Volume 13, Issue 2 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(2): 227-233 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jamei Z, Hosseini F, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Morshedi H. Health Literacy and the Health Action Process Approach in Predicting Breast Cancer Screening Behaviors. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (2) :227-233

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79759-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79759-en.html

1- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

Keywords: Health Literacy [MeSH], Breast Cancer [MeSH], Screening [MeSH], Health Action Process Approach [MeSH], Women [MeSH], Behavior [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 716 kb]

(373 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (538 Views)

Full-Text: (44 Views)

Introduction

According to the 2022 report by the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer (BC) is the second most common cancer among women worldwide, with 2.3 million new cases and 670,000 deaths attributed to this disease globally, of which 44.5% of these patients were from Asia. BC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality among women around the world. In Iran, BC is also the most common cancer among women [1]. According to the Globocan report, the estimated number of new BC cases in Iran was 16,967, with 4,810 deaths resulting from this disease in 2020 [2]. Nevertheless, BC is one of the few cancers that can be diagnosed at an early stage and is preventable through screening methods, highlighting the significance of screening programs for the early detection of this disease [3].

Various screening methods for BC include breast self-examination (BSE), clinical evaluation, and various imaging techniques. According to the IraPEN operational guidelines, all women aged 30 to 69 should visit a midwife or physician for clinical breast examinations every one to two years. Additionally, mammography is recommended to be performed annually starting at the age of 40, according to health organization guidelines [4]. Participation in BC screening programs significantly reduces mortality associated with this disease [5, 6]. However, despite the existence of screening guidelines in Iran, women’s participation in regular BC screening remains low. Only 9.9% of women perform BSE, 8.9% undergo clinical breast examinations (CBE), 12.3% have mammograms, and only 3.8% receive sonography regularly [7]. Awareness regarding BC screening plays a crucial role in utilizing related healthcare services in a timely manner for early diagnosis and management [8].

The WHO has identified the enhancement of women’s health literacy (HL) as one of the three main pillars for BC prevention [9]. Accordingly, HL is the focal point for BC screening [10]. HL is defined as “an individual’s ability to obtain and interpret knowledge and information in a way that is appropriate for their circumstances to maintain and improve health” [11]. Higher HL is associated with better health outcomes, and adequate HL is essential for empowering effective decision-making regarding seeking, accessing, and utilizing appropriate health services [12]. According to a study conducted in 2023 aimed at investigating HL levels and cancer screening behaviors among Iranian women, although over 80% of women have adequate HL, only 11.2% undergo mammography, and 73.9% never visit health centers for CBE [13]. Additionally, Momenimovahed et al. report that barriers to mammography among Asian women include personal beliefs, fatalism, fear, pain, embarrassment, religious factors, lack of family support, financial constraints, and certain sociocultural and demographic factors [14].

One effective model for understanding the factors influencing behavior is the health action process approach (HAPA), which has been applied to a wide range of health behaviors, including cancer screening [15]. The main hypothesis of this model is that, for an individual to adopt a behavior, they must progress through two phases: the motivational phase and the volitional phase. The motivational phase includes three factors, namely perceived risk, outcome expectations, and self-efficacy. The volitional phase includes behavioral intention, perceived social support, coping planning, action planning, and perceived barriers [16]. High levels of these factors in both phases contribute to better adherence to health guidelines and increased participation in screenings.

Given that HL is a key element for the early detection of BC and is thus vital for its prevention [9], and considering that primary prevention involves avoiding known risk factors while secondary prevention utilizes various BC screening methods for early identification and timely treatment of the disease—significantly reducing the multiple harms caused by this disease among women—and further noting the limited number of studies on the predictive constructs of the HAPA model in adopting BC screening behaviors among women, the present study aimed to investigate the role of HL and the HAPA model in predicting the adoption of BC screening behaviors in women.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was conducted on 350 women aged 30 to 69 years selected from the population served by comprehensive health centers in Alborz city, Qazvin Province, Iran in 2024.

Inclusion criteria included providing informed consent to participate, Iranian citizenship, having an active file in comprehensive health centers, literacy in reading and writing, no history of BC or other cancers, and being within the age range of 30 to 69 years. Exclusion criteria included a lack of willingness to participate in the study and incomplete questionnaires.

The sample size was determined based on a similar study [17], considering a 95% confidence level, with d=4.5 and S=36.1, resulting in a total of 350 participants. The sampling method used was multi-stage cluster sampling. The Alborz City was first divided into five geographical areas, namely north, south, east, west, and central. Then, using a list of urban comprehensive health centers in each area, two centers were randomly selected from each section (for a total of ten centers) through simple random sampling. Subsequently, women who met the inclusion criteria were sampled using a convenience sampling approach.

Data collection

The data collection tool was designed in four main sections, including a demographic and background information questionnaire, which included eight questions related to age, marital status, occupation, insurance status, educational level, spouse’s educational level, financial status, and family history of BC.

Health Literacy for Adults-Short Form (HELIA-SF): This questionnaire was developed by Tavousi et al. [18] in 2022 and consists of nine questions with two constructs, namely basic skills (five items) and decision-making skills (four items). Scoring was based on a five-point Likert scale (one=not sure to five=very sure), with total scores ranging from 9 to 45. For all items, the content validity ratio (CVR) was greater than 0.56, the content validity index (CVI) was greater than 0.79, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were 0.91 and 0.81, respectively.

Awareness questions: These questions measured women’s awareness regarding BC, the risk factors of the disease, and how to perform and when to conduct screening tests. They included eight true/false questions, scored as correct (one point) and incorrect (zero points), with total scores ranging from zero to eight. Awareness scores were categorized as 0-3=poor, 4-6=moderate, and 7-8=good. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for awareness in this study was 0.735.

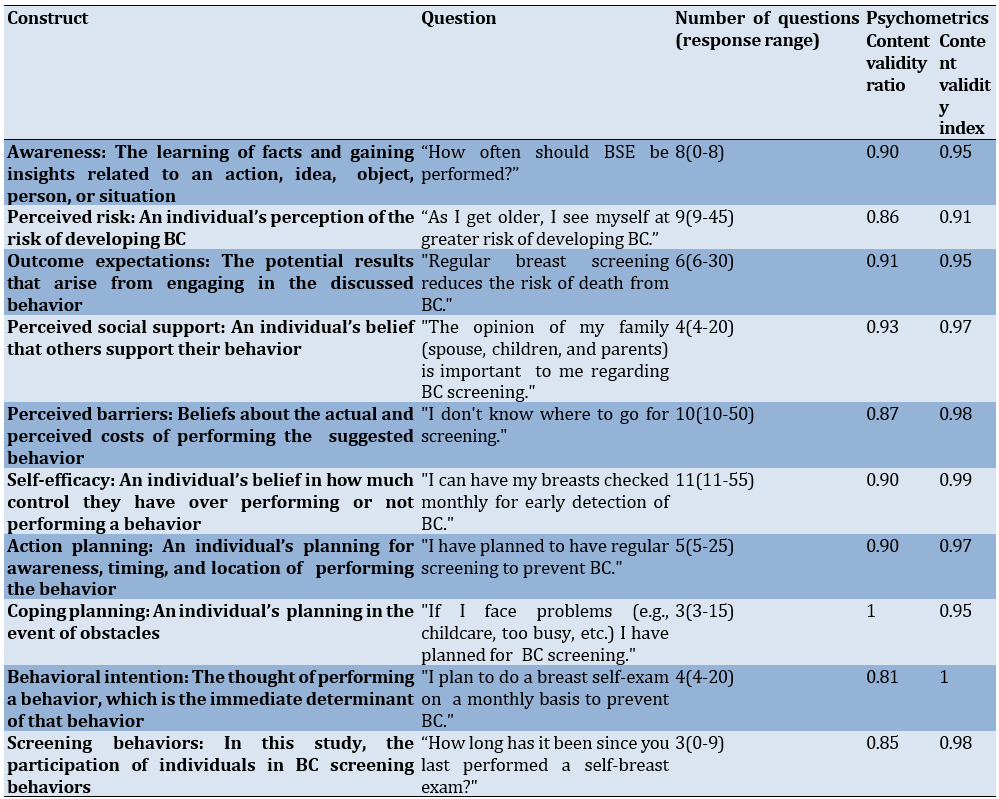

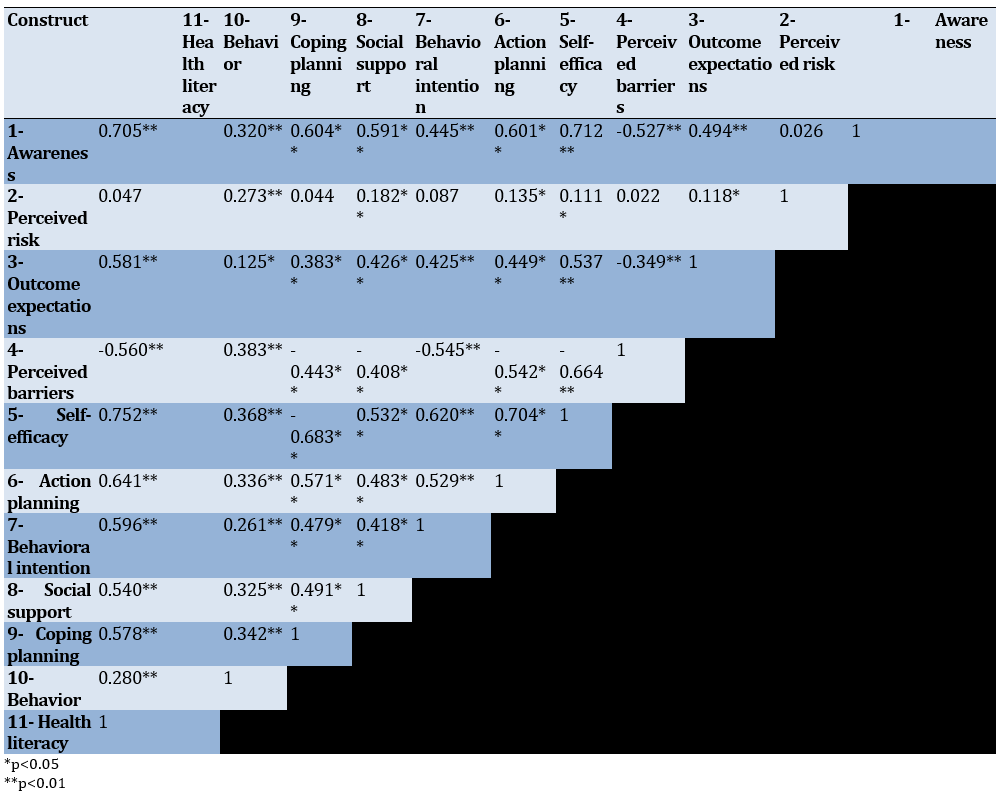

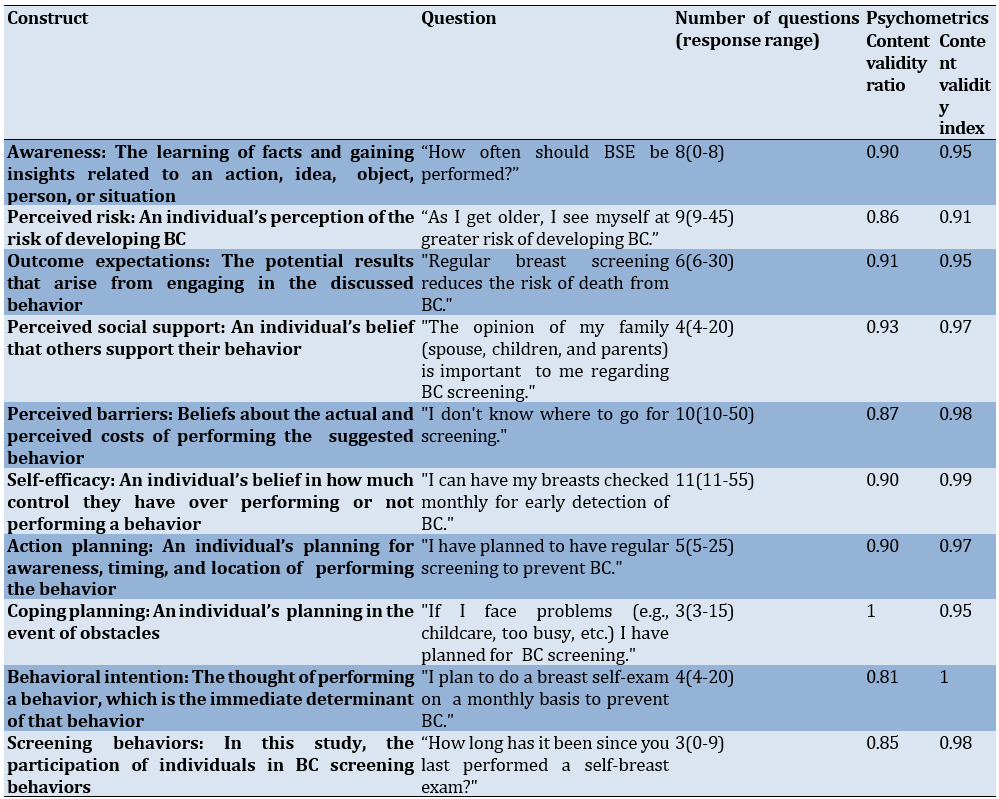

A researcher-developed questionnaire related to the HAPA: This questionnaire consisted of 55 items covering constructs, such as perceived risk, outcome expectations, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, action planning, coping planning, perceived social support, behavioral intention, and screening behaviors (BSE, CBE, and mammography). Following the design and psychometric process (face/content validity and reliability), it was utilized in the current research. The questionnaire included one reverse-scored question in the self-efficacy construct, and scoring was based on a five-point Likert scale from completely disagree (one point) to completely agree (five points). To assess the screening behavior of women, three questions were scored as never (zero points), within one year (one point), within two years (two points), and three years or more (three points), with total scores ranging from 55 to 269. For the quantitative assessment of content validity, a panel of eight experts—including four health education specialists, two midwives, and two physicians—was requested to evaluate each item based on a three-part scale (not relevant, useful but not essential, and essential) and three criteria: relevance, clarity, and simplicity, using specialized worksheets. Accordingly, the overall CVR and CVI values for awareness were calculated as 0.90 and 0.95, respectively, while for the HAPA, they were 0.89 and 0.96. Additionally, to assess face validity, interviews were conducted in person with ten women who met the eligibility criteria, gathering their opinions regarding the difficulty level, appropriateness, and ambiguity of each item. To determine the internal consistency of items within each dimension, the questionnaire was administered to 30 eligible women, yielding Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the constructs of the HAPA model ranging from 0.714 to 0.893 (Table 1).

Table 1. Constructs of the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) and Awareness Scale

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to describe the data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess data normality, the Spearman correlation coefficient to assess the relationships, and multiple regression analysis predicted screening behaviors.

Findings

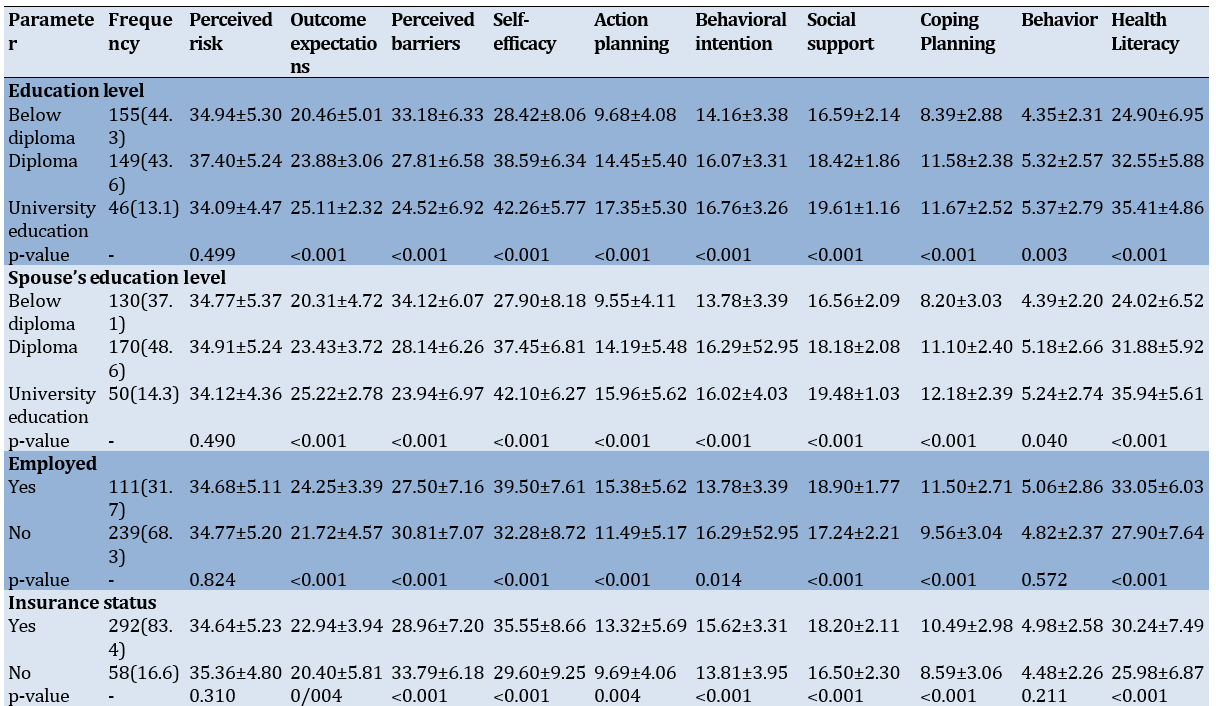

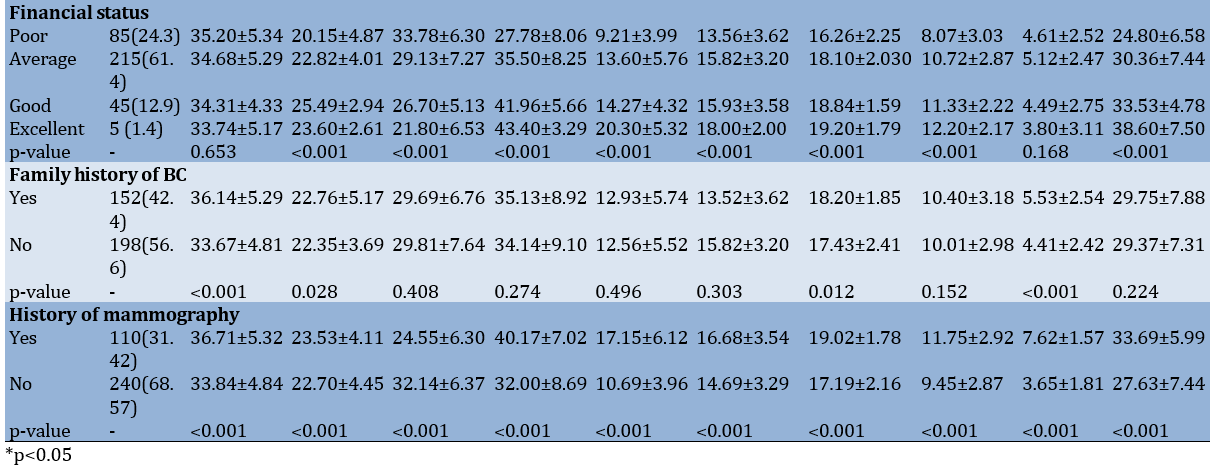

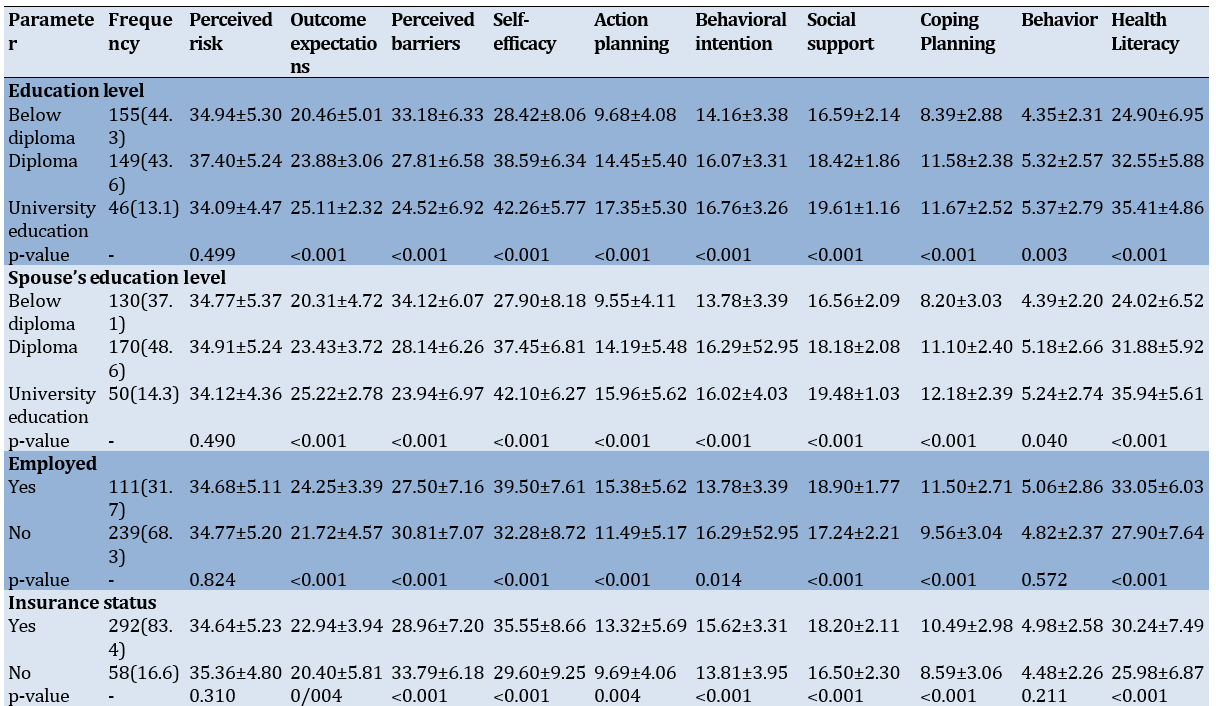

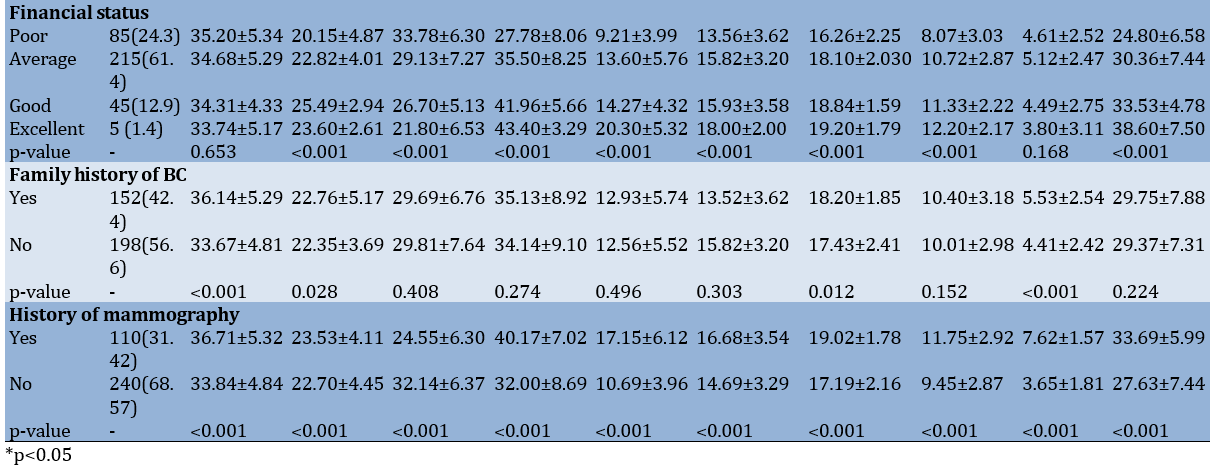

Among the 350 participants, the mean age of the women was 44.73±10.22 years. The mean scores for the awareness and HL of the participating women were 3.97±2.03 and 29.54±7.55, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) constructs and demographic characteristics of participants (n=350)

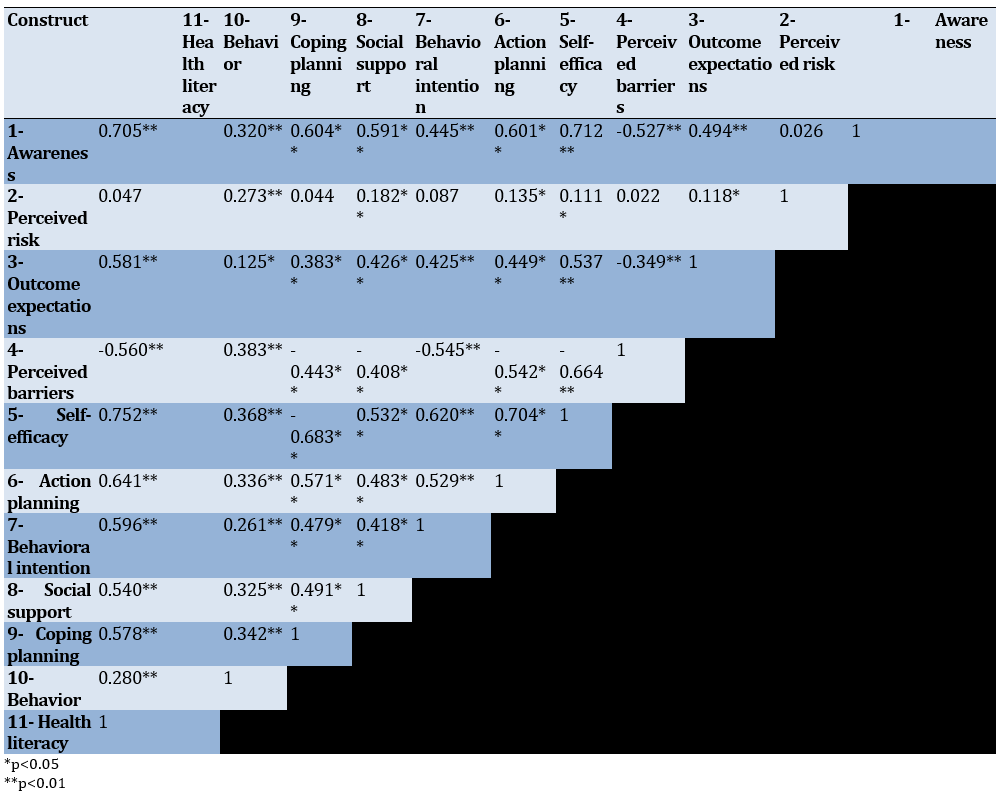

The results of the Spearman correlation coefficient demonstrated a significant positive correlation between the constructs of outcome expectations, self-efficacy, action planning, behavioral intention, perceived risk, social support, coping planning, HL, and screening behavior (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations among HAPA constructs’ scores and HL in participants (n=350)

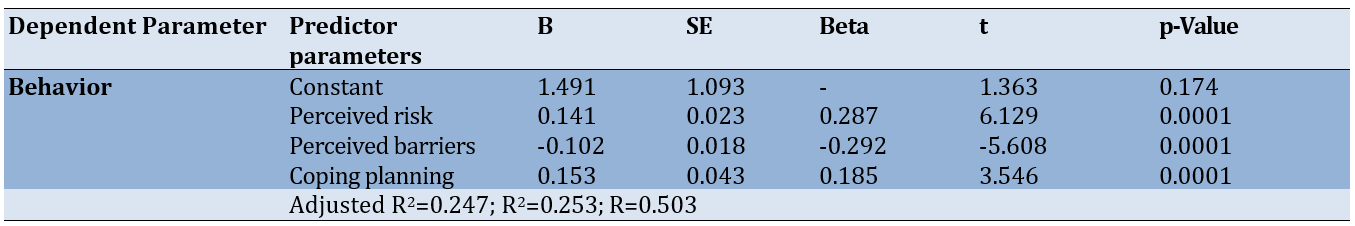

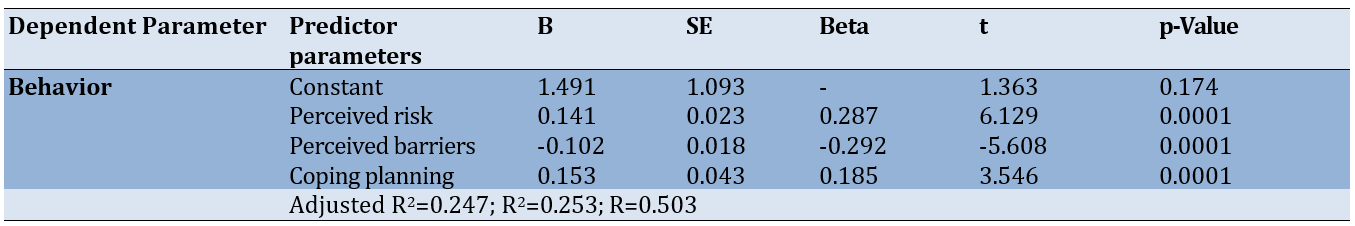

The constructs of perceived risk, perceived barriers, and coping planning accounted for 24% of the variance in screening behavior. Specifically, for each standard deviation increase in the perceived risk score, the coping planning and screening behavior scores increased by 0.28 and 0.18 standard deviations, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Regression findings for the prediction of behavior

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of HL and the HAPA in predicting BC screening behaviors among Iranian women. The awareness of the participating women regarding BC screening, particularly concerning the appropriate timing for breast examinations and the age to begin such screening behaviors, was at a weak level. High awareness helps women make better decisions regarding medical examinations. In Iran, the lack of structured intervention programs for health education in the community and the absence of regular screening programs have resulted in a low level of awareness and attitudes about cancers, especially BC. This issue has led to a decrease in the willingness of Iranian women to adopt preventive and diagnostic methods for BC, particularly BSE, ultrasound, and mammography. Results from several studies conducted in Iran indicate low awareness levels in this regard among Iranian women [19, 20]. Awareness and knowledge are considered essential components of any behavior change and serve as fundamental prerequisites for behavioral change. Their absence can lead to a lower willingness to engage in preventive behaviors [21].

The likelihood of women undergoing BC screening tests was lower among those with low HL and awareness; this is consistent with the results of several studies [22, 23]. These findings highlight the importance of HL in the timely and effective execution of BC screening tests. Women with higher HL not only have a better awareness of the importance of screening but also possess a better understanding of how to perform it. High HL enables women to accurately interpret information about BC screening and to engage more effectively with health professionals, asking more pertinent questions and receiving more precise information. Therefore, educational interventions focusing on enhancing HL and specialized knowledge concerning BC can lead to increased screening behaviors.

There was a significant correlation between the constructs of the HAPA and the performance of behaviors. Secondly, the constructs of perceived risk, perceived barriers, and coping planning were able to predict 24% of the variance in behavioral performance. Moreover, according to Parschau et al. [24] and Mohammadi Zeidi et al. [25], these constructs respectively explain 18% and 32% of the variance in behavior based on this model.

The construct of perceived risk was a significant motivational predictor for adopting screening behaviors. Specifically, for each standard deviation increase in the perceived risk score, the behavior score increased by 0.28 standard deviations. The level of perceived risk among women increases with age, and younger women often view their young age as a convincing argument against having BC. It is recommended that through education and increasing awareness, attitudes should be changed, regular examinations encouraged, and support provided for this group, so that individuals’ perceptions of the risk of developing BC are somewhat heightened. Conversely, the findings from Satoh & Sato indicate the perceived risk’s inability to motivate the use of BC screening methods [26], highlighting the need for further research in this area.

Perceived barriers play a crucial role in women’s decision-making regarding participation in BC screening programs across various dimensions. For instance, in the present study, as found in the research by Hossaini et al. and Ramezankhani et al. [27, 28], many women expressed significant concerns about the potential consequences of test results, the high costs of screening services, the belief that mammography is painful, embarrassment from examinations, the notion of fate and destiny, busy schedules, and inadequate access to reputable diagnostic centers. These were the main barriers identified by women that could discourage them from undergoing regular screening. Analysis of these barriers indicates that to promote the level of BC screening, it is necessary to design educational and supportive programs that specifically enhance awareness about the importance of screening, reduce fears, and create a supportive environment to encourage women to take effective actions concerning their health screening.

The third predictor of BC screening behaviors was coping planning. Coping planning is a self-regulatory strategy that anticipates challenging situations that may deter an individual from performing the desired behavior and plans to overcome barriers that may hinder behavioral performance [29, 30]. Individuals who were able to plan effectively to cope with potential barriers to BC screening behaviors and had specific strategies to overcome these barriers were more likely to commit to screening behaviors. This type of planning becomes particularly significant when women are faced with potential threats, and each of these two (planning and coping) can effectively impact the improvement of cancer screening behaviors, which is supported by the findings of the study by Bianchi et al. [31].

This study offers valuable insights into the roles of HL and the HAPA in influencing BC screening behaviors among Iranian women. However, limitations, such as the cross-sectional design, hinder our ability to establish causal relationships, and reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to better capture the evolving dynamics of health-seeking behaviors and assess intervention effectiveness.

In light of these findings, targeted interventions are proposed to enhance HL and improve BC screening rates. Culturally sensitive health education initiatives should be implemented through community health centers, schools, and online platforms, emphasizing the importance of BC screening. Additionally, skill-building workshops can empower women with practical skills for BSE and mammography procedures, boosting their confidence in seeking screenings. Establishing support groups will provide necessary safe spaces for women to discuss their concerns, fostering peer support and normalizing cancer-related conversations. Moreover, tailored communication strategies should ensure that information about screening accessibility and procedures is clear and understandable.

By addressing these areas, we can work towards improving BC screening rates among Iranian women, leading to earlier detection and better health outcomes. The implications of this study extend beyond Iran, highlighting the critical need for heightened awareness and proactive health-seeking behaviors globally within cancer prevention efforts.

Conclusion

The HAPA enhances women’s participation in BC screening.

Acknowledgments: The present manuscript was derived from a master’s thesis in health education and promotion with the ethical code (IR.QUMS.REC.1402.348). The authors are grateful to the women who participated in the research.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (IR.qhms.rec.14020348). Ethically, participants entered the study with written consent and were assured that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they wished. Moreover, the questionnaires were coded and designed without mentioning names, assuring participants that all their information would be used solely for research purposes and would remain confidential.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Jamei Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (40%); Hosseini F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Mohammadi Zeidi I (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%); Morshedi H (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was conducted with the financial support of the Deputy of Research and Technology of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences.

According to the 2022 report by the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer (BC) is the second most common cancer among women worldwide, with 2.3 million new cases and 670,000 deaths attributed to this disease globally, of which 44.5% of these patients were from Asia. BC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality among women around the world. In Iran, BC is also the most common cancer among women [1]. According to the Globocan report, the estimated number of new BC cases in Iran was 16,967, with 4,810 deaths resulting from this disease in 2020 [2]. Nevertheless, BC is one of the few cancers that can be diagnosed at an early stage and is preventable through screening methods, highlighting the significance of screening programs for the early detection of this disease [3].

Various screening methods for BC include breast self-examination (BSE), clinical evaluation, and various imaging techniques. According to the IraPEN operational guidelines, all women aged 30 to 69 should visit a midwife or physician for clinical breast examinations every one to two years. Additionally, mammography is recommended to be performed annually starting at the age of 40, according to health organization guidelines [4]. Participation in BC screening programs significantly reduces mortality associated with this disease [5, 6]. However, despite the existence of screening guidelines in Iran, women’s participation in regular BC screening remains low. Only 9.9% of women perform BSE, 8.9% undergo clinical breast examinations (CBE), 12.3% have mammograms, and only 3.8% receive sonography regularly [7]. Awareness regarding BC screening plays a crucial role in utilizing related healthcare services in a timely manner for early diagnosis and management [8].

The WHO has identified the enhancement of women’s health literacy (HL) as one of the three main pillars for BC prevention [9]. Accordingly, HL is the focal point for BC screening [10]. HL is defined as “an individual’s ability to obtain and interpret knowledge and information in a way that is appropriate for their circumstances to maintain and improve health” [11]. Higher HL is associated with better health outcomes, and adequate HL is essential for empowering effective decision-making regarding seeking, accessing, and utilizing appropriate health services [12]. According to a study conducted in 2023 aimed at investigating HL levels and cancer screening behaviors among Iranian women, although over 80% of women have adequate HL, only 11.2% undergo mammography, and 73.9% never visit health centers for CBE [13]. Additionally, Momenimovahed et al. report that barriers to mammography among Asian women include personal beliefs, fatalism, fear, pain, embarrassment, religious factors, lack of family support, financial constraints, and certain sociocultural and demographic factors [14].

One effective model for understanding the factors influencing behavior is the health action process approach (HAPA), which has been applied to a wide range of health behaviors, including cancer screening [15]. The main hypothesis of this model is that, for an individual to adopt a behavior, they must progress through two phases: the motivational phase and the volitional phase. The motivational phase includes three factors, namely perceived risk, outcome expectations, and self-efficacy. The volitional phase includes behavioral intention, perceived social support, coping planning, action planning, and perceived barriers [16]. High levels of these factors in both phases contribute to better adherence to health guidelines and increased participation in screenings.

Given that HL is a key element for the early detection of BC and is thus vital for its prevention [9], and considering that primary prevention involves avoiding known risk factors while secondary prevention utilizes various BC screening methods for early identification and timely treatment of the disease—significantly reducing the multiple harms caused by this disease among women—and further noting the limited number of studies on the predictive constructs of the HAPA model in adopting BC screening behaviors among women, the present study aimed to investigate the role of HL and the HAPA model in predicting the adoption of BC screening behaviors in women.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was conducted on 350 women aged 30 to 69 years selected from the population served by comprehensive health centers in Alborz city, Qazvin Province, Iran in 2024.

Inclusion criteria included providing informed consent to participate, Iranian citizenship, having an active file in comprehensive health centers, literacy in reading and writing, no history of BC or other cancers, and being within the age range of 30 to 69 years. Exclusion criteria included a lack of willingness to participate in the study and incomplete questionnaires.

The sample size was determined based on a similar study [17], considering a 95% confidence level, with d=4.5 and S=36.1, resulting in a total of 350 participants. The sampling method used was multi-stage cluster sampling. The Alborz City was first divided into five geographical areas, namely north, south, east, west, and central. Then, using a list of urban comprehensive health centers in each area, two centers were randomly selected from each section (for a total of ten centers) through simple random sampling. Subsequently, women who met the inclusion criteria were sampled using a convenience sampling approach.

Data collection

The data collection tool was designed in four main sections, including a demographic and background information questionnaire, which included eight questions related to age, marital status, occupation, insurance status, educational level, spouse’s educational level, financial status, and family history of BC.

Health Literacy for Adults-Short Form (HELIA-SF): This questionnaire was developed by Tavousi et al. [18] in 2022 and consists of nine questions with two constructs, namely basic skills (five items) and decision-making skills (four items). Scoring was based on a five-point Likert scale (one=not sure to five=very sure), with total scores ranging from 9 to 45. For all items, the content validity ratio (CVR) was greater than 0.56, the content validity index (CVI) was greater than 0.79, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were 0.91 and 0.81, respectively.

Awareness questions: These questions measured women’s awareness regarding BC, the risk factors of the disease, and how to perform and when to conduct screening tests. They included eight true/false questions, scored as correct (one point) and incorrect (zero points), with total scores ranging from zero to eight. Awareness scores were categorized as 0-3=poor, 4-6=moderate, and 7-8=good. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for awareness in this study was 0.735.

A researcher-developed questionnaire related to the HAPA: This questionnaire consisted of 55 items covering constructs, such as perceived risk, outcome expectations, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, action planning, coping planning, perceived social support, behavioral intention, and screening behaviors (BSE, CBE, and mammography). Following the design and psychometric process (face/content validity and reliability), it was utilized in the current research. The questionnaire included one reverse-scored question in the self-efficacy construct, and scoring was based on a five-point Likert scale from completely disagree (one point) to completely agree (five points). To assess the screening behavior of women, three questions were scored as never (zero points), within one year (one point), within two years (two points), and three years or more (three points), with total scores ranging from 55 to 269. For the quantitative assessment of content validity, a panel of eight experts—including four health education specialists, two midwives, and two physicians—was requested to evaluate each item based on a three-part scale (not relevant, useful but not essential, and essential) and three criteria: relevance, clarity, and simplicity, using specialized worksheets. Accordingly, the overall CVR and CVI values for awareness were calculated as 0.90 and 0.95, respectively, while for the HAPA, they were 0.89 and 0.96. Additionally, to assess face validity, interviews were conducted in person with ten women who met the eligibility criteria, gathering their opinions regarding the difficulty level, appropriateness, and ambiguity of each item. To determine the internal consistency of items within each dimension, the questionnaire was administered to 30 eligible women, yielding Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the constructs of the HAPA model ranging from 0.714 to 0.893 (Table 1).

Table 1. Constructs of the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) and Awareness Scale

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to describe the data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess data normality, the Spearman correlation coefficient to assess the relationships, and multiple regression analysis predicted screening behaviors.

Findings

Among the 350 participants, the mean age of the women was 44.73±10.22 years. The mean scores for the awareness and HL of the participating women were 3.97±2.03 and 29.54±7.55, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) constructs and demographic characteristics of participants (n=350)

The results of the Spearman correlation coefficient demonstrated a significant positive correlation between the constructs of outcome expectations, self-efficacy, action planning, behavioral intention, perceived risk, social support, coping planning, HL, and screening behavior (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations among HAPA constructs’ scores and HL in participants (n=350)

The constructs of perceived risk, perceived barriers, and coping planning accounted for 24% of the variance in screening behavior. Specifically, for each standard deviation increase in the perceived risk score, the coping planning and screening behavior scores increased by 0.28 and 0.18 standard deviations, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Regression findings for the prediction of behavior

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of HL and the HAPA in predicting BC screening behaviors among Iranian women. The awareness of the participating women regarding BC screening, particularly concerning the appropriate timing for breast examinations and the age to begin such screening behaviors, was at a weak level. High awareness helps women make better decisions regarding medical examinations. In Iran, the lack of structured intervention programs for health education in the community and the absence of regular screening programs have resulted in a low level of awareness and attitudes about cancers, especially BC. This issue has led to a decrease in the willingness of Iranian women to adopt preventive and diagnostic methods for BC, particularly BSE, ultrasound, and mammography. Results from several studies conducted in Iran indicate low awareness levels in this regard among Iranian women [19, 20]. Awareness and knowledge are considered essential components of any behavior change and serve as fundamental prerequisites for behavioral change. Their absence can lead to a lower willingness to engage in preventive behaviors [21].

The likelihood of women undergoing BC screening tests was lower among those with low HL and awareness; this is consistent with the results of several studies [22, 23]. These findings highlight the importance of HL in the timely and effective execution of BC screening tests. Women with higher HL not only have a better awareness of the importance of screening but also possess a better understanding of how to perform it. High HL enables women to accurately interpret information about BC screening and to engage more effectively with health professionals, asking more pertinent questions and receiving more precise information. Therefore, educational interventions focusing on enhancing HL and specialized knowledge concerning BC can lead to increased screening behaviors.

There was a significant correlation between the constructs of the HAPA and the performance of behaviors. Secondly, the constructs of perceived risk, perceived barriers, and coping planning were able to predict 24% of the variance in behavioral performance. Moreover, according to Parschau et al. [24] and Mohammadi Zeidi et al. [25], these constructs respectively explain 18% and 32% of the variance in behavior based on this model.

The construct of perceived risk was a significant motivational predictor for adopting screening behaviors. Specifically, for each standard deviation increase in the perceived risk score, the behavior score increased by 0.28 standard deviations. The level of perceived risk among women increases with age, and younger women often view their young age as a convincing argument against having BC. It is recommended that through education and increasing awareness, attitudes should be changed, regular examinations encouraged, and support provided for this group, so that individuals’ perceptions of the risk of developing BC are somewhat heightened. Conversely, the findings from Satoh & Sato indicate the perceived risk’s inability to motivate the use of BC screening methods [26], highlighting the need for further research in this area.

Perceived barriers play a crucial role in women’s decision-making regarding participation in BC screening programs across various dimensions. For instance, in the present study, as found in the research by Hossaini et al. and Ramezankhani et al. [27, 28], many women expressed significant concerns about the potential consequences of test results, the high costs of screening services, the belief that mammography is painful, embarrassment from examinations, the notion of fate and destiny, busy schedules, and inadequate access to reputable diagnostic centers. These were the main barriers identified by women that could discourage them from undergoing regular screening. Analysis of these barriers indicates that to promote the level of BC screening, it is necessary to design educational and supportive programs that specifically enhance awareness about the importance of screening, reduce fears, and create a supportive environment to encourage women to take effective actions concerning their health screening.

The third predictor of BC screening behaviors was coping planning. Coping planning is a self-regulatory strategy that anticipates challenging situations that may deter an individual from performing the desired behavior and plans to overcome barriers that may hinder behavioral performance [29, 30]. Individuals who were able to plan effectively to cope with potential barriers to BC screening behaviors and had specific strategies to overcome these barriers were more likely to commit to screening behaviors. This type of planning becomes particularly significant when women are faced with potential threats, and each of these two (planning and coping) can effectively impact the improvement of cancer screening behaviors, which is supported by the findings of the study by Bianchi et al. [31].

This study offers valuable insights into the roles of HL and the HAPA in influencing BC screening behaviors among Iranian women. However, limitations, such as the cross-sectional design, hinder our ability to establish causal relationships, and reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to better capture the evolving dynamics of health-seeking behaviors and assess intervention effectiveness.

In light of these findings, targeted interventions are proposed to enhance HL and improve BC screening rates. Culturally sensitive health education initiatives should be implemented through community health centers, schools, and online platforms, emphasizing the importance of BC screening. Additionally, skill-building workshops can empower women with practical skills for BSE and mammography procedures, boosting their confidence in seeking screenings. Establishing support groups will provide necessary safe spaces for women to discuss their concerns, fostering peer support and normalizing cancer-related conversations. Moreover, tailored communication strategies should ensure that information about screening accessibility and procedures is clear and understandable.

By addressing these areas, we can work towards improving BC screening rates among Iranian women, leading to earlier detection and better health outcomes. The implications of this study extend beyond Iran, highlighting the critical need for heightened awareness and proactive health-seeking behaviors globally within cancer prevention efforts.

Conclusion

The HAPA enhances women’s participation in BC screening.

Acknowledgments: The present manuscript was derived from a master’s thesis in health education and promotion with the ethical code (IR.QUMS.REC.1402.348). The authors are grateful to the women who participated in the research.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (IR.qhms.rec.14020348). Ethically, participants entered the study with written consent and were assured that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they wished. Moreover, the questionnaires were coded and designed without mentioning names, assuring participants that all their information would be used solely for research purposes and would remain confidential.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Jamei Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (40%); Hosseini F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Mohammadi Zeidi I (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%); Morshedi H (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was conducted with the financial support of the Deputy of Research and Technology of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Literacy

Received: 2025/03/3 | Accepted: 2025/05/8 | Published: 2025/05/12

Received: 2025/03/3 | Accepted: 2025/05/8 | Published: 2025/05/12

References

1. WHO. Cancer today [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2024 May 23]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en/dataviz/tables?mode=population&cancers=20&group_populations=0&multiple_populations=1. [Link]

2. WHO. Iran, Islamic republic of. Number of new cases in 2020, both sexes, all ages. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

3. Duffy SW, Vulkan D, Cuckle H, Parmar D, Sheikh S, Smith RA, et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): Final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(9):1165-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30398-3]

4. WHO. The collection of basic interventions of non-communicable diseases in Iran's primary health care system "IraPEN". Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Link]

5. Henderson JT, Webber EM, Weyrich MS, Miller M, Melnikow J. Screening for breast cancer: Evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2024;331(22):1931-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2023.25844]

6. US Preventive Services Task Force; Nicholson WK, Silverstein M, Wong JB, Barry MJ, Chelmow D, et al. Screening for breast cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2024;331(22):1918-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2024.5534]

7. Seyedkanani E, Hosseinzadeh M, Mirghafourvand M, Sheikhnezhad L. Breast cancer screening patterns and associated factors in Iranian women over 40 years. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15274. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-66342-0]

8. Portelli Tremont JN, Downs-Canner S, Maduekwe U. Delving deeper into disparity: The impact of health literacy on the surgical care of breast cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):806-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.05.009]

9. WHO. WHO launches new roadmap on breast cancer [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-02-2023-who-launches-new-roadmap-on-breast-cancer. [Link]

10. Liu C, Wang D, Liu C, Jiang J, Wang X, Chen H, et al. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(2):e000351. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/fmch-2020-000351]

11. Nie X, Li Y, Li C, Wu J, Li L. The association between health literacy and self-rated health among residents of China aged 15-69 years. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(4):569-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.032]

12. Rutan MC, Sammon JD, Nguyen DD, Kilbridge KL, Herzog P, Trinh QD. The relationship between health literacy and nonrecommended cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(2):e69-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.018]

13. Rakhshani T, Khiyali Z, Mirzaei M, Kamyab A, Jeihooni AK. Health literacy and breast and cervical cancer screening behaviors in women. J Educ Community Health. 2023;10(2):87-92. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/jech.2023.A-10-110-16]

14. Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Hassanipour S, Salehiniya H. A review of barriers and facilitators to mammography in Asian women. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1146. [Link] [DOI:10.3332/ecancer.2020.1146]

15. Pourhaji F, Delshad MH, Pourhaji F, Ghofranipour F. Application of the health action process approach model in predicting mammography among Iranian women [Preprint]. 2021 [cited 2025 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-80108/v1. [Link] [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-80108/v1]

16. Malik K, Amir N, Kusumawardhani AAAA, Lukman PR, Karnovinanda R, Melisa L, et al. Health action process approach (HAPA) as a framework to understand compliance issues with health protocols among people undergoing isolation at emergency hospital for COVID-19 Wisma Atlet Kemayoran and RSCM Kiara Ultimate Jakarta Indonesia. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:871448. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.871448]

17. Rakhshkhorshid M, Navaee M, Nouri N, Safarzaii F. The association of health literacy with breast cancer knowledge, perception and screening behavior. Eur J Breast Health. 2018;14(3):144-7. [Link] [DOI:10.5152/ejbh.2018.3757]

18. Tavousi M, Haeri-Mehrizi AA, Sedighi J, Montazeri A, Mohammadi S, Ardestani MS, et al. Health literacy instrument for adults-short form (HELIA-SF): Development and psychometric properties. PAYESH. 2022;21(3):309-19. [Persian] [Link]

19. Masoudi N, Dastgiri S, Sanaat Z, Abbasi Z, Dolatkhah R. Barriers to breast cancer screening in Iranian females: A review article. UNIVERSA MEDICINA. 2022;41(1):79-89. [Link] [DOI:10.18051/UnivMed.2022.v41.79-89]

20. Emami L, Ghahramanian A, Rahmani A, Mirza Aghazadeh A, Onyeka TC, Nabighadim A. Beliefs, fear and awareness of women about breast cancer: Effects on mammography screening practices. Nurs Open. 2021;8(2):890-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nop2.696]

21. Ramezanpoor M, Taghipour A, Vahedian Sharody M, Tabesh H. The effectiveness of an educational intervention based on social cognitive theory on fruit and vegetable intake in pregnant women. PAYESH. 2019;18(4):381-91. [Persian] [Link]

22. Kiracılar E, Koçak DY. The effects of health literacy on early diagnosis behaviors of breast and cervical cancer in women aged 18-65. J Contemp Med. 2023;13(3):410-7. [Link] [DOI:10.16899/jcm.1210914]

23. Poon PK, Tam KW, Lam T, Luk AK, Chu WC, Cheung P, et al. Poor health literacy associated with stronger perceived barriers to breast cancer screening and overestimated breast cancer risk. Front Oncol. 2023;12:1053698. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fonc.2022.1053698]

24. Parschau L, Barz M, Richert J, Knoll N, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Physical activity among adults with obesity: Testing the health action process approach. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(1):42-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0035290]

25. Mohammadi Zeidi I, Morshedi H, Shokohi A. Application of the health action process approach (HAPA) model to determine factors affecting physical activity in hypertensive patients. J Jiroft Univ Med Sci. 2020;7(2):349-60. [Persian] [Link]

26. Satoh M, Sato N. Relationship of attitudes toward uncertainty and preventive health behaviors with breast cancer screening participation. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):171. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12905-021-01317-1]

27. Hossaini F, Akbari ME, Soori H, Ramezankhani A. Perceived barriers to early detection of breast cancer in Iranian women: A qualitative content analysis. Int J Cancer Manag. 2020;13(9). [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijcm.101467]

28. Ramezankhani A, Akbari ME, Soori H, Ghobadi K, Hosseini F. The role of the health belief model in explaining why symptomatic Iranian women hesitate to seek early screening for breast cancer: A qualitative study. J Cancer Educ. 2023;38(5):1577-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13187-023-02302-y]

29. Pakpour AH, Lin CK, Safdari M, Lin CY, Chen SH, Hamilton K. Using an integrated social cognition model to explain green purchasing behavior among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23):12663. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182312663]

30. Zhang CQ, Fang R, Zhang R, Hagger MS, Hamilton K. Predicting hand washing and sleep hygiene behaviors among college students: Test of an integrated social-cognition model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1209. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17041209]

31. Bianchi M, Capasso M, Donizzetti AR, Caso D. Navigating women's cancer prevention: Two cross-sectional studies to investigate psychosocial antecedents of cervical and breast cancer screening attendance. J Health Psychol. 2024:13591053241295895. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/13591053241295895]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |