Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 67-72 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mukarramah S, Amdadi Z. Development of a Continuity of Care Model in Midwifery Services. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :67-72

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72754-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72754-en.html

1- Midwifery Department, Health Polytechnic of Ministry of Health Makassar, Makassar, Indonesia

Keywords: Growth and Development [Mesh], Continuity of Patient Care [MeSH], Midwifery [MeSH], Knowledge [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 644 kb]

(3362 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1795 Views)

Full-Text: (224 Views)

Introduction

The maternal mortality rate (MMR) in Indonesia remains alarmingly high, with the country ranked third-highest in the South Asia and Southeast Asia regions [1]. In response, the government has initiated several strategic programs aimed at improving maternal and child health, with a focus on reducing the MMR and infant mortality rate (IMR). These efforts include the Safe Motherhood Initiative, the Making Pregnancy Safer (MPS) Program, and the Childbirth Planning and Complication Prevention Program (P4K), all of which support the 5th goal of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Despite these efforts, the effectiveness of these policies in fully meeting maternal and child health needs has been less than satisfactory in practice [2].

Midwives play a vital role within communities in reducing MMR and IMR [2, 3]. As frontline health workers intimately involved with the community, midwives provide continuous and comprehensive services. Their work focuses on preventive care, health education, counseling, health promotion, and support during normal deliveries. They also foster partnerships with women, empowering them and facilitating early detection in cases requiring obstetric referral [4-6].

As the primary providers of midwifery care, midwives are essential in accelerating efforts to reduce MMR and IMR [7]. Therefore, it is crucial for midwives to not only adhere to established standards of midwifery care but also to embody the philosophy of women-centered midwifery care in their qualifications [8-10]. Advancing these qualifications requires the adoption of a continuity of care (CoC) model in midwifery services [11-13].

In line with government initiatives to improve maternal and child health, midwives are entrusted with providing continuous midwifery services, encompassing CoC from antenatal care (ANC), intrapartum care, newborn and neonatal care, to postnatal care, and quality family planning services [14]. Midwives are expected to conduct their practices based on a physiological approach, applying and enhancing a midwifery care model grounded in evidence-based practice [2, 15, 16].

Research from Australia indicates a higher rate of cesarean sections compared to other countries, alongside a lack of support for natural childbirth. The adoption of CoC models has the potential to increase the rate of vaginal births after cesarean (VBAC) and provide a greater sense of security for both mothers and infants [9, 17, 18].

The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses the CoC model for midwifery care, advocating for consistent care throughout the entire childbearing process. This approach focuses on monitoring the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social well-being of women and families. It involves providing women with education, counseling, personalized ANC, and support during labor, birth, and the immediate postpartum period by a familiar midwife [19]. The model further emphasizes the importance of ongoing support during the postpartum period, reducing unnecessary technological interventions, and efficiently identifying, referring, and coordinating care for women in need of specialized attention. Developing a more effective and patient-centered CoC model is essential for both midwives and their patients [11].

Previous research underscores the importance of providing meaningful and focused care to women during pregnancy and childbirth [13]. Studies by Seibold and colleagues have shown that students' experiences led to personal growth, with their follow-up experiences rated as valuable learning opportunities [4]. This research highlighted that such experiences equip midwifery students with a comprehensive understanding of the midwifery care philosophy, enabling them to deliver woman-centered care through the CoC clinical learning model [20].

The current study aimed to develop CoC modules for midwifery students engaged in maternity care [17, 18]. It took an innovative approach by involving women/clients and their families as decision-makers in the provision of midwifery services. The creation of the module in this study represents a proactive and preventative measure to improve maternal and child health through the education of midwifery students. Given that 85% of pregnancy care providers in Indonesia are midwives [21], this research is notable for its novelty in developing a CoC module for midwifery students that includes the involvement of clients and their families (CoC).

The main goal of this study was to develop a model (CoC) that helps midwifery students identify clients/patients and provide continuous care from the early stages of pregnancy.

Instrument and Methods

Research Design

This study employed a design and development methodology, incorporating a mixed-methods approach [22]. It followed the stages of the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) framework [23], to guide the product design and development process. Additionally, the design phase of the intervention product was based on the intervention design model proposed by Dick et al. [24]. The goal of the educational media developed in this research was to introduce a model (CoC) that supports midwives in patient identification and reduces unnecessary interventions, thereby decreasing the occurrence of delayed responses in maternal-neonatal emergencies.

The outputs of this development process referred to as artifacts, were designed to offer solutions to specific practical issues. Specifically, these artifacts involved the use of computer-based expert systems aimed at creating a model (CoC) to assist midwives in efficiently identifying patients and reducing unnecessary interventions to tackle the problem of delayed management in maternal-neonatal emergencies. This intervention model was subject to field testing employing a quasi-experimental design, namely a two-group pre-test post-test design with a control group.

Participants

The study's participants included midwifery professional students and active midwives providing continuous midwifery care in various healthcare facilities in Makassar City, Indonesia. The research was conducted from April to October 2022, involving a total of 43 students and 6 midwives who were randomly selected based on predefined selection criteria to participate in the study.

Sample Size

A total of 49 students were determined using Slovin's formula with an alpha level of 0.05, from a total population of 57 individuals. According to Masturoh and Anggita [25], the sample size was calculated using the Taro Yamane formula as follows:

n=Number of samples

N=Number of populations

d=Precision

Instrument

The research tools included a questionnaire developed by the researcher, which underwent validation and was deemed suitable. For the needs analysis phase, the questionnaire comprised 15 questions covering the spectrum of midwifery services from early pregnancy to the postpartum period, offering "yes" and "no" response options. A "yes" response was scored as 1, while a "no" response received a score of zero, with respondent scores ranging from 0 to 15.

Another instrument evaluated participants' knowledge regarding CoC through ten questions, each with correct and incorrect answer options. Correct answers were scored as one, incorrect as zero, allowing for a total score range between zero and ten for respondents.

Statistical Analysis

In the preliminary analysis phase, qualitative data was collected, especially at the needs analysis stage through initial observation activities. This phase utilized an inductive approach to construct the analysis from basic observations. Quantitative data analysis was conducted univariately to determine the percentage or level of the problem or indicator identified. This analysis, derived from both students and midwives providing services, aimed to evaluate data gathered during the needs analysis stage through descriptive statistics, narrating, and interpreting the necessity for practical solutions based on the problems identified.

During the prototype development phase, expert validation was presented qualitatively. In the one-on-one trial phase, qualitative analysis techniques, notably the spiral method, were applied to identify product weaknesses and deficiencies.

In the small group testing phase, qualitative data underwent scrutiny to enhance product quality, complemented by statistical analysis of quantitative data from questionnaires and observations.

For the field test, data was described in terms of frequency distribution, and a t-test was employed to determine the causal relationship between the use of the product and its impact. Data analysis was done using SPSS version 24.

Findings

This research was conducted at three health centers in Makassar: Public Health Center (PHC) Kassi-Kassi, Tamalate, and Panambungan, structured into three main phases: module development, implementation, and evaluation. Here is a summary of each phase along with the research outcomes:

Research Module Development

In the initial stage, the module development method utilized was the Research and Development (R&D) approach. This development process encompassed the following stages:

A. Analysis

The needs analysis stage involved conducting a literature study, encompassing journal reviews and adhering to literature review guidelines.

B. Design

The module's design was implemented through the editor under the supervision of the material expert. This module comprised a single module package. Upon completion of this module, students and midwives were anticipated to achieve the following objectives:

1) Knowing the concept of the continuum of care

2) Knowing the care provided in the continuum of care concept

3) Conducting continuum of care

4) Perform documentation for the continuum of care

Furthermore, the module content material was collected and test items were developed to measure the user's ability.

C. Development

1) Module media creation

The development of the module was executed utilizing the Bookcreator application, overseen by editor Ridho. This module encompasses sections such as the cover, title page, table of contents, preface, content, conclusion, questionnaire, and bibliography.

2) Validation of module feasibility

a) Material expert validation

The material expert validation questionnaires involved sending modules and validation questionnaires to two experts. The results of the material expert validation were based on responses provided by these two experts with expertise in midwifery.

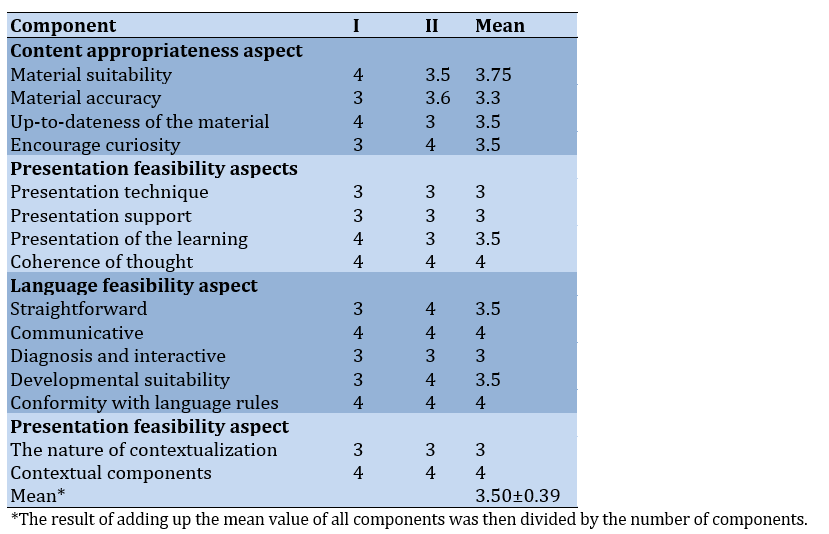

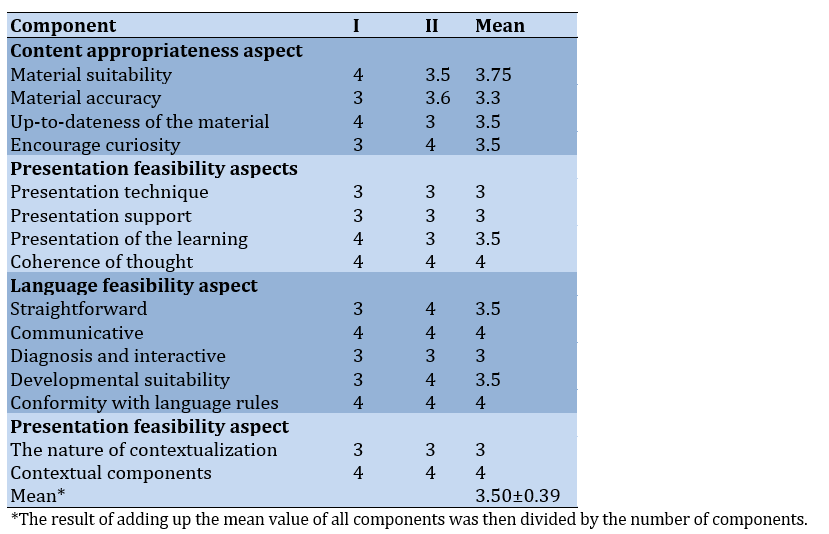

Table 1 showcases the results from the material expert review of the two materials, highlighting that the developed CoC module is rated as "very good" in terms of quality and feasibility. This rating is supported by the average percentage across four evaluated aspects of the module, documented at 3.50±0.39.

Table 1. Results of material expert validation

b) Media expert validation

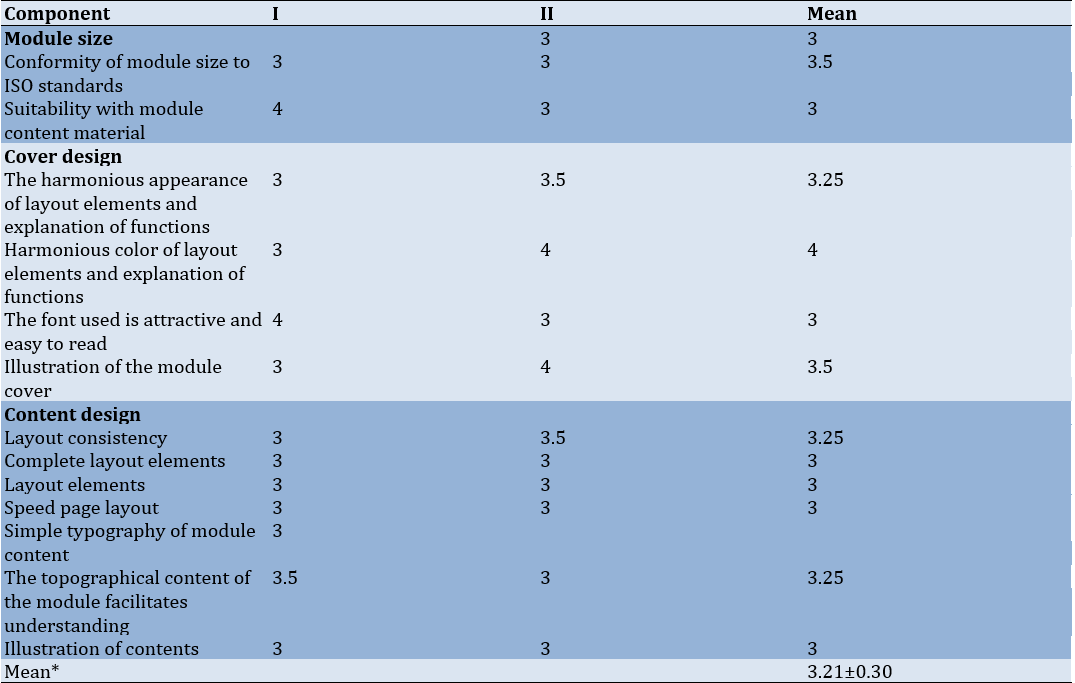

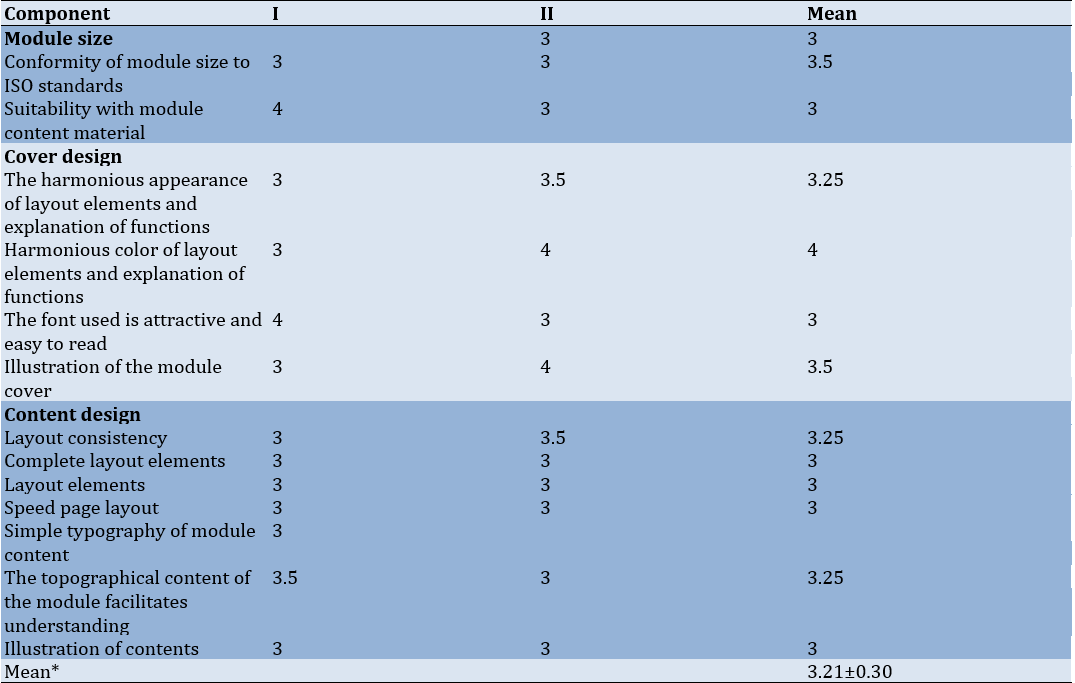

Table 2 reveals the feedback from two media experts, indicating that the overall quality and feasibility of the developed CoC module are considered "very good". This evaluation is reflected in the average percentage across three dimensions of the module, noted at 3.21±0.30.

Table 2. Results of media expert validation

Implementation

Implementation was carried out on a small sample trial with 15 professional students, yielding the following results:

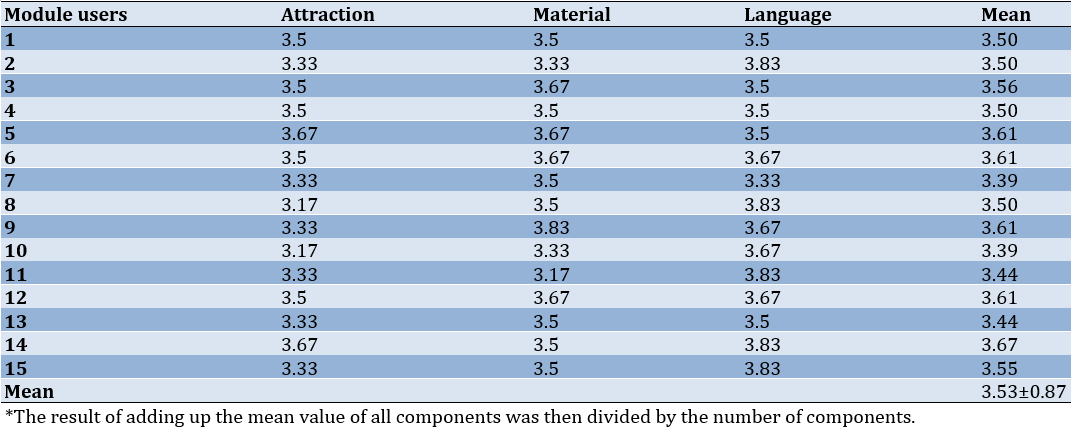

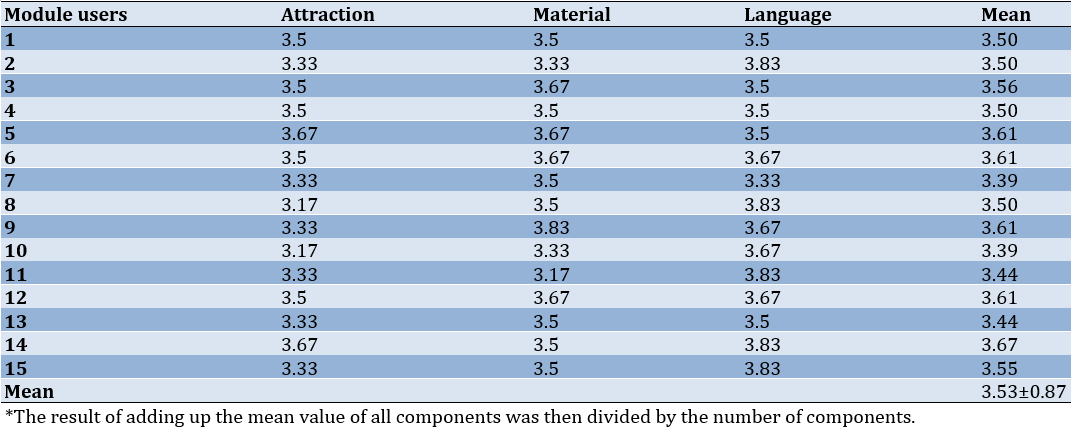

Table 3 summarizes the feedback from 15 small sample users, specifically students, demonstrating that the developed CoC module was assessed as "very good" in terms of overall quality and feasibility evidenced by the average score for the module's components, which is 3.53±0.87.

Table 3. Analysis of small sample trial results

Evaluation

To assess the effectiveness of the maternal health module, the presentation of data included both pretest and posttest results for 30 pregnant women, showcasing the improvement following the module's implementation.

The average knowledge score prior to the module trial stood at 67.08, but after the trial, it increased to 89.14. This significant rise in knowledge scores, by 22.06 points before and after the educational intervention, underscores the effectiveness of the CoC module in improving student knowledge. A paired t-test resulted in a p-value of 0.002, signifying a statistically significant improvement.

Discussion

CoC in midwifery represents an ongoing, holistic approach to providing services that span pregnancy, childbirth, the postpartum period, newborn care, and family planning, specifically designed to cater to the unique health requirements and personal situations of each individual [4, 8].

The essence of the CoC model emphasizes fostering conditions for natural childbirth, with the goal of assisting women in giving birth with minimal medical interventions while attentively caring for their physical, psychological, spiritual, and social health, as well as that of their families [16]. This model integrates a comprehensive suite of services during pregnancy, labor, and the postpartum period, providing women with tailored information and support. Despite these ideals, a notable challenge remains: many midwives offer fragmented services, which can lead to the delayed identification of emergency complications in the postnatal period [26].

The objective of this research was to create a viable midwifery service model that covers pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum, newborn care, and family planning. The findings demonstrate that the newly developed model substantially improved the knowledge of both students and practicing midwives regarding the CoC model, as confirmed by test results with a p-value<0.05. The adoption of the CoC approach requires students to administer midwifery care that is centered around the needs of pregnant women, adhering to the principles of both CoC and comprehensive care. By providing this continuous, all-encompassing, woman-focused care, students are able to form a deeper connection with their patients, acknowledging the varied needs of each one, which ultimately leads to personalized care plans.

A study from Norway by Aune et al. [20] underscored the positive impact of implementing CoC on student midwives' knowledge within the midwifery discipline. CoC facilitates enduring relationships between student midwives and women, fostering mutual trust and encouraging personal growth. This dynamic enables students to appreciate the importance of personalized, holistic care and to understand the comprehensive duties of a midwife.

The educational approach adopted incorporates modules across three cycles: the first cycle addresses midwifery care during pregnancy; the second focuses on care during labor; and the third cycle is dedicated to postpartum midwifery care. Each cycle includes four phases and features collaborative meetings involving students, academic lecturers, and practicing midwives. These sessions act as a forum for evaluating clinical competencies (ANC, intranatal care, postnatal care) and discussing case studies [2, 5, 27]. Furthermore, students are allocated a CoC caseload, which requires them to accompany a client from the prenatal stage through childbirth to the postnatal phase. This engagement provides students with a continuous learning journey in midwifery care, culminating in the production of a detailed client report and a logbook of care activities. Through this process, students acquire hands-on experience in providing consistent care, reflective of midwifery principles, and are presented with numerous opportunities to refine their clinical skills through each client interaction [6, 10].

Participants in this study expressed positive feedback about their experiences acting as midwives within the CoC framework, particularly emphasizing the development of close bonds with their clients through the consistent delivery of midwifery care [12, 18]. The opportunity to support clients and their families endowed students with a sense of purpose, which in turn, enhanced their self-esteem. Through their involvement in the ongoing provision of midwifery care, students reported an increased confidence in their caregiving abilities. This aligns with existing research, which suggests that relational learning can significantly improve students' clinical skills and bolster their confidence as healthcare providers [28].

This study's limitations include its small sample size and the restriction of its participant pool to students from a single university, leading to a lack of diversity among participants. For a more comprehensive validation of the educational model developed through this module, future research should aim to include larger and more varied sample sizes.

Conclusion

Implementing the CoC educational module is effective in improving participants' understanding of the factors contributing to the delayed recognition of emergency complications, especially in the postnatal phase.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: The study was performed in accordance with the ethical considerations of the Helsinki Declaration. This study obtained ethical feasibility under the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health, Makassar (726/KEPK-PTKMKS/VII/2022).

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: Mukarramah S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/ (60%); Amdadi ZA (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: None declared.

The maternal mortality rate (MMR) in Indonesia remains alarmingly high, with the country ranked third-highest in the South Asia and Southeast Asia regions [1]. In response, the government has initiated several strategic programs aimed at improving maternal and child health, with a focus on reducing the MMR and infant mortality rate (IMR). These efforts include the Safe Motherhood Initiative, the Making Pregnancy Safer (MPS) Program, and the Childbirth Planning and Complication Prevention Program (P4K), all of which support the 5th goal of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Despite these efforts, the effectiveness of these policies in fully meeting maternal and child health needs has been less than satisfactory in practice [2].

Midwives play a vital role within communities in reducing MMR and IMR [2, 3]. As frontline health workers intimately involved with the community, midwives provide continuous and comprehensive services. Their work focuses on preventive care, health education, counseling, health promotion, and support during normal deliveries. They also foster partnerships with women, empowering them and facilitating early detection in cases requiring obstetric referral [4-6].

As the primary providers of midwifery care, midwives are essential in accelerating efforts to reduce MMR and IMR [7]. Therefore, it is crucial for midwives to not only adhere to established standards of midwifery care but also to embody the philosophy of women-centered midwifery care in their qualifications [8-10]. Advancing these qualifications requires the adoption of a continuity of care (CoC) model in midwifery services [11-13].

In line with government initiatives to improve maternal and child health, midwives are entrusted with providing continuous midwifery services, encompassing CoC from antenatal care (ANC), intrapartum care, newborn and neonatal care, to postnatal care, and quality family planning services [14]. Midwives are expected to conduct their practices based on a physiological approach, applying and enhancing a midwifery care model grounded in evidence-based practice [2, 15, 16].

Research from Australia indicates a higher rate of cesarean sections compared to other countries, alongside a lack of support for natural childbirth. The adoption of CoC models has the potential to increase the rate of vaginal births after cesarean (VBAC) and provide a greater sense of security for both mothers and infants [9, 17, 18].

The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses the CoC model for midwifery care, advocating for consistent care throughout the entire childbearing process. This approach focuses on monitoring the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social well-being of women and families. It involves providing women with education, counseling, personalized ANC, and support during labor, birth, and the immediate postpartum period by a familiar midwife [19]. The model further emphasizes the importance of ongoing support during the postpartum period, reducing unnecessary technological interventions, and efficiently identifying, referring, and coordinating care for women in need of specialized attention. Developing a more effective and patient-centered CoC model is essential for both midwives and their patients [11].

Previous research underscores the importance of providing meaningful and focused care to women during pregnancy and childbirth [13]. Studies by Seibold and colleagues have shown that students' experiences led to personal growth, with their follow-up experiences rated as valuable learning opportunities [4]. This research highlighted that such experiences equip midwifery students with a comprehensive understanding of the midwifery care philosophy, enabling them to deliver woman-centered care through the CoC clinical learning model [20].

The current study aimed to develop CoC modules for midwifery students engaged in maternity care [17, 18]. It took an innovative approach by involving women/clients and their families as decision-makers in the provision of midwifery services. The creation of the module in this study represents a proactive and preventative measure to improve maternal and child health through the education of midwifery students. Given that 85% of pregnancy care providers in Indonesia are midwives [21], this research is notable for its novelty in developing a CoC module for midwifery students that includes the involvement of clients and their families (CoC).

The main goal of this study was to develop a model (CoC) that helps midwifery students identify clients/patients and provide continuous care from the early stages of pregnancy.

Instrument and Methods

Research Design

This study employed a design and development methodology, incorporating a mixed-methods approach [22]. It followed the stages of the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) framework [23], to guide the product design and development process. Additionally, the design phase of the intervention product was based on the intervention design model proposed by Dick et al. [24]. The goal of the educational media developed in this research was to introduce a model (CoC) that supports midwives in patient identification and reduces unnecessary interventions, thereby decreasing the occurrence of delayed responses in maternal-neonatal emergencies.

The outputs of this development process referred to as artifacts, were designed to offer solutions to specific practical issues. Specifically, these artifacts involved the use of computer-based expert systems aimed at creating a model (CoC) to assist midwives in efficiently identifying patients and reducing unnecessary interventions to tackle the problem of delayed management in maternal-neonatal emergencies. This intervention model was subject to field testing employing a quasi-experimental design, namely a two-group pre-test post-test design with a control group.

Participants

The study's participants included midwifery professional students and active midwives providing continuous midwifery care in various healthcare facilities in Makassar City, Indonesia. The research was conducted from April to October 2022, involving a total of 43 students and 6 midwives who were randomly selected based on predefined selection criteria to participate in the study.

Sample Size

A total of 49 students were determined using Slovin's formula with an alpha level of 0.05, from a total population of 57 individuals. According to Masturoh and Anggita [25], the sample size was calculated using the Taro Yamane formula as follows:

n=Number of samples

N=Number of populations

d=Precision

Instrument

The research tools included a questionnaire developed by the researcher, which underwent validation and was deemed suitable. For the needs analysis phase, the questionnaire comprised 15 questions covering the spectrum of midwifery services from early pregnancy to the postpartum period, offering "yes" and "no" response options. A "yes" response was scored as 1, while a "no" response received a score of zero, with respondent scores ranging from 0 to 15.

Another instrument evaluated participants' knowledge regarding CoC through ten questions, each with correct and incorrect answer options. Correct answers were scored as one, incorrect as zero, allowing for a total score range between zero and ten for respondents.

Statistical Analysis

In the preliminary analysis phase, qualitative data was collected, especially at the needs analysis stage through initial observation activities. This phase utilized an inductive approach to construct the analysis from basic observations. Quantitative data analysis was conducted univariately to determine the percentage or level of the problem or indicator identified. This analysis, derived from both students and midwives providing services, aimed to evaluate data gathered during the needs analysis stage through descriptive statistics, narrating, and interpreting the necessity for practical solutions based on the problems identified.

During the prototype development phase, expert validation was presented qualitatively. In the one-on-one trial phase, qualitative analysis techniques, notably the spiral method, were applied to identify product weaknesses and deficiencies.

In the small group testing phase, qualitative data underwent scrutiny to enhance product quality, complemented by statistical analysis of quantitative data from questionnaires and observations.

For the field test, data was described in terms of frequency distribution, and a t-test was employed to determine the causal relationship between the use of the product and its impact. Data analysis was done using SPSS version 24.

Findings

This research was conducted at three health centers in Makassar: Public Health Center (PHC) Kassi-Kassi, Tamalate, and Panambungan, structured into three main phases: module development, implementation, and evaluation. Here is a summary of each phase along with the research outcomes:

Research Module Development

In the initial stage, the module development method utilized was the Research and Development (R&D) approach. This development process encompassed the following stages:

A. Analysis

The needs analysis stage involved conducting a literature study, encompassing journal reviews and adhering to literature review guidelines.

B. Design

The module's design was implemented through the editor under the supervision of the material expert. This module comprised a single module package. Upon completion of this module, students and midwives were anticipated to achieve the following objectives:

1) Knowing the concept of the continuum of care

2) Knowing the care provided in the continuum of care concept

3) Conducting continuum of care

4) Perform documentation for the continuum of care

Furthermore, the module content material was collected and test items were developed to measure the user's ability.

C. Development

1) Module media creation

The development of the module was executed utilizing the Bookcreator application, overseen by editor Ridho. This module encompasses sections such as the cover, title page, table of contents, preface, content, conclusion, questionnaire, and bibliography.

2) Validation of module feasibility

a) Material expert validation

The material expert validation questionnaires involved sending modules and validation questionnaires to two experts. The results of the material expert validation were based on responses provided by these two experts with expertise in midwifery.

Table 1 showcases the results from the material expert review of the two materials, highlighting that the developed CoC module is rated as "very good" in terms of quality and feasibility. This rating is supported by the average percentage across four evaluated aspects of the module, documented at 3.50±0.39.

Table 1. Results of material expert validation

b) Media expert validation

Table 2 reveals the feedback from two media experts, indicating that the overall quality and feasibility of the developed CoC module are considered "very good". This evaluation is reflected in the average percentage across three dimensions of the module, noted at 3.21±0.30.

Table 2. Results of media expert validation

Implementation

Implementation was carried out on a small sample trial with 15 professional students, yielding the following results:

Table 3 summarizes the feedback from 15 small sample users, specifically students, demonstrating that the developed CoC module was assessed as "very good" in terms of overall quality and feasibility evidenced by the average score for the module's components, which is 3.53±0.87.

Table 3. Analysis of small sample trial results

Evaluation

To assess the effectiveness of the maternal health module, the presentation of data included both pretest and posttest results for 30 pregnant women, showcasing the improvement following the module's implementation.

The average knowledge score prior to the module trial stood at 67.08, but after the trial, it increased to 89.14. This significant rise in knowledge scores, by 22.06 points before and after the educational intervention, underscores the effectiveness of the CoC module in improving student knowledge. A paired t-test resulted in a p-value of 0.002, signifying a statistically significant improvement.

Discussion

CoC in midwifery represents an ongoing, holistic approach to providing services that span pregnancy, childbirth, the postpartum period, newborn care, and family planning, specifically designed to cater to the unique health requirements and personal situations of each individual [4, 8].

The essence of the CoC model emphasizes fostering conditions for natural childbirth, with the goal of assisting women in giving birth with minimal medical interventions while attentively caring for their physical, psychological, spiritual, and social health, as well as that of their families [16]. This model integrates a comprehensive suite of services during pregnancy, labor, and the postpartum period, providing women with tailored information and support. Despite these ideals, a notable challenge remains: many midwives offer fragmented services, which can lead to the delayed identification of emergency complications in the postnatal period [26].

The objective of this research was to create a viable midwifery service model that covers pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum, newborn care, and family planning. The findings demonstrate that the newly developed model substantially improved the knowledge of both students and practicing midwives regarding the CoC model, as confirmed by test results with a p-value<0.05. The adoption of the CoC approach requires students to administer midwifery care that is centered around the needs of pregnant women, adhering to the principles of both CoC and comprehensive care. By providing this continuous, all-encompassing, woman-focused care, students are able to form a deeper connection with their patients, acknowledging the varied needs of each one, which ultimately leads to personalized care plans.

A study from Norway by Aune et al. [20] underscored the positive impact of implementing CoC on student midwives' knowledge within the midwifery discipline. CoC facilitates enduring relationships between student midwives and women, fostering mutual trust and encouraging personal growth. This dynamic enables students to appreciate the importance of personalized, holistic care and to understand the comprehensive duties of a midwife.

The educational approach adopted incorporates modules across three cycles: the first cycle addresses midwifery care during pregnancy; the second focuses on care during labor; and the third cycle is dedicated to postpartum midwifery care. Each cycle includes four phases and features collaborative meetings involving students, academic lecturers, and practicing midwives. These sessions act as a forum for evaluating clinical competencies (ANC, intranatal care, postnatal care) and discussing case studies [2, 5, 27]. Furthermore, students are allocated a CoC caseload, which requires them to accompany a client from the prenatal stage through childbirth to the postnatal phase. This engagement provides students with a continuous learning journey in midwifery care, culminating in the production of a detailed client report and a logbook of care activities. Through this process, students acquire hands-on experience in providing consistent care, reflective of midwifery principles, and are presented with numerous opportunities to refine their clinical skills through each client interaction [6, 10].

Participants in this study expressed positive feedback about their experiences acting as midwives within the CoC framework, particularly emphasizing the development of close bonds with their clients through the consistent delivery of midwifery care [12, 18]. The opportunity to support clients and their families endowed students with a sense of purpose, which in turn, enhanced their self-esteem. Through their involvement in the ongoing provision of midwifery care, students reported an increased confidence in their caregiving abilities. This aligns with existing research, which suggests that relational learning can significantly improve students' clinical skills and bolster their confidence as healthcare providers [28].

This study's limitations include its small sample size and the restriction of its participant pool to students from a single university, leading to a lack of diversity among participants. For a more comprehensive validation of the educational model developed through this module, future research should aim to include larger and more varied sample sizes.

Conclusion

Implementing the CoC educational module is effective in improving participants' understanding of the factors contributing to the delayed recognition of emergency complications, especially in the postnatal phase.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: The study was performed in accordance with the ethical considerations of the Helsinki Declaration. This study obtained ethical feasibility under the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health, Makassar (726/KEPK-PTKMKS/VII/2022).

Conflicts of Interests: Nothing declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: Mukarramah S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/ (60%); Amdadi ZA (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: None declared.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Technology of Health Education

Received: 2023/11/25 | Accepted: 2023/12/30 | Published: 2024/01/29

Received: 2023/11/25 | Accepted: 2023/12/30 | Published: 2024/01/29

References

1. Lestari PP, Wati DP. Implementation of sustainable midwise care (continuity of care midwifery) in work area Gadang Puskesmas only Banjarmasin city. Jurnal Kajian Ilmiah Kesehatan Dan Teknologi. 2021;3(1):23-9. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.52674/jkikt.v3i1.40]

2. Forster DA, McLachlan HL, Davey MA, Biro MA, Farrell T, Gold L, et al. Continuity of care by a primary midwife (caseload midwifery) increases women's satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care: Results from the COSMOS randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:28. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-016-0798-y]

3. Sandall J. Midwives' burnout and continuity of care. Br J Midwifery. 1997;5(2):106-11. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjom.1997.5.2.106]

4. Homer C, Brodie P, Sandall J, Leap N. Midwifery continuity of care. 2nd ed. Chatswood: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019. [Link]

5. Bowers J, Cheyne H, Mould G, Page M. Continuity of care in community midwifery. Health Care Manag Sci. 2015;18(2):195-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10729-014-9285-z]

6. Perriman N, Davis DL, Ferguson S. What women value in the midwifery continuity of care model: A systematic review with meta-synthesis. Midwifery. 2018;62:220-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2018.04.011]

7. Mansyur N, Dahlan K. Textbook of midwifery care during the postpartum period. Batam: Selaksa Media; 2014. [Indonesian] [Link]

8. Homer CSE. Models of maternity care: Evidence for midwifery continuity of care. Med J Aust. 2016;205(8):370-4. [Link] [DOI:10.5694/mja16.00844]

9. Gulliford M, Naithani S, Morgan M. What is' continuity of care'?. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(4):248-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1258/135581906778476490]

10. Turienzo CF, Roe Y, Rayment-Jones H, Kennedy A, Forster D, Homer CSE, et al. Implementation of midwifery continuity of care models for indigenous women in Australia: Perspectives and reflections for the United Kingdom. Midwifery. 2019;69:110-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2018.11.005]

11. Fitri FJ. Continuity of care midwifery care at the main medical clinic in Sidoarjo. Jurnal Kebidanan. 2020;9(2):34-43. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.47560/keb.v9i2.248]

12. Carter AG, Wilkes E, Gamble J, Sidebotham M, Creedy DK. Midwifery students' experiences of an innovative clinical placement model embedded within midwifery continuity of care in Australia. Midwifery. 2015;31(8):765-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2015.04.006]

13. Gray J, Taylor J, Newton M. Embedding continuity of care experiences: An innovation in midwifery education. Midwifery. 2016;33:40-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2015.11.014]

14. Yani LY, Yanti AD. Implementation of "continuity of care" by final year midwifery students. Prosiding Conference on Research and Community Services. 2019;1(1):955-60. [Indonesian] [Link]

15. Marmi. Midwifery care during the antenatal period. 3rd ed. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar; 2017. [Indonesian] [Link]

16. McLachlan HL, Newton M, McLardie-Hore FE, McCalman P, Jackomos M, Bundle G, et al. Translating evidence into practice: Implementing culturally safe continuity of midwifery care for First Nations women in three maternity services in Victoria, Australia. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101415. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101415]

17. Aune I, Dahlberg U, Ingebrigtsen O. Relational continuity as a model of care in practical midwifery studies. Br J Midwifery. 2011;19(8):515-23. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjom.2011.19.8.515]

18. Aune I, Holsether OV, Kristensen AMT. Midwifery care based on a precautionary approach: Promoting normal births in maternity wards: The thoughts and experiences of midwives. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:132-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.005]

19. Bustami LES, Insani AA, Yulizawati Y, Halida EM, Andriani F. The influence of continuity of care (CoC) in postpartum midwifery care on the tendency to postpartum depression in Lusiana postpartum mothers. 2-Trik: Tunas-Tunas Riset Kesehatan. 2019;9(1):32-7. [Indonesian] [Link]

20. Aune I, Tysland T, Amalie Vollheim S. Norwegian midwives' experiences of relational continuity of midwifery care in the primary healthcare service: A qualitative descriptive study. Nord J Nurs Res. 2021;41(1):5-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2057158520973202]

21. McInnes RJ, Aitken-Arbuckle A, Lake S, Hollins Martin C, MacArthur J. Implementing continuity of midwife carer-just a friendly face? A realist evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:304. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-020-05159-9]

22. Creswell JW. Steps in conducting a scholarly mixed methods study [Presentation]. DBER Speaker Series; 2013 [cited November 14, 2013]. Available from: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dberspeakers/48/ [Link]

23. Rusdi M. Educational treatment-based research. Depok: Rajawali Pers; 2020. [Indonesian] [Link]

24. Dick W, Carey L, Carey J. The systematic design of instruction. 8th ed. London: Pearson; 2014. [Link]

25. Masturoh I, Anggita N. Health research methodology. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta; 2018. [Indonesian] [Link]

26. Lewis P, Fry J, Rawnson S. Student midwife caseloading-a new approach to midwifery education. Br J Midwifery. 2008;16(8):499-502. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjom.2008.16.8.30782]

27. Dahlberg U, Aune I. The woman's birth experience-The effect of interpersonal relationships and continuity of care. Midwifery. 2013;29(4):407-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2012.09.006]

28. Rawnson S, Fry J, Lewis P. Student caseloading: Embedding the concept within education. Br J Midwifery. 2008;16(10):636-41. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjom.2008.16.10.31231]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |