Volume 10, Issue 2 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(2): 277-283 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rahimi Khalifeh Kandi Z, Estebsari F, Jalilibahabadi F, Sheikh Milani A, Estebsari K, Mostafaei D. Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life of Pregnant Women Based on Pender’s Model Constructs. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (2) :277-283

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-52867-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-52867-en.html

Z. Rahimi Khalifeh Kandi1, F. Estebsari *2, F. Jalilibahabadi3, A. Sheikh Milani2, K. Estebsari4, D. Mostafaei5

1- Department of Health Education, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran

3- “Student Research Committee” and “Community Health Nursing Department, School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Azna Health Center, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

5- Shahada Tajrish Hospital, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran

3- “Student Research Committee” and “Community Health Nursing Department, School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Azna Health Center, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

5- Shahada Tajrish Hospital, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 560 kb]

(3734 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1863 Views)

Full-Text: (430 Views)

Introduction

Quality of life (QoL) is a broad concept that encompasses all aspects of life, including health. This concept, which is related to physical, social, spiritual, psychological, and economic dimensions [1], involves various areas such as disease and treatment, mental health, and social and economic well-being [2]. Many factors, with health being the most important one, affect QoL [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided a comprehensive definition of QoL as "understanding people's state of life in the dominant culture and values governing society in line with their goals, expectations, standards, and interests" [4]. Therefore, quality of life is rooted in cultural, social, and environmental contexts [5]. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) affects an individual's subjective assessment of their current health status and allows one to pursue valuable life goals [6].

Pregnancy is a common event but one of the most considerable stages of a women's reproductive life. Although it may be a pleasant time for most women, it can also be considered stressful with physiological and psychological changes [7]. These changes can have an important impact on the daily routines of pregnant women and even alter their ability to perform everyday life activities [8]. The reason is that, during pregnancy, a woman’s physical, mental, and social health and overall quality of life change significantly [9, 10]. In this respect, one of the most important goals of prenatal care is to maintain and improve maternal and fetal health and improve the quality of life of women during this period [11].

Since QoL plays an important role in the health of pregnant women, knowing its controlling factors in this period and understanding the items affecting it can lead to effective strategies to improve the quality of pregnancy services and, in turn, the QoL in this group of people. Several studies have been carried out on the factors affecting the QoL of pregnant women. However, the present study aimed to investigate the predictors of quality of life in pregnant women based on Pender's health promotion model. In Pender model, barriers, benefits, self-efficacy, positive and negative affect, and social support were studied. In comparison, the present study aimed to examine the relationship between these structures with the quality of life of pregnant women, which has not been studied in other works.

Instrument & Methods

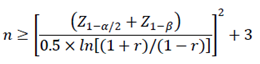

The present descriptive correlational study was conducted on pregnant women who received pregnancy care in Yazd Community Health Center in 2018. Using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient Sample Size Formula, α=0.05, Probability of Type I Error, power of test 1-β=0.9, r=0.2 (which is r in this formula), 259 individuals were chosen in this study. Eventually, with a probability of 15% of sample dropout, the sample size was 300 people.

After obtaining permission from all the pregnant women with care records in their second and third trimesters, 300 individuals were selected by simple random sampling in a draw. Pregnant mothers with high-risk pregnancy problems (e.g., bleeding, sac rupture, preeclampsia, or eclampsia) and gestational diabetes with insulin injections and other chronic diseases were excluded from the study. The research questionnaires were completed by holding face-to-face interviews. Before completing the questionnaires, the aims and details were described to the participants. They were assured that their information would be kept confidential, the results would only be used for research purposes, and only aggregated results would be published. Written consent was obtained from the samples. The literate pregnant mothers completed the questionnaires themselves. For illiterate and unlearned pregnant women, the questionnaires were completed with the help of a researcher, and the way the questionnaires were completed was carefully monitored.

The study data were collected through a demographic questionnaire including age, education, spouse's education, spouse's occupation, gestational age, and BMI, health-related quality of life questionnaire (the standard version 12-item Short-Form Health Survey v.1), and Pender’s model constructions (Pender's health promotion model).

Health-Related Quality of Life: The standard version 12-item Short-Form Health Survey v.1 was adapted from Ware et al. It has 12 questions and examines the physical and mental health aspects. The SF12v2 questionnaire is the short form of the SF-36 questionnaire, which is used as a valid instrument to measure HRQoL [12, 13]. The tool consists of 8 sub-scales (dimensions): Physical functioning (2 items), limitation in functioning due to physical problems (Role of physical activity (2 items), Body pain (1 item), General Understanding of Health (1 item), Vitality (1 item), Social Functioning (1 item), limitation in functioning due to mental problems (Role Emotional (2 items), and Mental Health (2 items). In this questionnaire, the physical health dimension is assessed by asking 6 questions, 4 of which are 3-point and 5-point Likert scales, and 2 questions have Yes/No answers. The mental health dimension includes 6 questions, including 4 questions with a 5-point Likert scale with six options and 2 with Yes/No answers. This tool has been validated for the Iranian population, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.73 for the physical health dimension and 0.72 for the mental health dimension [13]. Quality Metric Health Outcomes Scoring software version 2 was used to calculate QoL's physical and mental dimensions. The software uses all 12 items to provide the scores of physical and mental dimensions of QoL and employs a normative calculation algorithm derived from information from the American general population. Accordingly, the assumption for the mean in this questionnaire is calculated as norm 50 and standard deviation 10. Possible scores for the physical and mental dimensions ranged from 0=worst to 100=most favorable [14]. Also, Cronbach's alpha coefficient and test-retest test reliability were respectively 0.76 and 0.81 for the present study.

Pender's model construction: The items of Pender's health promotion model include Perceived self-efficacy, Perceived Affect, Perceived social support, Perceived benefits, and Perceived Barriers. Perceived self-efficacy constructs were derived from the Health Locus of Control Scale [5]. This scale includes 8 questions based on a 5-point Likert scale of a completely opposite spectrum (1 Point) to totally agree (5 points). The range of scales obtainable on this scale ranged from 8 to 40. A higher score indicates a person's greater ability to control the outcomes and outcomes of health-related programs [15]. The questionnaire was designed with 12 questions from the 7-point Likert scale, scoring from completely disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (7 points). The acceptable score ranged from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater support from friends, family, and other important individuals [5]. The construct of perceived barriers is adapted from Becker et al. This tool has 18 questions based on the 4-point Likert scale options ranging from never (1 point) to always (4 points). The scales obtainable on this scale ranged from 18 to 72. A higher score indicates more obstacles [5]. For the Perceived Benefits construct, the Mohammadian et al. [15] tool was used. This tool consists of 20 questions based on the 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (7 points). The range of achievable scores was between 20 and 140, with a higher score indicating more benefits [16]. The validity was determined by calculating their content validity. For this purpose, criteria including content validity included Content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were calculated. The necessity or non-necessity of each question was examined for calculating the CVR. In comparison, each question's relevance, clarity, and simplicity were examined for calculating the CVI. For validation, the questionnaires were given to 10 experts, including community health nursing professors (n=4), maternal and child health professionals (n=3), and family health professionals (n=3). According to the table of Lawshe, for the CVR, the minimum value for 10 experts is 0.62. In the present study, all questions scored above 0.62. According to the table of Lawshe, for the CVI, the minimum value for ten experts is 0.7. In the present study, the validity of all questions was approved. To specify the internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha was determined, which was 0.92 for social support, 0.74 for self-efficacy, 0.90 for perceived barriers, 0.84 for perceived effect, 0.77 for the perceived benefit dimension, and 0.76 for the HRQoL.

The present study was the product of a research project approved by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The anonymity of the participants was considered in the questionnaires, and the purpose of the research was stated to them before starting the research. Also, they were assured that their information was confidential and would be used only for the research and published anonymously. Before completing the questionnaire, written informed consent was obtained from the participants and completed face-to-face.

After data collection, they were entered into SPSS software version 18. At first, the data normality was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov, and it was found that the data were normally distributed. Descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (Pearson correlation coefficient and multiple linear regression model) were used for data analysis. The confidence interval considered for the analyses was 0.95%.

Findings

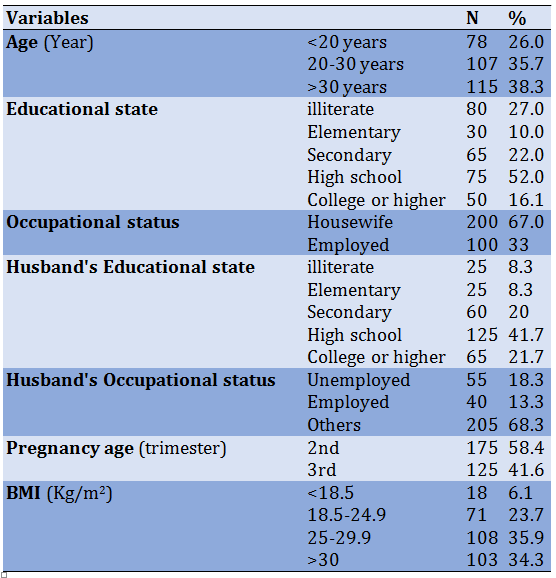

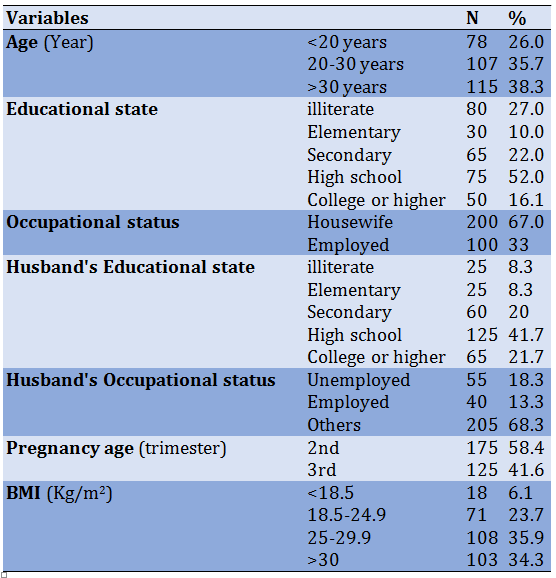

The mean age of pregnant mothers was 32.85±6.11. About 27% of mothers were illiterate, and the rest were literate. Also, 66% of mothers were housewives, and the rest were employed (Table 1).

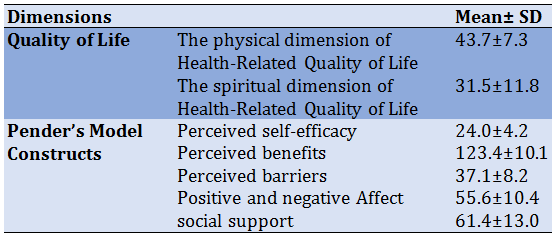

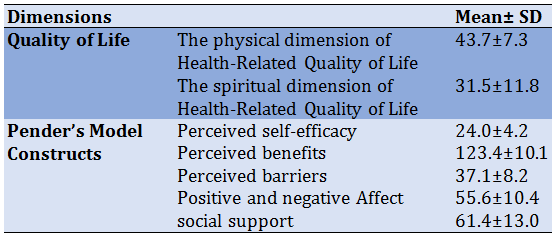

According to the results, the score of HRQoL for the physical dimension was greater than for the psychological dimension. Among Pender's model constructs, perceived benefits had the highest score, and self-efficacy had the lowest score (Table 2).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of demographic variables of pregnant women

Table 2) Mean of health-related quality of life dimensions according to demographic variables

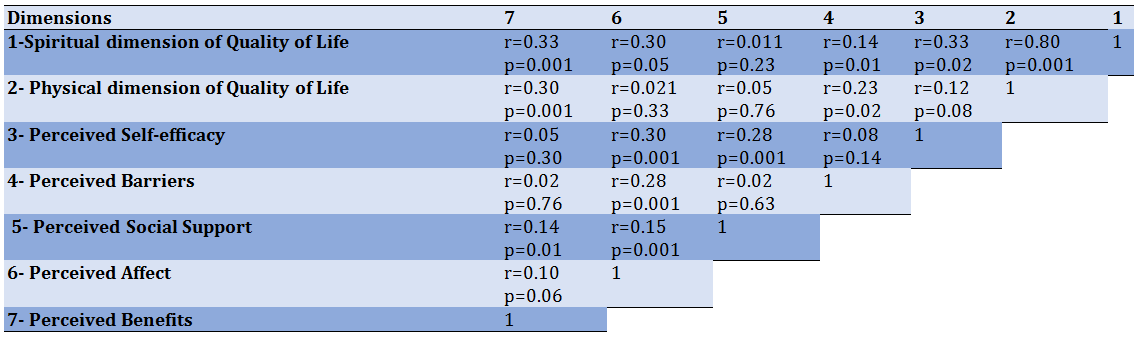

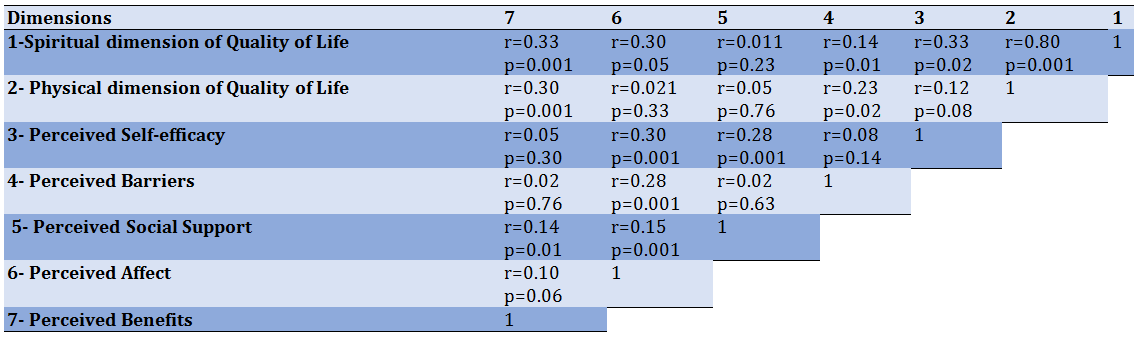

According to the results of Table 3, the Pearson correlation coefficient test showed a significant correlation between the psychological dimension of QoL and self-efficacy, perceived effects, perceived barriers, and perceived benefits (p<0.05). There was also a significant correlation between the physical dimension of QoL, perceived barriers, and perceived benefits (p<0.05). The results showed a statistically significant correlation between self-efficacy, social support, and perceived effects among Pender's model constructs (p<0.05). Besides, there was also a significant correlation between perceived barriers and perceived effects (p<0.05). Finally, there was also a significant correlation between social support and perceived effects and perceived benefits (p<0.05).

Table 3) Correlation matrix of quality of life dimensions related to pender model structures

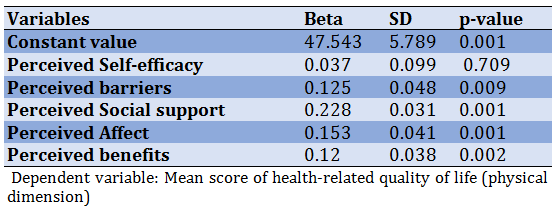

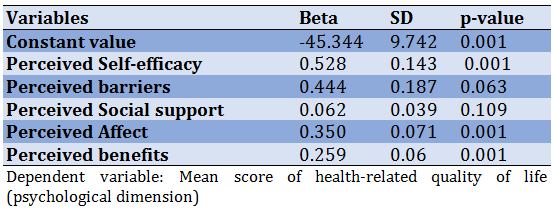

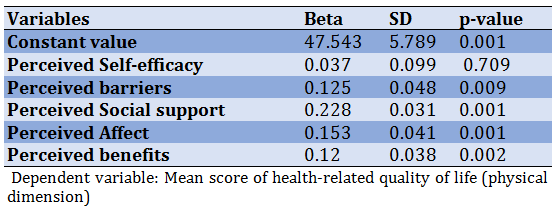

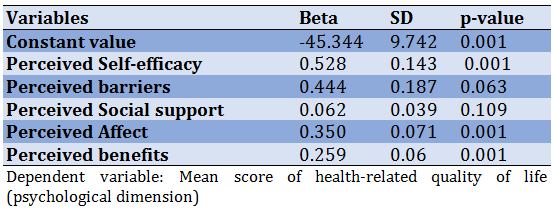

The results of regression analysis (Table 4) showed that the variables of perceived barriers, social support, positive and negative effect, and perceived benefits had significant effects on the physical dimension of HRQoL (p<0.05). Moreover, the variables of positive and negative affect, self-efficacy, and perceived benefits influenced the psychological dimension of HRQoL (Table 5).

Table 4) Evaluating the simultaneous effects of Pender's model components on the physical dimension of health-related quality of life in pregnant women

Table 5) Simultaneous effects of Pender's model components on the psychological dimension of health-related quality of life in pregnant women

Discussion

This research was conducted to investigate the predictors of HRQoL in pregnant women based on the Pender Health Promotion Model. In the present study, the mean physical dimension of HRQoL was higher than the mean of the psychological dimension of HRQoL in pregnant women, which is consistent with some studies [17, 18]. In these studies, pregnant women were aware of and sensitive to weight changes during pregnancy and had a coherent program of physical activity to prepare for childbirth and maintain fitness [19]. Other studies have shown that women do less physical activity during pregnancy due to physical problems and mental and psychological conditions [2, 20, 21]. Accordingly, women are advised to participate in moderate activity for 30 minutes or more on most days of the week to prevent medical or midwifery complications [18]. It may be argued that the low psychological dimension of HRQoL is related to women's mental and psychological changes during pregnancy. In fact, pregnant women are susceptible to a variety of tensions and can become more depressed and anxious than other women [22].

The score of psychological dimensions of Qol in pregnant women in this study was lower than the physical dimension. Therefore, it can be concluded that psychological measures and support, especially from the spouse and life, can help to improve the psychological dimension of QoL. Such improvement will enhance pregnant women's self-efficacy to understand better the problems and difficulties associated with pregnancy. Equally perceived effect and subsequently perceived benefits will change and ultimately affect the psychological health dimension of QoL [18]. Robinson argues that successful individuals have a high self-efficacy and thus a high QoL [23]. As a factor affecting the quality of life, self-efficacy emphasizes one's understanding of one's skills and ability to do a good job. In other words, self-efficacy affects understanding adaptive behaviors and functions and choosing the environment and conditions individuals strive to achieve [24].

Concerning the Pender Health Promotion Model constructs in pregnant women, the score of perceived benefits had the highest mean, suggesting that participants in the study had a high perception of the benefits of performing health-promoting behaviors. This result is not surprising given the participants' educational and occupational conditions and youth. The lowest score was related to perceived self-efficacy, referring to the participants' young age, inadequacy, and inexperience. There are no reliable articles to compare and analyze HRQoL in pregnant women based on the Pender model. However, Goodarzi et al. evaluated the effect of a nutrition education program on dietary pattern improvement during pregnancy. When performing Pender’s health promotion, the highest score was related to the behavioral construct of effect, while the lowest score was to the barriers to health promotion activities [25]. This inconsistency may be attributed to prim parous participant samples who are emotionally in better condition. In the present study, among the constructs of Pender's health promotion model, perceived self-efficacy had the lowest score. This result suggests that pregnant women may be in more doubt about their abilities in controlling and its consequences due to their pregnancy condition. Since the psychological dimension of QoL had the lowest score and self-efficacy was a factor affecting the psychological dimension of the present study, it is necessary to improve the psychological dimension of their QoL by interventions to increase self-efficacy in pregnant women [15, 25, 26].

Regarding the relationship between Pender’s Health Promotion Model constructs and HRQoL dimensions, a regression test in pregnant women showed that perceived self-efficacy constructs and perceived effects and benefits have the most effects on the psychological dimension of quality of life in pregnant women's pregnant women lives. Self-efficacy is people’s belief about their ability and capacity to perform a task or face life challenges. Women with high self-efficacy will have a better understanding of their abilities. Therefore, they are more likely to benefit from behaviors that lead to improved quality of life. As a result, their perceived effect and QoL will improve. The results of this study are in line with other studies [15, 27]. In the study of Bahabadi et al., constructs of self-efficacy and perceived effect had the highest predictive power of quality of life, respectively [5]. In the study of Han et al., perceived self-efficacy directly affects QoL's psychological and physical dimensions [28]. This result is consistent with the present study in terms of the effect of self-efficacy on the psychological dimension. Feelings of self-efficacy can affect the psychological dimension of QoL in pregnant women in the present study. In other words, the more pregnant women are confident in their ability to control health behaviors, the better the QoL they will have in the psychological dimension. Feelings of self-efficacy can affect all aspects of life, including psychological dimensions. Research has shown that people who are confident in their abilities are actively involved in health promotion programs and can effectively manage their life events [29]. Self-efficacy can also improve the psychological dimension of QoL through perceived affect. Therefore, further studies focusing on improving self-efficacy in pregnant women can promote a healthier lifestyle and a better and healthier QoL.

The regression test results showed that perceived barriers, social support, affect, and perceived benefits affect the physical dimension of QoL. Emmanuel et al. reported a significant impact of social support on QoL in pregnant women, especially the physical aspect of QoL [30], which is consistent with the present study. Family support, especially that from the spouse, enables women to have a more positive view of pregnancy, better understand the barriers to health behaviors, and focus more on the benefits of such behaviors. In the present study, pregnant women had relatively favorable emotions, which could directly influence perceived self-efficacy in health choices and quality of life. Using linear regression models to determine the relationship and type of relationship between variables is considered among the strengths of the present research. On the other hand, one of the disadvantages of this study is the limited sample size in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy due to the lack of accurate information regarding the first trimester of pregnancy. Therefore, further studies on QoL are recommended in early pregnancy samples.

Conclusion

According to the results, perceived effect, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived benefits constructs are suitable for the psychological dimension of HRQoL, perceived barrier constructs, and social support effects. The perceived benefits are appropriate for predicting the physical dimension of quality of life. Therefore, it is suggested to improve the QoL and enhance perceived self-efficacy in pregnant women by encouraging them to adopt health-promoting behaviors. To this end, studies and educational interventions emphasizing the Pender Health Promotion Model constructs are also recommended.

Acknowledgment: We would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for the financial support given toward this study.

Ethical Permission: The present study is the product of a research project approved by IR.SBMU.RETECH.1397.27of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest has been reported in this study.

Authors' Contribution: Rahimi Khalifeh Kandi Z (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (25%); Estebsari F (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Jalilibahabadi F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/

Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (15%); Sheikh Milani A (Forth author), Discussion Writer (15%); Estebsari K (Fifth author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Mostafaei D (Sixth authr), Introduction Writer/ Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Supports: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences support financial this study.

Quality of life (QoL) is a broad concept that encompasses all aspects of life, including health. This concept, which is related to physical, social, spiritual, psychological, and economic dimensions [1], involves various areas such as disease and treatment, mental health, and social and economic well-being [2]. Many factors, with health being the most important one, affect QoL [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided a comprehensive definition of QoL as "understanding people's state of life in the dominant culture and values governing society in line with their goals, expectations, standards, and interests" [4]. Therefore, quality of life is rooted in cultural, social, and environmental contexts [5]. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) affects an individual's subjective assessment of their current health status and allows one to pursue valuable life goals [6].

Pregnancy is a common event but one of the most considerable stages of a women's reproductive life. Although it may be a pleasant time for most women, it can also be considered stressful with physiological and psychological changes [7]. These changes can have an important impact on the daily routines of pregnant women and even alter their ability to perform everyday life activities [8]. The reason is that, during pregnancy, a woman’s physical, mental, and social health and overall quality of life change significantly [9, 10]. In this respect, one of the most important goals of prenatal care is to maintain and improve maternal and fetal health and improve the quality of life of women during this period [11].

Since QoL plays an important role in the health of pregnant women, knowing its controlling factors in this period and understanding the items affecting it can lead to effective strategies to improve the quality of pregnancy services and, in turn, the QoL in this group of people. Several studies have been carried out on the factors affecting the QoL of pregnant women. However, the present study aimed to investigate the predictors of quality of life in pregnant women based on Pender's health promotion model. In Pender model, barriers, benefits, self-efficacy, positive and negative affect, and social support were studied. In comparison, the present study aimed to examine the relationship between these structures with the quality of life of pregnant women, which has not been studied in other works.

Instrument & Methods

The present descriptive correlational study was conducted on pregnant women who received pregnancy care in Yazd Community Health Center in 2018. Using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient Sample Size Formula, α=0.05, Probability of Type I Error, power of test 1-β=0.9, r=0.2 (which is r in this formula), 259 individuals were chosen in this study. Eventually, with a probability of 15% of sample dropout, the sample size was 300 people.

After obtaining permission from all the pregnant women with care records in their second and third trimesters, 300 individuals were selected by simple random sampling in a draw. Pregnant mothers with high-risk pregnancy problems (e.g., bleeding, sac rupture, preeclampsia, or eclampsia) and gestational diabetes with insulin injections and other chronic diseases were excluded from the study. The research questionnaires were completed by holding face-to-face interviews. Before completing the questionnaires, the aims and details were described to the participants. They were assured that their information would be kept confidential, the results would only be used for research purposes, and only aggregated results would be published. Written consent was obtained from the samples. The literate pregnant mothers completed the questionnaires themselves. For illiterate and unlearned pregnant women, the questionnaires were completed with the help of a researcher, and the way the questionnaires were completed was carefully monitored.

The study data were collected through a demographic questionnaire including age, education, spouse's education, spouse's occupation, gestational age, and BMI, health-related quality of life questionnaire (the standard version 12-item Short-Form Health Survey v.1), and Pender’s model constructions (Pender's health promotion model).

Health-Related Quality of Life: The standard version 12-item Short-Form Health Survey v.1 was adapted from Ware et al. It has 12 questions and examines the physical and mental health aspects. The SF12v2 questionnaire is the short form of the SF-36 questionnaire, which is used as a valid instrument to measure HRQoL [12, 13]. The tool consists of 8 sub-scales (dimensions): Physical functioning (2 items), limitation in functioning due to physical problems (Role of physical activity (2 items), Body pain (1 item), General Understanding of Health (1 item), Vitality (1 item), Social Functioning (1 item), limitation in functioning due to mental problems (Role Emotional (2 items), and Mental Health (2 items). In this questionnaire, the physical health dimension is assessed by asking 6 questions, 4 of which are 3-point and 5-point Likert scales, and 2 questions have Yes/No answers. The mental health dimension includes 6 questions, including 4 questions with a 5-point Likert scale with six options and 2 with Yes/No answers. This tool has been validated for the Iranian population, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.73 for the physical health dimension and 0.72 for the mental health dimension [13]. Quality Metric Health Outcomes Scoring software version 2 was used to calculate QoL's physical and mental dimensions. The software uses all 12 items to provide the scores of physical and mental dimensions of QoL and employs a normative calculation algorithm derived from information from the American general population. Accordingly, the assumption for the mean in this questionnaire is calculated as norm 50 and standard deviation 10. Possible scores for the physical and mental dimensions ranged from 0=worst to 100=most favorable [14]. Also, Cronbach's alpha coefficient and test-retest test reliability were respectively 0.76 and 0.81 for the present study.

Pender's model construction: The items of Pender's health promotion model include Perceived self-efficacy, Perceived Affect, Perceived social support, Perceived benefits, and Perceived Barriers. Perceived self-efficacy constructs were derived from the Health Locus of Control Scale [5]. This scale includes 8 questions based on a 5-point Likert scale of a completely opposite spectrum (1 Point) to totally agree (5 points). The range of scales obtainable on this scale ranged from 8 to 40. A higher score indicates a person's greater ability to control the outcomes and outcomes of health-related programs [15]. The questionnaire was designed with 12 questions from the 7-point Likert scale, scoring from completely disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (7 points). The acceptable score ranged from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater support from friends, family, and other important individuals [5]. The construct of perceived barriers is adapted from Becker et al. This tool has 18 questions based on the 4-point Likert scale options ranging from never (1 point) to always (4 points). The scales obtainable on this scale ranged from 18 to 72. A higher score indicates more obstacles [5]. For the Perceived Benefits construct, the Mohammadian et al. [15] tool was used. This tool consists of 20 questions based on the 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (7 points). The range of achievable scores was between 20 and 140, with a higher score indicating more benefits [16]. The validity was determined by calculating their content validity. For this purpose, criteria including content validity included Content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were calculated. The necessity or non-necessity of each question was examined for calculating the CVR. In comparison, each question's relevance, clarity, and simplicity were examined for calculating the CVI. For validation, the questionnaires were given to 10 experts, including community health nursing professors (n=4), maternal and child health professionals (n=3), and family health professionals (n=3). According to the table of Lawshe, for the CVR, the minimum value for 10 experts is 0.62. In the present study, all questions scored above 0.62. According to the table of Lawshe, for the CVI, the minimum value for ten experts is 0.7. In the present study, the validity of all questions was approved. To specify the internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha was determined, which was 0.92 for social support, 0.74 for self-efficacy, 0.90 for perceived barriers, 0.84 for perceived effect, 0.77 for the perceived benefit dimension, and 0.76 for the HRQoL.

The present study was the product of a research project approved by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The anonymity of the participants was considered in the questionnaires, and the purpose of the research was stated to them before starting the research. Also, they were assured that their information was confidential and would be used only for the research and published anonymously. Before completing the questionnaire, written informed consent was obtained from the participants and completed face-to-face.

After data collection, they were entered into SPSS software version 18. At first, the data normality was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov, and it was found that the data were normally distributed. Descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (Pearson correlation coefficient and multiple linear regression model) were used for data analysis. The confidence interval considered for the analyses was 0.95%.

Findings

The mean age of pregnant mothers was 32.85±6.11. About 27% of mothers were illiterate, and the rest were literate. Also, 66% of mothers were housewives, and the rest were employed (Table 1).

According to the results, the score of HRQoL for the physical dimension was greater than for the psychological dimension. Among Pender's model constructs, perceived benefits had the highest score, and self-efficacy had the lowest score (Table 2).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of demographic variables of pregnant women

Table 2) Mean of health-related quality of life dimensions according to demographic variables

According to the results of Table 3, the Pearson correlation coefficient test showed a significant correlation between the psychological dimension of QoL and self-efficacy, perceived effects, perceived barriers, and perceived benefits (p<0.05). There was also a significant correlation between the physical dimension of QoL, perceived barriers, and perceived benefits (p<0.05). The results showed a statistically significant correlation between self-efficacy, social support, and perceived effects among Pender's model constructs (p<0.05). Besides, there was also a significant correlation between perceived barriers and perceived effects (p<0.05). Finally, there was also a significant correlation between social support and perceived effects and perceived benefits (p<0.05).

Table 3) Correlation matrix of quality of life dimensions related to pender model structures

The results of regression analysis (Table 4) showed that the variables of perceived barriers, social support, positive and negative effect, and perceived benefits had significant effects on the physical dimension of HRQoL (p<0.05). Moreover, the variables of positive and negative affect, self-efficacy, and perceived benefits influenced the psychological dimension of HRQoL (Table 5).

Table 4) Evaluating the simultaneous effects of Pender's model components on the physical dimension of health-related quality of life in pregnant women

Table 5) Simultaneous effects of Pender's model components on the psychological dimension of health-related quality of life in pregnant women

Discussion

This research was conducted to investigate the predictors of HRQoL in pregnant women based on the Pender Health Promotion Model. In the present study, the mean physical dimension of HRQoL was higher than the mean of the psychological dimension of HRQoL in pregnant women, which is consistent with some studies [17, 18]. In these studies, pregnant women were aware of and sensitive to weight changes during pregnancy and had a coherent program of physical activity to prepare for childbirth and maintain fitness [19]. Other studies have shown that women do less physical activity during pregnancy due to physical problems and mental and psychological conditions [2, 20, 21]. Accordingly, women are advised to participate in moderate activity for 30 minutes or more on most days of the week to prevent medical or midwifery complications [18]. It may be argued that the low psychological dimension of HRQoL is related to women's mental and psychological changes during pregnancy. In fact, pregnant women are susceptible to a variety of tensions and can become more depressed and anxious than other women [22].

The score of psychological dimensions of Qol in pregnant women in this study was lower than the physical dimension. Therefore, it can be concluded that psychological measures and support, especially from the spouse and life, can help to improve the psychological dimension of QoL. Such improvement will enhance pregnant women's self-efficacy to understand better the problems and difficulties associated with pregnancy. Equally perceived effect and subsequently perceived benefits will change and ultimately affect the psychological health dimension of QoL [18]. Robinson argues that successful individuals have a high self-efficacy and thus a high QoL [23]. As a factor affecting the quality of life, self-efficacy emphasizes one's understanding of one's skills and ability to do a good job. In other words, self-efficacy affects understanding adaptive behaviors and functions and choosing the environment and conditions individuals strive to achieve [24].

Concerning the Pender Health Promotion Model constructs in pregnant women, the score of perceived benefits had the highest mean, suggesting that participants in the study had a high perception of the benefits of performing health-promoting behaviors. This result is not surprising given the participants' educational and occupational conditions and youth. The lowest score was related to perceived self-efficacy, referring to the participants' young age, inadequacy, and inexperience. There are no reliable articles to compare and analyze HRQoL in pregnant women based on the Pender model. However, Goodarzi et al. evaluated the effect of a nutrition education program on dietary pattern improvement during pregnancy. When performing Pender’s health promotion, the highest score was related to the behavioral construct of effect, while the lowest score was to the barriers to health promotion activities [25]. This inconsistency may be attributed to prim parous participant samples who are emotionally in better condition. In the present study, among the constructs of Pender's health promotion model, perceived self-efficacy had the lowest score. This result suggests that pregnant women may be in more doubt about their abilities in controlling and its consequences due to their pregnancy condition. Since the psychological dimension of QoL had the lowest score and self-efficacy was a factor affecting the psychological dimension of the present study, it is necessary to improve the psychological dimension of their QoL by interventions to increase self-efficacy in pregnant women [15, 25, 26].

Regarding the relationship between Pender’s Health Promotion Model constructs and HRQoL dimensions, a regression test in pregnant women showed that perceived self-efficacy constructs and perceived effects and benefits have the most effects on the psychological dimension of quality of life in pregnant women's pregnant women lives. Self-efficacy is people’s belief about their ability and capacity to perform a task or face life challenges. Women with high self-efficacy will have a better understanding of their abilities. Therefore, they are more likely to benefit from behaviors that lead to improved quality of life. As a result, their perceived effect and QoL will improve. The results of this study are in line with other studies [15, 27]. In the study of Bahabadi et al., constructs of self-efficacy and perceived effect had the highest predictive power of quality of life, respectively [5]. In the study of Han et al., perceived self-efficacy directly affects QoL's psychological and physical dimensions [28]. This result is consistent with the present study in terms of the effect of self-efficacy on the psychological dimension. Feelings of self-efficacy can affect the psychological dimension of QoL in pregnant women in the present study. In other words, the more pregnant women are confident in their ability to control health behaviors, the better the QoL they will have in the psychological dimension. Feelings of self-efficacy can affect all aspects of life, including psychological dimensions. Research has shown that people who are confident in their abilities are actively involved in health promotion programs and can effectively manage their life events [29]. Self-efficacy can also improve the psychological dimension of QoL through perceived affect. Therefore, further studies focusing on improving self-efficacy in pregnant women can promote a healthier lifestyle and a better and healthier QoL.

The regression test results showed that perceived barriers, social support, affect, and perceived benefits affect the physical dimension of QoL. Emmanuel et al. reported a significant impact of social support on QoL in pregnant women, especially the physical aspect of QoL [30], which is consistent with the present study. Family support, especially that from the spouse, enables women to have a more positive view of pregnancy, better understand the barriers to health behaviors, and focus more on the benefits of such behaviors. In the present study, pregnant women had relatively favorable emotions, which could directly influence perceived self-efficacy in health choices and quality of life. Using linear regression models to determine the relationship and type of relationship between variables is considered among the strengths of the present research. On the other hand, one of the disadvantages of this study is the limited sample size in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy due to the lack of accurate information regarding the first trimester of pregnancy. Therefore, further studies on QoL are recommended in early pregnancy samples.

Conclusion

According to the results, perceived effect, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived benefits constructs are suitable for the psychological dimension of HRQoL, perceived barrier constructs, and social support effects. The perceived benefits are appropriate for predicting the physical dimension of quality of life. Therefore, it is suggested to improve the QoL and enhance perceived self-efficacy in pregnant women by encouraging them to adopt health-promoting behaviors. To this end, studies and educational interventions emphasizing the Pender Health Promotion Model constructs are also recommended.

Acknowledgment: We would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for the financial support given toward this study.

Ethical Permission: The present study is the product of a research project approved by IR.SBMU.RETECH.1397.27of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest has been reported in this study.

Authors' Contribution: Rahimi Khalifeh Kandi Z (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (25%); Estebsari F (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Jalilibahabadi F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/

Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (15%); Sheikh Milani A (Forth author), Discussion Writer (15%); Estebsari K (Fifth author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Mostafaei D (Sixth authr), Introduction Writer/ Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Supports: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences support financial this study.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2021/08/28 | Accepted: 2021/10/29 | Published: 2022/06/14

Received: 2021/08/28 | Accepted: 2021/10/29 | Published: 2022/06/14

References

1. Chenary R, Noroozi A, Tahmasebi R. Health Promoting Behaviors in Veterans in Ilam Province. J Mil Med. 2013;15(1):95-102. [Persian] [Link]

2. Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Tavananezhad N, Karkhane M. Predictors of health-related quality of life in Iranian women of reproductive age. Appl Rese Qual Life. 2015;11(3):723-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11482-015-9392-0]

3. Lashani F, et al. Exploring the relationship between sexual function, sense of coherence, well-being in a sample of Iranian breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2020;29(6):3191-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-020-05831-0]

4. Raisi Filabadi Z, Estebsari F, Sheikh Milani A, Feizi Sh, Nasiri M. Relationship between electronic health literacy, quality of life, self-efficacy in Tehran, Iran: a community-based study. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:175. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_63_20]

5. Jalili Bahabadi F, Estebsari F, Rohani C, Rahimi Khalifeh Kandi Z, Sefidkar R, Mostafaei D. Predictors of health-promoting lifestyle in pregnant women based on Pender's health promotion model. Int J Women Health. 2020;12:71-7. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/IJWH.S235169]

6. Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, quality of life: What is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9]

7. Abedi P, Jorfi M, Afshari P. Evaluation of the health promotion lifestyle and its related factors in reproductive aged women in Ahvaz, Iran. Commun Health J. 2015;9(1):68-74. [Persian] [Link]

8. Harvey T, Zkik A, Auges M, Clavel T. Assessment of iron deficiency and anemia in pregnant women: an observational French study. Women Health. 2016;12(1):95-102. [Link] [DOI:10.2217/whe.15.91]

9. Abbaspoor Z, Sarparast Razmju P, Hekmat Kh. Relation between quality of life and mental health in pregnant women with prior pregnancy loss. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(10):1290-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jog.13061]

10. Oviedo Caro MA, Bueno-Antequera J, Munguía-Izquierdo D. Explanatory factors and levels of health-related quality of life among healthy pregnant women at midpregnancy: a cross-sectional study of the pregnactive project. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(12):2766-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jan.13787]

11. Yilmaz E, Soysal C, Icer B. The impact of iron deficiency anemia on health related quality of life in the last trimester of pregnancy. EJMI. 2019;3(3):182-8. [Turkish] [Link] [DOI:10.14744/ejmi.2019.65035]

12. Lu HX, Xu W, Wong MCM, Wei TY, Feng XP. Impact of periodontal conditions on the quality of life of pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:67. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12955-015-0267-8]

13. Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Asadi-Lari M, Omidvari S, Tavousi M. The 12-item medical outcomes study short form health survey version 2.0 (SF-12v2): A population-based validation study from Tehran, Iran. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:12. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-9-12]

14. Pashaie S, Estebsari F, Matbouei M, Nasiri M. Evaluation of the effect of patient education on the quality of life cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: a review article. J Pharmaceut Res Int. 2019:31(5):1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.9734/jpri/2019/v31i530309]

15. Mohamadian H, Eftekhar Ardebili H, Rahimi Foroushani A, Taghdisi M, Shojaiezade D. Evaluation of Pender's health promotion model for predicting adolescent girls' quality of life. J Sch Public Health Instit Public Health Res. 2011;8(4):1-13. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00591.x]

16. Mohamadian H, Eftekhar H, Rahimi A, Taghdisi Mohamad H, Shojaiezade D, Montazeri A. Predicting health-related quality of life by using a health promotion model among Iranian adolescent girls: a structural equation modeling approach. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(2):141-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00591.x]

17. Kolu P, Raitanen J, Luoto R. Physical activity and health-related quality of life during pregnancy: a secondary analysis of a cluster-randomised trial. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(9):2098-105. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10995-014-1457-4]

18. Krzepota J, Sadowska D, Biernat E. Relationships between physical activity and quality of life in pregnant women in the second and third trimester. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2745. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15122745]

19. Marshall ES, Bland H, Melton B. Perceived barriers to physical activity among pregnant women living in a rural community. Public Health Nurs. 2013;30(4):361-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/phn.12006]

20. Attard CL, Kohli MA, Coleman S, Bradley C, Hux M, Atanackovic G, et al. The burden of illness of severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl Understanding):S220-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1067/mob.2002.122605]

21. Lawan A, Awotidebe AW, Oyeyemi AL, Rufa'i AA, Oyeyemi AY. Relationship between physical activity and health related quality of life among pregnant women. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018;22(3):80-9. [Link]

22. Tendais I, Figueiredo B, Mota J, Conde A. Physical activity, health-related quality of life and depression during pregnancy. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(2):219-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0102-311X2011000200003]

23. Robinson-Smith G, Johnston MV, Allen J. Self-care self-efficacy, quality of life, depression after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(4):460-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1053/mr.2000.3863]

24. Guszkowska M, Langwald M, Zaremba A, Dudziak D. The correlates of mental health of well-educated Polish women in the first pregnancy. J Ment Health. 2014;23(6):328-32. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/09638237.2014.971144]

25. Goodarzi-Khoigani M, Baghiani Moghadam MH, Nadjarzadeh A, Mardanian F, Fallahzadeh H, Mazloomy-Mahmoodabad SS. Impact of nutrition education in improving dietary pattern during pregnancy based on pender's health promotion model: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2018;23(1):18-25. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_198_16]

26. Heydari A, Khorashadizadeh F. Pender's health promotion model in medical research. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64(9):1067-74. [Link]

27. Mohamadi zeidi I, Alijanzadeh M, Pakpour Hajiagha A. Factors predicting oral health-related behaviors in diabetic patients using Pender's oral health promotion model. J Isfahan Dent Sch. 2016;12(2):183-98. [Persian] [Link]

28. Han KS, Lee SJ, Park ES, Park YJ, Cheol KH. Structural model for quality of life of patients with chronic cardiovascular disease in Korea. Nurs Res. 2005;54(2):85-96. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00006199-200503000-00003]

29. Jones F, Riazi A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(10):797-810. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2010.511415]

30. Emmanuel E, St John W, Sun J. Relationship between social support and quality of life in childbearing women during the perinatal period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonat Nurs. 2012;41(6):E62-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01400.x]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |