Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 105-110 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Markova G. The Health Culture of Adolescents from Pleven, Bulgaria. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :105-110

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72771-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72771-en.html

Department of Nursing Surgical Care, Faculty of Health Care, Medical University of Pleven, Pleven, Bulgaria

Full-Text [PDF 606 kb]

(2935 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1252 Views)

Full-Text: (118 Views)

Introduction

Today, we live in a dynamic world where health often does not take priority until we face serious health problems, some of which lead to permanent disabilities and reduced life expectancy. Many of these issues are preventable, simply requiring the population to develop a subjective health culture based on knowledge, beliefs, motivation, acquired habits, and behavioral patterns.

Behavioral health-risk factors such as the use of alcohol and narcotic substances, smoking, and the consumption of high-calorie food combined with physical inactivity are observed among adolescents in the European :union: [1-6]. In some respects, Bulgaria shows even worse outcomes [7]. According to a report by the Regional European Office of the World Health Organization, Bulgarian children aged 11-13 rank highly in terms of alcohol use and abuse, tobacco products, and cannabis use [8]. The situation is similar to the consumption of fast food in combination with physical inactivity [9, 10].

It is critical to recognize that health-risk behaviors are the most common sources of morbidity among adolescents [11]. Muñoz-Pindado et al. note that the presence of one behavioral health risk factor often leads to others, recommending the creation of preventive programs targeting this age group [12].

Research teams such as Dyachuk et al. and Khan et al. also advocate for the introduction of measures to correct behavioral risk factors [13, 14]. In some countries, systematic observations and health education programs are conducted among junior high school students [15-20].

Garov highlights that the level of health knowledge directly impacts an individual's health status [21].

Significant correlations have been found between health knowledge and adolescent health behavior [22]. It is important to note that individuals with lower health literacy are more likely to trust dubious sources of health information, posing additional health risks [23]. Supporting this, Timoshilov & Lastovetckii have shown that independent searching for drug information on the Internet can have detrimental effects, suggesting that widespread implementation of targeted advanced training is necessary [4].

According to Kolmaga et al. health education should be compulsory in school [24]. Perelman et al. prove that the school as an institution and environment plays an important role in preventing smoking among adolescents [25]. I would also add in the prevention of the use of alcohol and narcotic substances, the prevention of unhealthy eating habits, and the fight against hypo- and adynamia. For this purpose, complex health and educational activities with a preventive purpose must be undertaken among the students.

Within Bulgaria, Slavchev recommends harnessing the efforts of the entire society and all institutions, including schools [26]. A decade earlier, Terzieva established the same need to develop and create a health education and educational program in order to master the growing knowledge about health, its protection, and preservation [27].

This study aimed to assess the level of knowledge and attitudes of teenagers towards certain health risk factors (tobacco smoking, use of narcotic substances, alcohol consumption, eating fatty and caloric foods, and lack of physical activity) to determine the need for more in-depth health education among them.

Materials and Methods

In February 2023, a survey was conducted through direct group interviews among 71 children aged 11-13, in two primary schools in the municipality of Pleven, Bulgaria. The participants were students from three different fifth-grade classes in two primary schools in the city of Pleven. The schools and classes were randomly selected. All students studying in the designated grades were included in the survey. The children were interviewed after obtaining written informed consent from their parents. An original questionnaire containing 29 logically connected questions, adapted to the children's age, was used. The questionnaire format included 4 introductory questions, 2 filter questions, 21 main questions, and 2 open-ended questions. The main questions were directly related to the survey topic. Of all the questions: 24 were closed-ended; 12 allowed for more than one answer; 3 were semi-closed (allowing for more than one answer or an additional opinion). The two open-ended questions were designed to gather detailed responses. In six of the closed-ended questions, a three-point scale was used with options "yes," "no," and "I don’t know," and in 5 questions a binary "yes" or "no" option was provided. This questionnaire enables the investigation of the teenagers' knowledge levels and attitudes towards the issues at hand.

Survey data were processed using SPSS Statistics 25 and Excel for Windows statistical software packages. The results are presented through graphs and numerical indicators such as structure, frequency, averages, correlation coefficients, and others. Both the χ2 and Fisher's exact test criteria were applied.

Findings

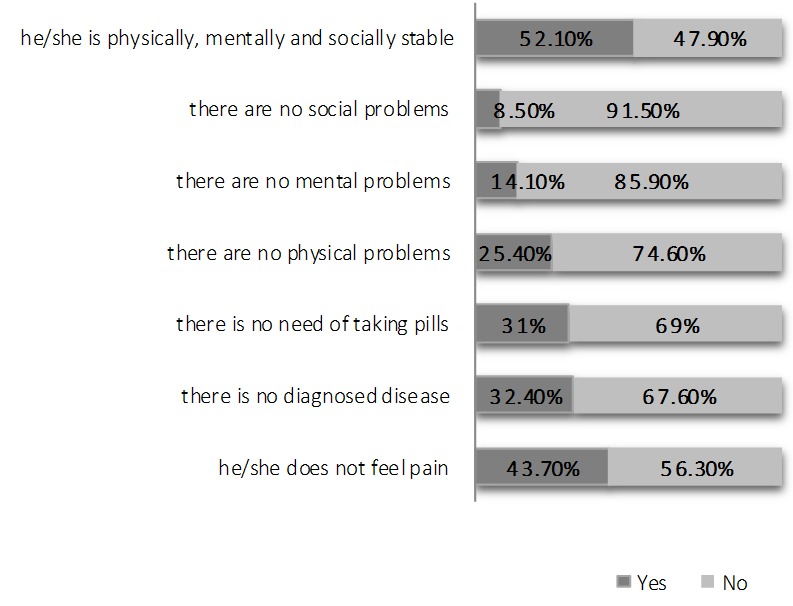

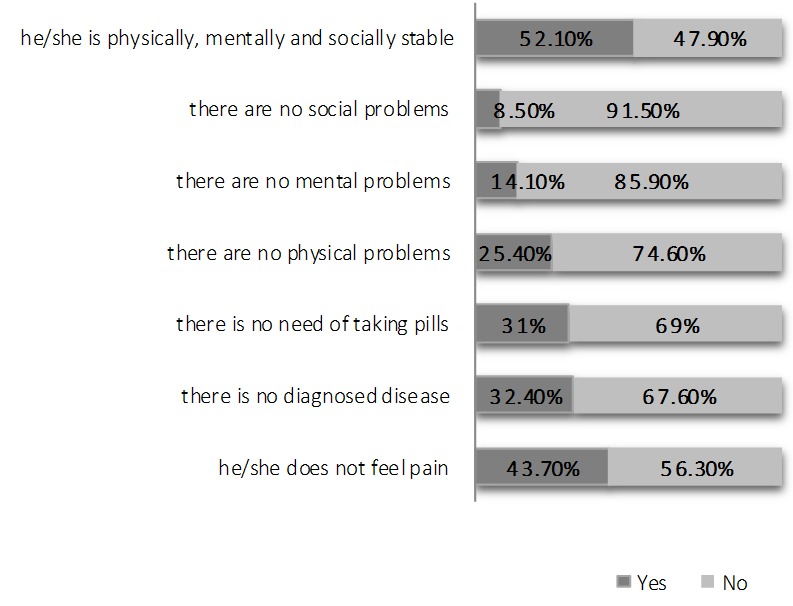

Seventy-one children aged 11-13 from two primary schools in the city of Pleven participated in the study. The majority were 11-year-olds, making up 78.9% (n=71), followed by 12-year-olds at 16.9% (n=71). Regarding gender distribution, boys represent 50.7% (n=36) and girls 49.3% (n=35). A significant proportion, 77.5% (n=55), reported having older children in their circle of friends. According to 97.2% (n=69) of the children, health is valued. Nearly 44% (n=31) of the children believe that a person is healthy when they experience no pain and 32.4% (n=23) associate health with the absence of a diagnosed disease. Meanwhile, 52.10% (n=37) define health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being (Figure 1). The results indicate that the choice of wording for "healthy person" is not based on knowledge and understanding, but appears to be random (df=1, χ2=1.891, p=0.1, r=0.16).

Figure 1. Characteristics of a healthy person.

According to 95.8% (n=68) of the surveyed adolescents, a person’s health depends solely on their lifestyle. Only 4.2% (n=3) believe that health also depends on the individual’s age and gender.

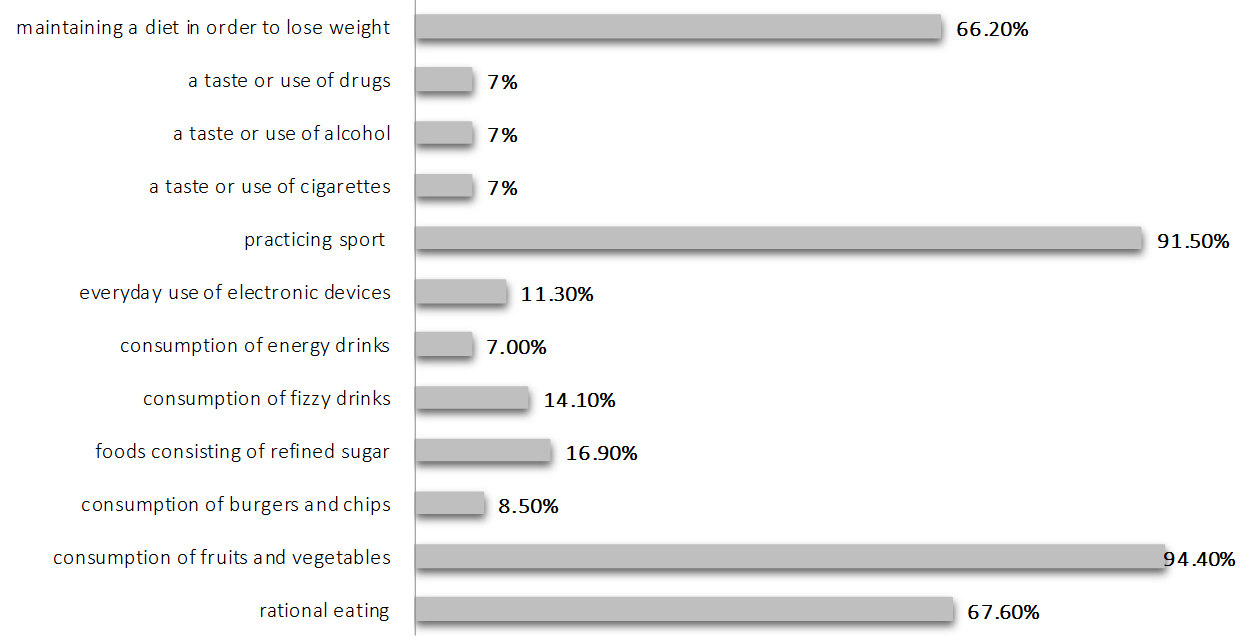

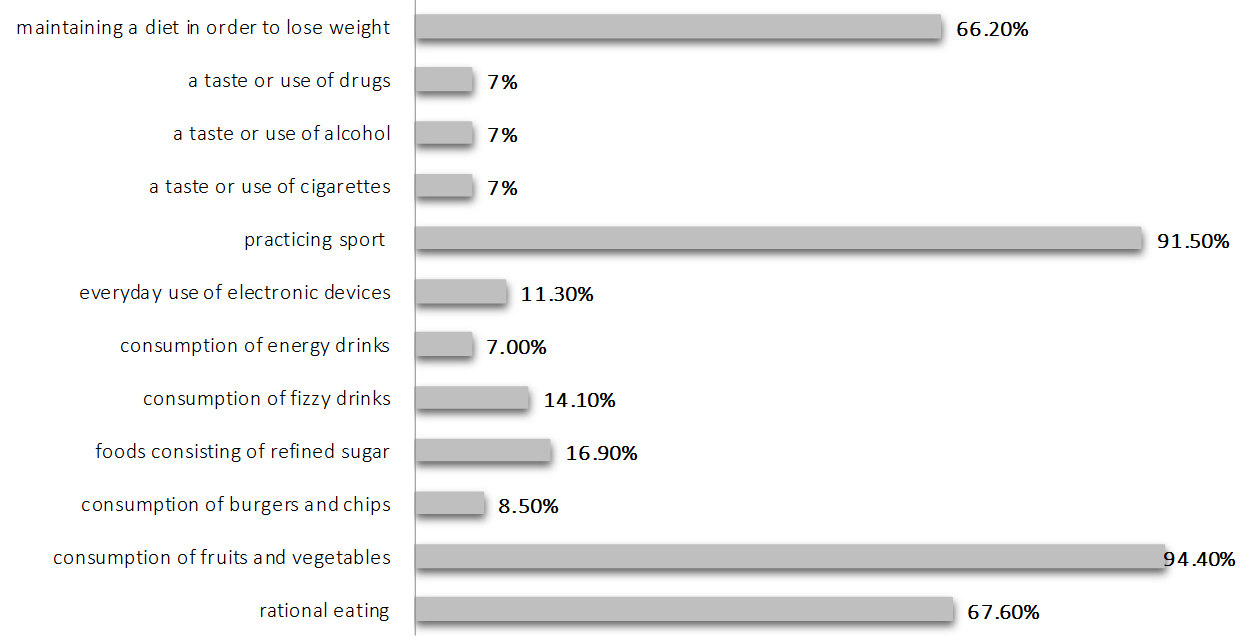

The children were asked to identify actions they consider non-hazardous to their health. Impressively, the children were well-informed about three health-related factors: exercise, fruit and vegetable consumption, and rational nutrition. However, it is concerning that more than half (66.2%; n=47) considered dieting to reduce body mass as safe. Additionally, a smaller but notable proportion believed it is safe to consume foods containing refined sugar, carbonated drinks, burgers and chips, and use electronic devices. There were also children who thought the use of tobacco products, alcohol, cigarettes, and drugs was safe (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Characteristics of a safe diet for health.

Nearly 41% of children (29) admitted that they wanted to try at least one of the following: alcohol, cigarettes, smokeless cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, or marijuana. When asked "What would provoke them to try these?", 28.2% (20) answered curiosity, and 12.7% (9) would do it because it is considered fashionable. A stronger motive influencing teenagers was the trendiness (df=1, χ2=14.867, p=0.001, r=0.456), with curiosity having a slightly weaker influence (df=1, χ2=10.200, p<0.05, r=0.38). Age (df=2, χ2=0.91, p=0.1, r=0.1) and gender (df=2, χ2=0.91, p=0.1, r=0.1) of the children had no significant effect. More than half of the children (69%; n=49) believed that trying drugs could endanger their health. However, it is concerning that some still think it is not dangerous (12.7%; n=9), and others are unaware of the consequences (18.3%; n=13).

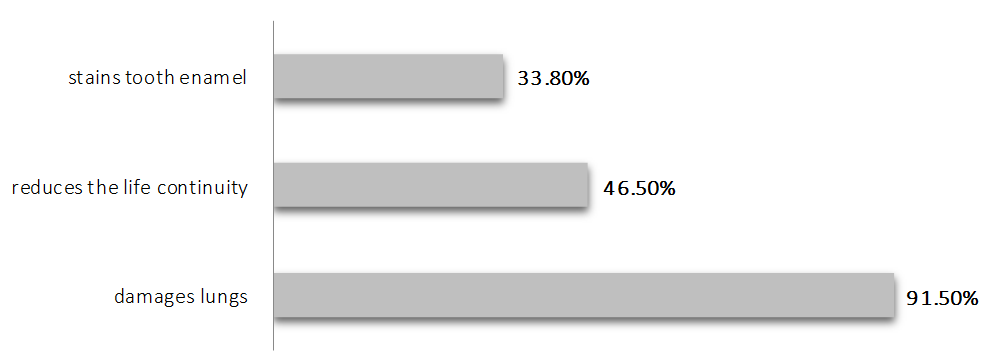

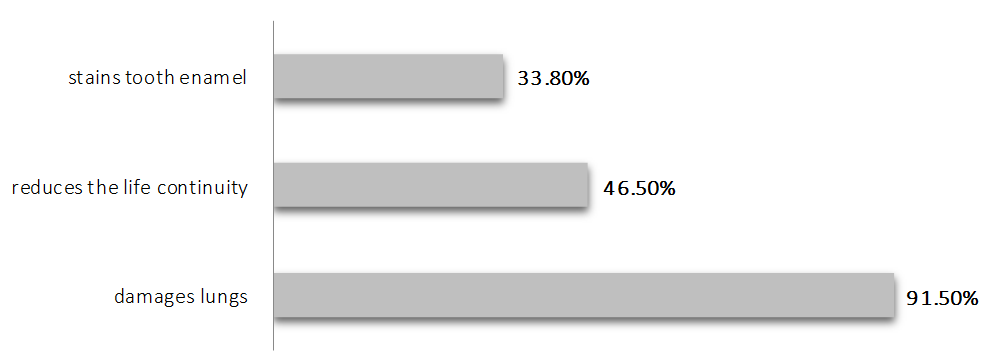

A significant proportion of the respondents (54.9%; n=39) believed that using drugs can help one forget their problems. Unfortunately, the effects are diverse and often have severe consequences, which the results indicated the children were not fully aware of. It is alarming that 29.6% (21) said there are children in their circle of friends who use drugs. Only 14.1% (10) acknowledged being offered a narcotic substance. There was a moderate correlation between knowing someone who uses drugs and being offered drugs themselves (df=2, χ2=7.446, p=0.025, r=0.31). The presence of older children in their circle of friends did not significantly influence whether the surveyed children were offered drugs (df=3, χ2=2.977, p=0.1, r=0.1) nor their desire to try them (df=3, χ2=0.263, p=0.1, r=0.134). However, it is a reason why some teenagers want to try smoking (df=3, χ2=16.823, p=0.001, r=0.328). Almost half of them (46.5%; n=33) claimed that there are children who smoke in their circle of friends. Although they were aware of the harmful effects of tobacco use (Figure 3), 44.8% (32) have tried one or more of the following: a cigarette, electronic cigarette, hookah, or smokeless cigarette. In this case, no cause-and-effect relationship was observed between knowledge and behavior in teenagers (df=1, χ2=0.34, p=0.1, r=0.06). Boys and girls are equally exposed to this behavioral risk factor (df=1, χ2=1.015, p=0.1, r=0.1).

Figure 3. Effects of cigarettes on health state according to students.

Regarding alcohol, 90.1% (64) of teenagers firmly stated that it is harmful to their health. A significant proportion, 76.1% (n=54), were convinced that their peers have tried alcohol, and 59.2% (42) claim to know such individuals personally. Additionally, a considerable number, 47.9% (n=34), admitted they have tried alcohol themselves. However, there was neither a regular difference between boys and girls (df=1, χ2=2.471, p=0.1, r=0.19) nor a causal relationship between "awareness and behavior" (df=2, χ2=4.138, p=0.1, r=0.1).

The surveyed students strongly believed that to be healthy, one must engage in sports (85.9%; n=61). Yet, nearly 30% (20) preferred to play electronic games in their free time, and 18.3% (13) opted to watch TV. Boys were significantly more likely to prefer electronic games (df=1, χ2=10.08, p=0.001, r=0.38). Watching television showed no significant differences based on the gender of the children (df=2, χ2=4.52, p=0.1, r=0.1).

A vast majority of teenagers (91.5%; n=65) recognized that a varied diet is important for maintaining health. More than half (57.75%; n=34) preferred to consume cooked meals, fruits, and vegetables, though their preferences were slightly influenced by their knowledge of varied nutrition (df=1, χ2=5.085, p=0.025, r=0.27). However, there was a group of children (37.8%; n=27) who found it appropriate to consume burgers, chips, waffles, biscuits, and chocolate. Their dietary choices were not significantly influenced by their nutritional knowledge (df=1, χ2=0.139, p=0.1, r=0.04).

Discussion

Health is universally valued, yet in our busy daily lives, we often neglect it. Children also define health as a value, but what is interesting is their interpretation of what constitutes a "healthy person," as shown in Figure 1. Unfortunately, the results indicate that they are not aware of the full content of the concept, and their explanations reflect this misunderstanding. This trend, however, is not limited to the children surveyed but is observed across our entire society. For many people, the absence of pain or infirmity is mistakenly interpreted as a state of good health.

It is particularly concerning that the results of this study reaffirm that the 11-13 age group is especially vulnerable to behavioral health risk factors. Some adolescents in this age group have peers who have experimented with drugs, tobacco products, and alcohol; others have been offered narcotics; a third group, despite some awareness, engages in health-risk behaviors like using tobacco and alcohol at a tender age. The likely reasons for the use of alcohol and tobacco products are their widespread availability and social acceptance. The influence of the family environment as a contributing factor should not be overlooked.

In Bulgaria, smoking and alcohol consumption among both adults and adolescents represent significant public health challenges. Our country ranks among the top in the European :union: for these two behavioral health risk factors [28]. Although the use of tobacco products and alcohol may not be perceived by society as a direct threat to health, this risky behavior should not be ignored, especially in children. It has been shown that teenagers who exhibit even one behavioral risk factor are highly likely to develop additional risk behaviors [29]. This is a critical issue that should not be overlooked due to its potential domino effect on both personal and public health.

The results showing children's knowledge of health risk factors are concerning. This is not entirely surprising, given the limited hours devoted to health education in schools, which mainly focus on healthy eating. The training that occurs is integrated into the general education curriculum. There is no dedicated general education subject specifically focused on health-relevant knowledge and the development of skills for health-protective behavior. Despite long-standing evidence-based recommendations for implementing health education in schools effectively, it is clear that such measures are not being adequately implemented, and the negative impacts are apparent. The minimal knowledge demonstrated by students, and some even displaying health-risk behaviors, indicates that the traditional methods of delivering health-promotional information are ineffective. The formal presentation of health and education topics within various curricula does not yield positive results. Theoretical training alone is insufficient. Protective health behavior is not being instilled in children. There is a lack of engagement and stimulation to preserve one's own health and that of others, and responsibility for health is not being developed. The facts reported are unable to sufficiently interest young people, failing to help them understand the problems and ignite a desire to be part of the solution.

Although health education is regulated among adolescents in Bulgaria, studies show that it is not sufficiently developed, does not reach all students, and is limited to a few locations [30, 31]. Georgieva & Kamburova have noted that "over 80% of health education activities use traditional and unattractive methods or do not meet the informational needs of students, who are treated as a passive audience in this process." They suggest that school health education should be tailored to the needs and interests of the students [32]. Boncheva & Dokova surveyed students who described their knowledge of health issues received in secondary school as incomplete or absent [33]. This gap in education is a major factor contributing to the negative trends in the health status and behaviors of Bulgarian children. According to Borisova & Mihaylov, students are positively inclined toward having a health education subject in school and are motivated to learn about health topics and participate in activities that enhance their health culture, showing a preference for non-formal education and interactive methods [31]. Hizhov & Prokopov have developed a model for a health education program aimed at junior high school students, but the effects of its implementation have not yet been detailed [34].

Childhood and adolescence are critical periods during which children shape their character and behavior. This is when they are most receptive to adopting new patterns of behavior. It is essential to use this time to impart health knowledge and build a solid health culture.

Given the findings about the risky behaviors of Bulgarian adolescents and their level of health culture from both the literature review and this study, the implementation of mandatory health and educational measures for adolescents in our country is extremely urgent.

Conclusion

Children possess only superficial knowledge about health and its various aspects. They are somewhat familiar with some of the factors that influence health. Regarding behavioral risk factors, their knowledge is insufficient to serve as a basis for making sound health decisions. The level of health culture among adolescents is unsatisfactory.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all those who responded to the survey.

Ethical Permissions: The questionnaires used were originally developed for the aims of the study and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Medical University-Pleven, Bulgaria.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interest were reported.

Authors’ Contribution: Markova G (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (100%)

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Program ‘Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Students-2’.

Today, we live in a dynamic world where health often does not take priority until we face serious health problems, some of which lead to permanent disabilities and reduced life expectancy. Many of these issues are preventable, simply requiring the population to develop a subjective health culture based on knowledge, beliefs, motivation, acquired habits, and behavioral patterns.

Behavioral health-risk factors such as the use of alcohol and narcotic substances, smoking, and the consumption of high-calorie food combined with physical inactivity are observed among adolescents in the European :union: [1-6]. In some respects, Bulgaria shows even worse outcomes [7]. According to a report by the Regional European Office of the World Health Organization, Bulgarian children aged 11-13 rank highly in terms of alcohol use and abuse, tobacco products, and cannabis use [8]. The situation is similar to the consumption of fast food in combination with physical inactivity [9, 10].

It is critical to recognize that health-risk behaviors are the most common sources of morbidity among adolescents [11]. Muñoz-Pindado et al. note that the presence of one behavioral health risk factor often leads to others, recommending the creation of preventive programs targeting this age group [12].

Research teams such as Dyachuk et al. and Khan et al. also advocate for the introduction of measures to correct behavioral risk factors [13, 14]. In some countries, systematic observations and health education programs are conducted among junior high school students [15-20].

Garov highlights that the level of health knowledge directly impacts an individual's health status [21].

Significant correlations have been found between health knowledge and adolescent health behavior [22]. It is important to note that individuals with lower health literacy are more likely to trust dubious sources of health information, posing additional health risks [23]. Supporting this, Timoshilov & Lastovetckii have shown that independent searching for drug information on the Internet can have detrimental effects, suggesting that widespread implementation of targeted advanced training is necessary [4].

According to Kolmaga et al. health education should be compulsory in school [24]. Perelman et al. prove that the school as an institution and environment plays an important role in preventing smoking among adolescents [25]. I would also add in the prevention of the use of alcohol and narcotic substances, the prevention of unhealthy eating habits, and the fight against hypo- and adynamia. For this purpose, complex health and educational activities with a preventive purpose must be undertaken among the students.

Within Bulgaria, Slavchev recommends harnessing the efforts of the entire society and all institutions, including schools [26]. A decade earlier, Terzieva established the same need to develop and create a health education and educational program in order to master the growing knowledge about health, its protection, and preservation [27].

This study aimed to assess the level of knowledge and attitudes of teenagers towards certain health risk factors (tobacco smoking, use of narcotic substances, alcohol consumption, eating fatty and caloric foods, and lack of physical activity) to determine the need for more in-depth health education among them.

Materials and Methods

In February 2023, a survey was conducted through direct group interviews among 71 children aged 11-13, in two primary schools in the municipality of Pleven, Bulgaria. The participants were students from three different fifth-grade classes in two primary schools in the city of Pleven. The schools and classes were randomly selected. All students studying in the designated grades were included in the survey. The children were interviewed after obtaining written informed consent from their parents. An original questionnaire containing 29 logically connected questions, adapted to the children's age, was used. The questionnaire format included 4 introductory questions, 2 filter questions, 21 main questions, and 2 open-ended questions. The main questions were directly related to the survey topic. Of all the questions: 24 were closed-ended; 12 allowed for more than one answer; 3 were semi-closed (allowing for more than one answer or an additional opinion). The two open-ended questions were designed to gather detailed responses. In six of the closed-ended questions, a three-point scale was used with options "yes," "no," and "I don’t know," and in 5 questions a binary "yes" or "no" option was provided. This questionnaire enables the investigation of the teenagers' knowledge levels and attitudes towards the issues at hand.

Survey data were processed using SPSS Statistics 25 and Excel for Windows statistical software packages. The results are presented through graphs and numerical indicators such as structure, frequency, averages, correlation coefficients, and others. Both the χ2 and Fisher's exact test criteria were applied.

Findings

Seventy-one children aged 11-13 from two primary schools in the city of Pleven participated in the study. The majority were 11-year-olds, making up 78.9% (n=71), followed by 12-year-olds at 16.9% (n=71). Regarding gender distribution, boys represent 50.7% (n=36) and girls 49.3% (n=35). A significant proportion, 77.5% (n=55), reported having older children in their circle of friends. According to 97.2% (n=69) of the children, health is valued. Nearly 44% (n=31) of the children believe that a person is healthy when they experience no pain and 32.4% (n=23) associate health with the absence of a diagnosed disease. Meanwhile, 52.10% (n=37) define health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being (Figure 1). The results indicate that the choice of wording for "healthy person" is not based on knowledge and understanding, but appears to be random (df=1, χ2=1.891, p=0.1, r=0.16).

Figure 1. Characteristics of a healthy person.

According to 95.8% (n=68) of the surveyed adolescents, a person’s health depends solely on their lifestyle. Only 4.2% (n=3) believe that health also depends on the individual’s age and gender.

The children were asked to identify actions they consider non-hazardous to their health. Impressively, the children were well-informed about three health-related factors: exercise, fruit and vegetable consumption, and rational nutrition. However, it is concerning that more than half (66.2%; n=47) considered dieting to reduce body mass as safe. Additionally, a smaller but notable proportion believed it is safe to consume foods containing refined sugar, carbonated drinks, burgers and chips, and use electronic devices. There were also children who thought the use of tobacco products, alcohol, cigarettes, and drugs was safe (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Characteristics of a safe diet for health.

Nearly 41% of children (29) admitted that they wanted to try at least one of the following: alcohol, cigarettes, smokeless cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, or marijuana. When asked "What would provoke them to try these?", 28.2% (20) answered curiosity, and 12.7% (9) would do it because it is considered fashionable. A stronger motive influencing teenagers was the trendiness (df=1, χ2=14.867, p=0.001, r=0.456), with curiosity having a slightly weaker influence (df=1, χ2=10.200, p<0.05, r=0.38). Age (df=2, χ2=0.91, p=0.1, r=0.1) and gender (df=2, χ2=0.91, p=0.1, r=0.1) of the children had no significant effect. More than half of the children (69%; n=49) believed that trying drugs could endanger their health. However, it is concerning that some still think it is not dangerous (12.7%; n=9), and others are unaware of the consequences (18.3%; n=13).

A significant proportion of the respondents (54.9%; n=39) believed that using drugs can help one forget their problems. Unfortunately, the effects are diverse and often have severe consequences, which the results indicated the children were not fully aware of. It is alarming that 29.6% (21) said there are children in their circle of friends who use drugs. Only 14.1% (10) acknowledged being offered a narcotic substance. There was a moderate correlation between knowing someone who uses drugs and being offered drugs themselves (df=2, χ2=7.446, p=0.025, r=0.31). The presence of older children in their circle of friends did not significantly influence whether the surveyed children were offered drugs (df=3, χ2=2.977, p=0.1, r=0.1) nor their desire to try them (df=3, χ2=0.263, p=0.1, r=0.134). However, it is a reason why some teenagers want to try smoking (df=3, χ2=16.823, p=0.001, r=0.328). Almost half of them (46.5%; n=33) claimed that there are children who smoke in their circle of friends. Although they were aware of the harmful effects of tobacco use (Figure 3), 44.8% (32) have tried one or more of the following: a cigarette, electronic cigarette, hookah, or smokeless cigarette. In this case, no cause-and-effect relationship was observed between knowledge and behavior in teenagers (df=1, χ2=0.34, p=0.1, r=0.06). Boys and girls are equally exposed to this behavioral risk factor (df=1, χ2=1.015, p=0.1, r=0.1).

Figure 3. Effects of cigarettes on health state according to students.

Regarding alcohol, 90.1% (64) of teenagers firmly stated that it is harmful to their health. A significant proportion, 76.1% (n=54), were convinced that their peers have tried alcohol, and 59.2% (42) claim to know such individuals personally. Additionally, a considerable number, 47.9% (n=34), admitted they have tried alcohol themselves. However, there was neither a regular difference between boys and girls (df=1, χ2=2.471, p=0.1, r=0.19) nor a causal relationship between "awareness and behavior" (df=2, χ2=4.138, p=0.1, r=0.1).

The surveyed students strongly believed that to be healthy, one must engage in sports (85.9%; n=61). Yet, nearly 30% (20) preferred to play electronic games in their free time, and 18.3% (13) opted to watch TV. Boys were significantly more likely to prefer electronic games (df=1, χ2=10.08, p=0.001, r=0.38). Watching television showed no significant differences based on the gender of the children (df=2, χ2=4.52, p=0.1, r=0.1).

A vast majority of teenagers (91.5%; n=65) recognized that a varied diet is important for maintaining health. More than half (57.75%; n=34) preferred to consume cooked meals, fruits, and vegetables, though their preferences were slightly influenced by their knowledge of varied nutrition (df=1, χ2=5.085, p=0.025, r=0.27). However, there was a group of children (37.8%; n=27) who found it appropriate to consume burgers, chips, waffles, biscuits, and chocolate. Their dietary choices were not significantly influenced by their nutritional knowledge (df=1, χ2=0.139, p=0.1, r=0.04).

Discussion

Health is universally valued, yet in our busy daily lives, we often neglect it. Children also define health as a value, but what is interesting is their interpretation of what constitutes a "healthy person," as shown in Figure 1. Unfortunately, the results indicate that they are not aware of the full content of the concept, and their explanations reflect this misunderstanding. This trend, however, is not limited to the children surveyed but is observed across our entire society. For many people, the absence of pain or infirmity is mistakenly interpreted as a state of good health.

It is particularly concerning that the results of this study reaffirm that the 11-13 age group is especially vulnerable to behavioral health risk factors. Some adolescents in this age group have peers who have experimented with drugs, tobacco products, and alcohol; others have been offered narcotics; a third group, despite some awareness, engages in health-risk behaviors like using tobacco and alcohol at a tender age. The likely reasons for the use of alcohol and tobacco products are their widespread availability and social acceptance. The influence of the family environment as a contributing factor should not be overlooked.

In Bulgaria, smoking and alcohol consumption among both adults and adolescents represent significant public health challenges. Our country ranks among the top in the European :union: for these two behavioral health risk factors [28]. Although the use of tobacco products and alcohol may not be perceived by society as a direct threat to health, this risky behavior should not be ignored, especially in children. It has been shown that teenagers who exhibit even one behavioral risk factor are highly likely to develop additional risk behaviors [29]. This is a critical issue that should not be overlooked due to its potential domino effect on both personal and public health.

The results showing children's knowledge of health risk factors are concerning. This is not entirely surprising, given the limited hours devoted to health education in schools, which mainly focus on healthy eating. The training that occurs is integrated into the general education curriculum. There is no dedicated general education subject specifically focused on health-relevant knowledge and the development of skills for health-protective behavior. Despite long-standing evidence-based recommendations for implementing health education in schools effectively, it is clear that such measures are not being adequately implemented, and the negative impacts are apparent. The minimal knowledge demonstrated by students, and some even displaying health-risk behaviors, indicates that the traditional methods of delivering health-promotional information are ineffective. The formal presentation of health and education topics within various curricula does not yield positive results. Theoretical training alone is insufficient. Protective health behavior is not being instilled in children. There is a lack of engagement and stimulation to preserve one's own health and that of others, and responsibility for health is not being developed. The facts reported are unable to sufficiently interest young people, failing to help them understand the problems and ignite a desire to be part of the solution.

Although health education is regulated among adolescents in Bulgaria, studies show that it is not sufficiently developed, does not reach all students, and is limited to a few locations [30, 31]. Georgieva & Kamburova have noted that "over 80% of health education activities use traditional and unattractive methods or do not meet the informational needs of students, who are treated as a passive audience in this process." They suggest that school health education should be tailored to the needs and interests of the students [32]. Boncheva & Dokova surveyed students who described their knowledge of health issues received in secondary school as incomplete or absent [33]. This gap in education is a major factor contributing to the negative trends in the health status and behaviors of Bulgarian children. According to Borisova & Mihaylov, students are positively inclined toward having a health education subject in school and are motivated to learn about health topics and participate in activities that enhance their health culture, showing a preference for non-formal education and interactive methods [31]. Hizhov & Prokopov have developed a model for a health education program aimed at junior high school students, but the effects of its implementation have not yet been detailed [34].

Childhood and adolescence are critical periods during which children shape their character and behavior. This is when they are most receptive to adopting new patterns of behavior. It is essential to use this time to impart health knowledge and build a solid health culture.

Given the findings about the risky behaviors of Bulgarian adolescents and their level of health culture from both the literature review and this study, the implementation of mandatory health and educational measures for adolescents in our country is extremely urgent.

Conclusion

Children possess only superficial knowledge about health and its various aspects. They are somewhat familiar with some of the factors that influence health. Regarding behavioral risk factors, their knowledge is insufficient to serve as a basis for making sound health decisions. The level of health culture among adolescents is unsatisfactory.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all those who responded to the survey.

Ethical Permissions: The questionnaires used were originally developed for the aims of the study and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Medical University-Pleven, Bulgaria.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interest were reported.

Authors’ Contribution: Markova G (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (100%)

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Program ‘Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Students-2’.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2023/12/4 | Accepted: 2024/01/6 | Published: 2024/02/5

Received: 2023/12/4 | Accepted: 2024/01/6 | Published: 2024/02/5

References

1. Coban FR, Kunst AE, Van Stralen MM, Richter M, Rathmann K, Perelman J, et al. Nicotine dependence among adolescents in the European :union:: How many and who are affected?. J Public Health. 2019;41(3):447-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdy136]

2. Wartberg L, Kriston L, Thomasius R. Prevalence of problem drinking and associated factors in a representative German sample of adolescents and young adults. J Public Health. 2019;41(3):543-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdy163]

3. Collese TS, De Moraes ACF, Fernández-Alvira JM, Michels N, De Henauw S, Manios Y, et al. How do energy balance-related behaviors cluster in adolescents?. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(2):195-208. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00038-018-1178-3]

4. Timoshilov VI, Lastovetckii AG. The prevention of drug substances abuse among schoolchildren. Problemy Sotsial'noi Gigieny, Zdravookhraneniia I Istorii Meditsiny. 2019;27(3):273-6. [Russian] [Link]

5. Resiak M, Walentukiewicz A, Łysak-Radomska A, Woźniak K, Skonieczny P. Determinants of overweight in the population of parents of school-age children. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2019;32(5):677-93. [Link] [DOI:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01455]

6. Nowak M, Papiernik M, Mikulska A, Czarkowska-Paczek B. Smoking, alcohol consumption, and illicit substances use among adolescents in Poland. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2018;13:42. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13011-018-0179-9]

7. Merdzhanova E, Petrova G, Vakrilova-Becheva M. Spread of health risk factors among adolescents from Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49(8):1569-70. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v49i8.3904]

8. Inchley J, Currie D, Budisavljevic S, Torsheim T, Jaastad A, Cosma A, et al., editors. Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report. Volume 1. Key findings. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. [Link]

9. Duleva V, Chikova-Ishchener E, Rangelova L, Petrova S, Dimitrov P, Bozhilova D. Report on Bulgaria European initiative WHO monitoring childhood obesity. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2017. [Bulgarian] [Link]

10. Petrova G, Merdzhanova E, Lalova V, Angelova P, Raycheva R, Boyadjiev N. Study of the nutritional behavior as a risky health factor of adolescents from different ethnic groups in the municipality of Plovdiv, Bulgaria. J IMAB. 2020;28(3):4456-60. [Link] [DOI:10.5272/jimab.2022283.4456]

11. Richardson L, Parker EO, Zhou C, Kientz J, Ozer E, McCarty C. Electronic health risk behavior screening with integrated feedback among adolescents in primary care: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e24135. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/24135]

12. Muñoz-Pindado C, Muñoz-Pindado C, Roura-Poch P, Riesco-Miranda JA, Muñoz-Méndez J. Smoking prevalence in high school students in the Barcelona region (De Osona district). Semergen. 2019;45(4):215-24. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.semerg.2018.11.004]

13. Dyachuk DD, Zabolotna IE, Yaschenko YB. Analysis of the extension of childhood expectations and evaluation of the risks of the development of diseases associated with overweight. Wiad Lek. 2018;71(3 pt 1):546-50. [Ukrainian] [Link]

14. Khan A, Lee EY, Rosenbaum S, Khan SR, Tremblay MS. Dose-dependent and joint associations between screen time, physical activity, and mental wellbeing in adolescents: An international observational study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(10):729-38. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00200-5]

15. Lazzeri G, Vieno A, Charrier L, Spinelli A, Ciardullo S, Pierannunzio D, et al. The methodology of the Italian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2018 study and its development for the next round. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022;62(4):E926-33. [Link]

16. Herbenick SK, James K, Milton J, Cannon D. Effects of family nutrition and physical activity screening for obesity risk in school-age children. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2018;23(4):e12229. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jspn.12229]

17. Zagà V, Giordano F, Gremigni P, Amram DL, De Blasi A, Amendola M, et al. Are the school prevention programmes-aimed at de-normalizing smoking among youths-beneficial in the long term? An example from the Smoke Free Class Competition in Italy. Annali Di Igiene. 2017;29(6):572-83. [Link]

18. Vieira S, Cheruel F, Sancho-Garnier H. Profile of first year secondary school children involved in the anti-smoking prevention trial "PEPITES". Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2019;67(2):114-9. [French] [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.respe.2018.11.018]

19. Maceinaitė R, Šurkienė G, Žandaras Z, Stukas R. The association between studying in health promoting schools and adolescent smoking and alcohol consumption in Lithuania. Health Promot Int. 2021;23;36(6):1644-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daab014]

20. Brinker TJ, Buslaff F, Haney C, Gaim B, Haney AC, Schmidt SM, et al. The global medical network education against tobacco-voluntary tobacco prevention made in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61(11):1453-61. [German] [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00103-018-2826-8]

21. Garov S. Development of health literacy. Varna Med forum. 2018;7(1):187-91. [Bulgarian] [Link] [DOI:10.14748/vmf.v7i1.4927]

22. Fleary SA, Joseph P, Pappagianopoulos JE. Adolescent health literacy and health behaviors: A systematic review. J Adolesc. 2018;62:116-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.010]

23. Chen X, Hay JL, Waters EA, Kiviniemi MT, Biddle C, Schofield E, et al. Health literacy and use and trust in health information. J Health Commun. 2018;23(8):724-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2018.1511658]

24. Kolmaga A, Trafalska E, Szatko F. Risk factors of excessive body mass in children and adolescents in Łódź. Ann Natl Inst Hygiene. 2019;70(4):369-75. [Link] [DOI:10.32394/rpzh.2019.0085]

25. Perelman J, Leão T, Kunst AE. Smoking and school absenteeism among 15- to 16-year-old adolescents: A cross-section analysis on 36 European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(4):778-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckz110]

26. Slavchev S. Health literacy as a priority of preventive medicine. Gen Med. 2021;23(1):69-74. [Bulgarian] [Link]

27. Terzieva G. Student's health culture at the early school age. Manag Educ. 2010;6(4):327-35. [Bulgarian] [Link]

28. OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. State of health in the EU-Bulgaria: Health profile of the country 2021. Brussels: OECD Publishing; 2021. [Bulgarian] [Link]

29. Chamova G. The role of significant other factors for grouping of risk behaviours in regulary drinking juveniles. Social Medicine. 2014;22(2):22-4. [Bulgarian] [Link]

30. Tsokov G. Ordinance No. 13/21 September 2016 on civic, health, environmental and intercultural education. Effective from 11.10.2016. Minist Educ Sci. 2018;80. [Bulgarian] [Link]

31. Borisova I, Mihaylov N. Attitudes toward the introduction of health education as a new discipline in the high school curriculum among Bulgarian students. Health Econ Manag. 2020;2(76):23-8. [Bulgarian] [Link] [DOI:10.14748/hem.v20i2.7676]

32. Georgieva S, Kambourova M. School health education in Bulgaria-characteristics and directions for improvement. Proceedings of the 4th Electronic International Interdisciplinary conference. 2015;1(4):220-2. [Link] [DOI:10.18638/eiic.2015.4.1.454]

33. Boncheva P, Dokova K. Health promotion in the secondary Bulgarian schools. Varna Med Forum. 2018;7(3):61-5. [Bulgarian] [Link]

34. Hidjov A, Prokopov I. Model of a health education program for students from the junior high school stage. i Continuing Education. 2020;15:2. [Bulgarian] [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |