Volume 10, Issue 4 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(4): 643-648 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mehri A, Soltani H, Hosseini Z, Joveini H, Shahrabadi R, Hashemian M. The Role of Education Based on the Perception/Tendency Model on the Use of Energy Supplements in Bodybuilding Athletes: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (4) :643-648

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60530-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60530-en.html

1- Department of Health Education, School of Health, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, Neyshabur, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, Neyshabur, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 1387 kb]

(1019 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2759 Views)

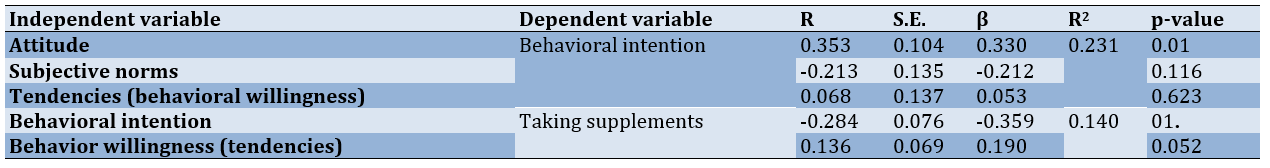

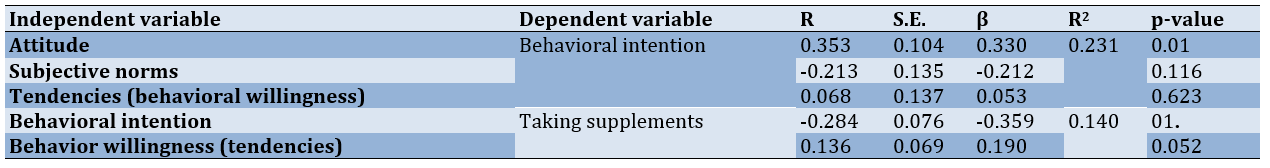

Table 2) The effect of imagery model construct and tendencies on behavioral intention based on linear regression model in the target group before intervention

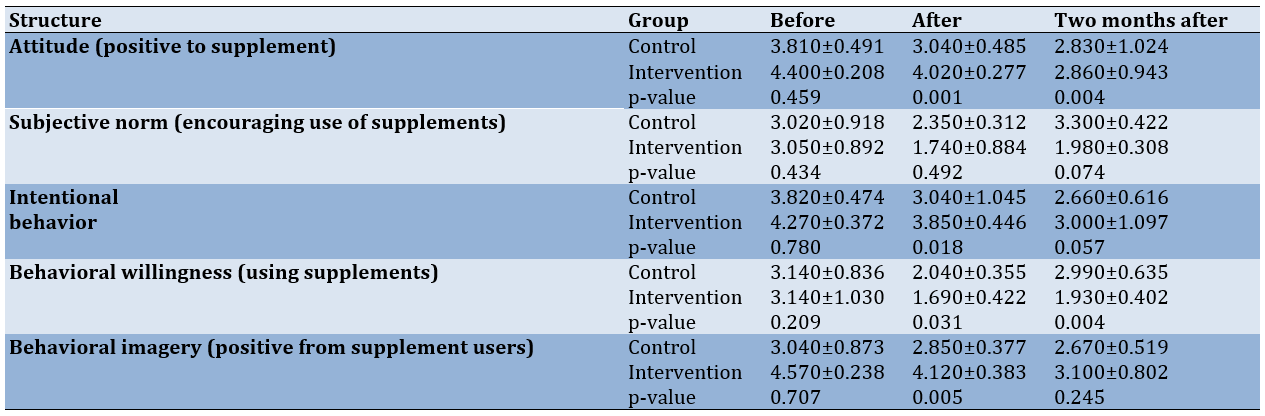

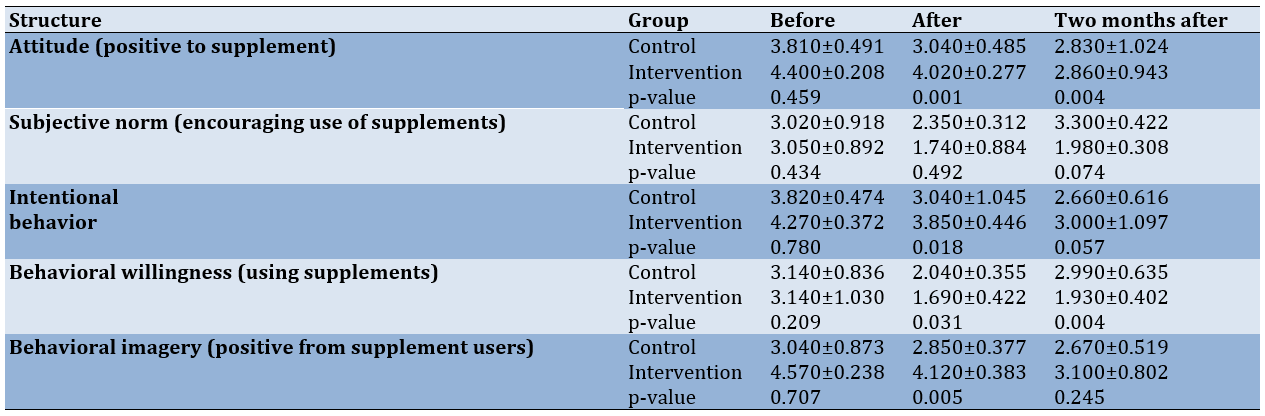

Table 3) Mean±SD results of attitude model constructs in two groups before, after, and two months after the intervention (p<0.001)

Discussion

In this study, 35% of athletes used energy Supplements. Karimian and Saeedi reported 49% and 66% of supplement use, respectively [15, 16]. Though consumption in the present study was lower than in the other studies, more than one-third of athletes in the current study used energy supplements, which is significant and alarming. Due to the side effects of supplement intake [16-19]. Therefore, it is recommended to intervene to raise awareness of the side effects of supplements and design a specific regulatory protocol for the city's bodybuilding clubs with the help of relevant agencies.

We found the attitude score was almost average in the study population, indicating 46. 5% of the participants had a positive attitude toward energy supplements and were at risk of healthy supplement usage. Abedini showed that the more people's attitudes toward supplement use, the more they will use supplements [27]. Mood was the most critical predictor of dietary supplement intake, and a significant positive correlation was observed between attitude and behavior. These findings agree with the studies [28-30] that providing a healthy diet plan to replace energy supplements could significantly impact supplement intake. Since the results showed that attitudes are more common in married people and those living single, these factors can influence designing effective intervention programs. There was a score reduction in the mean attitude construct in the experimental group compared to the control group 2 months after the intervention. These changes may indicate the effectiveness of a training program to raise awareness and reduce athletes' positive attitudes toward nutritional supplements. This is consistent with Mohammad Hassan Saati et al. [31], which showed a reduction of 1.16 score to a positive attitude toward the use of nutritional supplements after the educational intervention, from 18. 51 to 17.35.

The subjective norms obtained in the study population were moderate, and 66% of their relatives had a history of complement use. Subjective norms are the pressure a person feels on the part of people who are important to them to do or not to behave [32]. Therefore, educational planning for peers in this group played a significant role. These results are in agreement with the data of the study [31], which showed a statistically significant difference between the use of complement (anabolic steroids) and subjective norm construct (p=0.040). A negative correlation between the mean of the subjective norms with the behavior was found, while the subjective norms after attitude were the second predictor of intention to supplement intake. These results correspond with Mehri and Bashirian, indicating that subjective norms were the most important predictors [33, 34]. It can be argued that, as much as possible, through educational interventions, the average subjective norms and pressure felt by individuals’ important persons be reduced, and the intake of the supplement will be reduced. The present study results showed that the mean score of "subjective norms" decreased two months after the educational intervention in the experimental group.

They knew that the study groups are young and the peers’ role in accepting one behavior is essential. The part of education and transfer of educational experiences through influential individuals is practical. This result indicates the effect of a training program on participants. These results are consistent with Saati et al. [31] on the program's effect on the prevention and reduction of anabolic steroid consumption and the findings of Heidarnia et al. on the impact of the program's educational intervention on smoking prevention [35].

Behavioral willingness was also one of the predictors of the behavioral intention of supplement intake. These results are in line with the data given by studies [36, 37]. The percentage of behavioral willingness obtained score was moderate in the study subjects. In designing training programs to promote healthy behaviors, people should be trained to increase their ability to recognize high-risk behaviors and resist peer pressure. Participants should learn to express opposition and address social anxiety in situations where it is not necessary to say so. Resolve their conflicts constructively and achieve a better ability to control arousal and social communication. The present study results showed a decrease in the mean of "behavioral willingness” in the experimental group compared to the control group 2 months after the intervention. These changes may indicate that the training program effectively reduces athletes' willingness for supplement use. The less willing the risky behavior declines, which is consistent with studies [31, 35]. In the study of Saati, the educational intervention reduced the mean score of willingness for consuming nutritional supplements by 0.62 (from 9.38 to 8. 76 after the intervention) [31]. In the study of Hydernia et al., the mean score of behavioral willingness after the intervention was reduced.

The percentages of behavioral imagery were above average. Behavioral imagery is a person's mental perception of their peers involved in a particular high-risk behavior [22]. These results are consistent with the data of Zahra Serlak et al., showing that adolescents have clear social images of their peers who are engaged in high-risk behaviors [38]. The present study results showed a decrease in the mean Behavioral Imagery constructs in the experimental group compared to the control group 2 months after the intervention. . It is important to note that people's perception of behavior plays a vital role in their choice of conduct. Therefore, educational intervention should reduce one's perceptions of negative behaviors. The findings of this study agree with the conclusions from Heidarnia et al. In the survey of Heidarnia, the results showed a decrease in the mean behavioral imagery after educational intervention [35]. More than half of the population surveyed intended to use energy supplements in the future, indicating the need for educational planning on dietary supplements and alternative energy supplements. Since behavioral intentions were predictors of supplement intake, educational interventions aimed at energy supplement intake could lead to reduced supplement consumption. The scores of behavioral intention construct in the experimental group decreased two months after the intervention. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the current educational program in reducing athletes' behavioral intention in supplement use. in the study Saati, after the intervention, the use of anabolic steroids was reduced [31]. These data correspond with Jaliyan et al. reporting a significant reduction in using the supplement in the experimental group after the educational intervention program [39]. Many issues must be considered while interpreting the results of this study: first, the majority of the participants had a high level of education (academic degree). Therefore, the results may not generalize to other populations. We used a regional sample from Sabzevar City that may not represent the whole population in Iran. And finally, since self-report was used to collect data, the social desirability concerns of the participants may have affected their responses. Another limitation of the current study was the cross-sectional design.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the study educational interventions in the study population are necessary. Applying this model to the predictive dimension showed that the path of rational behavior has more predictive power than the social response path and in the formation of behavioral intentions. Subjective norms can be one of the most critical factors driving the consumption of supplements. The attitude/tendency model can be used for educational interventions. The results also indicated the effectiveness of the present intervention in reducing the use of energy Supplements. Therefore, educational interventions based on the model of attitude/tendency model to reduce the consumption of energy Supplements are recommended.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank all the participants for their sincere cooperation in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This article is retrieved from the research project approved by Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences with the Ethics committee reference number IR.MEDSAB.REC.1397.006.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared

Authors’ Contributions: Mehri A (First Author), Introduction Writer /Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Soltani H (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (20%); Hosseini ZS (Third Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (10%); Hashemian M (Forth Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (15%); Joveini H (Fifth author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (10%); Shahrabadi R (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/ Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: the Vice-Chancellor supported for Research and Technology of this university.

Full-Text: (99 Views)

Introduction

When human beings have been paid to sports, nutrition has been considered a necessity. Food has a unique basis in the daily sports program. With advanced knowledge of metabolism and sports physiology, knowing the role of nutritive has led to the production of nutritional supplements [1-3].

Dietary supplements, also known as sports supplements, are substances used by athletes to lessen nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iron deficiency) or to increase athletic performance (e.g., creatine). Dietary supplements are beneficial for athletes engaged in intensive activity while meeting the nutritional needs of ordinary athletes could be made with proper nutrition [4, 5]. Factors, such as press pressure to compete and win, popular attitudes about doping being successful, people's unrealistic expectations of national competitions, coaches' emphasis and pressure, lack of consumption control, competitive athlete personality, psychological belief that they need to increase performance with a magic pill, attracting spectators of sports competitions and heavy schedules of an athlete have all led to an unprecedented increase in the prevalence of inappropriate supplement use among athletes [6-8]. The growing tendency of athletes to take supplements has dramatically enriched the industry of supplement sales [9]. Studies indicate that in developed countries, supplement usage is increasing in the athlete community. For example, in the studies, 48%, 38%, and 45% of athletes consumed nutritional supplements, respectively [9-12]. In Iran, the consumption of dietary supplements is also

high. For example, the prevalence of dietary supplements in the studies was 48%, 38%, and 45%, respectively [13-15].

Supplement use in athletes can cause various side effects, such as behavioral and personality disorders, violent behaviors, and diseases, such as myocardial infarction, breast enlargement, hepatotoxicity, suppression of endocrine nerve function, etc. Also, a predisposing factor for drug and alcohol dependence. Excessive consumption of various dietary supplements can also cause side effects, such as gout, dehydration, and osteoporosis [16-20]. The most effective way to prevent banned drug abuse is through community education. Some theories can guide health education and health promotion activities and answer planners’ questions about Why people do not behave properly? How to change behaviors? and What factors should be considered in evaluating programs?

Despite the strong emphasis on theories, such as rational action and planned behavior on the role of rational decision-making, to predict one’s behaviors, many researchers have proposed criticisms on approaches against risky behaviors, like substance abuse, that, decision making in these regards is likely to happen spontaneously [21]. Gibbons et al., to intervene in arbitrary decisions, especially about risky behaviors, introduced a new concept of behavioral willingness as part of the prototype willingness model. According to this model, social images Prototype will lead a person to high-risk behaviors if there is a tendency and the condition suits. This model includes attitude, subjective norms, behavioral willingness, imagery, and intention [22-24].

Since health education is essential as a preventive behavior intervention, especially on substance abuse [25, 26], this study aimed to determine the impact of prototype willingness model-based training on energy supplement use in the athletes in Sabzevar.

Materials and Methods

This randomized clinical trial study was conducted on male athletes in gym clubs in Sabzevar. The sample size was calculated by considering the expected difference of 20% at pre-and post-intervention and considering the accuracy of 90% and 95% confidence interval in the following formula:

The sample size was estimated to be 50 in each group considering P1=0.34, P2=0.61, power=0.8, and α=0.05, which was estimated to be 60 in the case of the missing sample. Inclusion criteria were: at least 15 years old and a maximum of 50 years, 2-being a member of one of the men's gym clubs in Sabzevar, exercising at least three times per week. The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to participate in the study and absence from training sessions. Sampling was performed in the clustering method. The bodybuilding clubs whose managers had given their consent and provided the necessary support for the research were selected as the research environment. Two clubs were chosen randomly.

The data collection tools were questionnaires that consisted of two sections: demographic questions and questions that assessed the theory of conservation motivation. The questions such as Supplements help me to have more muscle in less time(Attitude). It's essential for me to my friends’ ideas on my supplement use(Subjective norm). If I have access to supplements, I will use them(Behavioral intention). If they offer me energy supplements, I thank them and answer "no." (Behavioral willingness). In my opinion, anyone who uses supplements is attractive (behavioral imagery). The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed through the expert’s panel and its reliability through Cronbach’s alpha (N=30, α=0.64-0.91).

To comply with ethical considerations, this study was approved by the ethics committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. Written consent was obtained from the participants, and they were ensured that their information would be kept confidential by the researchers. Based on the results that were the educational needs assessment, the academic curriculum and educational content were adjusted. Then, one club was randomly assigned as the intervention group and the second one as the control group. The experimental group received the educational intervention, and the control group received routine training. According to the predictors of supplement usage based on prototype willingness model constructs, the training program lasted six weeks and one training session per week. The training program included questions and answers, brainstorming and group discussion, and educational aids, such as booklets, posters, and short films. There was also a cyberspace group called “No Nutrition Supplements Campaign”. The educational content is tailored to the training classes’ side effects of athletes' nutritional supplements and healthy eating. It was uploaded and converted into the group. It was also asked to invite their friends to influence the subjective norms. Most of the participants had smartphones and also used cyberspace. In the first session, while gaining the satisfaction of the participants in the class, the mobile numbers of the participants in the class were collected; in the social network, a group called Campaign No to Energize supplements was formed in which the educational contents appropriate to the training classes, the side effects of consuming energizing supplements as well as the healthy diet of athletes, and the skills of daring and saying no skills were uploaded in groups and also conversationally in groups. It was necessary to influence the abstract norms; they were also asked to invite their friends to this group. A gift (NO DOPING T-shirt with printed logo) intended by the researcher for the best people in terms of more attendance in classes and more participation in group discussions to increase the motivation of athletes participating in the study is placed. The post-test was done by redistributing the questionnaire one and two months after the educational intervention in both groups.

Descriptive and analytical tests were used for data analysis using SPSS 21 software.

Findings

The study population consisted of 112 bodybuilder athletes in Sabzevar, 95.4% of them were high secondary school and academic level education, 28% businessman, and mean BMI=24.94. About 35% of them and 66% of their families had a history of supplement usage.

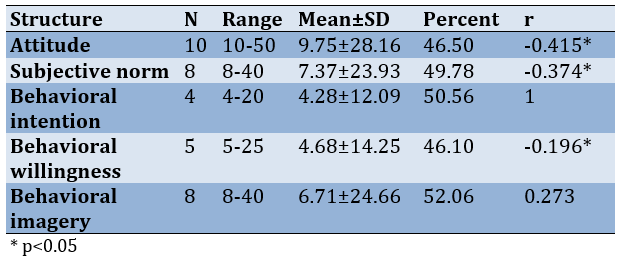

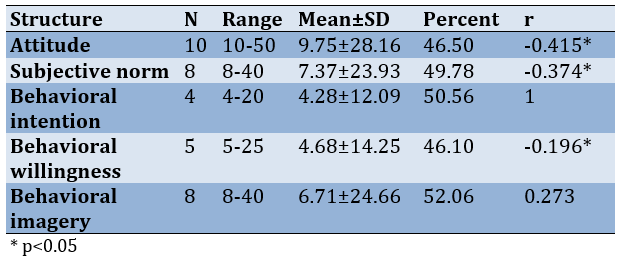

According to the results, the rates of the obtained model structures were moderate; among them, the percentage of the obtained score of behavioral attitude and behavioral willingness constructs had the highest and lowest rate of the score, respectively. There was a significant negative correlation between attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral readiness constructs with behavioral intention (p<0.05). At the same time, there was a positive correlation between behavioral imagery and behavioral intention (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of questions and correlation with behavioral intention

When human beings have been paid to sports, nutrition has been considered a necessity. Food has a unique basis in the daily sports program. With advanced knowledge of metabolism and sports physiology, knowing the role of nutritive has led to the production of nutritional supplements [1-3].

Dietary supplements, also known as sports supplements, are substances used by athletes to lessen nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iron deficiency) or to increase athletic performance (e.g., creatine). Dietary supplements are beneficial for athletes engaged in intensive activity while meeting the nutritional needs of ordinary athletes could be made with proper nutrition [4, 5]. Factors, such as press pressure to compete and win, popular attitudes about doping being successful, people's unrealistic expectations of national competitions, coaches' emphasis and pressure, lack of consumption control, competitive athlete personality, psychological belief that they need to increase performance with a magic pill, attracting spectators of sports competitions and heavy schedules of an athlete have all led to an unprecedented increase in the prevalence of inappropriate supplement use among athletes [6-8]. The growing tendency of athletes to take supplements has dramatically enriched the industry of supplement sales [9]. Studies indicate that in developed countries, supplement usage is increasing in the athlete community. For example, in the studies, 48%, 38%, and 45% of athletes consumed nutritional supplements, respectively [9-12]. In Iran, the consumption of dietary supplements is also

high. For example, the prevalence of dietary supplements in the studies was 48%, 38%, and 45%, respectively [13-15].

Supplement use in athletes can cause various side effects, such as behavioral and personality disorders, violent behaviors, and diseases, such as myocardial infarction, breast enlargement, hepatotoxicity, suppression of endocrine nerve function, etc. Also, a predisposing factor for drug and alcohol dependence. Excessive consumption of various dietary supplements can also cause side effects, such as gout, dehydration, and osteoporosis [16-20]. The most effective way to prevent banned drug abuse is through community education. Some theories can guide health education and health promotion activities and answer planners’ questions about Why people do not behave properly? How to change behaviors? and What factors should be considered in evaluating programs?

Despite the strong emphasis on theories, such as rational action and planned behavior on the role of rational decision-making, to predict one’s behaviors, many researchers have proposed criticisms on approaches against risky behaviors, like substance abuse, that, decision making in these regards is likely to happen spontaneously [21]. Gibbons et al., to intervene in arbitrary decisions, especially about risky behaviors, introduced a new concept of behavioral willingness as part of the prototype willingness model. According to this model, social images Prototype will lead a person to high-risk behaviors if there is a tendency and the condition suits. This model includes attitude, subjective norms, behavioral willingness, imagery, and intention [22-24].

Since health education is essential as a preventive behavior intervention, especially on substance abuse [25, 26], this study aimed to determine the impact of prototype willingness model-based training on energy supplement use in the athletes in Sabzevar.

Materials and Methods

This randomized clinical trial study was conducted on male athletes in gym clubs in Sabzevar. The sample size was calculated by considering the expected difference of 20% at pre-and post-intervention and considering the accuracy of 90% and 95% confidence interval in the following formula:

The sample size was estimated to be 50 in each group considering P1=0.34, P2=0.61, power=0.8, and α=0.05, which was estimated to be 60 in the case of the missing sample. Inclusion criteria were: at least 15 years old and a maximum of 50 years, 2-being a member of one of the men's gym clubs in Sabzevar, exercising at least three times per week. The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to participate in the study and absence from training sessions. Sampling was performed in the clustering method. The bodybuilding clubs whose managers had given their consent and provided the necessary support for the research were selected as the research environment. Two clubs were chosen randomly.

The data collection tools were questionnaires that consisted of two sections: demographic questions and questions that assessed the theory of conservation motivation. The questions such as Supplements help me to have more muscle in less time(Attitude). It's essential for me to my friends’ ideas on my supplement use(Subjective norm). If I have access to supplements, I will use them(Behavioral intention). If they offer me energy supplements, I thank them and answer "no." (Behavioral willingness). In my opinion, anyone who uses supplements is attractive (behavioral imagery). The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed through the expert’s panel and its reliability through Cronbach’s alpha (N=30, α=0.64-0.91).

To comply with ethical considerations, this study was approved by the ethics committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. Written consent was obtained from the participants, and they were ensured that their information would be kept confidential by the researchers. Based on the results that were the educational needs assessment, the academic curriculum and educational content were adjusted. Then, one club was randomly assigned as the intervention group and the second one as the control group. The experimental group received the educational intervention, and the control group received routine training. According to the predictors of supplement usage based on prototype willingness model constructs, the training program lasted six weeks and one training session per week. The training program included questions and answers, brainstorming and group discussion, and educational aids, such as booklets, posters, and short films. There was also a cyberspace group called “No Nutrition Supplements Campaign”. The educational content is tailored to the training classes’ side effects of athletes' nutritional supplements and healthy eating. It was uploaded and converted into the group. It was also asked to invite their friends to influence the subjective norms. Most of the participants had smartphones and also used cyberspace. In the first session, while gaining the satisfaction of the participants in the class, the mobile numbers of the participants in the class were collected; in the social network, a group called Campaign No to Energize supplements was formed in which the educational contents appropriate to the training classes, the side effects of consuming energizing supplements as well as the healthy diet of athletes, and the skills of daring and saying no skills were uploaded in groups and also conversationally in groups. It was necessary to influence the abstract norms; they were also asked to invite their friends to this group. A gift (NO DOPING T-shirt with printed logo) intended by the researcher for the best people in terms of more attendance in classes and more participation in group discussions to increase the motivation of athletes participating in the study is placed. The post-test was done by redistributing the questionnaire one and two months after the educational intervention in both groups.

Descriptive and analytical tests were used for data analysis using SPSS 21 software.

Findings

The study population consisted of 112 bodybuilder athletes in Sabzevar, 95.4% of them were high secondary school and academic level education, 28% businessman, and mean BMI=24.94. About 35% of them and 66% of their families had a history of supplement usage.

According to the results, the rates of the obtained model structures were moderate; among them, the percentage of the obtained score of behavioral attitude and behavioral willingness constructs had the highest and lowest rate of the score, respectively. There was a significant negative correlation between attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral readiness constructs with behavioral intention (p<0.05). At the same time, there was a positive correlation between behavioral imagery and behavioral intention (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of questions and correlation with behavioral intention

The three constructs of attitude, subjective norms, and tendencies (behavioral willingness) accounted for 23.1% of the variance in behavioral intention, among which the effect of the attitude variable was more than the other variables. In addition, the impact of subjective norms on behavioral intention was negative (Table 2). In addition, behavioral sense and behavioral willingness predicted 14% of the variance in behavior; behavioral intention had the most significant impact on behavior. Also, the effect of behavioral readiness was positive on behavior performance, and the effect of intention behavioral intention was negative on behavior.

A significant difference between the mean scores of the model of attitude and tendencies in the experimental and control groups before and two months after the intervention (p<0.05). According to the results, the mean difference indicates a decrease in scores after the intervention (Table 3).

A significant difference between the mean scores of the model of attitude and tendencies in the experimental and control groups before and two months after the intervention (p<0.05). According to the results, the mean difference indicates a decrease in scores after the intervention (Table 3).

Table 2) The effect of imagery model construct and tendencies on behavioral intention based on linear regression model in the target group before intervention

Table 3) Mean±SD results of attitude model constructs in two groups before, after, and two months after the intervention (p<0.001)

Discussion

In this study, 35% of athletes used energy Supplements. Karimian and Saeedi reported 49% and 66% of supplement use, respectively [15, 16]. Though consumption in the present study was lower than in the other studies, more than one-third of athletes in the current study used energy supplements, which is significant and alarming. Due to the side effects of supplement intake [16-19]. Therefore, it is recommended to intervene to raise awareness of the side effects of supplements and design a specific regulatory protocol for the city's bodybuilding clubs with the help of relevant agencies.

We found the attitude score was almost average in the study population, indicating 46. 5% of the participants had a positive attitude toward energy supplements and were at risk of healthy supplement usage. Abedini showed that the more people's attitudes toward supplement use, the more they will use supplements [27]. Mood was the most critical predictor of dietary supplement intake, and a significant positive correlation was observed between attitude and behavior. These findings agree with the studies [28-30] that providing a healthy diet plan to replace energy supplements could significantly impact supplement intake. Since the results showed that attitudes are more common in married people and those living single, these factors can influence designing effective intervention programs. There was a score reduction in the mean attitude construct in the experimental group compared to the control group 2 months after the intervention. These changes may indicate the effectiveness of a training program to raise awareness and reduce athletes' positive attitudes toward nutritional supplements. This is consistent with Mohammad Hassan Saati et al. [31], which showed a reduction of 1.16 score to a positive attitude toward the use of nutritional supplements after the educational intervention, from 18. 51 to 17.35.

The subjective norms obtained in the study population were moderate, and 66% of their relatives had a history of complement use. Subjective norms are the pressure a person feels on the part of people who are important to them to do or not to behave [32]. Therefore, educational planning for peers in this group played a significant role. These results are in agreement with the data of the study [31], which showed a statistically significant difference between the use of complement (anabolic steroids) and subjective norm construct (p=0.040). A negative correlation between the mean of the subjective norms with the behavior was found, while the subjective norms after attitude were the second predictor of intention to supplement intake. These results correspond with Mehri and Bashirian, indicating that subjective norms were the most important predictors [33, 34]. It can be argued that, as much as possible, through educational interventions, the average subjective norms and pressure felt by individuals’ important persons be reduced, and the intake of the supplement will be reduced. The present study results showed that the mean score of "subjective norms" decreased two months after the educational intervention in the experimental group.

They knew that the study groups are young and the peers’ role in accepting one behavior is essential. The part of education and transfer of educational experiences through influential individuals is practical. This result indicates the effect of a training program on participants. These results are consistent with Saati et al. [31] on the program's effect on the prevention and reduction of anabolic steroid consumption and the findings of Heidarnia et al. on the impact of the program's educational intervention on smoking prevention [35].

Behavioral willingness was also one of the predictors of the behavioral intention of supplement intake. These results are in line with the data given by studies [36, 37]. The percentage of behavioral willingness obtained score was moderate in the study subjects. In designing training programs to promote healthy behaviors, people should be trained to increase their ability to recognize high-risk behaviors and resist peer pressure. Participants should learn to express opposition and address social anxiety in situations where it is not necessary to say so. Resolve their conflicts constructively and achieve a better ability to control arousal and social communication. The present study results showed a decrease in the mean of "behavioral willingness” in the experimental group compared to the control group 2 months after the intervention. These changes may indicate that the training program effectively reduces athletes' willingness for supplement use. The less willing the risky behavior declines, which is consistent with studies [31, 35]. In the study of Saati, the educational intervention reduced the mean score of willingness for consuming nutritional supplements by 0.62 (from 9.38 to 8. 76 after the intervention) [31]. In the study of Hydernia et al., the mean score of behavioral willingness after the intervention was reduced.

The percentages of behavioral imagery were above average. Behavioral imagery is a person's mental perception of their peers involved in a particular high-risk behavior [22]. These results are consistent with the data of Zahra Serlak et al., showing that adolescents have clear social images of their peers who are engaged in high-risk behaviors [38]. The present study results showed a decrease in the mean Behavioral Imagery constructs in the experimental group compared to the control group 2 months after the intervention. . It is important to note that people's perception of behavior plays a vital role in their choice of conduct. Therefore, educational intervention should reduce one's perceptions of negative behaviors. The findings of this study agree with the conclusions from Heidarnia et al. In the survey of Heidarnia, the results showed a decrease in the mean behavioral imagery after educational intervention [35]. More than half of the population surveyed intended to use energy supplements in the future, indicating the need for educational planning on dietary supplements and alternative energy supplements. Since behavioral intentions were predictors of supplement intake, educational interventions aimed at energy supplement intake could lead to reduced supplement consumption. The scores of behavioral intention construct in the experimental group decreased two months after the intervention. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the current educational program in reducing athletes' behavioral intention in supplement use. in the study Saati, after the intervention, the use of anabolic steroids was reduced [31]. These data correspond with Jaliyan et al. reporting a significant reduction in using the supplement in the experimental group after the educational intervention program [39]. Many issues must be considered while interpreting the results of this study: first, the majority of the participants had a high level of education (academic degree). Therefore, the results may not generalize to other populations. We used a regional sample from Sabzevar City that may not represent the whole population in Iran. And finally, since self-report was used to collect data, the social desirability concerns of the participants may have affected their responses. Another limitation of the current study was the cross-sectional design.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the study educational interventions in the study population are necessary. Applying this model to the predictive dimension showed that the path of rational behavior has more predictive power than the social response path and in the formation of behavioral intentions. Subjective norms can be one of the most critical factors driving the consumption of supplements. The attitude/tendency model can be used for educational interventions. The results also indicated the effectiveness of the present intervention in reducing the use of energy Supplements. Therefore, educational interventions based on the model of attitude/tendency model to reduce the consumption of energy Supplements are recommended.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank all the participants for their sincere cooperation in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This article is retrieved from the research project approved by Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences with the Ethics committee reference number IR.MEDSAB.REC.1397.006.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared

Authors’ Contributions: Mehri A (First Author), Introduction Writer /Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Soltani H (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (20%); Hosseini ZS (Third Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (10%); Hashemian M (Forth Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (15%); Joveini H (Fifth author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (10%); Shahrabadi R (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/ Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: the Vice-Chancellor supported for Research and Technology of this university.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2022/04/2 | Accepted: 2022/07/15 | Published: 2022/09/10

Received: 2022/04/2 | Accepted: 2022/07/15 | Published: 2022/09/10

References

1. Porrini M, Del Boʼ C. Ergogenic aids and supplements. Front Horm Res. 2016;47:128-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000445176]

2. Jeukendrup AE. Periodized nutrition for athletes. Sports Med. 2017;47(Suppl 1):51-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40279-017-0694-2]

3. Mujika I, Stellingwerff T, Tipton K. Nutrition and training adaptations in aquatic sports. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2014;24(4):414-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0033]

4. ods.od.nih.gov [Internet]. Rockledge: National Institute of Health; 2013 [2022 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/. [Link]

5. Knapik JJ, Steelman RA, Hoedebecke SS, Austin KG, Farina EK, Lieberman HR. Prevalence of dietary supplement use by athletes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(1):103-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40279-015-0387-7]

6. Attlee A, Haider A, Hassan A, Alzamil N, Hashim M, Obaid RS. Dietary supplement intake and associated factors among gym users in a university community. J Diet Suppl. 2018;15(1):88-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/19390211.2017.1326430]

7. Whitehouse G, Lawlis T. Protein supplements and adolescent athletes: a pilot study investigating the risk knowledge, motivations and prevalence of use. Nutr Diet. 2017;74(5):509-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1747-0080.12367]

8. Garcez Nabuco HC, Behrends Rodrigues V, Souza Fernandes VL, de Paula Ravagnani FC, Fett CA, Martínez Espinosa M, et al. Factors associated with dietary supplementation among Brazilian athletes. Nutr Hosp. 2016;33(3):278. [Spanish] [Link]

9. Austin KG, Price LL, McGraw SM, Lieberman HR. Predictors of dietary supplement use by U. S. coast guard personnel. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):0133006. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0133006]

10. Frączek B, Warzecha M, Tyrała F, Pięta A. Prevalence of the use of effective ergogenic aids among professional athletes. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2016;67(3):271-8. [Link]

11. Sassone J, Muster M, Barrack MT. Prevalence and predictors of higher-risk supplement use among collegiate athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(2):443-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002979]

12. Casey A, Hughes J, Izard RM, Greeves JP. Supplement use by UK-based British army soldiers in training. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(7):1175-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0007114514001597]

13. Saeedi P, Mohd Nasir MT, Hazizi AS, Vafa MR, Rahimi Foroushani A. Nutritional supplement use among fitness club participants in Tehran, Iran. Appetite. 2013;60(1):20-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.011]

14. Karimian J, Esfahani PS. Supplement consumption in body builder athletes. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(10):1347-53. [Link]

15. Darvishi L, Askari G, Hariri M, Bahreynian M, Ghiasvand R, Ehsani S, et al. The use of nutritional supplements among male collegiate athletes. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(Suppl 1):68-72. [Link]

16. Knapik JJ, Trone DW, Austin KG, Steelman RA, Farina EK, Lieberman HR. Prevalence, adverse events, and factors associated with dietary supplement and nutritional supplement use by US navy and marine corps personnel. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):1423-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jand.2016.02.015]

17. di Lorenzo C, Ceschi A, Kupferschmidt H, Lüde S, de Souza Nascimento E, dos Santos A, et al. Adverse effects of plant food supplements and botanical preparations: a systematic review with critical evaluation of causality. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(4):578-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bcp.12519]

18. Kumar Samal JR, Samal IR. Protein supplements: pros and cons. J Diet Suppl. 2018;15(3):365-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/19390211.2017.1353567]

19. Ronis MJJ, Pedersen KB, Watt J. Adverse effects of nutraceuticals and dietary supplements. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;58:583-601. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052844]

20. Glanz K, Rimer B K, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. New York: John Wily & Sons; 2008. [Link]

21. Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):87-98. [Link] [DOI:10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87]

22. Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Blanton H, Russell DW. Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention a sin dependent predictors of health risk. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(5):1164-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1164]

23. Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social reaction model of adolescent health risk. In: Wallston S, editor. Social psychological foundationsof health and illness. Malden: Blackwell; 2003. [Link]

24. Asghari Jafarabadi M, Nadrian H, Allahverdipour H. Social reactions and reasoned pathways of high school students and school dropouts' inclination toward smoking behavior: prototype/willingness modelling via generalized structural equation. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(9):1354-63. [Link]

25. Goel S, Kathiresan J, Singh P, Singh RJ. Effect of a brief smoking cessation intervention on adult tobacco smokers with pulmonary tuberculosis: a cluster randomized controlled trial from North India. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61(Suppl 1):S47-53. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijph.IJPH_265_17]

26. Ghodsi M, Maheri M, Joveini H, Rakhshani MH, Mehri A. Designing and evaluating educational intervention to improve preventive behavior against cutaneous leishmaniasis in endemic areas in Iran. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2019;10(4):253-62. [Link] [DOI:10.24171/j.phrp.2019.10.4.09]

27. Abedini S, MorowatiSharifabad M, Chaleshgar Kordasiabi M, Ghanbarnejad A. Predictors of non- hookah smoking among high-school students based on prototype/willingness model. Health Promot Perspect. 2014;4(1):46-53. [Link]

28. Mehri A, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Morowatisharifabad MA, Nadrian H. Determinants of helmet use behaviour among employed motorcycle riders in Yazd, Iran based on theory of planned behaviour. Injury. 2011;42(9):864-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.030]

29. Whitaker L, Long J, Petróczi A, Backhouse SH. Using the prototype willingness model to predict doping in sport. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(5):e398-405. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/sms.12148]

30. Guo JL, Wang TF, Liao JY, Huang CM. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior in predicting breastfeeding: meta-analysis and structural equation modeling. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:37-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.016]

31. Saati Asr MH, Heidari Moghadam R, Bashirian S, Barati M. Effectiveness of educational program based on prototype willingness model on preventing and decreasing anabolic-androgenic steroids among male bodybuilders. KOOMESH. 2018;20(2):263-73. [Persian] [Link]

32. Peña J, Hernández Pérez JF, Khan S, Cano Gómez ÁP. Game perspective-taking effects on players' behavioral intention, attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy to help immigrants: the case of "papers, please". Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21(11):687-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2018.0030]

33. Mehri A, Nadrian H, Morowatisharifabad MA, Akolechy M. Determinants of seat belt use among drivers in Sabzevar, Iran: a comparison of theory of planned behavior and health belief model. Traffic Inj Prev. 2011;12(1):104-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15389588.2010.535227]

34. Bashirian S, Hidarnia A, Allahverdipour H, Hajizadeh E. Application of the theory of planned behavior to predict drug abuse related behaviors among adolescents. J Res Health Sci. 2012;12(1):54-60. [Link]

35. Heidarnia A, Barati M, Niknami S, Allahverdipour H, Bashirian S. Effect of a web-based educational program on prevention of tobacco smoking among male adolescents: an application of prototype willingness model. J Educ Community Health. 2016;3:1-11. [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech-03011]

36. Eslami AA, Jalilian F, Ataee M, Alavijeh MM, Mahboubi M, Afsar A, et al. Intention and willingness in understanding Ritalin misuse among Iranian medical college students: a cross-sectional study. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6(6):43-53. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p43]

37. Mirzaei-Alavijeh M, Babakhani M, Jalilian F, Vaezi M, Jalilian F, Khashij S, et al. Socio-cognitive determinants of safe road-crossing behaviors: an application of the prototype willingness model. J Inj Violence Res. 2019;11(1):93-100. [Link] [DOI:10.5249/jivr.v11i1.1078]

38. Sarlak Z, Kashi A. The study of effective factors in the use of banned drugs and supplements in newborns in high school students. YAFTEH. 2010;11(3):101-14. [Persian] [Link]

39. Jalilian F, Allahverdipour H, Moeini B, Moghimbeigi A. Effectiveness of anabolic steroid preventative intervention among gym users: Applying theory of planned behavior. Health Promot Perspect. 2011;1(1):32-40. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |