Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 637-647 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Aryani Y, Lilis D, Hairunisyah R. Educational Interventions Targeting Anxiety Reduction in the Prenatal Period. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :637-647

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78086-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-78086-en.html

1- Department of Midwifery, Riau Ministry of Health Polytechnic of Health, Riau, Indonesia

2- Department of Midwifery, Jambi Ministry of Health Polytechnic of Health, Jambi, Indonesia

3- Department of Midwifery, Ministry of Health Polytechnic of Health, Palembang, Indonesia

2- Department of Midwifery, Jambi Ministry of Health Polytechnic of Health, Jambi, Indonesia

3- Department of Midwifery, Ministry of Health Polytechnic of Health, Palembang, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 821 kb]

(1803 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (875 Views)

Full-Text: (70 Views)

Introduction

Pregnancy-related anxiety is becoming increasingly recognized as a serious public health issue; estimates indicate that up to 20% of expectant mothers may experience clinically significant anxiety symptoms [1, 2]. The implications of maternal anxiety extend beyond the individual, impacting both maternal and fetal health outcomes. High levels of anxiety during pregnancy are associated with adverse effects, such as preterm labor, low birth weight, impaired fetal neurodevelopment, and an increased risk of postpartum depression [1, 3-6]. Consequently, addressing prenatal anxiety is essential not only for maternal well-being but also for promoting optimal infant development and mitigating future psychological risks for both mother and child [7-9].

Educational interventions have emerged as a promising avenue for reducing prenatal anxiety, offering a structured approach to inform and empower expectant mothers [10, 11]. These interventions encompass a wide range of strategies, including informational sessions on pregnancy and childbirth, stress management techniques, relaxation exercises, and skills-based approaches such as mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) [12-14]. By equipping women with knowledge and coping strategies, educational interventions aim to alleviate anxiety, foster self-efficacy, and provide women with a sense of control and preparedness for the challenges of pregnancy and childbirth [15, 16].

Previous systematic reviews have attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of such interventions. These reviews have provided important insights, suggesting that interventions like mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), CBT, and psychoeducational programs can help reduce anxiety in pregnant women [12, 17, 18]. However, significant limitations remain. Many prior reviews focus narrowly on specific types of interventions, which limits the understanding of how different educational approaches compare in terms of effectiveness. For instance, some reviews exclusively address mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) or CBT, thereby overlooking the potential benefits of integrative or alternative educational strategies [12, 17]. Other systematic reviews have included only selected populations, such as high-risk pregnancies or first-time mothers, which limits the applicability of their findings to the larger prenatal population [19].

Moreover, the methodology in many previous reviews poses challenges for interpretation. Issues, such as small sample sizes, variability in intervention delivery, and inconsistent outcome measures have hindered the ability to draw robust conclusions. For instance, educational interventions often vary widely in content, frequency, duration, and delivery method (in-person vs. virtual), creating a need for a clearer understanding of which components are most impactful. Additionally, several systematic reviews have identified gaps in follow-up studies, leaving questions about the long-term effectiveness of these interventions and whether initial anxiety reductions are sustained postpartum [3, 6, 14].

The urgency for a comprehensive review of educational interventions aimed at reducing prenatal anxiety is underscored by both the rising prevalence of maternal anxiety and the increasing demand for accessible, evidence-based resources that can be implemented in diverse healthcare settings. A broad and systematic evaluation is needed to address the limitations in previous research and to establish a clearer understanding of the efficacy, scalability, and applicability of various educational models for reducing prenatal anxiety. We, therefore, aimed to fill these gaps by synthesizing findings from a diverse range of studies, analyzing the effectiveness of different educational strategies, and providing an evidence-based framework to guide future intervention development and implementation.

In conclusion, this analysis aimed to critically evaluate the available data while also highlighting areas that require further investigation and identifying best practices. By doing so, it hopes to support the continuous development of easily accessible, flexible, and effective educational interventions that can significantly reduce prenatal anxiety and improve the health of both mothers and children.

Information and Methods

This systematic review conducted in 2024, followed the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) 2020 recommendations [20] to provide a thorough and uniform approach to examining the research on educational programs aimed at reducing anxiety during pregnancy.

Eligibility criteria

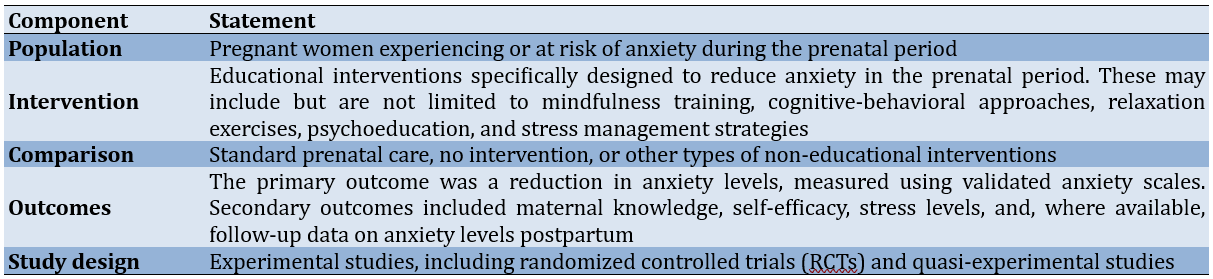

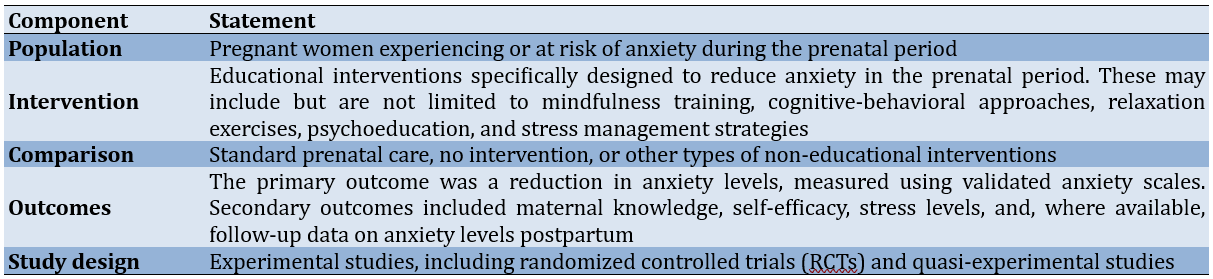

The PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study design) framework was used to establish the eligibility criteria for the studies included in this review (Table 1).

Table 1. The population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) statements

Literature search

Several electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library, were thoroughly searched. The search was not restricted by publication date to capture the full scope of relevant literature. Additional sources included Google Scholar, manual reference list searching from qualified research, and grey literature sources, such as dissertations and conference proceedings.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, and articles written in English that assessed prenatal or pregnant women.

Search strategy

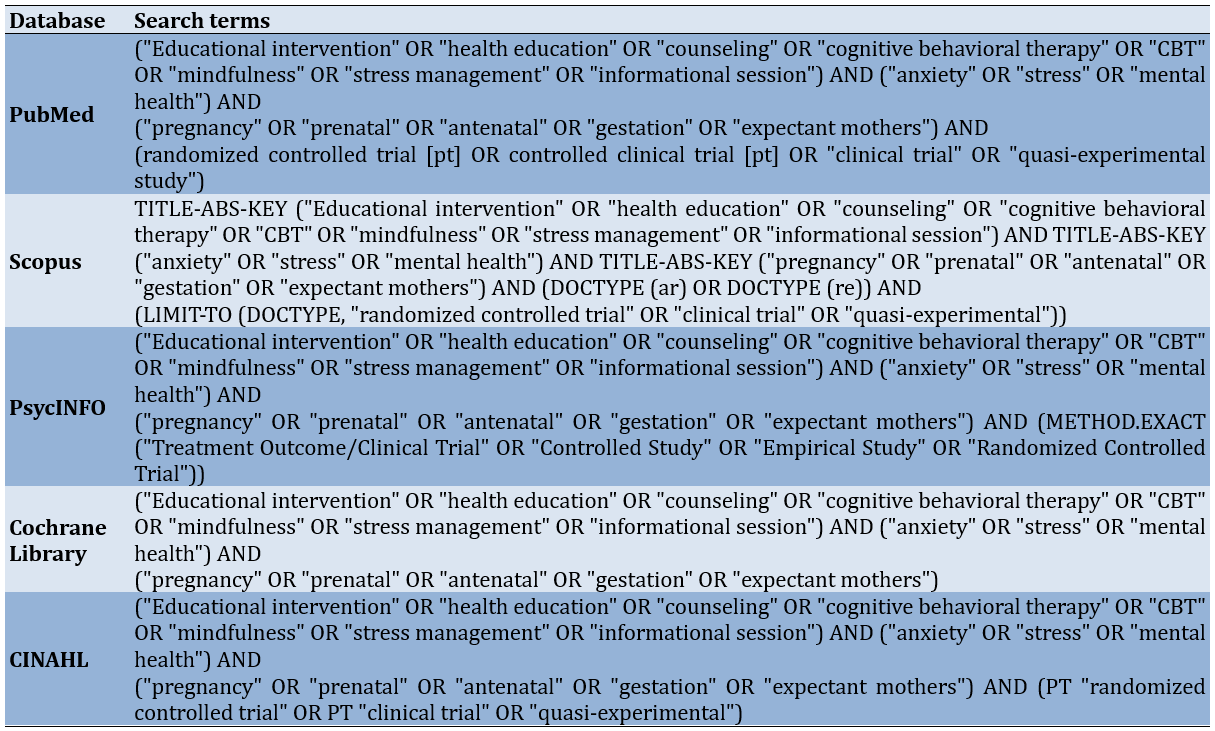

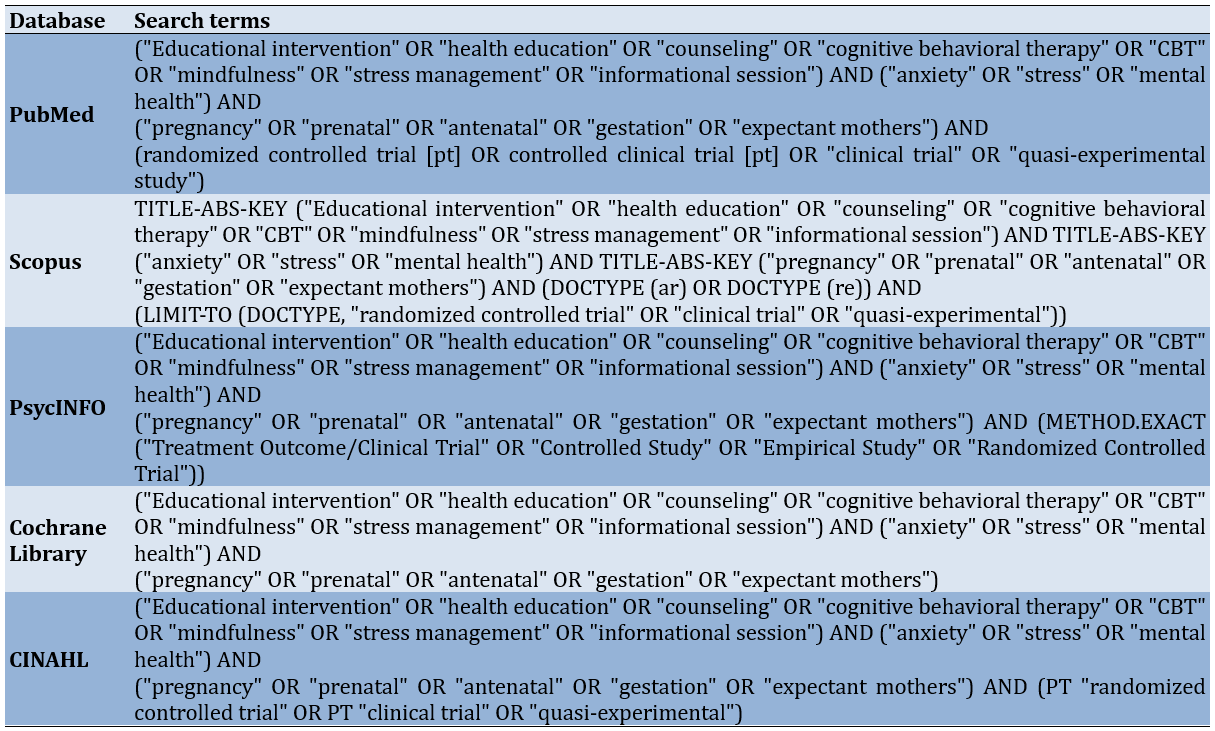

To ensure sensitivity and relevance, a customized search strategy was developed with guidance from a seasoned librarian. Boolean operators were used to combine keywords with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, which included terms, like “prenatal anxiety,” “pregnancy,” “educational intervention,” “stress reduction,” and “self-management.” An illustration of a PubMed search query included the terms (“prenatal anxiety” OR “maternal anxiety” OR “pregnancy anxiety”) AND (“educational intervention” OR “psychoeducation” OR “mindfulness” OR “cognitive-behavioral therapy” OR “stress management”) (Table 2).

Table 2. Search string in databases

Selection process

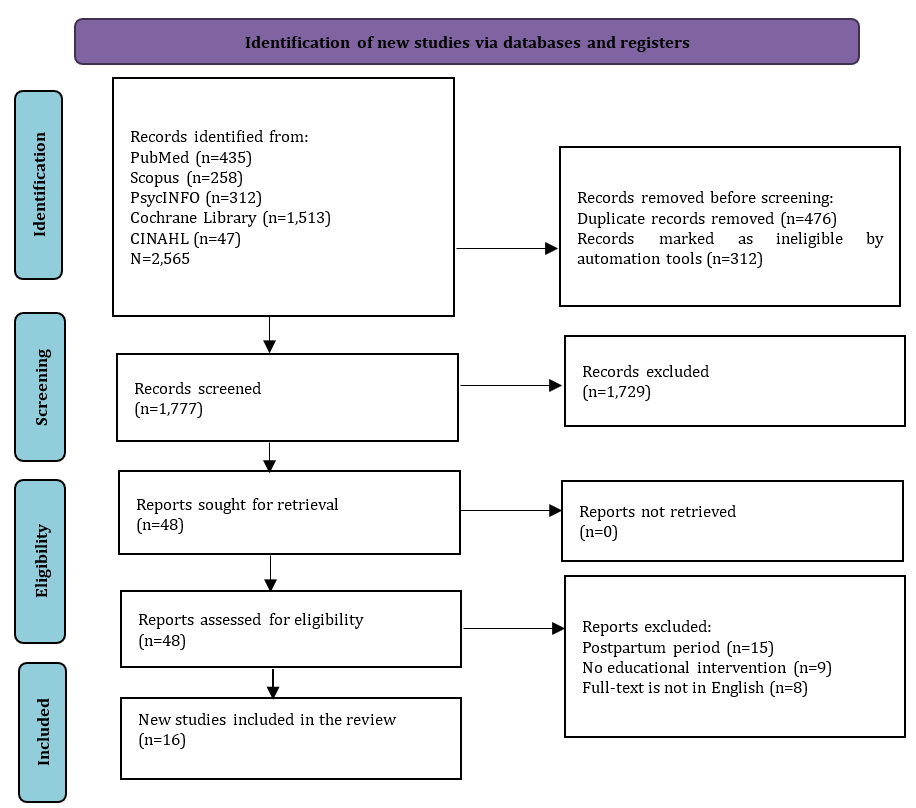

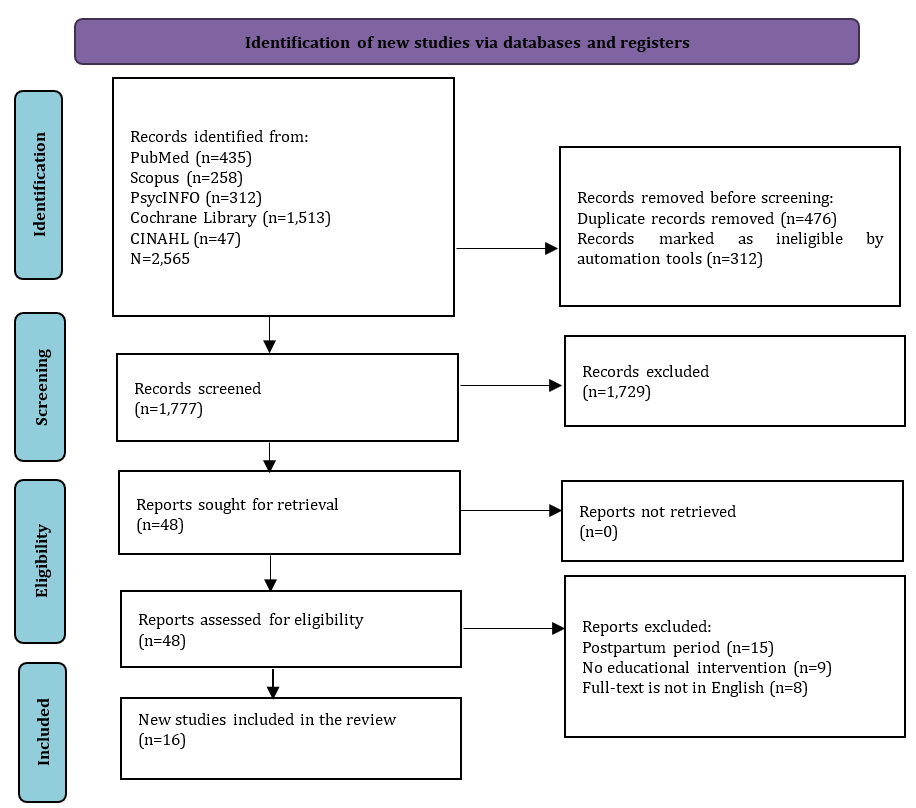

Duplicate records were eliminated once all records obtained through database searches were imported into reference management software. Two reviewers individually assessed the abstracts and titles. The next step involved a full-text review of studies that met the initial eligibility criteria. Discussions or, if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer were used to resolve disagreements regarding the selection of studies. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of study selection

Data collection process

Two reviewers used a standardized data extraction form to independently extract the data. The extracted data included study features (e.g., authors, year, country), participant demographics, specifics of the educational intervention (e.g., content, duration, delivery method), comparison groups, outcome measures, and major findings. Consensus or third-party adjudication was employed to resolve any disputes that arose during data extraction.

Study quality

The reviewers independently evaluated the literature to determine the quality of the studies for inclusion. Although this step is not mandatory in systematic review protocols, the reviewers considered it beneficial for identifying the strengths and limitations of the selected studies. Due to the diverse nature of the articles, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) for randomized studies was chosen for its ability to systematically evaluate study quality. CASP provides a structured set of questions specifically designed for different study designs, particularly randomized studies. Each CASP checklist includes 11 questions with response options of “yes,” “no,” or “can’t tell,” facilitating a standardized appraisal process. Study quality was classified into three categories, namely strong, moderate, and weak. A study was rated as strong if all responses were affirmative, moderate if there were two non-affirmative responses (“can’t tell” or “no”), and weak if there were three non-affirmative responses.

Risk of Bias

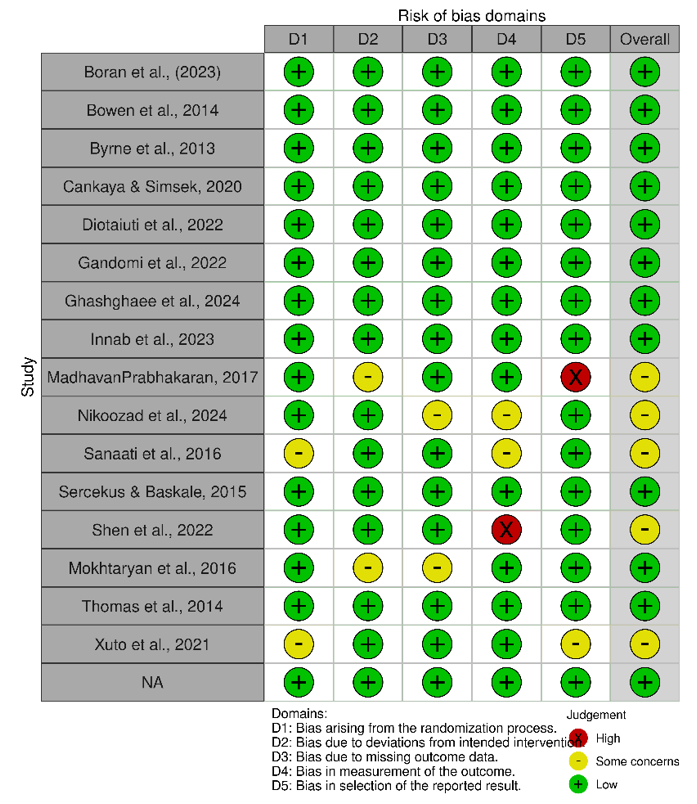

The risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB2) was used to evaluate bias in each study. This tool was selected for its structured, validated framework specifically designed to detect bias within RCTs, addressing essential areas, such as randomization, deviations from the planned interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting. The RoB 2 tool provides a comprehensive and consistent approach to quality assessment, which strengthens the reliability of the review’s conclusions. It includes five domains that assess both internal and external validity, with results classified into four levels, namely low, some concerns, high, and very high. All authors reviewed and approved the RoB assessment results, incorporating feedback from external reviewers.

Data synthesis

The results were analyzed and compiled using a narrative synthesis. A meta-analysis was not planned due to the expected variability in trial designs, interventions, and outcome measures. Studies were grouped by intervention type (e.g., mindfulness, CBT, psychoeducation) to facilitate a detailed comparison of approaches. Common themes, intervention components, and outcome patterns were identified, and the quality of evidence for each approach was assessed.

Findings

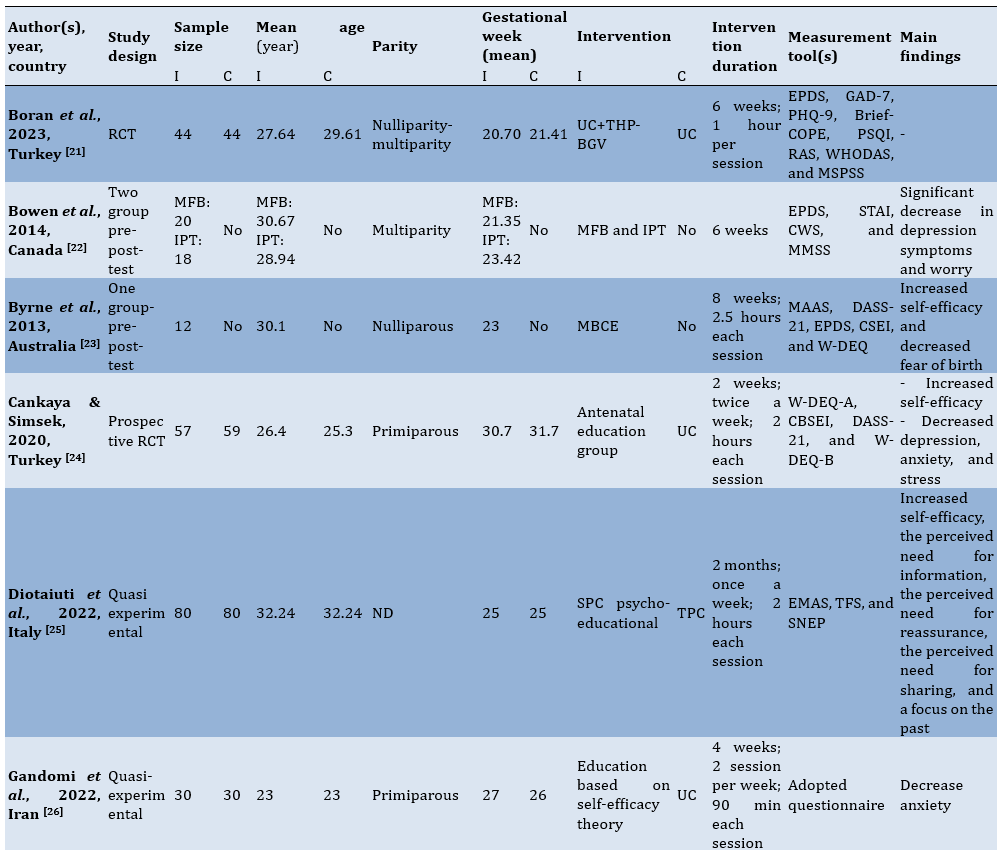

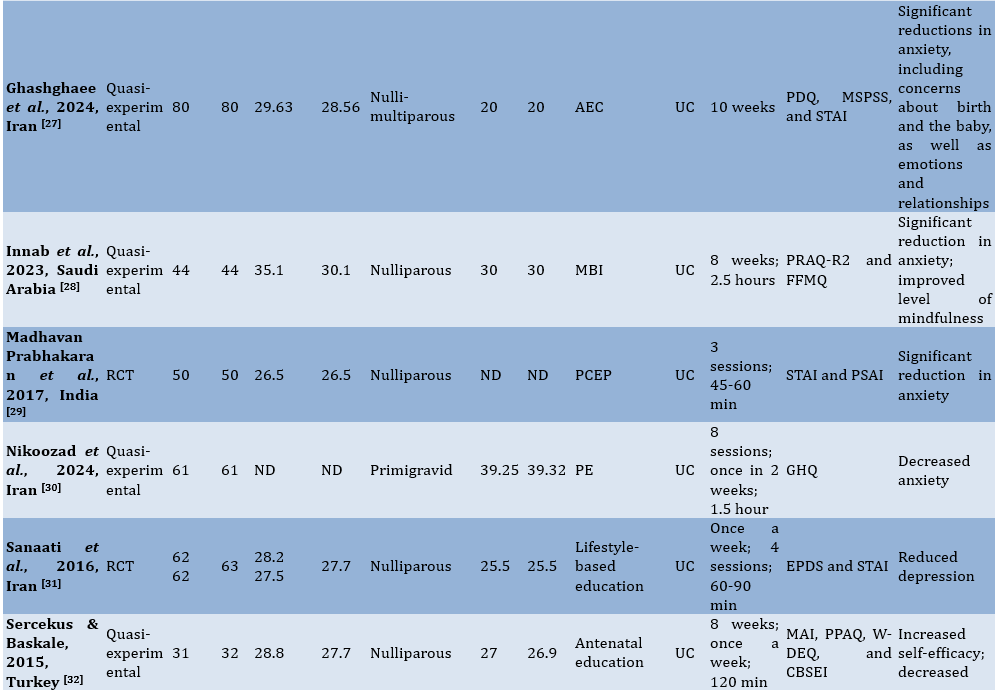

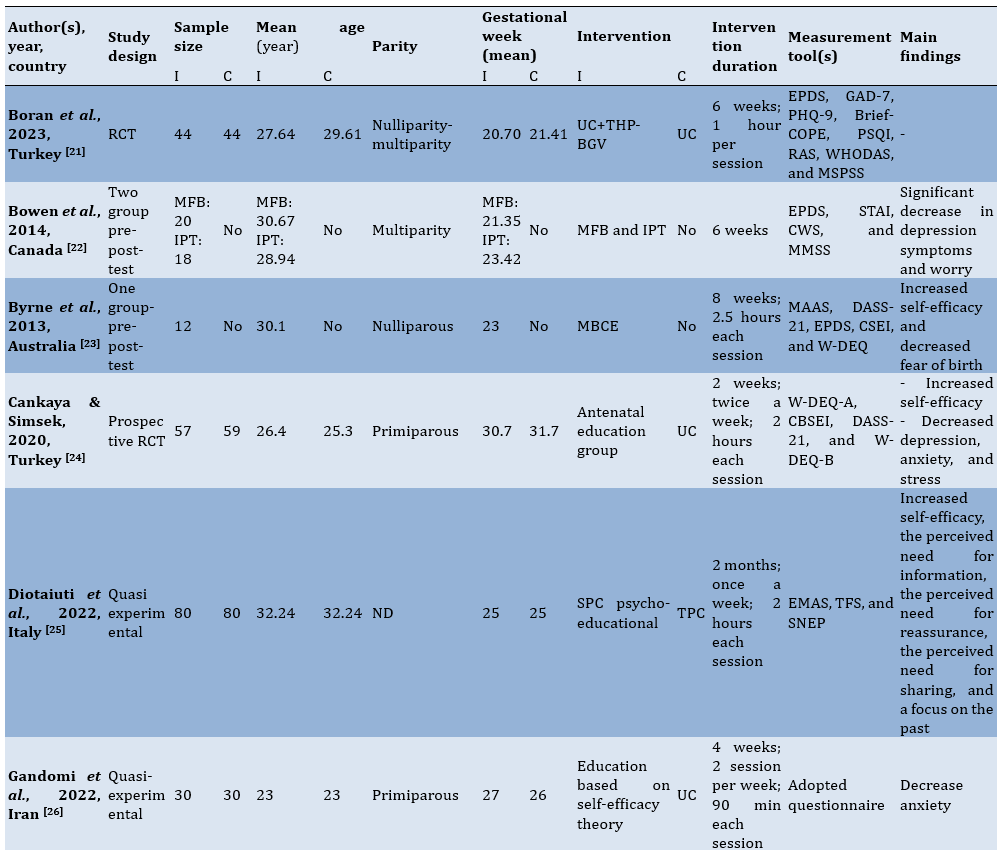

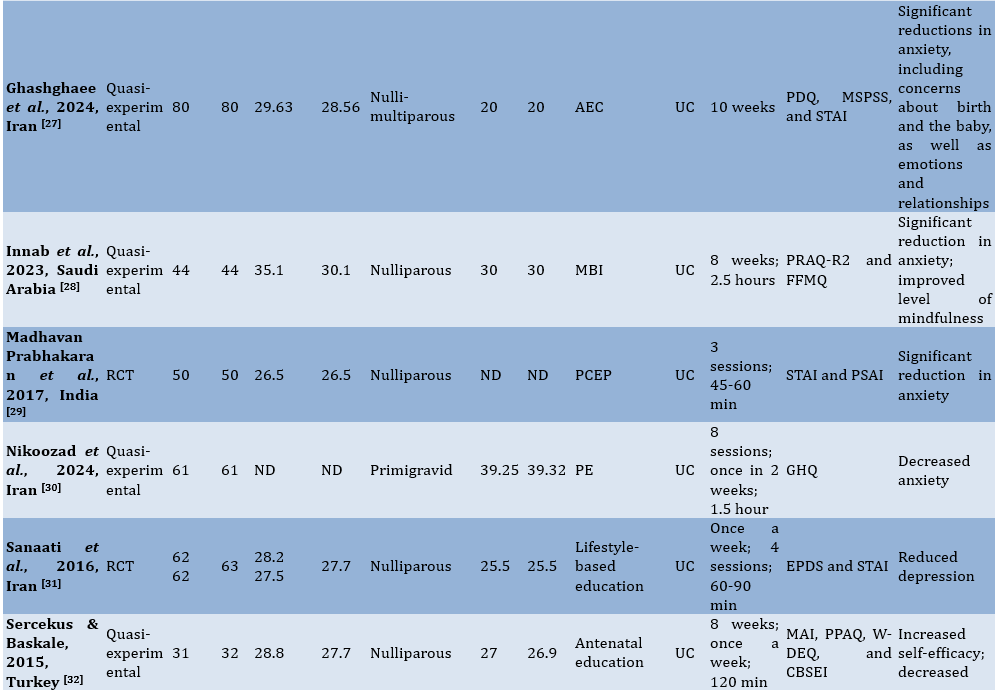

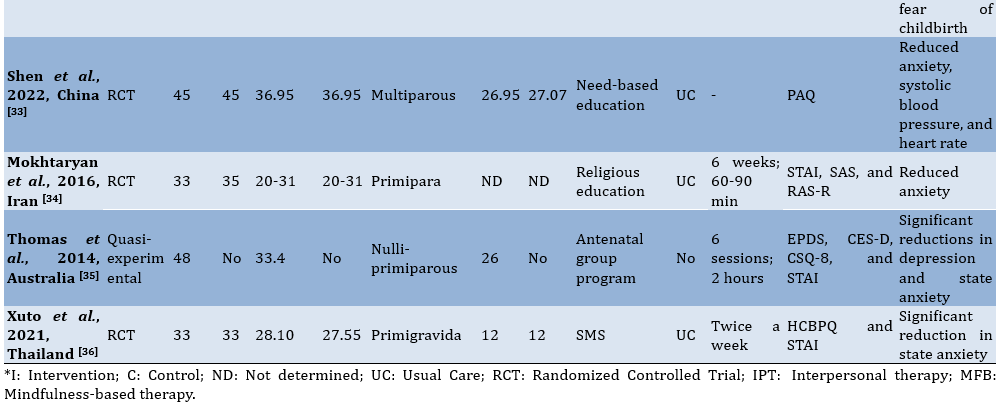

The initial database query yielded 2,565 articles. Following the removal of 788 duplicates and irrelevant articles unrelated to the review’s focus, 1,777 articles were available for screening. During the eligibility evaluation, 48 studies were assessed, resulting in the exclusion of 34 articles for various reasons. Ultimately, only 16 studies met the criteria and will proceed to the next stage for data extraction and analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Characteristics of the eligible studies

Study selection

Seventeen relevant studies that examined how educational interventions affected pregnant women’s anxiety levels were included in the systematic review. These investigations encompassed pre-post-test research, quasi-experimental methods, and RCTs. The studies were conducted in various countries, including Turkey, Canada, Australia, Iran, Italy, Thailand, and Saudi Arabia, reflecting diverse cultural and healthcare contexts.

Study characteristics

The majority of the included studies focused on nulliparous or primiparous women, with sample sizes varying from 12 to 80 individuals per group. Participants’ mean ages ranged from 20 to 36 years. Interventions were predominantly delivered during the second or third trimesters when pregnancy-related anxiety often peaks.

Most interventions consisted of weekly or biweekly sessions lasting one to two and a half hours, with durations ranging f

rom two weeks to ten weeks. Some studies employed innovative delivery methods, such as short message services (SMS) or digital platforms, to enhance accessibility.

Anxiety was the primary outcome assessed in all of the studies, utilizing well-known tools including the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ-R2), and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Self-efficacy, mindfulness, and symptoms of depression were secondary outcomes.

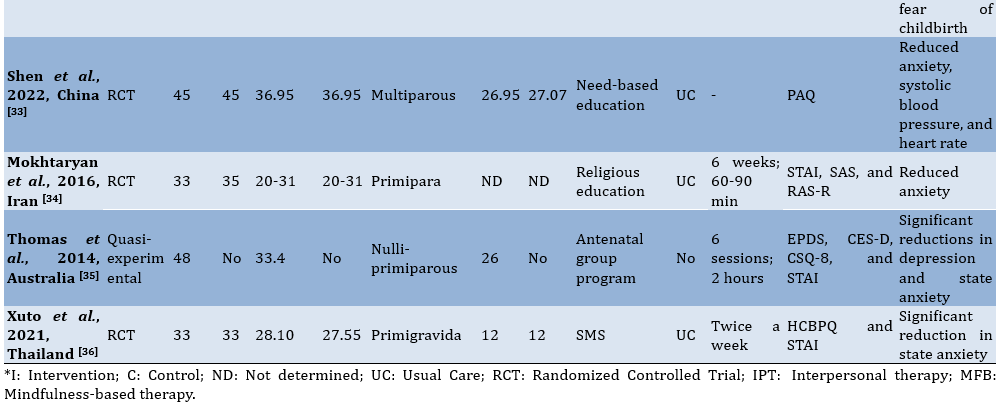

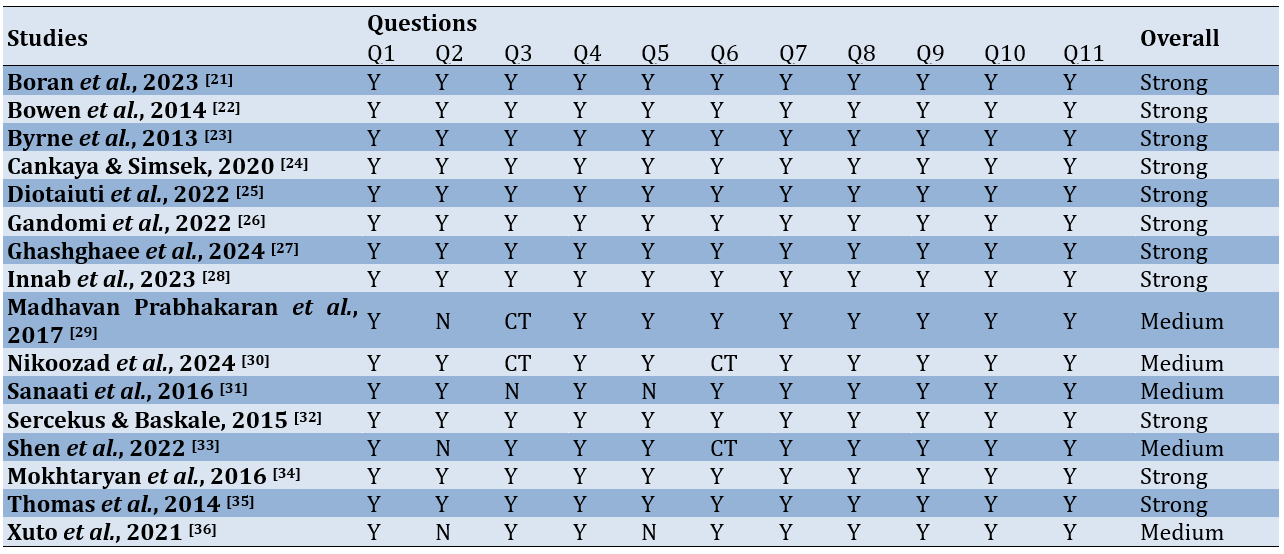

Study quality assessment

An overview of the study quality evaluation using the CASP tool is provided below. Based on the assessment results, the eligible studies are generally categorized as strong, while six studies fall into the medium category (Table 4).

Table 4. Study quality assessment results

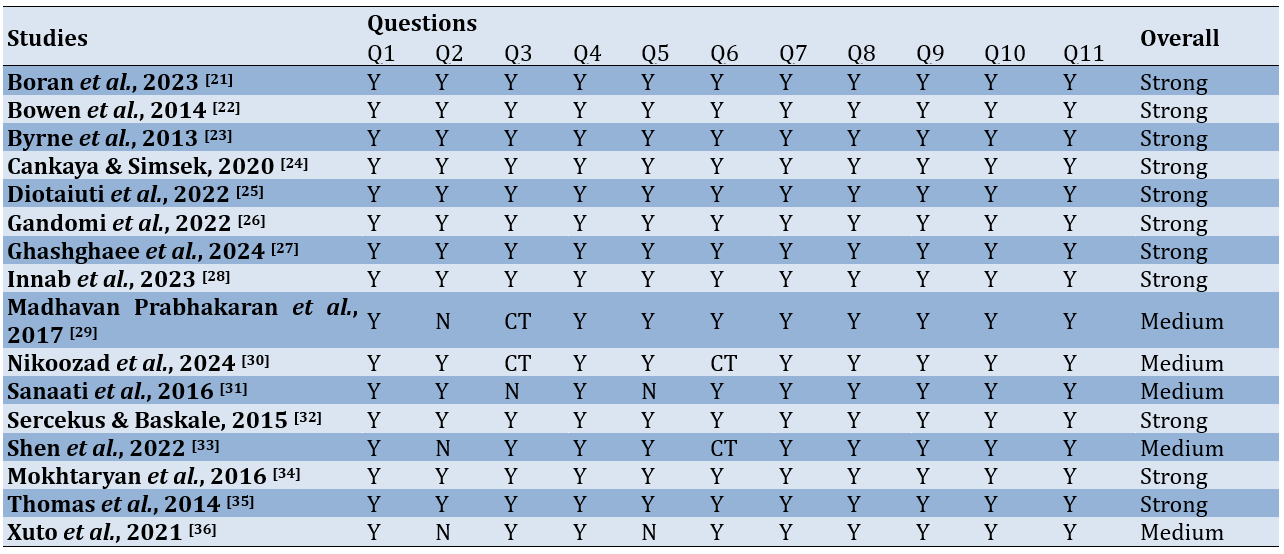

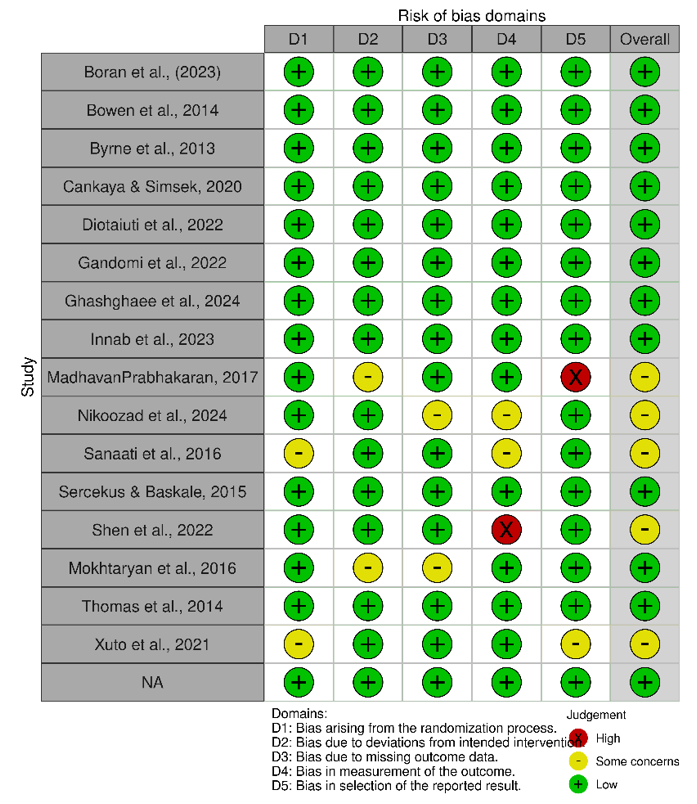

Risk of Bias assessment

Based on the assessment of the five dimensions of the RoB2 tool, it was found that most of the studies fell into the low risk of bias category, while six studies were categorized as having some concerns (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary of risk of bias assessment.

Intervention categories

The interventions were grouped into the following five categories based on their core strategies.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs)

Studies by Bowen et al., Byrne et al. and Innab et al. [22, 23, 28] implemented MBIs focusing on body awareness, emotional regulation, and relaxation. Techniques included body scan meditation, mindfulness of breathing, and awareness of routine activities. These interventions improved participants’ mindfulness levels and reduced anxiety (p<0.05).

Antenatal education programs

Studies by Cankaya & Simsek and Sercekus & Baskale [24, 32] incorporated structured education on childbirth, nutrition, psychological changes, and labor preparation. These programs significantly improved participants’ self-efficacy (p<0.01) and reduced fear of childbirth and anxiety (p<0.01).

Lifestyle-based and psychoeducational strategies

Interventions by Diotaiuti et al. and Sanaati et al. [25, 31] addressed lifestyle components such as sleep, nutrition, and physical activity. Psychoeducational elements included cognitive restructuring, relaxation techniques, and stress management strategies, which led to reduced anxiety and improved overall well-being (p<0.001).

Cultural and religious interventions

Nikoozad et al. and Mokhtaryan et al. [30, 34] tailored interventions to cultural and religious contexts, integrating spiritual teachings and ethical values. These interventions significantly reduced anxiety levels (p=0.001) and provided emotional and moral support.

Digital and remote interventions

Xuto et al. [36] delivered educational content via SMS, focusing on nutrition, mental health, and labor preparation. Although cost-effective and scalable, these interventions showed moderate reductions in anxiety (p=0.02), indicating the potential for enhancing digital strategies.

Outcomes

Anxiety reduction

All included studies reported statistically significant reductions in anxiety levels following the interventions. For instance, Gandomi et al. [26] observed a substantial decrease in anxiety scores (p<0.001), and Shen et al. [33] reported reductions in systolic blood pressure and heart rate alongside improvements in anxiety (p<0.05).

Self-efficacy improvements

Studies by Byrne et al. and Diotaiuti et al. [23, 25] highlighted enhanced maternal self-efficacy, which is critical for reducing pregnancy-related stress and increasing confidence in labor and delivery preparation.

Other psychological benefits

Several studies demonstrated additional benefits, including decreased symptoms of depression (e.g., Bowen et al. and Madhavan Prabhakaran et al. [22, 29]) and reduced fear of childbirth (e.g., Sercekus & Baskale [32]).

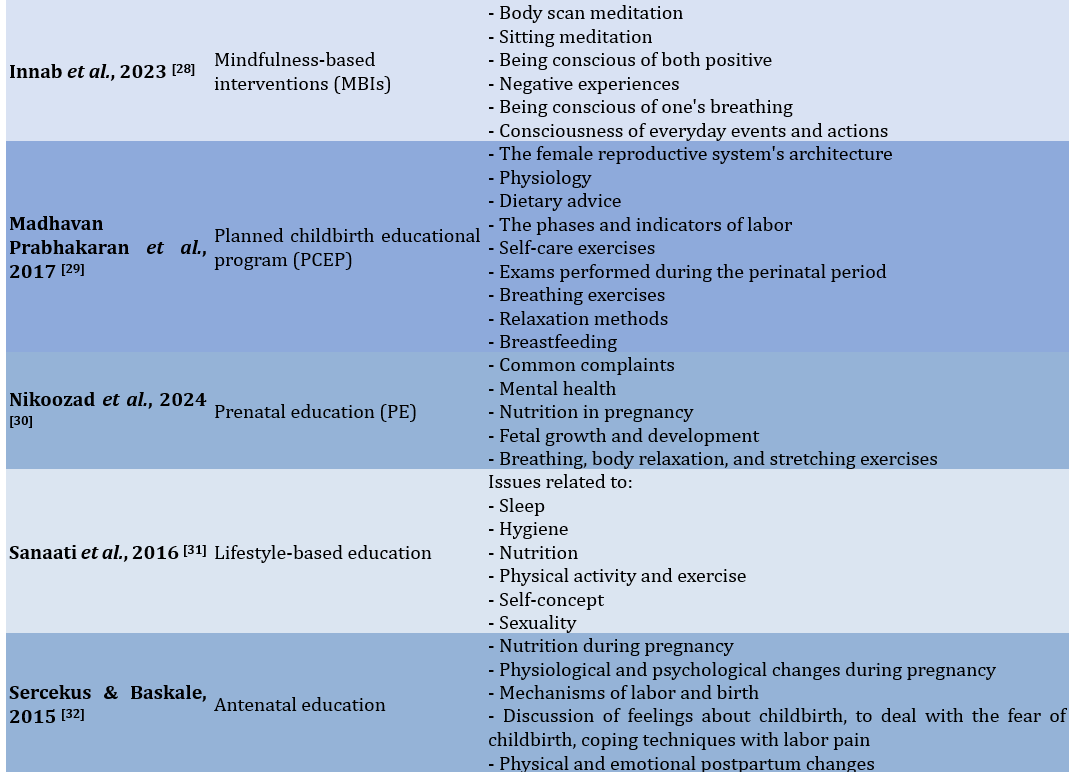

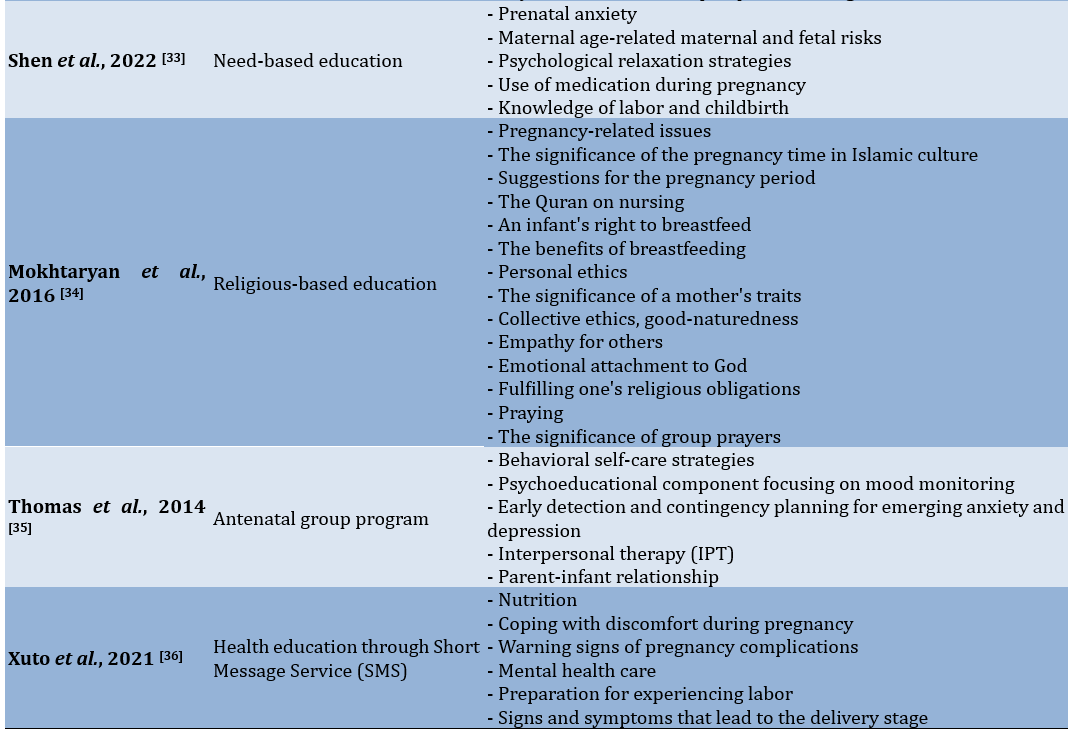

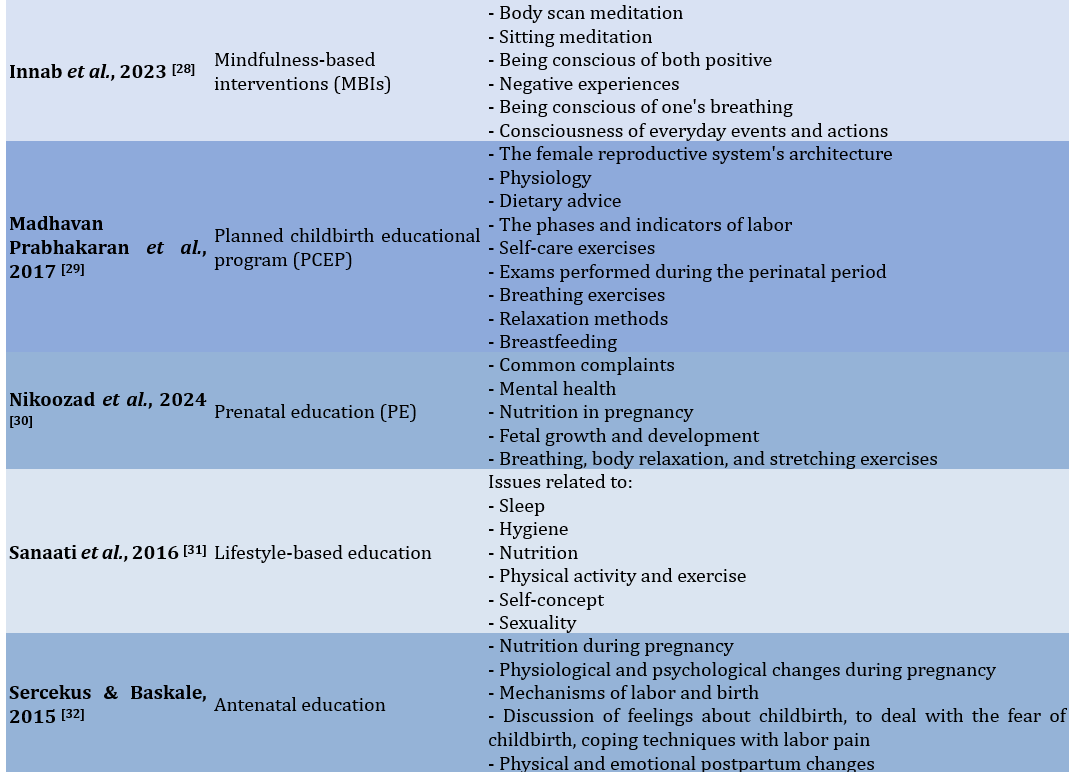

Broader psychosocial gains

Psychoeducational programs increased participants’ perceived social support, coping mechanisms, and emotional resilience (e.g., Diotaiuti et al. and Ghashghaee et al. [25, 27]) (Table 5).

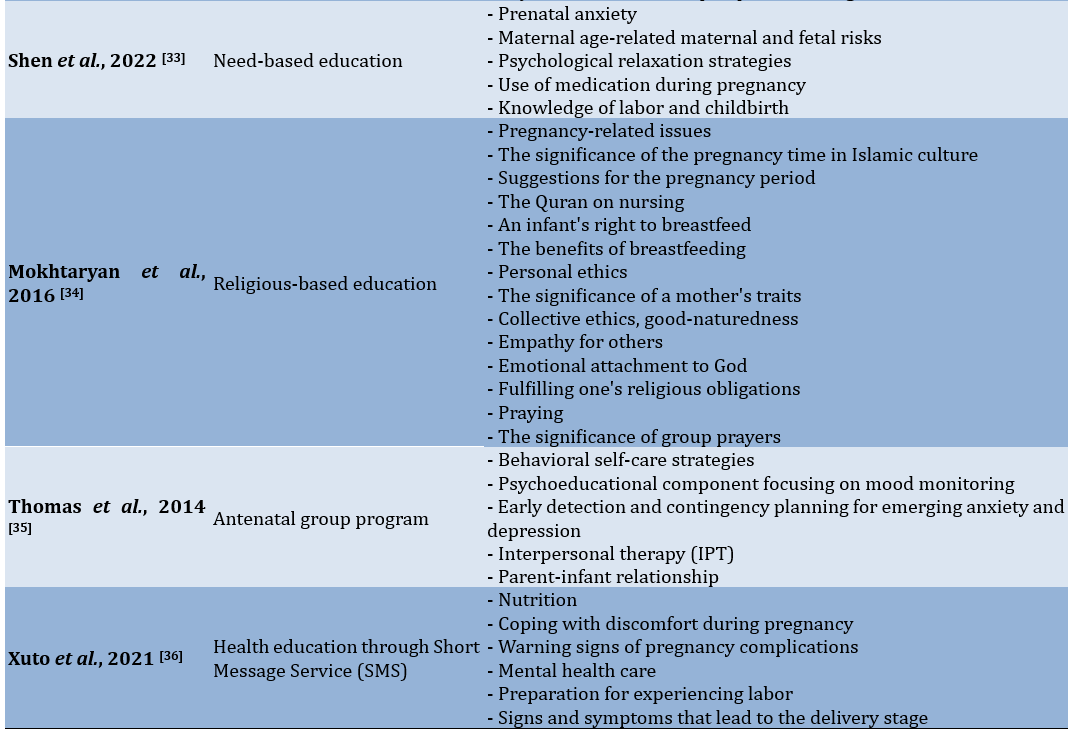

Table 5. Content of the educational intervention strategy

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of different educational interventions in reducing prenatal anxiety. The importance of educational treatments in lowering prenatal anxiety is reaffirmed by this systematic study and aligns with a growing body of evidence that highlights their effectiveness in improving maternal mental health. The findings demonstrated that these interventions, which range from MBIs to culturally tailored approaches, consistently reduced anxiety, enhanced self-efficacy, and provided broader psychosocial benefits.

MBIs showed significant reductions in anxiety, aligning with previous research that emphasizes their role in enhancing emotional regulation and resilience. For instance, Shi & MacBeth [37] noted that mindfulness practices improve mental health outcomes in perinatal populations by targeting the cognitive and emotional dimensions of anxiety. Techniques, such as body scan meditation and mindfulness of routine activities, as seen in the studies included in this review, provide pregnant women with practical tools to manage stress effectively. However, consistent with Matvienko-Sikar et al. [38], the success of these interventions depends on participants’ familiarity with mindfulness practices. Future research should investigate introductory or hybrid models that cater to varying levels of mindfulness experience, potentially broadening their accessibility and impact.

Antenatal education programs offered structured and comprehensive content, addressing both the physical and psychological dimensions of pregnancy. These programs significantly reduced the fear of childbirth and improved maternal preparedness, echoing the findings of previous studies [39, 40], which identified antenatal education as a key factor in improving maternal confidence. However, Gluck et al. [41] reported mixed results regarding the effectiveness of such programs, which could be attributed to inconsistencies in program structure and delivery. The studies in this review, featuring well-rounded content and culturally sensitive frameworks, highlight the importance of tailoring antenatal education to meet the diverse needs of pregnant women. Establishing standardized yet flexible guidelines could further enhance their effectiveness.

Lifestyle and psychoeducational interventions were particularly impactful in addressing both the mental and physical aspects of prenatal anxiety. By incorporating stress management techniques, relaxation exercises, and lifestyle modifications, such as improved nutrition and sleep hygiene, these interventions aligned with findings by Dubreucq et al. [42], who emphasize the importance of holistic approaches to maternal health. However, unlike Van Der Windt et al. [43], who suggest that lifestyle interventions alone may not sufficiently address deep-seated psychological concerns, this review highlighted the added value of integrating psychoeducational elements to enhance overall efficacy. This combined approach addresses not only immediate anxiety but also builds long-term coping mechanisms, fostering greater maternal resilience.

Culturally and religiously tailored interventions were highly effective in contexts where spiritual and traditional values are central to maternal care. Consistent with Rahimnejad et al. [44], these interventions provide emotional reassurance and a sense of purpose, contributing significantly to anxiety reduction. By incorporating familiar cultural and spiritual practices, these programs resonate deeply with participants, reinforcing their relevance in culturally homogeneous populations. However, as Shorey et al. [45] pointed out, such approaches may have limited generalizability in multicultural or secular contexts. This review suggests that while cultural relevance is vital, interventions can be adapted to retain core principles of empathy and support while being inclusive of diverse populations.

Digital and remote interventions, such as SMS-based education, offered scalable and accessible solutions, particularly for underserved populations. While Ahmed et al. [46] highlight challenges with user engagement and limited interactivity in digital tools, the studies in this review demonstrated moderate success in reducing anxiety. These findings align with those of Thonon et al. [47], who underscored the potential of mHealth tools to bridge gaps in healthcare access. To enhance effectiveness, future digital interventions should incorporate interactive features, personalized feedback, and multimedia content to foster higher user engagement and satisfaction.

While the findings of this review are promising, several limitations warrant consideration. The heterogeneity of study designs, sample sizes, and intervention durations complicates the comparability of results. Moreover, most studies focused on short-term outcomes, leaving the long-term sustainability of these interventions largely unexplored. Variability in the tools used to measure anxiety and related outcomes further introduces potential biases, emphasizing the need for standardized metrics in future research. Additionally, the predominance of studies conducted in specific cultural contexts limits the generalizability of the findings to more diverse populations. Addressing these limitations through longitudinal studies, more diverse sampling and methodological standardization will strengthen the evidence base and provide clearer guidance for implementing these interventions in routine prenatal care.

This review underscores the efficacy of educational interventions in reducing anxiety among pregnant women and highlights the importance of tailored approaches. MBIs, antenatal education programs, and culturally sensitive methods emerged as particularly effective strategies. The success of digital interventions demonstrates their potential for scalability and accessibility. Integrating these findings into routine prenatal care can significantly enhance maternal mental health and well-being. Future studies should focus on overcoming methodological limitations and expanding the evidence base to ensure equitable and effective prenatal support for all populations.

Conclusion

Diverse educational interventions effectively reduce prenatal anxiety.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors' Contribution: Aryani Y (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/ (50%); Lilis DN (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Hairunisyah R (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: None declared.

Pregnancy-related anxiety is becoming increasingly recognized as a serious public health issue; estimates indicate that up to 20% of expectant mothers may experience clinically significant anxiety symptoms [1, 2]. The implications of maternal anxiety extend beyond the individual, impacting both maternal and fetal health outcomes. High levels of anxiety during pregnancy are associated with adverse effects, such as preterm labor, low birth weight, impaired fetal neurodevelopment, and an increased risk of postpartum depression [1, 3-6]. Consequently, addressing prenatal anxiety is essential not only for maternal well-being but also for promoting optimal infant development and mitigating future psychological risks for both mother and child [7-9].

Educational interventions have emerged as a promising avenue for reducing prenatal anxiety, offering a structured approach to inform and empower expectant mothers [10, 11]. These interventions encompass a wide range of strategies, including informational sessions on pregnancy and childbirth, stress management techniques, relaxation exercises, and skills-based approaches such as mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) [12-14]. By equipping women with knowledge and coping strategies, educational interventions aim to alleviate anxiety, foster self-efficacy, and provide women with a sense of control and preparedness for the challenges of pregnancy and childbirth [15, 16].

Previous systematic reviews have attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of such interventions. These reviews have provided important insights, suggesting that interventions like mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), CBT, and psychoeducational programs can help reduce anxiety in pregnant women [12, 17, 18]. However, significant limitations remain. Many prior reviews focus narrowly on specific types of interventions, which limits the understanding of how different educational approaches compare in terms of effectiveness. For instance, some reviews exclusively address mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) or CBT, thereby overlooking the potential benefits of integrative or alternative educational strategies [12, 17]. Other systematic reviews have included only selected populations, such as high-risk pregnancies or first-time mothers, which limits the applicability of their findings to the larger prenatal population [19].

Moreover, the methodology in many previous reviews poses challenges for interpretation. Issues, such as small sample sizes, variability in intervention delivery, and inconsistent outcome measures have hindered the ability to draw robust conclusions. For instance, educational interventions often vary widely in content, frequency, duration, and delivery method (in-person vs. virtual), creating a need for a clearer understanding of which components are most impactful. Additionally, several systematic reviews have identified gaps in follow-up studies, leaving questions about the long-term effectiveness of these interventions and whether initial anxiety reductions are sustained postpartum [3, 6, 14].

The urgency for a comprehensive review of educational interventions aimed at reducing prenatal anxiety is underscored by both the rising prevalence of maternal anxiety and the increasing demand for accessible, evidence-based resources that can be implemented in diverse healthcare settings. A broad and systematic evaluation is needed to address the limitations in previous research and to establish a clearer understanding of the efficacy, scalability, and applicability of various educational models for reducing prenatal anxiety. We, therefore, aimed to fill these gaps by synthesizing findings from a diverse range of studies, analyzing the effectiveness of different educational strategies, and providing an evidence-based framework to guide future intervention development and implementation.

In conclusion, this analysis aimed to critically evaluate the available data while also highlighting areas that require further investigation and identifying best practices. By doing so, it hopes to support the continuous development of easily accessible, flexible, and effective educational interventions that can significantly reduce prenatal anxiety and improve the health of both mothers and children.

Information and Methods

This systematic review conducted in 2024, followed the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) 2020 recommendations [20] to provide a thorough and uniform approach to examining the research on educational programs aimed at reducing anxiety during pregnancy.

Eligibility criteria

The PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study design) framework was used to establish the eligibility criteria for the studies included in this review (Table 1).

Table 1. The population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) statements

Literature search

Several electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library, were thoroughly searched. The search was not restricted by publication date to capture the full scope of relevant literature. Additional sources included Google Scholar, manual reference list searching from qualified research, and grey literature sources, such as dissertations and conference proceedings.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, and articles written in English that assessed prenatal or pregnant women.

Search strategy

To ensure sensitivity and relevance, a customized search strategy was developed with guidance from a seasoned librarian. Boolean operators were used to combine keywords with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, which included terms, like “prenatal anxiety,” “pregnancy,” “educational intervention,” “stress reduction,” and “self-management.” An illustration of a PubMed search query included the terms (“prenatal anxiety” OR “maternal anxiety” OR “pregnancy anxiety”) AND (“educational intervention” OR “psychoeducation” OR “mindfulness” OR “cognitive-behavioral therapy” OR “stress management”) (Table 2).

Table 2. Search string in databases

Selection process

Duplicate records were eliminated once all records obtained through database searches were imported into reference management software. Two reviewers individually assessed the abstracts and titles. The next step involved a full-text review of studies that met the initial eligibility criteria. Discussions or, if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer were used to resolve disagreements regarding the selection of studies. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of study selection

Data collection process

Two reviewers used a standardized data extraction form to independently extract the data. The extracted data included study features (e.g., authors, year, country), participant demographics, specifics of the educational intervention (e.g., content, duration, delivery method), comparison groups, outcome measures, and major findings. Consensus or third-party adjudication was employed to resolve any disputes that arose during data extraction.

Study quality

The reviewers independently evaluated the literature to determine the quality of the studies for inclusion. Although this step is not mandatory in systematic review protocols, the reviewers considered it beneficial for identifying the strengths and limitations of the selected studies. Due to the diverse nature of the articles, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) for randomized studies was chosen for its ability to systematically evaluate study quality. CASP provides a structured set of questions specifically designed for different study designs, particularly randomized studies. Each CASP checklist includes 11 questions with response options of “yes,” “no,” or “can’t tell,” facilitating a standardized appraisal process. Study quality was classified into three categories, namely strong, moderate, and weak. A study was rated as strong if all responses were affirmative, moderate if there were two non-affirmative responses (“can’t tell” or “no”), and weak if there were three non-affirmative responses.

Risk of Bias

The risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB2) was used to evaluate bias in each study. This tool was selected for its structured, validated framework specifically designed to detect bias within RCTs, addressing essential areas, such as randomization, deviations from the planned interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting. The RoB 2 tool provides a comprehensive and consistent approach to quality assessment, which strengthens the reliability of the review’s conclusions. It includes five domains that assess both internal and external validity, with results classified into four levels, namely low, some concerns, high, and very high. All authors reviewed and approved the RoB assessment results, incorporating feedback from external reviewers.

Data synthesis

The results were analyzed and compiled using a narrative synthesis. A meta-analysis was not planned due to the expected variability in trial designs, interventions, and outcome measures. Studies were grouped by intervention type (e.g., mindfulness, CBT, psychoeducation) to facilitate a detailed comparison of approaches. Common themes, intervention components, and outcome patterns were identified, and the quality of evidence for each approach was assessed.

Findings

The initial database query yielded 2,565 articles. Following the removal of 788 duplicates and irrelevant articles unrelated to the review’s focus, 1,777 articles were available for screening. During the eligibility evaluation, 48 studies were assessed, resulting in the exclusion of 34 articles for various reasons. Ultimately, only 16 studies met the criteria and will proceed to the next stage for data extraction and analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Characteristics of the eligible studies

Study selection

Seventeen relevant studies that examined how educational interventions affected pregnant women’s anxiety levels were included in the systematic review. These investigations encompassed pre-post-test research, quasi-experimental methods, and RCTs. The studies were conducted in various countries, including Turkey, Canada, Australia, Iran, Italy, Thailand, and Saudi Arabia, reflecting diverse cultural and healthcare contexts.

Study characteristics

The majority of the included studies focused on nulliparous or primiparous women, with sample sizes varying from 12 to 80 individuals per group. Participants’ mean ages ranged from 20 to 36 years. Interventions were predominantly delivered during the second or third trimesters when pregnancy-related anxiety often peaks.

Most interventions consisted of weekly or biweekly sessions lasting one to two and a half hours, with durations ranging f

rom two weeks to ten weeks. Some studies employed innovative delivery methods, such as short message services (SMS) or digital platforms, to enhance accessibility.

Anxiety was the primary outcome assessed in all of the studies, utilizing well-known tools including the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ-R2), and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Self-efficacy, mindfulness, and symptoms of depression were secondary outcomes.

Study quality assessment

An overview of the study quality evaluation using the CASP tool is provided below. Based on the assessment results, the eligible studies are generally categorized as strong, while six studies fall into the medium category (Table 4).

Table 4. Study quality assessment results

Risk of Bias assessment

Based on the assessment of the five dimensions of the RoB2 tool, it was found that most of the studies fell into the low risk of bias category, while six studies were categorized as having some concerns (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary of risk of bias assessment.

Intervention categories

The interventions were grouped into the following five categories based on their core strategies.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs)

Studies by Bowen et al., Byrne et al. and Innab et al. [22, 23, 28] implemented MBIs focusing on body awareness, emotional regulation, and relaxation. Techniques included body scan meditation, mindfulness of breathing, and awareness of routine activities. These interventions improved participants’ mindfulness levels and reduced anxiety (p<0.05).

Antenatal education programs

Studies by Cankaya & Simsek and Sercekus & Baskale [24, 32] incorporated structured education on childbirth, nutrition, psychological changes, and labor preparation. These programs significantly improved participants’ self-efficacy (p<0.01) and reduced fear of childbirth and anxiety (p<0.01).

Lifestyle-based and psychoeducational strategies

Interventions by Diotaiuti et al. and Sanaati et al. [25, 31] addressed lifestyle components such as sleep, nutrition, and physical activity. Psychoeducational elements included cognitive restructuring, relaxation techniques, and stress management strategies, which led to reduced anxiety and improved overall well-being (p<0.001).

Cultural and religious interventions

Nikoozad et al. and Mokhtaryan et al. [30, 34] tailored interventions to cultural and religious contexts, integrating spiritual teachings and ethical values. These interventions significantly reduced anxiety levels (p=0.001) and provided emotional and moral support.

Digital and remote interventions

Xuto et al. [36] delivered educational content via SMS, focusing on nutrition, mental health, and labor preparation. Although cost-effective and scalable, these interventions showed moderate reductions in anxiety (p=0.02), indicating the potential for enhancing digital strategies.

Outcomes

Anxiety reduction

All included studies reported statistically significant reductions in anxiety levels following the interventions. For instance, Gandomi et al. [26] observed a substantial decrease in anxiety scores (p<0.001), and Shen et al. [33] reported reductions in systolic blood pressure and heart rate alongside improvements in anxiety (p<0.05).

Self-efficacy improvements

Studies by Byrne et al. and Diotaiuti et al. [23, 25] highlighted enhanced maternal self-efficacy, which is critical for reducing pregnancy-related stress and increasing confidence in labor and delivery preparation.

Other psychological benefits

Several studies demonstrated additional benefits, including decreased symptoms of depression (e.g., Bowen et al. and Madhavan Prabhakaran et al. [22, 29]) and reduced fear of childbirth (e.g., Sercekus & Baskale [32]).

Broader psychosocial gains

Psychoeducational programs increased participants’ perceived social support, coping mechanisms, and emotional resilience (e.g., Diotaiuti et al. and Ghashghaee et al. [25, 27]) (Table 5).

Table 5. Content of the educational intervention strategy

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of different educational interventions in reducing prenatal anxiety. The importance of educational treatments in lowering prenatal anxiety is reaffirmed by this systematic study and aligns with a growing body of evidence that highlights their effectiveness in improving maternal mental health. The findings demonstrated that these interventions, which range from MBIs to culturally tailored approaches, consistently reduced anxiety, enhanced self-efficacy, and provided broader psychosocial benefits.

MBIs showed significant reductions in anxiety, aligning with previous research that emphasizes their role in enhancing emotional regulation and resilience. For instance, Shi & MacBeth [37] noted that mindfulness practices improve mental health outcomes in perinatal populations by targeting the cognitive and emotional dimensions of anxiety. Techniques, such as body scan meditation and mindfulness of routine activities, as seen in the studies included in this review, provide pregnant women with practical tools to manage stress effectively. However, consistent with Matvienko-Sikar et al. [38], the success of these interventions depends on participants’ familiarity with mindfulness practices. Future research should investigate introductory or hybrid models that cater to varying levels of mindfulness experience, potentially broadening their accessibility and impact.

Antenatal education programs offered structured and comprehensive content, addressing both the physical and psychological dimensions of pregnancy. These programs significantly reduced the fear of childbirth and improved maternal preparedness, echoing the findings of previous studies [39, 40], which identified antenatal education as a key factor in improving maternal confidence. However, Gluck et al. [41] reported mixed results regarding the effectiveness of such programs, which could be attributed to inconsistencies in program structure and delivery. The studies in this review, featuring well-rounded content and culturally sensitive frameworks, highlight the importance of tailoring antenatal education to meet the diverse needs of pregnant women. Establishing standardized yet flexible guidelines could further enhance their effectiveness.

Lifestyle and psychoeducational interventions were particularly impactful in addressing both the mental and physical aspects of prenatal anxiety. By incorporating stress management techniques, relaxation exercises, and lifestyle modifications, such as improved nutrition and sleep hygiene, these interventions aligned with findings by Dubreucq et al. [42], who emphasize the importance of holistic approaches to maternal health. However, unlike Van Der Windt et al. [43], who suggest that lifestyle interventions alone may not sufficiently address deep-seated psychological concerns, this review highlighted the added value of integrating psychoeducational elements to enhance overall efficacy. This combined approach addresses not only immediate anxiety but also builds long-term coping mechanisms, fostering greater maternal resilience.

Culturally and religiously tailored interventions were highly effective in contexts where spiritual and traditional values are central to maternal care. Consistent with Rahimnejad et al. [44], these interventions provide emotional reassurance and a sense of purpose, contributing significantly to anxiety reduction. By incorporating familiar cultural and spiritual practices, these programs resonate deeply with participants, reinforcing their relevance in culturally homogeneous populations. However, as Shorey et al. [45] pointed out, such approaches may have limited generalizability in multicultural or secular contexts. This review suggests that while cultural relevance is vital, interventions can be adapted to retain core principles of empathy and support while being inclusive of diverse populations.

Digital and remote interventions, such as SMS-based education, offered scalable and accessible solutions, particularly for underserved populations. While Ahmed et al. [46] highlight challenges with user engagement and limited interactivity in digital tools, the studies in this review demonstrated moderate success in reducing anxiety. These findings align with those of Thonon et al. [47], who underscored the potential of mHealth tools to bridge gaps in healthcare access. To enhance effectiveness, future digital interventions should incorporate interactive features, personalized feedback, and multimedia content to foster higher user engagement and satisfaction.

While the findings of this review are promising, several limitations warrant consideration. The heterogeneity of study designs, sample sizes, and intervention durations complicates the comparability of results. Moreover, most studies focused on short-term outcomes, leaving the long-term sustainability of these interventions largely unexplored. Variability in the tools used to measure anxiety and related outcomes further introduces potential biases, emphasizing the need for standardized metrics in future research. Additionally, the predominance of studies conducted in specific cultural contexts limits the generalizability of the findings to more diverse populations. Addressing these limitations through longitudinal studies, more diverse sampling and methodological standardization will strengthen the evidence base and provide clearer guidance for implementing these interventions in routine prenatal care.

This review underscores the efficacy of educational interventions in reducing anxiety among pregnant women and highlights the importance of tailored approaches. MBIs, antenatal education programs, and culturally sensitive methods emerged as particularly effective strategies. The success of digital interventions demonstrates their potential for scalability and accessibility. Integrating these findings into routine prenatal care can significantly enhance maternal mental health and well-being. Future studies should focus on overcoming methodological limitations and expanding the evidence base to ensure equitable and effective prenatal support for all populations.

Conclusion

Diverse educational interventions effectively reduce prenatal anxiety.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors' Contribution: Aryani Y (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/ (50%); Lilis DN (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Hairunisyah R (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: None declared.

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2024/10/20 | Accepted: 2024/12/6 | Published: 2024/12/11

Received: 2024/10/20 | Accepted: 2024/12/6 | Published: 2024/12/11

References

1. Fawcett EJ, Fairbrother N, Cox ML, White IR, Fawcett JM. The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(4):18r12527. [Link] [DOI:10.4088/JCP.18r12527]

2. Goodman JH, Chenausky KL, Freeman MP. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy: A systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(10):e1153-84. [Link] [DOI:10.4088/JCP.14r09035]

3. Grigoriadis S, Graves L, Peer M, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Vigod SN, et al. Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the association with adverse perinatal outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5):17r12011. [Link] [DOI:10.4088/JCP.17r12011]

4. Araji S, Griffin A, Dixon L, Spencer SK, Peavie C, Wallace K. An overview of maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the post-partum period. J Ment Health Clin Psychol. 2020;4(4):47-56. [Link] [DOI:10.29245/2578-2959/2020/4.1221]

5. O'Sullivan A, Monk C. Maternal and environmental influences on perinatal and infant development. Future Child. 2020;30(2):11-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1353/foc.2020.a807759]

6. Racine N, Devereaux C, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Adverse childhood experiences and maternal anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):28. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-020-03017-w]

7. Tacy TA, Kasparian NA, Karnik R, Geiger M, Sood E. Opportunities to enhance parental well-being during prenatal counseling for congenital heart disease. Semin Perinatol. 2022;46(4):151587. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.semperi.2022.151587]

8. Obeagu EI, Chukwu PH. Maternal well-being in the face of hypoxia during pregnancy: A review. Int J Curr Res Chem Pharm Sci. 2024;11(7):25-38. [Link]

9. Modak A, Ronghe V, Gomase KP. The psychological benefits of breastfeeding: Fostering maternal well-being and child development. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e46730. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.46730]

10. Tkáčová H, Makáň F, Králik R. Enhancing educational approaches to mental health for mothers on maternity leave: Insights from Slovakia. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies. Palma: IATED; 2024. p. 1475-81. [Link] [DOI:10.21125/edulearn.2024.0469]

11. Graseck A, Leitner K. Prenatal education in the digital age. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;64(2):345-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000608]

12. Li X, Laplante DP, Paquin V, Lafortune S, Elgbeili G, King S. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for perinatal maternal depression, anxiety and stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;92:102129. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102129]

13. Chehrazi M, Faramarzi M, Abdollahi S, Esfandiari M, Shafie Rizi S. Health promotion behaviours of pregnant women and spiritual well‐being: Mediatory role of pregnancy stress, anxiety and coping ways. Nurs Open. 2021;8(6):3558-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nop2.905]

14. Abera M, Hanlon C, Daniel B, Tesfaye M, Workicho A, Girma T, et al. Effects of relaxation interventions during pregnancy on maternal mental health, and pregnancy and newborn outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19(1):e0278432. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0278432]

15. Tola YO, Akingbade O, Akinwaare MO, Adesuyi EO, Arowosegbe TM, Ndikom CM, et al. Psychoeducation for psychological issues and birth preparedness in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022;2(3):100072. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100072]

16. Frankham LJ, Thorsteinsson EB, Bartik W. Childbirth self-efficacy and birth related PTSD symptoms: An online childbirth education randomised controlled trial for mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24(1):668. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-024-06873-6]

17. Chen Z, Jiang J, Hu T, Luo L, Chen C, Xiang W. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on maternal anxiety, depression, and sleep quality: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2022;101(8):e28849. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000028849]

18. Gargari MA, Esmailpour K, Mirghafourvand M, Nourizadeh R, Mehrabi E. Effects of psycho-education interventions on perceived childbirth fear and anxiety by pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2021;9(4):230-7. [Link] [DOI:10.15296/ijwhr.2021.44]

19. Hall HG, Cant R, Munk N, Carr B, Tremayne A, Weller C, et al. The effectiveness of massage for reducing pregnant women's anxiety and depression; Systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery. 2020;90:102818. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2020.102818]

20. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.n71]

21. Boran P, Dönmez M, Barış E, Us MC, Altaş ZM, Nisar A, et al. Delivering the thinking healthy programme as a universal group intervention integrated into routine antenatal care: A randomized-controlled pilot study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):14. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-022-04499-6]

22. Bowen A, Baetz M, Schwartz L, Balbuena L, Muhajarine N. Antenatal group therapy improves worry and depression symptoms. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2014;51(3):226-31. [Link]

23. Byrne J, Hauck Y, Fisher C, Bayes S, Schutze R. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based childbirth education pilot study on maternal self-efficacy and fear of childbirth. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59(2):192-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jmwh.12075]

24. Cankaya S, Simsek B. Effects of antenatal education on fear of birth, depression, anxiety, childbirth self-efficacy, and mode of delivery in primiparous pregnant women: A prospective randomized controlled study. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(6):818-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1054773820916984]

25. Diotaiuti P, Valente G, Mancone S, Falese L, Corrado S, Siqueira TC, et al. A psychoeducational intervention in prenatal classes: Positive effects on anxiety, self-efficacy, and temporal focus in birth attendants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):7904. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19137904]

26. Gandomi N, Sharifzadeh G, Torshizi M, Norozi E. The effect of educational intervention based on self-efficacy theory on pregnancy anxiety and childbirth outcomes among Iranian primiparous women. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):14. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1548_20]

27. Ghashghaee N, Rezasoltani P, Nazari M, Kazemnezhad Leyli E. Comparison of pregnancy-related concerns, perceived social support, and anxiety between pregnant mothers with and without participation in antenatal education classes. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2024;34(4):365-75. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/jhnm.34.4.2849]

28. Innab A, Al-Khunaizi A, Al-Otaibi A, Moafa H. Effects of mindfulness-based childbirth education on prenatal anxiety: A quasi-experimental study. Acta Psychol. 2023;238:103978. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103978]

29. Madhavan prabhakaran KG, Sheila D'Souza M, Nairy K. Effectiveness of childbirth education on nulliparous women's knowledge of childbirth preparation, pregnancy anxiety and pregnancy outcomes. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2017;6(1). [Link] [DOI:10.5812/nmsjournal.32526]

30. Nikoozad S, Safdari-Dehcheshmeh F, Sharifi F, Ganji F. The effect of prenatal education on health anxiety of primigravid women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24(1):541. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-024-06718-2]

31. Sanaati F, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Farrokh Eslamlo H, Mirghafourvand M, Alizadeh Sharajabad F. The effect of lifestyle-based education to women and their husbands on the anxiety and depression during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(7):870-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2016.1190821]

32. Sercekus P, Baskale H. Effects of antenatal education on fear of childbirth, maternal self-efficacy and parental attachment. Midwifery. 2016;34:166-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2015.11.016]

33. Shen Q, Huang CR, Rong L, Ju S, Redding SR, Ouyang YQ, et al. Effects of needs-based education for prenatal anxiety in advanced multiparas: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):301. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-022-04620-3]

34. Mokhtaryan T, Yazdanpanahi Z, Akbarzadeh M, Amooee S, Zare N. The impact of Islamic religious education on anxiety level in primipara mothers. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5(2):331-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2249-4863.192314]

35. Thomas N, Komiti A, Judd F. Pilot early intervention antenatal group program for pregnant women with anxiety and depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(6):503-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00737-014-0447-2]

36. Xuto P, Toyohiko K, Prasitwattanaseree P, Sriarporn P. Effect of receiving text messages on health care behavior and state anxiety of Thai pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2022;10(1):18-29. [Link]

37. Shi Z, MacBeth A. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on maternal perinatal mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Mindfulness. 2017;8(4):823-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12671-016-0673-y]

38. Matvienko-Sikar K, Lee L, Murphy G, Murphy L. The effects of mindfulness interventions on prenatal well-being: A systematic review. Psychol Health. 2016;31(12):1415-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2016.1220557]

39. Spiby H, Stewart J, Watts K, Hughes AJ, Slade P. The importance of face to face, group antenatal education classes for first time mothers: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2022;109:103295. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2022.103295]

40. Swift EM, Zoega H, Stoll K, Avery M, Gottfreðsdóttir H. Enhanced antenatal care: Combining one-to-one and group antenatal care models to increase childbirth education and address childbirth fear. Women Birth. 2021;34(4):381-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.wombi.2020.06.008]

41. Gluck O, Pinchas‐Cohen T, Hiaev Z, Rubinstein H, Bar J, Kovo M. The impact of childbirth education classes on delivery outcome. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;148(3):300-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ijgo.13016]

42. Dubreucq M, Dupont C, Lambregtse-Van Den Berg MP, Bramer WM, Massoubre C, Dubreucq J. A systematic review of midwives' training needs in perinatal mental health and related interventions. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1345738. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1345738]

43. Van Der Windt M, Van Zundert SKM, Schoenmakers S, Jansen PW, Van Rossem L, Steegers-Theunissen RPM. Effective psychological therapies to improve lifestyle behaviors in (pre) pregnant women: A systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101631. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101631]

44. Rahimnejad A, Davati A, Garshasbi A. Relation between spiritual health and anxiety in pregnant women referred to Shaheed Mostafa Khomeini hospital in 2018. DANESHVAR Med. 2019;27(1):11-8. [Persian] [Link]

45. Shorey S, Ang L, Chee CYI. A systematic mixed-studies review on mindfulness-based childbirth education programs and maternal outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2019;67(6):696-706. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.outlook.2019.05.004]

46. Ahmed MAA, Gagnon MP, Hamelin-Brabant L, Mbemba GIC, Alami H. A mixed methods systematic review of success factors of mhealth and telehealth for maternal health in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mhealth. 2017;3:22. [Link] [DOI:10.21037/mhealth.2017.05.04]

47. Thonon F, Perrot S, Yergolkar AV, Rousset-Torrente O, Griffith JW, Chassany O, et al. Electronic tools to bridge the language gap in health care for people who have migrated: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5):e25131. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/25131]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |