Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 675-682 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hosseini Moghadam S, Babaie M, Nourian M, Mahdavi M, Nasiri M, Varzeshnejad M. Impact of Tele-Nursing on Adherence to Treatment Regimen and Quality of Life in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Heart Transplantation Surgery. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :675-682

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-77686-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-77686-en.html

1- “Student Research Committee” and “Department of Pediatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Anesthesiology, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

3- Department of Pediatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Heart Research Center, Shaheed Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center, Tehran, Iran

5- Department of Biostatistics, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Anesthesiology, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

3- Department of Pediatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Heart Research Center, Shaheed Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center, Tehran, Iran

5- Department of Biostatistics, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Treatment Adherence [MeSH], Heart Transplantation [MeSH], Children [MeSH], Telenursing [MeSH], Quality of Life [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 619 kb]

(1655 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (572 Views)

Full-Text: (50 Views)

Introduction

Heart transplantation is a critical surgical intervention for patients with medically refractory heart failure and life-threatening cardiac conditions, with approximately 3,500 procedures performed annually worldwide [1, 2]. Post-transplant survival rates have improved significantly, with pediatric patients accounting for approximately 14% of these surgeries [3, 4]. This procedure is particularly essential for children suffering from congenital diseases, valvular heart disorders, and cardiomyopathies that are unresponsive to conventional treatments [5]. However, heart transplantation profoundly impacts the lives of these children and their families, making it crucial to prioritize both survival and quality of life [6].

Post-transplant, patients are prescribed immunosuppressive regimens, including calcineurin inhibitors, azathioprine, everolimus, and corticosteroids, to reduce the risk of rejection [7]. Research highlights various cognitive and developmental challenges experienced by children and adolescents following transplantation, often associated with factors such as reduced cerebral perfusion [8]. A study conducted in Iran reported a 50% five-year survival rate among heart transplant recipients, with some patients surviving up to 25 years post-surgery [9]. Evidence suggests a direct relationship between treatment adherence and survival rates, indicating that compliance significantly enhances outcomes [1, 3, 4].

To improve survival rates, healthcare teams focus on enhancing quality of life and preventing adverse physical, psychological, and social effects. Treatment adherence is crucial for both quality of life and survival among pediatric heart transplant recipients [3, 4]. The quality of life in patients with heart transplants is affected by their adherence to the treatment regimen. Chronic illnesses, including heart transplantation in children, have consequences across physical, psychological, social, educational, and occupational dimensions. Despite increased survival rates, these children may not have a satisfactory quality of life [4]. Non-adherence can lead to severe consequences, including increased healthcare costs, frequent hospitalizations, transplant rejection, and even mortality [10].

Research indicates that treatment adherence significantly influences the survival rates of pediatric heart transplant recipients, highlighting an area that requires further exploration. Treatment adherence also has a reciprocal relationship with the quality of life in these children, emphasizing the need for effective follow-up strategies [4, 11]. Key strategies include regular follow-up visits, capacity-building initiatives, social support, and continuous education by the childcare team [12]. Innovative approaches, such as communication technologies, are increasingly empowering individuals with chronic health conditions. The rise of tele-nursing, particularly in Iran, holds great promise, with studies showing improved self-care through mobile communication platforms and social media [13-15].

However, limited studies have examined the use of tele-nursing among pediatric and adolescent populations. Most existing research has primarily focused on a narrow range of conditions, such as common acute illnesses (e.g., respiratory infections, minor injuries) or chronic conditions like asthma. These studies often rely on cross-sectional data and focus on immediate outcomes rather than long-term efficacy and impact. Populations, such as children with severe chronic illnesses may require tailored tele-nursing approaches [16, 17]. Current research does not sufficiently address how tele-nursing services can be adapted to meet the specific needs of such vulnerable populations. Understanding how tele-nursing can cater to these unique requirements is essential to promote health equity and ensure that all children receive appropriate healthcare services.

Enhancing quality of life and improving treatment adherence among pediatric heart transplant recipients are fundamental nursing responsibilities. Despite the growing body of knowledge, researchers have identified a gap in studies conducted in Iran regarding the impact of tele-nursing on pediatric heart transplant recipients. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of a supportive tele-educational program on treatment adherence and quality of life in children aged 12-18 years.

Materials and Methods

Design

This quasi-experimental single-group study was conducted on children undergoing heart transplantation surgery from October 1 to December 1, 2022, in Tehran, Iran.

Setting

The study was conducted at Shahid Rajaei Heart Hospital, the largest specialized and subspecialized center for heart surgeries in Tehran, where patients requiring heart transplantation surgery are referred. A total of 41 children aged 12 to 18 years, who had undergone heart transplantation surgery at Shahid Rajaei Heart Hospital, were selected through a convenient and comprehensive sampling method.

Participants

The inclusion criteria encompassed children aged 12-18 years who had undergone heart transplantation surgery within the past five years and whose health status was actively monitored at Shahid Rajaei Hospital during the study period. Additional criteria included the willingness of both parents and children to participate, the ability to speak Persian, the absence of mental disorders and sensory impairments, and access to a mobile phone capable of supporting communication programs. Eligible participants had undergone heart transplantation surgery between 6 months and five years prior to the study. Exclusion criteria applied to participants who were re-hospitalized for any reason during the intervention period or who experienced a stressful event, such as the death of a parent.

First, a list of patients was compiled. Of the 50 patients on the list, 41 met the inclusion criteria. Since the sampling for this research was conducted in an educational and treatment hospital in Tehran, Iran, and considering the possibility of sample dropouts, participants were selected using census sampling.

Procedures and interventions

The researcher, in coordination with the hospital’s archive department, prepared a list of eligible children for participation in the study, including their names and contact information. The parents of the children were contacted by phone to explain the purpose, objectives, and implementation of the study. After obtaining consent from both the parents and the children, they were invited to attend an introductory session, sign a written consent form, and receive general guidance on accessing tele-education and nursing care at the hospital. During the face-to-face session, the objectives and implementation methods of the plan were reviewed, and written consent was obtained from both the legal guardian and the child. It was also made clear that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they wished.

The educational and supportive content was divided into two parts. The content was balanced and free from bias, and causal connections between statements were clearly established.

Part one: This section included a general overview where participants received an audiovisual file and text-based instructional material. The language used was clear, concise, and objective, with a formal tone and precise word choice. The text adhered to conventional structure and formatting guidelines, with consistent citation and footnote styles. It was grammatically correct and free from spelling and punctuation errors. No changes were made to the content, except for improvements to meet the desired characteristics. This program covered the medication regimen, dietary regimen, physical activity, social participation and interaction, mental health, and motivation. The educational content was developed, validated, and confirmed through a review of relevant texts and feedback from professors at the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the Educational Research and Treatment Center for Cardiovascular Diseases at Shahid Rajaei Heart Hospital, and the research team.

Part two: Since the children had undergone transplantation surgeries at different times, ranging from six months to five years ago, they had varying informational and psychological needs. Therefore, the researcher prepared a checklist to identify the unique needs of each child and their family. The checklist was developed by reviewing relevant texts, using questionnaires, obtaining feedback from professors, and surveying and conducting brief interviews with several families whose children had undergone heart transplantation surgery.

The parents chose communication software, including WhatsApp, Skype, and Telegram, to interact with families and provide educational content. Telephone calls were made every other day for eight weeks to follow up and answer questions from both parents and children. All children actively participated in the program throughout the intervention. Information was provided in various formats, including audio files, visual materials, and videos, as well as through telephone communication. The study involved a WhatsApp group consisting of all participating children. A daily topic for discussion was raised, allowing the children to interact and discuss self-care management. The participants completed the study questionnaires online twice; once before the start of the intervention and again at the end of the eight-week intervention period.

Outcome measure

The study aimed to evaluate the level of adherence to the treatment regimen and the quality of life in adolescents who underwent heart transplantation.

Data collection tools

1- Demographic Questionnaire for Children and Parents: This questionnaire covered gender, age, number of siblings, birth order, presence of other chronic diseases, frequency of hospitalizations, time of transplantation, parents' age and education, place of residence, and socioeconomic status.

2- The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ 3.0 Cardiac Module 16 (PedsQL™ 3.0 Cardiac Module): This scale is a specific tool used to measure health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with heart disease. The language used is clear, concise, and objective, with technical terms explained when first introduced. No changes in content have been made. The tool consists of 27 items across six dimensions, including heart problems (seven items), treatment (five items), perceived physical appearance (three items), treatment anxiety (four items), cognitive problems (five items), and communication (three items). The scoring system for quality of life is based on a five-point Likert scale (zero=never, one=rarely, two=sometimes, three=often, four=almost always). The items are reverse-scored and linearly transformed to a scale of 0 to 100 (zero=100, one=75, two=50, three=25, and four=0), with higher scores indicating worse quality of life. The total score is calculated as the sum of all items. This tool was translated and validated in Persian by Noori et al. The internal consistency was confirmed using Cronbach's alpha, which was reported as 0.87 [18]. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha was recalculated using all the samples and found to be 0.89.

3- Modanloo Medication Adherence Questionnaire for Chronic Patients: Modanloo [19] designed and validated the medication adherence questionnaire for chronic patients. The questionnaire was created to assess medication adherence. The language used is clear, concise, and objective, with technical terms applied consistently throughout. The text is free from grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. The questionnaire consists of 40 items and subscales, including compliance with treatment (nine items), willingness to participate in treatment (seven items), ability to adapt (seven items), integration of treatment into life (five items), adherence to treatment (four items), commitment to treatment (five items), and management in treatment execution (three items). The text follows a conventional academic structure and formatting, with clear section headings and citations. The tool measures compliance with treatment, willingness to participate in treatment, ability to adapt, integration of treatment into life, adherence to treatment, commitment to treatment, and management in treatment execution. Scores range from 0 to 45 for compliance, 0 to 35 for willingness, 0 to 35 for adaptability, 0 to 25 for integration, 0 to 20 for adherence, 0 to 25 for commitment, and 0 to 15 for management. Higher scores indicate better adherence to treatment. The developers confirmed the content validity of this tool. The tool's reliability was reported as 0.875 using the test-retest method [19]. In this study, we re-evaluated the tool's reliability using the test-retest method on 10 adolescents who were not part of the sample (r=0.88).

Data analysis

SPSS version 16 software was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were employed to present the demographic characteristics and mean scores of quality of life and treatment adherence. The normal distribution of parameters was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The mean scores for quality of life and treatment adherence were compared at two time points (before and after the intervention) using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A paired t-test was used to compare the mean scores of quality of life and treatment adherence before and after the intervention. Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between demographic parameters and treatment adherence or quality of life.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Findings

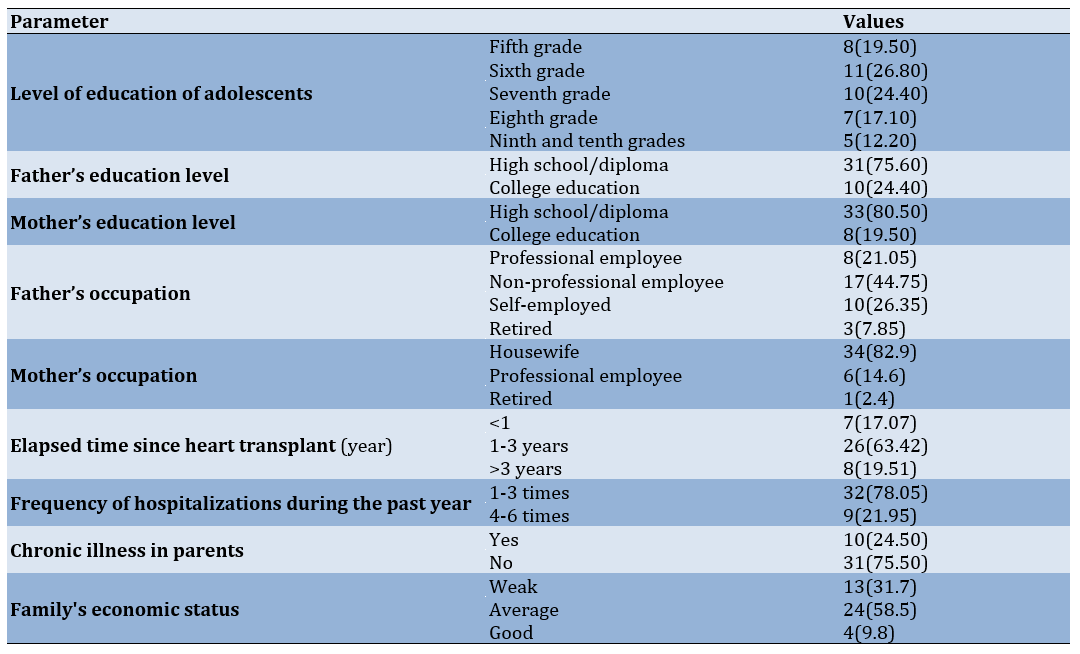

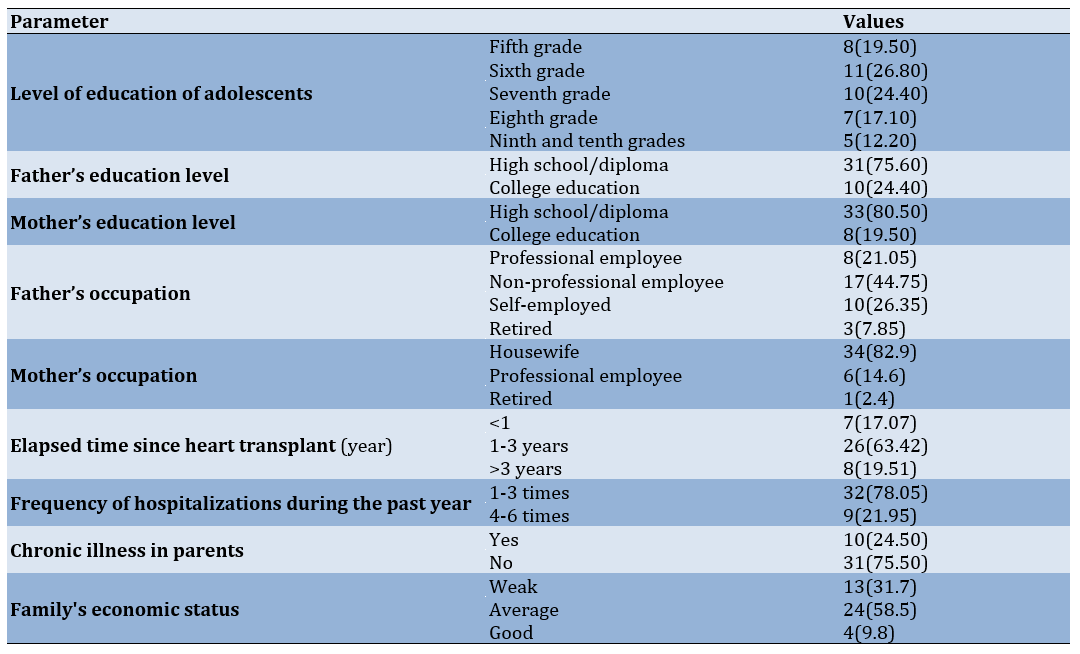

The study participants had a mean age of 12.66±2.29 years, with 51.2% being girls. The majority of participants (26.80%) were in the sixth grade, and 26.80% did not have any other chronic diseases. Three fathers had previously passed away. The majority of fathers (75.60%) had less than a diploma, while the majority of mothers (80.50%) had a diploma. The age range of mothers was between 31 and 54 years, while for fathers, it was between 36 and 64 years. In 73.2% of cases, mothers were the primary caregivers (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n=41)

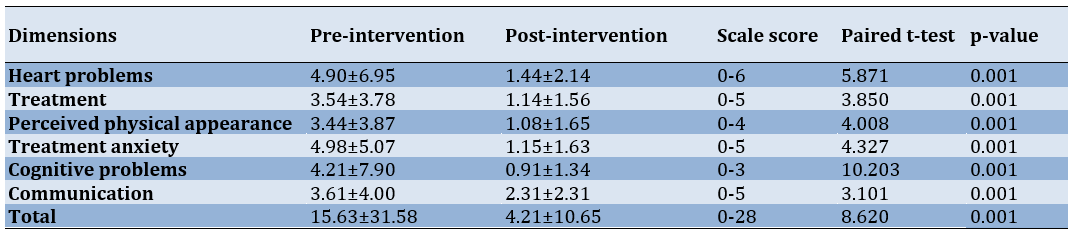

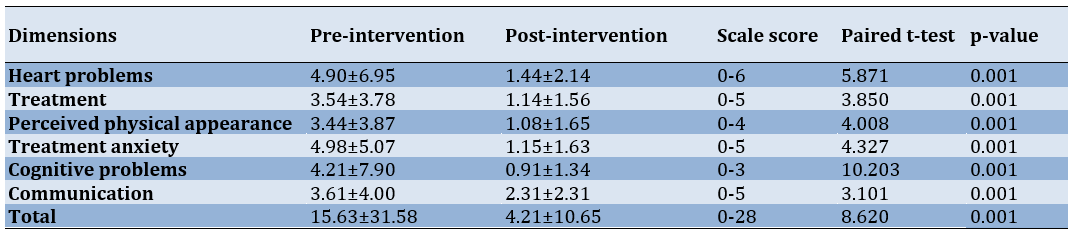

The lowest mean was observed post-treatment, with a mean of 44.3±78.3, while the highest mean was related to cognitive problems post-treatment, with a mean of 21.4±90.7. The mean quality of life before the intervention was 58.31±15.63. After the intervention, the mean quality of life was 10.65±21.4. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory results showed that the lowest mean score was associated with cognitive problems post-treatment, with a mean of 34.1±91.0, while the highest mean score was related to communication problems post-treatment, with a mean of 31.2±31.2. A lower score on the questionnaire indicated a higher quality of life. Furthermore, the paired t-test results indicated a significant difference in quality of life and its dimensions after the intervention compared to before the intervention (p<0.001; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the average score of quality of life in participants before and after the intervention

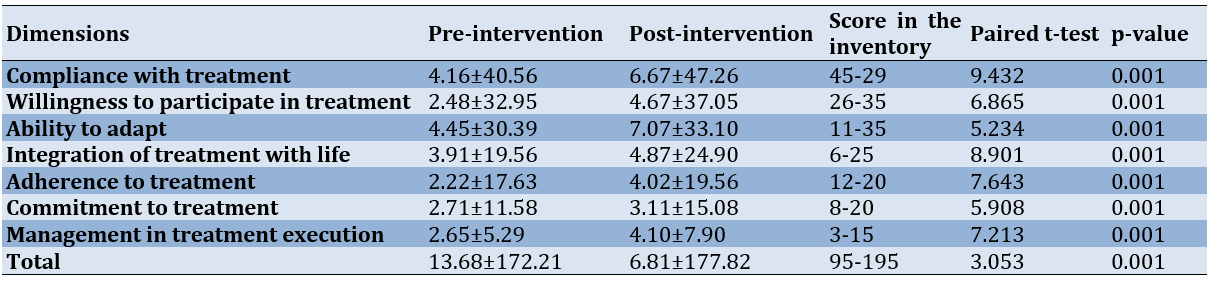

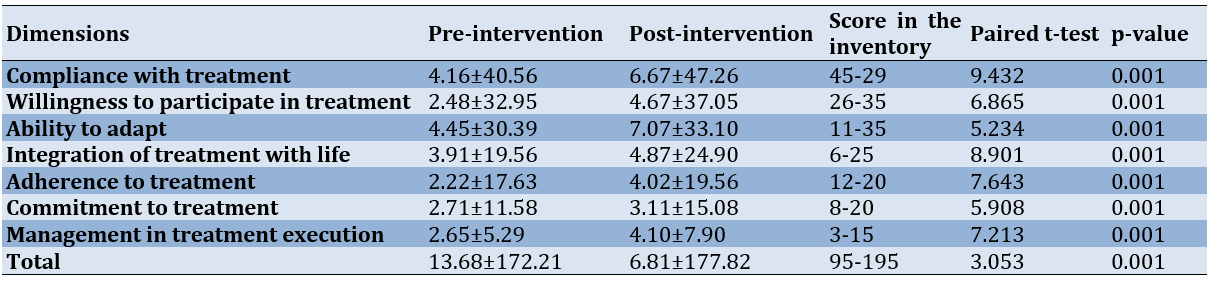

Before the intervention, treatment adherence had a mean of 21.17±13.68. The lowest mean was related to treatment implementation post-treatment, with a mean of 29.5±65.2, and the highest mean was related to adherence to treatment post-treatment, with a mean of 40.56±16.40. After the intervention, treatment adherence had a mean of 82.18±81.60. The study found that the lowest mean score was associated with treatment implementation post-treatment (90.7±10.4), while the highest mean score was associated with adherence to treatment post-treatment (47.56±67.60). The results of the paired t-test indicated a significant difference in adherence to treatment and its dimensions after the intervention compared to before the intervention (p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of treatment adherence in participants before and after the intervention

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of tele-nursing care on treatment adherence and quality of life among children aged 12 to 18 who underwent heart transplant surgery at Shahid Rajaei Hospital in Tehran. An eight-week tele-supportive educational and nursing program improved participants' quality of life across all dimensions and increased adherence to their treatment regimen. This research is significant due to its innovative approach and the accessibility it provides to caregiving information for children and their families. Furthermore, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which presented challenging conditions and the risk of disease spread. The intervention was delivered continuously throughout this period.

Although there have been limited studies on the impact of tele-nursing on the quality of life and treatment adherence of pediatric heart transplant recipients, this care program has been shown to improve patients' quality of life and enhance their cardiac health [20]. Compared to other surgical procedures, heart transplant surgery patients experience higher levels of stress and are required to adhere to more complex treatment regimens. This significantly affects their quality of life and treatment adherence, which may decrease as a result.

Scientific evidence indicates that promptly educating patients through tablets or smartphones can improve their knowledge levels, treatment adherence, satisfaction, and, most importantly, clinical outcomes. This, in turn, can positively impact the economy of the healthcare system. This effect has been observed in interventions lasting less than one month [21]. Seraj et al. investigated the impact of tele-nursing on treatment adherence in adolescents undergoing heart surgery. The experimental group received tele-nursing services via the WhatsApp messaging platform for one month. The results showed an improvement in treatment adherence across all dimensions following tele-nursing [20], which is consistent with the findings of the present study. Therefore, it is recommended to create a conducive environment to increase the utilization of this approach through public awareness campaigns and the empowerment of nursing staff. However, there are differences between this study and the present research. Seraj et al.'s study included all types of heart surgeries, whereas the present study focused solely on heart transplant surgery. Although the ages of the participants in both studies were similar, the type of surgery and its associated care can significantly impact the quality of life. Therefore, the results of both studies emphasize that tele-nursing care can be effective in improving treatment adherence in children and adolescents undergoing heart surgery.

A study conducted by Kelly et al. aimed to improve access to care and medication adherence among adolescent transplant recipients. This study is similar to the present study in terms of the research community and intervention. The study employed a virtual tele-intervention via video conferencing, which the participants found both acceptable and engaging. As a result, medication adherence increased [22]. Meyer et al. implemented a 24-week web-based physical activity intervention for children with congenital heart disease. The study found that children respond well to virtual instructions and tele-treatment [23]. Tele-nursing and the use of electronic devices and virtual spaces are particularly appealing to children and adolescents, leading to improved satisfaction with such interventions and, consequently, enhanced treatment adherence. Therefore, leveraging this excellent opportunity, tele-education and care, tailored to disease and surgical care, can be implemented effectively.

Moreover, the efficacy of tele-nursing in enhancing treatment adherence has been demonstrated in other chronic conditions, including epilepsy [24]. It is recommended to conduct additional studies to compare the effectiveness of various tele-nursing care methods, such as virtual education, web-based interventions, and telephone follow-ups, given their diversity and differences.

Limited research has been conducted on the effects of tele-nursing interventions on quality of life indicators in pediatric and adolescent heart transplant recipients. A pilot study recently implemented a virtual cardiac readiness program for patients undergoing heart transplant surgery to determine its impact on physical readiness and quality of life. In this study, adolescents aged 10 to 20 participated in a 16-week intervention with biweekly exercise sessions lasting 30 minutes each, led by a trained physiologist on a virtual platform. The successful implementation of virtual cardiac readiness was associated with excellent adherence and improvements in physical readiness and quality of life indicators. Specifically, improvements were observed in fatigue levels and sleep quality [25]. This study demonstrated that physical exercises can be conducted virtually, making them practical during critical times such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Although overall quality of life scores improved in these patients, a more detailed analysis revealed an increase in the anxiety component, which is a crucial dimension of quality of life. This finding contradicts the results of the present study. Cardiac patients often experience increased anxiety as their first psychological response, which can significantly impact their quality of life. This finding may be attributed to the stressful period of COVID-19, which has exacerbated the situation. It is undeniable that COVID-19 has had adverse effects on the mental health and well-being of chronic and cardiac patients [26].

Another study demonstrated that participation in a physical activity program can enhance the quality of life of children with heart disease and heart surgery, particularly those with low baseline quality of life [27]. Nurses can integrate physical activities and exercise programs into tele-education and care programs to improve patients' health outcomes.

However, it is important not to overlook the significance of following up on treatment progress and identifying patients' needs after discharge [28], particularly for children undergoing heart surgery, where care is often family-centered. In these cases, the importance of tele-nursing is evident. A study was conducted to evaluate the impact of a discharge and follow-up program, based on a nursing process model in five sessions, on the quality of life of children undergoing heart surgery. The program was designed to assess educational needs, provide emotional support, and follow up on care. The results showed that following the program, which was based on the needs of parents and children, along with tele-follow-up, significantly enhanced the quality of life of these patients [29]. These results are consistent with the findings of the current study. However, there are differences between the two studies. In the present study, the target population consisted of pre-transplant children, whereas in the mentioned study, school-aged children with congenital heart disease undergoing surgery were included. Nevertheless, both studies demonstrated that educational and counseling interventions post-discharge could improve children's quality of life. Furthermore, the study was conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a significant impact on the quality of life of children under these circumstances.

In contrast to the findings of the present study and other studies, Weigmann-Faßbender et al.'s study, which aimed to investigate the effect of a video game program on the quality of life and fitness of children receiving kidney transplants, showed no impact on the quality of life [30]. Merely focusing on children's interests without increasing their awareness and knowledge about the disease cannot generally improve their quality of life. Quality of life is a multidimensional concept, and improving one aspect of it with entertainment alone may not be sufficient. Therefore, it is necessary to increase children's awareness and knowledge about the disease and its surrounding conditions. One difference between the present study and the referenced study is the type of intervention and the research population. It is important to note that kidney transplant recipients have different conditions compared to heart transplant recipients, and their quality of life may be influenced by different factors.

Our study demonstrated that tele-nursing significantly improved treatment adherence and quality of life among pediatric heart transplant recipients. These findings align with previous research indicating that telehealth interventions can enhance patient outcomes [17, 21]. The improvement in treatment adherence suggests that remote support may mitigate the barriers to compliance often faced by pediatric patients.

Despite these positive outcomes, several limitations must be acknowledged. The study's quasi-experimental design limits causal inferences due to potential confounding parameters that were not controlled for in the analysis. Additionally, while our sample size was adequate for preliminary findings, larger studies are needed to generalize these results across diverse pediatric populations. Future research should explore the long-term impacts of tele-nursing interventions on both adherence and quality of life, as well as investigate potential barriers to implementation in various healthcare settings. This study provides compelling evidence that tele-nursing can positively impact treatment adherence and quality of life for pediatric heart transplant patients. These findings support the integration of telehealth solutions into routine care practices for this vulnerable population. Further studies are warranted to explore long-term outcomes and optimize tele-nursing strategies tailored to the individual needs of patients.

Conclusion

Tele-nursing interventions offer an effective and accessible approach to enhancing treatment adherence and improving the quality of life for pediatric heart transplant recipients.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their appreciation to the hospital authorities and the research participants.

Ethical Permissions: This article is part of the master's thesis in nursing, approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, under the ethics code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1399.178. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After explaining the research objectives, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were also informed about the confidentiality of their data. For participants under the age of 16, consent was obtained from their parent or legal guardian. Informed consent was obtained from the next of kin or legally authorized representative for illiterate participants.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Hosseini Moghadam SM (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (25%); Babaie M (Second Author), Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%); Nourian M (Third Author), Methodologist (14%); Mahdavi M (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (11%); Nasiri M (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Varzeshnejad M (Sixth Author), Main Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Heart transplantation is a critical surgical intervention for patients with medically refractory heart failure and life-threatening cardiac conditions, with approximately 3,500 procedures performed annually worldwide [1, 2]. Post-transplant survival rates have improved significantly, with pediatric patients accounting for approximately 14% of these surgeries [3, 4]. This procedure is particularly essential for children suffering from congenital diseases, valvular heart disorders, and cardiomyopathies that are unresponsive to conventional treatments [5]. However, heart transplantation profoundly impacts the lives of these children and their families, making it crucial to prioritize both survival and quality of life [6].

Post-transplant, patients are prescribed immunosuppressive regimens, including calcineurin inhibitors, azathioprine, everolimus, and corticosteroids, to reduce the risk of rejection [7]. Research highlights various cognitive and developmental challenges experienced by children and adolescents following transplantation, often associated with factors such as reduced cerebral perfusion [8]. A study conducted in Iran reported a 50% five-year survival rate among heart transplant recipients, with some patients surviving up to 25 years post-surgery [9]. Evidence suggests a direct relationship between treatment adherence and survival rates, indicating that compliance significantly enhances outcomes [1, 3, 4].

To improve survival rates, healthcare teams focus on enhancing quality of life and preventing adverse physical, psychological, and social effects. Treatment adherence is crucial for both quality of life and survival among pediatric heart transplant recipients [3, 4]. The quality of life in patients with heart transplants is affected by their adherence to the treatment regimen. Chronic illnesses, including heart transplantation in children, have consequences across physical, psychological, social, educational, and occupational dimensions. Despite increased survival rates, these children may not have a satisfactory quality of life [4]. Non-adherence can lead to severe consequences, including increased healthcare costs, frequent hospitalizations, transplant rejection, and even mortality [10].

Research indicates that treatment adherence significantly influences the survival rates of pediatric heart transplant recipients, highlighting an area that requires further exploration. Treatment adherence also has a reciprocal relationship with the quality of life in these children, emphasizing the need for effective follow-up strategies [4, 11]. Key strategies include regular follow-up visits, capacity-building initiatives, social support, and continuous education by the childcare team [12]. Innovative approaches, such as communication technologies, are increasingly empowering individuals with chronic health conditions. The rise of tele-nursing, particularly in Iran, holds great promise, with studies showing improved self-care through mobile communication platforms and social media [13-15].

However, limited studies have examined the use of tele-nursing among pediatric and adolescent populations. Most existing research has primarily focused on a narrow range of conditions, such as common acute illnesses (e.g., respiratory infections, minor injuries) or chronic conditions like asthma. These studies often rely on cross-sectional data and focus on immediate outcomes rather than long-term efficacy and impact. Populations, such as children with severe chronic illnesses may require tailored tele-nursing approaches [16, 17]. Current research does not sufficiently address how tele-nursing services can be adapted to meet the specific needs of such vulnerable populations. Understanding how tele-nursing can cater to these unique requirements is essential to promote health equity and ensure that all children receive appropriate healthcare services.

Enhancing quality of life and improving treatment adherence among pediatric heart transplant recipients are fundamental nursing responsibilities. Despite the growing body of knowledge, researchers have identified a gap in studies conducted in Iran regarding the impact of tele-nursing on pediatric heart transplant recipients. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of a supportive tele-educational program on treatment adherence and quality of life in children aged 12-18 years.

Materials and Methods

Design

This quasi-experimental single-group study was conducted on children undergoing heart transplantation surgery from October 1 to December 1, 2022, in Tehran, Iran.

Setting

The study was conducted at Shahid Rajaei Heart Hospital, the largest specialized and subspecialized center for heart surgeries in Tehran, where patients requiring heart transplantation surgery are referred. A total of 41 children aged 12 to 18 years, who had undergone heart transplantation surgery at Shahid Rajaei Heart Hospital, were selected through a convenient and comprehensive sampling method.

Participants

The inclusion criteria encompassed children aged 12-18 years who had undergone heart transplantation surgery within the past five years and whose health status was actively monitored at Shahid Rajaei Hospital during the study period. Additional criteria included the willingness of both parents and children to participate, the ability to speak Persian, the absence of mental disorders and sensory impairments, and access to a mobile phone capable of supporting communication programs. Eligible participants had undergone heart transplantation surgery between 6 months and five years prior to the study. Exclusion criteria applied to participants who were re-hospitalized for any reason during the intervention period or who experienced a stressful event, such as the death of a parent.

First, a list of patients was compiled. Of the 50 patients on the list, 41 met the inclusion criteria. Since the sampling for this research was conducted in an educational and treatment hospital in Tehran, Iran, and considering the possibility of sample dropouts, participants were selected using census sampling.

Procedures and interventions

The researcher, in coordination with the hospital’s archive department, prepared a list of eligible children for participation in the study, including their names and contact information. The parents of the children were contacted by phone to explain the purpose, objectives, and implementation of the study. After obtaining consent from both the parents and the children, they were invited to attend an introductory session, sign a written consent form, and receive general guidance on accessing tele-education and nursing care at the hospital. During the face-to-face session, the objectives and implementation methods of the plan were reviewed, and written consent was obtained from both the legal guardian and the child. It was also made clear that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they wished.

The educational and supportive content was divided into two parts. The content was balanced and free from bias, and causal connections between statements were clearly established.

Part one: This section included a general overview where participants received an audiovisual file and text-based instructional material. The language used was clear, concise, and objective, with a formal tone and precise word choice. The text adhered to conventional structure and formatting guidelines, with consistent citation and footnote styles. It was grammatically correct and free from spelling and punctuation errors. No changes were made to the content, except for improvements to meet the desired characteristics. This program covered the medication regimen, dietary regimen, physical activity, social participation and interaction, mental health, and motivation. The educational content was developed, validated, and confirmed through a review of relevant texts and feedback from professors at the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the Educational Research and Treatment Center for Cardiovascular Diseases at Shahid Rajaei Heart Hospital, and the research team.

Part two: Since the children had undergone transplantation surgeries at different times, ranging from six months to five years ago, they had varying informational and psychological needs. Therefore, the researcher prepared a checklist to identify the unique needs of each child and their family. The checklist was developed by reviewing relevant texts, using questionnaires, obtaining feedback from professors, and surveying and conducting brief interviews with several families whose children had undergone heart transplantation surgery.

The parents chose communication software, including WhatsApp, Skype, and Telegram, to interact with families and provide educational content. Telephone calls were made every other day for eight weeks to follow up and answer questions from both parents and children. All children actively participated in the program throughout the intervention. Information was provided in various formats, including audio files, visual materials, and videos, as well as through telephone communication. The study involved a WhatsApp group consisting of all participating children. A daily topic for discussion was raised, allowing the children to interact and discuss self-care management. The participants completed the study questionnaires online twice; once before the start of the intervention and again at the end of the eight-week intervention period.

Outcome measure

The study aimed to evaluate the level of adherence to the treatment regimen and the quality of life in adolescents who underwent heart transplantation.

Data collection tools

1- Demographic Questionnaire for Children and Parents: This questionnaire covered gender, age, number of siblings, birth order, presence of other chronic diseases, frequency of hospitalizations, time of transplantation, parents' age and education, place of residence, and socioeconomic status.

2- The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ 3.0 Cardiac Module 16 (PedsQL™ 3.0 Cardiac Module): This scale is a specific tool used to measure health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with heart disease. The language used is clear, concise, and objective, with technical terms explained when first introduced. No changes in content have been made. The tool consists of 27 items across six dimensions, including heart problems (seven items), treatment (five items), perceived physical appearance (three items), treatment anxiety (four items), cognitive problems (five items), and communication (three items). The scoring system for quality of life is based on a five-point Likert scale (zero=never, one=rarely, two=sometimes, three=often, four=almost always). The items are reverse-scored and linearly transformed to a scale of 0 to 100 (zero=100, one=75, two=50, three=25, and four=0), with higher scores indicating worse quality of life. The total score is calculated as the sum of all items. This tool was translated and validated in Persian by Noori et al. The internal consistency was confirmed using Cronbach's alpha, which was reported as 0.87 [18]. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha was recalculated using all the samples and found to be 0.89.

3- Modanloo Medication Adherence Questionnaire for Chronic Patients: Modanloo [19] designed and validated the medication adherence questionnaire for chronic patients. The questionnaire was created to assess medication adherence. The language used is clear, concise, and objective, with technical terms applied consistently throughout. The text is free from grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. The questionnaire consists of 40 items and subscales, including compliance with treatment (nine items), willingness to participate in treatment (seven items), ability to adapt (seven items), integration of treatment into life (five items), adherence to treatment (four items), commitment to treatment (five items), and management in treatment execution (three items). The text follows a conventional academic structure and formatting, with clear section headings and citations. The tool measures compliance with treatment, willingness to participate in treatment, ability to adapt, integration of treatment into life, adherence to treatment, commitment to treatment, and management in treatment execution. Scores range from 0 to 45 for compliance, 0 to 35 for willingness, 0 to 35 for adaptability, 0 to 25 for integration, 0 to 20 for adherence, 0 to 25 for commitment, and 0 to 15 for management. Higher scores indicate better adherence to treatment. The developers confirmed the content validity of this tool. The tool's reliability was reported as 0.875 using the test-retest method [19]. In this study, we re-evaluated the tool's reliability using the test-retest method on 10 adolescents who were not part of the sample (r=0.88).

Data analysis

SPSS version 16 software was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were employed to present the demographic characteristics and mean scores of quality of life and treatment adherence. The normal distribution of parameters was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The mean scores for quality of life and treatment adherence were compared at two time points (before and after the intervention) using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A paired t-test was used to compare the mean scores of quality of life and treatment adherence before and after the intervention. Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between demographic parameters and treatment adherence or quality of life.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Findings

The study participants had a mean age of 12.66±2.29 years, with 51.2% being girls. The majority of participants (26.80%) were in the sixth grade, and 26.80% did not have any other chronic diseases. Three fathers had previously passed away. The majority of fathers (75.60%) had less than a diploma, while the majority of mothers (80.50%) had a diploma. The age range of mothers was between 31 and 54 years, while for fathers, it was between 36 and 64 years. In 73.2% of cases, mothers were the primary caregivers (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n=41)

The lowest mean was observed post-treatment, with a mean of 44.3±78.3, while the highest mean was related to cognitive problems post-treatment, with a mean of 21.4±90.7. The mean quality of life before the intervention was 58.31±15.63. After the intervention, the mean quality of life was 10.65±21.4. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory results showed that the lowest mean score was associated with cognitive problems post-treatment, with a mean of 34.1±91.0, while the highest mean score was related to communication problems post-treatment, with a mean of 31.2±31.2. A lower score on the questionnaire indicated a higher quality of life. Furthermore, the paired t-test results indicated a significant difference in quality of life and its dimensions after the intervention compared to before the intervention (p<0.001; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the average score of quality of life in participants before and after the intervention

Before the intervention, treatment adherence had a mean of 21.17±13.68. The lowest mean was related to treatment implementation post-treatment, with a mean of 29.5±65.2, and the highest mean was related to adherence to treatment post-treatment, with a mean of 40.56±16.40. After the intervention, treatment adherence had a mean of 82.18±81.60. The study found that the lowest mean score was associated with treatment implementation post-treatment (90.7±10.4), while the highest mean score was associated with adherence to treatment post-treatment (47.56±67.60). The results of the paired t-test indicated a significant difference in adherence to treatment and its dimensions after the intervention compared to before the intervention (p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of treatment adherence in participants before and after the intervention

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of tele-nursing care on treatment adherence and quality of life among children aged 12 to 18 who underwent heart transplant surgery at Shahid Rajaei Hospital in Tehran. An eight-week tele-supportive educational and nursing program improved participants' quality of life across all dimensions and increased adherence to their treatment regimen. This research is significant due to its innovative approach and the accessibility it provides to caregiving information for children and their families. Furthermore, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which presented challenging conditions and the risk of disease spread. The intervention was delivered continuously throughout this period.

Although there have been limited studies on the impact of tele-nursing on the quality of life and treatment adherence of pediatric heart transplant recipients, this care program has been shown to improve patients' quality of life and enhance their cardiac health [20]. Compared to other surgical procedures, heart transplant surgery patients experience higher levels of stress and are required to adhere to more complex treatment regimens. This significantly affects their quality of life and treatment adherence, which may decrease as a result.

Scientific evidence indicates that promptly educating patients through tablets or smartphones can improve their knowledge levels, treatment adherence, satisfaction, and, most importantly, clinical outcomes. This, in turn, can positively impact the economy of the healthcare system. This effect has been observed in interventions lasting less than one month [21]. Seraj et al. investigated the impact of tele-nursing on treatment adherence in adolescents undergoing heart surgery. The experimental group received tele-nursing services via the WhatsApp messaging platform for one month. The results showed an improvement in treatment adherence across all dimensions following tele-nursing [20], which is consistent with the findings of the present study. Therefore, it is recommended to create a conducive environment to increase the utilization of this approach through public awareness campaigns and the empowerment of nursing staff. However, there are differences between this study and the present research. Seraj et al.'s study included all types of heart surgeries, whereas the present study focused solely on heart transplant surgery. Although the ages of the participants in both studies were similar, the type of surgery and its associated care can significantly impact the quality of life. Therefore, the results of both studies emphasize that tele-nursing care can be effective in improving treatment adherence in children and adolescents undergoing heart surgery.

A study conducted by Kelly et al. aimed to improve access to care and medication adherence among adolescent transplant recipients. This study is similar to the present study in terms of the research community and intervention. The study employed a virtual tele-intervention via video conferencing, which the participants found both acceptable and engaging. As a result, medication adherence increased [22]. Meyer et al. implemented a 24-week web-based physical activity intervention for children with congenital heart disease. The study found that children respond well to virtual instructions and tele-treatment [23]. Tele-nursing and the use of electronic devices and virtual spaces are particularly appealing to children and adolescents, leading to improved satisfaction with such interventions and, consequently, enhanced treatment adherence. Therefore, leveraging this excellent opportunity, tele-education and care, tailored to disease and surgical care, can be implemented effectively.

Moreover, the efficacy of tele-nursing in enhancing treatment adherence has been demonstrated in other chronic conditions, including epilepsy [24]. It is recommended to conduct additional studies to compare the effectiveness of various tele-nursing care methods, such as virtual education, web-based interventions, and telephone follow-ups, given their diversity and differences.

Limited research has been conducted on the effects of tele-nursing interventions on quality of life indicators in pediatric and adolescent heart transplant recipients. A pilot study recently implemented a virtual cardiac readiness program for patients undergoing heart transplant surgery to determine its impact on physical readiness and quality of life. In this study, adolescents aged 10 to 20 participated in a 16-week intervention with biweekly exercise sessions lasting 30 minutes each, led by a trained physiologist on a virtual platform. The successful implementation of virtual cardiac readiness was associated with excellent adherence and improvements in physical readiness and quality of life indicators. Specifically, improvements were observed in fatigue levels and sleep quality [25]. This study demonstrated that physical exercises can be conducted virtually, making them practical during critical times such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Although overall quality of life scores improved in these patients, a more detailed analysis revealed an increase in the anxiety component, which is a crucial dimension of quality of life. This finding contradicts the results of the present study. Cardiac patients often experience increased anxiety as their first psychological response, which can significantly impact their quality of life. This finding may be attributed to the stressful period of COVID-19, which has exacerbated the situation. It is undeniable that COVID-19 has had adverse effects on the mental health and well-being of chronic and cardiac patients [26].

Another study demonstrated that participation in a physical activity program can enhance the quality of life of children with heart disease and heart surgery, particularly those with low baseline quality of life [27]. Nurses can integrate physical activities and exercise programs into tele-education and care programs to improve patients' health outcomes.

However, it is important not to overlook the significance of following up on treatment progress and identifying patients' needs after discharge [28], particularly for children undergoing heart surgery, where care is often family-centered. In these cases, the importance of tele-nursing is evident. A study was conducted to evaluate the impact of a discharge and follow-up program, based on a nursing process model in five sessions, on the quality of life of children undergoing heart surgery. The program was designed to assess educational needs, provide emotional support, and follow up on care. The results showed that following the program, which was based on the needs of parents and children, along with tele-follow-up, significantly enhanced the quality of life of these patients [29]. These results are consistent with the findings of the current study. However, there are differences between the two studies. In the present study, the target population consisted of pre-transplant children, whereas in the mentioned study, school-aged children with congenital heart disease undergoing surgery were included. Nevertheless, both studies demonstrated that educational and counseling interventions post-discharge could improve children's quality of life. Furthermore, the study was conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a significant impact on the quality of life of children under these circumstances.

In contrast to the findings of the present study and other studies, Weigmann-Faßbender et al.'s study, which aimed to investigate the effect of a video game program on the quality of life and fitness of children receiving kidney transplants, showed no impact on the quality of life [30]. Merely focusing on children's interests without increasing their awareness and knowledge about the disease cannot generally improve their quality of life. Quality of life is a multidimensional concept, and improving one aspect of it with entertainment alone may not be sufficient. Therefore, it is necessary to increase children's awareness and knowledge about the disease and its surrounding conditions. One difference between the present study and the referenced study is the type of intervention and the research population. It is important to note that kidney transplant recipients have different conditions compared to heart transplant recipients, and their quality of life may be influenced by different factors.

Our study demonstrated that tele-nursing significantly improved treatment adherence and quality of life among pediatric heart transplant recipients. These findings align with previous research indicating that telehealth interventions can enhance patient outcomes [17, 21]. The improvement in treatment adherence suggests that remote support may mitigate the barriers to compliance often faced by pediatric patients.

Despite these positive outcomes, several limitations must be acknowledged. The study's quasi-experimental design limits causal inferences due to potential confounding parameters that were not controlled for in the analysis. Additionally, while our sample size was adequate for preliminary findings, larger studies are needed to generalize these results across diverse pediatric populations. Future research should explore the long-term impacts of tele-nursing interventions on both adherence and quality of life, as well as investigate potential barriers to implementation in various healthcare settings. This study provides compelling evidence that tele-nursing can positively impact treatment adherence and quality of life for pediatric heart transplant patients. These findings support the integration of telehealth solutions into routine care practices for this vulnerable population. Further studies are warranted to explore long-term outcomes and optimize tele-nursing strategies tailored to the individual needs of patients.

Conclusion

Tele-nursing interventions offer an effective and accessible approach to enhancing treatment adherence and improving the quality of life for pediatric heart transplant recipients.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their appreciation to the hospital authorities and the research participants.

Ethical Permissions: This article is part of the master's thesis in nursing, approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, under the ethics code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1399.178. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After explaining the research objectives, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were also informed about the confidentiality of their data. For participants under the age of 16, consent was obtained from their parent or legal guardian. Informed consent was obtained from the next of kin or legally authorized representative for illiterate participants.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Hosseini Moghadam SM (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (25%); Babaie M (Second Author), Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%); Nourian M (Third Author), Methodologist (14%); Mahdavi M (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (11%); Nasiri M (Fifth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Varzeshnejad M (Sixth Author), Main Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2024/10/26 | Accepted: 2024/12/19 | Published: 2024/12/25

Received: 2024/10/26 | Accepted: 2024/12/19 | Published: 2024/12/25

References

1. Kraus MJ, Smits JM, Meyer AL, Strelniece A, Van Kins A, Boeken U, et al. Outcomes in patients with cardiac amyloidosis undergoing heart transplantation: The eurotransplant experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023;42(6):778-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.healun.2023.01.001]

2. Page A, Messer S, Large SR. Heart transplantation from donation after circulatory determined death. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(1):75-81. [Link] [DOI:10.21037/acs.2018.01.08]

3. Godown J, Thurm C, Hall M, Soslow JH, Feingold B, Mettler BA, et al. Changes in pediatric heart transplant hospitalization costs over time. Transplantation. 2018;102(10):1762-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/TP.0000000000002202]

4. Sehgal S, Shea E, Kelm L, Kamat D. Heart transplant in children: What a primary care provider needs to know. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47(4):e172-8. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/19382359-20180319-01]

5. Voeller RK, Epstein DJ, Guthrie TJ, Gandhi SK, Canter CE, Huddleston CB. Trends in the indications and survival in pediatric heart transplants: A 24-year single-center experience in 307 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):807-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.052]

6. Dipchand AI, Laks JA. Pediatric heart transplantation: Long-term outcomes. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;36(Suppl 2):175-89. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12055-019-00820-3]

7. Eisen H, Ross H. Optimizing the immunosuppressive regimen in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(Suppl 5):S207-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.healun.2004.03.010]

8. Barron LC, Haas N, Hagl C, Schulze‐Neick I, Ulrich S, Lehner A, et al. Motor outcome, executive functioning, and health‐related quality of life of children, adolescents, and young adults after ventricular assist device and heart transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24(1):e13631. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/petr.13631]

9. Raiesdana N, Peyrovi H, Mehrdad N. Exploring challenges of living after heart transplantation in heart recipients in Iran. Koomesh. 2017;19(2):492-504. [Persian] [Link]

10. McCormick King ML, Mee LL, Gutiérrez-Colina AM, Eaton CK, Lee JL, Blount RL. Emotional functioning, barriers, and medication adherence in pediatric transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(3):283-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jst074]

11. Amodeo G, Ragni B, Calcagni G, Piga S, Giannico S, Yammine ML, et al. Health-related quality of life in Italian children and adolescents with congenital heart diseases. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):173. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12872-022-02611-y]

12. Kamrani F, Nikkhah S, Borhani F, Jalali M, Shahsavari S, Nirumand-Zandi K. The effect of patient education and nurse-led telephone follow-up (telenursing) on adherence to treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;4(3):16-24. [Persian] [Link]

13. Fathizadeh P, Heidari H, Masoudi R, Sedehi M, Khajeali F. Telenursing strategies in Iran: A narrative literature review. Int J Epidemiol Health Sci. 2020;1:e3. [Link] [DOI:10.51757/IJEHS.1.3.2020.46189]

14. Sadeghmoghadam L, Ahmadi Babadi S, Delshad Noghabi A, Nazari S, Farhadi A. Effect of telenursing on aging perception of Iranian older adults. Educ Gerontol. 2019;45(7):476-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03601277.2019.1657263]

15. Shahsavari A, Bavarsad MB. Is telenursing an effective method to control BMI and HbA1c in illiterate patients aged 50 years and older with type 2 diabetes? A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Caring Sci. 2020;9(2):73-9. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/JCS.2020.011]

16. Nishigaki K, Yamaji N, Adachi N, Kamei T, Kobayashi K, Kakazu S, et al. Telenursing on primary family caregivers and children with disabilities: A scoping review. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1374442. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fped.2024.1374442]

17. Shah AC, Badawy SM. Telemedicine in pediatrics: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2021;4(1):e22696. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/22696]

18. Noori N, Teimouri A, Boryri T, Shafiee SS. Quality of life in children and adolescents with congenital heart diseases in Zahedan, Iran. J Pediatr Perspect. 2017;5(1):4193-208. [Link]

19. Modanloo M. Development and psychometric tools adherence of treatment in patients with chronic [dissertation]. Tehran: Iran University; 2013. [Link]

20. Seraj B, Alaee Alaee-Karahroudi F, Ashktorab T, Moradian M. The effect of telenursing on adherence to treatment in adolescents undergoing cardiac surgery. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;9(1):100-10. [Persian] [Link]

21. Timmers T, Janssen L, Kool RB, Kremer JA. Educating patients by providing timely information using smartphone and tablet apps: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e17342. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/17342]

22. Kelly SL, Steinberg EA, Suplee A, Upshaw NC, Campbell KR, Thomas JF, et al. Implementing a home-based telehealth group adherence intervention with adolescent transplant recipients. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(11):1040-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/tmj.2018.0164]

23. Meyer M, Brudy L, Fuertes-Moure A, Hager A, Oberhoffer-Fritz R, Ewert P, et al. E-health exercise intervention for pediatric patients with congenital heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2021;233:163-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.058]

24. Mousavi SK, Kamali M, Azizkhani H. Effect of telephone education on medication adherence in patients with epilepsy. HAYAT. 2021;27(2):117-29. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_213_20]

25. Ziebell D, Stark M, Xiang Y, Mckane M, Mao C. Virtual cardiac fitness training in pediatric heart transplant patients: A pilot study. Pediatr Transplant. 2023;27(1):e14419. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/petr.14419]

26. Cousino MK, Pasquali SK, Romano JC, Norris MD, Yu S, Reichle G, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on CHD care and emotional wellbeing. Cardiol Young. 2021;31(5):822-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1047951120004758]

27. Dulfer K, Duppen N, Kuipers IM, Schokking M, Van Domburg RT, Verhulst FC, et al. Aerobic exercise influences quality of life of children and youngsters with congenital heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):65-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.010]

28. McGillion MH, Parlow J, Borges FK, Marcucci M, Jacka M, Adili A, et al. Post-discharge after surgery virtual care with remote automated monitoring-1 (PVC-RAM-1) technology versus standard care: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;374:n2209. [Link]

29. Sadeghi F, Kermanshahi S, Memariyan R. The effect of discharge planning on the quality of life of school-age children with congenital heart disease undergoing heart surgery. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2013;21(1):15-25. [Persian] [Link]

30. Weigmann‐Faßbender S, Pfeil K, Betz T, Sander A, Weiß K, Tönshoff B, et al. Physical fitness and health‐related quality of life in pediatric renal transplant recipients: An interventional trial with active video gaming. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24(1):e13630. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/petr.13630]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |