Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 133-138 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Darmawan A, Asrial A, Humaryanto H, Hasibuan H. Implications of Individual Factors and Physician Performance Regarding a Family Physician. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :133-138

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78998-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78998-en.html

1- Faculty of Mathematic and Science Programe, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

2- Department of Physics Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

3- Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

4- Department of Chemistry Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

2- Department of Physics Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

3- Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

4- Department of Chemistry Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

Keywords: Family Practice [MeSH], Primary Health Care [MeSH], Attitude to Health [MeSH], Decision Making [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 586 kb]

(197 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (221 Views)

Full-Text: (35 Views)

Introduction

Family medicine is a branch of healthcare that emphasizes providing comprehensive, sustainable, and patient-centered care within families and communities [1, 2]. Family physicians aim to improve efficiency through preventive measures and health promotion as a cornerstone of primary healthcare systems, ultimately reducing the burden on secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities [3, 4]. This approach fosters continuity of care and establishes long-term relationships between patients and healthcare providers, critical in ensuring holistic and coordinated healthcare delivery [5]. Globally, family medicine has been instrumental in addressing healthcare disparities, particularly in underserved populations, by integrating the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of care [6].

The role of family physicians extends beyond individual patient care to improving the overall health of communities [7]. In countries with well-established family medicine programs, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, family physicians are the first point of contact for medical care, offering a gateway to other healthcare services when necessary [8]. These countries have demonstrated the effectiveness of family medicine in reducing healthcare costs and improving health outcomes through robust primary healthcare systems [9, 10]. For instance, studies in the United States have shown that regions with higher concentrations of family physicians report lower hospitalization rates and better management of chronic diseases [11].

In contrast, many low- and middle-income countries face significant challenges in implementing the family physician model. In Iran, for example, the family physician program has been instrumental in improving rural healthcare delivery, particularly in underserved areas. Takian et al. [12] emphasize the role of an established primary healthcare network in supporting the success of the family physician program. Similarly, according to Bazyar et al. [13], factors such as healthcare infrastructure, physician-patient relationships, and community trust are critical to the program’s effectiveness. Despite these successes, gaps remain in scaling the model to urban and culturally diverse settings, as highlighted by Khatami et al. [14], who categorize factors influencing family physician selection into professional, social, and economic domains.

In Indonesia, family medicine is still an emerging concept, and public awareness remains relatively low compared to that in developed countries. Limited health literacy regarding the role of family physicians poses a significant barrier to optimizing primary healthcare services. Many individuals bypass primary care facilities, such as health centers or community clinics, opting for secondary or tertiary care without proper referrals [15]. This practice disrupts the referral system, resulting in overburdened hospitals and increased healthcare costs [16]. Moreover, cultural perceptions and economic constraints further complicate adopting family-oriented care models, particularly in diverse settings like Indonesia.

Jambi City, a rapidly urbanizing area in Sumatra, exemplifies these challenges. With its growing population and evolving healthcare needs, the city struggles to optimize primary healthcare utilization due to limited public awareness of the family physician model [17]. The referral system in Jambi City often operates inefficiently, placing undue pressure on secondary healthcare facilities and compromising the quality of care [18]. Addressing these issues requires targeted interventions to enhance community knowledge and attitudes toward family medicine while improving physician performance and accessibility [19].

Recent studies have highlighted the need for context-specific interventions to address these challenges in cities like Jambi. Integrating public health campaigns with existing healthcare infrastructure could be a practical solution for increasing public awareness about the family physician model [20]. Additionally, leveraging community-based initiatives, such as partnerships with local leaders and organizations, may enhance trust and encourage the adoption of family-centered healthcare services [21]. These strategies could further support health system reforms aimed at optimizing resource allocation, streamlining referral processes, and fostering long-term patient-provider relationships, thereby contributing to sustainable improvements in healthcare delivery.

Based on global evidence and local contexts, this study explored the relationship between individual factors, physician performance, and community decisions to engage family physicians in Jambi City. Specifically, it examined the role of knowledge, attitudes, and perceived physician quality in shaping healthcare utilization patterns. By focusing on Jambi City, the study addressed a critical gap in the literature, as most previous research has concentrated on Indonesia’s more developed regions, such as Jakarta and Java. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing context-specific strategies to strengthen primary healthcare services and promote equitable health access.

This study aimed to analyze the impact of individual factors and physician performance on primary health service utilization patterns in Jambi City. By identifying the factors that influence the use of these services, the study seeks to uncover effective strategies to enhance community health literacy. Additionally, the findings are expected to strengthen the primary healthcare system in Jambi City, making health services more efficient and equitable.

This study is both academically significant and holds considerable practical relevance. The findings are anticipated to inform the development of policies and public health education programs, particularly those aimed at promoting the family physician model. In doing so, this research will contribute to advancing a family-oriented healthcare system, which is fundamental to strengthening primary healthcare services.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This observational analytical study utilized a cross-sectional design. This approach facilitates the measurement of parameters at a single point in time, allowing for the description of population characteristics and the examination of the relationship between individual factors and physician performance regarding family physician utilization in Jambi City and the prevalence of having a family physician.

Participants

The study involved 601 respondents who were visitors to primary healthcare facilities in Jambi City. The sample size was determined using the Slovin formula based on a population of 640 individuals and a margin of error of 90%. Respondents were selected from three types of healthcare facilities: four public health centers, four private clinics, and four independent physician practices. Accidental sampling was employed, with participants chosen based on their availability and willingness to participate during their healthcare facility visits. The study was conducted over three months, from March to June 2023.

The inclusion criteria were individuals aged 18 years or older, residing in Jambi City, visiting primary healthcare facilities during the study period, willing to participate after providing informed consent, and able to read and comprehend the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria included health facility visitors experiencing acute conditions or medical emergencies that prevented them from completing the questionnaire and respondents who provided incomplete or invalid answers.

Data collection

Data collection followed systematic procedures to ensure the validity and quality of the obtained data. Before data collection, all respondents were provided with an explanation of the study’s purpose, the procedure for completing the questionnaire, and their rights as participants through an informed consent form. After providing consent, respondents completed a questionnaire containing questions regarding their factors, knowledge, attitudes, and performance related to family physicians and their status of having a permanent family physician. Data collection was facilitated by five enumerators who underwent training to ensure consistency and accuracy in completing the questionnaires. The enumerators were responsible for explaining the information to respondents as needed and ensuring that the questionnaires were completed correctly, following the established procedures.

We measured individual factors, family physicians' performance, and ownership of a family physician. Public knowledge of family physicians was assessed through 15 questions focusing on the fundamental concepts of family health services, including their holistic, comprehensive, integrated, continuous, and coordinated nature.

Attitude was assessed through a ten-item questionnaire utilizing a Likert scale to gauge perceptions of family physicians, with response options ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Similarly, performance was evaluated using a separate questionnaire with ten items and a Likert scale with response categories from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). A family physician was measured with two questions regarding whether respondents had a permanent family physician. Before administration, the questionnaire underwent validity and reliability testing.

The results of the validity and reliability tests indicated that the tools used in this study were of high quality for measuring the parameters. For knowledge, attitude, and performance related to family physicians, the validity test revealed that all question items had a significant correlation coefficient, with an r value exceeding 0.30, indicating that the questions effectively assess respondents’ understanding of the core concepts of family physicians. Additionally, the reliability test using Cronbach’s alpha yielded a value of 0.85, indicating a high level of internal consistency and suggesting that the instrument is reliable for measuring knowledge, attitude, and performance related to family physicians. No validity test was conducted for having a family physician, as it was measured with only two questions.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted through two primary approaches: univariate and inferential. The univariate analysis aimed to describe the respondent characteristics, including demographic factors such as age, gender, employment status, education level, marital status, and income. These characteristics were summarized using frequency distributions and percentages, providing a clear overview of the study population.

Inferential analysis was used to explore the relationship between individual factors, the performance of family physicians, and having a family physician. The Chi-square test was applied to examine the association between two categorical parameters, with a significance threshold set at 0.05. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant relationship between the parameters. Additionally, the phi coefficient was used to measure the strength of the relationship between the parameters. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression was employed to evaluate the influence of individual factors on the likelihood of having a family physician. The magnitude of confounding was also calculated to assess the influence of confounding factors on the relationship being studied. All data analysis was performed using SPSS 23 software, ensuring precise and efficient statistical computations.

Findings

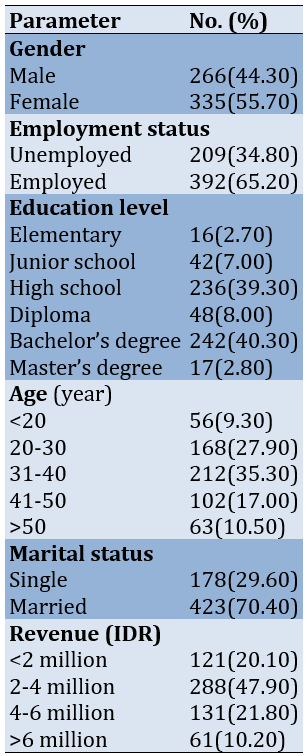

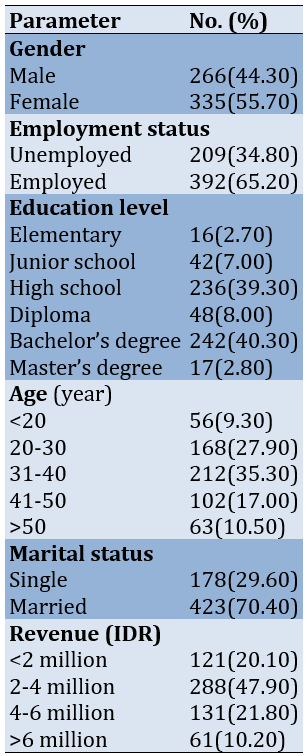

Most subjects were female, with a higher proportion of employed individuals. Most respondents had completed high school or held a bachelor’s degree. The largest age group was between 31 and 40; most respondents were married. In terms of income, a significant number of respondents earned between 2 and 4 million (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of participants’ characteristics

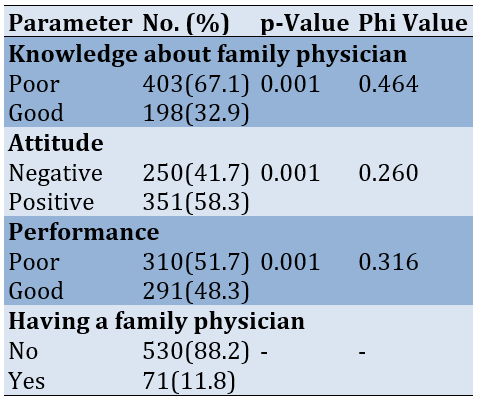

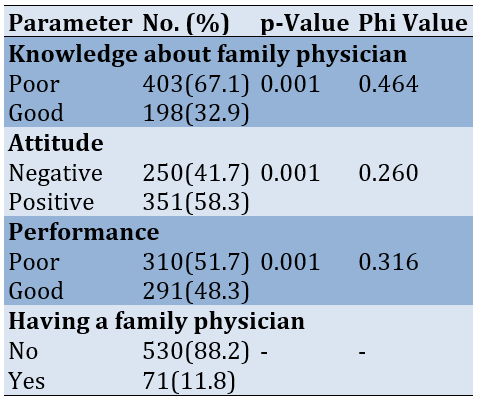

Most respondents lacked sufficient knowledge about family doctors, with a significant proportion demonstrating poor knowledge. Attitudes toward family doctors were generally positive, although a notable portion held negative attitudes. Regarding physician performance, a majority rated family doctors’ performance poorly, while a smaller group rated it positively. Furthermore, most respondents did not have a family doctor, highlighting a potential gap in adopting family-based healthcare services. The correlation coefficient (phi value) showed a moderate relationship between knowledge and having a family physician, a weak relationship between attitude and having a family physician, and a weak relationship between performance and having a family physician (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between individual factors and physician performance and family physician ownership

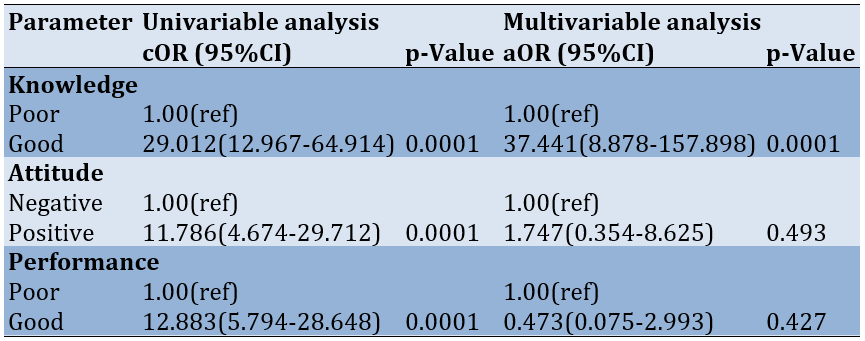

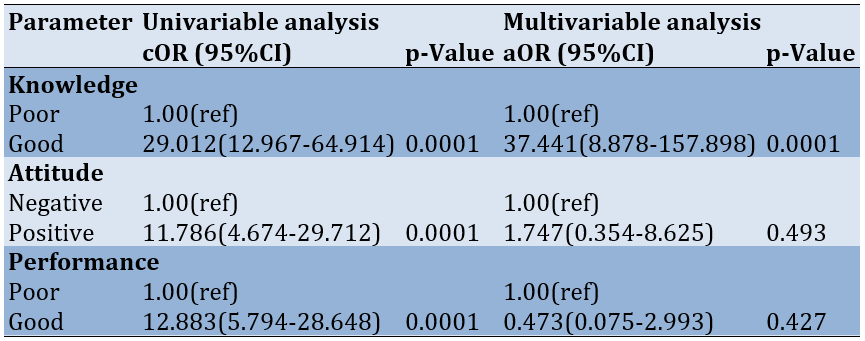

Good knowledge was strongly associated with improved outcomes, while a positive attitude and favorable performance evaluations were linked to better outcomes but did not show a statistically significant impact in the multivariate analysis. Only good knowledge remained a significant predictor of positive outcomes, suggesting that enhancing knowledge may be a key factor in improving healthcare utilization and decision-making. The calculation of the magnitude of confounding indicated that all parameters had a difference in cOR and aOR greater than 10%, suggesting that the presence or absence of a relationship between the predictor parameters and family physician ownership was influenced by other parameters (Table 3).

Table 3. Binary logistic regression analysis for predicting family physician ownership

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate how individual factors and physician performance influence community decisions to engage a family physician in Jambi City. Awareness of the family doctor concept in Jambi City remains relatively low; 67.1% of respondents demonstrated inadequate knowledge about family doctors, indicating a limited understanding of their roles and benefits, such as disease prevention, coordination of care, and a comprehensive approach to health management. This knowledge gap presents a significant obstacle to optimizing family-based primary healthcare services in the region.

Community attitudes toward family doctors were mixed. While 58.3% of respondents exhibited a positive attitude, 41.7% expressed a negative view. Negative perceptions may stem from unsatisfactory past experiences with healthcare services or skepticism about the effectiveness of family doctors. Nevertheless, the majority’s positive attitude represents an opportunity to enhance the utilization of family doctor services through targeted awareness and education initiatives.

The performance of family doctors emerged as a critical factor influencing public trust in the service. Here, 51.7% of respondents rated family doctors’ performance as suboptimal, whereas 48.3% provided favorable evaluations. These findings highlight the necessity for improvements in professionalism, training, and collaboration between family doctors and other healthcare providers to deliver high-quality services that align with community expectations. This is in line with the study conducted by Bornstein et al. [6], which states that the most dominant reason for people determining the ownership of a primary care doctor (PCD) is the quality of service provided by the PCD.

Socio-demographic factors play a significant role in the uptake of family doctor services [16, 22]. Individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to understand the value of having a family doctor, which influences their decision to utilize these services. Similarly, income levels also impact those with higher incomes, who are better positioned to access family doctor services, which may be perceived as a supplementary healthcare option [23]. In line with the study by Khatami et al. [14], the most fundamental reason for choosing a family physician is that parameter, such as being a fellow citizen, having the same gender, and the physician’s appearance, were the least important.

The rate of family doctor ownership in Jambi City remains alarmingly low, with 88.2% of respondents reporting that they did not have a family doctor. This highlights a substantial disparity between the availability of primary healthcare services and the community’s needs. Several factors may contribute to this low ownership rate, including limited awareness, a lack of accessible services within proximity, or the belief that family doctor services are unnecessary [24, 25].

This situation contributes to inefficiencies in the health referral system. Many individuals bypass family doctors as the initial point of care, directly accessing secondary or tertiary healthcare services [26-28]. This has led to overcrowding in hospitals and advanced health facilities, while the potential role of family doctors as primary care coordinators remains underutilized. Such inefficiencies significantly challenge achieving an effective and streamlined healthcare system [29, 30].

A comprehensive approach is essential to address this issue to enhance awareness and encourage greater utilization of family doctor services. Public education initiatives, including social media campaigns, health workshops, and the integration of the importance of family doctors into school curricula, can serve as critical starting points. Additionally, the government should focus on improving access to family doctor services by incentivizing practitioners to serve in underserved or remote areas and maintaining consistent service quality. These measures aim to increase public awareness and engagement with family doctor services, fostering a more efficient and equitable healthcare system.

Regarding the study's limitations, it should be noted that accidental sampling may lead to selection bias that can affect the results; therefore, in the future, sampling should be done randomly.

Public awareness and perceptions of family doctors in Jambi City remain limited, with most respondents reporting that they do not have a family doctor. Key barriers to adopting a family-based healthcare model include insufficient knowledge, unfavorable attitudes, and inadequate evaluations of service performance. Furthermore, the underutilization of family doctors contributes to inefficiencies in the referral system, placing additional strain on secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities. To address these challenges, it is essential to implement stronger educational campaigns, enhance access to family doctor services, and improve service quality to promote broader acceptance and usage of these essential healthcare resources.

Conclusion

Limited knowledge, unfavorable attitudes, and suboptimal perceptions of physician performance are key barriers to adopting family-based healthcare services in Jambi City.

Acknowledgments: Gratitude is expressed to all those who have contributed to this research, especially to the Dean of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Education at Jambi University, who has provided substantial support. This includes the respondents who took the time to provide valuable information for this survey. Appreciation is also extended to the health centers, private clinics, and independent practicing physicians who have been willing to serve as research locations by facilitating data collection.

Ethical Permissions: This study received a letter of permission to conduct the research from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Jambi, Indonesia (No.: 573/UN21.8/PT.01.04/2024), and all participants signed an informed consent form before data collection.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Darmawan A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Asrial A (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%); Humaryanto H (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Hasibuan HE (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: No funding or financial support was received for the implementation of this research.

Family medicine is a branch of healthcare that emphasizes providing comprehensive, sustainable, and patient-centered care within families and communities [1, 2]. Family physicians aim to improve efficiency through preventive measures and health promotion as a cornerstone of primary healthcare systems, ultimately reducing the burden on secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities [3, 4]. This approach fosters continuity of care and establishes long-term relationships between patients and healthcare providers, critical in ensuring holistic and coordinated healthcare delivery [5]. Globally, family medicine has been instrumental in addressing healthcare disparities, particularly in underserved populations, by integrating the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of care [6].

The role of family physicians extends beyond individual patient care to improving the overall health of communities [7]. In countries with well-established family medicine programs, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, family physicians are the first point of contact for medical care, offering a gateway to other healthcare services when necessary [8]. These countries have demonstrated the effectiveness of family medicine in reducing healthcare costs and improving health outcomes through robust primary healthcare systems [9, 10]. For instance, studies in the United States have shown that regions with higher concentrations of family physicians report lower hospitalization rates and better management of chronic diseases [11].

In contrast, many low- and middle-income countries face significant challenges in implementing the family physician model. In Iran, for example, the family physician program has been instrumental in improving rural healthcare delivery, particularly in underserved areas. Takian et al. [12] emphasize the role of an established primary healthcare network in supporting the success of the family physician program. Similarly, according to Bazyar et al. [13], factors such as healthcare infrastructure, physician-patient relationships, and community trust are critical to the program’s effectiveness. Despite these successes, gaps remain in scaling the model to urban and culturally diverse settings, as highlighted by Khatami et al. [14], who categorize factors influencing family physician selection into professional, social, and economic domains.

In Indonesia, family medicine is still an emerging concept, and public awareness remains relatively low compared to that in developed countries. Limited health literacy regarding the role of family physicians poses a significant barrier to optimizing primary healthcare services. Many individuals bypass primary care facilities, such as health centers or community clinics, opting for secondary or tertiary care without proper referrals [15]. This practice disrupts the referral system, resulting in overburdened hospitals and increased healthcare costs [16]. Moreover, cultural perceptions and economic constraints further complicate adopting family-oriented care models, particularly in diverse settings like Indonesia.

Jambi City, a rapidly urbanizing area in Sumatra, exemplifies these challenges. With its growing population and evolving healthcare needs, the city struggles to optimize primary healthcare utilization due to limited public awareness of the family physician model [17]. The referral system in Jambi City often operates inefficiently, placing undue pressure on secondary healthcare facilities and compromising the quality of care [18]. Addressing these issues requires targeted interventions to enhance community knowledge and attitudes toward family medicine while improving physician performance and accessibility [19].

Recent studies have highlighted the need for context-specific interventions to address these challenges in cities like Jambi. Integrating public health campaigns with existing healthcare infrastructure could be a practical solution for increasing public awareness about the family physician model [20]. Additionally, leveraging community-based initiatives, such as partnerships with local leaders and organizations, may enhance trust and encourage the adoption of family-centered healthcare services [21]. These strategies could further support health system reforms aimed at optimizing resource allocation, streamlining referral processes, and fostering long-term patient-provider relationships, thereby contributing to sustainable improvements in healthcare delivery.

Based on global evidence and local contexts, this study explored the relationship between individual factors, physician performance, and community decisions to engage family physicians in Jambi City. Specifically, it examined the role of knowledge, attitudes, and perceived physician quality in shaping healthcare utilization patterns. By focusing on Jambi City, the study addressed a critical gap in the literature, as most previous research has concentrated on Indonesia’s more developed regions, such as Jakarta and Java. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing context-specific strategies to strengthen primary healthcare services and promote equitable health access.

This study aimed to analyze the impact of individual factors and physician performance on primary health service utilization patterns in Jambi City. By identifying the factors that influence the use of these services, the study seeks to uncover effective strategies to enhance community health literacy. Additionally, the findings are expected to strengthen the primary healthcare system in Jambi City, making health services more efficient and equitable.

This study is both academically significant and holds considerable practical relevance. The findings are anticipated to inform the development of policies and public health education programs, particularly those aimed at promoting the family physician model. In doing so, this research will contribute to advancing a family-oriented healthcare system, which is fundamental to strengthening primary healthcare services.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This observational analytical study utilized a cross-sectional design. This approach facilitates the measurement of parameters at a single point in time, allowing for the description of population characteristics and the examination of the relationship between individual factors and physician performance regarding family physician utilization in Jambi City and the prevalence of having a family physician.

Participants

The study involved 601 respondents who were visitors to primary healthcare facilities in Jambi City. The sample size was determined using the Slovin formula based on a population of 640 individuals and a margin of error of 90%. Respondents were selected from three types of healthcare facilities: four public health centers, four private clinics, and four independent physician practices. Accidental sampling was employed, with participants chosen based on their availability and willingness to participate during their healthcare facility visits. The study was conducted over three months, from March to June 2023.

The inclusion criteria were individuals aged 18 years or older, residing in Jambi City, visiting primary healthcare facilities during the study period, willing to participate after providing informed consent, and able to read and comprehend the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria included health facility visitors experiencing acute conditions or medical emergencies that prevented them from completing the questionnaire and respondents who provided incomplete or invalid answers.

Data collection

Data collection followed systematic procedures to ensure the validity and quality of the obtained data. Before data collection, all respondents were provided with an explanation of the study’s purpose, the procedure for completing the questionnaire, and their rights as participants through an informed consent form. After providing consent, respondents completed a questionnaire containing questions regarding their factors, knowledge, attitudes, and performance related to family physicians and their status of having a permanent family physician. Data collection was facilitated by five enumerators who underwent training to ensure consistency and accuracy in completing the questionnaires. The enumerators were responsible for explaining the information to respondents as needed and ensuring that the questionnaires were completed correctly, following the established procedures.

We measured individual factors, family physicians' performance, and ownership of a family physician. Public knowledge of family physicians was assessed through 15 questions focusing on the fundamental concepts of family health services, including their holistic, comprehensive, integrated, continuous, and coordinated nature.

Attitude was assessed through a ten-item questionnaire utilizing a Likert scale to gauge perceptions of family physicians, with response options ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Similarly, performance was evaluated using a separate questionnaire with ten items and a Likert scale with response categories from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). A family physician was measured with two questions regarding whether respondents had a permanent family physician. Before administration, the questionnaire underwent validity and reliability testing.

The results of the validity and reliability tests indicated that the tools used in this study were of high quality for measuring the parameters. For knowledge, attitude, and performance related to family physicians, the validity test revealed that all question items had a significant correlation coefficient, with an r value exceeding 0.30, indicating that the questions effectively assess respondents’ understanding of the core concepts of family physicians. Additionally, the reliability test using Cronbach’s alpha yielded a value of 0.85, indicating a high level of internal consistency and suggesting that the instrument is reliable for measuring knowledge, attitude, and performance related to family physicians. No validity test was conducted for having a family physician, as it was measured with only two questions.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted through two primary approaches: univariate and inferential. The univariate analysis aimed to describe the respondent characteristics, including demographic factors such as age, gender, employment status, education level, marital status, and income. These characteristics were summarized using frequency distributions and percentages, providing a clear overview of the study population.

Inferential analysis was used to explore the relationship between individual factors, the performance of family physicians, and having a family physician. The Chi-square test was applied to examine the association between two categorical parameters, with a significance threshold set at 0.05. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant relationship between the parameters. Additionally, the phi coefficient was used to measure the strength of the relationship between the parameters. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression was employed to evaluate the influence of individual factors on the likelihood of having a family physician. The magnitude of confounding was also calculated to assess the influence of confounding factors on the relationship being studied. All data analysis was performed using SPSS 23 software, ensuring precise and efficient statistical computations.

Findings

Most subjects were female, with a higher proportion of employed individuals. Most respondents had completed high school or held a bachelor’s degree. The largest age group was between 31 and 40; most respondents were married. In terms of income, a significant number of respondents earned between 2 and 4 million (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of participants’ characteristics

Most respondents lacked sufficient knowledge about family doctors, with a significant proportion demonstrating poor knowledge. Attitudes toward family doctors were generally positive, although a notable portion held negative attitudes. Regarding physician performance, a majority rated family doctors’ performance poorly, while a smaller group rated it positively. Furthermore, most respondents did not have a family doctor, highlighting a potential gap in adopting family-based healthcare services. The correlation coefficient (phi value) showed a moderate relationship between knowledge and having a family physician, a weak relationship between attitude and having a family physician, and a weak relationship between performance and having a family physician (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between individual factors and physician performance and family physician ownership

Good knowledge was strongly associated with improved outcomes, while a positive attitude and favorable performance evaluations were linked to better outcomes but did not show a statistically significant impact in the multivariate analysis. Only good knowledge remained a significant predictor of positive outcomes, suggesting that enhancing knowledge may be a key factor in improving healthcare utilization and decision-making. The calculation of the magnitude of confounding indicated that all parameters had a difference in cOR and aOR greater than 10%, suggesting that the presence or absence of a relationship between the predictor parameters and family physician ownership was influenced by other parameters (Table 3).

Table 3. Binary logistic regression analysis for predicting family physician ownership

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate how individual factors and physician performance influence community decisions to engage a family physician in Jambi City. Awareness of the family doctor concept in Jambi City remains relatively low; 67.1% of respondents demonstrated inadequate knowledge about family doctors, indicating a limited understanding of their roles and benefits, such as disease prevention, coordination of care, and a comprehensive approach to health management. This knowledge gap presents a significant obstacle to optimizing family-based primary healthcare services in the region.

Community attitudes toward family doctors were mixed. While 58.3% of respondents exhibited a positive attitude, 41.7% expressed a negative view. Negative perceptions may stem from unsatisfactory past experiences with healthcare services or skepticism about the effectiveness of family doctors. Nevertheless, the majority’s positive attitude represents an opportunity to enhance the utilization of family doctor services through targeted awareness and education initiatives.

The performance of family doctors emerged as a critical factor influencing public trust in the service. Here, 51.7% of respondents rated family doctors’ performance as suboptimal, whereas 48.3% provided favorable evaluations. These findings highlight the necessity for improvements in professionalism, training, and collaboration between family doctors and other healthcare providers to deliver high-quality services that align with community expectations. This is in line with the study conducted by Bornstein et al. [6], which states that the most dominant reason for people determining the ownership of a primary care doctor (PCD) is the quality of service provided by the PCD.

Socio-demographic factors play a significant role in the uptake of family doctor services [16, 22]. Individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to understand the value of having a family doctor, which influences their decision to utilize these services. Similarly, income levels also impact those with higher incomes, who are better positioned to access family doctor services, which may be perceived as a supplementary healthcare option [23]. In line with the study by Khatami et al. [14], the most fundamental reason for choosing a family physician is that parameter, such as being a fellow citizen, having the same gender, and the physician’s appearance, were the least important.

The rate of family doctor ownership in Jambi City remains alarmingly low, with 88.2% of respondents reporting that they did not have a family doctor. This highlights a substantial disparity between the availability of primary healthcare services and the community’s needs. Several factors may contribute to this low ownership rate, including limited awareness, a lack of accessible services within proximity, or the belief that family doctor services are unnecessary [24, 25].

This situation contributes to inefficiencies in the health referral system. Many individuals bypass family doctors as the initial point of care, directly accessing secondary or tertiary healthcare services [26-28]. This has led to overcrowding in hospitals and advanced health facilities, while the potential role of family doctors as primary care coordinators remains underutilized. Such inefficiencies significantly challenge achieving an effective and streamlined healthcare system [29, 30].

A comprehensive approach is essential to address this issue to enhance awareness and encourage greater utilization of family doctor services. Public education initiatives, including social media campaigns, health workshops, and the integration of the importance of family doctors into school curricula, can serve as critical starting points. Additionally, the government should focus on improving access to family doctor services by incentivizing practitioners to serve in underserved or remote areas and maintaining consistent service quality. These measures aim to increase public awareness and engagement with family doctor services, fostering a more efficient and equitable healthcare system.

Regarding the study's limitations, it should be noted that accidental sampling may lead to selection bias that can affect the results; therefore, in the future, sampling should be done randomly.

Public awareness and perceptions of family doctors in Jambi City remain limited, with most respondents reporting that they do not have a family doctor. Key barriers to adopting a family-based healthcare model include insufficient knowledge, unfavorable attitudes, and inadequate evaluations of service performance. Furthermore, the underutilization of family doctors contributes to inefficiencies in the referral system, placing additional strain on secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities. To address these challenges, it is essential to implement stronger educational campaigns, enhance access to family doctor services, and improve service quality to promote broader acceptance and usage of these essential healthcare resources.

Conclusion

Limited knowledge, unfavorable attitudes, and suboptimal perceptions of physician performance are key barriers to adopting family-based healthcare services in Jambi City.

Acknowledgments: Gratitude is expressed to all those who have contributed to this research, especially to the Dean of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Education at Jambi University, who has provided substantial support. This includes the respondents who took the time to provide valuable information for this survey. Appreciation is also extended to the health centers, private clinics, and independent practicing physicians who have been willing to serve as research locations by facilitating data collection.

Ethical Permissions: This study received a letter of permission to conduct the research from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Jambi, Indonesia (No.: 573/UN21.8/PT.01.04/2024), and all participants signed an informed consent form before data collection.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Darmawan A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Asrial A (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%); Humaryanto H (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Hasibuan HE (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: No funding or financial support was received for the implementation of this research.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Social Health

Received: 2025/01/4 | Accepted: 2025/02/7 | Published: 2025/02/25

Received: 2025/01/4 | Accepted: 2025/02/7 | Published: 2025/02/25

References

1. Freeman TR. McWhinney's textbook of family medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/med/9780199370689.001.0001]

2. Sloane PD. Essentials of family medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Link]

3. Lee A, Siu S, Lam A, Tsang C, Kung K, Li PKT. The concepts of family doctor and factors affecting choice of family doctors among Hong Kong people. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16(2):106-15. [Link]

4. Gropper M. Family medicine and psychosocial knowledge: How many hats can the family doctor wear?. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(11):1249-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0277-9536(87)90372-8]

5. Lam CLK, Yu EYT, Lo YYC, Wong CKH, Mercer SM, Fong DYT, et al. Having a family doctor is associated with some better patient-reported outcomes of primary care consultations. Front Med. 2014;1:29. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2014.00029]

6. Bornstein BH, Marcus D, Cassidy W. Choosing a doctor: An exploratory study of factors influencing patients' choice of a primary care doctor. J Eval Clin Pract. 2000;6(3):255-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00256.x]

7. Aljurbua FIH, Asiri HAAM, Al-Anazi HBM, Al-Otaibi BA, Alotaibi HKS. Comprehensive care: The integral role of family physicians in patient well-being. Tec Empres. 2024;6(2). [Link]

8. Cassell EJ. Doctoring: The nature of primary care medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Link]

9. Blustein J. The family in medical decisionmaking. Hastings Cent Rep. 1993;23(3):6-13. [Link] [DOI:10.2307/3563360]

10. Tollman S. Community oriented primary care: Origins, evolution, applications. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):633-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90142-Y]

11. Daaleman TP, Elder GH. Family medicine and the life course paradigm. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(1):85-92. [Link] [DOI:10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060012]

12. Takian A, Doshmangir L, Rashidian A. Implementing family physician programme in rural Iran: Exploring the role of an existing primary health care network. Fam Pract. 2013;30(5):551-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/fampra/cmt025]

13. Bazyar M, Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, Bahmani M, Sadeghifar J, Momeni K, Shaabani Z. Preferences of people in choosing a family physician in rural areas: A qualitative inquiry from Iran. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2022;23:e57. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1463423622000317]

14. Khatami F, Shariati M, Khedmat L, Bahmani M. Patients' preferences in selecting family physician in primary health centers: A qualitative-quantitative approach. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):107. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12875-020-01181-2]

15. Kurniawan H. Physicians in primary care with a family medicine approach in the health care system. JURNAL KEDOKTERAN SYIAH KUALA. 2015;15(2):114-9. [Indonesian] [Link]

16. Mainous AG. Future challenges for family medicine education research. Fam Med. 2022;54(3):173-5. [Link] [DOI:10.22454/FamMed.2022.755008]

17. Ie K, Tahara M, Murata A, Komiyama M, Onishi H. Factors associated to the career choice of family medicine among Japanese physicians: The dawn of a new era. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:11. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12930-014-0011-2]

18. Akyon SH, Yilmaz TE, Ozkara A. Determinants of choosing family medicine as a specialty for young doctors. ACH Med J. 2023;3:51-9. [Link] [DOI:10.5505/achmedj.2023.55265]

19. Aslam F, Aftab O, Janjua NZ. Medical decision making: The family-doctor-patient triad. PLoS Med. 2005;2(6):e129. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020129]

20. Committee on Integrating Primary Care and Public Health; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine. Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [Link]

21. Sørensen K, Van Den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-80]

22. Hoff T, Stephenson A. Changes in career thinking and work intentions among family medicine educators in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(5):933-9. [Link]

23. Ross JS, Bradley EH, Busch SH. Use of health care services by lower-income and higher-income uninsured adults. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2027-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.295.17.2027]

24. Goudge J, Gilson L, Russell S, Gumede T, Mills A. Affordability, availability and acceptability barriers to health care for the chronically ill: Longitudinal case studies from South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:75. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1472-6963-9-75]

25. Field KS, Briggs DJ. Socio‐economic and locational determinants of accessibility and utilization of primary health‐care. Health Soc Care Community. 2001;9(5):294-308. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.0966-0410.2001.00303.x]

26. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x]

27. Okkes IM, Polderman GO, Fryer GE, Yamada T, Bujak M, Oskam SK, et al. The role of family practice in different health care systems: A comparison of reasons for encounter, diagnoses, and interventions in primary care populations in the Netherlands, Japan, Poland, and the United States. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(1):72-3. [Link]

28. Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families' health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):e1332-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1542/peds.2006-1505]

29. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice?. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1246-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.291.10.1246]

30. Shi L. The impact of primary care: A focused review. Scientifica. 2012;2012(1):432892. [Link] [DOI:10.6064/2012/432892]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |