Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 85-89 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sohrabi Z, Rasouli D, Nouri Khaneghah Z, Ramezanpour E, Nosrati S, Zhianifard A. Comparing the Effect of Virtual Doughnut Educational Rounds and Online Lecture Methods on the Learning and Satisfaction of Operating Room Nursing Students; A Self-Directed Learning Method. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :85-89

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73229-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-73229-en.html

1- “Center for Educational Research in Medical Sciences (CERMS)” and “Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine”, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Teaching Rounds [Mesh], Nursing Student [MeSH], Self-Directed Learning as Topic [MeSH], Doughnut Education [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 576 kb]

(3163 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1324 Views)

Full-Text: (125 Views)

Introduction

One of the primary objectives of medical and paramedical education is to equip students to join the medical workforce, ultimately producing competent professionals for society. Effective clinical training is crucial as it allows students to gain valuable experience, emphasizing the significance of clinical education [1-3]. Various clinical (work) and non-clinical (educational) rounds exist in hospital settings, including grand rounds, health rounds, multidisciplinary rounds, and conference-based rounds, each defined differently by scholars. Specifically, conference-based rounds, also known as educational rounds, involve discussions between professors and students about a patient's condition or disease, culminating in a conference presentation. This approach, combined with clinical rounds during apprenticeship and internship phases, enhances student progression toward professionalism [4]. Research highlights that non-clinical rounds often lack proper planning and face challenges such as discrepancies between theoretical and practical learning, student overcrowding, and the stress of conducting rounds in busy clinical settings like operating room corridors and wards, suggesting a need for improvement [5-7]. Consequently, the adoption of innovative, active, and self-directed educational methods for non-clinical rounds is essential. The Doughnut educational round, a self-directed learning strategy, is one such method. Self-directed learning is a vital skill for students in clinical disciplines [8]. The Doughnut round, applied in medical education and nursing, covers various subjects like surgery, anatomy, pediatrics, emergency medicine, and more, benefiting undergraduate students and offering the potential for broader application by educators [9]. The Doughnut educational round, characterized by its self-directed learning approach and unique format, offers numerous benefits. These include enabling structured discussions among multiple participants within a brief period, boosting learners' self-confidence, enhancing communication skills, fostering motivation for knowledge acquisition, and encouraging active participation in the learning process. Furthermore, this method is appreciated for its game-based and entertaining aspects [8, 10]. With the rapid advancements in technology today, there's a pressing need for innovation in educational methodologies to keep pace with global developments. Virtual education emerges as a pivotal solution, offering flexible learning and teaching, enhanced learning precision, cost-effectiveness, timely updates, and easy access to educational resources. Applying virtual education to conduct educational rounds addresses various challenges, such as overcrowding in hospitals, as well as the tension and stress often encountered in the bustling corridors of wards and operating rooms [11, 12]. Given that learners are central to any educational system, soliciting their satisfaction and feedback in all forms of education, including non-clinical rounds, is crucial for improving educational quality [13]. The congestion caused by students from various disciplines like anesthesiology, surgical technology, and midwifery in the operating room often limits the space available and disrupts the educational round process, depriving students of valuable learning opportunities. Therefore, this study introduces the Doughnut round in a virtual format as an innovative educational approach for nursing students in the operating room, aiming to assess the impact of this method on their learning and satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

This study was a quasi-experimental design featuring a pre-test-post-test format, incorporating both online lectures and virtual Doughnut educational rounds. Seventy senior-year undergraduate nursing students specializing in operating room practices were selected through a census method and then randomly allocated into two groups via Excel software. The group engaged in virtual Doughnut educational rounds was further split into two smaller groups, A and B, using the virtual Doughnut round method, while the online lecture group was divided using the virtual lecture method with an interactive Q&A session into two smaller groups, C and D, each comprising 35 participants.

Inclusion criteria included obtaining informed consent from participants and the completion of prerequisite courses before semester 7. Exclusion criteria encompassed lack of cooperation, reluctance to participate, incomplete questionnaires, failure in any of the prerequisite courses listed in the inclusion criteria, and absence from more than two sessions. Moreover, the educational content was identical across both the control and intervention groups.

The setting for this investigation was among students of the operating room department at the Iran University of Medical Sciences. Participants were students who had already completed prerequisite courses in Gastrointestinal Surgery Technology and Otorhinolaryngology Surgery Technology, and had provided informed consent. In both the online lecture and virtual Doughnut educational rounds groups, the educational material covered included surgical techniques, perioperative care, and the use of operating room tools and equipment pertinent to ear, nose, throat, digestive, and endocrine surgeries.

To assess the student's knowledge of specific topics, a pre-test was administered to all four groups one day before the first intervention session. This test comprised 20 multiple-choice questions developed based on a structured blueprint

The schedule for delivering educational content and study materials in the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group was established in advance by the instructor and with the student's consent. Members of this group were tasked with creating and submitting 10 multiple-choice questions, complete with correct answers, for each session. These were sent to the relevant instructor for approval one day before the Doughnut round. The instruction method in the virtual Doughnut rounds involved holding one-hour sessions for groups A and B separately on social media platforms, conducted on the first two days of the week, following the pre-test. At each session's start, a student randomly selected another student to pose a question to, awarding a score from 1 to 3 based on their satisfaction with the response before providing the correct answer. If the answering student was correct, they chose the next participant; otherwise, the questioning student selected the next. This process continued until all content was covered. Any student eliminated after giving three incorrect answers remained in the virtual space as an active listener. The instructor actively listened throughout the session, monitoring responses, and removing any student who answered incorrectly more than three times. Concurrently, the same topics were presented to groups C and D via online lectures, incorporating a Q&A session, over two days later in the same week. The training spanned three months or 12 weeks, totaling 48 sessions, with 24 sessions each for the virtual Doughnut educational rounds and the online lecture groups. A post-test was conducted a week after the last session to evaluate the educational impact.

The "satisfaction with teaching method" questionnaire was utilized to gauge the students' satisfaction levels with the instructional approach. Momeni Danaei et al., who originally employed this questionnaire in their research, confirmed its validity through the consensus of eight field experts and reported a reliability coefficient of 0.89 via Cronbach's alpha [14]. The questionnaire allowed students to express their satisfaction with the teaching method by selecting from five options on the Likert scale, ranging from "completely disagree" to "completely agree" across 18 questions. Scores ranging from 1 to 5 were allocated to each option on the Likert scale, with the highest score (5 points) given to "completely agree" in statements that highlighted the advantages of the teaching method, while "completely disagree" received the highest score in statements indicating negative aspects. The total score for each respondent, ranging from 18 to 90, was determined by summing the points from their responses. The content validity of the questionnaire in this study was evaluated by an expert panel (CVI=0.79, CVR=0.69), and its reliability was reaffirmed with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.80.

Statistics

Data collection and analysis were conducted using SPSS software version 19, employing descriptive statistical tests and t-tests for analysis.

Findings

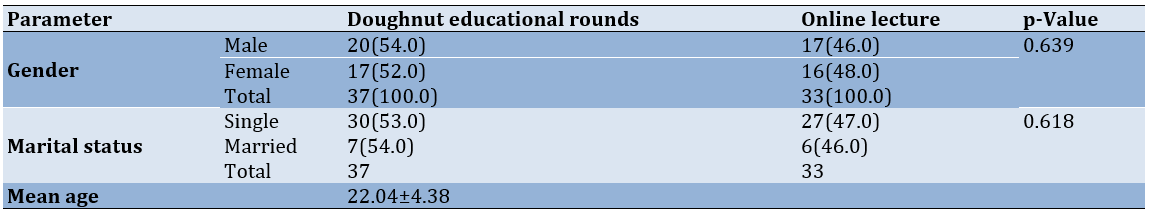

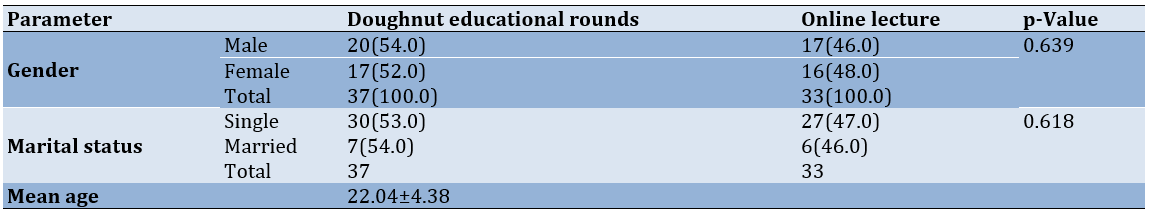

In this study, 70 nursing students from the 7th and 8th semesters of the operating room program participated, with an average age of 22 years. Of these, 52.85% (37 participants) were male and 47.15% (33 participants) were female, with the majority, 82% (57 participants), being single (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean age and the frequency of gender and marital status of the participants

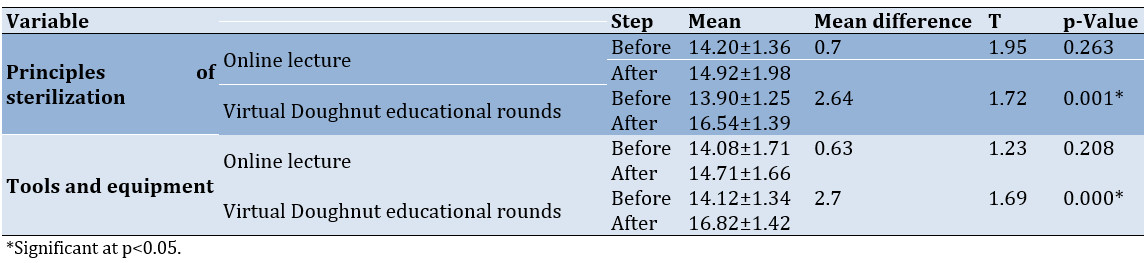

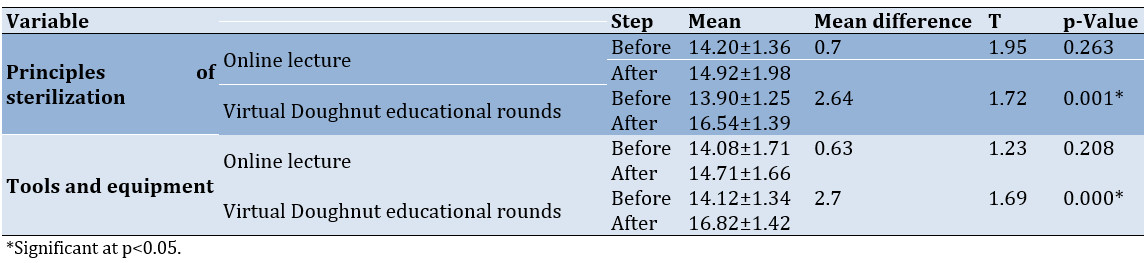

There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding age, gender, and marital status. The distribution of pre-test and post-test scores for both the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group was found to be normal according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The independent t-test revealed no statistically significant difference between the pre-test scores of the two groups by subjects (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the pre-test scores between the two groups, with both groups displaying nearly identical averages. Furthermore, the scores from both courses are very similar, and no statistically significant difference was observed in the post-test scores, although the average scores in the post-test differed.

Table 2. Comparison of the pre-test scores between the online lecture and virtual Doughnut educational rounds groups by subjects based using the independent t-test

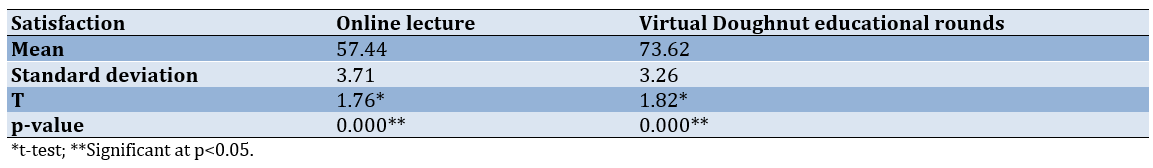

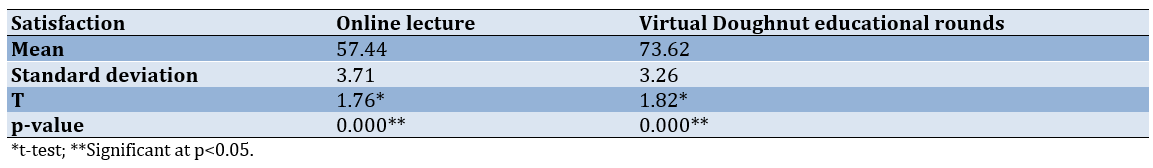

Additionally, the results indicated that students trained using the Doughnut method expressed greater satisfaction compared to those who received instruction through the lecture method (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of satisfaction scores in two virtual Doughnut educational rounds and online lecture groups

Discussion

The results of the independent t-test revealed no statistically significant difference between the pre-test scores of the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group across both subjects. This outcome supports the study since it confirms that there is no difference in the level of prerequisite knowledge between the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group.

Based on the t-test, a statistically significant difference was observed in the post-test scores between the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group in both subjects. The virtual Doughnut round method, as a form of self-directed learning, proved to be more effective than traditional lectures in both courses. The findings from Zhang et al.'s research indicated that implementing the Doughnut round increased learning and self-confidence among first-year medical students in lower anatomy studies [8]. Similarly, Satyajit et al.'s study found that 59% of students reported an increase in knowledge following the Doughnut educational round [10]. These studies corroborate the findings of the current research.

Given that the Doughnut round method is a form of self-directed learning [15], this study illustrates that self-directed learning has a more significant impact on learners' rate of learning than traditional teacher-centered methods, such as lectures. In line with this, Pai et al.'s research demonstrated that for first-year medical students, self-directed learning is an effective educational strategy for studying physiology [16]. Additionally, Vinay and Veerapu's study indicated that the self-directed learning method was more effective than the lecture method in teaching embryology to first-year medical students, with students showing a higher receptivity to it [17]. Palve's research also revealed that self-directed learning was more effective than the lecture method in presenting concepts related to heart and respiratory physiology [18].

In the current study, the results demonstrated that satisfaction with the implementation of the virtual Doughnut educational round was statistically significantly higher than with traditional lectures (p=0.001). In this context, Satyajit et al.'s study found that 95.33% of students enjoyed participating in the Doughnut round, and 75.66% reported that this learning method increased their self-confidence [10]. Furthermore, Hill et al.'s research indicated that first-year medical students viewed the self-directed learning method as a valuable learning experience, which aligns with the findings of the present study. This is because the Doughnut round is considered a model of self-directed learning, which was implemented online in our research [19]. Bergman et al. also highlighted that incorporating principles of collaborative and self-directed learning in anatomy education enhances student satisfaction levels [20], and Lollis found that nursing students with higher grades, who were ready for self-directed learning, reported greater satisfaction and self-confidence [21].

This study utilized the virtual Doughnut round method for conducting an educational session. It was found to be more effective than the lecture method in teaching nursing students in the operating room field, with students expressing greater satisfaction with this method compared to traditional lectures. Therefore, it is recommended to employ this teaching method in conjunction with clinical rounds for operating room nursing students, especially those in their final year, and to explore its effectiveness in other paramedical fields through further research.

Conclusion

The virtual Doughnut round method is more effective than traditional lectures for teaching operating room nursing students, particularly those in their senior year.

Acknowledgments: The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Iran University of Medical Sciences for the material and moral support provided during the approval and implementation of this study. We also thank all students, teachers, and the head of the operating room department at the Iran University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation and participation in this project.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.521.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Sohrabi Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (35%); Rasouli D (Second Author), Statistical Analyst (20%); Nouri Khaneghah Z (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Ramezanpour E (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Nosrati S (Fifth Author), Discussion Writer (5%); Zhianifard A (Sixth Author), Discussion Writer (5%)

Funding/Support: The funding for this research was provided by the Iran University of Medical Sciences

One of the primary objectives of medical and paramedical education is to equip students to join the medical workforce, ultimately producing competent professionals for society. Effective clinical training is crucial as it allows students to gain valuable experience, emphasizing the significance of clinical education [1-3]. Various clinical (work) and non-clinical (educational) rounds exist in hospital settings, including grand rounds, health rounds, multidisciplinary rounds, and conference-based rounds, each defined differently by scholars. Specifically, conference-based rounds, also known as educational rounds, involve discussions between professors and students about a patient's condition or disease, culminating in a conference presentation. This approach, combined with clinical rounds during apprenticeship and internship phases, enhances student progression toward professionalism [4]. Research highlights that non-clinical rounds often lack proper planning and face challenges such as discrepancies between theoretical and practical learning, student overcrowding, and the stress of conducting rounds in busy clinical settings like operating room corridors and wards, suggesting a need for improvement [5-7]. Consequently, the adoption of innovative, active, and self-directed educational methods for non-clinical rounds is essential. The Doughnut educational round, a self-directed learning strategy, is one such method. Self-directed learning is a vital skill for students in clinical disciplines [8]. The Doughnut round, applied in medical education and nursing, covers various subjects like surgery, anatomy, pediatrics, emergency medicine, and more, benefiting undergraduate students and offering the potential for broader application by educators [9]. The Doughnut educational round, characterized by its self-directed learning approach and unique format, offers numerous benefits. These include enabling structured discussions among multiple participants within a brief period, boosting learners' self-confidence, enhancing communication skills, fostering motivation for knowledge acquisition, and encouraging active participation in the learning process. Furthermore, this method is appreciated for its game-based and entertaining aspects [8, 10]. With the rapid advancements in technology today, there's a pressing need for innovation in educational methodologies to keep pace with global developments. Virtual education emerges as a pivotal solution, offering flexible learning and teaching, enhanced learning precision, cost-effectiveness, timely updates, and easy access to educational resources. Applying virtual education to conduct educational rounds addresses various challenges, such as overcrowding in hospitals, as well as the tension and stress often encountered in the bustling corridors of wards and operating rooms [11, 12]. Given that learners are central to any educational system, soliciting their satisfaction and feedback in all forms of education, including non-clinical rounds, is crucial for improving educational quality [13]. The congestion caused by students from various disciplines like anesthesiology, surgical technology, and midwifery in the operating room often limits the space available and disrupts the educational round process, depriving students of valuable learning opportunities. Therefore, this study introduces the Doughnut round in a virtual format as an innovative educational approach for nursing students in the operating room, aiming to assess the impact of this method on their learning and satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

This study was a quasi-experimental design featuring a pre-test-post-test format, incorporating both online lectures and virtual Doughnut educational rounds. Seventy senior-year undergraduate nursing students specializing in operating room practices were selected through a census method and then randomly allocated into two groups via Excel software. The group engaged in virtual Doughnut educational rounds was further split into two smaller groups, A and B, using the virtual Doughnut round method, while the online lecture group was divided using the virtual lecture method with an interactive Q&A session into two smaller groups, C and D, each comprising 35 participants.

Inclusion criteria included obtaining informed consent from participants and the completion of prerequisite courses before semester 7. Exclusion criteria encompassed lack of cooperation, reluctance to participate, incomplete questionnaires, failure in any of the prerequisite courses listed in the inclusion criteria, and absence from more than two sessions. Moreover, the educational content was identical across both the control and intervention groups.

The setting for this investigation was among students of the operating room department at the Iran University of Medical Sciences. Participants were students who had already completed prerequisite courses in Gastrointestinal Surgery Technology and Otorhinolaryngology Surgery Technology, and had provided informed consent. In both the online lecture and virtual Doughnut educational rounds groups, the educational material covered included surgical techniques, perioperative care, and the use of operating room tools and equipment pertinent to ear, nose, throat, digestive, and endocrine surgeries.

To assess the student's knowledge of specific topics, a pre-test was administered to all four groups one day before the first intervention session. This test comprised 20 multiple-choice questions developed based on a structured blueprint

The schedule for delivering educational content and study materials in the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group was established in advance by the instructor and with the student's consent. Members of this group were tasked with creating and submitting 10 multiple-choice questions, complete with correct answers, for each session. These were sent to the relevant instructor for approval one day before the Doughnut round. The instruction method in the virtual Doughnut rounds involved holding one-hour sessions for groups A and B separately on social media platforms, conducted on the first two days of the week, following the pre-test. At each session's start, a student randomly selected another student to pose a question to, awarding a score from 1 to 3 based on their satisfaction with the response before providing the correct answer. If the answering student was correct, they chose the next participant; otherwise, the questioning student selected the next. This process continued until all content was covered. Any student eliminated after giving three incorrect answers remained in the virtual space as an active listener. The instructor actively listened throughout the session, monitoring responses, and removing any student who answered incorrectly more than three times. Concurrently, the same topics were presented to groups C and D via online lectures, incorporating a Q&A session, over two days later in the same week. The training spanned three months or 12 weeks, totaling 48 sessions, with 24 sessions each for the virtual Doughnut educational rounds and the online lecture groups. A post-test was conducted a week after the last session to evaluate the educational impact.

The "satisfaction with teaching method" questionnaire was utilized to gauge the students' satisfaction levels with the instructional approach. Momeni Danaei et al., who originally employed this questionnaire in their research, confirmed its validity through the consensus of eight field experts and reported a reliability coefficient of 0.89 via Cronbach's alpha [14]. The questionnaire allowed students to express their satisfaction with the teaching method by selecting from five options on the Likert scale, ranging from "completely disagree" to "completely agree" across 18 questions. Scores ranging from 1 to 5 were allocated to each option on the Likert scale, with the highest score (5 points) given to "completely agree" in statements that highlighted the advantages of the teaching method, while "completely disagree" received the highest score in statements indicating negative aspects. The total score for each respondent, ranging from 18 to 90, was determined by summing the points from their responses. The content validity of the questionnaire in this study was evaluated by an expert panel (CVI=0.79, CVR=0.69), and its reliability was reaffirmed with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.80.

Statistics

Data collection and analysis were conducted using SPSS software version 19, employing descriptive statistical tests and t-tests for analysis.

Findings

In this study, 70 nursing students from the 7th and 8th semesters of the operating room program participated, with an average age of 22 years. Of these, 52.85% (37 participants) were male and 47.15% (33 participants) were female, with the majority, 82% (57 participants), being single (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean age and the frequency of gender and marital status of the participants

There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding age, gender, and marital status. The distribution of pre-test and post-test scores for both the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group was found to be normal according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The independent t-test revealed no statistically significant difference between the pre-test scores of the two groups by subjects (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the pre-test scores between the two groups, with both groups displaying nearly identical averages. Furthermore, the scores from both courses are very similar, and no statistically significant difference was observed in the post-test scores, although the average scores in the post-test differed.

Table 2. Comparison of the pre-test scores between the online lecture and virtual Doughnut educational rounds groups by subjects based using the independent t-test

Additionally, the results indicated that students trained using the Doughnut method expressed greater satisfaction compared to those who received instruction through the lecture method (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of satisfaction scores in two virtual Doughnut educational rounds and online lecture groups

Discussion

The results of the independent t-test revealed no statistically significant difference between the pre-test scores of the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group across both subjects. This outcome supports the study since it confirms that there is no difference in the level of prerequisite knowledge between the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group.

Based on the t-test, a statistically significant difference was observed in the post-test scores between the online lecture group and the virtual Doughnut educational rounds group in both subjects. The virtual Doughnut round method, as a form of self-directed learning, proved to be more effective than traditional lectures in both courses. The findings from Zhang et al.'s research indicated that implementing the Doughnut round increased learning and self-confidence among first-year medical students in lower anatomy studies [8]. Similarly, Satyajit et al.'s study found that 59% of students reported an increase in knowledge following the Doughnut educational round [10]. These studies corroborate the findings of the current research.

Given that the Doughnut round method is a form of self-directed learning [15], this study illustrates that self-directed learning has a more significant impact on learners' rate of learning than traditional teacher-centered methods, such as lectures. In line with this, Pai et al.'s research demonstrated that for first-year medical students, self-directed learning is an effective educational strategy for studying physiology [16]. Additionally, Vinay and Veerapu's study indicated that the self-directed learning method was more effective than the lecture method in teaching embryology to first-year medical students, with students showing a higher receptivity to it [17]. Palve's research also revealed that self-directed learning was more effective than the lecture method in presenting concepts related to heart and respiratory physiology [18].

In the current study, the results demonstrated that satisfaction with the implementation of the virtual Doughnut educational round was statistically significantly higher than with traditional lectures (p=0.001). In this context, Satyajit et al.'s study found that 95.33% of students enjoyed participating in the Doughnut round, and 75.66% reported that this learning method increased their self-confidence [10]. Furthermore, Hill et al.'s research indicated that first-year medical students viewed the self-directed learning method as a valuable learning experience, which aligns with the findings of the present study. This is because the Doughnut round is considered a model of self-directed learning, which was implemented online in our research [19]. Bergman et al. also highlighted that incorporating principles of collaborative and self-directed learning in anatomy education enhances student satisfaction levels [20], and Lollis found that nursing students with higher grades, who were ready for self-directed learning, reported greater satisfaction and self-confidence [21].

This study utilized the virtual Doughnut round method for conducting an educational session. It was found to be more effective than the lecture method in teaching nursing students in the operating room field, with students expressing greater satisfaction with this method compared to traditional lectures. Therefore, it is recommended to employ this teaching method in conjunction with clinical rounds for operating room nursing students, especially those in their final year, and to explore its effectiveness in other paramedical fields through further research.

Conclusion

The virtual Doughnut round method is more effective than traditional lectures for teaching operating room nursing students, particularly those in their senior year.

Acknowledgments: The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Iran University of Medical Sciences for the material and moral support provided during the approval and implementation of this study. We also thank all students, teachers, and the head of the operating room department at the Iran University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation and participation in this project.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.521.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Sohrabi Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (35%); Rasouli D (Second Author), Statistical Analyst (20%); Nouri Khaneghah Z (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Ramezanpour E (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Nosrati S (Fifth Author), Discussion Writer (5%); Zhianifard A (Sixth Author), Discussion Writer (5%)

Funding/Support: The funding for this research was provided by the Iran University of Medical Sciences

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2024/01/2 | Accepted: 2024/03/5 | Published: 2024/03/20

Received: 2024/01/2 | Accepted: 2024/03/5 | Published: 2024/03/20

References

1. Wilson G. Redesigning oR orientation. AORN J. 2012;95(4):453-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.aorn.2012.01.022]

2. Kim KH. Clinical competence among senior nursing students after their preceptorship experiences. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23(6):369-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.01.019]

3. Baraz Pordanjani S, Fereidooni Moghadam M, Loorizade MR. Clinical education status according to the nursing and midwifery students point of view Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Strides Dev Med Educ. 2009;5(2):102-12. [Persian] [Link]

4. Angelopoulou P, Panagopoulou E. Non-clinical rounds in hospital settings: A scoping review. J Health Organ Manag. 2019;33(5):605-16. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/JHOM-09-2018-0244]

5. Rajasoorya C. Clinical ward rounds-challenges and opportunities. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2016;45(4):152-6. [Link] [DOI:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.V45N4p152]

6. Yosefi M. Clinical round anxiety. Horiz Med Educ Dev. 2016;6(2):39-40. [Persian] [Link]

7. Dolcourt JL, Zuckerman G, Warner K. Learners' decisions for attending Pediatric Grand Rounds: A qualitative and quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:26. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1472-6920-6-26]

8. Zhang Y, Zerafa Simler MA, Stabile I. Supported self-directed learning of clinical anatomy: A pilot study of Doughnut rounds. Eur J Anat. 2017;21(4):319-24. [Link]

9. Fleiszer D, Fleiszer T, Russell R. Doughnut rounds: A self-directed learing approach to teaching critical care in surgery. Med Teach. 1997;19(3):190-3. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/01421599709019380]

10. Satyajit S, Hironmoy R. Students' perception on 'Doughnut rounds' in self directed learning of anatomy. Int J Sci Res. 2019;8(12). [Link]

11. Dung DTH. The advantages and disadvantages of virtual learning. IOSR J Res Method Educ. 2020;10(3 Ser 5):45-8. [Link]

12. Novintan S, Mann S, Hazemi-Jebelli Y. Simulations and virtual learning supporting clinical education during the COVID 19 pandemic. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:649-50. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/AMEP.S276699]

13. Rezaei B. Quality of clinical education (a case study in the viewpoints of nursing and midwifery students in Islamic Azad University, Falavarjan Branch). Educ Strateg Med Sci. 2016;9(2):106-17. [Persian] [Link]

14. Momeni Danaei S, Zarshenas L, Oshagh M, Omid Khoda SM. Which method of teaching would be better cooperative or lecture?. Iran J Med Educ. 2011;11(1):24-31. [Persian] [Link]

15. Nayak M, Belle V. Various methods of Self-directed learning in medical education. MediSys J Med Sci. 2020;1(1):15-22. [Link] [DOI:10.51159/MediSysJMedSci.2020.v01i01.004]

16. Pai KM, Rao KR, Punja D, Kamath A. The effectiveness of self-directed learning (SDL) for teaching physiology to first-year medical students. Australas Med J. 2014;7(11):448-53. [Link] [DOI:10.4066/AMJ.2014.2211]

17. Vinay G, Veerapu N. A comparison of self-directed learning and lecture methods for teaching embryology among first year medical students. Sch Int J Anat Physiol. 2019;2(12):352-5. [Link] [DOI:10.36348/sijap.2019.v02i12.003]

18. Palve S, Palve S. Comparative study of self-directed learning and traditional teaching method in understanding cardio-respiratory physiology among medical undergraduates. Biomedicine. 2022;42(1):138-42. [Link] [DOI:10.51248/.v42i1.662]

19. Hill M, Peters M, Salvaggio M, Vinnedge J, Darden A. Implementation and evaluation of a self-directed learning activity for first-year medical students. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1717780. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10872981.2020.1717780]

20. Bergman EM, Sieben JM, Smailbegovic I, De Bruin ABH, Scherpbier AJJA, Van Der Vleuten CPM. Constructive, collaborative, contextual, and self-directed learning in surface anatomy education. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6(2):114-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ase.1306]

21. Lollis MAW. Self-directed learning readiness, student satisfaction, self-confidence, and persistence in associate degree nursing students [dissertation]. Minneapolis: Capella University; 2016. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |