Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 155-161 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ahmadi Hedayat M, Khoobi M, Anisiyan A. Effect of Implementing the Patient Safety Friendly Hospital Initiative on Patient Safety Culture. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :155-161

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79302-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79302-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Ebne Sina Hospital, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Immunology, Ebne Sina Hospital, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Immunology, Ebne Sina Hospital, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 626 kb]

(324 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (526 Views)

Full-Text: (44 Views)

Introduction

The patient safety friendly hospital initiative (PSFHI) is a program designed to enhance patient safety by prioritizing it as a fundamental aspect of hospital practices. It can be conceptualized as a gesture of care and consideration by the healthcare sector toward its patients, signifying a commitment to ensuring their well-being beyond the mere objective of expeditious discharge.

Patient safety has always been a primary concern for healthcare systems worldwide and is consistently the focus of researchers and experts in the health field. In recent years, the maintenance and promotion of health have emerged as paramount objectives within healthcare systems [1]. This emphasis is based on the recognition that enhancing health is instrumental in fostering the quality of health and medical services. Consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has acknowledged the significance of patient safety and has designated World Patient Safety Day to raise awareness and promote initiatives aimed at enhancing patient safety [2].

The WHO has identified the necessity of a comprehensive approach to patient safety that encompasses implementing changes in safety culture, system development, and professional development [3]. In recent years, the WHO has formulated standards for promoting a patient safety culture to address patient safety issues and provide safer services, with the expectation of reducing patient safety errors [3]. The WHO shares these safety-friendly hospital standards annually with patient safety experts around the world [4].

The results showed that the number of hospitalizations in low- and middle-income countries reached 134 million, leading to 2.6 million deaths [1, 4]. In high-income countries, nearly one in ten patients experiences harm during hospital care [5].

Research has demonstrated that 4 to 17% of patients encounter complications attributable to substandard safety practices, with more than half of these incidents being preventable [6]. In a study by Ilmidin & Ningsih, patient safety culture is reported to have an average score of 53.18% across seven countries (China, Ethiopia, USA, Philippines, Iran, Indonesia, and Ghana) and states [7]. In Iran, there is an absence of documented statistics concerning medical and nursing errors related to patient safety. However, the increasing number of complaints referred to the Medical System Organization suggests that the rate of these errors is likely high [4]. The confirmation of these errors would not only lead to mortality and disability but would also generate substantial financial burdens for the health system [8]. The WHO acknowledges the significance of patient safety and has identified it as a pressing public health issue. The World Health Assembly resolution delineates the organization’s manifold responsibilities, which encompass providing technical assistance to member states for the development of reporting and risk reduction systems, formulating evidence-based policies, promoting a safety culture, and encouraging research into patient safety [9]. This program is so important that it is considered one of the key interventions of the WHO in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Its main objective is to promote patient safety as an important principle for maintaining the quality of health services, taking into account the empowerment of hospitals and staff in providing safe services, with the active participation of patients and the community in promoting health safety [10]. The PSFHI creates a set of patient safety standards and tools to evaluate hospital patient safety programs and instill a culture of safety [11].

The patient safety-friendly hospital standards consist of a total of 140 items divided into the following five groups: Governance and Leadership Group with 36 standards, Patient and Community Involvement and Engagement Group with 28 standards, Safe and Evidence-Based Clinical Services Group with 44 standards, Safe Environment Group with 21 standards, and finally, Education Group with 11 standards. Therefore, each of the five groups is further divided into subgroups, which contain a total of 24 subgroups. Each subgroup includes three sets of standards, including mandatory, basic, and advanced. Mandatory standards are those that must be fully met for hospitals to be recognized as patient safety friendly [12]. The core Standards represent a set of requirements essential for implementing a hospital-wide patient safety program. They provide an operational framework that enables hospitals to evaluate patient care from a patient safety perspective, build staff capacity in this area, and engage patients in improving patient safety [13].

The advanced safety friendly hospital Standard is implemented after the attainment of the preceding two levels and encompasses criteria that not only facilitate the enhancement of service quality and the augmentation of patient safety but also fortify and preserve the delivery of safe services [14].

Contemporary literature on the effectiveness of implementing safety-friendly hospital standards on patient safety culture has yielded conflicting results. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is that hospitals possess unique circumstances and cultures, which must be taken into consideration during the design of processes aimed at achieving patient safety goals [1, 7, 14].

In the study by Camacho-Rodríguez et al., the safety status of patients varies significantly, and more efforts should be made to examine this status more precisely [15]. In a subsequent study by Ahmed et al., on the safety status of patients in hospitals, the safety status in the units studied is not satisfactory [16].

The implementation of a patient safety assessment has been demonstrated to benefit hospitals and society. This assessment serves as a crucial instrument for hospitals to demonstrate their commitment and accountability to patient safety. It functions as a key tool for modeling, identifying weaknesses, and encouraging improvement toward achieving standard goals. Ultimately, it serves to motivate staff to participate in improving patient safety. The assessment’s ultimate objective is to enhance the level of patient safety within the hospital and to create conditions that lead to safer services. This, in turn, helps protect the community from avoidable harm and reduces adverse events in the hospital environment. In light of these considerations, the present study aimed to examine the impact of implementing patient safety-oriented hospital standards on patient safety culture at Ebne Sina Hospital in 2024.

Instruments and Methods

Study design

This interventional study utilized a pre-post intervention design (single-group design) to evaluate the effect of the PSFHI on patient safety culture among nurses. The study was longitudinal, consisting of three assessment points, including baseline assessment (T0; administered before the education intervention (pre-test), post-education assessment 1 (T1; conducted immediately after the completion of the education intervention (post-test one), and post-education assessment 2 (T2; administered three months after the education intervention (post-test two).

Setting and sample size

The study was conducted at Ebne Sina Hospital and its population comprised all nurses currently employed at the hospital selected using census method. After obtaining the code of ethics from Tarbiat Modares University, informed consent was obtained by explaining the research objectives. A total of 420 nurses participated in the study; however, five participants were excluded from the final analysis because they changed their work environment during the study period, resulting in a final sample size of 415 nurses.

The inclusion criteria were nurses with at least six months of work experience in the hospital or its clinics, and nurses with direct responsibility for patient care. The exclusion criteria included nurses who did not participate in at least two educational sessions and nurses who did not complete the questionnaires.

The intervention consisted of a comprehensive education program on the PSFHI, conducted over six months, from September 22, 2024, to March 20, 2025. The education program covered key components of patient safety, including communication, error reporting, and teamwork. Educational materials were presented through oral presentations, workshops, and interactive sessions in the hospital’s education room.

The primary outcome was the change in patient safety culture scores between T0 and T1, as well as between T0 and T2. Patient safety culture was assessed using a standardized questionnaire developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture), which was administered at each assessment point. This scale comprises 12 dimensions with a total of 42 items, measured by the researcher using a Likert scale ranging from one to five points, indicating levels of agreement to disagreement. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been found to be acceptable in the study by Palmieri et al. [17].

Statistical analysis

The reliability was measured on 25 nurses, with a correlation coefficient of r=0.9. The distribution of samples was normal. Demographic information, such as age and years of experience, was collected during the pre-education assessment. Data were collected at three time points; before the education intervention (T0), immediately after the final education session (T1), and three months after the first post-test (T2). Of the 415 participants who completed the education program, all filled out the patient safety culture scale at T1 and T2. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics and patient safety culture scores. Paired t-tests were employed to compare the scores between T0 and T1. Additionally, Bonferroni tests were conducted to compare the scores between T0 and T1, as well as between T0 and T2. The methods and results are presented in accordance with CONSORT guidelines to ensure clarity and transparency. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20, employing descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, independent t-test, and one-way ANOVA.

Findings

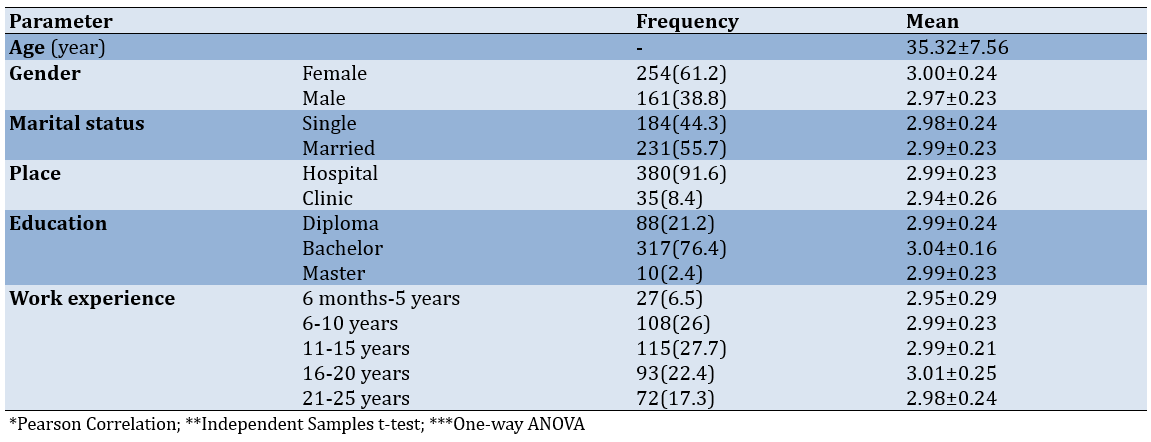

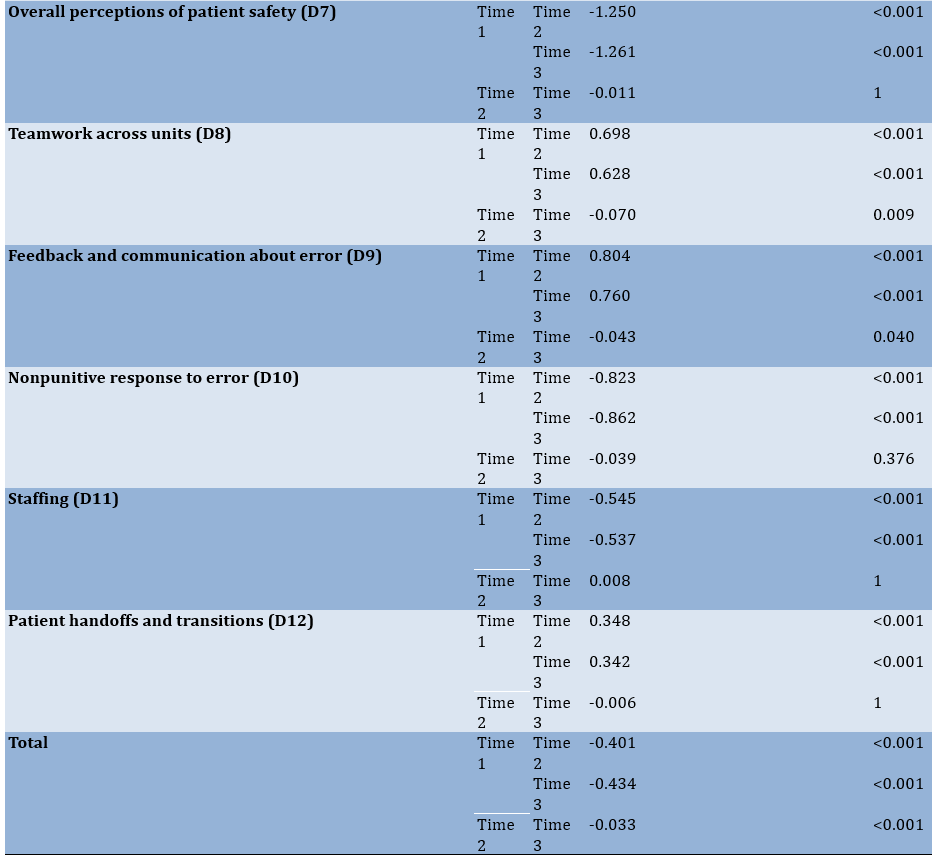

No significant relationship was observed between demographic parameters and patient safety culture. The analyses indicated that there was no significant relationship between any of the demographic parameters including age, gender, martial status, workplace, educational level and work experience with patient safety culture. The statistical tests employed (Pearson correlation, independent t-test and one-way ANOVA) also revealed no significant differences among the groups. (Table 1).

Table 1. Relationship between demographic parameters and patient safety culture

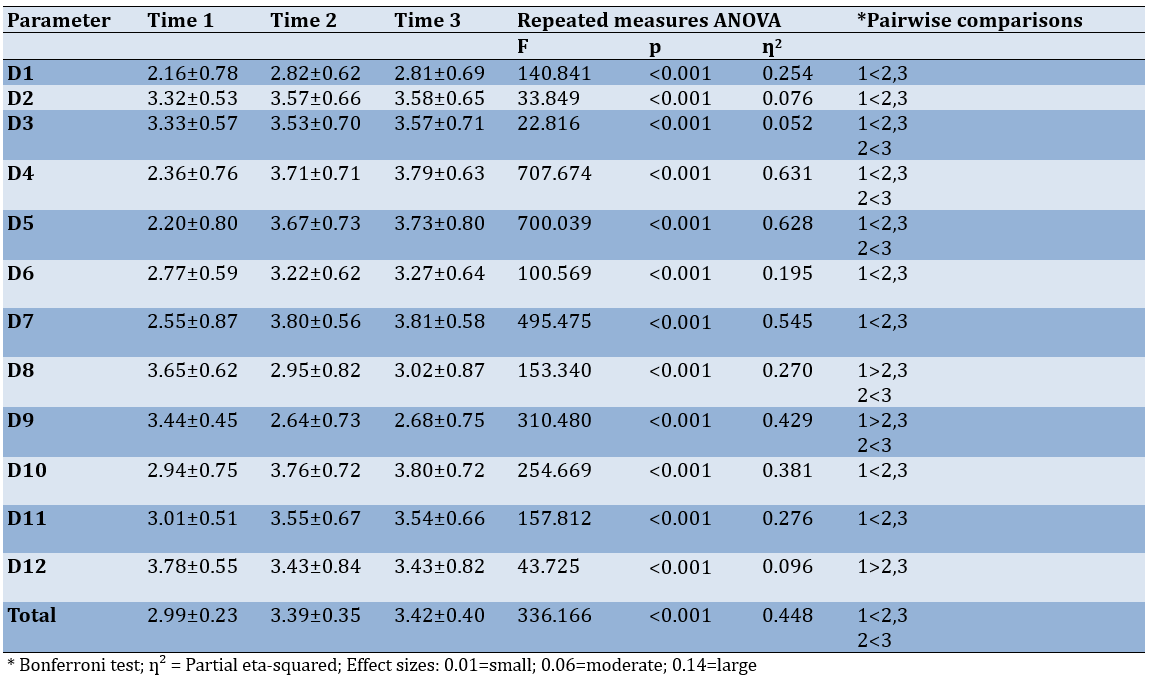

The nurses’ responses to the patient safety culture questionnaire were positive with a statistically significant difference observed, indicating that the PSFHI training was effective in improving patient safety culture.

A total of 12 dimensions (D1-D12), reflecting various aspects of safety culture, were assessed. These dimensions represented nurses’ perceptions of safety culture changes throughout the intervention period.

Statistical analysis revealed significant improvements in patient safety culture scores over time (p-values<0.001). Notably, for Dimension 1 (D1), the mean score demonstrated considerable enhancement, with pairwise comparisons showing significant differences between T1 and T2 (mean difference=-0.663; p<0.001) and sustained improvements between T1 and T3. This trend was consistent across other key dimensions, such as D2, D4, and D5, which also exhibited marked improvements in safety culture scores between T1 and T2.

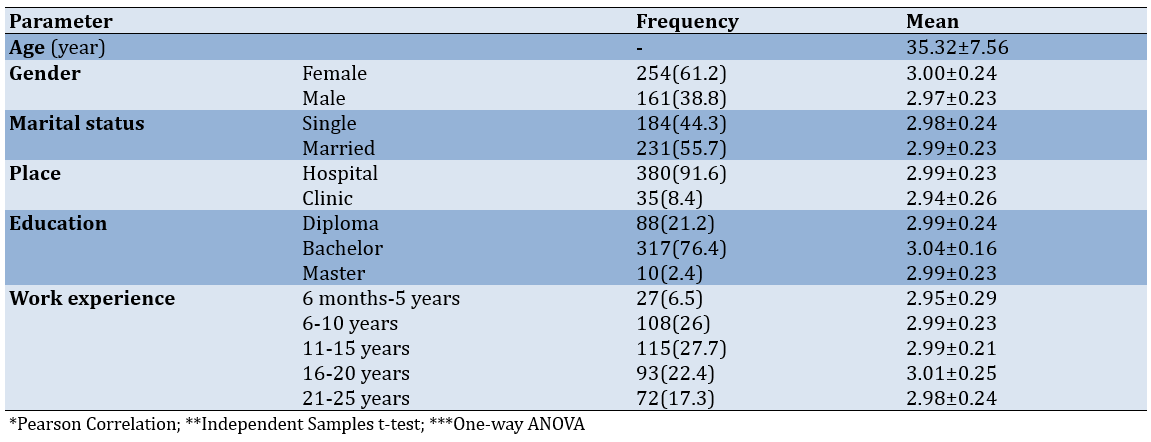

The effect of the initiative on patient safety culture was evident. The repeated measures ANOVA results showed statistically significant differences in safety culture scores across the three time points (p-value<0.001). This suggests strong evidence to conclude that the implementation of the PSFHI significantly improved the patient safety culture among nurses when comparing the scores from T1 to T2 and T3. The post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated which specific time comparisons were significant. For instance, for D1, the means demonstrated notable improvements from T1 to T2 and from T1 to T3, with the differences being significant (p<0.001). This suggests measurable improvements in safety practices due to education and the initiative as time progresses (Table 2).

Table 2. Effect of the initiative on mean patient safety culture score at three time points (before and two after))

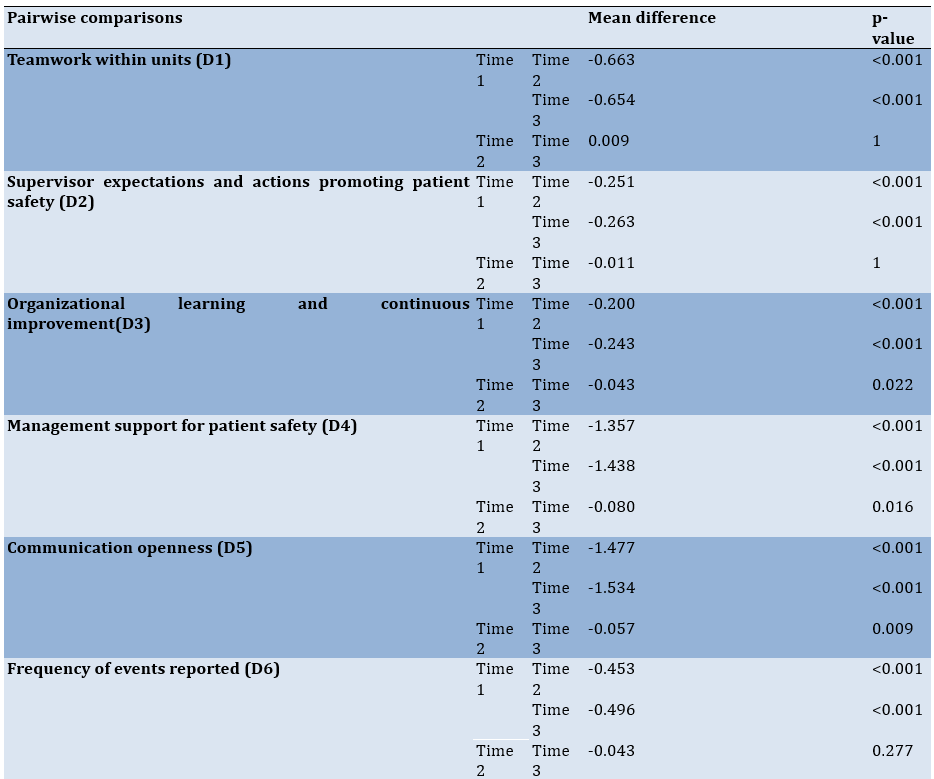

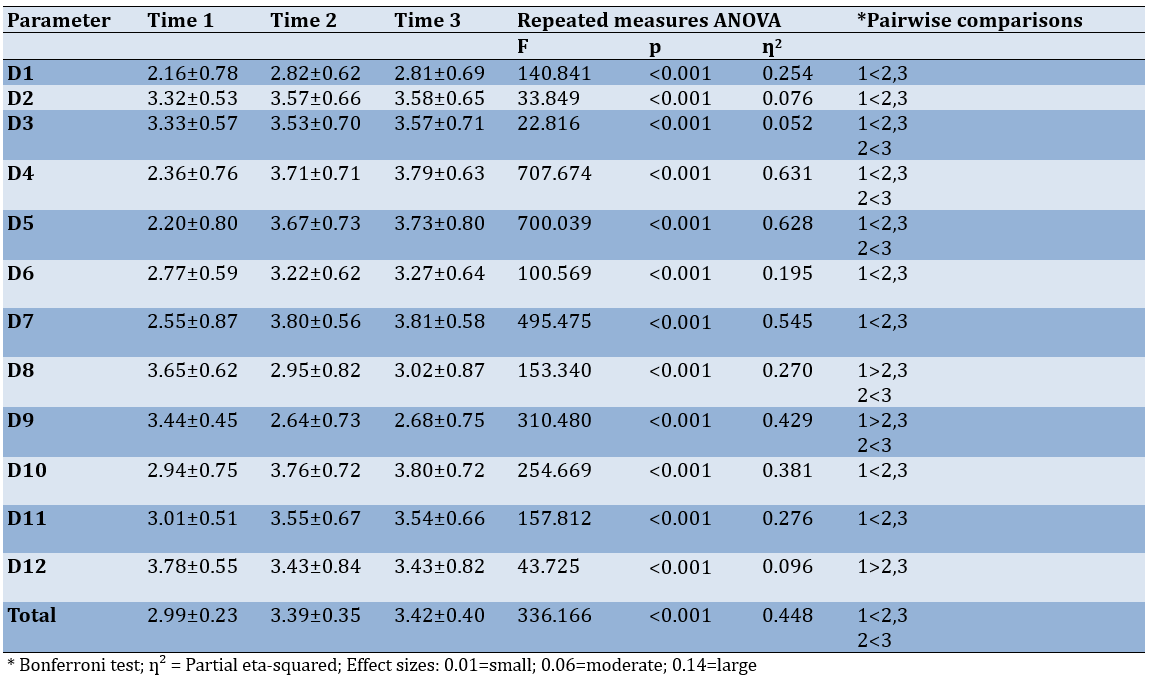

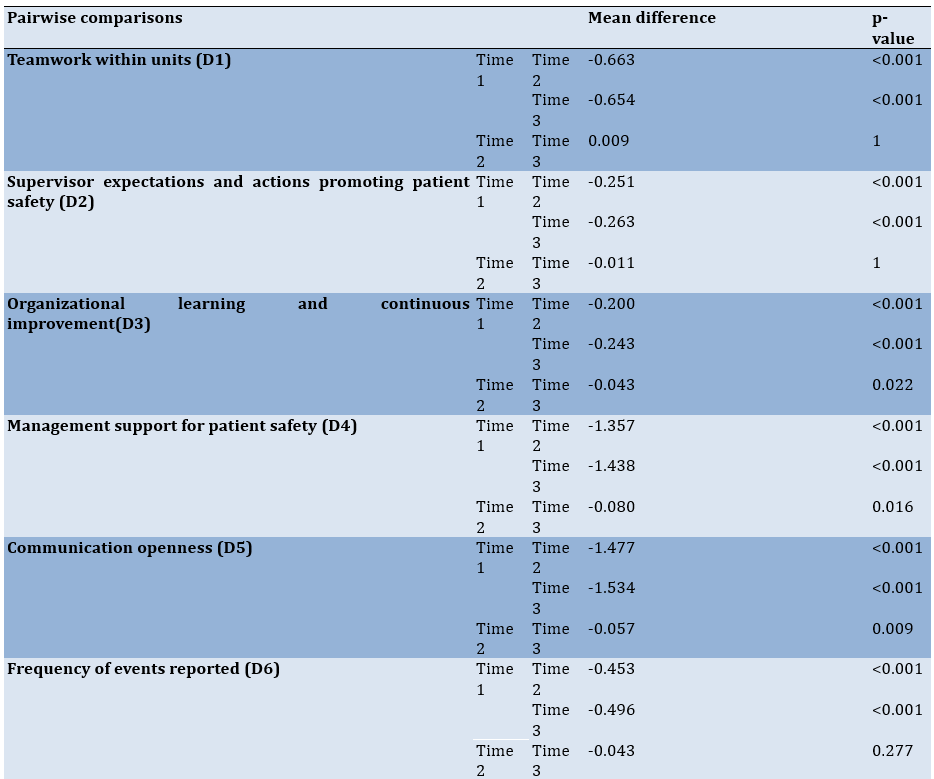

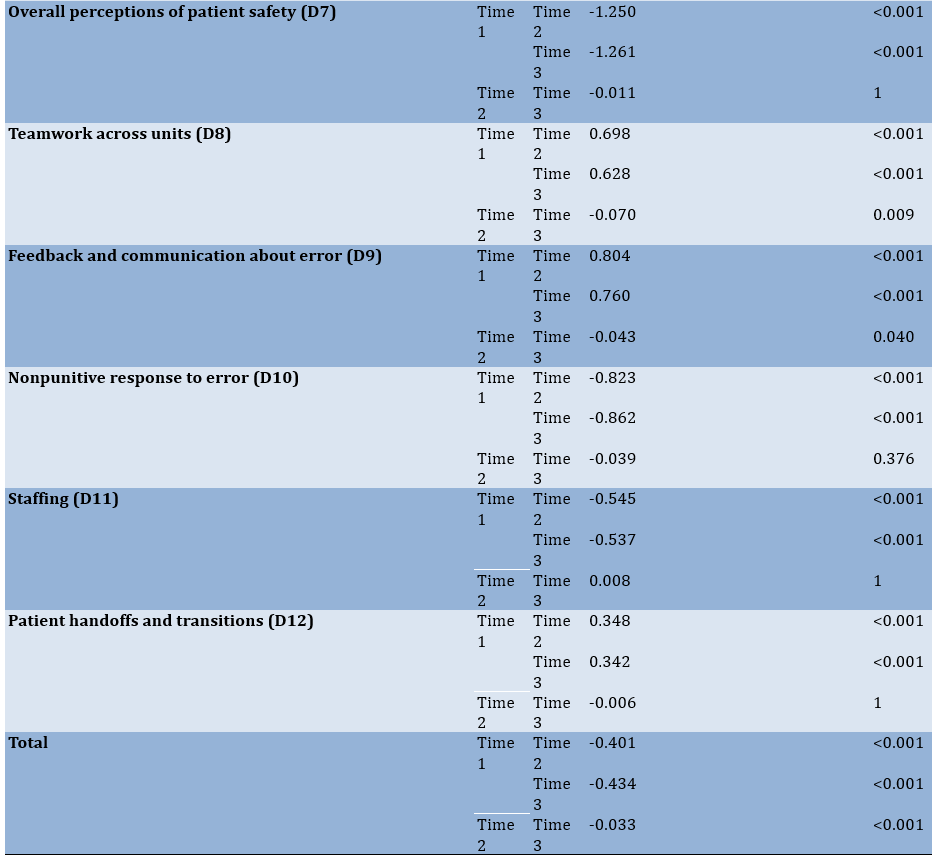

In the dimensions of D1, D2, D4, and D5, each of these dimensions showed significant differences between T1 and T2, indicating improvements in safety culture scores. For instance, for D1, the mean difference between T1 and T2 was -0.663 (p<0.001), suggesting significant improvement. The results demonstrated statistically significant improvements across the three time points (T1, T2, and T3) (p<0.001), indicating strong evidence of the initiative’s effectiveness (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean differences in 12 dimensions

Discussion

This interventional study evaluated the impact of implementing the PSFHI on patient safety culture among nurses at Ebne Sina Hospital. We aimed to determine whether the PSFHI could significantly improve safety culture dimensions, as assessed by nurses, following the intervention.

Significant improvements were observed in teamwork within units (D1), suggesting enhanced collaboration and mutual support among nurses after education. This finding is consistent with Tveter Deilkås, reporting similar enhancements in teamwork following a patient safety initiative [18]. Although there was a statistically significant improvement in teamwork within units, some studies, such as Alharbi et al., have reported minimal changes in this dimension. This discrepancy may be due to differences in intervention intensity or baseline teamwork levels [19].

Supervisors’ role in promoting patient safety (D2) showed marked improvement. The structured education sessions empowered supervisors to better communicate and enforce safety standards, aligning with findings by Siddiqi et al., emphasizing the critical role of leadership in patient safety culture [20]. In the study by Namnabati et al., supervisory actions do not always translate into perceived safety improvements, suggesting variability in supervisory effectiveness and methods of supervision [21].

The education of patient safety initiatives fostered a culture of continuous learning and improvement (D3). Nurses became more proactive in identifying and addressing safety issues, consistent with the results of Namnabati et al., highlighting the importance of ongoing education in enhancing safety culture. However, González-Formoso et al. reported that continuous improvement in patient safety education does not always lead to perceived changes in safety culture, highlighting possible differences in organizational commitment and management [22].

Regarding the next dimension of the questionnaire, management support (D4) saw a notable boost, underscoring the importance of leadership commitment in fostering a safety culture. Opal Malone et al. have found similar results, indicating that visible support from management can significantly impact perceptions of safety culture [23]. It seems that managerial support leads to improved open communication, with nurses feeling more comfortable discussing safety concerns. This aligns with the findings of Christmals & Gross, noting that open communication is vital for an effective safety culture [24].

The frequency of event reporting (D6) increased after the education on patient safety, suggesting that nurses became more diligent in reporting errors and near misses [25]. However, unlike our findings, Wijenayake et al. have observed less pronounced changes in reporting frequency [26], highlighting the variability in intervention outcomes across different settings.

Another important dimension that increased after education was the holistic perception of nurses (D7), reflecting a more positive outlook on safety practices. This is consistent with Ali et al., reporting enhanced perceptions of safety following targeted interventions [27]. When nurses’ overall understanding of the concept of safety culture increases, inter-team collaboration also improves.

Our results showed moderate improvement in teamwork across units (D8), indicating better collaboration beyond individual units. Damayanti & Bachtiar found that interdisciplinary teamwork is crucial for a cohesive safety culture, supporting our findings [28].

Nurses’ feedback on errors (D9) improved after receiving periodic training, and one of the reasons for this may be the elimination of punishment when errors occur. Improvements in feedback and communication about errors suggest a more supportive environment for discussing and learning from mistakes. This aligns with Brodersen, emphasizing the role of constructive feedback in safety culture [29].

When non-punitive responses (D10) are given to nurses, they feel less fear of reprimand. However, Christmals & Gross have observed less pronounced improvements in this dimension [24], indicating potential variability in intervention effectiveness. Additionally, González-Formoso et al. have noted minimal changes [22], suggesting that creating a non-punitive culture may require more time and effort.

Staffing issues (D11) were perceived more positively after the intervention, and nurses felt better supported. Sheridan et al. found that adequate staffing is a key factor in maintaining a safe environment for patients [30], which is consistent with our findings. However, Opal Malone et al. have reported no significant change in their study results [23]. This discrepancy could be because, in Opal Malone et al.’s study, the hospital is facing a nursing shortage, while in our study, there was no shortage of nurses, and nurses were not forced to work extra shifts.

Regarding the last dimension of the patient safety culture questionnaire, patients’ handoffs and transitions (D12) saw notable improvements, enhancing the continuity of patient safety. This dimension aligns with Ahmed et al., highlighting the importance of effective transfer in ensuring patient safety [16].

The implementation of the PSFHI led to statistically significant improvements across multiple dimensions of patient safety culture, including teamwork, supervisory roles, communication, event reporting, and staff perceptions. These findings underscore the importance of structured interventions, continuous education, and leadership support in fostering a culture of safety within hospitals.

The PSFHI offers a valuable framework for other healthcare institutions aiming to enhance patient safety culture. However, the variability in outcomes reported across studies highlights the importance of tailoring interventions to specific organizational contexts and baseline conditions. Future research should focus on the long-term sustainability of these improvements, exploring which components of the PSFHI are most impactful. Additionally, comparative studies across diverse healthcare settings can provide further insights into the generalizability and adaptability of this model. Due to the absence of a control group, we cannot directly compare the intervention group with a non-intervention group.

We firmly advocate for implementing educational strategies that are based on solid evidence to enhance both patient care and the learning outcomes for nurses. Our research shows that specific teaching techniques and practical approaches in clinical settings significantly improve performance. This insight can help shape educational programs and enhance nursing competencies. Adopting this approach not only validates the effectiveness of our training methods but also encourages ongoing research to refine optimal practices in nursing. Ultimately, this will lead to improved patient care outcomes and support the professional development of nurses, contributing to a higher standard of patient safety.

Conclusion

The implementation of safety standards has benefits for hospitals and society by enhancing patient safety and reducing adverse events.

Acknowledgments: This research is part of the joint cooperation project between Tarbiat Modares University of Tehran and the industry (Ebne Sina Hospital, Tehran). The researchers of this study would like to thank all the participants.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University authorized the research protocol (Register number: IR.MODARES.REC.1402.076).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests regarding the present paper.

Authors' Contribution: Ahmadi Hedayat M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (25%); Khoobi M (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (50%); Anisiyan A (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Tarbiat Modares University and Ebne Sina Hospital.

The patient safety friendly hospital initiative (PSFHI) is a program designed to enhance patient safety by prioritizing it as a fundamental aspect of hospital practices. It can be conceptualized as a gesture of care and consideration by the healthcare sector toward its patients, signifying a commitment to ensuring their well-being beyond the mere objective of expeditious discharge.

Patient safety has always been a primary concern for healthcare systems worldwide and is consistently the focus of researchers and experts in the health field. In recent years, the maintenance and promotion of health have emerged as paramount objectives within healthcare systems [1]. This emphasis is based on the recognition that enhancing health is instrumental in fostering the quality of health and medical services. Consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has acknowledged the significance of patient safety and has designated World Patient Safety Day to raise awareness and promote initiatives aimed at enhancing patient safety [2].

The WHO has identified the necessity of a comprehensive approach to patient safety that encompasses implementing changes in safety culture, system development, and professional development [3]. In recent years, the WHO has formulated standards for promoting a patient safety culture to address patient safety issues and provide safer services, with the expectation of reducing patient safety errors [3]. The WHO shares these safety-friendly hospital standards annually with patient safety experts around the world [4].

The results showed that the number of hospitalizations in low- and middle-income countries reached 134 million, leading to 2.6 million deaths [1, 4]. In high-income countries, nearly one in ten patients experiences harm during hospital care [5].

Research has demonstrated that 4 to 17% of patients encounter complications attributable to substandard safety practices, with more than half of these incidents being preventable [6]. In a study by Ilmidin & Ningsih, patient safety culture is reported to have an average score of 53.18% across seven countries (China, Ethiopia, USA, Philippines, Iran, Indonesia, and Ghana) and states [7]. In Iran, there is an absence of documented statistics concerning medical and nursing errors related to patient safety. However, the increasing number of complaints referred to the Medical System Organization suggests that the rate of these errors is likely high [4]. The confirmation of these errors would not only lead to mortality and disability but would also generate substantial financial burdens for the health system [8]. The WHO acknowledges the significance of patient safety and has identified it as a pressing public health issue. The World Health Assembly resolution delineates the organization’s manifold responsibilities, which encompass providing technical assistance to member states for the development of reporting and risk reduction systems, formulating evidence-based policies, promoting a safety culture, and encouraging research into patient safety [9]. This program is so important that it is considered one of the key interventions of the WHO in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Its main objective is to promote patient safety as an important principle for maintaining the quality of health services, taking into account the empowerment of hospitals and staff in providing safe services, with the active participation of patients and the community in promoting health safety [10]. The PSFHI creates a set of patient safety standards and tools to evaluate hospital patient safety programs and instill a culture of safety [11].

The patient safety-friendly hospital standards consist of a total of 140 items divided into the following five groups: Governance and Leadership Group with 36 standards, Patient and Community Involvement and Engagement Group with 28 standards, Safe and Evidence-Based Clinical Services Group with 44 standards, Safe Environment Group with 21 standards, and finally, Education Group with 11 standards. Therefore, each of the five groups is further divided into subgroups, which contain a total of 24 subgroups. Each subgroup includes three sets of standards, including mandatory, basic, and advanced. Mandatory standards are those that must be fully met for hospitals to be recognized as patient safety friendly [12]. The core Standards represent a set of requirements essential for implementing a hospital-wide patient safety program. They provide an operational framework that enables hospitals to evaluate patient care from a patient safety perspective, build staff capacity in this area, and engage patients in improving patient safety [13].

The advanced safety friendly hospital Standard is implemented after the attainment of the preceding two levels and encompasses criteria that not only facilitate the enhancement of service quality and the augmentation of patient safety but also fortify and preserve the delivery of safe services [14].

Contemporary literature on the effectiveness of implementing safety-friendly hospital standards on patient safety culture has yielded conflicting results. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is that hospitals possess unique circumstances and cultures, which must be taken into consideration during the design of processes aimed at achieving patient safety goals [1, 7, 14].

In the study by Camacho-Rodríguez et al., the safety status of patients varies significantly, and more efforts should be made to examine this status more precisely [15]. In a subsequent study by Ahmed et al., on the safety status of patients in hospitals, the safety status in the units studied is not satisfactory [16].

The implementation of a patient safety assessment has been demonstrated to benefit hospitals and society. This assessment serves as a crucial instrument for hospitals to demonstrate their commitment and accountability to patient safety. It functions as a key tool for modeling, identifying weaknesses, and encouraging improvement toward achieving standard goals. Ultimately, it serves to motivate staff to participate in improving patient safety. The assessment’s ultimate objective is to enhance the level of patient safety within the hospital and to create conditions that lead to safer services. This, in turn, helps protect the community from avoidable harm and reduces adverse events in the hospital environment. In light of these considerations, the present study aimed to examine the impact of implementing patient safety-oriented hospital standards on patient safety culture at Ebne Sina Hospital in 2024.

Instruments and Methods

Study design

This interventional study utilized a pre-post intervention design (single-group design) to evaluate the effect of the PSFHI on patient safety culture among nurses. The study was longitudinal, consisting of three assessment points, including baseline assessment (T0; administered before the education intervention (pre-test), post-education assessment 1 (T1; conducted immediately after the completion of the education intervention (post-test one), and post-education assessment 2 (T2; administered three months after the education intervention (post-test two).

Setting and sample size

The study was conducted at Ebne Sina Hospital and its population comprised all nurses currently employed at the hospital selected using census method. After obtaining the code of ethics from Tarbiat Modares University, informed consent was obtained by explaining the research objectives. A total of 420 nurses participated in the study; however, five participants were excluded from the final analysis because they changed their work environment during the study period, resulting in a final sample size of 415 nurses.

The inclusion criteria were nurses with at least six months of work experience in the hospital or its clinics, and nurses with direct responsibility for patient care. The exclusion criteria included nurses who did not participate in at least two educational sessions and nurses who did not complete the questionnaires.

The intervention consisted of a comprehensive education program on the PSFHI, conducted over six months, from September 22, 2024, to March 20, 2025. The education program covered key components of patient safety, including communication, error reporting, and teamwork. Educational materials were presented through oral presentations, workshops, and interactive sessions in the hospital’s education room.

The primary outcome was the change in patient safety culture scores between T0 and T1, as well as between T0 and T2. Patient safety culture was assessed using a standardized questionnaire developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture), which was administered at each assessment point. This scale comprises 12 dimensions with a total of 42 items, measured by the researcher using a Likert scale ranging from one to five points, indicating levels of agreement to disagreement. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been found to be acceptable in the study by Palmieri et al. [17].

Statistical analysis

The reliability was measured on 25 nurses, with a correlation coefficient of r=0.9. The distribution of samples was normal. Demographic information, such as age and years of experience, was collected during the pre-education assessment. Data were collected at three time points; before the education intervention (T0), immediately after the final education session (T1), and three months after the first post-test (T2). Of the 415 participants who completed the education program, all filled out the patient safety culture scale at T1 and T2. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics and patient safety culture scores. Paired t-tests were employed to compare the scores between T0 and T1. Additionally, Bonferroni tests were conducted to compare the scores between T0 and T1, as well as between T0 and T2. The methods and results are presented in accordance with CONSORT guidelines to ensure clarity and transparency. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20, employing descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, independent t-test, and one-way ANOVA.

Findings

No significant relationship was observed between demographic parameters and patient safety culture. The analyses indicated that there was no significant relationship between any of the demographic parameters including age, gender, martial status, workplace, educational level and work experience with patient safety culture. The statistical tests employed (Pearson correlation, independent t-test and one-way ANOVA) also revealed no significant differences among the groups. (Table 1).

Table 1. Relationship between demographic parameters and patient safety culture

The nurses’ responses to the patient safety culture questionnaire were positive with a statistically significant difference observed, indicating that the PSFHI training was effective in improving patient safety culture.

A total of 12 dimensions (D1-D12), reflecting various aspects of safety culture, were assessed. These dimensions represented nurses’ perceptions of safety culture changes throughout the intervention period.

Statistical analysis revealed significant improvements in patient safety culture scores over time (p-values<0.001). Notably, for Dimension 1 (D1), the mean score demonstrated considerable enhancement, with pairwise comparisons showing significant differences between T1 and T2 (mean difference=-0.663; p<0.001) and sustained improvements between T1 and T3. This trend was consistent across other key dimensions, such as D2, D4, and D5, which also exhibited marked improvements in safety culture scores between T1 and T2.

The effect of the initiative on patient safety culture was evident. The repeated measures ANOVA results showed statistically significant differences in safety culture scores across the three time points (p-value<0.001). This suggests strong evidence to conclude that the implementation of the PSFHI significantly improved the patient safety culture among nurses when comparing the scores from T1 to T2 and T3. The post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated which specific time comparisons were significant. For instance, for D1, the means demonstrated notable improvements from T1 to T2 and from T1 to T3, with the differences being significant (p<0.001). This suggests measurable improvements in safety practices due to education and the initiative as time progresses (Table 2).

Table 2. Effect of the initiative on mean patient safety culture score at three time points (before and two after))

In the dimensions of D1, D2, D4, and D5, each of these dimensions showed significant differences between T1 and T2, indicating improvements in safety culture scores. For instance, for D1, the mean difference between T1 and T2 was -0.663 (p<0.001), suggesting significant improvement. The results demonstrated statistically significant improvements across the three time points (T1, T2, and T3) (p<0.001), indicating strong evidence of the initiative’s effectiveness (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean differences in 12 dimensions

Discussion

This interventional study evaluated the impact of implementing the PSFHI on patient safety culture among nurses at Ebne Sina Hospital. We aimed to determine whether the PSFHI could significantly improve safety culture dimensions, as assessed by nurses, following the intervention.

Significant improvements were observed in teamwork within units (D1), suggesting enhanced collaboration and mutual support among nurses after education. This finding is consistent with Tveter Deilkås, reporting similar enhancements in teamwork following a patient safety initiative [18]. Although there was a statistically significant improvement in teamwork within units, some studies, such as Alharbi et al., have reported minimal changes in this dimension. This discrepancy may be due to differences in intervention intensity or baseline teamwork levels [19].

Supervisors’ role in promoting patient safety (D2) showed marked improvement. The structured education sessions empowered supervisors to better communicate and enforce safety standards, aligning with findings by Siddiqi et al., emphasizing the critical role of leadership in patient safety culture [20]. In the study by Namnabati et al., supervisory actions do not always translate into perceived safety improvements, suggesting variability in supervisory effectiveness and methods of supervision [21].

The education of patient safety initiatives fostered a culture of continuous learning and improvement (D3). Nurses became more proactive in identifying and addressing safety issues, consistent with the results of Namnabati et al., highlighting the importance of ongoing education in enhancing safety culture. However, González-Formoso et al. reported that continuous improvement in patient safety education does not always lead to perceived changes in safety culture, highlighting possible differences in organizational commitment and management [22].

Regarding the next dimension of the questionnaire, management support (D4) saw a notable boost, underscoring the importance of leadership commitment in fostering a safety culture. Opal Malone et al. have found similar results, indicating that visible support from management can significantly impact perceptions of safety culture [23]. It seems that managerial support leads to improved open communication, with nurses feeling more comfortable discussing safety concerns. This aligns with the findings of Christmals & Gross, noting that open communication is vital for an effective safety culture [24].

The frequency of event reporting (D6) increased after the education on patient safety, suggesting that nurses became more diligent in reporting errors and near misses [25]. However, unlike our findings, Wijenayake et al. have observed less pronounced changes in reporting frequency [26], highlighting the variability in intervention outcomes across different settings.

Another important dimension that increased after education was the holistic perception of nurses (D7), reflecting a more positive outlook on safety practices. This is consistent with Ali et al., reporting enhanced perceptions of safety following targeted interventions [27]. When nurses’ overall understanding of the concept of safety culture increases, inter-team collaboration also improves.

Our results showed moderate improvement in teamwork across units (D8), indicating better collaboration beyond individual units. Damayanti & Bachtiar found that interdisciplinary teamwork is crucial for a cohesive safety culture, supporting our findings [28].

Nurses’ feedback on errors (D9) improved after receiving periodic training, and one of the reasons for this may be the elimination of punishment when errors occur. Improvements in feedback and communication about errors suggest a more supportive environment for discussing and learning from mistakes. This aligns with Brodersen, emphasizing the role of constructive feedback in safety culture [29].

When non-punitive responses (D10) are given to nurses, they feel less fear of reprimand. However, Christmals & Gross have observed less pronounced improvements in this dimension [24], indicating potential variability in intervention effectiveness. Additionally, González-Formoso et al. have noted minimal changes [22], suggesting that creating a non-punitive culture may require more time and effort.

Staffing issues (D11) were perceived more positively after the intervention, and nurses felt better supported. Sheridan et al. found that adequate staffing is a key factor in maintaining a safe environment for patients [30], which is consistent with our findings. However, Opal Malone et al. have reported no significant change in their study results [23]. This discrepancy could be because, in Opal Malone et al.’s study, the hospital is facing a nursing shortage, while in our study, there was no shortage of nurses, and nurses were not forced to work extra shifts.

Regarding the last dimension of the patient safety culture questionnaire, patients’ handoffs and transitions (D12) saw notable improvements, enhancing the continuity of patient safety. This dimension aligns with Ahmed et al., highlighting the importance of effective transfer in ensuring patient safety [16].

The implementation of the PSFHI led to statistically significant improvements across multiple dimensions of patient safety culture, including teamwork, supervisory roles, communication, event reporting, and staff perceptions. These findings underscore the importance of structured interventions, continuous education, and leadership support in fostering a culture of safety within hospitals.

The PSFHI offers a valuable framework for other healthcare institutions aiming to enhance patient safety culture. However, the variability in outcomes reported across studies highlights the importance of tailoring interventions to specific organizational contexts and baseline conditions. Future research should focus on the long-term sustainability of these improvements, exploring which components of the PSFHI are most impactful. Additionally, comparative studies across diverse healthcare settings can provide further insights into the generalizability and adaptability of this model. Due to the absence of a control group, we cannot directly compare the intervention group with a non-intervention group.

We firmly advocate for implementing educational strategies that are based on solid evidence to enhance both patient care and the learning outcomes for nurses. Our research shows that specific teaching techniques and practical approaches in clinical settings significantly improve performance. This insight can help shape educational programs and enhance nursing competencies. Adopting this approach not only validates the effectiveness of our training methods but also encourages ongoing research to refine optimal practices in nursing. Ultimately, this will lead to improved patient care outcomes and support the professional development of nurses, contributing to a higher standard of patient safety.

Conclusion

The implementation of safety standards has benefits for hospitals and society by enhancing patient safety and reducing adverse events.

Acknowledgments: This research is part of the joint cooperation project between Tarbiat Modares University of Tehran and the industry (Ebne Sina Hospital, Tehran). The researchers of this study would like to thank all the participants.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University authorized the research protocol (Register number: IR.MODARES.REC.1402.076).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests regarding the present paper.

Authors' Contribution: Ahmadi Hedayat M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (25%); Khoobi M (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (50%); Anisiyan A (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Tarbiat Modares University and Ebne Sina Hospital.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2025/01/20 | Accepted: 2025/03/12 | Published: 2025/03/17

Received: 2025/01/20 | Accepted: 2025/03/12 | Published: 2025/03/17

References

1. Lungu D, Harvey J. A systematic review of the literature with evidence based measures to improve patient safety in healthcare settings. Texila Int J Acad Res. 2023 Apr:1-9. [Link]

2. Mitchell P, Cribb A, Entwistle V. Patient safety and the question of dignitary harms. J Med Philos. 2023;48(1):33-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jmp/jhac035]

3. Ljungberg Persson C, Nordén Hägg A, Södergård B. Measuring the patient safety climate in community pharmacies: An updated national survey. BMJ Open. 2025;15(1):e088323. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2024-088323]

4. Sheikhy Chaman MR. Patient safety culture from the perspective of nurses working in selected hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Iran J Nurs. 2020;33(124):92-103. [Persian] [Link]

5. Olsen E, Leonardsen AL. Use of the hospital survey of patient safety culture in Norwegian hospitals: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6518. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18126518]

6. Granel-Giménez N, Palmieri PA, Watson-Badia CE, Gómez-Ibáñez R, Leyva-Moral JM, Bernabeu-Tamayo MD. Patient safety culture in European hospitals: A comparative mixed methods study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):939. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19020939]

7. Ilmidin I, Ningsih N. Analysis of patient safety culture using hospital survey on patient safety culture (HSOPSC) in seven countries. JURNAL BERKALA KESEHATAN. 2022;8(2):132. [Link] [DOI:10.20527/jbk.v8i2.14647]

8. Lee SE, Scott LD, Dahinten VS, Vincent C, Lopez KD, Park CG. Safety culture, patient safety, and quality of care outcomes: A literature review. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41(2):279-304. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0193945917747416]

9. Dhingra-Kumar N, Brusaferro S, Arnoldo L. Patient safety in the world. In: Donaldson L, Ricciardi W, Sheridan S, Tartaglia R, editors. Textbook of patient safety and clinical risk management. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 93-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-59403-9_8]

10. Cameron ID, Dyer SM, Panagoda CE, Murray GR, Hill KD, Cumming RG, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9(9):CD005465. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub4]

11. Alabdaly A, Hinchcliff R, Debono D, Hor SY. Relationship between patient safety culture and patient experience in hospital settings: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):906. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-024-11329-w]

12. Prabhu N, McGuire C, Hong P, Bezuhly M. Patient safety initiatives in cosmetic breast surgery: A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022;75(11):4180-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bjps.2022.06.099]

13. Rainbow JG, Drake DA, Steege LM. Nurse health, work environment, presenteeism and patient safety. West J Nurs Res. 2020;42(5):332-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0193945919863409]

14. Arnal-Velasco D, Paz-Martín D. Extension of patient safety initiatives to perioperative care. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2022;35(6):717-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001195]

15. Camacho-Rodríguez DE, Carrasquilla-Baza DA, Dominguez-Cancino KA, Palmieri PA. Patient safety culture in Latin American hospitals: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14380. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph192114380]

16. Ahmed FA, Asif F, Munir T, Halim MS, Feroze Ali Z, Belgaumi A, et al. Measuring the patient safety culture at a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan using the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC). BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(1):e002029. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-002029]

17. Palmieri PA, Leyva-Moral JM, Camacho-Rodriguez DE, Granel-Gimenez N, Ford EW, Mathieson KM, et al. Hospital survey on patient safety culture (HSOPSC): A multi-method approach for target-language instrument translation, adaptation, and validation to improve the equivalence of meaning for cross-cultural research. BMC Nurs. 2020;19:23. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12912-020-00419-9]

18. Tveter Deilkås EC. Patient safety culture-opportunities for healthcare management: The safety attitudes questionnaire-short form 2006, Norwegian version-1) Psychometric properties, 2) Variation by organizational level and 3) by position [dissertation]. Norway: Akershus University Hospital; 2011. [Link]

19. Alharbi W, Cleland J, Morrison Z. Assessment of patient safety culture in an adult oncology department in Saudi Arabia. Oman Med J. 2018;33(3):200-8. [Link] [DOI:10.5001/omj.2018.38]

20. Siddiqi S, Elasady R, Khorshid I, Fortune T, Leotsakos A, Letaief M, et al. Patient safety friendly hospital initiative: From evidence to action in seven developing country hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(2):144-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/intqhc/mzr090]

21. Namnabati M, Farzi S, Ajoodaniyan N. Care challenges of the neonatal intensive care unit. Iran J Nurs Res. 2016;11(4):35-41. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/ijnr-110404]

22. González-Formoso C, Martín-Miguel MV, Fernández-Domínguez MJ, Rial A, Lago-Deibe FI, Ramil-Hermida L, et al. Adverse events analysis as an educational tool to improve patient safety culture in primary care: A randomized trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:50. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2296-12-50]

23. Opal Malone D, Helen S, Denice C. A comparative descriptive analysis of the strategies used by health-care professionals at a rural hospital in Jamaica to promote patient safety. J Patient Saf Qual Improv. 2016;4(4):427-33. [Link]

24. Christmals CD, Gross JJ. An integrative literature review framework for postgraduate nursing research reviews. Eur J Res Med Sci. 2017;5(1). [Link]

25. Khoobi M, Ahmadi F. Maintaining moral sensitivity as an inevitable necessity in the nursing profession. J Caring Sci. 2023;12(4):1-2. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/jcs.2023.33147]

26. Wijenayake PH, Manathunga MSN, Samarasinghe YJ, Wickramarathne IWMJ, Abeynayake AJ, Vijayakumara RGK. Assess the level of implementation of patient safety culture in a tertiary care hospital in Sri Lanka. Sci Res J. 2020;8(4):15-28. [Link] [DOI:10.31364/SCIRJ/v8.i4.2020.P0420759]

27. Ali H, Ibrahem SZ, Al Mudaf B, Al Fadalah T, Jamal D, El-Jardali F. Baseline assessment of patient safety culture in public hospitals in Kuwait. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):158. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-018-2960-x]

28. Damayanti RA, Bachtiar A. Outcome of patient safety culture using the hospital survey on patient safety culture (HSOPSC) in Asia: A systematic review with meta analysis. Proc Int Conf Appl Sci Health. 2019;(4):849-63. [Link]

29. Brodersen LD. Integrative reviews part 2: Critiquing integrative reviews of nursing education literature. Proceedings of the Nursing Education Research Conference. Washington, DC: Sigma Theta Tau International, National League for Nursing; 2020. [Link]

30. Sheridan S, Sherman H, Kooijman A, Vazquez E, Kirk K, Metwally N, et al. Patients for patient safety. In: Donaldson L, Ricciardi W, Sheridan S, Tartaglia R, editors. Textbook of patient safety and clinical risk management. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 67-79. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-59403-9_6]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |