Volume 12, Issue 4 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(4): 589-596 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shafei E, Rakhshanderou S, Ghaffari M, Hatami H. Socio-Psychological Predictors of Students' Preventive Behaviors Against Pediculosis; the Health Belief Model Approach. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (4) :589-596

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72959-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72959-en.html

1- Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 629 kb]

(2025 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (859 Views)

Full-Text: (162 Views)

Introduction

Public health and well-being are of paramount importance in any society, as the progress of communities is closely tied to the overall health of their individuals. Among the factors that threaten community health, infestations by insects, particularly ectoparasites, remain a significant health issue despite advancements in healthcare and medical sciences, continuing to pose a health challenge [1]. Lice, specifically Anoplura (Phthiraptera), are obligate blood-sucking parasites that infest mammals, including humans. Over 550 species have been described worldwide, many of which are host-specific, targeting particular mammals [2]. Infestations of lice on the body, head, or pubic area are referred to as pediculosis [3]. Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis), body lice (Pediculus humanus corporis), and pubic lice (Phthirus pubis) are all blood-sucking ectoparasites that affect humans [4]. Among these, body lice are known to transmit diseases, such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever, while head lice are not known to be disease vectors.

In recent years, the prevalence of body lice has decreased, particularly in affluent societies, due to improved living standards. However, head lice infestations continue to be reported worldwide. Although head lice have a global distribution, they are more commonly found in temperate regions, and their annoyance and discomfort can be compared to mosquito-related problems in tropical areas. Factors, such as population growth and poor hygiene exacerbate lice infestations, with a higher prevalence observed in densely populated, impoverished communities. These infestations affect all social and economic strata during epidemics [2, 3]. The prevalence of head lice infestations in children aged 5 to 13 years is higher than in other age groups, with a greater incidence in girls than in boys. Schools, especially elementary schools, play a significant role in the occurrence of head lice epidemics [5]. Among children and women, having a dense head of hair is associated with a higher risk of lice infestation compared to other age groups [6]. The prevalence of lice infestations in elementary schools in developed countries is estimated to be between 2% and 10% [7]. Unfortunately, lice infestations in Iran have emerged as a public health issue alongside other infectious diseases in some regions due to factors such as uncontrolled population growth, rural-to-urban migration, settlement in marginalized areas, and the establishment of satellite towns with minimal sanitary facilities [8]. It is estimated that lice infestations affect between 6 to 12 million individuals worldwide annually [9-14]. Studies conducted outside of Iran have reported the prevalence of head lice infestations among elementary school students as a parameter. For example, in 2011, a study conducted among 940 students in a rural area of Yucatan, Mexico, reported a prevalence of 13.6% for head lice infestations [15]. In 2012, the prevalence of head lice infestations in Thailand was reported to be 32.23% [16]. Results from studies conducted in 2015 in the European :union: and Norway have reported head lice infestation prevalence rates of 3.44% and 1.2%, respectively [17]. The prevalence of head lice infestations in Iran varies across different regions. For instance, the prevalence of head lice infestation in female elementary school students in Qom is 6.7% [9], while in Sari County, it is 65.1% [14]. In the counties of Tonekabon and Pakdasht, and in Qom Province, the reported prevalence rates are 74.5%, 3.1%, and 3.13%, respectively [1, 9, 18]. In Kalaleh and Bonab counties, the rates are 28.6% and 82.2%, respectively [19, 20]. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2015 to determine the prevalence of head lice among Iranian elementary school students reported a prevalence of 1.6% for boys and 8.8% for girls [3]. Individuals affected by pediculosis may experience irritation, sensitivity, and fatigue due to the entry of foreign insect saliva proteins into the host’s body through insect bites. The repeated injection of louse saliva can lead to severe allergies, such as intense itching. Scratching the site of the bite can result in skin inflammation and may also lead to secondary infections, such as fungal and bacterial infections, which can cause the development of yellow ulcers and swelling of lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) around the neck and behind the ears [9]. In addition to the health issues associated with pediculosis, individuals affected by this condition may also face social difficulties, including feelings of shame and inferiority, psychological disturbances, depression, insomnia, decreased academic performance, and a loss of social status among their peers [10].

The most significant mode of transmission for infestation is through direct head-to-head contact with an infected person. Additionally, infestation can occur indirectly through contact with infested clothing, personal items (combs, towels, etc.), or bed and furniture covers infested with lice or eggs [11]. The most important prevention methods for avoiding head lice infestation include practicing personal hygiene (particularly regular bathing), refraining from sharing personal items (such as combs, brushes, and hats), promptly reporting cases of infestation to the nearest healthcare facility, using insecticidal shampoos by those affected and their family members, and educating the community in infested areas while promoting overall hygiene [12].

One of the most effective and widely used psychosocial approaches for describing health-related behaviors, which has been successfully applied to various health-related topics for nearly half a century, is the health belief model (HBM). The HBM is a psychological framework that describes and predicts health behaviors by emphasizing individuals’ attitudes and beliefs. It was developed in the 1950s by a group of social psychologists to explain the reasons behind people’s lack of participation in disease prevention or diagnosis programs [13]. Given the importance and vulnerability of elementary school-aged children, as well as the high prevalence of head lice infestations in the research area, along with the physical, psychological, social, and economic consequences associated with it, this study aimed to investigate the determinants of preventive behaviors against pediculosis in second-grade students in urban areas of Heris County, East Azerbaijan Province of Iran, using the theoretical framework of the HBM for the first time.

Instrument and Methods

Study design and sample

This descriptive-analytical correlational study was conducted on 1,000 elementary school students, both girls and boys, in urban areas of Heris County in 2019-2020. Data collection was carried out through a census of all fourth and fifth-grade students in urban elementary schools. The inclusion criterion was the consent of the students or their parents.

Instrument and data collection

The researcher visited the selected schools and distributed questionnaires among the students. Data collection was performed using a self-report questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 65 items and six sub-scales designed to measure the components of the HBM. All questions were multiple-choice with three options. The sub-scales included awareness regarding head lice infestation, which consisted of 31 items (with scores ranging from 0 to 62), perceived susceptibility and perceived severity regarding head lice infestation, each consisting of six items (with scores ranging from 0 to 12), perceived benefits of preventive behaviors against head lice infestation, which consisted of seven items (with scores ranging from 0 to 14), perceived barriers to preventive behaviors against head lice infestation, consisting of nine items (with scores ranging from 0 to 18), and perceived self-efficacy for performing preventive behaviors against head lice infestation, consisting of six items (with scores ranging from 0 to 12). To assess preventive behaviors, four multiple-choice questions were used, with scores ranging from 0 to 17. The highest score for each question was assigned to the option deemed by the researcher to represent a preventive behavior. In this research, both content and form methods were employed to establish the validity of the questionnaire, while the internal consistency method (Cronbach’s alpha) was used to assess the reliability of the questionnaire [21].

Data analysis

After the students completed the questionnaires and coding was performed, data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics, such as frequency, mean, and standard deviation, as well as the Pearson correlation coefficient. Multiple linear regression was employed to investigate the predictors of preventive behaviors using the constructs of the HBM. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16 at p<0.05.

Findings

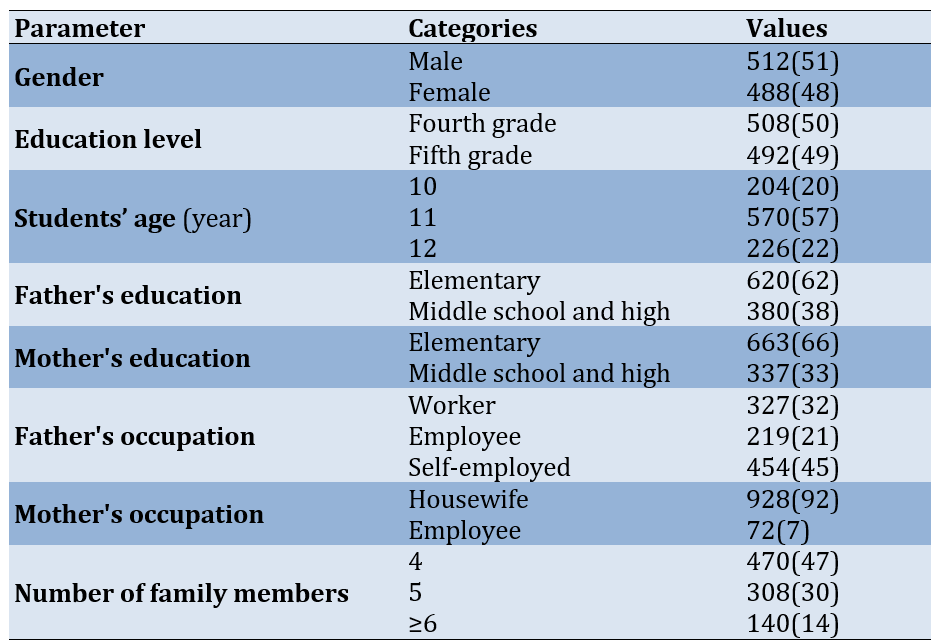

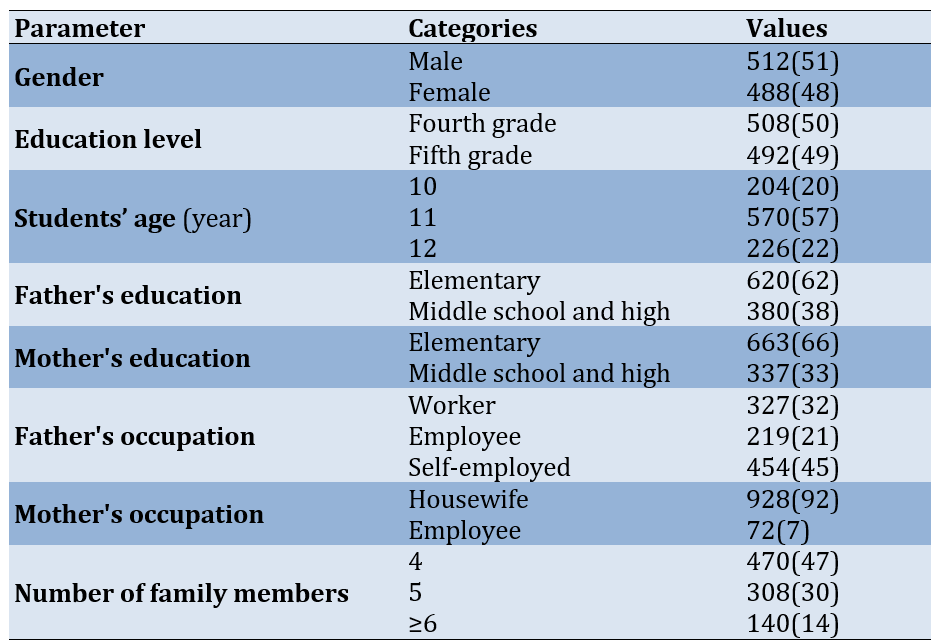

The mean age of the students included in the study was 11.02±0.55 years, ranging from a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 12 years. Regarding the occupation of their fathers, 45% were self-employed, while 92% of the mothers were housewives. In terms of education, 62% of the fathers and 66% of the mothers had elementary education. Concerning birth order, 47% of the students were fourth-born (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of study samples

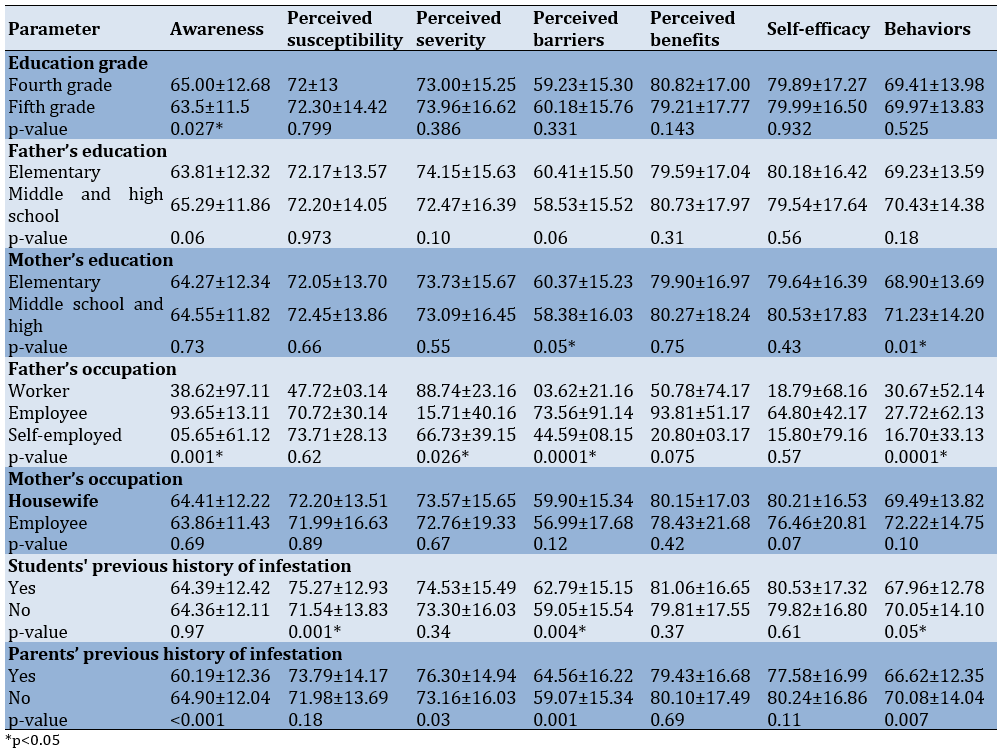

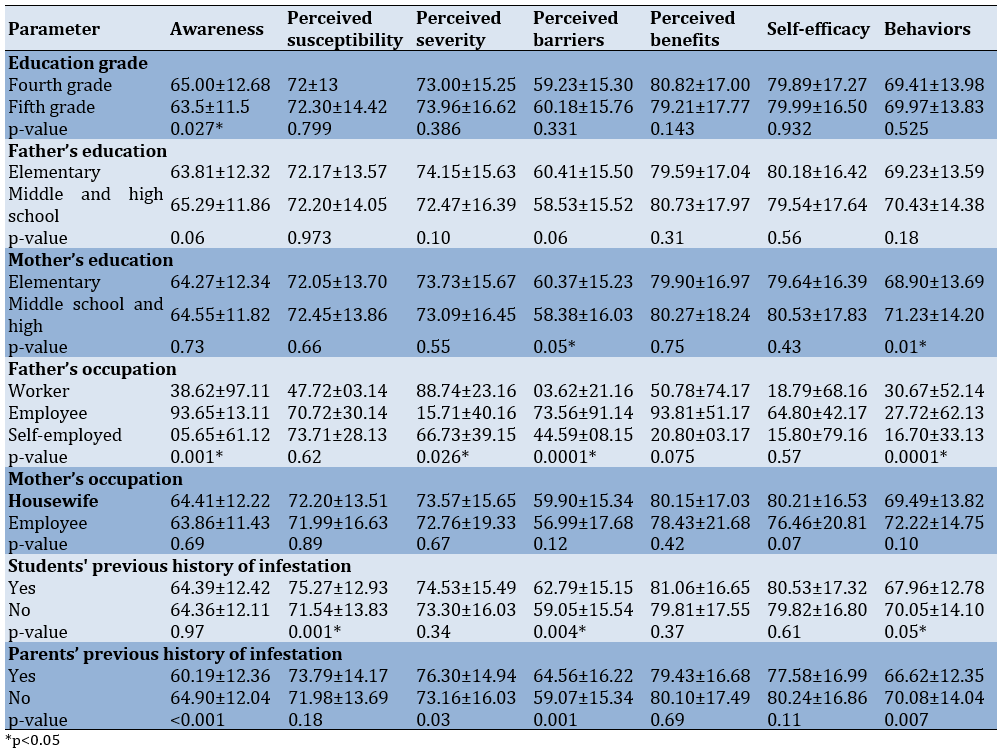

Students in the fourth grade had higher levels of awareness (p=0.027) compared to students in the fifth grade, and this difference was statistically significant. Additionally, the constructs of awareness (p=0.001), perceived severity (p=0.026), perceived barriers (p=0.0001), and behaviors (p=0.0001) were significantly associated with the father’s occupation. In other words, the level of awareness in students whose parents were employees was higher than that of those with self-employed or worker parents. Awareness (p<0.001), perceived severity (p=0.03), perceived barriers (p=0.001), and behaviors (p=0.007) were also significantly associated with the history of lice infestation in the students’ parents. This means that the history of lice infestation in students’ parents had an impact on the constructs of awareness, perceived severity, and perceived barriers in students. The constructs of perceived barriers (p=0.05) and behaviors (p=0.01) showed a significant difference based on maternal education. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the mean scores of perceived barriers (p=0.004), perceived susceptibility (p=0.001), and behaviors (p=0.05) between students with a history of lice infestation and those without a history (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of health belief model constructs' scores by demographic parameters

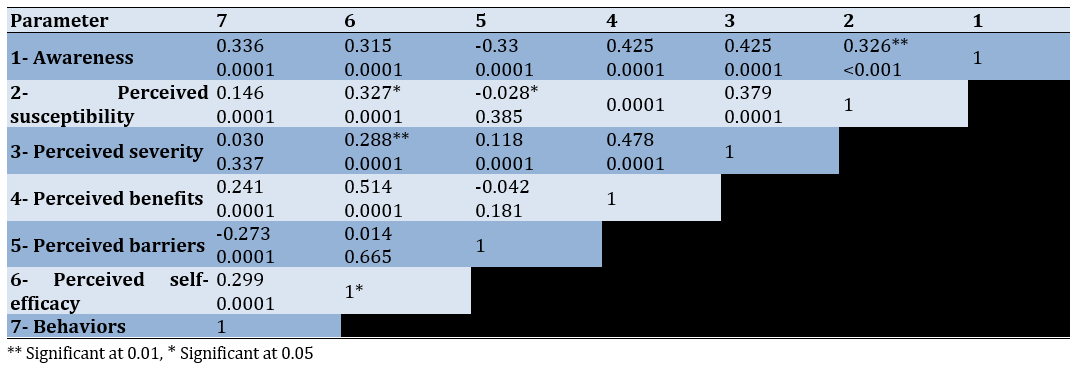

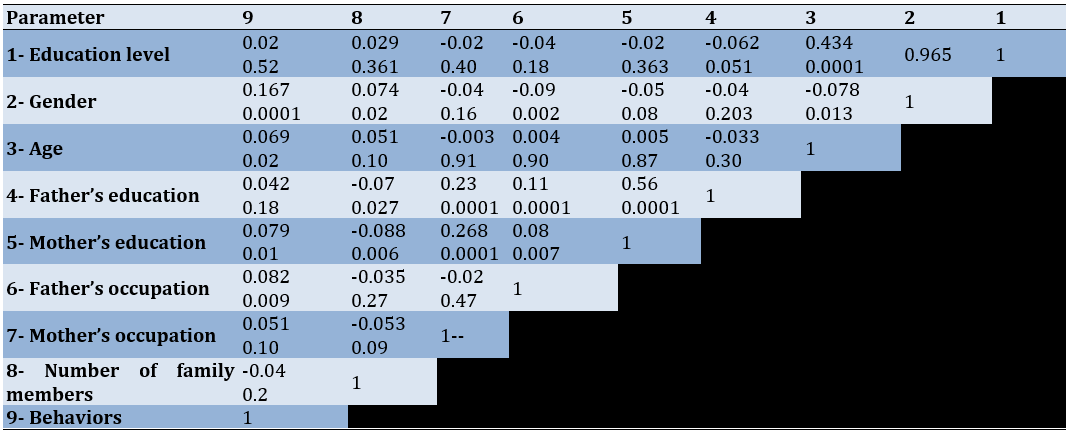

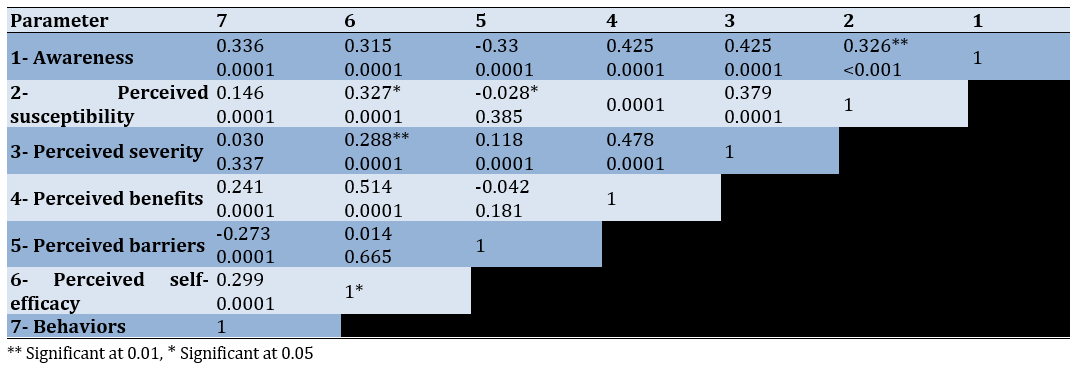

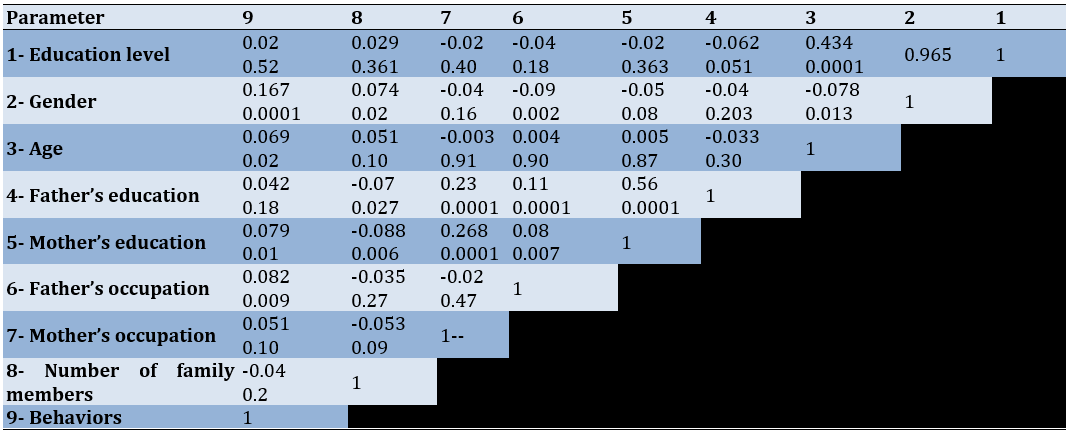

The Pearson correlation coefficient showed a significant correlation between awareness, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and preventive behaviors against pediculosis infestation. Additionally, there was a significant correlation between awareness and perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy (Table 3). Furthermore, the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a significant positive correlation between gender, age, mother’s education, and father’s occupation with preventive behaviors (Table 4).

Table 3. Correlation between components of the health belief model and preventive behaviors against pediculosis infestation in the studied students

Table 4. Correlation between demographic parameters and preventive behaviors against pediculosis in the studied students

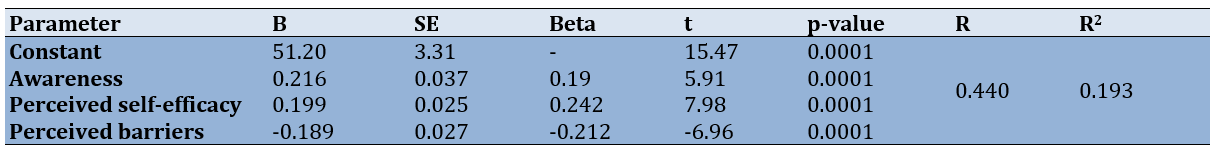

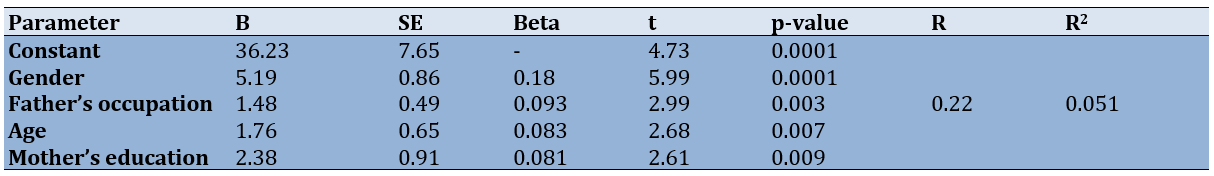

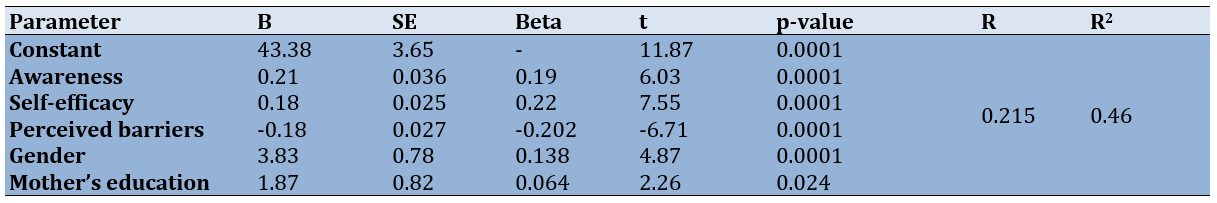

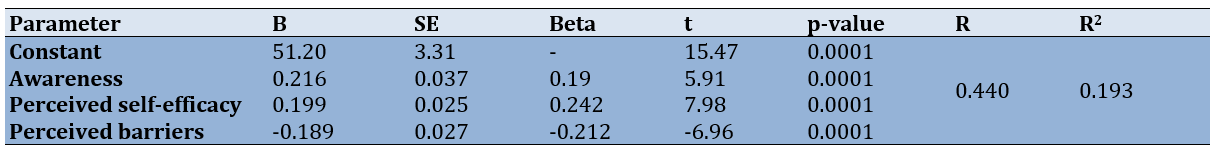

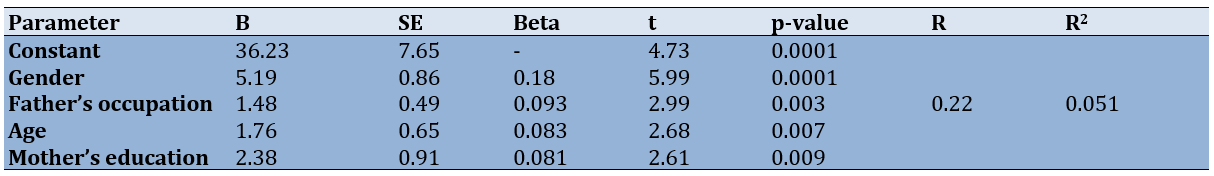

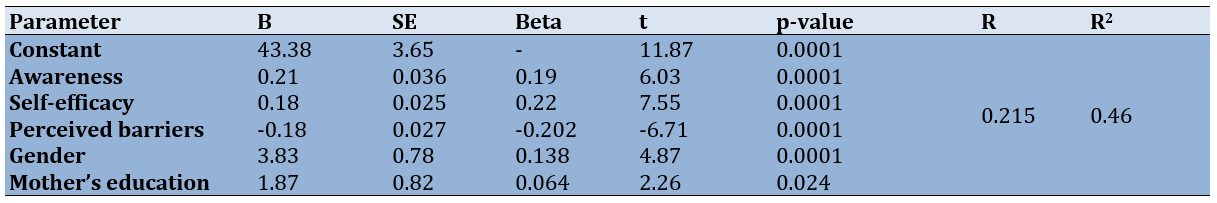

In the first phase of regression analysis, to predict behaviors using the constructs of the HBM, it was determined that among the constructs of the HBM, awareness, self-efficacy, and perceived barriers were predictors of preventive behaviors (p=0.0001). Their predictive power for behavior changes was 19.3% (R2=0.193; Table 5). In the second phase of regression analysis, to predict behaviors using demographic parameters, gender (p=0.0001), father’s occupation (p=0.003), age (p=0.007), and mother’s education (p=0.009) were identified as predictors of preventive behaviors, accounting for 5.1% (R² = 0.051) of the behavior changes (Table 6). In the final phase of regression analysis, to predict behaviors using all research parameters, it was found that the parameters of awareness (p=0.0001), self-efficacy (p=0.0001), perceived barriers (p=0.0001), gender (p=0.0001), and mother’s education (p=0.024) were determined to be the ultimate predictors of behaviors. In total, these parameters predicted only 21.5% (R²=0.215) of the behavior changes (Table 7).

Table 5. Regression model findings for predicting pediculosis preventive behaviors

Table 6. Regression model findings for predicting preventive behaviors for pediculosis by demographic parameters

Table 7. Regression model findings for ultimate predictors of preventive behaviors for pediculosis

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the determinants of preventive behaviors against pediculosis based on the HBM among 1,000 fourth- and fifth-grade elementary students in urban areas of Heris County. Given the effectiveness of the HBM in various studies, it was also employed to examine the determinants of preventive behaviors against pediculosis.

Regarding the relationship between the components of the HBM and demographic parameters, students’ awareness of pediculosis was found to be at a moderate level. This result is consistent with the findings of studies by Zareban et al. [22], Gholamnia Shirvani et al. [6], and Moshki et al. [21], which also report moderate levels of awareness among students regarding pediculosis. A study conducted by Heukelbach and Ugbomoiko in a village in Nigeria shows very low awareness about transmission and treatment methods among the study group [23]. Another study by Magalhães et al. in southeastern Angola among elementary school children revealed that 56.7% of the students had no knowledge about the treatment of pediculosis. All of these studies indicate a lack of knowledge among students in this area [24]. The results of the current study indicated that fourth-grade students had higher awareness than fifth-grade students, and there was a significant relationship between awareness, perceived severity, perceived barriers, and preventive behaviors with the father’s occupation. In other words, the level of awareness was higher in students whose parents were employees compared to those with self-employed or worker parents. These findings are consistent with the results of studies conducted by Noroozi et al. [9], Poorbaba et al. [25], Rafie et al. [26], Rafinejad et al. [27], Saghafipour et al. [8], and Soleimanizadeh & Sharifi [28].

The findings of this study also demonstrated significant correlations between all components of the HBM, except for perceived severity, and preventive behaviors against pediculosis. These results align with the findings of Baghianimoghadam et al. [29] and Mazlomi et al. [30], investigating preventive behaviors against type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the study results showed a significant correlation between perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy. This finding is consistent with the results of Vermandere et al. [31], Grace-Leitch et al. [32], and Consedine et al. [33].

The results of this study demonstrated a significant correlation between awareness and perceived severity with self-efficacy. This finding is consistent with the findings of Morowati Sharifabad et al. [34] and Moshki et al. [21] on preventive behaviors against pediculosis. Additionally, there was a significant correlation between perceived severity and perceived susceptibility, which aligns with the findings of Panahi et al. [35].

In the present study, significant correlations were observed between perceived barriers, perceived benefits, self-efficacy, and perceived severity. This corresponds to the results of Namdar et al. [36] and Didarloo et al. [37], which focused on adopting preventive behaviors against cervical cancer. Moreover, a significant correlation was found between preventive behaviors and self-efficacy, which was consistent with the findings of studies conducted by Khodaveisi et al., investigating predicting factors for adhering to infection control standard precautions among pre-hospital emergency staff [38], the study by Panahi et al. on preventive behaviors against smoking among students [35], and the study by Namdar et al. [36].

In this research, the perceived barriers of students and their behaviors showed a significant relationship with the mother’s education level, which is in line with the results of Modaresi et al. [18], Motevalli Haghi et al. [14], Noroozi et al. [9], Poorbaba et al. [25], Rafie et al. [26], Rafinejad et al. [27], and Saghafipour et al. [8], on the epidemiology of pediculosis (head lice) and its associated factors among female elementary school students in Qom Province. These findings also correspond to the results of Soleimanizadeh & Sharifi [28].

Finally, the regression analysis identified awareness, self-efficacy, perceived barriers, gender, and the mother’s education level as the ultimate predictors of preventive behaviors. This finding is consistent with the results of the study by Namdar et al., on the utility of the HBM constructs in predicting preventive behaviors against cervical cancer and introduced perceived barriers as the ultimate predictors of behaviors [36]. Additionally, it aligns with the findings of Mehri and Mohagheghnejad [39] and Mazaheri et al., on the impact of health education based on the HBM on promoting preventive behaviors against dental caries among students [40]. It also corresponds to the study by Tanner-Smith and Brown [41] in the United States, as well as Didarloo et al.'s research, on the relationship between HBM constructs and the intention to vaccinate against human papillomavirus among female students, identifying self-efficacy as the ultimate predictor of behaviors [37]. These results are also consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Poorbaba et al., on investigating preventive behaviors against pediculosis among female students in Gonabad, where perceived barriers were identified as the ultimate predictor of preventive behaviors [25].

There are several limitations to this study. First, the use of self-report questionnaires, given the young age of the fourth and fifth-grade students, may introduce errors in completing the questionnaires. Additionally, the reliance on the HBM without considering parameters outside of this theoretical framework can be regarded as another limitation of this study. Therefore, it is essential to develop appropriate educational programs based on the HBM, which can have a more substantial impact on preventive behaviors against pediculosis. Given the influential role of healthcare workers, teachers, and parents in promoting preventive behaviors against head lice infestation among students, it is recommended to design and evaluate effective interventions aimed at enhancing the health literacy of parents and school staff.

Conclusion

Awareness, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, gender, and the mother’s education level are significant ultimate predictors of preventive behaviors.

Acknowledgments: This research was derived from the MPH thesis in health education and health promotion at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. We appreciate all the authorities, teachers, students, and their parents who contributed to conducting this study.

Ethical Permissions: The researchers adhered to all ethical codes, including informed consent, confidentiality, plagiarism, double publication, data manipulation, and the generation of false data. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1397.41.).

Conflicts of Interests: All authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Shafei E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Rakhshanderou S (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Ghaffari M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Hatami H (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher 10%)

Funding/Support: This study was not financially supported by any organization.

Public health and well-being are of paramount importance in any society, as the progress of communities is closely tied to the overall health of their individuals. Among the factors that threaten community health, infestations by insects, particularly ectoparasites, remain a significant health issue despite advancements in healthcare and medical sciences, continuing to pose a health challenge [1]. Lice, specifically Anoplura (Phthiraptera), are obligate blood-sucking parasites that infest mammals, including humans. Over 550 species have been described worldwide, many of which are host-specific, targeting particular mammals [2]. Infestations of lice on the body, head, or pubic area are referred to as pediculosis [3]. Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis), body lice (Pediculus humanus corporis), and pubic lice (Phthirus pubis) are all blood-sucking ectoparasites that affect humans [4]. Among these, body lice are known to transmit diseases, such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever, while head lice are not known to be disease vectors.

In recent years, the prevalence of body lice has decreased, particularly in affluent societies, due to improved living standards. However, head lice infestations continue to be reported worldwide. Although head lice have a global distribution, they are more commonly found in temperate regions, and their annoyance and discomfort can be compared to mosquito-related problems in tropical areas. Factors, such as population growth and poor hygiene exacerbate lice infestations, with a higher prevalence observed in densely populated, impoverished communities. These infestations affect all social and economic strata during epidemics [2, 3]. The prevalence of head lice infestations in children aged 5 to 13 years is higher than in other age groups, with a greater incidence in girls than in boys. Schools, especially elementary schools, play a significant role in the occurrence of head lice epidemics [5]. Among children and women, having a dense head of hair is associated with a higher risk of lice infestation compared to other age groups [6]. The prevalence of lice infestations in elementary schools in developed countries is estimated to be between 2% and 10% [7]. Unfortunately, lice infestations in Iran have emerged as a public health issue alongside other infectious diseases in some regions due to factors such as uncontrolled population growth, rural-to-urban migration, settlement in marginalized areas, and the establishment of satellite towns with minimal sanitary facilities [8]. It is estimated that lice infestations affect between 6 to 12 million individuals worldwide annually [9-14]. Studies conducted outside of Iran have reported the prevalence of head lice infestations among elementary school students as a parameter. For example, in 2011, a study conducted among 940 students in a rural area of Yucatan, Mexico, reported a prevalence of 13.6% for head lice infestations [15]. In 2012, the prevalence of head lice infestations in Thailand was reported to be 32.23% [16]. Results from studies conducted in 2015 in the European :union: and Norway have reported head lice infestation prevalence rates of 3.44% and 1.2%, respectively [17]. The prevalence of head lice infestations in Iran varies across different regions. For instance, the prevalence of head lice infestation in female elementary school students in Qom is 6.7% [9], while in Sari County, it is 65.1% [14]. In the counties of Tonekabon and Pakdasht, and in Qom Province, the reported prevalence rates are 74.5%, 3.1%, and 3.13%, respectively [1, 9, 18]. In Kalaleh and Bonab counties, the rates are 28.6% and 82.2%, respectively [19, 20]. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2015 to determine the prevalence of head lice among Iranian elementary school students reported a prevalence of 1.6% for boys and 8.8% for girls [3]. Individuals affected by pediculosis may experience irritation, sensitivity, and fatigue due to the entry of foreign insect saliva proteins into the host’s body through insect bites. The repeated injection of louse saliva can lead to severe allergies, such as intense itching. Scratching the site of the bite can result in skin inflammation and may also lead to secondary infections, such as fungal and bacterial infections, which can cause the development of yellow ulcers and swelling of lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) around the neck and behind the ears [9]. In addition to the health issues associated with pediculosis, individuals affected by this condition may also face social difficulties, including feelings of shame and inferiority, psychological disturbances, depression, insomnia, decreased academic performance, and a loss of social status among their peers [10].

The most significant mode of transmission for infestation is through direct head-to-head contact with an infected person. Additionally, infestation can occur indirectly through contact with infested clothing, personal items (combs, towels, etc.), or bed and furniture covers infested with lice or eggs [11]. The most important prevention methods for avoiding head lice infestation include practicing personal hygiene (particularly regular bathing), refraining from sharing personal items (such as combs, brushes, and hats), promptly reporting cases of infestation to the nearest healthcare facility, using insecticidal shampoos by those affected and their family members, and educating the community in infested areas while promoting overall hygiene [12].

One of the most effective and widely used psychosocial approaches for describing health-related behaviors, which has been successfully applied to various health-related topics for nearly half a century, is the health belief model (HBM). The HBM is a psychological framework that describes and predicts health behaviors by emphasizing individuals’ attitudes and beliefs. It was developed in the 1950s by a group of social psychologists to explain the reasons behind people’s lack of participation in disease prevention or diagnosis programs [13]. Given the importance and vulnerability of elementary school-aged children, as well as the high prevalence of head lice infestations in the research area, along with the physical, psychological, social, and economic consequences associated with it, this study aimed to investigate the determinants of preventive behaviors against pediculosis in second-grade students in urban areas of Heris County, East Azerbaijan Province of Iran, using the theoretical framework of the HBM for the first time.

Instrument and Methods

Study design and sample

This descriptive-analytical correlational study was conducted on 1,000 elementary school students, both girls and boys, in urban areas of Heris County in 2019-2020. Data collection was carried out through a census of all fourth and fifth-grade students in urban elementary schools. The inclusion criterion was the consent of the students or their parents.

Instrument and data collection

The researcher visited the selected schools and distributed questionnaires among the students. Data collection was performed using a self-report questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 65 items and six sub-scales designed to measure the components of the HBM. All questions were multiple-choice with three options. The sub-scales included awareness regarding head lice infestation, which consisted of 31 items (with scores ranging from 0 to 62), perceived susceptibility and perceived severity regarding head lice infestation, each consisting of six items (with scores ranging from 0 to 12), perceived benefits of preventive behaviors against head lice infestation, which consisted of seven items (with scores ranging from 0 to 14), perceived barriers to preventive behaviors against head lice infestation, consisting of nine items (with scores ranging from 0 to 18), and perceived self-efficacy for performing preventive behaviors against head lice infestation, consisting of six items (with scores ranging from 0 to 12). To assess preventive behaviors, four multiple-choice questions were used, with scores ranging from 0 to 17. The highest score for each question was assigned to the option deemed by the researcher to represent a preventive behavior. In this research, both content and form methods were employed to establish the validity of the questionnaire, while the internal consistency method (Cronbach’s alpha) was used to assess the reliability of the questionnaire [21].

Data analysis

After the students completed the questionnaires and coding was performed, data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics, such as frequency, mean, and standard deviation, as well as the Pearson correlation coefficient. Multiple linear regression was employed to investigate the predictors of preventive behaviors using the constructs of the HBM. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16 at p<0.05.

Findings

The mean age of the students included in the study was 11.02±0.55 years, ranging from a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 12 years. Regarding the occupation of their fathers, 45% were self-employed, while 92% of the mothers were housewives. In terms of education, 62% of the fathers and 66% of the mothers had elementary education. Concerning birth order, 47% of the students were fourth-born (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of study samples

Students in the fourth grade had higher levels of awareness (p=0.027) compared to students in the fifth grade, and this difference was statistically significant. Additionally, the constructs of awareness (p=0.001), perceived severity (p=0.026), perceived barriers (p=0.0001), and behaviors (p=0.0001) were significantly associated with the father’s occupation. In other words, the level of awareness in students whose parents were employees was higher than that of those with self-employed or worker parents. Awareness (p<0.001), perceived severity (p=0.03), perceived barriers (p=0.001), and behaviors (p=0.007) were also significantly associated with the history of lice infestation in the students’ parents. This means that the history of lice infestation in students’ parents had an impact on the constructs of awareness, perceived severity, and perceived barriers in students. The constructs of perceived barriers (p=0.05) and behaviors (p=0.01) showed a significant difference based on maternal education. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the mean scores of perceived barriers (p=0.004), perceived susceptibility (p=0.001), and behaviors (p=0.05) between students with a history of lice infestation and those without a history (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of health belief model constructs' scores by demographic parameters

The Pearson correlation coefficient showed a significant correlation between awareness, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and preventive behaviors against pediculosis infestation. Additionally, there was a significant correlation between awareness and perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy (Table 3). Furthermore, the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a significant positive correlation between gender, age, mother’s education, and father’s occupation with preventive behaviors (Table 4).

Table 3. Correlation between components of the health belief model and preventive behaviors against pediculosis infestation in the studied students

Table 4. Correlation between demographic parameters and preventive behaviors against pediculosis in the studied students

In the first phase of regression analysis, to predict behaviors using the constructs of the HBM, it was determined that among the constructs of the HBM, awareness, self-efficacy, and perceived barriers were predictors of preventive behaviors (p=0.0001). Their predictive power for behavior changes was 19.3% (R2=0.193; Table 5). In the second phase of regression analysis, to predict behaviors using demographic parameters, gender (p=0.0001), father’s occupation (p=0.003), age (p=0.007), and mother’s education (p=0.009) were identified as predictors of preventive behaviors, accounting for 5.1% (R² = 0.051) of the behavior changes (Table 6). In the final phase of regression analysis, to predict behaviors using all research parameters, it was found that the parameters of awareness (p=0.0001), self-efficacy (p=0.0001), perceived barriers (p=0.0001), gender (p=0.0001), and mother’s education (p=0.024) were determined to be the ultimate predictors of behaviors. In total, these parameters predicted only 21.5% (R²=0.215) of the behavior changes (Table 7).

Table 5. Regression model findings for predicting pediculosis preventive behaviors

Table 6. Regression model findings for predicting preventive behaviors for pediculosis by demographic parameters

Table 7. Regression model findings for ultimate predictors of preventive behaviors for pediculosis

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the determinants of preventive behaviors against pediculosis based on the HBM among 1,000 fourth- and fifth-grade elementary students in urban areas of Heris County. Given the effectiveness of the HBM in various studies, it was also employed to examine the determinants of preventive behaviors against pediculosis.

Regarding the relationship between the components of the HBM and demographic parameters, students’ awareness of pediculosis was found to be at a moderate level. This result is consistent with the findings of studies by Zareban et al. [22], Gholamnia Shirvani et al. [6], and Moshki et al. [21], which also report moderate levels of awareness among students regarding pediculosis. A study conducted by Heukelbach and Ugbomoiko in a village in Nigeria shows very low awareness about transmission and treatment methods among the study group [23]. Another study by Magalhães et al. in southeastern Angola among elementary school children revealed that 56.7% of the students had no knowledge about the treatment of pediculosis. All of these studies indicate a lack of knowledge among students in this area [24]. The results of the current study indicated that fourth-grade students had higher awareness than fifth-grade students, and there was a significant relationship between awareness, perceived severity, perceived barriers, and preventive behaviors with the father’s occupation. In other words, the level of awareness was higher in students whose parents were employees compared to those with self-employed or worker parents. These findings are consistent with the results of studies conducted by Noroozi et al. [9], Poorbaba et al. [25], Rafie et al. [26], Rafinejad et al. [27], Saghafipour et al. [8], and Soleimanizadeh & Sharifi [28].

The findings of this study also demonstrated significant correlations between all components of the HBM, except for perceived severity, and preventive behaviors against pediculosis. These results align with the findings of Baghianimoghadam et al. [29] and Mazlomi et al. [30], investigating preventive behaviors against type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the study results showed a significant correlation between perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy. This finding is consistent with the results of Vermandere et al. [31], Grace-Leitch et al. [32], and Consedine et al. [33].

The results of this study demonstrated a significant correlation between awareness and perceived severity with self-efficacy. This finding is consistent with the findings of Morowati Sharifabad et al. [34] and Moshki et al. [21] on preventive behaviors against pediculosis. Additionally, there was a significant correlation between perceived severity and perceived susceptibility, which aligns with the findings of Panahi et al. [35].

In the present study, significant correlations were observed between perceived barriers, perceived benefits, self-efficacy, and perceived severity. This corresponds to the results of Namdar et al. [36] and Didarloo et al. [37], which focused on adopting preventive behaviors against cervical cancer. Moreover, a significant correlation was found between preventive behaviors and self-efficacy, which was consistent with the findings of studies conducted by Khodaveisi et al., investigating predicting factors for adhering to infection control standard precautions among pre-hospital emergency staff [38], the study by Panahi et al. on preventive behaviors against smoking among students [35], and the study by Namdar et al. [36].

In this research, the perceived barriers of students and their behaviors showed a significant relationship with the mother’s education level, which is in line with the results of Modaresi et al. [18], Motevalli Haghi et al. [14], Noroozi et al. [9], Poorbaba et al. [25], Rafie et al. [26], Rafinejad et al. [27], and Saghafipour et al. [8], on the epidemiology of pediculosis (head lice) and its associated factors among female elementary school students in Qom Province. These findings also correspond to the results of Soleimanizadeh & Sharifi [28].

Finally, the regression analysis identified awareness, self-efficacy, perceived barriers, gender, and the mother’s education level as the ultimate predictors of preventive behaviors. This finding is consistent with the results of the study by Namdar et al., on the utility of the HBM constructs in predicting preventive behaviors against cervical cancer and introduced perceived barriers as the ultimate predictors of behaviors [36]. Additionally, it aligns with the findings of Mehri and Mohagheghnejad [39] and Mazaheri et al., on the impact of health education based on the HBM on promoting preventive behaviors against dental caries among students [40]. It also corresponds to the study by Tanner-Smith and Brown [41] in the United States, as well as Didarloo et al.'s research, on the relationship between HBM constructs and the intention to vaccinate against human papillomavirus among female students, identifying self-efficacy as the ultimate predictor of behaviors [37]. These results are also consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Poorbaba et al., on investigating preventive behaviors against pediculosis among female students in Gonabad, where perceived barriers were identified as the ultimate predictor of preventive behaviors [25].

There are several limitations to this study. First, the use of self-report questionnaires, given the young age of the fourth and fifth-grade students, may introduce errors in completing the questionnaires. Additionally, the reliance on the HBM without considering parameters outside of this theoretical framework can be regarded as another limitation of this study. Therefore, it is essential to develop appropriate educational programs based on the HBM, which can have a more substantial impact on preventive behaviors against pediculosis. Given the influential role of healthcare workers, teachers, and parents in promoting preventive behaviors against head lice infestation among students, it is recommended to design and evaluate effective interventions aimed at enhancing the health literacy of parents and school staff.

Conclusion

Awareness, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, gender, and the mother’s education level are significant ultimate predictors of preventive behaviors.

Acknowledgments: This research was derived from the MPH thesis in health education and health promotion at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. We appreciate all the authorities, teachers, students, and their parents who contributed to conducting this study.

Ethical Permissions: The researchers adhered to all ethical codes, including informed consent, confidentiality, plagiarism, double publication, data manipulation, and the generation of false data. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1397.41.).

Conflicts of Interests: All authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Shafei E (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Rakhshanderou S (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Ghaffari M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Hatami H (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher 10%)

Funding/Support: This study was not financially supported by any organization.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2024/02/15 | Accepted: 2024/11/17 | Published: 2024/11/20

Received: 2024/02/15 | Accepted: 2024/11/17 | Published: 2024/11/20

References

1. Davari B, Kolivand M, Poormohammadi A, Faramarzi Gohar A, Faizei F, Rafat Bakhsh S, et al. An epidemiological study of Pediculus capitis in students of Pakdasht County, in autumn of 2013. PAJOUHAN Sci J. 2015;14(1):57-63. [Persian] [Link]

2. Bonilla DL, Durden LA, Eremeeva ME, Dasch GA. The biology and taxonomy of head and body lice-implications for louse-borne disease prevention. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(11):e1003724. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003724]

3. Moosazadeh M, Afshari M, Keianian H, Nezammahalleh A, Enayati AA. Prevalence of head lice infestation and its associated factors among primary school students in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015;6(6):346-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.phrp.2015.10.011]

4. Motalebi M, Minoueian Haghighi MH. The survey of pediculosis prevalence on Gonabad primary school students. Intern Med Today. 2000;6(1):80-7. [Persian] [Link]

5. Motovali-Emami M, Aflatoonian MR, Fekri A, Yazdi M. Epidemiological aspects of pediculosis capitis and treatment evaluation in primary schoolchildren in Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11(2):260-4. [Link] [DOI:10.3923/pjbs.2008.260.264]

6. Gholamnia Shirvani Z, Amin Shokravi F, Ardestani MS. Effect of designed health education program on knowledge, attitude, practice and the rate of pediculosis capitis in female primary school students in Chabahar city. J Sharekord Univ Med Sci. 2011;13(3):25-35. [Persian] [Link]

7. Muller R, Haker J. An epidemic of pediculosis capitis. J Med Parasitol. 1999;128-30. [Link]

8. Saghafipour A, Akbari A, Norouzi M, Khajat P, Jafari T, Tabaraei Y, et al. The epidemiology of pediculus is humanus capitis infestation and effective factors in elementary schools of Qom province girls 2010, Qom, Iran. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2012;6(3):46-51. [Persian] [Link]

9. Noroozi M, Saghafipour A, Akbari A, Khajat P, Khadem Maboodi A. The prevalence of pediculosis capitis and its associated risk factors in primary schools of girls in rural district. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2013;15(2):43-52. [Persian] [Link]

10. Service MW. A guide to medical entomology. Zaim M, Seyedi Rashti MA, Saebi ME, translators. Tehran: University of Tehran; 2004. [Persian] [Link]

11. Nenoff P, Handrick W. Pediculosis capitis. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156(14):49-51. [German] [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s15006-014-3342-x]

12. Simmons S. Taking a closer look at pediculosis capitis. Nursing. 2015;45(6):57-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000464986.00187.3a]

13. Butler JT. Principle of health education and promotion. Belmont: Wadsworth; 2001. [Link]

14. Motevalli Haghi SF, Rafinejad J, Hosseni M. Epidemiology of pediculosis and its associated risk factors in primary-school children of Sari, Mazandaran province, in 2012-2013. J Health. 2014;4(4):339-48. [Persian] [Link]

15. Manrique-Saide P, Pavía-Ruz N, Rodríguez-Buenfil JC, Herrera Herrera R, Gómez-Ruiz P, Pilger D. Prevalence of pediculosis capitis in children from a rural school in Yucatan, Mexico. REVISTA DO INSTITUTO DE MEDICINA TROPICAL DE SÃO PAULO. 2011;53(6):325-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0036-46652011000600005]

16. Rassami W, Soonwera M. Epidemiology of pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in the eastern area of Bangkok, Thailand. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(11):901-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60250-0]

17. Bartosik K, Buczek A, Zajac Z, Kulisz J. Head pediculosis in schoolchildren in the eastern region of the European :union:. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22(4):599-603. [Link] [DOI:10.5604/12321966.1185760]

18. Modaresi M, Mansouri Ghiasi MAN, Modaresi M, Marefat A. Prevalence of head lice infection among primary school students in Tonekabon. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2013;18(60):41-5. [Persian] [Link]

19. Noori A, Ghorban Pour M, Adib M, Noori AV, Niazi S. Head lice infestation (pediculosis) and its associated factors in the rural school students of Kalaleh, in the academic year 1392-93. JORJANI Biomed J. 2014;2(1):56-60. [Persian] [Link]

20. Kabiri H, Dastgiri S, Alizadeh M. The prevalence of head lice (pediculus humanus capitis) and its associated risk factors in Bonab county during 2013-2014. Depiction Health. 2015;6(1):31-6. [Persian] [Link]

21. Moshki M, Mojadam M, Zamani Alavijeh F. Preventive behaviors of female elementary students in regard to pediculosis infestation based on Health Belief Model (HBM). Health Dev J. 2014;3(3):269-81. [Persian] [Link]

22. Zareban I, Abbaszadeh M, Moodi M, Mehrjoo Fard H, Ghaffari H. Evaluation a health education program in order to reduce infection to pediculus humanus capitis among female elementary students. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2006;13(1):9-15. [Persian] [Link]

23. Heukelbach J, Ugbomoiko US. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding head lice infestations in rural Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5(9):652-7. [Link] [DOI:10.3855/jidc.1746]

24. Magalhães P, Figueiredo EV, Capingana DP. Head lice among primary school children in Viana, Angola: Prevalence and relevant teachers' knowledge. Hum Parasit Dis. 2011;3:11-8. [Link] [DOI:10.4137/HPD.S6970]

25. Poorbaba R, Moshkbid-Haghighi M, Habibipoor R, Mirza Nezhad M. A survey of prevalence of pediculosis among primary school students of Guilan province in the school year of 2002-3. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2005;13(52):15-24. [Persian] [Link]

26. Rafie A, Kasiri H, Mohammadi Z, Haqiqi Zadeh MH. Pediculosis capitis and its associated factors in girl primary school children in Ahvaz City in 2005-2006. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2009;14(45):41-5. [Persian] [Link]

27. Rafinejad J, Noorollahi A, Javadian A, Kazemnejad A, Shemshad KH. Epidemiology of head louse infestation and related factors in school children in the county of Amlash, Gilan Province, 2003-2004. Iran J Epidemiol. 2006;2(3-4):51-63. [Persian] [Link]

28. Soleimanizadeh L, Sharifi KH. Study of effective factors on prevalence of head lice in primary school students of Bandar Abbas (1999). Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2002;7(19):79-85. [Persian] [Link]

29. Baghianimoghadam MH, Mirzaei M, Rahimdel T. Role of health beliefs in preventive behaviors of individuals at risk of cardiovascular diseases. J Health Syst Res. 2012;8(7):1151-8. [Persian] [Link]

30. Mazlomi SS, Mirzaii A, Afkhami Ardakani M, Baghiani Moghadam MH, Falahzadeh H. The role of health beliefs in preventive behaviors in people with type 2 diabetes at risk. J SHAHEED SADOUGHI Univ Med Sci. 2010;18(1):24-31. [Persian] [Link]

31. Vermandere H, Van Stam MA, Naanyu V, Michielsen K, Degomme O, Oort F. Uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine in Kenya: Testing the health belief model through pathway modeling on cohort data. Glob Health. 2016;12(1):72. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12992-016-0211-7]

32. Grace-Leitch L, Shneyderman Y. Using the health belief model to examine the link between HPV knowledge and self-efficacy for preventive behaviors of male students at a two-year college in New York City. Behav Med. 2016;42(3):205-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08964289.2015.1121131]

33. Consedine NS, Magai C, Horton D, Neugut AI, Gillespie M. Health belief model factors in mammography screening: Testing for interactions among subpopulations of Caribbean women. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(3):444-52. [Link]

34. Morowati Sharifabad MA, Ebrahim Zadeh M, Fazeli F, Dehghani A, Neshati T. Study of pediculus capitis prevalence in primary school children and its preventive behaviors determinants based on Health Belief Model in their mothers in Hashtgerd, 2012. TOLOO-E-BEHDASHT. 2016;14(6):198-207. [Persian] [Link]

35. Panahi R, Ramezankhani A, Tavousi M, Osmani F, Niknami S. Predictors of adoption of smoking preventive behaviors among university students: Application of Health Belief Model. J Educ Community Health. 2017;4(1):35-42. [Persian] [Link]

36. Namdar A, Bigizadeh S, Naghizadeh MM. Measuring Health Belief Model components in adopting preventive behaviors of cervical cancer. J Adv Biomed Sci. 2012;2(1):34-44. [Persian] [Link]

37. Didarloo AR, Pourali R, Sorkhabi Z, Sharafkhani N. Survey of prostate cancer-preventive behaviors based on the Health Belief Model constructs among male teachers of Urmia city, in 2015. Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;14(3):271-81. [Persian] [Link]

38. Khodaveisi M, Mohamadkhani M, Amini R, Karami M. Factors predicting the standard precautions for infection control among pre-hospital emergency staff of Hamadan based on the Health Belief Model. J Educ Community Health. 2017;4(3):12-8. [Persian] [Link]

39. Mehri A, Mohagheghnejad MA. Utilizing the Health Belief Model to predict preventive behaviors heart diseases in the students of Islamic Azad University of Sabzevar. TOLOO-E-BEHDASHT. 2011;9(2):21. [Persian] [Link]

40. Mazaheri M, Eamazankhani A, Dehdari T. The effect of health education based on health belief model (HBM) for promoting preventive behavior of tooth decay among the boy students, who are in five-grade in the primary school. PAYESH. 2012;11(4):497-503. [Persian] [Link]

41. Tanner-Smith EE, Brown TN. Evaluating the health belief model: A critical review of studies predicting mammographic and pap screening. Soc Theory Health. 2010;8(1):95-125. [Link] [DOI:10.1057/sth.2009.23]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |