Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 139-145 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Veriza E, Abbasiah A, Nopindra A, Widdefrita W. Impact of Educational Interventions on Students’ Cognitive, Affective, and Psychomotor Abilities in Detecting Breast Cancer Risk in Jambi. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :139-145

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79039-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-79039-en.html

1- Department of Health Promotion, Health Polytechnic of Jambi, Jambi, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 593 kb]

(407 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (560 Views)

Full-Text: (54 Views)

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide and the leading cause of cancer-related death among women [1, 2]. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer accounts for approximately 25% of all cancer cases globally, with prevalence rates steadily increasing each year [3]. In developed countries, the prevalence of breast cancer is notably high, particularly in European countries, North America, and Oceania. For example, in the United States, about 1 in 8 women are at risk of developing breast cancer during their lifetime, with more than 270,000 new cases diagnosed each year [4]. European countries, such as France and Germany also report high prevalence rates, with over 50,000 new cases documented annually [5].

However, despite the high prevalence of breast cancer in developed countries, survival rates are significantly higher. This is attributed to more advanced healthcare systems, greater access to early detection, and higher levels of public awareness. Early detection techniques, such as mammography and breast self-examination (BSE), have been widely implemented in many developed countries, contributing to a decrease in mortality rates from breast cancer [6, 7].

On the other hand, in developing countries, the prevalence of breast cancer is also rising, but detection rates and survival outcomes are much lower compared to developed countries [8, 9]. In Indonesia, for instance, breast cancer is the leading cause of death among women, with 2020 GLOBOCAN data showing approximately 65,000 new cases each year [10]. Despite the increasing prevalence of breast cancer in Indonesia, many women still lack access to early screening and adequate treatment. One of the main reasons for this is the limited availability of healthcare facilities and the low level of public awareness about the importance of early detection.

A major challenge faced by developing countries, including Indonesia, is the unequal access to medical facilities and the low public awareness regarding the significance of early breast cancer detection [11]. Many women in Indonesia seek medical care only after the cancer has reached an advanced stage, significantly reducing their chances of recovery. Therefore, increasing knowledge about early detection techniques, such as breast self-examination (SADARI), is crucial, especially among students and women of reproductive age [12, 13].

Breast cancer, despite being a global health issue, shows varying prevalence rates between developed and developing countries. For developing countries, including Indonesia, raising awareness about breast cancer and early detection is an important step in reducing mortality rates and improving the quality of life for women. Therefore, educational programs targeting early detection through BSE and enhancing teacher involvement in health education can serve as effective solutions to increase survival rates and prevent further cases of breast cancer [14].

High school students are at a critical developmental stage for establishing lifelong healthy behaviors [15]. During this period, they are exposed to various sources of information, including education received at school. Despite the critical role of early breast cancer detection and practical techniques like SADARI, these topics have not been adequately incorporated into the current health education curriculum [16]. Teachers, as key educational agents, play a pivotal role in addressing this gap. Beyond disseminating knowledge, teachers serve as role models and motivators, fostering positive attitudes and practical skills among students [17].

Teachers occupy a strategic position in promoting the early detection of breast cancer due to their close relationships with students and their influence during the learning process. By delivering accurate educational content on breast cancer and SADARI, teachers can inspire and guide students to incorporate self-examination practices into their routines. However, many teachers lack sufficient knowledge about early detection, underscoring the need for targeted training and resources. In this context, teachers function not only as knowledge providers but also as facilitators who support students in developing the necessary skills for early breast cancer detection [18].

Individual factors, including students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills, play a crucial role in their ability to detect breast cancer risks effectively. Students who possess comprehensive knowledge of the signs and symptoms of breast cancer are more likely to understand the importance of self-examination [19, 20]. Furthermore, a positive attitude toward health and prevention can motivate students to adopt routine examination practices. Practical skills in performing SADARI, developed through hands-on training and health education, significantly increase the likelihood of early detection [21, 22].

Despite receiving information about SADARI, many students lack the practical skills needed to perform it correctly, often due to insufficient hands-on training or interactive learning opportunities. Including hands-on practices, such as SADARI in school programs is crucial to help students move beyond theoretical understanding and acquire the practical skills necessary to actively monitor their breast health [23, 24].

The purpose of this study was to investigate how personal factors and teacher involvement impact the ability of high school students in Jambi City to identify the signs and symptoms of breast cancer. By identifying the factors that affect students’ abilities in early detection, this study aimed to inform the development of more effective strategies for improving students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills in practicing BSE. Ultimately, the findings are expected to contribute to the design of health education programs that enhance students’ awareness and engagement in early breast cancer detection initiatives.

Materials and Methods

Design

This observational analytic research utilized a quasi-experimental method with a two-group pre-test-post-test design, which is an experimental method that compared the results of treatment in two different groups.

Participants

The study was done from April to June 2024 at SMA N 3 and SMA N 8 in Jambi City, with a total of 70 participants chosen based on specific inclusion criteria. These criteria included being between the ages of 15 and 18, currently enrolled in the school, willing to participate, and having no medical conditions that could interfere with the results. The focus was on female students with no personal history of breast cancer or any breast cancer in their immediate family. These students lacked adequate knowledge of self-efficacy related to BSE skills. Exclusion criteria were applied to those who could not attend all sessions or declined participation.

The sample size, calculated using Slovin’s formula for a large population with a 10% margin of error, resulted in 70 participants. This sample was divided into two equal groups of 35; one group receiving the intervention and the other serving as a control group. Randomization was used to ensure that the groups were balanced, with the intervention group participating in an educational program while the control group did not receive any intervention.

Data collection

Knowledge, attitude, school support, and students’ skills in performing SADARI, were treated as dependent parameters. Knowledge was defined as the student’s understanding of the research topic and assessed using a standardized multiple-choice questionnaire. Attitude was considered students’ feelings, views, or inclinations toward the topic, measured with a five-point Likert scale-based questionnaire. School support encompassed the school’s role and contributions in facilitating the program, evaluated using a closed-ended questionnaire. Students’ skills in performing SADARI were defined as their technical ability to carry out the examination independently and correctly, measured through direct observation using a checklist-based assessment sheet.

Data collection was carried out by two enumerators who were trained to understand the research instruments and methods. The process was conducted in two pre-intervention and post-intervention phases to measure changes in the parameters. In the first phase, the enumerators distributed questionnaires to assess the initial levels of knowledge, attitude, and school support and observed the students’ skills in performing SADARI. The second phase occurred after the intervention program was completed to evaluate the impact of the intervention on all parameters.

The validity and reliability assessments indicated that the research tools were highly effective in accurately measuring the parameters. The validity test was conducted using the item-total correlation method, where each questionnaire item was analyzed against the total score. Invalid items were removed or replaced. The results showed that all items had a correlation value greater than 0.30, confirming their validity in measuring the intended aspects. The internal consistency of the instrument was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, with values for each parameter above 0.70, demonstrating strong reliability. Therefore, the tools utilized were considered both valid and dependable for gathering data.

The SADARI education, delivered by lecturers from the Jambi Ministry of Health Polytechnic, targeted high school students and teachers with a session lasting 45 minutes. During the session, the lecturer provided detailed explanations about the importance of BSE for detecting changes that could signal breast cancer. The material covered proper examination techniques, signs of changes to watch for, and steps for maintaining breast health. This education aimed to enhance awareness and knowledge among both students and teachers regarding the significance of early detection, enabling them to be more attuned to bodily changes and share this information with others.

After the educational session, a 15-minute question-and-answer period was held, allowing participants, both students and teachers, to ask questions and explore the material further. Before the educational session, participants took a pre-test to evaluate their existing knowledge of BSE. This assessment was essential for determining their initial level of understanding and pinpointing areas where they might have gaps in knowledge. Following the education and question-and-answer session, a post-test was administered to evaluate the participants’ understanding after receiving the material. This post-test was crucial for measuring the effectiveness of the education and ensuring that the content was comprehended by both students and teachers. In this study, the post-test for students was conducted 15 minutes after the session, while the school role variable was assessed one week after the education. This timing allowed teachers to apply the material in their interactions with students.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out in two univariate and inferential phases. In the univariate phase, pre-test and post-test data were reviewed to assess frequency distributions and track changes in the four parameters. Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency (mean, median, and mode) and dispersion (standard deviation and variance), were calculated to identify score variations.

Prior to conducting further analysis, a normality test was performed, confirming that the data followed a normal distribution (p>0.05). In the inferential phase, a t-test was used to determine significant differences between pre-test and post-test scores, as well as between students and teachers. A paired t-test was employed to compare the mean scores within the same group to assess significant changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, and school roles. The independent t-test was applied to compare post-test score differences between students and teachers. A p-value of <0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference.

Findings

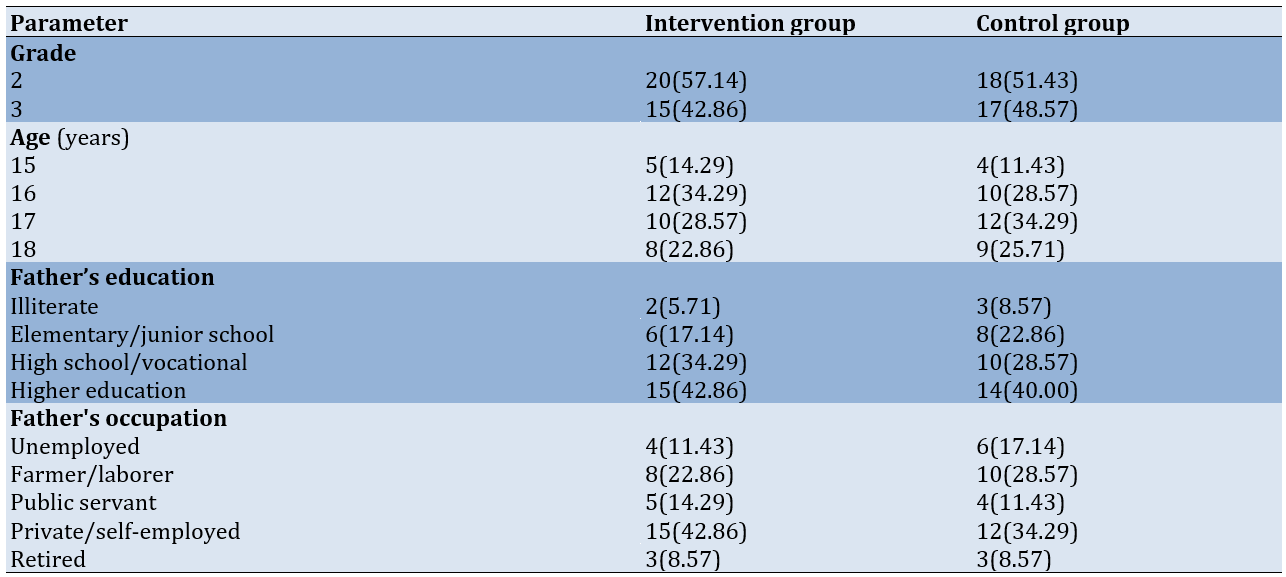

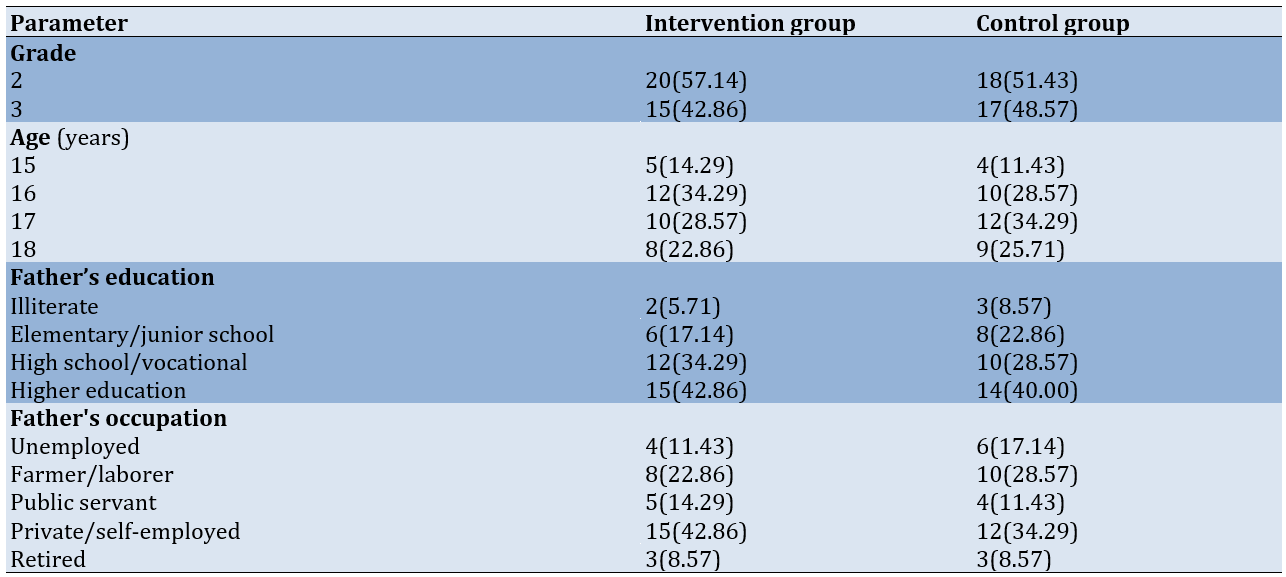

The majority of students were in grade 2, making up 57.14% of the intervention group and 51.43% of the control group, while grade 3 students represented 42.86% and 48.57%, respectively. In terms of age, most students were 16 or 17 years old, with 34.29% and 28.57% in the intervention group, and 28.57% and 34.29% in the control group.

Regarding the education level of fathers, the majority had completed high school or college, with 34.29% and 42.86% in the intervention group, and 28.57% and 40.00% in the control group, respectively. Fathers with lower educational attainment made up a smaller portion. Concerning occupation, most fathers were self-employed or worked as farmers/laborers. A smaller proportion of fathers were unemployed or retired. This data reflects an evenly distributed demographic across both groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of students’ and parents’ characteristics (fathers)

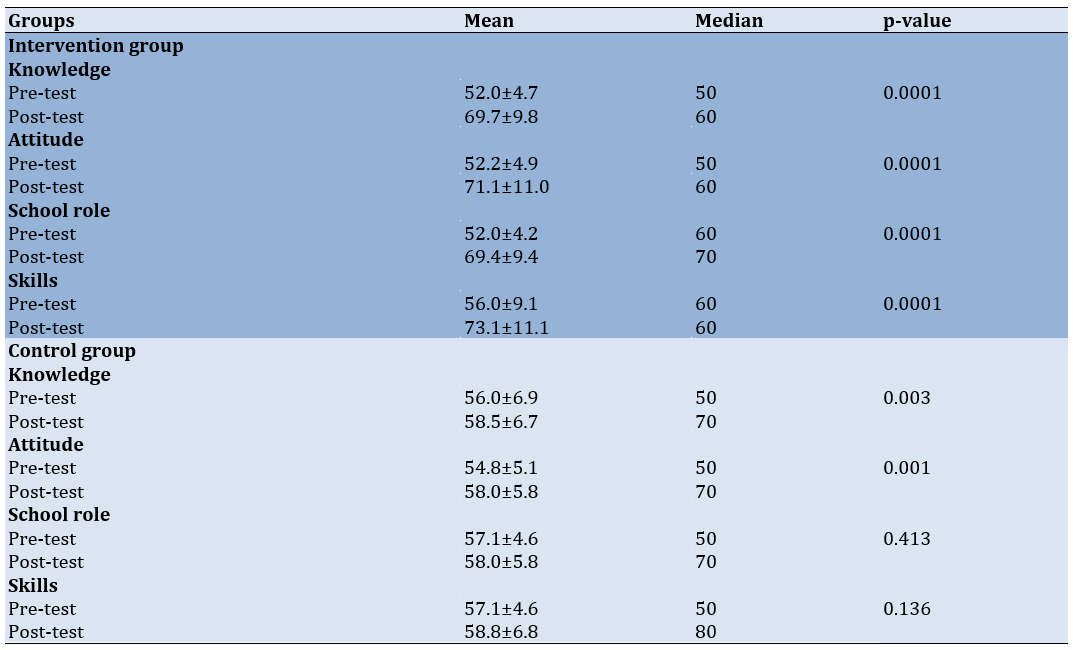

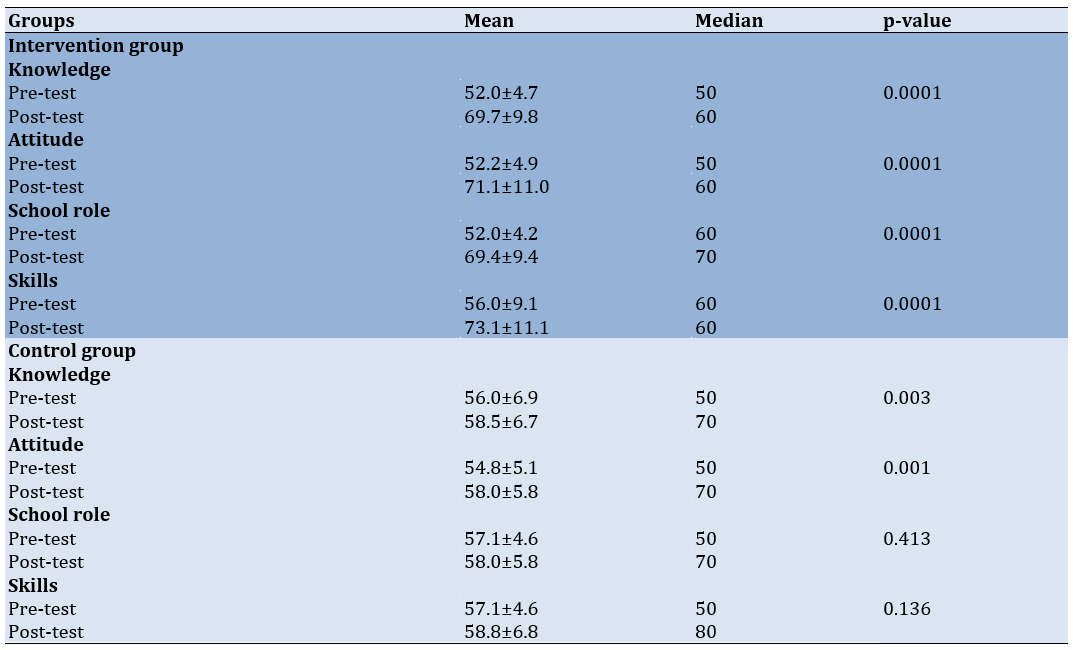

In the intervention group, there was a notable increase in the mean scores for knowledge, rising from 52.0±4.7 to 69.7±9.8; for attitude, from 52.2±4.9 to 71.1±11.0; for school role, from 52±4.2 to 69.4±9.4; and for skills, from 56 ± 9.1 to 73.1±11.1. Meanwhile, the control group also experienced significant improvements in knowledge (p=0.003) and attitude (p=0.001), but the changes in school role (p=0.413) and skills (p=0.136) were not statistically significant. These findings indicate that the intervention group showed greater progress in knowledge, attitude, school role, and skills than the control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of research parameters in the intervention and control groups

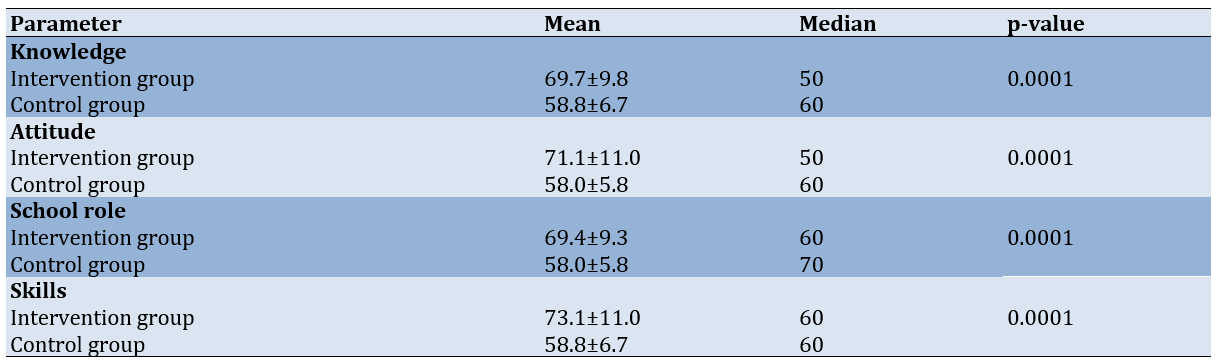

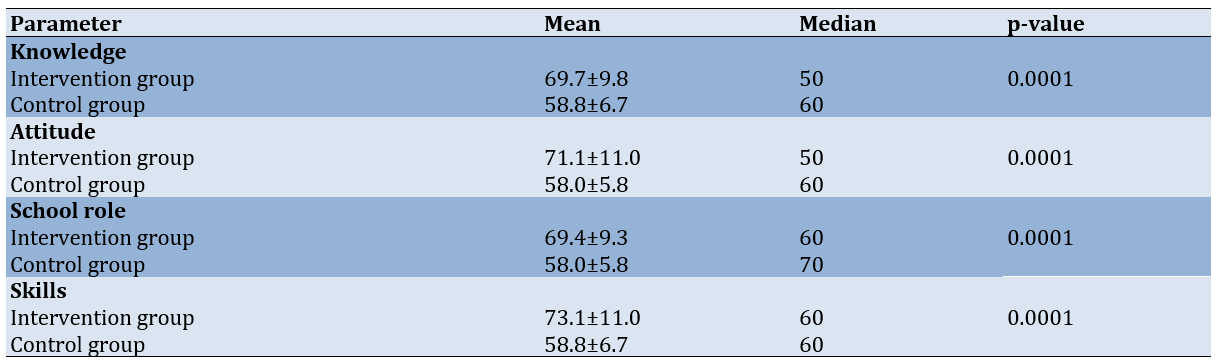

The intervention group achieved significantly higher mean post-test scores than the control group across all assessed parameters (p<0.0001). For knowledge, the intervention group had a mean score of 69.7±9.8, while the control group scored 58.8±6.7. Regarding attitude, the intervention group’s mean score was 71.1±11.0, surpassing the control group’s score of 58.0±5.8. In the school role category, the intervention group scored an average of 69.4±9.3, while the control group’s average was 58.0±5.8. Lastly, for skills, the intervention group again outperformed the control group with a mean score of 73.1±11.0 compared to 58.8±6.7. These findings highlight the significant effectiveness of the intervention in enhancing students’ knowledge, attitudes, school roles, and skills (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean post-test scores of research parameters in the intervention and control groups

Discussion

This study aimed to explore how personal factors, attitudes, competencies, and school involvement influence students’ capacity to recognize the risks associated with breast cancer symptoms through participation in the SADARI program. The SADARI education had a significant impact on improving students’ knowledge, attitudes, school roles, and skills in identifying breast cancer risk signs and symptoms. In the intervention group, post-test scores across all parameters were notably higher than those in the control group. These results are consistent with prior studies that emphasize the success of health education programs in raising awareness and understanding of the importance of early breast cancer detection [25].

The significant increase in knowledge within the intervention group reflects the effective delivery of educational content designed to improve student understanding. The mean post-test knowledge score for the intervention group was considerably higher than that of the control group, suggesting that the program’s interactive and engaging approach enhanced students’ grasp of BSE as a preventive measure. This increase in knowledge is likely to foster positive behavioral changes by boosting the confidence of the participants [26], and heightened confidence contributes to improving students’ ability to perform BSE [27]. These results align with studies by Absavaran et al. [28], Pirzadeh et al. [29], and Ghaffari et al. [30] in Iran, showing significant improvements in knowledge about SBE through video-based multimedia education.

Along with the increase in knowledge, students’ attitudes toward the SADARI screening process also showed significant improvement. A more positive attitude suggests that students are more inclined to apply the knowledge they gained in their everyday routines. The mean attitude score for the intervention group was higher compared to the control group. This shift can be attributed to the educational strategy, which highlighted both the personal health advantages of SADARI and its importance as a societal responsibility. This improvement reflects another positive outcome of the intervention, which not only boosted participants’ knowledge but also influenced their attitudes. These findings align with those of Mohammad et al. [31], demonstrating the success of similar programs in enhancing female students’ attitudes toward breast cancer and BSE.

There was also a notable difference in school support between the intervention and control groups. The intervention group had a higher mean post-test score compared to the control group. The active participation of schools in fostering a supportive environment for health education plays a critical role in the success and long-term viability of such programs. Factors, such as allocating time for education, involving teachers, and providing oversight by school leaders all contribute to the program’s effectiveness. Previous research has shown that individuals who receive strong social support tend to have higher self-esteem, and there is a significant correlation between these two factors [28]. Additionally, strong social support and high self-esteem can enhance self-efficacy, which in turn improves the likelihood of performing BSE effectively [22].

Skill demonstrated the most significant improvement in the intervention group. This result highlights that, beyond theoretical knowledge, hands-on training through simulations and demonstrations greatly improves students’ ability to accurately conduct the SADARI examination. This skill is essential, as improper techniques can reduce the effectiveness of early breast cancer detection [32, 33].

The notable differences between the intervention and control groups in all parameters highlight the success of the educational intervention, which had a greater impact compared to the typical learning experience in the control group. While the control group did show some improvement, it was not as significant as the progress seen in the intervention group, emphasizing the importance of a more focused and organized approach to achieving substantial results.

These results highlight the importance of incorporating SADARI education programs at the secondary school level as part of broader breast cancer prevention efforts. By engaging both students and teachers, the program not only improves individual knowledge and skills but also fosters a school environment that is more attuned to the importance of breast health. This method is anticipated to serve as a prototype for comparable programs in different areas.

This study has a few limitations. Firstly, the use of a cross-sectional design means that causal relationships cannot be determined. Secondly, the brief duration of the intervention prevents an assessment of its long-term effects. The study’s ability to be generalized is also restricted, as it was carried out in only two high schools in Jambi City. Furthermore, relying on self-reported data introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, and assessing SADARI skills in a controlled setting may not fully represent how these skills are practiced in real-world scenarios.

We demonstrated that the SADARI education program has a notable positive effect on enhancing students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and the role of schools in promoting early breast cancer risk detection. The intervention group, which participated in the education program, showed significantly greater improvements than the control group across all measured parameters, with inferential analysis revealing statistically significant differences. These findings underscore the effectiveness of education-based interventions as a strategic approach to enhancing awareness and skills related to early breast cancer detection among students and teachers.

Conclusion

The SADARI educational program successfully improves students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and the support they receive from their schools.

Acknowledgments: We extend our heartfelt gratitude to everyone who contributed to this research. In particular, we would like to acknowledge the Head of the Health Polytechnic of Jambi and the Health Polytechnic of Padang for their invaluable support and guidance throughout this project. We are also grateful to the application development team for their insightful input during the research process.

Ethical Permissions: This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health, Jambi, under protocol number LB.02.06/5/168/2024. All procedures adhered to established research ethics standards, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights and privacy

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of intersts.

Authors' Contribution: Veriza E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Abbasiah A (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Nopindra A (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Widdefrita W (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by a grant from the Indonesian Ministry of Health.

Breast cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide and the leading cause of cancer-related death among women [1, 2]. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer accounts for approximately 25% of all cancer cases globally, with prevalence rates steadily increasing each year [3]. In developed countries, the prevalence of breast cancer is notably high, particularly in European countries, North America, and Oceania. For example, in the United States, about 1 in 8 women are at risk of developing breast cancer during their lifetime, with more than 270,000 new cases diagnosed each year [4]. European countries, such as France and Germany also report high prevalence rates, with over 50,000 new cases documented annually [5].

However, despite the high prevalence of breast cancer in developed countries, survival rates are significantly higher. This is attributed to more advanced healthcare systems, greater access to early detection, and higher levels of public awareness. Early detection techniques, such as mammography and breast self-examination (BSE), have been widely implemented in many developed countries, contributing to a decrease in mortality rates from breast cancer [6, 7].

On the other hand, in developing countries, the prevalence of breast cancer is also rising, but detection rates and survival outcomes are much lower compared to developed countries [8, 9]. In Indonesia, for instance, breast cancer is the leading cause of death among women, with 2020 GLOBOCAN data showing approximately 65,000 new cases each year [10]. Despite the increasing prevalence of breast cancer in Indonesia, many women still lack access to early screening and adequate treatment. One of the main reasons for this is the limited availability of healthcare facilities and the low level of public awareness about the importance of early detection.

A major challenge faced by developing countries, including Indonesia, is the unequal access to medical facilities and the low public awareness regarding the significance of early breast cancer detection [11]. Many women in Indonesia seek medical care only after the cancer has reached an advanced stage, significantly reducing their chances of recovery. Therefore, increasing knowledge about early detection techniques, such as breast self-examination (SADARI), is crucial, especially among students and women of reproductive age [12, 13].

Breast cancer, despite being a global health issue, shows varying prevalence rates between developed and developing countries. For developing countries, including Indonesia, raising awareness about breast cancer and early detection is an important step in reducing mortality rates and improving the quality of life for women. Therefore, educational programs targeting early detection through BSE and enhancing teacher involvement in health education can serve as effective solutions to increase survival rates and prevent further cases of breast cancer [14].

High school students are at a critical developmental stage for establishing lifelong healthy behaviors [15]. During this period, they are exposed to various sources of information, including education received at school. Despite the critical role of early breast cancer detection and practical techniques like SADARI, these topics have not been adequately incorporated into the current health education curriculum [16]. Teachers, as key educational agents, play a pivotal role in addressing this gap. Beyond disseminating knowledge, teachers serve as role models and motivators, fostering positive attitudes and practical skills among students [17].

Teachers occupy a strategic position in promoting the early detection of breast cancer due to their close relationships with students and their influence during the learning process. By delivering accurate educational content on breast cancer and SADARI, teachers can inspire and guide students to incorporate self-examination practices into their routines. However, many teachers lack sufficient knowledge about early detection, underscoring the need for targeted training and resources. In this context, teachers function not only as knowledge providers but also as facilitators who support students in developing the necessary skills for early breast cancer detection [18].

Individual factors, including students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills, play a crucial role in their ability to detect breast cancer risks effectively. Students who possess comprehensive knowledge of the signs and symptoms of breast cancer are more likely to understand the importance of self-examination [19, 20]. Furthermore, a positive attitude toward health and prevention can motivate students to adopt routine examination practices. Practical skills in performing SADARI, developed through hands-on training and health education, significantly increase the likelihood of early detection [21, 22].

Despite receiving information about SADARI, many students lack the practical skills needed to perform it correctly, often due to insufficient hands-on training or interactive learning opportunities. Including hands-on practices, such as SADARI in school programs is crucial to help students move beyond theoretical understanding and acquire the practical skills necessary to actively monitor their breast health [23, 24].

The purpose of this study was to investigate how personal factors and teacher involvement impact the ability of high school students in Jambi City to identify the signs and symptoms of breast cancer. By identifying the factors that affect students’ abilities in early detection, this study aimed to inform the development of more effective strategies for improving students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills in practicing BSE. Ultimately, the findings are expected to contribute to the design of health education programs that enhance students’ awareness and engagement in early breast cancer detection initiatives.

Materials and Methods

Design

This observational analytic research utilized a quasi-experimental method with a two-group pre-test-post-test design, which is an experimental method that compared the results of treatment in two different groups.

Participants

The study was done from April to June 2024 at SMA N 3 and SMA N 8 in Jambi City, with a total of 70 participants chosen based on specific inclusion criteria. These criteria included being between the ages of 15 and 18, currently enrolled in the school, willing to participate, and having no medical conditions that could interfere with the results. The focus was on female students with no personal history of breast cancer or any breast cancer in their immediate family. These students lacked adequate knowledge of self-efficacy related to BSE skills. Exclusion criteria were applied to those who could not attend all sessions or declined participation.

The sample size, calculated using Slovin’s formula for a large population with a 10% margin of error, resulted in 70 participants. This sample was divided into two equal groups of 35; one group receiving the intervention and the other serving as a control group. Randomization was used to ensure that the groups were balanced, with the intervention group participating in an educational program while the control group did not receive any intervention.

Data collection

Knowledge, attitude, school support, and students’ skills in performing SADARI, were treated as dependent parameters. Knowledge was defined as the student’s understanding of the research topic and assessed using a standardized multiple-choice questionnaire. Attitude was considered students’ feelings, views, or inclinations toward the topic, measured with a five-point Likert scale-based questionnaire. School support encompassed the school’s role and contributions in facilitating the program, evaluated using a closed-ended questionnaire. Students’ skills in performing SADARI were defined as their technical ability to carry out the examination independently and correctly, measured through direct observation using a checklist-based assessment sheet.

Data collection was carried out by two enumerators who were trained to understand the research instruments and methods. The process was conducted in two pre-intervention and post-intervention phases to measure changes in the parameters. In the first phase, the enumerators distributed questionnaires to assess the initial levels of knowledge, attitude, and school support and observed the students’ skills in performing SADARI. The second phase occurred after the intervention program was completed to evaluate the impact of the intervention on all parameters.

The validity and reliability assessments indicated that the research tools were highly effective in accurately measuring the parameters. The validity test was conducted using the item-total correlation method, where each questionnaire item was analyzed against the total score. Invalid items were removed or replaced. The results showed that all items had a correlation value greater than 0.30, confirming their validity in measuring the intended aspects. The internal consistency of the instrument was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, with values for each parameter above 0.70, demonstrating strong reliability. Therefore, the tools utilized were considered both valid and dependable for gathering data.

The SADARI education, delivered by lecturers from the Jambi Ministry of Health Polytechnic, targeted high school students and teachers with a session lasting 45 minutes. During the session, the lecturer provided detailed explanations about the importance of BSE for detecting changes that could signal breast cancer. The material covered proper examination techniques, signs of changes to watch for, and steps for maintaining breast health. This education aimed to enhance awareness and knowledge among both students and teachers regarding the significance of early detection, enabling them to be more attuned to bodily changes and share this information with others.

After the educational session, a 15-minute question-and-answer period was held, allowing participants, both students and teachers, to ask questions and explore the material further. Before the educational session, participants took a pre-test to evaluate their existing knowledge of BSE. This assessment was essential for determining their initial level of understanding and pinpointing areas where they might have gaps in knowledge. Following the education and question-and-answer session, a post-test was administered to evaluate the participants’ understanding after receiving the material. This post-test was crucial for measuring the effectiveness of the education and ensuring that the content was comprehended by both students and teachers. In this study, the post-test for students was conducted 15 minutes after the session, while the school role variable was assessed one week after the education. This timing allowed teachers to apply the material in their interactions with students.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out in two univariate and inferential phases. In the univariate phase, pre-test and post-test data were reviewed to assess frequency distributions and track changes in the four parameters. Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency (mean, median, and mode) and dispersion (standard deviation and variance), were calculated to identify score variations.

Prior to conducting further analysis, a normality test was performed, confirming that the data followed a normal distribution (p>0.05). In the inferential phase, a t-test was used to determine significant differences between pre-test and post-test scores, as well as between students and teachers. A paired t-test was employed to compare the mean scores within the same group to assess significant changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, and school roles. The independent t-test was applied to compare post-test score differences between students and teachers. A p-value of <0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference.

Findings

The majority of students were in grade 2, making up 57.14% of the intervention group and 51.43% of the control group, while grade 3 students represented 42.86% and 48.57%, respectively. In terms of age, most students were 16 or 17 years old, with 34.29% and 28.57% in the intervention group, and 28.57% and 34.29% in the control group.

Regarding the education level of fathers, the majority had completed high school or college, with 34.29% and 42.86% in the intervention group, and 28.57% and 40.00% in the control group, respectively. Fathers with lower educational attainment made up a smaller portion. Concerning occupation, most fathers were self-employed or worked as farmers/laborers. A smaller proportion of fathers were unemployed or retired. This data reflects an evenly distributed demographic across both groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of students’ and parents’ characteristics (fathers)

In the intervention group, there was a notable increase in the mean scores for knowledge, rising from 52.0±4.7 to 69.7±9.8; for attitude, from 52.2±4.9 to 71.1±11.0; for school role, from 52±4.2 to 69.4±9.4; and for skills, from 56 ± 9.1 to 73.1±11.1. Meanwhile, the control group also experienced significant improvements in knowledge (p=0.003) and attitude (p=0.001), but the changes in school role (p=0.413) and skills (p=0.136) were not statistically significant. These findings indicate that the intervention group showed greater progress in knowledge, attitude, school role, and skills than the control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of research parameters in the intervention and control groups

The intervention group achieved significantly higher mean post-test scores than the control group across all assessed parameters (p<0.0001). For knowledge, the intervention group had a mean score of 69.7±9.8, while the control group scored 58.8±6.7. Regarding attitude, the intervention group’s mean score was 71.1±11.0, surpassing the control group’s score of 58.0±5.8. In the school role category, the intervention group scored an average of 69.4±9.3, while the control group’s average was 58.0±5.8. Lastly, for skills, the intervention group again outperformed the control group with a mean score of 73.1±11.0 compared to 58.8±6.7. These findings highlight the significant effectiveness of the intervention in enhancing students’ knowledge, attitudes, school roles, and skills (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean post-test scores of research parameters in the intervention and control groups

Discussion

This study aimed to explore how personal factors, attitudes, competencies, and school involvement influence students’ capacity to recognize the risks associated with breast cancer symptoms through participation in the SADARI program. The SADARI education had a significant impact on improving students’ knowledge, attitudes, school roles, and skills in identifying breast cancer risk signs and symptoms. In the intervention group, post-test scores across all parameters were notably higher than those in the control group. These results are consistent with prior studies that emphasize the success of health education programs in raising awareness and understanding of the importance of early breast cancer detection [25].

The significant increase in knowledge within the intervention group reflects the effective delivery of educational content designed to improve student understanding. The mean post-test knowledge score for the intervention group was considerably higher than that of the control group, suggesting that the program’s interactive and engaging approach enhanced students’ grasp of BSE as a preventive measure. This increase in knowledge is likely to foster positive behavioral changes by boosting the confidence of the participants [26], and heightened confidence contributes to improving students’ ability to perform BSE [27]. These results align with studies by Absavaran et al. [28], Pirzadeh et al. [29], and Ghaffari et al. [30] in Iran, showing significant improvements in knowledge about SBE through video-based multimedia education.

Along with the increase in knowledge, students’ attitudes toward the SADARI screening process also showed significant improvement. A more positive attitude suggests that students are more inclined to apply the knowledge they gained in their everyday routines. The mean attitude score for the intervention group was higher compared to the control group. This shift can be attributed to the educational strategy, which highlighted both the personal health advantages of SADARI and its importance as a societal responsibility. This improvement reflects another positive outcome of the intervention, which not only boosted participants’ knowledge but also influenced their attitudes. These findings align with those of Mohammad et al. [31], demonstrating the success of similar programs in enhancing female students’ attitudes toward breast cancer and BSE.

There was also a notable difference in school support between the intervention and control groups. The intervention group had a higher mean post-test score compared to the control group. The active participation of schools in fostering a supportive environment for health education plays a critical role in the success and long-term viability of such programs. Factors, such as allocating time for education, involving teachers, and providing oversight by school leaders all contribute to the program’s effectiveness. Previous research has shown that individuals who receive strong social support tend to have higher self-esteem, and there is a significant correlation between these two factors [28]. Additionally, strong social support and high self-esteem can enhance self-efficacy, which in turn improves the likelihood of performing BSE effectively [22].

Skill demonstrated the most significant improvement in the intervention group. This result highlights that, beyond theoretical knowledge, hands-on training through simulations and demonstrations greatly improves students’ ability to accurately conduct the SADARI examination. This skill is essential, as improper techniques can reduce the effectiveness of early breast cancer detection [32, 33].

The notable differences between the intervention and control groups in all parameters highlight the success of the educational intervention, which had a greater impact compared to the typical learning experience in the control group. While the control group did show some improvement, it was not as significant as the progress seen in the intervention group, emphasizing the importance of a more focused and organized approach to achieving substantial results.

These results highlight the importance of incorporating SADARI education programs at the secondary school level as part of broader breast cancer prevention efforts. By engaging both students and teachers, the program not only improves individual knowledge and skills but also fosters a school environment that is more attuned to the importance of breast health. This method is anticipated to serve as a prototype for comparable programs in different areas.

This study has a few limitations. Firstly, the use of a cross-sectional design means that causal relationships cannot be determined. Secondly, the brief duration of the intervention prevents an assessment of its long-term effects. The study’s ability to be generalized is also restricted, as it was carried out in only two high schools in Jambi City. Furthermore, relying on self-reported data introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, and assessing SADARI skills in a controlled setting may not fully represent how these skills are practiced in real-world scenarios.

We demonstrated that the SADARI education program has a notable positive effect on enhancing students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and the role of schools in promoting early breast cancer risk detection. The intervention group, which participated in the education program, showed significantly greater improvements than the control group across all measured parameters, with inferential analysis revealing statistically significant differences. These findings underscore the effectiveness of education-based interventions as a strategic approach to enhancing awareness and skills related to early breast cancer detection among students and teachers.

Conclusion

The SADARI educational program successfully improves students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and the support they receive from their schools.

Acknowledgments: We extend our heartfelt gratitude to everyone who contributed to this research. In particular, we would like to acknowledge the Head of the Health Polytechnic of Jambi and the Health Polytechnic of Padang for their invaluable support and guidance throughout this project. We are also grateful to the application development team for their insightful input during the research process.

Ethical Permissions: This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health, Jambi, under protocol number LB.02.06/5/168/2024. All procedures adhered to established research ethics standards, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights and privacy

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of intersts.

Authors' Contribution: Veriza E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Abbasiah A (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Nopindra A (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Widdefrita W (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by a grant from the Indonesian Ministry of Health.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2025/01/16 | Accepted: 2025/02/18 | Published: 2025/03/1

Received: 2025/01/16 | Accepted: 2025/02/18 | Published: 2025/03/1

References

1. Afifi AM, Saad AM, Al‐Husseini MJ, Elmehrath AO, Northfelt DW, Sonbol MB. Causes of death after breast cancer diagnosis: A US population‐based analysis. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1559-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cncr.32648]

2. Al Husaini MAS, Hadi Habaebi M, Gunawan TS, Islam MR. Self-detection of early breast cancer application with infrared camera and deep learning. Electronics. 2021;10(20):2538. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/electronics10202538]

3. WHO. Cancer Today [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2024, December, 21]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en. [Link]

4. Cescon DW, Kalinsky K, Parsons HA, Smith KL, Spears PA, Thomas A, et al. Therapeutic targeting of minimal residual disease to prevent late recurrence in hormone-receptor positive breast cancer: Challenges and new approaches. Front Oncol. 2022;11:667397. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fonc.2021.667397]

5. Aljohar BA, Kilani MA. Breast cancer in Europe: Epidemiology, risk factors, policies and strategies. A literature review. Glob J Health Sci. 2018;10(11):1. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v10n11p1]

6. Balali GI, Dekugmen Yar D, Gobe V, Effah-Yeboah E, Asumang P, Akoto JD, et al. Breast cancer: A review of mammography and clinical breast examination for early detection of cancer. Open Access Libr J. 2020;7:e6866. [Link] [DOI:10.4236/oalib.1106866]

7. Albeshan SM, Hossain SZ, Mackey MG, Brennan PC. Can breast self-examination and clinical breast examination along with increasing breast awareness facilitate earlier detection of breast cancer in populations with advanced stages at diagnosis?. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20(3):194-200. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.clbc.2020.02.001]

8. Tao Z, Shi A, Lu C, Song T, Zhang Z, Zhao J. Breast cancer: Epidemiology and etiology. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;72(2):333-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12013-014-0459-6]

9. Shulman LN, Willett W, Sievers A, Knaul FM. Breast cancer in developing countries: Opportunities for improved survival. J Oncol. 2010;2010(1):595167. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2010/595167]

10. UICC. GLOBOCAN 2020: New Global Cancer Data [Internet]. Geneva: :union: for International Cancer Control; 2020 [cited 2024, December, 19]. Available from: https://www.uicc.org/news/globocan-2020-new-global-cancer-data. [Link]

11. Sobri FB, Bachtiar A, Panigoro SS, Ayuningtyas D, Gustada H, Yuswar PW, et al. Factors affecting delayed presentation and diagnosis of breast Cancer in Asian developing countries women: A systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22(10):3081-92. [Link] [DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.10.3081]

12. Nuraini E, Hasida M. The relationship between young women's knowledge about breast cancer and self-breast examination (Sadari) at SMA Negeri 1 Panyabungan Selatan class. Benih J Midwifery. 2023;2(2):38-45. [Link] [DOI:10.54209/benih.v2i02.258]

13. Damayanti S, Apriani F, Nasution N, Miswarni M. Effectiveness educational video of breast self examination (BSE) on knowledge of young women. Sci Midwifery. 2024;12(3):1115-21. [Link]

14. Kurrohman T, Nurlita S. Factors associated with the achievement of early detection of breast cancer with the SADANIS method. J Multidiscip Acad Pract Stud. 2024;2(1):95-102. [Link] [DOI:10.35912/jomaps.v2i1.1986]

15. Wijaya ART, Milwati S, Yulindahwati A. The effect of demonstration on cadre skills in breast self-examination (SADARI). JURNAL PENDIDIKAN KESEHATAN. 2024;13(1):25-31. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.31290/jpk.v13i1.4137]

16. Syamsiah S, Lubis R, Rafika R. Level of pregnant women's knowledge and behavior on breast self-examination (Sadari) and its relationship with early detection of breast cancer. JURNAL KEBIDANAN MALAHAYATI. 2024;10(3):252-7. [Link] [DOI:10.33024/jkm.v10i3.14591]

17. Nahulae R, Nyorong M, Rifai A. Breast self-examination (SADARI) by teachers of methodist high school, Medan. J Wet Health. 2020;1(2):96-103. [Link] [DOI:10.48173/jwh.v1i2.43]

18. Soviadi NV, Hastono SP. A literature review: Relationship between peer group education and family support on the behavior of early detection of breast cancer by breast self-examination in adolescents. Faletehan Health J. 2023;10(2):185-92. [Link] [DOI:10.33746/fhj.v10i02.594]

19. Mekuria M, Nigusse A, Tadele A. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among secondary school female teachers in Gammo Gofa zone, southern, Ethiopia. Breast Cancer. 2020;12:1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/BCTT.S232021]

20. Champion V. The role of breast self‐examination in breast cancer screening. Cancer. 1992;69(Suppl 7):1985-91.

https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19920401)69:7+<1985::AID-CNCR2820691720>3.0.CO;2-C [Link] [DOI:10.1002/1097-0142(19920401)69:7+3.0.CO;2-C]

21. Kayode FO, Akande TM, Osagbemi GK. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self examination among female secondary school teachers in Ilorin, Nigeria. Eur J Sci Res. 2005;10(3):42-7. [Link]

22. Malak AT, Dicle A. Assessing the efficacy of a peer education model in teaching breast self-examination to university students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8(4):481-4. [Link]

23. Birhane N, Mamo A, Girma E, Asfaw S. Predictors of breast self-examination among female teachers in Ethiopia using health belief model. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):39. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13690-015-0087-7]

24. Tewelde B, Tamire M, Kaba M. Breast self-examination practice and predictors among female secondary school teachers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Using the health belief model. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):317. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12905-022-01904-w]

25. Chetlen A, Mack J, Chan T. Breast cancer screening controversies: Who, when, why, and how?. Clin Imaging. 2016;40(2):279-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.05.017]

26. Alameer A, Mahfouz MS, Alamir Y, Ali N, Darraj A. Effect of health education on female teachers' knowledge and practices regarding early breast cancer detection and screening in the Jazan area: A quasi-experimental study. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(5):865-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13187-018-1386-9]

27. Noman S, Shahar HK, Abdul Rahman H, Ismail S, Abdulwahid Al-Jaberi M, Azzani M. The effectiveness of educational interventions on breast cancer screening uptake, knowledge, and beliefs among women: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):263. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18010263]

28. Absavaran M, Niknami S, Zareban I. Effect of training through lecture and mobile phone on breast self-examination among nurses of Zabol Hospitals. PAYESH. 2015;14(3):363-73. [Persian] [Link]

29. Pirzadeh A, Ansari S, Golshiri P. The effects of educational intervention on breast self-examination and mammography behavior: Application of an integrated model. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10(1):196. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1119_20]

30. Ghaffari M, Esfahani SN, Rakhshanderou S, Koukamari PH. Evaluation of health belief model-based intervention on breast cancer screening behaviors among health volunteers. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(5):904-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13187-018-1394-9]

31. Mohammad FA, Bayoumi MM, Megahed MM. Efficacy of instructional training program in breast self-examination & breast screening for cancer among university students. Public Health Res. 2013;3(3):71-8. [Link]

32. Husna PH, Marni, Nurtanti S, Handayani S, Ratnasari NY, Ambarwati R, et al. Breast self-examination education for skill and behavior. Educ Health. 2019;32(2):101-2. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/efh.EfH_226_18]

33. Güçlü S, Tabak RS. Impact of health education on improving women's knowledge and awareness of breast cancer and breast self examination. Eur J Breast Health. 2013;9(1):18-22. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |