Volume 12, Issue 3 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(3): 423-430 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sarhadi M, Mazloom S. Death Anxiety in Nursing Students. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (3) :423-430

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-75419-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-75419-en.html

M. Sarhadi *1, S. Mazloom2

1- “Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery” and “Community Nursing Research Center”, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Zahedan branch, Islamic Azad University, Zahedan, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Zahedan branch, Islamic Azad University, Zahedan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 583 kb]

(1383 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (596 Views)

Full-Text: (59 Views)

Introduction

Death is a natural and inevitable part of the life cycle [1] and a biological event that signifies the permanent cessation of vital signs and functions of the heart [2]. With the occurrence of death, a process that we call life ends logically and definitively, revealing its entirety and totality [3]. However, contemplating death can be frightening, and most people prefer not to think about it [4, 5] because, despite technological advances, it serves as a reminder of human vulnerability. Thus, fear of death, or death anxiety, is an unpleasant and common human experience [6] and one of the fundamental factors underlying all human anxieties [7].

According to the British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), death anxiety is a feeling of panic, fear, or anxiety when contemplating the process of dying, losing one’s connection with the world, or what happens after death. This type of anxiety encompasses motivational, cognitive, and emotional components and changes under the influence of developmental stages and events in social and cultural life [8, 9]. Existential theorists also believe that death anxiety is a generalized fear and disorder caused by existential anxiety. They suggest that we experience existential anxiety because we are aware that our lives are limited and fear the death that awaits us [10]. According to Choron, there are three types of death anxiety, including anxiety caused after death, anxiety caused during death, and anxiety caused by a feeling of nothingness and destruction. He considers the first two types to be related to the physical process of death, while he regards the third type of anxiety as the most significant concern of human existence [11]. However, since every human ultimately faces the event of death, one’s attitude toward it is one of the most important factors that affect behavior related to healthcare professions [12].

This is particularly relevant since the confrontation with death has been reported as one of the most distinct experiences during the clinical education of nursing students, making adaptability to the pain and suffering of patients difficult for them [7]. Accordingly, studies have shown that most students are concerned about their lack of ability to adapt to these situations [13]. They attempt to cope with death but are not emotionally ready to care for dying patients, as such emotional reactions can limit their professional capacity to provide care [14]. Thus, it is essential to shed light on students’ experiences of death, as well as their involvement in end-of-life patient care [14]. This knowledge can help nurses understand and prepare for the care of any individual who faces the challenging moments of their own death or the death of others [15]. Therefore, since death is an important and significant event in nursing practice, exploring individuals’ attitudes toward death and dying should begin during academic studies. Moreover, examining the experiences of nursing students in relation to their social and cultural context may affect their coping abilities and skills.

Accordingly, since nursing students should take responsibility for the care of dying patients and their families during their studies and afterward, more effective methods must be employed to explain nursing students’ experiences. Thus, qualitative research can help achieve this goal. To this end, the present study aimed to explore death anxiety in nursing students using a qualitative (content analysis) method.

Participants and Methods

The present study was conducted using a conventional content analysis qualitative approach on participants selected through purposive sampling from nursing students at the School of Nursing and Midwifery in Zahedan in 2023-2024. These individuals were selected from among those who had completed one year of education, had a history of completing an internship, had experience in caring for patients in the final stages, had experience in the emergency room, and had experience with the death of a patient. A total of 12 participants, with an average age of 21 years, were interviewed over two months. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews. After obtaining the necessary legal permits and explaining the objectives of the study to the participants, the interviews were conducted as two-way conversations.

Following the main research question, the interviews began with open-ended questions: “Could you talk about your experiences with death?” and “When you think about death, what comes to your mind?” Subsequent questions were then asked based on the participants’ responses and aimed to enrich the data. Furthermore, probing questions (e.g., “Could you explain more about it?” and “What do you mean by …?”) were posed for further clarification and to elicit additional information. At the end of the interviews, participants were asked if they had any other comments to add to their statements. Depending on the time available, the collected data, the participants’ conditions, and their willingness, each interview was conducted in one or more sessions. All interviews were recorded after obtaining the participants’ oral consent and transcribed word for word within 24 hours. The duration of each interview was approximately 40 minutes.

The data were analyzed simultaneously with data collection using the five-step qualitative content analysis method (Graneheim & Lundman). The steps were transcribing the content of each interview immediately, reading each transcript several times to develop a general understanding of its content, identifying meaning units and primary codes, classifying similar codes into more comprehensive clusters, and extracting the themes hidden in the data [16].

To this end, after completing each interview, its content was transcribed immediately. The transcripts were then read several times, and the primary codes were extracted. Afterward, related codes were merged into a single category based on their similarities. Finally, the themes hidden in the data were identified and extracted. During the analysis, many of the codes were revised multiple times, and the extracted categories were also named. Memos were used to thoroughly identify the codes and enhance the efficacy of the data analysis process [17, 18].

The four criteria proposed by Lincoln & Guba were used to ensure data trustworthiness, including credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability [19].

The researchers employed specific qualitative research methods, such as ongoing engagement with the subjects and data, as well as member checks, to ensure the credibility of the data. The codes were adjusted in case of disagreement with the opinions of the participants. Additionally, the researchers utilized a combination of researchers, continuous data comparison, code review, and sampling with a diverse range of participants.

For dependability, an external observer reviewed the codes and themes identified in this study (external check, peer check) to enhance their rigor, ensuring that any existing contradictions and defects were addressed and corrected to reach a consensus. All activities were recorded, and a report on the research process was prepared for conformability. The findings were also shared with two patients and two spouses of patients who were not participants in the study but had similar conditions to those of the participants, and they approved the data.

Furthermore, the confidentiality of all interviews and the freedom of individuals to withdraw from the research were maintained. It should be noted that the data were analyzed using MAXQDA2020 software.

Findings

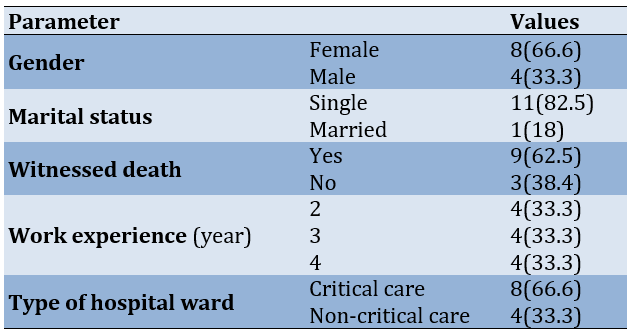

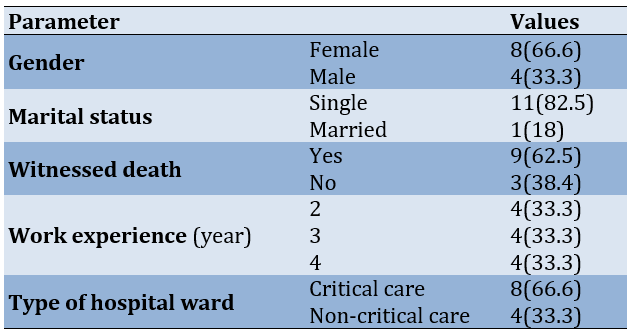

The participants consisted of 12 nursing students, including four sophomores, four juniors, and four seniors, all of whom had experienced the death of their relatives or patients in the ward. The age of the participants ranged from 19 to 25 years, with a mean age of 21.17±1.07 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of nursing students

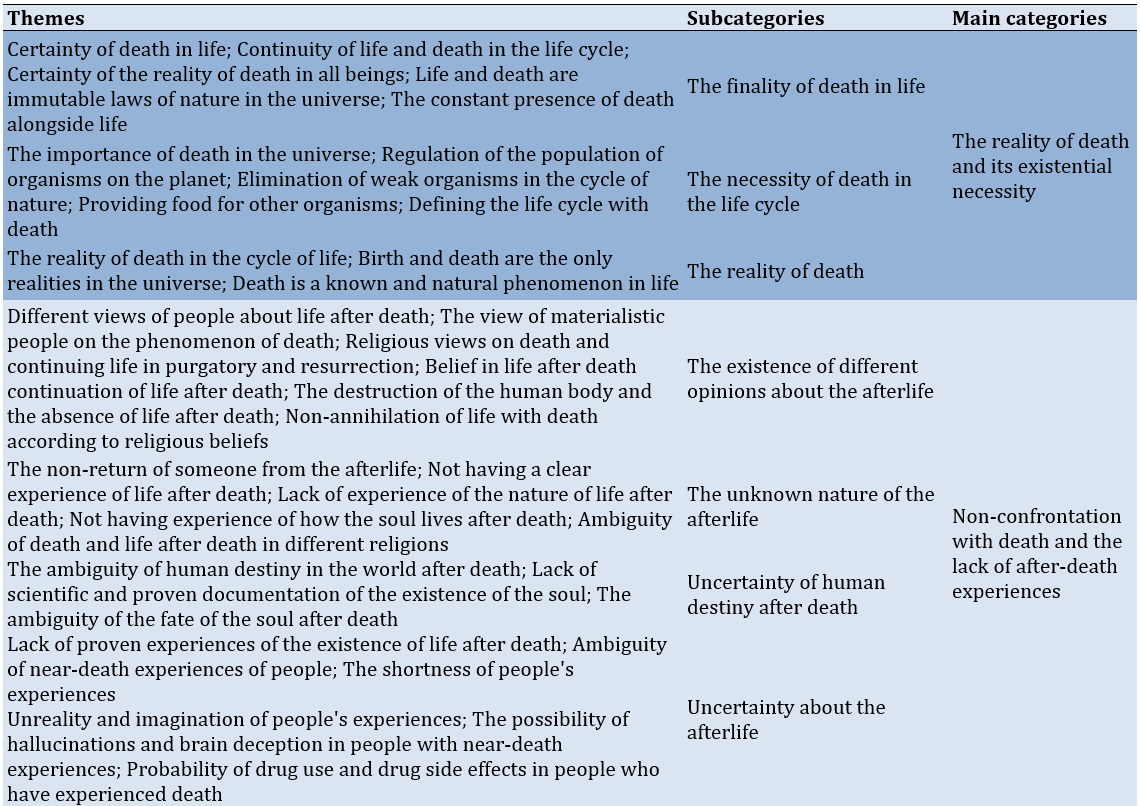

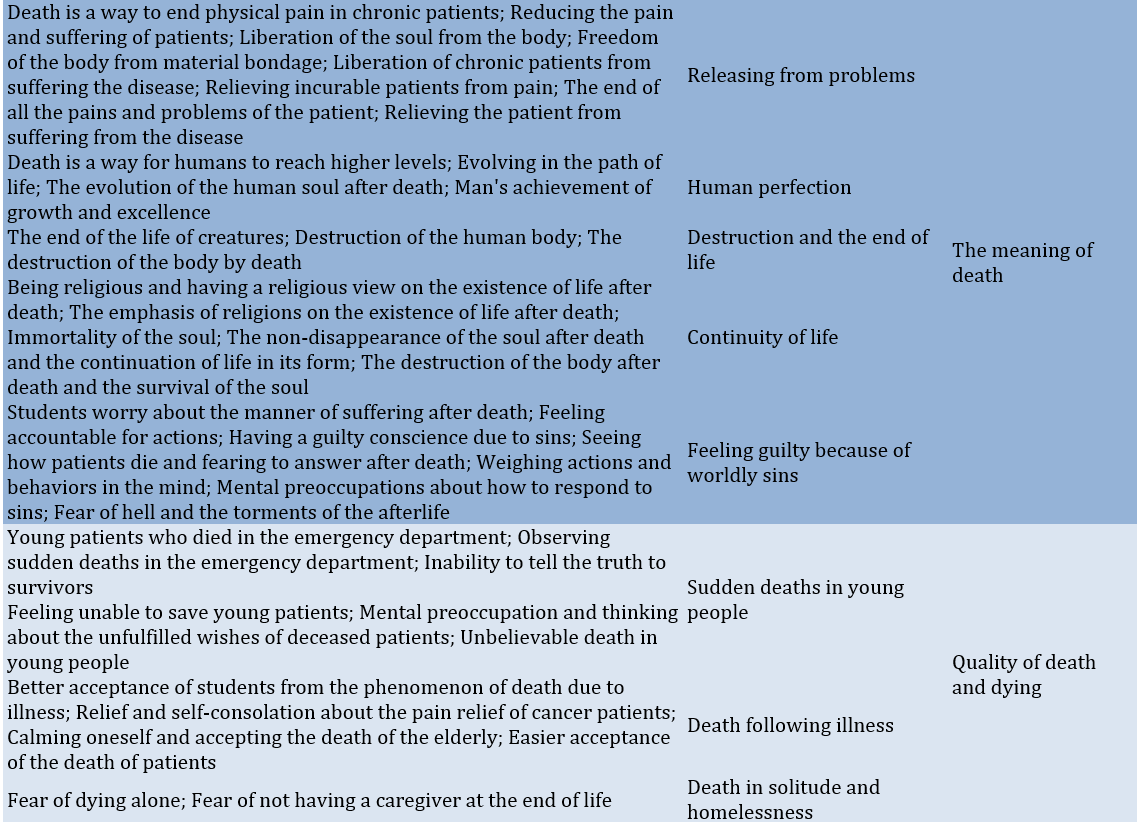

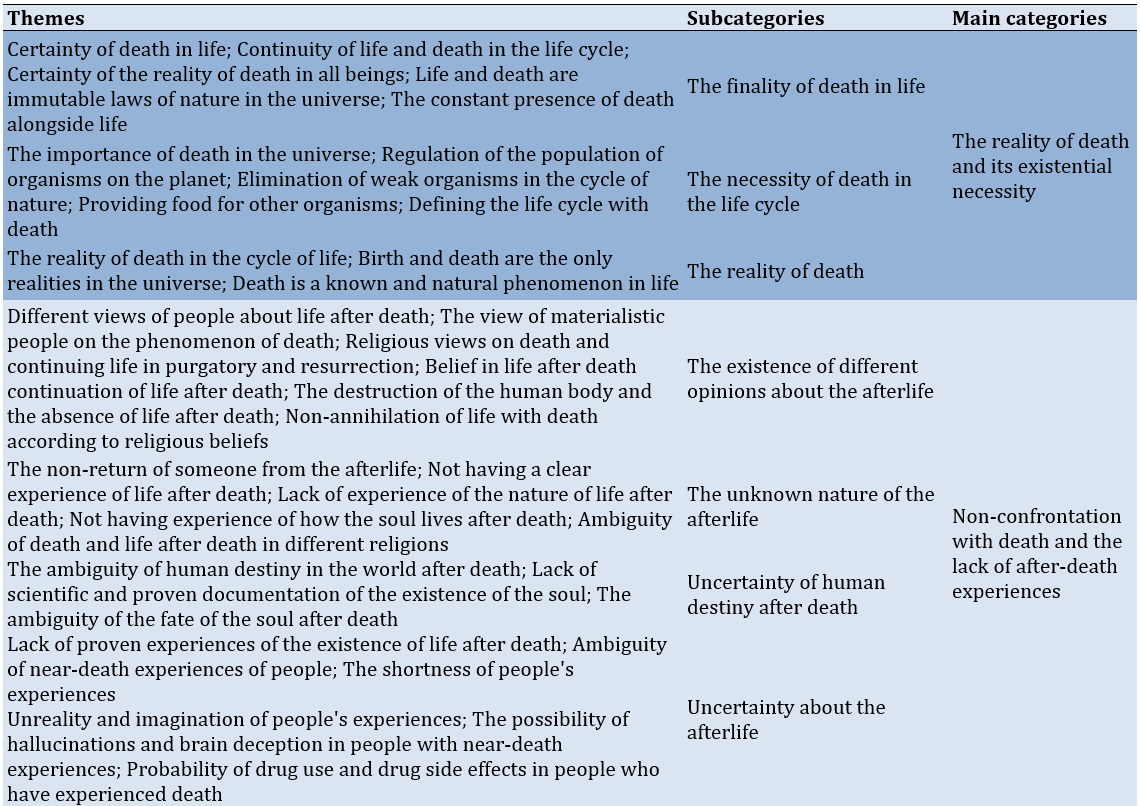

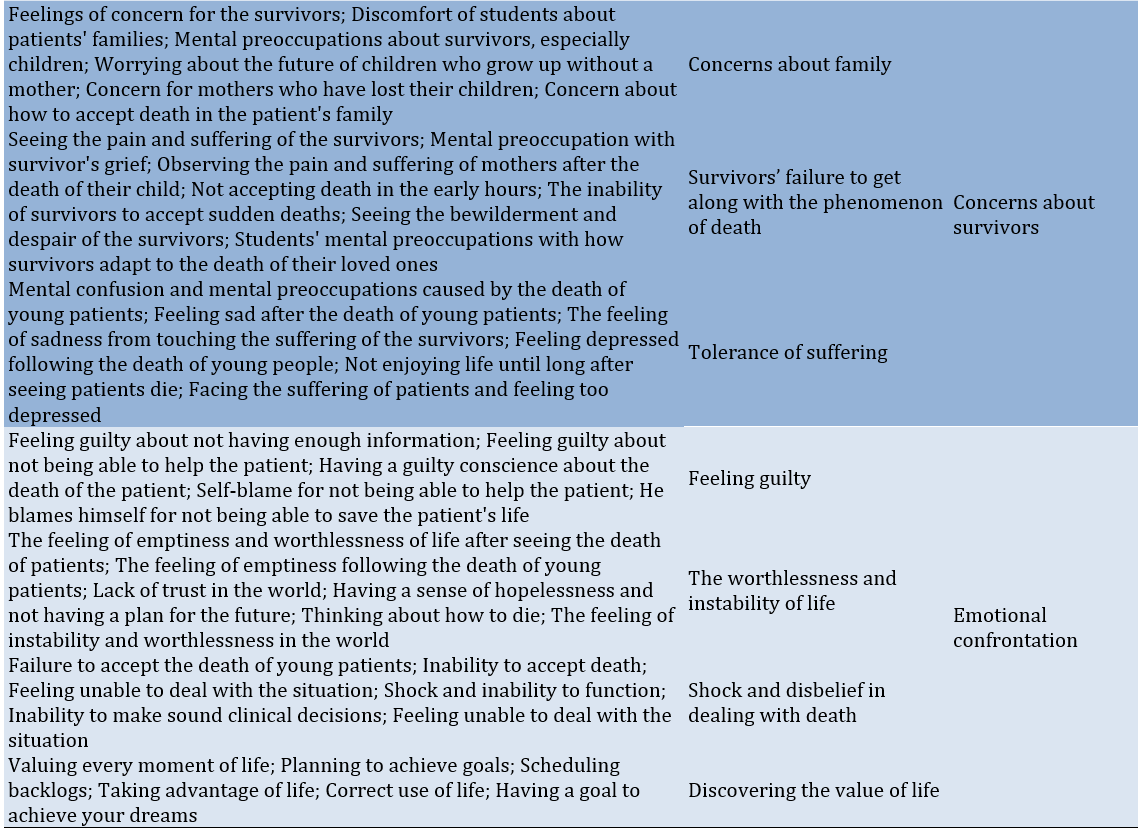

After data analysis, 114 themes were extracted and organized into six main categories and 22 subcategories (Table 2).

Table 2. The main categories and subcategories of death anxiety in nursing students

The reality of death and its existential necessity

The participants acknowledged the finality and reality of death. They regarded death as something inevitable and recognized that they would confront it sooner or later: “Death is a reality, whether like it or not. In fact, it is part of life. It finds meaning in the cycle of life, and life is meaningless without death. Thus, as a human, we know that we will die at the end and we should accept it, but no one knows who the hereafter looks like” (Participant #3).

Non-confrontation with death and the lack of after-death experiences

The participants also highlighted the unknown nature and uncertainty of fate after death. They viewed death as a definite and inevitable phenomenon that will happen to anyone. However, beneath the surface of their words and expressions, there was a notable tendency to resist accepting death and the concept of an afterlife. For instance, one of the participants stated, “I think since you don’t know the hereafter and have no idea of what is going to happen there for you, you cannot decide what is true or wrong about it, and if you have to believe it or not. And, this makes you anxious. Because there are a lot of conflicting ideas about the world after death and you cannot find out which one is right or wrong” (Participant #1). Another participant stated, “Everyone says there is a world but they cannot say what kind of world it is” (Participant #1). One of the participants stated, “I have witnessed the death of patients several times during my internship course. I always wonder if there is really another world, nobody has returned from it to confirm its existence and no one has ever experienced it” (Participant #8).

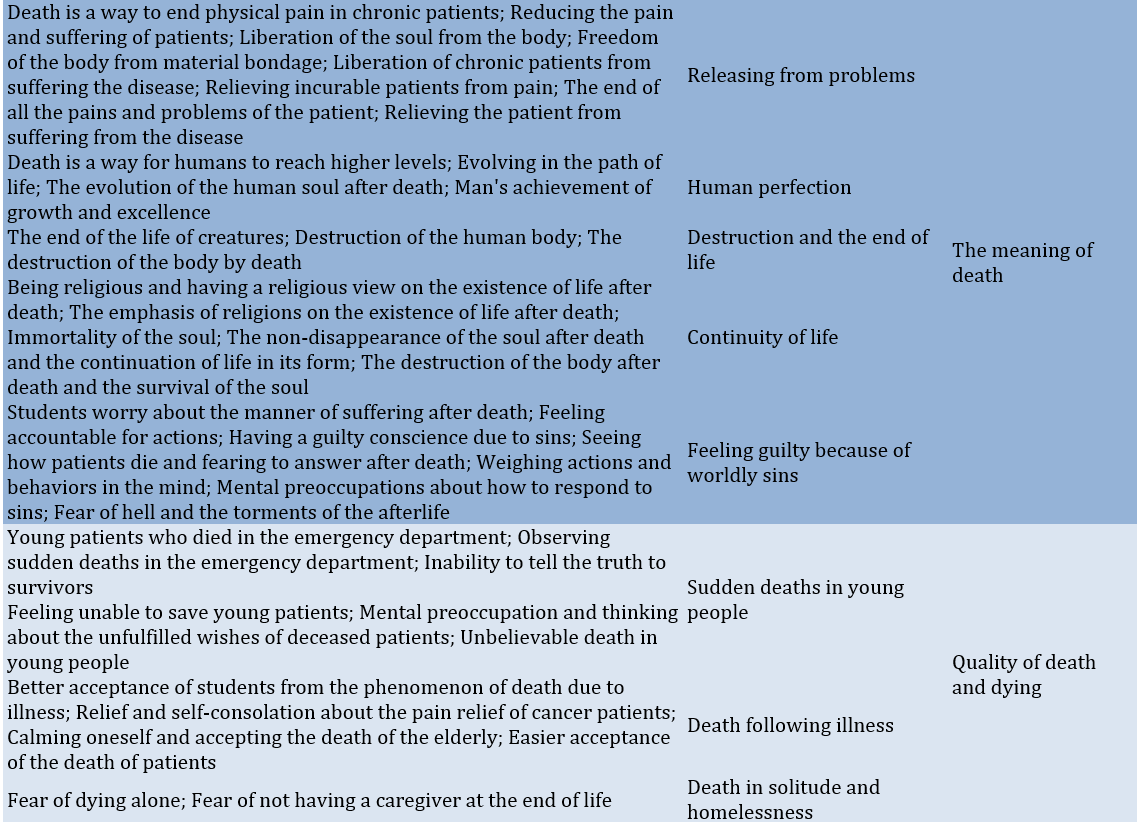

The meaning of death

The nursing students held different views about the meaning of death, influenced by their individual circumstances and religious beliefs. Some participants regarded death as an evolutionary stage and a transition to higher realms. Others perceived it as a representation of human mortality and the end of life. Additionally, some participants viewed it as a form of liberation and a release from life’s problems, while others equated it directly with life: “In my opinion, death is like a wall that you can go through its other side but you cannot get back to the opposite side. I think a person forgets those moments like the moment of his/her birth. A person who is born can never go back to the womb. It’s impossible. Thus, a person who is going through evolution must go to the next stage” (Participant #4).

Some of the nursing students also interpreted the meaning of death according to their religious beliefs: “The meaning of death depends on a person’s religion. For example, our religion says if you commit sins, you’ll go to hell and you will be reckoned and punished in the hereafter for even a small sin committed in this world. Thus, you are afraid of being punished in the hereafter. Religion is always inducing fear in you. You aren’t sure. The religious instructions are more stressful than pacifying and make you afraid of dying” (Participant #1).

The quality of death and dying

According to the participants, although death was a necessity, the quality of death was also effective in death anxiety. They believed that although the death of the patient and disabled person who had a chronic illness brings a sense of comfort and relief for both patient and family members, sudden, unusual deaths and thinking of them cause severe fear and anxiety: “In my opinion, dying in a car accident is very horrible. It’s very terrible thinking that your body is crushed in the middle of the pieces of a car and that the pain that a person suffers until he/she dies” (Participant #12). Another participant stated, “Well, in my opinion, death is a good blessing when a person gets very old and disabled and he/she becomes dependent on other people for doing even the smallest things. In the beginning, maybe everyone will try to help, but it is not practical. Even the patient gets in trouble. For example, when my grandmother died after having been severely disabled, I felt that she was relieved. Because I always heard she was praying to God and asking for a death with dignity” (Participant #7).

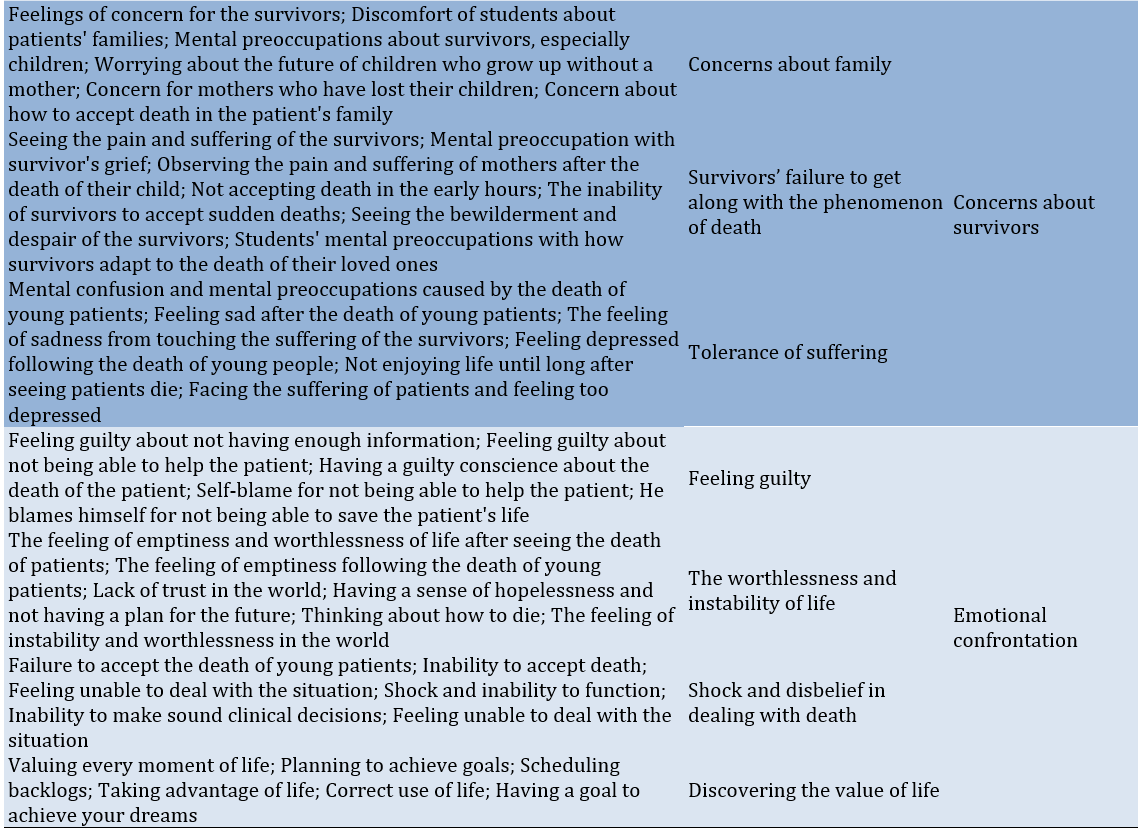

Concerns about survivors

One of the most important points highlighted by the participants was their excessive concerns about survivors and how they get along with the death of their loved ones, especially those who witnessed the death and loss of people who had severe emotional dependence on them: “Someone who dies is relieved from pain and suffering. But, the survivors have to suffer the deceased’s loss for a lifetime and this is really terrifying. The survivor suffers a lot and no one can help him/her. Death is a bitter story for survivors” (Participant #7). Another participant stated, “A 4-year-old child who had fallen from the bed and died was transferred to the EMS center. I could see how horrible was the patients’ conditions. They were feeling guilty and blaming each other. I think the parents would suffer lots of psychological distress for the rest of their lives” (Participant #2).

Emotional confrontation

The nursing students reacted differently when witnessing a patient’s death depending on their beliefs, culture, and the context, in which they grew. Some participants stated that they used defensive mechanisms, such as denial, shock, and disbelief. Some others highlighted the absurdity, worthlessness, and instability of life in the world. However, only a few participants had realized the main value and essence of life: “When I was sitting next to one of the patients, asking her medical records and symptoms, she suddenly changed her tone. When I held her hand, it was very cold. I was afraid for a moment and called the trainer. As she was looking at me, her head bent suddenly as if she was dying. It was a strange shock. During the moments she was undergoing CPR, I was thinking how life is meaningless and it does not deserve grieving” (Participant #3). Another participant stated, “When my uncle died, I didn’t believe it. I even did not dare to go ahead and look at his dead body. I wished it was a dream and when I woke up I would realize that I had been dreaming” (Participant #6).

Another participant stated, “Something that makes me really upset is to see the pain and suffering of a hospitalized patient. It’s also agonizing to see how much the patient’s family members are worried” (Participant #11). Finally, one of the participants stated, “When I think that I will eventually die, I’m going to make some plans so that I can at least achieve one of my goals and ambitions before I die” (Participant #5).

The dataset used in the current study are available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Discussion

The present study aimed to explain death anxiety among nursing students using a qualitative approach. One of the most important themes highlighted by almost all participants was the reality of death and its existential necessity, a topic that has been explored by various philosophical schools. Each of these schools evaluates the issue of death based on their understanding of human truth. According to materialistic thinking, the entirety of the human being is confined to the body, and death is viewed as the destruction and end of life. However, from a divine perspective, human reality is seen as a transcendental and spiritual truth that exists beyond the physical body [20]. For example, Heidegger posits that confronting this primary possibility (death) consumes all other possibilities, leaving only two options: acceptance or acceptance. The only wise course of action is to face the bitter reality of our futility with courage and to openly acknowledge that death is an inevitable event that our intellect and senses are unable to fully comprehend [21], which confirms the results of the present study.

The nursing students stated that nobody has experienced or encountered death thus far. For this reason, contemplating death causes anxiety [22]. Previous studies have shown that preoccupation with death can also invoke anxiety and depression in some religious individuals [6], as death anxiety does not provide a clear understanding of the nature and quality of life after death. However, the level of this anxiety is lower when the idea of post-mortem life is acknowledged rather than denied [23]. Belief in the existence of life after death contributes to individuals’ ability to accept both the positive and negative aspects of life and death [24], as confirmed by the data in this study.

The participants defined concepts of death from different perspectives, reflecting their deep understanding of this phenomenon. Accordingly, it can be argued that individuals’ attitudes toward all phenomena, including death, are influenced by their worldview and the approach they adopt toward the social world. These approaches give meaning to individuals’ behaviors [6].

When we consider death as annihilation, the sense of helplessness in the universe makes us anxious. In this view, only annihilation is stable, while the world of creation appears bizarre, caught in instability and baselessness [25]. For this reason, many people regard death as a forbidden subject and a taboo, avoiding discussions about it [26, 27]. However, Yalom [25] found a meaningful relationship between death and the quality of life. Those who do not have a correct understanding of death consequently struggle to achieve a comprehensive understanding of life, leading them to live poorly due to their fear of death [28]. Conversely, thinkers, such as Sartre and Camus, who addressed absurdity, believe in a clear relationship between death and absurdity [25].

Meanwhile, religions have sought to justify death for their followers; they aim to add spirituality to their lives and to provide meaning to their existence [5]. Believers in God and immortality view death as a manifestation of life. According to them, human existence will attain a higher perfection after death, and the existential aspect of humans after death is far stronger than their existence in this world [5]. These findings were supported by the data in the present study.

This theme represents the emotions and views of the participants regarding death and the process of dying. According to the participants, death during illness is unpleasant for everyone involved. A dying person often feels lonely. Death has become a mechanical phenomenon influenced by the social and technological world [3], making it difficult to determine the exact moment when death occurs [29]. Accordingly, Cooper and Barnett demonstrated that the physical suffering of patients causes nursing students to feel anxious about caring for dying individuals. These emotions are especially intense in cases where the patients are young or when death occurs unexpectedly, compared to the death of older individuals, which can often be anticipated [30].

Almost all participants pointed out that the survivors of a person who has passed away endure severe physical and emotional changes. They exhibit a variety of emotions, such as shock, disbelief, depression, and profound pain caused by the loss of loved ones. Unfortunately, these individuals are typically overlooked by healthcare staff. Changes that occur in the survivors include an unwillingness to continue working, a withdrawal from everyday routines, a lack of interest in recreation and sightseeing, reluctance to manage personal affairs, and a general absence of joy at home [31].

Analysis of the nursing students indicated that they were overwhelmed by feelings of fear and anxiety during their initial confrontation with death. The vivid mental images and the unknown nature of their reactions create emotional confusion, making adaptation difficult [29]. Furthermore, as nursing students are in the final years of adolescence, the impact of death and its emotional burden may be intensified [7]. Similarly, Kent et al. found that this experience among nursing students can lead to prolonged preoccupations [32].

The findings of this study indicated that nursing students’ experiences in caring for dying patients affect them in various ways. Their narratives focused on their fears, reactions, and feelings encountered when they faced death. Additionally, the anxiety associated with a loss of control and the inability to support patients and their family members was a primary concern for the nursing students. Lillyman et al. demonstrated that receiving bad news, interacting with dying patients and their families, and witnessing the deterioration of patients were examples of negative emotions and experiences among nursing students [33], as indicated in the present study. Cooper & Barnett also showed that students experience a range of emotions, such as sadness, vulnerability, irregularity, and sympathy, which can limit healthcare professionals’ ability to care for dying patients [30]. Furthermore, King-Okoye & Arber suggested that nursing students require support to enhance their self-confidence and ability to care for dying patients [34].

With an enhanced awareness of death, we can deepen our understanding of life. The readiness to confront death allows us to form a profound connection with the world and its people. Thus, given the sensitivity of nursing and the importance of nurses’ preparedness for providing better care to dying patients, the curriculum of nursing undergraduate programs needs to focus on death-related issues and raise students’ awareness of their emotions when faced with patients’ deaths. Students also require more time and opportunities to perceive and reflect on their feelings. Additionally, training courses on how to handle a patient’s death must be included in educational programs.

Encountering death has been reported as one of the most distinctive experiences during the clinical training of nursing students. For this reason, it is essential to prepare nurses to provide better care for dying patients by focusing on issues related to death and increasing students’ awareness of their feelings when confronted with the death of patients.

Conclusion

There are many concepts regarding the concept of death, with one of the most important ones highlighted by almost all participants being the reality of death and its existential necessity.

Acknowledgments: Zahedan University of Medical Sciences approved this study. The authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences and the nursing students at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The project was approved by the institutional review board of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (Coded IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.243). When recruiting participants, the purpose of the study was clearly explained, and informed consent (both written and oral) was obtained. Participants were granted the right to decline or withdraw from the study at any time. They were assured of the confidentiality of all gathered data and informed that results would be shared with them upon request. To ensure the anonymity of participants’ identities, we used abbreviations. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sarhadi M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (85%); Mazloom S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (15%)

Funding/Support: No funding was received.

Death is a natural and inevitable part of the life cycle [1] and a biological event that signifies the permanent cessation of vital signs and functions of the heart [2]. With the occurrence of death, a process that we call life ends logically and definitively, revealing its entirety and totality [3]. However, contemplating death can be frightening, and most people prefer not to think about it [4, 5] because, despite technological advances, it serves as a reminder of human vulnerability. Thus, fear of death, or death anxiety, is an unpleasant and common human experience [6] and one of the fundamental factors underlying all human anxieties [7].

According to the British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), death anxiety is a feeling of panic, fear, or anxiety when contemplating the process of dying, losing one’s connection with the world, or what happens after death. This type of anxiety encompasses motivational, cognitive, and emotional components and changes under the influence of developmental stages and events in social and cultural life [8, 9]. Existential theorists also believe that death anxiety is a generalized fear and disorder caused by existential anxiety. They suggest that we experience existential anxiety because we are aware that our lives are limited and fear the death that awaits us [10]. According to Choron, there are three types of death anxiety, including anxiety caused after death, anxiety caused during death, and anxiety caused by a feeling of nothingness and destruction. He considers the first two types to be related to the physical process of death, while he regards the third type of anxiety as the most significant concern of human existence [11]. However, since every human ultimately faces the event of death, one’s attitude toward it is one of the most important factors that affect behavior related to healthcare professions [12].

This is particularly relevant since the confrontation with death has been reported as one of the most distinct experiences during the clinical education of nursing students, making adaptability to the pain and suffering of patients difficult for them [7]. Accordingly, studies have shown that most students are concerned about their lack of ability to adapt to these situations [13]. They attempt to cope with death but are not emotionally ready to care for dying patients, as such emotional reactions can limit their professional capacity to provide care [14]. Thus, it is essential to shed light on students’ experiences of death, as well as their involvement in end-of-life patient care [14]. This knowledge can help nurses understand and prepare for the care of any individual who faces the challenging moments of their own death or the death of others [15]. Therefore, since death is an important and significant event in nursing practice, exploring individuals’ attitudes toward death and dying should begin during academic studies. Moreover, examining the experiences of nursing students in relation to their social and cultural context may affect their coping abilities and skills.

Accordingly, since nursing students should take responsibility for the care of dying patients and their families during their studies and afterward, more effective methods must be employed to explain nursing students’ experiences. Thus, qualitative research can help achieve this goal. To this end, the present study aimed to explore death anxiety in nursing students using a qualitative (content analysis) method.

Participants and Methods

The present study was conducted using a conventional content analysis qualitative approach on participants selected through purposive sampling from nursing students at the School of Nursing and Midwifery in Zahedan in 2023-2024. These individuals were selected from among those who had completed one year of education, had a history of completing an internship, had experience in caring for patients in the final stages, had experience in the emergency room, and had experience with the death of a patient. A total of 12 participants, with an average age of 21 years, were interviewed over two months. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews. After obtaining the necessary legal permits and explaining the objectives of the study to the participants, the interviews were conducted as two-way conversations.

Following the main research question, the interviews began with open-ended questions: “Could you talk about your experiences with death?” and “When you think about death, what comes to your mind?” Subsequent questions were then asked based on the participants’ responses and aimed to enrich the data. Furthermore, probing questions (e.g., “Could you explain more about it?” and “What do you mean by …?”) were posed for further clarification and to elicit additional information. At the end of the interviews, participants were asked if they had any other comments to add to their statements. Depending on the time available, the collected data, the participants’ conditions, and their willingness, each interview was conducted in one or more sessions. All interviews were recorded after obtaining the participants’ oral consent and transcribed word for word within 24 hours. The duration of each interview was approximately 40 minutes.

The data were analyzed simultaneously with data collection using the five-step qualitative content analysis method (Graneheim & Lundman). The steps were transcribing the content of each interview immediately, reading each transcript several times to develop a general understanding of its content, identifying meaning units and primary codes, classifying similar codes into more comprehensive clusters, and extracting the themes hidden in the data [16].

To this end, after completing each interview, its content was transcribed immediately. The transcripts were then read several times, and the primary codes were extracted. Afterward, related codes were merged into a single category based on their similarities. Finally, the themes hidden in the data were identified and extracted. During the analysis, many of the codes were revised multiple times, and the extracted categories were also named. Memos were used to thoroughly identify the codes and enhance the efficacy of the data analysis process [17, 18].

The four criteria proposed by Lincoln & Guba were used to ensure data trustworthiness, including credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability [19].

The researchers employed specific qualitative research methods, such as ongoing engagement with the subjects and data, as well as member checks, to ensure the credibility of the data. The codes were adjusted in case of disagreement with the opinions of the participants. Additionally, the researchers utilized a combination of researchers, continuous data comparison, code review, and sampling with a diverse range of participants.

For dependability, an external observer reviewed the codes and themes identified in this study (external check, peer check) to enhance their rigor, ensuring that any existing contradictions and defects were addressed and corrected to reach a consensus. All activities were recorded, and a report on the research process was prepared for conformability. The findings were also shared with two patients and two spouses of patients who were not participants in the study but had similar conditions to those of the participants, and they approved the data.

Furthermore, the confidentiality of all interviews and the freedom of individuals to withdraw from the research were maintained. It should be noted that the data were analyzed using MAXQDA2020 software.

Findings

The participants consisted of 12 nursing students, including four sophomores, four juniors, and four seniors, all of whom had experienced the death of their relatives or patients in the ward. The age of the participants ranged from 19 to 25 years, with a mean age of 21.17±1.07 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of nursing students

After data analysis, 114 themes were extracted and organized into six main categories and 22 subcategories (Table 2).

Table 2. The main categories and subcategories of death anxiety in nursing students

The reality of death and its existential necessity

The participants acknowledged the finality and reality of death. They regarded death as something inevitable and recognized that they would confront it sooner or later: “Death is a reality, whether like it or not. In fact, it is part of life. It finds meaning in the cycle of life, and life is meaningless without death. Thus, as a human, we know that we will die at the end and we should accept it, but no one knows who the hereafter looks like” (Participant #3).

Non-confrontation with death and the lack of after-death experiences

The participants also highlighted the unknown nature and uncertainty of fate after death. They viewed death as a definite and inevitable phenomenon that will happen to anyone. However, beneath the surface of their words and expressions, there was a notable tendency to resist accepting death and the concept of an afterlife. For instance, one of the participants stated, “I think since you don’t know the hereafter and have no idea of what is going to happen there for you, you cannot decide what is true or wrong about it, and if you have to believe it or not. And, this makes you anxious. Because there are a lot of conflicting ideas about the world after death and you cannot find out which one is right or wrong” (Participant #1). Another participant stated, “Everyone says there is a world but they cannot say what kind of world it is” (Participant #1). One of the participants stated, “I have witnessed the death of patients several times during my internship course. I always wonder if there is really another world, nobody has returned from it to confirm its existence and no one has ever experienced it” (Participant #8).

The meaning of death

The nursing students held different views about the meaning of death, influenced by their individual circumstances and religious beliefs. Some participants regarded death as an evolutionary stage and a transition to higher realms. Others perceived it as a representation of human mortality and the end of life. Additionally, some participants viewed it as a form of liberation and a release from life’s problems, while others equated it directly with life: “In my opinion, death is like a wall that you can go through its other side but you cannot get back to the opposite side. I think a person forgets those moments like the moment of his/her birth. A person who is born can never go back to the womb. It’s impossible. Thus, a person who is going through evolution must go to the next stage” (Participant #4).

Some of the nursing students also interpreted the meaning of death according to their religious beliefs: “The meaning of death depends on a person’s religion. For example, our religion says if you commit sins, you’ll go to hell and you will be reckoned and punished in the hereafter for even a small sin committed in this world. Thus, you are afraid of being punished in the hereafter. Religion is always inducing fear in you. You aren’t sure. The religious instructions are more stressful than pacifying and make you afraid of dying” (Participant #1).

The quality of death and dying

According to the participants, although death was a necessity, the quality of death was also effective in death anxiety. They believed that although the death of the patient and disabled person who had a chronic illness brings a sense of comfort and relief for both patient and family members, sudden, unusual deaths and thinking of them cause severe fear and anxiety: “In my opinion, dying in a car accident is very horrible. It’s very terrible thinking that your body is crushed in the middle of the pieces of a car and that the pain that a person suffers until he/she dies” (Participant #12). Another participant stated, “Well, in my opinion, death is a good blessing when a person gets very old and disabled and he/she becomes dependent on other people for doing even the smallest things. In the beginning, maybe everyone will try to help, but it is not practical. Even the patient gets in trouble. For example, when my grandmother died after having been severely disabled, I felt that she was relieved. Because I always heard she was praying to God and asking for a death with dignity” (Participant #7).

Concerns about survivors

One of the most important points highlighted by the participants was their excessive concerns about survivors and how they get along with the death of their loved ones, especially those who witnessed the death and loss of people who had severe emotional dependence on them: “Someone who dies is relieved from pain and suffering. But, the survivors have to suffer the deceased’s loss for a lifetime and this is really terrifying. The survivor suffers a lot and no one can help him/her. Death is a bitter story for survivors” (Participant #7). Another participant stated, “A 4-year-old child who had fallen from the bed and died was transferred to the EMS center. I could see how horrible was the patients’ conditions. They were feeling guilty and blaming each other. I think the parents would suffer lots of psychological distress for the rest of their lives” (Participant #2).

Emotional confrontation

The nursing students reacted differently when witnessing a patient’s death depending on their beliefs, culture, and the context, in which they grew. Some participants stated that they used defensive mechanisms, such as denial, shock, and disbelief. Some others highlighted the absurdity, worthlessness, and instability of life in the world. However, only a few participants had realized the main value and essence of life: “When I was sitting next to one of the patients, asking her medical records and symptoms, she suddenly changed her tone. When I held her hand, it was very cold. I was afraid for a moment and called the trainer. As she was looking at me, her head bent suddenly as if she was dying. It was a strange shock. During the moments she was undergoing CPR, I was thinking how life is meaningless and it does not deserve grieving” (Participant #3). Another participant stated, “When my uncle died, I didn’t believe it. I even did not dare to go ahead and look at his dead body. I wished it was a dream and when I woke up I would realize that I had been dreaming” (Participant #6).

Another participant stated, “Something that makes me really upset is to see the pain and suffering of a hospitalized patient. It’s also agonizing to see how much the patient’s family members are worried” (Participant #11). Finally, one of the participants stated, “When I think that I will eventually die, I’m going to make some plans so that I can at least achieve one of my goals and ambitions before I die” (Participant #5).

The dataset used in the current study are available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Discussion

The present study aimed to explain death anxiety among nursing students using a qualitative approach. One of the most important themes highlighted by almost all participants was the reality of death and its existential necessity, a topic that has been explored by various philosophical schools. Each of these schools evaluates the issue of death based on their understanding of human truth. According to materialistic thinking, the entirety of the human being is confined to the body, and death is viewed as the destruction and end of life. However, from a divine perspective, human reality is seen as a transcendental and spiritual truth that exists beyond the physical body [20]. For example, Heidegger posits that confronting this primary possibility (death) consumes all other possibilities, leaving only two options: acceptance or acceptance. The only wise course of action is to face the bitter reality of our futility with courage and to openly acknowledge that death is an inevitable event that our intellect and senses are unable to fully comprehend [21], which confirms the results of the present study.

The nursing students stated that nobody has experienced or encountered death thus far. For this reason, contemplating death causes anxiety [22]. Previous studies have shown that preoccupation with death can also invoke anxiety and depression in some religious individuals [6], as death anxiety does not provide a clear understanding of the nature and quality of life after death. However, the level of this anxiety is lower when the idea of post-mortem life is acknowledged rather than denied [23]. Belief in the existence of life after death contributes to individuals’ ability to accept both the positive and negative aspects of life and death [24], as confirmed by the data in this study.

The participants defined concepts of death from different perspectives, reflecting their deep understanding of this phenomenon. Accordingly, it can be argued that individuals’ attitudes toward all phenomena, including death, are influenced by their worldview and the approach they adopt toward the social world. These approaches give meaning to individuals’ behaviors [6].

When we consider death as annihilation, the sense of helplessness in the universe makes us anxious. In this view, only annihilation is stable, while the world of creation appears bizarre, caught in instability and baselessness [25]. For this reason, many people regard death as a forbidden subject and a taboo, avoiding discussions about it [26, 27]. However, Yalom [25] found a meaningful relationship between death and the quality of life. Those who do not have a correct understanding of death consequently struggle to achieve a comprehensive understanding of life, leading them to live poorly due to their fear of death [28]. Conversely, thinkers, such as Sartre and Camus, who addressed absurdity, believe in a clear relationship between death and absurdity [25].

Meanwhile, religions have sought to justify death for their followers; they aim to add spirituality to their lives and to provide meaning to their existence [5]. Believers in God and immortality view death as a manifestation of life. According to them, human existence will attain a higher perfection after death, and the existential aspect of humans after death is far stronger than their existence in this world [5]. These findings were supported by the data in the present study.

This theme represents the emotions and views of the participants regarding death and the process of dying. According to the participants, death during illness is unpleasant for everyone involved. A dying person often feels lonely. Death has become a mechanical phenomenon influenced by the social and technological world [3], making it difficult to determine the exact moment when death occurs [29]. Accordingly, Cooper and Barnett demonstrated that the physical suffering of patients causes nursing students to feel anxious about caring for dying individuals. These emotions are especially intense in cases where the patients are young or when death occurs unexpectedly, compared to the death of older individuals, which can often be anticipated [30].

Almost all participants pointed out that the survivors of a person who has passed away endure severe physical and emotional changes. They exhibit a variety of emotions, such as shock, disbelief, depression, and profound pain caused by the loss of loved ones. Unfortunately, these individuals are typically overlooked by healthcare staff. Changes that occur in the survivors include an unwillingness to continue working, a withdrawal from everyday routines, a lack of interest in recreation and sightseeing, reluctance to manage personal affairs, and a general absence of joy at home [31].

Analysis of the nursing students indicated that they were overwhelmed by feelings of fear and anxiety during their initial confrontation with death. The vivid mental images and the unknown nature of their reactions create emotional confusion, making adaptation difficult [29]. Furthermore, as nursing students are in the final years of adolescence, the impact of death and its emotional burden may be intensified [7]. Similarly, Kent et al. found that this experience among nursing students can lead to prolonged preoccupations [32].

The findings of this study indicated that nursing students’ experiences in caring for dying patients affect them in various ways. Their narratives focused on their fears, reactions, and feelings encountered when they faced death. Additionally, the anxiety associated with a loss of control and the inability to support patients and their family members was a primary concern for the nursing students. Lillyman et al. demonstrated that receiving bad news, interacting with dying patients and their families, and witnessing the deterioration of patients were examples of negative emotions and experiences among nursing students [33], as indicated in the present study. Cooper & Barnett also showed that students experience a range of emotions, such as sadness, vulnerability, irregularity, and sympathy, which can limit healthcare professionals’ ability to care for dying patients [30]. Furthermore, King-Okoye & Arber suggested that nursing students require support to enhance their self-confidence and ability to care for dying patients [34].

With an enhanced awareness of death, we can deepen our understanding of life. The readiness to confront death allows us to form a profound connection with the world and its people. Thus, given the sensitivity of nursing and the importance of nurses’ preparedness for providing better care to dying patients, the curriculum of nursing undergraduate programs needs to focus on death-related issues and raise students’ awareness of their emotions when faced with patients’ deaths. Students also require more time and opportunities to perceive and reflect on their feelings. Additionally, training courses on how to handle a patient’s death must be included in educational programs.

Encountering death has been reported as one of the most distinctive experiences during the clinical training of nursing students. For this reason, it is essential to prepare nurses to provide better care for dying patients by focusing on issues related to death and increasing students’ awareness of their feelings when confronted with the death of patients.

Conclusion

There are many concepts regarding the concept of death, with one of the most important ones highlighted by almost all participants being the reality of death and its existential necessity.

Acknowledgments: Zahedan University of Medical Sciences approved this study. The authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences and the nursing students at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The project was approved by the institutional review board of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (Coded IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.243). When recruiting participants, the purpose of the study was clearly explained, and informed consent (both written and oral) was obtained. Participants were granted the right to decline or withdraw from the study at any time. They were assured of the confidentiality of all gathered data and informed that results would be shared with them upon request. To ensure the anonymity of participants’ identities, we used abbreviations. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sarhadi M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (85%); Mazloom S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (15%)

Funding/Support: No funding was received.

Article Type: Qualitative Research |

Subject:

Quality of Life

Received: 2024/06/2 | Accepted: 2024/09/7 | Published: 2024/09/30

Received: 2024/06/2 | Accepted: 2024/09/7 | Published: 2024/09/30

References

1. Neimeyer RA, Wittkowski J, Moser RP. Psychological research on death attitudes: An overview and evaluation. Death Stud. 2004;28(4):309-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/07481180490432324]

2. Leming MR, Dickinson GE. Understanding dying, death, and bereavement. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2010. [Link]

3. Yazdany M, Javaheri F. Detection of attitude towards death and related social factors with it among the elderly in Tehran. Iran J Sociol. 2016;10(2-3):77-101. [Persian] [Link]

4. Feifel H. Psychology and death: Meaningful rediscovery. Am Psychol. 1990;45(4):537-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.537]

5. Hashemi ZS, Alizamani AA, Zamani M, Khoshteinat V. Thanatopsis from the view of Irvin Yalom and its effect on meaning fullness to life. QABASAT. 2018;23(88):121-50. [Persian] [Link]

6. Tavan B, Jahani F, Hekmatpou D. Death concept from academicians' point of view: A qualitative research. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2013;2(4):358-65. [Persian] [Link]

7. Edo‐Gual M, Tomás‐Sábado J, Bardallo‐Porras D, Monforte‐Royo C. The impact of death and dying on nursing students: An explanatory model. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(23-24):3501-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.12602]

8. Hamidi O, Seifi Ghozlu J, Sharifi G, Lavasani MG. The relationship between the personal values and death anxiety among MS patients. J Psychol. 2014;17(4):365-80. [Persian] [Link]

9. Shafaii M, Payami M, Amini K, Pahlevan S. The relationship between death anxiety and quality of life in hemodialysis patients. J HAYAT. 2017;22(4):325-38. [Persian] [Link]

10. Dehghan K, Shariatmadar A, Hormozy A. Effectiveness of life review therapy on death anxiety and life satisfaction of old women of Tehran. Couns Cult Psychother. 2015;6(22):15-39. [Persian] [Link]

11. De Castro A. An integration of the existential understanding of anxiety in the writings of Rollo May, Irvin Yalom, and Kirk Schneider [dissertation]. San Francisco: Saybrook University; 2010. [Link]

12. Wessel EM, Garon M. Introducing reflective narratives into palliative care home care education. Home Healthc Nurse. 2005;23(8):516-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00004045-200508000-00012]

13. Abu Hasheesh MO, Al-Sayed AboZeid S, Goda El-Zaid S, Alhujaili AD. Nurses' characteristics and their Attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients in a public hospital in Jordan. Health Sci J. 2013;7(4):384-94. [Link]

14. Ek K, Westin L, Prahl C, Osterlind J, Strang S, Bergh I, et al. Death and caring for dying patients: Exploring first-year nursing students' descriptive experiences. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(10):509-15. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.10.509]

15. Mondragón-Sánchez EJ, Cordero EAT, Espinoza MdLM, Landeros-Olvera EA. A comparison of the level of fear of death among students and nursing professionals in Mexico. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2015;23(2):323-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/0104-1169.3550.2558]

16. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001]

17. Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Link]

18. Burns N, Grove SK. Understanding nursing research-eBook: Building an evidence-based practice. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010. [Link]

19. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. RSVP: We are pleased to accept your invitation. Eval Pract. 1994;15(2):179-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109821409401500207]

20. Sulaymani F. Fear of death on the basis of Ibn Sina and Mulla Sadra's view. Avicennian Philos J. 2019;12(40):75-101. [Persian] [Link]

21. Blackham HJ. Six existentialist. Hakimi M, translator. Tehran: Markaz; 2000. [Persian] [Link]

22. Masoudi Sh, Hatami H, Modares Gharavi M, Bani Jamali Sh. The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in relationship between attachment styles and anxiety of death among cancer patients. J Thought Behav Clin Psychol. 2016;10(39):37-46. [Persian] [Link]

23. Sadri Demichi E, Ramezani Sh. Eeectivness of existential therapy on loneliness and death anxity in the elderly. Aging Psychol. 2016;2(1):1-12. [Persian] [Link]

24. Bakereyan S, Eranmanes S, Abaszadeh A. Comparison of Bam and Kerman nursing students' attitude about death and dying. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2010;9(1):54-60. [Persian] [Link]

25. Yalom ID. Existential psychotherapy. Habib S, translator. Tehran: Ney Publication; 2020. [Persian] [Link]

26. Khaki S, Khesali Z, Farajzadeh M, Dalvand S, Moslemi B, Ghanei Gheshlagh R. The relationship of depression and death anxiety to the quality of life among the elderly population. J HAYAT. 2017;23(2):152-61. [Persian] [Link]

27. Chan LC, Yap CC. Age, gender, and religiosity as related to death anxiety. Sunway Acad J. 2009;6:1-16. [Link]

28. Josselson R. Irvin D. Yalom: On psychotherapy and the human condition. New York: Jorge Pinto; 2007. [Link]

29. Li H, Li H, Lu Y, Panagiotelis A. A forecast reconciliation approach to cause-of-death mortality modeling. Insur Math Econ. 2019;86:122-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.insmatheco.2019.02.011]

30. Cooper J, Barnett M. Aspects of caring for dying patients which cause anxiety to first year student nurses. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11(8):423-30. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.8.19611]

31. Seifi F, Farah Bidjari A. Bereaved parents' changes and needs after losing their child to cancer: A qualitative research. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2018;7(1):48-59. [Persian] [Link]

32. Kent B, Anderson NE, Owens RG. Nurses' early experiences with patient death: The results of an on-line survey of registered nurses in New Zealand. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(10):1255-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.005]

33. Lillyman S, Gutteridge R, Berridge P. Using a storyboarding technique in the classroom to address end of life experiences in practice and engage student nurses in deeper reflection. Nurse Educ Pract. 2011;11(3):179-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2010.08.006]

34. King‐Okoye M, Arber A. 'It stays with me': The experiences of second‐and third‐year student nurses when caring for patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23(4):441-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/ecc.12139]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |