Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 71-79 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ashoobi M, Bakhshi F, Saeidi Saedi H, Shakiba M, Mahdavi-Roshan M, Marhaba M et al . Health-Promoting Behaviors among Iranian Breast Cancer Patients Using the Self-Regulation Model. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :71-79

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78736-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78736-en.html

M.T. Ashoobi1, F. Bakhshi *2, H. Saeidi Saedi3, M. Shakiba4, M. Mahdavi-Roshan5, M. Marhaba6, N. Nikpey7

1- “Department of Surgery, School of Medicine” and “Razi Hospital”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- “Research Center of Health and Environment” and “Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Department of Radiation Oncology, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5- “Cardiovascular Diseases Research Center” and “Heshmat Hospital, School of Medicine”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

6- Research Center of Health and Environment, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

7- “Student Research Committee” and “Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Public Health and Safety”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Research Center of Health and Environment” and “Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Department of Radiation Oncology, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5- “Cardiovascular Diseases Research Center” and “Heshmat Hospital, School of Medicine”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

6- Research Center of Health and Environment, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

7- “Student Research Committee” and “Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Public Health and Safety”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 639 kb]

(320 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (562 Views)

Full-Text: (47 Views)

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) remains a significant public health concern globally [1], with rising incidence rates and varying survival outcomes influenced by numerous factors, including healthcare systems and treatment accessibility [2]. Among the types of cancer, BC is a common, malignant, and progressive disease that affects various aspects of a person’s life [3]. According to a report from the World Health Organization, 2.3 million women had BC, and 685 thousand died from it in 2020 [4]. In Iran, recent statistics indicate a concerning trend; the average age of women diagnosed with BC has decreased by approximately ten years, highlighting the urgent need for effective health promotion strategies tailored to this demographic [5]. Understanding the implications of these survival rates not only sheds light on the effectiveness of the Iranian healthcare system but also underscores the necessity for improved treatment options and preventive measures [6]. Health-promoting behaviors play a crucial role in the prevention and management of BC [7]. Decision-making in patients with BC has largely focused on treatment options, with less attention paid to health-promoting behaviors such as a healthy diet, regular exercise and physical activity, vitamin intake, and timely screening [8]. The growing trend of chronic diseases and the importance of improving the quality of life for this group of patients, along with increasing their lifespan, have made the need for health promotion interventions and a healthy lifestyle more prominent than ever [9]. For more effective training and interventions, it is a priority to identify the factors that predict behaviors in order to design appropriate and effective training for these individuals based on a suitable model [10].

Health-promoting behaviors represent a multidimensional model of voluntary and cognitive actions that lead to maintaining and enhancing health, self-actualization, and success [11]. Meanwhile, the task of health education—both in understanding health behaviors and in transferring knowledge related to health behavior—is to create an effective strategy for increasing the level of healthy behavior. This defines the scope of practices by using models and theories as frameworks for shaping rules in the field of health [12] and helps identify individual and environmental characteristics that influence human behavior [13]. Since one of the goals of health professionals is to assist patients in responding appropriately to risk factors for diseases [14], it is essential to establish a clear connection between these behaviors and their impact on BC outcomes [15]. This connection will provide a foundation for exploring the self-regulation model, which serves as a framework for understanding how individuals can manage their health proactively [16].

Self-regulation is the act of modifying behavior based on self-observations. Accordingly, the self-regulation model was proposed in 1980 by Leventhal et al., and it includes three components of interpretation, adaptation, and evaluation [15, 17]. The interpretation stage is related to the recognition of health-threatening factors, which enables the individual to address their potential disease problem through the perception of disease symptoms and their social consequences [18].

The adaptation or action plan stage is characterized by efforts to control fear or other emotions related to the disease or threat. In the evaluation stage, individuals compare their level and status of performance with the degree of achievement of desired standards to identify discrepancies or differences along a spectrum of desirable to undesirable behaviors and determine what intervention is needed [19]. Self-regulation involves personal control over the monitoring of behaviors, thoughts, and emotions through a continuous cycle of review to manage an identified or emerging problem, to produce a desired outcome or avoid an undesirable outcome [20]. Therefore, the self-regulation model can be used to explain how beliefs or knowledge about a disease may interfere with the recognition and management of its symptoms, considering the individual as an active problem-solving agent in the management of their disease [21]. This model specifically includes the self-system, cognitive and emotional experiences, and health-promoting behaviors. The self-system comprises self and social environmental factors that are essential for understanding health threats. It includes demographic factors (age, socioeconomic factors, etc.), biological factors (passive treatment), and cultural and regional factors (such as rural areas). When the self-system is presented with a stimulus like BC, a cognitive and emotional experience of the health threat is formed in the individual. Cognitive experiences may include salient features of the disease, such as, “What is the disease?” or “What is the impact of a health-promoting behavior?” [15, 22]

In justifying the role of the self-regulation model in the health-promoting behaviors of BC patients, it can be stated that the psychosocial factors of the model, such as distress, perceived risk, and perceived treatment effectiveness, are integrated into the interpretation stage. This integration allows patients to gain a correct understanding of their disease and to follow the recommendations and training provided to manage their condition. This accurate understanding of their health status can reduce mortality, complications, and adverse outcomes of the disease while improving quality of life. Subsequently, in the evaluation stage, patients address the objective aspects of the disease along with the strategies they have selected and planned to achieve the health-related goals resulting from the disease understanding stage. Finally, in the evaluation stage, by comparing their own performance and behavior with the desired level, they can determine which types of health-oriented behaviors to select and implement [20, 22]. Since there is a significant relationship between perceived treatment effectiveness and patients’ cultural status, which affects their healthcare behaviors and attitudes [23], this study aimed to determine the health-promoting behaviors among BC patients in the North of Iran, focusing on how social, cultural, and economic factors influence these behaviors. By examining this specific population, we can identify unique characteristics that may affect their health management strategies, such as regional healthcare access and cultural beliefs.

Furthermore, this research aimed to engage with the existing literature on health-promoting behaviors in BC patients, identifying a profile of patients’ lifestyles. By doing so, we hope to reinforce the significance of our research within the broader context of health promotion. The findings of this study could inform future interventions and health policies aimed at enhancing health-promoting behaviors among BC patients, ultimately contributing to improved health outcomes.

Instrument and Methods

Study type, setting, and participants

This cross-sectional analytical study aimed to identify predictors of health-promoting behaviors based on the self-regulation model among BC patients registered in the hospital/clinical breast cancer registry program at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, conducted in 2021.

The sample size was determined using Kline’s formula [24], which suggested a requirement of five observations per item across 47 items, with an additional 10% accounted for attrition, resulting in a calculated sample size of 260 participants.

The national clinical breast cancer registry program in Iran, established in 2018, is a collaborative effort involving 12 provinces and 15 hospitals. This registry collects over 160 data items, including patient demographics, diagnostic factors, treatment modalities, and follow-up information for BC patients admitted for initial treatment. By the time of this study, 497 patients had been registered in the clinical cancer registry program of Guilan province. Participants were selected using a simple random sampling method based on the existing sampling framework from the hospital BC registration system database. Random numbers were generated using the Excel program and assigned to the corresponding patient file numbers.

Inclusion criteria included a newly confirmed diagnosis of BC, registration in the hospital BC registry program at treatment units affiliated with Guilan University of Medical Sciences (specifically Razi Hospital and Pursina Hospital), and being in either the active or inactive treatment stage (completion of treatment). Patients who did not respond to the questionnaire items were excluded, as were those unwilling to participate and individuals with metastasis or recurrence.

Procedure

Following approval from the Ethics Committee, registered patients were offered a complimentary consultation with an oncology specialist. On the day of the clinic visit, the researcher introduced herself, obtained informed consent, ensured confidentiality, and explained the study’s purpose. The questionnaire was then administered to participants, with the researcher conducting interviews with illiterate patients. The second part of the questionnaire, concerning disease status, was completed by the researcher based on the patient’s medical records and guidance from the attending physician. Data collection spanned five months, from October 7, 2020, to March 10, 2021.

Questionnaires

Data were collected using a questionnaire divided into four sections. The first section gathered demographic information, including age, body mass index (BMI), education level, employment status, marital status, family income, family history of disease, and participants’ self-assessment of their health status, rated from poor to excellent. The second section focused on health-promoting behaviors, which were assessed using a scale that measured various dimensions of health-related activities, including physical activity, nutrition, vitamin consumption, and mammography.

Physical activity was measured using the standard International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [25]. This questionnaire was validated in a study conducted across 12 countries and has demonstrated strong reliability, with a test-retest Spearman correlation of approximately 0.8 [26]. Nutrition was assessed using questions related to healthy eating from the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLP II) Questionnaire [27, 28]. Vitamin consumption was evaluated using three questions, and mammography was determined by two questions. The reliability of these two sections of the questionnaire was assessed using test-retest reliability on 20 subjects, yielding a correlation coefficient of 0.79 for vitamin consumption and 0.97 for mammography.

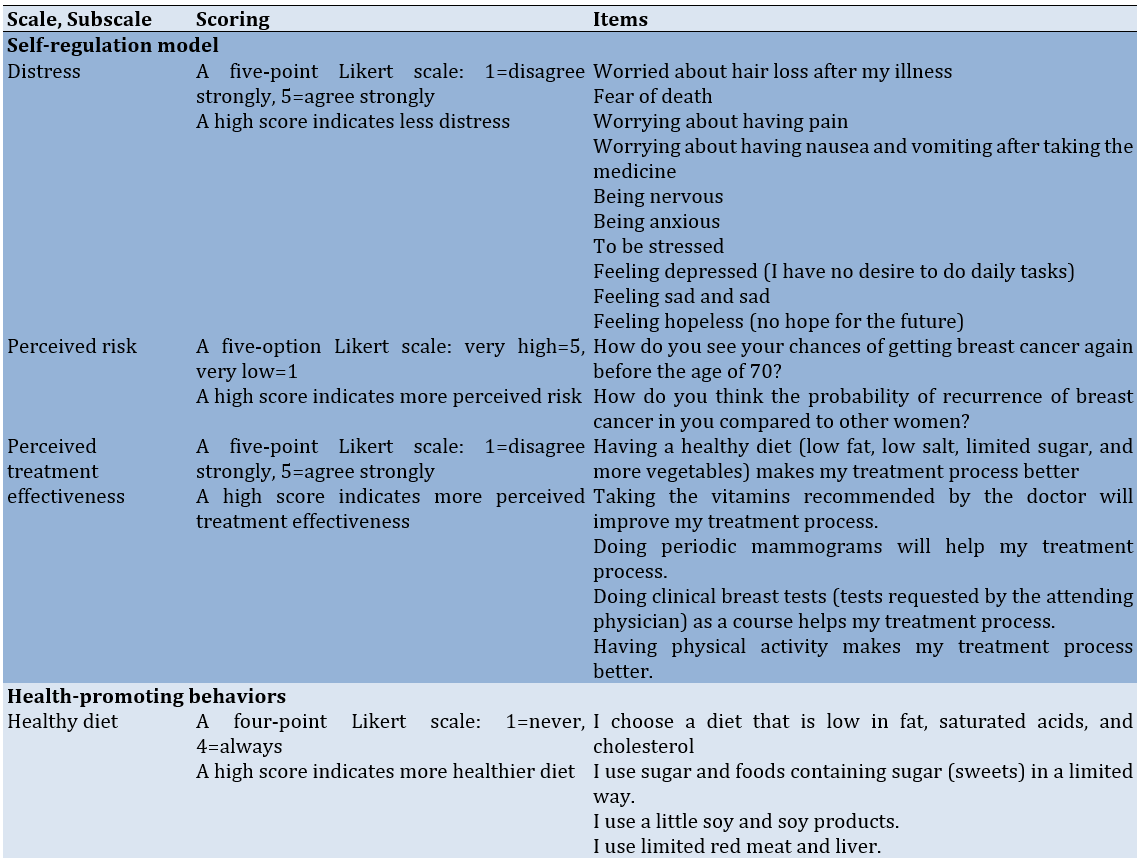

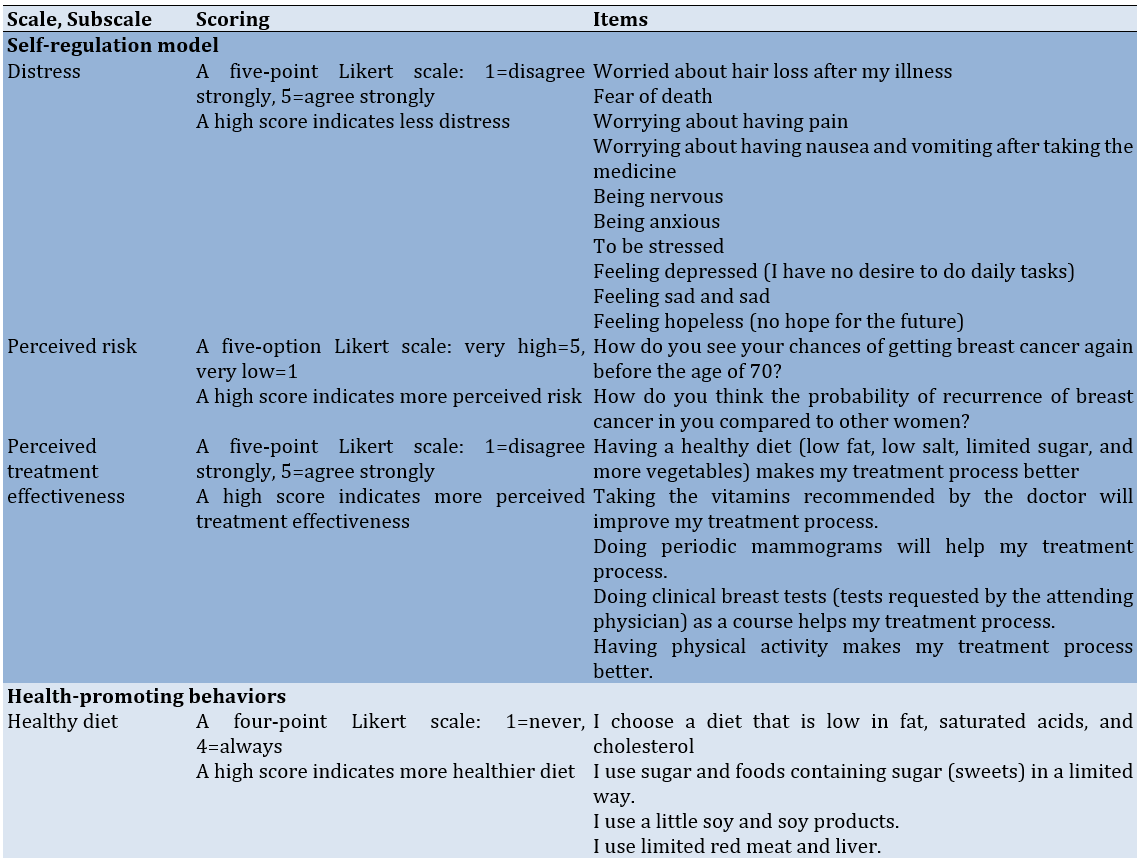

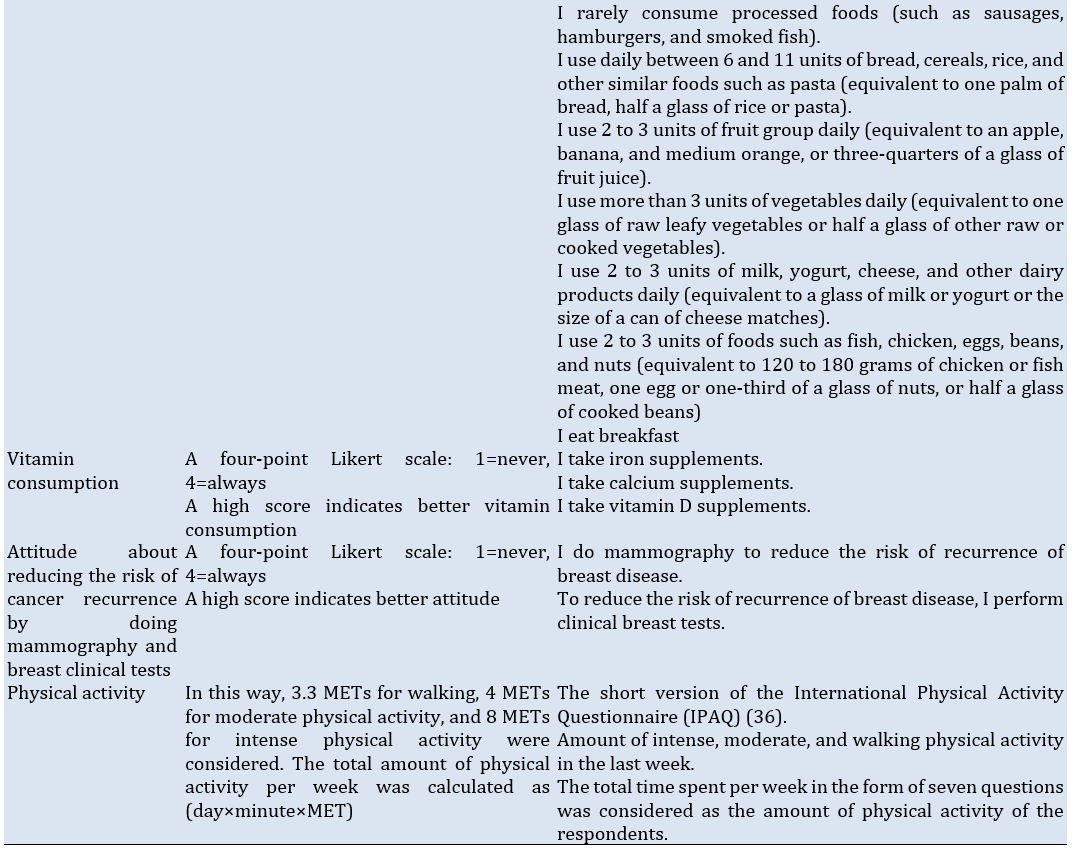

The third section evaluated the participants’ psychological factors related to self-regulation skills. It included questions concerning the psychosocial factors of the self-regulation model, which the research team prepared based on Kelly et al.’s study [22], and results from library studies, including anxiety and depression levels, perceived risk, and perceived treatment effectiveness (Table 1). According to the panel of experts, the content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were 0.8 and 0.88 for distress, 0.7 and 1 for perceived risk, and 0.88 and 0.98 for perceived treatment effectiveness, respectively. The corresponding Cronbach’s alpha values for distress, perceived risk, and perceived treatment effectiveness were 0.92, 0.79, and 0.89, respectively.

Finally, the fourth section collected information on the participants’ disease-related factors, such as the stage of cancer, treatment modalities, and duration since diagnosis.

Table 1. The subscales, items, scores, and psychometric properties of the scale

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics. The correlation between parameters was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. To identify predictors of health-promoting behaviors, a multivariate linear regression analysis was performed using the backward elimination method. This approach allowed for the adjustment of confounding parameters and the identification of significant predictors of health-promoting behaviors among the participants. The significance level was set at p<0.05 for all analyses.

Findings

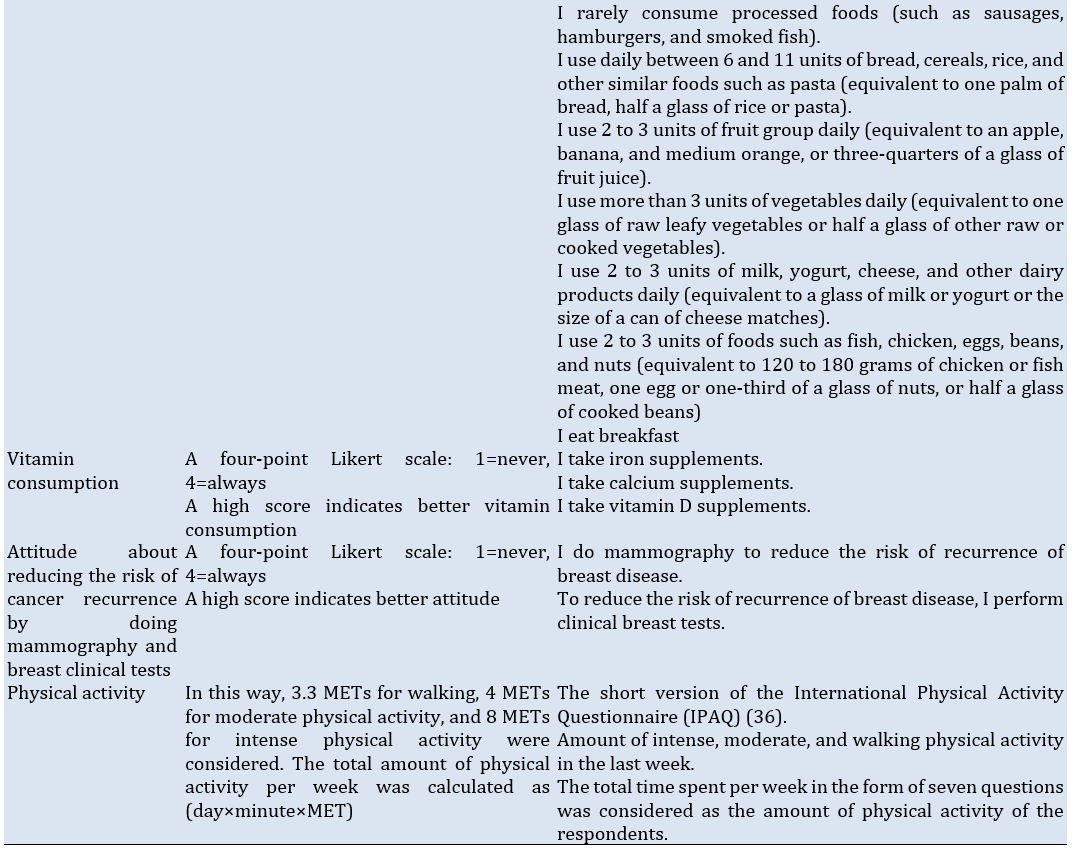

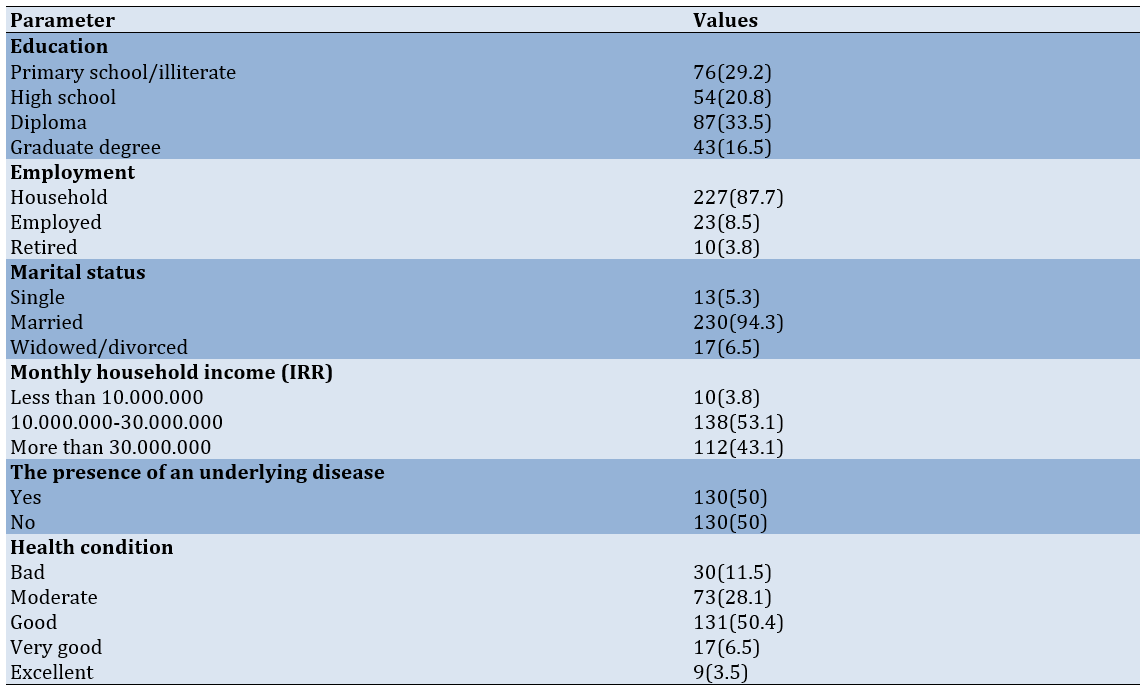

A total of 260 patients participated in this study, with a mean age of 52.6±10.6 years. Over 80% of the participants had completed diploma or sub-diploma education, and 87.7% were housewives. Approximately 94% of the patients were married, and the majority reported a family income ranging from 10 to 30 million IRR. Notably, 50% of the subjects had an underlying health condition. Also, the BMI of participants was found to be28.00±3.58kg/m2 (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Frequency of background characteristics of the participants (n=260)

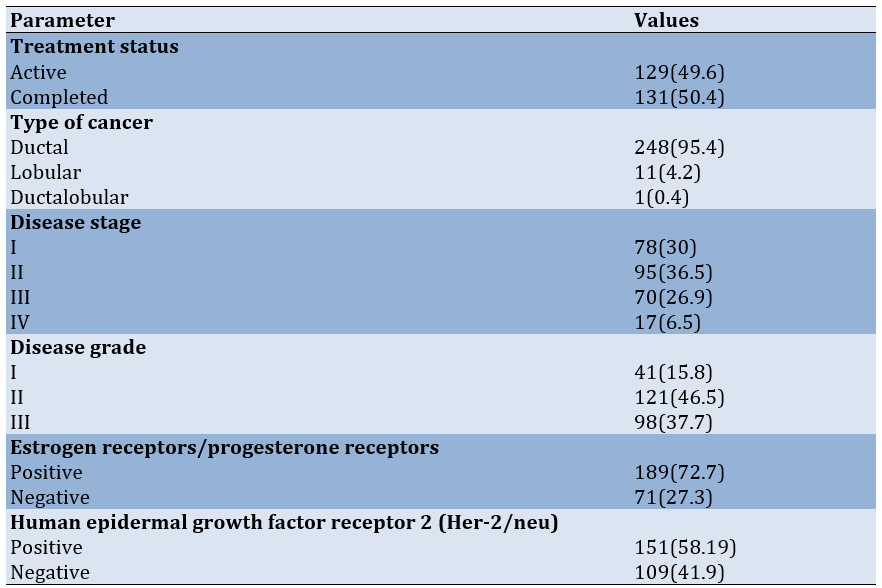

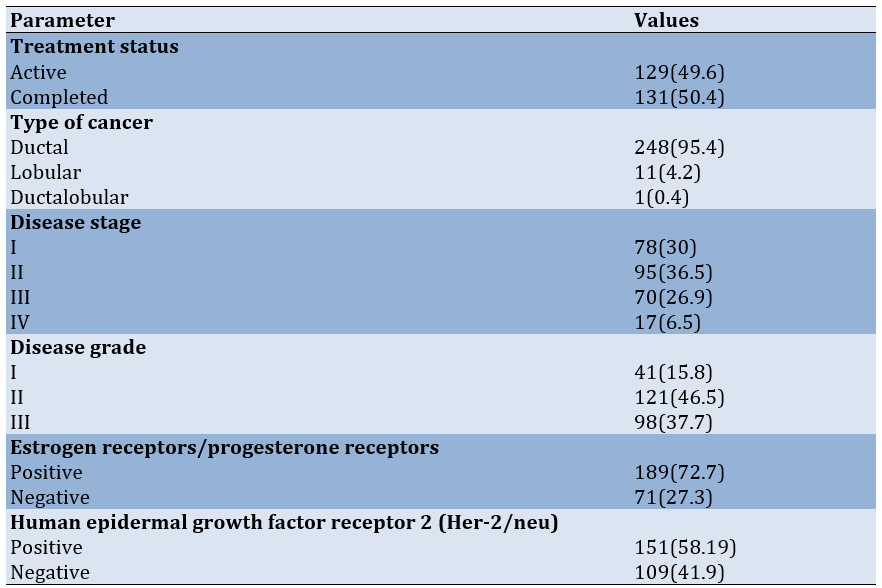

Table 3. Frequency of clinical characteristics of the participants (n=260)

The most prevalent cancer type among participants was ductal carcinoma (p=0.4), while stage 2 cancer was the most common disease stage (p=0.27). More than 70% of patients tested positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors (p=0.88).

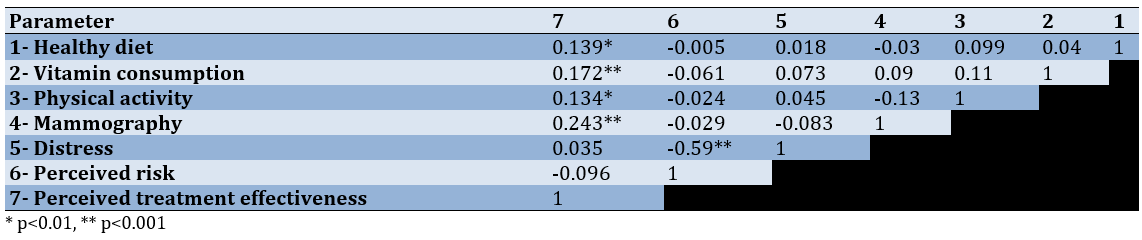

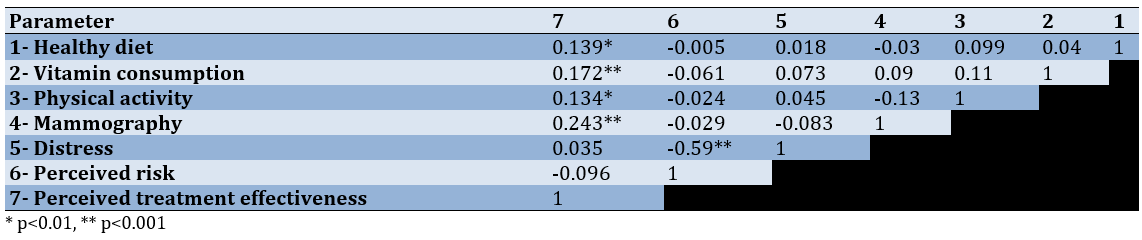

Significant positive correlations were found between perceived treatment effectiveness and a healthy diet (r=0.14, p<0.01), vitamin consumption (r=0.17, p<0.001), physical activity (r=0.13, p<0.01), and mammography (r=0.24, p<0.001). An inverse correlation was observed between distress and perceived risk (r=-0.59, p<0.001; Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation coefficients between the constructs of the self-regulation model and dimensions of health-promoting behaviors

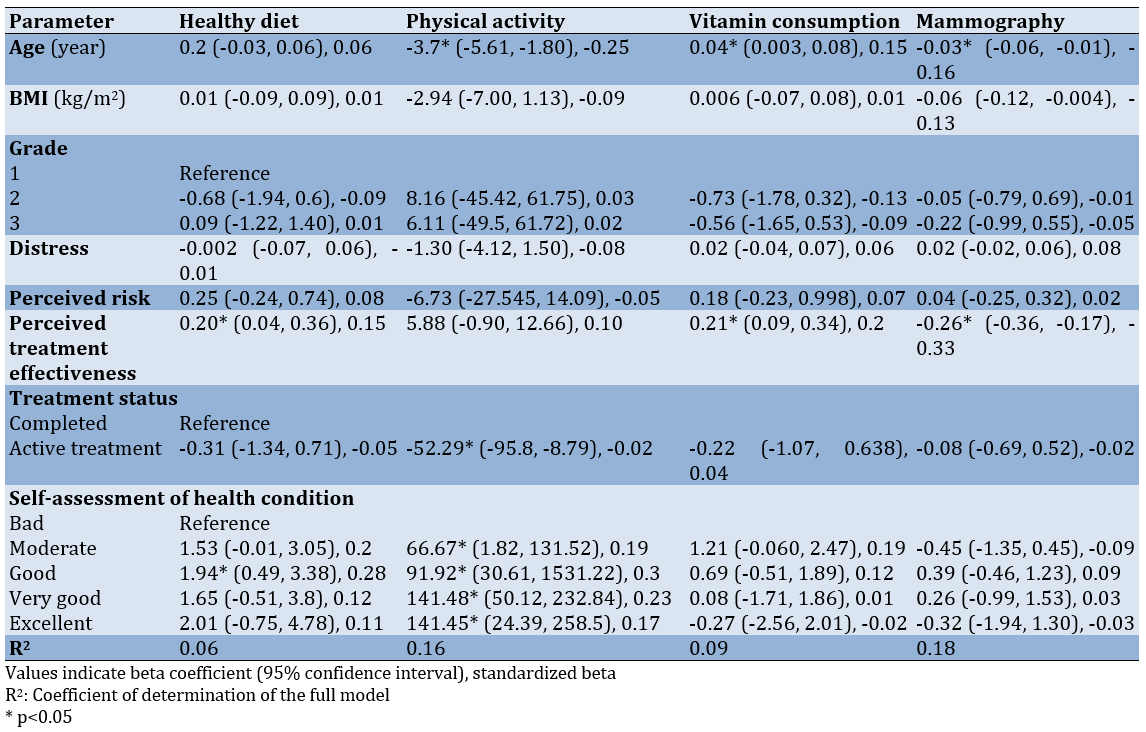

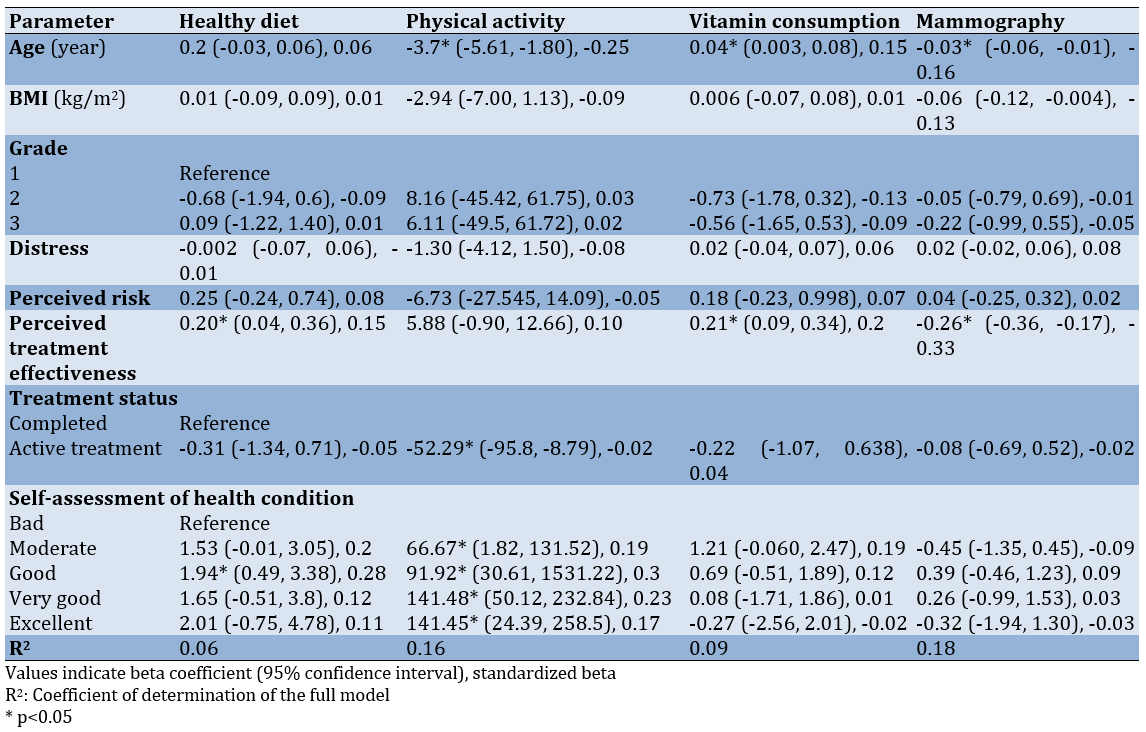

Linear regression analysis revealed a significant association between perceived treatment effectiveness and adherence to healthy behaviors, including diet, vitamin consumption, and mammography. Overall, higher perceived treatment effectiveness correlated with increased engagement in health-promoting behaviors (Table 5).

Table 5. Predictors of various dimensions of health-promoting behaviors using linear regression model

Age was identified as a significant independent factor influencing health-promoting behaviors, particularly physical activity, vitamin consumption, and mammography. Specifically, increasing age was associated with a significant decrease in physical activity (B=-3.7, p<0.001) and mammography scores (B=-0.03, p=0.013), while it correlated with an increase in vitamin consumption (B=0.04, p=0.031).

Furthermore, treatment status emerged as an independent predictor of physical activity, with treated individuals reporting lower average physical activity scores compared to those who had completed treatment (B=-52.29, p=0.02). A significant dose-response relationship was also noted, indicating that a better assessment of health condition was associated with higher levels of physical activity (p<0.05).

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the predictors of health-promoting behaviors in breast cancer patients in northern Iran, using the self-regulation model. BC remains the most common cancer among women worldwide and is the leading cause of cancer-related death in 11 regions globally [29]. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle not only reduces the risk of BC but also enhances recovery and survival, particularly in postmenopausal women [30, 31].

Patients who had completed treatment reported significantly higher levels of distress than those undergoing active treatment. This is consistent with Thakur et al.'s study in North India, finding heightened distress and poor body image in the early months after completing treatment [32]. The long-term decline in distress aligns with the findings of Sajjadyan et al., noting that BC patients adapt over time, utilizing problem-solving strategies and spirituality to cope [33]. The fear of disease recurrence can exacerbate distress, particularly in the post-treatment phase [34]. Corkum et al. also observed that higher distress scores are associated with reduced rates of immediate breast reconstruction post-treatment [35], while Westbrook et al. noted that distress peaks at symptom recurrence and is lowest during the first course of treatment [36]. These findings emphasize the need for psychological support even after treatment concludes, with palliative care planning playing a crucial role in addressing distress.

In terms of perceived risk, patients undergoing active treatment had significantly higher scores than those who had completed treatment. This observation aligns with Attari et al.’s findings, showing that higher perceived risk correlates with shorter treatment delays [37]. According to Leventhal’s self-regulation model, emotional responses to illness influence individuals’ coping strategies. Our results suggest that at the beginning of diagnosis and treatment, perceived risk is high, driving patients to initiate treatment. As treatment progresses and uncertainty diminishes, perceived risk decreases. Interestingly, we also observed an inverse relationship between perceived risk and distress [15]. As patients move through their treatment, their distress levels increase while perceived risk declines, highlighting the psychological complexity of BC cancer recovery.

Previous studies have shown that distress is highest in the first-month post-treatment and gradually decreases over time. For example, one study found that distress levels drop significantly within 12 months of treatment completion [38]. Comorbid depression can amplify the distress experienced by BC patients, underscoring the importance of integrating mental health screening from the point of diagnosis through post-treatment care [39]. Referrals to mental health professionals for psychological counseling and support could improve patients’ self-regulation capacities and overall well-being.

Physical activity was significantly higher among patients who had completed treatment compared to those still undergoing treatment. Kelly et al.’s research supports this, showing that post-treatment patients are more physically active than those who are newly diagnosed and in active treatment [22]. Ormel et al. have identified several factors influencing physical activity, including a history of exercise, fewer physical limitations, and family support [40]. Rogers also demonstrated that aerobic exercise and muscle strengthening improved post-treatment outcomes for BC survivors [41]. These findings suggest that the treatment process, along with its side effects, reduces the opportunity and motivation for physical activity, which improves once treatment is completed.

Among the constructs of the self-regulation model, perceived treatment efficacy was strongly associated with health-promoting behaviors, such as maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in physical activity, and taking vitamins, but it was inversely associated with regular mammography. This aligns with the findings of Cyriac et al., demonstrating that self-regulation enhanced adherence to a healthy diet [42], and Rainey et al., reporting improvements in health-promoting behaviors among women educated about BC risk factors, highlighting the role of awareness in lifestyle change [43]. However, according to Kelly et al.’s study, individuals undergoing active treatment consume less healthy food, use fewer vitamins, and attend fewer clinical examinations compared to those who had completed treatment. Additionally, higher perceived treatment effectiveness was linked to improved diet and vitamin use but showed no association with exercise or cancer screening [22]. Rastad et al. also revealed that while 55% of individuals have limited knowledge about BC, around 90% exhibit poor performance [44]. In our study, the limitations of accessing mammography in the public sector, the high cost in the private sector, and the difficulty of securing an appointment due to the limited number of centers available in the research environment at the time of the study may explain this behavior among patients.

The self-regulation model emphasizes that individuals adjust their behaviors in response to psychologically stimulating events, such as illness, by leveraging self-efficacy and feedback over time [15].

Patient registries are instrumental in understanding health outcomes and play a critical role in disease prevention and health improvement. By addressing the multifaceted needs of cancer patients, health-oriented models can utilize registry data to inform targeted interventions, ultimately optimizing health outcomes.

Although this study faced challenges, such as patients’ reluctance to respond during active treatment, it highlights the importance of understanding the psychological and behavioral dimensions of BC recovery. Future studies should explore educational interventions based on the self-regulation model to promote health-enhancing behaviors in both active and post-treatment BC patients.

Conclusion

Perceived treatment effectiveness is closely linked to enhanced health-promoting behaviors.

Acknowledgments: This article is based on a master’s thesis in health education. We extend our sincere gratitude to the Vice President of Research and Technology at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, the breast cancer registry team at the hospital, and, most importantly, the courageous patients who participated in this study. Their strength and perseverance in battling the disease and working toward recovery are deeply appreciated.

Ethical Permissions: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Guilan University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.GUMS.REC.1399.297. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, ensuring their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any repercussions.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Ashoobi MT (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (20%); Bakhshi F (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Saeidi Saedi H (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (15%); Shakiba M (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Mahdavi-Roshan M (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (5%); Marhaba M (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Nikpey N (Seventh Author), Assistant Researcher (5%)

Funding/Support: This article is based on a research project numbered 723, which was approved and financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Breast cancer (BC) remains a significant public health concern globally [1], with rising incidence rates and varying survival outcomes influenced by numerous factors, including healthcare systems and treatment accessibility [2]. Among the types of cancer, BC is a common, malignant, and progressive disease that affects various aspects of a person’s life [3]. According to a report from the World Health Organization, 2.3 million women had BC, and 685 thousand died from it in 2020 [4]. In Iran, recent statistics indicate a concerning trend; the average age of women diagnosed with BC has decreased by approximately ten years, highlighting the urgent need for effective health promotion strategies tailored to this demographic [5]. Understanding the implications of these survival rates not only sheds light on the effectiveness of the Iranian healthcare system but also underscores the necessity for improved treatment options and preventive measures [6]. Health-promoting behaviors play a crucial role in the prevention and management of BC [7]. Decision-making in patients with BC has largely focused on treatment options, with less attention paid to health-promoting behaviors such as a healthy diet, regular exercise and physical activity, vitamin intake, and timely screening [8]. The growing trend of chronic diseases and the importance of improving the quality of life for this group of patients, along with increasing their lifespan, have made the need for health promotion interventions and a healthy lifestyle more prominent than ever [9]. For more effective training and interventions, it is a priority to identify the factors that predict behaviors in order to design appropriate and effective training for these individuals based on a suitable model [10].

Health-promoting behaviors represent a multidimensional model of voluntary and cognitive actions that lead to maintaining and enhancing health, self-actualization, and success [11]. Meanwhile, the task of health education—both in understanding health behaviors and in transferring knowledge related to health behavior—is to create an effective strategy for increasing the level of healthy behavior. This defines the scope of practices by using models and theories as frameworks for shaping rules in the field of health [12] and helps identify individual and environmental characteristics that influence human behavior [13]. Since one of the goals of health professionals is to assist patients in responding appropriately to risk factors for diseases [14], it is essential to establish a clear connection between these behaviors and their impact on BC outcomes [15]. This connection will provide a foundation for exploring the self-regulation model, which serves as a framework for understanding how individuals can manage their health proactively [16].

Self-regulation is the act of modifying behavior based on self-observations. Accordingly, the self-regulation model was proposed in 1980 by Leventhal et al., and it includes three components of interpretation, adaptation, and evaluation [15, 17]. The interpretation stage is related to the recognition of health-threatening factors, which enables the individual to address their potential disease problem through the perception of disease symptoms and their social consequences [18].

The adaptation or action plan stage is characterized by efforts to control fear or other emotions related to the disease or threat. In the evaluation stage, individuals compare their level and status of performance with the degree of achievement of desired standards to identify discrepancies or differences along a spectrum of desirable to undesirable behaviors and determine what intervention is needed [19]. Self-regulation involves personal control over the monitoring of behaviors, thoughts, and emotions through a continuous cycle of review to manage an identified or emerging problem, to produce a desired outcome or avoid an undesirable outcome [20]. Therefore, the self-regulation model can be used to explain how beliefs or knowledge about a disease may interfere with the recognition and management of its symptoms, considering the individual as an active problem-solving agent in the management of their disease [21]. This model specifically includes the self-system, cognitive and emotional experiences, and health-promoting behaviors. The self-system comprises self and social environmental factors that are essential for understanding health threats. It includes demographic factors (age, socioeconomic factors, etc.), biological factors (passive treatment), and cultural and regional factors (such as rural areas). When the self-system is presented with a stimulus like BC, a cognitive and emotional experience of the health threat is formed in the individual. Cognitive experiences may include salient features of the disease, such as, “What is the disease?” or “What is the impact of a health-promoting behavior?” [15, 22]

In justifying the role of the self-regulation model in the health-promoting behaviors of BC patients, it can be stated that the psychosocial factors of the model, such as distress, perceived risk, and perceived treatment effectiveness, are integrated into the interpretation stage. This integration allows patients to gain a correct understanding of their disease and to follow the recommendations and training provided to manage their condition. This accurate understanding of their health status can reduce mortality, complications, and adverse outcomes of the disease while improving quality of life. Subsequently, in the evaluation stage, patients address the objective aspects of the disease along with the strategies they have selected and planned to achieve the health-related goals resulting from the disease understanding stage. Finally, in the evaluation stage, by comparing their own performance and behavior with the desired level, they can determine which types of health-oriented behaviors to select and implement [20, 22]. Since there is a significant relationship between perceived treatment effectiveness and patients’ cultural status, which affects their healthcare behaviors and attitudes [23], this study aimed to determine the health-promoting behaviors among BC patients in the North of Iran, focusing on how social, cultural, and economic factors influence these behaviors. By examining this specific population, we can identify unique characteristics that may affect their health management strategies, such as regional healthcare access and cultural beliefs.

Furthermore, this research aimed to engage with the existing literature on health-promoting behaviors in BC patients, identifying a profile of patients’ lifestyles. By doing so, we hope to reinforce the significance of our research within the broader context of health promotion. The findings of this study could inform future interventions and health policies aimed at enhancing health-promoting behaviors among BC patients, ultimately contributing to improved health outcomes.

Instrument and Methods

Study type, setting, and participants

This cross-sectional analytical study aimed to identify predictors of health-promoting behaviors based on the self-regulation model among BC patients registered in the hospital/clinical breast cancer registry program at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, conducted in 2021.

The sample size was determined using Kline’s formula [24], which suggested a requirement of five observations per item across 47 items, with an additional 10% accounted for attrition, resulting in a calculated sample size of 260 participants.

The national clinical breast cancer registry program in Iran, established in 2018, is a collaborative effort involving 12 provinces and 15 hospitals. This registry collects over 160 data items, including patient demographics, diagnostic factors, treatment modalities, and follow-up information for BC patients admitted for initial treatment. By the time of this study, 497 patients had been registered in the clinical cancer registry program of Guilan province. Participants were selected using a simple random sampling method based on the existing sampling framework from the hospital BC registration system database. Random numbers were generated using the Excel program and assigned to the corresponding patient file numbers.

Inclusion criteria included a newly confirmed diagnosis of BC, registration in the hospital BC registry program at treatment units affiliated with Guilan University of Medical Sciences (specifically Razi Hospital and Pursina Hospital), and being in either the active or inactive treatment stage (completion of treatment). Patients who did not respond to the questionnaire items were excluded, as were those unwilling to participate and individuals with metastasis or recurrence.

Procedure

Following approval from the Ethics Committee, registered patients were offered a complimentary consultation with an oncology specialist. On the day of the clinic visit, the researcher introduced herself, obtained informed consent, ensured confidentiality, and explained the study’s purpose. The questionnaire was then administered to participants, with the researcher conducting interviews with illiterate patients. The second part of the questionnaire, concerning disease status, was completed by the researcher based on the patient’s medical records and guidance from the attending physician. Data collection spanned five months, from October 7, 2020, to March 10, 2021.

Questionnaires

Data were collected using a questionnaire divided into four sections. The first section gathered demographic information, including age, body mass index (BMI), education level, employment status, marital status, family income, family history of disease, and participants’ self-assessment of their health status, rated from poor to excellent. The second section focused on health-promoting behaviors, which were assessed using a scale that measured various dimensions of health-related activities, including physical activity, nutrition, vitamin consumption, and mammography.

Physical activity was measured using the standard International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [25]. This questionnaire was validated in a study conducted across 12 countries and has demonstrated strong reliability, with a test-retest Spearman correlation of approximately 0.8 [26]. Nutrition was assessed using questions related to healthy eating from the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLP II) Questionnaire [27, 28]. Vitamin consumption was evaluated using three questions, and mammography was determined by two questions. The reliability of these two sections of the questionnaire was assessed using test-retest reliability on 20 subjects, yielding a correlation coefficient of 0.79 for vitamin consumption and 0.97 for mammography.

The third section evaluated the participants’ psychological factors related to self-regulation skills. It included questions concerning the psychosocial factors of the self-regulation model, which the research team prepared based on Kelly et al.’s study [22], and results from library studies, including anxiety and depression levels, perceived risk, and perceived treatment effectiveness (Table 1). According to the panel of experts, the content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were 0.8 and 0.88 for distress, 0.7 and 1 for perceived risk, and 0.88 and 0.98 for perceived treatment effectiveness, respectively. The corresponding Cronbach’s alpha values for distress, perceived risk, and perceived treatment effectiveness were 0.92, 0.79, and 0.89, respectively.

Finally, the fourth section collected information on the participants’ disease-related factors, such as the stage of cancer, treatment modalities, and duration since diagnosis.

Table 1. The subscales, items, scores, and psychometric properties of the scale

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics. The correlation between parameters was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. To identify predictors of health-promoting behaviors, a multivariate linear regression analysis was performed using the backward elimination method. This approach allowed for the adjustment of confounding parameters and the identification of significant predictors of health-promoting behaviors among the participants. The significance level was set at p<0.05 for all analyses.

Findings

A total of 260 patients participated in this study, with a mean age of 52.6±10.6 years. Over 80% of the participants had completed diploma or sub-diploma education, and 87.7% were housewives. Approximately 94% of the patients were married, and the majority reported a family income ranging from 10 to 30 million IRR. Notably, 50% of the subjects had an underlying health condition. Also, the BMI of participants was found to be28.00±3.58kg/m2 (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Frequency of background characteristics of the participants (n=260)

Table 3. Frequency of clinical characteristics of the participants (n=260)

The most prevalent cancer type among participants was ductal carcinoma (p=0.4), while stage 2 cancer was the most common disease stage (p=0.27). More than 70% of patients tested positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors (p=0.88).

Significant positive correlations were found between perceived treatment effectiveness and a healthy diet (r=0.14, p<0.01), vitamin consumption (r=0.17, p<0.001), physical activity (r=0.13, p<0.01), and mammography (r=0.24, p<0.001). An inverse correlation was observed between distress and perceived risk (r=-0.59, p<0.001; Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation coefficients between the constructs of the self-regulation model and dimensions of health-promoting behaviors

Linear regression analysis revealed a significant association between perceived treatment effectiveness and adherence to healthy behaviors, including diet, vitamin consumption, and mammography. Overall, higher perceived treatment effectiveness correlated with increased engagement in health-promoting behaviors (Table 5).

Table 5. Predictors of various dimensions of health-promoting behaviors using linear regression model

Age was identified as a significant independent factor influencing health-promoting behaviors, particularly physical activity, vitamin consumption, and mammography. Specifically, increasing age was associated with a significant decrease in physical activity (B=-3.7, p<0.001) and mammography scores (B=-0.03, p=0.013), while it correlated with an increase in vitamin consumption (B=0.04, p=0.031).

Furthermore, treatment status emerged as an independent predictor of physical activity, with treated individuals reporting lower average physical activity scores compared to those who had completed treatment (B=-52.29, p=0.02). A significant dose-response relationship was also noted, indicating that a better assessment of health condition was associated with higher levels of physical activity (p<0.05).

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the predictors of health-promoting behaviors in breast cancer patients in northern Iran, using the self-regulation model. BC remains the most common cancer among women worldwide and is the leading cause of cancer-related death in 11 regions globally [29]. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle not only reduces the risk of BC but also enhances recovery and survival, particularly in postmenopausal women [30, 31].

Patients who had completed treatment reported significantly higher levels of distress than those undergoing active treatment. This is consistent with Thakur et al.'s study in North India, finding heightened distress and poor body image in the early months after completing treatment [32]. The long-term decline in distress aligns with the findings of Sajjadyan et al., noting that BC patients adapt over time, utilizing problem-solving strategies and spirituality to cope [33]. The fear of disease recurrence can exacerbate distress, particularly in the post-treatment phase [34]. Corkum et al. also observed that higher distress scores are associated with reduced rates of immediate breast reconstruction post-treatment [35], while Westbrook et al. noted that distress peaks at symptom recurrence and is lowest during the first course of treatment [36]. These findings emphasize the need for psychological support even after treatment concludes, with palliative care planning playing a crucial role in addressing distress.

In terms of perceived risk, patients undergoing active treatment had significantly higher scores than those who had completed treatment. This observation aligns with Attari et al.’s findings, showing that higher perceived risk correlates with shorter treatment delays [37]. According to Leventhal’s self-regulation model, emotional responses to illness influence individuals’ coping strategies. Our results suggest that at the beginning of diagnosis and treatment, perceived risk is high, driving patients to initiate treatment. As treatment progresses and uncertainty diminishes, perceived risk decreases. Interestingly, we also observed an inverse relationship between perceived risk and distress [15]. As patients move through their treatment, their distress levels increase while perceived risk declines, highlighting the psychological complexity of BC cancer recovery.

Previous studies have shown that distress is highest in the first-month post-treatment and gradually decreases over time. For example, one study found that distress levels drop significantly within 12 months of treatment completion [38]. Comorbid depression can amplify the distress experienced by BC patients, underscoring the importance of integrating mental health screening from the point of diagnosis through post-treatment care [39]. Referrals to mental health professionals for psychological counseling and support could improve patients’ self-regulation capacities and overall well-being.

Physical activity was significantly higher among patients who had completed treatment compared to those still undergoing treatment. Kelly et al.’s research supports this, showing that post-treatment patients are more physically active than those who are newly diagnosed and in active treatment [22]. Ormel et al. have identified several factors influencing physical activity, including a history of exercise, fewer physical limitations, and family support [40]. Rogers also demonstrated that aerobic exercise and muscle strengthening improved post-treatment outcomes for BC survivors [41]. These findings suggest that the treatment process, along with its side effects, reduces the opportunity and motivation for physical activity, which improves once treatment is completed.

Among the constructs of the self-regulation model, perceived treatment efficacy was strongly associated with health-promoting behaviors, such as maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in physical activity, and taking vitamins, but it was inversely associated with regular mammography. This aligns with the findings of Cyriac et al., demonstrating that self-regulation enhanced adherence to a healthy diet [42], and Rainey et al., reporting improvements in health-promoting behaviors among women educated about BC risk factors, highlighting the role of awareness in lifestyle change [43]. However, according to Kelly et al.’s study, individuals undergoing active treatment consume less healthy food, use fewer vitamins, and attend fewer clinical examinations compared to those who had completed treatment. Additionally, higher perceived treatment effectiveness was linked to improved diet and vitamin use but showed no association with exercise or cancer screening [22]. Rastad et al. also revealed that while 55% of individuals have limited knowledge about BC, around 90% exhibit poor performance [44]. In our study, the limitations of accessing mammography in the public sector, the high cost in the private sector, and the difficulty of securing an appointment due to the limited number of centers available in the research environment at the time of the study may explain this behavior among patients.

The self-regulation model emphasizes that individuals adjust their behaviors in response to psychologically stimulating events, such as illness, by leveraging self-efficacy and feedback over time [15].

Patient registries are instrumental in understanding health outcomes and play a critical role in disease prevention and health improvement. By addressing the multifaceted needs of cancer patients, health-oriented models can utilize registry data to inform targeted interventions, ultimately optimizing health outcomes.

Although this study faced challenges, such as patients’ reluctance to respond during active treatment, it highlights the importance of understanding the psychological and behavioral dimensions of BC recovery. Future studies should explore educational interventions based on the self-regulation model to promote health-enhancing behaviors in both active and post-treatment BC patients.

Conclusion

Perceived treatment effectiveness is closely linked to enhanced health-promoting behaviors.

Acknowledgments: This article is based on a master’s thesis in health education. We extend our sincere gratitude to the Vice President of Research and Technology at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, the breast cancer registry team at the hospital, and, most importantly, the courageous patients who participated in this study. Their strength and perseverance in battling the disease and working toward recovery are deeply appreciated.

Ethical Permissions: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Guilan University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.GUMS.REC.1399.297. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, ensuring their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any repercussions.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Ashoobi MT (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (20%); Bakhshi F (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Saeidi Saedi H (Third Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (15%); Shakiba M (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Mahdavi-Roshan M (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (5%); Marhaba M (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Nikpey N (Seventh Author), Assistant Researcher (5%)

Funding/Support: This article is based on a research project numbered 723, which was approved and financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2024/12/31 | Accepted: 2025/01/30 | Published: 2025/02/5

Received: 2024/12/31 | Accepted: 2025/01/30 | Published: 2025/02/5

References

1. Sahle BW, Chen W, Melaku YA, Akombi BJ, Rawal LB, Renzaho AM. Association of psychosocial factors with risk of chronic diseases: A nationwide longitudinal study. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(2):e39-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.09.007]

2. Bullard T, Ji M, An R, Trinh L, Mackenzie M, Mullen SP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of adherence to physical activity interventions among three chronic conditions: Cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):636. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-019-6877-z]

3. Izzo MC, Bronner G, Shields CL. Rapidly progressive vision loss in a patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1098-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.12691]

4. WHO. World health statistics 2020: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

5. Abedi G, Janbabai G, Moosazadeh M, Farshidi F, Amiri M, Khosravi A. Survival rate of breast cancer in Iran: A meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(10):4615-21. [Link]

6. Keihanian S, Ghadi SF, Zakerihamidi M, Saravi A, Saravi S, Saravi MM. Evaluation of lifestyle in women with breast cancer referred to Imam Sajad Hospital, Ramsar in 2015. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2017;26(94):11-8. [Persian] [Link]

7. Motlagh Z, Mazloomy-Mahmoodabad S, Momayyezi M. Study of health-promotion behaviors among university of medical science students. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2011;13(4):e93999. [Persian] [Link]

8. Amireault S, Fong AJ, Sabiston CM. Promoting healthy eating and physical activity behaviors: A systematic review of multiple health behavior change interventions among cancer survivors. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12(3):184-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1559827616661490]

9. Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Fernández ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Link]

10. Kelder SH, Hoelscher D, Perry CL. How individuals, environments, and health behaviors interact. In: Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass; 2015. p. 159-81. [Link]

11. Choi MJ, Kim S, Jeong SH. Factors associated with health-promoting behaviors among nurses in south Korea: Systematic review and meta-analysis based on pender's health promotion model. Asian Nurs Res. 2024;18(2):188-202. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.anr.2024.04.007]

12. Kongsted A, Ris I, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J. Self-management at the core of back pain care: 10 key points for clinicians. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021;25(4):396-406. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bjpt.2021.05.002]

13. Parker E, Fleming ML. Health promotion: Principles and practice in the Australian context. London: Routledge; 2020. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9781003115892]

14. Smit DJ, Proper KI, Engels JA, Campmans JM, Van Oostrom SH. Barriers and facilitators for participation in workplace health promotion programs: Results from peer-to-peer interviews among employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2022;96(3):389-400. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00420-022-01930-z]

15. Leventhal H. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. London: Routledge; 2003. [Link]

16. Meuleman Y, Van Der Bent Y, Gentenaar L, Caskey FJ, Bart HA, Konijn WS, et al. Exploring patients' perceptions about chronic kidney disease and their treatment: A qualitative study. Int J Behav Med. 2024;31(2):263-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12529-023-10178-x]

17. Burke LE, Dunbar-Jacob J, Orchard TJ, Sereika SM. Improving adherence to a cholesterol-lowering diet: A behavioral intervention study. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(1):134-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2004.05.007]

18. Wyne M. Depression in cancer patients: An examination of the role of self-efficacy for coping with cancer and dispositional optimism [dissertation]. Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 2001. [Link]

19. Sniehotta FF, Schwarzer R, Scholz U, Schüz B. Action planning and coping planning for long‐term lifestyle change: Theory and assessment. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2005;35(4):565-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ejsp.258]

20. Ungar N, Sieverding M, Weidner G, Ulrich CM, Wiskemann J. A self-regulation-based intervention to increase physical activity in cancer patients. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21(2):163-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2015.1081255]

21. Browning KK, Wewers ME, Ferketich AK, Otterson GA, Reynolds NR. The self-regulation model of illness applied to smoking behavior in lung cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(4):E15-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181a0238f]

22. Kelly KM, Bhattacharya R, Dickinson S, Hazard H. Health behaviors among breast cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(3):E27-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000167]

23. Shahin W, Kennedy GA, Stupans I. The impact of personal and cultural beliefs on medication adherence of patients with chronic illnesses: A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1019-35. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S212046]

24. Kline RB. Beyond significance testing: Statistics reform in the behavioral sciences. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/14136-000]

25. Booth M. Assessment of physical activity: An international perspective. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71 Suppl 2:114-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/02701367.2000.11082794]

26. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB]

27. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. Health promotion model-instruments to measure health promoting lifestyle: Health-promoting lifestyle profile [HPLP II] (Adult version). Michigan: The University of Michigan. [Link]

28. Tanjani PT, Azadbakht M, Garmaroudi G, Sahaf R, Fekrizadeh Z. Validity and reliability of health promoting lifestyle profile II in the Iranian elderly. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:74. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2008-7802.182731]

29. Montagnese C, Porciello G, Vitale S, Palumbo E, Crispo A, Grimaldi M, et al. Quality of life in women diagnosed with breast cancer after a 12-month treatment of lifestyle modifications. Nutrients. 2020;13(1):136. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu13010136]

30. Li Q, Lesseur C, Neugut AI, Santella RM, Parada Jr H, Teitelbaum S, et al. The associations of healthy lifestyle index with breast cancer incidence and mortality in a population-based study. Breast Cancer. 2022;29(6):957-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12282-022-01374-w]

31. Connor AE, Dibble KE, Visvanathan K. Lifestyle factors in black female breast cancer survivors-descriptive results from an online pilot study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:798. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1072741]

32. Thakur M, Sharma R, Mishra AK, Singh K, Kar SK. Psychological distress and body image disturbances after modified radical mastectomy among breast cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary care centre in North India. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022;7:100077. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100077]

33. Sajjadyan A, Haghighat Sh, Montazeri A, Kazemnezhad A, Alavi A. Post diagnosis coping strategies patients with breast cancer. Iran J Breast Dis. 2011;4(3):52-8. [Persian] [Link]

34. Freeman‐Gibb LA, Janz NK, Katapodi MC, Zikmund‐Fisher BJ, Northouse L. The relationship between illness representations, risk perception and fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2017;26(9):1270-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pon.4143]

35. Corkum JP, Butler K, Zhong T. Higher distress in patients with breast cancer is associated with declining breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(2):e2636. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002636]

36. Westbrook TD, Morrison EJ, Maddocks KJ, Awan FT, Jones JA, Woyach JA, et al. Illness perceptions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Testing Leventhal's self-regulatory model. Ann Behav Med. 2018;53(9):839-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/abm/kay093]

37. Attari SM, Ozgoli G, Solhi M, Alavi Majd H. Study of relationship between illness perception and delay in seeking help for breast cancer patients based on Leventhal's self-regulation model. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(S3):167-74. [Link] [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.S3.167]

38. Ng CG, Mohamed S, Kaur K, Sulaiman AH, Zainal NZ, Taib NA, et al. Perceived distress and its association with depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172975. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0172975]

39. Sayed S, El-Sherief M, Mahfouz E, Hassan E, Elsaeed A, Abdelrehim M. Screening for psychological distress and affective state among cancer patients in Minia. Minia J Med Res. 2023;34(4):83-92. [Link]

40. Ormel H, Van Der Schoot G, Sluiter W, Jalving M, Gietema J, Walenkamp A. Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):713-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pon.4612]

41. Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, Markwell S, et al. A randomized trial to increase physical activity in breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(4):935-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818e0e1b]

42. Cyriac J, Jenkins S, Patten CA, Hayes SN, Jones C, Cooper LA, et al. Improvements in diet and physical activity-related psychosocial factors among African Americans using a mobile health lifestyle intervention to promote cardiovascular health: The FAITH! (fostering African American improvement in total health) app pilot study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2021;9(11):e28024. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/28024]

43. Rainey L, Van Der Waal D, Donnelly LS, Southworth J, French DP, Evans DG, et al. Women's health behaviour change after receiving breast cancer risk estimates with tailored screening and prevention recommendations. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):69. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12885-022-09174-3]

44. Rastad H, Shokohi L, Dehghani SL, Motamed Jahromi M. Assessment of the awareness and practice of women vis-à-vis breast self-examination in Fasa in 2011. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2013;3(1):75-80. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |