Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 581-588 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Alwi M, Yusriani Y, Purnawansyah P. Stunting Incidence Based on Socio-Demographic Determinants, Family Food Security, and Maternal Digital Parenting. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :581-588

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-77279-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-77279-en.html

1- Faculty of Public Health, University Muslim Indonesia, Makassar, Indonesia

2- Faculty of Ilmu Komputer, University Muslim Indonesia, Makassar, Indonesia

2- Faculty of Ilmu Komputer, University Muslim Indonesia, Makassar, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 602 kb]

(1982 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1030 Views)

Full-Text: (69 Views)

Introduction

Mothers play a crucial role in their children's development. Although Indonesian society often attributes stunted growth to hereditary factors, stunting is fundamentally a health issue driven by multiple contributing factors. It represents a chronic nutritional deficiency in toddlers, manifesting as a height significantly shorter than expected for their age [1].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 20% of pregnancies experience inadequate nutritional intake, which continues to affect the baby after birth. This deficiency can lead to growth disorders in children, such as stunting. Characterized by a child's height being shorter than the age-appropriate standard, stunting is the result of chronic malnutrition due to prolonged insufficient nutrient intake. The first two years of life, commonly known as the first 1,000 days, mark a pivotal stage for a child's development and growth, highlighting the family as the primary setting for nurturing and caregiving. Recognizing this, the government has prioritized a family-centered approach to stunting prevention. Stunting poses a significant threat to human quality and national competitiveness in the future, as it not only impairs physical growth but also brain development, potentially hindering educational achievements, productivity, and creativity. During this period, babies must receive sufficient and appropriate nutrition to avoid malnutrition, which can lead to stunting [2]. Infants and toddlers face serious short-term consequences from stunting, including increased morbidity and mortality risks. Over time, stunting also affects intellectual and cognitive abilities in the medium term. In the long term, stunting negatively impacts the overall quality of human resources, influencing productivity and national development [4].

In 2018, South Sulawesi had a stunting prevalence of 35.7%, with several districts showing particularly high rates, such as Pangkep (50.5%) and Tana Toraja (47%). The national stunting rate that year was 30.8%, a significant decrease from previous years, as shown by Basic Health Research data, where stunting prevalence in 2007, 2010, and 2013 ranged between 34.6% and 37.2%. To further combat stunting in Indonesia, the government aimed to reduce the rate to 28%, a key objective outlined in the 2019 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) [5].

To address stunting, it is essential to educate the community on the importance of nutrition for pregnant women and toddlers. Research shows that health education interventions, designed with specific methods to prevent health problems, have significantly improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, highlighting the effectiveness of well-structured educational efforts [6]. Despite these educational efforts, changes in behavior and knowledge often prove short-lived, as evidenced by the persistence of issues, like stunting. An integrated strategy is required for effective stunting prevention, which includes improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as strengthening family support, the involvement of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and cultural factors.

The aim of the research was to analyze the connection between knowledge, attitude, actions, family support, the role of cadre-integrated health posts, food resilience, digital parenting, and the culture of mothers of toddlers at Marusu Health Center.

Instrument and Methods

This quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted in the Marusu Health Center area, focusing on regions with high stunting prevalence from August to September 2024. Primary data were collected through questionnaires given to respondents, while secondary data were sourced from the Marusu Health Center's reports. The study population comprised 341 pregnant women in the Marusu Health Center area in 2024, and total sampling was used to determine the sample size.

Data collection involved a combination of interviews, observations, and questionnaires. Interviews were conducted with mothers of toddlers (children under five years old) who experience stunting, to gather information about the data and other relevant details related to the issue being studied, as well as to focus on the research subject. Observations were made to thoroughly study the subjects, specifically stunted children, by directly observing factors related to the research at the study location, such as knowledge, attitudes, actions, family support, the role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and the cultural influences on mothers of toddlers. Additionally, a questionnaire was administered to assess and analyze their knowledge, attitudes, actions, family support, the role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and cultural influences. The questionnaire included pre-formulated questions with multiple-choice answers for the respondents. It consisted of 132 items based on a four-point Likert scale and a two-point Guttman scale. Construct validity was measured using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), with an average validity result of 0.85 and a Cronbach's Alpha reliability of 0.90.

The analysis process involved three techniques, including univariate analysis to describe the characteristics of both independent and dependent parameters, bivariate analysis to determine the relationship between independent and dependent parameters, and multivariate analysis to identify the independent parameters that have the greatest influence on the dependent parameter. A multivariate test was conducted using several logistic regression analyses, as the dependent parameter was categorical. This approach aimed to combine various independent parameters that are considered most effective in predicting the dependent outcomes.

Findings

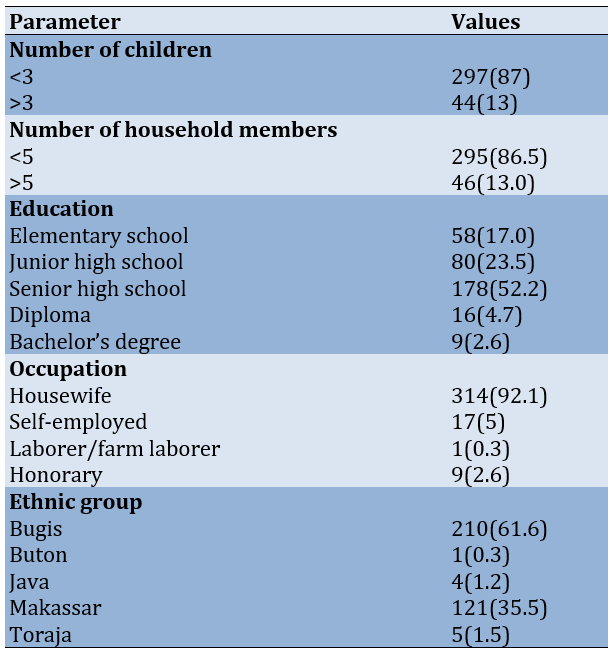

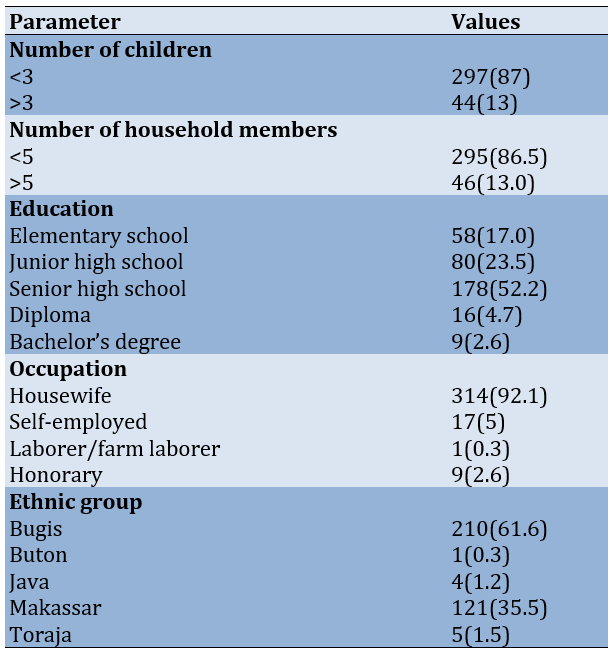

A total of 341 pregnant women participated in the research (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of pregnant women’s demographic characteristics

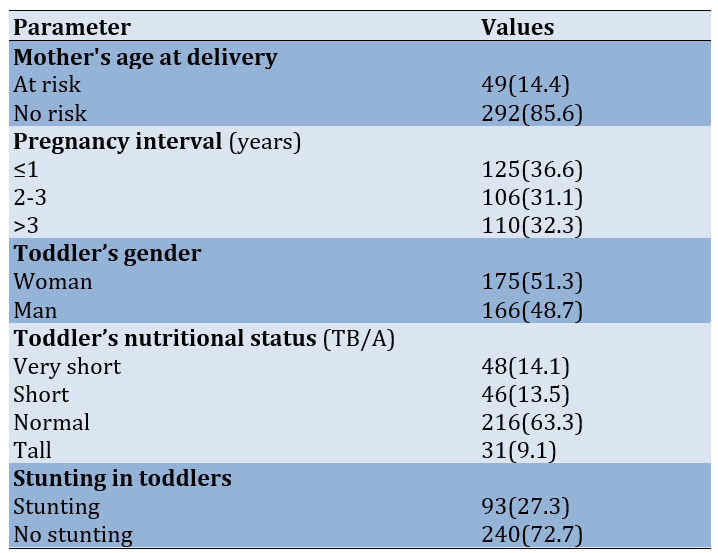

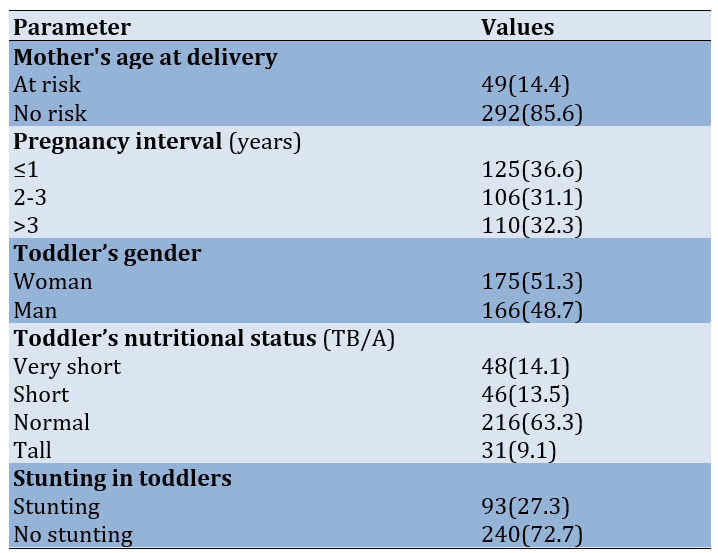

Most mothers reported a pregnancy interval of one year or less. Also, the nutritional status of most toddlers was normal (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of respondents based on maternal and child health in the Marusu Health Center working area, Maros Regency in 2024

Most respondents reported not enough level of knowledge and the lack of factors affecting stunting incidents. Also, family support was reported to be enough by most subjects (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of respondents based on knowledge, affective factors, actions, family support, role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and culture with stunting incidents at Marusu Health Center in 2024

Discussion

The aim of the research was to analyze the connection between knowledge, attitude, actions, family support, the role of cadre-integrated health posts, food resilience, digital parenting, and the culture of mothers of toddlers at Marusu Health Center. The findings indicated that a significant proportion of respondents had three or fewer children (87%) and five or fewer household members (86.5%). This suggests that the families in this study were predominantly small to medium-sized, which may affect their capacity to provide sufficient attention and resources for the health and well-being of each child. Smaller families can often focus more on care and nutrition, which may help control the risk of health problems in children, including stunting. However, the increasing number of family members, if not matched by an increase in income, may result in the uneven distribution of food consumption. The available food for a larger family may only be sufficient for a family half its size, and such conditions may not be enough to prevent nutritional disorders in larger families [7].

A significant majority of respondents possessed a high school education (52.2%), while only a small proportion had a bachelor's degree (2.6%). This indicates that maternal education plays a crucial role in shaping knowledge about nutrition and child health. Mothers with higher educational attainment are likely to have better access to health information and greater awareness of the importance of proper nutrition and effective parenting practices [8]. Given that most respondents have completed high school or less, it is essential to prioritize educational programs focusing on nutrition and child health in the Marusu Health Center service area.

The working mother factor does not play a central role in causing child nutritional problems, but work is mentioned as a factor influencing the provision of food, nutrients, and child care [9]. In terms of employment, 92.1% of respondents were housewives. This suggests that these mothers were more focused on household chores and caring for their children rather than working outside the home. Although the role of a housewife allows more time to care for children, the availability of accurate information and support from maternal and child health programs is crucial in efforts to improve children's nutritional status, particularly in preventing stunting.

Based on maternal health data, the majority of mothers (85.6%) were not classified as high-risk according to their age at delivery. However, 14.4% of mothers fell into the risk category, which requires special attention, as giving birth at too young or too old an age is associated with an increased risk of health complications for both the mother and baby. This can include stunting in children due to psychological influences [10]. Young mothers often lack preparedness for pregnancy and may be unfamiliar with proper prenatal care, while older mothers typically experience reduced stamina and diminished motivation in managing their pregnancies.

Given that pregnancy spacing is a crucial determinant of children's health, it can be concluded that inadequate pregnancy spacing contributes to the occurrence of stunting. Close birth spacing can lead to stunting because it affects parenting patterns, as mothers may not have fully recovered from the previous pregnancy, both physically and nutritionally. In this study, 36.6% of mothers had a pregnancy spacing of equal or less than one year. Pregnancy spacing that is too short is known to increase the risk of stunting in subsequent children. The risk of stunting is significantly higher for children with a birth interval of less than two years, being 11.65 times greater than for children with a birth spacing of two years or longer [11].

The nutritional status of toddlers, as assessed by height-for-age, showed that 14.1% of children fell into the "very short" category, while 13.5% were classified as "short." This indicates that nearly 30% of children experience growth problems that can be categorized as stunting. Socio-demographic factors, such as maternal education, economic conditions, and employment, can influence this nutritional status, particularly in families with limited resources. Intervention efforts targeting high-risk families are essential to improve stunting conditions. The fact that 27.3% of toddlers were experiencing stunting confirms that it remains a significant health issue in the study area. Given that the majority of mothers were housewives with secondary education, intervention programs focusing on nutrition education, increasing access to nutritious food, and regular monitoring of maternal and child health are necessary. Health programs, such as integrated service post and nutrition counseling should be maximized to provide relevant information to these mothers.

The study results highlight the importance of addressing socio-demographic factors and maternal and child health in efforts to prevent stunting. Limited maternal education and work as housewives may restrict access to essential health information, particularly regarding a balanced diet and nutrition for toddlers. Therefore, affordable and easily accessible nutrition and health counseling for the community, especially in rural areas, is needed to reduce stunting rates. Additionally, increasing education about family planning and ideal birth spacing will help reduce health risks for mothers and children, ultimately contributing to a decrease in stunting prevalence in the area.

Theoretically, maternal age at birth is a significant risk factor for stunting. Mothers who give birth at too young an age (<20 years) or too old (>35 years) are at higher risk of experiencing pregnancy and birth complications, which can directly affect the health of the baby [10]. Maternal age significantly influences pregnancy health, as younger mothers may lack the physiological maturity required for a healthy pregnancy, while older mothers are often at heightened risk for chronic health conditions such as hypertension and gestational diabetes, both of which can adversely impact fetal growth. Previous studies have shown that mothers who give birth at a young age often face difficulties in providing proper nutrition to their children, due to both limited knowledge and physical and emotional capacity [8].

This research demonstrated that maternal age during childbirth was not significantly related to the incidence of stunting in children, from a statistical standpoint. One possible explanation is the presence of other, more dominant parameters, such as access to good health care during pregnancy, family support, or socio-economic status. These factors may have a greater impact on preventing or worsening stunting, even though maternal age is theoretically a risk factor. In addition, the development of better health services to support mothers at various ages can reduce the risk of stunting, thereby diminishing the influence of age as a single factor. Further research that considers the interaction between age and socio-economic conditions may be necessary to explain this relationship more comprehensively.

The attitudes of mothers toward their children's health and nutrition reflect their perceptions of the importance of nutrition in fostering children's growth and development. According to cognitive behavioral theory, positive attitudes are typically translated into actions that support children's health, such as choosing nutritious foods and ensuring regular health checks. Research shows that a good attitude toward healthy eating patterns can contribute to stunting prevention.

The results of this study indicated that there was no substantial correlation between maternal attitudes and the occurrence of stunting. One possible explanation is that, although mothers may have positive attitudes, the actual implementation of these attitudes into real actions may be influenced by external constraints such as economic access, lack of social support, or dietary patterns that are already ingrained in family culture [12]. Additionally, positive attitudes also require knowledge and skills to implement appropriate actions, which are not always available in all socio-economic contexts [9]. Therefore, efforts to prevent stunting should include aspects of education and attitude change, along with practical support to help overcome obstacles in implementing actions.

Maternal actions, such as providing nutritious food and proper health care, play a crucial role in preventing stunting. According to health behavior theory, positive actions in child care, including exclusive breastfeeding and the timely introduction of complementary foods, can reduce the risk of malnutrition and stunting [13]. Despite this, the findings of the study showed that maternal actions do not have a statistically significant relationship with the prevalence of stunting. This suggests that, although maternal actions are important, other factors, such as social support, access to health facilities, and adequate knowledge about nutrition, also influence these outcomes [14]. While mothers may perform beneficial actions, success in preventing stunting is also influenced by limited access to resources and a supportive environment. The availability of health services and dietary habits within households may further contribute to the association between maternal actions and the incidence of stunting.

Family support is often considered a crucial factor in ensuring that mothers have a supportive environment to care for their children. Support from other family members, such as partners or grandparents, can assist mothers in caring for their children and providing an environment conducive to their children’s growth and development [15]. Effective support can help mothers overcome the challenges of providing adequate nutrition for their children. However, this study found that family support was not significantly associated with stunting. This may suggest that the type of support mothers receive is not directly related to aspects of children’s nutrition and health. For example, emotional support alone may not be sufficient to prevent stunting if it is not accompanied by practical support, such as help with preparing nutritious food or access to health services. This indicates that intervention programs should focus on improving the quality of family support, particularly in terms of childcare and meeting nutritional needs.

The involvement of integrated service post is crucial in delivering nutrition education and essential health services to mothers and children. Through direct community engagement and consistent monitoring of child development, they effectively disseminate information about optimal nutrition practices, as outlined in the theory of innovation diffusion [16]. The findings of this study showed that there was no significant association between the engagement of integrated service post and the occurrence of stunting, likely due to their limited capacity and resources to effectively implement their duties. Additionally, the infrequency of cadre visits may be insufficient to substantially influence stunting prevention. Therefore, enhancing training and support for integrated service post is essential to empower them to take a more proactive and effective role in stunting prevention within the community [17].

The findings indicated that the correlation between food security and the incidence of stunting was not statistically significant. While mothers experiencing food insecurity had a higher percentage of stunted children (22.3%) compared to those with adequate food security (27.3%), this disparity did not meet the threshold of statistical significance necessary to infer a strong effect. Family food security is closely linked to food availability, which is one of the factors or indirect causes affecting children's nutritional status [18]. Sufficient access to nutritious food is crucial for preventing malnutrition and stunting. Nonetheless, the findings of this study suggest that food security alone is insufficient to guarantee that children receive the necessary nutrition for optimal growth. Other factors, such as daily dietary patterns, food diversity, and healthy eating habits, may have a more significant impact on children's nutritional status. Previous research has demonstrated that even in situations of adequate food security, a lack of variety in food choices can still put children at risk of malnutrition and stunting [19]. Additionally, factors, such as nutrition education, culinary skills, and food expenditures play a significant role in determining the quality of consumed food. Food security that solely assesses physical access to food may not adequately represent effective nutritional intake. Therefore, further research is necessary to investigate the intricate relationships between food security, dietary practices, and children's nutritional status, as well as to understand how daily eating habits and food selections may more directly influence the risk of stunting.

The study results showed that there was no significant association between digital parenting and the prevalence of stunting. Although mothers who did not practice digital parenting had a lower proportion of stunted children (7%) compared to those who did (20.2%), this difference was not strong enough to be considered statistically significant.

The theory of media use states that digital technology can provide parents with quick and easy access to health and nutrition information [20]. In the context of parenting, technology can be a useful tool for obtaining accurate information on how to care for and nourish children. However, these results suggest that digital parenting alone may not be enough to address stunting. It is possible that, although parents receive good information through digital media, the implementation of this information in daily practice may be hindered by other factors, such as limited resources, cultural habits, or inadequate social support.

In addition, although mothers who practiced less digital parenting showed a lower proportion of stunted children, this may indicate that more traditional physical interactions and parenting may have a greater positive impact on child growth. Previous research has shown that direct involvement in parenting, such as feeding, attention to hygiene, and positive social interactions, can be more influential in preventing stunting than simply receiving information through technology.

Therefore, further research is needed to explore more deeply how digital parenting and traditional parenting patterns interact and how both can be optimized to support healthy child development. This involves assessing the impacts, both positive and negative, of technology in parenting and how it can be seamlessly integrated with established parenting practices to effectively reduce the risk of stunting.

In the context of stunting, cultural influences are often related to dietary practices, childcare methods, and health behaviors that are passed down from one generation to the next. Grounded in sociocultural theory, the customs and values characteristic of a culture can shape maternal and child health practices, especially regarding nutrition and care. A positive or beneficial culture is typically associated with practices that support optimal child growth, such as ensuring balanced nutrition, cleanliness, and access to health services [21].

However, the results of this study indicated that the correlation between cultural factors and the occurrence of stunting was not statistically significant. Despite this, mothers with less favorable cultural practices had a higher proportion of stunted children (16.1%) compared to those with more favorable cultural practices (11.1%). Each community has different cultural norms, which affect children's health both directly and indirectly [22]. Simple measurements may not be sufficient to capture the complexity of culture, which can lead to statistically insignificant results. Culture does not stand alone but often interacts with socioeconomic factors, such as income, education, and access to health services. For example, mothers with favorable cultural practices may be more exposed to health information and have better access to resources. Conversely, mothers with less favorable cultural practices may face greater economic or social challenges. The interaction of these factors can obscure the direct influence of culture, making it harder to observe a significant relationship. Although culture can influence family diets, many other parameters also determine a child's nutritional status. For example, even though a culture may encourage the consumption of certain foods, the nutritional quality of those foods is also important. In some cases, cultures may emphasize foods rich in carbohydrates but low in protein or micronutrients, which may increase the risk of stunting, even though the diet is considered "good" from a cultural perspective [22-30].

These non-significant results may also suggest the need for more culturally specific interventions. Interventions based solely on culture may not be effective without addressing more specific local needs, such as adapting to modern nutritional practices or modifying parenting behaviors. In some communities, cultural factors may play a significant role in parenting practices, but culturally based interventions must be tailored to the local context to be effective.

Conclusion

There is no statistically significant relationship between knowledge, attitudes, actions, family support, the role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and cultural influences and the incidence of stunting in the Marusu Health Center region.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all contributors, especially the staff of the Marusu Health Center, for their invaluable support throughout the research process. They also acknowledge the financial assistance from the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service, Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, which significantly contributed to the research, writing, and publication of this article as part of the fundamental regular research program.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Committee for Health Research at the Faculty of Health Sciences "Maluku Husada" issued an ethics permit to protect the human rights of individuals participating in health research after reviewing the relevant research protocols. This approval can be identified by the registration number RK. 177/KEPK/STIK/VIII/2024.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Alwi MK (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Yusriani Y (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Purnawansyah P (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: Financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article was provided by the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Services under the Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology at the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, as part of the Master Thesis Research Scheme.

Mothers play a crucial role in their children's development. Although Indonesian society often attributes stunted growth to hereditary factors, stunting is fundamentally a health issue driven by multiple contributing factors. It represents a chronic nutritional deficiency in toddlers, manifesting as a height significantly shorter than expected for their age [1].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 20% of pregnancies experience inadequate nutritional intake, which continues to affect the baby after birth. This deficiency can lead to growth disorders in children, such as stunting. Characterized by a child's height being shorter than the age-appropriate standard, stunting is the result of chronic malnutrition due to prolonged insufficient nutrient intake. The first two years of life, commonly known as the first 1,000 days, mark a pivotal stage for a child's development and growth, highlighting the family as the primary setting for nurturing and caregiving. Recognizing this, the government has prioritized a family-centered approach to stunting prevention. Stunting poses a significant threat to human quality and national competitiveness in the future, as it not only impairs physical growth but also brain development, potentially hindering educational achievements, productivity, and creativity. During this period, babies must receive sufficient and appropriate nutrition to avoid malnutrition, which can lead to stunting [2]. Infants and toddlers face serious short-term consequences from stunting, including increased morbidity and mortality risks. Over time, stunting also affects intellectual and cognitive abilities in the medium term. In the long term, stunting negatively impacts the overall quality of human resources, influencing productivity and national development [4].

In 2018, South Sulawesi had a stunting prevalence of 35.7%, with several districts showing particularly high rates, such as Pangkep (50.5%) and Tana Toraja (47%). The national stunting rate that year was 30.8%, a significant decrease from previous years, as shown by Basic Health Research data, where stunting prevalence in 2007, 2010, and 2013 ranged between 34.6% and 37.2%. To further combat stunting in Indonesia, the government aimed to reduce the rate to 28%, a key objective outlined in the 2019 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) [5].

To address stunting, it is essential to educate the community on the importance of nutrition for pregnant women and toddlers. Research shows that health education interventions, designed with specific methods to prevent health problems, have significantly improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, highlighting the effectiveness of well-structured educational efforts [6]. Despite these educational efforts, changes in behavior and knowledge often prove short-lived, as evidenced by the persistence of issues, like stunting. An integrated strategy is required for effective stunting prevention, which includes improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as strengthening family support, the involvement of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and cultural factors.

The aim of the research was to analyze the connection between knowledge, attitude, actions, family support, the role of cadre-integrated health posts, food resilience, digital parenting, and the culture of mothers of toddlers at Marusu Health Center.

Instrument and Methods

This quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted in the Marusu Health Center area, focusing on regions with high stunting prevalence from August to September 2024. Primary data were collected through questionnaires given to respondents, while secondary data were sourced from the Marusu Health Center's reports. The study population comprised 341 pregnant women in the Marusu Health Center area in 2024, and total sampling was used to determine the sample size.

Data collection involved a combination of interviews, observations, and questionnaires. Interviews were conducted with mothers of toddlers (children under five years old) who experience stunting, to gather information about the data and other relevant details related to the issue being studied, as well as to focus on the research subject. Observations were made to thoroughly study the subjects, specifically stunted children, by directly observing factors related to the research at the study location, such as knowledge, attitudes, actions, family support, the role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and the cultural influences on mothers of toddlers. Additionally, a questionnaire was administered to assess and analyze their knowledge, attitudes, actions, family support, the role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and cultural influences. The questionnaire included pre-formulated questions with multiple-choice answers for the respondents. It consisted of 132 items based on a four-point Likert scale and a two-point Guttman scale. Construct validity was measured using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), with an average validity result of 0.85 and a Cronbach's Alpha reliability of 0.90.

The analysis process involved three techniques, including univariate analysis to describe the characteristics of both independent and dependent parameters, bivariate analysis to determine the relationship between independent and dependent parameters, and multivariate analysis to identify the independent parameters that have the greatest influence on the dependent parameter. A multivariate test was conducted using several logistic regression analyses, as the dependent parameter was categorical. This approach aimed to combine various independent parameters that are considered most effective in predicting the dependent outcomes.

Findings

A total of 341 pregnant women participated in the research (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of pregnant women’s demographic characteristics

Most mothers reported a pregnancy interval of one year or less. Also, the nutritional status of most toddlers was normal (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of respondents based on maternal and child health in the Marusu Health Center working area, Maros Regency in 2024

Most respondents reported not enough level of knowledge and the lack of factors affecting stunting incidents. Also, family support was reported to be enough by most subjects (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of respondents based on knowledge, affective factors, actions, family support, role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and culture with stunting incidents at Marusu Health Center in 2024

Discussion

The aim of the research was to analyze the connection between knowledge, attitude, actions, family support, the role of cadre-integrated health posts, food resilience, digital parenting, and the culture of mothers of toddlers at Marusu Health Center. The findings indicated that a significant proportion of respondents had three or fewer children (87%) and five or fewer household members (86.5%). This suggests that the families in this study were predominantly small to medium-sized, which may affect their capacity to provide sufficient attention and resources for the health and well-being of each child. Smaller families can often focus more on care and nutrition, which may help control the risk of health problems in children, including stunting. However, the increasing number of family members, if not matched by an increase in income, may result in the uneven distribution of food consumption. The available food for a larger family may only be sufficient for a family half its size, and such conditions may not be enough to prevent nutritional disorders in larger families [7].

A significant majority of respondents possessed a high school education (52.2%), while only a small proportion had a bachelor's degree (2.6%). This indicates that maternal education plays a crucial role in shaping knowledge about nutrition and child health. Mothers with higher educational attainment are likely to have better access to health information and greater awareness of the importance of proper nutrition and effective parenting practices [8]. Given that most respondents have completed high school or less, it is essential to prioritize educational programs focusing on nutrition and child health in the Marusu Health Center service area.

The working mother factor does not play a central role in causing child nutritional problems, but work is mentioned as a factor influencing the provision of food, nutrients, and child care [9]. In terms of employment, 92.1% of respondents were housewives. This suggests that these mothers were more focused on household chores and caring for their children rather than working outside the home. Although the role of a housewife allows more time to care for children, the availability of accurate information and support from maternal and child health programs is crucial in efforts to improve children's nutritional status, particularly in preventing stunting.

Based on maternal health data, the majority of mothers (85.6%) were not classified as high-risk according to their age at delivery. However, 14.4% of mothers fell into the risk category, which requires special attention, as giving birth at too young or too old an age is associated with an increased risk of health complications for both the mother and baby. This can include stunting in children due to psychological influences [10]. Young mothers often lack preparedness for pregnancy and may be unfamiliar with proper prenatal care, while older mothers typically experience reduced stamina and diminished motivation in managing their pregnancies.

Given that pregnancy spacing is a crucial determinant of children's health, it can be concluded that inadequate pregnancy spacing contributes to the occurrence of stunting. Close birth spacing can lead to stunting because it affects parenting patterns, as mothers may not have fully recovered from the previous pregnancy, both physically and nutritionally. In this study, 36.6% of mothers had a pregnancy spacing of equal or less than one year. Pregnancy spacing that is too short is known to increase the risk of stunting in subsequent children. The risk of stunting is significantly higher for children with a birth interval of less than two years, being 11.65 times greater than for children with a birth spacing of two years or longer [11].

The nutritional status of toddlers, as assessed by height-for-age, showed that 14.1% of children fell into the "very short" category, while 13.5% were classified as "short." This indicates that nearly 30% of children experience growth problems that can be categorized as stunting. Socio-demographic factors, such as maternal education, economic conditions, and employment, can influence this nutritional status, particularly in families with limited resources. Intervention efforts targeting high-risk families are essential to improve stunting conditions. The fact that 27.3% of toddlers were experiencing stunting confirms that it remains a significant health issue in the study area. Given that the majority of mothers were housewives with secondary education, intervention programs focusing on nutrition education, increasing access to nutritious food, and regular monitoring of maternal and child health are necessary. Health programs, such as integrated service post and nutrition counseling should be maximized to provide relevant information to these mothers.

The study results highlight the importance of addressing socio-demographic factors and maternal and child health in efforts to prevent stunting. Limited maternal education and work as housewives may restrict access to essential health information, particularly regarding a balanced diet and nutrition for toddlers. Therefore, affordable and easily accessible nutrition and health counseling for the community, especially in rural areas, is needed to reduce stunting rates. Additionally, increasing education about family planning and ideal birth spacing will help reduce health risks for mothers and children, ultimately contributing to a decrease in stunting prevalence in the area.

Theoretically, maternal age at birth is a significant risk factor for stunting. Mothers who give birth at too young an age (<20 years) or too old (>35 years) are at higher risk of experiencing pregnancy and birth complications, which can directly affect the health of the baby [10]. Maternal age significantly influences pregnancy health, as younger mothers may lack the physiological maturity required for a healthy pregnancy, while older mothers are often at heightened risk for chronic health conditions such as hypertension and gestational diabetes, both of which can adversely impact fetal growth. Previous studies have shown that mothers who give birth at a young age often face difficulties in providing proper nutrition to their children, due to both limited knowledge and physical and emotional capacity [8].

This research demonstrated that maternal age during childbirth was not significantly related to the incidence of stunting in children, from a statistical standpoint. One possible explanation is the presence of other, more dominant parameters, such as access to good health care during pregnancy, family support, or socio-economic status. These factors may have a greater impact on preventing or worsening stunting, even though maternal age is theoretically a risk factor. In addition, the development of better health services to support mothers at various ages can reduce the risk of stunting, thereby diminishing the influence of age as a single factor. Further research that considers the interaction between age and socio-economic conditions may be necessary to explain this relationship more comprehensively.

The attitudes of mothers toward their children's health and nutrition reflect their perceptions of the importance of nutrition in fostering children's growth and development. According to cognitive behavioral theory, positive attitudes are typically translated into actions that support children's health, such as choosing nutritious foods and ensuring regular health checks. Research shows that a good attitude toward healthy eating patterns can contribute to stunting prevention.

The results of this study indicated that there was no substantial correlation between maternal attitudes and the occurrence of stunting. One possible explanation is that, although mothers may have positive attitudes, the actual implementation of these attitudes into real actions may be influenced by external constraints such as economic access, lack of social support, or dietary patterns that are already ingrained in family culture [12]. Additionally, positive attitudes also require knowledge and skills to implement appropriate actions, which are not always available in all socio-economic contexts [9]. Therefore, efforts to prevent stunting should include aspects of education and attitude change, along with practical support to help overcome obstacles in implementing actions.

Maternal actions, such as providing nutritious food and proper health care, play a crucial role in preventing stunting. According to health behavior theory, positive actions in child care, including exclusive breastfeeding and the timely introduction of complementary foods, can reduce the risk of malnutrition and stunting [13]. Despite this, the findings of the study showed that maternal actions do not have a statistically significant relationship with the prevalence of stunting. This suggests that, although maternal actions are important, other factors, such as social support, access to health facilities, and adequate knowledge about nutrition, also influence these outcomes [14]. While mothers may perform beneficial actions, success in preventing stunting is also influenced by limited access to resources and a supportive environment. The availability of health services and dietary habits within households may further contribute to the association between maternal actions and the incidence of stunting.

Family support is often considered a crucial factor in ensuring that mothers have a supportive environment to care for their children. Support from other family members, such as partners or grandparents, can assist mothers in caring for their children and providing an environment conducive to their children’s growth and development [15]. Effective support can help mothers overcome the challenges of providing adequate nutrition for their children. However, this study found that family support was not significantly associated with stunting. This may suggest that the type of support mothers receive is not directly related to aspects of children’s nutrition and health. For example, emotional support alone may not be sufficient to prevent stunting if it is not accompanied by practical support, such as help with preparing nutritious food or access to health services. This indicates that intervention programs should focus on improving the quality of family support, particularly in terms of childcare and meeting nutritional needs.

The involvement of integrated service post is crucial in delivering nutrition education and essential health services to mothers and children. Through direct community engagement and consistent monitoring of child development, they effectively disseminate information about optimal nutrition practices, as outlined in the theory of innovation diffusion [16]. The findings of this study showed that there was no significant association between the engagement of integrated service post and the occurrence of stunting, likely due to their limited capacity and resources to effectively implement their duties. Additionally, the infrequency of cadre visits may be insufficient to substantially influence stunting prevention. Therefore, enhancing training and support for integrated service post is essential to empower them to take a more proactive and effective role in stunting prevention within the community [17].

The findings indicated that the correlation between food security and the incidence of stunting was not statistically significant. While mothers experiencing food insecurity had a higher percentage of stunted children (22.3%) compared to those with adequate food security (27.3%), this disparity did not meet the threshold of statistical significance necessary to infer a strong effect. Family food security is closely linked to food availability, which is one of the factors or indirect causes affecting children's nutritional status [18]. Sufficient access to nutritious food is crucial for preventing malnutrition and stunting. Nonetheless, the findings of this study suggest that food security alone is insufficient to guarantee that children receive the necessary nutrition for optimal growth. Other factors, such as daily dietary patterns, food diversity, and healthy eating habits, may have a more significant impact on children's nutritional status. Previous research has demonstrated that even in situations of adequate food security, a lack of variety in food choices can still put children at risk of malnutrition and stunting [19]. Additionally, factors, such as nutrition education, culinary skills, and food expenditures play a significant role in determining the quality of consumed food. Food security that solely assesses physical access to food may not adequately represent effective nutritional intake. Therefore, further research is necessary to investigate the intricate relationships between food security, dietary practices, and children's nutritional status, as well as to understand how daily eating habits and food selections may more directly influence the risk of stunting.

The study results showed that there was no significant association between digital parenting and the prevalence of stunting. Although mothers who did not practice digital parenting had a lower proportion of stunted children (7%) compared to those who did (20.2%), this difference was not strong enough to be considered statistically significant.

The theory of media use states that digital technology can provide parents with quick and easy access to health and nutrition information [20]. In the context of parenting, technology can be a useful tool for obtaining accurate information on how to care for and nourish children. However, these results suggest that digital parenting alone may not be enough to address stunting. It is possible that, although parents receive good information through digital media, the implementation of this information in daily practice may be hindered by other factors, such as limited resources, cultural habits, or inadequate social support.

In addition, although mothers who practiced less digital parenting showed a lower proportion of stunted children, this may indicate that more traditional physical interactions and parenting may have a greater positive impact on child growth. Previous research has shown that direct involvement in parenting, such as feeding, attention to hygiene, and positive social interactions, can be more influential in preventing stunting than simply receiving information through technology.

Therefore, further research is needed to explore more deeply how digital parenting and traditional parenting patterns interact and how both can be optimized to support healthy child development. This involves assessing the impacts, both positive and negative, of technology in parenting and how it can be seamlessly integrated with established parenting practices to effectively reduce the risk of stunting.

In the context of stunting, cultural influences are often related to dietary practices, childcare methods, and health behaviors that are passed down from one generation to the next. Grounded in sociocultural theory, the customs and values characteristic of a culture can shape maternal and child health practices, especially regarding nutrition and care. A positive or beneficial culture is typically associated with practices that support optimal child growth, such as ensuring balanced nutrition, cleanliness, and access to health services [21].

However, the results of this study indicated that the correlation between cultural factors and the occurrence of stunting was not statistically significant. Despite this, mothers with less favorable cultural practices had a higher proportion of stunted children (16.1%) compared to those with more favorable cultural practices (11.1%). Each community has different cultural norms, which affect children's health both directly and indirectly [22]. Simple measurements may not be sufficient to capture the complexity of culture, which can lead to statistically insignificant results. Culture does not stand alone but often interacts with socioeconomic factors, such as income, education, and access to health services. For example, mothers with favorable cultural practices may be more exposed to health information and have better access to resources. Conversely, mothers with less favorable cultural practices may face greater economic or social challenges. The interaction of these factors can obscure the direct influence of culture, making it harder to observe a significant relationship. Although culture can influence family diets, many other parameters also determine a child's nutritional status. For example, even though a culture may encourage the consumption of certain foods, the nutritional quality of those foods is also important. In some cases, cultures may emphasize foods rich in carbohydrates but low in protein or micronutrients, which may increase the risk of stunting, even though the diet is considered "good" from a cultural perspective [22-30].

These non-significant results may also suggest the need for more culturally specific interventions. Interventions based solely on culture may not be effective without addressing more specific local needs, such as adapting to modern nutritional practices or modifying parenting behaviors. In some communities, cultural factors may play a significant role in parenting practices, but culturally based interventions must be tailored to the local context to be effective.

Conclusion

There is no statistically significant relationship between knowledge, attitudes, actions, family support, the role of integrated service post, food security, digital parenting, and cultural influences and the incidence of stunting in the Marusu Health Center region.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all contributors, especially the staff of the Marusu Health Center, for their invaluable support throughout the research process. They also acknowledge the financial assistance from the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service, Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, which significantly contributed to the research, writing, and publication of this article as part of the fundamental regular research program.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Committee for Health Research at the Faculty of Health Sciences "Maluku Husada" issued an ethics permit to protect the human rights of individuals participating in health research after reviewing the relevant research protocols. This approval can be identified by the registration number RK. 177/KEPK/STIK/VIII/2024.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Alwi MK (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%); Yusriani Y (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Purnawansyah P (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: Financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article was provided by the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Services under the Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology at the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, as part of the Master Thesis Research Scheme.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Social Determinants of Health

Received: 2024/09/25 | Accepted: 2024/10/26 | Published: 2024/11/1

Received: 2024/09/25 | Accepted: 2024/10/26 | Published: 2024/11/1

References

1. Munir Z, Audyna L. The effect of education about stunting on the knowledge and attitude of mothers who have stunting children. Prof Nurs J. 2022;10(2):29-54. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.33650/jkp.v10i2.4221]

2. Hizriyani R. Exclusive breastfeeding as stunting prevention. J Mothers Window Progr Stud. 2021;8(2):55-62. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.32534/jjb.v8i2.1722]

3. Nuradhiani A. Exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding for stunting in developing countries. J Nutr Work Product. 2020;1(1):23-8. [Indonesian] [Link]

4. Murni M, Yusuf K, Rahmaniar A, Masithah St, Syafruddin. The relationship between mother's knowledge and stunting prevention behavior in the Patimpeng community health center work area. Miracle J Public Health. 2024;7(1):66-74. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.36566/mjph.v7i1.350]

5. Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. Results of the 2022 Indonesian nutritional status survey (SSGI). Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia; 2022. [Indonesian] [Link]

6. Andriani WOS, Rezal F, Nurzalmariah WOS. Differences in knowledge, attitude, mothers, and motivation of mothers after being given the mother smart grounding (MSG) program in preventing stunting in the work area of Puwatu health center, Kendari city in 2017. JIM KESMAS. 2017;2(6):1-9. [Indonesian] [Link]

7. Nurfuadi N, Prastowo OD, Rizkiana YI. Optimizing stunting handling through improving childcare patterns in digital era families in Klampok village, Banjarnegara. KAMPELMAS. 2024;3(1):469-77. [Indonesian] [Link]

8. Najah S, Darmawi D. The relationship between maternal factors and the incidence of stunting in Arongan village, Kuala Pesisir district, Nagan Raya regency. J Biol Educ. 2022;10(1):45-55. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.32672/jbe.v10i1.4234]

9. Amazihono IK, Harefa EM. The relationship between socioeconomic and maternal characteristics with the incidence of stunting in toddlers. JURNAL ILMIAH PANNMED. 2021;16(1):235-42. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.36911/pannmed.v16i1.1058]

10. Trisyani K, Fara YD, Mayasari AT, Abdullah. The relationship between maternal factors and the incidence of stunting. AISYAH Matern J. 2020;1(3):189-97. [Indonesian] [Link]

11. Jayanti R, Ernawati R. Pregnancy spacing factors related to stunting incidence at Harapan Baru public health center, Samarinda Seberang. Borneo Stud Res. 2021;2(3):1705-10. [Indonesian] [Link]

12. Deviyanti NWS. Description of knowledge, attitudes and behavior of mothers in efforts to prevent stunting in Mengani village. Denpasar: Bali Appropriate Technology Institute; 2022. [Indonesian] [Link]

13. Sulistyoningsih H. The relationship between parity and exclusive breastfeeding with stunting in toddlers (literature review). J Semin Nas. 2020;2(1):1-8. [Indonesian] [Link]

14. Natalia V, Hertati D. Analysis of factors affecting stunting incidence in central Kalimantan based on literature review. Surya Med J. 2023;9(3):181-9. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.33084/jsm.v9i3.6487]

15. Wahyu A, Ginting L, Sinaga ND. Number of children, child birth spacing and father's role with stunting incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Silampari Nurs J. 2022;6(1):535-43. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.31539/jks.v6i1.4554]

16. Najdah N, Nurbaya N. Innovation in the implementation of integrated health posts during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study in the Campalagian health center working area. Manarang Health J. 2021;7:67. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.33490/jkm.v7iKhusus.548]

17. Wahyuningtyas W, Sufyan S, Health FI, Manggis K. Empowering the creativity of Posyandu cadres. SABDAMAS. 2019;1(1):218-22. [Indonesian] [Link]

18. Wado LAL, Sudargo T, Armawi A. Socio-demographics of family food security in relation to stunting incidence in children aged 1-5 years (study in the working area of Bandarharjo health center, Tanjung Mas village, North Semarang district, Semarang city, Central Java province). Natl Resil J. 2019;25(2):178-203. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.22146/jkn.45707]

19. Permatasari TAE, Turrahmi H, Illavina I. Balanced nutrition education for posyandu cadres during the Covid-19 pandemic as prevention of toddler stunting in Bogor regency. AS-SYIFA. 2020;1(2):67-77. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.24853/assyifa.1.2.67-78]

20. Silalahi RR, Mardani PB, Christanti MF. Improving digital health literacy for housewives at Flamboyan health post, Bekasi. J Dedicators Community. 2020;4(1):57-67. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.34001/jdc.v4i1.993]

21. Ibrahim I, Alam S, Adha AS, Jayadi YI, Fadlan M. Socio-cultural relationship with stunting incidence in toddlers aged 24-59 months in Bone-Bone village, Baraka district, Enrekang regency in 2020. AL GIZZAI Public Health Nutr J. 2021;1(1):16-26. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.24252/algizzai.v1i1.19079]

22. Oktafiani V, Asriani A, Ainayah A, Abrar VA. How do socio-cultural factors affect stunting incidence in tolaki children?. MURHUM J Early Child Educ. 2024;5(1):874-86. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.37985/murhum.v5i1.401]

23. Yusriani Y, Alwi MK, Herli A, Syahrani V. Structural equation modeling for skills analysis of health cadres based on knowledge and attitudes about health promotion and body immunity of pregnant women. J Educ Health Promot. 2024;13(1):275. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1565_23]

24. Yusriani Y, Alwi MK, Agustini T, Septiyanti S. The role of health workers in implementing of childbirth planning and complication prevention program. Afr J Reprod Health. 2022;26(9):142-52. [Link]

25. Spence AC, Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, McNaughton SA, Hesketh KD. Mediators of improved child diet quality following a health promotion intervention: The Melbourne InFANT program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:137. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12966-014-0137-5]

26. Zaragoza Cortes J, Trejo Osti LE, Ocampo Torres M, Maldonado Vargas L, Ortiz Gress AA. Poor breastfeeding, complementary feeding and dietary diversity in children and their relationship with stunting in rural communities. Nutr Hosp. 2018;35(2):271-8. [Link] [DOI:10.20960/nh.1352]

27. Hewett PC, Willig AL, Digitale J, Soler-Hampejsek E, Behrman JR, Austrian K. Assessment of an adolescent-girl-focused nutritional educational intervention within a girls' empowerment programme: A cluster randomised evaluation in Zambia. Public Health Nutr. 2020;24(4):1-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1368980020001263]

28. Schrijner S, Smits J. Grandparents and children's stunting in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2018;205:90-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.037]

29. McClintic EE, Ellis A, Ogutu EA, Caruso BA, Ventura SG, Arriola KRJ, et al. Application of the capabilities, opportunities, motivations, and behavior (COM-B) change model to formative research for child nutrition in Western Kenya. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;6(7):nzac104. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/cdn/nzac104]

30. Apriluana G, Fikawati S. Analysis of risk factors of stunting among children 0-59 months in developing countries and Southeast Asia. Dep Public Health Nutr. 2018;28(4):247-56. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.22435/mpk.v28i4.472]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |