Volume 13, Issue 1 (2025)

Health Educ Health Promot 2025, 13(1): 21-30 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Raflizar R, Damris M, Johari A, Herlambang H. Community-Based Educational Approaches to Stunting Prevention. Health Educ Health Promot 2025; 13 (1) :21-30

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78430-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78430-en.html

1- Department of Postgraduate, Faculty of Mathematic & Science Program, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

2- Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science & Technology, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

3- Department of Biology Education, Faculty of Mathematic & Science Program, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

4- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

2- Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science & Technology, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

3- Department of Biology Education, Faculty of Mathematic & Science Program, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

4- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 832 kb]

(1671 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (825 Views)

Full-Text: (121 Views)

Introduction

Impaired growth and development caused by chronic malnutrition is known as stunting, which is a serious public health issue with long-term effects on both individuals and nations [1, 2]. Millions of children worldwide suffer from this condition, primarily in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to nutritious food, medical care, and sanitation facilities is limited [3-5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that early childhood stunting is associated with permanent cognitive impairments, poor academic performance, decreased adult productivity, and an increased risk of chronic illnesses [6]. Addressing stunting is essential for achieving global objectives such as the sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2.2, which aims to eradicate all forms of malnutrition by 2030 [7, 8].

Despite significant international efforts, reductions in stunting have not been uniformly achieved. The UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates indicate that while the global prevalence of stunting decreased from 33.1% in 2000 to 22.0% in 2020, regions such as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa continue to report stunting rates above 30% [9]. In Indonesia, the Studi Status Gizi Indonesia (SSGI) 2022 reported a national stunting prevalence of 21.6%, falling short of the government’s target to reduce it to 14% by 2024. These statistics underscore the urgent need for effective, scalable, and context-specific interventions [10].

One promising approach to stunting prevention is community-based education. Unlike top-down strategies, community-based education empowers local communities to become active participants in addressing stunting [11, 12]. These programs often incorporate culturally relevant messages, involve local stakeholders, and integrate educational sessions on maternal and child nutrition, hygiene, breastfeeding practices, and complementary feeding. The participatory nature of these approaches not only improves knowledge but also fosters behavior change, enabling sustainable improvements in child health outcomes [9, 12].

Several systematic reviews have explored interventions for stunting prevention, providing valuable insights into global efforts. For instance, a review by Bhutta et al. highlights the efficacy of nutrition-specific interventions, such as micronutrient supplementation and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) promotion, in reducing stunting [13, 14]. More recently, a meta-analysis by Lassi et al. [15] emphasizes the importance of integrating nutrition-sensitive approaches, such as poverty alleviation and education, to address the underlying determinants of stunting. However, these reviews often focus on broader interventions and do not specifically analyze the role of community-based education.

Another notable review by Bhutta et al. [16] synthesizes evidence on stunting reduction policies globally but lacks detailed insights into localized, community-driven educational programs. Similarly, systematic reviews of maternal and child health interventions have acknowledged the role of community health workers but often do not isolate educational components specifically tailored to stunting prevention [17]. This gap underscores the need for a focused examination of community-based education as both a standalone and synergistic strategy.

The present systematic review aimed to address this gap by synthesizing evidence from experimental studies on community-based education interventions targeting stunting prevention. It aimed to analyze their design, implementation, and effectiveness in diverse settings. By doing so, this review will contribute to understanding best practices, contextual factors influencing success, and critical areas for future research. This evidence is vital for policymakers, healthcare practitioners, and community leaders striving to develop sustainable and culturally sensitive strategies to combat stunting at the grassroots level. This review not only builds on previous findings but also adds specificity by narrowing its focus to community-based education approaches. By examining this critical aspect, the study aimed to provide actionable insights to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice in stunting prevention, ultimately contributing to healthier and more equitable communities.

Information and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 criteria to maintain openness and methodological rigor [18].

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were established using the PICOS framework (Table 1).

Table 1. PICOS statement

Information sources

To ensure comprehensive coverage, multiple sources of information were utilized. The electronic databases searched included PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Grey literature was explored through platforms, such as ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, WHO IRIS, Google Scholar, and reports from local ministries of health and international organizations, like UNICEF and FAO. Manual screening of references from included studies and relevant reviews was also conducted. The search encompassed studies published from the inception of the databases to December 2024.

Search strategy

For each database, a customized search strategy was created that combined free-text terms with controlled vocabulary, such as MeSH terms for PubMed and Emtree terms for Embase. To ensure the accurate retrieval of pertinent papers, the search was refined using Boolean operators and filters. Table 2 contains the full search strings for each database.

Table 2. Search terms in the databases

Study selection

Duplicate results were eliminated after importing all search results into reference management software. Two reviewers independently examined abstracts and titles to identify papers that met the inclusion criteria. Full-text publications of eligible studies were obtained and further evaluated for inclusion. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any disputes between the reviewers. A PRISMA flow diagram was used to document the selection process.

Data extraction

A standardized form, which was piloted and refined for this evaluation, was utilized to extract data. Extracted information included study characteristics, such as author, year, country, and design; population details including sample size; intervention specifics covering duration, content, and mode of delivery; comparator group details; outcomes measured, including primary and secondary outcomes; and key findings. Information on funding sources and potential conflicts of interest was also collected. Two reviewers independently extracted the data, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Risk of bias assessment

Validated instruments were employed to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Aspects such as randomization, departures from planned interventions, missing data, outcome assessment, and reporting bias were evaluated for RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) methodology. For quasi-experimental studies, confounding, selection bias, and deviations from intended interventions were assessed using the ROBINS-I (risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions) tool. Two reviewers conducted the assessments independently, and any disputes were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

Data synthesis

All included studies underwent a narrative synthesis with an emphasis on the features, methods, and results of the interventions.

Findings

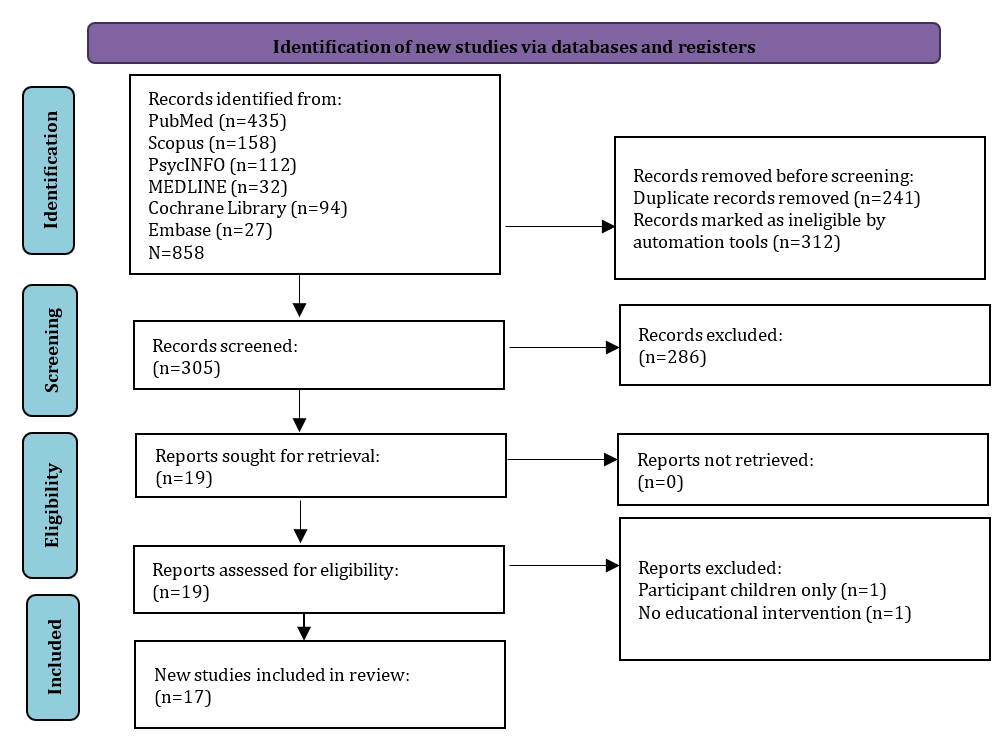

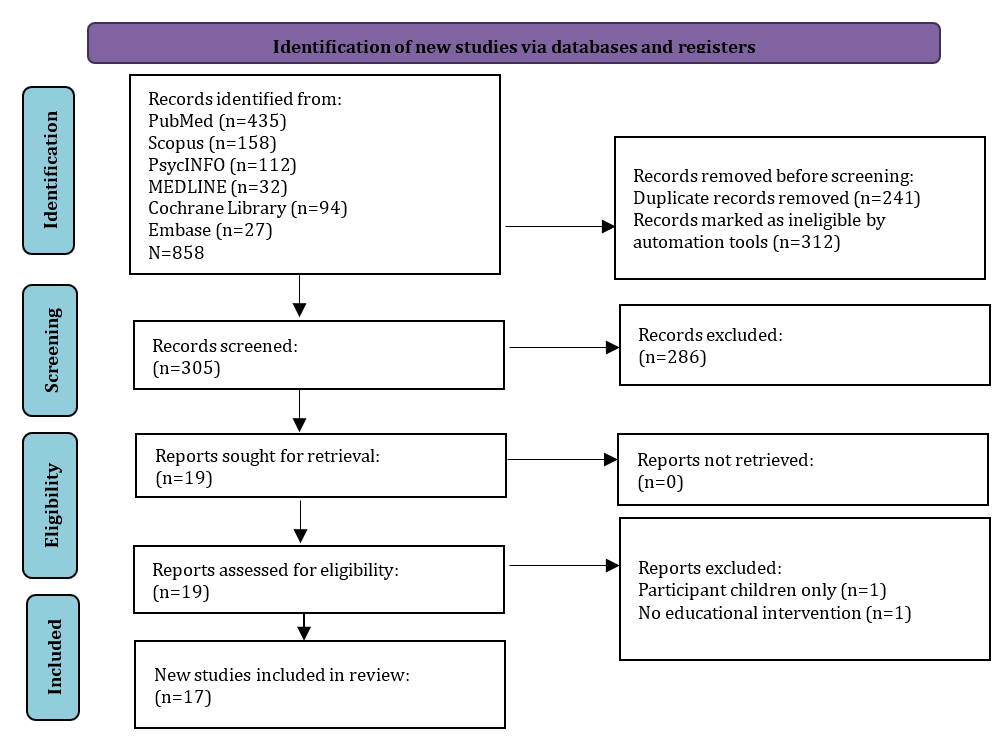

Database searches yielded a total of 858 publications, and a manual review of reference lists revealed no additional research. After eliminating 553 duplicates and irrelevant records, 305 studies were screened for titles and abstracts. Nineteen of these studies were selected for full-text review after 286 were disqualified for failing to meet the eligibility criteria. Following a comprehensive review, 17 studies remained for inclusion after nine were disqualified due to factors, such as the lack of a community-based educational component or irrelevant participant categories. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for study selection

Characteristics of the studies included

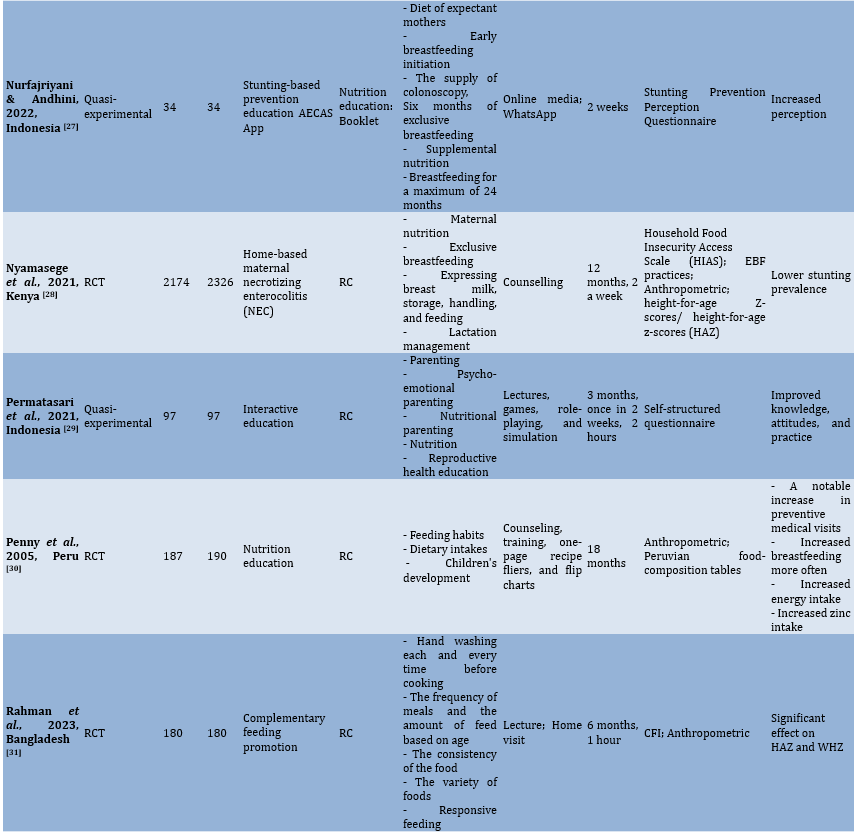

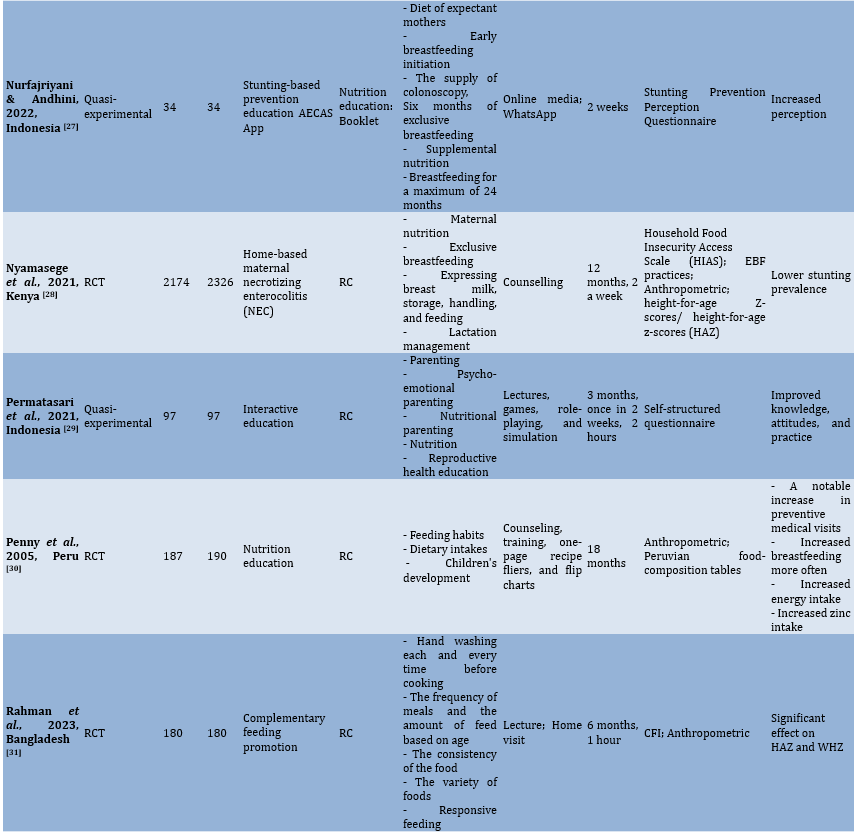

Seventeen studies from diverse LMICs, including Indonesia (n=8), Kenya (n=2), Bangladesh (n=4), Afghanistan (n=1), China (n=1), and Peru (n=1), were included (Table 3). The studies employed various designs, with randomized controlled trials (RCTs, n=10) and quasi-experimental designs (n=7). Sample sizes ranged from small, localized interventions (40 participants) to large-scale community-based programs (over 2,000 participants). The majority of the studies targeted caregivers, mothers, and pregnant women, focusing on improving nutrition-related practices to prevent stunting.

The duration of the interventions varied, from single sessions lasting 90 minutes to sustained multi-year programs. Delivery methods included home visits, group workshops, counseling sessions, mobile phone support, and digital platforms, often tailored to the cultural and contextual needs of the target population. The primary outcomes measured were improvements in height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) and reductions in stunting prevalence, while secondary outcomes included changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) related to maternal and child nutrition, hygiene, and feeding behaviors.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies included

Risk of bias assessment

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the ROBINS-I tool for quasi-experimental studies and the Cochrane RoB 2 tool for RCTs. Among the RCTs, six were deemed to be at low risk, while the remaining four raised some concerns due to incomplete blinding or issues with outcome data reporting. The quasi-experimental studies generally exhibited a moderate risk of bias, with common challenges including confounding variables, deviations from intended interventions, and reliance on self-reported outcomes (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Risk of bias visualization of randomized studies

Figure 3. Risk of bias visualization of non-randomized studies

Educational content delivered

All 17 studies incorporated community-based educational elements aimed at improving maternal and child nutrition behaviors.

Breastfeeding promotion: Twelve studies included EBF promotion, emphasizing early initiation, proper techniques, and the benefits of continued breastfeeding up to 24 months. For instance, mobile phone support in Bangladesh significantly increased EBF adherence rates (p<0.001), while a home-based program in Kenya led to a 25% improvement in EBF practices among urban mothers.

Complementary feeding guidance: Fourteen studies addressed complementary feeding practices, focusing on dietary diversity, meal frequency, and responsive feeding. Practical demonstrations, such as cooking classes in Indonesia, showed significant improvements in caregivers’ ability to prepare nutrient-rich meals, resulting in better dietary diversity scores (p<0.05).

Hygiene and sanitation: Nine studies integrated hygiene education, highlighting the importance of handwashing, clean food preparation, and sanitation to prevent infections that exacerbate malnutrition. A year-long intervention in Afghanistan reported a 40% improvement in hygiene practices among caregivers.

Behavioral change communication (BCC): Ten studies incorporated BCC strategies to modify caregiver attitudes and practices. A program in Bangladesh that used motivational messaging through WhatsApp enhanced maternal confidence and adherence to nutritional guidelines, improving complementary feeding practices (p<0.0001).

Delivery methods and intervention duration

Home visits: Utilized in six studies, home visits provided tailored counseling and direct support. For example, Kenyan community health workers conducting monthly home visits significantly improved exclusive breastfeeding rates and maternal nutritional literacy.

Group workshops and practical demonstrations: Five studies emphasized interactive learning, such as cooking classes and hygiene demonstrations. In Indonesia, group sessions led to a 20% increase in dietary diversity awareness among caregivers.

Digital Tools: Two studies used mobile apps and messaging platforms to deliver education, demonstrating significant behavioral improvements while reducing logistical barriers.

Duration

Intervention duration emerged as a critical factor influencing outcomes. Longer programs (12-24 months) consistently demonstrated greater effectiveness in reducing stunting prevalence and sustaining behavioral changes. For example, a two-year program in Afghanistan that combined educational sessions with nutritional supplementation reduced stunting prevalence by over 10% (p<0.001). Conversely, shorter interventions (e.g., a two-week online education program in Indonesia) were effective in raising awareness but had limited impact on long-term outcomes.

Impact on nutritional and behavioral outcomes

Primary outcomes: Improvements in HAZ were reported in 11 studies. Long-term interventions, such as an 18-month program in Peru, achieved substantial gains in child growth, with mean HAZ scores improving by 0.5 standard deviations (p<0.01). Similarly, a multi-year initiative in China observed a significant reduction in stunting prevalence, attributed to dietary counseling and complementary food provision (p<0.0001).

Secondary outcomes: Changes in caregiver KAP were observed in 15 studies. Enhanced dietary diversity scores, increased exclusive breastfeeding rates, and improved hygiene practices were notable achievements. A study in Bangladesh using mobile apps has reported a 40% increase in maternal perceptions and practices related to stunting prevention. Behavioral improvements are particularly pronounced in programs that employ culturally relevant materials and community-driven approaches.

Contextual and cultural adaptations

Cultural relevance was a key success factor in most studies. Programs that incorporated local foods, traditional recipes, and culturally familiar communication styles were more effective in engaging participants. For example, in Indonesia, community health cadres delivered educational sessions in local dialects, which increased caregiver participation and adherence.

Barriers and challenges in implementation

Logistical constraints: Challenges, such as limited resources, caregiver attendance, and time constraints impacted program effectiveness in six studies.

Scalability: While long-term, high-frequency programs were more effective, they posed challenges for scaling up in resource-constrained settings.

Caregiver resistance: Cultural norms and misconceptions occasionally hindered the adoption of recommended practices, emphasizing the need for culturally sensitive messaging.

Sustainability of educational outcomes

Few studies (n=3) assessed the long-term sustainability of outcomes. While initial improvements in KAP and growth indicators were promising, they often diminished without continued reinforcement. For example, a follow-up in Peru six months after the intervention showed retained dietary practices, but the gains in stunting reduction were less sustained.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of community-based educational interventions in preventing stunting. Evidence from 17 studies assessing the efficacy of community-based educational interventions in preventing stunting in LMICs is compiled in this systematic review. The findings underscore the critical role of culturally tailored, participatory educational programs in improving child growth outcomes and related maternal and caregiver behaviors. This discussion integrates insights from the reviewed studies with previous research, highlighting both alignments and contrasts to provide a nuanced understanding of their impact and limitations.

By improving HAZ and facilitating positive changes in KAP related to nutrition and hygiene, the review demonstrated that community-based educational interventions significantly contribute to the prevention of stunting. The observed improvements align with Bhutta et al. [16], demonstrating that nutrition education enhances dietary diversity and child growth outcomes when delivered through community-based approaches [13].

Interventions targeting EBF consistently showed strong outcomes. Studies in Bangladesh, Kenya, and Indonesia have highlighted substantial increases in EBF rates, reflecting the efficacy of BCC strategies. These findings mirror those of Kimani-Murage et al. [24], reporting significant improvements in breastfeeding following community-based interventions in urban Kenyan settlements [24].

In contrast, interventions of shorter duration or those limited to one-off sessions demonstrated less impact on stunting prevention. For example, a two-week program in Indonesia has shown modest improvements in dietary practices but no measurable changes in HAZ scores. This finding aligns with that of Bhutta et al. [16], emphasizing that sustained engagement is necessary to achieve meaningful outcomes in stunting reduction [16].

The review highlights the critical importance of delivery methods in determining the effectiveness of educational interventions. Multi-modal approaches (combining home visits, group workshops, and digital platforms) emerged as the most impactful. For instance, in Kenya, monthly home visits by community health workers (CHWs) have improved maternal nutrition literacy and EBF practices. Similarly, digital interventions, such as the WhatsApp-based program in Indonesia, have demonstrated significant improvements in caregiver perceptions and practices.

These findings align with that of Black et al. [36], noting that combining personal interactions with digital tools enhances engagement and adherence to recommended practices [36]. However, some studies have revealed that digital tools alone may not suffice in resource-poor settings, where Internet access and digital literacy are limited. This contrasts with Morgan et al. [37], advocating for mHealth tools as scalable solutions in LMICs but acknowledging their dependence on enabling infrastructure [37].

Behavior change was a central outcome across the studies, with interventions driving significant improvements in maternal and caregiver practices. In particular, BCC techniques, such as motivational counseling, role-playing, and practical demonstrations effectively facilitated behavioral shifts. Similar findings are reported by Dewey & Adu-Afarwuah [38], highlighting the transformative potential of participatory education in complementary feeding programs [38].

Nevertheless, sustaining these changes remains a challenge. This review found that gains in caregiver behaviors, such as dietary diversity and hygiene practices, often diminished without continued reinforcement. A similar observation was made by Wallace et al. [39], emphasizing the importance of follow-up sessions to consolidate learning and sustain behavior change [39].

Cultural relevance was a key success factor in the interventions reviewed. Programs that incorporated local traditions, foods, and communication styles achieved higher participation and greater adherence to recommendations. For instance, interventions in Indonesia have employed traditional recipes and engaged local cadres, significantly improving caregiver practices. These findings align with those of Pelto & Armar‐Klemesu [40], emphasizing the importance of culturally grounded approaches in nutrition education programs [40].

In contrast, interventions that failed to consider local norms faced resistance. For example, a study in Afghanistan has noted initial caregiver hesitance to adopt new breastfeeding practices due to misconceptions and traditional beliefs. Wulandari et al. [41] similarly found that culturally insensitive programs often struggle to achieve behavioral change in rural Asian communities [41].

Despite their successes, educational interventions face several challenges. Logistical constraints, such as inconsistent caregiver attendance and resource limitations, are common. Rural programs, in particular, have struggled to maintain consistent participation due to caregivers’ time constraints and limited transportation. This finding aligns with that of Lassi et al. [15], highlighting similar barriers to implementing maternal and child health programs in LMICs [15].

Additionally, socio-cultural barriers, such as deeply rooted norms and gender dynamics, occasionally hindered the adoption of recommended practices. Adair et al. [42] have reported similar challenges, noting that patriarchal structures often limit women’s decision-making autonomy, affecting their ability to implement nutritional recommendations [42].

This review underscores the standalone potential of education in improving KAP and stunting-related outcomes. However, the findings suggest that its impact can be amplified when combined with broader nutrition-sensitive strategies. According to Little et al. [43], integrating education with cash transfers or food supplementation accelerates stunting reduction, providing a more holistic approach to addressing malnutrition [43].

Conversely, this review also highlights the limitations of education-focused interventions, particularly in addressing the underlying structural determinants of stunting, such as poverty and food insecurity. Victora et al. [44] similarly have emphasized the need for multi-sectoral strategies that tackle the root causes of malnutrition alongside direct interventions [45].

The findings offer several key implications for policy and practice. Long-term programs with frequent sessions are essential for achieving lasting behavioral and growth-related improvements. Interventions must be designed to align with local traditions, norms, and dietary practices to enhance their relevance and effectiveness. Additionally, education programs should be integrated with broader development initiatives, such as social protection schemes, to address the structural determinants of stunting. Finally, digital tools, such as mobile apps, can complement traditional methods to expand reach and cost efficiency, particularly in urban settings. Community-based educational interventions are a powerful tool for stunting prevention, demonstrating significant impacts on growth and behavioral outcomes. Their success hinges on cultural relevance, participatory delivery, and sustained engagement. However, addressing logistical challenges and integrating these programs into broader multi-sectoral frameworks is essential for achieving scalable and sustainable solutions.

Conclusion

Community-based educational interventions effectively reduce stunting and improve nutrition-related behaviors in LMICs.

Acknowledgments: We would like to express our gratitude to the Head of Jambi University for providing material support in the implementation of this study.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Raflizar R (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Damris M (Second Author), Assistance Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Johari A (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistance Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Herlambang H (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistance Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: We did not receive any financial support from any party.

Impaired growth and development caused by chronic malnutrition is known as stunting, which is a serious public health issue with long-term effects on both individuals and nations [1, 2]. Millions of children worldwide suffer from this condition, primarily in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to nutritious food, medical care, and sanitation facilities is limited [3-5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that early childhood stunting is associated with permanent cognitive impairments, poor academic performance, decreased adult productivity, and an increased risk of chronic illnesses [6]. Addressing stunting is essential for achieving global objectives such as the sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2.2, which aims to eradicate all forms of malnutrition by 2030 [7, 8].

Despite significant international efforts, reductions in stunting have not been uniformly achieved. The UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates indicate that while the global prevalence of stunting decreased from 33.1% in 2000 to 22.0% in 2020, regions such as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa continue to report stunting rates above 30% [9]. In Indonesia, the Studi Status Gizi Indonesia (SSGI) 2022 reported a national stunting prevalence of 21.6%, falling short of the government’s target to reduce it to 14% by 2024. These statistics underscore the urgent need for effective, scalable, and context-specific interventions [10].

One promising approach to stunting prevention is community-based education. Unlike top-down strategies, community-based education empowers local communities to become active participants in addressing stunting [11, 12]. These programs often incorporate culturally relevant messages, involve local stakeholders, and integrate educational sessions on maternal and child nutrition, hygiene, breastfeeding practices, and complementary feeding. The participatory nature of these approaches not only improves knowledge but also fosters behavior change, enabling sustainable improvements in child health outcomes [9, 12].

Several systematic reviews have explored interventions for stunting prevention, providing valuable insights into global efforts. For instance, a review by Bhutta et al. highlights the efficacy of nutrition-specific interventions, such as micronutrient supplementation and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) promotion, in reducing stunting [13, 14]. More recently, a meta-analysis by Lassi et al. [15] emphasizes the importance of integrating nutrition-sensitive approaches, such as poverty alleviation and education, to address the underlying determinants of stunting. However, these reviews often focus on broader interventions and do not specifically analyze the role of community-based education.

Another notable review by Bhutta et al. [16] synthesizes evidence on stunting reduction policies globally but lacks detailed insights into localized, community-driven educational programs. Similarly, systematic reviews of maternal and child health interventions have acknowledged the role of community health workers but often do not isolate educational components specifically tailored to stunting prevention [17]. This gap underscores the need for a focused examination of community-based education as both a standalone and synergistic strategy.

The present systematic review aimed to address this gap by synthesizing evidence from experimental studies on community-based education interventions targeting stunting prevention. It aimed to analyze their design, implementation, and effectiveness in diverse settings. By doing so, this review will contribute to understanding best practices, contextual factors influencing success, and critical areas for future research. This evidence is vital for policymakers, healthcare practitioners, and community leaders striving to develop sustainable and culturally sensitive strategies to combat stunting at the grassroots level. This review not only builds on previous findings but also adds specificity by narrowing its focus to community-based education approaches. By examining this critical aspect, the study aimed to provide actionable insights to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice in stunting prevention, ultimately contributing to healthier and more equitable communities.

Information and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 criteria to maintain openness and methodological rigor [18].

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were established using the PICOS framework (Table 1).

Table 1. PICOS statement

Information sources

To ensure comprehensive coverage, multiple sources of information were utilized. The electronic databases searched included PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Grey literature was explored through platforms, such as ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, WHO IRIS, Google Scholar, and reports from local ministries of health and international organizations, like UNICEF and FAO. Manual screening of references from included studies and relevant reviews was also conducted. The search encompassed studies published from the inception of the databases to December 2024.

Search strategy

For each database, a customized search strategy was created that combined free-text terms with controlled vocabulary, such as MeSH terms for PubMed and Emtree terms for Embase. To ensure the accurate retrieval of pertinent papers, the search was refined using Boolean operators and filters. Table 2 contains the full search strings for each database.

Table 2. Search terms in the databases

Study selection

Duplicate results were eliminated after importing all search results into reference management software. Two reviewers independently examined abstracts and titles to identify papers that met the inclusion criteria. Full-text publications of eligible studies were obtained and further evaluated for inclusion. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any disputes between the reviewers. A PRISMA flow diagram was used to document the selection process.

Data extraction

A standardized form, which was piloted and refined for this evaluation, was utilized to extract data. Extracted information included study characteristics, such as author, year, country, and design; population details including sample size; intervention specifics covering duration, content, and mode of delivery; comparator group details; outcomes measured, including primary and secondary outcomes; and key findings. Information on funding sources and potential conflicts of interest was also collected. Two reviewers independently extracted the data, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Risk of bias assessment

Validated instruments were employed to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Aspects such as randomization, departures from planned interventions, missing data, outcome assessment, and reporting bias were evaluated for RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) methodology. For quasi-experimental studies, confounding, selection bias, and deviations from intended interventions were assessed using the ROBINS-I (risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions) tool. Two reviewers conducted the assessments independently, and any disputes were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

Data synthesis

All included studies underwent a narrative synthesis with an emphasis on the features, methods, and results of the interventions.

Findings

Database searches yielded a total of 858 publications, and a manual review of reference lists revealed no additional research. After eliminating 553 duplicates and irrelevant records, 305 studies were screened for titles and abstracts. Nineteen of these studies were selected for full-text review after 286 were disqualified for failing to meet the eligibility criteria. Following a comprehensive review, 17 studies remained for inclusion after nine were disqualified due to factors, such as the lack of a community-based educational component or irrelevant participant categories. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for study selection

Characteristics of the studies included

Seventeen studies from diverse LMICs, including Indonesia (n=8), Kenya (n=2), Bangladesh (n=4), Afghanistan (n=1), China (n=1), and Peru (n=1), were included (Table 3). The studies employed various designs, with randomized controlled trials (RCTs, n=10) and quasi-experimental designs (n=7). Sample sizes ranged from small, localized interventions (40 participants) to large-scale community-based programs (over 2,000 participants). The majority of the studies targeted caregivers, mothers, and pregnant women, focusing on improving nutrition-related practices to prevent stunting.

The duration of the interventions varied, from single sessions lasting 90 minutes to sustained multi-year programs. Delivery methods included home visits, group workshops, counseling sessions, mobile phone support, and digital platforms, often tailored to the cultural and contextual needs of the target population. The primary outcomes measured were improvements in height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) and reductions in stunting prevalence, while secondary outcomes included changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) related to maternal and child nutrition, hygiene, and feeding behaviors.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies included

Risk of bias assessment

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the ROBINS-I tool for quasi-experimental studies and the Cochrane RoB 2 tool for RCTs. Among the RCTs, six were deemed to be at low risk, while the remaining four raised some concerns due to incomplete blinding or issues with outcome data reporting. The quasi-experimental studies generally exhibited a moderate risk of bias, with common challenges including confounding variables, deviations from intended interventions, and reliance on self-reported outcomes (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Risk of bias visualization of randomized studies

Figure 3. Risk of bias visualization of non-randomized studies

Educational content delivered

All 17 studies incorporated community-based educational elements aimed at improving maternal and child nutrition behaviors.

Breastfeeding promotion: Twelve studies included EBF promotion, emphasizing early initiation, proper techniques, and the benefits of continued breastfeeding up to 24 months. For instance, mobile phone support in Bangladesh significantly increased EBF adherence rates (p<0.001), while a home-based program in Kenya led to a 25% improvement in EBF practices among urban mothers.

Complementary feeding guidance: Fourteen studies addressed complementary feeding practices, focusing on dietary diversity, meal frequency, and responsive feeding. Practical demonstrations, such as cooking classes in Indonesia, showed significant improvements in caregivers’ ability to prepare nutrient-rich meals, resulting in better dietary diversity scores (p<0.05).

Hygiene and sanitation: Nine studies integrated hygiene education, highlighting the importance of handwashing, clean food preparation, and sanitation to prevent infections that exacerbate malnutrition. A year-long intervention in Afghanistan reported a 40% improvement in hygiene practices among caregivers.

Behavioral change communication (BCC): Ten studies incorporated BCC strategies to modify caregiver attitudes and practices. A program in Bangladesh that used motivational messaging through WhatsApp enhanced maternal confidence and adherence to nutritional guidelines, improving complementary feeding practices (p<0.0001).

Delivery methods and intervention duration

Home visits: Utilized in six studies, home visits provided tailored counseling and direct support. For example, Kenyan community health workers conducting monthly home visits significantly improved exclusive breastfeeding rates and maternal nutritional literacy.

Group workshops and practical demonstrations: Five studies emphasized interactive learning, such as cooking classes and hygiene demonstrations. In Indonesia, group sessions led to a 20% increase in dietary diversity awareness among caregivers.

Digital Tools: Two studies used mobile apps and messaging platforms to deliver education, demonstrating significant behavioral improvements while reducing logistical barriers.

Duration

Intervention duration emerged as a critical factor influencing outcomes. Longer programs (12-24 months) consistently demonstrated greater effectiveness in reducing stunting prevalence and sustaining behavioral changes. For example, a two-year program in Afghanistan that combined educational sessions with nutritional supplementation reduced stunting prevalence by over 10% (p<0.001). Conversely, shorter interventions (e.g., a two-week online education program in Indonesia) were effective in raising awareness but had limited impact on long-term outcomes.

Impact on nutritional and behavioral outcomes

Primary outcomes: Improvements in HAZ were reported in 11 studies. Long-term interventions, such as an 18-month program in Peru, achieved substantial gains in child growth, with mean HAZ scores improving by 0.5 standard deviations (p<0.01). Similarly, a multi-year initiative in China observed a significant reduction in stunting prevalence, attributed to dietary counseling and complementary food provision (p<0.0001).

Secondary outcomes: Changes in caregiver KAP were observed in 15 studies. Enhanced dietary diversity scores, increased exclusive breastfeeding rates, and improved hygiene practices were notable achievements. A study in Bangladesh using mobile apps has reported a 40% increase in maternal perceptions and practices related to stunting prevention. Behavioral improvements are particularly pronounced in programs that employ culturally relevant materials and community-driven approaches.

Contextual and cultural adaptations

Cultural relevance was a key success factor in most studies. Programs that incorporated local foods, traditional recipes, and culturally familiar communication styles were more effective in engaging participants. For example, in Indonesia, community health cadres delivered educational sessions in local dialects, which increased caregiver participation and adherence.

Barriers and challenges in implementation

Logistical constraints: Challenges, such as limited resources, caregiver attendance, and time constraints impacted program effectiveness in six studies.

Scalability: While long-term, high-frequency programs were more effective, they posed challenges for scaling up in resource-constrained settings.

Caregiver resistance: Cultural norms and misconceptions occasionally hindered the adoption of recommended practices, emphasizing the need for culturally sensitive messaging.

Sustainability of educational outcomes

Few studies (n=3) assessed the long-term sustainability of outcomes. While initial improvements in KAP and growth indicators were promising, they often diminished without continued reinforcement. For example, a follow-up in Peru six months after the intervention showed retained dietary practices, but the gains in stunting reduction were less sustained.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of community-based educational interventions in preventing stunting. Evidence from 17 studies assessing the efficacy of community-based educational interventions in preventing stunting in LMICs is compiled in this systematic review. The findings underscore the critical role of culturally tailored, participatory educational programs in improving child growth outcomes and related maternal and caregiver behaviors. This discussion integrates insights from the reviewed studies with previous research, highlighting both alignments and contrasts to provide a nuanced understanding of their impact and limitations.

By improving HAZ and facilitating positive changes in KAP related to nutrition and hygiene, the review demonstrated that community-based educational interventions significantly contribute to the prevention of stunting. The observed improvements align with Bhutta et al. [16], demonstrating that nutrition education enhances dietary diversity and child growth outcomes when delivered through community-based approaches [13].

Interventions targeting EBF consistently showed strong outcomes. Studies in Bangladesh, Kenya, and Indonesia have highlighted substantial increases in EBF rates, reflecting the efficacy of BCC strategies. These findings mirror those of Kimani-Murage et al. [24], reporting significant improvements in breastfeeding following community-based interventions in urban Kenyan settlements [24].

In contrast, interventions of shorter duration or those limited to one-off sessions demonstrated less impact on stunting prevention. For example, a two-week program in Indonesia has shown modest improvements in dietary practices but no measurable changes in HAZ scores. This finding aligns with that of Bhutta et al. [16], emphasizing that sustained engagement is necessary to achieve meaningful outcomes in stunting reduction [16].

The review highlights the critical importance of delivery methods in determining the effectiveness of educational interventions. Multi-modal approaches (combining home visits, group workshops, and digital platforms) emerged as the most impactful. For instance, in Kenya, monthly home visits by community health workers (CHWs) have improved maternal nutrition literacy and EBF practices. Similarly, digital interventions, such as the WhatsApp-based program in Indonesia, have demonstrated significant improvements in caregiver perceptions and practices.

These findings align with that of Black et al. [36], noting that combining personal interactions with digital tools enhances engagement and adherence to recommended practices [36]. However, some studies have revealed that digital tools alone may not suffice in resource-poor settings, where Internet access and digital literacy are limited. This contrasts with Morgan et al. [37], advocating for mHealth tools as scalable solutions in LMICs but acknowledging their dependence on enabling infrastructure [37].

Behavior change was a central outcome across the studies, with interventions driving significant improvements in maternal and caregiver practices. In particular, BCC techniques, such as motivational counseling, role-playing, and practical demonstrations effectively facilitated behavioral shifts. Similar findings are reported by Dewey & Adu-Afarwuah [38], highlighting the transformative potential of participatory education in complementary feeding programs [38].

Nevertheless, sustaining these changes remains a challenge. This review found that gains in caregiver behaviors, such as dietary diversity and hygiene practices, often diminished without continued reinforcement. A similar observation was made by Wallace et al. [39], emphasizing the importance of follow-up sessions to consolidate learning and sustain behavior change [39].

Cultural relevance was a key success factor in the interventions reviewed. Programs that incorporated local traditions, foods, and communication styles achieved higher participation and greater adherence to recommendations. For instance, interventions in Indonesia have employed traditional recipes and engaged local cadres, significantly improving caregiver practices. These findings align with those of Pelto & Armar‐Klemesu [40], emphasizing the importance of culturally grounded approaches in nutrition education programs [40].

In contrast, interventions that failed to consider local norms faced resistance. For example, a study in Afghanistan has noted initial caregiver hesitance to adopt new breastfeeding practices due to misconceptions and traditional beliefs. Wulandari et al. [41] similarly found that culturally insensitive programs often struggle to achieve behavioral change in rural Asian communities [41].

Despite their successes, educational interventions face several challenges. Logistical constraints, such as inconsistent caregiver attendance and resource limitations, are common. Rural programs, in particular, have struggled to maintain consistent participation due to caregivers’ time constraints and limited transportation. This finding aligns with that of Lassi et al. [15], highlighting similar barriers to implementing maternal and child health programs in LMICs [15].

Additionally, socio-cultural barriers, such as deeply rooted norms and gender dynamics, occasionally hindered the adoption of recommended practices. Adair et al. [42] have reported similar challenges, noting that patriarchal structures often limit women’s decision-making autonomy, affecting their ability to implement nutritional recommendations [42].

This review underscores the standalone potential of education in improving KAP and stunting-related outcomes. However, the findings suggest that its impact can be amplified when combined with broader nutrition-sensitive strategies. According to Little et al. [43], integrating education with cash transfers or food supplementation accelerates stunting reduction, providing a more holistic approach to addressing malnutrition [43].

Conversely, this review also highlights the limitations of education-focused interventions, particularly in addressing the underlying structural determinants of stunting, such as poverty and food insecurity. Victora et al. [44] similarly have emphasized the need for multi-sectoral strategies that tackle the root causes of malnutrition alongside direct interventions [45].

The findings offer several key implications for policy and practice. Long-term programs with frequent sessions are essential for achieving lasting behavioral and growth-related improvements. Interventions must be designed to align with local traditions, norms, and dietary practices to enhance their relevance and effectiveness. Additionally, education programs should be integrated with broader development initiatives, such as social protection schemes, to address the structural determinants of stunting. Finally, digital tools, such as mobile apps, can complement traditional methods to expand reach and cost efficiency, particularly in urban settings. Community-based educational interventions are a powerful tool for stunting prevention, demonstrating significant impacts on growth and behavioral outcomes. Their success hinges on cultural relevance, participatory delivery, and sustained engagement. However, addressing logistical challenges and integrating these programs into broader multi-sectoral frameworks is essential for achieving scalable and sustainable solutions.

Conclusion

Community-based educational interventions effectively reduce stunting and improve nutrition-related behaviors in LMICs.

Acknowledgments: We would like to express our gratitude to the Head of Jambi University for providing material support in the implementation of this study.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Raflizar R (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Damris M (Second Author), Assistance Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Johari A (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistance Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Herlambang H (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Assistance Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: We did not receive any financial support from any party.

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2024/12/5 | Accepted: 2025/01/8 | Published: 2025/01/26

Received: 2024/12/5 | Accepted: 2025/01/8 | Published: 2025/01/26

References

1. Scheffler C, Hermanussen M, Bogin B, Liana DS, Taolin F, Cempaka P, et al. Stunting is not a synonym of malnutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74(3):377-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41430-019-0439-4]

2. Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Alaaraj N, Ahmed S, Alyafei F, Hamed N, et al. Early and long-term consequences of nutritional stunting: from childhood to adulthood. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(1):e2021168. [Link]

3. Mertens A, Benjamin-Chung J, Colford Jr JM, Hubbard AE, Van Der Laan MJ, Coyle J, et al. Child wasting and concurrent stunting in low-and middle-income countries. Nature. 2023;621(7979):558-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41586-023-06480-z]

4. Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Ba DM, Ericson JE, Na M, Gao X, et al. Global, regional and national epidemiology and prevalence of child stunting, wasting and underweight in low-and middle-income countries, 2006-2018. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5204. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-84302-w]

5. Karlsson O, Kim R, Moloney GM, Hasman A, Subramanian SV. Patterns in child stunting by age: A cross‐sectional study of 94 low‐and middle‐income countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2023;19(4):e13537. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/mcn.13537]

6. Mwene-Batu P, Bisimwa G, Baguma M, Chabwine J, Bapolisi A, Chimanuka C, et al. Long-term effects of severe acute malnutrition during childhood on adult cognitive, academic and behavioural development in African fragile countries: The Lwiro cohort study in Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244486. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0244486]

7. Komarulzaman A, Andoyo R, Anna Z, Ghina AA, Halim PR, Napitupulu H, et al. Achieving zero stunting: A sustainable development goal interlinkage approach at district level. Sustainability. 2023;15(11):8890. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/su15118890]

8. Grosso G, Mateo A, Rangelov N, Buzeti T, Birt C. Nutrition in the context of the sustainable development goals. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(Suppl 1):i19-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa034]

9. WHO. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: Key findings of the 2020 edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

10. Erwani E, Susanti D, Doni AW, Yuda RA, Yanti M. Determining the role of exclusive breastfeeding and nutritional status in stunting prevention: A literature review. POLTEKITA: JURNAL ILMU KESEHATAN. 2023;17(3):1014-25. [Link] [DOI:10.33860/jik.v17i3.2805]

11. Hamindo SJ, Adiyatma FN, Ramadhan RN, Alfina AID, Ananta SM, Zakiya NZ, et al. Community service initiative: Empowering mothers in Wongsorejo, Banyuwangi, East Java to prevent stunting through education and complementary feeding circle demonstrations. World J Adv Res Rev. 2024;23(3):1814-20. [Link] [DOI:10.30574/wjarr.2024.23.3.2809]

12. Parasila N, Sjamsuddin S, Nuh M. Stunting prevention education through the stunting reduction acceleration program at the women's empowerment, child protection, population control and family planning office of tana Toraja district. Erudio J Educ Innov. 2024;11(2):144-57. [Link]

13. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost?. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):452-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4]

14. Bhutta ZA, Salam RA. Global nutrition epidemiology and trends. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;61(Suppl 1):19-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000345167]

15. Lassi ZS, Rind F, Irfan O, Hadi R, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Impact of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) nutrition interventions on breastfeeding practices, growth and mortality in low-and middle-income countries: Systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):722. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu12030722]

16. Bhutta ZA, Akseer N, Keats EC, Vaivada T, Baker S, Horton SE, et al. How countries can reduce child stunting at scale: Lessons from exemplar countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(Suppl 2):894S-904S. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa153]

17. Gebremeskel AT, Omonaiye O, Yaya S. Multilevel determinants of community health workers for an effective maternal and child health programme in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(4):e008162. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008162]

18. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.n71]

19. Effendy DS, Prangthip P, Soonthornworasiri N, Winichagoon P, Kwanbunjan K. Nutrition education in Southeast Sulawesi Province, Indonesia: A cluster randomized controlled study. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16(4):e13030. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/mcn.13030]

20. Akter SM, Roy SK, Thakur SK, Sultana M, Khatun W, Rahman R, et al. Effects of third trimester counseling on pregnancy weight gain, birthweight, and breastfeeding among urban poor women in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2012;33(3):194-201. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/156482651203300304]

21. Dearden K, Mulokozi G, Linehan M, Cherian D, Torres S, West J, et al. The impact of a large-scale social and behavior change communication intervention in the lake zone region of Tanzania on knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to stunting prevention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1214. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20021214]

22. Jahan K, Roy SK, Mihrshahi S, Sultana N, Khatoon S, Roy H, et al. Short-term nutrition education reduces low birthweight and improves pregnancy outcomes among urban poor women in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2014;35(4):414-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/156482651403500403]

23. Jerin I, Akter M, Talukder K, Talukder MQEK, Rahman MA. Mobile phone support to sustain exclusive breastfeeding in the community after hospital delivery and counseling: A quasi-experimental study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):14. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13006-020-00258-z]

24. Kimani-Murage EW, Griffiths PL, Wekesah FM, Wanjohi M, Muhia N, Muriuki P, et al. Effectiveness of home-based nutritional counselling and support on exclusive breastfeeding in urban poor settings in Nairobi: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Glob Health. 2017;13(1):90. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12992-017-0314-9]

25. Maryati S, Yunitasari P, Punjastuti B. The effect of interactive education program in preventing stunting for mothers with children under 5 years of age in Indonesia: A randomized controlled trial. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2022;10(G):260-4. [Link] [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2022.7944]

26. Muhamad Z, Mahmudiono T, Abihail CT, Sahila N, Wangi MP, Suyanto B, et al. Preliminary study: The effectiveness of nutrition education intervention targeting short-statured pregnant women to prevent gestational stunting. Nutrients. 2023;15(19):4305. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu15194305]

27. Nurfajriyani I, Andhini CSD. The effectiveness of educational applications to prevent stunting children (AECAS) on perceptions of stunting prevention. Bp Int Res Critics Inst J. 2022;5(4):29069-76. [Link]

28. Nyamasege CK, Kimani-Murage EW, Wanjohi M, Kaindi DWM, Wagatsuma Y. Effect of maternal nutritional education and counselling on children's stunting prevalence in urban informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(12):3740-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1368980020001962]

29. Permatasari TAE, Rizqiya F, Kusumaningati W, Suryaalamsah II, Hermiwahyoeni Z. The effect of nutrition and reproductive health education of pregnant women in Indonesia using quasi experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):180. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-03676-x]

30. Penny ME, Creed-Kanashiro HM, Robert RC, Narro R, Caulfield LE, Black RE. Effectiveness of an educational intervention delivered through the health services to improve nutrition in young children: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9474):1863-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66426-4]

31. Rahman MJ, Rahman MM, Kakehashi M, Matsuyama R, Sarker MHR, Ali M, et al. Impact of eHealth education to reduce anemia among school-going adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2023;12(11):2569-75. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1010_23]

32. Sari GM. Early stunting detection education as an effort to increase mother's knowledge about stunting prevention. FOLIA MEDICA INDONESIANA. 2021;57(1):70-5. [Link] [DOI:10.20473/fmi.v57i1.23388]

33. Sirajuddin S, Razak A, Thaha RM, Sudargo T. The intervention of maternal nutrition literacy has the potential to prevent childhood stunting: Randomized control trials. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(2):2235. [Link] [DOI:10.4081/jphr.2021.2235]

34. Soofi SB, Khan GN, Sajid M, Hussainyar MA, Shams S, Shaikh M, et al. Specialized nutritious foods and behavior change communication interventions during the first 1000 d of life to prevent stunting: A quasi-experimental study in Afghanistan. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;120(3):560-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajcnut.2024.07.007]

35. Zhang Y, Wu Q, Wang W, Van Velthoven MH, Chang S, Han H, et al. Effectiveness of complementary food supplements and dietary counselling on anaemia and stunting in children aged 6-23 months in poor areas of Qinghai Province, China: A controlled interventional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e011234. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011234]

36. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X]

37. Morgan B, Hunt X, Tomlinson M. Thinking about the environment and theorising change: How could life history strategy theory inform mHealth interventions in low-and middle-income countries?. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1320118. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/16549716.2017.1320118]

38. Dewey KG, Adu‐Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4(Suppl 1):24-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00124.x]

39. Wallace R, Lo J, Devine A. Tailored nutrition education in the elderly can lead to sustained dietary behaviour change. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(1):8-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12603-016-0669-2]

40. Pelto GH, Armar‐Klemesu M. Balancing nurturance, cost and time: Complementary feeding in Accra, Ghana. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(Suppl 3):66-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00351.x]

41. Wulandari RD, Laksono AD, Rohmah N. Urban-rural disparities of antenatal care in South East Asia: A case study in the Philippines and Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1221. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-11318-2]

42. Adair LS, Fall CHD, Osmond C, Stein AD, Martorell R, Ramirez-Zea M, et al. Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with adult health and human capital in countries of low and middle income: Findings from five birth cohort studies. Lancet. 2013;382(9891):525-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60103-8]

43. Little MT, Roelen K, Lange BCL, Steinert JI, Yakubovich AR, Cluver L, et al. Effectiveness of cash-plus programmes on early childhood outcomes compared to cash transfers alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2021;18(9):e1003698. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003698]

44. Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371(9609):340-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4]

45. Tirado MC, Vivero-Pol JL, Bezner Kerr R, Krishnamurthy K. Feasibility and effectiveness assessment of multi-sectoral climate change adaptation for food security and nutrition. Curr Clim Change Rep. 2022;8(2):35-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40641-022-00181-x]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |