BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47956-en.html

2- Educational Sciences Department, Humanities Faculty, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran

Introduction

Positive adaptation to the environment, adaptation to the changing stimuli, positive reconstruction of the intellectual framework, multidimensional consideration to issues, ability to select the most desirable option from the multiplicity of options, answering the question “what if”, changing the atmosphere based on change in variables and goals, purposeful and multidimensional consideration to issues and ability to understand the concepts from a new point of view need the contribution of cognitive functions and executive functions such as cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition in childhood and preschool age [1, 2]. Childhood is a critical period for different parts and networks of the brain, including the frontal lobe, which encompasses a range of complex skills such as cognitive flexibility, inhibitor control, and proactive inhibition. The development of the frontal lobe and the period of this process simultaneously with the period and development of cognitive skills and vice versa becomes possible [3].

Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to change cognitive sets to adapt to the changing stimuli, which can adapt one's thinking and behavior in response to the changes of environmental conditions and can be one of the important factors in social interaction and explains it as mental ability to control what one thinks about, how one thinks about it, and change of his/her mind about it [4]. In other words, it is defined as a dynamic process that is responsible for one's positive adaptation to the environment, in that the flexible person, despite different or traumatic experiences, can be adapted to the changing environmental stimuli [4-6]. Moreover, cognitive flexibility should be considered a higher-level cognitive skill that contributes to stimulating goal-centered behavior and changes one's ability to regulate his/her behavior according to the environment. This function as a requirement for dealing with new and unexpected situations in the environment is associated with adapting with mental strategies. It enables people to view any problem or issue from several perspectives, helping them change the environment's situational changes effectively [7]. However, from a neuroscience perspective, cognitive flexibility is a term used to describe the brain processes that are the basis of the phenomenon of the adapted change in behavior in response to the probable changes in the internal or external environment [8].

Jay Spiro's cognitive flexibility theory is focused on learning in complex and non-structured areas and considers a learner with cognitive flexibility as a person who can reorganize and apply his/her knowledge in response to various situational demands. To attain cognitive flexibility, the learners need to understand the complexity of the issue and examine the context of the issue frequently to find out how a change in variables and goals can change the context. One's ability reflects the representation of knowledge and the processes operating on those mental representations [9]. According to Andrade and Coutinho, cognitive flexibility theory attempts to determine how the human mind can manage knowledge and reconstruct the existing database based on newly received information [10].

Cognitive flexibility is associated with various processes leading to modification of behaviors in accordance with the probable changes to these stimuli, responses, and the related consequences [11]. Those who enjoyed such a function prefer valuable long-term goals to worthless short-term goals and improve their desirable function of decision-making [12]. They have flexible and various ways to achieve their goals, perform adjustment, approval, and implementation of strategic behaviors in accordance with planning or thinking, are multi-faceted and purposeful in dealing with problems, are purposeful, goal-oriented, and provident in life, and can manage cognitive functions and regulate behavior to achieve their goals. All lead to the hidden and self-correcting organization of all functional aspects in these people. Cognitive flexibility, on the other hand, contains elements such as inhibitor control (the ability of competitive, dominant, and automated suppress of cognitive processing) [13], impulse control (control and resistance against impulses), mental set (not being restricted to solve the set of problems) [14], proactive inhibition or stopping thinking, emotions and acts, which helps children to respond with hesitation [15, 16], and interference-control (one's ability to stop a behavior at a time), which involves stopping actions and thinking [17].

Proactive inhibition is the ability to delay an action or a cognitive process, the ability to stop ongoing behavior in an inappropriate situation [18], the ability to assess position and behavior before reacting [19], automate ability and tendency in a specific situation, and an indicator of “how” and “when” to perform normal behavioral functions [20]. It helps people plan goals, self-regulation, inhibiting inappropriate responses, flexibility, and future-oriented behavior [21]. In other words, proactive inhibition is one's ability to stop the behavior at a time, which involves stopping the person's action and thoughts [17]. It also refers to stopping an automated model stimulus or model stimulus that requires interference control, emotional control, and motor control. Dominant proactive inhibition is a process that prevents producing robust and explicit responses that are irrelevant to tasks [22]. It includes three actions: stopping irrelevant information in working memory, dominant proactive inhibition, and interference control [23].

Cognitive neuroscience studies show that prefrontal areas of the brain responsible for inhibitory control become activated in the production of ideas [24]. When the mind inhibits a perceptual process to activate a process of logical reasoning, a significant change appears in the brain anatomy from the posterior part of the brain (abdominal and dorsal ways) to a left forehead grid, including the middle cerebral cortex, anterior insular of Broca area [25].

Any brain injury in early childhood (5-6 years old) led these people to have deeper deficits in the component of inhibition or proactive inhibition over time, as compared to older age groups [26]. The results showed that both the middle cerebral cortexes and the parietal segment were involved in both inhibition and substitution. However, the middle region of the frontal lobe was more active for the component of inhibition, and the inferior parietal region was active for changing processing [27]. In other words right inferior frontal cortex (IFC), or more precisely the posterior part of the inferior frontal gyrus and the surrounding regions related to the executive function of proactive inhibition in the brain [28]. Inhibition is a mechanism in which PFC affects subcortical and posterior areas to implement cognitive control [29].

The children with poor proactive inhibition often act inappropriately without considering time and without thinking. In contrast, strong proactive inhibition allows the person to wait before acting and think about different aspects of the actions and their consequences [30]. The absence of inhibition ability results in difficult planning and purposeful targeting. The ability of proactive inhibition allows us to stop or delay response to manage behavior or influence others [3]. Proactive inhibition or the ability to think before acting to resist the tendency to express something or doing an action allows us to evaluate the possible effect of our behavior. Moreover, inhibition is one's ability to stop his/her behavior at a time, including stopping one's actions and thoughts [17].

Philosophy for children is an educational and applied method of philosophy in education, in which philosophy is used to stimulate the child's mind to strive to respond to the need and the derivation it has in meaning [31]. This program is different from the programs of applied philosophy; this program asks the students to do intellectual works and solve problems [32]. Philosophizing is an attempt for children to develop the meaning of philosophy. It is targeted to teach philosophy in the form of an educational method, reasoning, and logical judgment in the form of philosophy because the ability of reason, judgment, and distinction is undeniably important in individual and social life or collective life and fosters and reinforces skills such as the spirit of justice, accountability, kindness, involvement and counseling, foresight, critical thinking, and ethical understanding [33]. Philosophy for children (P4C) is an educational approach to the dynamic activity of finding meaning in students or the experience of facing the most important questions and mental challenges, which turns children into thoughtful, more flexible, more considerate, and more logical human beings [34-36]. Besides, it fosters thinking, reasoning, and improving learning through criticism and correction, critical spirit, citizenship, the spirit of dialogue, discovery, and inquiry and judgment [37, 38].

Various studies have investigated the effectiveness of philosophizing (philosophy for children) on cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition. It has been proved that training courses of the educational program of philosophy for children are effective on the variable of cognitive flexibility [39] because the environmental and/or cultural effects were important in understanding the development of neural structures that are responsible for high-level mental abilities such as executive functions [40-43]. The inability to utilize educational programs in dialectics makes children weaker in proactive inhibition than their peers [44]. As can be seen from the literature review, in most research, the use of the philosophical program is used to improve the components of cognitive functions in individuals, especially children, and no research of cognitive functions is used to formulate a comprehensive program. It does not include almost all the components of cognitive functions. Therefore, the present study aimed at the training program of philosophizing and investigating its effects on cognitive flexibility as executive function and proactive inhibition in preschool children.

Materials & Methods

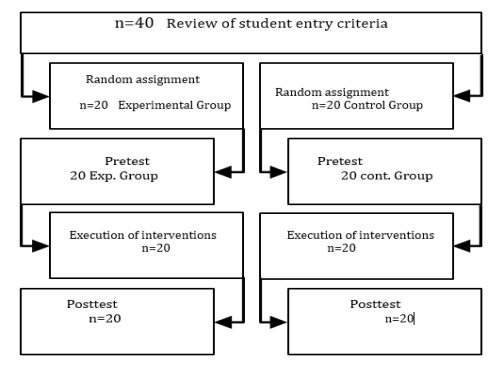

The present study is a semi-experimental method, in which children at the age of preschool were investigated using an experimental method using pretest posttest design with a control group, considering the studied variables.

Diagram 1) Consort of Clinical Trial Research

The statistical population consisted of all preschool children in preschools centers in Mashhad. Forty subjects were selected by the two-stage cluster random sampling method and were randomly divided into two experimental and control groups. The training program of philosophizing was designed, and the children in the experimental group participated in a 20-session program (each for 25 minutes). The children in the control group received no training (Diagram 1).

Two tools were used in this study to collect data:

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST): The WCST is considered the most known, principal, and applied tool in neuropsychological standard tests. This tool is useful in studying cognitive deficits after brain injury and is regarded as a tool to measure cognitive flexibility. This test has 64 identical variable cards. There are four forms of triangles, stars, crosses, or circles in four colors of red, yellow, green, and blue. The number of figures on each card varies from 1 to 4. Therefore, the test has three principals: form (four types), figures (1 to 4), and color (four colors), with 64 possible outcomes. In this test, the participant should deduce the pattern of the original four cards, considering wrong or right feedback s/he received after each response, and place the other cards under the original cards based on this pattern [45]. The participant should keep the concept or the rule received in a stage of the test in the consequent stages and changed the previous concept when the rules of storage are changed. The Wisconsin card storing test has six subscales of correct categories, omission, other errors, total error, number of classes, and time duration. This test can be scored in various ways. The most common way is scoring the error scores of omissions. According to specified criteria, this simple system consists of determining the model of the class on the left side of the Table, recording the subject's performance in the next column, error or omission, other error and total error in the subsequent columns, and subject's performance with a short line mark for each correct storing (in groups of five). The lowercase letters of each class (N, F, C) are used to show each incorrect storing, and CF and CN are used when the incorrect storing affects two incorrect classes. The * mark is used when none of the classes are in harmony with the storage. For example, when the subject placed the card with three blue circles under the card with two green stars. When a class is completed with ten correct responses, that is, when two sets of five short lines are drawn, recording the results is started in the next column. The present study used the Wisconsin Card Storing Test with 64 cards for children at preschool age. The reliability reported in the abroad sample was reported as 0.86, and its reliability in the Iranian sample was 0.85 [46]. The inter-score and in-score reliability were 0.94 [46].

Stroop Test: this test is the most important and common, and applied test to measure proactive inhibition. Stroop test can measure accuracy

(number of correct responses). The fruit Stroop test includes three parts, and each part consists of two tests, with a total of 6 tests. In these six tests, pictures of fruits and geometric figures are presented in separate sheets. In six tests, the participant is presented with melon, banana, and strawberry in three forms (stripped, canonical colors, and superficial colors). In front, there are three colored rectangles (red, yellow, green), and the participant is asked to choose the colors associated with fruits or figures among the colors, names, or codes of the colored rectangles.

In test 1, three drawings are not colored. Melons, bananas, and strawberries are presented one by one, requiring participants to choose from three colored rectangles.

In test 2, three fruits in their uncanonical colors are presented, and the participant is asked to determine the canonical color of each fruit, and hence, s/he has to inhibit the response to the superficial color of the fruit to respond correctly.

In test 3, three rectangle figures, circle, and triangle are presented in three different colors, and the participants choose the figure with the same color.

In test 4, the fruits are presented with the same color as in the previous test, and the subject is asked to choose the real color of each despite the superficial color of the fruits. For example, the banana is presented in green, melon in red, and strawberry in yellow. However, the participant must choose the right colors, requiring the participant to inhibit the response to the superficial color of the fruit to respond correctly.

In test 5, the fruits are presented in a stripped and colorless form, and the participant is asked to express the name of each fruit, which is coded in this study or identify in rectangles in front of each fruit.

In test 6, the fruits are presented in their uncanonical colors; for example, melon in yellow, banana in red, and strawberry in green. The name of fruits is specified in codes and oral form, requiring the participant to inhibit the color of fruits. In this test, the parameters of facilitation score or the number of correct responses, the number of error, the time of interference stage (tests 2, 4, and 6), and the time of control stage (tests 1, 3, and 5) are separate from each other, and the interference score or the subtract of the implementation duration of interference stage from the duration of control stage [13].

Scoring: If the participant chooses the correct colored rectangle associated with the fruit or figure in accordance with the rules, s/he is scored one, and if s/he performs each of the six tests correctly, s/he is scored three because each test is scored at the range of 0 to 3. Correct and complete responses in the control or interference stages bring nine scores for the participant; incorrect responses or leaving

the test with no answer is scored 0 in any two stages. In other words, each stage (control or interference) is scored between 0 and 9. At the time of starting the test, each of the time duration of the two stages is measured to calculate the interference score by subtracting the score of the interference stage from the score of the control stage [13].

The studies on the Stroop test have indicated good validity and reliability of this test in measuring interference and proactive inhibition. The validity of this test was obtained as 0.89 and 0.87 using the retest method in a range between 0.72 and 0.85, and the reliability was reported for both stages as 1.0 and 0.9, respectively, in a range of 0.80 to 0.91 [47, 48]. In Iran, the validity of this test is acceptable (0.79) [49]. The external reliability of this test is 0.92, and its internal reliability was reported as 0.94 [47, 50]. It was reported as 0.60, 0.55, and 0.83, respectively for the stages 1 to 3, for stages of 3 to 6 as 0.78, 0.97, and 0.79, respectively [51].

Intervention program: Lipman, in 1969, wrote his first book on philosophy for children and then new stories for various educational levels in the form of storybooks and teacher's guide, indicating that the educational contents or courses should be presented in the form of stories with philosophical and intellectual themes and raise basic questions for children by following the procedures and sequences [52, 53]. In other words, the nature of literature, story, and its role in the program of philosophizing is the question, and it is planned to use world old or new rich stories with philosophical themes as the content of the program of philosophy. In this context, the opportunity to understand the philosophical aspects of literature is provided for children, and, besides, it paves the way to foster their philosophical thought.

According to Vygotsky's contemplative-cultural approach, the philosophical and literary themes of the fictional content of the program of philosophy for children must be drawn from children's cultural context and social life in order to encourage them to empathize with the characters and themes and stimulate their thinking. Considering the issues on choosing good stories (old or new fictional texts with philosophical themes), stories such as Pond, Fisherman, and Three Fish from MasnaviMa'navi, The Crab that Had a House on Top of a Tree from Kalilah and Demnah, Truth and The Wise Man from a book of the same title and the story of Ant and Teimur from One Hundred Subjects were selected from old rich literature of Iran and stories such as The Miller, Boy, and His Donkey, The Memory of Un Jelma, the stories of Spider from The First Stories for Thinking and the story of Galert from Philosophizing with Mullah Nasruddin was selected from the new rich literature of the world. The questions and assignments were defined and determined based on the following two strategies:

1. Considering children's features associated with cognitive flexibility and functions.

2. Considering the inquiry loop to design the stages; a reflection on the story, a reflection on thinking, a reflection on executive functions, the questions while inquiring, and additional activities.

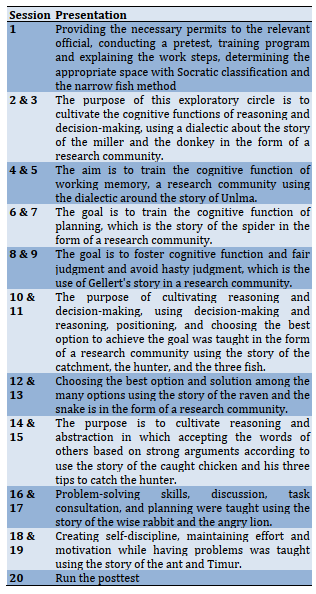

Finally, this designed intervention program was used to investigate the effectiveness of philosophizing on cognitive flexibility and cognitive functions (Table 1).

Table 1) The educational program of philosophizing frame

Findings

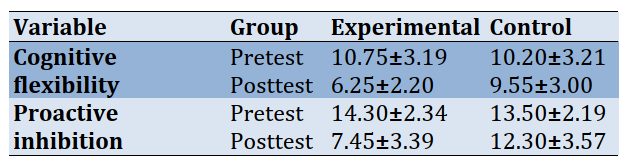

In this part, first, the mean and standard deviation of the experimental and control groups and then the results of the covariance analysis test to examine the difference between the groups were presented.

The results of Table 2 showed that the score means

of cognitive flexibility in posttest of the experimental group (9.55) decreased in comparison to pretest (6.25); however, there was no significant difference in the score means of the control group in pretest (10.75) and posttest (10.20), indicating the effectiveness of training philosophizing on children's cognitive flexibility at the preschool age. On the other hand, the score means of executive function of proactive inhibition in posttest (7.45) of the experimental group decreased rather than their score mean of pretest (12.30), but there could be found no significant difference in the score means of the control group in pretest (14.30) and posttest (13.50).

Table 2) Mean±SD of scores of the experimental and control groups (pretest and posttest) in the variables of cognitive flexibility and executive function of proactive inhibition (N=40)

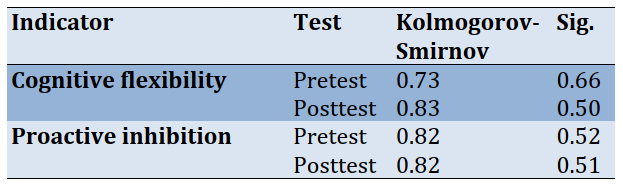

According to Table 3, since the significance level of all variables is higher than 0.05, it can be said that the data is normally distributed, and hence, parametric statistics are used.

Table 3) Data normality test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) of the experimental and control groups (pretest and posttest) in the variables of cognitive flexibility and executive function of proactive inhibition (N=40)

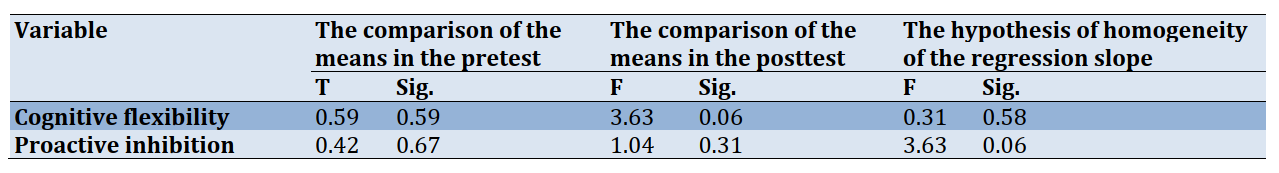

To investigate the research hypotheses (training philosophizing on cognitive flexibility of children at the age of preschool and training philosophizing on inhibition response of children at the age of preschool) Independent t-test was used to check the similarity of the two groups' baseline. Also, the Levin f-test was used to test the hypothesis of homogeneity of variances, and the f-test was used to test the hypothesis of homogeneity of regression coefficients. Results of covariance analysis were investigated after examining the covariance hypotheses.

According to Table 4, the results of independent T are not significant for cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition. Therefore, the two groups are the same at the baseline. In addition, the significance level in the Levin test was greater than 0.05, and hence, the hypothesis of homogeneity of variances between the two experimental and control groups is also met. According to the results of this Table, the test for the homogeneity of regression coefficients of cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition was not significant. Therefore, assuming the homogeneity of the regression coefficients, covariance analysis was performed.

The results of Table 5 showed that the effect of pretest was significant; that is, the implementation of pretest was effective on the scores of posttest (F37, 1 59.56, p<0.01). However, there was a significant difference between the cognitive flexibility of the subjects in two experimental and control groups (F37, 1=48.73, p<0.01). With 99% confidence, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the opposite hypothesis is confirmed, showing the effectiveness of training philosophizing on cognitive flexibility in children at the age of preschool. The rate of these changes, according to eta square (effect rate), was 57%. Moreover, the effect of pretest was not significant in the variable of proactive inhibition. It means that the implementation of pretest was not effective on the scores of posttest (F37, 1=10.07, p>0.01), but there was a significant difference between the rate of proactive inhibition in two experimental and control groups (F37, 1=44.04, p<0.01). With 99% confidence, the null hypothesis was rejected, and the opposite hypothesis was confirmed, indicating the effectiveness of philosophizing on the abstract conceptualization of children at the preschool age. According to the eta square (effect rate), the effective rate of these changes was 54%.

Table 4) The comparison of the experimental and control groups at the baseline.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of philosophy for preschool children (P4C) on their cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition. Results showed that the training program of philosophizing could be an important factor in promoting the level of cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition of preschool children and make them understand the concepts in a new and different way. The results of this research are consistent with the researches conducted by Brahman and Khodabakhshi Sadeghabadi [32], Seifi Gandmani et al. [36], and Rezaei et al. [39]. Philosophy for children is the greatest step taken to apply philosophy and practically teach critical thinking to strengthen and enhance reasoning, judgment, and pure power. This program is a clear example of the application of philosophy in education, but it is slightly different from other applied philosophy programs, which is that this program wants to help students do their intellectual work and solve problems themselves. The overall goal of the Philosophy for Children program is to create a philosophical discussion by creating a research community at the classroom level. In addition to mentioning several pieces of research in this field, we concluded that teaching philosophy to children is feasible and necessary, and it is suggested that it be considered one of the compulsory curricula for students [32]. The study conducted by Seifi Gandmani et al. showed that the program significantly increased the self-esteem of the experimental group and, on the other hand, led to a significant increase in the use of problem-solving problem-solving and a significant decrease in emotion-oriented style. This program can be effective in improving students' cognitive and social skills. The purpose of the philosophy education program for children is to become like its creators [36]. A study by Rezaei et al. [39]. By teaching philosophy to children, students' creativity can be increased.

According to the present study findings, it can be said that since preschool is the preliminary period to enter a larger educational and social environment, children are in dire need of adjustment. Because adjustment or answering the question “what if” reflects several possible perspectives of the future, the power of the perspectives, presenting several new scenarios, injecting new inventions, challenging the previous information and replacing it with the new information, and manipulating information in accordance with limitations, and achieving a special goal. Therefore, since multidimensional reflective and significant views and multiple thoughts in excellent levels and deep thinking rather than imposing thoughts are dominant in children [49], the training program of philosophizing can be an important factor in improving the cognitive flexibility in children. Moreover, this training program can cause a change in cognitive sets to adapt to changing stimuli and positive adaptation to the environment so that the flexible person can adapt to the changing stimuli in the environment despite different experiences that may be traumatic [5 6]. Philosophizing increases cognitive flexibility, and its mediating factor can be considered to be creating meaningful experiences. If children are helped to investigate the association between the whole and the components with their experiences, understand different aspects of an issue, consider the details as much as possible, evaluate the flexibility degree of the existing reasons on beliefs, and consider generality and situation to understand the meaning of separate experiences as a whole, they can foster cognitive flexibility.

Another result of this study was increased proactive inhibition in the training program of philosophizing in preschool children. Proactive inhibition includes the ability to plan activities and think to choose the best solution for leading problem-solving. Proactive inhibition allows the individual to wait before acting and think about different aspects and consequences [29]. According to Barclay, thinking and acting purposefully is impossible without dominant proactive inhibition. This result is consistent with that found by Mouzuni et al. [44], Yang et al. [54], Karest and Van Hack [55], and Zorufi [56]. Explaining this finding, it can be said that controlling thoughts and actions, distraction, and temptation in dealing with problems, inability in controlling impulses, impulsive behaviors, impaired self-regulation, having problem in making the behaviors purposeful, and responding to questions abruptly or in an appropriate time or interrupting others can be mentioned as problems children have in educational and research communities. Since the executive program of philosophizing paves the way for automated response to think about different aspects (thesis and antithesis) and its consequences and choose the most desirable option, this program can play an important role in improving the cognitive function of proactive inhibition in children. Moreover, this program can cause the ability to respond with hesitation in doing an action, foster the ability to think, prevent powerful responses and evident but irrelevant to the task, describe an indicator of “how” and “when” to do behavioral functions, help people to plan goals, self-regulation, inhibit inappropriate responses, flexibility and futuristic behavior, inhibitor control and controlling impulses as well as the ability and automate tendency in a special situation in a cognitive process [18].

Philosophizing increases the cognitive function of proactive inhibition, and its mediating factor is private speech and self-control. The concept of reflection is the cognition one attains through deliberate and purposeful thinking about what s/he has experienced, learned, interacted, and understood, and then forms self through integrating new achievements and previous cognitive structure, including ideas, activities, and abilities. This process is formed through private speech, i.e., speaking with self. Since reflection is rethinking or thinking deeply about something, private speech can be an introduction to self-control. Self-control skill is defined as an organism, and it is believed that it is the cognitive context of proactive inhibition [57]. In other words, the ability of dominant proactive inhibition needs self-control, and self-control needs private speech that, over time, facilitates the development of rules of problem-solving strategies, self-regulation, self-learning, and metacognition [3]. Proactive inhibition is a requirement for self-regulation because one response automatically to an immediate event; s/he cannot guide direct actions or behaviors towards self.

Considering the mentioned issues, it can be said that the training program of philosophizing essentially contains high-level skills of thinking and dialogue, reflective and meaningful multidimensional view, and multiple thoughts in a high level and deep thinking rather than imposing thoughts and provides a delay in automatic response to pave the way to think about its different aspects (thesis and antithesis) and consequences and choose the most appropriate option (synthesis). Therefore, according to the results, the training program of philosophizing was effective on executive functions of cognitive flexibility and proactive inhibition.

One of the limitations of the present study was little research inside and outside the country on the issue under study, which restricted the comparison of findings. Since this study was conducted in preschools in Mashhad, it is suggested to conduct similar research on a larger scale to extend the generalization of the results. Moreover, it is recommended to use meaningful experiences to foster adaptability in preschoolers, as well as dialectics and private speech to increase self-control and proactive inhibition based on the training program of philosophizing, the organization for textbooks, the books on philosophy for children (focused on challenging questions and pictures stimulating surprise) and its teacher's guide for the two-year preschool course. In addition, it is also desirable to apply the experiences of concepts in social action to make mental tools and develop cognitive functions of mind in children at preschool age.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that philosophizing increases cognitive flexibility in preschool children. So if we help children explore the connection between the whole and the part with their experiences to understand the different aspects of a problem or issues, they can assess the flexibility of the existing reasons for beliefs and consider the degree of comprehensiveness and position. To understand the meaning of separate and scattered experiences in a way that makes these experiences meaningful to them and gives rise to cognitive flexibility. Therefore, the philosophy training program can be an important factor in improving the level of cognitive flexibility and selective attention. This training program makes a child ignore disturbing factors and stimuli and focus on the main stimulus. Therefore, by achieving the goals of philosophizing in preschool education, children's learning and development can be improved.

Acknowledgments: This research was performed according to the cooperation of Children and Adolescent Intellectual Development Centers in Mashhad and the financial support from the Cognitive Sciences and Technologies Council. Gratitude to the centers for their support and coordination.

Ethical Permissions: All ethical principles were considered in this research. The research extracted from the clinical trial as MSc dissertation of educational psychology in Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University (Ref.no.2619180).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Hamidi F. (First author), Introduction author/Methodologist/Assistant/Statistical analyst/Discussion author (50%); Otoufati Roudi M. (Second author), Methodologist/Original researcher/

Statistical analyst/Discussion author (50%).

Funding/Sources: The study gets financial support from the Cognitive Sciences and Technologies Council.

Received: 2020/11/27 | Accepted: 2020/12/24 | Published: 2021/05/5

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |