Volume 12, Issue 3 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(3): 389-398 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Fatourehchi S, Keshavarz Afshar H, Asadi M, Aslani K. Effect of Emotion-Focused Group Therapy on Feelings of Shame and Affective Control in Post-Divorce Women. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (3) :389-398

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-75092-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-75092-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Counseling, Aras International Campus, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty Psychology & Education Science, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Psychology and Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, Arak University, Arak, Iran

4- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Educational Science and Psychology, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty Psychology & Education Science, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Psychology and Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, Arak University, Arak, Iran

4- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Educational Science and Psychology, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 778 kb]

(2831 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1382 Views)

Full-Text: (101 Views)

Introduction

Marriage significantly influences individuals’ roles and developmental trajectories [1]. It not only provides numerous benefits, such as reduced stress and increased happiness [2, 3], but also impacts occupational and mental health indirectly through marital satisfaction [1]. However, instability in marriages is prevalent globally, often leading to divorce and its associated adversities, including high-conflict separations [4-6].

Divorce typically results from unmet expectations and disparities in resource exchange between spouses, which have increased globally over recent decades [7, 8]. This rise in divorces jeopardizes family mental health and leads to loss of attachment, diminished social support, and increased negative thoughts [3, 9].

The effects of divorce are particularly severe for women, who often experience greater economic hardships and psychological stress while managing the majority of post-divorce challenges, including custody and a reduced likelihood of remarriage [9-11]. This often results in heightened anxiety, stress, depression, lower adaptability, and decreased happiness [12-17]. Studies have identified significant emotional regulation challenges among divorced women, marked by increased psychological disturbances and reduced affective control [18-20].

Emotion regulation is crucial for managing stress and maintaining mental health, playing a key role in personal development, ethical behavior, and interpersonal relationships [21-23]. Difficulties in emotion regulation can make stressors appear more threatening, which is pivotal in the development of stress-related symptoms [24, 25]. Furthermore, the post-divorce adaptation process is often emotionally painful, affecting the capacity to regulate emotions such as anger, depression, anxiety, positive emotions, and internal shame [26].

Anger, a natural response to unmet expectations, can vary in intensity, and if mismanaged, may lead to psychological issues [27]. Research highlights that improper anger management is a significant factor contributing to increased depression and mental exhaustion [28, 29]. Additionally, post-divorce, many women report heightened unhappiness, depression, and anxiety, underscoring the need for emotional support [30-34].

Studies have also considered positive mood and internalized shame, with positive emotions being crucial for well-being and negative emotions, like shame having profound impacts on mental health following divorce [35-41]. Addressing these emotional challenges is essential, and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) has been identified as an effective approach. EFT helps individuals navigate their emotional landscape post-divorce, enhancing emotional awareness and coping mechanisms [42-46].

Extensive research supports EFT’s effectiveness in improving emotional and mental health across various demographics [47-52]. However, there is a gap in its application to emotion regulation and internalized shame among divorced women in Iran, which necessitates further study [53-55]. This research aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of EFT in helping divorced women in Iran regulate their emotions and adapt post-divorce, potentially informing therapeutic practices and policy decisions.

Materials and Methods

Participants and design

This quasi-experimental study utilized a pre-test-post-test design with follow-up assessments at one and three months, and was conducted at a designated counseling center during the first half of 2022. The statistical population included all women visiting a designated counseling center during the first half of 2022 and were recruited through a purposeful sampling method. The sample size was calculated using PASS software, aiming for an 80% power and a 0.05 alpha level. Practical considerations and references to prior studies [56] led to the selection of 16 participants, who were then randomly assigned into two groups of eight; an experimental group receiving EFT and a control group. Both groups were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Inclusion criteria included no diagnosed mental disorders as per the SCL-90-R questionnaire, a minimum average score on the self-criticism questionnaire, being divorced for at least six months, being aged between 20 and 45, having no concurrent psychotherapy sessions, and having no prior engagement in psychotherapy or psychiatry. Participants also needed to provide informed consent.

The intervention consisted of an EFT conducted by a researcher and a facilitator, both trained in introductory and advanced levels of this therapeutic approach. The therapy sessions were followed by post-tests administered in the final session and subsequent follow-ups after one and three months. Following the study, the control group received the same EFT from late March to early June 2023, maintaining ethical standards.

The content validity of the therapeutic protocol was assessed using the content validity ratio (CVR), as outlined by Lawshe in 1975. Ten field experts evaluated the relevance of each session’s content and exercises using a three-part Likert scale (essential, useful but not essential, and not necessary). The required minimum CVR value was 0.62, while the obtained CVR was 0.86, indicating robust content validity.

The detailed content of the therapy sessions and the resources utilized were critically examined for alignment with the study’s objectives and theoretical underpinnings, ensuring a high standard of intervention fidelity.

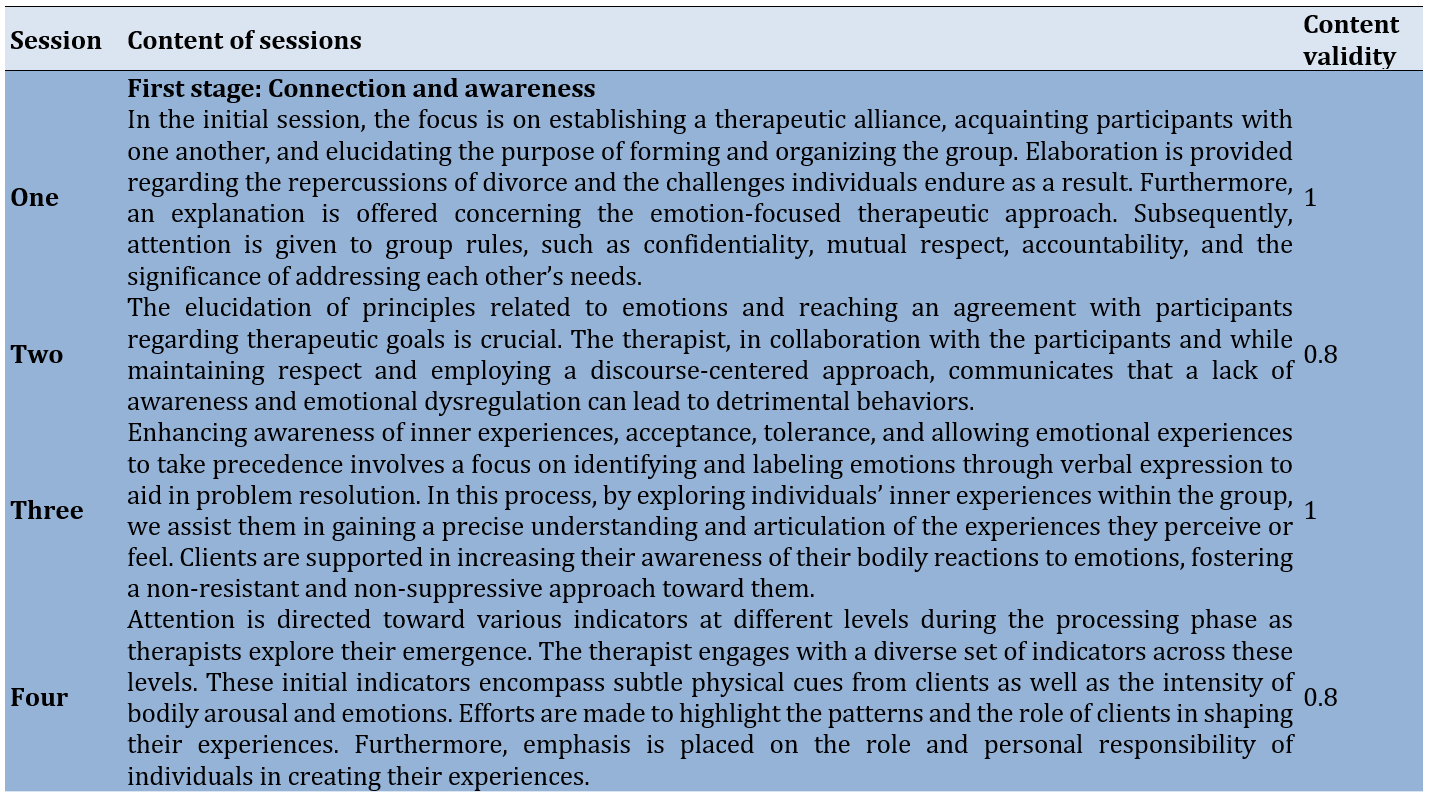

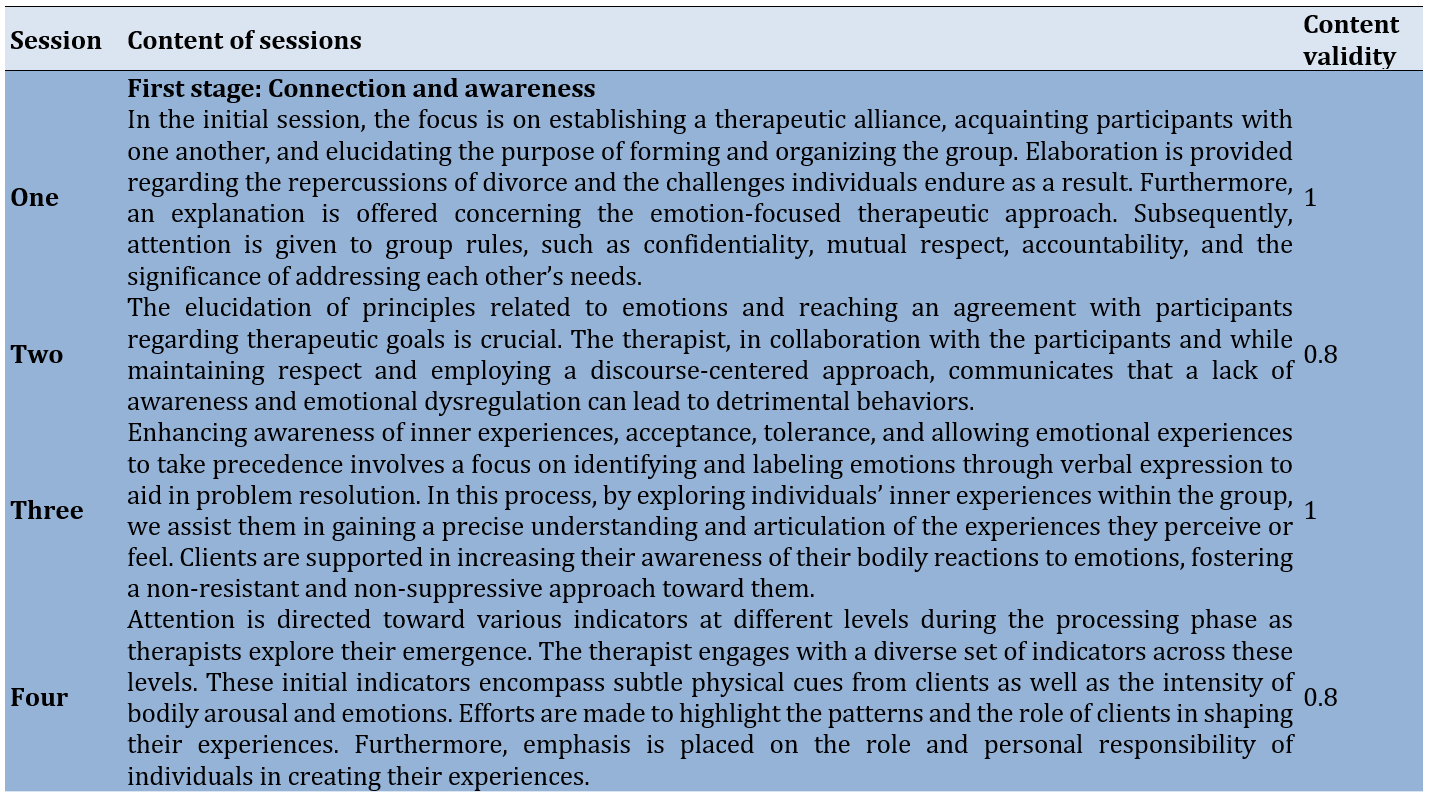

The format of the EFT sessions adhered to the guidelines of Greenberg & Goldman [57] and Thompson & Girz [58], consisting of 12 steps (sessions), each lasting 120 minutes. These sessions were conducted with a facilitator and involved a trial group comprising ten participants (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of group emotional therapy sessions

Research tools

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by the researcher to collect information related to the demographic characteristics of the population. It included questions regarding specific demographic details, such as the duration since divorce, the absence of prior psychiatric hospitalization due to acute psychological issues, educational level, and age.

Affective Control Scale (ACS)

This scale developed by Williams et al. [59] serves as a tool for assessing individuals’ control and management of their emotions, comprising 42 statements across four sub-scales, including anger (8 items), depressive mood (8 items), anxiety (13 items), and positive affect (13 items). Responses are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (one) to strongly agree (five). Inverted scoring is applied to items 9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 27, 30, 31, and 38. The internal consistency and test-retest reliability for the entire scale are 0.94 and 0.78, respectively; for the anger subscale, they are 0.72 and 0.73, for depressive mood, 0.91 and 0.76, for anxiety, 0.89 and 0.77; and for positive affect, 0.84 and 0.60. Discriminant and convergent validity have been established for a sample of undergraduate students. Additionally, the retest reliability coefficient for the scale after two weeks is 0.78, and for the subscales, it ranges from 0.66 to 0.77 [59]. In a study conducted by Tamborini et al. [15] to assess the validity, reliability, and preliminary standardization of the scale in five groups from the Kermanshah urban community, internal consistency was reported with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.78 for students, 0.82 for university students, 0.89 for teachers, 0.91 for nurses, and 0.94 for professors.

The Internalized Shame Scale (ISS)

This scale, developed by Cook [60], consists of 30 items and two subscales, including 24 items for the inferiority subscale (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, and 30) and six items for the self-esteem subscale (8, 13, 14, 19, 26, and 29). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert-type scale. The scoring is reversed; thus, higher scores on this scale indicate feelings of worthlessness, inadequacy, contempt, emptiness, and loneliness, while lower scores signify higher self-esteem [61]. Cook [60] reported Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the inferiority and self-esteem subscales as 0.94 and 0.90, respectively. Additionally, Rajabi & Abasi [62] reported the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the ISS as 0.90 for the overall sample, 0.89 for males, and 0.91 for females. In the research by Fatolaahzadeh et al. [63], Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was 0.91.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were employed. Inferential statistics, such as independent t-test (continuous parameters), Chi-square test (categorical parameters), and repeated measures ANOVA were utilized to assess the effects of the intervention over time and between groups. The inferential analyses were conducted at a significance level of 0.05 using SPSS 25 software.

Findings

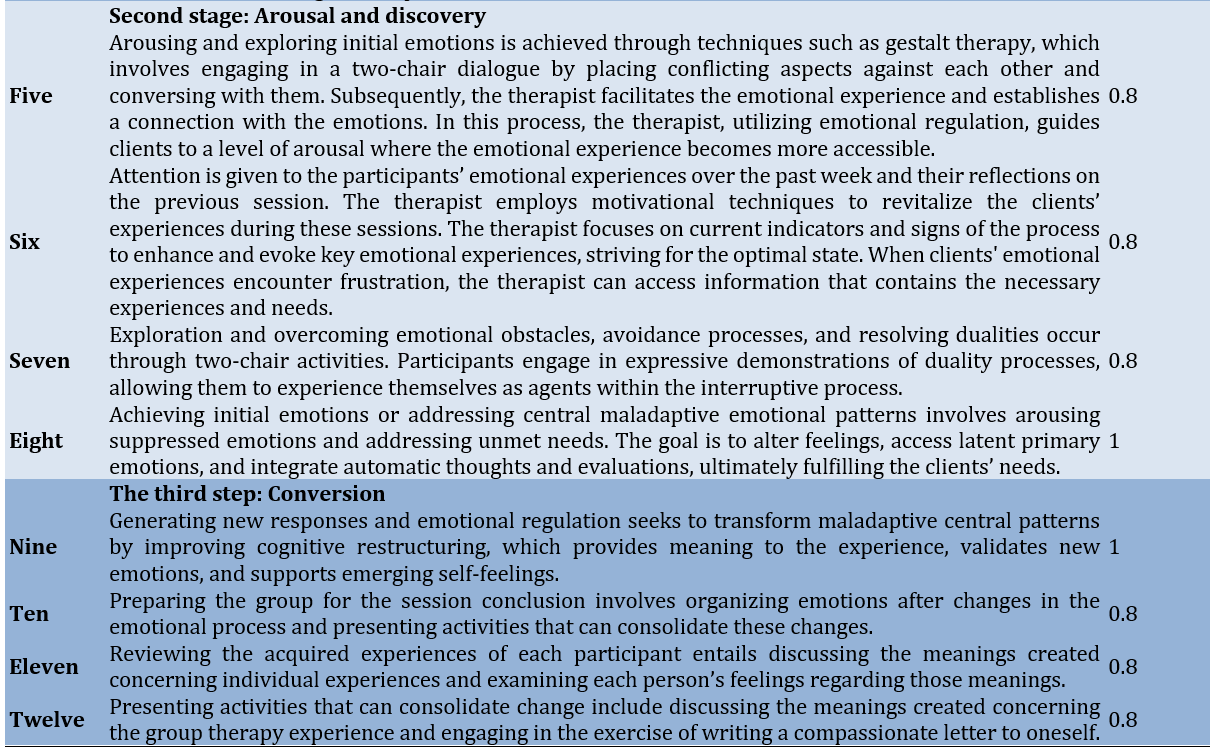

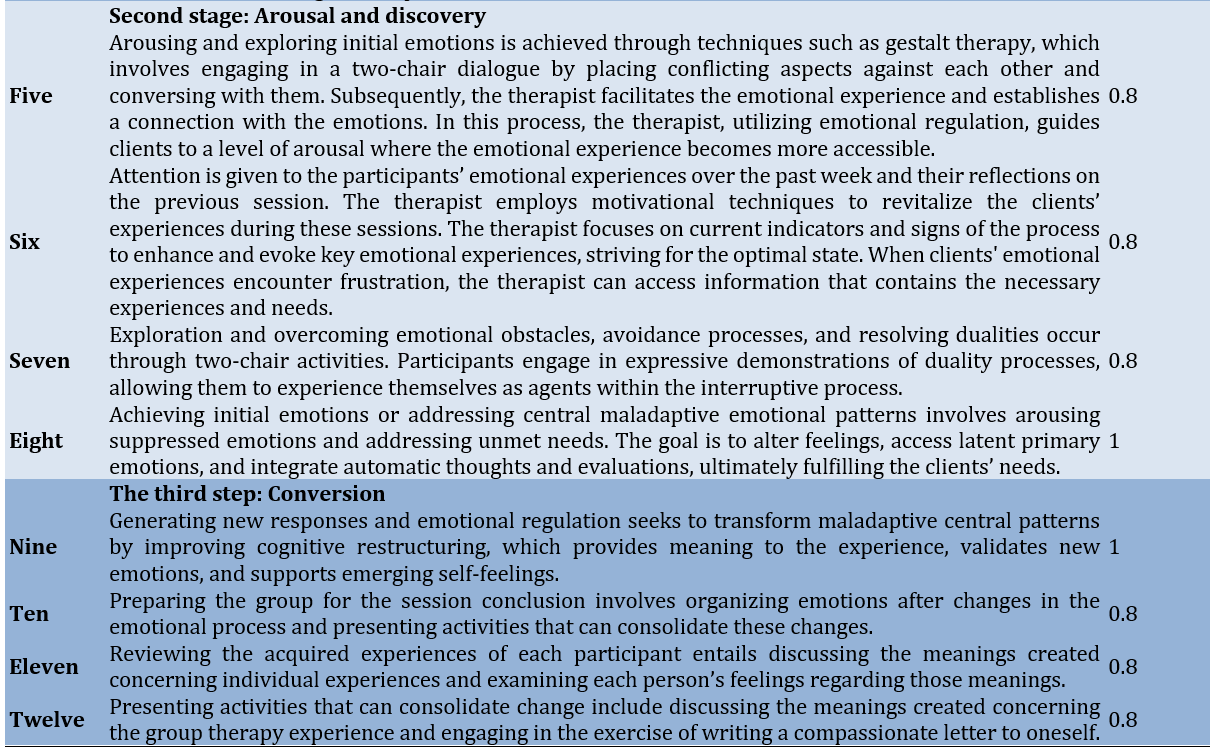

The average age of participants was 37.30±5.92 and 36.30±5.27 years, with the mean number of years since divorce being 3.60±6.50 and 1.83±6.60 years in the experimental and control groups, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of demographic characteristics of the groups

The results indicated no significant differences between the groups in terms of educational attainment, employment status, and familial responsibilities, suggesting that the study’s findings were not confounded by these factors. Similarly, age and time since divorce did not differ significantly between the groups, indicating a well-matched sample that allows for the observed effects to be attributed more confidently to the interventions rather than to underlying demographic differences.

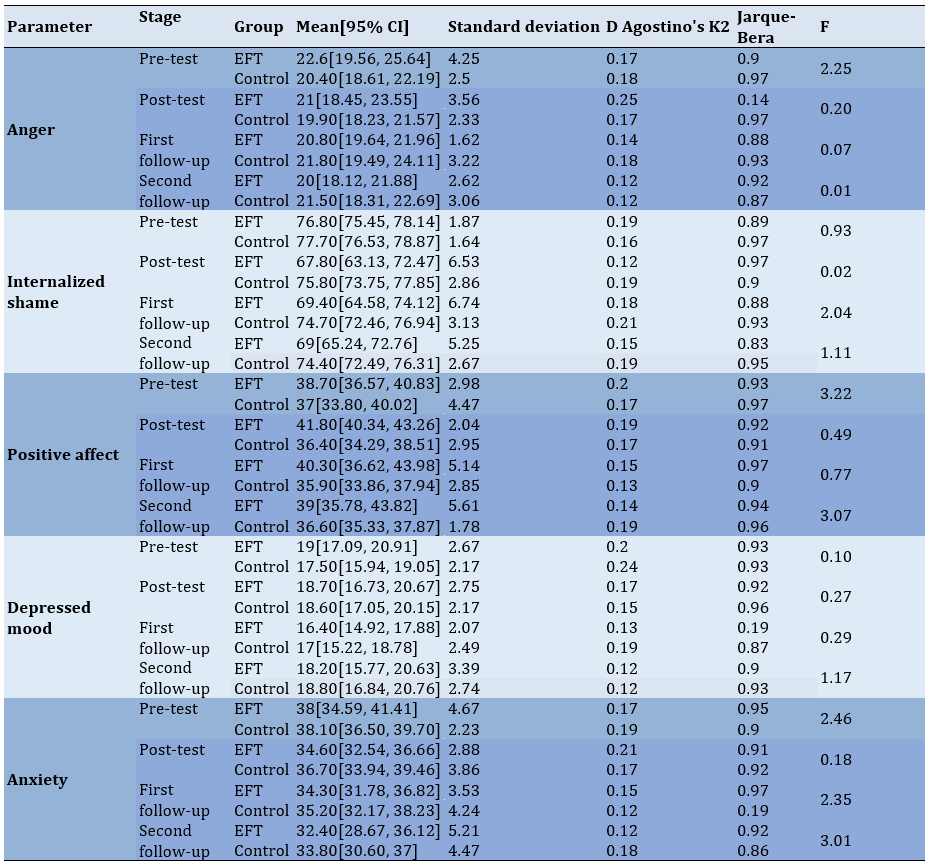

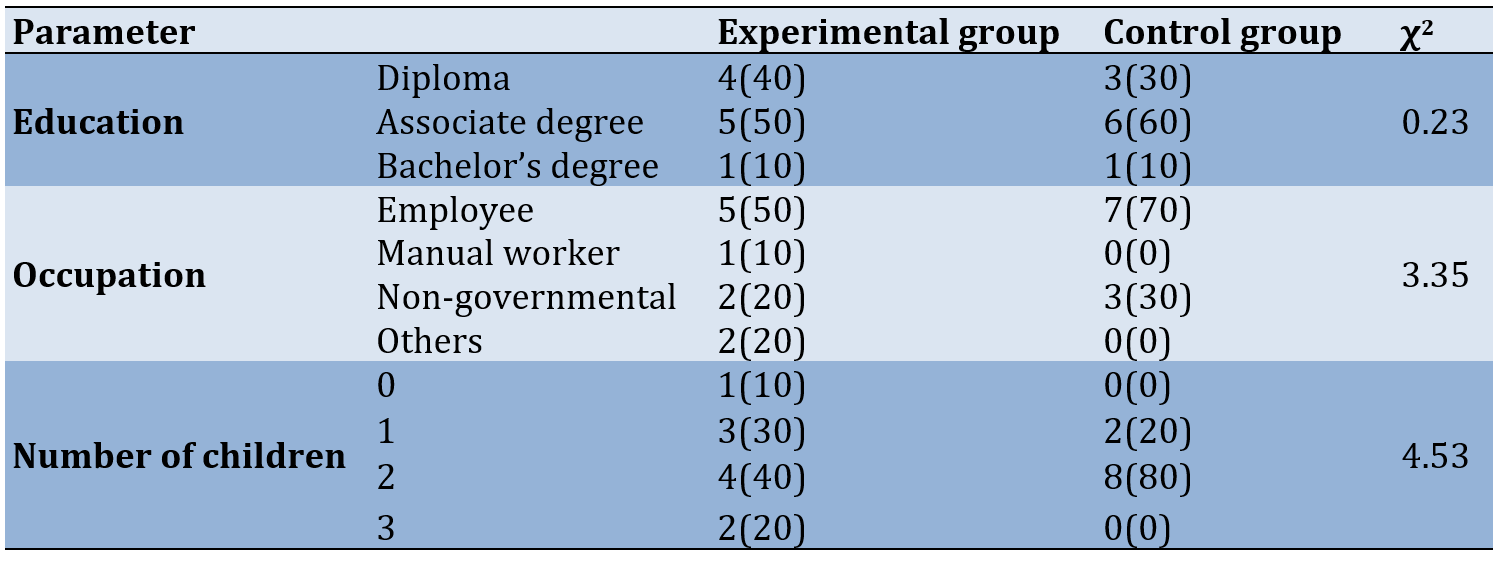

The statistical analysis of anger, depressed mood, anxiety, positive affect, and internalized shame, was comprehensively conducted at the pre-test, post-test, and follow-ups at one and three months (Table 3).

Table 3. Statistical analysis of research parameters between the emotion-focused therapy and control groups at different stages

Statistical tests confirmed the normal distribution of all parameters across both groups and at all measurement stages, supporting the robustness of the subsequent analyses. Additionally, the homogeneity of variances, as evaluated by Levene’s test, was found to be non-significant, allowing for the assumption of equal variances across groups.

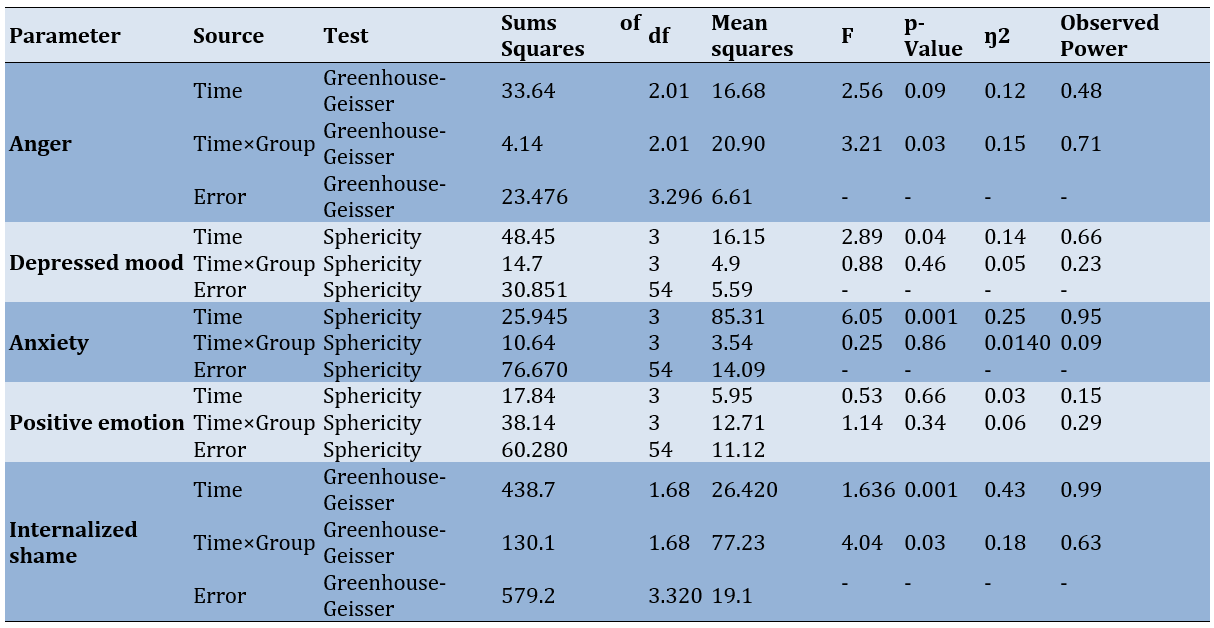

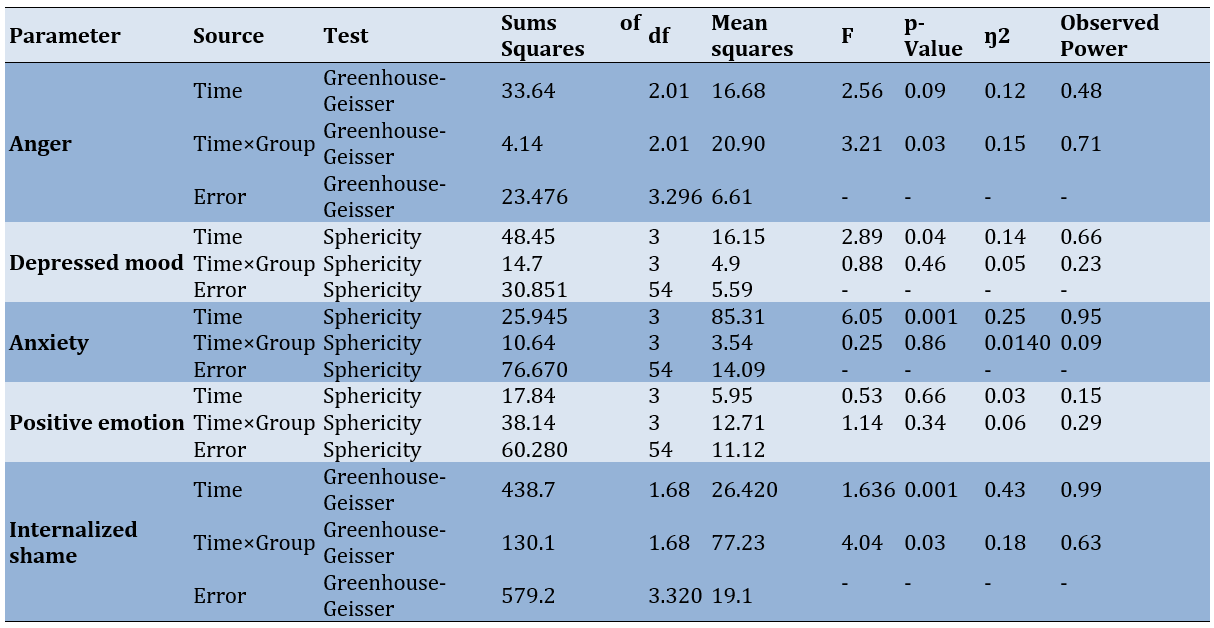

To address the issue of sphericity, which was not met for some parameters, adjustments were made using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction to ensure the validity of the results. These corrections are critical as they affect the interpretation of the data, particularly in understanding how the intervention influenced the participants across the different stages of measurement.

The assumption of sphericity, which is critical for the validity of repeated measures ANOVA, was thoroughly tested using Mauchly’s test of sphericity for each parameter studied (depressed mood, anxiety, and positive emotion). The results indicated that the assumption of sphericity was satisfied for them (p-values for depressed mood=0.87, anxiety=0.06, and positive emotion=0.64), confirming that the variances of the differences between all combinations of related group means were equal; we used standard ANOVA without adjustments for degrees of freedom.

By confirming sphericity, the data analysis for these parameters did not require corrections, such as Greenhouse-Geisser or Huynh-Feldt, which are typically employed when the sphericity assumption is violated. This assurance of sphericity allows for a more straightforward interpretation of the within-group time effects, which assess changes over the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up periods.

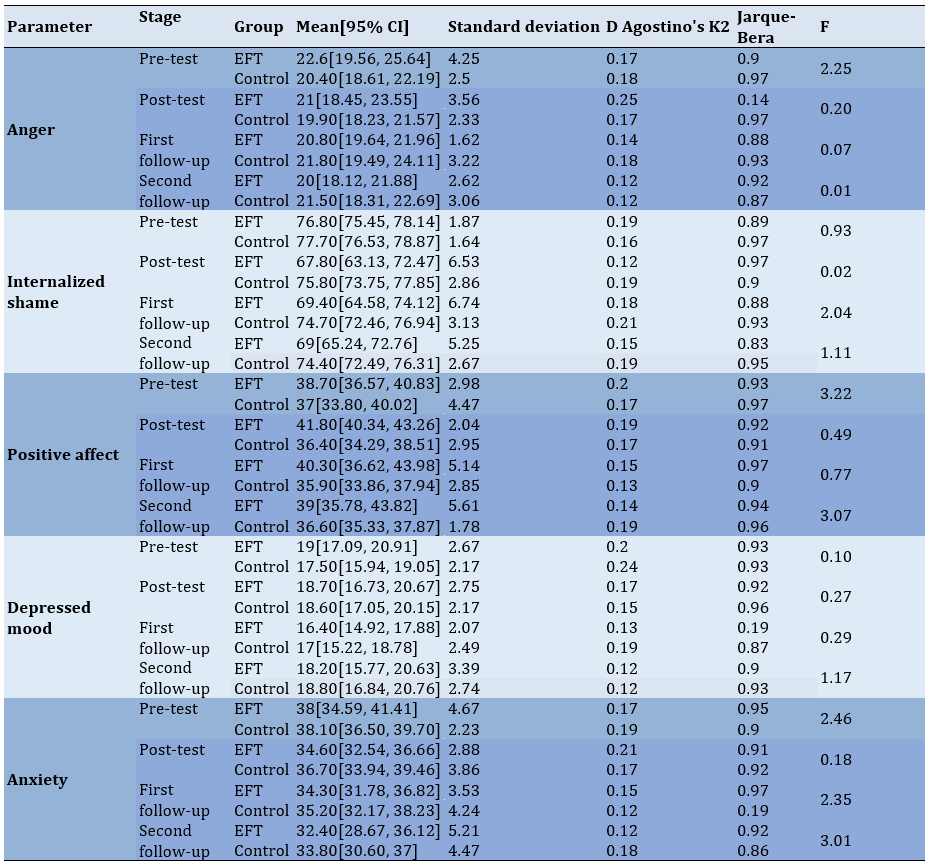

Table 4. The results of the within-group effects regarding emotion control

The tests applied varied based on the assumption of sphericity, and Mauchly’s test confirmed its validity for depressed mood, anxiety, and positive emotion, allowing for the use of standard parametric approaches. The findings from the repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant time effects for certain parameters, indicating that the intervention had measurable impacts throughout the study. Notably, while the main effect of time did not show significance for anger, the interaction between time and group was significant, suggesting that the changes in anger levels differed between the experimental and control groups. For depressed mood, anxiety, and internalized shame, significant main effects of time were observed, demonstrating substantial changes across the testing periods. Additionally, the interaction effect for internalized shame was significant, highlighting differences in how this parameter responded to the interventions between groups.

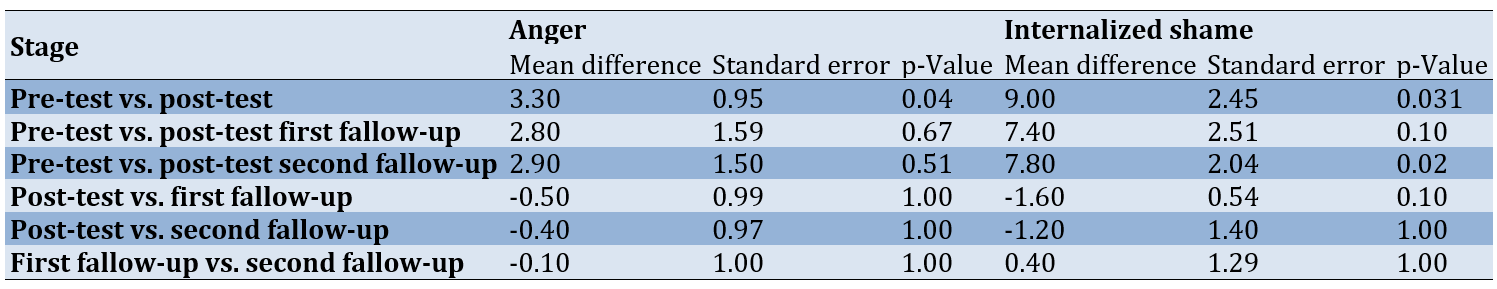

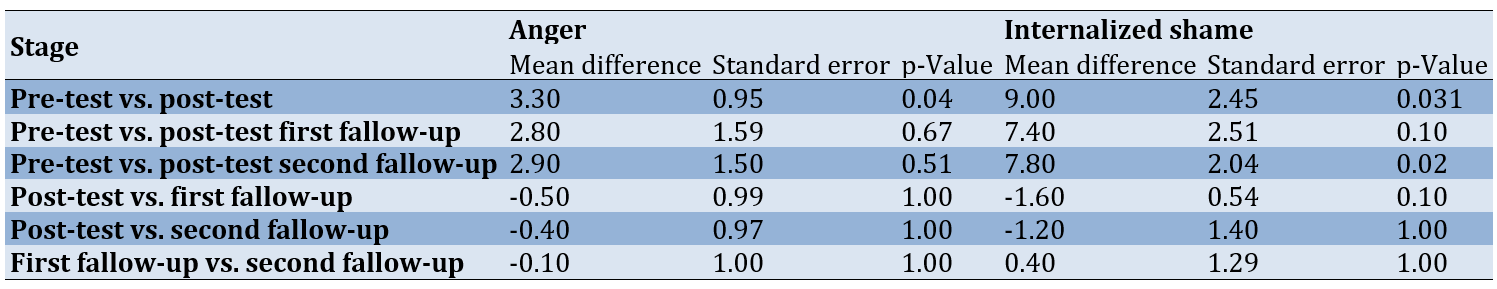

Following the significant main effects observed within the experimental group for anger and internalized shame, further analyses were conducted to explore the pairwise differences across measurement stages using the Bonferroni post hoc test. The Bonferroni post hoc tests demonstrated key differences in the mean scores for anger and internalized shame at various stages. Notably, for anger, significant reductions were observed from the pre-test to the post-test stage, indicating an effective decrease in anger levels immediately following the intervention. For internalized shame, the analyses revealed significant reductions from the pre-test stage to both the post-test and the second follow-up stage (Table 5).

Table 5. Bonferroni's post hoc test results for pairwise comparison of the mean internalized shame anger in the experimental group

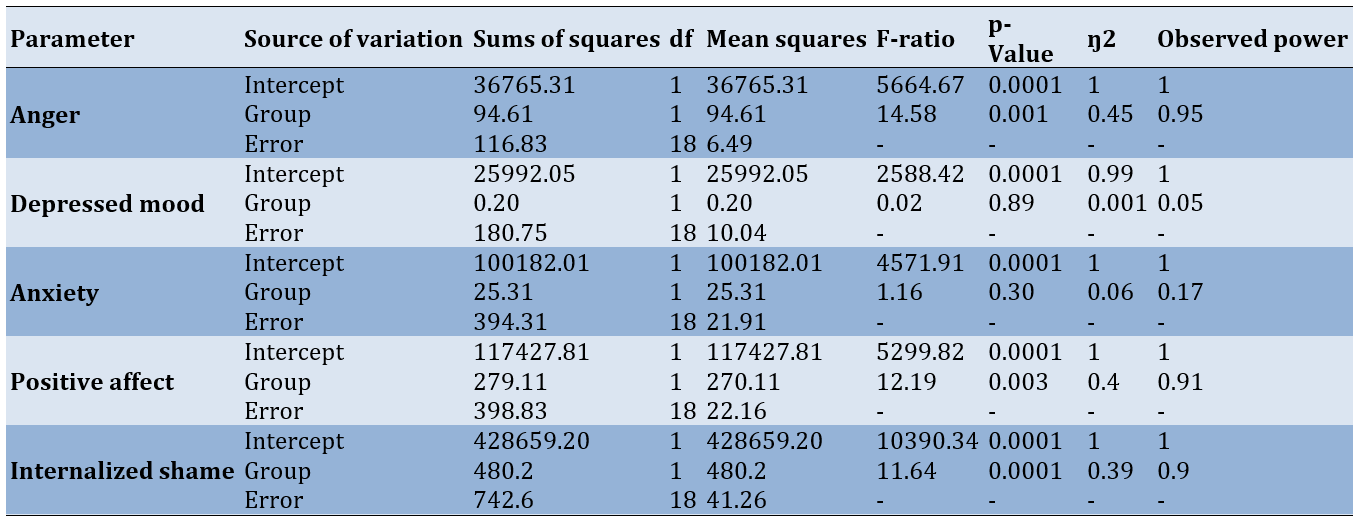

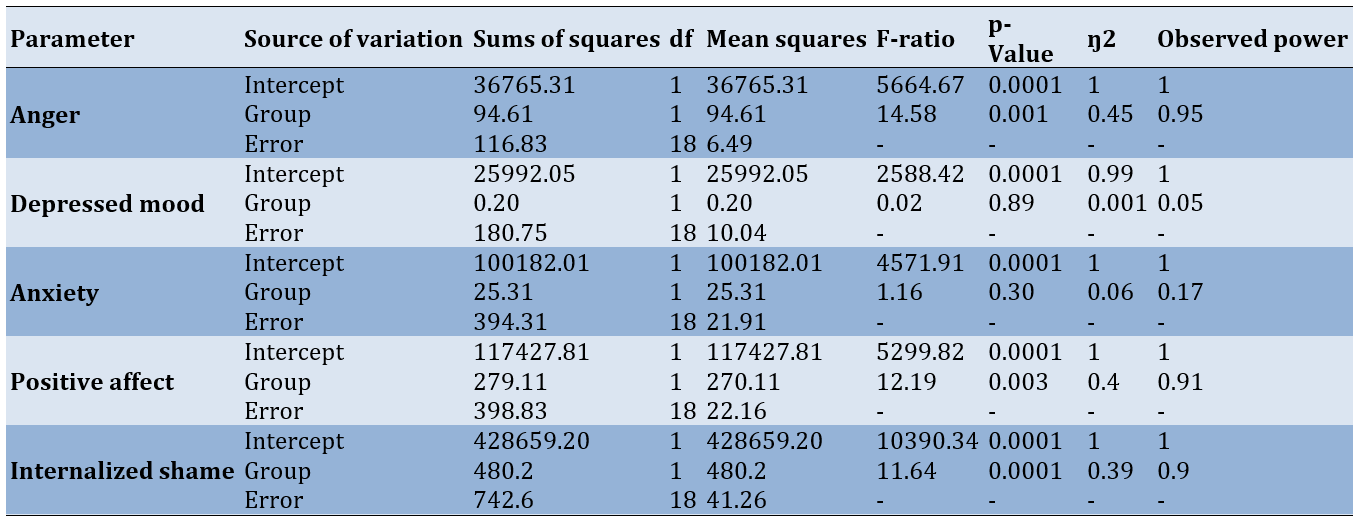

The analysis revealed significant effects of the intervention on certain emotion regulation outcomes. Notably, the intervention significantly influenced anger, positive emotion, and internalized shame, demonstrating clear benefits in these areas compared to the control group. Conversely, the interventions did not yield significant changes in depressed mood and anxiety. This suggests that while the treatments were effective for some aspects of emotion regulation, they did not significantly alter levels of depression or anxiety between the experimental and control groups. These findings highlight the differential impact of the interventions on various emotional outcomes and underscore the importance of targeted approaches for specific emotional challenges. The significant improvements in anger, positive affect, and internalized shame suggest that the interventions were particularly effective in enhancing aspects of emotional strength and resilience among participants (Table 6).

Table 6. Results of variance analysis of between-subject effects in emotion control

Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of emotion-focused group therapy on emotion regulation in divorced women, focusing on anger, positive affect, and internalized shame. The results indicated significant differences between the groups concerning anger, positive emotion, and internalized shame. However, no significant differences were observed between the groups regarding depressed mood and anxiety. This suggests that EFT was not effective in addressing anxiety and depressed mood but was effective in addressing anger, positive emotion, and internalized shame. In this regard, the research findings align with the results of studies by Fülep et al. [64] regarding the effectiveness of this approach in affective control and are consistent with the research conducted by Miratashi Yazdi et al. [65].

In the realm of consonance, the research results align with the study by Fülep et al. [64], which emphasizes the arousal and exploration of primary emotions, as well as the identification of obstacles to emotional experiences to facilitate a more suitable emotional experience. Moreover, regarding effectiveness in emotion control, one can refer to the techniques of emotion identification and acceptance used by Miratashi Yazdi et al. [65], which are similar to the techniques employed in this approach. These techniques include teaching emotion regulation strategies, focusing on the present moment, identifying the foundational needs of each emotion, and utilizing information derived from each emotion to address underlying needs.

However, the findings of this research do not align with the studies conducted by Mottaghi et al. [43] and Fülep et al. [64] regarding the effectiveness of this approach on depression. The lack of alignment between the results of the present study and these studies can be attributed to the analytical approach employed due to their focus solely on depression. Consequently, in therapeutic sessions, the entire therapeutic focus has been directed exclusively toward depression, identifying its emotional patterns, inducing changes in emotions related to that, and creating new meanings through it. Since effective influence on depression requires a deeper exploration of the self, and this aspect was not feasible in these therapeutic sessions due to the presence of other parameters, therapeutic changes in this domain were not observed.

In explaining the effectiveness of EFT on anger and positive affect, it is noteworthy that individuals report experiencing less happiness and increased feelings of guilt, irritability, and hopelessness after divorce [6]. Therefore, utilizing this approach appears to be effective, as it addresses emotion regulation through awareness of the emotions experienced in the moment. By focusing on the present and connecting with what is currently happening in the individual’s body, one can become aware of their feelings, emotions, and bodily states. This awareness enables the individual to relate to emotions as face-to-face experiences and accept them without judgment. Greenberg & Goldman [57] believe that emotional awareness is therapeutic in various ways. As individuals become aware of the presence of their emotions, they can recognize and develop the skill of controlling their experienced emotions by identifying and labeling them. Consequently, they can better manage their emotional states rather than allowing their emotions to manage them. As expressed by Greenberg & Goldman [57], emotional awareness is therapeutic in various therapeutic approaches because, through the expression of emotions, individuals become aware of their primary concerns. Subsequently, they identify their needs and are empowered to manage their emotions, seeking help from others when necessary. In these therapy sessions, the aim was to keep emotions alive and accessible to the individual so that if emotion was adaptive, they could benefit from the information and take useful actions aligned with it. If the emotion was maladaptive, interventions were designed to change and transform it. The goal was to make emotions available so that if an emotion was compatible, the individual could derive useful information and take action based on it. If it was incompatible, interventions were implemented to change and transform it, allowing the individual to gain awareness of the emotion, take action to address or improve it, and thereby enhance the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach concerning these two parameters.

In analyzing the effectiveness of this approach on anger, it is noteworthy that when an individual felt anger within the secure group environment, especially towards group members, therapists, and facilitators, and was allowed to symbolize and express that emotion, they were able to recognize and label it. Ultimately, they came to accept the legitimacy of this emotion in situations, such as experiencing betrayal, physical violence, or humiliation (emotions expressed by group members during the experience of divorce). This achievement led to a sense of agency in responding to the aroused emotion. In other words, individuals realized that this feeling belonged to them, and for the emotion generated within them, they needed to take action to address it or fulfill a corresponding need. Considering that having a sense of agency generally leads to a sense of control over oneself and relationships, the effectiveness of this approach on this parameter can be justified based on the reasons mentioned.

In analyzing the effectiveness of the EFT in positive emotion, one can refer to the fundamental nature of the group. The group sessions were built on the principle that individuals with shared experiences and common challenges would participate, creating an environment where individuals could not only see themselves in the experience of divorce and the emotions it aroused for them but also how they defined themselves in the aftermath of these events. Additionally, since one of the components of this therapeutic approach is addressing attachment wounds, the therapist fostered a sense of belonging among individuals by creating an authentic space and encouraging acceptance among members. This sense of belonging, along with being accepted by others and normalizing one’s experiences in a larger context of shared experiences, contributed to a better sense of self. It led to the creation of new meanings, such as the non-uniqueness of the divorce experience, the right to be loved by others despite experiencing divorce, and acceptance from peers. Consequently, the therapist made this therapy effective for this parameter.

Regarding the impact of the EFT on internalized shame, it can be stated that, in group therapy sessions, efforts were made to expand emotional processing according to the four fundamental principles of this approach, including increasing emotional awareness, expanding emotion regulation, deepening emotional experience, and transforming emotion. Individuals were encouraged to become aware of the shame they felt, to acknowledge the experience of such a distressing emotion, and to learn, with the help of the therapist in the safe environment of the sessions, to recognize their feelings and attempt to deeply embrace their emotions. In this context, individuals’ bodies guided their emotional experiences, allowing them to become aware of their feelings based on what was happening inside their bodies (bodily experience). Moreover, during group sessions, individuals also came to understand that the emotion of shame is not terrifying and, in addition, that this emotion may not be enduring. Therefore, they learned to understand the information that this emotion aimed to convey to them rather than avoiding the feeling of shame. Additionally, one of the techniques taught to individuals in these sessions was the self-compassion technique. This technique helped members replace the feeling of shame, which led to the avoidance of social situations, with a sense of belonging and self-worth. It allowed individuals to develop awareness accompanied by compassion for their struggles, which had affected their quality of life. This increased individuals’ coping abilities with unpleasant feelings such as shame, ultimately leading to an improved quality of life. Furthermore, the ability to cultivate self-compassion is one of the factors that contribute to creating secure attachments in individuals, promoting mental health, and reducing feelings of shame in the experimental group.

Additionally, it should be noted that, in many cases, depression and anxiety in divorced women may be related to external factors, such as inappropriate interactions with close individuals, facing criticism, financial problems, feelings of loneliness, and similar issues. While addressing internal emotions related to these problems, identifying them, and providing training in emotion regulation techniques could contribute to moderating these two variables, it is important to consider that these are mood parameters. Treating mood parameters requires a long time for resolution and demonstrating stability in changes, which may lead to a reduction in therapeutic outcomes during follow-up periods.

This study had some limitations. Some intervening parameters, such as socio-economic status and uncontrolled intelligence, were not accounted for and possibly affected the research outcomes. Also, given that the EFT elicits a set of unresolved emotions, it was not feasible to address all invoked emotions during these sessions. Only the emotions explicitly mentioned were considered as research parameters.

Considering the identification of loneliness and low emotional resilience in divorced women based on participants’ reports of expressed emotions in group therapy sessions, future researchers are encouraged to explore these two parameters as fundamental feelings experienced by divorced women in this context. It is also suggested that a study be conducted on the effectiveness of group therapy based on emotion for divorced men, with the results compared to those of the present study. Combining emotion-focused interventions with other approaches, such as meaning-centered therapy—due to its emphasis on creating meaning in each painful emotional encounter—is proposed for both women and men following divorce. In addition, future researchers are recommended to replicate this study using a single-subject baseline method. Furthermore, as practical suggestions, The findings of this research can contribute to the development of an effective educational program. Given the scarcity of workshops titled “Understanding Emotions, Acceptance, and Emotion Regulation in Divorced Women,” the results of this study can be instrumental in creating a training program for individuals who have experienced divorce. To utilize EFT for reducing internal shame, it is recommended to employ this intervention for divorced women in counseling centers. The use of this therapeutic approach is suggested to instill a sense of agency in regulating emotions, such as anger, fostering positivity, and addressing internalized shame in divorced women.

Conclusion

The EFT approach effectively reduces self-criticism, anger, positive mood, and internalized shame in divorced women.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the participants who willingly contributed their time and shared their experiences for this study. We also extend our thanks to the Hal-e-Khoub Counseling Center in Tehran’s District 3 for invaluable support and cooperation throughout the course of this project. We appreciate the center’s staff for assistance and dedication, which significantly enhanced both the execution and quality of our research.

Ethical Permissions: This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education (IR.UT.PSYEDU.REC.1401.033). Before participating, all participants provided informed consent, acknowledging that their participation was voluntary and that their data would be treated confidentially. To ensure their privacy, pseudonyms will be used in all documents and records. Participants were informed that they could request additional help or clarification if they experienced any discomfort during or after the interview.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Fatourehchi Sh (First Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Keshavarz Afshar H (Second Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Masoud Asadi M (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Aslani Kh (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (20%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any financial support from any organization.

Marriage significantly influences individuals’ roles and developmental trajectories [1]. It not only provides numerous benefits, such as reduced stress and increased happiness [2, 3], but also impacts occupational and mental health indirectly through marital satisfaction [1]. However, instability in marriages is prevalent globally, often leading to divorce and its associated adversities, including high-conflict separations [4-6].

Divorce typically results from unmet expectations and disparities in resource exchange between spouses, which have increased globally over recent decades [7, 8]. This rise in divorces jeopardizes family mental health and leads to loss of attachment, diminished social support, and increased negative thoughts [3, 9].

The effects of divorce are particularly severe for women, who often experience greater economic hardships and psychological stress while managing the majority of post-divorce challenges, including custody and a reduced likelihood of remarriage [9-11]. This often results in heightened anxiety, stress, depression, lower adaptability, and decreased happiness [12-17]. Studies have identified significant emotional regulation challenges among divorced women, marked by increased psychological disturbances and reduced affective control [18-20].

Emotion regulation is crucial for managing stress and maintaining mental health, playing a key role in personal development, ethical behavior, and interpersonal relationships [21-23]. Difficulties in emotion regulation can make stressors appear more threatening, which is pivotal in the development of stress-related symptoms [24, 25]. Furthermore, the post-divorce adaptation process is often emotionally painful, affecting the capacity to regulate emotions such as anger, depression, anxiety, positive emotions, and internal shame [26].

Anger, a natural response to unmet expectations, can vary in intensity, and if mismanaged, may lead to psychological issues [27]. Research highlights that improper anger management is a significant factor contributing to increased depression and mental exhaustion [28, 29]. Additionally, post-divorce, many women report heightened unhappiness, depression, and anxiety, underscoring the need for emotional support [30-34].

Studies have also considered positive mood and internalized shame, with positive emotions being crucial for well-being and negative emotions, like shame having profound impacts on mental health following divorce [35-41]. Addressing these emotional challenges is essential, and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) has been identified as an effective approach. EFT helps individuals navigate their emotional landscape post-divorce, enhancing emotional awareness and coping mechanisms [42-46].

Extensive research supports EFT’s effectiveness in improving emotional and mental health across various demographics [47-52]. However, there is a gap in its application to emotion regulation and internalized shame among divorced women in Iran, which necessitates further study [53-55]. This research aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of EFT in helping divorced women in Iran regulate their emotions and adapt post-divorce, potentially informing therapeutic practices and policy decisions.

Materials and Methods

Participants and design

This quasi-experimental study utilized a pre-test-post-test design with follow-up assessments at one and three months, and was conducted at a designated counseling center during the first half of 2022. The statistical population included all women visiting a designated counseling center during the first half of 2022 and were recruited through a purposeful sampling method. The sample size was calculated using PASS software, aiming for an 80% power and a 0.05 alpha level. Practical considerations and references to prior studies [56] led to the selection of 16 participants, who were then randomly assigned into two groups of eight; an experimental group receiving EFT and a control group. Both groups were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

Inclusion criteria included no diagnosed mental disorders as per the SCL-90-R questionnaire, a minimum average score on the self-criticism questionnaire, being divorced for at least six months, being aged between 20 and 45, having no concurrent psychotherapy sessions, and having no prior engagement in psychotherapy or psychiatry. Participants also needed to provide informed consent.

The intervention consisted of an EFT conducted by a researcher and a facilitator, both trained in introductory and advanced levels of this therapeutic approach. The therapy sessions were followed by post-tests administered in the final session and subsequent follow-ups after one and three months. Following the study, the control group received the same EFT from late March to early June 2023, maintaining ethical standards.

The content validity of the therapeutic protocol was assessed using the content validity ratio (CVR), as outlined by Lawshe in 1975. Ten field experts evaluated the relevance of each session’s content and exercises using a three-part Likert scale (essential, useful but not essential, and not necessary). The required minimum CVR value was 0.62, while the obtained CVR was 0.86, indicating robust content validity.

The detailed content of the therapy sessions and the resources utilized were critically examined for alignment with the study’s objectives and theoretical underpinnings, ensuring a high standard of intervention fidelity.

The format of the EFT sessions adhered to the guidelines of Greenberg & Goldman [57] and Thompson & Girz [58], consisting of 12 steps (sessions), each lasting 120 minutes. These sessions were conducted with a facilitator and involved a trial group comprising ten participants (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of group emotional therapy sessions

Research tools

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by the researcher to collect information related to the demographic characteristics of the population. It included questions regarding specific demographic details, such as the duration since divorce, the absence of prior psychiatric hospitalization due to acute psychological issues, educational level, and age.

Affective Control Scale (ACS)

This scale developed by Williams et al. [59] serves as a tool for assessing individuals’ control and management of their emotions, comprising 42 statements across four sub-scales, including anger (8 items), depressive mood (8 items), anxiety (13 items), and positive affect (13 items). Responses are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (one) to strongly agree (five). Inverted scoring is applied to items 9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 27, 30, 31, and 38. The internal consistency and test-retest reliability for the entire scale are 0.94 and 0.78, respectively; for the anger subscale, they are 0.72 and 0.73, for depressive mood, 0.91 and 0.76, for anxiety, 0.89 and 0.77; and for positive affect, 0.84 and 0.60. Discriminant and convergent validity have been established for a sample of undergraduate students. Additionally, the retest reliability coefficient for the scale after two weeks is 0.78, and for the subscales, it ranges from 0.66 to 0.77 [59]. In a study conducted by Tamborini et al. [15] to assess the validity, reliability, and preliminary standardization of the scale in five groups from the Kermanshah urban community, internal consistency was reported with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.78 for students, 0.82 for university students, 0.89 for teachers, 0.91 for nurses, and 0.94 for professors.

The Internalized Shame Scale (ISS)

This scale, developed by Cook [60], consists of 30 items and two subscales, including 24 items for the inferiority subscale (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, and 30) and six items for the self-esteem subscale (8, 13, 14, 19, 26, and 29). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert-type scale. The scoring is reversed; thus, higher scores on this scale indicate feelings of worthlessness, inadequacy, contempt, emptiness, and loneliness, while lower scores signify higher self-esteem [61]. Cook [60] reported Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the inferiority and self-esteem subscales as 0.94 and 0.90, respectively. Additionally, Rajabi & Abasi [62] reported the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the ISS as 0.90 for the overall sample, 0.89 for males, and 0.91 for females. In the research by Fatolaahzadeh et al. [63], Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was 0.91.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were employed. Inferential statistics, such as independent t-test (continuous parameters), Chi-square test (categorical parameters), and repeated measures ANOVA were utilized to assess the effects of the intervention over time and between groups. The inferential analyses were conducted at a significance level of 0.05 using SPSS 25 software.

Findings

The average age of participants was 37.30±5.92 and 36.30±5.27 years, with the mean number of years since divorce being 3.60±6.50 and 1.83±6.60 years in the experimental and control groups, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of demographic characteristics of the groups

The results indicated no significant differences between the groups in terms of educational attainment, employment status, and familial responsibilities, suggesting that the study’s findings were not confounded by these factors. Similarly, age and time since divorce did not differ significantly between the groups, indicating a well-matched sample that allows for the observed effects to be attributed more confidently to the interventions rather than to underlying demographic differences.

The statistical analysis of anger, depressed mood, anxiety, positive affect, and internalized shame, was comprehensively conducted at the pre-test, post-test, and follow-ups at one and three months (Table 3).

Table 3. Statistical analysis of research parameters between the emotion-focused therapy and control groups at different stages

Statistical tests confirmed the normal distribution of all parameters across both groups and at all measurement stages, supporting the robustness of the subsequent analyses. Additionally, the homogeneity of variances, as evaluated by Levene’s test, was found to be non-significant, allowing for the assumption of equal variances across groups.

To address the issue of sphericity, which was not met for some parameters, adjustments were made using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction to ensure the validity of the results. These corrections are critical as they affect the interpretation of the data, particularly in understanding how the intervention influenced the participants across the different stages of measurement.

The assumption of sphericity, which is critical for the validity of repeated measures ANOVA, was thoroughly tested using Mauchly’s test of sphericity for each parameter studied (depressed mood, anxiety, and positive emotion). The results indicated that the assumption of sphericity was satisfied for them (p-values for depressed mood=0.87, anxiety=0.06, and positive emotion=0.64), confirming that the variances of the differences between all combinations of related group means were equal; we used standard ANOVA without adjustments for degrees of freedom.

By confirming sphericity, the data analysis for these parameters did not require corrections, such as Greenhouse-Geisser or Huynh-Feldt, which are typically employed when the sphericity assumption is violated. This assurance of sphericity allows for a more straightforward interpretation of the within-group time effects, which assess changes over the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up periods.

Table 4. The results of the within-group effects regarding emotion control

The tests applied varied based on the assumption of sphericity, and Mauchly’s test confirmed its validity for depressed mood, anxiety, and positive emotion, allowing for the use of standard parametric approaches. The findings from the repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant time effects for certain parameters, indicating that the intervention had measurable impacts throughout the study. Notably, while the main effect of time did not show significance for anger, the interaction between time and group was significant, suggesting that the changes in anger levels differed between the experimental and control groups. For depressed mood, anxiety, and internalized shame, significant main effects of time were observed, demonstrating substantial changes across the testing periods. Additionally, the interaction effect for internalized shame was significant, highlighting differences in how this parameter responded to the interventions between groups.

Following the significant main effects observed within the experimental group for anger and internalized shame, further analyses were conducted to explore the pairwise differences across measurement stages using the Bonferroni post hoc test. The Bonferroni post hoc tests demonstrated key differences in the mean scores for anger and internalized shame at various stages. Notably, for anger, significant reductions were observed from the pre-test to the post-test stage, indicating an effective decrease in anger levels immediately following the intervention. For internalized shame, the analyses revealed significant reductions from the pre-test stage to both the post-test and the second follow-up stage (Table 5).

Table 5. Bonferroni's post hoc test results for pairwise comparison of the mean internalized shame anger in the experimental group

The analysis revealed significant effects of the intervention on certain emotion regulation outcomes. Notably, the intervention significantly influenced anger, positive emotion, and internalized shame, demonstrating clear benefits in these areas compared to the control group. Conversely, the interventions did not yield significant changes in depressed mood and anxiety. This suggests that while the treatments were effective for some aspects of emotion regulation, they did not significantly alter levels of depression or anxiety between the experimental and control groups. These findings highlight the differential impact of the interventions on various emotional outcomes and underscore the importance of targeted approaches for specific emotional challenges. The significant improvements in anger, positive affect, and internalized shame suggest that the interventions were particularly effective in enhancing aspects of emotional strength and resilience among participants (Table 6).

Table 6. Results of variance analysis of between-subject effects in emotion control

Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of emotion-focused group therapy on emotion regulation in divorced women, focusing on anger, positive affect, and internalized shame. The results indicated significant differences between the groups concerning anger, positive emotion, and internalized shame. However, no significant differences were observed between the groups regarding depressed mood and anxiety. This suggests that EFT was not effective in addressing anxiety and depressed mood but was effective in addressing anger, positive emotion, and internalized shame. In this regard, the research findings align with the results of studies by Fülep et al. [64] regarding the effectiveness of this approach in affective control and are consistent with the research conducted by Miratashi Yazdi et al. [65].

In the realm of consonance, the research results align with the study by Fülep et al. [64], which emphasizes the arousal and exploration of primary emotions, as well as the identification of obstacles to emotional experiences to facilitate a more suitable emotional experience. Moreover, regarding effectiveness in emotion control, one can refer to the techniques of emotion identification and acceptance used by Miratashi Yazdi et al. [65], which are similar to the techniques employed in this approach. These techniques include teaching emotion regulation strategies, focusing on the present moment, identifying the foundational needs of each emotion, and utilizing information derived from each emotion to address underlying needs.

However, the findings of this research do not align with the studies conducted by Mottaghi et al. [43] and Fülep et al. [64] regarding the effectiveness of this approach on depression. The lack of alignment between the results of the present study and these studies can be attributed to the analytical approach employed due to their focus solely on depression. Consequently, in therapeutic sessions, the entire therapeutic focus has been directed exclusively toward depression, identifying its emotional patterns, inducing changes in emotions related to that, and creating new meanings through it. Since effective influence on depression requires a deeper exploration of the self, and this aspect was not feasible in these therapeutic sessions due to the presence of other parameters, therapeutic changes in this domain were not observed.

In explaining the effectiveness of EFT on anger and positive affect, it is noteworthy that individuals report experiencing less happiness and increased feelings of guilt, irritability, and hopelessness after divorce [6]. Therefore, utilizing this approach appears to be effective, as it addresses emotion regulation through awareness of the emotions experienced in the moment. By focusing on the present and connecting with what is currently happening in the individual’s body, one can become aware of their feelings, emotions, and bodily states. This awareness enables the individual to relate to emotions as face-to-face experiences and accept them without judgment. Greenberg & Goldman [57] believe that emotional awareness is therapeutic in various ways. As individuals become aware of the presence of their emotions, they can recognize and develop the skill of controlling their experienced emotions by identifying and labeling them. Consequently, they can better manage their emotional states rather than allowing their emotions to manage them. As expressed by Greenberg & Goldman [57], emotional awareness is therapeutic in various therapeutic approaches because, through the expression of emotions, individuals become aware of their primary concerns. Subsequently, they identify their needs and are empowered to manage their emotions, seeking help from others when necessary. In these therapy sessions, the aim was to keep emotions alive and accessible to the individual so that if emotion was adaptive, they could benefit from the information and take useful actions aligned with it. If the emotion was maladaptive, interventions were designed to change and transform it. The goal was to make emotions available so that if an emotion was compatible, the individual could derive useful information and take action based on it. If it was incompatible, interventions were implemented to change and transform it, allowing the individual to gain awareness of the emotion, take action to address or improve it, and thereby enhance the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach concerning these two parameters.

In analyzing the effectiveness of this approach on anger, it is noteworthy that when an individual felt anger within the secure group environment, especially towards group members, therapists, and facilitators, and was allowed to symbolize and express that emotion, they were able to recognize and label it. Ultimately, they came to accept the legitimacy of this emotion in situations, such as experiencing betrayal, physical violence, or humiliation (emotions expressed by group members during the experience of divorce). This achievement led to a sense of agency in responding to the aroused emotion. In other words, individuals realized that this feeling belonged to them, and for the emotion generated within them, they needed to take action to address it or fulfill a corresponding need. Considering that having a sense of agency generally leads to a sense of control over oneself and relationships, the effectiveness of this approach on this parameter can be justified based on the reasons mentioned.

In analyzing the effectiveness of the EFT in positive emotion, one can refer to the fundamental nature of the group. The group sessions were built on the principle that individuals with shared experiences and common challenges would participate, creating an environment where individuals could not only see themselves in the experience of divorce and the emotions it aroused for them but also how they defined themselves in the aftermath of these events. Additionally, since one of the components of this therapeutic approach is addressing attachment wounds, the therapist fostered a sense of belonging among individuals by creating an authentic space and encouraging acceptance among members. This sense of belonging, along with being accepted by others and normalizing one’s experiences in a larger context of shared experiences, contributed to a better sense of self. It led to the creation of new meanings, such as the non-uniqueness of the divorce experience, the right to be loved by others despite experiencing divorce, and acceptance from peers. Consequently, the therapist made this therapy effective for this parameter.

Regarding the impact of the EFT on internalized shame, it can be stated that, in group therapy sessions, efforts were made to expand emotional processing according to the four fundamental principles of this approach, including increasing emotional awareness, expanding emotion regulation, deepening emotional experience, and transforming emotion. Individuals were encouraged to become aware of the shame they felt, to acknowledge the experience of such a distressing emotion, and to learn, with the help of the therapist in the safe environment of the sessions, to recognize their feelings and attempt to deeply embrace their emotions. In this context, individuals’ bodies guided their emotional experiences, allowing them to become aware of their feelings based on what was happening inside their bodies (bodily experience). Moreover, during group sessions, individuals also came to understand that the emotion of shame is not terrifying and, in addition, that this emotion may not be enduring. Therefore, they learned to understand the information that this emotion aimed to convey to them rather than avoiding the feeling of shame. Additionally, one of the techniques taught to individuals in these sessions was the self-compassion technique. This technique helped members replace the feeling of shame, which led to the avoidance of social situations, with a sense of belonging and self-worth. It allowed individuals to develop awareness accompanied by compassion for their struggles, which had affected their quality of life. This increased individuals’ coping abilities with unpleasant feelings such as shame, ultimately leading to an improved quality of life. Furthermore, the ability to cultivate self-compassion is one of the factors that contribute to creating secure attachments in individuals, promoting mental health, and reducing feelings of shame in the experimental group.

Additionally, it should be noted that, in many cases, depression and anxiety in divorced women may be related to external factors, such as inappropriate interactions with close individuals, facing criticism, financial problems, feelings of loneliness, and similar issues. While addressing internal emotions related to these problems, identifying them, and providing training in emotion regulation techniques could contribute to moderating these two variables, it is important to consider that these are mood parameters. Treating mood parameters requires a long time for resolution and demonstrating stability in changes, which may lead to a reduction in therapeutic outcomes during follow-up periods.

This study had some limitations. Some intervening parameters, such as socio-economic status and uncontrolled intelligence, were not accounted for and possibly affected the research outcomes. Also, given that the EFT elicits a set of unresolved emotions, it was not feasible to address all invoked emotions during these sessions. Only the emotions explicitly mentioned were considered as research parameters.

Considering the identification of loneliness and low emotional resilience in divorced women based on participants’ reports of expressed emotions in group therapy sessions, future researchers are encouraged to explore these two parameters as fundamental feelings experienced by divorced women in this context. It is also suggested that a study be conducted on the effectiveness of group therapy based on emotion for divorced men, with the results compared to those of the present study. Combining emotion-focused interventions with other approaches, such as meaning-centered therapy—due to its emphasis on creating meaning in each painful emotional encounter—is proposed for both women and men following divorce. In addition, future researchers are recommended to replicate this study using a single-subject baseline method. Furthermore, as practical suggestions, The findings of this research can contribute to the development of an effective educational program. Given the scarcity of workshops titled “Understanding Emotions, Acceptance, and Emotion Regulation in Divorced Women,” the results of this study can be instrumental in creating a training program for individuals who have experienced divorce. To utilize EFT for reducing internal shame, it is recommended to employ this intervention for divorced women in counseling centers. The use of this therapeutic approach is suggested to instill a sense of agency in regulating emotions, such as anger, fostering positivity, and addressing internalized shame in divorced women.

Conclusion

The EFT approach effectively reduces self-criticism, anger, positive mood, and internalized shame in divorced women.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the participants who willingly contributed their time and shared their experiences for this study. We also extend our thanks to the Hal-e-Khoub Counseling Center in Tehran’s District 3 for invaluable support and cooperation throughout the course of this project. We appreciate the center’s staff for assistance and dedication, which significantly enhanced both the execution and quality of our research.

Ethical Permissions: This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education (IR.UT.PSYEDU.REC.1401.033). Before participating, all participants provided informed consent, acknowledging that their participation was voluntary and that their data would be treated confidentially. To ensure their privacy, pseudonyms will be used in all documents and records. Participants were informed that they could request additional help or clarification if they experienced any discomfort during or after the interview.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Fatourehchi Sh (First Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Keshavarz Afshar H (Second Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Masoud Asadi M (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Aslani Kh (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (20%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any financial support from any organization.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2024/05/12 | Accepted: 2024/08/28 | Published: 2024/09/9

Received: 2024/05/12 | Accepted: 2024/08/28 | Published: 2024/09/9

References

1. Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Research on marital satisfaction and stability in the 2010s: Challenging conventional wisdom. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(1):100-16. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12635]

2. Huang YT, Chen MH, Hu HF, Ko NY, Yen CF. Role of mental health in the attitude toward same-sex marriage among people in Taiwan: Moderating effects of gender, age, and sexual orientation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(1):150-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jfma.2019.03.011]

3. Chen MW, Rybak C. Group leadership skills: Interpersonal process in group counseling and therapy. Washington DC: Sage Publications; 2017. [Link] [DOI:10.4135/9781071800980]

4. Whisman MA, Salinger JM, Sbarra DA. Relationship dissolution and psychopathology. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:199-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.016]

5. Lin IF, Brown SL. Consequences of later‐life divorce and widowhood for adult well‐being: A call for the convalescence model. J Fam Theory Rev. 2020;12(2):264-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jftr.12366]

6. Pellón I, Martínez-Pampliega A, Cormenzana S. Post-divorce adjustment, coparenting and somatisation: Mediating role of anxiety and depression in high-conflict divorces. J Affect Disord Rep. 2024;16:100697. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100697]

7. Khataybeh YDA. The consequences of divorce on women: An exploratory study of divorced women problems in Jordan. J Divorce Remarriage. 2022;63(5):332-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2022.2046396]

8. Sands A, Thompson EJ, Gaysina D. Long-term influences of parental divorce on offspring affective disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;218:105-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.015]

9. Raley RK, Sweeney MM. Divorce, repartnering, and stepfamilies: A decade in review. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(1):81-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12651]

10. Cavapozzi D, Fiore S, Pasini G. Divorce and well-being. Disentangling the role of stress and socio economic status. J Econ Ageing. 2020;16:100212. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jeoa.2019.100212]

11. Parker G, Durante KM, Hill SE, Haselton MG. Why women choose divorce: An evolutionary perspective. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:300-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.020]

12. Hald GM, Ciprić A, Sander S, Strizzi JM. Anxiety, depression and associated factors among recently divorced individuals. J Ment Health. 2022;31(4):462-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09638237.2020.1755022]

13. Srinivasan M, Reddy MM, Sarkar S, Menon V. Depression, anxiety, and stress among rural south Indian women-prevalence and correlates: A community-based study. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2020;11(1):78-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1700595]

14. Nahar JS, Algin S, Sajib MWH, Ahmed S, Arafat SY. Depressive and anxiety disorders among single mothers in Dhaka. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(5):485-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0020764020920671]

15. Tamborini CR, Couch KA, Reznik GL. Long-term impact of divorce on women's earnings across multiple divorce windows: A life course perspective. Adv Life Course Res. 2015;26:44-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.alcr.2015.06.001]

16. Dereje W. The causes and psychosocial impacts of divorce on women: The case of Ethiopian Women Lawyers' Association (EWLA) supported women [dissertation]. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2014. [Link]

17. Murray D. The impact of divorce on work performance of professional nurses in the tertiary hospitals of the buffalo city municipality [dissertation]. Dikeni: University of Fort Hare; 2012. [Link]

18. Beckmann L. Does parental warmth buffer the relationship between parent-to-child physical and verbal aggression and adolescent behavioural and emotional adjustment?. J Fam Stud. 2021;27(3):366-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13229400.2019.1616602]

19. Derella OJ, Burke JD, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE. Reciprocity in undesirable parent-child behavior? Verbal aggression, corporal punishment, and girls' oppositional defiant symptoms. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2020;49(3):420-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2019.1603109]

20. Smarius LJ, Strieder TG, Doreleijers TA, Vrijkotte TG, Zafarmand MH, De Rooij SR. Maternal verbal aggression in early infancy and child's internalizing symptoms: Interaction by common oxytocin polymorphisms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;270(5):541-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00406-019-01013-0]

21. Hesse C, Rauscher EA, Goodman RB, Couvrette MA. Reconceptualizing the role of conformity behaviors in family communication patterns theory. J Fam Commun. 2017;17(4):319-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15267431.2017.1347568]

22. Li MN, Ren YL, Liu LJ, Cheng MH, Di Q, Chang HJ, et al. The effect of emotion regulation on empathic ability in Chinese nursing students: The parallel mediating role of emotional intelligence and self-consistency congruence. Nurse Educ Pract. 2024;75:103882. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2024.103882]

23. Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59(2-3):73-100. [Link] [DOI:10.2307/1166139]

24. Meuleman EM, Van Der Veld WM, Van Ee E. On the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms during treatment: A test of reciprocity. J Affect Disord. 2024;350:197-202. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.116]

25. Sarvandani MN, Moghadam NK, Moghadam HK, Asadi M, Rafaiee R, Soleimani M. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) treatment on anxiety, depression and prevention of substance use relapse. Int J Health Stud. 2021;7(2):12-6. [Link]

26. Steiner LM, Durand S, Groves D, Rozzell C. Effect of infidelity, initiator status, and spiritual well-being on men's divorce adjustment. J Divorce Remarriage. 2015;56(2):95-108. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10502556.2014.996050]

27. Aldemir S, Yiğitoğlu GT. The relation between sleep quality and anger expression that occur in nurses: A cross-sectional study. J Radiol Nurs. 2024;43(1):60-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jradnu.2023.10.003]

28. Spengler PM, Lee NA, Wiebe SA, Wittenborn AK. A comprehensive meta-analysis on the efficacy of emotionally focused couple therapy. Couple Fam Psychol Res Pract. 2024;13(2):81-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/cfp0000233]

29. Afshani SA, Abooei A, Asihaddad F. The relationship between aggression and quality of life of couples seeking divorce. Payesh. 2024;23(1):91-100. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.61186/payesh.23.1.91]

30. Nzabonimpa E, Richters A, Rutayisire E. Social isolation among genocide ex-prisoners in Rwanda: A mixed method study of prevalence and associated factors. Intervention. 2024;22(1):44-52. [Link]

31. Yamaguchi A, Kim MS. Effects of self-criticism and its relationship with depression across cultures. Int J Psychol Stud. 2013;5(1):1. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v5n1p1]

32. Breslau J, Miller E, Jin R, Sampson N, Alonso J, Andrade L, et al. A multinational study of mental disorders, marriage, and divorce. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(6):474-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01712.x]

33. Amato PR, Hohmann‐Marriott B. A comparison of high‐and low‐distress marriages that end in divorce. J Marriage Fam. 2007;69(3):621-38. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00396.x]

34. Seekis V, Kennedy R. The impact of #beauty and #self-compassion tiktok videos on young women's appearance shame and anxiety, self-compassion, mood, and comparison processes. Body Image. 2023;45:117-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.02.006]

35. Kord-Zanganeh J, Ghasemi-Ardahaee A. Consequences of divorce for divorced women with emphasize on the socio-demographic factors: A study in Ahvaz City, Iran. J Popul Assoc Iran. 2023;18(35):363-92. [Persian] [Link]

36. Dal Fabbro D, Catissi G, Borba G, Lima L, Hingst-Zaher E, Rosa J, et al. e-Nature Positive Emotions Photography Database (e-NatPOEM): Affectively rated nature images promoting positive emotions. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11696. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-91013-9]

37. Mansoori S, Mahdavi F, Behjati Ardakani F, Bagheri F, Niroumand Sarvandani M. Empowering healthcare workers: Insight from an interpretive structural model for educational needs in Iran. Health Educ Health Promot. 2023;11(4):569-79. [Link]

38. Matos M, Pinto-Gouveia J, Gilbert P, Duarte C, Figueiredo C. The other as shamer scale-2: Development and validation of a short version of a measure of external shame. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;74:6-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.037]

39. Kim S, Thibodeau R, Jorgensen RS. Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(1):68-96. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0021466]

40. Orth U, Robins RW, Soto CJ. Tracking the trajectory of shame, guilt, and pride across the life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99(6):1061-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0021342]

41. Abebe YM. Lived experiences of divorced women in rural Ethiopia. A special focus in Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda: Addis Zemen Kebele. Int J Polit Sci Dev. 2015;3(6):268-81. [Link]

42. Ochsner KN. From the self to the social regulation of emotion: An evolving psychological and neural model. In: Neta M, Haas IJ, editors. Emotion in the mind and body. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 43-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-27473-3_3]

43. Mottaghi S, Shameli L, Honarkar R. The efficiency of emotion-focused terapy on depression, hope for the future and interpersonal trust of the devorced women. J Psychol Stud. 2019;14(4):107-22. [Persian] [Link]

44. Goldman RN, Greenberg LS, Angus L. The effects of adding emotion-focused interventions to the client-centered relationship conditions in the treatment of depression. Psychother Res. 2006;16(5):536-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10503300600589456]

45. Kailanko S, Wiebe SA, Tasca GA, Laitila AA. Somatic interventions and depth of experiencing in emotionally focused couple therapy. Int J Syst Ther. 2022;33(2):109-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/2692398X.2022.2041346]

46. Asadi M, Ghasemzadeh N, Nazarifar M, Sarvandani MN. The effectiveness of emotion-focused couple therapy on marital satisfaction and positive feelings towards the spouse. Int J Health Stud. 2020;6(4). [Link]

47. McNally S, Timulak L, Greenberg LS. Transforming emotion schemes in emotion focused therapy: A case study investigation. Pers Cent Exp Psychother. 2014;13(2):128-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14779757.2013.871573]

48. Allan R. The use of emotionally focused therapy with separated or divorced couples. Can J Couns Psychother. 2016;50(3s). [Link]

49. Güdücü N, Özcan NK. The effect of emotional freedom techniques (EFT) on postpartum depression: A randomized controlled trial. Explore. 2023;19(6):842-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.explore.2023.04.012]

50. Khadem Dezfuli Z, Alavi SZ, Shahbazi M. The effectiveness of emotion focused therapy on alexithymia and idealistic marital expectation in perfectionism neurotic girls. Biannu J Appl Couns. 2024;14(1):1-20. [Persian] [Link]

51. Amini M, Lotfi M, Fatemitabar R, Bahrampoori L. The effectiveness of emotion-focused group therapy on the reduction of negative emotions and internet addiction symptoms. Pract Clin Psychol. 2020;8(1):1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.8.1.1]

52. Millard L, Wan MW, Smith D, Wittkowski A. The effectiveness of compassion focused therapy with clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;326:168-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.010]

53. Gregory Jr VL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for relationship distress: Meta-analysis of RCTs with social work implications. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2021;18(1):49-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/26408066.2020.1806164]

54. Sanaei H, Hadianfard H, Goodarzi MA, Akbari A, Akbari ME. A comparative evaluation of the effect of group-based cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy on emotion regulation in women with breast cancer. J Adv Pharm Educ Res. 2020;10(S1):208-16. [Link]

55. Oei TPS, Dingle G. The effectiveness of group cognitive behaviour therapy for unipolar depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1-3):5-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.018]

56. Brennan MA, Emmerling ME, Whelton WJ. Emotion-focused group therapy: Addressing self-criticism in the treatment of eating disorders. Couns Psychother Res. 2014. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14733145.2014.914549]

57. Greenberg LS, Goldman RN, editors. Clinical handbook of emotion-focused therapy. Washington DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2019. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0000112-000]

58. Thompson S, Girz L. Taming your critic: A practical guide to EFT in group settings. Transforming Emotions. 2018. [Link]

59. Williams KE, Chambless DL, Ahrens A. Are emotions frightening? An extension of the fear of fear construct. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(3):239-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00098-8]

60. Cook DR. Measuring shame: The internalized shame scale. In: The treatment of shame and guilt in alcoholism counseling. New York: Routledge; 2013. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t04998-000]

61. Hojatkhah SM, Mesbah I. Effectiveness of group therapy based on acceptance and commitment on social adjustment and internalized shame mothers of children with mental retardation. 2017;6(24):153-80. [Persian] [Link]

62. Rajabi Gh, Abasi Gh. An investigation of relationship between self-criticism, social interaction anxiety, and fear of failure with internalized shame in students. Res Clin Psychol Couns. 2012;1(2):171-82. [Persian] [Link]

63. Fatolaahzadeh N, Majlesi Z, Mazaheri Z, Rostami M, Navabinejad S. The effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy with internalized shame and self-criticism on emotionally abused women. Q J Psychol Stud. 2017;13(2):151-68. [Persian] [Link]

64. Fülep M, Pilárik Ľ, Novák L, Mikoška P. The effectiveness of emotion-focused therapy: A systematic review of experimental studies. Československá Psychol. 2021;65(5):459-73. [Czech] [Link] [DOI:10.51561/cspsych.65.5.459]

65. Miratashi Yazdi MS, Mollazadeh's J, Aflakseir A, Sarafraz MR. The effectiveness of emotion-focused therapy on internalized and external shame in people with social anxiety. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2023;10(6):51-63. [Persian] [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |