Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 25-29 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ateilah K, Aboussaleh Y, Bikri S. Anthropometric Evaluation of Nutritional Status in Urban Adolescents of Northwestern Morocco. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :25-29

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72640-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72640-en.html

1- Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco

2- Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra 14000, Morocco. Postal Code: 133 (samir.bikri@uit.ac.ma)

2- Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra 14000, Morocco. Postal Code: 133 (samir.bikri@uit.ac.ma)

Full-Text [PDF 581 kb]

(2897 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1586 Views)

Full-Text: (231 Views)

Introduction

In order to optimize the impact of interventions focused on advancing health through dietary care or the implementation of food and nutrition policies, it is essential to gain insights into the nutritional status of the individual or the specific population under consideration [1]. The nutritional intake during adolescence plays a vital role in an individual's overall well-being. A balanced diet is essential to fulfill the body's nutritional needs and sustain fundamental physiological processes. Poor nutrition can manifest as either an excess of calories or a deficiency in one or more essential nutrients. Anthropometry stands out as a valuable tool, essential for gauging the nutritional well-being of populations, particularly among children in developing regions [2]. Recognizing the pivotal role of nutritional status as a key indicator, it becomes a critical measure for the overall health and well-being of children worldwide [3]. Currently, one of the paramount health challenges faced by developing nations is the pervasive issue of malnutrition [4]. Addressing this concern is not just a matter of health but also a fundamental step toward fostering the well-being and future potential of communities. By understanding and actively responding to nutritional needs, we can work together to pave the way for healthier, thriving societies.

The 2011 National Anthropometry Survey (NAS) in Morocco indicated a noteworthy reduction in the prevalence of underweight among children under five years old. The rate declined from 14.8% in 1987 to 9.3% in 2004 and further dropped to 3.1% in 2011, affecting a total of 89,000 children. This figure stands notably lower than the global average of 16% and the 18% reported in developing countries between 2006 and 2010 [5]. In addition, stunting also decreased, from 28.6% in 1987 to 18.1% in 2004 and further to 16.5% in 2011, affecting a total of 474,000 children. This rate is significantly below the global average of 27% and the 29% observed in developing countries [5].

The prevalence of wasting, characterized by a weight deficit relative to height, decreased from 10.2% in 2004 to 3% in 2011, a figure significantly lower than the average in developing countries, where it stood at 10% [5]. For adults aged 20 and over, the prevalence of thinness decreased from 3.9% in 2001 to 3.3% in 2011, with variations in urban areas (from 3.5% to 3.1%) and rural areas (from 4.4% to 3.8%). At the same time, the incidence of overweight increased over the decade (2001-2011), rising from 27% to 32.9% (from 29.2% to 34.9% in urban areas, from 24.1% to 29.5% in rural areas). Regarding obesity, it affects 17.9% of the population, with higher rates in urban areas (21.2%) compared to rural areas (12.6%) [6].

However, it is important to note that the NAS did not consider the intermediate age groups (10 to 20 years) due to the absence of international reference standards [7]. On the other hand, although the World Health Organization (WHO) includes the age group of 10 to 19 years in the adolescence category, this period has been less studied in terms of the use and interpretation of anthropometry in the health field. Since the prevalence of malnutrition is considerably lower in adolescence than in early childhood, the need for anthropometric data seemed less urgent [8]. However, the study of this period of rapid changes remains both important and challenging [9], remaining poorly documented [10].

To our knowledge, few studies have addressed the issue of malnutrition among Moroccan adolescents. This study aimed to assess different forms of malnutrition and highlight the relationship between nutritional status and the socio-economic conditions of adolescents at Idris Premier High School in the urban commune of Kenitra in Northwestern Morocco.

Instrument and Methods

Participants

This descriptive cross-sectional study was done during the academic year 2019-2020 in the Idris Premier High School in the urban municipality of Kenitra, situated in Northwestern Morocco. The research sample was high school students enrolled in the scientific core curriculum (n=243), of whom 55.96% were female (n=136), 44.03% were male (n=107), and the average age was 16.07±1 years.

To meet the goals of this study, we crafted a questionnaire addressing sociodemographic and socio-economic attributes of the child (age, gender, household size, parents' professions, parents' educational levels, and student activities). For validity, we carefully designed the questions to ensure that they represent what we want to measure. Additionally, we had experts in the field review them for relevance. Regarding the reliability, we tested the questionnaire with a small group of people at two different times to check the consistency of their answers. Based on these criteria, we are confident in the quality of our questionnaire.

Anthropometric Measurements

The adolescent's weight was gauged using a reliable mechanical scale with 0.5kg precision. Height was documented in cm using a stadiometer precise to 0.1cm, with birth dates cross-verified against official documents (birth certificates). Anthropometric measurements were taken in indoor attire, excluding shoes, following the standardized guidelines of the WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) [9, 11-12]. These measurements contribute to the assessment of malnutrition through anthropometric indices (height-for-age and body mass index (BMI)). Height-for-age and BMI-for-age were determined using Z-scores calculated by Epi Info 2000 [13]. Stunting and thinness were defined as Z-scores<-2 for height-for-age and BMI-for-age, respectively. The indicator for the risk of overweight was specified as Z-score >+1 and ≤+2, and that of obesity was defined as Z-score>+2 [14].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were performed using percentages for the qualitative variables and means ± standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables. The Chi-square test was used to identify the relationships among variables. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Findings

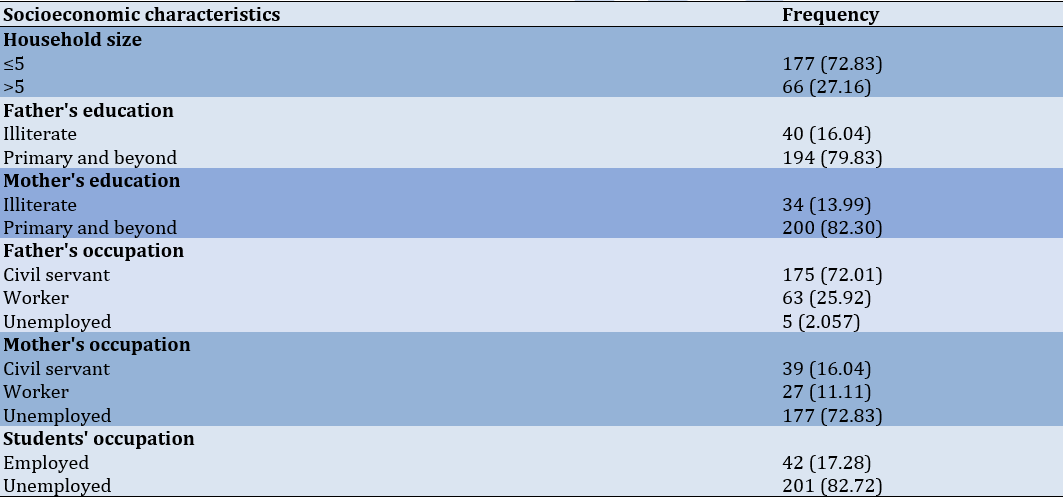

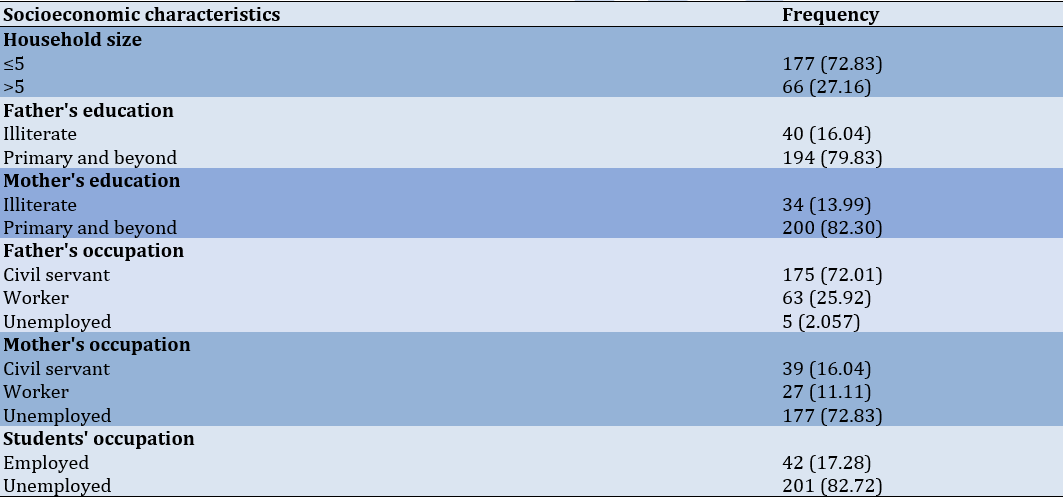

72.83% of students came from households with five or fewer members, while 27.16% had more than five members (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency (numbers in parentheses are %) of socioeconomic characteristics of the studied population (n=243)

The average weight was 52.63±8.81kg, and the mean height was 161.01±11.11cm. The average Z-score (-1.31±1.11) for height-for-age indicated a slight growth delay, while the Z-score (-0.79±1.13) for underweight suggested a slight underweight condition. Stunting was observed in 12.75% of the subjects, while underweight affected only 3.7%. The prevalence of structural growth insufficiency was significantly more pronounced in boys than in girls (p=0.039), and it increased with age for both sexes (p=0.037). There was no significant difference in underweight between boys and girls, regardless of age (p>0.05).

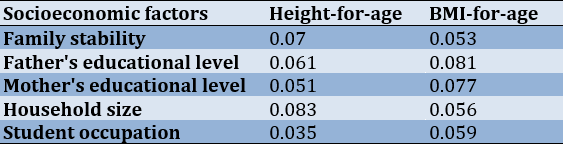

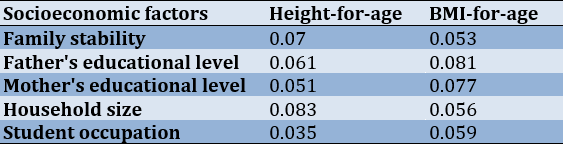

The Chi-square test revealed significant associations between socioeconomic factors and growth indicators, such as height-for-age and BMI-for-age. Regarding family stability, although it showed no significant association with height-for-age (p=0.07), it exhibited a significant association with BMI-for-age (p=0.035). Concerning parental education, the father's educational level showed a trend toward association with height-for-age (p=0.061) but had no significant association with BMI-for-age (p=0.081). On the other hand, the mother's educational level showed a trend toward association with both height-for-age (p=0.051) and BMI-for-age (p=0.077). Additionally, household size and student activity do not show a significant association with either height-for-age or BMI-for-age (Table 2).

Table 2. P-values of the relationships between socioeconomic factors and growth indicators (height-for-age and BMI-for-age)

Discussion

In the present study, conducted in the urban environment of Kenitra, Morocco, the studied population consists of 243 high school students from Idriss I High School. Among them, 55.96% were female (n=136) and 44.03% were male (n=107), with an average age of 16.07±1 years, ranging from 14 to 19 years.

Regarding the average education level of parents, the majority had a high level of education (primary and above): 79.83% for fathers' education level and 82.30% for mothers' education level. However, 16.04% of fathers had an illiterate or preschool or Quranic education level, while 13.99% of mothers had a very low level of education (illiterate or preschool or Quranic level). In terms of household size, 27.16% of students came from households with five or fewer members, while another 27.16% of students had households with more than five members. Approximately 17.28% of surveyed students are forced to work during their free time, often for very low wages, which raises concerns about their health. In our study, 12.75% of students suffered from stunting, 3.7% of high school students were affected by thinness, and obesity was rare.

Insufficient stature in children tends to increase with age in both sexes, a trend also observed by [15] in a study conducted in a rural school in the city of Kenitra, Morocco. Stunting in adolescents begins very early, around the age of 3, reflecting early malnutrition. The transition to family meals is not always beneficial for the child, and dietary diversification is associated with children's growth [16]. These results support the conclusions of the literature, which indicate that growth retardation tends to increase with age in children. Possible explanations include the lack of adequate complementary infant feeding, both in terms of quantity and quality.

Thinness can be caused by a multitude of factors, including prenatal malnutrition, deficiencies in micro and macronutrients, infections, as well as a lack of attention and care from household members [17]. The causes of these malnutritions can be multiple, whether they are of genetic, metabolic, or environmental origin [18]. Dietary diversification, environmental cleanliness, physical and economic accessibility to food, access to clean water, parental education, and socio-economic status, as well as the activity of growth hormones in individuals and the genetics of the population, all appear to be complementary or determining factors for the health of the child during this period.

In this study, boys exhibit a higher prevalence of malnutrition compared to girls, a trend that could be attributed to genetic factors, such as certain boys having a shorter stature, or hormonal issues, particularly related to growth hormones. It's worth noting that pubertal development varies between boys and girls of the same age [19].

The established literature consistently highlights the connection between malnutrition and socioeconomic status [20-24]. However, research on the socioeconomic and environmental factors influencing malnutrition among adolescents in Morocco is limited.

In this predominantly constituted group of individuals with modest socio-educational backgrounds, the prevalence of illiteracy among parents stands at 30.04%. The socio-professional landscape within this demographic is similarly modest. The outcomes of the Chi-square test of independence reveal a lack of dependence between certain socioeconomic variables, specifically the educational attainment of both parents, the occupational roles of the father and mother, household size, and nutritional indices (height-for-age and BMI). Contrary to findings in other studies indicating a relationship between parental occupations and the nutritional well-being of their offspring [25], our results reveal a statistically significant lack of interdependence between individuals' stature-weight status and these socioeconomic factors. This discrepancy may be attributed to the nuanced socio-economic disparities in urban settings, where factors such as education, parental roles, household size, and birth order do not exert as deterministic an influence. The literature substantiates connections between environmental conditions and anthropometric variables across diverse populations [26-28]. The present study findings highlight the intricate connections between socioeconomic factors and growth indicators, emphasizing the potential impact of family stability and parental education on the nutritional status of adolescents.

Widespread malnutrition is observed among individuals with limited financial means, insufficient access to potable water, and inadequate health education [29]. Adolescents with low to moderate socio-economic status encounter barriers to consistent food access due to financial constraints, compounded by cohabitation with multiple individuals within the same household [30, 31].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged:

Firstly, the study's scope is limited to a specific high school and urban commune in Kenitra, Northwestern Morocco. Therefore, caution must be exercised when attempting to generalize the findings to more diverse populations.

Secondly, the cross-sectional design used in the study prevents the establishment of causal relationships and a comprehensive understanding of temporal variations in nutritional patterns.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data collected through questionnaires introduces the possibility of response biases. This means that the accuracy of the information may be influenced by how participants perceive and report their own nutritional status.

Furthermore, the study primarily focuses on anthropometric indices, potentially overlooking other critical factors that can influence nutritional status, such as dietary habits and micronutrient intake.

The study also has temporal constraints and does not consider external factors, including cultural influences and access to healthcare, which can play significant roles in shaping nutritional outcomes.

These limitations underscore the need for future research endeavors with broader scopes and more diverse methodologies to provide a more nuanced perspective on the complex interplay between socioeconomic conditions and adolescent nutritional status.

Conclusion

Adolescents, particularly boys, with an average age of 16.07 years, are significantly affected by stunting and thinness compared to girls. However, it is important to note that these conclusions are constrained by the geographical scope of the survey. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive study with expanded geographical coverage is necessary to generalize these results more effectively.

Acknowledgments: Nothing to be reported.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco. All participants provided a written informed consent form at enrollment and were informed of the objective of the research as well as anonymity.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors affirm that the study was carried out without any potential conflicts of interest arising from commercial or financial relationships.

Authors’ Contribution: Ateilah K (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (34%); Aboussaleh Y (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (34%); Bikri S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (32%)

Funding/Supports: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or profit sectors.

In order to optimize the impact of interventions focused on advancing health through dietary care or the implementation of food and nutrition policies, it is essential to gain insights into the nutritional status of the individual or the specific population under consideration [1]. The nutritional intake during adolescence plays a vital role in an individual's overall well-being. A balanced diet is essential to fulfill the body's nutritional needs and sustain fundamental physiological processes. Poor nutrition can manifest as either an excess of calories or a deficiency in one or more essential nutrients. Anthropometry stands out as a valuable tool, essential for gauging the nutritional well-being of populations, particularly among children in developing regions [2]. Recognizing the pivotal role of nutritional status as a key indicator, it becomes a critical measure for the overall health and well-being of children worldwide [3]. Currently, one of the paramount health challenges faced by developing nations is the pervasive issue of malnutrition [4]. Addressing this concern is not just a matter of health but also a fundamental step toward fostering the well-being and future potential of communities. By understanding and actively responding to nutritional needs, we can work together to pave the way for healthier, thriving societies.

The 2011 National Anthropometry Survey (NAS) in Morocco indicated a noteworthy reduction in the prevalence of underweight among children under five years old. The rate declined from 14.8% in 1987 to 9.3% in 2004 and further dropped to 3.1% in 2011, affecting a total of 89,000 children. This figure stands notably lower than the global average of 16% and the 18% reported in developing countries between 2006 and 2010 [5]. In addition, stunting also decreased, from 28.6% in 1987 to 18.1% in 2004 and further to 16.5% in 2011, affecting a total of 474,000 children. This rate is significantly below the global average of 27% and the 29% observed in developing countries [5].

The prevalence of wasting, characterized by a weight deficit relative to height, decreased from 10.2% in 2004 to 3% in 2011, a figure significantly lower than the average in developing countries, where it stood at 10% [5]. For adults aged 20 and over, the prevalence of thinness decreased from 3.9% in 2001 to 3.3% in 2011, with variations in urban areas (from 3.5% to 3.1%) and rural areas (from 4.4% to 3.8%). At the same time, the incidence of overweight increased over the decade (2001-2011), rising from 27% to 32.9% (from 29.2% to 34.9% in urban areas, from 24.1% to 29.5% in rural areas). Regarding obesity, it affects 17.9% of the population, with higher rates in urban areas (21.2%) compared to rural areas (12.6%) [6].

However, it is important to note that the NAS did not consider the intermediate age groups (10 to 20 years) due to the absence of international reference standards [7]. On the other hand, although the World Health Organization (WHO) includes the age group of 10 to 19 years in the adolescence category, this period has been less studied in terms of the use and interpretation of anthropometry in the health field. Since the prevalence of malnutrition is considerably lower in adolescence than in early childhood, the need for anthropometric data seemed less urgent [8]. However, the study of this period of rapid changes remains both important and challenging [9], remaining poorly documented [10].

To our knowledge, few studies have addressed the issue of malnutrition among Moroccan adolescents. This study aimed to assess different forms of malnutrition and highlight the relationship between nutritional status and the socio-economic conditions of adolescents at Idris Premier High School in the urban commune of Kenitra in Northwestern Morocco.

Instrument and Methods

Participants

This descriptive cross-sectional study was done during the academic year 2019-2020 in the Idris Premier High School in the urban municipality of Kenitra, situated in Northwestern Morocco. The research sample was high school students enrolled in the scientific core curriculum (n=243), of whom 55.96% were female (n=136), 44.03% were male (n=107), and the average age was 16.07±1 years.

To meet the goals of this study, we crafted a questionnaire addressing sociodemographic and socio-economic attributes of the child (age, gender, household size, parents' professions, parents' educational levels, and student activities). For validity, we carefully designed the questions to ensure that they represent what we want to measure. Additionally, we had experts in the field review them for relevance. Regarding the reliability, we tested the questionnaire with a small group of people at two different times to check the consistency of their answers. Based on these criteria, we are confident in the quality of our questionnaire.

Anthropometric Measurements

The adolescent's weight was gauged using a reliable mechanical scale with 0.5kg precision. Height was documented in cm using a stadiometer precise to 0.1cm, with birth dates cross-verified against official documents (birth certificates). Anthropometric measurements were taken in indoor attire, excluding shoes, following the standardized guidelines of the WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) [9, 11-12]. These measurements contribute to the assessment of malnutrition through anthropometric indices (height-for-age and body mass index (BMI)). Height-for-age and BMI-for-age were determined using Z-scores calculated by Epi Info 2000 [13]. Stunting and thinness were defined as Z-scores<-2 for height-for-age and BMI-for-age, respectively. The indicator for the risk of overweight was specified as Z-score >+1 and ≤+2, and that of obesity was defined as Z-score>+2 [14].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were performed using percentages for the qualitative variables and means ± standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables. The Chi-square test was used to identify the relationships among variables. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Findings

72.83% of students came from households with five or fewer members, while 27.16% had more than five members (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency (numbers in parentheses are %) of socioeconomic characteristics of the studied population (n=243)

The average weight was 52.63±8.81kg, and the mean height was 161.01±11.11cm. The average Z-score (-1.31±1.11) for height-for-age indicated a slight growth delay, while the Z-score (-0.79±1.13) for underweight suggested a slight underweight condition. Stunting was observed in 12.75% of the subjects, while underweight affected only 3.7%. The prevalence of structural growth insufficiency was significantly more pronounced in boys than in girls (p=0.039), and it increased with age for both sexes (p=0.037). There was no significant difference in underweight between boys and girls, regardless of age (p>0.05).

The Chi-square test revealed significant associations between socioeconomic factors and growth indicators, such as height-for-age and BMI-for-age. Regarding family stability, although it showed no significant association with height-for-age (p=0.07), it exhibited a significant association with BMI-for-age (p=0.035). Concerning parental education, the father's educational level showed a trend toward association with height-for-age (p=0.061) but had no significant association with BMI-for-age (p=0.081). On the other hand, the mother's educational level showed a trend toward association with both height-for-age (p=0.051) and BMI-for-age (p=0.077). Additionally, household size and student activity do not show a significant association with either height-for-age or BMI-for-age (Table 2).

Table 2. P-values of the relationships between socioeconomic factors and growth indicators (height-for-age and BMI-for-age)

Discussion

In the present study, conducted in the urban environment of Kenitra, Morocco, the studied population consists of 243 high school students from Idriss I High School. Among them, 55.96% were female (n=136) and 44.03% were male (n=107), with an average age of 16.07±1 years, ranging from 14 to 19 years.

Regarding the average education level of parents, the majority had a high level of education (primary and above): 79.83% for fathers' education level and 82.30% for mothers' education level. However, 16.04% of fathers had an illiterate or preschool or Quranic education level, while 13.99% of mothers had a very low level of education (illiterate or preschool or Quranic level). In terms of household size, 27.16% of students came from households with five or fewer members, while another 27.16% of students had households with more than five members. Approximately 17.28% of surveyed students are forced to work during their free time, often for very low wages, which raises concerns about their health. In our study, 12.75% of students suffered from stunting, 3.7% of high school students were affected by thinness, and obesity was rare.

Insufficient stature in children tends to increase with age in both sexes, a trend also observed by [15] in a study conducted in a rural school in the city of Kenitra, Morocco. Stunting in adolescents begins very early, around the age of 3, reflecting early malnutrition. The transition to family meals is not always beneficial for the child, and dietary diversification is associated with children's growth [16]. These results support the conclusions of the literature, which indicate that growth retardation tends to increase with age in children. Possible explanations include the lack of adequate complementary infant feeding, both in terms of quantity and quality.

Thinness can be caused by a multitude of factors, including prenatal malnutrition, deficiencies in micro and macronutrients, infections, as well as a lack of attention and care from household members [17]. The causes of these malnutritions can be multiple, whether they are of genetic, metabolic, or environmental origin [18]. Dietary diversification, environmental cleanliness, physical and economic accessibility to food, access to clean water, parental education, and socio-economic status, as well as the activity of growth hormones in individuals and the genetics of the population, all appear to be complementary or determining factors for the health of the child during this period.

In this study, boys exhibit a higher prevalence of malnutrition compared to girls, a trend that could be attributed to genetic factors, such as certain boys having a shorter stature, or hormonal issues, particularly related to growth hormones. It's worth noting that pubertal development varies between boys and girls of the same age [19].

The established literature consistently highlights the connection between malnutrition and socioeconomic status [20-24]. However, research on the socioeconomic and environmental factors influencing malnutrition among adolescents in Morocco is limited.

In this predominantly constituted group of individuals with modest socio-educational backgrounds, the prevalence of illiteracy among parents stands at 30.04%. The socio-professional landscape within this demographic is similarly modest. The outcomes of the Chi-square test of independence reveal a lack of dependence between certain socioeconomic variables, specifically the educational attainment of both parents, the occupational roles of the father and mother, household size, and nutritional indices (height-for-age and BMI). Contrary to findings in other studies indicating a relationship between parental occupations and the nutritional well-being of their offspring [25], our results reveal a statistically significant lack of interdependence between individuals' stature-weight status and these socioeconomic factors. This discrepancy may be attributed to the nuanced socio-economic disparities in urban settings, where factors such as education, parental roles, household size, and birth order do not exert as deterministic an influence. The literature substantiates connections between environmental conditions and anthropometric variables across diverse populations [26-28]. The present study findings highlight the intricate connections between socioeconomic factors and growth indicators, emphasizing the potential impact of family stability and parental education on the nutritional status of adolescents.

Widespread malnutrition is observed among individuals with limited financial means, insufficient access to potable water, and inadequate health education [29]. Adolescents with low to moderate socio-economic status encounter barriers to consistent food access due to financial constraints, compounded by cohabitation with multiple individuals within the same household [30, 31].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged:

Firstly, the study's scope is limited to a specific high school and urban commune in Kenitra, Northwestern Morocco. Therefore, caution must be exercised when attempting to generalize the findings to more diverse populations.

Secondly, the cross-sectional design used in the study prevents the establishment of causal relationships and a comprehensive understanding of temporal variations in nutritional patterns.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data collected through questionnaires introduces the possibility of response biases. This means that the accuracy of the information may be influenced by how participants perceive and report their own nutritional status.

Furthermore, the study primarily focuses on anthropometric indices, potentially overlooking other critical factors that can influence nutritional status, such as dietary habits and micronutrient intake.

The study also has temporal constraints and does not consider external factors, including cultural influences and access to healthcare, which can play significant roles in shaping nutritional outcomes.

These limitations underscore the need for future research endeavors with broader scopes and more diverse methodologies to provide a more nuanced perspective on the complex interplay between socioeconomic conditions and adolescent nutritional status.

Conclusion

Adolescents, particularly boys, with an average age of 16.07 years, are significantly affected by stunting and thinness compared to girls. However, it is important to note that these conclusions are constrained by the geographical scope of the survey. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive study with expanded geographical coverage is necessary to generalize these results more effectively.

Acknowledgments: Nothing to be reported.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco. All participants provided a written informed consent form at enrollment and were informed of the objective of the research as well as anonymity.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors affirm that the study was carried out without any potential conflicts of interest arising from commercial or financial relationships.

Authors’ Contribution: Ateilah K (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (34%); Aboussaleh Y (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (34%); Bikri S (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (32%)

Funding/Supports: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or profit sectors.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Healthy Life Style

Received: 2023/11/25 | Accepted: 2023/12/30 | Published: 2024/01/26

Received: 2023/11/25 | Accepted: 2023/12/30 | Published: 2024/01/26

References

1. Shrivastava S, Shrivastava P, Ramasamy J. Assessment of nutritional status in the community and clinical settings. J Med Sci. 2014;34(5):211-3. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1011-4564.143648]

2. Hakeem R, Shaikh AH, Asar F. Assessment of linear growth of affluent urban Pakistani adolescents according to CDC 2000 references. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31(3):282-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03014460310001658800]

3. de Onis M, Frongillo EA, Blössner M. Is malnutrition declining? An analysis of changes in levels of child malnutrition since 1980. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(10):1222-33. [Link]

4. Haaga J, Kenrick C, Test K, Mason J. An estimate of the prevalence of child malnutrition in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1985;38(3):331-47. [Link]

5. Unicef. The State of the World's Children 2012: Children in an Urban World. New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2012. [Link]

6. Douidich M, Ezzrari A, Ikira D, Louafi, C. Key findings from the National Anthropometric Survey 2011. Rabat: CND (National Documentation Center); 2013. [Link]

7. HCP. National Anthropometric Survey. Rabat: High Commission for Planning (HCP); 2011. [Link]

8. WHO Working Group. Use and interpretation of anthropometric indicators of nutritional status. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64(6):929-41. [Link]

9. World Health Organization. Use and interpretation of anthropometry: Report of a WHO expert committee. Geneva; WHO 1995. [Link]

10. Dorlencourt F, Priem V, Legros D. Anthropometric indices used for the diagnosis of malnutrition in adolescents and adults: A review of the literature. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2000;93(5):321-4. [Link]

11. Lohman TG, Roche AF, Mart orell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Chicago: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. [Link]

12. World Health Organization. measurement of changes in nutritional status: A guide for the assessment of the nutritional impact of supplementary feeding programs for vulnerable groups. Geneva: WHO; 1983. [Link]

13. Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Zubieta J. Epi Info, 2000: A Database and Statistics Program for Public Health Professionals Using Windows 95, NT and 2000 Computers. Georgia: CDC Home; 2000. [Link]

14. De Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660-7. [Link] [DOI:10.2471/BLT.07.043497]

15. El Hioui M, Soualem A, Ahami AOT, Aboussaleh Y, Rusinek S, Dik K. Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Characteristics in Relation to Academic Performance in a Rural School in the City of Kenitra, Morocco. Antropo. 2008;17:25-33. [Link]

16. Aboussaleh Y, Ahami A, Alaoui L. Stature-weight nutritional status of pre-adolescent schoolchildren in the city and regions of Kenitra, Morocco. Médecine du Maghreb. 2007;145:21-9. [Link]

17. SCN. Nutrtion for the school aged child. California: United Nations; 1998. [Link]

18. Johnston FE, Wainer H, Thissen D, Vean Mac R. Hereditary and environmental determinants of growth in height in a longitudinal sample of children and youth of Guatemalan and European ancestry. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1976;44(3):469-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ajpa.1330440310]

19. Sbaibi R, Aboussaleh Y. Exploratory study of the stature-weight status of middle school children in the rural commune of Sidi El Kamel in Northwestern Morocco. Antropo. 2011;24:61-6. [Link]

20. Abudayya A, Thoresen M, Abed Y, Holmboe-Ottesen G. Overweight,stunting, and anemia are public health problems among low socioeconomic. Strip Nutr Res. 2007;27:762-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nutres.2007.09.017]

21. Bisai S, Bose K, Ghosh A. Nutritional status of Lodha children in a village of Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal. Indian J Public Health. 2008;52:203-6. [Link]

22. Goodwin DK, Knol LK, Eddy JM, Fitzhugh EC, Kendrick O, Donohue RE. Sociodemographic correlates of overall quality of dietary. Nutr Res. 2006;26:105-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nutres.2006.02.004]

23. Zere E, McIntyre E. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in SouthAfrica. Int J Equity Health. 2003;2(1):7. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1475-9276-2-7]

24. Samir B, Hsaini A, Lababneh T, Louragli I, Benmhammed H, Touhami Ahami AO, Aboussaleh Y. Predicting visual perception and working memory deficits among patients with type 1 diabetes: The implication of eating attitude and mental health status. Acta Neuropsychologica. 2021;19(4):501-19. [Link] [DOI:10.5604/01.3001.0015.6228]

25. Jain NB, Laden F, Guller U, Shankar A, Kazani S, Garshick E. Relation between blood lead levels and childhood anemia in India. Am J Epidemiol2005. 2005;161(10):968-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/aje/kwi126]

26. Bogin В, Macvean RВ. Growth in height and weight of urban Guatemalan primary school children of high and low socioeconomic class. Hum.Biol. 1978(50):477-87. [Link]

27. Bogin В, & Macvean RВ. The relationship of socioeconomic status and sex to body size, skeletal maturation, and cognitive status of Guatemalan City schoolchildren. Child Development. 1983;(54):115-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb00340.x]

28. Rona RJ, Chinn S. National study of health and growth: social and biological factors associated with height of children from ethnic groups living in England. Ann Hum BioL. 1986;13(5):453-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03014468600008631]

29. World Health Organization. Turning the tide of malnutrition: responding to the challenge of the 21st century. Geneva: WHO; 2000. [Link]

30. Dapi LN, Janlert U, Nouedoui C, Stenlund H, Håglin L. Socioeconomic and gender differences in adolescents' nutritional status in urban Cameroon. Africa Nutr Res. 2009;29(5):313-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.002]

31. Dapi NL, Omoloko C, Janlert U, Dahlgren L, Håglin L. "I eat to be happy, to be strong and to live". Perceptions of rural and urban adolescents in Cameroon, Africa. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(6):320-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.03.001]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |