Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 571-579 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Namdar Ahmadabad H, Rajabzadeh R, Hosseini S, Jafarimoghadam A. Evaluating Health Promotion Standards in Educational Hospitals Affiliated with North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :571-579

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76826-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76826-en.html

1- Vector-borne Diseases Research, Center, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

3- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

4- Vice-Chancellor of Treatment Affairs, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

3- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

4- Vice-Chancellor of Treatment Affairs, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 651 kb]

(2160 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (923 Views)

Full-Text: (212 Views)

Introduction

In accordance with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition, health is delineated as “not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, but a state of comprehensive physical, social, and mental well-being.” Consequently, endeavors aimed at enhancing these facets of health, including education, disease prevention, and rehabilitation, are considered health promotion initiatives. Multiple environments, such as schools, workplaces, residential areas, and hospitals, have the potential to contribute significantly to the promotion of health [1].

Hospitals account for over 40% of healthcare costs and are often criticized for focusing solely on diagnostic and therapeutic activities [2]. The WHO proposes health-promoting hospitals (HPHs) as an effective strategy for reforming health services [3]. The WHO launched the HPHs project in 1988 with the goal of reducing costs, improving patient and staff satisfaction, and implementing effective preventive programs [4]. The WHO delineates HPHs as institutions that offer superior medical and nursing services while cultivating an organizational identity that aligns with health promotion objectives. These establishments actively develop a health-promoting organizational structure and culture, which incorporates proactive and cooperative roles for patients and all employees. In addition, HPHs transform themselves into environments that foster well-being and health, ultimately encouraging collaborative relationships with the surrounding community [5]. HPHs aim to address the physical, mental, and social needs of patients, staff, organizations, and society, focusing on management policy, patient assessment and intervention, promoting a healthier work environment, and ensuring continuity and cooperation [6].

HPHs focus on the needs of patients and their companions, serving as the foundation for fostering a healthy lifestyle for both patients and society. These institutions encourage staff to adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle and strive to enhance overall health by mitigating environmental risks. Furthermore, they promote staff well-being [5, 7].

The international network of HPHs has experienced consistent growth, with over 900 hospitals and health service centers in more than 40 countries participating [8]. Most of these are located in developed countries, but health promotion programs in developing countries are gaining attention, albeit at a slower pace [2].

The first studies examining the condition of Iranian hospitals in terms of health promotion standards (HPSs), as set by the WHO, were conducted in 2013 [9]. Since then, studies have been carried out in various city hospitals in this field. Hamidi et al. reviewed studies pertaining to the state of Iranian hospitals with respect to the WHO’s HPS, announcing that there are several limitations. Firstly, the number of studies related to HPHs is limited, and more research is needed. Secondly, the findings of these studies demonstrate that Iranian hospitals need to achieve optimal conditions regarding HPS [10].

In previous studies, HPSs in Iranian hospitals have been evaluated either internally by hospital staff or externally by a group of researchers. Additionally, all these studies have utilized the WHO’s self-assessment tool to evaluate the state of HPS in hospitals [10].

Yaghoubi and Javadi emphasize that the effective implementation of hospital health promotion programs across different societies is influenced by the culture, values, and beliefs of those societies [9]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider adapting the evaluation tool for health promotion hospitals to local contexts. Believing that the self-assessment tool for improving hospital health should be appropriate to the cultural, social, political, economic, and health contexts of Iran, previous studies have localized the WHO’s self-assessment tool for health promotion to make it more practical and collaborative [11-13].

The term “HPHs” is relatively new in Iran, and there have been limited studies on this topic. Previous research has been conducted in a single center or specific clinical departments, using non-native evaluation tools and without simultaneous internal and external evaluations. These limitations have been identified in earlier studies. Thus, the present study aimed to determine the state of HPSs in educational hospitals affiliated with North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (NKUMS) using both internal and external evaluation methods.

Instrument and Methods

Subjects

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was conducted at educational hospitals affiliated with NKUMS in 2023. A census sampling method was utilized to select the educational hospitals. The criteria for participation in the study included the satisfaction of hospital officials and the willingness of the hospital accreditation team. All educational hospitals affiliated with NKUMS were included in this study. The educational hospitals of NKUMS, which include Imam Reza, Imam Hassan, Imam Ali, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals in Bojnourd city, as well as Khatam and Imam Khomeini hospitals in Shirvan city, were considered the research community.

Data collection tool

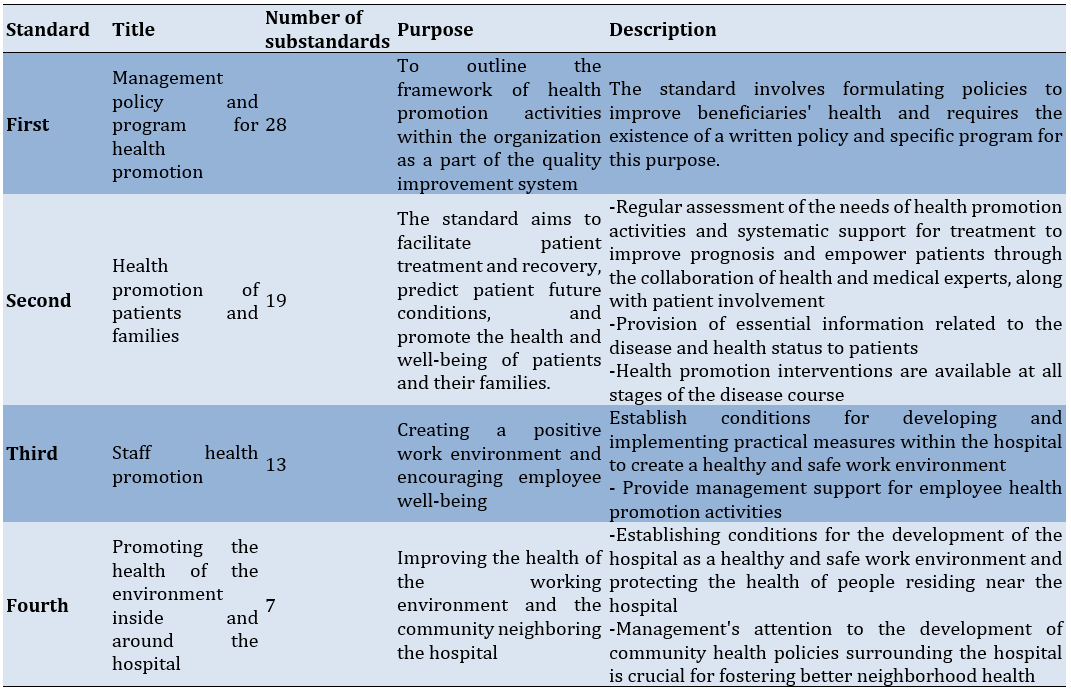

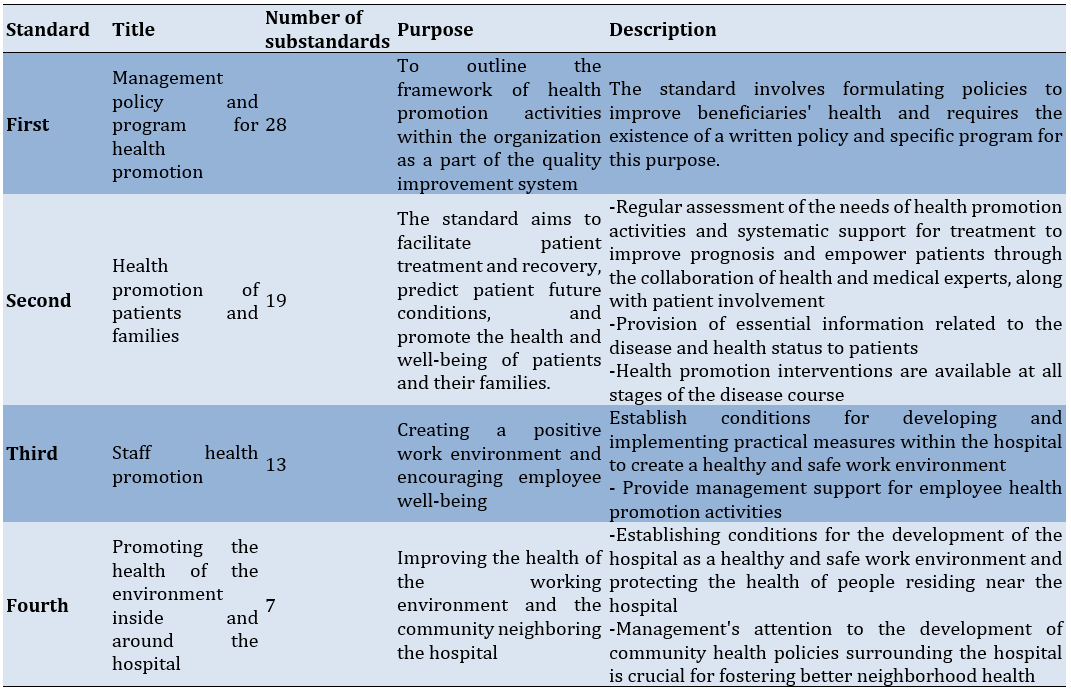

In this study, the WHO self-assessment tool for health promotion in hospitals was employed. This tool had previously been translated, localized, and validated in the Persian language in Iran [11, 13]. The tool included four standards and 67 substandards, with an average content validity index of 0.867 for the entire tool. The internal reliability of the tool was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha index, with results ranging from 78.1% to 95.5% for the four standards and a Cronbach’s alpha of 90.02% for the entire tool. The intragroup correlation coefficient value was 0.87, indicating acceptable stability of the tool (Table 1).

We utilized a five-point grading system to assess the degree of fulfillment for each substandard associated with HPSs. The grading system includes grade A (fully achieved substandard with a score of 9-10), grade B (substandard with high progress with a score of 7-8), grade C (substandard with moderate progress with a score of 5-6), grade D (substandard with low progress with a score of 3-4), and grade E (substandard with intention to start with a score of 1-2). In this tool, the evaluators scored the status of each substandard through observations, documents, and interviews.

Table 1. Standards for evaluating health promotion hospitals

The process of evaluating health promotion standards

An internal evaluation team was established in each hospital to assess the HPSs in educational hospitals. Hospital staff members who participated in the hospital’s accreditation and quality improvement programs and possessed adequate knowledge about the hospital’s activities related to HPSs, as well as documentation of these activities, were selected for the internal evaluation team of each hospital. The team consisted of the hospital manager, accreditation officer, quality improvement officer, educational supervisor, environmental health officer, social worker, patient education officer, and health promotion unit officer.

During a meeting with each hospital’s internal evaluation team, the evaluation objectives, HPS, evaluation tool, and methodology for scoring each substandard related to the hospitals’ HPS were explained. The members of the internal evaluation team completed the evaluation forms based on observations, documents, and interviews.

For the external evaluation of HPS, the research team, which included health education and health promotion specialists, as well as the manager of the accreditation unit of the Vice-Chancellor of Treatment Affairs of NKUMS, visited the hospital. In collaboration with the hospital’s head manager, they interviewed hospital staff, patients, and family members, performed observations, and reviewed existing documents to complete the evaluation forms.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 9 software was utilized to conduct the statistical analysis in this study. A significance level of less than 0.05 was considered for all tests performed. Descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequency, mean, and standard deviation, were employed to address the research objectives. The total score of each hospital and the score of each standard were presented as mean±standard deviation. To compare the results across different groups, descriptive statistical methods were used to extract and analyze the data. Mean and standard deviation were used for analyzing quantitative data, while frequency and percentage were employed for qualitative data. The normality of the distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Additionally, the independent sample t-test was performed to compare the average scores of each standard among different types of hospitals, locations, and numbers of hospital beds.

Findings

Analysis and comparison of internal and external evaluation scores for health promotion standards

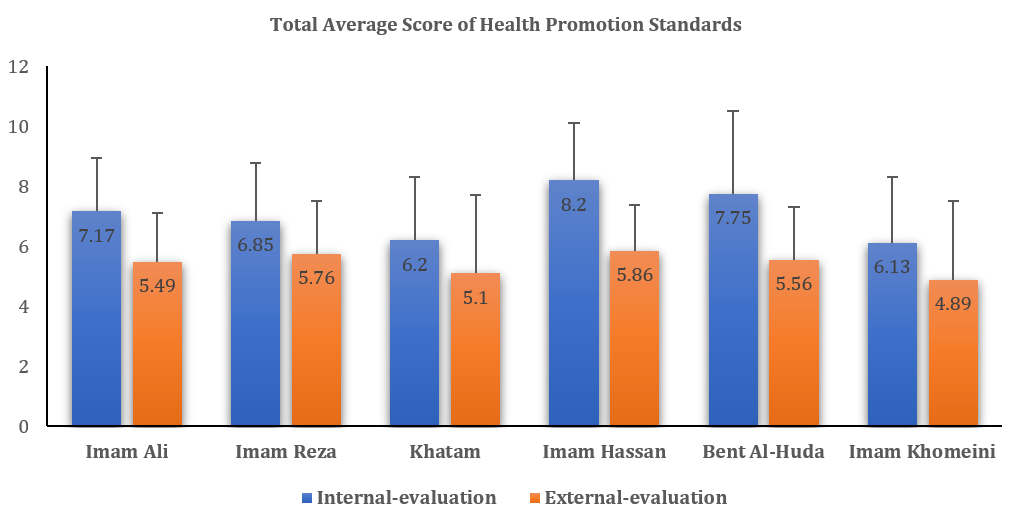

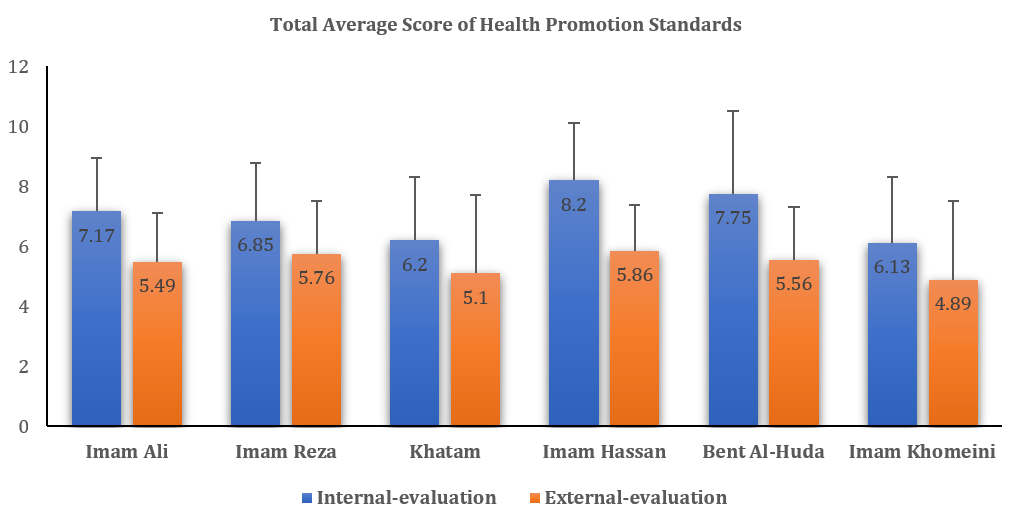

The internal evaluations revealed that educational hospitals have made significant progress in promoting health standards, with a total average score of 7.05±2.25. This score indicates a strong emphasis on health promotion and demonstrates high progress. Three hospitals—Imam Ali, Imam Hassan, and Bent Al-Huda—achieved the highest scores in the internal evaluation (Figure 1). When comparing the different standards, the highest score was related to the standard for health promotion of patients and families (8.05±1.69), while the lowest score was associated with the standard for health promotion of staff (6.37±2.31).

The total average score of the external evaluation was 5.44±2.04, indicating a 50% improvement in hospital HPSs. Notably, all hospitals evaluated for HPS were in the moderate stage of progress, except for Imam Khomeini Hospital, which was in the low stage of progress (Figure 1). In alignment with the internal evaluation results, the highest average score in the external evaluation was related to the standard for health promotion of patients and families (6.86±1.41), while the lowest total average score was associated with the standard for health promotion of staff (7.00±1.83).

Figure 1. Comparison of average internal and external evaluation scores for health promotion standards in different educational hospitals

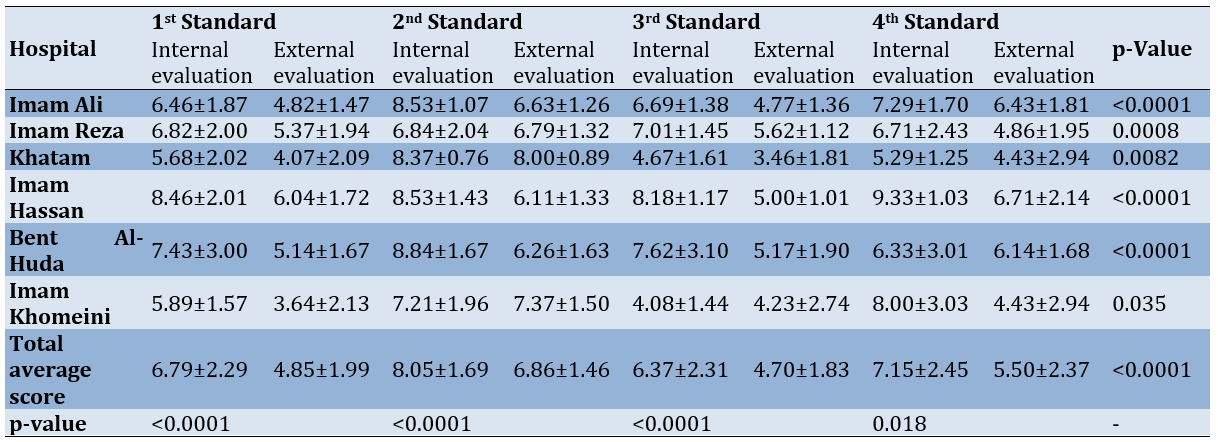

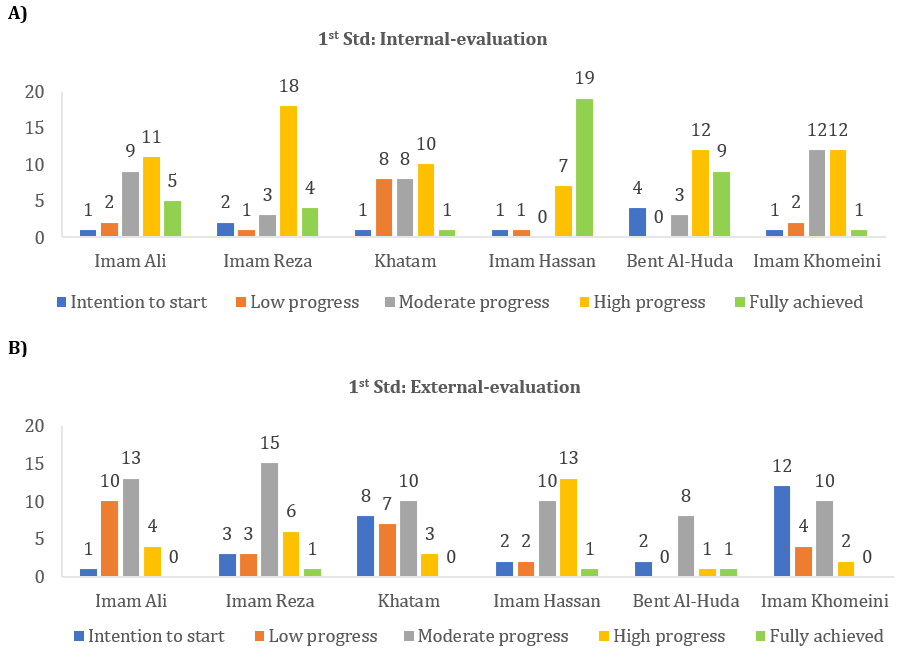

Our results showed that the average scores of internal evaluations were significantly higher than those of external evaluations in each of the educational hospitals (p<0.05). Furthermore, the comparison of each HPS indicated that the average score of the external evaluation for each standard was significantly higher than the average score of the internal evaluation (p<0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the average scores of internal and external evaluation of health promotion standards in hospitals

We compared HPS scores across different hospital characteristics. Our research revealed a significant difference in scores related to the hospitals’ locations (p<0.05). However, we did not find any significant variation in the number of active beds, the number of staff members, or the hospital’s age (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of average health promotion standards scores among hospitals with different characteristics. The results are presented as Mean ± SD; a p-value less than 0.05 is considered significant

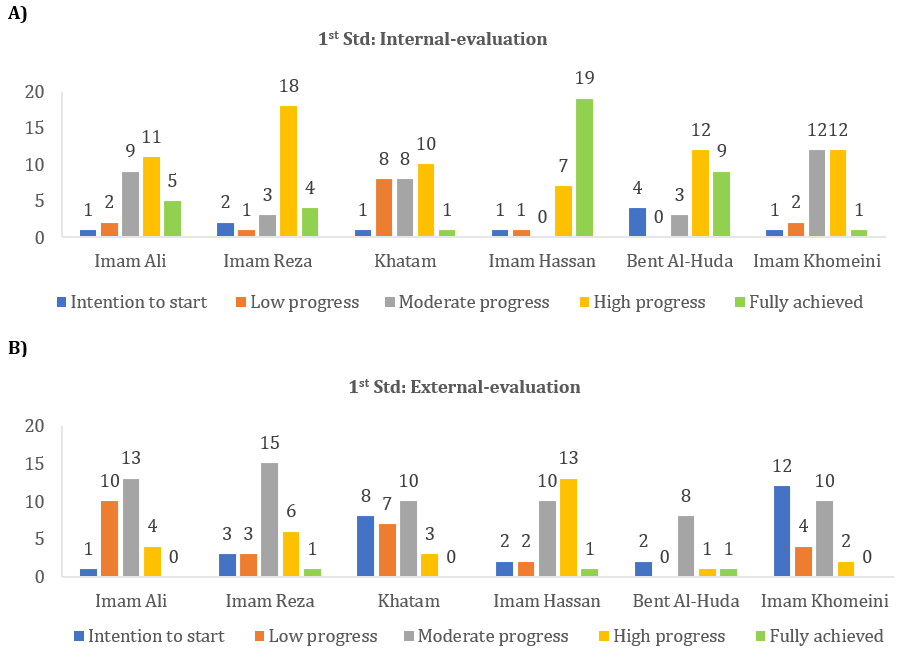

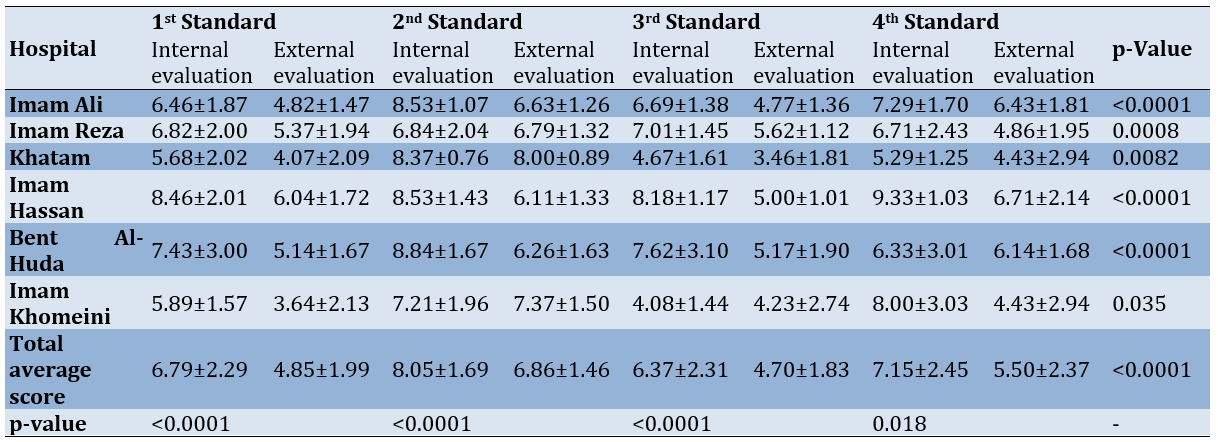

Evaluation of the first standard: Management policy and program

In the internal evaluation of various hospitals, the highest number of substandards for the first standard was observed in the state of high progress, while the lowest number of substandards was in the state of intention to start (Figure 2A). According to the results of this internal evaluation, all the hospitals in Bojnourd City obtained a total average score higher than six for this standard. In contrast, two hospitals in Shirvan City obtained a total average score of less than six.

The external evaluation results showed that most of the substandards related to the first standard were in a state of moderate progress, while the lowest number of substandards was in a fully achieved state (Figure 2B). In this evaluation, the three hospitals—Imam Hassan, Imam Reza, and Bent Al-Huda—achieved an average score of more than five (moderate progress). In comparison, the three hospitals—Imam Ali, Khatam, and Imam Khomeini—achieved an average score of less than five (low progress).

Among the various substandards of the first standard, “a clear statement to promote the health of neighbors around the hospital in the management policy of the hospital,” “determining a sufficient budget for health promotion services,” and “cooperation of the hospital with other partners (organizations and institutions) to ensure and improve the health of patients, staff, and neighbors” received the lowest scores and were in the state of intention to start. In other words, no action was taken regarding these substandards in the evaluated educational hospitals, but evidence of their intention to act in this regard has been observed.

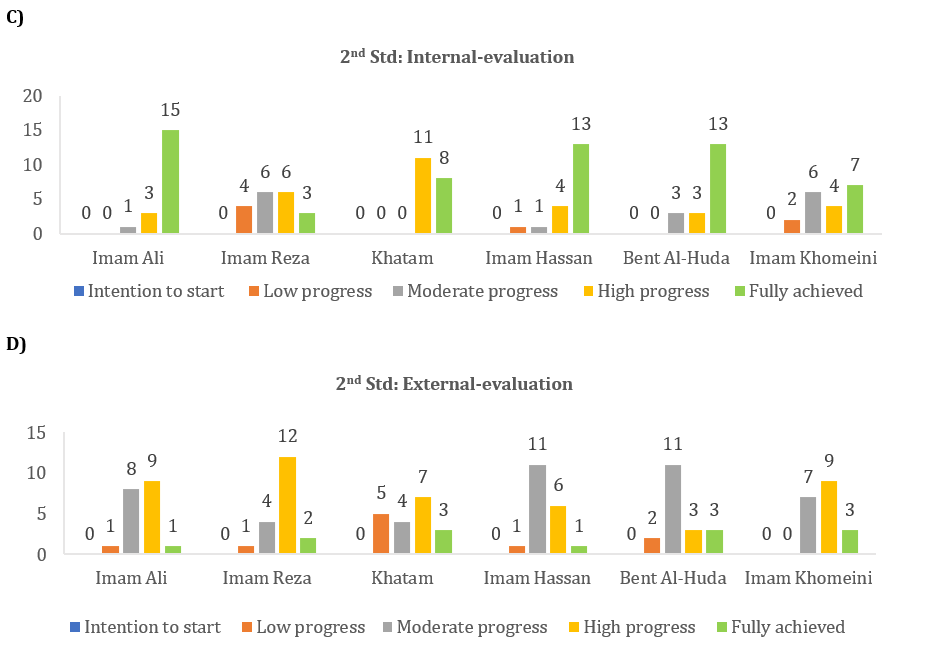

Evaluation of the second standard: Health promotion of patients and families

In the internal evaluation of health promotion for patients and families, most substandards were reported as fully achieved (Figure 2C). In all hospitals except Imam Reza, the total average score surpassed seven, indicating high progress in the second standard.

In the external evaluation, the majority of the substandards for the second standard were in a state of high progress (Figure 2D). The average total score for the second standard was over six in all hospitals.

Out of 19 substandards of the second standard, most hospitals showed low progress in four substandards. These substandards with low progress included “recording information about the factors influencing the health promotion of patients along with social and cultural factors in their files,” “recording a summary of the conditions and needs for health promotion of patients and the interventions performed in their files,” “recording health promotion activities and expected outcomes in patients’ files,” and “access of families and visitors to updated knowledge about health promotion.”

Figure 2. Status of the first and second standards based on the results of internal evaluation (A and C) and external evaluation (B and D) in educational hospitals

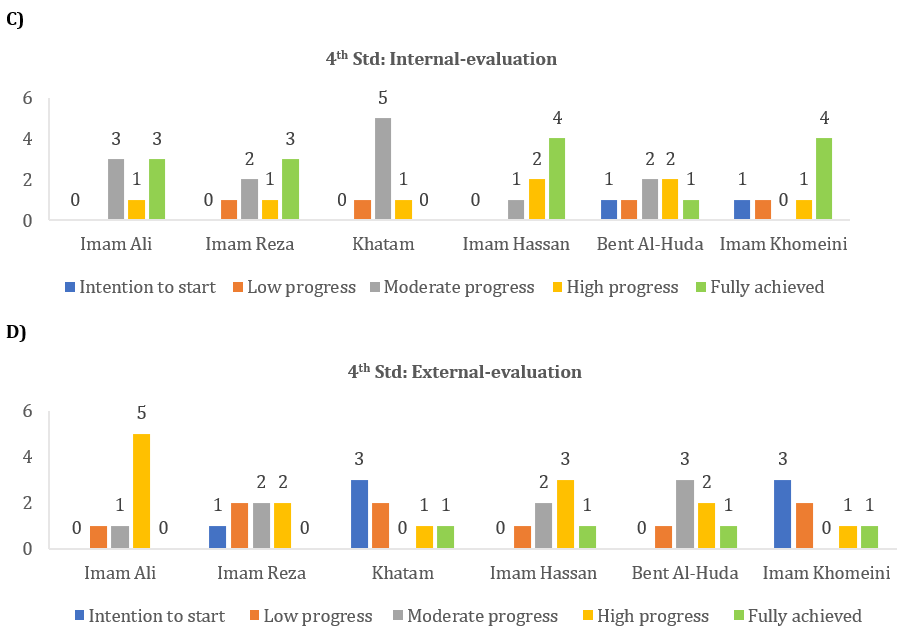

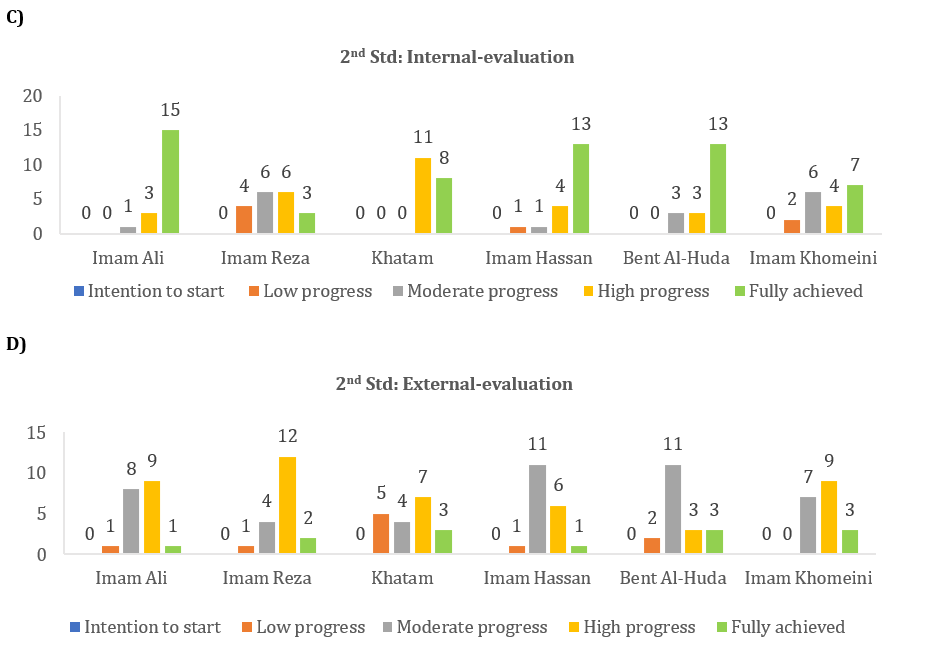

The third standard: Staff health promotion

In the internal evaluation of staff health promotion, most substandards showed moderate progress (Figure 3A). The average total score for Imam Hassan, Imam Reza, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals was above 7 (indicating a high progress state). In contrast, Imam Ali Hospital had an average total score of 6.69 (indicating a moderate progress state), while Khatam and Imam Khomeini hospitals had average total scores below five (indicating a low progress state).

The external evaluation results were consistent with the internal evaluation results, as most substandards of the third standard were also in the moderate progress state (Figure 3B). The average total score for Imam Hassan, Imam Reza, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals was above five, while the scores for Imam Ali, Khatam, and Imam Khomeini hospitals were below five.

Among the various substandards of the third standard, the evidence and documentation related to the substandards of “staff knowledge and awareness of health and safety promotion” and “planning of support and welfare services for hospital staff” were insufficient and in the state of intention to start.

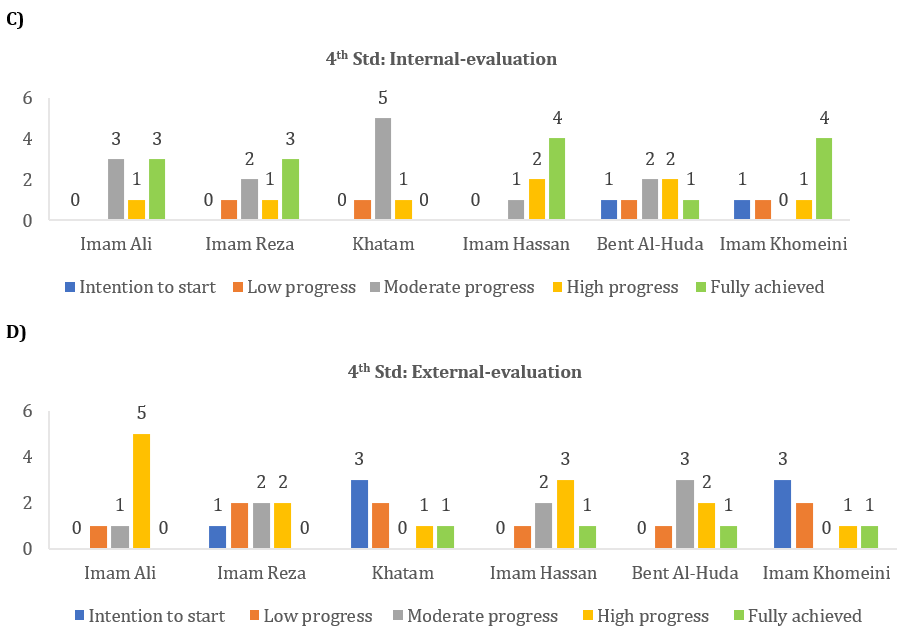

The fourth standard: Promoting the health of the environment inside and around the hospital

The internal evaluation results for the fourth standard showed that the majority of substandards were fully achieved (Figure 3C). Imam Hassan, Imam Khomeini, and Imam Ali hospitals achieved an average total score above seven, while Khatam and Bent Al-Huda hospitals scored between five and seven.

The external evaluation results indicated that the majority of the fourth standard’s substandards were in a high progress stage (Figure 3D). Imam Ali, Imam Hassan, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals achieved an average total score of over six, whereas Imam Reza, Khatam, and Imam Khomeini hospitals scored an average of less than five.

Our results showed that in most hospitals, the indicator “interventions related to the prevention and control of risk factors for neighbors of the hospital” was in the state of intention to start.

Figure 3. Status of the third and fourth standards based on the results of internal evaluation (A and C) and external evaluation (B and D) in educational hospitals.

Discussion

In the present study, the state of HPS in educational hospitals affiliated with NKUMS was investigated using both external and internal evaluation methods. Various studies have evaluated the state of HPSs in hospitals across different cities in Iran. The majority of these evaluations have been internal assessments conducted by the hospital staff themselves. Limitations of internal evaluation methods, such as bias, limited perspective, and potential conflict of interest, have undoubtedly impacted the results of these studies [14].

The results of the internal evaluation indicated that hospitals could be classified into two groups based on the implementation and fulfillment of HPSs, including the high-progress group and the moderate-progress group. Hospitals in the high-progress group showed clear evidence of their commitment to these standards, with 50% of the evaluated hospitals falling into this category. Meanwhile, the moderate-progress group represented hospitals that have made around 50% progress in implementing the standards, comprising the remaining 50% of the evaluated hospitals. The results of the external evaluation revealed that all hospitals exhibited moderate progress in the implementation of HPS, with only one hospital demonstrating low progress. The evidence suggests that the implementation of HPS in this hospital could be more cohesive.

In the current study, the internal evaluation results revealed that 50% of the hospitals were in a state of high progress, while the remaining 50% were in a state of moderate progress. Afshari et al. conducted a study investigating the state of health promotion in hospitals in Isfahan, Iran, reporting 55% of hospitals being at an average level, and only 11% of the internally evaluated hospitals being in good condition [15]. Pezeshki et al. found that the health promotion scores in hospitals in East Azerbaijan are at an average level [16]. Other studies performed in Gilan, Shiraz, Tehran, Mashhad, and Hamedan provinces in Iran, using the internal evaluation method, have reported that the hospitals’ scores for HPSs are average [9, 17, 18], with unfavorable conditions being noted in some cases [19]. A systematic review by Hamidi et al. analyzed studies on HPHs in Iran and found that the hospitals investigated are significantly weak in HPS [10]. Comparing the results of our study with previous studies reveals that North Khorasan hospitals have better condition in implementing HPS. Several factors could contribute to this difference, such as the focus on educational hospitals in our study, the timing of the study during a period when the concept of HPHs is more well-known and important, and the use of a modified self-assessment tool instead of the WHO self-assessment tool for data collection. Supporting our interpretation, Rezaei and Karamali’s study using a modified self-assessment tool to evaluate HPS, found an average score of 5.47 [11], similar to our external evaluation results, where the scores of most hospitals were within the range of five.

The internal evaluation scores of hospitals’ HPSs were significantly higher than the external evaluation scores. Although the results of the internal evaluation indicated better implementation of HPS in hospitals compared to external evaluations, both evaluation methods were consistent in identifying which hospital or standard was in a more favorable condition. Previous research has shown that evaluating hospital and health promotion programs internally by staff members produces more positive results than external evaluations [20, 21]. Our current study also supports this conclusion.

Previous studies have indicated that hospitals located in capital cities are in a better state regarding HPS compared to those in counties [10, 16]. In agreement with this statement, our results also showed that hospitals located in Bojnourd City, the capital of North Khorasan province, scored higher than hospitals in Shirvan County. We did not observe any significant differences in the HPS scores between hospitals with respect to the other three characteristics, such as the age of the hospital, the number of faculty members, and the number of active beds.

Management policy, health professional competencies, and financial budget are crucial for the successful implementation of a hospital program [22]. The standard of management policy and program is considered a fundamental issue in the implementation of health promotion hospitals. In the majority of prior studies conducted in Iran, the standard of management policy and program has received lower scores compared to other standards [10, 17, 19, 23]. However, in our research, this standard did not achieve either the lowest or the highest average score when compared to other standards; instead, it was in a state of moderate progress. The total average score of the internal evaluation for the standard of policy and management was 6.79 out of a possible ten, while the total average score of the external evaluation was 4.84 out of a possible ten. Continuous management support, transformative leadership, participatory strategic management, and expert governance can help hospitals focus on health promotion [24].

In the present study, the highest score was related to the standard of health promotion for patients and families. Pezeshki et al. [16] and studies conducted by Yaghoubi & Javadi and Taghdisi et al. report similar results [9, 23].

When comparing different standards, it was evident that the staff HPS received the lowest scores in both internal (4.7 out of ten) and external (6.37 out of ten) evaluations. This underscores a critical issue; while the investigated hospitals were effective in addressing patient and family health, their efforts in staff health promotion were lacking. Our hospitals need a comprehensive plan to address this standard. Previous studies in Iran have consistently highlighted the low scores for staff HPSs in hospitals [16, 18, 25]. This is concerning because hospital staff members play a crucial role in patient care, and their health directly impacts their performance, which in turn affects patient health. Therefore, it is imperative to support the creation of a safe and healthy work environment.

To create a healthy hospital environment, it is recommended to focus on trust, transparency, effective leadership, suitable employees, commitment to safety and ethical care, decision-making authority, professional knowledge, teamwork, active listening, open communication, skillful and healthy communication, and obtaining the required information [26, 27]. Sadeqi-Arani et al. suggest developing appropriate training programs for staff health promotion and encouraging staff participation in hospital policies to improve the standard of staff health promotion in HPHs [25].

Our review identified that the substandards “planning support and welfare services for hospital staff” and “staff knowledge and awareness about health and safety promotion” received the lowest scores. Previous studies in Iran emphasized healthcare workers’ dissatisfaction with support and welfare services due to a lack of attention to their actual needs, the absence of a comprehensive system, and the failure to consider staff characteristics and opinions [28, 29].

The study has several strengths, including the use of localized and valid evaluation tools. It also forms experienced and specialized internal evaluation teams comprising various hospital managers and administrators. Another strength is the simultaneous conduct of internal and external evaluations. Additionally, the study establishes an external evaluation team of experts familiar with HPSs and gathers opinions and views from hospital stakeholders related to health promotion.

The limitations of the present study include conducting the research exclusively in educational hospitals and not comparing the results with non-educational hospitals in North Khorasan province. The study’s cross-sectional design also limits the potential for a comprehensive understanding of the evolution of HPS in hospitals over time.

Internal evaluations scored higher than external evaluations, highlighting the need to prioritize staff well-being. Disparities between the hospitals in Bojnourd and Shirvan Cities suggest location-based differences in the implementation of standards. Future research and interventions should focus on addressing these disparities and enhancing health promotion procedures in these hospitals.

Conclusion

NKUMS-affiliated hospitals are making progress in implementing HPSs, but improvements are needed, especially in staff health promotion.

Acknowledgments: All authors would like to thank the staff of the educational hospitals at North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnourd, Iran, for their assistance in conducting this research project.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnourd, Iran (Ethics approval code: IR.NKUMS.REC.1402.010).

Conflicts of Interests: All authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Namdar Ahmadabad H (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Rajabzadeh R (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Hosseini SH (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (35%); Jafarimoghadam A (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (Grant no. 4010252).

In accordance with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition, health is delineated as “not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, but a state of comprehensive physical, social, and mental well-being.” Consequently, endeavors aimed at enhancing these facets of health, including education, disease prevention, and rehabilitation, are considered health promotion initiatives. Multiple environments, such as schools, workplaces, residential areas, and hospitals, have the potential to contribute significantly to the promotion of health [1].

Hospitals account for over 40% of healthcare costs and are often criticized for focusing solely on diagnostic and therapeutic activities [2]. The WHO proposes health-promoting hospitals (HPHs) as an effective strategy for reforming health services [3]. The WHO launched the HPHs project in 1988 with the goal of reducing costs, improving patient and staff satisfaction, and implementing effective preventive programs [4]. The WHO delineates HPHs as institutions that offer superior medical and nursing services while cultivating an organizational identity that aligns with health promotion objectives. These establishments actively develop a health-promoting organizational structure and culture, which incorporates proactive and cooperative roles for patients and all employees. In addition, HPHs transform themselves into environments that foster well-being and health, ultimately encouraging collaborative relationships with the surrounding community [5]. HPHs aim to address the physical, mental, and social needs of patients, staff, organizations, and society, focusing on management policy, patient assessment and intervention, promoting a healthier work environment, and ensuring continuity and cooperation [6].

HPHs focus on the needs of patients and their companions, serving as the foundation for fostering a healthy lifestyle for both patients and society. These institutions encourage staff to adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle and strive to enhance overall health by mitigating environmental risks. Furthermore, they promote staff well-being [5, 7].

The international network of HPHs has experienced consistent growth, with over 900 hospitals and health service centers in more than 40 countries participating [8]. Most of these are located in developed countries, but health promotion programs in developing countries are gaining attention, albeit at a slower pace [2].

The first studies examining the condition of Iranian hospitals in terms of health promotion standards (HPSs), as set by the WHO, were conducted in 2013 [9]. Since then, studies have been carried out in various city hospitals in this field. Hamidi et al. reviewed studies pertaining to the state of Iranian hospitals with respect to the WHO’s HPS, announcing that there are several limitations. Firstly, the number of studies related to HPHs is limited, and more research is needed. Secondly, the findings of these studies demonstrate that Iranian hospitals need to achieve optimal conditions regarding HPS [10].

In previous studies, HPSs in Iranian hospitals have been evaluated either internally by hospital staff or externally by a group of researchers. Additionally, all these studies have utilized the WHO’s self-assessment tool to evaluate the state of HPS in hospitals [10].

Yaghoubi and Javadi emphasize that the effective implementation of hospital health promotion programs across different societies is influenced by the culture, values, and beliefs of those societies [9]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider adapting the evaluation tool for health promotion hospitals to local contexts. Believing that the self-assessment tool for improving hospital health should be appropriate to the cultural, social, political, economic, and health contexts of Iran, previous studies have localized the WHO’s self-assessment tool for health promotion to make it more practical and collaborative [11-13].

The term “HPHs” is relatively new in Iran, and there have been limited studies on this topic. Previous research has been conducted in a single center or specific clinical departments, using non-native evaluation tools and without simultaneous internal and external evaluations. These limitations have been identified in earlier studies. Thus, the present study aimed to determine the state of HPSs in educational hospitals affiliated with North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (NKUMS) using both internal and external evaluation methods.

Instrument and Methods

Subjects

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was conducted at educational hospitals affiliated with NKUMS in 2023. A census sampling method was utilized to select the educational hospitals. The criteria for participation in the study included the satisfaction of hospital officials and the willingness of the hospital accreditation team. All educational hospitals affiliated with NKUMS were included in this study. The educational hospitals of NKUMS, which include Imam Reza, Imam Hassan, Imam Ali, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals in Bojnourd city, as well as Khatam and Imam Khomeini hospitals in Shirvan city, were considered the research community.

Data collection tool

In this study, the WHO self-assessment tool for health promotion in hospitals was employed. This tool had previously been translated, localized, and validated in the Persian language in Iran [11, 13]. The tool included four standards and 67 substandards, with an average content validity index of 0.867 for the entire tool. The internal reliability of the tool was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha index, with results ranging from 78.1% to 95.5% for the four standards and a Cronbach’s alpha of 90.02% for the entire tool. The intragroup correlation coefficient value was 0.87, indicating acceptable stability of the tool (Table 1).

We utilized a five-point grading system to assess the degree of fulfillment for each substandard associated with HPSs. The grading system includes grade A (fully achieved substandard with a score of 9-10), grade B (substandard with high progress with a score of 7-8), grade C (substandard with moderate progress with a score of 5-6), grade D (substandard with low progress with a score of 3-4), and grade E (substandard with intention to start with a score of 1-2). In this tool, the evaluators scored the status of each substandard through observations, documents, and interviews.

Table 1. Standards for evaluating health promotion hospitals

The process of evaluating health promotion standards

An internal evaluation team was established in each hospital to assess the HPSs in educational hospitals. Hospital staff members who participated in the hospital’s accreditation and quality improvement programs and possessed adequate knowledge about the hospital’s activities related to HPSs, as well as documentation of these activities, were selected for the internal evaluation team of each hospital. The team consisted of the hospital manager, accreditation officer, quality improvement officer, educational supervisor, environmental health officer, social worker, patient education officer, and health promotion unit officer.

During a meeting with each hospital’s internal evaluation team, the evaluation objectives, HPS, evaluation tool, and methodology for scoring each substandard related to the hospitals’ HPS were explained. The members of the internal evaluation team completed the evaluation forms based on observations, documents, and interviews.

For the external evaluation of HPS, the research team, which included health education and health promotion specialists, as well as the manager of the accreditation unit of the Vice-Chancellor of Treatment Affairs of NKUMS, visited the hospital. In collaboration with the hospital’s head manager, they interviewed hospital staff, patients, and family members, performed observations, and reviewed existing documents to complete the evaluation forms.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 9 software was utilized to conduct the statistical analysis in this study. A significance level of less than 0.05 was considered for all tests performed. Descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequency, mean, and standard deviation, were employed to address the research objectives. The total score of each hospital and the score of each standard were presented as mean±standard deviation. To compare the results across different groups, descriptive statistical methods were used to extract and analyze the data. Mean and standard deviation were used for analyzing quantitative data, while frequency and percentage were employed for qualitative data. The normality of the distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Additionally, the independent sample t-test was performed to compare the average scores of each standard among different types of hospitals, locations, and numbers of hospital beds.

Findings

Analysis and comparison of internal and external evaluation scores for health promotion standards

The internal evaluations revealed that educational hospitals have made significant progress in promoting health standards, with a total average score of 7.05±2.25. This score indicates a strong emphasis on health promotion and demonstrates high progress. Three hospitals—Imam Ali, Imam Hassan, and Bent Al-Huda—achieved the highest scores in the internal evaluation (Figure 1). When comparing the different standards, the highest score was related to the standard for health promotion of patients and families (8.05±1.69), while the lowest score was associated with the standard for health promotion of staff (6.37±2.31).

The total average score of the external evaluation was 5.44±2.04, indicating a 50% improvement in hospital HPSs. Notably, all hospitals evaluated for HPS were in the moderate stage of progress, except for Imam Khomeini Hospital, which was in the low stage of progress (Figure 1). In alignment with the internal evaluation results, the highest average score in the external evaluation was related to the standard for health promotion of patients and families (6.86±1.41), while the lowest total average score was associated with the standard for health promotion of staff (7.00±1.83).

Figure 1. Comparison of average internal and external evaluation scores for health promotion standards in different educational hospitals

Our results showed that the average scores of internal evaluations were significantly higher than those of external evaluations in each of the educational hospitals (p<0.05). Furthermore, the comparison of each HPS indicated that the average score of the external evaluation for each standard was significantly higher than the average score of the internal evaluation (p<0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the average scores of internal and external evaluation of health promotion standards in hospitals

We compared HPS scores across different hospital characteristics. Our research revealed a significant difference in scores related to the hospitals’ locations (p<0.05). However, we did not find any significant variation in the number of active beds, the number of staff members, or the hospital’s age (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of average health promotion standards scores among hospitals with different characteristics. The results are presented as Mean ± SD; a p-value less than 0.05 is considered significant

Evaluation of the first standard: Management policy and program

In the internal evaluation of various hospitals, the highest number of substandards for the first standard was observed in the state of high progress, while the lowest number of substandards was in the state of intention to start (Figure 2A). According to the results of this internal evaluation, all the hospitals in Bojnourd City obtained a total average score higher than six for this standard. In contrast, two hospitals in Shirvan City obtained a total average score of less than six.

The external evaluation results showed that most of the substandards related to the first standard were in a state of moderate progress, while the lowest number of substandards was in a fully achieved state (Figure 2B). In this evaluation, the three hospitals—Imam Hassan, Imam Reza, and Bent Al-Huda—achieved an average score of more than five (moderate progress). In comparison, the three hospitals—Imam Ali, Khatam, and Imam Khomeini—achieved an average score of less than five (low progress).

Among the various substandards of the first standard, “a clear statement to promote the health of neighbors around the hospital in the management policy of the hospital,” “determining a sufficient budget for health promotion services,” and “cooperation of the hospital with other partners (organizations and institutions) to ensure and improve the health of patients, staff, and neighbors” received the lowest scores and were in the state of intention to start. In other words, no action was taken regarding these substandards in the evaluated educational hospitals, but evidence of their intention to act in this regard has been observed.

Evaluation of the second standard: Health promotion of patients and families

In the internal evaluation of health promotion for patients and families, most substandards were reported as fully achieved (Figure 2C). In all hospitals except Imam Reza, the total average score surpassed seven, indicating high progress in the second standard.

In the external evaluation, the majority of the substandards for the second standard were in a state of high progress (Figure 2D). The average total score for the second standard was over six in all hospitals.

Out of 19 substandards of the second standard, most hospitals showed low progress in four substandards. These substandards with low progress included “recording information about the factors influencing the health promotion of patients along with social and cultural factors in their files,” “recording a summary of the conditions and needs for health promotion of patients and the interventions performed in their files,” “recording health promotion activities and expected outcomes in patients’ files,” and “access of families and visitors to updated knowledge about health promotion.”

Figure 2. Status of the first and second standards based on the results of internal evaluation (A and C) and external evaluation (B and D) in educational hospitals

The third standard: Staff health promotion

In the internal evaluation of staff health promotion, most substandards showed moderate progress (Figure 3A). The average total score for Imam Hassan, Imam Reza, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals was above 7 (indicating a high progress state). In contrast, Imam Ali Hospital had an average total score of 6.69 (indicating a moderate progress state), while Khatam and Imam Khomeini hospitals had average total scores below five (indicating a low progress state).

The external evaluation results were consistent with the internal evaluation results, as most substandards of the third standard were also in the moderate progress state (Figure 3B). The average total score for Imam Hassan, Imam Reza, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals was above five, while the scores for Imam Ali, Khatam, and Imam Khomeini hospitals were below five.

Among the various substandards of the third standard, the evidence and documentation related to the substandards of “staff knowledge and awareness of health and safety promotion” and “planning of support and welfare services for hospital staff” were insufficient and in the state of intention to start.

The fourth standard: Promoting the health of the environment inside and around the hospital

The internal evaluation results for the fourth standard showed that the majority of substandards were fully achieved (Figure 3C). Imam Hassan, Imam Khomeini, and Imam Ali hospitals achieved an average total score above seven, while Khatam and Bent Al-Huda hospitals scored between five and seven.

The external evaluation results indicated that the majority of the fourth standard’s substandards were in a high progress stage (Figure 3D). Imam Ali, Imam Hassan, and Bent Al-Huda hospitals achieved an average total score of over six, whereas Imam Reza, Khatam, and Imam Khomeini hospitals scored an average of less than five.

Our results showed that in most hospitals, the indicator “interventions related to the prevention and control of risk factors for neighbors of the hospital” was in the state of intention to start.

Figure 3. Status of the third and fourth standards based on the results of internal evaluation (A and C) and external evaluation (B and D) in educational hospitals.

Discussion

In the present study, the state of HPS in educational hospitals affiliated with NKUMS was investigated using both external and internal evaluation methods. Various studies have evaluated the state of HPSs in hospitals across different cities in Iran. The majority of these evaluations have been internal assessments conducted by the hospital staff themselves. Limitations of internal evaluation methods, such as bias, limited perspective, and potential conflict of interest, have undoubtedly impacted the results of these studies [14].

The results of the internal evaluation indicated that hospitals could be classified into two groups based on the implementation and fulfillment of HPSs, including the high-progress group and the moderate-progress group. Hospitals in the high-progress group showed clear evidence of their commitment to these standards, with 50% of the evaluated hospitals falling into this category. Meanwhile, the moderate-progress group represented hospitals that have made around 50% progress in implementing the standards, comprising the remaining 50% of the evaluated hospitals. The results of the external evaluation revealed that all hospitals exhibited moderate progress in the implementation of HPS, with only one hospital demonstrating low progress. The evidence suggests that the implementation of HPS in this hospital could be more cohesive.

In the current study, the internal evaluation results revealed that 50% of the hospitals were in a state of high progress, while the remaining 50% were in a state of moderate progress. Afshari et al. conducted a study investigating the state of health promotion in hospitals in Isfahan, Iran, reporting 55% of hospitals being at an average level, and only 11% of the internally evaluated hospitals being in good condition [15]. Pezeshki et al. found that the health promotion scores in hospitals in East Azerbaijan are at an average level [16]. Other studies performed in Gilan, Shiraz, Tehran, Mashhad, and Hamedan provinces in Iran, using the internal evaluation method, have reported that the hospitals’ scores for HPSs are average [9, 17, 18], with unfavorable conditions being noted in some cases [19]. A systematic review by Hamidi et al. analyzed studies on HPHs in Iran and found that the hospitals investigated are significantly weak in HPS [10]. Comparing the results of our study with previous studies reveals that North Khorasan hospitals have better condition in implementing HPS. Several factors could contribute to this difference, such as the focus on educational hospitals in our study, the timing of the study during a period when the concept of HPHs is more well-known and important, and the use of a modified self-assessment tool instead of the WHO self-assessment tool for data collection. Supporting our interpretation, Rezaei and Karamali’s study using a modified self-assessment tool to evaluate HPS, found an average score of 5.47 [11], similar to our external evaluation results, where the scores of most hospitals were within the range of five.

The internal evaluation scores of hospitals’ HPSs were significantly higher than the external evaluation scores. Although the results of the internal evaluation indicated better implementation of HPS in hospitals compared to external evaluations, both evaluation methods were consistent in identifying which hospital or standard was in a more favorable condition. Previous research has shown that evaluating hospital and health promotion programs internally by staff members produces more positive results than external evaluations [20, 21]. Our current study also supports this conclusion.

Previous studies have indicated that hospitals located in capital cities are in a better state regarding HPS compared to those in counties [10, 16]. In agreement with this statement, our results also showed that hospitals located in Bojnourd City, the capital of North Khorasan province, scored higher than hospitals in Shirvan County. We did not observe any significant differences in the HPS scores between hospitals with respect to the other three characteristics, such as the age of the hospital, the number of faculty members, and the number of active beds.

Management policy, health professional competencies, and financial budget are crucial for the successful implementation of a hospital program [22]. The standard of management policy and program is considered a fundamental issue in the implementation of health promotion hospitals. In the majority of prior studies conducted in Iran, the standard of management policy and program has received lower scores compared to other standards [10, 17, 19, 23]. However, in our research, this standard did not achieve either the lowest or the highest average score when compared to other standards; instead, it was in a state of moderate progress. The total average score of the internal evaluation for the standard of policy and management was 6.79 out of a possible ten, while the total average score of the external evaluation was 4.84 out of a possible ten. Continuous management support, transformative leadership, participatory strategic management, and expert governance can help hospitals focus on health promotion [24].

In the present study, the highest score was related to the standard of health promotion for patients and families. Pezeshki et al. [16] and studies conducted by Yaghoubi & Javadi and Taghdisi et al. report similar results [9, 23].

When comparing different standards, it was evident that the staff HPS received the lowest scores in both internal (4.7 out of ten) and external (6.37 out of ten) evaluations. This underscores a critical issue; while the investigated hospitals were effective in addressing patient and family health, their efforts in staff health promotion were lacking. Our hospitals need a comprehensive plan to address this standard. Previous studies in Iran have consistently highlighted the low scores for staff HPSs in hospitals [16, 18, 25]. This is concerning because hospital staff members play a crucial role in patient care, and their health directly impacts their performance, which in turn affects patient health. Therefore, it is imperative to support the creation of a safe and healthy work environment.

To create a healthy hospital environment, it is recommended to focus on trust, transparency, effective leadership, suitable employees, commitment to safety and ethical care, decision-making authority, professional knowledge, teamwork, active listening, open communication, skillful and healthy communication, and obtaining the required information [26, 27]. Sadeqi-Arani et al. suggest developing appropriate training programs for staff health promotion and encouraging staff participation in hospital policies to improve the standard of staff health promotion in HPHs [25].

Our review identified that the substandards “planning support and welfare services for hospital staff” and “staff knowledge and awareness about health and safety promotion” received the lowest scores. Previous studies in Iran emphasized healthcare workers’ dissatisfaction with support and welfare services due to a lack of attention to their actual needs, the absence of a comprehensive system, and the failure to consider staff characteristics and opinions [28, 29].

The study has several strengths, including the use of localized and valid evaluation tools. It also forms experienced and specialized internal evaluation teams comprising various hospital managers and administrators. Another strength is the simultaneous conduct of internal and external evaluations. Additionally, the study establishes an external evaluation team of experts familiar with HPSs and gathers opinions and views from hospital stakeholders related to health promotion.

The limitations of the present study include conducting the research exclusively in educational hospitals and not comparing the results with non-educational hospitals in North Khorasan province. The study’s cross-sectional design also limits the potential for a comprehensive understanding of the evolution of HPS in hospitals over time.

Internal evaluations scored higher than external evaluations, highlighting the need to prioritize staff well-being. Disparities between the hospitals in Bojnourd and Shirvan Cities suggest location-based differences in the implementation of standards. Future research and interventions should focus on addressing these disparities and enhancing health promotion procedures in these hospitals.

Conclusion

NKUMS-affiliated hospitals are making progress in implementing HPSs, but improvements are needed, especially in staff health promotion.

Acknowledgments: All authors would like to thank the staff of the educational hospitals at North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnourd, Iran, for their assistance in conducting this research project.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnourd, Iran (Ethics approval code: IR.NKUMS.REC.1402.010).

Conflicts of Interests: All authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Namdar Ahmadabad H (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Rajabzadeh R (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Hosseini SH (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (35%); Jafarimoghadam A (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%)

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (Grant no. 4010252).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Setting

Received: 2024/09/2 | Accepted: 2024/11/7 | Published: 2024/11/10

Received: 2024/09/2 | Accepted: 2024/11/7 | Published: 2024/11/10

References

1. Schramme T. Health as complete well-being: The WHO definition and beyond. Public Health Ethics. 2023;16(3):1-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/phe/phad017]

2. Kar SS, Roy G, Lakshminarayanan S. Health promoting hospital: A noble concept. Natl J Community Med. 2012;3(3):558-62. [Link]

3. Whitelaw S, Baxendale A, Bryce C, Machardy L, Young I, Witney E. 'Settings' based health promotion: A review. Health promot Int. 2001;16(4):339-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/16.4.339]

4. Lee CB, Chen MS, Powell MJ, Chu CMY. Organisational change to health promoting hospitals: A review of the literature. Springer Sci Rev. 2013;1(1-2):13-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40362-013-0006-7]

5. Kumar S, Preetha G. Health promotion: An effective tool for global health. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37(1):5-12. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0970-0218.94009]

6. Whitehead D. The European health promoting hospitals (HPH) project: How far on?. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(2):259-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/dah213]

7. Lin YW, Lin YY. Health-promoting organization and organizational effectiveness of health promotion in hospitals: A national cross-sectional survey in Taiwan. Health Promot Int. 2011;26(3):362-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daq068]

8. Pelikan JM, Metzler B, Nowak P. Health-promoting hospitals. In: Handbook of settings-based health promotion. Cham: Springer; 2022. p. 119-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-95856-5_7]

9. Yaghoubi M, Javadi M. Health promoting hospitals in Iran: How it is. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2(1):41. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.115840]

10. Hamidi Y, Hazavehei SMM, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Rabiei MAS, Farhadian M, Alimohamadi S, et al. Health promoting hospitals in Iran: A review of the current status, challenges, and future prospects. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019;33:47. [Link] [DOI:10.47176/mjiri.33.47]

11. Rezaei Z, Karamali M. Evaluation of health promotion standards in a military hospital in Iran. J Mil Health Promot. 2021;3(1):521-9. [Link]

12. Nikpajouh A. Standards of health promoting hospitals: 68 or 40 measurable elements?. Health promot Perspect. 2017;7(3):109-10. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2017.20]

13. Mansouri Z, Vahdat S, Masoudi AI, Hessam S, Mahfoozpour S. Evaluation components of health promoting hospitals: An integrated review study. Iran J Nurs Res. 2020;15(2):9-23. [Persian] [Link]

14. Conley-Tyler M. A fundamental choice: Internal or external evaluation?. Eval J Australas. 2005;4(1-2):3-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1035719X05004001-202]

15. Afshari A, Mostafavi F, Keshvari M, Ahmadi-Ghahnaviye L, Piruzi M, Moazam E, et al. Health promoting hospitals: A study on educational hospitals of Isfahan, Iran. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;6(1):23-30. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2016.04]

16. Pezeshki MZ, Alizadeh M, Nikpajouh A, Ebadi A, Nohi S, Soleimanpour M. Evaluation of the health promotion standards in governmental and non-governmental hospitals in East-Azerbaijan. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019;33:113. [Link] [DOI:10.47176/mjiri.33.113]

17. Yousefi S, Vafaeenajar A, Esmaily H, Hooshmand E. Evaluation of general educational hospitals affiliated to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences based on the standards of health-promoting hospitals. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2018;5(4):320-7. [Persian] [Link]

18. Hamidi Y, Hazavehei SMM, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, SeifRabiei MA, Farhadian M, Alimohamadi S, et al. Investigation of health promotion status in specialized hospitals associated with Hamadan University of Medical Sciences: Health-promoting hospitals. Hosp Pract. 2017;45(5):215-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/21548331.2017.1400368]

19. Charoghchian Khorasani E, Moghzi M, Badiee S, Peyman N. Investigation of health promotion status in one of the specialized hospitals affiliated to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences based on the indicators of health-promoting hospitals of the World Health Organization. NAVID NO. 2020;23(75):72-82. [Persian] [Link]

20. Araújo RG, Fonseca VdM, De Oliveira MIC, Ramos EG. External evaluation and self-monitoring of the baby-friendly hospital initiative's maternity hospitals in Brazil. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14:1. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13006-018-0195-4]

21. Karami S, Lichaee HT, Ghaen MM, Azam K, Pourreza A. Comparison of internal and external evaluation of the workplace health promotion programs in volunteer organizations of Tehran. Iran Occup Health. 2022;19(1):70-84. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/ioh.19.1.70]

22. Bempah BSO. Policy implementation: Budgeting and financial management practices of district health directorates in ghana [dissertation]. Bangkok: National Institute of Development Administration; 2012. [Link]

23. Taghdisi MH, Poortaghi S, Suri-J V, Dehdari T, Gojazadeh M, Kheiri M. Self-assessment of health promoting hospital's activities in the largest heart hospital of Northwest Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:572. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-018-3378-1]

24. Röthlin F. Managerial strategies to reorient hospitals towards health promotion: Lessons from organisational theory. J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27(6):747-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/JHOM-07-2011-0070]

25. Sadeqi-Arani A, Montazeralfaraj R, Sadeqi-Arani Z, Bahrami M, Rahati M, Askari R. Strategies for improving the standards of health promoting hospitals: A case study in the selected hospitals in Iran. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;10(4):791-7. [Link]

26. Sönmez B, Yıldız Keskin A, İspir Demir Ö, Emiralioğlu R, Güngör S. Decent work in nursing: Relationship between nursing work environment, job satisfaction, and physical and mental health. Int Nurs Rev. 2023;70(1):78-88. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/inr.12771]

27. Mabona JF, Van Rooyen DR, Ten Ham-Baloyi W. Best practice recommendations for healthy work environments for nurses: An integrative literature review. Health SA. 2022;27(1):1788. [Link] [DOI:10.4102/hsag.v27i0.1788]

28. Dehghan R, Mafimoradi S, Hadi M. Need assessment of staffs' welfare services at Tehran University of Medical Sciences: A cross-sectional study. J Educ Health Promot. 2015;4(1):7. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.151888]

29. Bagheri S, Kousha A, Janati A, Asghari-Jafarabadi M. Factors influencing the job satisfaction of health system employees in Tabriz, Iran. Health Promot Perspect. 2012;2(2):190-6. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |