Volume 12, Issue 3 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(3): 415-421 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Samkhaniani N, Lotfi Kashani F, Vaziri S. Comparing the Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness Intervention in Diabetes Self-Care of Depressed Women. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (3) :415-421

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-74970-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-74970-en.html

1- Department of Health Psychology, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Gestational Diabetes [MeSH], Mindfulness [MeSH], Cognitive Therapy [MeSH], Self-Care [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 592 kb]

(2712 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1252 Views)

Full-Text: (264 Views)

Introduction

When pregnant women are diagnosed with diabetes in the latter half of pregnancy, they often perceive it as an unexpected event, as they had anticipated a normal pregnancy process. This diagnosis initiates significant changes across various life domains, encompassing bodily alterations, intimate relationships, work commitments, financial concerns, and social interactions. Moreover, the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus substantially amplifies the psychological burden, as many women experience feelings of guilt and fear regarding the health of their unborn child [1]. Many pregnant women perceive diabetes treatment as intrusive and culturally unacceptable. Adapting to late changes in diet can be emotionally exhausting for them, particularly when faced with the immediate need to adjust to this condition [2]. Comprehending and integrating the complex information presented during diagnosis is very difficult and troublesome for compliance. Some women conceal their diagnosis to maintain their idealized image as perfect mothers [3]. This situation justifies the expansion of psychological interventions in the care of pregnant women, especially when it is associated with multiple diagnoses.

The global prevalence of gestational diabetes is reported to be 14.2%, while in the Middle East, it stands at 28.4% [4]. According to Delpisheh et al. [5], the nationwide prevalence of gestational diabetes in Iran is 9.7%. Based on the American Diabetes Association, gestational diabetes is defined as occurring in pregnant women who were not diagnosed with diabetes before pregnancy but typically have elevated blood glucose levels, usually around the twenty-fourth week of pregnancy [6]. Gestational diabetes is considered a transient condition; however, it carries long-term consequences, such as an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease for the mother. Additionally, it is associated with an increased risk of obesity and subsequent gestational diabetes for the child [7, 8]. Moreover, the incidence of depression in gestational diabetes ranges from 22% to 43% [9], which requires greater attention to the potential for additional depression in pregnant individuals.

Treatment and prevention of diabetes largely depend on the patient’s willingness to engage in self-care practices. Self-care encompasses a set of behaviors undertaken independently by individuals to maintain and enhance their health. Controlling blood glucose levels and preventing complications of gestational diabetes are among the primary objectives of self-care in gestational diabetes. Studies have shown that self-care is associated with improved metabolic control, better blood glucose levels, and increased self-efficacy in patients with diabetes. The obligation to self-care entails many challenges in patients’ lives, making it necessary to implement appropriate interventions [10].

Diabetes control involves implementing a comprehensive self-care program. This program typically includes blood glucose monitoring, weight management, physical activity, medication adherence, foot care, and dietary management. Self-care activities are often laborious and require fundamental lifestyle changes. Although many patients are aware of the consequences of non-adherence to self-care, they are unable to fully comply with it. This situation increases the complications related to the disease [11].

The psychological problems of pregnant women, particularly the psychological condition of those with gestational diabetes, a high-risk group, have attracted the attention of researchers worldwide. Studies conducted in this population indicate that apart from physiological factors, anxiety, and depression are significant contributors to gestational diabetes [12]. The increased risk of gestational diabetes in pregnant women and the diagnosis of this condition may elevate the risk of prepartum or postpartum depression [13]. The high prevalence of depression among diabetic patients and the potential negative consequences of the disorder emphasize the necessity for effective treatments aimed at improving quality of life [14] and diabetes management.

Psychotherapy reduces the need for costly medical services and is an effective factor for health [15]. Therefore, designing efficient interventions based on psychotherapeutic approaches for chronic diseases, especially gestational diabetes, is of particular importance. Many psychotherapy approaches have been devised to address health-related problems, among which mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are particularly practical and noteworthy. There is limited research history comparing these two methods in the context of gestational diabetes, especially when it is accompanied by depression.

Mindfulness is a form of non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of present experiences, a skill that allows individuals to engage with events with less distress in the present moment [16, 17]. In a study aimed at determining the effectiveness of mindfulness on depression in pregnant individuals, it was found that mindfulness interventions based on stress reduction help improve depression symptoms [18]. According to a systematic review that examined the effect of mindfulness on the self-care of women, mindfulness reduces anxiety, depression, and stress during pregnancy. Because of the low-risk nature of these interventions, all women should be encouraged to practice mindfulness during pregnancy [19].

The hypothesis that thoughts, behaviors, emotions, and physiology combine to influence diabetes management has been well accepted. Therefore, cognitive therapy-based interventions can increase patients’ awareness of the relationship between glucose control and negative thoughts, behaviors, and emotions in diabetes. This may also help patients develop better self-care behaviors and achieve improved blood glucose control [20, 21].

Individuals with gestational diabetes receiving an intensive cognitive-behavioral self-care intervention, including diabetes education, frequent blood glucose monitoring, and daily use of a personalized dietary plan for individuals with diabetes, exhibit a significant improvement in blood glucose control and cardiovascular health indicators [22]. The findings of another study aimed at determining the effectiveness of CBT and meaning-centered therapy on diabetic patients indicated that CBT can reduce depressive symptoms in individuals with diabetes. Additionally, the findings of a case study suggest that CBT can be integrated into diabetes management concerning mental health, physical health, and self-care behaviors [23]. Based on the research background, the present study aimed to compare the effect of CBT and mindfulness intervention on diabetic self-care of depressed women with gestational diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on depressed women with gestational diabetes attending healthcare centers in Ray County affiliated with Tehran University from September to December 2023. Depression was diagnosed based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 [24] and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), conducted by a senior clinical psychologist. The sample size was determined considering a test power of 0.80, a confidence level of 0.95, an anticipated large effect size of 0.70, and a dropout rate of 10%. Using convenience sampling, 45 participants were selected based on similar studies [25, 26] and using a table of random numbers randomly assigned into three groups, including CBT (n=15), mindfulness (n=15), and control (n=15). Gestational diabetes was diagnosed based on a physician’s assessment. All participants received self-care training based on the national protocol for gestational diabetes. Participants read and completed the informed consent forms. Before the intervention, a pre-test was conducted for all participants. Each of the mindfulness and CBT groups received eight sessions of 60 minutes each, twice a week. Immediately after the interventions, a post-test was conducted for all participants, and a follow-up was performed after one month.

The inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 40 years, a pregnancy term of 24-28 weeks, and minimum literacy skills. A simultaneous diagnosis of gestational diabetes and major depression was required. The exclusion criteria included absence from therapy sessions for more than 2 sessions, receiving psychotropic medication, undergoing concurrent or recent psychotherapy within the past year, facing major unforeseen stressors such as bereavement or divorce during the study, and having any type of concurrent illness that interferes with the treatment process.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Scale (SDSCA): SDSCA, developed by Toobert et al. [27], serves as a brief and valid instrument for evaluating diabetes self-management. It is beneficial for both research and clinical purposes. It assesses self-reported activities related to dietary regimen, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, and insulin injection frequency. It consists of 15 items, with responses rated on an eight-point Likert scale. Except for smoking behavior, which is scored as zero or one, each item is scored from zero to seven. The total adherence score is obtained by summing the scores of each item. Higher scores in each domain and the overall questionnaire indicate better self-care practices. The reliability of this questionnaire was evaluated by Kordi et al. [28], with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.70.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): This scale was developed by Cox et al. [29], and consists of ten items rated on a four-point scale ranging from zero to three. The minimum score is zero, and the maximum score is 30. This questionnaire is a valid instrument for assessing depression [30]. Internal consistency was found to be 0.80, indicating item consistency for diagnosis. The questionnaire also exhibits appropriate content validity, with a total content validity of 0.98 and content validity for each item exceeding 0.70 [31]. In a study conducted by Ahmadi Kani Golzar & Gholizadeh [32], it was found that this test possesses a suitable level of reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.70. The internal consistency of the test was 0.80, and a cutoff point of 13 was determined.

Mindfulness intervention: This intervention was designed based on the methods by Kabat-Zinn [33] and Segal et al. [34]. Throughout eight sessions, participants engaged in a structured mindfulness program designed to enhance their awareness and self-care practices. In the first session, participants were introduced to mindfulness through exercises focused on eating, such as the raisin exercise. They practiced bringing attention to the present moment through meditation on bodily sensations. The second session involved further exploration of mindfulness through body scan meditation and focusing on the breath. Participants practiced mindfulness despite distractions or obstacles. In the third session, mindfulness was incorporated into movement with exercises that emphasized conscious breathing and stretching. Sitting meditation focused on breath and body awareness was also introduced. The fourth session emphasized staying present amidst various stimuli, including sounds and thoughts. Walking meditation was introduced, and participants learned to utilize mindfulness during difficult emotions. The fifth session focused on cultivating acceptance and allowing participants to experience thoughts and emotions without judgment. They explored difficult emotions through meditation and examined their effects. In the sixth session, participants learned to recognize thoughts as mental events rather than absolute truths and explored the impact of thoughts on the body and mind. The seventh session emphasized self-care through mindfulness practices, and participants planned how to manage arising difficulties mindfully. In the final session, participants applied mindfulness techniques to cope with future emotional challenges and reviewed and integrated what they had learned throughout the program.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy: This treatment manual is adapted from White [35]. The first meeting established communication and initial understanding, specified goals, identified negative thoughts about diabetes and gestational diabetes, and emphasized the importance of completing homework between sessions. The second session evaluated participants’ knowledge about gestational diabetes and taught the cognitive-behavioral approach to understanding diabetes, its symptoms, and complications. Spontaneous thoughts regarding gestational diabetes were identified, and homework included studying the provided gestational diabetes pamphlet. The third session encouraged participants to express their stress, concerns, and factors causing anxiety related to gestational diabetes. Stress management techniques, including relaxation methods and breathing exercises, were taught. Homework involved daily relaxation exercises for ten minutes and recording stress levels along with the skills used in stress management. In the fourth session, the technique of “how thoughts create emotions” was employed to address negative thoughts and beliefs causing negative emotions in pregnant women. Participants discussed food groups, dietary considerations for women with gestational diabetes, and changes they could make in their eating behavior. Homework included completing a table for recording events, thoughts, and feelings, as well as documenting negative emotions and the thoughts behind them. Two diet change activities were recorded over two sessions. The fifth session discussed physical activities during pregnancy, types of permitted sports for mothers with gestational diabetes, and the importance of family support. Techniques for confirming or rejecting beliefs related to gestational diabetes were introduced. Homework included recording a case of self-expression without anger and refraining from daily walking hours. The sixth session involved assessing and identifying concerns and examining the advantages and disadvantages of worrying through group discussion. Theoretical and practical training on insulin injection and glucometer use was provided. Successful mothers in glycemic control were invited to share their experiences. Homework included recording insulin injections and glucometer use during the week. In the seventh session, the main counseling content was reviewed, feedback was given and received, and the extent to which participants achieved their goals was assessed. Finally, positive feedback was provided to members, positive memories were defined, and a follow-up measurement date was determined for one month later. The session ended with the facilitation of ongoing communication between the consultant and clients.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using repeated measures mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) by SPSS software 25 at a significance level of <0.05. Before conducting the ANOVA, its assumptions were examined. To assess the normality of the distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed, which confirmed normal distribution (p>0.05). Levene’s test was used to examine the homogeneity of variances, which was confirmed (p>0.05). However, the assumption of sphericity was not achieved (p<0.01); thus, the Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon correction was applied.

Findings

Forty-five pregnant mothers participated in the study. The mean age of participants in the mindfulness, CBT, and control groups was 27.00±3.10, 26.20±3.50, and 25.60±1.62 years, respectively.

The results of the within-group ANOVA showed significant differences in self-care at different stages in the mindfulness group (F=341.2; p<0.01). According to the Bonferroni post hoc test, a significant increase was observed in self-care scores at the post-test stage compared to the pre-test stage (t=28.36; p<0.01). Additionally, in the follow-up stage, a significant increase in self-care was observed compared to the pre-test stage (t=25.93; p<0.01). However, in the follow-up stage, a significant decrease in self-care was observed compared to the post-test stage (t=2.53; p<0.01).

The results of the within-group ANOVA also showed significant differences in self-care at different stages in the CBT group (F=579.9; p<0.01). According to the Bonferroni test, a significant increase was observed in self-care scores in the post-test stage compared to the pre-test stage (t=14.13; p<0.01). Similarly, the follow-up self-care score also showed a significant increase compared to the pre-test stage (t=13.13; p<0.01). However, there was no significant difference in self-care scores between the post-test and follow-up stages (t=1; p>0.05).

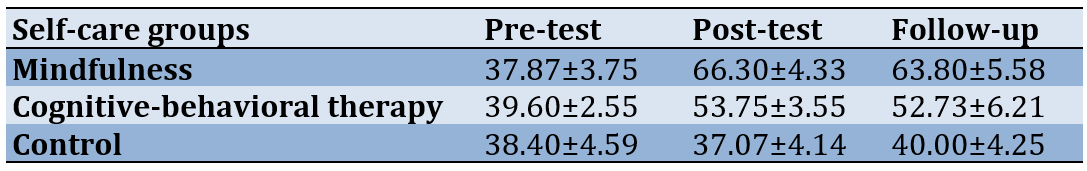

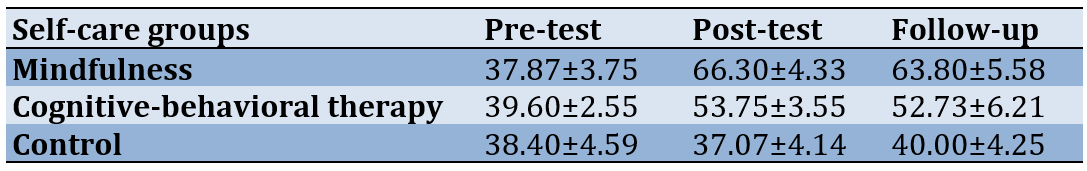

The within-group ANOVA did not show significant differences in self-care scores at different stages in the control group (F=2.11; p>0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Self-care scores in the studied groups

The between-group ANOVA results indicated no significant difference among the three groups at the pre-test stage (F=0.55; p>0.05). However, in the post-test stage, differences between groups became significant (F=199.3; p<0.01). Follow-up examination using the Bonferroni test revealed a significant increase in self-care scores for the mindfulness group compared to the CBT group (t=12; p<0.01). Additionally, the mindfulness group demonstrated a significant increase in self-care score compared to the control group (t=29.26; p<0.01). In the CBT group, a significant increase in self-care was observed compared to the control group (t=16.66; p<0.01).

Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the effect of CBT and mindfulness intervention on diabetic self-care of depressed women with gestational diabetes. Mindfulness showed greater effectiveness than CBT in improving self-care among depressed women with gestational diabetes. Self-care for pregnant mothers is a complex and multifaceted process. They must not only undertake various pregnancy-related care [3] but also manage the added burden of a dual diagnosis (depression and diabetes). Mindfulness can contribute to improving this situation as it enhances attention, active memory, and executive function [22]. Additionally, mindfulness reduces over-generalized autobiographical memory, which is a marker of depression [36]. Focusing on the body is a prime starting point for the mindfulness process and achieving mental health while adhering to self-care directives. Among individuals who had practiced simple meditation in previous studies, a direct relationship between body awareness and health care status was found. Body awareness helps to increase attention regulation, achieve mental health, and reduce anxiety symptoms [37]. Patients with mindfulness abilities are more attuned to the present moment and recognize the importance of participating in self-care activities that protect against diabetes, enabling them to manage their condition more efficiently [38].

CBT also improved diabetes self-care. Optimal control of this multifaceted and chronic condition largely depends on patient adherence to medical appointments and lifestyle changes. Cognitive therapy enhances patients’ awareness of the relationship between glucose control and negative thoughts, behaviors, and emotions regarding diabetes. It also assists patients in more fully engaging in self-care behaviors and achieving better blood sugar control compared to exercise and dietary adherence alone [39]. CBT effectively reduces irrational beliefs and the psychological pressure resulting from these beliefs.

Although mindfulness was more effective in improving self-care among depressed women with gestational diabetes, a noticeable reduction in therapeutic effects was observed during the follow-up phase, while such an effect was not observed for cognitive therapy. These observations suggest the potential for greater durability of therapeutic effects for cognitive therapy. The research history on this specific patient group is limited; however, studies in similar domains indicate that mindfulness-based therapy for depression is more clinically effective and economically advantageous [40].

Each of these two approaches has its own specific mechanism of action. While mindfulness focuses on emotional-cognitive patterns, such as avoidance and rumination [41], CBT concentrates on cognitive processes [42]. Highlighting the specific needs of each patient can assist in selecting the appropriate therapeutic approach. These findings indicate the need for further research, considering that mindfulness maintained greater effectiveness over cognitive therapy during the follow-up phase, although it showed a decreasing trend.

Many parameters were not examined in this study, especially since the current research was conducted in a limited area and did not utilize a random sampling design with a larger sample size. These aspects could be addressed in future research. Also, further research is needed to explore additional parameters and optimize treatment selection for individual patient needs.

Conclusion

While both mindfulness and CBT show promise in enhancing self-care among depressed women with gestational diabetes, mindfulness appears particularly effective in addressing the complex interplay of depression and diabetes management. However, CBT demonstrates the potential for longer-lasting therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all the participants who made this study possible.

Ethical Permissions: The Islamic Azad University, Roudehen Branch approved this study [IR.IAU.REC.1402.020], ensuring compliance with ethical guidelines and standards.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Samkhaniani N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (40%); Lotfi Kashani F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (40%); Vaziri Sh (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This study received no funding.

When pregnant women are diagnosed with diabetes in the latter half of pregnancy, they often perceive it as an unexpected event, as they had anticipated a normal pregnancy process. This diagnosis initiates significant changes across various life domains, encompassing bodily alterations, intimate relationships, work commitments, financial concerns, and social interactions. Moreover, the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus substantially amplifies the psychological burden, as many women experience feelings of guilt and fear regarding the health of their unborn child [1]. Many pregnant women perceive diabetes treatment as intrusive and culturally unacceptable. Adapting to late changes in diet can be emotionally exhausting for them, particularly when faced with the immediate need to adjust to this condition [2]. Comprehending and integrating the complex information presented during diagnosis is very difficult and troublesome for compliance. Some women conceal their diagnosis to maintain their idealized image as perfect mothers [3]. This situation justifies the expansion of psychological interventions in the care of pregnant women, especially when it is associated with multiple diagnoses.

The global prevalence of gestational diabetes is reported to be 14.2%, while in the Middle East, it stands at 28.4% [4]. According to Delpisheh et al. [5], the nationwide prevalence of gestational diabetes in Iran is 9.7%. Based on the American Diabetes Association, gestational diabetes is defined as occurring in pregnant women who were not diagnosed with diabetes before pregnancy but typically have elevated blood glucose levels, usually around the twenty-fourth week of pregnancy [6]. Gestational diabetes is considered a transient condition; however, it carries long-term consequences, such as an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease for the mother. Additionally, it is associated with an increased risk of obesity and subsequent gestational diabetes for the child [7, 8]. Moreover, the incidence of depression in gestational diabetes ranges from 22% to 43% [9], which requires greater attention to the potential for additional depression in pregnant individuals.

Treatment and prevention of diabetes largely depend on the patient’s willingness to engage in self-care practices. Self-care encompasses a set of behaviors undertaken independently by individuals to maintain and enhance their health. Controlling blood glucose levels and preventing complications of gestational diabetes are among the primary objectives of self-care in gestational diabetes. Studies have shown that self-care is associated with improved metabolic control, better blood glucose levels, and increased self-efficacy in patients with diabetes. The obligation to self-care entails many challenges in patients’ lives, making it necessary to implement appropriate interventions [10].

Diabetes control involves implementing a comprehensive self-care program. This program typically includes blood glucose monitoring, weight management, physical activity, medication adherence, foot care, and dietary management. Self-care activities are often laborious and require fundamental lifestyle changes. Although many patients are aware of the consequences of non-adherence to self-care, they are unable to fully comply with it. This situation increases the complications related to the disease [11].

The psychological problems of pregnant women, particularly the psychological condition of those with gestational diabetes, a high-risk group, have attracted the attention of researchers worldwide. Studies conducted in this population indicate that apart from physiological factors, anxiety, and depression are significant contributors to gestational diabetes [12]. The increased risk of gestational diabetes in pregnant women and the diagnosis of this condition may elevate the risk of prepartum or postpartum depression [13]. The high prevalence of depression among diabetic patients and the potential negative consequences of the disorder emphasize the necessity for effective treatments aimed at improving quality of life [14] and diabetes management.

Psychotherapy reduces the need for costly medical services and is an effective factor for health [15]. Therefore, designing efficient interventions based on psychotherapeutic approaches for chronic diseases, especially gestational diabetes, is of particular importance. Many psychotherapy approaches have been devised to address health-related problems, among which mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are particularly practical and noteworthy. There is limited research history comparing these two methods in the context of gestational diabetes, especially when it is accompanied by depression.

Mindfulness is a form of non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of present experiences, a skill that allows individuals to engage with events with less distress in the present moment [16, 17]. In a study aimed at determining the effectiveness of mindfulness on depression in pregnant individuals, it was found that mindfulness interventions based on stress reduction help improve depression symptoms [18]. According to a systematic review that examined the effect of mindfulness on the self-care of women, mindfulness reduces anxiety, depression, and stress during pregnancy. Because of the low-risk nature of these interventions, all women should be encouraged to practice mindfulness during pregnancy [19].

The hypothesis that thoughts, behaviors, emotions, and physiology combine to influence diabetes management has been well accepted. Therefore, cognitive therapy-based interventions can increase patients’ awareness of the relationship between glucose control and negative thoughts, behaviors, and emotions in diabetes. This may also help patients develop better self-care behaviors and achieve improved blood glucose control [20, 21].

Individuals with gestational diabetes receiving an intensive cognitive-behavioral self-care intervention, including diabetes education, frequent blood glucose monitoring, and daily use of a personalized dietary plan for individuals with diabetes, exhibit a significant improvement in blood glucose control and cardiovascular health indicators [22]. The findings of another study aimed at determining the effectiveness of CBT and meaning-centered therapy on diabetic patients indicated that CBT can reduce depressive symptoms in individuals with diabetes. Additionally, the findings of a case study suggest that CBT can be integrated into diabetes management concerning mental health, physical health, and self-care behaviors [23]. Based on the research background, the present study aimed to compare the effect of CBT and mindfulness intervention on diabetic self-care of depressed women with gestational diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on depressed women with gestational diabetes attending healthcare centers in Ray County affiliated with Tehran University from September to December 2023. Depression was diagnosed based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 [24] and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), conducted by a senior clinical psychologist. The sample size was determined considering a test power of 0.80, a confidence level of 0.95, an anticipated large effect size of 0.70, and a dropout rate of 10%. Using convenience sampling, 45 participants were selected based on similar studies [25, 26] and using a table of random numbers randomly assigned into three groups, including CBT (n=15), mindfulness (n=15), and control (n=15). Gestational diabetes was diagnosed based on a physician’s assessment. All participants received self-care training based on the national protocol for gestational diabetes. Participants read and completed the informed consent forms. Before the intervention, a pre-test was conducted for all participants. Each of the mindfulness and CBT groups received eight sessions of 60 minutes each, twice a week. Immediately after the interventions, a post-test was conducted for all participants, and a follow-up was performed after one month.

The inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 40 years, a pregnancy term of 24-28 weeks, and minimum literacy skills. A simultaneous diagnosis of gestational diabetes and major depression was required. The exclusion criteria included absence from therapy sessions for more than 2 sessions, receiving psychotropic medication, undergoing concurrent or recent psychotherapy within the past year, facing major unforeseen stressors such as bereavement or divorce during the study, and having any type of concurrent illness that interferes with the treatment process.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Scale (SDSCA): SDSCA, developed by Toobert et al. [27], serves as a brief and valid instrument for evaluating diabetes self-management. It is beneficial for both research and clinical purposes. It assesses self-reported activities related to dietary regimen, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, and insulin injection frequency. It consists of 15 items, with responses rated on an eight-point Likert scale. Except for smoking behavior, which is scored as zero or one, each item is scored from zero to seven. The total adherence score is obtained by summing the scores of each item. Higher scores in each domain and the overall questionnaire indicate better self-care practices. The reliability of this questionnaire was evaluated by Kordi et al. [28], with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.70.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): This scale was developed by Cox et al. [29], and consists of ten items rated on a four-point scale ranging from zero to three. The minimum score is zero, and the maximum score is 30. This questionnaire is a valid instrument for assessing depression [30]. Internal consistency was found to be 0.80, indicating item consistency for diagnosis. The questionnaire also exhibits appropriate content validity, with a total content validity of 0.98 and content validity for each item exceeding 0.70 [31]. In a study conducted by Ahmadi Kani Golzar & Gholizadeh [32], it was found that this test possesses a suitable level of reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.70. The internal consistency of the test was 0.80, and a cutoff point of 13 was determined.

Mindfulness intervention: This intervention was designed based on the methods by Kabat-Zinn [33] and Segal et al. [34]. Throughout eight sessions, participants engaged in a structured mindfulness program designed to enhance their awareness and self-care practices. In the first session, participants were introduced to mindfulness through exercises focused on eating, such as the raisin exercise. They practiced bringing attention to the present moment through meditation on bodily sensations. The second session involved further exploration of mindfulness through body scan meditation and focusing on the breath. Participants practiced mindfulness despite distractions or obstacles. In the third session, mindfulness was incorporated into movement with exercises that emphasized conscious breathing and stretching. Sitting meditation focused on breath and body awareness was also introduced. The fourth session emphasized staying present amidst various stimuli, including sounds and thoughts. Walking meditation was introduced, and participants learned to utilize mindfulness during difficult emotions. The fifth session focused on cultivating acceptance and allowing participants to experience thoughts and emotions without judgment. They explored difficult emotions through meditation and examined their effects. In the sixth session, participants learned to recognize thoughts as mental events rather than absolute truths and explored the impact of thoughts on the body and mind. The seventh session emphasized self-care through mindfulness practices, and participants planned how to manage arising difficulties mindfully. In the final session, participants applied mindfulness techniques to cope with future emotional challenges and reviewed and integrated what they had learned throughout the program.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy: This treatment manual is adapted from White [35]. The first meeting established communication and initial understanding, specified goals, identified negative thoughts about diabetes and gestational diabetes, and emphasized the importance of completing homework between sessions. The second session evaluated participants’ knowledge about gestational diabetes and taught the cognitive-behavioral approach to understanding diabetes, its symptoms, and complications. Spontaneous thoughts regarding gestational diabetes were identified, and homework included studying the provided gestational diabetes pamphlet. The third session encouraged participants to express their stress, concerns, and factors causing anxiety related to gestational diabetes. Stress management techniques, including relaxation methods and breathing exercises, were taught. Homework involved daily relaxation exercises for ten minutes and recording stress levels along with the skills used in stress management. In the fourth session, the technique of “how thoughts create emotions” was employed to address negative thoughts and beliefs causing negative emotions in pregnant women. Participants discussed food groups, dietary considerations for women with gestational diabetes, and changes they could make in their eating behavior. Homework included completing a table for recording events, thoughts, and feelings, as well as documenting negative emotions and the thoughts behind them. Two diet change activities were recorded over two sessions. The fifth session discussed physical activities during pregnancy, types of permitted sports for mothers with gestational diabetes, and the importance of family support. Techniques for confirming or rejecting beliefs related to gestational diabetes were introduced. Homework included recording a case of self-expression without anger and refraining from daily walking hours. The sixth session involved assessing and identifying concerns and examining the advantages and disadvantages of worrying through group discussion. Theoretical and practical training on insulin injection and glucometer use was provided. Successful mothers in glycemic control were invited to share their experiences. Homework included recording insulin injections and glucometer use during the week. In the seventh session, the main counseling content was reviewed, feedback was given and received, and the extent to which participants achieved their goals was assessed. Finally, positive feedback was provided to members, positive memories were defined, and a follow-up measurement date was determined for one month later. The session ended with the facilitation of ongoing communication between the consultant and clients.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using repeated measures mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) by SPSS software 25 at a significance level of <0.05. Before conducting the ANOVA, its assumptions were examined. To assess the normality of the distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed, which confirmed normal distribution (p>0.05). Levene’s test was used to examine the homogeneity of variances, which was confirmed (p>0.05). However, the assumption of sphericity was not achieved (p<0.01); thus, the Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon correction was applied.

Findings

Forty-five pregnant mothers participated in the study. The mean age of participants in the mindfulness, CBT, and control groups was 27.00±3.10, 26.20±3.50, and 25.60±1.62 years, respectively.

The results of the within-group ANOVA showed significant differences in self-care at different stages in the mindfulness group (F=341.2; p<0.01). According to the Bonferroni post hoc test, a significant increase was observed in self-care scores at the post-test stage compared to the pre-test stage (t=28.36; p<0.01). Additionally, in the follow-up stage, a significant increase in self-care was observed compared to the pre-test stage (t=25.93; p<0.01). However, in the follow-up stage, a significant decrease in self-care was observed compared to the post-test stage (t=2.53; p<0.01).

The results of the within-group ANOVA also showed significant differences in self-care at different stages in the CBT group (F=579.9; p<0.01). According to the Bonferroni test, a significant increase was observed in self-care scores in the post-test stage compared to the pre-test stage (t=14.13; p<0.01). Similarly, the follow-up self-care score also showed a significant increase compared to the pre-test stage (t=13.13; p<0.01). However, there was no significant difference in self-care scores between the post-test and follow-up stages (t=1; p>0.05).

The within-group ANOVA did not show significant differences in self-care scores at different stages in the control group (F=2.11; p>0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Self-care scores in the studied groups

The between-group ANOVA results indicated no significant difference among the three groups at the pre-test stage (F=0.55; p>0.05). However, in the post-test stage, differences between groups became significant (F=199.3; p<0.01). Follow-up examination using the Bonferroni test revealed a significant increase in self-care scores for the mindfulness group compared to the CBT group (t=12; p<0.01). Additionally, the mindfulness group demonstrated a significant increase in self-care score compared to the control group (t=29.26; p<0.01). In the CBT group, a significant increase in self-care was observed compared to the control group (t=16.66; p<0.01).

Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the effect of CBT and mindfulness intervention on diabetic self-care of depressed women with gestational diabetes. Mindfulness showed greater effectiveness than CBT in improving self-care among depressed women with gestational diabetes. Self-care for pregnant mothers is a complex and multifaceted process. They must not only undertake various pregnancy-related care [3] but also manage the added burden of a dual diagnosis (depression and diabetes). Mindfulness can contribute to improving this situation as it enhances attention, active memory, and executive function [22]. Additionally, mindfulness reduces over-generalized autobiographical memory, which is a marker of depression [36]. Focusing on the body is a prime starting point for the mindfulness process and achieving mental health while adhering to self-care directives. Among individuals who had practiced simple meditation in previous studies, a direct relationship between body awareness and health care status was found. Body awareness helps to increase attention regulation, achieve mental health, and reduce anxiety symptoms [37]. Patients with mindfulness abilities are more attuned to the present moment and recognize the importance of participating in self-care activities that protect against diabetes, enabling them to manage their condition more efficiently [38].

CBT also improved diabetes self-care. Optimal control of this multifaceted and chronic condition largely depends on patient adherence to medical appointments and lifestyle changes. Cognitive therapy enhances patients’ awareness of the relationship between glucose control and negative thoughts, behaviors, and emotions regarding diabetes. It also assists patients in more fully engaging in self-care behaviors and achieving better blood sugar control compared to exercise and dietary adherence alone [39]. CBT effectively reduces irrational beliefs and the psychological pressure resulting from these beliefs.

Although mindfulness was more effective in improving self-care among depressed women with gestational diabetes, a noticeable reduction in therapeutic effects was observed during the follow-up phase, while such an effect was not observed for cognitive therapy. These observations suggest the potential for greater durability of therapeutic effects for cognitive therapy. The research history on this specific patient group is limited; however, studies in similar domains indicate that mindfulness-based therapy for depression is more clinically effective and economically advantageous [40].

Each of these two approaches has its own specific mechanism of action. While mindfulness focuses on emotional-cognitive patterns, such as avoidance and rumination [41], CBT concentrates on cognitive processes [42]. Highlighting the specific needs of each patient can assist in selecting the appropriate therapeutic approach. These findings indicate the need for further research, considering that mindfulness maintained greater effectiveness over cognitive therapy during the follow-up phase, although it showed a decreasing trend.

Many parameters were not examined in this study, especially since the current research was conducted in a limited area and did not utilize a random sampling design with a larger sample size. These aspects could be addressed in future research. Also, further research is needed to explore additional parameters and optimize treatment selection for individual patient needs.

Conclusion

While both mindfulness and CBT show promise in enhancing self-care among depressed women with gestational diabetes, mindfulness appears particularly effective in addressing the complex interplay of depression and diabetes management. However, CBT demonstrates the potential for longer-lasting therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all the participants who made this study possible.

Ethical Permissions: The Islamic Azad University, Roudehen Branch approved this study [IR.IAU.REC.1402.020], ensuring compliance with ethical guidelines and standards.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Samkhaniani N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (40%); Lotfi Kashani F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (40%); Vaziri Sh (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This study received no funding.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2024/05/5 | Accepted: 2024/08/28 | Published: 2024/09/30

Received: 2024/05/5 | Accepted: 2024/08/28 | Published: 2024/09/30

References

1. Davis D, Kurz E, Hooper ME, Atchan M, Spiller S, Blackburn J, et al. The holistic maternity care needs of women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review with thematic synthesis. Women Birth. 2024;37(1):166-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.wombi.2023.08.005]

2. Parsons J, Sparrow K, Ismail K, Hunt K, Rogers H, Forbes A. Experiences of gestational diabetes and gestational diabetes care: A focus group and interview study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):25. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-018-1657-9]

3. He J, Chen X, Wang Y, Liu Y, Bai J. The experiences of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(4):777-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11154-020-09610-4]

4. Wang H, Li N, Chivese T, Werfalli M, Sun H, Yuen L, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Estimation of global and regional gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence for 2021 by international association of diabetes in pregnancy study group's criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109050. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109050]

5. Delpisheh M, Firouzkouhi M, Rahnama M, Badakhsh M, Abdollahimohammad A. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. J Diabetes Nurs. 2022;10(2):1872-85. [Persian] [Link]

6. American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):S13-22. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc16-S005]

7. Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119]

8. Niroumand Sarvandani M, Asadi M, Izanloo B, Soleimani M, Mahdavi F, Gearhardt AN, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis and gender invariance of Persian version of the modified Yale food addiction scale (mPYFAS) 2.0: insight from a large scale Iranian sample. J Eat Disord. 2024;12:14. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40337-023-00962-1]

9. Salimi HR, Griffiths MD, Alimoradi Z. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among pregnant women with diabetes and their predictors. Diabetes Epidemiol Manag. 2024;14:100198. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.deman.2024.100198]

10. Mogre V, Johnson NA, Tzelepis F, Paul C. Barriers to diabetic self‐care: A qualitative study of patients' and healthcare providers' perspectives. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(11-12):2296-308. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.14835]

11. Sina M, Graffy J, Simmons D. Associations between barriers to self-care and diabetes complications among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:126-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.04.031]

12. OuYang H, Chen B, Abdulrahman AM, Li L, Wu N. Associations between gestational diabetes and anxiety or depression: A systematic review. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021:9959779. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2021/9959779]

13. Azami M, Badfar G, Soleymani A, Rahmati S. The association between gestational diabetes and postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;149:147-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.01.034]

14. Zhang C, Jing L, Wang J. Does depression increase the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pak J Med Sci. 2023;39(1):285-92. [Link] [DOI:10.12669/pjms.39.1.6845]

15. Hunter CM. Understanding diabetes and the role of psychology in its prevention and treatment. Am Psychol. 2016;71(7):515-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0040344]

16. Grieb SM, McAtee H, Sibinga E, Mendelson T. Exploring the influence of a mindfulness intervention on the experiences of mothers with infants in neonatal intensive care units. Mindfulness. 2023;14(1):218-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12671-022-02060-w]

17. Sarvandani MN, Moghadam NK, Moghadam HK, Asadi M, Rafaiee R, Soleimani M. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) treatment on anxiety, depression and prevention of substance use relapse. Int J Health Stud. 2021;7(2):12-6. [Link]

18. Khanpour F, Karimi A, Shahoie R, Sharifish S, Soufizadeh N. Investigating the effect of mindfulness training on depression in pregnant women. Zanko J Med Sci. 2020;21(69):35-46. [Persian] [Link]

19. Oyarzabal EA, Seuferling B, Babbar S, Lawton-O'Boyle S, Babbar S. Mind-body techniques in pregnancy and postpartum. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;64(3):683-703. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000641]

20. Yang X, Li Z, Sun J. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy-based intervention on improving glycaemic, psychological, and physiological outcomes in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:711. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00711]

21. Niroumand Sarvandani M, Sheikhi Koohsar J, Rafaiee R, Saeedi M, Tamijani SMS, Ghazvini H, et al. COVID-19 and the brain: A Psychological and resting-state functional magnetic resonance imagin (fMRI) study of the whole-brain functional connectivity. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2023;14(6):753-72. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/bcn.2021.1425.4]

22. Pan X, Wang H, Hong X, Zheng C, Wan Y, Buys N, et al. A group-based community reinforcement approach of cognitive behavioral therapy program to improve self-care behavior of patients with type 2 diabetes. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:719. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00719]

23. Sukarno A, Bahtiar B. The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy on psychological stress, physical health, and self-care behavior among diabetes patients: A systematic review. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;10(3):531-7. [Link]

24. First MB, Williams JB, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. User's guide for the SCID-5-CV structured clinical interview for DSM-5® disorders: Clinical version. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2016. [Link]

25. Delavar A. Educational and psychological research. Tehran: Virayesh Publication Institute; 2005. [Persian] [Link]

26. Fatahi N, Kazemi S, Bagholi H, Kouroshnia M. Comparison of the effectiveness of two classic cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on the emotion regulation strategies of patients with type 2 diabetes in Shiraz. J Psychol Sci. 2021;20(101):813-21. [Persian] [Link]

27. Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943-50. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/diacare.23.7.943]

28. Kordi M, Banaei M, Asgharipour N, Mazloum SR, Akhlaghi F. Prediction of self-care behaviors of women with gestational diabetes based on Belief of Person in own ability (self-efficacy). Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2016;19(13):6-17. [Persian] [Link]

29. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782]

30. Al Nasr RS, Altharwi K, Derbah MS, Gharibo SO, Fallatah SA, Alotaibi SG, et al. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross sectional study. PloS One. 2020;15(2):e0228666. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0228666]

31. Sari DN, Diatri H, Siregar K, Pratomo H. Adaptation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in the Indonesian version: Self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms in pregnant women adaptation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in the Indonesian version: Self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms in pregnant women. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2021;9(B):1654-9. [Link] [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2021.7783]

32. Ahmadi Kani Golzar A, Gholizadeh Z. Validation of Edinburgh postpartum depression scale (EPDS) for screening postpartum depression in Iran. Iran J Psychiatric Nurs. 2015;3(3):1-10. [Persian] [Link]

33. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophy living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Bantam; 2005. [Link]

34. Segal ZV, Williames JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindful based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Link]

35. White CA. Cognitive behavioral principles in chronic disease. West J Med. 2001;175(5):338-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/ewjm.175.5.338]

36. Williams JM, Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Soulsby J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(1):150-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.109.1.150]

37. Burzler MA, Voracek M, Hos M, Tran US. Mechanisms of mindfulness in the general population. Mindfulness. 2019;10:469-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12671-018-0988-y]

38. Badpar S, Bakhtiarpour S, Heidari A, Moradimanesh F. Structural model of diabetic patients' self-care based on depression and mindfulness: The mediating role of health-based lifestyle. J Diabetes Nurs. 2020;8(1):1032-44. [Persian] [Link]

39. Nash J. Diabetes and wellbeing: Managing the psychological and emotional challenges of diabetes Types 1 and 2. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/9781118485415]

40. Strauss C, Bibby-Jones AM, Jones F, Byford S, Heslin M, Parry G, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of supported mindfulness-based cognitive therapy self-help compared with supported cognitive behavioral therapy self-help for adults experiencing depression: The low-intensity guided help through mindfulness (LIGHTMind) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(5):415-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0222]

41. Segal Z, Williams M, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Publications; 2018. [Link]

42. Kuyken W, Warren F, Taylor R, Whalley B, Crane C, Bondolfi G, et al. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;73(6):565-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |