Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 163-169 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Raiisi F. Psychometric Characteristics of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :163-169

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-80193-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-80193-en.html

Department of Language, Institute of Cognitive Science Studies, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 719 kb]

(192 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (248 Views)

Full-Text: (47 Views)

Introduction

Health literacy is recognized as an important and vital indicator of healthcare outcomes and costs [1]. In other words, healthcare systems require high levels of health literacy [2]. Health literacy is widely considered a determinant of the health status of society and a priority in the agenda of public health policies [3]. It is defined as a broad range of values and skills related to acquiring, processing, understanding, and using health information [4]. Health literacy empowers people to play an active role in changing environments that affect health [5]. Therefore, the concept of health literacy reflects not only individual responsibility but also a cognitive challenge to increase awareness [6]. Since one of the missions of health literacy is to create mental and cognitive changes in people’s minds, conceptual metaphors can promote this goal [7]. Many concepts related to health, such as quality of life [8] and pain [9, 10], are also redefined through metaphors.

The conceptual metaphors proposed by Lakoff and Johnson [11] form the foundation of our cognitive system. Therefore, every conceptual metaphor consists of two components or domains: source and target domains [12]. The source domain is based on bodily characteristics and is entirely material and experiential [13]. Thus, the source domain is considered to be embodied; in other words, it follows physical or bodily characteristics [14]. The target domain is an abstract and immaterial field identified by the source domain. This phenomenon is referred to as mapping or metaphorical implications [15]. Conceptual metaphors can serve as tools for enhancing health literacy [16]. Most concepts in the field of health literacy are metaphorical; in other words, many concepts related to health are understood through conceptual metaphors [17]. Understanding these conceptual metaphors in the field of health is also linked to cognitive and metaphorical development [18].

A study found that viewing health literacy from a metaphorical perspective improves health-related activities [19]. Metaphorical messages can highlight the dangers associated with maintaining health and can be practically effective in promoting the health level of society [20]. Conceptual metaphors can facilitate social care, communication, and health promotion [21]. One study indicated that conceptual metaphors can be applied to health literacy knowledge, literacy services, literacy strategies, and literacy interventions [22]. An analysis of a qualitative study involving patients demonstrated how similar metaphors can be utilized in ways that are both empowering and disabling in the health domain, as patients attempt to come to terms with their health and illness through metaphors [23]. The use of metaphor in health discourse is effective. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the metaphor of a “war” against the virus was introduced, employing military language to describe the fight against disease and the maintenance of health. Conversely, this military language conveys the need for strict discipline and high-level management to ensure health [24].

Based on our search, there is no independent questionnaire available in the research literature that can measure metaphorical health literacy. Most tools for measuring health literacy are general and specifically focused on the health field, such as the health literacy questionnaire designed for the urban population of Iran [25]. This questionnaire was developed with a sample of 366 individuals aged 18 to 65 living in various districts of Tehran and was tailored to the cultural and social characteristics of Iran. It has construct validity through exploratory factor analysis and reliability assessed by calculating the internal correlation coefficient. The questionnaire includes subscales for access, reading skills, comprehension, evaluation, decision-making, and behavior. Another scale is the Electronic Health Literacy Questionnaire [26]. This questionnaire was administered to 525 young people and consisted of ten items. In this questionnaire, criterion validity was examined by applying Pearson correlations between the measured constructs as well as a computer literacy questionnaire. The internal consistency of the scale was sufficient (alpha=0.88), and the test-retest coefficients for the items were reliable (r=0.96).

The importance of conceptual metaphors in the field of health becomes clear when the transmission and understanding of health messages are considered essential [27]. Conceptual metaphors and their significance in health have recently entered interdisciplinary studies [28]. Metaphors and figurative language have been utilized in the fields of health, healthcare, and social care to aid communication with patients, visualize illness, conceptualize illness and embodiment, and inform health education experiences and related concepts. From another perspective, although common health literacy questionnaires use conceptual metaphors to understand health concepts, they are not specifically metaphorical. As mentioned, learning and comprehending health-related concepts is facilitated by metaphors. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the health field from various perspectives, particularly verbal-cognitive, to enhance the understanding of health concepts, especially during critical times (such as epidemics of infectious diseases or emergencies). In foreign literature, few items address health literacy in the form of health tools. These tools often contain scattered items or lack comprehensive psychometric evaluation. For these reasons, it is evident that due to the absence of metaphorical tools in both domestic and foreign research literature, it is appropriate to design and evaluate a psychometrically valid tool in the field of metaphorical health literacy. Hence, the purpose of this study was to design, construct, and examine the psychometric characteristics of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire in the Persian language.

Instrument and Methods

Design and participants

This descriptive research involved both survey and psychometric studies and was conducted in Tehran, in 2024. The steps for preparing the metaphorical health literacy questionnaire were carried out in several stages. In the first step, based on Lakoff’s conceptual metaphor theory and Raiisi’s qualitative-cognitive study [22], the source domains for health literacy metaphors in the Persian language were identified, including the source domains of object, force, human, and product. In the second step, four main areas were identified through text mining, including knowledge, services, strategies, and interventions. To begin the assessment of psychometric properties, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine the main factor structure. As a result, the main factor structure was established, and items with insufficient loadings were removed. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis was employed to assess the coherence between the data and the construct.

Phase 1: Item designing

A qualitative study was conducted to construct the scale. From a review of 200 health articles, four areas—knowledge, services, strategies, and interventions—were identified through text mining. For each of these areas, five items were designed based on the identified health literacy metaphor source domains from Raiisi’s study in the Persian language [22]. Subsequently, an independent sample of 40 health students was selected based on Cochran's formula and asked to respond to the items. The entry criteria for health students included being an undergraduate student, being between the ages of 18 and 24, and being enrolled at one of the public or private universities in Tehran. The exclusion criterion was a refusal to complete the questionnaire. The average age of these students was 21.85, with a standard deviation of 2.24. They were asked to evaluate the relevance, clarity, and meaningfulness of the questionnaire items. The researcher requested that they write down any personal opinions or suggestions for improving the items next to each question. At this stage, the researcher addressed all of the students’ questions and ambiguities regarding the items and noted their feedback. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was analyzed using SPSS 26 software. After the item analysis, five items were removed due to a lack of clarity for the health students.

Content Validity: In the next step, for content validity, the Delphi survey technique was employed. Ten experts from relevant fields expressed their opinions on the questionnaire items using the Waltz & Bausell method and formula [29]. Specifically, three cognitive linguists, two health psychologists, two health experts, two physicians, and one psychometric expert reviewed the questionnaire. They provided feedback on the clarity, relevance, and necessity of each item. The minimum acceptable value for the content validity index was set at 0.79. According to the experts, all the items were deemed appropriate, necessary, and relevant; therefore, no items were deleted or replaced. Finally, the content validity index for the 15 items was calculated and accepted.

Phase 2: Tool production, participants, and implementation

Tool Production and Participants: After establishing content validity, a 15-item Likert-type questionnaire was prepared. The scoring method ranged from five (strongly agree) to one (strongly disagree). The minimum score obtainable from the entire questionnaire is 15, while the maximum score is 75. To assess reliability, 200 Persian-speaking students selected based on the Cochran's formula from various fields in Tehran completed the questionnaire in 2024, using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were being an undergraduate university student and being healthy in cognitive and verbal abilities. The exclusion criteria included refusal to participate in the research and incomplete responses to the questionnaire.

Procedure and Implementation: After obtaining permission from the home university, the researcher visited Tehran University and the Islamic Azad University—Science and Research Branch. Upon receiving permission to conduct the project and coordinating with the research and education units of the aforementioned universities, the researcher was authorized to proceed. While explaining the purpose of the study, she requested that participants answer all items on the questionnaire. Participants were assured that their information would remain confidential, and they were informed that they could choose not to complete the questionnaire if they wished. After the initial review, 50 questionnaires were discarded due to defects and lack of completion. Ultimately, 150 completed questionnaires were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis: SPSS 26 software was used for descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis, while LISREL 8.8 software was utilized to determine the overall fit of the confirmatory factor analysis model.

Construct Validity: For the 15 questionnaire items, factor loading was performed for exploratory factor analysis. To assess the adequacy of sampling for factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s sphericity test were used. For factor extraction, any factor with an eigenvalue greater than one was considered.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis: For model fit, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was calculated as a parsimony-adjusted index. An RMSEA value between 0.05 and 0.08 is considered acceptable. In addition, several fit indices were calculated, including chi-square (Chi-Square/df), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), relative fit index (RFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). If the p-value is greater than 0.05 and the chi-square index relative to the degrees of freedom (χ²/df) is less than three, it indicates that the model fits well.

Findings

A total of 150 university students participated in the research, consisting of 83 women and 67 men. The mean age for women was 27.20±3.11 years, while for men, it was 29.16±4.17 years.

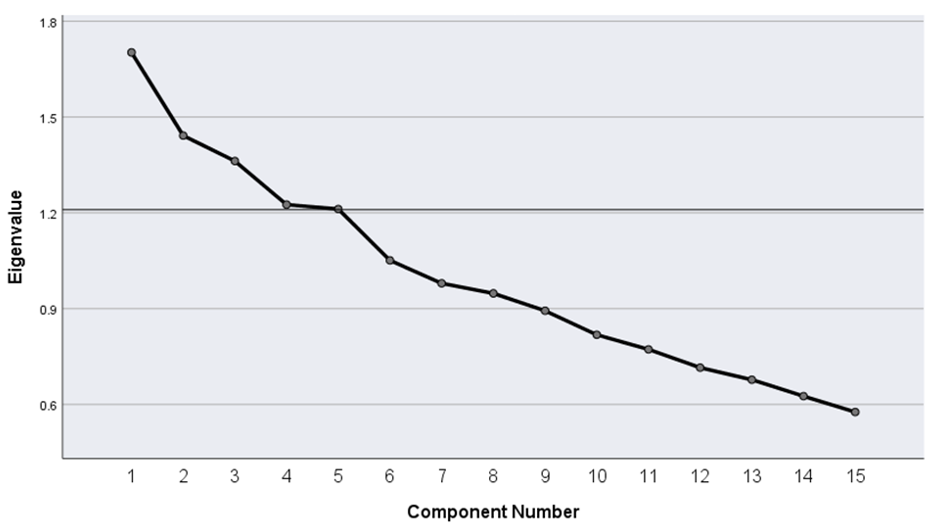

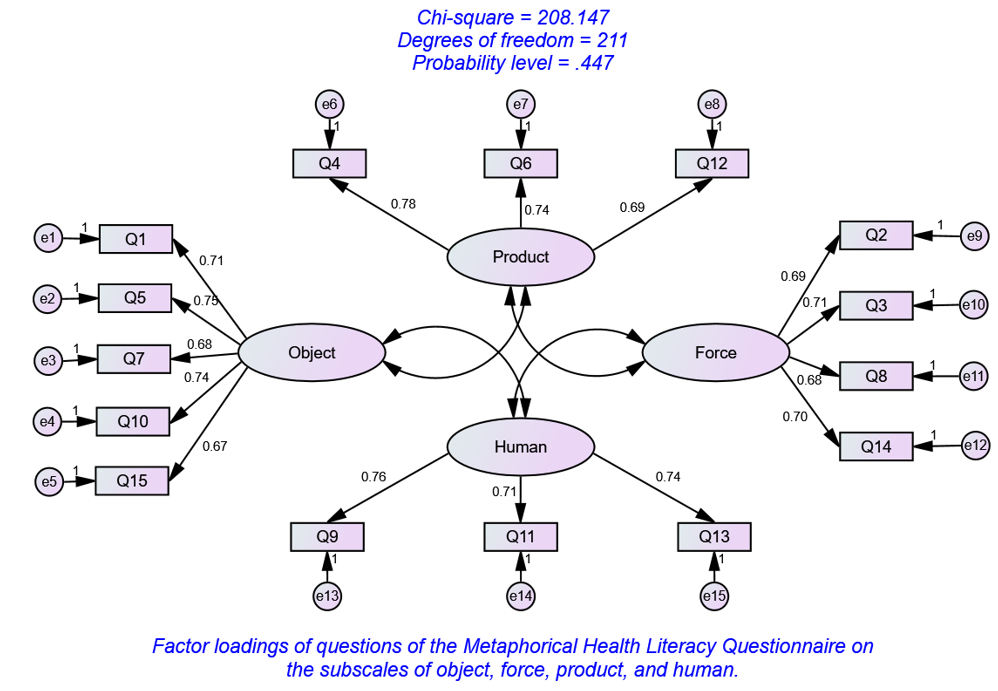

To determine the factor structure of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire, the exploratory factor analysis method of principal components with varimax rotation was employed. The KMO was calculated to be 0.81. Since this index ranges from zero to one, a value from 0.8 to 0.9 is considered good. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p=0.001). In this questionnaire, four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.20 were evident in the scree diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scree diagram of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire

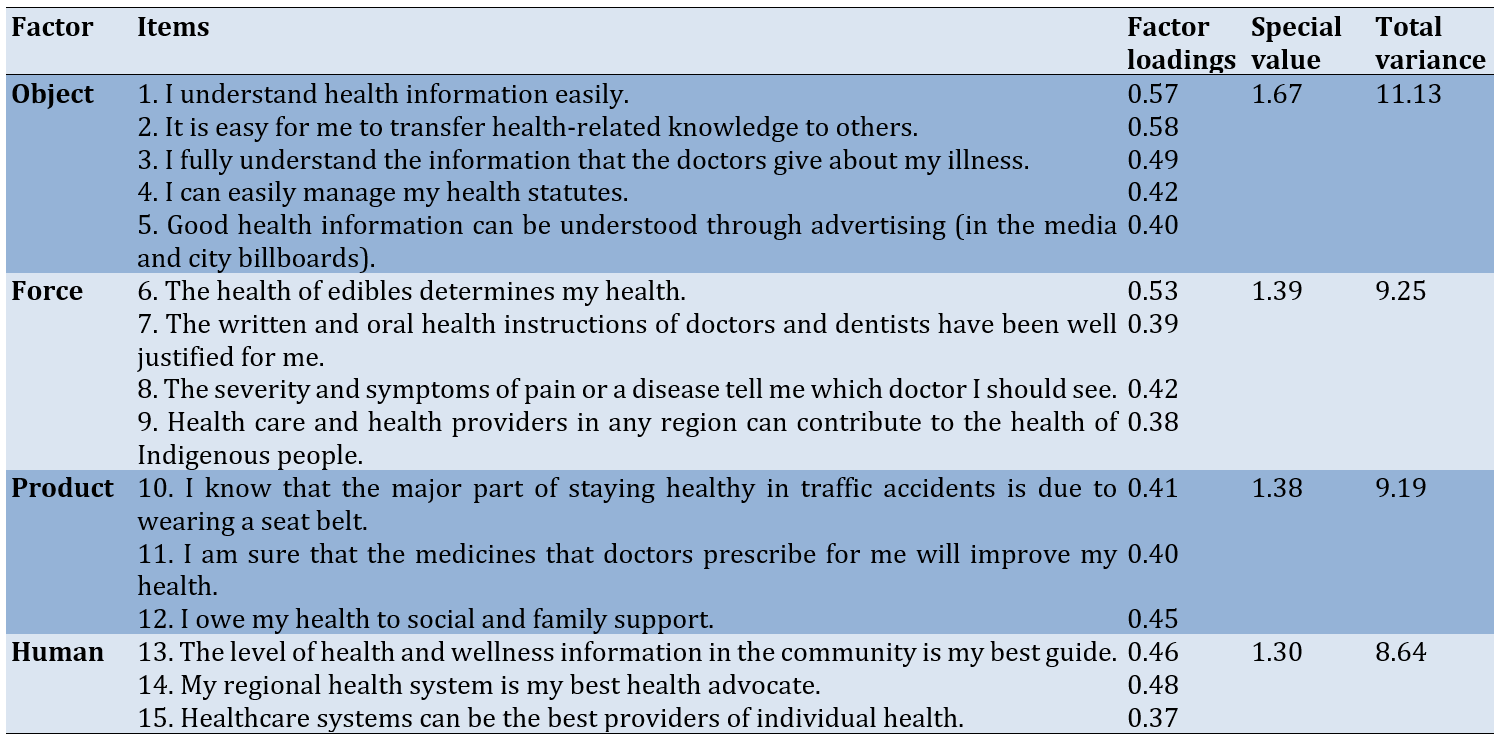

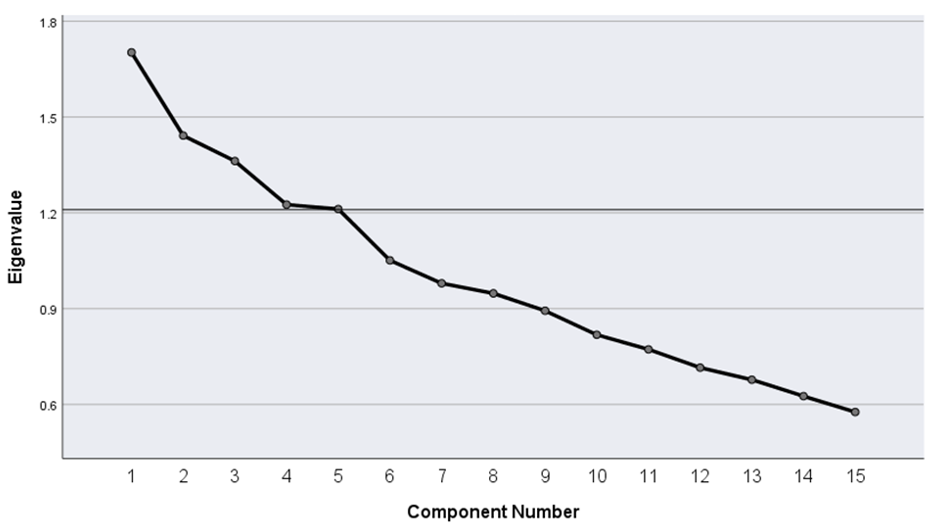

The factor analysis results indicated that the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire consisted of four factors that explained 38.21% of the total variance. The first factor explained the object; the second factor represented force; the third factor expressed product; and the fourth factor showed humans. The first factor (object) accounted for 11.13% of the total variance, with five items on this factor having a loading greater than 0.30. The second factor (force) explained 9.25% of the total variance, with four items on this factor having a loading greater than 0.30. The third factor (product) accounted for 19.9% of the total variance, with three items on this factor having a loading greater than 0.30. Finally, the fourth factor (human) explained 8.64% of the total variance, with three items on this factor also having a loading greater than 0.30 (Table 1).

Table 1. Factor loadings of items of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire

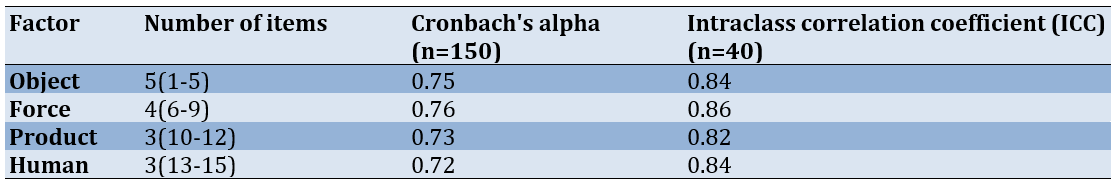

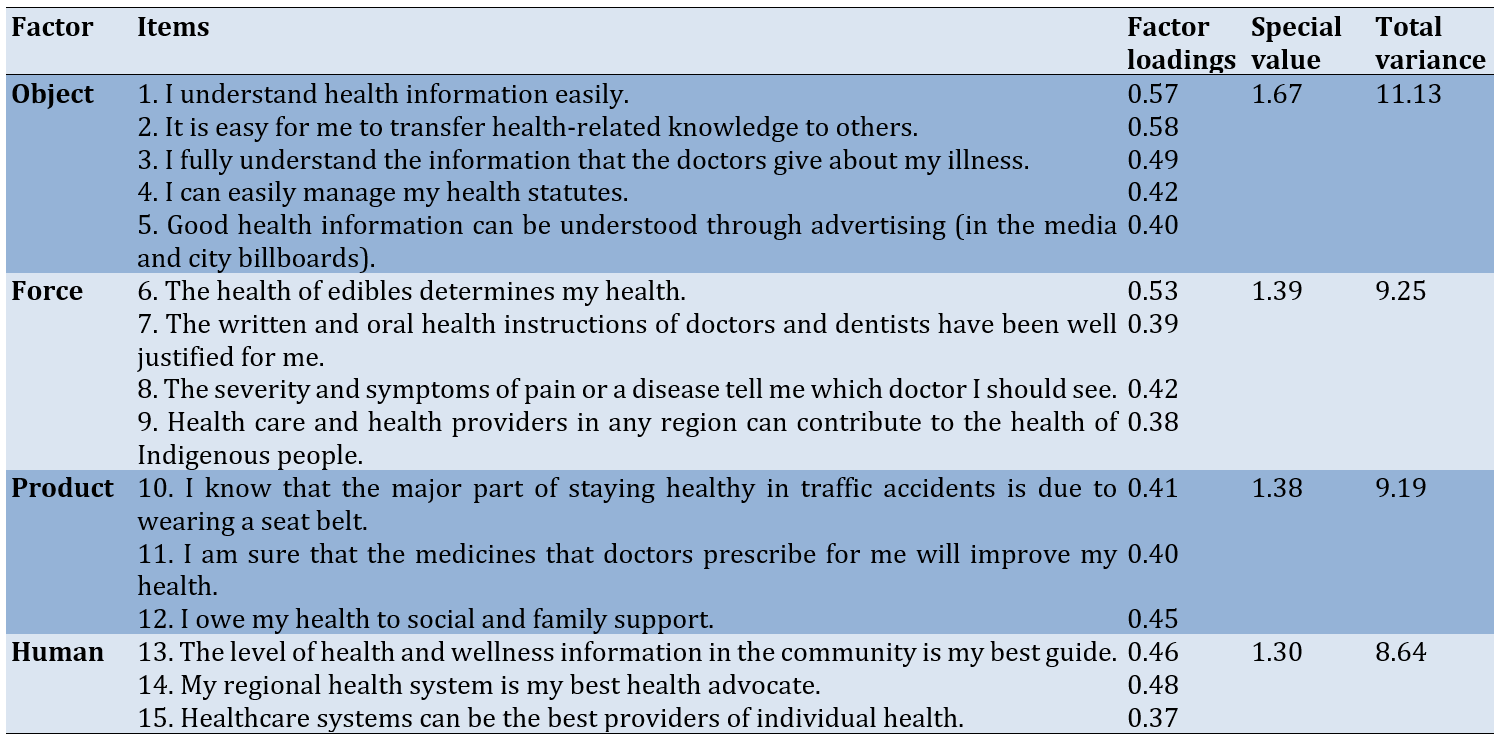

The reliability of this questionnaire was measured using Cronbach’s alpha calculated for each subscale. The reliability coefficient (internal consistency) for the entire questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach’s alpha method, resulting in a value of 0.79. Furthermore, the overall ICC was 0.88, with the subscales ranging from 0.82 to 0.86 (Table 2).

Table 2. Internal consistency, and stability

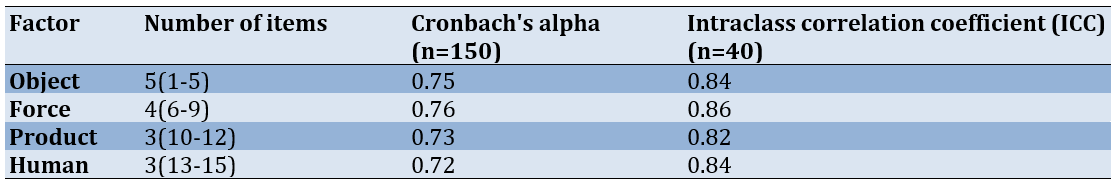

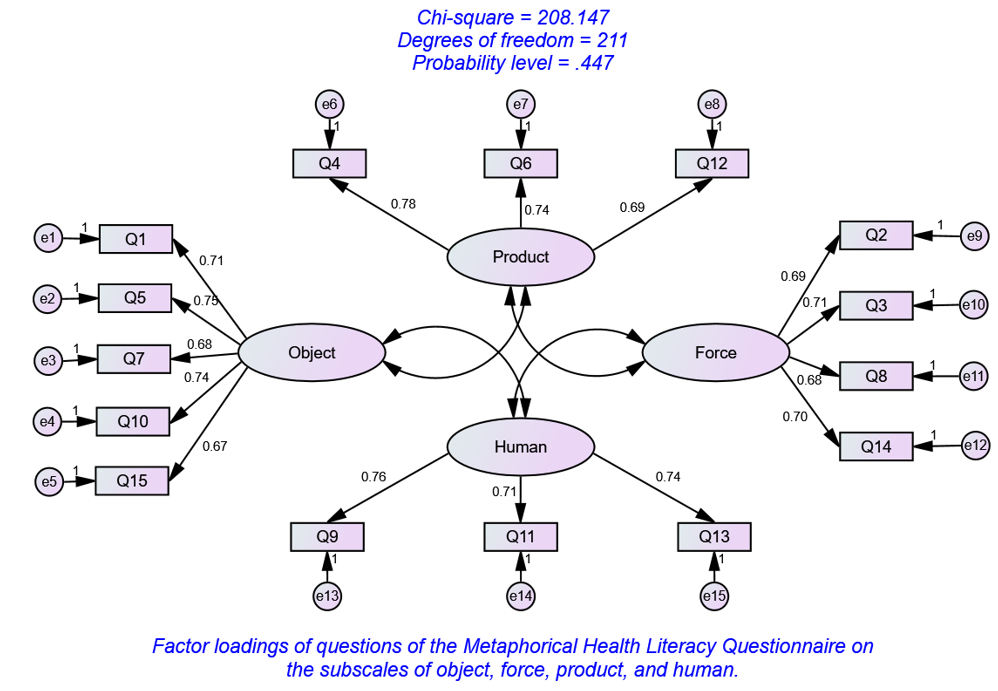

To verify the factor structure of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the structural equation method. The value of chi-square (χ²) was 208.147, the degrees of freedom were 211, and the significance value was 0.447, with the chi-square index relative to the degrees of freedom being 0.986. Therefore, the value of the RMSEA fell within the acceptable range (0.07). The GFI, AGFI, and CFI were 0.93, 0.91, and 0.95, respectively. Thus, the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire model was a good fit (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Standardized coefficients of the items loaded on the subscales of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire (object, person, product, and human))

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to design, construct, and evaluate the psychometric characteristics of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha method for the entire questionnaire and its subscales, yielding desirable results that indicated a high level of reliability. Through exploratory factor analysis, the construct validity of the questionnaire revealed four factors that explained 38.21% of the total variance. Specifically, five items loaded on the object factor, four items on the force factor, three items on the product factor, and three items on the human factor. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to verify the factorial validity of the questionnaire, demonstrating an appropriate fit of the model for determining the factors. The results of these indicators are largely consistent with those of the Health Literacy Questionnaire developed by Montazeri et al. [25] and the Iranian version of the eHealth Literacy Scale by Bazm et al. [26]. Based on this content, health literacy is a measurable concept and parameter that can be assessed through valid and reliable tools from various perspectives and interdisciplinary viewpoints.

We evaluated health literacy from the perspective of the most important field of cognitive linguistics, namely conceptual metaphors. Since health and its related concepts are abstract in nature and need to be understood through health messages, the use of metaphors is equally necessary [30]. As shown in previous studies, health literacy questionnaires are based on health messages reported among Iranians. Here, health literacy was examined from a different perspective. The metaphorical approach to health literacy and the development of a tool in this interdisciplinary field distinguish this study from prior research. Based on the findings of Raiisi [22], conceptual metaphors play an important and significant role in four domains of health literacy, such as knowledge, services, strategies, and health literacy interventions. Another finding of this study was that the most common source domains in health literacy categories were objects, forces, products, and humans. Consequently, with the introduction of conceptual metaphors in the fields of health, healthcare, and related concepts, such as quality of life [31], it appears that a deeper understanding and perception of these concepts through metaphors has emerged [32].

Accordingly, the Health Literacy Metaphor Questionnaire has acceptable validity and reliability. The factor analysis indicated four source domains as subscales for the metaphors of the health literacy questionnaire, including object, force, product, and human. As mentioned previously, metaphorical language, or conceptual metaphors, serves as a comprehensive reflection of the mind [33] and cognitive processes. They promote cognitive discipline and organize the intellectual system [34]. Metaphors can be effective in building schemas, impressions, and individual perceptions regarding the understanding of health concepts [35]. According to the embodiment rule of conceptual metaphors in Lakoff’s theory [36], health is a concept that corresponds to the human body [37]. Since the properties of the source domain are bodily and experiential, metaphorical health messages are likely to be better understood and more meaningful [38]. In other words, we should use conceptual metaphors to express concepts and instructions related to health. Metaphors generate neural networks that create common nodes between health-related messages, facilitating their understanding and perception [39]. The same network, formed at the level of cognition and through speech, challenges the individual’s cognitive system and leads to the production of higher or more complex neural networks [40].

This study, like any other, is not without limitations. The restriction of the sample to students from several universities in Tehran indicates that it was not possible to obtain a diverse sample due to the nature of the available participants. It would be beneficial to examine the psychometric properties of this questionnaire on more diverse samples in future studies. Therefore, it is recommended that researchers in future applied studies investigate the conceptual metaphors of health literacy and their changes in the cognitive system and at the neurological level as part of an intervention package. Researchers are also encouraged to use metaphorical health literacy questionnaires in their studies alongside other health literacy questionnaires to determine how metaphorical understanding and perception of health literacy can facilitate and enhance their research processes. It can be anticipated that this newly established scale will contribute to the definitions of health-related concepts, the education of these concepts, and the promotion of health literacy.

Conclusion

The Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire is a valid and useful tool for assessing health literacy.

Acknowledgments: The students of Tehran University and Islamic Azad University—Science and Research Branch—who participated in this study are gratefully acknowledged.

Ethical Permissions: All ethical principles were observed in accordance with the Helsinki Convention. The ethical code for this study is: IR.IAU.H.REC.1402.157.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Raiisi F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (100%)

Funding/Support: No financial support was received for this study.

Health literacy is recognized as an important and vital indicator of healthcare outcomes and costs [1]. In other words, healthcare systems require high levels of health literacy [2]. Health literacy is widely considered a determinant of the health status of society and a priority in the agenda of public health policies [3]. It is defined as a broad range of values and skills related to acquiring, processing, understanding, and using health information [4]. Health literacy empowers people to play an active role in changing environments that affect health [5]. Therefore, the concept of health literacy reflects not only individual responsibility but also a cognitive challenge to increase awareness [6]. Since one of the missions of health literacy is to create mental and cognitive changes in people’s minds, conceptual metaphors can promote this goal [7]. Many concepts related to health, such as quality of life [8] and pain [9, 10], are also redefined through metaphors.

The conceptual metaphors proposed by Lakoff and Johnson [11] form the foundation of our cognitive system. Therefore, every conceptual metaphor consists of two components or domains: source and target domains [12]. The source domain is based on bodily characteristics and is entirely material and experiential [13]. Thus, the source domain is considered to be embodied; in other words, it follows physical or bodily characteristics [14]. The target domain is an abstract and immaterial field identified by the source domain. This phenomenon is referred to as mapping or metaphorical implications [15]. Conceptual metaphors can serve as tools for enhancing health literacy [16]. Most concepts in the field of health literacy are metaphorical; in other words, many concepts related to health are understood through conceptual metaphors [17]. Understanding these conceptual metaphors in the field of health is also linked to cognitive and metaphorical development [18].

A study found that viewing health literacy from a metaphorical perspective improves health-related activities [19]. Metaphorical messages can highlight the dangers associated with maintaining health and can be practically effective in promoting the health level of society [20]. Conceptual metaphors can facilitate social care, communication, and health promotion [21]. One study indicated that conceptual metaphors can be applied to health literacy knowledge, literacy services, literacy strategies, and literacy interventions [22]. An analysis of a qualitative study involving patients demonstrated how similar metaphors can be utilized in ways that are both empowering and disabling in the health domain, as patients attempt to come to terms with their health and illness through metaphors [23]. The use of metaphor in health discourse is effective. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the metaphor of a “war” against the virus was introduced, employing military language to describe the fight against disease and the maintenance of health. Conversely, this military language conveys the need for strict discipline and high-level management to ensure health [24].

Based on our search, there is no independent questionnaire available in the research literature that can measure metaphorical health literacy. Most tools for measuring health literacy are general and specifically focused on the health field, such as the health literacy questionnaire designed for the urban population of Iran [25]. This questionnaire was developed with a sample of 366 individuals aged 18 to 65 living in various districts of Tehran and was tailored to the cultural and social characteristics of Iran. It has construct validity through exploratory factor analysis and reliability assessed by calculating the internal correlation coefficient. The questionnaire includes subscales for access, reading skills, comprehension, evaluation, decision-making, and behavior. Another scale is the Electronic Health Literacy Questionnaire [26]. This questionnaire was administered to 525 young people and consisted of ten items. In this questionnaire, criterion validity was examined by applying Pearson correlations between the measured constructs as well as a computer literacy questionnaire. The internal consistency of the scale was sufficient (alpha=0.88), and the test-retest coefficients for the items were reliable (r=0.96).

The importance of conceptual metaphors in the field of health becomes clear when the transmission and understanding of health messages are considered essential [27]. Conceptual metaphors and their significance in health have recently entered interdisciplinary studies [28]. Metaphors and figurative language have been utilized in the fields of health, healthcare, and social care to aid communication with patients, visualize illness, conceptualize illness and embodiment, and inform health education experiences and related concepts. From another perspective, although common health literacy questionnaires use conceptual metaphors to understand health concepts, they are not specifically metaphorical. As mentioned, learning and comprehending health-related concepts is facilitated by metaphors. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the health field from various perspectives, particularly verbal-cognitive, to enhance the understanding of health concepts, especially during critical times (such as epidemics of infectious diseases or emergencies). In foreign literature, few items address health literacy in the form of health tools. These tools often contain scattered items or lack comprehensive psychometric evaluation. For these reasons, it is evident that due to the absence of metaphorical tools in both domestic and foreign research literature, it is appropriate to design and evaluate a psychometrically valid tool in the field of metaphorical health literacy. Hence, the purpose of this study was to design, construct, and examine the psychometric characteristics of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire in the Persian language.

Instrument and Methods

Design and participants

This descriptive research involved both survey and psychometric studies and was conducted in Tehran, in 2024. The steps for preparing the metaphorical health literacy questionnaire were carried out in several stages. In the first step, based on Lakoff’s conceptual metaphor theory and Raiisi’s qualitative-cognitive study [22], the source domains for health literacy metaphors in the Persian language were identified, including the source domains of object, force, human, and product. In the second step, four main areas were identified through text mining, including knowledge, services, strategies, and interventions. To begin the assessment of psychometric properties, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine the main factor structure. As a result, the main factor structure was established, and items with insufficient loadings were removed. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis was employed to assess the coherence between the data and the construct.

Phase 1: Item designing

A qualitative study was conducted to construct the scale. From a review of 200 health articles, four areas—knowledge, services, strategies, and interventions—were identified through text mining. For each of these areas, five items were designed based on the identified health literacy metaphor source domains from Raiisi’s study in the Persian language [22]. Subsequently, an independent sample of 40 health students was selected based on Cochran's formula and asked to respond to the items. The entry criteria for health students included being an undergraduate student, being between the ages of 18 and 24, and being enrolled at one of the public or private universities in Tehran. The exclusion criterion was a refusal to complete the questionnaire. The average age of these students was 21.85, with a standard deviation of 2.24. They were asked to evaluate the relevance, clarity, and meaningfulness of the questionnaire items. The researcher requested that they write down any personal opinions or suggestions for improving the items next to each question. At this stage, the researcher addressed all of the students’ questions and ambiguities regarding the items and noted their feedback. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was analyzed using SPSS 26 software. After the item analysis, five items were removed due to a lack of clarity for the health students.

Content Validity: In the next step, for content validity, the Delphi survey technique was employed. Ten experts from relevant fields expressed their opinions on the questionnaire items using the Waltz & Bausell method and formula [29]. Specifically, three cognitive linguists, two health psychologists, two health experts, two physicians, and one psychometric expert reviewed the questionnaire. They provided feedback on the clarity, relevance, and necessity of each item. The minimum acceptable value for the content validity index was set at 0.79. According to the experts, all the items were deemed appropriate, necessary, and relevant; therefore, no items were deleted or replaced. Finally, the content validity index for the 15 items was calculated and accepted.

Phase 2: Tool production, participants, and implementation

Tool Production and Participants: After establishing content validity, a 15-item Likert-type questionnaire was prepared. The scoring method ranged from five (strongly agree) to one (strongly disagree). The minimum score obtainable from the entire questionnaire is 15, while the maximum score is 75. To assess reliability, 200 Persian-speaking students selected based on the Cochran's formula from various fields in Tehran completed the questionnaire in 2024, using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were being an undergraduate university student and being healthy in cognitive and verbal abilities. The exclusion criteria included refusal to participate in the research and incomplete responses to the questionnaire.

Procedure and Implementation: After obtaining permission from the home university, the researcher visited Tehran University and the Islamic Azad University—Science and Research Branch. Upon receiving permission to conduct the project and coordinating with the research and education units of the aforementioned universities, the researcher was authorized to proceed. While explaining the purpose of the study, she requested that participants answer all items on the questionnaire. Participants were assured that their information would remain confidential, and they were informed that they could choose not to complete the questionnaire if they wished. After the initial review, 50 questionnaires were discarded due to defects and lack of completion. Ultimately, 150 completed questionnaires were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis: SPSS 26 software was used for descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis, while LISREL 8.8 software was utilized to determine the overall fit of the confirmatory factor analysis model.

Construct Validity: For the 15 questionnaire items, factor loading was performed for exploratory factor analysis. To assess the adequacy of sampling for factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s sphericity test were used. For factor extraction, any factor with an eigenvalue greater than one was considered.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis: For model fit, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was calculated as a parsimony-adjusted index. An RMSEA value between 0.05 and 0.08 is considered acceptable. In addition, several fit indices were calculated, including chi-square (Chi-Square/df), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), relative fit index (RFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). If the p-value is greater than 0.05 and the chi-square index relative to the degrees of freedom (χ²/df) is less than three, it indicates that the model fits well.

Findings

A total of 150 university students participated in the research, consisting of 83 women and 67 men. The mean age for women was 27.20±3.11 years, while for men, it was 29.16±4.17 years.

To determine the factor structure of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire, the exploratory factor analysis method of principal components with varimax rotation was employed. The KMO was calculated to be 0.81. Since this index ranges from zero to one, a value from 0.8 to 0.9 is considered good. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p=0.001). In this questionnaire, four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.20 were evident in the scree diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scree diagram of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire

The factor analysis results indicated that the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire consisted of four factors that explained 38.21% of the total variance. The first factor explained the object; the second factor represented force; the third factor expressed product; and the fourth factor showed humans. The first factor (object) accounted for 11.13% of the total variance, with five items on this factor having a loading greater than 0.30. The second factor (force) explained 9.25% of the total variance, with four items on this factor having a loading greater than 0.30. The third factor (product) accounted for 19.9% of the total variance, with three items on this factor having a loading greater than 0.30. Finally, the fourth factor (human) explained 8.64% of the total variance, with three items on this factor also having a loading greater than 0.30 (Table 1).

Table 1. Factor loadings of items of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire

The reliability of this questionnaire was measured using Cronbach’s alpha calculated for each subscale. The reliability coefficient (internal consistency) for the entire questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach’s alpha method, resulting in a value of 0.79. Furthermore, the overall ICC was 0.88, with the subscales ranging from 0.82 to 0.86 (Table 2).

Table 2. Internal consistency, and stability

To verify the factor structure of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the structural equation method. The value of chi-square (χ²) was 208.147, the degrees of freedom were 211, and the significance value was 0.447, with the chi-square index relative to the degrees of freedom being 0.986. Therefore, the value of the RMSEA fell within the acceptable range (0.07). The GFI, AGFI, and CFI were 0.93, 0.91, and 0.95, respectively. Thus, the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire model was a good fit (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Standardized coefficients of the items loaded on the subscales of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire (object, person, product, and human))

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to design, construct, and evaluate the psychometric characteristics of the Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha method for the entire questionnaire and its subscales, yielding desirable results that indicated a high level of reliability. Through exploratory factor analysis, the construct validity of the questionnaire revealed four factors that explained 38.21% of the total variance. Specifically, five items loaded on the object factor, four items on the force factor, three items on the product factor, and three items on the human factor. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to verify the factorial validity of the questionnaire, demonstrating an appropriate fit of the model for determining the factors. The results of these indicators are largely consistent with those of the Health Literacy Questionnaire developed by Montazeri et al. [25] and the Iranian version of the eHealth Literacy Scale by Bazm et al. [26]. Based on this content, health literacy is a measurable concept and parameter that can be assessed through valid and reliable tools from various perspectives and interdisciplinary viewpoints.

We evaluated health literacy from the perspective of the most important field of cognitive linguistics, namely conceptual metaphors. Since health and its related concepts are abstract in nature and need to be understood through health messages, the use of metaphors is equally necessary [30]. As shown in previous studies, health literacy questionnaires are based on health messages reported among Iranians. Here, health literacy was examined from a different perspective. The metaphorical approach to health literacy and the development of a tool in this interdisciplinary field distinguish this study from prior research. Based on the findings of Raiisi [22], conceptual metaphors play an important and significant role in four domains of health literacy, such as knowledge, services, strategies, and health literacy interventions. Another finding of this study was that the most common source domains in health literacy categories were objects, forces, products, and humans. Consequently, with the introduction of conceptual metaphors in the fields of health, healthcare, and related concepts, such as quality of life [31], it appears that a deeper understanding and perception of these concepts through metaphors has emerged [32].

Accordingly, the Health Literacy Metaphor Questionnaire has acceptable validity and reliability. The factor analysis indicated four source domains as subscales for the metaphors of the health literacy questionnaire, including object, force, product, and human. As mentioned previously, metaphorical language, or conceptual metaphors, serves as a comprehensive reflection of the mind [33] and cognitive processes. They promote cognitive discipline and organize the intellectual system [34]. Metaphors can be effective in building schemas, impressions, and individual perceptions regarding the understanding of health concepts [35]. According to the embodiment rule of conceptual metaphors in Lakoff’s theory [36], health is a concept that corresponds to the human body [37]. Since the properties of the source domain are bodily and experiential, metaphorical health messages are likely to be better understood and more meaningful [38]. In other words, we should use conceptual metaphors to express concepts and instructions related to health. Metaphors generate neural networks that create common nodes between health-related messages, facilitating their understanding and perception [39]. The same network, formed at the level of cognition and through speech, challenges the individual’s cognitive system and leads to the production of higher or more complex neural networks [40].

This study, like any other, is not without limitations. The restriction of the sample to students from several universities in Tehran indicates that it was not possible to obtain a diverse sample due to the nature of the available participants. It would be beneficial to examine the psychometric properties of this questionnaire on more diverse samples in future studies. Therefore, it is recommended that researchers in future applied studies investigate the conceptual metaphors of health literacy and their changes in the cognitive system and at the neurological level as part of an intervention package. Researchers are also encouraged to use metaphorical health literacy questionnaires in their studies alongside other health literacy questionnaires to determine how metaphorical understanding and perception of health literacy can facilitate and enhance their research processes. It can be anticipated that this newly established scale will contribute to the definitions of health-related concepts, the education of these concepts, and the promotion of health literacy.

Conclusion

The Metaphorical Health Literacy Questionnaire is a valid and useful tool for assessing health literacy.

Acknowledgments: The students of Tehran University and Islamic Azad University—Science and Research Branch—who participated in this study are gratefully acknowledged.

Ethical Permissions: All ethical principles were observed in accordance with the Helsinki Convention. The ethical code for this study is: IR.IAU.H.REC.1402.157.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Raiisi F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (100%)

Funding/Support: No financial support was received for this study.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Literacy

Received: 2025/02/10 | Accepted: 2025/03/25 | Published: 2025/03/28

Received: 2025/02/10 | Accepted: 2025/03/25 | Published: 2025/03/28

References

1. Coughlin SS, Vernon M, Hatzigeorgiou C, George V. Health literacy, social determinants of health, and disease prevention and control. J Environ Health Sci. 2020;6(1):3061. [Link]

2. Bindhu S, Nattam A, Xu C, Vithala T, Grant T, Dariotis JK, et al. Roles of health literacy in relation to social determinants of health and recommendations for informatics-based interventions: Systematic review. Online J Public Health Inform. 2024;16:e50898. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/50898]

3. Ayre J, Zhang M, Mouwad D, Zachariah D, McCaffery KJ, Muscat DM. A systematic review of health literacy champions: Who, what and how?. Health Promot Int. 2023;38(4):daad074. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daad074]

4. Tsai HY, Lee SD, Coleman C, Sørensen K, Tsai TI. Health literacy competency requirements for health professionals: A Delphi consensus study in Taiwan. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):209. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-024-05198-4]

5. Haseli A, Bagheri L, Ghiasi A. A study on the relationship between quality of life and health literacy among students. J Health Lit. 2024;9(3):106-13. [Persian] [Link]

6. Chen P, Callisaya M, Wills K, Greenaway T, Winzenberg T. Cognition, educational attainment, and diabetes distress predict poor health literacy in diabetes: A cross-sectional analysis of the SHELLED study. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0267265. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0267265]

7. Jochem C, Von Sommoggy J, Hornidge AK, Schwienhorst-Stich EM, Apfelbacher C. Planetary health literacy: A conceptual model. Front Public Health. 2023;10:980779. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2022.980779]

8. Raiisi F. Cognitive analysis of quality of life metaphors from the perspective of health promotion students. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;10(2):233-8. [Link]

9. Raiisi F. Conceptual metaphors of pain in Persian: A cognitive analysis. Int J Musculoskelet Pain Prev. 2021;6(2):496-501. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/ijmpp.6.2.496]

10. Raiisi F. Pain metaphors as a bridge between physician and patient: An interdisciplinary approach. Int J Musculoskelet Pain Prev. 2023;8(2):862-3. [Link]

11. Lakoff G, Johnson M. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003. [Link] [DOI:10.7208/chicago/9780226470993.001.0001]

12. Kövecses K. Metaphor universals in literature. ANTARES LETRAS E HUMANIDADES. 2018; 10(20):154-68. [Link] [DOI:10.18226/19844921.v10.n20.10]

13. Kövecses Z. Meaning making, where metaphors come from: Reconsidering context in metaphor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022. [Link]

14. Khatin-Zadeh O, Farsani D, Hu J, Eskandari Z, Zhu Y, Banaruee H. A review of studies supporting metaphorical embodiment. Behav Sci. 2023;13(7):585. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/bs13070585]

15. Coll-Florit M, Climent Roca S. A new methodology for conceptual metaphor detection and formulation in corpora: A case study on a mental health corpus. SKY J Linguist. 2019;32:43-74. [Link]

16. Krieger JL, Parrott RL, Nussbaum JF. Metaphor use and health literacy: A pilot study of strategies to explain randomization in cancer clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2011;16(1):3-16. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2010.529494]

17. Lazard AJ, Bamgbade BA, Sontag JM, Brown C. Using visual metaphors in health messages: A strategy to increase effectiveness for mental illness communication. J Health Commun. 2016;21(12):1260-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2016.1245374]

18. Raiisi F, Afrashi A, Moghadasin M, Nematzadeh S, Hajikaram A. Understanding of metaphorical time pattern among medical and paramedical students. Based on gender, age, and academic status. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2019;24(4):56-67. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/sjku.24.4.56]

19. Talley J. Moving from the margins: The role of narrative and metaphor in health literacy. J Commun Healthc. 2016;9(2):109-19. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17538068.2016.1177923]

20. Landau MJ, Arndt J, Cameron LD. Do metaphors in health messages work? Exploring emotional and cognitive factors. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2018;74:135-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2017.09.006]

21. Buckley A, Corless L, Taylor A, Watkinson K. Metaphors in healthcare narratives and practice: Powers and pitfalls. Nurs Times. 2024;120(10). [Link]

22. Raiisi F. Metaphor thematic analysis of health literacy; A systematic review. Health Educ Health Promot. 2024;12(1):131-7. [Link]

23. Lempp H, Tang C, Heavey E, Bristowe K, Allan H, Lawrence V, et al. The use of metaphors by service users with diverse long-term conditions: A secondary qualitative data analysis. Qual Res Med Healthc. 2024;7(3):11336. [Link] [DOI:10.4081/qrmh.2023.11336]

24. Ten Have H, Gordijn B. Metaphors in medicine. Med Health Care Philos. 2022;25(4):577-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11019-022-10117-9]

25. Montazeri A, Tavousi M, Rakhshani F, Azin A, Jahangiri K, Ebadi M, et al. Health literacy for Iranian adults (HELIA): Development and psychometric properties. PAYESH. 2014;13(5):589-99. [Persian] [Link]

26. Bazm S, Mirzaei M, Fallahzadeh H, Bazm R. Validity and reliability of the Iranian version of ehealth literacy scale. J Commu Health Res. 2016;5(2):121-30. [Link]

27. Ervas F, Montibeller M, Rossi Maria G, Salis P. Expertise and metaphors in health communication. MEDICINA AND STORIA. 2016;9:91-108. [Link]

28. Febria D, Hastuty M, Agustina R, Yusnilasari Y, Ariani DS. Environmental health literacy and the hope tree metaphor. JURNAL PENELITIAN PENDIDIKAN IPA. 2023;9(10):8864-72. [Link] [DOI:10.29303/jppipa.v9i10.4731]

29. Zamanzadeh V, Rassouli M, Abbaszadeh A, Alavi Majd H, Nikanfar A, et al. Details of content validity and objectifying it in instrument development. Nurs Pract Today. 2014;1(3):163-71. [Link]

30. Estrela M, Semedo G, Roque F, Ferreira PL, Herdeiro MT. Sociodemographic determinants of digital health literacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Med Inform. 2023;177:105124. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105124]

31. Abedi F, Khayamzade M, Rezaeipoor M. Health metaphors in contemporary literature and media. Iran J Cult Health Promot. 2024;8(2):133-8. [Persian] [Link]

32. Tones K. Health literacy: New wine in old bottles?. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(3):287-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/her/17.3.287]

33. Parsi K. War metaphors in health care: What are they good for?. Am J Bioeth. 2016;16(10):1-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15265161.2016.1221245]

34. Kövecses K. Extended conceptual metaphor theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2020. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/9781108859127]

35. Guo Z. Conceptual metaphor and cognition: From the perspective of the philosophy of language. J Innov Dev. 2023;3(1):73-5. [Link] [DOI:10.54097/jid.v3i1.8424]

36. Wiseman R. Interpreting ancient social organization: Conceptual metaphors and image schemas. Time Mind. 2015;8(2):159-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/1751696X.2015.1026030]

37. Mácha J. Conceptual metaphor theory and classical theory: Affinities rather than divergences. In: Piotr Stalmaszczyk. From philosophy of fiction to cognitive poetics. Lausanne: Peter Lang; 2016. p. 93-115. [Link]

38. Hauser DJ, Nesse RM, Schwarz N. Lay theories and metaphors of health and illness. In: The science of lay theories. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 341-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-57306-9_14]

39. Garello S. Metaphor as a "matter of thought": Conceptual metaphor theory. In: The enigma of metaphor. Cham: Springer; 2024. p. 65-100. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-56866-4_3]

40. Demjén Z, Semino E. Using metaphor in healthcare: Physical health. In: The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language. London: Routledge; 2016. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |