Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 611-616 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Massoodi A, Zavarmousavi S, Moudi S, Alinejad E, Gholinia Ahangar H. Quality of Life in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Influencing Factors and Parental Perspectives. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :611-616

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-77810-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-77810-en.html

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

2- Department of Psychiatry, Shafa Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Student Research Committee, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

4- Clinical Research Development Unit of Rouhani Hospital, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

2- Department of Psychiatry, Shafa Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Student Research Committee, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

4- Clinical Research Development Unit of Rouhani Hospital, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

Keywords: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [MeSH], ADHD [MeSH], Coping Strategies [MeSH], Quality of Life [MeSH], Parents [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 600 kb]

(1580 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (724 Views)

Full-Text: (79 Views)

Introduction

ADHD, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, is recognized as both a neurobiological and neurodevelopmental condition with a distinct genetic basis [1]. Characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, ADHD frequently leads to significant functional impairments that impact daily life [2, 3]. Globally, an estimated 5.3% of children and adolescents are affected by ADHD, with variations in prevalence based on gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity [3]. In Iran, the results of a systematic review study indicated that its prevalence ranges from 2.5% to 14.5%. Boys predominantly exhibit the hyperactive/impulsive subtype of ADHD, whereas girls more commonly show the inattentive subtype, suggesting gender-based differences in symptom presentation [4, 5].

ADHD symptoms in children often lead to challenges that are more disruptive than those associated with other childhood mental health disorders. This disruption places considerable stress on the entire family, as the unique caregiving demands of ADHD require constant attention and adaptation [6]. Parents of children with ADHD often experience heightened levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and other mental health issues [7]. They also face social stigmas and taboos that affect their daily functioning, productivity, and overall mental health. Consequently, these factors may lead to a poor perceived quality of life (QoL) among these parents [7]. Research has consistently shown that parents of children with ADHD endure high levels of stress. This elevated stress not only impacts their own QoL but may also have adverse effects on their children's well-being [8, 9]. Coping strategies are crucial in managing stress and can significantly affect both the parents and children's well-being [10]. The Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) identifies three main coping strategies, including task-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidance-oriented coping. Understanding which strategies parents of children with ADHD predominantly use can provide insights into interventions that may improve the QoL for both parents and children.

Given the high levels of stress that parents of children with ADHD endure and the potential impact on both their own and their child’s QoL, examining the coping strategies these parents use becomes essential. Understanding these mechanisms can inform the development of supportive strategies aimed at enhancing the QoL for both parents and children. By assessing these coping strategies using the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) and evaluating the QoL of children through the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL), we aimed to determine how these factors interrelate from both the parents and children's perspectives. This research is particularly relevant for developing targeted interventions to support families affected by ADHD in Northern Iran. This study, conducted in Northern Iran, will provide valuable insights into the specific challenges and coping strategies in this cultural context, contributing to the broader literature on ADHD and family dynamics. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the connection between the coping strategies parents use to manage stress and how these strategies may influence the QoL experienced by children with ADHD.

Instrument and Methods

Participants and sampling

This cross-sectional analytical study targeted children with ADHD and their parents selected from those attending Babol University of Medical Sciences-affiliated medical centers in 2023. The participants included children aged 8 to 12, diagnosed with ADHD by a child and adolescent psychiatrist according to DSM-5 criteria, along with one of their parents. Both children and parents provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria ruled out participants with developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, psychotic disorders, or bipolar disorder. To detect a minimum correlation of 0.2 between parental stress coping strategies and the children's QoL, a sample size of 220 was calculated, accounting for a 10% anticipated dropout rate. In total, 220 children and one parent from each family participated in the study.

Data collection

Parental coping strategies were assessed using the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations-Short Form (CISS-SF), while the children's quality of life was assessed using the Pediatric QoL Inventory (PedsQL).

Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations-Short Form

To assess stress-coping strategies, the study employed the CISS-SF, developed by Endler and Parker. This inventory categorizes coping into three primary behaviors, namely problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping. Participants rated each of the 21 items on a Likert scale from one (never) to five (very often), with seven questions dedicated to each coping strategy. Specifically, questions 1, 4, 7, 9, 15, 18, and 21 address avoidance coping, questions 2, 6, 8, 11, 13, 16, and 19 assess problem-focused coping, and questions 3, 5, 10, 12, 14, 17, and 20 measure emotion-focused coping. Each strategy has a possible score range from 7 to 35. Previous studies have established the CISS-SF’s high reliability and validity, supporting its use in various contexts [9, 11].

Children's Quality of Life Questionnaire

This scale was used to evaluate the QoL among children aged 8 to 12. Comprising 23 items, each scored on a Likert scale from zero (never) to four (always), the questionnaire provides both a total score and four specific subscale scores, including physical, emotional, social, and academic performance. Additionally, it includes two composite scores for overall psychological and physical health. The reliability and validity of the PedsQL have been well-established in previous research, with Cronbach's alpha indicating strong internal consistency [12].

Data analysis

Using SPSS version 22, descriptive statistics were computed for all study variables. Participant demographics, such as age, gender, and educational level, were presented as means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions. QoL was assessed through multiple dimensions, namely physical and emotional functioning, social and academic performance, as well as mental and physical health. The Wilcoxon test was conducted to compare QoL scores between children and parents. Additionally, an Independent Samples t-test was used to explore associations between stress-coping strategies (CISS-SF; avoidance, problem-focused, and emotion-focused) and the Children's Quality of Life Questionnaire. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the analyses.

Findings

A total of 220 participants took part in the study, of whom 162 (73.6%) were male children, and 34 (15.5%) were male parents. The mean age of the children was 9.39±1.23 years, while the mean age of the parents was 37.22±5.41years. Regarding parents' educational level, 26.4% had a high school education, 30.5% had a diploma, and 43.2% held a university degree.

The mean score for the avoidance strategy was 21.11±3.96 (range=9-34), corresponding to a usage percentage of 60.31%. The problem-oriented strategy had a mean score of 21.71±3.81 (range=9-34) and a usage percentage of 62.02%. The emotional strategy had the highest mean score of 25.71±4.56 (range=13-35) and a usage percentage of 73.45%.

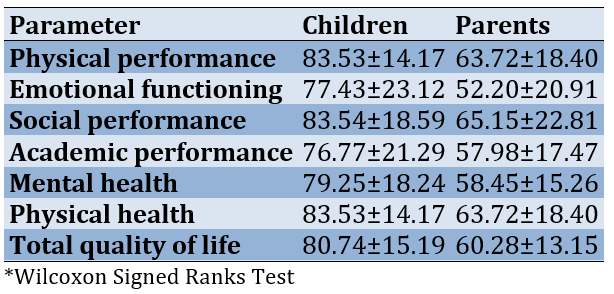

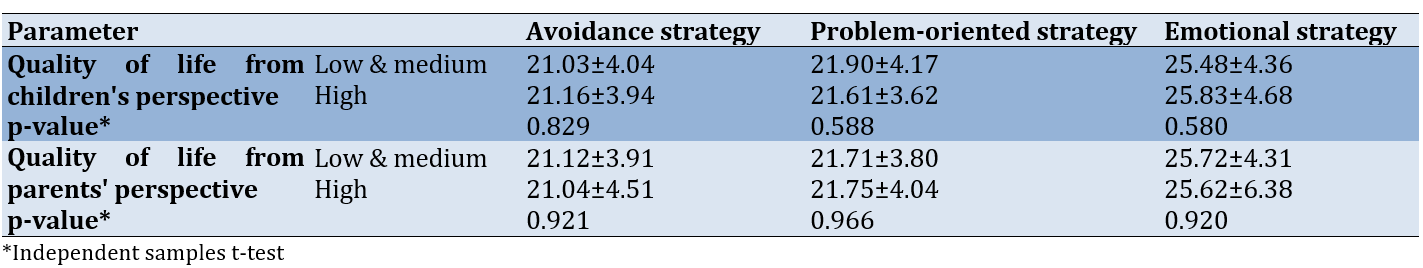

Children reported significantly higher QoL scores than their parents in all measured areas, including physical performance, emotional functioning, social performance, academic performance, and mental health. Each of these differences was highly significant (p-value<0.001) across all domains. For example, children rated their physical health at 83.53±14.17, compared to parents' rating of 63.72±18.40. Overall, children’s total QoL score (80.74±15.19) was significantly higher than parents' assessments (60.28±13.15), highlighting a notable discrepancy in perception (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of quality of life scores of children and their parents across different dimensions

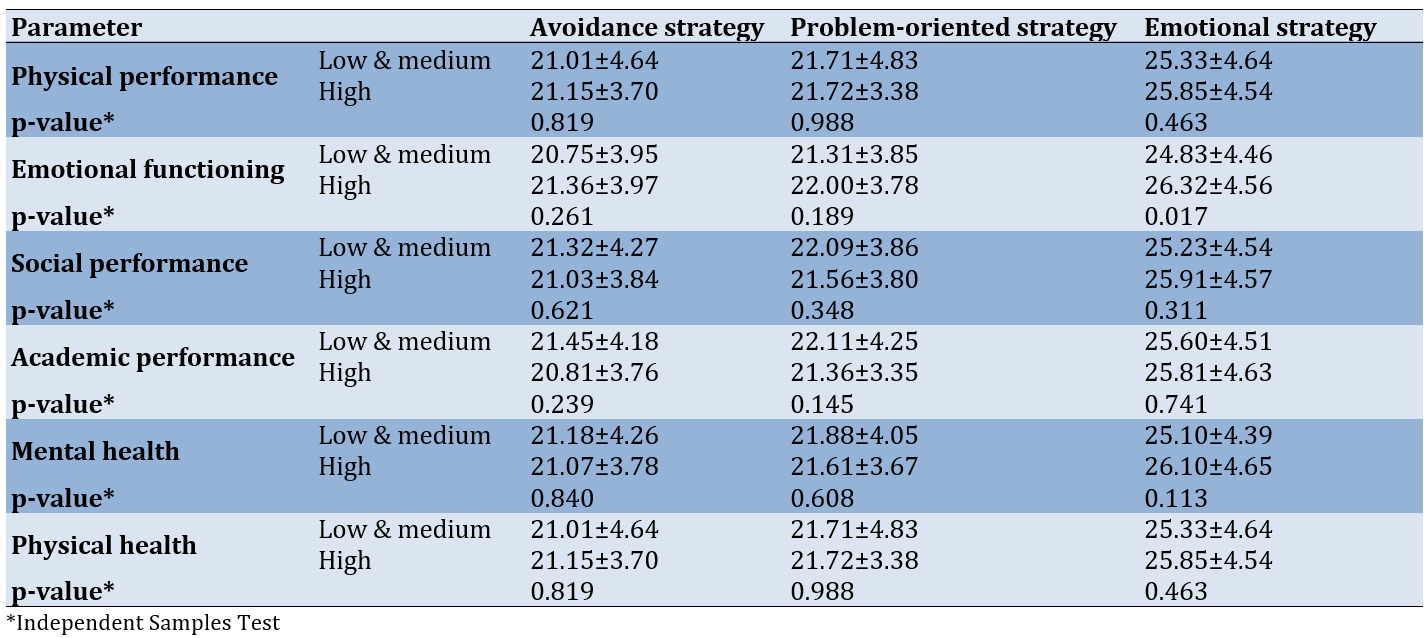

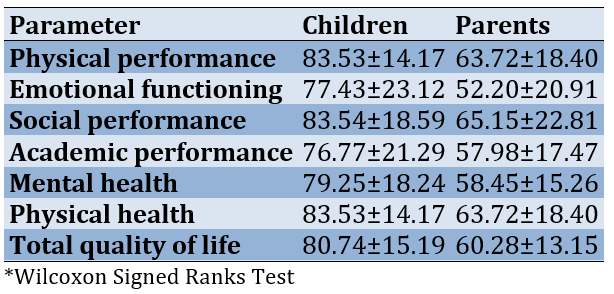

We also examined the connections between different stress coping strategies-such as avoidance, problem-focused, and emotional coping—and various aspects of QoL in children diagnosed with ADHD. Across most dimensions (physical performance, social performance, academic performance, and mental health), no significant differences were observed between groups employing low/medium or high levels of coping strategies (p-value>0.05 for all). However, in the emotional functioning dimension, a significant difference was found for the emotional coping strategy, with children in the high coping group reporting a higher mean score (26.32±4.56) compared to the low and medium coping groups (24.83±4.46) (p-value=0.017). This suggests that emotional coping strategies may play a more pronounced role in improving emotional well-being among children with ADHD, while other coping strategies and QoL dimensions showed no significant statistical impact (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between stress coping strategies and quality of life from children's perspective across different dimensions

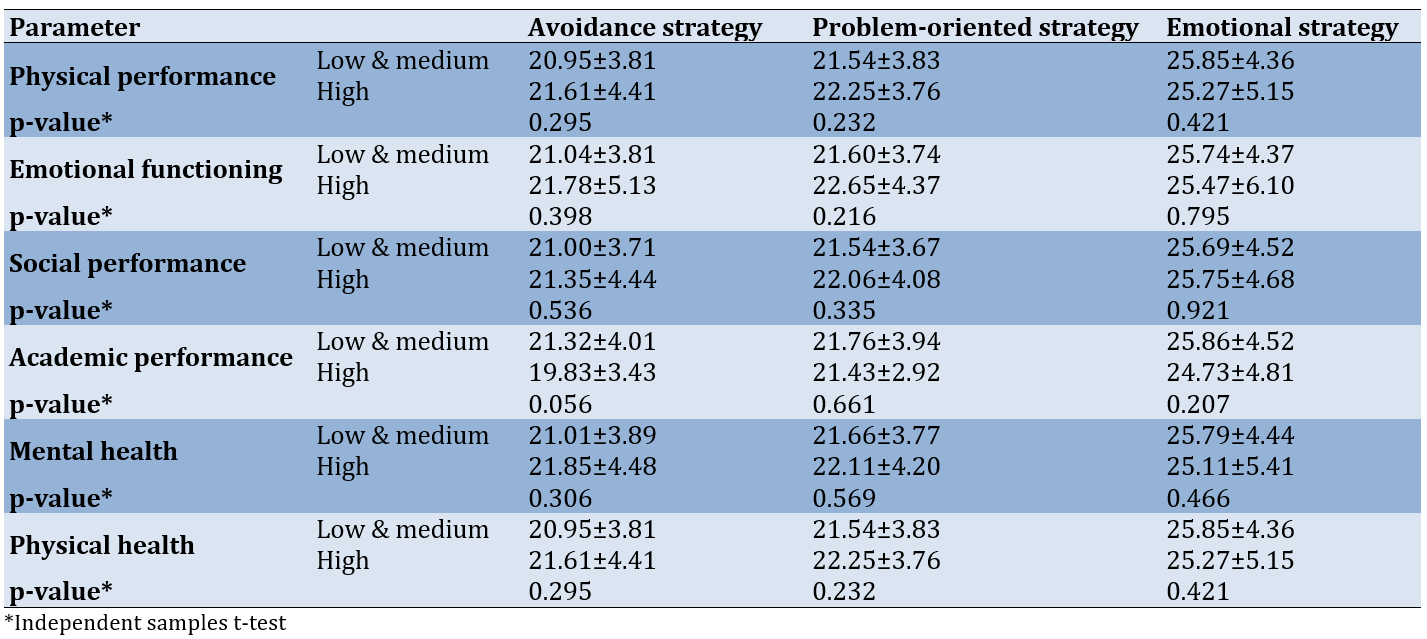

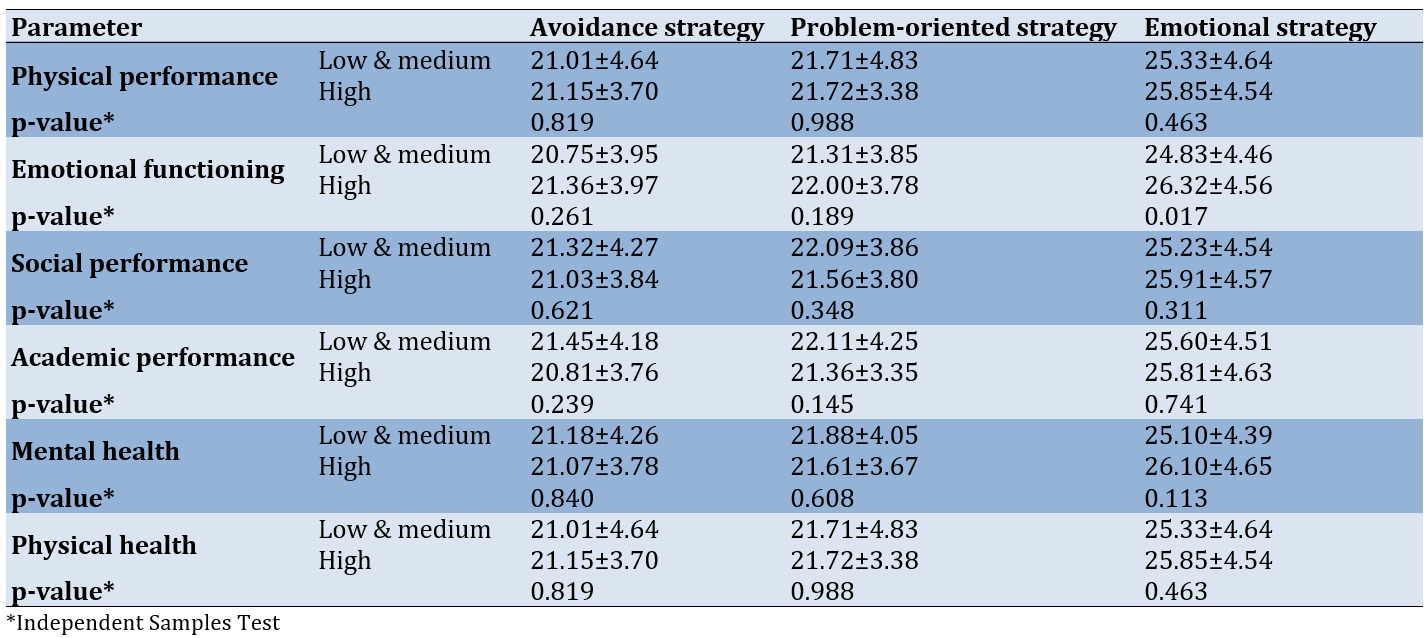

Furthermore, the relationship between stress coping strategies (avoidance, problem-oriented, and emotional) and multiple QoL dimensions for parents of children with ADHD was also evaluated, covering physical, emotional, social, academic, and mental health aspects. The analysis showed no significant differences in coping strategy use between parents with low-to-medium and high perceived QoL. For example, in the physical performance dimension, the mean score for the avoidance strategy was 20.95±3.81 in the low-to-medium group compared to 21.61±4.41 in the high group (p=0.295). Similar non-significant results were observed across other dimensions (p-value>0.05 for all; Table 3).

Table 3. Relationship between stress coping strategies and quality of life from parents' perspective across different dimensions

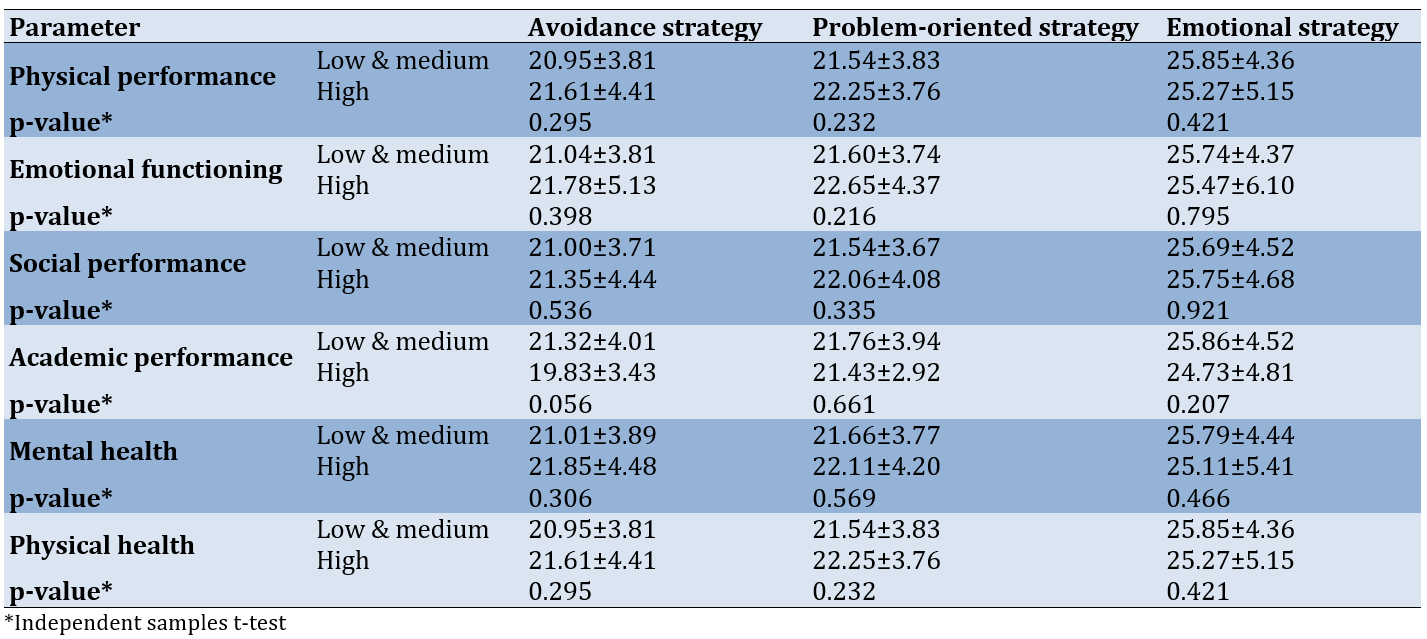

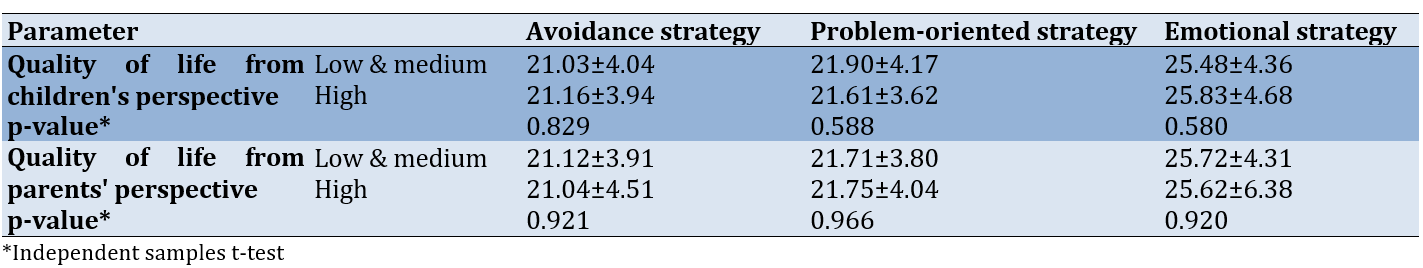

We examined the association between stress coping strategies—namely avoidance, problem-focused, and emotional coping—and the QoL of children with ADHD from both the children’s and parents' perspectives. The analysis revealed no significant differences in coping strategy usage across various QoL categories. For instance, from the children's perspective, the mean score for the avoidance strategy was 21.03±4.04 in the low and medium group, compared to 21.16±3.94 in the high group (p=0.829). Similarly, from the parents' perspective, the avoidance strategy had mean scores of 21.12±3.91 for the low and medium group and 21.04±4.51 for the high group (p=0.921). These findings suggest that coping strategies do not significantly differ between low-to-medium and high QoL groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between stress coping strategies and total quality of life

Discussion

This study examined the link between parental coping strategies and the QoL of children diagnosed with ADHD. Various aspects of QoL were assessed, including physical and emotional functioning, social and academic performance, and overall mental and physical health. The findings provide significant insights into how parental coping mechanisms impact children's well-being. Our results indicated that children with ADHD rated their own QoL higher in all dimensions compared to the ratings given by their parents. This highlights a significant discrepancy, which may be attributable to differing perspectives; children with ADHD often maintain a positive outlook due to their engagement in enjoyable activities, whereas parents tend to focus on the challenges and problems associated with ADHD, such as academic difficulties and behavioral issues. Additionally, this finding could suggest that children may have a better understanding of their abilities and strengths than parents, or that parents may offer a more negative evaluation of their children's QoL due to their own stress and worries. This result may also reflect perceptual differences between children and their parents, emphasizing the need for parents to gain a better understanding of their children's attitudes and feelings. Studies have shown that children and their parents often differ in how they assess QoL, with children typically providing more favorable evaluations of their own QoL compared to their parents' assessments [13-15].

The results showed that parents used more emotional coping strategies than problem-oriented and avoidance strategies. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that parents of children with special needs often resort to more positive and practical coping strategies to deal with stress [14, 16, 17]. Additionally, these results suggest that the emotional coping strategies employed by parents may directly affect the emotional QoL experienced by their children. On the other hand, no statistically significant differences were observed across other QoL dimensions or coping strategies. This may imply that the impact of parents' coping approaches on other aspects of children’s QoL is either less direct, or it may highlight the complex and multidimensional influence of parental coping strategies on their children’s well-being. In line with this, previous research has shown that family QoL is associated with negative emotions, specifically sadness and depression, while adaptive coping strategies are linked to an enhanced quality of family life [10, 18].

From the parents' perspective, no significant relationship was observed between coping strategies and different aspects of children's QoL. This finding may be due to differences in the views and perceptions of parents and children. Additionally, this lack of significance could indicate that parents do not perceive a direct and significant impact of their strategies on the quality of their children's lives, or that these impacts manifest in more complex ways that require further investigation. Previous studies suggest that parenting styles, particularly in terms of emotional support and family dynamics, are influenced by the parent's age and gender. Emotional support from parents is positively linked to control efforts, family cohesion, commitment, and a higher perceived QoL. Conversely, it is negatively associated with male gender, experiences of rejection, and more effective coping strategies [17].

Finally, the total QoL score, from both the children's and parents' perspectives, did not show a statistically significant relationship with parents' coping strategies. This finding suggests that the QoL in children with ADHD is influenced by multiple factors and is not solely dependent on how parents cope. Prior research has similarly shown that the QoL of parents with children with ADHD is often compromised. Factors, such as gender, location, family income, household size, marital status, occupation, and educational level have been associated with lower QoL scores. These findings highlight the need for a comprehensive and multidimensional approach, one that considers the perspectives of the child, parent, and entire family to effectively evaluate QoL in families managing ADHD [18]. To enhance the QoL of these children, there is a need for more comprehensive and multifaceted interventions that include psychological, educational, and social support for both children and parents.

The study's use of validated tools, such as the CISS-SF and the PedsQL ensures the reliability and validity of the collected data. Including perspectives from both parents and children provides a comprehensive understanding of the QoL in families dealing with ADHD. Additionally, the study's significant sample size enhances the generalizability of the findings. However, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality between coping strategies and QoL outcomes. Potential biases in self-report measures could affect the accuracy of the reported data, as parents and children might perceive and report their experiences differently. Moreover, the exclusion of children with certain comorbid conditions (e.g., developmental delays, schizophrenia) may limit the applicability of the findings to all children with ADHD.

Conclusion

Parental coping strategies, particularly those involving emotional support, play a key role in shaping the emotional experiences of children with ADHD.

Acknowledgments: We thank all the participants who cooperated with us in conducting this study.

Ethical Permissions: After receiving approval from the university's research ethics committee, all participants were thoroughly informed of the study’s potential benefits and provided their consent by signing a written form. The confidentiality of all collected data will be strictly upheld. This study was officially registered with the Babol University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee under code IR.MUBABOL.REC.1402.076.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Massoodi A (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Zavarmousavi SM (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (20%); Moudi S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Alinejad E (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Gholinia Ahangar H (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: This research was approved and funded by the Research Vice-Chancellor at Babol University of Medical Sciences, under Grant No. 724134146.

ADHD, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, is recognized as both a neurobiological and neurodevelopmental condition with a distinct genetic basis [1]. Characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, ADHD frequently leads to significant functional impairments that impact daily life [2, 3]. Globally, an estimated 5.3% of children and adolescents are affected by ADHD, with variations in prevalence based on gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity [3]. In Iran, the results of a systematic review study indicated that its prevalence ranges from 2.5% to 14.5%. Boys predominantly exhibit the hyperactive/impulsive subtype of ADHD, whereas girls more commonly show the inattentive subtype, suggesting gender-based differences in symptom presentation [4, 5].

ADHD symptoms in children often lead to challenges that are more disruptive than those associated with other childhood mental health disorders. This disruption places considerable stress on the entire family, as the unique caregiving demands of ADHD require constant attention and adaptation [6]. Parents of children with ADHD often experience heightened levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and other mental health issues [7]. They also face social stigmas and taboos that affect their daily functioning, productivity, and overall mental health. Consequently, these factors may lead to a poor perceived quality of life (QoL) among these parents [7]. Research has consistently shown that parents of children with ADHD endure high levels of stress. This elevated stress not only impacts their own QoL but may also have adverse effects on their children's well-being [8, 9]. Coping strategies are crucial in managing stress and can significantly affect both the parents and children's well-being [10]. The Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) identifies three main coping strategies, including task-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidance-oriented coping. Understanding which strategies parents of children with ADHD predominantly use can provide insights into interventions that may improve the QoL for both parents and children.

Given the high levels of stress that parents of children with ADHD endure and the potential impact on both their own and their child’s QoL, examining the coping strategies these parents use becomes essential. Understanding these mechanisms can inform the development of supportive strategies aimed at enhancing the QoL for both parents and children. By assessing these coping strategies using the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) and evaluating the QoL of children through the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL), we aimed to determine how these factors interrelate from both the parents and children's perspectives. This research is particularly relevant for developing targeted interventions to support families affected by ADHD in Northern Iran. This study, conducted in Northern Iran, will provide valuable insights into the specific challenges and coping strategies in this cultural context, contributing to the broader literature on ADHD and family dynamics. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the connection between the coping strategies parents use to manage stress and how these strategies may influence the QoL experienced by children with ADHD.

Instrument and Methods

Participants and sampling

This cross-sectional analytical study targeted children with ADHD and their parents selected from those attending Babol University of Medical Sciences-affiliated medical centers in 2023. The participants included children aged 8 to 12, diagnosed with ADHD by a child and adolescent psychiatrist according to DSM-5 criteria, along with one of their parents. Both children and parents provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria ruled out participants with developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, psychotic disorders, or bipolar disorder. To detect a minimum correlation of 0.2 between parental stress coping strategies and the children's QoL, a sample size of 220 was calculated, accounting for a 10% anticipated dropout rate. In total, 220 children and one parent from each family participated in the study.

Data collection

Parental coping strategies were assessed using the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations-Short Form (CISS-SF), while the children's quality of life was assessed using the Pediatric QoL Inventory (PedsQL).

Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations-Short Form

To assess stress-coping strategies, the study employed the CISS-SF, developed by Endler and Parker. This inventory categorizes coping into three primary behaviors, namely problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping. Participants rated each of the 21 items on a Likert scale from one (never) to five (very often), with seven questions dedicated to each coping strategy. Specifically, questions 1, 4, 7, 9, 15, 18, and 21 address avoidance coping, questions 2, 6, 8, 11, 13, 16, and 19 assess problem-focused coping, and questions 3, 5, 10, 12, 14, 17, and 20 measure emotion-focused coping. Each strategy has a possible score range from 7 to 35. Previous studies have established the CISS-SF’s high reliability and validity, supporting its use in various contexts [9, 11].

Children's Quality of Life Questionnaire

This scale was used to evaluate the QoL among children aged 8 to 12. Comprising 23 items, each scored on a Likert scale from zero (never) to four (always), the questionnaire provides both a total score and four specific subscale scores, including physical, emotional, social, and academic performance. Additionally, it includes two composite scores for overall psychological and physical health. The reliability and validity of the PedsQL have been well-established in previous research, with Cronbach's alpha indicating strong internal consistency [12].

Data analysis

Using SPSS version 22, descriptive statistics were computed for all study variables. Participant demographics, such as age, gender, and educational level, were presented as means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions. QoL was assessed through multiple dimensions, namely physical and emotional functioning, social and academic performance, as well as mental and physical health. The Wilcoxon test was conducted to compare QoL scores between children and parents. Additionally, an Independent Samples t-test was used to explore associations between stress-coping strategies (CISS-SF; avoidance, problem-focused, and emotion-focused) and the Children's Quality of Life Questionnaire. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the analyses.

Findings

A total of 220 participants took part in the study, of whom 162 (73.6%) were male children, and 34 (15.5%) were male parents. The mean age of the children was 9.39±1.23 years, while the mean age of the parents was 37.22±5.41years. Regarding parents' educational level, 26.4% had a high school education, 30.5% had a diploma, and 43.2% held a university degree.

The mean score for the avoidance strategy was 21.11±3.96 (range=9-34), corresponding to a usage percentage of 60.31%. The problem-oriented strategy had a mean score of 21.71±3.81 (range=9-34) and a usage percentage of 62.02%. The emotional strategy had the highest mean score of 25.71±4.56 (range=13-35) and a usage percentage of 73.45%.

Children reported significantly higher QoL scores than their parents in all measured areas, including physical performance, emotional functioning, social performance, academic performance, and mental health. Each of these differences was highly significant (p-value<0.001) across all domains. For example, children rated their physical health at 83.53±14.17, compared to parents' rating of 63.72±18.40. Overall, children’s total QoL score (80.74±15.19) was significantly higher than parents' assessments (60.28±13.15), highlighting a notable discrepancy in perception (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of quality of life scores of children and their parents across different dimensions

We also examined the connections between different stress coping strategies-such as avoidance, problem-focused, and emotional coping—and various aspects of QoL in children diagnosed with ADHD. Across most dimensions (physical performance, social performance, academic performance, and mental health), no significant differences were observed between groups employing low/medium or high levels of coping strategies (p-value>0.05 for all). However, in the emotional functioning dimension, a significant difference was found for the emotional coping strategy, with children in the high coping group reporting a higher mean score (26.32±4.56) compared to the low and medium coping groups (24.83±4.46) (p-value=0.017). This suggests that emotional coping strategies may play a more pronounced role in improving emotional well-being among children with ADHD, while other coping strategies and QoL dimensions showed no significant statistical impact (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between stress coping strategies and quality of life from children's perspective across different dimensions

Furthermore, the relationship between stress coping strategies (avoidance, problem-oriented, and emotional) and multiple QoL dimensions for parents of children with ADHD was also evaluated, covering physical, emotional, social, academic, and mental health aspects. The analysis showed no significant differences in coping strategy use between parents with low-to-medium and high perceived QoL. For example, in the physical performance dimension, the mean score for the avoidance strategy was 20.95±3.81 in the low-to-medium group compared to 21.61±4.41 in the high group (p=0.295). Similar non-significant results were observed across other dimensions (p-value>0.05 for all; Table 3).

Table 3. Relationship between stress coping strategies and quality of life from parents' perspective across different dimensions

We examined the association between stress coping strategies—namely avoidance, problem-focused, and emotional coping—and the QoL of children with ADHD from both the children’s and parents' perspectives. The analysis revealed no significant differences in coping strategy usage across various QoL categories. For instance, from the children's perspective, the mean score for the avoidance strategy was 21.03±4.04 in the low and medium group, compared to 21.16±3.94 in the high group (p=0.829). Similarly, from the parents' perspective, the avoidance strategy had mean scores of 21.12±3.91 for the low and medium group and 21.04±4.51 for the high group (p=0.921). These findings suggest that coping strategies do not significantly differ between low-to-medium and high QoL groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between stress coping strategies and total quality of life

Discussion

This study examined the link between parental coping strategies and the QoL of children diagnosed with ADHD. Various aspects of QoL were assessed, including physical and emotional functioning, social and academic performance, and overall mental and physical health. The findings provide significant insights into how parental coping mechanisms impact children's well-being. Our results indicated that children with ADHD rated their own QoL higher in all dimensions compared to the ratings given by their parents. This highlights a significant discrepancy, which may be attributable to differing perspectives; children with ADHD often maintain a positive outlook due to their engagement in enjoyable activities, whereas parents tend to focus on the challenges and problems associated with ADHD, such as academic difficulties and behavioral issues. Additionally, this finding could suggest that children may have a better understanding of their abilities and strengths than parents, or that parents may offer a more negative evaluation of their children's QoL due to their own stress and worries. This result may also reflect perceptual differences between children and their parents, emphasizing the need for parents to gain a better understanding of their children's attitudes and feelings. Studies have shown that children and their parents often differ in how they assess QoL, with children typically providing more favorable evaluations of their own QoL compared to their parents' assessments [13-15].

The results showed that parents used more emotional coping strategies than problem-oriented and avoidance strategies. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that parents of children with special needs often resort to more positive and practical coping strategies to deal with stress [14, 16, 17]. Additionally, these results suggest that the emotional coping strategies employed by parents may directly affect the emotional QoL experienced by their children. On the other hand, no statistically significant differences were observed across other QoL dimensions or coping strategies. This may imply that the impact of parents' coping approaches on other aspects of children’s QoL is either less direct, or it may highlight the complex and multidimensional influence of parental coping strategies on their children’s well-being. In line with this, previous research has shown that family QoL is associated with negative emotions, specifically sadness and depression, while adaptive coping strategies are linked to an enhanced quality of family life [10, 18].

From the parents' perspective, no significant relationship was observed between coping strategies and different aspects of children's QoL. This finding may be due to differences in the views and perceptions of parents and children. Additionally, this lack of significance could indicate that parents do not perceive a direct and significant impact of their strategies on the quality of their children's lives, or that these impacts manifest in more complex ways that require further investigation. Previous studies suggest that parenting styles, particularly in terms of emotional support and family dynamics, are influenced by the parent's age and gender. Emotional support from parents is positively linked to control efforts, family cohesion, commitment, and a higher perceived QoL. Conversely, it is negatively associated with male gender, experiences of rejection, and more effective coping strategies [17].

Finally, the total QoL score, from both the children's and parents' perspectives, did not show a statistically significant relationship with parents' coping strategies. This finding suggests that the QoL in children with ADHD is influenced by multiple factors and is not solely dependent on how parents cope. Prior research has similarly shown that the QoL of parents with children with ADHD is often compromised. Factors, such as gender, location, family income, household size, marital status, occupation, and educational level have been associated with lower QoL scores. These findings highlight the need for a comprehensive and multidimensional approach, one that considers the perspectives of the child, parent, and entire family to effectively evaluate QoL in families managing ADHD [18]. To enhance the QoL of these children, there is a need for more comprehensive and multifaceted interventions that include psychological, educational, and social support for both children and parents.

The study's use of validated tools, such as the CISS-SF and the PedsQL ensures the reliability and validity of the collected data. Including perspectives from both parents and children provides a comprehensive understanding of the QoL in families dealing with ADHD. Additionally, the study's significant sample size enhances the generalizability of the findings. However, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality between coping strategies and QoL outcomes. Potential biases in self-report measures could affect the accuracy of the reported data, as parents and children might perceive and report their experiences differently. Moreover, the exclusion of children with certain comorbid conditions (e.g., developmental delays, schizophrenia) may limit the applicability of the findings to all children with ADHD.

Conclusion

Parental coping strategies, particularly those involving emotional support, play a key role in shaping the emotional experiences of children with ADHD.

Acknowledgments: We thank all the participants who cooperated with us in conducting this study.

Ethical Permissions: After receiving approval from the university's research ethics committee, all participants were thoroughly informed of the study’s potential benefits and provided their consent by signing a written form. The confidentiality of all collected data will be strictly upheld. This study was officially registered with the Babol University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee under code IR.MUBABOL.REC.1402.076.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Massoodi A (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Zavarmousavi SM (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (20%); Moudi S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Alinejad E (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Gholinia Ahangar H (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: This research was approved and funded by the Research Vice-Chancellor at Babol University of Medical Sciences, under Grant No. 724134146.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Quality of Life

Received: 2024/11/3 | Accepted: 2024/12/6 | Published: 2024/12/10

Received: 2024/11/3 | Accepted: 2024/12/6 | Published: 2024/12/10

References

1. Hamidi F, Mohammadi F, Paydar F. Effect of parents cognitive-behavioral group counseling on learning problems and anxiety of ADHD students in primary schools. Health Educ Health Promot. 2020;8(1):5-11. [Link]

2. Shafiullah S, Dhaneshwar S. Current perspectives on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Curr Mol Med. 2023. [Link]

3. Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):434-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ije/dyt261]

4. Shooshtary MH, Chimeh N, Najafi M, Mohamadi MR, Yousefi-Nouraie R, Rahimi-Mvaghar A. The prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Iran: A systematic review. Iran J Psychiatry. 2010;5(3):88-92. [Link]

5. Hamidi F, Rezaei S. Cognitive effectiveness of auditory and visual memory on improving cognitive flexibility in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Health Educ Health Promot. 2020;8(3):125-33. [Link]

6. Ching'oma CD, Mkoka DA, Ambikile JS, Iseselo MK. Experiences and challenges of parents caring for children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative study in Dar es salaam, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0267773. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0267773]

7. Kumar K, Sharma R, Saini L, Shah R, Sharma A, Mehra A. Personification of stress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life, among parents of attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder children. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;38(2):137-42. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_116_20]

8. Dardas LA. Stress, coping strategies, and quality of life among Jordanian parents of children with autistic disorder. Autism. 2014;4(1):127. [Link]

9. Galloway H, Newman E, Miller N, Yuill C. Does parent stress predict the quality of life of children with a diagnosis of ADHD? A comparison of parent and child perspectives. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(5):435-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1087054716647479]

10. Predescu E, Sipos R. Cognitive coping strategies, emotional distress and quality of life in mothers of children with ASD and ADHD-A comparative study in a Romanian population sample. Open J Psychiatry. 2013;3(2A):11-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4236/ojpsych.2013.32A003]

11. Ghoreyshi Rad F. Validation of endler & parker coping scale of stressful situations. Int J Behav Sci. 2010;4(1):1-7. [Persian] [Link]

12. Mohamadian H, Akbari H, Gilasi H, Gharlipour Z, Moazami A, Aghajani M, et al. Validation of pediatric quality of life questionnaire (PedsQL) in Kashan city. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2014;22(3):10-8. [Persian] [Link]

13. Coghill D. ADHD impairs quality of life, but children and young people with ADHD perceive less impairment than parents. Evid Based Ment Health. 2010;13(3):76. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/ebmh.13.3.76]

14. Galloway H, Newman E. Is there a difference between child self-ratings and parent proxy-ratings of the quality of life of children with a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? A systematic review of the literature. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9(1):11-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12402-016-0210-9]

15. Cortese S. Review: ADHD impairs quality of life, but children and young people with ADHD perceive less impairment than parents. Evid Based Ment Health. 2010;13(3):76. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/ebmh.13.3.76]

16. Arif A, Ashraf F, Nusrat A. Stress and coping strategies in parents of children with special needs. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(5):1369-72. [Link] [DOI:10.47391/JPMA.1069]

17. Gaspar T, Cerqueira A, Botelho Guedes F, Matos M. Parental emotional support, family functioning and children's quality of life. Psychol Stud. 2022;67(2):189-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12646-022-00652-z]

18. Nath MC, Morshed NM, Zohra F, Nath MC, Dutta BK, Pal BC, et al. Assessment of quality of life in parents of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) children at a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh. J Psychiatry Psychiatr Disord. 2022;6(3):128-41. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |