. Pajouhan Sci J. 2016;14(2):34-43. [Persian] [Link]

33. Taechaboonsermsak P, Kaewkungwal J, Singhasivanon P, Fungladda W, Wilailak S. Causal relationship between health promoting behavior, and quality of life in cervical cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(6):1568. [Link]

34. Hosseini M, Ashktorab T, Taghdisi MH, Khodayari MT. The interpersonal influences as a factor for health promoting life style in nursing students: A mixed method study. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;9(5):196. [Link]

35. Rajabalipour M, Sharifi H, Nakhaee N, Iranpour A. Application of social cognitive theory to prevent waterpipe use in male high-school students in Kerman, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:186. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_235_17]

36. Adasi Z, Tehrani H, Esmaiely H, Ghavami M, Vahedian-Shahroodi M. Application of social cognitive theory on maternal nutritional behavior for weight of children 6 to 12 months with Failure to thrive (FTT). Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2021;9(2):145-58. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/ijhehp.9.2.145]

37. Ardestani M, Niknami S, Hidarnia A, Hajizadeh E. Psychometric properties of the Social Cognitive Theory questionnaire for physical activity in a sample of Iranian adolescent girl students. East Mediterranean Health J. 2016;22(5):318-26. [Link] [DOI:10.26719/2016.22.5.318]

38. Ramirez E, Kulinna PH, Cothran D. Constructs of physical activity behaviour in children: the usefulness of social cognitive theory. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(3):303-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.11.007]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |