Volume 12, Issue 3 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(3): 431-438 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yasin N, Ekasari M, Prabasworo W, Arom S, Ridhayani F. Knowledge Level and Information Needs of Patients with Diabetes in Yogyakarta City, Indonesia. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (3) :431-438

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76292-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-76292-en.html

1- Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2- Department of Management and Community Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

3- Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2- Department of Management and Community Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

3- Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 637 kb]

(2043 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (833 Views)

Full-Text: (67 Views)

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a long-term chronic disease caused by elevated blood glucose levels due to insufficient insulin production or ineffective insulin usage. According to an International Diabetes Federation (IDF) report in 2021, this disease is directly responsible for 1.5 million deaths annually. Globally, about 422 million individuals suffer from DM, with the majority living in low- and middle-income nations, including Indonesia [1].

DM has a significantly high prevalence in Indonesia, and its incidence continues to rise annually. Indonesia ranks among the top seven nations worldwide in terms of diabetes prevalence [1]. Based on data from the Indonesia Basic Health Research from 2013 to 2018, the proportion of diabetes prevalence in Indonesia increased from 6.9% to 8.5%. Among the 38 provinces in Indonesia, Yogyakarta Special Region (DIY) Province ranks second nationally. The prevalence of individuals diagnosed with DM in Yogyakarta City is 4.79%, which corresponds to approximately 15,540 individuals [1, 2]. Considering the significant rise in DM cases in Indonesia, healthcare providers and patients must have a sufficient understanding of DM to effectively manage and treat the disease and its complications [3, 4].

The patient’s understanding of DM enables them to independently implement an appropriate treatment regimen throughout their lifetime. DM is a multifaceted condition; therefore, patients with DM have specific information needs that differ from one another [5]. The patients’ needs for information on all diabetes-related topics vary among subgroups affected by factors such as age, level of education, types, and duration of diabetes, comorbid conditions, level of diabetes knowledge, gender-related factors, and changes in information needs along the disease’s progression [6, 7].

The quality and advancement of health systems also affect the variance in information needs among diabetic patients [8, 9]. Several studies have revealed distinct needs for diabetes-related information among Asians and Europeans [8, 10, 11]. However, there have been a limited number of studies conducted in Indonesia, specifically in Yogyakarta, focusing on patients’ perspectives regarding DM information needs [12].

On the other hand, the role of pharmacists in community health centers in providing pharmaceutical services has not yet been optimized. The high workload experienced by pharmacists is evident, often due to understaffing and the need to handle numerous administrative and technical tasks. Pharmacists’ responsibilities include counseling and monitoring. Therefore, integrating pharmacists into the primary health care system and recognizing their significant contribution to improving the quality of health services is greatly needed [13]. Consequently, a study in Yogyakarta City is necessary to gain a better understanding of the current conditions, specifically mapping the prioritization of patient needs and preferences, as well as the types of patient service strategies applied by pharmacists. This will allow for the development and accurate implementation of further strategies to enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Therefore, this study aimed to measure the knowledge level and information needs of patients with DM in Yogyakarta and develop an appropriate strategy to address this issue.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted on patients with DM referring to health centers in Yogyakarta City between January and May 2024. Yogyakarta City has 18 health centers. Eight health centers were selected from these 18 because they have the highest number of diabetic patients. From those eight health centers, we invited registered patients with type 2 DM who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria using an accidental sampling approach. A sample size of 155 patients was determined based on the Slovin formula considering a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a 5% margin of error. We received completed questionnaires with a 100% response rate. After gathering the patients’ data, a follow-up survey was conducted. Of all the pharmacists working at community health centers in Yogyakarta, 16 participated in this study.

Research tools

We used a questionnaire for the patients and a survey form for the pharmacists.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections, including the demographic information chalkiest, the 24-item version of the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ-24), and the researcher-made Diabetes Mellitus Information Questionnaire.

The first section required respondents to provide personal information, such as their age, gender, education level, employment, income, time since DM diagnosis, comorbidities, medications, and blood sugar levels. Then, the DKQ-24 questionnaire was used as a specific standardized instrument to measure the knowledge of patients with DM. We utilized the Indonesian-translated version of the DKQ-24 developed and approved (Cronbach’s α=0.757) by Zakiudin et al. [14]. Each respondent answered 24 questions by choosing one of three responses, namely yes, no, or I do not know. The items were scored as either correct or incorrect. The total number of correct answers was summed, with a higher score indicating better knowledge of DM. We classified the level of patient knowledge into three groups based on their final score; low (score: 0-9), medium (10-16), and high (17-24) [15].

Further, the researcher-made Diabetes Mellitus Information Questionnaire was used to assess the types of information needs by patients and measure the priority of each type of information related to DM. We conducted a literature review to formulate the questions [16]. The measurement of content validity, face validity, and reliability was applied [17]. Three experts and 30 respondents were involved to confirm that this questionnaire was valid. A reliability coefficient of 0.914 was attained using Cronbach’s Alpha. In this final section, respondents were required to answer 21 yes/no questions, which were divided into four domains, including medication, disease, lifestyle, and complications. They were then asked to rank these from most priority to least priority.

We also used a survey form to assess pharmacists’ information. The survey form included two sections, including demographic characteristics and types of pharmacy services in their workplace. The first section included age, gender, level of education, capacity, and duration of practice. The next part consisted of open-ended questions related to pharmacy services, covering the forms of patient education, timing of education, educational materials and media, as well as topics related to implementation challenges. This study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklists [18]. For calculating item difficulty index, we used the formula P=R/T, where P is the item difficulty index, R is the number of correct responses, and T is the total number of responses.

Data analysis

The demographic data of patients with type 2 DM were analyzed using descriptive statistics. We used SPSS version 22 to analyze the data using chi-square test. Moreover, the demographic data of pharmacists were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The results are presented as frequencies, percentages, and detailed descriptions.

Findings

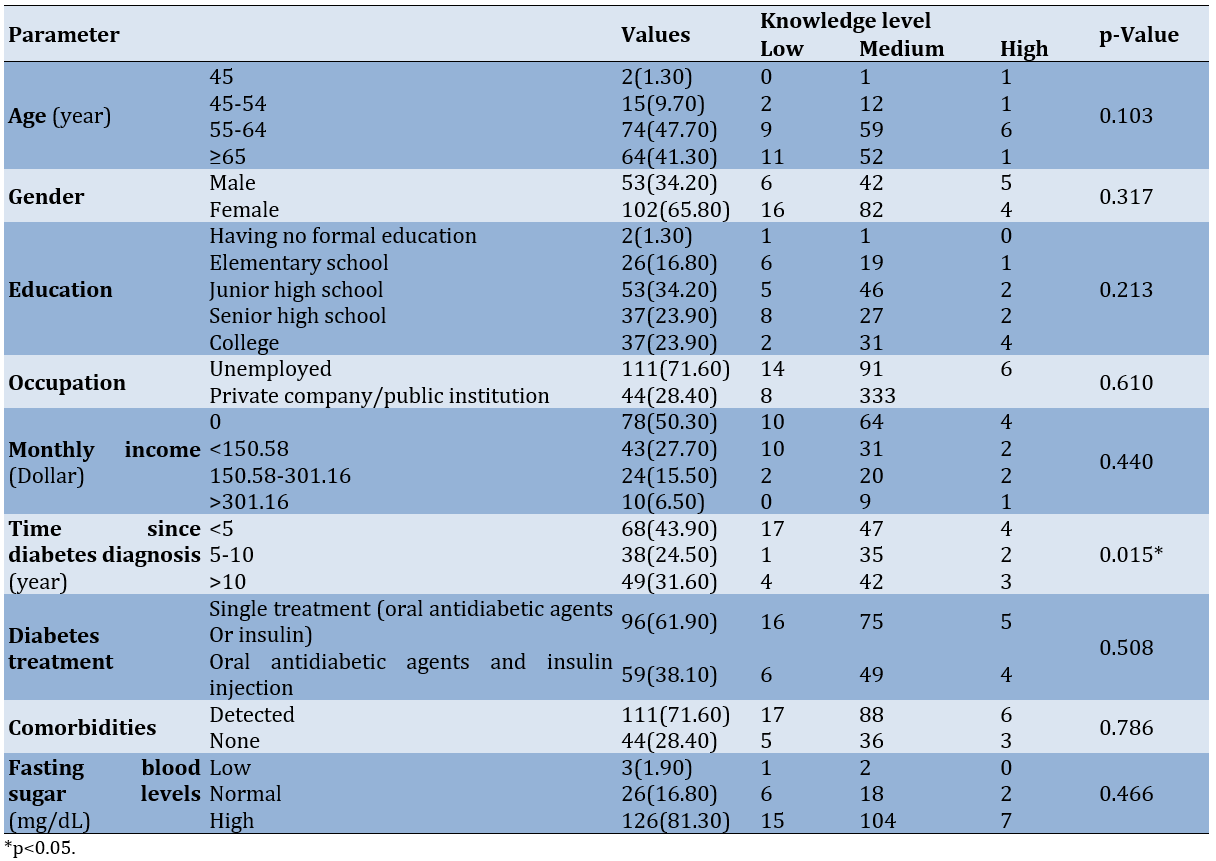

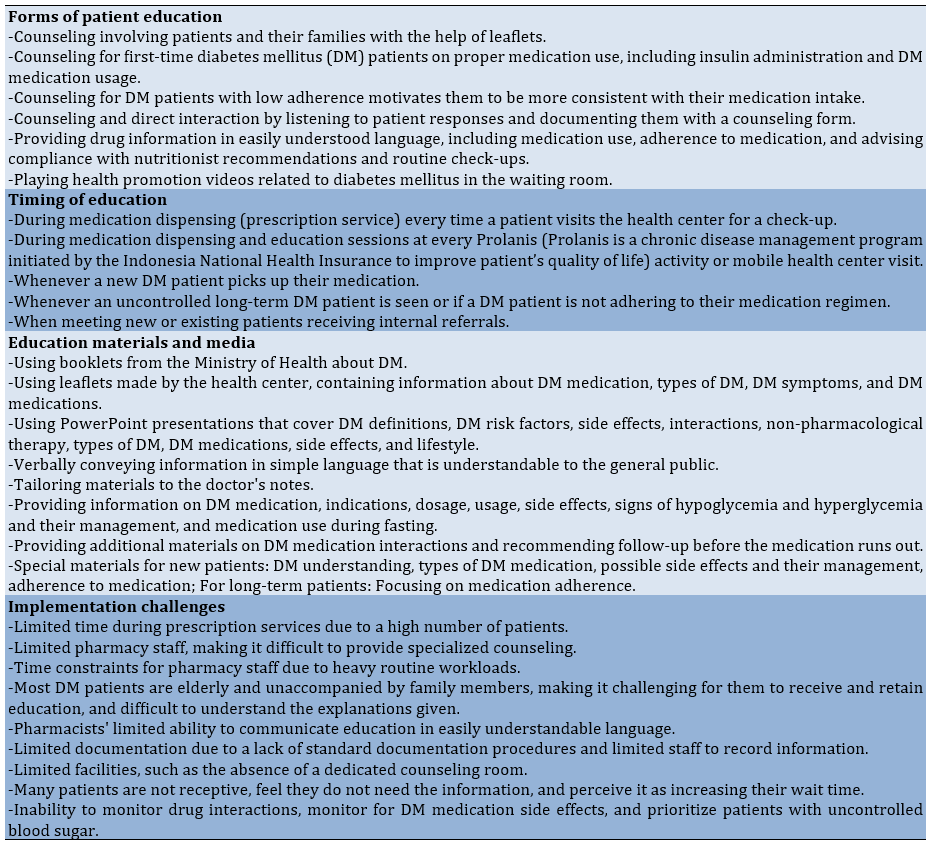

Out of 155 patients with DM, the majority were females, and the age group of 55-64 accounted for almost half of the subjects. Based on educational characteristics, most patients had a junior high school level of education. The majority of the patient participants were unemployed, and half of them had no monthly income. Among all patient participants, nearly half were diagnosed with DM within the past five years, more than half were on single treatment with either an oral antidiabetic drug or insulin, only a quarter of the participants were free from comorbidities, and most were in poor condition with high levels of fasting glucose (Table 1).

The level of knowledge among DM patients at the Yogyakarta City Health Center fell into the moderate category (80%), with a total of 124 patients. The mean level of knowledge according to the DKQ-24 was 12.70±2.91. Only the time since DM diagnosis was associated with patients’ knowledge level (p=0.015). Furthermore, the other characteristics did not have a significant association with the knowledge level (p>0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of patients with diabetes mellitus (n=155)

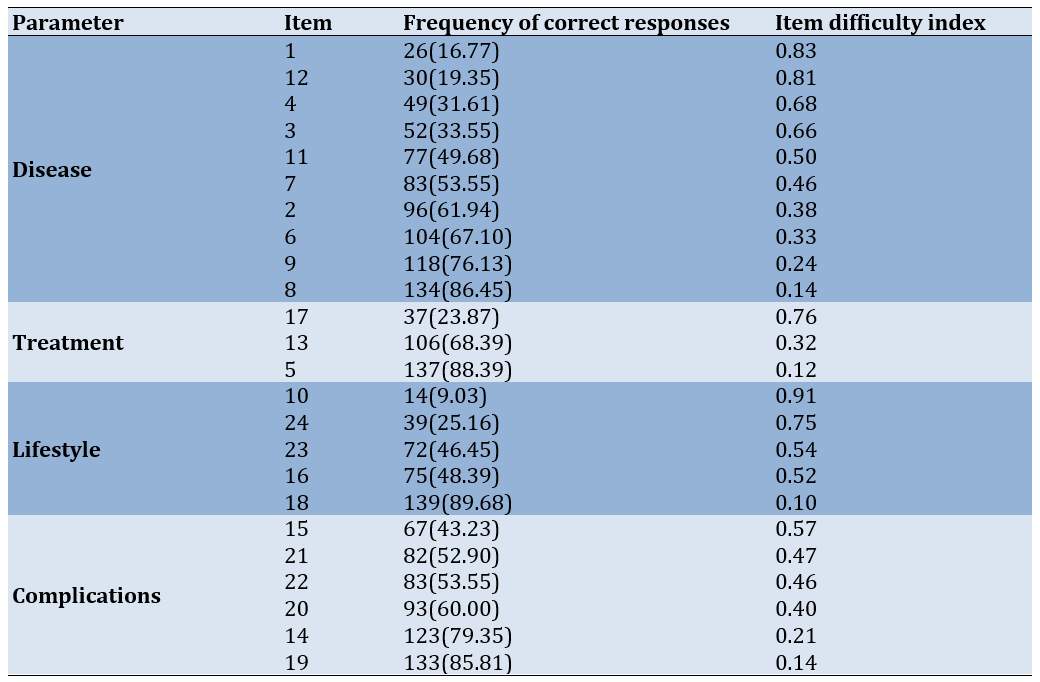

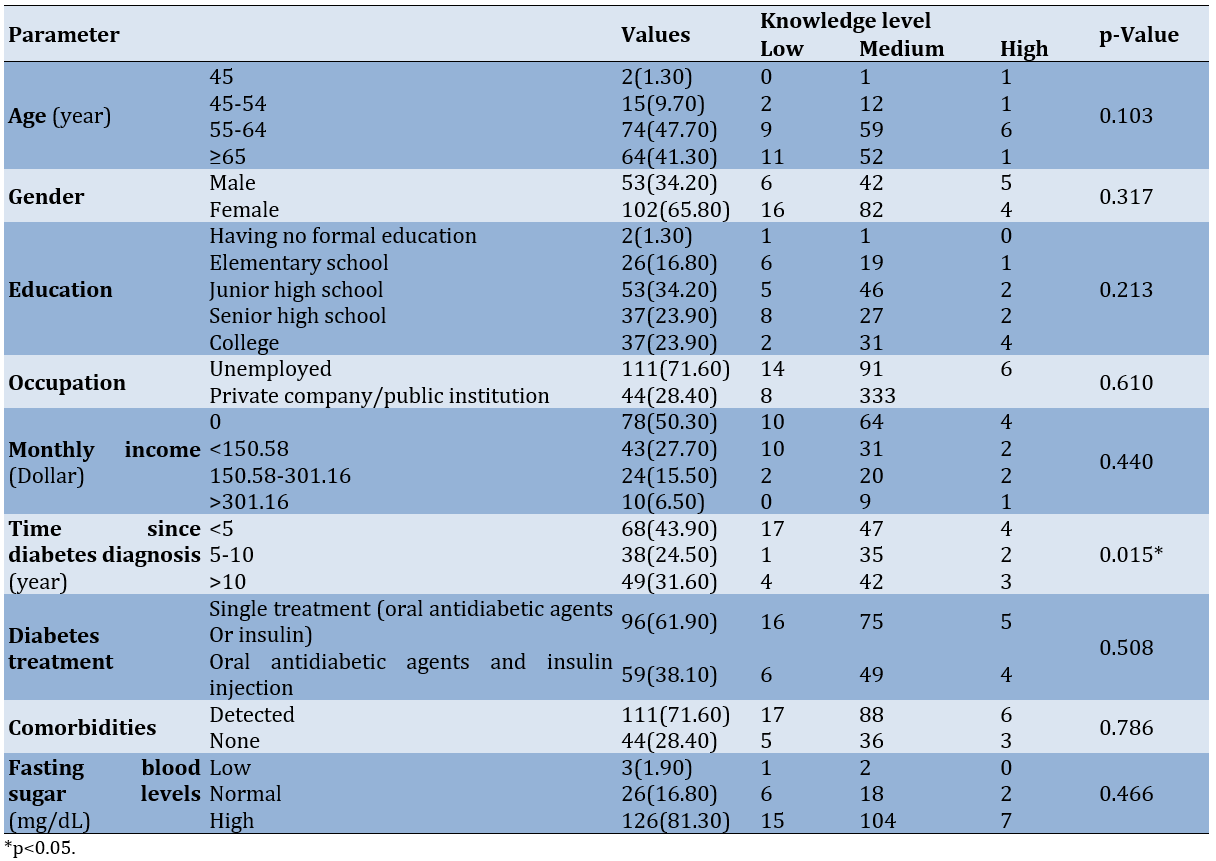

The three items with the most correct responses were items 18, 5, and 8, which addressed food preparation, diabetes conditions without treatment, and the results of fasting glucose level measurement. According to the four key domains, the participants’ responses exhibited distinct item difficulty indices for each question, varying between 0.12 and 0.91. Specifically, item 10 had the highest difficulty score, followed by items 1 and 12, which examined the impact of regular physical examinations on insulin requirements, the consumption of sugar and sweet foods as a cause of DM, and the reasons for insulin reactions (Table 2).

Table 2. Item difficulty of each item in the 24-Item Version of the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (n=155)

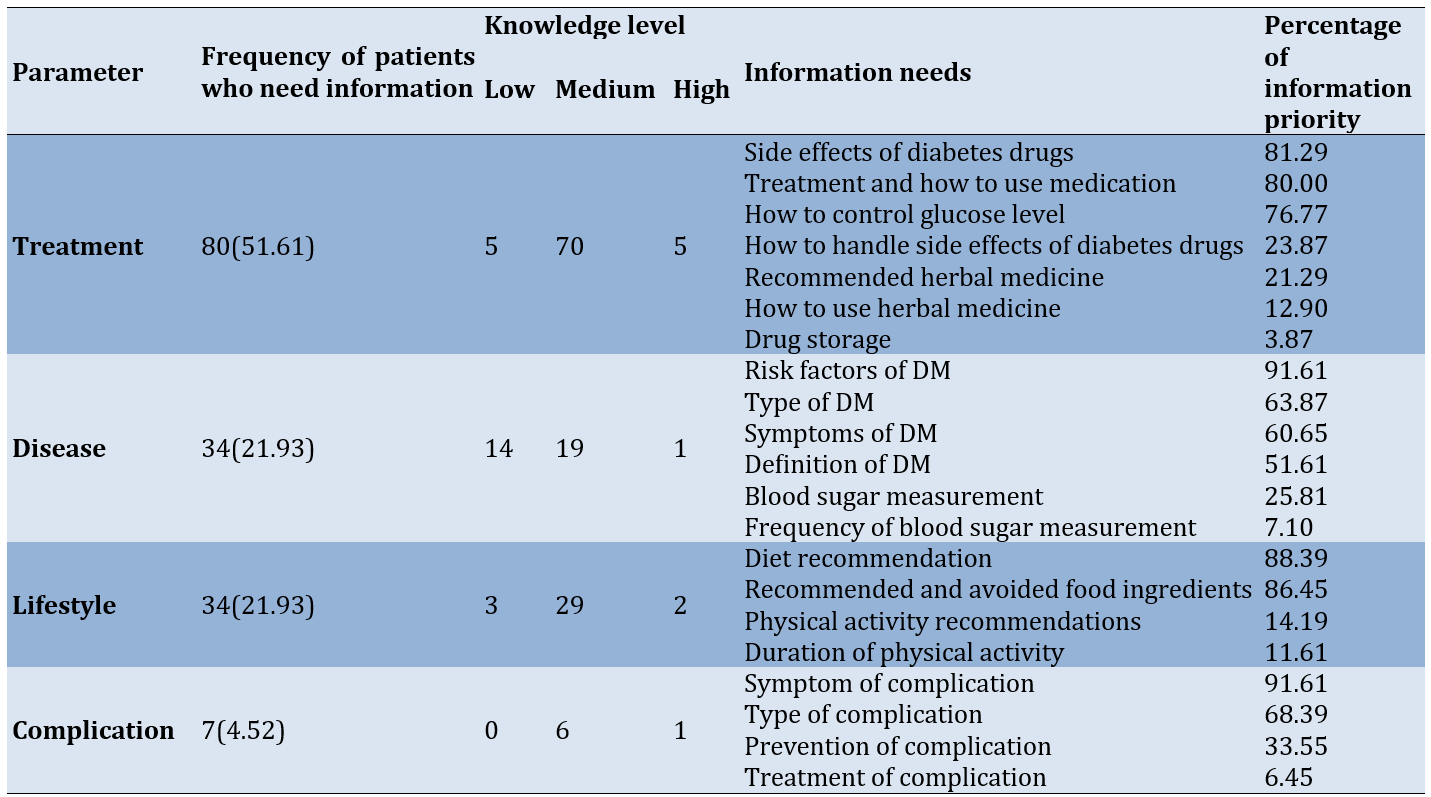

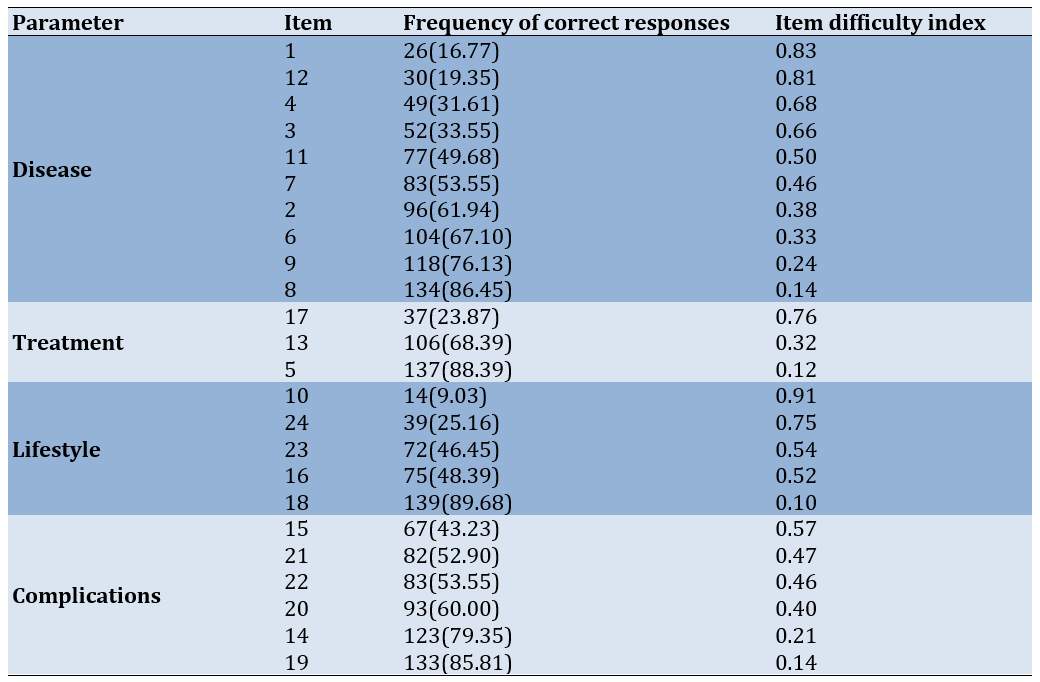

Patients who need information regarding disease, treatment, lifestyle, and complications exhibited moderate knowledge (Table 3).

Table 3. Categories of information needs among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM)

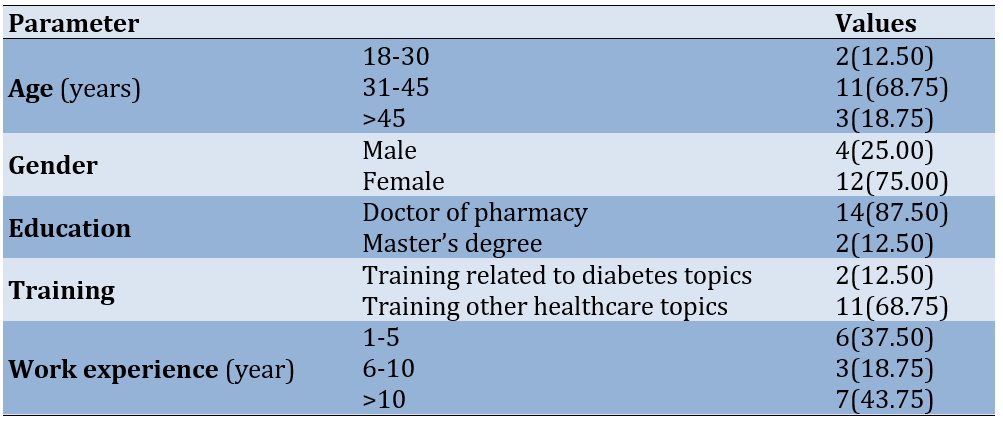

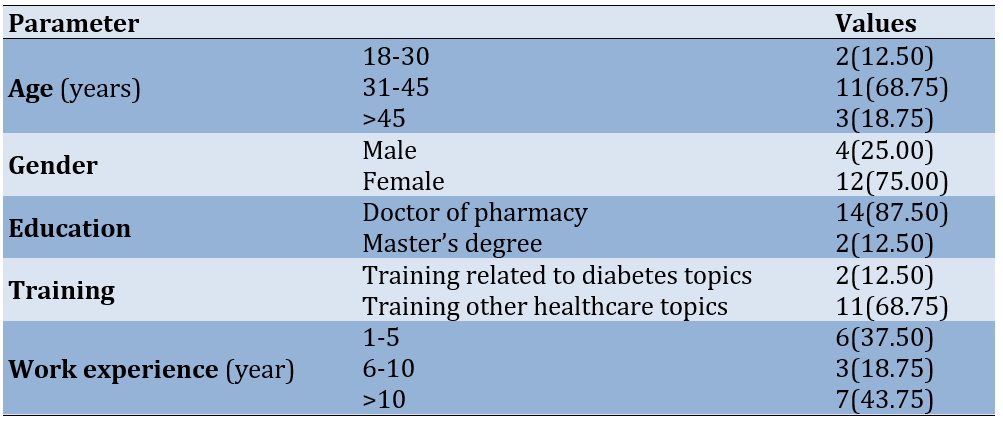

The majority of the pharmacists were women, aged 31-45 years. Only two pharmacists held a master’s degree, and almost half had more than ten years of practical experience. A total of 68.75% reported attending training, but only 12.50% reported participating in specialized training related to DM. Other training attended by the pharmacists included pharmaceutical services for health center pharmacy staff, pharmacovigilance, pharmaceutical management, clinical pharmacy, preceptor training, and specialized tuberculosis training (Table 4).

Table 4. Demographic characteristics of pharmacists (n=16)

The types of services provided by all pharmacists included prescription review and services, as well as education, which encompassed providing drug information and counseling. Other services included monitoring adverse drug reactions (43.75%), drug therapy monitoring (25.00%), and health promotion (12.50%).

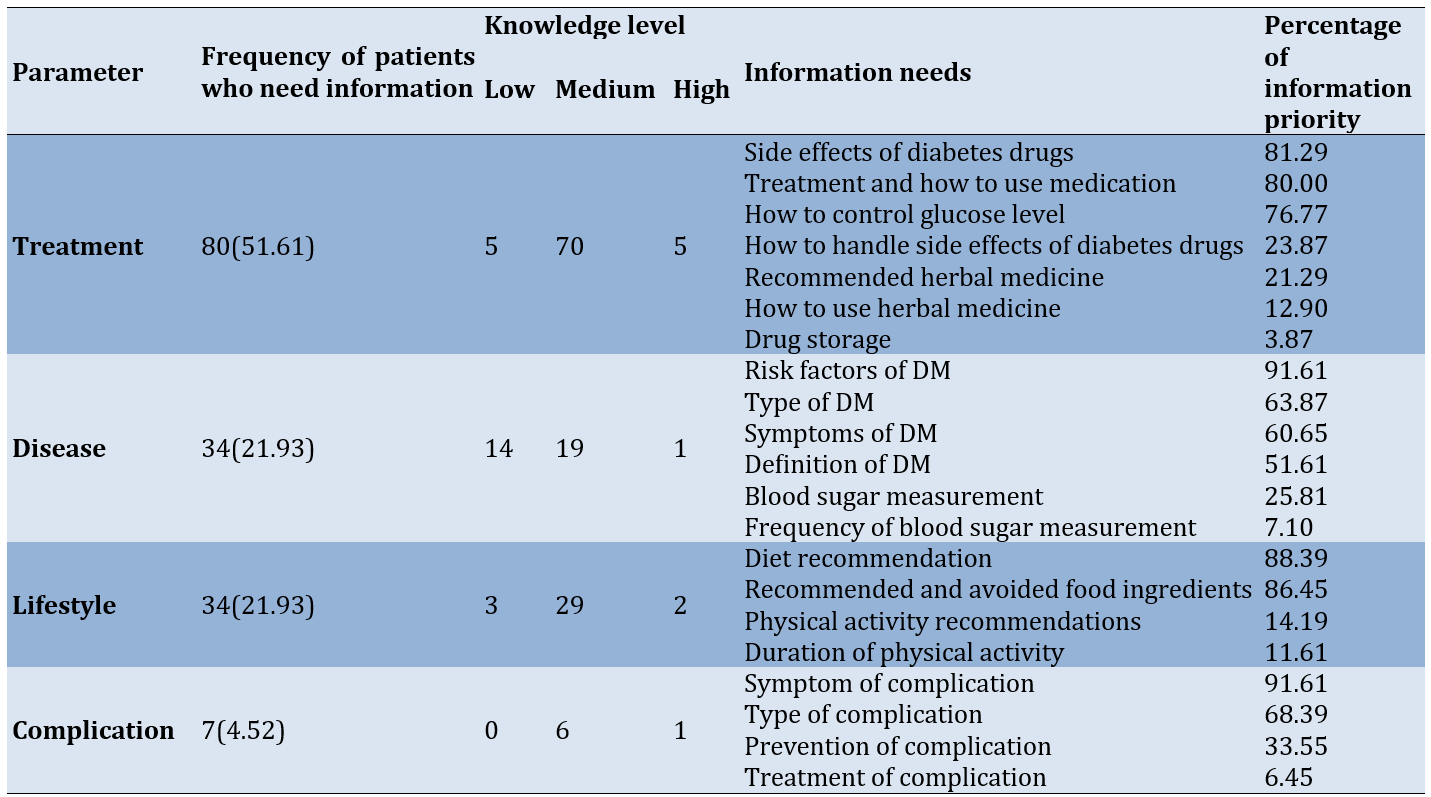

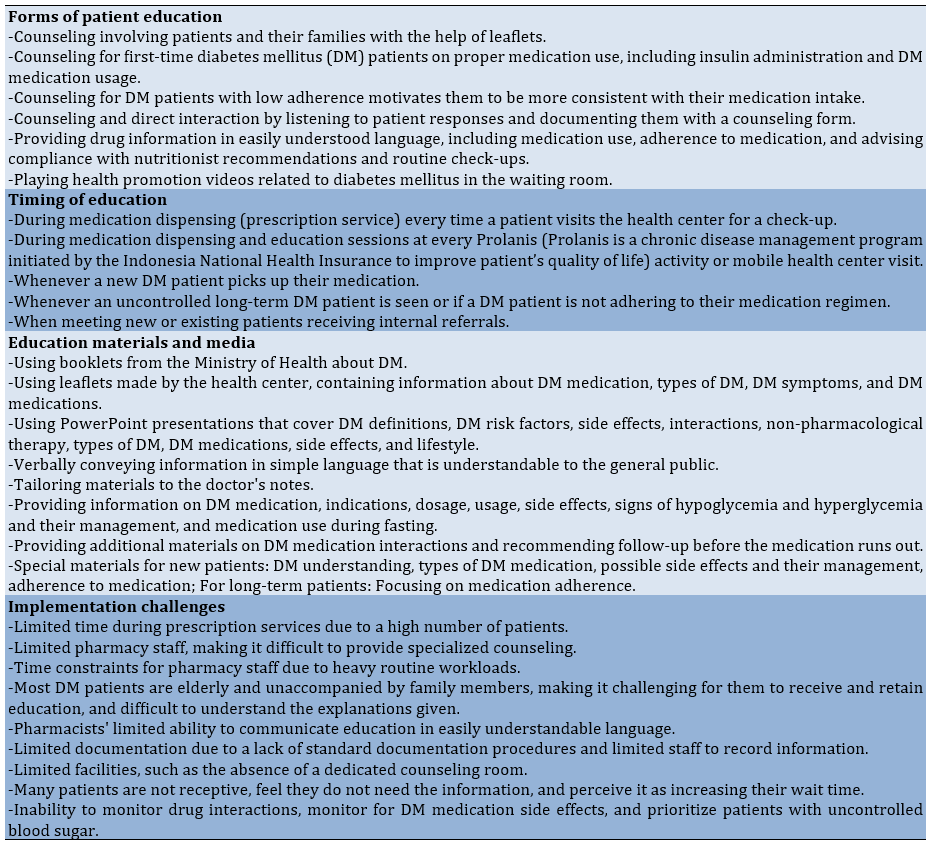

The education provided by pharmacists included various forms of counseling, drug information services, and playing videos in the health center’s waiting room. The timing of the education varied, occurring both when medication was dispensed and during educational sessions. The materials and media used for education also differed. Challenges in implementing education included limited time, staffing, pharmacist skills, and documentation (Table 5).

Table 5. Education provided by pharmacists at the health centers

Discussion

This study aimed to measure the knowledge level and information needs of patients with diabetes in Yogyakarta City, Indonesia. DM patients in Yogyakarta City had a moderate level of knowledge, a positive outcome attributed to essential information on diet, exercise, and treatments provided by doctors and pharmacists, with some patients also seeking information online [19]. The DKQ-24 revealed common misconceptions, such as the belief that exercise increases insulin requirements. Better-informed patients are more likely to follow recommended dietary, exercise, and medication guidelines [20]. Studies in Malaysia, Ethiopia, and Brazil show varying levels of diabetes knowledge and self-care [21-24]. A meta-analysis indicates mixed knowledge levels among Southeast Asian type 2 DM patients [25].

This study found no relationship between age, gender, occupation, income, education, and knowledge level, unlike some previous studies [22, 25-27]. However, there was a significant link between the duration of diabetes and knowledge, as complications often correlate with longer disease duration [22, 24, 25, 28, 29]. Additionally, no significant relationship was found between knowledge level and the number of DM medications, comorbidities, or blood sugar levels, similar to previous studies [29, 30].

The priority information needs were identified based on patient perceptions, where patients selected the information they deemed most important. Knowledge of DM therapy is influenced by the information patients receive. According to Crangle et al., DM management is highly complex and requires diverse information [12].

The top priorities included understanding DM risk factors, the side effects of DM medications, managing a healthy diet, and recognizing symptoms of complications. Many patients lack knowledge in these areas, including chronic complications such as nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy [21, 23, 31].

Despite variations in diabetes knowledge among type 2 DM patients in different studies, all recommend the need for more intensive and continuous health education programs to enhance understanding and improve disease management [20, 21, 23-25].

Pharmacists at community health centers provided education and counseling, although most lacked specialized training in diabetes management. Consequently, education was limited to new patients and those with uncontrolled blood sugar levels during center visits. Studies show that pharmacist-led education and counseling significantly improve clinical outcomes, patient knowledge, and adherence, and reduce complications [32-34].

Educational materials vary, with some sourced from the Ministry of Health and others from community centers, primarily focusing on diabetes and its treatment. These materials need to be updated and standardized for comprehensive reference in education and counseling programs.

Comprehensive educational programs covering diabetes management, medication use, diet, physical activity, self-monitoring, and ongoing counseling can help patients manage diabetes more effectively, reduce complications, and improve well-being [32-34].

Interventions, such as comprehensive medication management, patient education, pharmacist consultations, and health information technology have proven effective in improving patient safety, reducing adverse drug events, and lowering healthcare costs [35, 36].

Challenges for pharmacists included limited time, a lack of dedicated space, and the absence of standardized documentation. Policies are needed to address these issues and promote collaboration between pharmacists and other healthcare providers to deliver integrated and accessible primary care services. The involvement of pharmacists in primary care teams can improve patient outcomes, reduce hospitalization rates, better manage chronic conditions, and increase patient satisfaction [37, 38].

Elderly patients often lack accompanying family members, resulting in suboptimal education. Despite opportunities to provide information, pharmacists face rejection or resistance from patients. Based on this research, we recommend improving educational services through specialized training, updating materials, implementing standardized documentation, and collaborating with other professionals [4, 37].

Considering the challenges in implementing pharmacy services, this research recommends enhancing the quality of educational and counseling services by providing specialized training, updating educational materials to be more comprehensive, implementing standardized documentation forms, and collaborating with other healthcare professionals.

Educational strategies, including training, workshops, and materials, enhance the understanding and application of evidence-based practices. Training programs demonstrate high satisfaction, knowledge improvement, and positive attitudes toward evidence-based practices, preparing participants to adopt these practices and improve the quality of patient care [39].

Collaboration between pharmacists and other healthcare professionals is crucial for service quality, delivering integrated care, managing medications, monitoring side effects, ensuring adherence, and addressing medication-related issues [37, 38].

This study was limited to patients with DM who are registered at health centers in Yogyakarta City. Patients with DM who are not registered at any health centers in Yogyakarta City are underreported and need to be included in future studies.

Conclusion

DM patients in the Yogyakarta City have a moderate level of knowledge.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank all the patients and pharmacists for their participation in this research.

Ethical Permissions: Prior to commencing the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia, number KE/FK/1879/EC/2023. Before the data collection process, they received an explanation of the study. Patients who consented to participate signed the informed consent form and voluntarily filled out the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Munif Yasin N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Putri Ekasari M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Prabasworo W (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Arom S (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Ridhayani F (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (63.31.01/UN1/FFA/UP/SK/2023).

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a long-term chronic disease caused by elevated blood glucose levels due to insufficient insulin production or ineffective insulin usage. According to an International Diabetes Federation (IDF) report in 2021, this disease is directly responsible for 1.5 million deaths annually. Globally, about 422 million individuals suffer from DM, with the majority living in low- and middle-income nations, including Indonesia [1].

DM has a significantly high prevalence in Indonesia, and its incidence continues to rise annually. Indonesia ranks among the top seven nations worldwide in terms of diabetes prevalence [1]. Based on data from the Indonesia Basic Health Research from 2013 to 2018, the proportion of diabetes prevalence in Indonesia increased from 6.9% to 8.5%. Among the 38 provinces in Indonesia, Yogyakarta Special Region (DIY) Province ranks second nationally. The prevalence of individuals diagnosed with DM in Yogyakarta City is 4.79%, which corresponds to approximately 15,540 individuals [1, 2]. Considering the significant rise in DM cases in Indonesia, healthcare providers and patients must have a sufficient understanding of DM to effectively manage and treat the disease and its complications [3, 4].

The patient’s understanding of DM enables them to independently implement an appropriate treatment regimen throughout their lifetime. DM is a multifaceted condition; therefore, patients with DM have specific information needs that differ from one another [5]. The patients’ needs for information on all diabetes-related topics vary among subgroups affected by factors such as age, level of education, types, and duration of diabetes, comorbid conditions, level of diabetes knowledge, gender-related factors, and changes in information needs along the disease’s progression [6, 7].

The quality and advancement of health systems also affect the variance in information needs among diabetic patients [8, 9]. Several studies have revealed distinct needs for diabetes-related information among Asians and Europeans [8, 10, 11]. However, there have been a limited number of studies conducted in Indonesia, specifically in Yogyakarta, focusing on patients’ perspectives regarding DM information needs [12].

On the other hand, the role of pharmacists in community health centers in providing pharmaceutical services has not yet been optimized. The high workload experienced by pharmacists is evident, often due to understaffing and the need to handle numerous administrative and technical tasks. Pharmacists’ responsibilities include counseling and monitoring. Therefore, integrating pharmacists into the primary health care system and recognizing their significant contribution to improving the quality of health services is greatly needed [13]. Consequently, a study in Yogyakarta City is necessary to gain a better understanding of the current conditions, specifically mapping the prioritization of patient needs and preferences, as well as the types of patient service strategies applied by pharmacists. This will allow for the development and accurate implementation of further strategies to enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Therefore, this study aimed to measure the knowledge level and information needs of patients with DM in Yogyakarta and develop an appropriate strategy to address this issue.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted on patients with DM referring to health centers in Yogyakarta City between January and May 2024. Yogyakarta City has 18 health centers. Eight health centers were selected from these 18 because they have the highest number of diabetic patients. From those eight health centers, we invited registered patients with type 2 DM who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria using an accidental sampling approach. A sample size of 155 patients was determined based on the Slovin formula considering a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a 5% margin of error. We received completed questionnaires with a 100% response rate. After gathering the patients’ data, a follow-up survey was conducted. Of all the pharmacists working at community health centers in Yogyakarta, 16 participated in this study.

Research tools

We used a questionnaire for the patients and a survey form for the pharmacists.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections, including the demographic information chalkiest, the 24-item version of the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ-24), and the researcher-made Diabetes Mellitus Information Questionnaire.

The first section required respondents to provide personal information, such as their age, gender, education level, employment, income, time since DM diagnosis, comorbidities, medications, and blood sugar levels. Then, the DKQ-24 questionnaire was used as a specific standardized instrument to measure the knowledge of patients with DM. We utilized the Indonesian-translated version of the DKQ-24 developed and approved (Cronbach’s α=0.757) by Zakiudin et al. [14]. Each respondent answered 24 questions by choosing one of three responses, namely yes, no, or I do not know. The items were scored as either correct or incorrect. The total number of correct answers was summed, with a higher score indicating better knowledge of DM. We classified the level of patient knowledge into three groups based on their final score; low (score: 0-9), medium (10-16), and high (17-24) [15].

Further, the researcher-made Diabetes Mellitus Information Questionnaire was used to assess the types of information needs by patients and measure the priority of each type of information related to DM. We conducted a literature review to formulate the questions [16]. The measurement of content validity, face validity, and reliability was applied [17]. Three experts and 30 respondents were involved to confirm that this questionnaire was valid. A reliability coefficient of 0.914 was attained using Cronbach’s Alpha. In this final section, respondents were required to answer 21 yes/no questions, which were divided into four domains, including medication, disease, lifestyle, and complications. They were then asked to rank these from most priority to least priority.

We also used a survey form to assess pharmacists’ information. The survey form included two sections, including demographic characteristics and types of pharmacy services in their workplace. The first section included age, gender, level of education, capacity, and duration of practice. The next part consisted of open-ended questions related to pharmacy services, covering the forms of patient education, timing of education, educational materials and media, as well as topics related to implementation challenges. This study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklists [18]. For calculating item difficulty index, we used the formula P=R/T, where P is the item difficulty index, R is the number of correct responses, and T is the total number of responses.

Data analysis

The demographic data of patients with type 2 DM were analyzed using descriptive statistics. We used SPSS version 22 to analyze the data using chi-square test. Moreover, the demographic data of pharmacists were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The results are presented as frequencies, percentages, and detailed descriptions.

Findings

Out of 155 patients with DM, the majority were females, and the age group of 55-64 accounted for almost half of the subjects. Based on educational characteristics, most patients had a junior high school level of education. The majority of the patient participants were unemployed, and half of them had no monthly income. Among all patient participants, nearly half were diagnosed with DM within the past five years, more than half were on single treatment with either an oral antidiabetic drug or insulin, only a quarter of the participants were free from comorbidities, and most were in poor condition with high levels of fasting glucose (Table 1).

The level of knowledge among DM patients at the Yogyakarta City Health Center fell into the moderate category (80%), with a total of 124 patients. The mean level of knowledge according to the DKQ-24 was 12.70±2.91. Only the time since DM diagnosis was associated with patients’ knowledge level (p=0.015). Furthermore, the other characteristics did not have a significant association with the knowledge level (p>0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of patients with diabetes mellitus (n=155)

The three items with the most correct responses were items 18, 5, and 8, which addressed food preparation, diabetes conditions without treatment, and the results of fasting glucose level measurement. According to the four key domains, the participants’ responses exhibited distinct item difficulty indices for each question, varying between 0.12 and 0.91. Specifically, item 10 had the highest difficulty score, followed by items 1 and 12, which examined the impact of regular physical examinations on insulin requirements, the consumption of sugar and sweet foods as a cause of DM, and the reasons for insulin reactions (Table 2).

Table 2. Item difficulty of each item in the 24-Item Version of the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (n=155)

Patients who need information regarding disease, treatment, lifestyle, and complications exhibited moderate knowledge (Table 3).

Table 3. Categories of information needs among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM)

The majority of the pharmacists were women, aged 31-45 years. Only two pharmacists held a master’s degree, and almost half had more than ten years of practical experience. A total of 68.75% reported attending training, but only 12.50% reported participating in specialized training related to DM. Other training attended by the pharmacists included pharmaceutical services for health center pharmacy staff, pharmacovigilance, pharmaceutical management, clinical pharmacy, preceptor training, and specialized tuberculosis training (Table 4).

Table 4. Demographic characteristics of pharmacists (n=16)

The types of services provided by all pharmacists included prescription review and services, as well as education, which encompassed providing drug information and counseling. Other services included monitoring adverse drug reactions (43.75%), drug therapy monitoring (25.00%), and health promotion (12.50%).

The education provided by pharmacists included various forms of counseling, drug information services, and playing videos in the health center’s waiting room. The timing of the education varied, occurring both when medication was dispensed and during educational sessions. The materials and media used for education also differed. Challenges in implementing education included limited time, staffing, pharmacist skills, and documentation (Table 5).

Table 5. Education provided by pharmacists at the health centers

Discussion

This study aimed to measure the knowledge level and information needs of patients with diabetes in Yogyakarta City, Indonesia. DM patients in Yogyakarta City had a moderate level of knowledge, a positive outcome attributed to essential information on diet, exercise, and treatments provided by doctors and pharmacists, with some patients also seeking information online [19]. The DKQ-24 revealed common misconceptions, such as the belief that exercise increases insulin requirements. Better-informed patients are more likely to follow recommended dietary, exercise, and medication guidelines [20]. Studies in Malaysia, Ethiopia, and Brazil show varying levels of diabetes knowledge and self-care [21-24]. A meta-analysis indicates mixed knowledge levels among Southeast Asian type 2 DM patients [25].

This study found no relationship between age, gender, occupation, income, education, and knowledge level, unlike some previous studies [22, 25-27]. However, there was a significant link between the duration of diabetes and knowledge, as complications often correlate with longer disease duration [22, 24, 25, 28, 29]. Additionally, no significant relationship was found between knowledge level and the number of DM medications, comorbidities, or blood sugar levels, similar to previous studies [29, 30].

The priority information needs were identified based on patient perceptions, where patients selected the information they deemed most important. Knowledge of DM therapy is influenced by the information patients receive. According to Crangle et al., DM management is highly complex and requires diverse information [12].

The top priorities included understanding DM risk factors, the side effects of DM medications, managing a healthy diet, and recognizing symptoms of complications. Many patients lack knowledge in these areas, including chronic complications such as nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy [21, 23, 31].

Despite variations in diabetes knowledge among type 2 DM patients in different studies, all recommend the need for more intensive and continuous health education programs to enhance understanding and improve disease management [20, 21, 23-25].

Pharmacists at community health centers provided education and counseling, although most lacked specialized training in diabetes management. Consequently, education was limited to new patients and those with uncontrolled blood sugar levels during center visits. Studies show that pharmacist-led education and counseling significantly improve clinical outcomes, patient knowledge, and adherence, and reduce complications [32-34].

Educational materials vary, with some sourced from the Ministry of Health and others from community centers, primarily focusing on diabetes and its treatment. These materials need to be updated and standardized for comprehensive reference in education and counseling programs.

Comprehensive educational programs covering diabetes management, medication use, diet, physical activity, self-monitoring, and ongoing counseling can help patients manage diabetes more effectively, reduce complications, and improve well-being [32-34].

Interventions, such as comprehensive medication management, patient education, pharmacist consultations, and health information technology have proven effective in improving patient safety, reducing adverse drug events, and lowering healthcare costs [35, 36].

Challenges for pharmacists included limited time, a lack of dedicated space, and the absence of standardized documentation. Policies are needed to address these issues and promote collaboration between pharmacists and other healthcare providers to deliver integrated and accessible primary care services. The involvement of pharmacists in primary care teams can improve patient outcomes, reduce hospitalization rates, better manage chronic conditions, and increase patient satisfaction [37, 38].

Elderly patients often lack accompanying family members, resulting in suboptimal education. Despite opportunities to provide information, pharmacists face rejection or resistance from patients. Based on this research, we recommend improving educational services through specialized training, updating materials, implementing standardized documentation, and collaborating with other professionals [4, 37].

Considering the challenges in implementing pharmacy services, this research recommends enhancing the quality of educational and counseling services by providing specialized training, updating educational materials to be more comprehensive, implementing standardized documentation forms, and collaborating with other healthcare professionals.

Educational strategies, including training, workshops, and materials, enhance the understanding and application of evidence-based practices. Training programs demonstrate high satisfaction, knowledge improvement, and positive attitudes toward evidence-based practices, preparing participants to adopt these practices and improve the quality of patient care [39].

Collaboration between pharmacists and other healthcare professionals is crucial for service quality, delivering integrated care, managing medications, monitoring side effects, ensuring adherence, and addressing medication-related issues [37, 38].

This study was limited to patients with DM who are registered at health centers in Yogyakarta City. Patients with DM who are not registered at any health centers in Yogyakarta City are underreported and need to be included in future studies.

Conclusion

DM patients in the Yogyakarta City have a moderate level of knowledge.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank all the patients and pharmacists for their participation in this research.

Ethical Permissions: Prior to commencing the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia, number KE/FK/1879/EC/2023. Before the data collection process, they received an explanation of the study. Patients who consented to participate signed the informed consent form and voluntarily filled out the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Munif Yasin N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Putri Ekasari M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%); Prabasworo W (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Arom S (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Ridhayani F (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (63.31.01/UN1/FFA/UP/SK/2023).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2024/06/27 | Accepted: 2024/08/18 | Published: 2024/09/30

Received: 2024/06/27 | Accepted: 2024/08/18 | Published: 2024/09/30

References

1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edition [Internet]. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2021 [cited 2023 Jun 4]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/. [Link]

2. Yogyakarta Health Office. Health profile of Yogyakarta in 2021. Yogyakarta: Yogyakarta Health Office; 2021. [Indonesian] [Link]

3. Wibowo Y, Parsons R, Sunderland B, Hughes J. Evaluation of community pharmacy-based services for type-2 diabetes in an Indonesian setting: Pharmacist survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):873-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11096-015-0135-y]

4. Yuniar Y, Herman MJ. Overcoming shortage of pharmacists to provide pharmaceutical services in public health centers in Indonesia. Kesmas. 2013;8(1):3-8. [Link] [DOI:10.21109/kesmas.v8i1.334]

5. Pemayun TDA. Description of the level of knowledge regarding the management of diabetes mellitus in diabetes mellitus patients at Sanglah Hospital. Jurnal Medika Udayana. 2020;9(8):1-4. [Indonesian] [Link]

6. Biernatzki L, Kuske S, Genz J, Ritschel M, Stephan A, Bachle C, et al. Information needs in people with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):27. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13643-018-0690-0]

7. Borgmann SO, Gontscharuk V, Sommer J, Laxy M, Ernstmann N, Karl FM, et al. Different information needs in subgroups of people with diabetes mellitus: A latent class analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1901. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-09968-9]

8. Bosch-Frigola I, Coca-Villalba F, Perez-Lacasta MJ, Carles-Lavila M. European national health plans and the monitoring of online searches for information on diabetes mellitus in different European healthcare systems. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1023404. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1023404]

9. Clarke MA, Moore JL, Steege LM, Koopman RJ, Belden JL, Canfield SM, et al. Health information needs, sources, and barriers of primary care patients to achieve patient-centered care: A literature review. Health Informatics J. 2016;22(4):992-1016. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1460458215602939]

10. Grobosch S, Kuske S, Linnenkamp U, Ernstmann N, Stephan A, Genz J, et al. What information needs do people with recently diagnosed diabetes mellitus have and what are the associated factors? A cross-sectional study in Germany. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e017895. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017895]

11. Kanan P, Siribumrungwong B, Tharavanij T, Orrapin S, Napunnaphat P. The needs of patients with diabetes for the prevention and treatment of foot complications in Thailand: A qualitative descriptive study. Belitung Nurs J. 2023;9(6):586-94. [Link] [DOI:10.33546/bnj.2835]

12. Crangle CE, Bradley C, Carlin PF, Esterhay RJ, Harper R, Kearney PM, et al. Exploring patient information needs in type 2 diabetes: A cross sectional study of questions. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0203429. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0203429]

13. Hermansyah A, Wulandari L, Kristina SA, Meilianti S. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Indonesia. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(3):2085. [Link] [DOI:10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2085]

14. Zakiudin A, Irianto G, Badrujamaludin A, Rumahorbo H, Susilawati S. Validation of the diabetes knowledge questionnaire (DKQ) with an Indonesian population. Knowl E Med. 2022;2022:99-108. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/kme.v2i2.11072]

15. Garcia AA, Villagomez ET, Brown SA, Kouzekanani K, Hanis CL. The Starr County diabetes education study: Development of the Spanish-language diabetes knowledge questionnaire. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(1):16-21. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/diacare.24.1.16]

16. Fenwick EK, Xie J, Rees G, Finger RP, Lamoureux EL. Factors associated with knowledge of diabetes in patients with type 2 diabetes using the Diabetes Knowledge Test validated with Rasch analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80593. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0080593]

17. Taherdoost H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; How to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. Int J Acad Res Manag. 2016;5(3):28-36. [Link] [DOI:10.2139/ssrn.3205040]

18. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD]

19. Prabasworo W, Yasin NM. Analysis of the level of knowledge and information needs of diabetes mellitus patients at the Southern Yogyakarta City Health Center [Thesis]. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University; 2024. [Indonesian] [Link]

20. Stark Casagrande S, Rios Burrows N, Geiss LS, Bainbridge KE, Fradkin JE, Cowie CC. Diabetes knowledge and its relationship with achieving treatment recommendations in a national sample of people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1556-65. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc11-1943]

21. Kifle ZD, Adugna M, Awgichew A, Chanie A, Sewnet G, Asrie AB. Knowledge towards diabetes and its chronic complications and associated factors among diabetes patients in University of Gondar comprehensive and specialized hospital, Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022;15:101033. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2022.101033]

22. Moraes N, Souza G, Brito F, Antonio Júnior M, Cipriano A, Costa N, et al. Knowledge and self-care in diabetes mellitus and their correlations with sociodemographic, clinical and treatment variables. Diabetes Updates. 2020;6(2):3-6. [Link] [DOI:10.15761/DU.1000145]

23. De Oliveira KC, Zanetti ML. Knowledge and attitudes of patients with diabetes mellitus in a primary health care system. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2011;45(4):862-8. [Portuguese] [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0080-62342011000400010]

24. Lai PK, Teng CL, Mustapha FI. Diabetes knowledge among Malaysian adults: A scoping review and meta-analysis. Malays Fam Physician. 2024;19:26. [Link] [DOI:10.51866/rv.304]

25. Lim PC, Rajah R, Lee CY, Wong TY, Tan SSA, Karim SA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diabetes knowledge among type 2 diabetes patients in Southeast Asia. Rev Diabet Stud. 2021;17(2):82-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1900/RDS.2021.17.82]

26. Luambano C, Mwinuka B, Ibrahim RP, Kacholi G. Knowledge about diabetes mellitus and its associated factors among diabetic outpatients at Muhimbili National Hospital in Tanzania. Pan Afr Med J. 2023;45:3. [Link] [DOI:10.11604/pamj.2023.45.3.33143]

27. Phoosuwan N, Ongarj P, Hjelm K. Knowledge on diabetes and its related factors among the people with type 2 diabetes in Thailand: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2365. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-14831-0]

28. Almousa AY, Hakami OA, Qutob RA, Alghamdi AH, Alaryni AA, Alammari YM, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward diabetes mellitus and their association with socioeconomic status among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39641. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.39641]

29. Yasin NM, Syafitri IW, Sari IP. The relationship of knowledge and compliance levels with clinical outcomes for diabetes mellitus patients through the brief counseling method at public health centers in Pemalang regency. Majalah Farmaseutik. 2022;18(4):475-82. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.22146/farmaseutik.v18i4.74919]

30. Phillips E, Rahman R, Mattfeldt-Beman M. Relationship between diabetes knowledge, glycemic control, and associated health conditions. Diabetes Spectr. 2018;31(2):196-9. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/ds17-0058]

31. Afaya RA, Bam V, Azongo TB, Afaya A. Knowledge of chronic complications of diabetes among persons living with type 2 diabetes mellitus in northern Ghana. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0241424. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0241424]

32. Ojieabu W, Bello S, Arute J. Evaluation of pharmacists' educational and counseling impact on patients' clinical outcomes in a diabetic setting. J Diabetol. 2017;8(1):7-11. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jod.jod_5_17]

33. Thanh HTK, Tien TM. Effect of group patient education on glycemic control among people living with type 2 diabetes in Vietnam: A randomized controlled single-center trial. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12(5):1503-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13300-021-01052-8]

34. Venkatesan R, Devi AS, Parasuraman S, Sriram S. Role of community pharmacists in improving knowledge and glycemic control of type 2 diabetes. Perspect Clin Res. 2012;3(1):26-31. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2229-3485.92304]

35. Jaam M, Naseralallah LM, Hussain TA, Pawluk SA. Pharmacist-led educational interventions provided to healthcare providers to reduce medication errors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253588. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0253588]

36. Royal S, Smeaton L, Avery AJ, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A. Interventions in primary care to reduce medication related adverse events and hospital admissions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(1):23-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/qshc.2004.012153]

37. Ballantyne PJ. The role of pharmacists in primary care. BMJ. 2007;334(7603):1066-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.39213.660394.80]

38. Dodd MA, Haines SL, Maack B, Rosselli JL, Sandusky JC, Scott MA, et al. ASHP statement on the role of pharmacists in primary care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79(22):2070-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ajhp/zxac227]

39. Watson MC, Bond CM, Grimshaw JM, Mollison J, Ludbrook A. Educational strategies to promote evidence-based community pharmacy practice: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Pharm Pract. 2001;9(Suppl 1):12. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.2042-7174.2001.tb01072.x]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |