Volume 12, Issue 2 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(2): 173-179 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Akhtarian S, Bahramipour Isfahani M, Manshaee G. Effect of the Healthy Body Image Package and Cash Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Perfectionism in Adolescents with Body Dissatisfaction. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (2) :173-179

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73583-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73583-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

Keywords: Body Image [MeSH], Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy [MeSH], Perfectionism [MeSH], Body Dissatisfaction [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 637 kb]

(3928 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1938 Views)

Full-Text: (251 Views)

Introduction

Over the past few decades, there has been growing interest in the rapid and noticeable physical, psychological, emotional, and social developments of adolescents. In other words, during the adolescent growth period, individuals possess the highest and fastest growth opportunities and, given the necessary conditions for growth, will achieve their optimal capabilities [1]. As mentioned, during this period, individuals undergo multifaceted changes resulting from the process of puberty, potentially impacting the adolescent's life significantly. Notably, adolescents naturally become particularly sensitive to their physical appearance during this phase [2]. While attention to appearance is a normal characteristic of every human being, excessive focus on certain body aspects can lead to numerous problems for individuals [3]. In other words, excessive attention to certain body aspects causes distress and dissatisfaction for the individual [4]. Body image serves as an internal representation of the physical aspects of the body. More precisely, body image is an individual's internal perspective on how they appear and what feelings they have about themselves [5]. Dissatisfaction with one's appearance (body image dissatisfaction) has become a global phenomenon, often accompanied by excessive behaviors to remedy perceived body issues [6].

Body dissatisfaction involves concerns and mental preoccupation with an imagined flaw in one's appearance or an exaggerated mental focus on a perceived minor defect. Researchers specify that during certain stages of adolescence, individuals may engage in obsessive behaviors (such as mirror checking and excessive grooming) or mental activities (like comparing their appearance to others), and this mental preoccupation can lead to significant emotional distress or noticeable impairment in functioning in critical life domains [7]. Adolescents typically do not seek help for body dissatisfaction in the early stages of adolescence, often due to feelings of shame, and it is less frequently reported as the primary complaint [2].

The consequences of body dissatisfaction are variable and encompass physical, psychological, and biological challenges from moderate to severe throughout one's [8]. For instance, individuals with body dissatisfaction may suffer from digestive problems, hormonal disorders, high blood pressure, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, and are more vulnerable to chronic physical and other mental health disorders. Moreover, due to negative body image and dissatisfaction with their appearance, they often experience emotional dysregulation and social anxiety, with diminished emotional regulation skills, and an increased inclination towards substance use [9]. Therefore, body dissatisfaction significantly disrupts daily functioning, leads to sleep problems, reduces the quality of life, and imposes economic and social burdens on affected individuals and society [10].

One crucial component related to the concept of body dissatisfaction is perfectionism, as it plays a vital role in an individual's self-perception [11]. Perfectionism is a complex concept involving striving for unrealistic personal standards, excessive self-examination focusing on mistakes during failures, and an extreme emphasis on organizational precision [12]. Hewitt and Flett suggest a significant correlation between perfectionism and mental disorders [13]. They distinguish three self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism dimensions of perfectionism. Self-oriented perfectionism refers to a tendency to set unrealistic and unattainable standards for oneself, focusing excessively on flaws and failures. In this type of perfectionism, individuals intensely criticize themselves and experience anger and frustration if they cannot meet these criteria. Other-oriented perfectionism involves having excessive expectations and critically evaluating others. Individuals with this type of perfectionism become angry if they see that others cannot perform well and meet the set standards. Socially prescribed perfectionism refers to the need to meet the standards and expectations of significant others to gain their approval, fearing rejection or embarrassment if they fail to do so.

As these excessive standards are perceived as externally imposed by others, individuals may feel a sense of uncontrollability leading to feelings of failure, anxiety, anger, frustration, and despair, often associated with suicidal thoughts and depression [14].

In recent years, psychological interventions within the broad framework of cognitive-behavioral approaches, alongside integrative therapies, have garnered attention from researchers and therapists to assist individuals with body dissatisfaction, particularly adolescents. Alongside enhancing adolescents' capacities through promoting healthy body image to improve their psychological and emotional well-being and the need to enhance emotional, cognitive, and social developmental pathways in adolescents, "Cognitive-Behavioral Body Image Therapy" still holds a special place [15]. In essence, it's an applied individual or group method to help improve negative body image in clinical settings in the short term. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a combination of cognitive restructuring from cognitive therapy along with behavioral modification methods in behavior therapy [16]. The therapist in this intervention aims to make both the behaviors and thoughts causing distress explicit and then modify them to promote adaptive behavior [17].

Considering that the lack of healthy body image can pose a challenging, unnatural, and stressful situation for adolescents, and acknowledging the role of supportive factors in educational interventions on body dissatisfaction, we assessed whether the HBIP and Cash CBT (CCBT) based on the principles and rules of the CBT are effective in beliefs about appearance and perfectionism in 12 to 15-year-old adolescents with body dissatisfaction.

Materials and Methods

The present study employed a semi-experimental research method with a three-group design, comprising the healthy body image, CBT, and control groups. The research was conducted in three pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages. The statistical population included all adolescents aged 12 to 15 in Isfahan's high schools during the academic year 2022-2023. The sample size was determined to be 20 individuals in each group based on similar studies [18], considering an effect size of 0.40, a confidence level of 0.95, a test power of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10%. Consequently, 60 participants were selected as samples through purposive sampling according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. They were then randomly assigned to the three groups using simple random sampling (lottery). However, two participants from the HBIP group and four from the CCBT group dropped out, reducing the respective group sizes to 18 and 16 participants.

Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the research, absence of psychological disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder, eating disorders (e.g., binge eating and anorexia nervosa), depression, anxiety, or chronic physical disorders, not being under psychiatric treatments (medication), age range of 12 to 15 years, and obtaining a maximum score of 30 on the Body Satisfaction Questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included non-cooperation or unwillingness to continue participating in sessions, failure to complete assigned tasks, and absenteeism of more than two sessions during the intervention sessions. Ethical considerations encompassed maintaining confidentiality, using data solely for research objectives without disclosing names, providing complete freedom for individuals to withdraw from continued participation in the study, accurately notifying research results upon participants' request, obtaining written informed consent from participants, obtaining ethical code (IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1402.025) from the Ethics Committee, offering post-training for the control group upon participants' request in a condensed form, and ensuring participants' dignity and perfectionism.

Study tools

1- Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS): To measure body image dissatisfaction, a 9-item scale from the 68-item questionnaire assessing individuals' attitudes towards various dimensions of their body image, developed by Cash et al., was used [16]. This scale is suitable for individuals aged 12 and above and with satisfactory reliability and validity. The scale evaluates satisfaction with different body areas, including the face, upper body, mid-torso, lower torso, muscle tone, weight, height, and overall appearance. Participants self-report their satisfaction level on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "Very Satisfied" to "Very Dissatisfied". The score range is from 9 to 45, with lower scores indicating increased satisfaction with various body areas. Brown et al. reported internal consistency reliability with a coefficient of 0.86 [16]. In a study by Hashemian et al., Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the reliability of the Body Image Attitude Questionnaire and its subscale, resulting in a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 for the body satisfaction subscale [17]. Considering that Cronbach's alpha value exceeds 0.70, this questionnaire demonstrates desirable reliability.

2- The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS): MPS was developed by Hewitt and Flett [13]. It has been standardized and validated in Iran by Borjali. This 30-item scale assesses three dimensions of perfectionism, including self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism. Answers are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (completely disagree to Completely Agree). The score range is from 30 to 150, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perfectionism. In the preliminary validation of the Iranian version of this scale, Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 for self-oriented perfectionism, 0.83 for other-oriented perfectionism, and 0.78 for socially prescribed perfectionism. These coefficients indicate the high internal consistency of the scale.

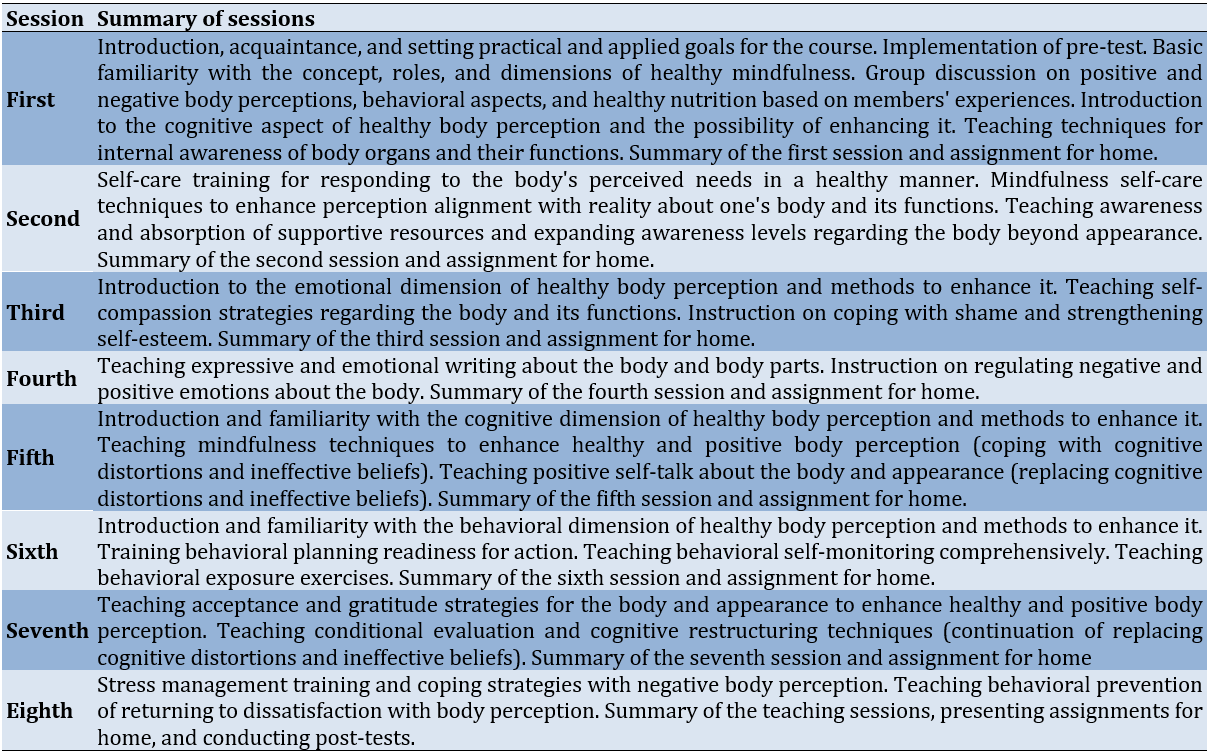

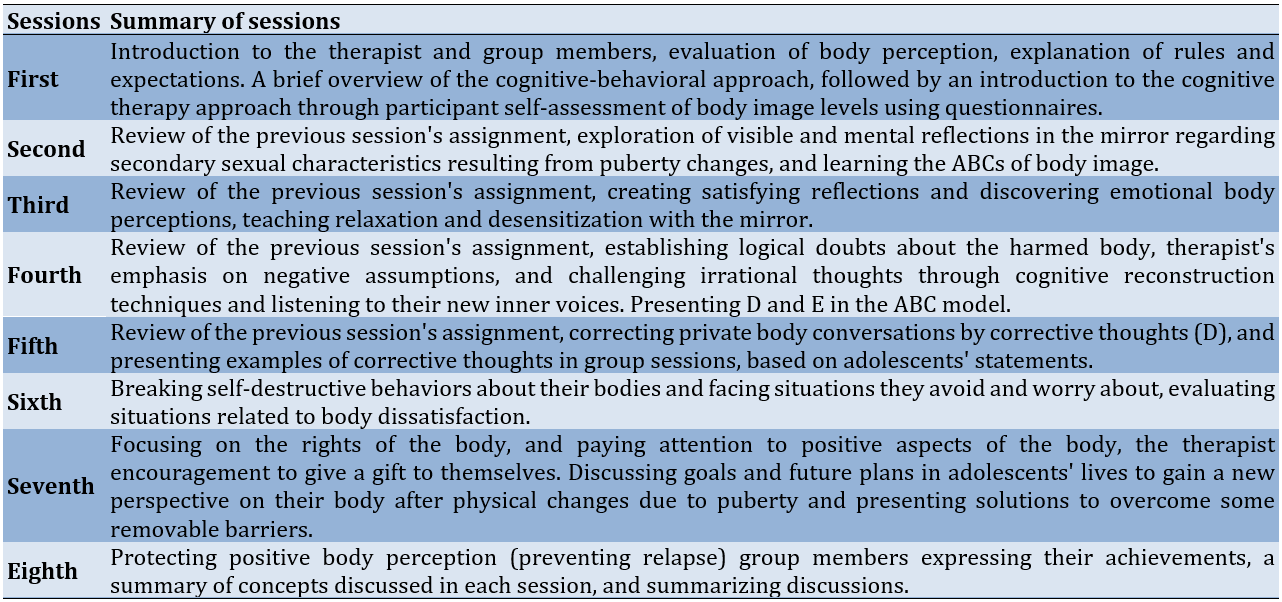

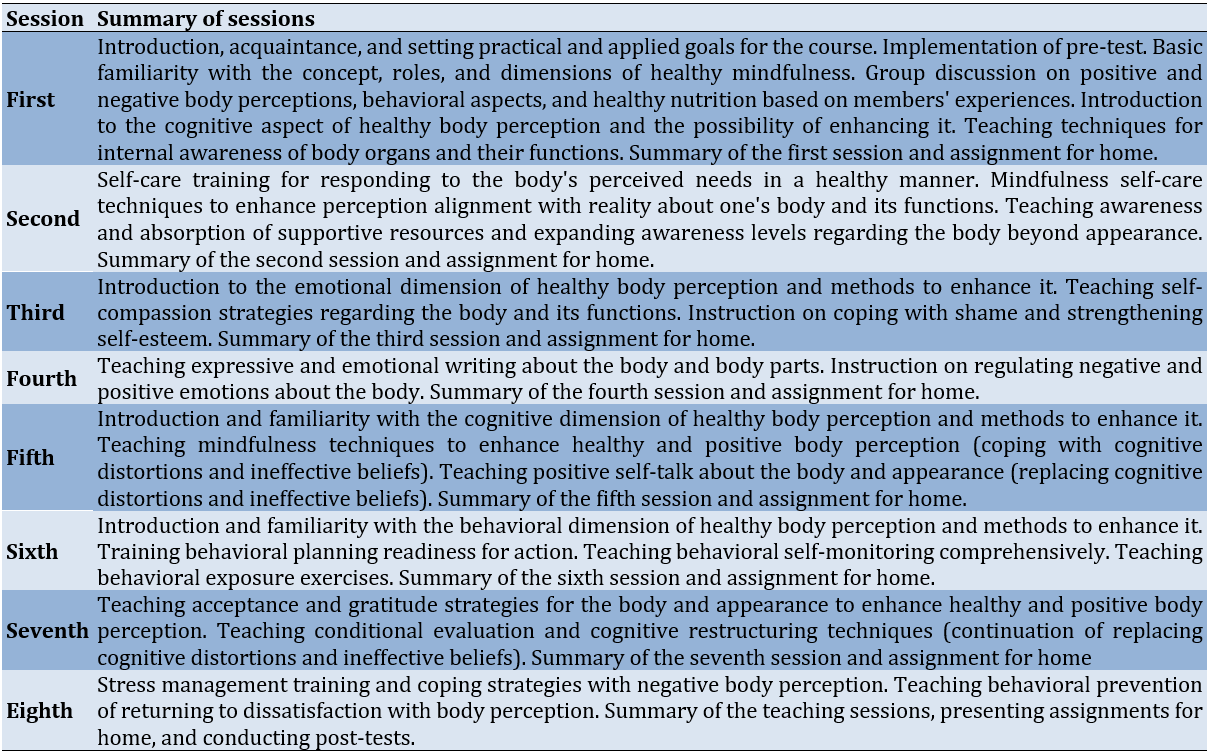

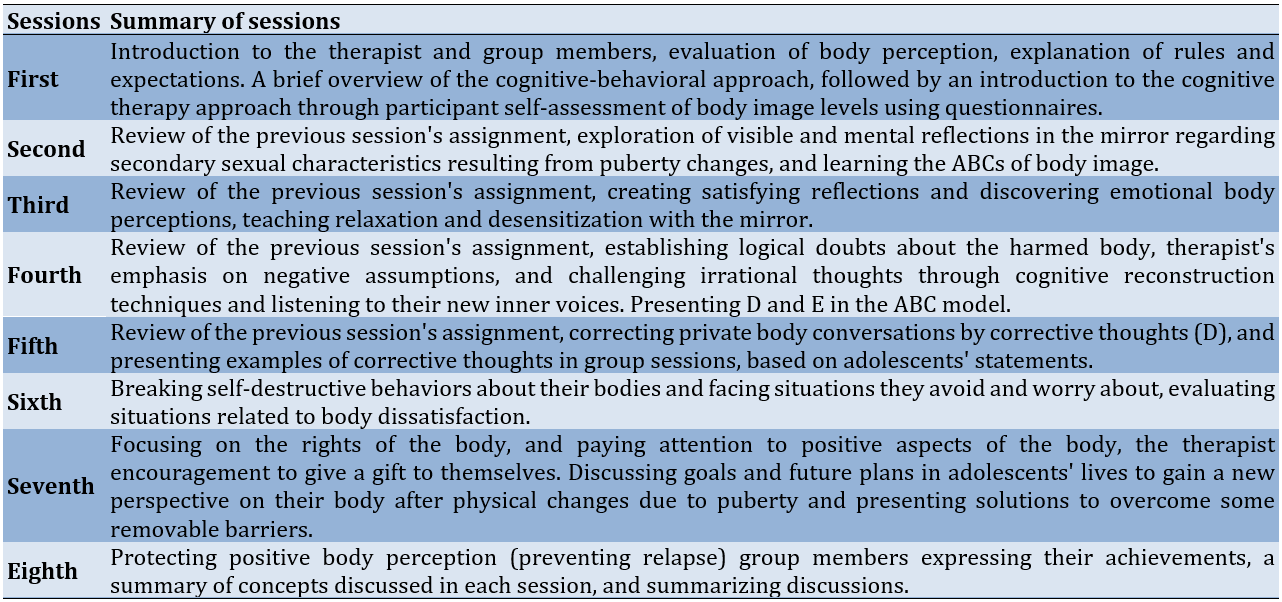

After conducting a pre-test and random assignment of participants to the HBIP, CCBT, and control group, the intervention sessions were implemented using the developed HBIP and CCBT over eight sessions lasting 90 to 120 minutes each [19, 20] (Table 1 & 2). The control group did not receive any intervention and remained on a waiting list. After completing the therapy sessions, a post-test was conducted for all three groups.

Table 1. Brief description of the healthy body image package (HBIP) sessions

Table 2. Brief description of the Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT) sessions

Data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s post hoc test by SPSS 26 at a 0.05 significance level.

Findings

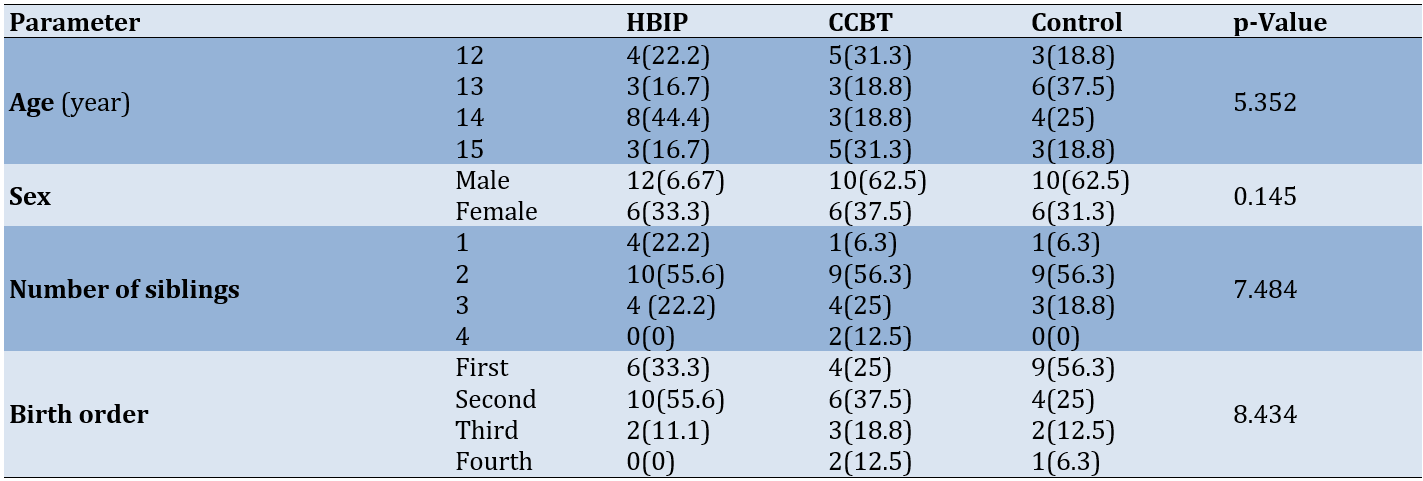

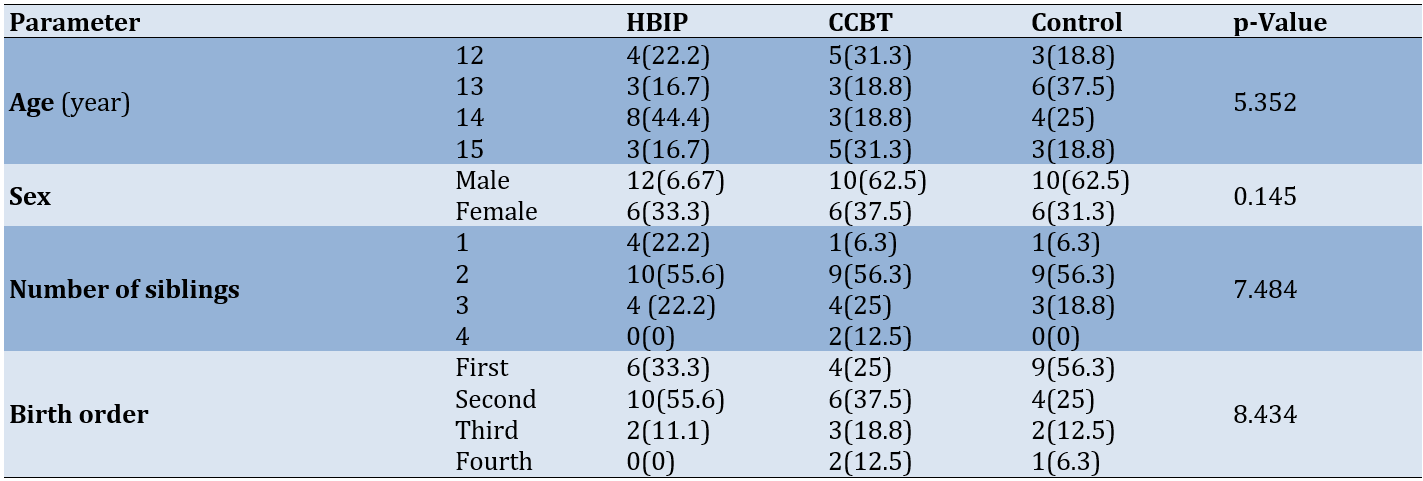

Demographic variables, such as age, gender, the number of siblings in the family, and birth order were examined by the Chi-square test and the results indicated no significant differences among the three research groups regarding demographic variables (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency Sof demographic variables among the Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT), healthy body image package (HBIP), and control groups

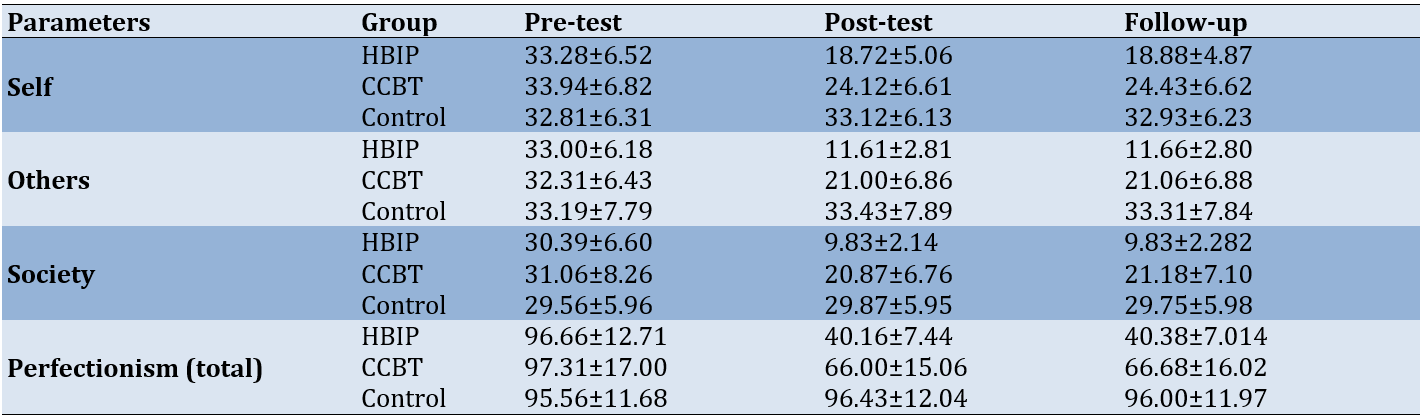

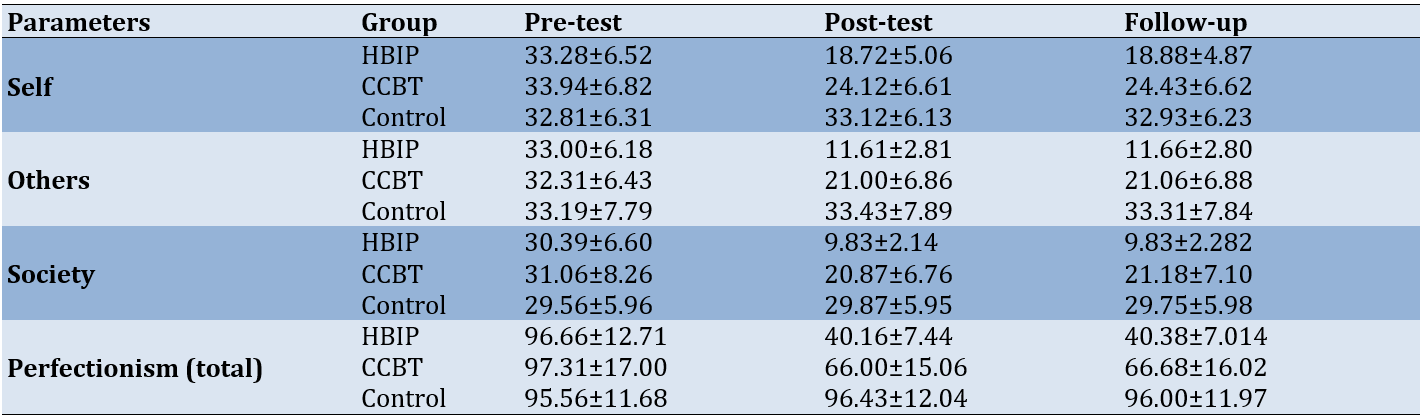

Table 4 displays the mean scores of perfectionism and its components in the groups in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages. The results indicate significant changes in the HBIP and CCBT groups compared to the control group (p<0.05).

Table 4. Mean scores of perfectionism among the Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT), healthy body image package (HBIP), and control groups in three stages

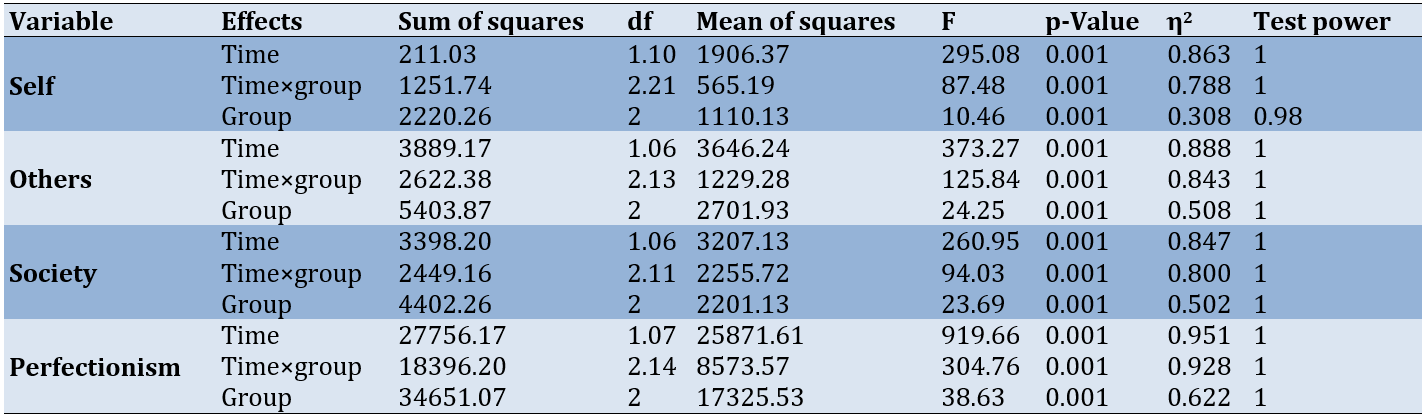

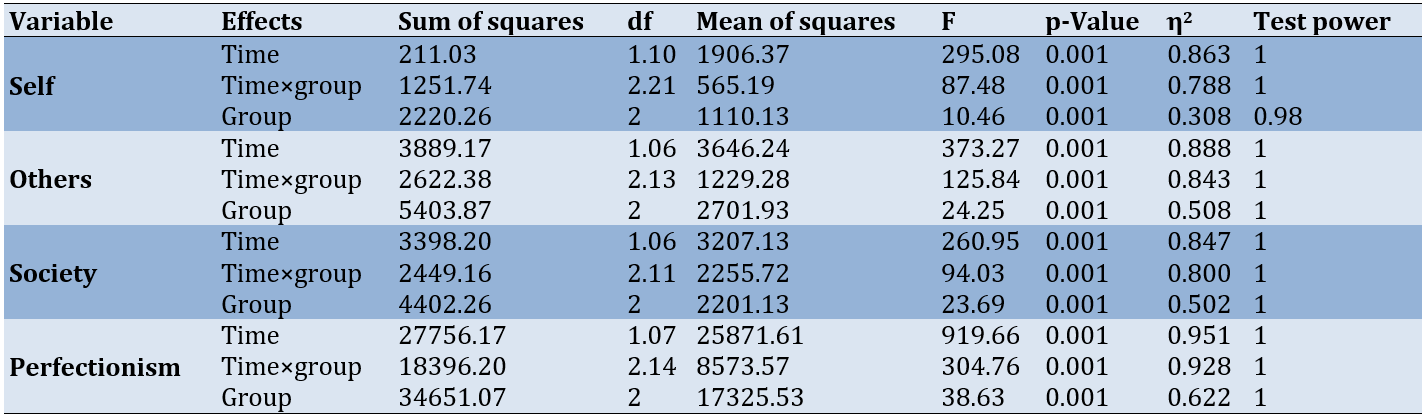

Before conducting repeated measures ANOVA, normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed for perfectionism. The Greenhouse-Geisser statistic was applied when the sphericity assumption was violated. The results revealed significant differences in perfectionism and its components among the HBIP, CCBT, and control groups (Table 5).

Table 5. Repeated measures ANOVA results for perfectionism

The between-group analysis revealed significant differences in perfectionism and its components among the HBIP, CCBT, and control groups. Regarding total perfectionism, time (F=919.66, df=1.073, and p<0.001) and the interaction of time and group (F=304.76, df=2.14, and p<0.001) indicated a significant difference (p<0.001). Also, the group effect showed a significant difference (p<0.001) between the experimental groups in all four components (p<0.001).

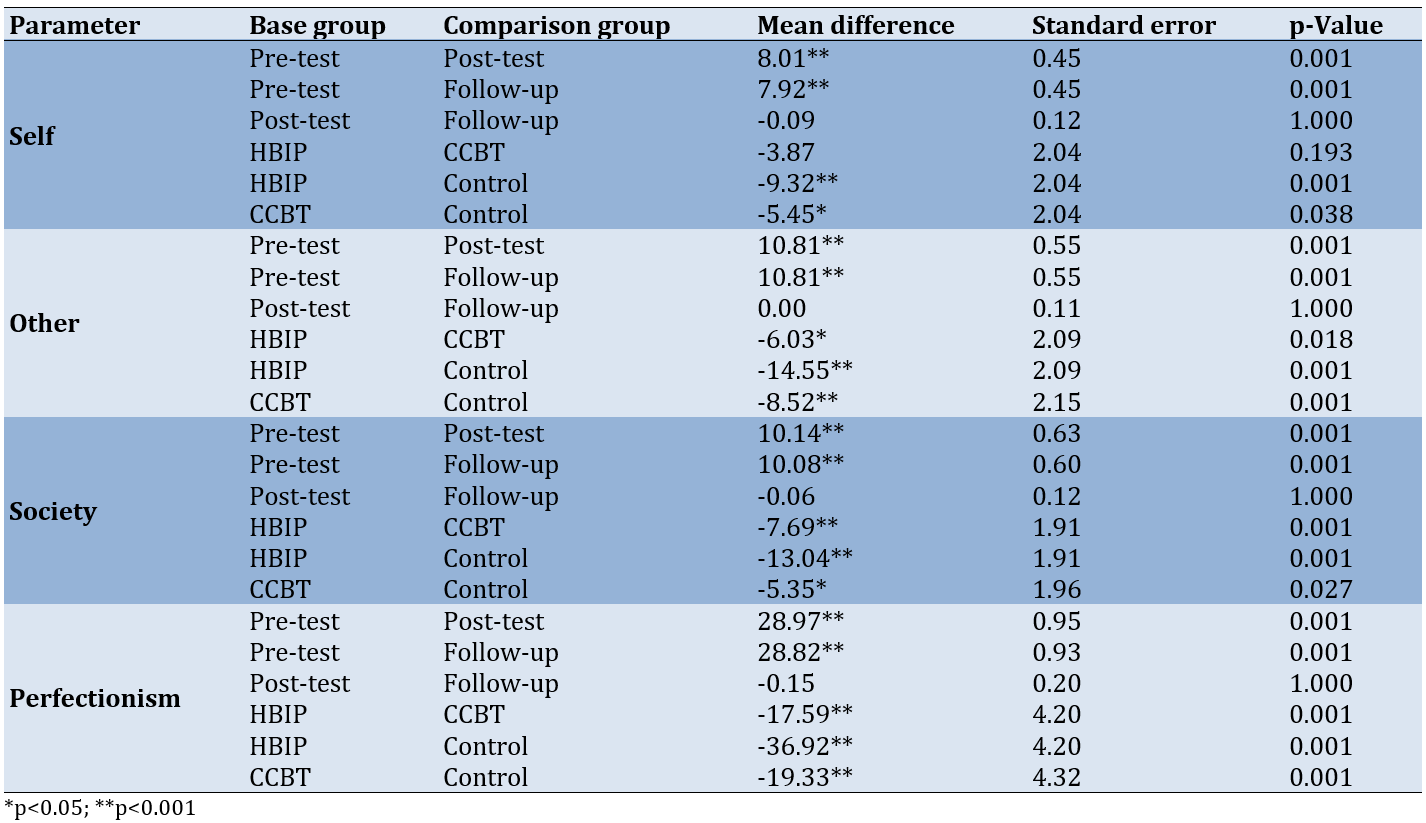

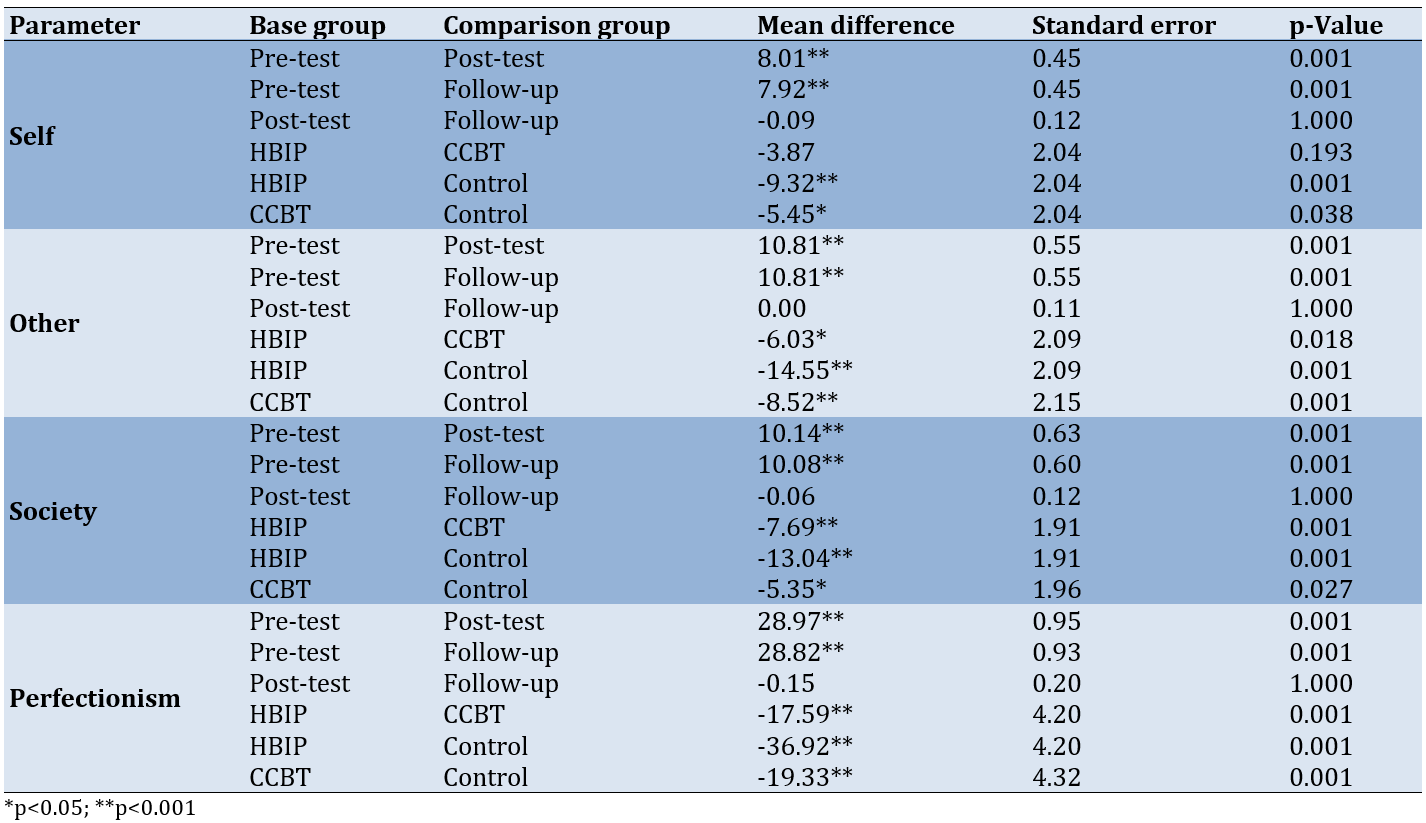

Due to the significant effect of time and group interaction, the pairwise Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted to examine specific group differences (Table 6).

Table 6. Bonferroni’s test results for paired comparison of Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT), healthy body image package (HBIP), and control groups on perfectionism

Discussion

In this study, aimed at examining the effectiveness of the HBIP and CCBT for body image dissatisfaction,S there was a significant difference between the HBIP, CCBT, and control groups. Specifically, the effectiveness of the HBIP in reducing body dissatisfaction among adolescents with body dysmorphic concerns was greater than that of CCBT. The study emphasized the impact of societal standards, media influence, and social networks on body image dissatisfaction among adolescents. The nature and functions of body image dissatisfaction, particularly in perfectionistic tendencies, were discussed.

Because HBIP was developed and validated by the researcher for the first time, it is clear that no research can directly compare the results of this study. However, these results can be in line with the research on the positive role of healthy body image and appreciation in body image dissatisfaction. Baceviciene and Jankauskiene report that appreciation of the healthy body brings about satisfaction with the body [21] and can be used to reduce concerns related to body image in overweight adolescents [22]. Swami et al. also believe that because healthy body appreciation reduces focus on negative body image, it can be expected that body appreciation training has positive effects on improving body image [23]. In this context, Homan and Tylka note that enhancing body appreciation by placing less emphasis on self-worth tied to appearance and external validation can alleviate body image issues [24]. The study by Andrew et al. indicates that heightened body appreciation led to greater acceptance by others and decreased engagement with media portrayals, thereby reducing social comparisons. Internalizing healthy weight loss standards can aid in comprehending your body better [25].

According to our findings, interventions based on HBIP could prove advantageous by targeting emotional, cognitive, and behavioral facets to alleviate the adverse effects of body dissatisfaction. The techniques imparted across cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains in HBIP were viewed as crucial resources capable of significantly influencing the outlook and perfectionistic standards of adolescents experiencing body dissatisfaction. These strategies diminish self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially-oriented perfectionism, thereby lowering the chances of a relapse into body dissatisfaction among adolescents.

The efficacy of CCBT for adolescents grappling with body dissatisfaction in this study resonates with findings concerning the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment-based group therapy and CBT therapy in addressing body dissatisfaction among women [26]. The rationale behind the effectiveness of CBT in this current research was linked to the deployment of strategies and techniques aimed at challenging unrealistic high expectations that bolster perfectionistic perceptions of one’s body. Unrealistic high expectations tied to oneself and one’s body played a pivotal role in exacerbating worries and discontentment regarding body image. CBT tackles these unrealistic expectations by targeting generalized attitudes, thoughts, and beliefs that are deemed unrealistic. Consequently, its objective is to reduce self-oriented and socially-oriented perfectionism by focusing on diminishing unrealistic high expectations associated with oneself and one’s body. While investigating the superior effectiveness of HBIP over CCBT concerning perfectionism (excluding self-oriented perfectionism), it may be suggested that as the initial study comparing the efficacy of HBIP with CCBT on perfectionism, further scrutiny of the theoretical and practical rationales for this discrepancy is warranted.

Nevertheless, the focus on fostering positive self-oriented outlooks alongside emotional well-being and coping skills within the HBIP in this study likely played a role in transitioning from perfectionistic and irrational expectations tied to others and societal standards to cultivating positive self-oriented aspirations, expectations, and viewpoints. This transition could be regarded as a contributing factor to the heightened effectiveness of HBIP over CCBT in diminishing perfectionism among adolescents aged 12 to 15 experiencing body dissatisfaction in the current investigation.

Similar to other studies, the present research had specific limitations. The primary constraint was the restriction of the research population to adolescents aged 12 to 15 experiencing body dissatisfaction in high schools in Isfahan. The economic and educational backgrounds of the students were not evaluated or regulated in this study. Furthermore, random sampling was not employed, taking into account the characteristics of the statistical population. To improve the generalizability of the findings, it is advisable to replicate this study in other cities, consider monitoring the economic and educational statuses of students, and incorporate random sampling in the proposed research methodology. Given the proven efficacy of instructing HBIP and CCBT in alleviating adolescent perfectionism associated with body dissatisfaction, it is pragmatically recommended that educational institutions and planners engage counselors and counseling specialists within their organizational counseling centers and psychological services. Additionally, the utilization of seasoned psychologists specializing in body image issues and the adoption of an adolescent-centered approach to enhancing adolescents’ perfectionism could have a beneficial influence on their personal development and academic progress.

Conclusion

The HBIP is more effective than CCBT in reducing perfectionism among adolescents with body dissatisfaction.

Acknowledgments: We express our gratitude to all participants who patiently contributed to this study.

Ethical Permissions: The research involving human subjects underwent review and approval by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Isfahan. The patients/participants provided written informed consent to partake in this study (IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1402.025).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Akhtarian S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (60%); Bahramipour Isfahani M (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Manshaee G (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%)

Funding/Support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Over the past few decades, there has been growing interest in the rapid and noticeable physical, psychological, emotional, and social developments of adolescents. In other words, during the adolescent growth period, individuals possess the highest and fastest growth opportunities and, given the necessary conditions for growth, will achieve their optimal capabilities [1]. As mentioned, during this period, individuals undergo multifaceted changes resulting from the process of puberty, potentially impacting the adolescent's life significantly. Notably, adolescents naturally become particularly sensitive to their physical appearance during this phase [2]. While attention to appearance is a normal characteristic of every human being, excessive focus on certain body aspects can lead to numerous problems for individuals [3]. In other words, excessive attention to certain body aspects causes distress and dissatisfaction for the individual [4]. Body image serves as an internal representation of the physical aspects of the body. More precisely, body image is an individual's internal perspective on how they appear and what feelings they have about themselves [5]. Dissatisfaction with one's appearance (body image dissatisfaction) has become a global phenomenon, often accompanied by excessive behaviors to remedy perceived body issues [6].

Body dissatisfaction involves concerns and mental preoccupation with an imagined flaw in one's appearance or an exaggerated mental focus on a perceived minor defect. Researchers specify that during certain stages of adolescence, individuals may engage in obsessive behaviors (such as mirror checking and excessive grooming) or mental activities (like comparing their appearance to others), and this mental preoccupation can lead to significant emotional distress or noticeable impairment in functioning in critical life domains [7]. Adolescents typically do not seek help for body dissatisfaction in the early stages of adolescence, often due to feelings of shame, and it is less frequently reported as the primary complaint [2].

The consequences of body dissatisfaction are variable and encompass physical, psychological, and biological challenges from moderate to severe throughout one's [8]. For instance, individuals with body dissatisfaction may suffer from digestive problems, hormonal disorders, high blood pressure, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, and are more vulnerable to chronic physical and other mental health disorders. Moreover, due to negative body image and dissatisfaction with their appearance, they often experience emotional dysregulation and social anxiety, with diminished emotional regulation skills, and an increased inclination towards substance use [9]. Therefore, body dissatisfaction significantly disrupts daily functioning, leads to sleep problems, reduces the quality of life, and imposes economic and social burdens on affected individuals and society [10].

One crucial component related to the concept of body dissatisfaction is perfectionism, as it plays a vital role in an individual's self-perception [11]. Perfectionism is a complex concept involving striving for unrealistic personal standards, excessive self-examination focusing on mistakes during failures, and an extreme emphasis on organizational precision [12]. Hewitt and Flett suggest a significant correlation between perfectionism and mental disorders [13]. They distinguish three self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism dimensions of perfectionism. Self-oriented perfectionism refers to a tendency to set unrealistic and unattainable standards for oneself, focusing excessively on flaws and failures. In this type of perfectionism, individuals intensely criticize themselves and experience anger and frustration if they cannot meet these criteria. Other-oriented perfectionism involves having excessive expectations and critically evaluating others. Individuals with this type of perfectionism become angry if they see that others cannot perform well and meet the set standards. Socially prescribed perfectionism refers to the need to meet the standards and expectations of significant others to gain their approval, fearing rejection or embarrassment if they fail to do so.

As these excessive standards are perceived as externally imposed by others, individuals may feel a sense of uncontrollability leading to feelings of failure, anxiety, anger, frustration, and despair, often associated with suicidal thoughts and depression [14].

In recent years, psychological interventions within the broad framework of cognitive-behavioral approaches, alongside integrative therapies, have garnered attention from researchers and therapists to assist individuals with body dissatisfaction, particularly adolescents. Alongside enhancing adolescents' capacities through promoting healthy body image to improve their psychological and emotional well-being and the need to enhance emotional, cognitive, and social developmental pathways in adolescents, "Cognitive-Behavioral Body Image Therapy" still holds a special place [15]. In essence, it's an applied individual or group method to help improve negative body image in clinical settings in the short term. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a combination of cognitive restructuring from cognitive therapy along with behavioral modification methods in behavior therapy [16]. The therapist in this intervention aims to make both the behaviors and thoughts causing distress explicit and then modify them to promote adaptive behavior [17].

Considering that the lack of healthy body image can pose a challenging, unnatural, and stressful situation for adolescents, and acknowledging the role of supportive factors in educational interventions on body dissatisfaction, we assessed whether the HBIP and Cash CBT (CCBT) based on the principles and rules of the CBT are effective in beliefs about appearance and perfectionism in 12 to 15-year-old adolescents with body dissatisfaction.

Materials and Methods

The present study employed a semi-experimental research method with a three-group design, comprising the healthy body image, CBT, and control groups. The research was conducted in three pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages. The statistical population included all adolescents aged 12 to 15 in Isfahan's high schools during the academic year 2022-2023. The sample size was determined to be 20 individuals in each group based on similar studies [18], considering an effect size of 0.40, a confidence level of 0.95, a test power of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10%. Consequently, 60 participants were selected as samples through purposive sampling according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. They were then randomly assigned to the three groups using simple random sampling (lottery). However, two participants from the HBIP group and four from the CCBT group dropped out, reducing the respective group sizes to 18 and 16 participants.

Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the research, absence of psychological disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder, eating disorders (e.g., binge eating and anorexia nervosa), depression, anxiety, or chronic physical disorders, not being under psychiatric treatments (medication), age range of 12 to 15 years, and obtaining a maximum score of 30 on the Body Satisfaction Questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included non-cooperation or unwillingness to continue participating in sessions, failure to complete assigned tasks, and absenteeism of more than two sessions during the intervention sessions. Ethical considerations encompassed maintaining confidentiality, using data solely for research objectives without disclosing names, providing complete freedom for individuals to withdraw from continued participation in the study, accurately notifying research results upon participants' request, obtaining written informed consent from participants, obtaining ethical code (IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1402.025) from the Ethics Committee, offering post-training for the control group upon participants' request in a condensed form, and ensuring participants' dignity and perfectionism.

Study tools

1- Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS): To measure body image dissatisfaction, a 9-item scale from the 68-item questionnaire assessing individuals' attitudes towards various dimensions of their body image, developed by Cash et al., was used [16]. This scale is suitable for individuals aged 12 and above and with satisfactory reliability and validity. The scale evaluates satisfaction with different body areas, including the face, upper body, mid-torso, lower torso, muscle tone, weight, height, and overall appearance. Participants self-report their satisfaction level on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "Very Satisfied" to "Very Dissatisfied". The score range is from 9 to 45, with lower scores indicating increased satisfaction with various body areas. Brown et al. reported internal consistency reliability with a coefficient of 0.86 [16]. In a study by Hashemian et al., Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the reliability of the Body Image Attitude Questionnaire and its subscale, resulting in a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 for the body satisfaction subscale [17]. Considering that Cronbach's alpha value exceeds 0.70, this questionnaire demonstrates desirable reliability.

2- The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS): MPS was developed by Hewitt and Flett [13]. It has been standardized and validated in Iran by Borjali. This 30-item scale assesses three dimensions of perfectionism, including self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism. Answers are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (completely disagree to Completely Agree). The score range is from 30 to 150, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perfectionism. In the preliminary validation of the Iranian version of this scale, Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 for self-oriented perfectionism, 0.83 for other-oriented perfectionism, and 0.78 for socially prescribed perfectionism. These coefficients indicate the high internal consistency of the scale.

After conducting a pre-test and random assignment of participants to the HBIP, CCBT, and control group, the intervention sessions were implemented using the developed HBIP and CCBT over eight sessions lasting 90 to 120 minutes each [19, 20] (Table 1 & 2). The control group did not receive any intervention and remained on a waiting list. After completing the therapy sessions, a post-test was conducted for all three groups.

Table 1. Brief description of the healthy body image package (HBIP) sessions

Table 2. Brief description of the Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT) sessions

Data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s post hoc test by SPSS 26 at a 0.05 significance level.

Findings

Demographic variables, such as age, gender, the number of siblings in the family, and birth order were examined by the Chi-square test and the results indicated no significant differences among the three research groups regarding demographic variables (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency Sof demographic variables among the Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT), healthy body image package (HBIP), and control groups

Table 4 displays the mean scores of perfectionism and its components in the groups in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages. The results indicate significant changes in the HBIP and CCBT groups compared to the control group (p<0.05).

Table 4. Mean scores of perfectionism among the Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT), healthy body image package (HBIP), and control groups in three stages

Before conducting repeated measures ANOVA, normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed for perfectionism. The Greenhouse-Geisser statistic was applied when the sphericity assumption was violated. The results revealed significant differences in perfectionism and its components among the HBIP, CCBT, and control groups (Table 5).

Table 5. Repeated measures ANOVA results for perfectionism

The between-group analysis revealed significant differences in perfectionism and its components among the HBIP, CCBT, and control groups. Regarding total perfectionism, time (F=919.66, df=1.073, and p<0.001) and the interaction of time and group (F=304.76, df=2.14, and p<0.001) indicated a significant difference (p<0.001). Also, the group effect showed a significant difference (p<0.001) between the experimental groups in all four components (p<0.001).

Due to the significant effect of time and group interaction, the pairwise Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted to examine specific group differences (Table 6).

Table 6. Bonferroni’s test results for paired comparison of Cash cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT), healthy body image package (HBIP), and control groups on perfectionism

Discussion

In this study, aimed at examining the effectiveness of the HBIP and CCBT for body image dissatisfaction,S there was a significant difference between the HBIP, CCBT, and control groups. Specifically, the effectiveness of the HBIP in reducing body dissatisfaction among adolescents with body dysmorphic concerns was greater than that of CCBT. The study emphasized the impact of societal standards, media influence, and social networks on body image dissatisfaction among adolescents. The nature and functions of body image dissatisfaction, particularly in perfectionistic tendencies, were discussed.

Because HBIP was developed and validated by the researcher for the first time, it is clear that no research can directly compare the results of this study. However, these results can be in line with the research on the positive role of healthy body image and appreciation in body image dissatisfaction. Baceviciene and Jankauskiene report that appreciation of the healthy body brings about satisfaction with the body [21] and can be used to reduce concerns related to body image in overweight adolescents [22]. Swami et al. also believe that because healthy body appreciation reduces focus on negative body image, it can be expected that body appreciation training has positive effects on improving body image [23]. In this context, Homan and Tylka note that enhancing body appreciation by placing less emphasis on self-worth tied to appearance and external validation can alleviate body image issues [24]. The study by Andrew et al. indicates that heightened body appreciation led to greater acceptance by others and decreased engagement with media portrayals, thereby reducing social comparisons. Internalizing healthy weight loss standards can aid in comprehending your body better [25].

According to our findings, interventions based on HBIP could prove advantageous by targeting emotional, cognitive, and behavioral facets to alleviate the adverse effects of body dissatisfaction. The techniques imparted across cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains in HBIP were viewed as crucial resources capable of significantly influencing the outlook and perfectionistic standards of adolescents experiencing body dissatisfaction. These strategies diminish self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially-oriented perfectionism, thereby lowering the chances of a relapse into body dissatisfaction among adolescents.

The efficacy of CCBT for adolescents grappling with body dissatisfaction in this study resonates with findings concerning the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment-based group therapy and CBT therapy in addressing body dissatisfaction among women [26]. The rationale behind the effectiveness of CBT in this current research was linked to the deployment of strategies and techniques aimed at challenging unrealistic high expectations that bolster perfectionistic perceptions of one’s body. Unrealistic high expectations tied to oneself and one’s body played a pivotal role in exacerbating worries and discontentment regarding body image. CBT tackles these unrealistic expectations by targeting generalized attitudes, thoughts, and beliefs that are deemed unrealistic. Consequently, its objective is to reduce self-oriented and socially-oriented perfectionism by focusing on diminishing unrealistic high expectations associated with oneself and one’s body. While investigating the superior effectiveness of HBIP over CCBT concerning perfectionism (excluding self-oriented perfectionism), it may be suggested that as the initial study comparing the efficacy of HBIP with CCBT on perfectionism, further scrutiny of the theoretical and practical rationales for this discrepancy is warranted.

Nevertheless, the focus on fostering positive self-oriented outlooks alongside emotional well-being and coping skills within the HBIP in this study likely played a role in transitioning from perfectionistic and irrational expectations tied to others and societal standards to cultivating positive self-oriented aspirations, expectations, and viewpoints. This transition could be regarded as a contributing factor to the heightened effectiveness of HBIP over CCBT in diminishing perfectionism among adolescents aged 12 to 15 experiencing body dissatisfaction in the current investigation.

Similar to other studies, the present research had specific limitations. The primary constraint was the restriction of the research population to adolescents aged 12 to 15 experiencing body dissatisfaction in high schools in Isfahan. The economic and educational backgrounds of the students were not evaluated or regulated in this study. Furthermore, random sampling was not employed, taking into account the characteristics of the statistical population. To improve the generalizability of the findings, it is advisable to replicate this study in other cities, consider monitoring the economic and educational statuses of students, and incorporate random sampling in the proposed research methodology. Given the proven efficacy of instructing HBIP and CCBT in alleviating adolescent perfectionism associated with body dissatisfaction, it is pragmatically recommended that educational institutions and planners engage counselors and counseling specialists within their organizational counseling centers and psychological services. Additionally, the utilization of seasoned psychologists specializing in body image issues and the adoption of an adolescent-centered approach to enhancing adolescents’ perfectionism could have a beneficial influence on their personal development and academic progress.

Conclusion

The HBIP is more effective than CCBT in reducing perfectionism among adolescents with body dissatisfaction.

Acknowledgments: We express our gratitude to all participants who patiently contributed to this study.

Ethical Permissions: The research involving human subjects underwent review and approval by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Isfahan. The patients/participants provided written informed consent to partake in this study (IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1402.025).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Akhtarian S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (60%); Bahramipour Isfahani M (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Manshaee G (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%)

Funding/Support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Social Health

Received: 2024/01/24 | Accepted: 2024/05/2 | Published: 2024/06/21

Received: 2024/01/24 | Accepted: 2024/05/2 | Published: 2024/06/21

References

1. Harrist AW, Criss MM. Parents and peers in child and adolescent development: Preface to the special issue on additive, multiplicative, and transactional mechanisms. Children. 2021;8(10):831. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/children8100831]

2. Sabzavari H, Ghadiri F, Sharififar A. The examination the relationship between health-related physical fitness and Physical self-concept in adolescent. J Sport Sci Educ Appl Res Without Borders. 2019;3(11):20-43. [Persian] [Link]

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Summary of psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences-Clinical Psychiatry. Volume one. Rezaei F, translator. Tehran: Arjmand Publications; 2021. [Persian] [Link]

4. Saleh Mirhasani V, Rafieepoor A, Alavi S. Cognitive behavioral therapy, body dismorphic disorder: A review study. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi J. 2020;9(8):71-8. [Persian] [Link]

5. Haji Yousef H, Dehestani M, Darvish Molla M. The mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties in the relationship between abuse experiences and body image dissatisfaction among adolescent girls. J Appl Psychol Res. 2022;13(1):327-44. [Persian] [Link]

6. Hicks RE, Kenny B, Stevenson S, Vanstone DM. Risk factors in body image dissatisfaction: Gender, maladaptive perfectionism, and psychological wellbeing. Heliyon. 2022;8(6):e09745. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09745]

7. Will D, Naziroglu F. Body dysmorphic disorder, treatment guide. Ahmadi Tahoor Sultani M, Peyambari M, translators. Tehran: Arjmand Publications; 2021. [Persian] [Link]

8. Milano W, Milano L, Capasso A. Health consequences of bulimia nervosa. Biomed Res Clin Pract. 2018;3(1):1-5. [Link] [DOI:10.15761/BRCP.1000158]

9. Anitha L, Alhussaini AA, Alsuwedan HI, Alnefaie HF, Almubrek RA, Aldaweesh SA. Bulimia nervosa and body dissatisfaction in terms of self-perception of body image. In: Himmerich H, Lobera IJ, editors. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa. London: IntechOpen; 2019. [Link] [DOI:10.5772/intechopen.84948]

10. Behdarvandan A, Maktabi A, Ghsemzadeh R, Dastoorpor M. The relationship between the amount of time for brace wear and its psychological effects and the level of social participation of adolescents with spinal deformity. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2021;20(2):112-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JSMJ.20.2.2]

11. Zarei S, Fooladvand K. Relationship between self-esteem and maladaptive perfectionism with workaholism among health care workers: The mediating role of rumination. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2022;9(6):75-85. [Persian] [Link]

12. Hadadi S, Tamannaeifar MR. The comparison of maladjusted perfectionism, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation and rumination in adolescents with high and low social anxiety. Soc Psychol Res. 2022;12(45):1-26. [Persian] [Link]

13. Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism and stress processes in psychopathology. In: Flett GL, Hewitt PL, editors. Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/10458-011]

14. Kang NR, Kwack YS. An update on mental health problems and cognitive behavioral therapy in pediatric obesity. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23(1):15-25. [Link] [DOI:10.5223/pghn.2020.23.1.15]

15. Yusefi A, Taher M, Aghaei H, Baqerinia H. Comparison of the effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy on body image in women referred to cosmetic surgery centers. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2022;29(2):281-90. [Persian] [Link]

16. Brown TA, Cash TF, Mikulka PJ. Attitudinal body-image assessment: Factor analysis of the body-self relations questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(1-2):135-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00223891.1990.9674053]

17. Hashemian M, Aflakseir A, Goudarzi MA, Rahimi C. The relationship between attachment styles and attitudes toward body image in high school girl students: The mediating role of socio-cultural attitudes toward appearance and self-acceptance. Res Cogn Behav Sci. 2021;11(2):1-26. [Persian] [Link]

18. Yari L, Zeini Hassanvand N, Yousefvand M. Comparing the effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy and metacognitive therapy on attachment styles and dimensions of identity transformation in adolescents. Avicenna J Neuro Psycho Physiol. 2023;10(2):64-72. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32592/ajnpp.2023.10.2.104]

19. Akhtarian S, Isfahani MB, Manshaee G. Development of a Healthy Body Image Package for Adolescents Aged 12 to 15 with Body Image Dissatisfaction: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis Approach. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies (JAYPS). 2024;5(5):21-9. [Link] [DOI:10.61838/kman.jayps.5.5.4]

20. Cash T. Body image guide (psychology of body image). Raygan N, translator. Tehran: Danjeh Publications; 2010. [Persian] [Link]

21. Baceviciene M, Jankauskiene R. Associations between body appreciation and disordered eating in a large sample of adolescents. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):752. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu12030752]

22. Fathi Z, Gorji Y. Efficacy of body appreciation training on body image concerns in overweight adolescents. Heliyon. 2023;9(10):e20374. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20374]

23. Swami V, Barron D, Hari R, Grover S, Smith L, Furnham A. The nature of positive body image: Examining associations between nature exposure, self-compassion, functionality appreciation, and body appreciation. Ecopsychology. 2019;11(4):243-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/eco.2019.0019]

24. Homan KJ, Tylka TL. Appearance-based exercise motivation moderates the relationship between exercise frequency and positive body image. Body Image. 2014;11(2):101-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.01.003]

25. Andrew R, Tiggemann M, Clark L. Predictors and health-related outcomes of positive body image in adolescent girls: A prospective study. Dev Psychol. 2016;52(3):463-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/dev0000095]

26. Farahzadi M, Maddahi ME, Khalatbari J. Comparison the effectiveness of group therapy based on acceptance and commitment and cognitive-behavioral group therapy on the body image dissatisfaction and interpersonal sensitivity in women with the body image dissatisfaction. Res Clin Psychol Couns. 2017;7(2):69-89. [Persian] [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |