Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 553-560 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kakavand R, Khayatan F, Golparvar M. Effect of Vaginismus-Specific Schema Therapy and Conventional Schema Therapy on Sexual Self-Assertiveness & Self-Esteem in Women with Vaginismus Disorder. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :553-560

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76306-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76306-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

Keywords: Schema Therapy [MeSH], Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological [MeSH], Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological [MeSH], Vaginismus [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 717 kb]

(1965 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1121 Views)

Full-Text: (108 Views)

Introduction

Sexual health and positive marital relationships have well-documented effects on physical, mental, and social well-being [1]. Consequently, any disorder in this area can impact sexual health [2]. Among these disorders, pelvic-genital penetration pain disorder (vaginismus) is defined as a persistent issue characterized by pain, fear, or muscle stiffness in anticipation of, during, or after attempts at vaginal penetration, lasting for at least six months [3]. The prevalence of vaginismus has been reported to range from 5% to 42% [4]. In selected Iranian studies, the incidence of vaginismus in the general female population has been reported as between 0.4% and 8% [5].

Physical factors affecting vaginismus include urinary tract infections, cysts, eczema, pelvic inflammation, complications from childbirth, such as pain due to vaginal delivery or difficult delivery, abortion, age-related changes, such as menopause and hormonal fluctuations, vaginal dryness, pelvic lesions, and the side effects of medications [6].

Factors, such as pregnancy phobia, painful intercourse, recurrent medical issues with pelvic muscles, generalized anxiety, performance anxiety (concern about not performing well during sex), previous negative sexual experiences, negative beliefs about sex, feelings of guilt, emotional trauma, and other unhealthy sexual emotions, relationship problems with a spouse, including abuse, lack of emotional connection, fear of commitment, lack of confidence and trust, and a sense of loss of control, as well as repressed memories of childhood experiences, such as strict parenting, unbalanced religious restrictions, exposure to shocking sexual scenes and images, and inadequate sexual education, are among the psychological factors that can affect vaginismus disorder [7, 8]. In patients with vaginismus disorder, these fears create distress in many important areas of life [9]. Self-assertive individuals express their feelings and desires openly, without shame [10]. According to behaviorism theory, women with vaginismus learn a lack of sexual self-assertiveness through reinforcement or punishment, such as a lack of verbal openness regarding sexual issues, within the cultural and educational context of their families [11]. These studies indicate that women who are unwilling to express their sexual desires to their husbands have a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction disorders, including vaginismus [12, 13].

One of the factors that influence sexual performance is defined as a person’s positive attitude and perception of their sexual status, based on which they adjust their behavior. This aspect of interpersonal functioning also plays a role in the development of a healthy sex life; it is fluid and changes under the influence of various conditions [14]. Research has shown that there is a reciprocal relationship between women’s sexual self-esteem and their sexual performance, with women experiencing sexual disorders being more likely to suffer from low sexual self-esteem. Women who have sexual dysfunction and feelings of sexual incompetence tend to have low sexual self-esteem and may withdraw from sexual activity [15].

Previous studies have demonstrated that symptoms of vaginismus disorder are reduced through conventional schema therapy (ST) [16, 17]. ST focuses on the foundations of behavior and the deepest cognitive structures of individuals. Primary maladaptive schemas are dysfunctional emotional and cognitive patterns that are formed in childhood and are repeated throughout life [4].

Vaginismus-specific schema therapy (VSST) for vaginismus disorder examines various sexual beliefs and attitudes that contribute to women’s sexual dysfunction in relation to sexual schemas and marital compatibility [18]. The presence of negative beliefs and thoughts, such as criticism and a negative self-image, can adversely affect women’s pleasure and desired sexual function, leading to negative emotions such as anger, fear, shame, and guilt. Therefore, ST can improve vaginismus disorder and the associated problems by addressing unhealthy mental patterns [19]. A review of the research findings indicates that ST can enhance functioning by focusing on women’s issues, particularly their relationships with their spouses [20]. Correcting and adjusting initially incompatible schemas and strengthening a healthy adult mentality have resulted in improvements and increases in sexual self-esteem. VSST emphasizes eliciting emotions related to primary incompatible schemas, which helps identify behaviors and attitudes that threaten personal value and self-esteem. Reparenting for women suffering from vaginismus disorder was conducted to enhance their emotions and address the relative satisfaction of unmet needs, thereby increasing their self-esteem. This reparenting process focused on the primary unfulfilled needs of women with vaginismus disorder by providing emotional support and addressing effective factors in modulating schemas, ultimately strengthening the adult mentality and fostering a sense of worth [19, 21].

Therefore, research on the effectiveness of ST in improving self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem in women with vaginismus is of particular importance, as vaginismus not only negatively impacts the sexual quality of life for women but can also lead to emotional problems and issues within marital relationships. Considering that many women avoid seeking help from healthcare professionals due to feelings of shame and embarrassment, providing effective and indirect solutions like ST can help increase access to and acceptance of treatment. Additionally, this research can identify and enhance self-assertion skills and sexual self-esteem in women, enabling them to approach their relationships with a stronger sense of self. ST assists women in strengthening their self-assertion abilities, allowing them to express their sexual needs and desires more easily while identifying and changing negative schemas can further enhance individual self-esteem.

Despite ST being recognized as an effective approach for treating psychological disorders, there are limited studies on its impact on women with vaginismus, particularly concerning their self-assertion and sexual self-esteem. Most existing research has primarily focused on the physiological and medical aspects of vaginismus, while the emotional and psychological dimensions of this disorder have received less attention. Additionally, the cultural and social influences on the experience of vaginismus and treatment methods have also been less studied. This topic can contribute to a better understanding of the challenges women face when dealing with this disorder. Furthermore, most existing research concentrates on a specific type of treatment, while examining the effects of combined methods (such as integrating ST with other treatments) may yield better outcomes. Ultimately, the results of this research could significantly contribute to the development of innovative therapeutic methods and improve the sexual quality of life in society. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of an ST package specifically designed for women with vaginismus, as well as conventional ST methods, on the self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem of women with vaginismus disorder.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental research employed a pre-test, post-test, and follow-up design, including a control group, and was conducted on women (aged 20 to 50 years) with vaginismus who were referred to the obstetrics and gynecology clinic of Payambaran Hospital in Tehran in 2021. This research began from the fall of 2021 to the spring of 2022 and the follow-up was conducted 45 days after the intervention.

A total of 45 women were selected as a sample using a targeted approach. The sample size was calculated to include 20 individuals in each group based on similar studies [18], taking into account an effect size of 0.40, a confidence level of 0.95, a test power of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10%. Consequently, 60 cases were chosen as samples using the purposive sampling method according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The three groups were then randomly assigned using a simple lottery method, including one group receiving specialized ST for women with vaginismus, a conventional ST group, and a control group.

The inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of vaginismus by a gynecologist, not receiving concurrent medical and psychological treatments, having at least a high school diploma, and a minimum of one year of cohabitation. The exclusion criteria included a lack of cooperation from participants in completing homework assignments and absence from more than two treatment sessions. In addition to obtaining an ethics code, the study adhered to ethical principles, such as confidentiality, using data solely for research purposes, ensuring participants had the freedom and autonomy to continue their involvement in the study, and providing detailed information to participants if they requested the results, along with training for the control group after the completion of the intervention. Three groups were observed in the study.

The tools used included Halbert’s Sexual Self-Assertion Questionnaires (1992) and Zeanah and Schwarz’s Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women (SSEI-W, 1996). Additionally, the Persian version of these tools was utilized.

Halbert's Sexual Self-Assertiveness Questionnaire: The Persian version of Halbert’s Sexual Self-Assertiveness Index was utilized, which includes 25 items on a Likert scale. The response options range from “always”=0 to “never”=4. Items 3, 4, 5, 7, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, and 23 are scored in reverse. The range of test scores is from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater sexual self-assertiveness. The validity of this test was established by David Farley, with a coefficient of 0.86. In a study involving 60 married women, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.84 [22].

Women's Sexual Self-Esteem Questionnaire by Zeanah and Schwarz (SSEI-W): This questionnaire consists of 35 items and was developed to measure women’s effective responses regarding their sexual self-evaluation. The questions are answered on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” This questionnaire includes five subscales that reflect various aspects of sexual self-esteem, including experience and skill, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and conformity. By summing the scores from these five areas, a total score for the scale is obtained, with a higher score indicating greater sexual self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire scale is 0.92, with individual coefficients of 0.84 for attractiveness, 0.88 for control, 0.80 for moral judgment, and 0.80 for conformity. In the research conducted by Zeanah and Schwarz [23], the convergent validity was confirmed through correlation with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (r=0.57). In the study by Farokhi and Share involving a sample of 510 Iranian married women, the same five factors from the original version were identified through factor analysis of the questionnaire. The internal consistency coefficient for the items across the entire sample was 0.88, and the correlation coefficients between each item and the total score of the scale ranged from 0.54 to 0.72. The test-retest reliability coefficient for the entire scale was reported as 0.91, with coefficients for its five subscales ranging from 0.82 to 0.94 [24]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was determined using Cronbach’s alpha method, resulting in a coefficient of 0.91.

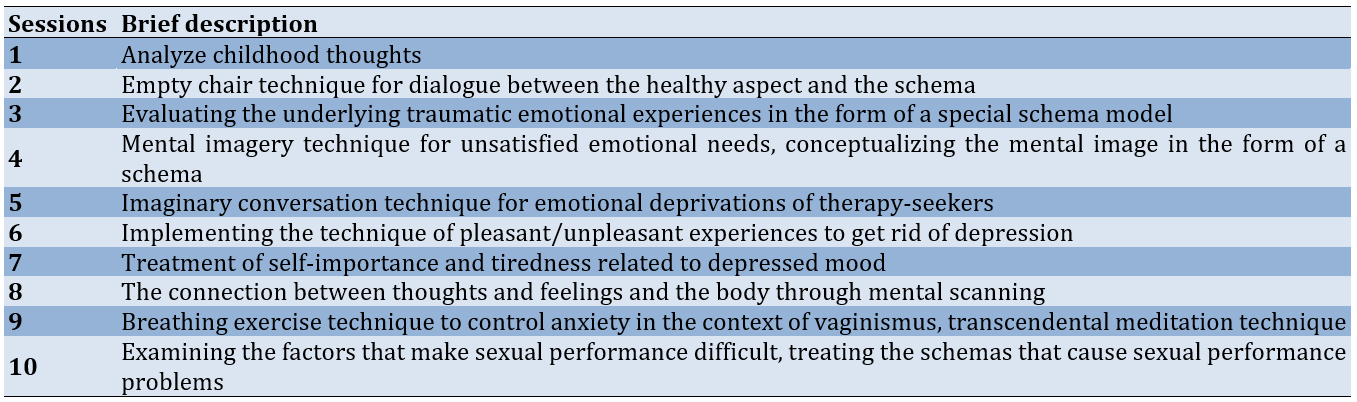

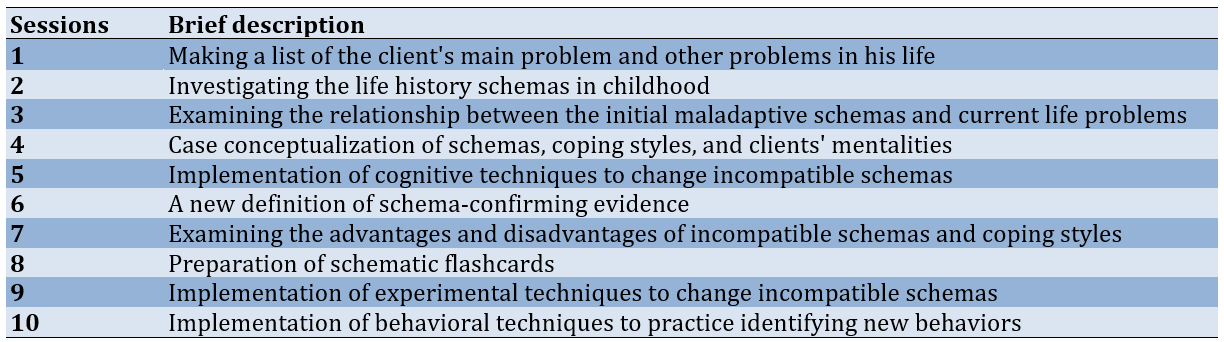

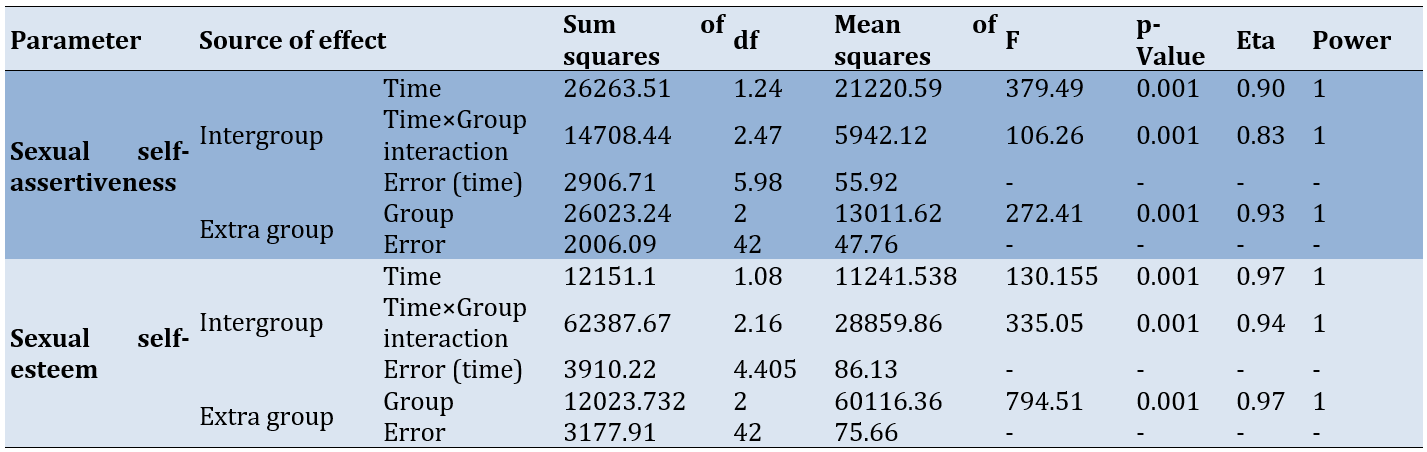

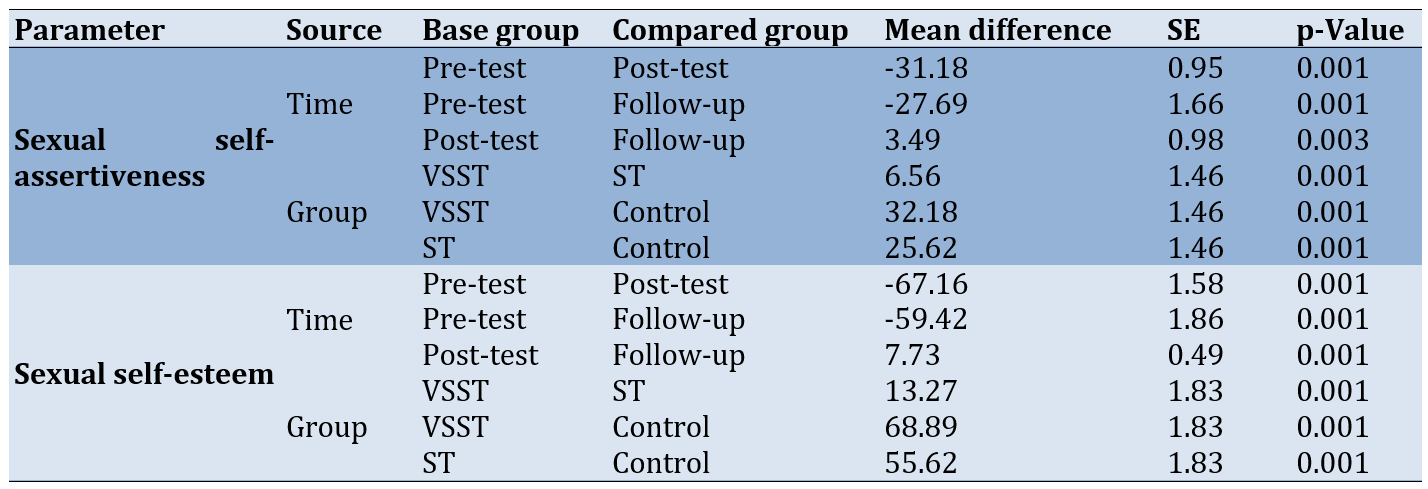

At first, women with vaginismus disorder completed the questionnaires during the pre-test phase. The data collection process involved randomly assigning the participants to three groups, including two treatment groups and one control group. Each of the treatment groups received simultaneous group therapy sessions at the women’s clinic. After the final intervention session, women from all three groups completed the questionnaires again during the post-test and follow-up stages. The VSST for women with vaginismus and conventional ST were each conducted over ten sessions of 90 minutes, with two sessions per week, totaling five consecutive weeks. The interventions were facilitated by an experienced ST therapist with several years of treatment experience. The control group did not receive any treatment until after the training of the two treatment groups was completed. The VSST for women suffering from vaginismus has been utilized for the first time in this study, following initial content, scientific, and professional validation. The process of compiling the VSST began with in-depth interviews and content analysis of relevant texts in this field. Using the Attride-Stirling thematic network analysis [25], the necessary organizing and foundational topics for ST for women with vaginismus were identified. At this stage, the content validity ratio (CVR), calculated by three independent coders, was equal to one. Subsequently, therapeutic techniques for each subject were extracted through conventional content analysis. An expert panel consisting of six psychologists with more than ten years of treatment experience then developed a combination of therapeutic techniques aimed at improving women’s mental health over ten sessions. The order of the treatment package was established, and the compiled package was reviewed by six expert judges in the field of health psychology. After incorporating the judges’ corrections, an overall agreement coefficient of 0.9 was obtained for the treatment package. Following expert approval, a pilot study was conducted to assess the preliminary effectiveness of the designed package on six women suffering from vaginismus disorder, confirming the initial validity of the package. The ST group was treated using a validated treatment package, Young et al.'s ST package in Iran [17] (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Description of vaginismus-specific schema therapy (VSST) [19]

Table 2. Description of schema therapy [17]

In the statistical analysis of the data, descriptive statistics, such as the mean and standard deviation were calculated. At the inferential level, the normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, the equality of error variances was evaluated through Levene’s test, and the equality of the variance-covariance matrix was determined using the M-box test. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. The data were analyzed using SPSS 22. The acceptable level of significance was set at a minimum of 0.05 and a maximum of 0.001.

Findings

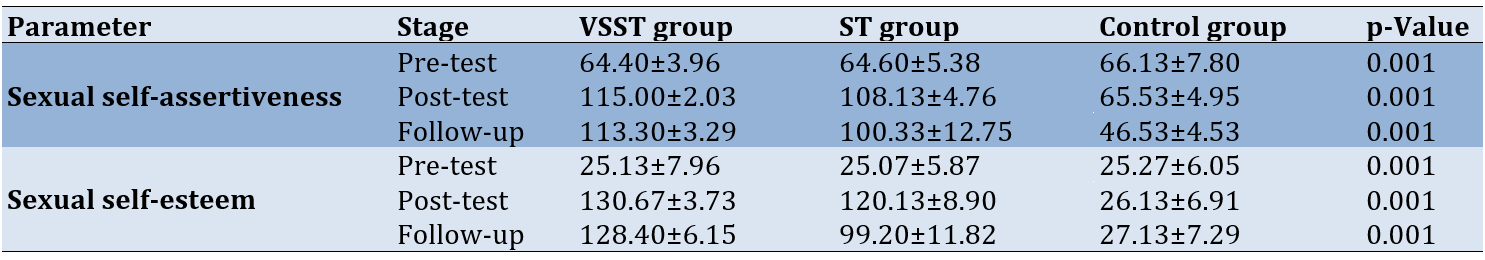

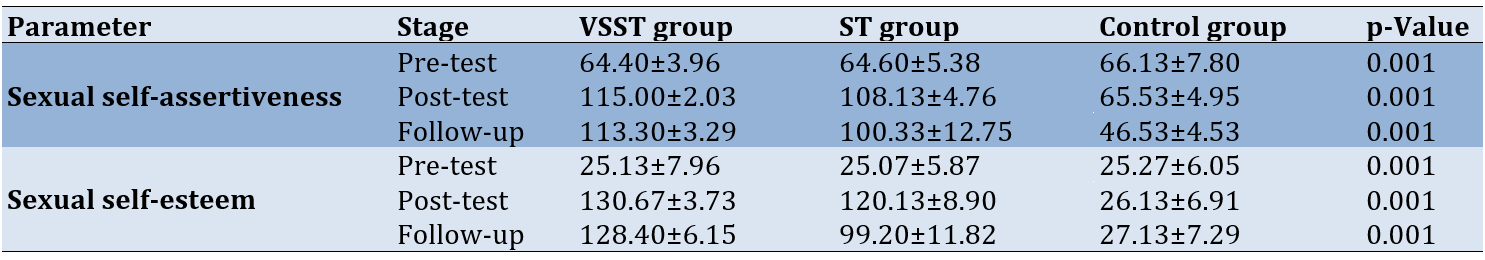

The three research groups were compared in terms of age, education status, and occupation using a Chi-square test and there were no significant differences in the aforementioned demographic characteristics among the three groups. The mean results for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem in women showed that the two treatment groups exhibited greater changes than the control group in the post-test and follow-up (45 days after the end of the intervention; Table 3).

Table 3. Mean self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem in the vaginismus-specific schema therapy (VSST), schema therapy (ST), and control groups at three time points

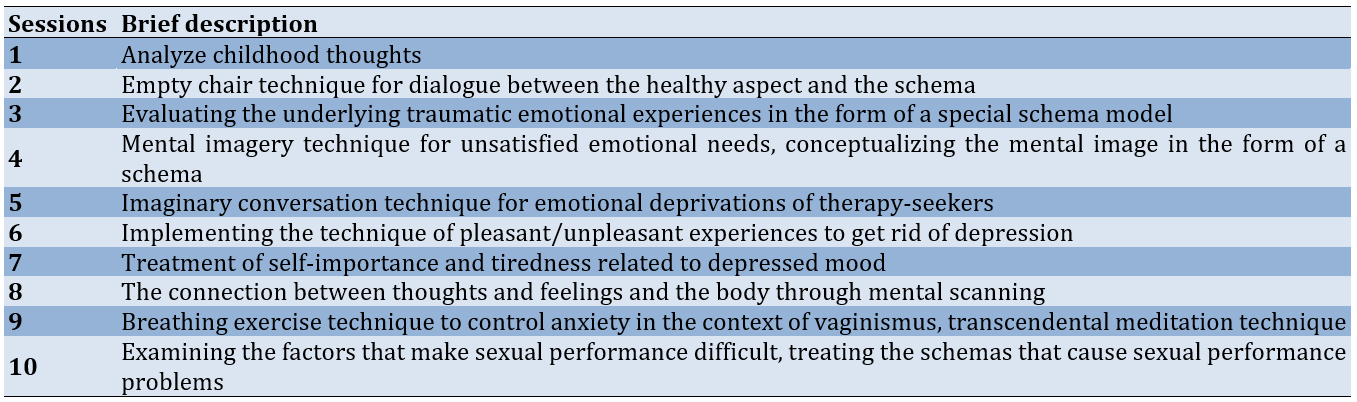

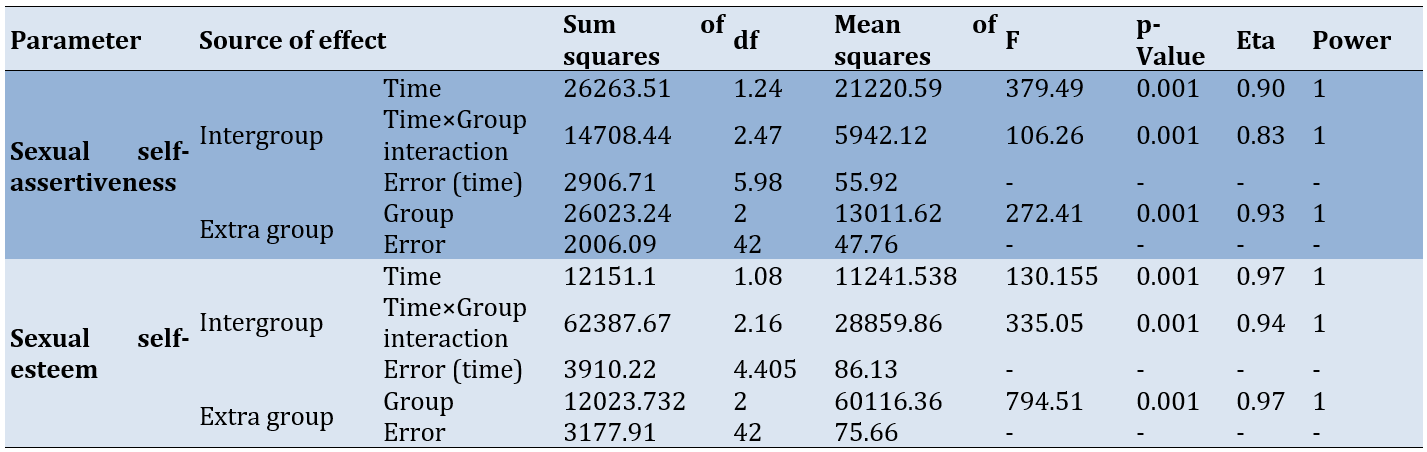

Before repeated-measures ANOVA, the statistical assumptions for this analysis were examined. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem indicated that the distribution of these two parameters was significant (p=0.001). Additionally, the results of Levene’s test showed that the variances among the study groups for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem were equal (p=0.001). The M-box test for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem indicated the equality of the variance-covariance matrix, and the interaction of group membership with the pre-test also demonstrated the equality of the slopes of the regression lines (p=0.001). Therefore, the repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that, in terms of the intra-group effect, both the time factor and its interaction with group membership indicated significant differences for both self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem over time and in relation to the three research groups (p=0.001). Thus, 90% and 97% of the variance in sexual self-assertiveness, and 83% and 94% of the variance in sexual self-esteem, were attributable to the independent parameters (one of the two treatments in the study), both confirmed with 100% power. Furthermore, the intergroup effect indicated a significant difference (p=0.001) in both sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem based on the group factor. The parametric eta squared for the group factor was equal to 0.93 and 0.97, respectively, and the power of the test was equal to 1. This indicated that the variance analysis conducted with 100% power revealed a significant difference of 93% and 97% between at least one of the experimental groups (VSST & ST) and the control group in terms of sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem (Table 4).

Table 4. Results of the repeated-measures ANOVA for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem

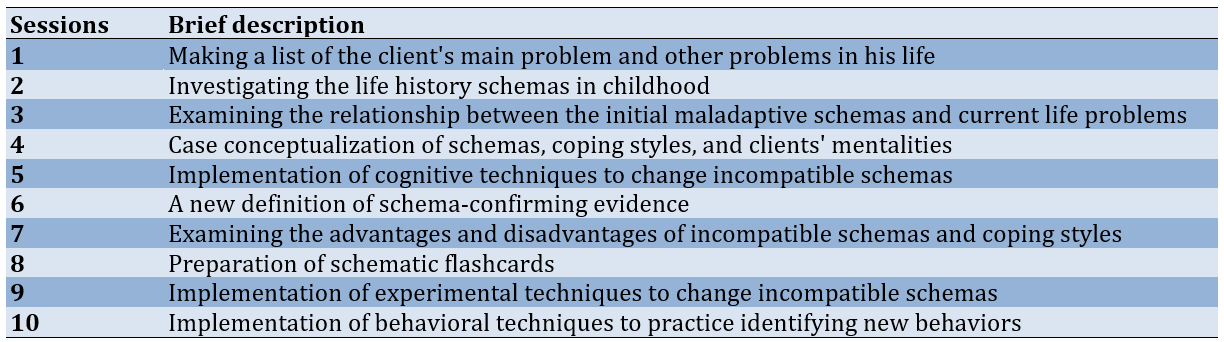

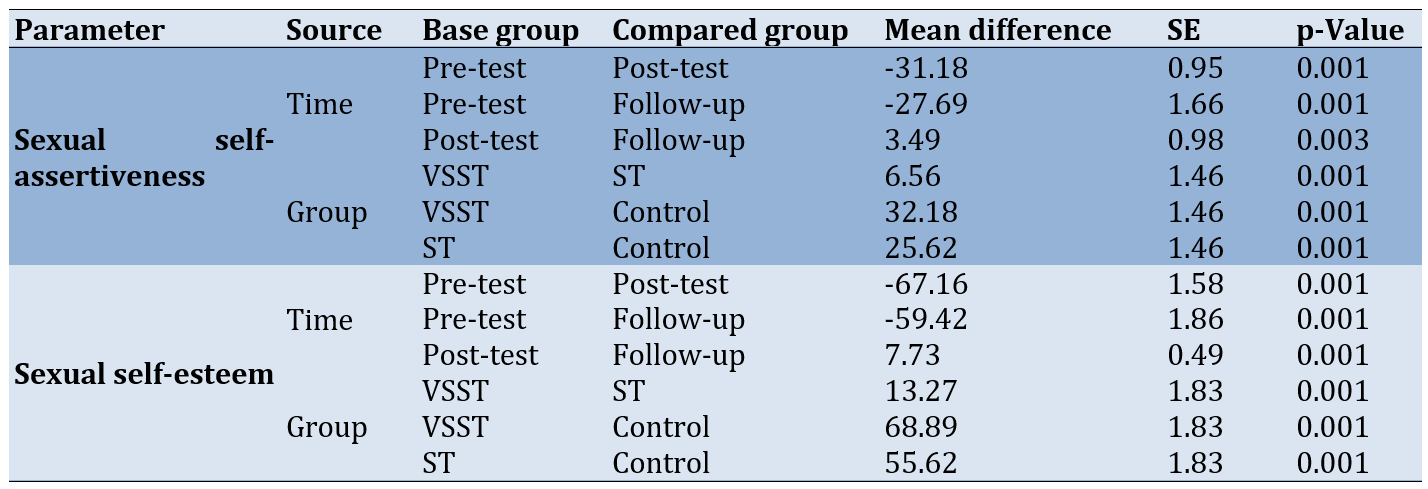

To determine the pairwise differences between the three research groups, Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed, which indicated significant differences in sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem between the pre-test and post-test, as well as between the post-test and follow-up. Additionally, significant differences were found between the two treatment groups and the control group (p=0.001), and between the VSST and ST groups (p=0.001). Therefore, the effectiveness of the VSST and conventional ST differed in terms of sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem in women with vaginismus. Specifically, there were significant differences between the pre-test and post-test, between the post-test and follow-up, and between the two treatment groups and the control group (Table 5).

Table 5. Results of the Bonferroni follow-up test comparing research groups for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem

Discussion

This study, which was conducted to compare the effectiveness of the VSST with conventional ST on the sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem of women with vaginismus disorder, demonstrated that both treatments significantly improved sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem. In other words, the comparison of the means of the two intervention groups with the control group indicated that the VSST had a greater effect on enhancing self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem than the ST.

Vaginismus, characterized by involuntary pelvic floor muscle contractions during attempted vaginal penetration, poses significant psychological and emotional challenges for affected women. This condition not only disrupts sexual intimacy but can also lead to diminished self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy. Therefore, effective therapeutic interventions are essential for restoring sexual health and enhancing overall well-being.

The findings of this study underscored the potential advantages of the VSST compared to conventional ST. While ST has long been recognized for its role in reducing anxiety and enhancing intimacy through gradual exposure, it often emphasizes partner involvement and may inadvertently reinforce feelings of pressure or inadequacy. In contrast, VSST empowers women to take control of their own sexual experiences in a safe and private setting. This autonomy can foster a sense of agency that is particularly beneficial for those grappling with vaginismus. When comparing the results of the present research with similar studies, it is important to note that, due to the novelty of the VSST, no research was found that completely aligns with this study in terms of the subject matter. However, considering the general orientation of the interventions, it can be stated that the results obtained from this study regarding the effectiveness of conventional ST in increasing women’s sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem are consistent with previous studies that highlight the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and specialized health education for marital relationships. The beneficial effects on sexual self-assertiveness [13, 21] and the effectiveness of ST for vaginismus on other parameters related to marital relations, such as sexual schemas and marital adjustment [18], are also consistent with these findings. The results of another study regarding the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and sexual self-esteem in females indicated that couple therapy based on acceptance and commitment, as well as cognitive self-compassion, is significantly effective in improving sexual adjustment and self-esteem compared to the control group [26]. According to Beck’s schema theory (1996), when the incompetence schema is activated in a sexual situation, individuals are likely to actively seek schema-congruent cues, ignore conflicting stimuli, and exaggerate the negative interpretation of the event. For instance, thoughts, such as “I am incompetent,” “I am ineffective,” and “I am a failure” may arise [27].

The mechanisms, through which VSST enhances sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem warrant further exploration. Engaging in self-stimulation allows women to cultivate body awareness and comfort with their own anatomy, which is crucial for overcoming the fear and anxiety associated with penetration. By normalizing the experience of pleasure and reducing performance pressure, VSST may facilitate a more positive self-image and greater sexual confidence. This empowerment can translate into improved communication with partners, leading to healthier sexual relationships.

Our findings align with existing literature that emphasizes the importance of self-exploration in overcoming sexual dysfunction. Research has demonstrated that interventions promoting body positivity and sexual self-acceptance can significantly improve sexual functioning and emotional well-being. For instance, studies have shown that women who engage in self-exploration report higher levels of sexual satisfaction and self-esteem. By situating our results within this broader context, we reinforce the argument that VSST represents a viable alternative or complement to traditional therapeutic approaches.

The implications for clinical practice are profound. Therapists working with women experiencing vaginismus should consider integrating VSST into their treatment protocols. Not only does this technique provide a practical tool for overcoming physical barriers to penetration, but it also addresses the psychological components of sexual dysfunction. By promoting self-assertiveness, clinicians can help patients reclaim their sexual identities and foster healthier relationships.

In explaining this research finding, it can also be stated that the main goal of the VSST for the sexual self-esteem of women with vaginismus disorder is to address the schemas that contribute to weak sexual self-esteem, such as abandonment/instability, emotional deprivation, stubbornness/extreme fault-finding, mistrust/abuse, social isolation/alienation, failure, dependency/incompetence, and punishment. VSST, by bringing these schemas that undermine sexual self-esteem to the active conscious level and overcoming emotional distance, creates the context for a genuine sense of value associated with sexual self-esteem. The use of cognitive techniques was effective in improving the cognitive distortions of women with vaginismus, thereby enhancing their sexual self-esteem. These cognitive changes, combined with behavioral modifications and corrective emotional experiences, ultimately led to the adjustment of schemas that contribute to increased sexual self-esteem.

In explaining the results of the present study regarding the effectiveness of VSST for women with vaginismus on their sexual self-assertiveness, the content and application orientation of this type of treatment, which employs specialized techniques, is very important. In the approach of specialized ST, emotional and cognitive issues serve as the main foundations of the problems. Therefore, the primary focus of the therapy is on addressing emotional and cognitive challenges, including depression, physical issues, and anxiety. In discussing this research finding, it can be stated that the main goal of VSST is to promote sexual self-assertiveness as a key component of sexual performance. This therapy addresses both verbal and non-verbal openness, such as expressing emotions and sexual needs in women, by strengthening adult and healthy mentalities. VSST enhances the ability to express feelings, beliefs, and both pleasant and unpleasant emotions, enabling individuals to make suitable decisions and fulfill their desires.

The findings from this study highlight the potential of the VSST as an effective intervention for enhancing sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem in women with vaginismus disorder. By empowering women to explore their sexuality on their own terms, VSST offers a promising alternative to conventional Sensate Focus Therapy. As clinicians continue to seek effective strategies for treating vaginismus, embracing innovative approaches like VSST could lead to more positive outcomes for patients, ultimately fostering healthier sexual relationships and improved emotional well-being.

The present study, like any scientific study, has limitations. Among them, the study was conducted on women aged 20 to 50; therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing the results to women outside this age range. The measurements in the present study were obtained through a questionnaire, which may be associated with social desirability and may not provide very in-depth information

Conclusion

VSST for vaginismus enhances sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem among women with vaginismus by helping them identify their problems.

Acknowledgments: We are grateful to the Research Deputy of Isfahan Islamic Azad University and all the women for their cooperation.

Ethical Permissions: This research is derived from a doctoral dissertation in psychology and has received approval from the ethics committee of the secretariat of the Academic Committee of Ethics in Biomedical Research, with license number (IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1400.228). Additionally, this research has been registered with the Iranian Clinical Trial Registration Center (IRCT) under the IRCTID: IRCT20211120053113N1.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors of this paper do not have any conflict of interest in the article. Furthermore, the paper is done at personal expense.

Authors' Contribution: Kakavand R (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (60%); Khayatan F (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Golparvar M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%)

Funding/Support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Sexual health and positive marital relationships have well-documented effects on physical, mental, and social well-being [1]. Consequently, any disorder in this area can impact sexual health [2]. Among these disorders, pelvic-genital penetration pain disorder (vaginismus) is defined as a persistent issue characterized by pain, fear, or muscle stiffness in anticipation of, during, or after attempts at vaginal penetration, lasting for at least six months [3]. The prevalence of vaginismus has been reported to range from 5% to 42% [4]. In selected Iranian studies, the incidence of vaginismus in the general female population has been reported as between 0.4% and 8% [5].

Physical factors affecting vaginismus include urinary tract infections, cysts, eczema, pelvic inflammation, complications from childbirth, such as pain due to vaginal delivery or difficult delivery, abortion, age-related changes, such as menopause and hormonal fluctuations, vaginal dryness, pelvic lesions, and the side effects of medications [6].

Factors, such as pregnancy phobia, painful intercourse, recurrent medical issues with pelvic muscles, generalized anxiety, performance anxiety (concern about not performing well during sex), previous negative sexual experiences, negative beliefs about sex, feelings of guilt, emotional trauma, and other unhealthy sexual emotions, relationship problems with a spouse, including abuse, lack of emotional connection, fear of commitment, lack of confidence and trust, and a sense of loss of control, as well as repressed memories of childhood experiences, such as strict parenting, unbalanced religious restrictions, exposure to shocking sexual scenes and images, and inadequate sexual education, are among the psychological factors that can affect vaginismus disorder [7, 8]. In patients with vaginismus disorder, these fears create distress in many important areas of life [9]. Self-assertive individuals express their feelings and desires openly, without shame [10]. According to behaviorism theory, women with vaginismus learn a lack of sexual self-assertiveness through reinforcement or punishment, such as a lack of verbal openness regarding sexual issues, within the cultural and educational context of their families [11]. These studies indicate that women who are unwilling to express their sexual desires to their husbands have a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction disorders, including vaginismus [12, 13].

One of the factors that influence sexual performance is defined as a person’s positive attitude and perception of their sexual status, based on which they adjust their behavior. This aspect of interpersonal functioning also plays a role in the development of a healthy sex life; it is fluid and changes under the influence of various conditions [14]. Research has shown that there is a reciprocal relationship between women’s sexual self-esteem and their sexual performance, with women experiencing sexual disorders being more likely to suffer from low sexual self-esteem. Women who have sexual dysfunction and feelings of sexual incompetence tend to have low sexual self-esteem and may withdraw from sexual activity [15].

Previous studies have demonstrated that symptoms of vaginismus disorder are reduced through conventional schema therapy (ST) [16, 17]. ST focuses on the foundations of behavior and the deepest cognitive structures of individuals. Primary maladaptive schemas are dysfunctional emotional and cognitive patterns that are formed in childhood and are repeated throughout life [4].

Vaginismus-specific schema therapy (VSST) for vaginismus disorder examines various sexual beliefs and attitudes that contribute to women’s sexual dysfunction in relation to sexual schemas and marital compatibility [18]. The presence of negative beliefs and thoughts, such as criticism and a negative self-image, can adversely affect women’s pleasure and desired sexual function, leading to negative emotions such as anger, fear, shame, and guilt. Therefore, ST can improve vaginismus disorder and the associated problems by addressing unhealthy mental patterns [19]. A review of the research findings indicates that ST can enhance functioning by focusing on women’s issues, particularly their relationships with their spouses [20]. Correcting and adjusting initially incompatible schemas and strengthening a healthy adult mentality have resulted in improvements and increases in sexual self-esteem. VSST emphasizes eliciting emotions related to primary incompatible schemas, which helps identify behaviors and attitudes that threaten personal value and self-esteem. Reparenting for women suffering from vaginismus disorder was conducted to enhance their emotions and address the relative satisfaction of unmet needs, thereby increasing their self-esteem. This reparenting process focused on the primary unfulfilled needs of women with vaginismus disorder by providing emotional support and addressing effective factors in modulating schemas, ultimately strengthening the adult mentality and fostering a sense of worth [19, 21].

Therefore, research on the effectiveness of ST in improving self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem in women with vaginismus is of particular importance, as vaginismus not only negatively impacts the sexual quality of life for women but can also lead to emotional problems and issues within marital relationships. Considering that many women avoid seeking help from healthcare professionals due to feelings of shame and embarrassment, providing effective and indirect solutions like ST can help increase access to and acceptance of treatment. Additionally, this research can identify and enhance self-assertion skills and sexual self-esteem in women, enabling them to approach their relationships with a stronger sense of self. ST assists women in strengthening their self-assertion abilities, allowing them to express their sexual needs and desires more easily while identifying and changing negative schemas can further enhance individual self-esteem.

Despite ST being recognized as an effective approach for treating psychological disorders, there are limited studies on its impact on women with vaginismus, particularly concerning their self-assertion and sexual self-esteem. Most existing research has primarily focused on the physiological and medical aspects of vaginismus, while the emotional and psychological dimensions of this disorder have received less attention. Additionally, the cultural and social influences on the experience of vaginismus and treatment methods have also been less studied. This topic can contribute to a better understanding of the challenges women face when dealing with this disorder. Furthermore, most existing research concentrates on a specific type of treatment, while examining the effects of combined methods (such as integrating ST with other treatments) may yield better outcomes. Ultimately, the results of this research could significantly contribute to the development of innovative therapeutic methods and improve the sexual quality of life in society. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of an ST package specifically designed for women with vaginismus, as well as conventional ST methods, on the self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem of women with vaginismus disorder.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental research employed a pre-test, post-test, and follow-up design, including a control group, and was conducted on women (aged 20 to 50 years) with vaginismus who were referred to the obstetrics and gynecology clinic of Payambaran Hospital in Tehran in 2021. This research began from the fall of 2021 to the spring of 2022 and the follow-up was conducted 45 days after the intervention.

A total of 45 women were selected as a sample using a targeted approach. The sample size was calculated to include 20 individuals in each group based on similar studies [18], taking into account an effect size of 0.40, a confidence level of 0.95, a test power of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10%. Consequently, 60 cases were chosen as samples using the purposive sampling method according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The three groups were then randomly assigned using a simple lottery method, including one group receiving specialized ST for women with vaginismus, a conventional ST group, and a control group.

The inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of vaginismus by a gynecologist, not receiving concurrent medical and psychological treatments, having at least a high school diploma, and a minimum of one year of cohabitation. The exclusion criteria included a lack of cooperation from participants in completing homework assignments and absence from more than two treatment sessions. In addition to obtaining an ethics code, the study adhered to ethical principles, such as confidentiality, using data solely for research purposes, ensuring participants had the freedom and autonomy to continue their involvement in the study, and providing detailed information to participants if they requested the results, along with training for the control group after the completion of the intervention. Three groups were observed in the study.

The tools used included Halbert’s Sexual Self-Assertion Questionnaires (1992) and Zeanah and Schwarz’s Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women (SSEI-W, 1996). Additionally, the Persian version of these tools was utilized.

Halbert's Sexual Self-Assertiveness Questionnaire: The Persian version of Halbert’s Sexual Self-Assertiveness Index was utilized, which includes 25 items on a Likert scale. The response options range from “always”=0 to “never”=4. Items 3, 4, 5, 7, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, and 23 are scored in reverse. The range of test scores is from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater sexual self-assertiveness. The validity of this test was established by David Farley, with a coefficient of 0.86. In a study involving 60 married women, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.84 [22].

Women's Sexual Self-Esteem Questionnaire by Zeanah and Schwarz (SSEI-W): This questionnaire consists of 35 items and was developed to measure women’s effective responses regarding their sexual self-evaluation. The questions are answered on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” This questionnaire includes five subscales that reflect various aspects of sexual self-esteem, including experience and skill, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and conformity. By summing the scores from these five areas, a total score for the scale is obtained, with a higher score indicating greater sexual self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire scale is 0.92, with individual coefficients of 0.84 for attractiveness, 0.88 for control, 0.80 for moral judgment, and 0.80 for conformity. In the research conducted by Zeanah and Schwarz [23], the convergent validity was confirmed through correlation with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (r=0.57). In the study by Farokhi and Share involving a sample of 510 Iranian married women, the same five factors from the original version were identified through factor analysis of the questionnaire. The internal consistency coefficient for the items across the entire sample was 0.88, and the correlation coefficients between each item and the total score of the scale ranged from 0.54 to 0.72. The test-retest reliability coefficient for the entire scale was reported as 0.91, with coefficients for its five subscales ranging from 0.82 to 0.94 [24]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was determined using Cronbach’s alpha method, resulting in a coefficient of 0.91.

At first, women with vaginismus disorder completed the questionnaires during the pre-test phase. The data collection process involved randomly assigning the participants to three groups, including two treatment groups and one control group. Each of the treatment groups received simultaneous group therapy sessions at the women’s clinic. After the final intervention session, women from all three groups completed the questionnaires again during the post-test and follow-up stages. The VSST for women with vaginismus and conventional ST were each conducted over ten sessions of 90 minutes, with two sessions per week, totaling five consecutive weeks. The interventions were facilitated by an experienced ST therapist with several years of treatment experience. The control group did not receive any treatment until after the training of the two treatment groups was completed. The VSST for women suffering from vaginismus has been utilized for the first time in this study, following initial content, scientific, and professional validation. The process of compiling the VSST began with in-depth interviews and content analysis of relevant texts in this field. Using the Attride-Stirling thematic network analysis [25], the necessary organizing and foundational topics for ST for women with vaginismus were identified. At this stage, the content validity ratio (CVR), calculated by three independent coders, was equal to one. Subsequently, therapeutic techniques for each subject were extracted through conventional content analysis. An expert panel consisting of six psychologists with more than ten years of treatment experience then developed a combination of therapeutic techniques aimed at improving women’s mental health over ten sessions. The order of the treatment package was established, and the compiled package was reviewed by six expert judges in the field of health psychology. After incorporating the judges’ corrections, an overall agreement coefficient of 0.9 was obtained for the treatment package. Following expert approval, a pilot study was conducted to assess the preliminary effectiveness of the designed package on six women suffering from vaginismus disorder, confirming the initial validity of the package. The ST group was treated using a validated treatment package, Young et al.'s ST package in Iran [17] (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Description of vaginismus-specific schema therapy (VSST) [19]

Table 2. Description of schema therapy [17]

In the statistical analysis of the data, descriptive statistics, such as the mean and standard deviation were calculated. At the inferential level, the normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, the equality of error variances was evaluated through Levene’s test, and the equality of the variance-covariance matrix was determined using the M-box test. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. The data were analyzed using SPSS 22. The acceptable level of significance was set at a minimum of 0.05 and a maximum of 0.001.

Findings

The three research groups were compared in terms of age, education status, and occupation using a Chi-square test and there were no significant differences in the aforementioned demographic characteristics among the three groups. The mean results for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem in women showed that the two treatment groups exhibited greater changes than the control group in the post-test and follow-up (45 days after the end of the intervention; Table 3).

Table 3. Mean self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem in the vaginismus-specific schema therapy (VSST), schema therapy (ST), and control groups at three time points

Before repeated-measures ANOVA, the statistical assumptions for this analysis were examined. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem indicated that the distribution of these two parameters was significant (p=0.001). Additionally, the results of Levene’s test showed that the variances among the study groups for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem were equal (p=0.001). The M-box test for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem indicated the equality of the variance-covariance matrix, and the interaction of group membership with the pre-test also demonstrated the equality of the slopes of the regression lines (p=0.001). Therefore, the repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that, in terms of the intra-group effect, both the time factor and its interaction with group membership indicated significant differences for both self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem over time and in relation to the three research groups (p=0.001). Thus, 90% and 97% of the variance in sexual self-assertiveness, and 83% and 94% of the variance in sexual self-esteem, were attributable to the independent parameters (one of the two treatments in the study), both confirmed with 100% power. Furthermore, the intergroup effect indicated a significant difference (p=0.001) in both sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem based on the group factor. The parametric eta squared for the group factor was equal to 0.93 and 0.97, respectively, and the power of the test was equal to 1. This indicated that the variance analysis conducted with 100% power revealed a significant difference of 93% and 97% between at least one of the experimental groups (VSST & ST) and the control group in terms of sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem (Table 4).

Table 4. Results of the repeated-measures ANOVA for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem

To determine the pairwise differences between the three research groups, Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed, which indicated significant differences in sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem between the pre-test and post-test, as well as between the post-test and follow-up. Additionally, significant differences were found between the two treatment groups and the control group (p=0.001), and between the VSST and ST groups (p=0.001). Therefore, the effectiveness of the VSST and conventional ST differed in terms of sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem in women with vaginismus. Specifically, there were significant differences between the pre-test and post-test, between the post-test and follow-up, and between the two treatment groups and the control group (Table 5).

Table 5. Results of the Bonferroni follow-up test comparing research groups for self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem

Discussion

This study, which was conducted to compare the effectiveness of the VSST with conventional ST on the sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem of women with vaginismus disorder, demonstrated that both treatments significantly improved sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem. In other words, the comparison of the means of the two intervention groups with the control group indicated that the VSST had a greater effect on enhancing self-assertiveness and sexual self-esteem than the ST.

Vaginismus, characterized by involuntary pelvic floor muscle contractions during attempted vaginal penetration, poses significant psychological and emotional challenges for affected women. This condition not only disrupts sexual intimacy but can also lead to diminished self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy. Therefore, effective therapeutic interventions are essential for restoring sexual health and enhancing overall well-being.

The findings of this study underscored the potential advantages of the VSST compared to conventional ST. While ST has long been recognized for its role in reducing anxiety and enhancing intimacy through gradual exposure, it often emphasizes partner involvement and may inadvertently reinforce feelings of pressure or inadequacy. In contrast, VSST empowers women to take control of their own sexual experiences in a safe and private setting. This autonomy can foster a sense of agency that is particularly beneficial for those grappling with vaginismus. When comparing the results of the present research with similar studies, it is important to note that, due to the novelty of the VSST, no research was found that completely aligns with this study in terms of the subject matter. However, considering the general orientation of the interventions, it can be stated that the results obtained from this study regarding the effectiveness of conventional ST in increasing women’s sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem are consistent with previous studies that highlight the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and specialized health education for marital relationships. The beneficial effects on sexual self-assertiveness [13, 21] and the effectiveness of ST for vaginismus on other parameters related to marital relations, such as sexual schemas and marital adjustment [18], are also consistent with these findings. The results of another study regarding the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and sexual self-esteem in females indicated that couple therapy based on acceptance and commitment, as well as cognitive self-compassion, is significantly effective in improving sexual adjustment and self-esteem compared to the control group [26]. According to Beck’s schema theory (1996), when the incompetence schema is activated in a sexual situation, individuals are likely to actively seek schema-congruent cues, ignore conflicting stimuli, and exaggerate the negative interpretation of the event. For instance, thoughts, such as “I am incompetent,” “I am ineffective,” and “I am a failure” may arise [27].

The mechanisms, through which VSST enhances sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem warrant further exploration. Engaging in self-stimulation allows women to cultivate body awareness and comfort with their own anatomy, which is crucial for overcoming the fear and anxiety associated with penetration. By normalizing the experience of pleasure and reducing performance pressure, VSST may facilitate a more positive self-image and greater sexual confidence. This empowerment can translate into improved communication with partners, leading to healthier sexual relationships.

Our findings align with existing literature that emphasizes the importance of self-exploration in overcoming sexual dysfunction. Research has demonstrated that interventions promoting body positivity and sexual self-acceptance can significantly improve sexual functioning and emotional well-being. For instance, studies have shown that women who engage in self-exploration report higher levels of sexual satisfaction and self-esteem. By situating our results within this broader context, we reinforce the argument that VSST represents a viable alternative or complement to traditional therapeutic approaches.

The implications for clinical practice are profound. Therapists working with women experiencing vaginismus should consider integrating VSST into their treatment protocols. Not only does this technique provide a practical tool for overcoming physical barriers to penetration, but it also addresses the psychological components of sexual dysfunction. By promoting self-assertiveness, clinicians can help patients reclaim their sexual identities and foster healthier relationships.

In explaining this research finding, it can also be stated that the main goal of the VSST for the sexual self-esteem of women with vaginismus disorder is to address the schemas that contribute to weak sexual self-esteem, such as abandonment/instability, emotional deprivation, stubbornness/extreme fault-finding, mistrust/abuse, social isolation/alienation, failure, dependency/incompetence, and punishment. VSST, by bringing these schemas that undermine sexual self-esteem to the active conscious level and overcoming emotional distance, creates the context for a genuine sense of value associated with sexual self-esteem. The use of cognitive techniques was effective in improving the cognitive distortions of women with vaginismus, thereby enhancing their sexual self-esteem. These cognitive changes, combined with behavioral modifications and corrective emotional experiences, ultimately led to the adjustment of schemas that contribute to increased sexual self-esteem.

In explaining the results of the present study regarding the effectiveness of VSST for women with vaginismus on their sexual self-assertiveness, the content and application orientation of this type of treatment, which employs specialized techniques, is very important. In the approach of specialized ST, emotional and cognitive issues serve as the main foundations of the problems. Therefore, the primary focus of the therapy is on addressing emotional and cognitive challenges, including depression, physical issues, and anxiety. In discussing this research finding, it can be stated that the main goal of VSST is to promote sexual self-assertiveness as a key component of sexual performance. This therapy addresses both verbal and non-verbal openness, such as expressing emotions and sexual needs in women, by strengthening adult and healthy mentalities. VSST enhances the ability to express feelings, beliefs, and both pleasant and unpleasant emotions, enabling individuals to make suitable decisions and fulfill their desires.

The findings from this study highlight the potential of the VSST as an effective intervention for enhancing sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem in women with vaginismus disorder. By empowering women to explore their sexuality on their own terms, VSST offers a promising alternative to conventional Sensate Focus Therapy. As clinicians continue to seek effective strategies for treating vaginismus, embracing innovative approaches like VSST could lead to more positive outcomes for patients, ultimately fostering healthier sexual relationships and improved emotional well-being.

The present study, like any scientific study, has limitations. Among them, the study was conducted on women aged 20 to 50; therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing the results to women outside this age range. The measurements in the present study were obtained through a questionnaire, which may be associated with social desirability and may not provide very in-depth information

Conclusion

VSST for vaginismus enhances sexual self-assertiveness and self-esteem among women with vaginismus by helping them identify their problems.

Acknowledgments: We are grateful to the Research Deputy of Isfahan Islamic Azad University and all the women for their cooperation.

Ethical Permissions: This research is derived from a doctoral dissertation in psychology and has received approval from the ethics committee of the secretariat of the Academic Committee of Ethics in Biomedical Research, with license number (IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1400.228). Additionally, this research has been registered with the Iranian Clinical Trial Registration Center (IRCT) under the IRCTID: IRCT20211120053113N1.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors of this paper do not have any conflict of interest in the article. Furthermore, the paper is done at personal expense.

Authors' Contribution: Kakavand R (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (60%); Khayatan F (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Golparvar M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%)

Funding/Support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Sexual Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2024/07/28 | Accepted: 2024/10/26 | Published: 2024/11/1

Received: 2024/07/28 | Accepted: 2024/10/26 | Published: 2024/11/1

References

1. Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, Nasiri M, Roozbeh N, Zare F. Sexual function among women with vaginismus: A biopsychosocial approach. J Sex Med. 2023;20(3):298-312. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jsxmed/qdac049]

2. Maldonado M, Nardi AE, Sardinha A. The role of vaginal penetration skills and vaginal penetration behavior in genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. J Sex Marital Ther. 2023;49(7):816-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2023.2193587]

3. Dias-Amaral A, Marques-Pinto A. Female genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder: Review of the related factors and overall approach. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2018;40(12):787-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1055/s-0038-1675805]

4. Hamidi S, Shareh H, Hojjat SK. Comparison of early maladaptive schemas and attachment styles in women with vaginismus and normal women. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2015;18(155, 156):9-18. [Persian] [Link]

5. Sabetghadam S, Keramat A, Malary M, Rezaie Chamani S. A systematic review of vaginismus prevalence reports. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2019;19(3):263-71. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jarums.19.3.263]

6. Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, Bergeron S, Pukall C, Zolnoun D, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):607-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167]

7. Omidvar Z, Bayazi MH, Faridhosseini F. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy on cognitive emotion regulation in women with vaginismus. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2021;24(9):40-9. [Persian] [Link]

8. Heydarian M, Gholamzadeh-Jefreh M, Shahbazi M. Explaining the antecedent's vaginismus and dyspareunia disorder in women: A qualitative study. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2022;20(6):544-55. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JSMJ.20.6.2365]

9. Erdős C, Kelemen O, Pócs D, Horváth E, Dudás N, Papp A, et al. Female sexual dysfunction in association with a sexual history, sexual abuse and satisfaction: A cross-sectional study in Hungary. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):1112. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jcm12031112]

10. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Link]

11. Zgueb Y, Ouali U, Achour R, Jomli R, Nacef F. Cultural aspects of vaginismus therapy: A case series of Arab-Muslim patients. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;3(12):1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1754470X18000119]

12. Sharifain M, Saffarinia M, Alizadeh Fard S. Structural model of vaginismus disorder based on marital adjustment, sexual self-disclosure, sexual anxiety and social exchange styles. J Res Psychol Health. 2019;12(4):48-65. [Persian] [Link]

13. Sánchez-Fuentes M, Santos-Iglesias P. Sexual satisfaction in Spanish heterosexual couples: Testing the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016;42(3):223-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2015.1010675]

14. Jangi S, Nourizadeh R, Sattarzadeh-Jahdi N, Farvareshi M, Mehrabi E. The effect of cognitive-behavioural therapy and sexual health education on sexual assertiveness of newly married women. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):201. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-023-04708-w]

15. Tourrilhes E, Veluire M, Hervé D, Nohuz E. Obstetric outcome of women with primary vaginismus. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;32:160. [French] [Link] [DOI:10.11604/pamj.2019.32.160.16083]

16. Abdnezhad R, Simbar M. A review of vaginismus treatments. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2021;24(7):83-97. [Persian] [Link]

17. Young J, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME. Schema therapy: A practitioner's guide. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Link]

18. Bernstein DP, Keulen-De Vos M, Clercx M, De Vogel V, Kersten GC, Lancel M, et al. Schema therapy for violent PD offenders: A randomized clinical trial. Psychol Med. 2023;53(1):88-102. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0033291721001161]

19. Kakavand R, Khayatan F, Golparvar M. The effectiveness of vaginismus-specific schema therapy on the fear of intimacy in women with vaginismus disorder. Sci J Nurs Midwifery Paramed Fac. 2024;9(3):212-24. [Persian] [Link]

20. Damiris IK, Allen A. Exploring the relationship between early adaptive schemas and sexual satisfaction. Int J Sex Health. 2023;35(1):13-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/19317611.2022.2155897]

21. Amini A, Ghorbanshirudi S, Khalatbari J. Comparison of the effectiveness of teaching emotion management strategies based on emotion-focused couple therapy approach and couple therapy based on schema therapy on sexual satisfaction and family functioning. J Health Syst Res. 2023;18(4):297-306. [Persian] [Link]

22. Sayyadi F, Golmakani N, Ebrahimi M, Saki A. The Relationship between Sexual Assertiveness and Positive Feelings towards Spouse in Married Women. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2018;6(3):1305. [Link]

23. Zeanah PD, Schwarz JC. Reliability and validity of the sexual self-esteem inventory-women. Assessment. 1996;3(1):1-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/107319119600300101]

24. Farokhi S, Shareh H. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the sexual self-esteem index for woman short form. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2014;20(3):252-63. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t54661-000]

25. Mojtahedzadeh SP, Teimory S, Nayyeri M, Isanazar A. Presenting the model of sexual performance of postmenopausal women based on sexual self-assertiveness with the mediating role of state-attribute anxiety and sexual self-esteem. J Appl Fam Ther. 2023;4(1):356-79. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.61838/kman.aftj.4.1.18]

26. Shareh H. The relationship between early maladaptive schemas and sexual self-esteem in female sex workers. J Fundam Ment Health. 2016;18(5):249-58. [Persian] [Link]

27. Mohajeri A, Narimani M, Kazemi R. Comparison of the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment training and cognitive self-compassion on marital adjustment and sexual self-esteem of couples exposed to divorce. J Mod Psychol Res. 2022;16(64):170-92. [Persian] [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |