Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 81-87 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bahmani A, Akhondzadeh E, Hosseinzadeh S, Gharibi F. Effect of Theory of Planned Behavior-Based Education on Fast Food Consumption in Female High School Students. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :81-87

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78912-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78912-en.html

1- Public Health Department, Health Faculty, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

Keywords: Health Education [MeSH], Theory of Planned Behavior [MeSH], Fast Food [MeSH], Students [MeSH], Female [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 692 kb]

(465 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (617 Views)

Full-Text: (69 Views)

Introduction

Nutrition plays a crucial role in the growth and enhancement of physical and mental health, particularly during adolescence. This sensitive and vital period has unique nutritional needs, and neglecting these needs can lead to chronic disorders and diseases, including stunted growth, malnutrition, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases [1]. Studies indicate that 70% of overweight adolescents are likely to become obese in adulthood [2], and Iranian society is expected to face an obesity epidemic in the coming decades [3, 4]. Adolescent girls require special attention due to the physiological changes associated with puberty, menstruation, and increased nutritional needs. They are more susceptible to iron deficiency anemia and malnutrition. Given that today’s adolescent girls are tomorrow’s mothers and the educators of future generations, they have a unique need for nutritional education [3].

In recent years, with changing lifestyles, the consumption of fast food among teenagers and young adults has increased significantly [5, 6]. These foods, which include items such as sandwiches, hamburgers, sausages, cold cuts, pizza, fried foods, and snacks, are often high in calories, trans fats, additives, and flavorings [7, 8]. Globally, about a quarter of the U.S. population uses fast-food restaurant services. In Iran, households spent 2% of their total expenses on fast food by the end of 2015 [9]. Unhealthy nutrition accounts for 35% of cancer-related deaths, underscoring the importance of correcting dietary patterns during childhood and adolescence [3].

Given the importance of students in the future of the country, as well as the cost-effectiveness and efficacy of health and nutrition education programs in schools, and considering that many eating habits and preferences of children and adolescents are formed in school and influenced by their classmates, appropriate educational interventions are necessary to reduce the consumption of fast foods [10]. Research demonstrates that nutrition education in schools significantly improves students’ knowledge and behavior [11]. For instance, nutrition education programs for female middle school students in Torbate-Heydariyeh and Birjand have shown positive effects on students’ nutritional knowledge and behavior [4, 10].

Health education models and theories provide a framework for understanding health behaviors and designing effective interventions. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been widely used to study attitudes and beliefs related to food choices [10, 12, 13]. This theory includes four key constructs, including behavioral intention, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Behavioral intention reflects an individual’s willingness to consume fast food. Attitude refers to the individual’s positive or negative evaluation of the behavior. Subjective norms encompass perceived social pressures, while perceived behavioral control indicates the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior [14]. The reason for choosing this theory compared to other psychological theories such as the health belief model (HBM), social cognitive theory (SCT), and transtheoretical model (TTM) is that the TPB, in addition to individual factors, pays special attention to social factors that play a key role in shaping behavior. The most important parameter of this theory, namely behavioral intention, influences the individual’s motivation to change behavior, which the aforementioned theories are not able to measure simultaneously [15-17].

However, the application of the TPB in the context of fast food consumption among female high school students in Iran has been poorly studied. This study addressed this gap by targeting a specific demographic at high risk for poor dietary habits and related health issues. By focusing on adolescent girls, this study provides novel insights into how educational interventions based on the TPB affect fast food consumption, contributing to improved health outcomes for this vulnerable group.

In light of the increasing tendency of adolescents and young adults to consume fast food and its adverse health consequences, this study aimed to investigate the effect of an educational program based on the TPB on reducing fast food consumption among female high school students.

Materials and Methods

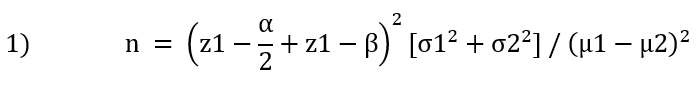

This intervention study employed a pre-and post-intervention design and included 100 female high school students from two schools under the jurisdiction of the District 4 education authority in Tehran in the year 2024. One school was designated as the control group (50 students), and the other as the intervention group (50 students). From each school, three classes (one from each grade) were randomly selected. Based on the study’s objectives and similar research [9], a 95% confidence interval and 90% power were assumed to determine the sample size. If the change in the behavioral intention score from one person to another is around three points and its standard deviation is 0.3, then the sample size using Formula 1 was determined to be 38 individuals per group. Ultimately, 50 individuals per group were included in the study to increase accuracy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included students who were physically and mentally healthy and willing to participate. Exclusion criteria consisted of unwillingness to continue participating in the educational sessions or illness during the study period.

Data collection tool

The data collection tool in this study was a questionnaire whose validity and reliability had been assessed by relevant specialists. To ensure the face and content validity of the questionnaire, the adjusted scale was presented to five health education professors and two indices, the content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity index (CVI), were calculated [9]. The overall validity of the questionnaire was 0.84. The questionnaire included demographic information, awareness assessment, and various dimensions of the TPB. The reliability of the questionnaire, based on Cronbach’s alpha test, was 0.87. Additionally, the reliability of each construct, based on Cronbach’s alpha test, was 0.85 for knowledge, 0.74 for attitude, 0.84 for subjective norms, 0.70 for perceived behavioral control, 0.91 for behavioral intention, and 0.74 for behavior.

The questionnaire included 72 questions; eight questions on demographic characteristics, 18 questions assessing knowledge using a three-option scale (correct, don’t know, incorrect), nine questions on attitude, nine questions on subjective norms, six questions on perceived behavioral control, seven questions on behavioral intention, and 15 questions on fast food consumption.

The constructs of the TPB were measured using a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree).

Educational intervention

Before the educational intervention, the aforementioned questionnaire was distributed among the students in both the test and control groups. The education was based on the TPB and consisted of three fifty-minute training sessions for the students in the test group. Each session began with a five-minute question-and-answer segment, followed by a thirty-minute lecture and slide presentation on the definition of fast food, its harms and disadvantages, and its ingredients and components. The sessions concluded with a fifteen-minute question-and-answer segment. To supplement the education, the project executor prepared and distributed brochures on fast food consumption and its side effects among the participants. The source used for education and the preparation of educational materials, such as brochures and posters, was Dr. Mohammad Daryaei’s book, “Fast Foods (Toxic Foods) and Unpleasant Beverages,” a specialist in biological sciences and medicinal plants [18]. After providing the necessary education and concluding the classes, the questionnaire was redistributed and completed by the students in both the test and control groups.

Data analysis

Finally, the collected data were analyzed using SPSS 22 software. Descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequency, mean, standard deviation, and range, as well as analytical statistics, including the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check for normal data distribution, the independent t-test (Mann-Whitney U test) for comparing quantitative parameters between the intervention and control groups, and the Chi-square test for comparing nominal parameters between the two groups, were utilized.

Findings

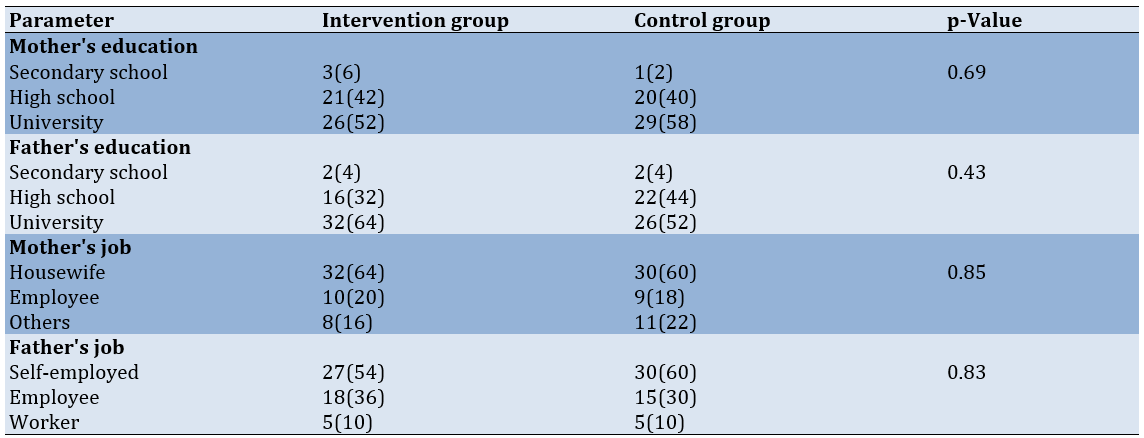

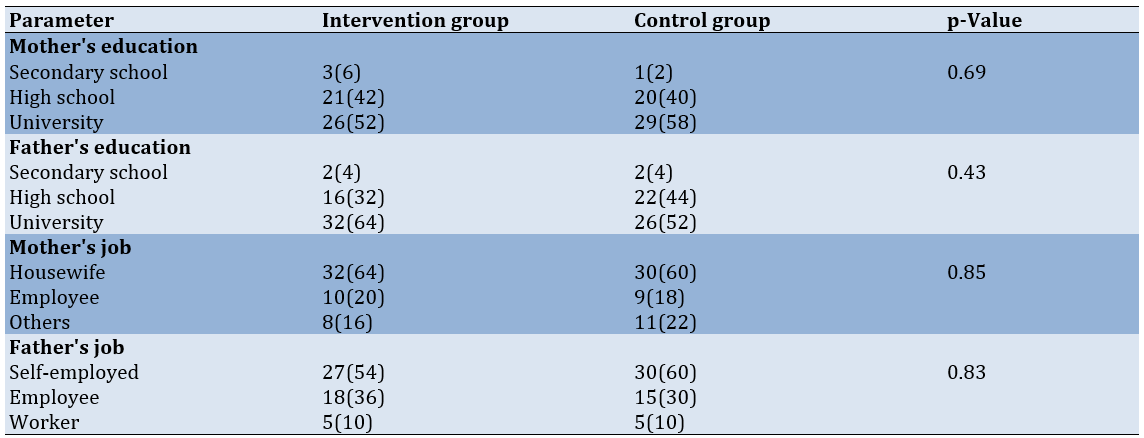

The ages of all participating students ranged from 14 to 16 years. The average age of the students’ mothers was 41.9±4.4 years in the control group and 40.5±4.5 years in the intervention group. The average age of the students’ fathers was 45.5±7.9 years in the control group and 45.0±3.9 years in the intervention group. According to the independent t-test, there was no statistically significant difference in age between the intervention and control groups (p=0.122 for fathers’ age, p = 0.667 for mothers’ age). Additionally, no statistically significant differences were observed in other demographic parameters, such as parental education, occupation, or the students’ field of study, between the two groups. This indicates that the groups were homogeneous at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1. The control and intervention groups' absolute and relative frequency distribution of demographic parameters

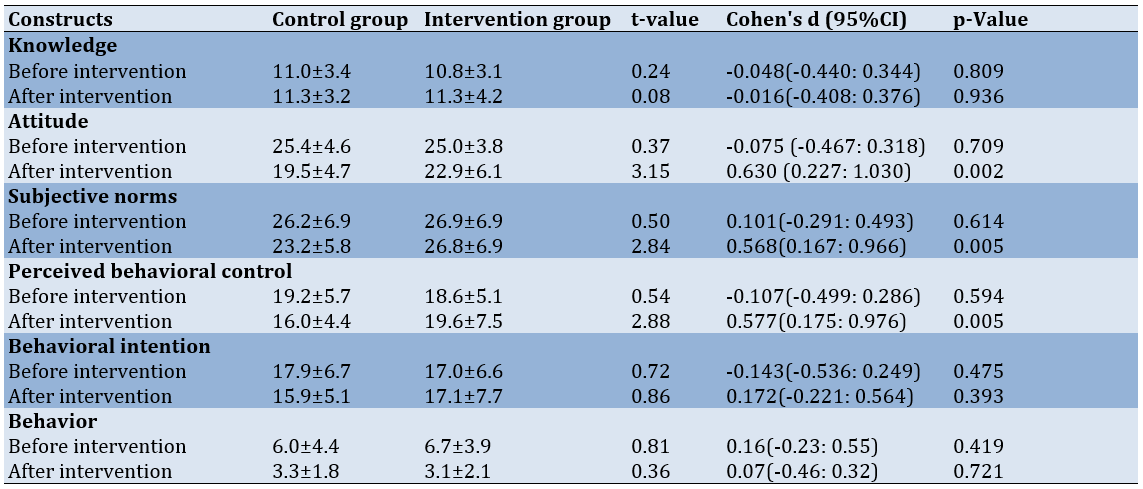

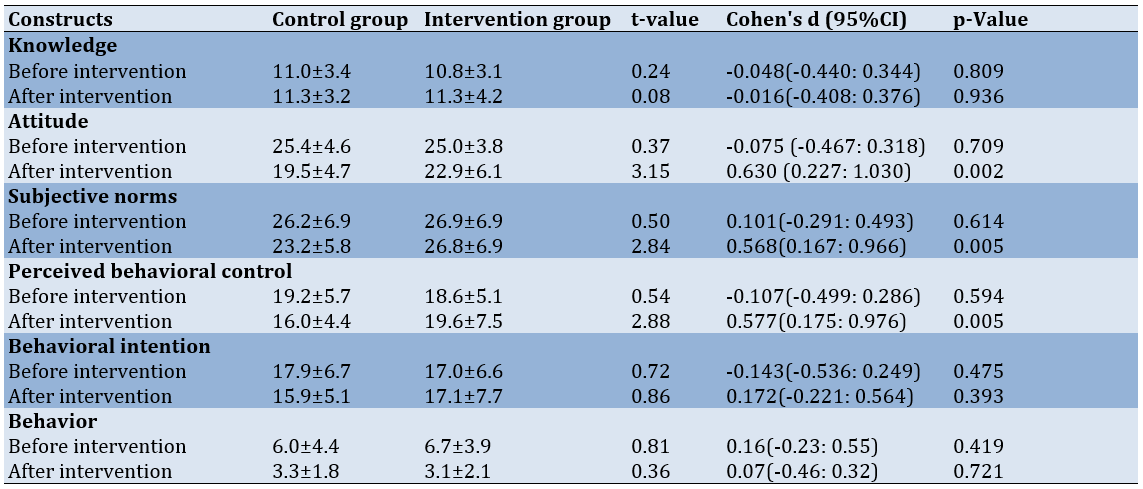

Before the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences in the mean scores for the constructs of knowledge, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention, and behavior between the control and intervention groups. However, following the educational intervention, the mean scores for attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in the intervention group were significantly higher than those in the control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the mean scores of the measured constructs before and after the intervention in the intervention and control groups

Discussion

This study was conducted on 100 female high school students in Tehran to evaluate the impact of an educational intervention based on the TPB on fast food consumption. The demographic characteristics of the participants, including parents’ ages, occupations, and education, showed no significant differences between the control and intervention groups, consistent with findings from Barati et al. and Peyman et al. [1, 10].

The intervention did not significantly alter the students’ knowledge before and after the intervention. This aligns with studies by Vahdaninia et al. in Birjand and Sanaye et al. at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, indicating that educational programs have no significant impact on knowledge of healthy food consumption [19, 20]. However, according to Shabanian et al. and Shaikh-Ahmadi et al., there is a significant relationship between knowledge and healthy food consumption [9, 21]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the study location and socioeconomic status, as the current study was conducted in District 4 of Tehran, where the population’s knowledge, economic, and social status are relatively high. The pre-intervention knowledge score was already relatively high, leaving little room for significant improvement post-intervention.

In contrast, the attitude of the intervention group showed a significant improvement after the training compared to the control group. The TPB, as a cognitive model, evaluates how individuals respond to health-threatening factors, often leading to enhanced attitudes. A positive attitude can increase motivation and perseverance, ultimately improving performance [22]. These findings are consistent with those of Esmaeili Vardanjani et al. on the effect of nutrition education on knowledge, attitude, and performance regarding unhealthy food consumption among female elementary school students [23], and Rasouli et al. on the impact of combined health education programs on knowledge, attitude, and nutritional performance among female middle school students in Bojnord [24]. However, according to Peyman et al.'s study in Chenaran, a similar educational intervention causes no significant change in attitude [10].

The subjective norms of the intervention group also improved significantly compared to the control group post-intervention. Subjective norms, which reflect social expectations, play a crucial role in predicting behavioral intentions. If society expects individuals to adopt certain behaviors, they are more likely to do so [4]. This finding aligns with studies by Lavelle et al., focusing on youth peer leadership interventions to improve nutritional biomarkers, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes [25], and Jadgal et al., examining the effectiveness of nutrition education for elementary school children based on the TPB [26]. The increase in subjective norms can be attributed to the educational intervention and the use of TPB strategies in the classroom. Adolescents’ sensitivity to education and the appeal of the materials presented likely contributed to this outcome, as the program identified and reinforced positive norms regarding fast food consumption, leading to a reduction in its consumption.

Perceived behavioral control in the intervention group also improved significantly compared to the control group after the training. Asadpour et al. assessed predictors of fast food consumption among students at Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, finding that individuals with higher PBC are less likely to consume fast food, supporting the TPB framework [6]. Similarly, Dunn et al. reported that PBC predicts fast food consumption behavior [27], and Shaikh-Ahmadi et al., who examined the impact of education based on the TPB on the use of fast foods among female vocational school students, reporting that fast food consumption behavior is significantly associated with perceived behavioral control [9]. Seo et al. and Fila & Smith’s studies also highlighted that PBC significantly predicts healthy eating behavior [28, 29]. However, according to Ebadi et al., there is no significant correlation between PBC and fast food consumption [30].

Despite these positive outcomes, the educational program did not significantly improve behavioral intention or actual behavior in reducing fast food consumption. Carson assessed dietary behavior changes related to adolescent obesity in Texas, reporting that TPB-based interventions improve attitudes and PBC but do not lead to changes in intention or behavior [31]. Similarly, a systematic review by Hardeman et al. concluded that only half of TPB-based interventions lead to changes in intention, and two-thirds resulted in behavioral changes [32]. Khakpour et al. assessed the impact of combined education on nutritional behaviors among female students, reporting no significant difference in performance scores before and after the intervention [33], aligning with the current study. However, some studies have reported contrasting results [10, 22].

Given that unhealthy eating is a multifactorial problem influenced by various economic, cultural, and social factors, several interpretations can be offered for the lack of change in knowledge, intention, and behavior observed in the present study. Utilizing interactive and diverse educational techniques, such as multimedia presentations and hands-on activities, can enhance the impact. Participants might have been influenced by social desirability bias, reporting behaviors and intentions that align with perceived expectations rather than their actual actions and thoughts. To address this, it is suggested to use objective measures, such as food diaries or direct observations, to complement the data in future studies. Also, the duration of the intervention could also impact these factors. Sometimes, behavior change requires more time than initially anticipated. Adolescents may need repeated exposure to the intervention to internalize the messages and alter their behavior. This underscores the importance of sustained education in interventions, especially among adolescents. Therefore, it is recommended that future interventions be conducted over a longer period with extended follow-up. In addition, external factors can play a significant role. For instance, the preferred taste of fast foods, easy accessibility, and endorsements by celebrities and athletes can significantly tempt adolescents towards high consumption of fast food [34, 35]. Additionally, the influence of peers, family, and teachers is considerable, as adolescents are highly influenced by their peers. Thus, using peers to promote healthy eating habits within social groups is advised. Parental involvement can also be beneficial for reinforcing the intervention and supporting behavior change at home. Social support networks can play a critical role in maintaining behavior change. Also, regular monitoring and feedback can help students stay on track with their goals. Providing personal feedback and positive reinforcement can increase motivation and commitment to behavior change.

One of the limitations of the present study is the reliance on self-report tools, which can lead to bias and inaccuracies. Self-report measures are common in such research but can be influenced by recall biases. Limited school facilities restrict the use of multimedia tools in the educational process. Integrating multimedia tools that engage multiple senses can enhance the effectiveness of such interventions. Therefore, it is recommended that future educational programs incorporate diverse media to make the learning experience more engaging and impactful. Another limitation of this study is the short duration of the intervention due to insufficient time provided by schools for its implementation. Future studies could extend this time and consider longer follow-up periods to better understand the lasting effects of the interventions. The influence of external factors, such as family influence and advertisements, was not considered in this study. These elements can play a significant role in shaping students’ fast food consumption behaviors and should be addressed in future research.

It is suggested that incorporating TPB-based nutrition education into school curricula effectively shapes students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Schools can utilize these programs to promote healthier eating habits. Additionally, providing parents with educational materials on healthy eating supports the reduction of fast food consumption. Engaging families in the educational process reinforces school messages and creates a supportive home environment for behavior change. Policymakers can leverage the study’s findings to advocate for stricter regulations on fast food advertising targeting adolescents. By limiting exposure to persuasive marketing, policymakers can help reduce its influence on adolescents’ eating behaviors.

Based on the results of the present study, education grounded in the TPB proves effective in enhancing students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control regarding the reduction of fast food consumption. However, the intervention does not significantly impact students’ awareness, intention, or actual behavior in reducing fast food consumption. This suggests that while TPB-based education successfully influences cognitive and social factors, it falls short of translating these changes into actionable intentions or behaviors.

A key conclusion from this study is that students’ decisions to consume fast food, despite being aware of its negative health implications, are heavily influenced by the growing popularity and cultural normalization of fast food in Iran. Factors such as appealing taste, convenience, aggressive marketing, and social pressures play a significant role in shaping their dietary choices. This highlights the need for interventions that go beyond merely providing information about the harms of fast food. Instead, a more holistic approach is required—one that addresses the underlying social, cultural, and environmental factors driving fast food consumption.

To enhance the effectiveness of future interventions, it is recommended to integrate multimedia elements into the educational framework of the TPB. Multimedia tools, such as videos, interactive workshops, and digital platforms, engage students more effectively by appealing to multiple senses and making the educational content more relatable and impactful. Additionally, incorporating peer-led initiatives, role models, and community-based programs can further strengthen the influence of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control.

The findings of this study hold significant value for various stakeholders, including students, families, educational institutions, healthcare centers, and policymakers. Schools and universities can use these insights to design targeted educational programs that not only raise awareness but also address the psychological and social factors influencing fast food consumption. Healthcare centers and nutrition clinics can incorporate TPB-based strategies into their counseling and outreach efforts to promote healthier eating habits among adolescents.

Furthermore, organizations involved in public health and education can leverage these findings to develop comprehensive interventions aimed at preventing fast food consumption. By combining TPB-based education with multimedia tools and community engagement, these interventions create a more supportive environment for students to make healthier dietary choices.

In conclusion, while the TPB-based educational intervention demonstrates success in improving attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, its limited impact on awareness, intention, and behavior underscores the complexity of addressing fast food consumption. Future efforts should focus on multimedia-enhanced education and community-driven strategies to create a more sustainable impact on students’ dietary behaviors. These findings provide a valuable foundation for designing effective interventions to combat the growing trend of fast food consumption among adolescents in Iran and similar contexts.

Conclusion

TPB-based education is effective in improving attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks and appreciation are extended to the colleagues from the schools in District 4 of Tehran and to the support provided by the Deputy of Research and Technology at Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The study was conducted after obtaining the necessary permissions from the Research Council of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences and approval from the Ethics Committee of the university. Permissions were also obtained from the authorities of the District 4 Education Department in Tehran to enter the schools. All ethical considerations related to educational trial research, such as confidentiality principles and providing educational content to the control group after the study, were observed.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Bahmani A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (28%); Akhondzadeh E (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (28%); Hossainzadeh S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (28%); Gharibi F (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (16%)

Funding/Support: This work was funded by the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Nutrition plays a crucial role in the growth and enhancement of physical and mental health, particularly during adolescence. This sensitive and vital period has unique nutritional needs, and neglecting these needs can lead to chronic disorders and diseases, including stunted growth, malnutrition, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases [1]. Studies indicate that 70% of overweight adolescents are likely to become obese in adulthood [2], and Iranian society is expected to face an obesity epidemic in the coming decades [3, 4]. Adolescent girls require special attention due to the physiological changes associated with puberty, menstruation, and increased nutritional needs. They are more susceptible to iron deficiency anemia and malnutrition. Given that today’s adolescent girls are tomorrow’s mothers and the educators of future generations, they have a unique need for nutritional education [3].

In recent years, with changing lifestyles, the consumption of fast food among teenagers and young adults has increased significantly [5, 6]. These foods, which include items such as sandwiches, hamburgers, sausages, cold cuts, pizza, fried foods, and snacks, are often high in calories, trans fats, additives, and flavorings [7, 8]. Globally, about a quarter of the U.S. population uses fast-food restaurant services. In Iran, households spent 2% of their total expenses on fast food by the end of 2015 [9]. Unhealthy nutrition accounts for 35% of cancer-related deaths, underscoring the importance of correcting dietary patterns during childhood and adolescence [3].

Given the importance of students in the future of the country, as well as the cost-effectiveness and efficacy of health and nutrition education programs in schools, and considering that many eating habits and preferences of children and adolescents are formed in school and influenced by their classmates, appropriate educational interventions are necessary to reduce the consumption of fast foods [10]. Research demonstrates that nutrition education in schools significantly improves students’ knowledge and behavior [11]. For instance, nutrition education programs for female middle school students in Torbate-Heydariyeh and Birjand have shown positive effects on students’ nutritional knowledge and behavior [4, 10].

Health education models and theories provide a framework for understanding health behaviors and designing effective interventions. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) has been widely used to study attitudes and beliefs related to food choices [10, 12, 13]. This theory includes four key constructs, including behavioral intention, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Behavioral intention reflects an individual’s willingness to consume fast food. Attitude refers to the individual’s positive or negative evaluation of the behavior. Subjective norms encompass perceived social pressures, while perceived behavioral control indicates the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior [14]. The reason for choosing this theory compared to other psychological theories such as the health belief model (HBM), social cognitive theory (SCT), and transtheoretical model (TTM) is that the TPB, in addition to individual factors, pays special attention to social factors that play a key role in shaping behavior. The most important parameter of this theory, namely behavioral intention, influences the individual’s motivation to change behavior, which the aforementioned theories are not able to measure simultaneously [15-17].

However, the application of the TPB in the context of fast food consumption among female high school students in Iran has been poorly studied. This study addressed this gap by targeting a specific demographic at high risk for poor dietary habits and related health issues. By focusing on adolescent girls, this study provides novel insights into how educational interventions based on the TPB affect fast food consumption, contributing to improved health outcomes for this vulnerable group.

In light of the increasing tendency of adolescents and young adults to consume fast food and its adverse health consequences, this study aimed to investigate the effect of an educational program based on the TPB on reducing fast food consumption among female high school students.

Materials and Methods

This intervention study employed a pre-and post-intervention design and included 100 female high school students from two schools under the jurisdiction of the District 4 education authority in Tehran in the year 2024. One school was designated as the control group (50 students), and the other as the intervention group (50 students). From each school, three classes (one from each grade) were randomly selected. Based on the study’s objectives and similar research [9], a 95% confidence interval and 90% power were assumed to determine the sample size. If the change in the behavioral intention score from one person to another is around three points and its standard deviation is 0.3, then the sample size using Formula 1 was determined to be 38 individuals per group. Ultimately, 50 individuals per group were included in the study to increase accuracy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included students who were physically and mentally healthy and willing to participate. Exclusion criteria consisted of unwillingness to continue participating in the educational sessions or illness during the study period.

Data collection tool

The data collection tool in this study was a questionnaire whose validity and reliability had been assessed by relevant specialists. To ensure the face and content validity of the questionnaire, the adjusted scale was presented to five health education professors and two indices, the content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity index (CVI), were calculated [9]. The overall validity of the questionnaire was 0.84. The questionnaire included demographic information, awareness assessment, and various dimensions of the TPB. The reliability of the questionnaire, based on Cronbach’s alpha test, was 0.87. Additionally, the reliability of each construct, based on Cronbach’s alpha test, was 0.85 for knowledge, 0.74 for attitude, 0.84 for subjective norms, 0.70 for perceived behavioral control, 0.91 for behavioral intention, and 0.74 for behavior.

The questionnaire included 72 questions; eight questions on demographic characteristics, 18 questions assessing knowledge using a three-option scale (correct, don’t know, incorrect), nine questions on attitude, nine questions on subjective norms, six questions on perceived behavioral control, seven questions on behavioral intention, and 15 questions on fast food consumption.

The constructs of the TPB were measured using a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree).

Educational intervention

Before the educational intervention, the aforementioned questionnaire was distributed among the students in both the test and control groups. The education was based on the TPB and consisted of three fifty-minute training sessions for the students in the test group. Each session began with a five-minute question-and-answer segment, followed by a thirty-minute lecture and slide presentation on the definition of fast food, its harms and disadvantages, and its ingredients and components. The sessions concluded with a fifteen-minute question-and-answer segment. To supplement the education, the project executor prepared and distributed brochures on fast food consumption and its side effects among the participants. The source used for education and the preparation of educational materials, such as brochures and posters, was Dr. Mohammad Daryaei’s book, “Fast Foods (Toxic Foods) and Unpleasant Beverages,” a specialist in biological sciences and medicinal plants [18]. After providing the necessary education and concluding the classes, the questionnaire was redistributed and completed by the students in both the test and control groups.

Data analysis

Finally, the collected data were analyzed using SPSS 22 software. Descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequency, mean, standard deviation, and range, as well as analytical statistics, including the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check for normal data distribution, the independent t-test (Mann-Whitney U test) for comparing quantitative parameters between the intervention and control groups, and the Chi-square test for comparing nominal parameters between the two groups, were utilized.

Findings

The ages of all participating students ranged from 14 to 16 years. The average age of the students’ mothers was 41.9±4.4 years in the control group and 40.5±4.5 years in the intervention group. The average age of the students’ fathers was 45.5±7.9 years in the control group and 45.0±3.9 years in the intervention group. According to the independent t-test, there was no statistically significant difference in age between the intervention and control groups (p=0.122 for fathers’ age, p = 0.667 for mothers’ age). Additionally, no statistically significant differences were observed in other demographic parameters, such as parental education, occupation, or the students’ field of study, between the two groups. This indicates that the groups were homogeneous at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1. The control and intervention groups' absolute and relative frequency distribution of demographic parameters

Before the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences in the mean scores for the constructs of knowledge, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention, and behavior between the control and intervention groups. However, following the educational intervention, the mean scores for attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in the intervention group were significantly higher than those in the control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the mean scores of the measured constructs before and after the intervention in the intervention and control groups

Discussion

This study was conducted on 100 female high school students in Tehran to evaluate the impact of an educational intervention based on the TPB on fast food consumption. The demographic characteristics of the participants, including parents’ ages, occupations, and education, showed no significant differences between the control and intervention groups, consistent with findings from Barati et al. and Peyman et al. [1, 10].

The intervention did not significantly alter the students’ knowledge before and after the intervention. This aligns with studies by Vahdaninia et al. in Birjand and Sanaye et al. at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, indicating that educational programs have no significant impact on knowledge of healthy food consumption [19, 20]. However, according to Shabanian et al. and Shaikh-Ahmadi et al., there is a significant relationship between knowledge and healthy food consumption [9, 21]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the study location and socioeconomic status, as the current study was conducted in District 4 of Tehran, where the population’s knowledge, economic, and social status are relatively high. The pre-intervention knowledge score was already relatively high, leaving little room for significant improvement post-intervention.

In contrast, the attitude of the intervention group showed a significant improvement after the training compared to the control group. The TPB, as a cognitive model, evaluates how individuals respond to health-threatening factors, often leading to enhanced attitudes. A positive attitude can increase motivation and perseverance, ultimately improving performance [22]. These findings are consistent with those of Esmaeili Vardanjani et al. on the effect of nutrition education on knowledge, attitude, and performance regarding unhealthy food consumption among female elementary school students [23], and Rasouli et al. on the impact of combined health education programs on knowledge, attitude, and nutritional performance among female middle school students in Bojnord [24]. However, according to Peyman et al.'s study in Chenaran, a similar educational intervention causes no significant change in attitude [10].

The subjective norms of the intervention group also improved significantly compared to the control group post-intervention. Subjective norms, which reflect social expectations, play a crucial role in predicting behavioral intentions. If society expects individuals to adopt certain behaviors, they are more likely to do so [4]. This finding aligns with studies by Lavelle et al., focusing on youth peer leadership interventions to improve nutritional biomarkers, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes [25], and Jadgal et al., examining the effectiveness of nutrition education for elementary school children based on the TPB [26]. The increase in subjective norms can be attributed to the educational intervention and the use of TPB strategies in the classroom. Adolescents’ sensitivity to education and the appeal of the materials presented likely contributed to this outcome, as the program identified and reinforced positive norms regarding fast food consumption, leading to a reduction in its consumption.

Perceived behavioral control in the intervention group also improved significantly compared to the control group after the training. Asadpour et al. assessed predictors of fast food consumption among students at Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, finding that individuals with higher PBC are less likely to consume fast food, supporting the TPB framework [6]. Similarly, Dunn et al. reported that PBC predicts fast food consumption behavior [27], and Shaikh-Ahmadi et al., who examined the impact of education based on the TPB on the use of fast foods among female vocational school students, reporting that fast food consumption behavior is significantly associated with perceived behavioral control [9]. Seo et al. and Fila & Smith’s studies also highlighted that PBC significantly predicts healthy eating behavior [28, 29]. However, according to Ebadi et al., there is no significant correlation between PBC and fast food consumption [30].

Despite these positive outcomes, the educational program did not significantly improve behavioral intention or actual behavior in reducing fast food consumption. Carson assessed dietary behavior changes related to adolescent obesity in Texas, reporting that TPB-based interventions improve attitudes and PBC but do not lead to changes in intention or behavior [31]. Similarly, a systematic review by Hardeman et al. concluded that only half of TPB-based interventions lead to changes in intention, and two-thirds resulted in behavioral changes [32]. Khakpour et al. assessed the impact of combined education on nutritional behaviors among female students, reporting no significant difference in performance scores before and after the intervention [33], aligning with the current study. However, some studies have reported contrasting results [10, 22].

Given that unhealthy eating is a multifactorial problem influenced by various economic, cultural, and social factors, several interpretations can be offered for the lack of change in knowledge, intention, and behavior observed in the present study. Utilizing interactive and diverse educational techniques, such as multimedia presentations and hands-on activities, can enhance the impact. Participants might have been influenced by social desirability bias, reporting behaviors and intentions that align with perceived expectations rather than their actual actions and thoughts. To address this, it is suggested to use objective measures, such as food diaries or direct observations, to complement the data in future studies. Also, the duration of the intervention could also impact these factors. Sometimes, behavior change requires more time than initially anticipated. Adolescents may need repeated exposure to the intervention to internalize the messages and alter their behavior. This underscores the importance of sustained education in interventions, especially among adolescents. Therefore, it is recommended that future interventions be conducted over a longer period with extended follow-up. In addition, external factors can play a significant role. For instance, the preferred taste of fast foods, easy accessibility, and endorsements by celebrities and athletes can significantly tempt adolescents towards high consumption of fast food [34, 35]. Additionally, the influence of peers, family, and teachers is considerable, as adolescents are highly influenced by their peers. Thus, using peers to promote healthy eating habits within social groups is advised. Parental involvement can also be beneficial for reinforcing the intervention and supporting behavior change at home. Social support networks can play a critical role in maintaining behavior change. Also, regular monitoring and feedback can help students stay on track with their goals. Providing personal feedback and positive reinforcement can increase motivation and commitment to behavior change.

One of the limitations of the present study is the reliance on self-report tools, which can lead to bias and inaccuracies. Self-report measures are common in such research but can be influenced by recall biases. Limited school facilities restrict the use of multimedia tools in the educational process. Integrating multimedia tools that engage multiple senses can enhance the effectiveness of such interventions. Therefore, it is recommended that future educational programs incorporate diverse media to make the learning experience more engaging and impactful. Another limitation of this study is the short duration of the intervention due to insufficient time provided by schools for its implementation. Future studies could extend this time and consider longer follow-up periods to better understand the lasting effects of the interventions. The influence of external factors, such as family influence and advertisements, was not considered in this study. These elements can play a significant role in shaping students’ fast food consumption behaviors and should be addressed in future research.

It is suggested that incorporating TPB-based nutrition education into school curricula effectively shapes students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Schools can utilize these programs to promote healthier eating habits. Additionally, providing parents with educational materials on healthy eating supports the reduction of fast food consumption. Engaging families in the educational process reinforces school messages and creates a supportive home environment for behavior change. Policymakers can leverage the study’s findings to advocate for stricter regulations on fast food advertising targeting adolescents. By limiting exposure to persuasive marketing, policymakers can help reduce its influence on adolescents’ eating behaviors.

Based on the results of the present study, education grounded in the TPB proves effective in enhancing students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control regarding the reduction of fast food consumption. However, the intervention does not significantly impact students’ awareness, intention, or actual behavior in reducing fast food consumption. This suggests that while TPB-based education successfully influences cognitive and social factors, it falls short of translating these changes into actionable intentions or behaviors.

A key conclusion from this study is that students’ decisions to consume fast food, despite being aware of its negative health implications, are heavily influenced by the growing popularity and cultural normalization of fast food in Iran. Factors such as appealing taste, convenience, aggressive marketing, and social pressures play a significant role in shaping their dietary choices. This highlights the need for interventions that go beyond merely providing information about the harms of fast food. Instead, a more holistic approach is required—one that addresses the underlying social, cultural, and environmental factors driving fast food consumption.

To enhance the effectiveness of future interventions, it is recommended to integrate multimedia elements into the educational framework of the TPB. Multimedia tools, such as videos, interactive workshops, and digital platforms, engage students more effectively by appealing to multiple senses and making the educational content more relatable and impactful. Additionally, incorporating peer-led initiatives, role models, and community-based programs can further strengthen the influence of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control.

The findings of this study hold significant value for various stakeholders, including students, families, educational institutions, healthcare centers, and policymakers. Schools and universities can use these insights to design targeted educational programs that not only raise awareness but also address the psychological and social factors influencing fast food consumption. Healthcare centers and nutrition clinics can incorporate TPB-based strategies into their counseling and outreach efforts to promote healthier eating habits among adolescents.

Furthermore, organizations involved in public health and education can leverage these findings to develop comprehensive interventions aimed at preventing fast food consumption. By combining TPB-based education with multimedia tools and community engagement, these interventions create a more supportive environment for students to make healthier dietary choices.

In conclusion, while the TPB-based educational intervention demonstrates success in improving attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, its limited impact on awareness, intention, and behavior underscores the complexity of addressing fast food consumption. Future efforts should focus on multimedia-enhanced education and community-driven strategies to create a more sustainable impact on students’ dietary behaviors. These findings provide a valuable foundation for designing effective interventions to combat the growing trend of fast food consumption among adolescents in Iran and similar contexts.

Conclusion

TPB-based education is effective in improving attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks and appreciation are extended to the colleagues from the schools in District 4 of Tehran and to the support provided by the Deputy of Research and Technology at Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The study was conducted after obtaining the necessary permissions from the Research Council of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences and approval from the Ethics Committee of the university. Permissions were also obtained from the authorities of the District 4 Education Department in Tehran to enter the schools. All ethical considerations related to educational trial research, such as confidentiality principles and providing educational content to the control group after the study, were observed.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Bahmani A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (28%); Akhondzadeh E (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (28%); Hossainzadeh S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (28%); Gharibi F (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (16%)

Funding/Support: This work was funded by the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2025/01/8 | Accepted: 2025/02/16 | Published: 2025/02/18

Received: 2025/01/8 | Accepted: 2025/02/16 | Published: 2025/02/18

References

1. Barati F, Shamsi M, Khorsandi M, Ranjbaran M. Measuring the constructs of planned behavior theory regarding the behaviors preventing of junk food consumption in elementary students in Arak in 2015. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2016;18(11):10-8. [Persian] [Link]

2. Vafaee-Najar A, Sepahi Baghan M, Ebrahimipour H, Miri MR, Esmaily H, Lael-Monfared E, et al. Effect of nutrition education during puberty on nutritional knowledge and behavior of secondary School female students in Birjand in 2012. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2014;21(2):211-8. [Persian] [Link]

3. Alimoradi F, Jandaghi P, Khodabakhshi A, Javadi M, Moghadam SAHZ. Breakfast and fast food eating behavior in relation to socio-demographic differences among school adolescents in Sanandaj Province, Iran. Electron Physician. 2017;9(6):4510-5. [Link] [DOI:10.19082/4510]

4. Mirkarimi K, Bagheri D, Honarvar M, Kabir M, Ozouni-Davaji R, Eri M. Effective factors on fast food consumption among high-school students based on planned behavior theory. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2016;18(4):88-93. [Persian] [Link]

5. Fazelpour S, Baghianimoghadam M, Nagharzadeh A, Fallahzadeh H, Shamsi F, Khabiri F. Assessment of fast food concumption among people of Yazd city. TOLOO-E-BEHDASHT. 2011;10(2):25-34. [Persian] [Link]

6. Asadpour M, Mahbobi Rad M, Mobini Lotfabad M, Nasirzadeh M, Abdolkarimi M, Shahabinejad E. Predictors of fast-food consumption in students of Rafsanjan university of medical sciences based on the theory of planned behavior. J Prev Med. 2023;10(2):186-97. [Persian] [Link]

7. Bîlbîie A, Druică E, Dumitrescu R, Aducovschi D, Sakizlian R, Sakizlian M. Determinants of fast-food consumption in Romania: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Foods. 2021;10(8):1877. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/foods10081877]

8. Singh UK, Gautam N, Bhandari TR, Sapkota N. Educational intervention of intention change for consumption of junk food among school adolescents in Birgunj metropolitan city, Nepal, based on theory of planned behaviors. J Nutr Metab. 2020;2020:7932324. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2020/7932324]

9. Shaikh-Ahmadi SS, Bahmani A, Teymouri P, Gheibi F. Effect of education based on the theory of planned behavior on the use of fast foods in students of girls' vocational schools. J Educ Community Health. 2019;6(3):153-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jech.6.3.153]

10. Peyman N, Khorasani EC, Moghzi M. The impact of education on the basis of the theory of planned behavior on junk food consumption in high school in Chenaran. Razi J Med Sci. 2016;23(8):62-72. [Persian] [Link]

11. Alizadeh SH, Keshavarz M, Jafari A, Ramezani H, Sayadi A. Effects of nutritional education on knowledge and behaviors of Primary Students in Torbat-e-Heydariyeh. J Torbat Heydariyeh Univ Med Sci. 2013;1(1):44-51. [Persian] [Link]

12. Sogari G, Pucci T, Caputo V, Van Loo EJ. The theory of planned behaviour and healthy diet: Examining the mediating effect of traditional food. Food Qual Prefer. 2023;104:104709. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104709]

13. Jahangiri Z, Shamsi M, Khorsandi M, Moradzade R. The effect of education based on theory of planned behavior in promoting nutrition-related behaviors to prevent anemia in pregnant women. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2020;23(6):872-87. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/jams.23.6.135.37]

14. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Link]

15. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390]

16. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Link]

17. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179-211. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T]

18. Daryaei M. Fast foods (poisonous foods) and horrible drinks. Tehran: SAFIRARDEHAL; 2015. [Persian] [Link]

19. Sanaye S, Azargashb E, Derisi MM, Zamani A, Keyvanfar A. Assessing knowledge and attitudes toward fast foods among students of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in 1394. J Med Counc Iran. 2016;34(1). [Persian] [Link]

20. Vahdaninia V, Vahdaninia Z, Baghernezhad Hesary F. The effect of education on fast food consumption behavior in primary school students in Birjand. Mil Caring Sci J. 2020;7(2):149-58. [Persian] [Link]

21. Shabanian Kh, Ghofranipour F, Shahbazi H, Tavousi M. Effect of health education on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of fast food consumption among primary students in Tehran. Health Educ Health Promot. 2018;6(2):47-52. [Link] [DOI:10.29252/HEHP.6.2.47]

22. Rakhshani T, Asadi S, Kashfi SM, Sohrabi Z, Kamyab A, Jeihooni AK. The effect of education based on the theory of planned behavior to prevent the consumption of fast food in a population of teenagers. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43(1):147. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s41043-024-00640-1]

23. Esmaeili Vardanjani A, Reisi M, Javadzade H, Gharli Pour Z, Tavassoli E. The effect of nutrition education on knowledge, attitude, and performance about junk food consumption among students of female primary schools. J Educ Health Promot. 2015;4(1):53. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.162349]

24. Rasouli A, Tavafian SS, Amin SF. Effects of integrated health education program on knowledge, attitude and practical approaches of female students in Bojnurd secondary schools towards dietary regimen. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2010;2(2-3):73-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jnkums.2.2.3.73]

25. Lavelle MA, Knopp M, Gunther CW, Hopkins LC. Youth and peer mentor led interventions to improve biometric-, nutrition, physical activity, and psychosocial-related outcomes in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(12):2658. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu15122658]

26. Jadgal MS, Sayedrajabizadeh S, Sadeghi S, Nakhaei-Moghaddam T. Effectiveness of nutrition education for elementary school children based on the theory of planned behavior. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2020;8(1):308-17. [Link] [DOI:10.12944/CRNFSJ.8.1.29]

27. Dunn KI, Mohr P, Wilson CJ, Wittert GA. Determinants of fast-food consumption. An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2011;57(2):349-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2011.06.004]

28. Fila SA, Smith C. Applying the theory of planned behavior to healthy eating behaviors in urban Native American youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:11. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1479-5868-3-11]

29. Seo HS, Lee SK, Nam S. Factors influencing fast food consumption behaviors of middle-school students in Seoul: An application of theory of planned behaviors. Nutr Res Pract. 2011;5(2):169-78. [Link] [DOI:10.4162/nrp.2011.5.2.169]

30. Ebadi L, Rakhshanderou S, Ghaffari M. Determinants of fast food consumption among students of Tehran: Application of planned behavior theory. J Pediatr Perspect. 2018;6(10):8307-16. [Link]

31. Carson DE. Changes in obesity-related food behavior: A nutrition education intervention to change attitudes and other factors associated with food-related intentions in adolescents: An application of the theory of planned behavior. College Station: Texas A&M University; 2010. [Link]

32. Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston D, Bonetti D, Wareham N, Kinmonth AL. Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: A systematic review. Psychol Health. 2002;17(2):123-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08870440290013644a]

33. Khakpour S, Tavafian S, Niknami S, Mohammadi S. Effect of combined education on promoting nutritional behaviors of female students. J Educ Community Health. 2016;3(2):41-6. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech-03026]

34. Shah T, Purohit G, Nair SP, Patel B, Rawal Y, Shah R. Assessment of obesity, overweight and its association with the fast food consumption in medical students. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(5):CC05-7. [Link] [DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2014/7908.4351]

35. Joseph N, Nelliyanil M, Rai S, YP RB, Kotian SM, Ghosh T, et al. Fast food consumption pattern and its association with overweight among high school boys in Mangalore city of southern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(5):LC13-7. [Link] [DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2015/13103.5969]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |