Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 73-78 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Aris A, Yusuf A, Fitryasari R, Suhariyati S, Ubudiyah M, Faridah V, et al . Improving Cadres’ Capability in Early Detection of Mental Disorders; A Culture-Based Empowerment Model. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :73-78

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73247-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73247-en.html

A. Aris *  1, A. Yusuf2

1, A. Yusuf2  , R. Fitryasari3

, R. Fitryasari3  , S. Suhariyati4

, S. Suhariyati4  , M. Ubudiyah4

, M. Ubudiyah4  , V.N. Faridah4

, V.N. Faridah4  , A.T. Kusumaningrum4

, A.T. Kusumaningrum4  , S. Sholikah4

, S. Sholikah4

1, A. Yusuf2

1, A. Yusuf2  , R. Fitryasari3

, R. Fitryasari3  , S. Suhariyati4

, S. Suhariyati4  , M. Ubudiyah4

, M. Ubudiyah4  , V.N. Faridah4

, V.N. Faridah4  , A.T. Kusumaningrum4

, A.T. Kusumaningrum4  , S. Sholikah4

, S. Sholikah4

1- Faculty of Health Sciences, Lamongan Muhammadiyah University, Lamongan, Indonesia

2- Department of Advanced Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

3- Department of Basic Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

4- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Lamongan Muhammadiyah University, Lamongan, Indonesia

2- Department of Advanced Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

3- Department of Basic Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

4- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Lamongan Muhammadiyah University, Lamongan, Indonesia

Keywords: Cadre [Mesh], Culture [MeSH], Competence [MeSH], Early Diagnosis [MeSH], Mental Disorders [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 685 kb]

(3156 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2009 Views)

Full-Text: (189 Views)

Introduction

A substantial share of the global population is impacted by mental health and psychosocial issues [1]. The prevalence of individuals suffering from mental health and behavioral illnesses is consistently rising on an annual basis, and these disorders exhibit a very intricate nature [2]. To enhance educational and psychosocial functioning in individuals with mental health issues, it is imperative to identify and implement efficacious treatment measures promptly [3]. Timely identification and prompt intervention for mental health issues will mitigate both physical and psychological problems, leading to a significant reduction in global instances of mental diseases. Family and community support facilitate the identification of mental disorders in society. Additionally, culture plays an important role in health by enhancing motivation to recover from illnesses or health problems. This, in turn, improves treatment outcomes and reduces potential risks for patients and their families [4].

According to data collected from 33 mental institutions in Indonesia, there are around 2.5 million individuals suffering from mental diseases in the country. The incidence of mental disorders in East Java is notably high, with 6.5% of the population being affected [5]. A mere 25% of mental health professionals are engaged in the early identification of mental problems. The proficiency of cadres in identifying mental issues in the population through early detection is deficient, with only 40.3% being able to recognize such disorders. On the other hand, 53.3% of cadres possess adequate knowledge in this area [6].

Mental health cadres are closely linked to the community to enhance mental well-being. Nevertheless, the evidence indicates that cadres need more capacity and comprehension in identifying mental diseases at an early stage, resulting in suboptimal performance in detecting and mitigating relapse rates. This is also linked to the emergence of evolving cultural variables in society. The community's local culture is intricately intertwined with religious activities, hence exerting an impact on the conduct of the community itself [7]. The development of mental health cadres should adhere to a structured, systematic, and logical approach [8]. Prior training of cadres in the community to handle mental diseases can positively affect knowledge and self-confidence [9]. Training mental health cadres will enhance their ability to identify early signs of mental problems within society [10].

The prevalence of mental health issues is steadily rising, leading to the potential emergence of undetected mental diseases. The limited availability of data on early identification of mental disorders may be attributed to the suboptimal capacity of cadres in identifying mental disorder circumstances throughout society [11]. This issue highlights the necessity of enhancing the effectiveness of cadres by implementing comprehensive measures that can effectively address the challenges above. In addition, the timely identification of mental diseases is significantly impacted by cultural factors, including language, social concerns, and stigma. The management of mental diseases in society is greatly affected by the local culture, including factors such as social stigma and shame [12]. To address this issue, it is imperative to enhance the capacity of culturally oriented personnel to identify mental problems at an early stage effectively.

According to the sunrise model idea, identifying societal mental problems early requires a cultural approach. An instance illustrating the advantageous nature of cultural influences is facilitating communication between medical personnel and patients, enhancing the ability to identify health issues early. The establishment of mental health care services by trained professionals is necessary to cultivate public confidence and address the social stigma associated with individuals suffering from mental diseases [10]. According to the structural empowerment theory, formal and informal power, such as organizational relationships, can impact individual characteristics. These characteristics include enhanced self-efficacy, motivation, commitment, reduced burnout, increased management involvement, and greater job satisfaction.

The interplay between religion, philosophy of life, social and family connections, cultural values and lifestyle, economics, cultural upbringing, and the ways and frequency of interaction will greatly enhance the potential for early detection capacities. The opportunity structure will empower culture-based cadres through accessibility and flexibility. Support, on the other hand, includes emotional, assessment, and instrumental assistance. The empowerment of cadres through cultural means will impact their values, such as self-efficacy, motivation, commitment, autonomy, and perception. Moreover, it will enhance personnel's proficiency in promptly identifying, overseeing, mobilizing, referring, and documenting. Hence, it is crucial to assess the potential of a culture-oriented cadre empowerment paradigm in enhancing the ability of cadres to identify mental diseases at an early stage within the community.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from September to October 2022 in the entire population of mental health cadres in Lamongan Regency (n=224). This study used the Rule of Thumb to determine the sample size, estimating 5x22 characteristics. So, the sample numbered 110 respondents. Inclusion criteria include mental health cadres registered and actively serving at the Community Health Center in Lamongan Regency. In contrast, exclusion criteria relate to sick cadres voluntarily withdrawing from the study for various reasons. The process of selecting samples was conducted using simple random sampling.

The data collection technique is a questionnaire to assess culturally rooted mental health problems through a survey of 25 multiple-choice questions that evaluate early detection capabilities: a) surveillance, b) mobilization, c) referral, and d) documentation. The questionnaire was assessed to ensure its validity and reliability, with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.355 and p-values ranging from 0.373 to 0.951. Additionally, Croanbach's Alpha, a measure of internal consistency, was between 0.700 and 0.999. After obtaining legal permission and ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University (2641-KEPK), samples were selected, and a questionnaire was presented. The author followed up after asking all respondents to complete the questionnaire once. Data were collected and processed using Structural Equation Modeling-Partial Least Square (SEM-PLS) statistical analysis.

Findings

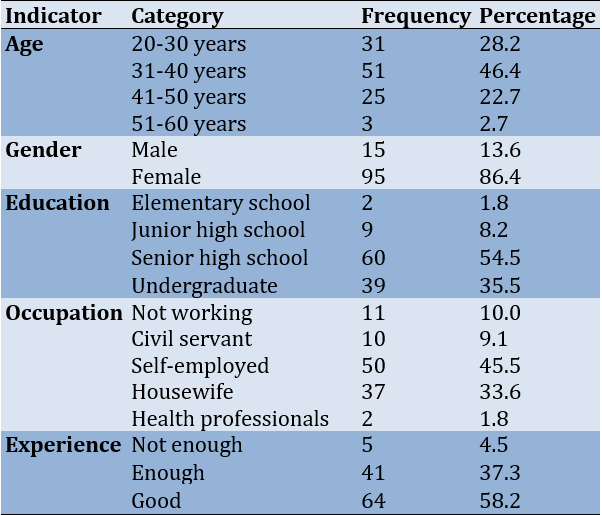

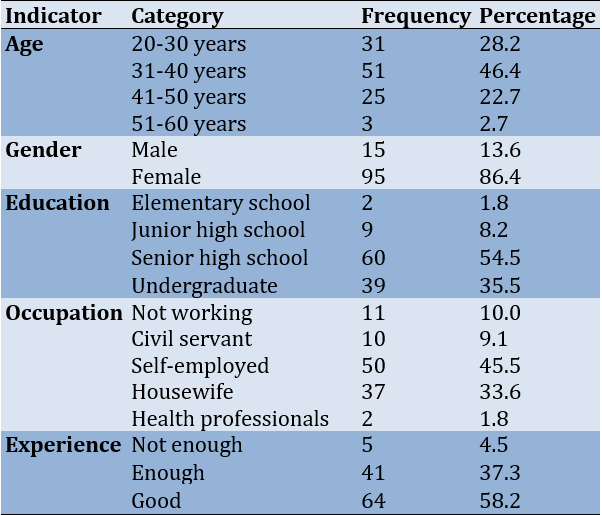

Most participants were female (86.4%) and aged 31 to 40 (46.4%). They mostly had senior high school diplomas (54.5%), were self-employed (45.5%), and had good experience (58.2%; Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of mental health cadre respondents in the Lamongan district community health center area in 2022 (n=110)

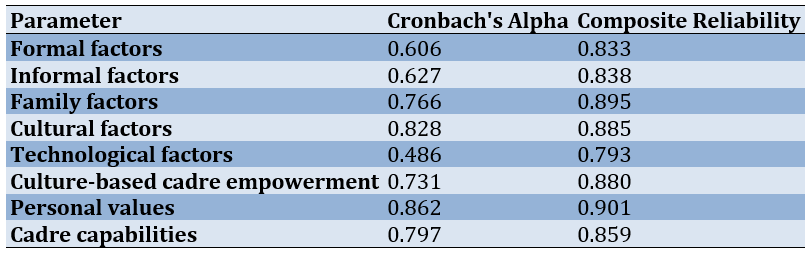

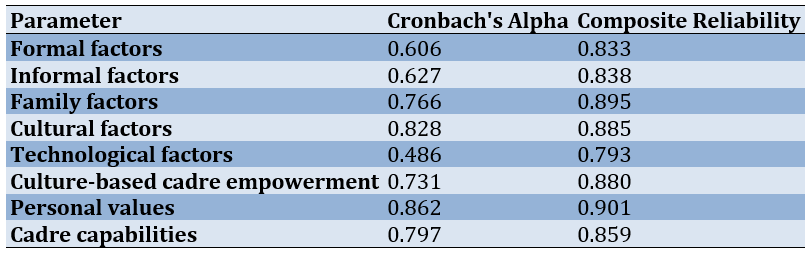

All indicators were considered reliable in assessing variables, proven by calculating the Cronbach alpha or Composite Reliability value (Table 2).

Table 2. Reliability test results for a culture-based cadre empowerment model (all variables were valid)

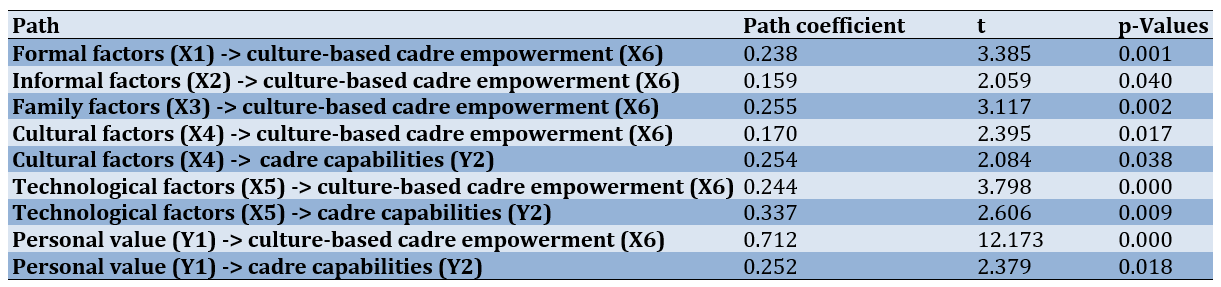

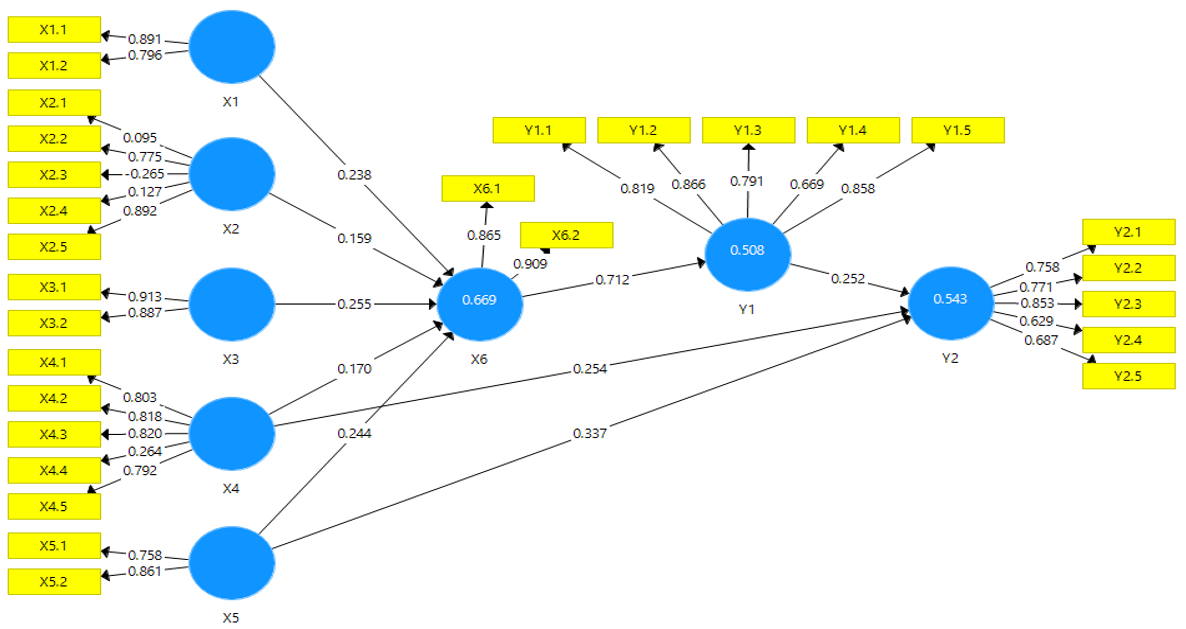

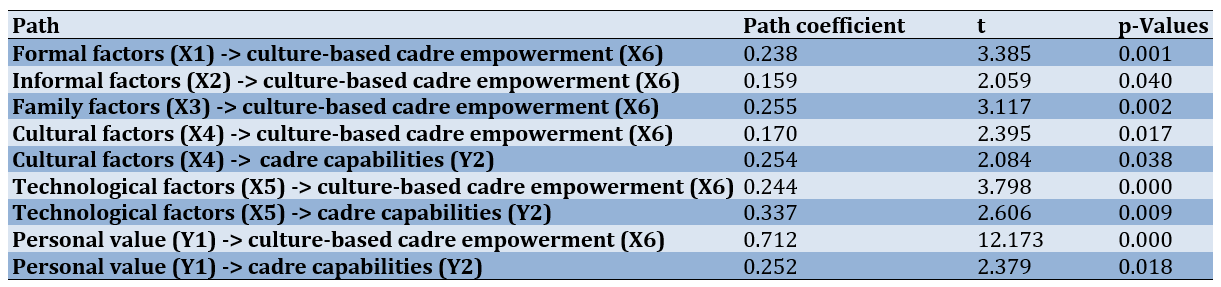

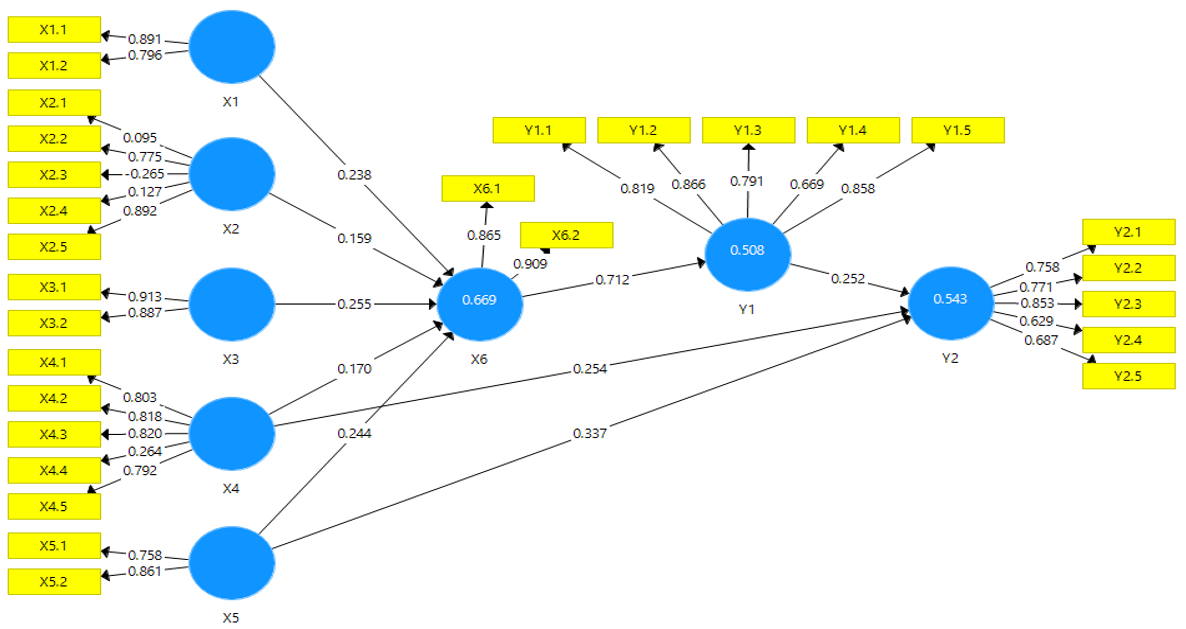

The path analysis revealed significant relationships, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3. The path analysis results

Figure 1. Results on the development of a culture-based cadre empowerment model in increasing the capability to detect early mental disorders

Discussion

Most of the participants in this study were female and had a high school education. Consistent with other studies, 99.6% of mental health professionals are female, and their educational attainment often includes a high school degree [13]. Furthermore, a separate survey indicated that the predominant demographic among health cadres comprises women [14].

The capacity of cadres to identify mental diseases at an early stage (including placing the danger of psychosocial issues, detecting behavioral or symptomatic signs of mental illness, providing supervision, mobilizing resources, making referrals, and maintaining documentation) within the community is adequate. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement in their ability to identify psychosocial risks, detect behavioral or mental symptom indicators, provide supervision, facilitate mobilization, make referrals, and maintain documentation. These findings suggest that empowering cadres through cultural means can enhance their ability to recognize mental problems early. This model comprises formal, informal, family, technology, and cultural elements.

The formation of culture-based cadre empowerment is influenced by formal variables, which are determined by measures of service flow and support from the village head. The service flow is the primary factor determining the level of culture-based cadre empowerment and the subsequent increase in cadre skills. This aligns with empirical research [15]. Mental health cadres and community leaders are crucial in promoting mental health and assisting cadres. Cadres are at the forefront of identifying, managing, and monitoring mental diseases within the community or society. Health service centers equipped with sufficient and superior resources, including facilities, infrastructure, information systems (such as record-keeping or service flow), and a suitable number of health staff, are capable of delivering higher quality services and achieving service coverage targets [16]; Put, the provision of services that sustains and impacts the empowerment of cadres rooted in cultural values.

Village officials serve as an additional indicator of the formal variables that influence the empowerment of culture-based cadres and their ability to enhance their capacities. Cadres are eager to participate voluntarily in implementing and managing health activities within the community. The involvement of health cadres or volunteers in the community is driven by the endorsement of community leaders, particularly when they are acknowledged and trusted by these leaders and esteemed and embraced by the communities they assist while not receiving any remuneration [17]. Additional studies indicate that the level of social support provided to mental health professionals in their work has a notable correlation with the occurrence of individuals with schizophrenia [18]. Consequently, a strong endorsement from the village leader is positively correlated with an enhanced capacity of mental health personnel to identify mental illnesses at an early stage effectively.

Informal elements that contribute to a culture-based cadre's empowerment are determined by gender, education, and experience. Experience has the highest loading factor value, indicating that it has the most impact on measuring informal variables. Mental health cadres acquire expertise through a range of activities, including training. Well-trained cadres will play a significant role in providing mental health care [19]. Additional research indicates discernible disparities between individuals who have received training and those who have not. Specifically, those who have been training exhibit more favorable opinions towards people with mental problems [20].

Furthermore, mental health cadres also require proper instruction to communicate properly. Previous research has demonstrated the crucial role of mental health cadres in providing support and resilience for individuals with mental disorders. These cadres aim to restore the patient's condition, enabling them to regain stability and reintegrate into their families and communities [21]. Cadre training enhances the practical knowledge of cadres in identifying cases, allowing them to play a crucial role in the secondary and primary prevention of mental diseases [22]. Accordingly, the more experienced the cadre is, the higher their ability to recognize mental illnesses early.

Our research indicates that family variables are derived from the responsibilities and duties of the family, which impact the empowerment of culture-based cadres, enhancing their skills. By employing efficient communication strategies, cadres can engage with families, directly impacting their values through culturally oriented cadre empowerment. The ability of cadres to diagnose mental problems early is also influenced by family variables, which involve empowering cadres according to their cultural background and personal values. The family role is the variable with the highest loading factor, indicating that it has the most impact on measuring family aspects. Cadres play a crucial role in conducting direct visits to patients' families to identify mental problems at an early stage. The significance of these cadres is strongly perceived by families and health personnel [23]. According to this, higher-quality family characteristics are positively correlated with the increased ability of mental health professionals to diagnose mental problems at an early stage.

Cultural elements encompass religious and philosophical beliefs, social and familial connections, cultural values and lifestyles, and the influence of cultural upbringing. These factors are crucial in empowering culture-based individuals to enhance their capacities as cadres. The significant impact of social values mostly measures cultural elements. Multiple studies emphasize that mental healthcare in Southeast Asia is significantly shaped by cultural norms, values, and practices [24]. One way to fit the socialization of detection activities to the existing culture in society is by engaging in regular religious practices. Based on [1]. A mental health cadre might fulfill their responsibilities by engaging in community-based activities. According to this, higher-quality cultural variables are positively correlated with the enhanced ability of mental health professionals to identify mental diseases at an early stage.

Our research also indicates that technological aspects, specifically the method and frequency of implementation, impact the empowerment of culture-based cadres, enhancing their capacities. The frequency of occurrence has a significant role in quantifying technical aspects. Technology facilitates the recording, reporting, and monitoring of the development of patients with mental problems, enhancing efficiency and effectiveness. Additionally, it enables cadres to improve their knowledge and abilities [25]. Cadres also employ technology to enhance their digital literacy. They actively utilize technological equipment to acquire expertise and carry out their duties as cadres [26].

Implementing mental health cadre training programs that include comprehensive content on mental health can enhance the skills of cadres, particularly in the area of evaluation [27]. Multiple studies emphasize that cultural norms, values, and practices significantly shape mental healthcare in Southeast Asia. Distinctive components in mental health rehabilitation in Southeast Asia encompass the utilization of cadres as a form of social support and the incorporation of religious activities to enhance the sense of hope among those with schizophrenia [24]. When fulfilling their responsibilities, cadres are prepared for their duties, confident in their ability to effect changes, and offer valuable perspectives on culturally and contextually significant topics. Cadres also experience a sense of prestige and earn the community's confidence in their responsibilities [28]. Cadres enjoy social advantages as they enhance their social standing and garner admiration from the surrounding community, which becomes a source of their pride. Cadres experience a sense of trust as clients and family engage in open discussions on mental health issues. Cadres should prioritize active engagement in long-term mental health initiatives alongside financial incentives, as it is a matter of personal value. The success of future therapy relies on the confidence in the talents and expertise of mental health professionals to identify individuals with mental problems in the community at an early stage. By equipping culturally oriented mental health personnel with authority, it is anticipated that mental health issues can be effectively addressed, and the community will be vigilant to any health-related mental problems that may occur in their vicinity.

Maximizing culture-based empowerment can improve positive outcomes, thereby increasing the ability to identify early signs of mental disorders, such as the detection of psychosocial risks, behavioral indicators, cognitive symptoms, supervision, mobilization, referral, and documentation. The success of future therapy relies on the confidence in the talents and skills of mental health professionals to identify individuals with mental problems in the community at an early stage. By providing authority and resources to mental health professionals who are rooted in certain cultures, the goal is to effectively address mental health issues and ensure that the community is informed about any mental health problems that may occur in their vicinity.

Conclusion

The ability of cadres to detect mental problems at an early stage can be enhanced by promoting a feeling of empowerment.

Acknowledgments: Nothing declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University (2641-KEPK).

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: Aris A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (11%); Yusuf A (Second Author), Introduction Writer (11%); Fitryasari R (Third Author), Introduction Writer (11%); Suhariyati S (Fourth Author), Methodologist (11%); Ubudiyah M (Fifth Author), Methodologist (11%); Faridah VN (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (11%); Kusumaningrum AT (Seventh Author), Assistant Researcher (11%); Sholikah S (Eighth Author), Discussion Writer (11%)

Funding/Support: Nothing declared by the authors.

A substantial share of the global population is impacted by mental health and psychosocial issues [1]. The prevalence of individuals suffering from mental health and behavioral illnesses is consistently rising on an annual basis, and these disorders exhibit a very intricate nature [2]. To enhance educational and psychosocial functioning in individuals with mental health issues, it is imperative to identify and implement efficacious treatment measures promptly [3]. Timely identification and prompt intervention for mental health issues will mitigate both physical and psychological problems, leading to a significant reduction in global instances of mental diseases. Family and community support facilitate the identification of mental disorders in society. Additionally, culture plays an important role in health by enhancing motivation to recover from illnesses or health problems. This, in turn, improves treatment outcomes and reduces potential risks for patients and their families [4].

According to data collected from 33 mental institutions in Indonesia, there are around 2.5 million individuals suffering from mental diseases in the country. The incidence of mental disorders in East Java is notably high, with 6.5% of the population being affected [5]. A mere 25% of mental health professionals are engaged in the early identification of mental problems. The proficiency of cadres in identifying mental issues in the population through early detection is deficient, with only 40.3% being able to recognize such disorders. On the other hand, 53.3% of cadres possess adequate knowledge in this area [6].

Mental health cadres are closely linked to the community to enhance mental well-being. Nevertheless, the evidence indicates that cadres need more capacity and comprehension in identifying mental diseases at an early stage, resulting in suboptimal performance in detecting and mitigating relapse rates. This is also linked to the emergence of evolving cultural variables in society. The community's local culture is intricately intertwined with religious activities, hence exerting an impact on the conduct of the community itself [7]. The development of mental health cadres should adhere to a structured, systematic, and logical approach [8]. Prior training of cadres in the community to handle mental diseases can positively affect knowledge and self-confidence [9]. Training mental health cadres will enhance their ability to identify early signs of mental problems within society [10].

The prevalence of mental health issues is steadily rising, leading to the potential emergence of undetected mental diseases. The limited availability of data on early identification of mental disorders may be attributed to the suboptimal capacity of cadres in identifying mental disorder circumstances throughout society [11]. This issue highlights the necessity of enhancing the effectiveness of cadres by implementing comprehensive measures that can effectively address the challenges above. In addition, the timely identification of mental diseases is significantly impacted by cultural factors, including language, social concerns, and stigma. The management of mental diseases in society is greatly affected by the local culture, including factors such as social stigma and shame [12]. To address this issue, it is imperative to enhance the capacity of culturally oriented personnel to identify mental problems at an early stage effectively.

According to the sunrise model idea, identifying societal mental problems early requires a cultural approach. An instance illustrating the advantageous nature of cultural influences is facilitating communication between medical personnel and patients, enhancing the ability to identify health issues early. The establishment of mental health care services by trained professionals is necessary to cultivate public confidence and address the social stigma associated with individuals suffering from mental diseases [10]. According to the structural empowerment theory, formal and informal power, such as organizational relationships, can impact individual characteristics. These characteristics include enhanced self-efficacy, motivation, commitment, reduced burnout, increased management involvement, and greater job satisfaction.

The interplay between religion, philosophy of life, social and family connections, cultural values and lifestyle, economics, cultural upbringing, and the ways and frequency of interaction will greatly enhance the potential for early detection capacities. The opportunity structure will empower culture-based cadres through accessibility and flexibility. Support, on the other hand, includes emotional, assessment, and instrumental assistance. The empowerment of cadres through cultural means will impact their values, such as self-efficacy, motivation, commitment, autonomy, and perception. Moreover, it will enhance personnel's proficiency in promptly identifying, overseeing, mobilizing, referring, and documenting. Hence, it is crucial to assess the potential of a culture-oriented cadre empowerment paradigm in enhancing the ability of cadres to identify mental diseases at an early stage within the community.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from September to October 2022 in the entire population of mental health cadres in Lamongan Regency (n=224). This study used the Rule of Thumb to determine the sample size, estimating 5x22 characteristics. So, the sample numbered 110 respondents. Inclusion criteria include mental health cadres registered and actively serving at the Community Health Center in Lamongan Regency. In contrast, exclusion criteria relate to sick cadres voluntarily withdrawing from the study for various reasons. The process of selecting samples was conducted using simple random sampling.

The data collection technique is a questionnaire to assess culturally rooted mental health problems through a survey of 25 multiple-choice questions that evaluate early detection capabilities: a) surveillance, b) mobilization, c) referral, and d) documentation. The questionnaire was assessed to ensure its validity and reliability, with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.355 and p-values ranging from 0.373 to 0.951. Additionally, Croanbach's Alpha, a measure of internal consistency, was between 0.700 and 0.999. After obtaining legal permission and ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University (2641-KEPK), samples were selected, and a questionnaire was presented. The author followed up after asking all respondents to complete the questionnaire once. Data were collected and processed using Structural Equation Modeling-Partial Least Square (SEM-PLS) statistical analysis.

Findings

Most participants were female (86.4%) and aged 31 to 40 (46.4%). They mostly had senior high school diplomas (54.5%), were self-employed (45.5%), and had good experience (58.2%; Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of mental health cadre respondents in the Lamongan district community health center area in 2022 (n=110)

All indicators were considered reliable in assessing variables, proven by calculating the Cronbach alpha or Composite Reliability value (Table 2).

Table 2. Reliability test results for a culture-based cadre empowerment model (all variables were valid)

The path analysis revealed significant relationships, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3. The path analysis results

Figure 1. Results on the development of a culture-based cadre empowerment model in increasing the capability to detect early mental disorders

Discussion

Most of the participants in this study were female and had a high school education. Consistent with other studies, 99.6% of mental health professionals are female, and their educational attainment often includes a high school degree [13]. Furthermore, a separate survey indicated that the predominant demographic among health cadres comprises women [14].

The capacity of cadres to identify mental diseases at an early stage (including placing the danger of psychosocial issues, detecting behavioral or symptomatic signs of mental illness, providing supervision, mobilizing resources, making referrals, and maintaining documentation) within the community is adequate. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement in their ability to identify psychosocial risks, detect behavioral or mental symptom indicators, provide supervision, facilitate mobilization, make referrals, and maintain documentation. These findings suggest that empowering cadres through cultural means can enhance their ability to recognize mental problems early. This model comprises formal, informal, family, technology, and cultural elements.

The formation of culture-based cadre empowerment is influenced by formal variables, which are determined by measures of service flow and support from the village head. The service flow is the primary factor determining the level of culture-based cadre empowerment and the subsequent increase in cadre skills. This aligns with empirical research [15]. Mental health cadres and community leaders are crucial in promoting mental health and assisting cadres. Cadres are at the forefront of identifying, managing, and monitoring mental diseases within the community or society. Health service centers equipped with sufficient and superior resources, including facilities, infrastructure, information systems (such as record-keeping or service flow), and a suitable number of health staff, are capable of delivering higher quality services and achieving service coverage targets [16]; Put, the provision of services that sustains and impacts the empowerment of cadres rooted in cultural values.

Village officials serve as an additional indicator of the formal variables that influence the empowerment of culture-based cadres and their ability to enhance their capacities. Cadres are eager to participate voluntarily in implementing and managing health activities within the community. The involvement of health cadres or volunteers in the community is driven by the endorsement of community leaders, particularly when they are acknowledged and trusted by these leaders and esteemed and embraced by the communities they assist while not receiving any remuneration [17]. Additional studies indicate that the level of social support provided to mental health professionals in their work has a notable correlation with the occurrence of individuals with schizophrenia [18]. Consequently, a strong endorsement from the village leader is positively correlated with an enhanced capacity of mental health personnel to identify mental illnesses at an early stage effectively.

Informal elements that contribute to a culture-based cadre's empowerment are determined by gender, education, and experience. Experience has the highest loading factor value, indicating that it has the most impact on measuring informal variables. Mental health cadres acquire expertise through a range of activities, including training. Well-trained cadres will play a significant role in providing mental health care [19]. Additional research indicates discernible disparities between individuals who have received training and those who have not. Specifically, those who have been training exhibit more favorable opinions towards people with mental problems [20].

Furthermore, mental health cadres also require proper instruction to communicate properly. Previous research has demonstrated the crucial role of mental health cadres in providing support and resilience for individuals with mental disorders. These cadres aim to restore the patient's condition, enabling them to regain stability and reintegrate into their families and communities [21]. Cadre training enhances the practical knowledge of cadres in identifying cases, allowing them to play a crucial role in the secondary and primary prevention of mental diseases [22]. Accordingly, the more experienced the cadre is, the higher their ability to recognize mental illnesses early.

Our research indicates that family variables are derived from the responsibilities and duties of the family, which impact the empowerment of culture-based cadres, enhancing their skills. By employing efficient communication strategies, cadres can engage with families, directly impacting their values through culturally oriented cadre empowerment. The ability of cadres to diagnose mental problems early is also influenced by family variables, which involve empowering cadres according to their cultural background and personal values. The family role is the variable with the highest loading factor, indicating that it has the most impact on measuring family aspects. Cadres play a crucial role in conducting direct visits to patients' families to identify mental problems at an early stage. The significance of these cadres is strongly perceived by families and health personnel [23]. According to this, higher-quality family characteristics are positively correlated with the increased ability of mental health professionals to diagnose mental problems at an early stage.

Cultural elements encompass religious and philosophical beliefs, social and familial connections, cultural values and lifestyles, and the influence of cultural upbringing. These factors are crucial in empowering culture-based individuals to enhance their capacities as cadres. The significant impact of social values mostly measures cultural elements. Multiple studies emphasize that mental healthcare in Southeast Asia is significantly shaped by cultural norms, values, and practices [24]. One way to fit the socialization of detection activities to the existing culture in society is by engaging in regular religious practices. Based on [1]. A mental health cadre might fulfill their responsibilities by engaging in community-based activities. According to this, higher-quality cultural variables are positively correlated with the enhanced ability of mental health professionals to identify mental diseases at an early stage.

Our research also indicates that technological aspects, specifically the method and frequency of implementation, impact the empowerment of culture-based cadres, enhancing their capacities. The frequency of occurrence has a significant role in quantifying technical aspects. Technology facilitates the recording, reporting, and monitoring of the development of patients with mental problems, enhancing efficiency and effectiveness. Additionally, it enables cadres to improve their knowledge and abilities [25]. Cadres also employ technology to enhance their digital literacy. They actively utilize technological equipment to acquire expertise and carry out their duties as cadres [26].

Implementing mental health cadre training programs that include comprehensive content on mental health can enhance the skills of cadres, particularly in the area of evaluation [27]. Multiple studies emphasize that cultural norms, values, and practices significantly shape mental healthcare in Southeast Asia. Distinctive components in mental health rehabilitation in Southeast Asia encompass the utilization of cadres as a form of social support and the incorporation of religious activities to enhance the sense of hope among those with schizophrenia [24]. When fulfilling their responsibilities, cadres are prepared for their duties, confident in their ability to effect changes, and offer valuable perspectives on culturally and contextually significant topics. Cadres also experience a sense of prestige and earn the community's confidence in their responsibilities [28]. Cadres enjoy social advantages as they enhance their social standing and garner admiration from the surrounding community, which becomes a source of their pride. Cadres experience a sense of trust as clients and family engage in open discussions on mental health issues. Cadres should prioritize active engagement in long-term mental health initiatives alongside financial incentives, as it is a matter of personal value. The success of future therapy relies on the confidence in the talents and expertise of mental health professionals to identify individuals with mental problems in the community at an early stage. By equipping culturally oriented mental health personnel with authority, it is anticipated that mental health issues can be effectively addressed, and the community will be vigilant to any health-related mental problems that may occur in their vicinity.

Maximizing culture-based empowerment can improve positive outcomes, thereby increasing the ability to identify early signs of mental disorders, such as the detection of psychosocial risks, behavioral indicators, cognitive symptoms, supervision, mobilization, referral, and documentation. The success of future therapy relies on the confidence in the talents and skills of mental health professionals to identify individuals with mental problems in the community at an early stage. By providing authority and resources to mental health professionals who are rooted in certain cultures, the goal is to effectively address mental health issues and ensure that the community is informed about any mental health problems that may occur in their vicinity.

Conclusion

The ability of cadres to detect mental problems at an early stage can be enhanced by promoting a feeling of empowerment.

Acknowledgments: Nothing declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University (2641-KEPK).

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: Aris A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (11%); Yusuf A (Second Author), Introduction Writer (11%); Fitryasari R (Third Author), Introduction Writer (11%); Suhariyati S (Fourth Author), Methodologist (11%); Ubudiyah M (Fifth Author), Methodologist (11%); Faridah VN (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (11%); Kusumaningrum AT (Seventh Author), Assistant Researcher (11%); Sholikah S (Eighth Author), Discussion Writer (11%)

Funding/Support: Nothing declared by the authors.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2023/12/4 | Accepted: 2024/01/12 | Published: 2024/01/30

Received: 2023/12/4 | Accepted: 2024/01/12 | Published: 2024/01/30

References

1. Alemi Q, Panter-Brick C, Oriya S, Ahmady M, Alimi AQ, Faiz H, et al. Afghan mental health and psychosocial well-being: Thematic review of four decades of research and interventions. BJPsych Open. 2023;9(4):e125. [Link] [DOI:10.1192/bjo.2023.502]

2. Greene EM. The mental health industrial complex: A study in three cases. J Humanist Psychol. 2019;63(1):1-19. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0022167819830516]

3. Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2016;46(14):2955-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0033291716001665]

4. Colizzi M, Lasalvia A, Ruggeri M. Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health : Is it time for a multidisciplinary and transdiagnostic model for care ?. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:23. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9]

5. Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Health. Indonesian Health Profile 2013. Jakarta: Indonesian Ministry of Health; 2014. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan RI; 2014. [Indonesian] [Link]

6. Alamsyah T, Candra A, Marianthi D. The "Pague Gampong" model in Aceh culture on drug handling: A qualitative study. Int J Health Sci. 2020;4(3):49-59. [Link] [DOI:10.29332/ijhs.v4n3.458]

7. Nufus F. Religion and local culture: The struggle between religions and local culture in Balun Turi Lamongan [dissertation]. Surabaya: UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya; 2019. [Indonesian] [Link]

8. Sokolov NA, Reshetnikov VA, Tregubov VN, Sadkovaya OS, Mikerova MS, Drobyshev DA. Developing characteristics and competences of a health care manager: Literature review. Exp Appl Biomed Res (EABR). 2019;20(2):65-74. [Link] [DOI:10.2478/sjecr-2019-0036]

9. Ahrens J, Kokota D, Mafuta C, Konyani M, Chasweka D, Mwale O, et al. Implementing a mhGAP-based training and supervision package to improve healthcare workers ' competencies and access to mental health care in Malawi. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:11. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13033-020-00345-y]

10. Nakku JEM, Rathod SD, Garman EC, Ssebunnya J, Kangere S, Silva MD, et al. Evaluation of the impacts of a district-level mental health care plan on contact coverage, detection and individual outcomes in rural Uganda : A mixed methods approach. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13:63. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13033-019-0319-2]

11. Jahan I, Huynh T, Mass G. The influence of organisational culture on employee commitment: An empirical study on civil service officials in Bangladesh. South Asian J Human Resour Manag. 2022;9(2):271-300. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/23220937221113994]

12. Magaña D. Cultural competence and metaphor in mental healthcare interactions: A linguistic perspective. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(12):2192-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.010]

13. Marlita CY, Usman S, Marthoenis, Syahputra I, Nurjannah. The roles of health cadres in implementing mental health programs in Indonesia. Int J Nurs Educ. 2022;14(1):9-18. [Link] [DOI:10.37506/ijone.v14i1.17730]

14. Risniawati, Kusumaningrum T, Nastiti AA. Factors related to cadre perceptions and behavior in promoting family planning at community health centers based on the Health Promotion Model (HPM). Europ J Mol Clin Med. 2020;7(5):741-5. [Link]

15. Ramos NJ. Pathologizing the crisis: Psychiatry, policing, and racial liberalism in the long community mental health movement. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2019;74(1):57-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jhmas/jry043]

16. Firdaus MK, Basabih M. Service of people with psychiatric problems (ODMK) at the Pasar Baru health center and Pabuaran Tumpeng health center in Tangerang city in 2022: A comparative study. J Indones Health Policy Admin. 2022;7(3):273. [Link] [DOI:10.7454/ihpa.v7i3.6110]

17. Olaniran A, Madaj B, Bar-Zeev S, Banke-Thomas A, van den Broek N. Factors influencing motivation and job satisfaction of community health workers in Africa and Asia-A multi-country study. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37(1):112-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/hpm.3319]

18. Maryam D, Arisara G. Factors influencing the role of mental health cadres in handling patients. Public Health Sebelas April. 2023;2(1):32-40. [Link]

19. Marlita CY, Usman S, Marthoenis, Syahputra I, Nurjannah. An exploration of the Indonesian lay mental health workers' (cadres) experiences in performing their roles in community mental health services: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Helth Syst. 202;18(1):3. [Link]

20. Wardaningsih S, Kageyama T. Perception of community health workers in Indonesia toward patients with mental disorders. Int J Public Health Sci (IJPHS). 2016;5(1):27-35. [Link] [DOI:10.11591/ijphs.v5i1.4759]

21. Rukmini CT, Syafiq M. Family resilience as caregivers of schizophrenic patients with relapse. Character: Jurnal Penelitian Psikologi. 2019;6(2):1-8. [Indonesian] [Link]

22. Susanti H, Brooks H, Yulia I, Windarwati HD, Yuliastuti E, Hasniah H, et al. An exploration of the roles of lay mental health workers (cadres) in community mental health services in Indonesia: A qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2024;18:3. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13033-024-00622-0]

23. Hothasian JM, Suryawati C, Fatmasari EY. Evaluation of the implementation of the mental health program at the Bandarharjo health center, Semarang city in 2018. Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat. 2019;7(1):75-83. [Indonesian] [Link]

24. Murwasuminar B, Munro I, Recoche K. Mental health recovery for people with schizophrenia in Southeast Asia: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2023;30(4):620-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jpm.12902]

25. Husni, Ali M. IT-based mental health posyandu training on cadre knowledge and skill levels in Bongkot village. J Technol Inform. 2022;1(1):2-5. [Link]

26. Hufad A, Purnomo, Sutarni N, Rahmat A. Digital literacy of women as the cadres of community empowerment in rural areas. Int J Innov, Creat Chang. 2019;9(7):276-88. [Link]

27. Subardjo RYS, Rohmadanai ZV. Development of early mental health detection skills for regional mental health cadres. Urecol J. Part H: Social, Art, and Humanities. 2021;1(1):32-8. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.53017/ujsah.50]

28. Dev S, Lincoln AK, Shidhaye R. Evidence to practice for mental health task-sharing: Understanding readiness for change among accredited social health activists in Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh, India. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2022;49(3):463-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10488-021-01176-w]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |