Volume 10, Issue 4 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(4): 679-685 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Charkazi A, Allah Kalteh E, Yatimparvar G, Rahimzadeh H, Koochaki G, Shahini N, et al . Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy and its Associated Factors based on the Health Belief Model among Iranian People in 2021. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (4) :679-685

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60610-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60610-en.html

A. Charkazi1, E. Allah Kalteh2, G. Yatimparvar2, H. Rahimzadeh1, Gh. Koochaki3, N. Shahini4, M. Ahmadi-Livani5, A. Rajabi *  6

6

6

6

1- “Environmental Health Research Center” and “Faculty of Health”, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Infectious Disease Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

3- Department of Operating Room, Faculty of Allied Medical Sciences, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

4- Golestan Research Center of Psychiatry (GRCP), Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

5- Faculty of Health, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

6- “Health Management and Social Development Research Center” and “Faculty of Health”, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Infectious Disease Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

3- Department of Operating Room, Faculty of Allied Medical Sciences, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

4- Golestan Research Center of Psychiatry (GRCP), Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

5- Faculty of Health, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

6- “Health Management and Social Development Research Center” and “Faculty of Health”, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 1282 kb]

(3423 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2293 Views)

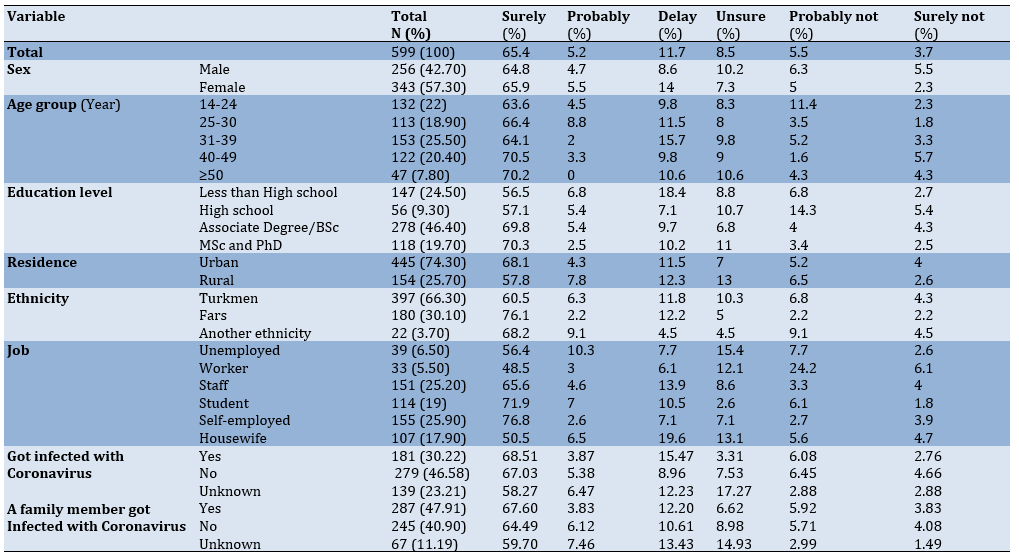

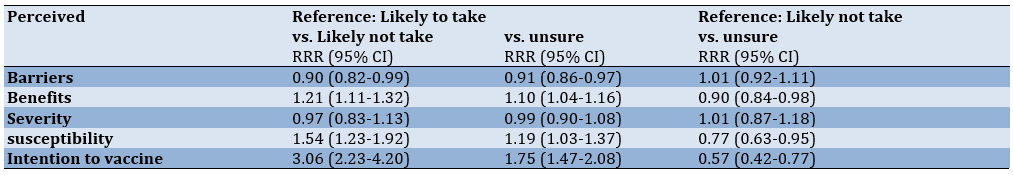

Table 1) Demographic characteristics and Likelihood of getting the COVID-19 vaccine of respondents (N=599)

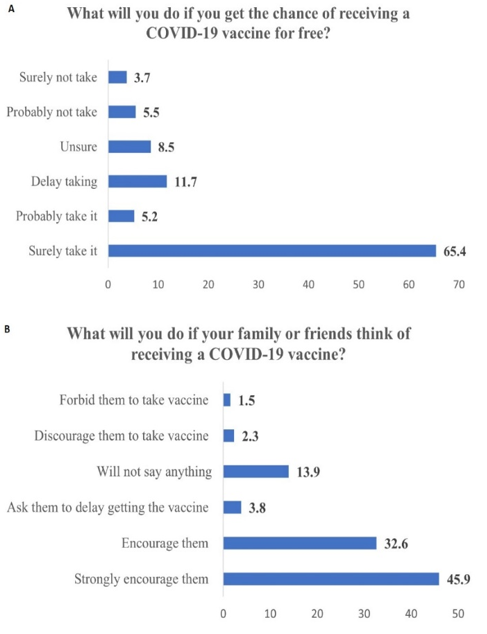

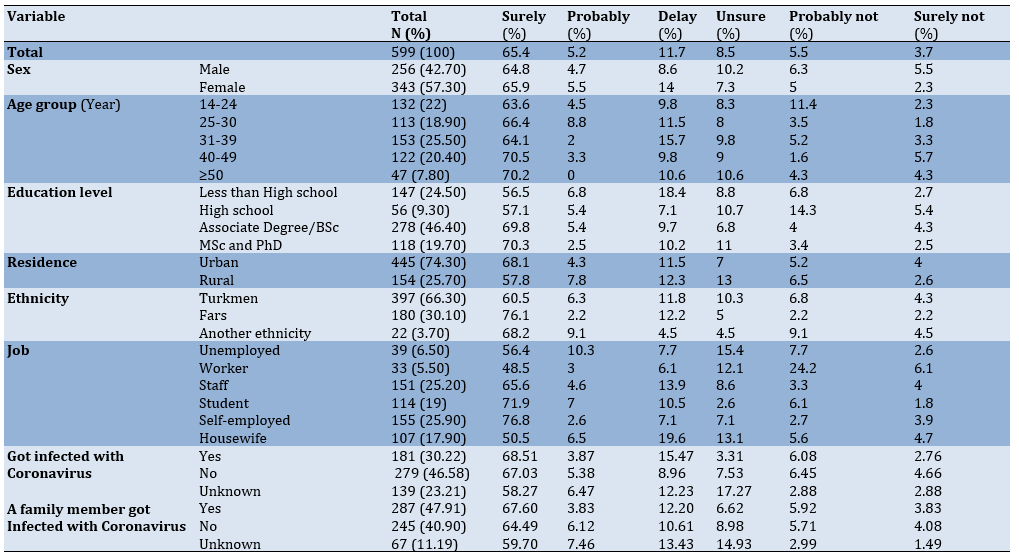

Figure 1) Prevalence (%) of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in respondents

Furthermore, 70.6% of the samples stated that they would definitely (65.4%) or possibly (5.2%) use the vaccine for free once it became available. 3.7% out of 9.2% of those who were unlikely to receive the vaccine said that they would definitely not use the vaccine, and 5.5% said that they would probably not use it. 8.5% and 11.7% said respectively that they were unsure about the use of the vaccine and would delay its use (Figure 1-A). Moreover, 78.5% of the total sample said that they encouraged their families or relatives to get COVID-19 vaccination, while only 1.5% of the samples prevented the vaccination of their relatives (Figure 1-B).

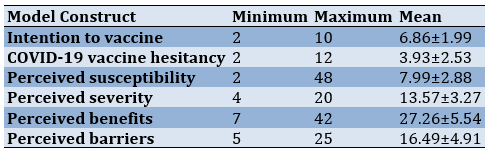

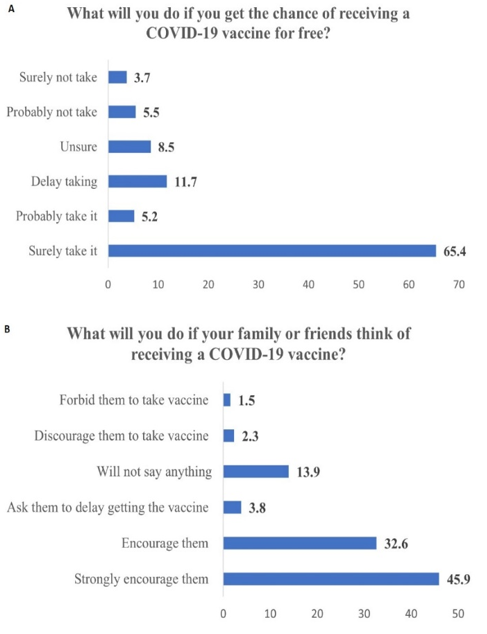

The mean of the hesitancy scale was equal to 3.93±2.53 based on the two questions. Based on these two questions (3.93/12*100), 32.75% of the samples had hesitancy about the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. Table 2 summarizes the results of the HBM.

Table 2) Scores obtained for model constructs (n=599)

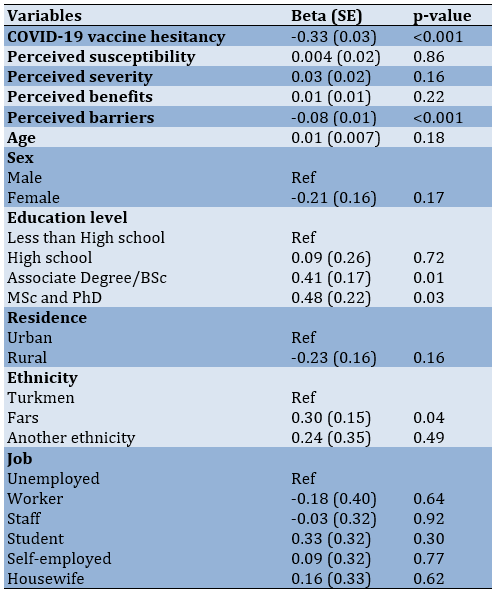

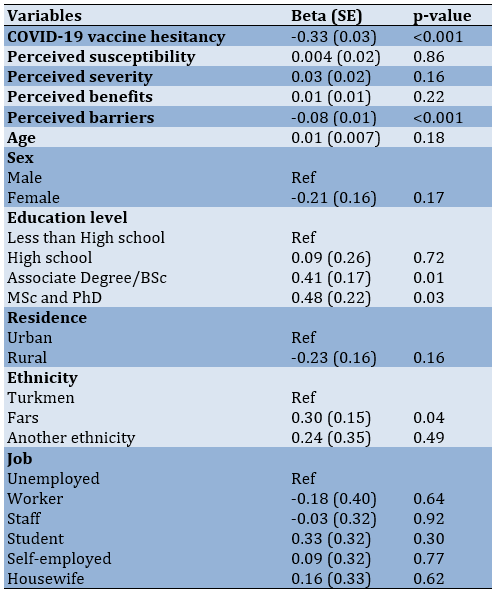

According to the relationship between different factors on the vaccination intention based on HBM, there was a kegative significant relationship between vaccination hesitancy and the existing barriers to vaccination intention. Based on the model, controlling the effects of demographic variables in our model indicated that the HBM constructs could predict 40% of the behavioral intention variance (Adj R-squared=0.40). So, the strongest predictors were vaccination hesitancy and the existing barriers (Table 3).

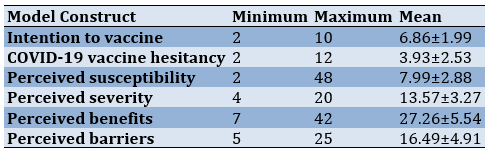

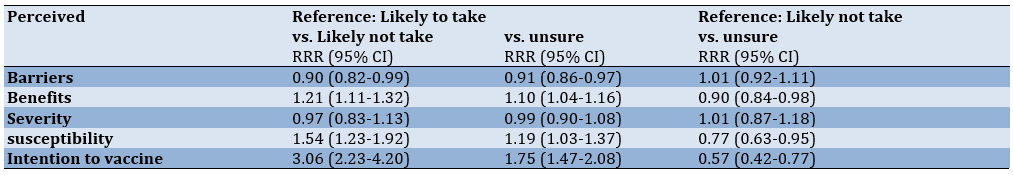

The relationship between HBM constructs with the probability of using the COVID-19 vaccine by polynomial logistic regression indicated that the perceived barriers were significantly related between the probability of using the vaccine and the probability of not using the vaccine, thereby reducing the probability of using the vaccine by 10%. (RRR=0.90, 95% CI: 0.82-0.99). Furthermore, perceived benefits (RRR=1.21, 95% CI: 1.11-1.32), perceived susceptibility (RRR= 1.54, 95% Cl: 1.23-1.92), and behavioral intention (RRR=3.06, 95% CI: 2.23-4.20) also had significant relationships with the probability of using the vaccine. The factors were associated with an increased probability of using the vaccine. They also existed in comparing the probability of using the vaccine with the

probability of not being sure about receiving the vaccine (Table 4).

Table 3) Results of the regression analysis of the dependent variable: intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine

Table 4) Multinomial regressions predicting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (n=599)

Discussion

Given the current status of society in Iran, which is currently involved with the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination has been carried out among the general public to overcome this pandemic. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and its relevant factors. The research results indicated that the rate of hesitancy in the injection of the COVID-19 vaccine in the research population was equal to 32.57%. In other words, about one-third of the participants had hesitancy about the vaccine injection. The results of a study by Hossain et al. indicated that the prevalence of vaccination hesitancy was 41.1% in Bangladesh, which was slightly higher than the present study [21]. This rate was 28.5% in a study by Lazarus et al. in 19 countries, and it was slightly less than the present study [22]. The results of a study in Saudi Arabia also indicated that 33.3% of people were reluctant to receive the vaccine [23]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the rate of non-acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine has been high in most studies. The present study shows the existence of obstacles to vaccination; among them, the ease of access and consultation of specialists, as well as the level of education, are related to hesitancy about the vaccination of Covid-19. In addition, literature review, this hesitancy and lack of vaccination can have several reasons such as the novelty of the vaccines, the lack of trust in them, and the fear of side effects of the vaccine. The results of a qualitative study on women released from prison in the United States indicated that the most important reasons for not receiving the anti-coronavirus vaccine were the lack of trust, the novelty of the vaccine, fear of its long-term effects, belief in the existence of electronic microchips in COVID-19 vaccines, their strong immune systems, no need for vaccines, and belief in diseases induced by COVID-19 vaccines [24]. The vaccine hesitancy was much lower in some studies than in the present study. For instance, the hesitancy rate was 20% in a study by Shmueli [25], 25% in a study by Dror et al. [26], and 31% in a study by Reiter et al. [27]. The first point to note about the differences in the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in different studies is the time to conduct or review the studies as recent studies have shown less hesitancy than earlier studies. As time goes by, public knowledge increases due to the exposure to information, and thus vaccination hesitancy decreases. The second point for these differences is whether vaccine hesitancy is assessed during the peak of COVID-19 in that society or during the control or steady status of the prevalence of COVID-19.

The results of the present study also indicated that if the COVID-19 vaccine was available for free, about 70% of the population would probably or definitely use it. Furthermore, 78.5% of the participants admitted that they would encourage family members or relatives to use the COVID-19 vaccine. A study by Prickett et al. in New Zealand also indicated that 71% of the population would probably use the COVID-19 vaccine if it became available [28], and their result was consistent with our study, indicating that there was not a significant difference in vaccine acceptance in different countries.

The results of this study also indicated that as the education level increased, vaccination hesitancy decreased. In other words, the higher education level significantly increased the rate of acceptance and adherence to vaccination. The finding was consistent with other studies [25, 29, 30]. A higher education level can increase health literacy and affect the individuals' health motivation. In the present study, the participants admitted that they would probably or not inject the vaccine if it was available for free, and the rate was higher in men (11.3%) than women (7.3%). However, a study by Sallam et al. [31] in Kuwait and Jordan showed that women were more likely than men not to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, the probability decreased with age, and it was consistent with other studies. The study of the probabilities in job groups also indicated that the highest level of hesitancy was seen among workers (30.3%). The finding is justifiable since most workers had lower education levels, indicating that hesitancy was higher in lower education.

Regarding the HBM constructs, the results indicated that there was a significant and inverse relationship between perceived barriers and intention to vaccinate so increasing perceived barriers to COVID-19 vaccination significantly reduced the vaccination intention. The results of a study in Bangladesh also indicated that as the perceived barriers increased, the acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccination decreased [21]. Therefore, reducing barriers can have a significant effect on the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccination. In addition to perceived barriers, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and behavioral intention were predictors of COVID-19 vaccination in the present study. Shmueli et al. found that perceived benefits, cues to action, and perceived severity were strong predictors of COVID-19 vaccination [25], and the result was relatively consistent with the present study.

The research result also indicated that the HBM constructs predicted 40% of behavioral intention variance. The finding is important because a few studies have investigated the roles of HBM constructs in accepting the COVID-19 vaccine. Hossain et al. found that HBM could predict 31% [21] which was less than the present study.

The present study had limitations that should be taken into consideration in generalizing the results. A limitation of the present study was the non-randomness of the participants who were included in the study from cyberspace and social networks. The second limitation was that some people in the province did not have access to smartphones, especially older people. The third limitation of the study was its cross-sectional type and the use of a self-report questionnaire that had inherent limitations.

Conclusion

About one-third (32.5%) of the participants had COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. The hesitancy was higher among people with low education levels. Interventions are necessary to increase compliance with vaccination, especially among people with education low levels. Based on HBM model constructs, perceived barriers had the inverse significant effect on receiving COVID-19 vaccines. Also, HBM constructs have a higher power of predicting hesitancy and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination; hence, this model can be used in intervention programs.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: Generalities of the research were approved by the Research Council of Golestan University of Medical Sciences and the National Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research with a code of IR.GOUMS.REC.1400.178.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Charkazi A (First Author), Main Researcher (20%); Allah Kalteh E (Second Author), Introduction Writer (10%); Yatimparvar Gh (Third Author), Methodologist (10%); Rahimzadeh H (Forth Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Koochaki Gh (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Shahini N (Sixth Author), Writer (10%); Ahmadi-Livani M (Seventh author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Rajabi A (Eighth Author), Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Full-Text: (534 Views)

Introduction

The COVID-19 epidemic is expected to impose enormous pressures on disease and mortality, and severely disrupt societies and economies worldwide. Governments should be prepared to distribute COVID-19 vaccines fairly, if available, and need to consider strategies to increase the vaccine trust and acceptance that also require the sufficient capacity of the health system. In 2015, the WHO Strategic Advisory Group defined vaccine hesitancy in immunization as a delay in accepting or refusing vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services that could vary in forms and severity depending on the time and place of occurrence. This varies depending on the type of vaccine and has been confirmed in several studies [1-3]. Concerns about vaccine hesitancy are growing worldwide [4]. WHO considers it one of the ten global health threats in 2019 [4, 5]. In many countries, hesitancy and misinformation about vaccines are major obstacles to achieving social coverage and immunity [6, 7]. Governments, public health officials, and advocacy groups need to be prepared to overcome insecurity and create vaccine literacy so that people can get immunized if necessary. Anti-vaccine activists are being promoted in several ways. Countries oppose the need for vaccines, and some of them deny the existence of COVID-19. Dissemination of misinformation via multiple channels can have a significant impact on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [8]. The rapid acceleration of vaccine production increases general anxiety and can jeopardize acceptance [9]. However, there is no general perception of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Numerous studies have indicated several factors associated with vaccine acceptance when a new vaccine is introduced [10-13], including the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, adverse health consequences, misconceptions about the need for the vaccine, lack of trust in the health system, and a lack of knowledge about vaccine-preventable diseases in society. Misinformation leading to vaccine fluctuation can endanger public health in response to the current crisis [13, 14]. It is also possible that people will not accept it based on whether it is new or not [15]. Understanding immunity can also affect vaccine acceptance [15]. Vaccination coverage may need to be high worldwide to prevent the COVID-19 epidemic. However, vaccine demand has been less studied in low- and middle-income countries, and there may be different demographic considerations compared to high-income countries [16]. These countries may have less capacity to introduce new vaccines and may need to deal with citizens who have hesitancy [17]. Several companies have started to produce vaccines in Iran, but they have not entered the market yet, but the Sputnik V vaccine of Russia, followed by Bharat of India, AstraZeneca, and Sinopharm entered Iran in February 2020, and the COVIran Barekat vaccine recently produced. Some people seem to be hesitant about them, and this hesitancy can have several reasons. Understanding why people are reluctant to get COVID-19 vaccination is necessary because it can help health authorities increase vaccine awareness and limit the spread of the disease [18].

Health Belief Model (HBM) is a general conceptual framework and a theoretical guideline for health behaviors used in public health research. This model was introduced by Becker and Maiman (1975) and includes the constructs, namely perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and preventive health behaviors [19]. This model has been used in many studies to prevent health behaviors. The public acceptance of the HBM and the popularity of its use are due to its predictive power [20].

Given that the public vaccination against COVID-19 has just started in Iran, and there are few studies on vaccination hesitancy using HBM models in Iran, and also the identification of personal and interpersonal factors in intervention planning can be very helpful, the present study was designed and conducted to determine COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy based on the HBM.

Instrument & Methods

The study conducted a cross-sectional research design. Data were collected using an online-based questionnaire, which was conducted from 10 September 2021 to 15 October 2021, and targeted residents in the Golestan province of Northeast Iran, aged 16 years and above on social media platforms (i.e., WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram). According to the report of “Digital 2018” (Kemp, 2018), Instagram and Telegram are the most popular social media in Iran. This web-based questionnaire was completely voluntary and non-commercial. So, the participants were selected using convenience sampling and they completed the electronic questionnaire. The sample size in this study was estimated to be at least 626 people according to the parameters presented for the prevalence of vaccination hesitancy in a study [21]. The generalities of the research were approved by the Research Council of Golestan University of Medical Sciences and the National Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research.

The key outcome variables were COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. We used two 6-point Likert items to measure COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the respondents: (a) If you get the chance of getting a COVID-19 vaccine for free, what will you do? (With the response of 1= Surely, I will take it; 2= Probably I will take it; 3= I will delay taking it; 4= I am not sure what I will do; 5= Probably I will not take it; 6= Surely, I will not take it), and (b) If your family or friends think of getting COVID-19 vaccine, what will you do? (With the response of 1= Strongly encourage them; 2=Encourage them; 3=Ask them to delay getting the vaccine; 4=I will not say anything about it; 5=Discourage them to take vaccine; 6= Forbid them to take vaccine). We combined these two items and calculated the level of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, where a higher score indicated a higher level of hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine [21]. The theoretical total score ranges from 2 to 12. For the multinomial regressions predicting vaccine hesitancy, responses were recoded into three groups: 1) Likely to take (combining surely and probably I will take it); 2) unsure (combining I will delay taking it and I am not sure what I will do); and, 3) Likely not take (combining probably I will not take it and surely, I will not take it).

The HBM constructs consisted of the following components: perceived susceptibility (included two items, α=0.67), perceived severity (included four items, α=0.567), perceived benefits (included seven items, α=0.834), perceived barriers (included five items, α=0.83), and intention to treat. These items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree) [21]. The content validity of the questionnaire was approved by health education and promotion specialists and the necessary changes and corrections were applied in the text of the questionnaire based on their opinions. Also, the reliability of these tools was evaluated by alpha Cronbach. We also collected data on the following independent variables: age, sex, educational level, place of residence, occupation, and history of infected COVID-19 in itself and family members.

A descriptive analysis was conducted to explain the demographic profile of the survey respondents and the hesitancy and construct of HBM. We explore differences in vaccine hesitancy across a range of sociodemographic characteristics, (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, education), and also other variables. Then, a multiple linear regression analysis was employed to determine how the independent variables (namely, the HBM constructs of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers) would associate with the outcome variable of intention to take to COVID-19 vaccine. Multinomial logistic regressions were used to assess competing risks between being unlikely, unsure, or likely to get the vaccine. All covariates were included in the multivariate models. All the statistical tests are two-sided, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Stata software program, version 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Findings

In the present study, 599 out of 626 questionnaires were completed for data collection (95% response rate). The mean age of the samples was 33.63±10.71, most of whom (25.5%) were in the age group of 31 to 39 years. 57.30% of the samples were females. More than 66% of them had an associate's/ bachelor's degree or higher. Furthermore, about three-quarters (74.30%) of the samples were living in urban regions, and 46.58% of them had no history of the virus. Table 1 presents other characteristics of the samples.

The COVID-19 epidemic is expected to impose enormous pressures on disease and mortality, and severely disrupt societies and economies worldwide. Governments should be prepared to distribute COVID-19 vaccines fairly, if available, and need to consider strategies to increase the vaccine trust and acceptance that also require the sufficient capacity of the health system. In 2015, the WHO Strategic Advisory Group defined vaccine hesitancy in immunization as a delay in accepting or refusing vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services that could vary in forms and severity depending on the time and place of occurrence. This varies depending on the type of vaccine and has been confirmed in several studies [1-3]. Concerns about vaccine hesitancy are growing worldwide [4]. WHO considers it one of the ten global health threats in 2019 [4, 5]. In many countries, hesitancy and misinformation about vaccines are major obstacles to achieving social coverage and immunity [6, 7]. Governments, public health officials, and advocacy groups need to be prepared to overcome insecurity and create vaccine literacy so that people can get immunized if necessary. Anti-vaccine activists are being promoted in several ways. Countries oppose the need for vaccines, and some of them deny the existence of COVID-19. Dissemination of misinformation via multiple channels can have a significant impact on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [8]. The rapid acceleration of vaccine production increases general anxiety and can jeopardize acceptance [9]. However, there is no general perception of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Numerous studies have indicated several factors associated with vaccine acceptance when a new vaccine is introduced [10-13], including the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, adverse health consequences, misconceptions about the need for the vaccine, lack of trust in the health system, and a lack of knowledge about vaccine-preventable diseases in society. Misinformation leading to vaccine fluctuation can endanger public health in response to the current crisis [13, 14]. It is also possible that people will not accept it based on whether it is new or not [15]. Understanding immunity can also affect vaccine acceptance [15]. Vaccination coverage may need to be high worldwide to prevent the COVID-19 epidemic. However, vaccine demand has been less studied in low- and middle-income countries, and there may be different demographic considerations compared to high-income countries [16]. These countries may have less capacity to introduce new vaccines and may need to deal with citizens who have hesitancy [17]. Several companies have started to produce vaccines in Iran, but they have not entered the market yet, but the Sputnik V vaccine of Russia, followed by Bharat of India, AstraZeneca, and Sinopharm entered Iran in February 2020, and the COVIran Barekat vaccine recently produced. Some people seem to be hesitant about them, and this hesitancy can have several reasons. Understanding why people are reluctant to get COVID-19 vaccination is necessary because it can help health authorities increase vaccine awareness and limit the spread of the disease [18].

Health Belief Model (HBM) is a general conceptual framework and a theoretical guideline for health behaviors used in public health research. This model was introduced by Becker and Maiman (1975) and includes the constructs, namely perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and preventive health behaviors [19]. This model has been used in many studies to prevent health behaviors. The public acceptance of the HBM and the popularity of its use are due to its predictive power [20].

Given that the public vaccination against COVID-19 has just started in Iran, and there are few studies on vaccination hesitancy using HBM models in Iran, and also the identification of personal and interpersonal factors in intervention planning can be very helpful, the present study was designed and conducted to determine COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy based on the HBM.

Instrument & Methods

The study conducted a cross-sectional research design. Data were collected using an online-based questionnaire, which was conducted from 10 September 2021 to 15 October 2021, and targeted residents in the Golestan province of Northeast Iran, aged 16 years and above on social media platforms (i.e., WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram). According to the report of “Digital 2018” (Kemp, 2018), Instagram and Telegram are the most popular social media in Iran. This web-based questionnaire was completely voluntary and non-commercial. So, the participants were selected using convenience sampling and they completed the electronic questionnaire. The sample size in this study was estimated to be at least 626 people according to the parameters presented for the prevalence of vaccination hesitancy in a study [21]. The generalities of the research were approved by the Research Council of Golestan University of Medical Sciences and the National Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research.

The key outcome variables were COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. We used two 6-point Likert items to measure COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the respondents: (a) If you get the chance of getting a COVID-19 vaccine for free, what will you do? (With the response of 1= Surely, I will take it; 2= Probably I will take it; 3= I will delay taking it; 4= I am not sure what I will do; 5= Probably I will not take it; 6= Surely, I will not take it), and (b) If your family or friends think of getting COVID-19 vaccine, what will you do? (With the response of 1= Strongly encourage them; 2=Encourage them; 3=Ask them to delay getting the vaccine; 4=I will not say anything about it; 5=Discourage them to take vaccine; 6= Forbid them to take vaccine). We combined these two items and calculated the level of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, where a higher score indicated a higher level of hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine [21]. The theoretical total score ranges from 2 to 12. For the multinomial regressions predicting vaccine hesitancy, responses were recoded into three groups: 1) Likely to take (combining surely and probably I will take it); 2) unsure (combining I will delay taking it and I am not sure what I will do); and, 3) Likely not take (combining probably I will not take it and surely, I will not take it).

The HBM constructs consisted of the following components: perceived susceptibility (included two items, α=0.67), perceived severity (included four items, α=0.567), perceived benefits (included seven items, α=0.834), perceived barriers (included five items, α=0.83), and intention to treat. These items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree) [21]. The content validity of the questionnaire was approved by health education and promotion specialists and the necessary changes and corrections were applied in the text of the questionnaire based on their opinions. Also, the reliability of these tools was evaluated by alpha Cronbach. We also collected data on the following independent variables: age, sex, educational level, place of residence, occupation, and history of infected COVID-19 in itself and family members.

A descriptive analysis was conducted to explain the demographic profile of the survey respondents and the hesitancy and construct of HBM. We explore differences in vaccine hesitancy across a range of sociodemographic characteristics, (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, education), and also other variables. Then, a multiple linear regression analysis was employed to determine how the independent variables (namely, the HBM constructs of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers) would associate with the outcome variable of intention to take to COVID-19 vaccine. Multinomial logistic regressions were used to assess competing risks between being unlikely, unsure, or likely to get the vaccine. All covariates were included in the multivariate models. All the statistical tests are two-sided, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Stata software program, version 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Findings

In the present study, 599 out of 626 questionnaires were completed for data collection (95% response rate). The mean age of the samples was 33.63±10.71, most of whom (25.5%) were in the age group of 31 to 39 years. 57.30% of the samples were females. More than 66% of them had an associate's/ bachelor's degree or higher. Furthermore, about three-quarters (74.30%) of the samples were living in urban regions, and 46.58% of them had no history of the virus. Table 1 presents other characteristics of the samples.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics and Likelihood of getting the COVID-19 vaccine of respondents (N=599)

Figure 1) Prevalence (%) of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in respondents

Furthermore, 70.6% of the samples stated that they would definitely (65.4%) or possibly (5.2%) use the vaccine for free once it became available. 3.7% out of 9.2% of those who were unlikely to receive the vaccine said that they would definitely not use the vaccine, and 5.5% said that they would probably not use it. 8.5% and 11.7% said respectively that they were unsure about the use of the vaccine and would delay its use (Figure 1-A). Moreover, 78.5% of the total sample said that they encouraged their families or relatives to get COVID-19 vaccination, while only 1.5% of the samples prevented the vaccination of their relatives (Figure 1-B).

The mean of the hesitancy scale was equal to 3.93±2.53 based on the two questions. Based on these two questions (3.93/12*100), 32.75% of the samples had hesitancy about the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. Table 2 summarizes the results of the HBM.

Table 2) Scores obtained for model constructs (n=599)

According to the relationship between different factors on the vaccination intention based on HBM, there was a kegative significant relationship between vaccination hesitancy and the existing barriers to vaccination intention. Based on the model, controlling the effects of demographic variables in our model indicated that the HBM constructs could predict 40% of the behavioral intention variance (Adj R-squared=0.40). So, the strongest predictors were vaccination hesitancy and the existing barriers (Table 3).

The relationship between HBM constructs with the probability of using the COVID-19 vaccine by polynomial logistic regression indicated that the perceived barriers were significantly related between the probability of using the vaccine and the probability of not using the vaccine, thereby reducing the probability of using the vaccine by 10%. (RRR=0.90, 95% CI: 0.82-0.99). Furthermore, perceived benefits (RRR=1.21, 95% CI: 1.11-1.32), perceived susceptibility (RRR= 1.54, 95% Cl: 1.23-1.92), and behavioral intention (RRR=3.06, 95% CI: 2.23-4.20) also had significant relationships with the probability of using the vaccine. The factors were associated with an increased probability of using the vaccine. They also existed in comparing the probability of using the vaccine with the

probability of not being sure about receiving the vaccine (Table 4).

Table 3) Results of the regression analysis of the dependent variable: intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine

Table 4) Multinomial regressions predicting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (n=599)

Discussion

Given the current status of society in Iran, which is currently involved with the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination has been carried out among the general public to overcome this pandemic. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and its relevant factors. The research results indicated that the rate of hesitancy in the injection of the COVID-19 vaccine in the research population was equal to 32.57%. In other words, about one-third of the participants had hesitancy about the vaccine injection. The results of a study by Hossain et al. indicated that the prevalence of vaccination hesitancy was 41.1% in Bangladesh, which was slightly higher than the present study [21]. This rate was 28.5% in a study by Lazarus et al. in 19 countries, and it was slightly less than the present study [22]. The results of a study in Saudi Arabia also indicated that 33.3% of people were reluctant to receive the vaccine [23]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the rate of non-acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine has been high in most studies. The present study shows the existence of obstacles to vaccination; among them, the ease of access and consultation of specialists, as well as the level of education, are related to hesitancy about the vaccination of Covid-19. In addition, literature review, this hesitancy and lack of vaccination can have several reasons such as the novelty of the vaccines, the lack of trust in them, and the fear of side effects of the vaccine. The results of a qualitative study on women released from prison in the United States indicated that the most important reasons for not receiving the anti-coronavirus vaccine were the lack of trust, the novelty of the vaccine, fear of its long-term effects, belief in the existence of electronic microchips in COVID-19 vaccines, their strong immune systems, no need for vaccines, and belief in diseases induced by COVID-19 vaccines [24]. The vaccine hesitancy was much lower in some studies than in the present study. For instance, the hesitancy rate was 20% in a study by Shmueli [25], 25% in a study by Dror et al. [26], and 31% in a study by Reiter et al. [27]. The first point to note about the differences in the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in different studies is the time to conduct or review the studies as recent studies have shown less hesitancy than earlier studies. As time goes by, public knowledge increases due to the exposure to information, and thus vaccination hesitancy decreases. The second point for these differences is whether vaccine hesitancy is assessed during the peak of COVID-19 in that society or during the control or steady status of the prevalence of COVID-19.

The results of the present study also indicated that if the COVID-19 vaccine was available for free, about 70% of the population would probably or definitely use it. Furthermore, 78.5% of the participants admitted that they would encourage family members or relatives to use the COVID-19 vaccine. A study by Prickett et al. in New Zealand also indicated that 71% of the population would probably use the COVID-19 vaccine if it became available [28], and their result was consistent with our study, indicating that there was not a significant difference in vaccine acceptance in different countries.

The results of this study also indicated that as the education level increased, vaccination hesitancy decreased. In other words, the higher education level significantly increased the rate of acceptance and adherence to vaccination. The finding was consistent with other studies [25, 29, 30]. A higher education level can increase health literacy and affect the individuals' health motivation. In the present study, the participants admitted that they would probably or not inject the vaccine if it was available for free, and the rate was higher in men (11.3%) than women (7.3%). However, a study by Sallam et al. [31] in Kuwait and Jordan showed that women were more likely than men not to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, the probability decreased with age, and it was consistent with other studies. The study of the probabilities in job groups also indicated that the highest level of hesitancy was seen among workers (30.3%). The finding is justifiable since most workers had lower education levels, indicating that hesitancy was higher in lower education.

Regarding the HBM constructs, the results indicated that there was a significant and inverse relationship between perceived barriers and intention to vaccinate so increasing perceived barriers to COVID-19 vaccination significantly reduced the vaccination intention. The results of a study in Bangladesh also indicated that as the perceived barriers increased, the acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccination decreased [21]. Therefore, reducing barriers can have a significant effect on the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccination. In addition to perceived barriers, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and behavioral intention were predictors of COVID-19 vaccination in the present study. Shmueli et al. found that perceived benefits, cues to action, and perceived severity were strong predictors of COVID-19 vaccination [25], and the result was relatively consistent with the present study.

The research result also indicated that the HBM constructs predicted 40% of behavioral intention variance. The finding is important because a few studies have investigated the roles of HBM constructs in accepting the COVID-19 vaccine. Hossain et al. found that HBM could predict 31% [21] which was less than the present study.

The present study had limitations that should be taken into consideration in generalizing the results. A limitation of the present study was the non-randomness of the participants who were included in the study from cyberspace and social networks. The second limitation was that some people in the province did not have access to smartphones, especially older people. The third limitation of the study was its cross-sectional type and the use of a self-report questionnaire that had inherent limitations.

Conclusion

About one-third (32.5%) of the participants had COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. The hesitancy was higher among people with low education levels. Interventions are necessary to increase compliance with vaccination, especially among people with education low levels. Based on HBM model constructs, perceived barriers had the inverse significant effect on receiving COVID-19 vaccines. Also, HBM constructs have a higher power of predicting hesitancy and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination; hence, this model can be used in intervention programs.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: Generalities of the research were approved by the Research Council of Golestan University of Medical Sciences and the National Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research with a code of IR.GOUMS.REC.1400.178.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Charkazi A (First Author), Main Researcher (20%); Allah Kalteh E (Second Author), Introduction Writer (10%); Yatimparvar Gh (Third Author), Methodologist (10%); Rahimzadeh H (Forth Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Koochaki Gh (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Shahini N (Sixth Author), Writer (10%); Ahmadi-Livani M (Seventh author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Rajabi A (Eighth Author), Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2022/04/5 | Accepted: 2022/07/24 | Published: 2022/09/18

Received: 2022/04/5 | Accepted: 2022/07/24 | Published: 2022/09/18

References

1. MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036]

2. Karafillakis E, Larson HJ, ADVANCE consortium. The benefit of the doubt or doubts over benefits? A systematic literature review of perceived risks of vaccines in European populations. Vaccine. 2017;35(37):4840-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.061]

3. Muñoz DC, Llamas LM, Bosch-Capblanch X. Exposing concerns about vaccination in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(7):767-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00038-015-0715-6]

4. European Parliament. European parliament resolution of 19 April 2018 on vaccine hesitancy and drop in vaccination rates in Europe (2017/2951 RSP). Strasbourg: European Parliament; 2018. [Link]

5. Akbar R. Ten threats to global health in 2019 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 [Cited 2022 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. [Link]

6. Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form data-2015-2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3861-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063]

7. Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081]

8. Enserink M, Cohen J. Fact-checking Judy Mikovits, the controversial virologist attacking Anthony Fauci in a viral conspiracy video [Internet]. Science; 2020 [Cited 2022 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/fact-checking-judy-mikovits-controversial-virologist-attacking-anthony-fauci-viral [Link] [DOI:10.1126/science.abc7103]

9. Cornwall W. Officials gird for a war on vaccine misinformation. Science. 2020;369(6499):14-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1126/science.369.6499.14]

10. Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring trust in vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1599-609. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252]

11. Xiao X, Wong RM. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(33):5131-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.076]

12. Gidengil CA, Parker AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Trends in risk perceptions and vaccination intentions: a longitudinal study of the first year of the H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):672-9. [Link] [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300407]

13. Setbon M, Raude J. Factors in vaccination intention against the pandemic influenza A/H1N1. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(5):490-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckq054]

14. Halpin C, Reid B. Attitudes and beliefs of healthcare workers about influenza vaccination. Nurs Older People. 2019 March. [Link] [DOI:10.7748/nop.2019.e1154]

15. Sun X, Wagner AL, Ji J, Huang Z, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Boulton ML, et al. A conjoint analysis of stated vaccine preferences in Shanghai, China. Vaccine. 2020;38(6):1520-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.062]

16. Wagner AL, Boulton ML, Sun X, Mukherjee B, Huang Z, Harmsen IA, et al. Perceptions of measles, pneumonia, and meningitis vaccines among caregivers in Shanghai, China, and the health belief model: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:143. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12887-017-0900-2]

17. Nichter M. Vaccinations in the third world: a consideration of community demand. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(5):617-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00034-5]

18. Yufika A, Wagner AL, Nawawi Y, Wahyuniati N, Anwar S, Yusri F, et al. Parents' hesitancy towards vaccination in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Vaccine. 2020;38(11):2592-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.072]

19. Hillers VN, Medeiros L, Kendall P, Chen G, DiMASCOLA S. Consumer food-handling behaviors associated with prevention of 13 foodborne illnesses. J Food Prot. 2003;66(10):1893-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-66.10.1893]

20. Strecher VJ, Rosenstock IM. The health belief model. In: Samuel A, Sheeran P. Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine. Unknown city: Curtin Research Publications; 1997. [Link]

21. Hossain MB, Alam MZ, Islam MS, Sultan S, Faysal MM, Rima S, et al. Health Belief, Planned Behavior, or Psychological Antecedents: What predicts COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy better among the Bangladeshi Adults? medRxiv. 2021. [Link] [DOI:10.1101/2021.04.19.21255578]

22. Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9]

23. Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1657-63. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S276771]

24. Geana MV, Anderson S, Ramaswamy M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among women leaving jails: a qualitative study. Public Health Nurs. 2021;38(5):892-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/phn.12922]

25. Shmueli L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:804. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10816-7]

26. Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y]

27. Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated?. Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043]

28. Prickett KC, Habibi H, Carr PA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in a cohort of diverse New Zealanders. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;14:100241. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100241]

29. Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(4):e210-e21. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8]

30. Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;1:100012. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012]

31. Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, et al. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: a study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):42. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/vaccines9010042]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |