Volume 13, Issue 2 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(2): 235-240 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sarhadi M. Iranian Nurses' Attitudes Toward Death and Their Understanding of Spirituality and Spiritual Care. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (2) :235-240

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78712-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78712-en.html

“Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery,” and “Community Nursing Research Center”, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Keywords: Attitude [MeSH], Spirituality [MeSH], Nurses [MeSH], Attitudes to Death [MeSH], Iran [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 568 kb]

(243 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (413 Views)

Full-Text: (35 Views)

Introduction

Death has a disturbing resonance in the human mind, engaging the individual’s entire being in the issue of existence. This is because humans understand that death is the ultimate end [1]. Human limitations have become a significant and shocking concern, to the extent that many consider it one of the most unpleasant aspects of humanity and its helplessness in the face of the future and death [2]. People often avoid death anxiety by distancing death from everyday life and placing its burden on the shoulders of health professionals, especially nurses. However, nurses, like others, experience death anxiety or fear of death and are at risk of depression [3]. This type of anxiety is rooted in the awareness of death and is defined as a negative emotional reaction triggered by the anticipation of death and the loss of a person [2]. Nurses are constantly confronted with death and are more affected by it than other individuals. Furthermore, they are expected to perceive death as a physiological process rather than an abstract and unknown concept [3, 4]. Nevertheless, individuals’ attitudes toward all phenomena, including death, are influenced by their worldview and approach to the social world [2].

Nurses who experience death anxiety or fear of death may exhibit negative attitudes, such as avoiding dying patients, refraining from conversations with them—especially regarding the future—displaying a dull expression on their faces, withholding information, spending limited time with patients’ families, pretending to be busy, and focusing on patients who are more likely to survive [3, 4]. These negative attitudes not only make it more difficult for nurses to overcome challenges but also lead to anxiety, sadness, depression, and anger, ultimately hindering their ability to provide high-quality and holistic care [3]. Therefore, nurses who care for dying patients must possess sufficient knowledge and skills to deliver effective care and develop effective stress-coping mechanisms. They need training on how to provide comprehensive care to address not only the physical and psychological needs but also the social and spiritual needs of dying patients [5, 6]. Nurses bear the greatest responsibility in this regard [3].

Spiritual care is an important component of nursing practice that plays a vital role in achieving nursing goals, as nursing involves maintaining and promoting health, preventing disease, and alleviating pain and discomfort [7]. Nurses are responsible for meeting the care needs of dying patients and their families, which includes physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual assessment and care [3]. Spiritual care also encompasses attitudes and behaviors shaped by nurses’ spiritual nursing values [8] and specifically affirms human qualities such as dignity, goodness, benevolence, peace of mind, warmth, self-care, and care for others. It includes care that reflects the cultures and beliefs of individuals, provided after assessing their spiritual needs and challenges. This type of care relies on companionship, attentive listening, and religious activities that align with patients’ beliefs, helping them achieve better physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health and well-being [9].

Various studies in this field have shown that nursing care combined with spirituality enhances nursing performance and the quality of patient care. This type of care reduces physical pain, depression, and anxiety, increases psychological relief; accelerates recovery, extends life expectancy; improves quality of life, and deepens the patient-nurse relationship [10, 11]. To achieve these goals, nurses should consider spirituality an integral part of the human experience of illness and health. Therefore, healthcare professionals should adopt a patient-centered care approach, identify and respect the spiritual needs of patients, collaborate with other disciplines, and provide spiritual care competently and compassionately. They should become familiar with scientific studies in the field of spirituality and apply their knowledge in practice. Nurses are also responsible for fostering positive attitudes and providing care for dying patients and their families. They should be able to identify patients’ spiritual needs at the end of life [12, 13]. However, nurses find it challenging to provide spiritual care to patients and believe that doing so is beyond their abilities due to a lack of training in this area [7, 14, 15]. Research also indicates that nurses do not have sufficient knowledge regarding spiritual care and struggle to recognize the spiritual needs of patients. Difficulties in defining the concept of spirituality, along with a lack of time and privacy, costs, and various individual, cultural, and institutional factors, prevent nurses from providing effective spiritual care and lead to additional suffering for patients [3, 14]. For this reason, an emphasis has been placed on their focus on holistic care in addressing the spiritual needs of patients [15].

With the increasing demand for spiritual care, researchers have focused on studying spirituality, spiritual needs, and spiritual care [14]. However, the current issue in the Iranian nursing system regarding the spiritual care of patients is that this type of care lacks a specific framework for nurses and is intentionally not included in formal education curricula [7]. Nurses who are aware of their patients’ spiritual needs can better understand them and provide more effective care. Increasing nurses’ awareness of their own spirituality can improve their attitudes toward death and help them deliver higher-quality care for dying patients and their families in both their personal and professional lives [3]. For this reason, the present study was designed and implemented to investigate nurses’ attitudes toward death and their understanding of spirituality and spiritual care.

Instrument and Methods

The present descriptive, analytical, and cross-sectional study was done on Iranian nurses working in five teaching hospitals in southeastern Iran (Kerman and Zahedan) in 2024-2025. After reviewing similar studies and using formulas to determine the sample size, 237 participants were included in the study. Sampling was conducted using a multi-stage method. In the first stage, a quota was assigned to each hospital based on the number of nurses in each facility. In the second stage, a list of all nurses in each hospital was prepared, and the desired sample was selected using systematic random sampling. The participants were selected from nurses working in different departments of the hospitals who had direct and continuous contact with patients.

Three questionnaires were utilized for data collection. The demographic information questionnaire focused on the demographic characteristics of the nurses.

The Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS) includes 23 questions divided into two main sections, including spirituality and spiritual care. The first section of this scale covers nine fundamental domains (indices) related to spirituality, including hope, meaning and purpose, forgiveness, beliefs and values, relationships, belief in God, ethics, innovation, and self-expression. This section comprises questions 3-6, 10, 11, 14-17, and 21-23 from the aforementioned instrument. The second section includes questions related to spiritual care and interventions that are deemed important in the literature, which encompass indicators, such as listening, spending time, respecting the patient’s privacy and dignity, maintaining religious practices, and providing care through expressions of kindness and attention. This section includes questions 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 18, 19, and 20. A five-point Likert scale was used for scoring, with the highest possible score being 92 and the lowest being zero. Scores ranging from 63 to 92 were considered high and desirable, scores from 32 to 62 were regarded as average and somewhat desirable, and scores from 0 to 31 were classified as low and undesirable. The validity and reliability of this scale have been previously investigated in a study by Mazaheri et al. [16]. To assess the content validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire, the opinions of faculty members were solicited. Thus, the instrument was provided to ten faculty members with various specialties related to the subject at the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. To determine the reliability of the scale, the test-retest method was employed [16].

To examine nurses’ attitudes toward death, the revised form of the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (DAP-R) was used. This scale was developed by Wang et al. It is a 32-item scale that assesses five dimensions of attitudes toward death, including fear of death, death avoidance, neutral acceptance (where the individual accepts the reality of death but does not consider it good or bad), active acceptance (where the individual accepts the reality of death but views it as a means to achieve happiness and well-being), and evasive acceptance (where the individual accepts the reality of death but sees it as a way to escape from life’s problems). These five dimensions reflect both positive (acceptance subscales) and negative (fear and avoidance subscales) attitudes toward death. Participants indicate their responses on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The scores for the questions related to each subscale are summed and divided by the number of questions to obtain the average score for that subscale, with higher scores indicating greater acceptance, fear, and avoidance of death. The validity and reliability of this scale have also been investigated in a study by Basharpoor et al. [17]. Wang et al. reported internal consistency reliability for these five subscales, ranging from 0.97 for the active acceptance subscale to 0.65 for the neutral acceptance subscale. The test-retest reliability of this scale after four weeks was also found to range from 0.61 for the acceptance subscale to 0.95 for the avoidance subscale [18].

In their study, the questionnaire was translated from English to Persian and back again by two individuals (the first author and a senior English language expert), and the content of the questions was confirmed. Its face validity was assessed by three psychologists with PhDs in psychology. Cronbach’s alpha was used to determine the reliability of the scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the subscales of this test ranged from 0.64 for the death avoidance subscale to 0.88 for the active acceptance of death subscale. The Cronbach’s alpha method was employed to assess the reliability of both tools.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22 software. Descriptive and inferential statistical tests were used to create tables and achieve the research objectives. After checking the normality of the data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, Pearson and Spearman correlation tests, t-tests, and ANOVA were utilized at a significance level of p<0.05.

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 31.15±2.57 years (with a minimum age of 23 and a maximum age of 54 years). Of the participants, 84% were female and 16% were male; 37.9% were single, 92% had no chronic illness, and 73% had never been hospitalized. Also, 72.1% of the participants had previously witnessed death, 60.3% had cared for dying patients, 27.3% felt regret and discomfort while providing care, 69.1% did not wish to care for dying patients, 30.1% claimed to be coping with death, and 75.1% felt incompetent in caring for dying patients. Additionally, 24.3% had received training about death, with 75% of those receiving it during their undergraduate years, and 84.71% considered the training to be insufficient.

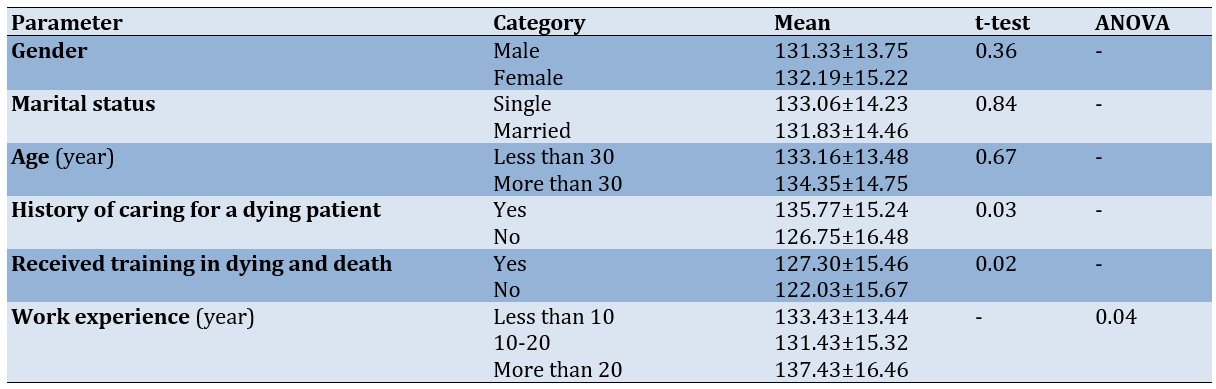

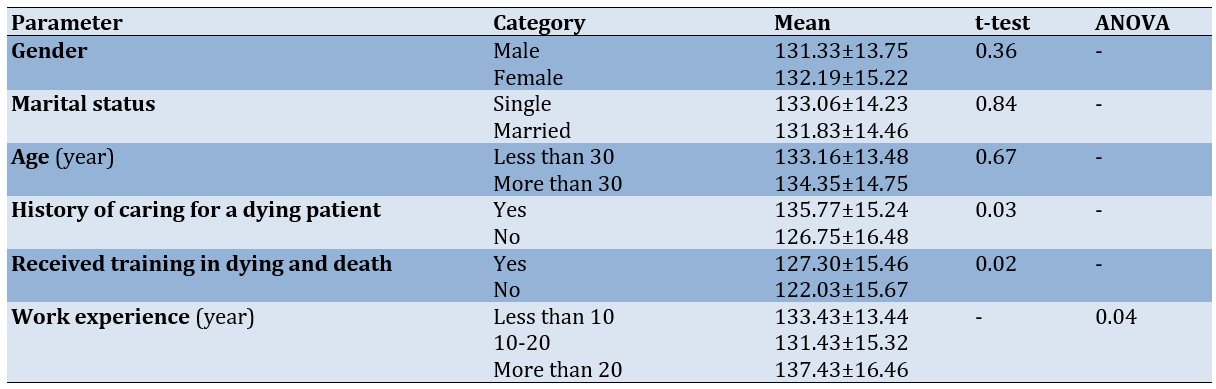

Furthermore, 91.7% believed that special importance should be given to spiritual care for dying patients and their families, while 81.7% were unaware of spiritual care. Among those who knew about spiritual care, 34% learned about it during their undergraduate studies, and 89.1% thought that the education on spiritual care provided by universities was inadequate. Of the participants, 79.2% felt incompetent in caring for dying patients, and 89.2% felt they had not received sufficient training during their education and work on how to care for dying patients. Among the participants who had provided spiritual care, 45.2% stated that they had done so by talking to patients, while 44.62% of those who had never provided spiritual care indicated that they had not done so due to a lack of knowledge. The study of nurses’ attitudes toward death also revealed that the average score of nurses’ attitudes was 134.80±12.57 (Table 1).

Table 1. Average scores of attitudes to death according to demographic characteristics

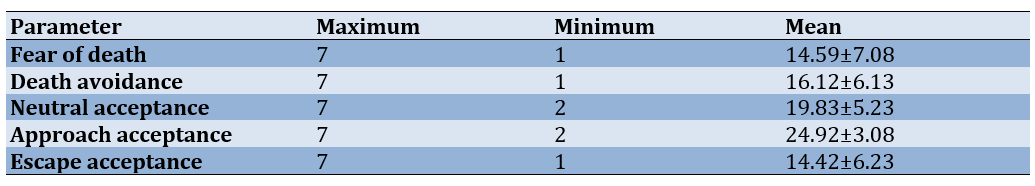

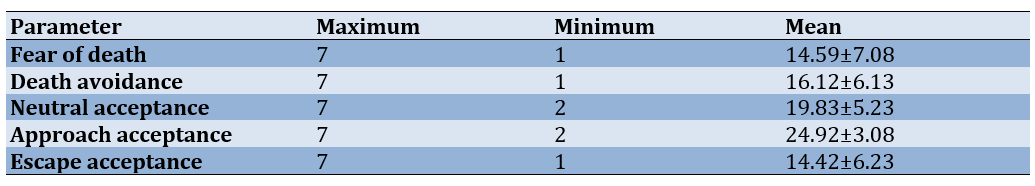

Mean nurses' attitudes to death were also examined (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean nurses' "attitudes to death"

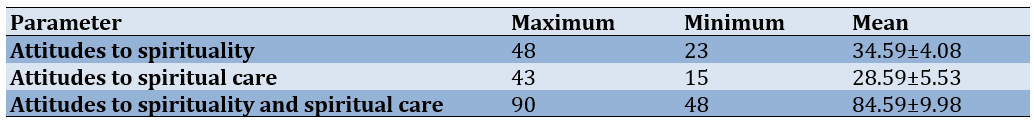

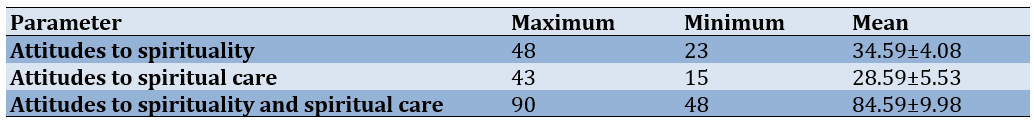

Nurses’ attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care fell within the high and desirable range. The average score of attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care among nurses was 84.59 (Table 3), with the majority of nurses (53.58%) scoring between 62 and 93.

Table 3. Mean nurses' attitudes to spirituality and spiritual care

There was no significant relationship between the mean scores of nurses’ attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care and demographic parameters (age, gender, marital status, academic semester, etc.; p≥0.005). Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficient demonstrated no significant relationship between the mean scores of nurses’ attitudes toward death and their attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care (p≥0.005).

Discussion

This study investigated nurses’ attitudes toward death and their understanding of spirituality and spiritual care. Nurses, regardless of where they work, encounter dead and dying patients; therefore, they must be trained on how to provide comprehensive care so that they can address not only the physical and psychological needs but also the social and spiritual needs of dying patients [3, 6]. The the attitude toward death among the majority of the research participants reflected an average to relatively favorable level, which is consistent with the findings of Hojjati et al. [18]. Şahin et al. and Çevik & Kav also found that more than half of nursing students and nurses do not wish to care for dying patients. Nurses who care for dying patients witness death firsthand, which forces them to confront their mortality while providing care for patients and their families [19, 20].

Nurses’ negative perceptions of death hindered them from providing effective and comprehensive care to dying patients [2, 3]. Çevik & Kav also demonstrated that Turkish nurses’ attitudes toward death and the care of dying patients are lower and more negative than those of nurses in other studies [19], which could be attributed to cultural differences [18], as the first step in accepting death is to view it as a natural process. Nurses who perceive death as the end of pain and suffering can cope with their emotions more easily. Furthermore, the mission of the nursing profession is to “keep patients alive” [3]. The variations in the results of studies examining the relationship between acceptance of death and attitudes toward caring for dying patients suggest that culture and religion can play significant roles in shaping these attitudes. Understanding the values and beliefs of healthcare providers can aid in the acceptance and comprehension of the meaning of death. Individuals who maintain positive attitudes toward death, actively accept it, view it as a pathway to eternal happiness, and recognize that death is not merely a technical or nonexistent event but a transition from one world to another—where human life continues in a different form—tend to experience better quality of life and mental health [17]. Factors, such as individual characteristics, experiences with death, education, beliefs, and the ability to discuss death may influence nurses’ attitudes toward caring for dying patients [21, 22]. A significant relationship was found between attitudes toward death and nurses’ work experience. As work experience increased, negative attitudes toward death decreased, which may be due to the experience and normalization of this issue, consistent with the findings of Hojjati et al. [18]. We also identified a significant relationship between attitudes toward death and education. Nurses who had completed training courses and workshops on caring for dying patients exhibited a more positive attitude toward death and a greater desire to care for dying patients compared to those who have not received training. This result aligns with the findings of Hojjati et al. [18]. Matsui et al. also concluded that better attitudes toward death and care for dying patients are positively related to attendance at educational seminars and negatively related to fear of death [23]. Additionally, Çevik & Kav found that there is a significant relationship between the desire to care for dying patients and attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients, indicating that a lack of experience and education leads to a negative attitude toward death, which is consistent with the results of the present study [19, 23]. The personal and professional experiences and attitudes of nurses toward death can significantly affect the care of dying patients [19]. Nurses’ attitudes toward death stem from their professional and personal lives and are influenced by various factors, such as age, religion, family circumstances, and previous experiences with death and illness. They should enhance their knowledge about death and stay informed about the latest developments so that they can effectively apply this knowledge in patient care [18].

The attitudes of Iranian nurses toward spirituality and spiritual care were higher than the median score, which suggests a high level of positive attitude among nurses regarding spirituality and spiritual care. Spirituality is one of the fundamental needs of humans, which some experts consider to encompass the highest levels of cognitive, moral, emotional, and personal development [1]. Since the nursing profession is grounded in maintaining the integrity of all aspects of patients and healthy individuals, and spirituality is one of those aspects, nurses are also responsible for providing spiritual care [12].

On the other hand, spiritual beliefs and practices are related to all aspects of a person’s life, including relationships with others, daily habits, and required behaviors [1]. Nurses who are aware of their patients’ spiritual needs understand them better and provide more effective care. Increasing nurses’ awareness of their spirituality can improve their attitudes toward death [3]. Our results are consistent with the findings of the studies by Babamohamadi et al. and Jafari et al. [24, 25]. However, it is inconsistent with the results of Shores [26] and McSherry & Jamieson [27]. Eğlence & Şimşek also demonstrated that more than half of the nurses report failing to meet the spiritual care needs of their patients [13]. There was no statistically significant relationship between other demographic parameters, such as marital status, gender, work experience, employment status, and attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care. This finding is consistent with the results of the study by Basharpoor et al. [17]. This difference can be explained by the fact that, in non-Islamic countries, spirituality may be independent of religious beliefs. However, in Iran and other Islamic countries, spirituality and religion are culturally integrated. In Iran, nurses consider spirituality to be an inseparable part of religion. The results of the present study also showed that there was a weak correlation between the SSCRS and DAP-R subscale scores. This result indicates that there is no relationship between the participants’ perception of spiritual care and their attitudes toward death; in other words, the participant’s perception of spirituality and spiritual care does not affect their attitudes toward death. This suggests that nurses’ attitudes toward death are influenced by factors other than spirituality and spiritual care. Our results are consistent with the findings of the study by Tüzer et al. [3].

It is recommended that spiritual health education be integrated into service areas and universities, dedicating a portion of the routine educational program for nurses in Iranian hospitals to spirituality and spiritual care. This approach aims to foster a more positive attitude among nursing staff. Additionally, creating an interactive environment where nurses can share their personal feelings about death and dying is encouraged, as it would help them incorporate aspects of death and spirituality into their care. The limitations of this study include the small number of participating nurses and its implementation in a restricted setting. To address these limitations, future research should assess spiritual care more broadly with a larger population and include comparisons between nurses from different hospitals and universities.

Conclusion

Education and work experience are effective in fostering a positive attitude among nurses toward death.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Vice Chancellor for Research at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences and the nursing department at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The project was approved by the institutional review board of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.028). When recruiting participants, the purpose of the study was clearly explained, and informed consent (both written and oral) was obtained. Participants were granted the right to decline or withdraw from the study at any time. They were assured of the confidentiality of all gathered data and informed that results would be shared with them upon request. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sarhadi M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (100%)

Funding/Support: No funding was received.

Death has a disturbing resonance in the human mind, engaging the individual’s entire being in the issue of existence. This is because humans understand that death is the ultimate end [1]. Human limitations have become a significant and shocking concern, to the extent that many consider it one of the most unpleasant aspects of humanity and its helplessness in the face of the future and death [2]. People often avoid death anxiety by distancing death from everyday life and placing its burden on the shoulders of health professionals, especially nurses. However, nurses, like others, experience death anxiety or fear of death and are at risk of depression [3]. This type of anxiety is rooted in the awareness of death and is defined as a negative emotional reaction triggered by the anticipation of death and the loss of a person [2]. Nurses are constantly confronted with death and are more affected by it than other individuals. Furthermore, they are expected to perceive death as a physiological process rather than an abstract and unknown concept [3, 4]. Nevertheless, individuals’ attitudes toward all phenomena, including death, are influenced by their worldview and approach to the social world [2].

Nurses who experience death anxiety or fear of death may exhibit negative attitudes, such as avoiding dying patients, refraining from conversations with them—especially regarding the future—displaying a dull expression on their faces, withholding information, spending limited time with patients’ families, pretending to be busy, and focusing on patients who are more likely to survive [3, 4]. These negative attitudes not only make it more difficult for nurses to overcome challenges but also lead to anxiety, sadness, depression, and anger, ultimately hindering their ability to provide high-quality and holistic care [3]. Therefore, nurses who care for dying patients must possess sufficient knowledge and skills to deliver effective care and develop effective stress-coping mechanisms. They need training on how to provide comprehensive care to address not only the physical and psychological needs but also the social and spiritual needs of dying patients [5, 6]. Nurses bear the greatest responsibility in this regard [3].

Spiritual care is an important component of nursing practice that plays a vital role in achieving nursing goals, as nursing involves maintaining and promoting health, preventing disease, and alleviating pain and discomfort [7]. Nurses are responsible for meeting the care needs of dying patients and their families, which includes physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual assessment and care [3]. Spiritual care also encompasses attitudes and behaviors shaped by nurses’ spiritual nursing values [8] and specifically affirms human qualities such as dignity, goodness, benevolence, peace of mind, warmth, self-care, and care for others. It includes care that reflects the cultures and beliefs of individuals, provided after assessing their spiritual needs and challenges. This type of care relies on companionship, attentive listening, and religious activities that align with patients’ beliefs, helping them achieve better physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health and well-being [9].

Various studies in this field have shown that nursing care combined with spirituality enhances nursing performance and the quality of patient care. This type of care reduces physical pain, depression, and anxiety, increases psychological relief; accelerates recovery, extends life expectancy; improves quality of life, and deepens the patient-nurse relationship [10, 11]. To achieve these goals, nurses should consider spirituality an integral part of the human experience of illness and health. Therefore, healthcare professionals should adopt a patient-centered care approach, identify and respect the spiritual needs of patients, collaborate with other disciplines, and provide spiritual care competently and compassionately. They should become familiar with scientific studies in the field of spirituality and apply their knowledge in practice. Nurses are also responsible for fostering positive attitudes and providing care for dying patients and their families. They should be able to identify patients’ spiritual needs at the end of life [12, 13]. However, nurses find it challenging to provide spiritual care to patients and believe that doing so is beyond their abilities due to a lack of training in this area [7, 14, 15]. Research also indicates that nurses do not have sufficient knowledge regarding spiritual care and struggle to recognize the spiritual needs of patients. Difficulties in defining the concept of spirituality, along with a lack of time and privacy, costs, and various individual, cultural, and institutional factors, prevent nurses from providing effective spiritual care and lead to additional suffering for patients [3, 14]. For this reason, an emphasis has been placed on their focus on holistic care in addressing the spiritual needs of patients [15].

With the increasing demand for spiritual care, researchers have focused on studying spirituality, spiritual needs, and spiritual care [14]. However, the current issue in the Iranian nursing system regarding the spiritual care of patients is that this type of care lacks a specific framework for nurses and is intentionally not included in formal education curricula [7]. Nurses who are aware of their patients’ spiritual needs can better understand them and provide more effective care. Increasing nurses’ awareness of their own spirituality can improve their attitudes toward death and help them deliver higher-quality care for dying patients and their families in both their personal and professional lives [3]. For this reason, the present study was designed and implemented to investigate nurses’ attitudes toward death and their understanding of spirituality and spiritual care.

Instrument and Methods

The present descriptive, analytical, and cross-sectional study was done on Iranian nurses working in five teaching hospitals in southeastern Iran (Kerman and Zahedan) in 2024-2025. After reviewing similar studies and using formulas to determine the sample size, 237 participants were included in the study. Sampling was conducted using a multi-stage method. In the first stage, a quota was assigned to each hospital based on the number of nurses in each facility. In the second stage, a list of all nurses in each hospital was prepared, and the desired sample was selected using systematic random sampling. The participants were selected from nurses working in different departments of the hospitals who had direct and continuous contact with patients.

Three questionnaires were utilized for data collection. The demographic information questionnaire focused on the demographic characteristics of the nurses.

The Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS) includes 23 questions divided into two main sections, including spirituality and spiritual care. The first section of this scale covers nine fundamental domains (indices) related to spirituality, including hope, meaning and purpose, forgiveness, beliefs and values, relationships, belief in God, ethics, innovation, and self-expression. This section comprises questions 3-6, 10, 11, 14-17, and 21-23 from the aforementioned instrument. The second section includes questions related to spiritual care and interventions that are deemed important in the literature, which encompass indicators, such as listening, spending time, respecting the patient’s privacy and dignity, maintaining religious practices, and providing care through expressions of kindness and attention. This section includes questions 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 18, 19, and 20. A five-point Likert scale was used for scoring, with the highest possible score being 92 and the lowest being zero. Scores ranging from 63 to 92 were considered high and desirable, scores from 32 to 62 were regarded as average and somewhat desirable, and scores from 0 to 31 were classified as low and undesirable. The validity and reliability of this scale have been previously investigated in a study by Mazaheri et al. [16]. To assess the content validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire, the opinions of faculty members were solicited. Thus, the instrument was provided to ten faculty members with various specialties related to the subject at the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. To determine the reliability of the scale, the test-retest method was employed [16].

To examine nurses’ attitudes toward death, the revised form of the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (DAP-R) was used. This scale was developed by Wang et al. It is a 32-item scale that assesses five dimensions of attitudes toward death, including fear of death, death avoidance, neutral acceptance (where the individual accepts the reality of death but does not consider it good or bad), active acceptance (where the individual accepts the reality of death but views it as a means to achieve happiness and well-being), and evasive acceptance (where the individual accepts the reality of death but sees it as a way to escape from life’s problems). These five dimensions reflect both positive (acceptance subscales) and negative (fear and avoidance subscales) attitudes toward death. Participants indicate their responses on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The scores for the questions related to each subscale are summed and divided by the number of questions to obtain the average score for that subscale, with higher scores indicating greater acceptance, fear, and avoidance of death. The validity and reliability of this scale have also been investigated in a study by Basharpoor et al. [17]. Wang et al. reported internal consistency reliability for these five subscales, ranging from 0.97 for the active acceptance subscale to 0.65 for the neutral acceptance subscale. The test-retest reliability of this scale after four weeks was also found to range from 0.61 for the acceptance subscale to 0.95 for the avoidance subscale [18].

In their study, the questionnaire was translated from English to Persian and back again by two individuals (the first author and a senior English language expert), and the content of the questions was confirmed. Its face validity was assessed by three psychologists with PhDs in psychology. Cronbach’s alpha was used to determine the reliability of the scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the subscales of this test ranged from 0.64 for the death avoidance subscale to 0.88 for the active acceptance of death subscale. The Cronbach’s alpha method was employed to assess the reliability of both tools.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22 software. Descriptive and inferential statistical tests were used to create tables and achieve the research objectives. After checking the normality of the data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, Pearson and Spearman correlation tests, t-tests, and ANOVA were utilized at a significance level of p<0.05.

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 31.15±2.57 years (with a minimum age of 23 and a maximum age of 54 years). Of the participants, 84% were female and 16% were male; 37.9% were single, 92% had no chronic illness, and 73% had never been hospitalized. Also, 72.1% of the participants had previously witnessed death, 60.3% had cared for dying patients, 27.3% felt regret and discomfort while providing care, 69.1% did not wish to care for dying patients, 30.1% claimed to be coping with death, and 75.1% felt incompetent in caring for dying patients. Additionally, 24.3% had received training about death, with 75% of those receiving it during their undergraduate years, and 84.71% considered the training to be insufficient.

Furthermore, 91.7% believed that special importance should be given to spiritual care for dying patients and their families, while 81.7% were unaware of spiritual care. Among those who knew about spiritual care, 34% learned about it during their undergraduate studies, and 89.1% thought that the education on spiritual care provided by universities was inadequate. Of the participants, 79.2% felt incompetent in caring for dying patients, and 89.2% felt they had not received sufficient training during their education and work on how to care for dying patients. Among the participants who had provided spiritual care, 45.2% stated that they had done so by talking to patients, while 44.62% of those who had never provided spiritual care indicated that they had not done so due to a lack of knowledge. The study of nurses’ attitudes toward death also revealed that the average score of nurses’ attitudes was 134.80±12.57 (Table 1).

Table 1. Average scores of attitudes to death according to demographic characteristics

Mean nurses' attitudes to death were also examined (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean nurses' "attitudes to death"

Nurses’ attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care fell within the high and desirable range. The average score of attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care among nurses was 84.59 (Table 3), with the majority of nurses (53.58%) scoring between 62 and 93.

Table 3. Mean nurses' attitudes to spirituality and spiritual care

There was no significant relationship between the mean scores of nurses’ attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care and demographic parameters (age, gender, marital status, academic semester, etc.; p≥0.005). Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficient demonstrated no significant relationship between the mean scores of nurses’ attitudes toward death and their attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care (p≥0.005).

Discussion

This study investigated nurses’ attitudes toward death and their understanding of spirituality and spiritual care. Nurses, regardless of where they work, encounter dead and dying patients; therefore, they must be trained on how to provide comprehensive care so that they can address not only the physical and psychological needs but also the social and spiritual needs of dying patients [3, 6]. The the attitude toward death among the majority of the research participants reflected an average to relatively favorable level, which is consistent with the findings of Hojjati et al. [18]. Şahin et al. and Çevik & Kav also found that more than half of nursing students and nurses do not wish to care for dying patients. Nurses who care for dying patients witness death firsthand, which forces them to confront their mortality while providing care for patients and their families [19, 20].

Nurses’ negative perceptions of death hindered them from providing effective and comprehensive care to dying patients [2, 3]. Çevik & Kav also demonstrated that Turkish nurses’ attitudes toward death and the care of dying patients are lower and more negative than those of nurses in other studies [19], which could be attributed to cultural differences [18], as the first step in accepting death is to view it as a natural process. Nurses who perceive death as the end of pain and suffering can cope with their emotions more easily. Furthermore, the mission of the nursing profession is to “keep patients alive” [3]. The variations in the results of studies examining the relationship between acceptance of death and attitudes toward caring for dying patients suggest that culture and religion can play significant roles in shaping these attitudes. Understanding the values and beliefs of healthcare providers can aid in the acceptance and comprehension of the meaning of death. Individuals who maintain positive attitudes toward death, actively accept it, view it as a pathway to eternal happiness, and recognize that death is not merely a technical or nonexistent event but a transition from one world to another—where human life continues in a different form—tend to experience better quality of life and mental health [17]. Factors, such as individual characteristics, experiences with death, education, beliefs, and the ability to discuss death may influence nurses’ attitudes toward caring for dying patients [21, 22]. A significant relationship was found between attitudes toward death and nurses’ work experience. As work experience increased, negative attitudes toward death decreased, which may be due to the experience and normalization of this issue, consistent with the findings of Hojjati et al. [18]. We also identified a significant relationship between attitudes toward death and education. Nurses who had completed training courses and workshops on caring for dying patients exhibited a more positive attitude toward death and a greater desire to care for dying patients compared to those who have not received training. This result aligns with the findings of Hojjati et al. [18]. Matsui et al. also concluded that better attitudes toward death and care for dying patients are positively related to attendance at educational seminars and negatively related to fear of death [23]. Additionally, Çevik & Kav found that there is a significant relationship between the desire to care for dying patients and attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients, indicating that a lack of experience and education leads to a negative attitude toward death, which is consistent with the results of the present study [19, 23]. The personal and professional experiences and attitudes of nurses toward death can significantly affect the care of dying patients [19]. Nurses’ attitudes toward death stem from their professional and personal lives and are influenced by various factors, such as age, religion, family circumstances, and previous experiences with death and illness. They should enhance their knowledge about death and stay informed about the latest developments so that they can effectively apply this knowledge in patient care [18].

The attitudes of Iranian nurses toward spirituality and spiritual care were higher than the median score, which suggests a high level of positive attitude among nurses regarding spirituality and spiritual care. Spirituality is one of the fundamental needs of humans, which some experts consider to encompass the highest levels of cognitive, moral, emotional, and personal development [1]. Since the nursing profession is grounded in maintaining the integrity of all aspects of patients and healthy individuals, and spirituality is one of those aspects, nurses are also responsible for providing spiritual care [12].

On the other hand, spiritual beliefs and practices are related to all aspects of a person’s life, including relationships with others, daily habits, and required behaviors [1]. Nurses who are aware of their patients’ spiritual needs understand them better and provide more effective care. Increasing nurses’ awareness of their spirituality can improve their attitudes toward death [3]. Our results are consistent with the findings of the studies by Babamohamadi et al. and Jafari et al. [24, 25]. However, it is inconsistent with the results of Shores [26] and McSherry & Jamieson [27]. Eğlence & Şimşek also demonstrated that more than half of the nurses report failing to meet the spiritual care needs of their patients [13]. There was no statistically significant relationship between other demographic parameters, such as marital status, gender, work experience, employment status, and attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care. This finding is consistent with the results of the study by Basharpoor et al. [17]. This difference can be explained by the fact that, in non-Islamic countries, spirituality may be independent of religious beliefs. However, in Iran and other Islamic countries, spirituality and religion are culturally integrated. In Iran, nurses consider spirituality to be an inseparable part of religion. The results of the present study also showed that there was a weak correlation between the SSCRS and DAP-R subscale scores. This result indicates that there is no relationship between the participants’ perception of spiritual care and their attitudes toward death; in other words, the participant’s perception of spirituality and spiritual care does not affect their attitudes toward death. This suggests that nurses’ attitudes toward death are influenced by factors other than spirituality and spiritual care. Our results are consistent with the findings of the study by Tüzer et al. [3].

It is recommended that spiritual health education be integrated into service areas and universities, dedicating a portion of the routine educational program for nurses in Iranian hospitals to spirituality and spiritual care. This approach aims to foster a more positive attitude among nursing staff. Additionally, creating an interactive environment where nurses can share their personal feelings about death and dying is encouraged, as it would help them incorporate aspects of death and spirituality into their care. The limitations of this study include the small number of participating nurses and its implementation in a restricted setting. To address these limitations, future research should assess spiritual care more broadly with a larger population and include comparisons between nurses from different hospitals and universities.

Conclusion

Education and work experience are effective in fostering a positive attitude among nurses toward death.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Vice Chancellor for Research at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences and the nursing department at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The project was approved by the institutional review board of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.028). When recruiting participants, the purpose of the study was clearly explained, and informed consent (both written and oral) was obtained. Participants were granted the right to decline or withdraw from the study at any time. They were assured of the confidentiality of all gathered data and informed that results would be shared with them upon request. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sarhadi M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (100%)

Funding/Support: No funding was received.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Spiritual Health

Received: 2025/03/29 | Accepted: 2025/05/17 | Published: 2025/05/21

Received: 2025/03/29 | Accepted: 2025/05/17 | Published: 2025/05/21

References

1. Ataiee N, Jajarmi M, Mehdian H. Investigating the relationship between attitude to death, God pattern, spiritual intelligence, perceived attachment, and social support with mental health mediation. Islam Life J. 2019;3(3):107-15. [Persian] [Link]

2. Sarhadi M. Analysis of the concept of death anxiety in nursing students: A qualitative study. Horiz Med Educ Dev. 2023;14(4):1-17. [Persian] [Link]

3. Tüzer H, Kırca K, Özveren H. Investigation of nursing students' attitudes towards death and their perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. J Relig Health. 2020;59(4):2177-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10943-020-01004-9]

4. Koku F, Ateş M. Experience and attitudes to death in nurses who give terminal stage patient care. Assoc Nurse Manag. 2016;3(2):99-104. [Link] [DOI:10.5222/SHYD.2016.099]

5. Lewinson LP, MsSherry W, Kevern P. Spirituality in pre-registration nurse education and practice: A review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(6):806-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2015.01.011]

6. İnce SC, Akhan LU. Nursing students' perceptions about spirituality and spiritual care. J Educ Res Nurs. 2016;13(3):202-8. [Link]

7. Abdollahyar A, Baniasadi H, Doustmohammadi MM, Sheikhbardesiri H, Yarmohammadian MH. Attitudes of Iranian nurses toward spirituality and spiritual care. J Christ Nurs. 2019;36(1):E11-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000581]

8. Ross L, McSherry W, Giske T, Van Leeuwen R, Schep-Akkerman A, Koslander T, et al. Nursing and midwifery students' perceptions of spirituality, spiritual care, and spiritual care competency: A prospective, longitudinal, correlational European study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;67:64-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2018.05.002]

9. Ripamonti CI, Giuntoli F, Gonella S, Miccinesi G. Spiritual care in cancer patients: A need or an option?. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30(4):212-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000454]

10. Hu Y, Jiao M, Li F. Effectiveness of spiritual care training to enhance spiritual health and spiritual care competency among oncology nurses. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):104. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12904-019-0489-3]

11. Mardani Hamooleh M, Seyedfatemi N, Eslami A, Haghani S. The spiritual care competency of the nurses of the teaching hospitals affiliated to Alborz university of medical sciences, Iran. Iran J Nurs. 2020;33(124):58-69. [Persian] [Link]

12. Çelik A, Özdemir F, Durmaz H, Pasinlioğlu T. Determining the perception level of nurses regarding spirituality and spiritual care and the factors that affect their perception level. J Hacet Univ Fac Nurs. 2014;1(3):1-12. [Turkish] [Link]

13. Eğlence R, Şimşek N. To determine the knowledge level about spiritual care and spirituality of nurses. J Acıbadem Univ Health Sci. 2014;5(1):48-53. [Turkish] [Link]

14. Guo Z, Zhang Y, Li P, Zhang Q, Shi C. Student nurses' spiritual care competence and attitude: An online survey. Nurs Open. 2023;10(3):1811-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nop2.1441]

15. Ghorbani M, Mohammadi E, Aghabozorgi R, Ramezani M. Spiritual care interventions in nursing: An integrative literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(3):1165-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-020-05747-9]

16. Mazaheri M, Fallahi Khoshknab M, Madah B, Rahgozar M. Nurses' attitude towards spirituality and spiritual care. PAYESH. 2009;8(1):31-7. [Persian] [Link]

17. Basharpoor S, Tayebeh Hoseinikiasari S, Soleymani E, Massah O. The role of irrational beliefs and attitudes to death in quality of life of the older people. SALMAND Iran J Ageing. 2019;14(3):260-71. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/sija.13.10.140]

18. Wong PT, Reker GT, Gesser G. Death Attitude Profile-Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. InDeath anxiety handbook: Research, instrumentation, and application. (pp. 121-148). London; Taylor & Francis; 2015. [Link]

19. Çevik B, Kav S. Attitudes and experiences of nurses toward death and caring for dying patients in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(6):58-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0b013e318276924c]

20. Şahin M, Demirkıran F, Adana F. Nursing students' death anxiety, influencing factors and request of caring for dying people. J Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;7(3):135-41. [Link] [DOI:10.5505/phd.2016.66588]

21. Karadağ E, İnkaya BV. The attitudes of nursing interns towards providing care for dying people. STED. 2018;27(2):92-8. [Turkish] [Link]

22. Zaybak A, Erzincanlı S. Attitudes of nurses towards death. Int Refereed J Nurs Res. 2016;6:16-29. [Link] [DOI:10.17371/UHD.2016616575]

23. Matsui M, Kanai E, Kitagawa A, Hattori K. Care managers' views on death and caring for older cancer patients in Japan. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19(12):606-11. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.12.606]

24. Babamohamadi H, Ahmadpanah MS, Ghorbani R. Attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care among Iranian nurses and nursing students: A cross-sectional study. J Relig Health. 2018;57(4):1304-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10943-017-0485-y]

25. Jafari M, Baneshi M, Borhani F, Sabzevari S. Nurses' and nursing students' views on spiritual care in Kerman Medical University. Med Ethics J. 2012;6(20):155-71. [Persian] [Link]

26. Shores CI. Spiritual perspectives of nursing students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2010;31(1):8-11. [Link]

27. McSherry W, Jamieson S. An online survey of nurses' perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(11-12):1757-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03547.x]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |