Volume 12, Issue 1 (2024)

Health Educ Health Promot 2024, 12(1): 53-58 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Negara C, Sukartini T, Setiya D, Nursalam N. Effectiveness of Diabetes Self-Management Education on Non-Ulcer Diabetic Foot Incidents. Health Educ Health Promot 2024; 12 (1) :53-58

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72239-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-72239-en.html

1- Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 643 kb]

(2991 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1706 Views)

Full-Text: (143 Views)

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcers are chronic complications of diabetes mellitus that arise as a consequence of neuropathy. They typically originate from non-diabetic foot problems, including deformities, reduced sensitivity, callus formation, and dry skin on the feet. In 2022, at Banjarmasin Hospital, 3830 diabetic patients were reported, among whom 23.6% experienced diabetic foot issues. These problems are primarily located on the tiptoes (50%), the plantar metatarsal region (30-40%), the dorsal aspect of the foot (10-15%), the heel (5-10%), and in 10% of cases, multiple ulcers are present.

Elevated blood glucose levels lead to reduced peripheral blood flow or peripheral vascular disease, resulting in inadequate blood supply to the feet and calves. This condition hinders wound healing and increases the risk of infections. Early detection of foot anomalies or injuries is crucial and can be achieved through regular foot examinations and proper foot care. The objective of foot care is to prevent or mitigate foot problems. The therapeutic approach to diabetic foot issues is based on two main principles: prevention and rehabilitation. Preventive measures include patient education, meticulous foot care, exercises, and the use of appropriate diabetic footwear. Rehabilitation aims to restore functional ambulation.

One strategy to prevent the development of non-ulcerated diabetic foot conditions is to educate individuals with diabetes mellitus about diabetic foot care, which serves as the cornerstone of diabetes management [1]. Education is the primary approach for diabetic patients, empowering them to expand their knowledge and skills to undertake preventive measures throughout their lives, thus averting the progression to type 2 diabetes over time [2].

Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is a form of comprehensive education that has been shown to enhance clinical outcomes and improve the quality of life for diabetic patients [3]. DSME plays a crucial role in diabetes care and is essential for initiatives aimed at enhancing patients' overall health status. It involves an ongoing process to empower diabetic patients with the knowledge, skills, and capabilities to engage in effective self-care practices [4]. Through DSME, patients learn to independently implement self-care techniques to enhance diabetes control, prevent complications, and enhance their quality of life [5].

In diabetes management, achieving near-normal blood glucose levels is paramount for preventing long-term complications. Adequate self-management behavior (SMB) plays a vital role in achieving this goal and serves as a cornerstone in diabetes therapy. Key aspects of SMB, regardless of diabetes type, include lifestyle modifications such as meal planning, regular self-examination of the feet, and, if necessary, self-monitoring of blood or urine glucose levels, as well as appropriate medication adherence [6]. The Banjarmasin Health Service projected that there would be 23,806 cases of diabetes in 2021. By 2022, the number of diabetes cases from 25 public health centers is expected to reach 25,000. Among these centers, the Banjarmasin Community Health Center stands out, with a predicted increase of 1,224 cases in 2022, making it one of the health centers in Banjar Regency with the highest number of diabetes cases detected. However, control over diabetes management among these 1,224 individuals is uneven. The Banjarmasin Health Center relies on traditional education methods and has yet to incorporate the DSME approach into its diabetic foot care program. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of DSME implementation at the Banjarmasin Health Center in reducing the prevalence of non-ulcer diabetic foot complications.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This research was quasi-experimental with a nonequivalent control group.

Participants

A sample of 230 participants was divided into two groups: 115 respondents in the intervention group and 115 respondents in the control group. Consecutive sampling was utilized as the sampling technique. The participants included in this study were diabetes mellitus patients residing in the catchment area of the Banjarmasin Health Center who met the following inclusion criteria: 1) Age over 30 years, 2) Diagnosed with diabetes mellitus for more than one year, and 3) Adequate communication skills. The sample size was determined using the sample size formula for nominal data, with parameters Zα=1.96, α=0.05, p=0.5, and Q=0.5, resulting in a sample size of 115 participants.

Instruments and Measures

The instrument utilized in this research was the Diabetes Self-Care Activities Foot Care Questionnaire, adapted from the Australasian Podiatry Council, which assesses various aspects of foot care, including skin condition, toenail health, foot shape, and identification of foot problems. After participants expressed their willingness to participate, data collection commenced with the administration of the research questionnaire to assess self-care foot care practices and diabetic foot examination. Following data collection, the intervention group received DSME intervention. The educational sessions were conducted as follows: Week one involved a lecture and demonstration focusing on diabetic foot problems, followed by interactive discussions, conclusions, and closing remarks. Week two emphasized foot care practices, with the intervention group provided with a foot care set to facilitate immediate practice after counseling. Week three focused on physical activities, including diabetic foot exercises. Week four addressed medication management, particularly in the context of treating diabetic foot problems. Post-test assessments were conducted using the same instrument after the completion of the DSME intervention. The control group received an informational leaflet following the post-test data collection.

Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire used in this study was originally developed and validated for research in Indonesia by Ismonah (2008), with a validity value of ≥0.361 and a reliability of 0.847. Therefore, this instrument was deemed suitable for use in the current study.

Data Analysis

Univariate analysis was conducted on the characteristics of the research respondents. Normality testing was performed using Shapiro-Wilk's formula with a 95% confidence level. Bivariate testing in this study employed parametric tests. Statistical analyses for all tests were conducted at a significance level of 95% (α=0.05). Pre- and post-measurements in both the intervention and control groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test if the data distribution was abnormal and the paired T-Test for normally distributed data. Meanwhile, for the analysis of post-test scores between the intervention and control groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed data. This research was conducted from March to August 2022 at Banjarmasin Hospital, South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Data were analyzed using SPSS 28 software.

Findings

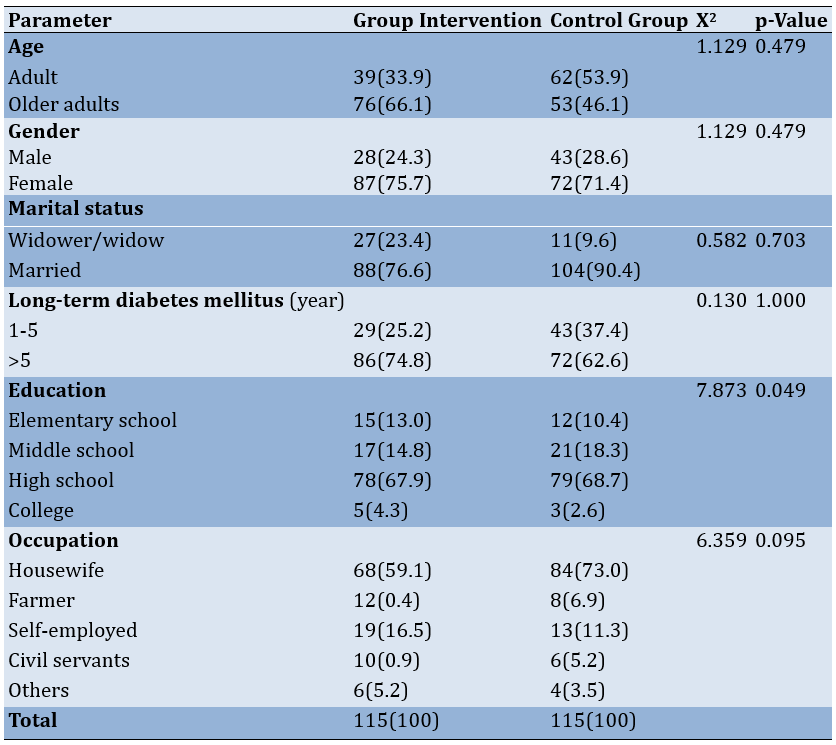

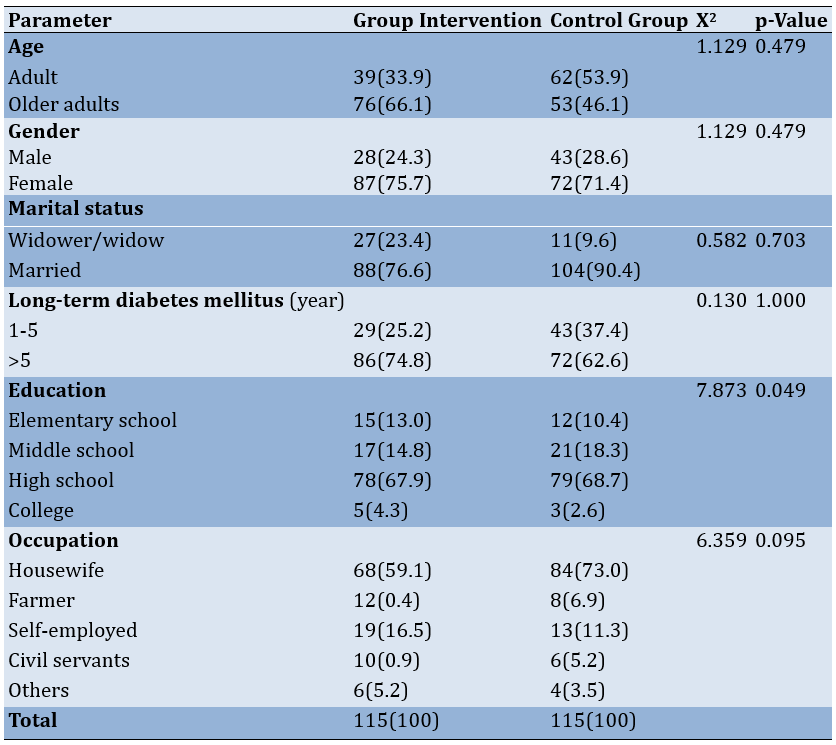

According to Table 1, the majority of individuals in the intervention group were older adults, comprising 76 people (66.1%), while in the control group, 53 (46.1%) were elderly. The predominant gender in the intervention group was female, with 87 participants (75.7%), compared to 72 (71.4%) in the control group. In terms of marital status, the intervention group had the highest number of married individuals, with 88 (76.6%), whereas in the control group, the majority were also married, totaling 104 (90.4%). Among those suffering from diabetes mellitus, the majority in the intervention group had been afflicted for over 5 years, accounting for 86 participants (74.8%), while in the control group, there were 72 (62.6%) individuals with diabetes for over 5 years. Regarding educational attainment, the highest level achieved in the intervention group was high school, with 78 participants (67.9%), whereas in the control group, the majority had completed upper secondary education, totaling 79 (68.7%). As for occupation, most individuals in the intervention group were homemakers, comprising 68 participants (59.1%), while in the control group, the majority also worked as homemakers, totaling 84 (73.0%).

Table 1. Frequency and Homogeneity Test Analysis Characteristics Respondents in Group (n=230)

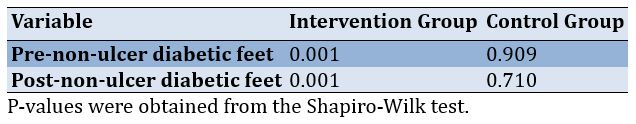

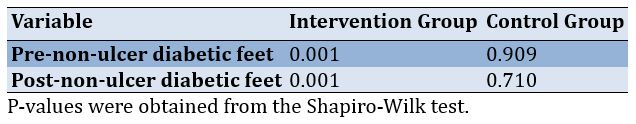

Table 2 demonstrates that the normality test results for the control group's data were within the expected range. However, it is noteworthy that the data for the intervention group's scale, with a Shapiro-Wilk p-value of <α 0.05, was unexpected.

Table 2. Normality test of the groups

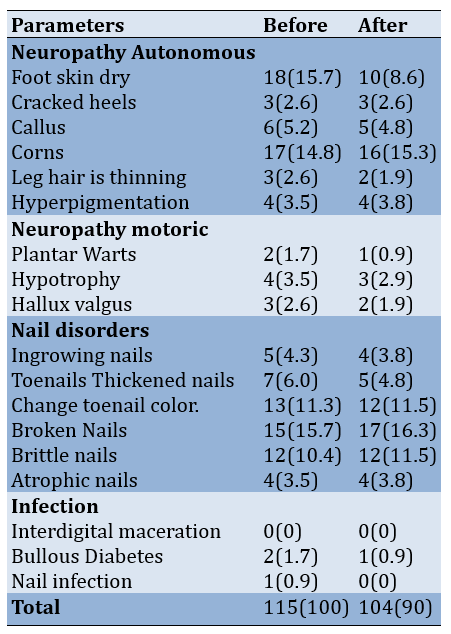

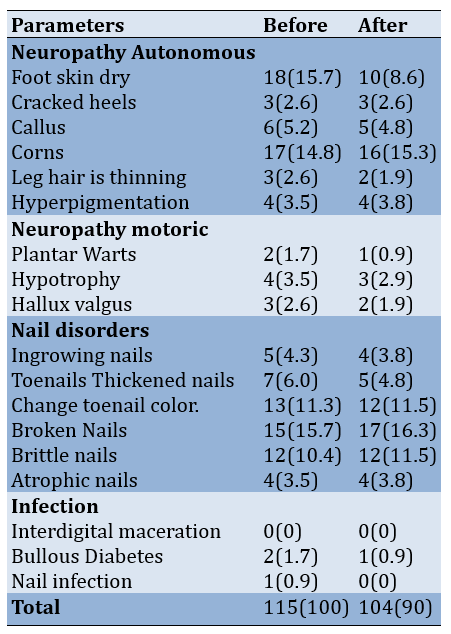

Referring to Table 3, before DSME, the intervention group experienced dry feet most frequently, with 18 individuals (15.7%), followed by corns in 17 individuals (14.8%), changes in toenail color in 15 individuals (10.4%), and thickened nails in 13 individuals (11.3%). Following the intervention, the highest occurrences were toenail discoloration at 17 individuals (16.3%), corns at 16 individuals (15.3%), and damaged nails at 17 individuals (16.3%).

Table 3. Before and after DSME, the distribution frequency of non-ulcer diabetes episodes in the intervention group

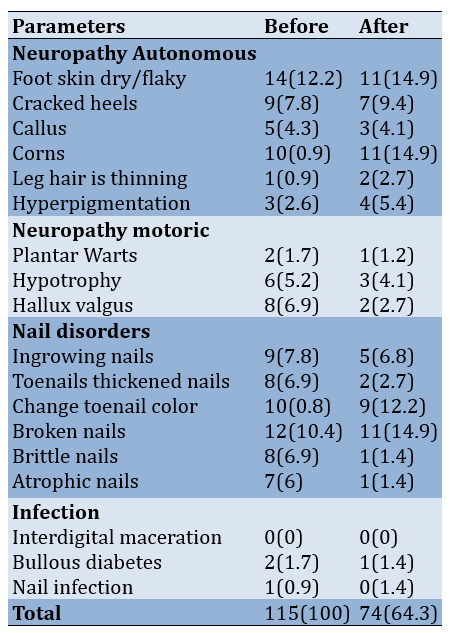

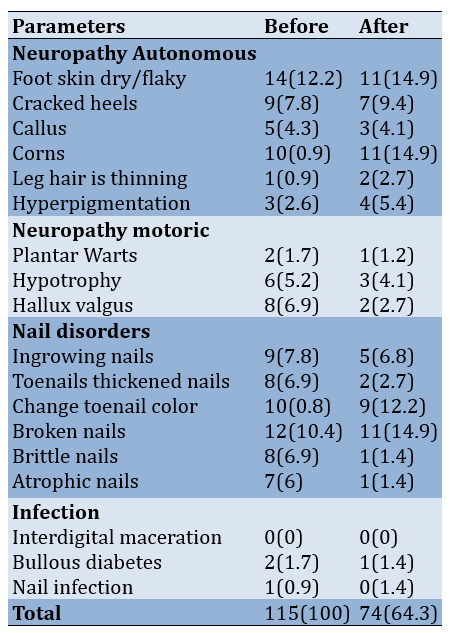

Regarding Table 4, before DSME, the control group had the highest prevalence of dry foot skin, with 14 individuals (12.2%), followed by broken nails in 12 individuals (10.4%), corns in 10 individuals (8.9%), and toenail discoloration in 10 individuals (8.8%). After DSME in the control group, dry foot skin remained the most prevalent in 11 individuals (14.9%), followed by corns in 11 individuals (14.9%) and damaged nails in 11 individuals (14.9%).

Table 4. Frequency of non-ulcerated diabetic foot events in the control group before and after diabetes self-management education

Discussion

Respondents in the intervention group experienced a decreased incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic feet after treatment. Ninety-seven respondents received DSME intervention. Eighteen respondents experienced an increased incidence of non-ulcer diabetic feet, while 8 experienced conditions that remained the same as before DSME. This indicates a difference in non-ulcer diabetic foot incidents before and after DSME. Meanwhile, in the control group, the average incidence of non-ulcer diabetic feet before treatment was 4.69, and after treatment, it was 4.25. The minimum-maximum value of the intervention group before treatment ranged from 1 to 9, and after treatment, it ranged from 1 to 5. This indicates that there are no differences in the incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic feet before and after treatment.

This research supports previous studies [7], indicating that a focused educational program for 2 hours effectively prevents diabetic foot ulcers in at-risk patients. The approach used in the demonstration [8] is practical and aimed at improving skills, not just knowledge. This strategy aligns with the approach taken by researchers, providing material through lectures, simulations, and demonstrations regarding the examination and treatment of diabetic feet. DSME aims to change people's or society's behavior from unhealthy to healthy [9]. Patients with a sufficient understanding of DM can change their outlook and way of life, leading to changes in their behavior [10]. Factors such as breed, gender, age, duration of DM, education, and employment can influence behavior change. Most participants in the intervention group are older (60-74). Age affects a person's capacity for self-care [11, 12]. Filipino American women under 65 should routinely wash their feet, and those over 65 require the best assistance to care for their feet [13]. In the intervention group, most had DM for over five years. Long-term DM patients have the opportunity to learn about health issues, empowering them to take care of themselves.

Women comprise the majority of the gender type in this study. In previous studies [14], the majority of respondents in the intervention group were women, who tended to be more diligent and skilled in foot care practices. Most individuals in the intervention group had received education up to the middle school level, indicating that higher levels of education could increasingly influence decisions regarding foot care [15]. Furthermore, a significant portion of the intervention group was engaged in occupations related to an IRT (information, communication, and technology) field, whereas in another study [16], most respondents in the intervention group were not employed. The nature of certain professions encourages self-care practices and provides individuals with a structured physical activity routine, enhancing their overall experience and understanding. Access to affordable information can also influence behavior positively [17].

The objective of health education utilizing the DSME method is to enhance individuals' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to foot care, improve compliance, enhance quality of life, and empower families, specific groups, communities, and individuals in need to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles actively in order to achieve optimal health outcomes [18]. Behavior change is influenced by various factors, including amplifiers, facilitators, and predispositions (such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, etc.). Other factors such as goals, support from peers, available information, personal circumstances, and potential scenarios may also impact behavior [19].

Table 6 shows a statistically significant difference in the mean incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic feet following treatment: 11.69 in the intervention group compared to 21.31 in the control group. Thus, it can be inferred that there are differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of the incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic foot, as Ha is accepted while H0 is rejected. Through the DSME technique, health education on diabetic foot care equips respondents with the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively care for their feet.

Only 19% of the individuals in this study who did not have diabetic foot ulcers fell into the wrong group for regular visual foot assessment. Based on the outcomes of statistical analyses, a significant correlation exists between the frequency of diabetic foot ulcers and regular visual examination of the feet. This indicates that diabetic foot ulcers are more likely to develop more significantly in patients with diabetes mellitus if their feet are not visually examined [7, 27].

Health education also plays a role in reducing the occurrence of diabetic foot problems following therapy. An independent, low-cost method for preventing foot issues such as diabetic ulcers is to self-inspect your feet daily [22]. Toenail cutting is one of the nail care practices that contribute to preventing diabetic foot ulcers. When their nails are clipped, 71.43% of diabetic patients with diabetic foot ulcers fall into the incorrect category [23, 28]. Statistical testing has observed a significant correlation between the incidence of diabetic foot ulcers and the practice of nail trimming. Some evaluation criteria include using lotion on hands and body, bathing feet in warm water, trimming nails, and treating calluses [24, 29]. Health education aims to change respondents' behavior toward healthy behavior to build a healthy society, and this study naturally supports that premise [25]. This study shows that the goals of the DSME are to assist in decision-making, provide problem-solving skills, promote self-care, and actively collaborate with the healthcare team to improve clinical outcomes, health, and quality of life [26]. The limitations of this research included the lack of time of the participant, their conditions that they could not be followed until the end of this research, and the limited activity of the participants due to their disease.

Conclusion

DSME lowers the prevalence of non-ulcer diabetic feet and considerably improves the ability of diabetic patients to provide autonomous and skilled foot care.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Airlangga University and Universitas Lambung Mangkurat for supporting this research until its completion.

Ethical Permissions: After reviewing the process, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Nursing Faculty of Airlangga University in Indonesia gave the procedure ethical clearance (Number: 1903-KEPK).

Conflicts of Interests: There were no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Candra Kusuma Negara CKN (First Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer /Main Researcher (40%); Tintin Sukartini TS (Second author) Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Yulis Setiya Dewi YSD (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Results Writer (20%), Nursalam N (Fourth author) Assistant Researcher/Methods Writer (10% )

Funding/Support: Thanks to Badan Amil Zakat Nasional (BAZNAS) for funding this research.

Diabetic foot ulcers are chronic complications of diabetes mellitus that arise as a consequence of neuropathy. They typically originate from non-diabetic foot problems, including deformities, reduced sensitivity, callus formation, and dry skin on the feet. In 2022, at Banjarmasin Hospital, 3830 diabetic patients were reported, among whom 23.6% experienced diabetic foot issues. These problems are primarily located on the tiptoes (50%), the plantar metatarsal region (30-40%), the dorsal aspect of the foot (10-15%), the heel (5-10%), and in 10% of cases, multiple ulcers are present.

Elevated blood glucose levels lead to reduced peripheral blood flow or peripheral vascular disease, resulting in inadequate blood supply to the feet and calves. This condition hinders wound healing and increases the risk of infections. Early detection of foot anomalies or injuries is crucial and can be achieved through regular foot examinations and proper foot care. The objective of foot care is to prevent or mitigate foot problems. The therapeutic approach to diabetic foot issues is based on two main principles: prevention and rehabilitation. Preventive measures include patient education, meticulous foot care, exercises, and the use of appropriate diabetic footwear. Rehabilitation aims to restore functional ambulation.

One strategy to prevent the development of non-ulcerated diabetic foot conditions is to educate individuals with diabetes mellitus about diabetic foot care, which serves as the cornerstone of diabetes management [1]. Education is the primary approach for diabetic patients, empowering them to expand their knowledge and skills to undertake preventive measures throughout their lives, thus averting the progression to type 2 diabetes over time [2].

Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is a form of comprehensive education that has been shown to enhance clinical outcomes and improve the quality of life for diabetic patients [3]. DSME plays a crucial role in diabetes care and is essential for initiatives aimed at enhancing patients' overall health status. It involves an ongoing process to empower diabetic patients with the knowledge, skills, and capabilities to engage in effective self-care practices [4]. Through DSME, patients learn to independently implement self-care techniques to enhance diabetes control, prevent complications, and enhance their quality of life [5].

In diabetes management, achieving near-normal blood glucose levels is paramount for preventing long-term complications. Adequate self-management behavior (SMB) plays a vital role in achieving this goal and serves as a cornerstone in diabetes therapy. Key aspects of SMB, regardless of diabetes type, include lifestyle modifications such as meal planning, regular self-examination of the feet, and, if necessary, self-monitoring of blood or urine glucose levels, as well as appropriate medication adherence [6]. The Banjarmasin Health Service projected that there would be 23,806 cases of diabetes in 2021. By 2022, the number of diabetes cases from 25 public health centers is expected to reach 25,000. Among these centers, the Banjarmasin Community Health Center stands out, with a predicted increase of 1,224 cases in 2022, making it one of the health centers in Banjar Regency with the highest number of diabetes cases detected. However, control over diabetes management among these 1,224 individuals is uneven. The Banjarmasin Health Center relies on traditional education methods and has yet to incorporate the DSME approach into its diabetic foot care program. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of DSME implementation at the Banjarmasin Health Center in reducing the prevalence of non-ulcer diabetic foot complications.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This research was quasi-experimental with a nonequivalent control group.

Participants

A sample of 230 participants was divided into two groups: 115 respondents in the intervention group and 115 respondents in the control group. Consecutive sampling was utilized as the sampling technique. The participants included in this study were diabetes mellitus patients residing in the catchment area of the Banjarmasin Health Center who met the following inclusion criteria: 1) Age over 30 years, 2) Diagnosed with diabetes mellitus for more than one year, and 3) Adequate communication skills. The sample size was determined using the sample size formula for nominal data, with parameters Zα=1.96, α=0.05, p=0.5, and Q=0.5, resulting in a sample size of 115 participants.

Instruments and Measures

The instrument utilized in this research was the Diabetes Self-Care Activities Foot Care Questionnaire, adapted from the Australasian Podiatry Council, which assesses various aspects of foot care, including skin condition, toenail health, foot shape, and identification of foot problems. After participants expressed their willingness to participate, data collection commenced with the administration of the research questionnaire to assess self-care foot care practices and diabetic foot examination. Following data collection, the intervention group received DSME intervention. The educational sessions were conducted as follows: Week one involved a lecture and demonstration focusing on diabetic foot problems, followed by interactive discussions, conclusions, and closing remarks. Week two emphasized foot care practices, with the intervention group provided with a foot care set to facilitate immediate practice after counseling. Week three focused on physical activities, including diabetic foot exercises. Week four addressed medication management, particularly in the context of treating diabetic foot problems. Post-test assessments were conducted using the same instrument after the completion of the DSME intervention. The control group received an informational leaflet following the post-test data collection.

Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire used in this study was originally developed and validated for research in Indonesia by Ismonah (2008), with a validity value of ≥0.361 and a reliability of 0.847. Therefore, this instrument was deemed suitable for use in the current study.

Data Analysis

Univariate analysis was conducted on the characteristics of the research respondents. Normality testing was performed using Shapiro-Wilk's formula with a 95% confidence level. Bivariate testing in this study employed parametric tests. Statistical analyses for all tests were conducted at a significance level of 95% (α=0.05). Pre- and post-measurements in both the intervention and control groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test if the data distribution was abnormal and the paired T-Test for normally distributed data. Meanwhile, for the analysis of post-test scores between the intervention and control groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed data. This research was conducted from March to August 2022 at Banjarmasin Hospital, South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Data were analyzed using SPSS 28 software.

Findings

According to Table 1, the majority of individuals in the intervention group were older adults, comprising 76 people (66.1%), while in the control group, 53 (46.1%) were elderly. The predominant gender in the intervention group was female, with 87 participants (75.7%), compared to 72 (71.4%) in the control group. In terms of marital status, the intervention group had the highest number of married individuals, with 88 (76.6%), whereas in the control group, the majority were also married, totaling 104 (90.4%). Among those suffering from diabetes mellitus, the majority in the intervention group had been afflicted for over 5 years, accounting for 86 participants (74.8%), while in the control group, there were 72 (62.6%) individuals with diabetes for over 5 years. Regarding educational attainment, the highest level achieved in the intervention group was high school, with 78 participants (67.9%), whereas in the control group, the majority had completed upper secondary education, totaling 79 (68.7%). As for occupation, most individuals in the intervention group were homemakers, comprising 68 participants (59.1%), while in the control group, the majority also worked as homemakers, totaling 84 (73.0%).

Table 1. Frequency and Homogeneity Test Analysis Characteristics Respondents in Group (n=230)

Table 2 demonstrates that the normality test results for the control group's data were within the expected range. However, it is noteworthy that the data for the intervention group's scale, with a Shapiro-Wilk p-value of <α 0.05, was unexpected.

Table 2. Normality test of the groups

Referring to Table 3, before DSME, the intervention group experienced dry feet most frequently, with 18 individuals (15.7%), followed by corns in 17 individuals (14.8%), changes in toenail color in 15 individuals (10.4%), and thickened nails in 13 individuals (11.3%). Following the intervention, the highest occurrences were toenail discoloration at 17 individuals (16.3%), corns at 16 individuals (15.3%), and damaged nails at 17 individuals (16.3%).

Table 3. Before and after DSME, the distribution frequency of non-ulcer diabetes episodes in the intervention group

Regarding Table 4, before DSME, the control group had the highest prevalence of dry foot skin, with 14 individuals (12.2%), followed by broken nails in 12 individuals (10.4%), corns in 10 individuals (8.9%), and toenail discoloration in 10 individuals (8.8%). After DSME in the control group, dry foot skin remained the most prevalent in 11 individuals (14.9%), followed by corns in 11 individuals (14.9%) and damaged nails in 11 individuals (14.9%).

Table 4. Frequency of non-ulcerated diabetic foot events in the control group before and after diabetes self-management education

Discussion

Respondents in the intervention group experienced a decreased incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic feet after treatment. Ninety-seven respondents received DSME intervention. Eighteen respondents experienced an increased incidence of non-ulcer diabetic feet, while 8 experienced conditions that remained the same as before DSME. This indicates a difference in non-ulcer diabetic foot incidents before and after DSME. Meanwhile, in the control group, the average incidence of non-ulcer diabetic feet before treatment was 4.69, and after treatment, it was 4.25. The minimum-maximum value of the intervention group before treatment ranged from 1 to 9, and after treatment, it ranged from 1 to 5. This indicates that there are no differences in the incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic feet before and after treatment.

This research supports previous studies [7], indicating that a focused educational program for 2 hours effectively prevents diabetic foot ulcers in at-risk patients. The approach used in the demonstration [8] is practical and aimed at improving skills, not just knowledge. This strategy aligns with the approach taken by researchers, providing material through lectures, simulations, and demonstrations regarding the examination and treatment of diabetic feet. DSME aims to change people's or society's behavior from unhealthy to healthy [9]. Patients with a sufficient understanding of DM can change their outlook and way of life, leading to changes in their behavior [10]. Factors such as breed, gender, age, duration of DM, education, and employment can influence behavior change. Most participants in the intervention group are older (60-74). Age affects a person's capacity for self-care [11, 12]. Filipino American women under 65 should routinely wash their feet, and those over 65 require the best assistance to care for their feet [13]. In the intervention group, most had DM for over five years. Long-term DM patients have the opportunity to learn about health issues, empowering them to take care of themselves.

Women comprise the majority of the gender type in this study. In previous studies [14], the majority of respondents in the intervention group were women, who tended to be more diligent and skilled in foot care practices. Most individuals in the intervention group had received education up to the middle school level, indicating that higher levels of education could increasingly influence decisions regarding foot care [15]. Furthermore, a significant portion of the intervention group was engaged in occupations related to an IRT (information, communication, and technology) field, whereas in another study [16], most respondents in the intervention group were not employed. The nature of certain professions encourages self-care practices and provides individuals with a structured physical activity routine, enhancing their overall experience and understanding. Access to affordable information can also influence behavior positively [17].

The objective of health education utilizing the DSME method is to enhance individuals' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to foot care, improve compliance, enhance quality of life, and empower families, specific groups, communities, and individuals in need to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles actively in order to achieve optimal health outcomes [18]. Behavior change is influenced by various factors, including amplifiers, facilitators, and predispositions (such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, etc.). Other factors such as goals, support from peers, available information, personal circumstances, and potential scenarios may also impact behavior [19].

Table 6 shows a statistically significant difference in the mean incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic feet following treatment: 11.69 in the intervention group compared to 21.31 in the control group. Thus, it can be inferred that there are differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of the incidence of non-ulcerated diabetic foot, as Ha is accepted while H0 is rejected. Through the DSME technique, health education on diabetic foot care equips respondents with the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively care for their feet.

Only 19% of the individuals in this study who did not have diabetic foot ulcers fell into the wrong group for regular visual foot assessment. Based on the outcomes of statistical analyses, a significant correlation exists between the frequency of diabetic foot ulcers and regular visual examination of the feet. This indicates that diabetic foot ulcers are more likely to develop more significantly in patients with diabetes mellitus if their feet are not visually examined [7, 27].

Health education also plays a role in reducing the occurrence of diabetic foot problems following therapy. An independent, low-cost method for preventing foot issues such as diabetic ulcers is to self-inspect your feet daily [22]. Toenail cutting is one of the nail care practices that contribute to preventing diabetic foot ulcers. When their nails are clipped, 71.43% of diabetic patients with diabetic foot ulcers fall into the incorrect category [23, 28]. Statistical testing has observed a significant correlation between the incidence of diabetic foot ulcers and the practice of nail trimming. Some evaluation criteria include using lotion on hands and body, bathing feet in warm water, trimming nails, and treating calluses [24, 29]. Health education aims to change respondents' behavior toward healthy behavior to build a healthy society, and this study naturally supports that premise [25]. This study shows that the goals of the DSME are to assist in decision-making, provide problem-solving skills, promote self-care, and actively collaborate with the healthcare team to improve clinical outcomes, health, and quality of life [26]. The limitations of this research included the lack of time of the participant, their conditions that they could not be followed until the end of this research, and the limited activity of the participants due to their disease.

Conclusion

DSME lowers the prevalence of non-ulcer diabetic feet and considerably improves the ability of diabetic patients to provide autonomous and skilled foot care.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Airlangga University and Universitas Lambung Mangkurat for supporting this research until its completion.

Ethical Permissions: After reviewing the process, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Nursing Faculty of Airlangga University in Indonesia gave the procedure ethical clearance (Number: 1903-KEPK).

Conflicts of Interests: There were no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Candra Kusuma Negara CKN (First Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer /Main Researcher (40%); Tintin Sukartini TS (Second author) Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (30%); Yulis Setiya Dewi YSD (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Results Writer (20%), Nursalam N (Fourth author) Assistant Researcher/Methods Writer (10% )

Funding/Support: Thanks to Badan Amil Zakat Nasional (BAZNAS) for funding this research.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2023/11/2 | Accepted: 2024/01/11 | Published: 2024/01/20

Received: 2023/11/2 | Accepted: 2024/01/11 | Published: 2024/01/20

References

1. Stanek A, Mosti G, Nematillaevich TS, E Valesky EM, Ručigaj TP, Boucelma M, et al. No more venous ulcers-what more can we do?. J Clin Med. 2023;12(19):6153. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jcm12196153]

2. Alibrahim A, AlRamadhan D, Johny S, Alhashemi M, Alduwaisan H, Al-Hilal M. The effect of structured diabetes self-management education on type 2 diabetes patients attending a primary health center in Kuwait. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;171:108567. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108567]

3. Nooseisai M, Viwattanakulvanid P, Kumar R, Viriyautsahakul N, Baloch GM, Somrongthong R. Effects of diabetes self-management education program on lowering blood glucose level, stress, and quality of life among females with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Thailand. Primary Health Care Res Dev. 2021;22:e46. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1463423621000505]

4. Kartika, Ismuntania, Karmila, Rakhman F. Effectiveness of variations of diabetes self-management education (dsme) on self care behavior in type-2 diabetes mellitus patients in tengku chik ditiro hospital. J Health Promot Behav. 2022;7(1):77-85. [Link] [DOI:10.26911/thejhpb.2021.07.01.08]

5. Mbride M. Effect of diabetes self-management education utilizing short message service among adults [dissertation]. Arizona: Grand canyon university; 2022. [Link]

6. Buro AW, Crowder SL, Rozen E, Stern M, Carson TL. Lifestyle interventions with mind-body or stress-management practices for cancer survivors: A rapid review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3355. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20043355]

7. Bus SA, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Raspovic A, Sacco ICN, et al. Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (iwgdf 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36:e3269. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/dmrr.3269]

8. Tursunovich RI. "Guidelines for designing effective language teaching materials. Am J Res Human Soc Sci. 2022;7:65-70. [Link]

9. Roberts RE. Qualitative interview questions: Guidance for novice researchers. Qual Rep. 2020;25(9):3185-203. [Link] [DOI:10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4640]

10. Schmidt SK, Hemmestad L, MacDonald CS, Langberg H, Valentiner LS. Motivation and barriers to maintaining lifestyle changes in patients with type 2 diabetes after an intensive lifestyle intervention (the u-turn trial): A longitudinal qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7454. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17207454]

11. Guijarro-Ojeda JR, Ruiz-Cecilia R, Cardoso-Pulido MJ, Medina-Sánchez L. Examining the interplay between queerness and teacher wellbeing: A qualitative study based on foreign language teacher trainers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):12208. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182212208]

12. Subhan BA. Examining afro-cultural values in african american women with childhood sexual abuse history: its relationship with therapeutic outcomes. New York: John Jay College Of Criminal Justice; 2020. [Link]

13. Alsaleh FM, AlBassam KS, Alsairafi ZK, Naser AY. Knowledge and practice of foot self-care among patients with diabetes attending primary healthcare centres in kuwait: a cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(6):506-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2021.04.006]

14. Taheri S, Zaghloul H, Chagoury O, Elhadad S, Hayder Ahmed S, El Khatib N, et al. Effect of intensive lifestyle intervention on bodyweight and glycaemia in early type 2 diabetes (Diadem-i): An open-label, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):477-89. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30117-0]

15. von dem Knesebeck O, Barbek R. Public stigma toward fatigue-do social characteristics of affected persons matter? Results from the soma. Soc study. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1213721. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1213721]

16. Alhumaid S, Al Mutair A, Al Alawi Z, Alsuliman M, Ahmed GY, Rabaan AA, et al. Knowledge of infection prevention and control among healthcare workers and factors influencing compliance: A systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10:86 [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13756-021-00957-0]

17. Shim M, Jo HS. What quality factors matter in enhancing the perceived benefits of online health information sites? Application of the updated delone and mclean information systems success model. Int J Med Inform. 2020;137:104093. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104093]

18. Calvo RA, Peters D, Vold K, Ryan RM. Supporting human autonomy in AI systems: A framework for ethical enquiry. Ethics of Digital Well-Being. 2020;140:31-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-50585-1_2]

19. Edmonds M, Manu C, Vas P. The current burden of diabetic foot disease. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;17:88-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcot.2021.01.017]

20. Zhao H, McClure NS, Johnson JA, Soprovich A, Al Sayah F, Eurich DT. A longitudinal study on the association between diabetic foot disease and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(3):280-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcjd.2019.08.008]

21. Silva EQ, Suda EY, Santos DP, Veríssimo JL, Ferreira JSSP, Cruvinel Júnior RH, et al. Effect of an educational booklet for prevention and treatment of foot musculoskeletal dysfunctions in people with diabetic neuropathy: The footcare (FOCA) trial II, a study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:180. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13063-020-4115-8]

22. Lung CW, Wu FL, Liao F, Pu F, Fan Y, Jan YK. Emerging technologies for the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2020;29(2):61-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jtv.2020.03.003]

23. Adeyemi TM, Olatunji TL, Adetunji AE, Rehal S. Knowledge, practice and attitude towards foot ulcers and foot care among adults living with diabetes in tobago: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8021. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18158021]

24. Sakre G, Kishanrao S. Management of diabetic foot ulcer-a case study. Glob J Obesity Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;8(1):1-5. [Link]

25. Liao CH. Evaluating the social marketing success criteria in health promotion: A f-dematel approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6317. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17176317]

26. Binte Aminuddin H, Jiao N, Jiang Y, Hong J, Wang W. Effectiveness of smartphone-based self-management interventions on self-efficacy, self-care activities, health-related quality of life and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;116:103286. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.003]

27. Khademian Z, Kazemi Ara F, Gholamzadeh S. The effect of self care education based on orem's nursing theory on quality of life and self-efficacy in patients with hypertension: A Quasi-experimental study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2020;8(2):140-9. [Link]

28. Association Of Diabetes Care And Education Specialists; Kolb L. An effective model of diabetes care and education: The adces7 self-care behaviors™. Sci Diabetes Self Manag Care. 2021;47(1):30-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0145721720978154]

29. American Association of Diabetes Educators. An effective model of diabetes care and education: revising the aade7 self-care behaviors®. Diabetes Educ. 2020;46(2):139-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0145721719894903]

30. Yuan SLK, Couto LA, Marques AP. Effects of a six-week mobile app versus paper book intervention on quality of life, symptoms, and self-care in patients with fibromyalgia: A randomized parallel trial. Braz J Physical Ther. 2021;25(4):428-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.10.003]

31. CHRISMILASARI, Lucia Andi; NURSERY, Septi Machelia Champaca; NEGARA, Candra Kusuma. Self-efficacy and support from family self-care for individuals with high blood pressure. Jurnal EduHealth, 2024, 15.01: 53-60. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |