Volume 11, Issue 4 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(4): 581-589 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sabaghinejad Z. Factors Predicting Health Literacy and Factors Associated to it; A Systematic Review. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (4) :581-589

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-71328-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-71328-en.html

Department of Medical Library and Information Science, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Keywords: Health Behavior [Mesh], Health Literacy [MeSH], Health Promotion [MeSH], Population Health [MeSH], Social Determinants of Health [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 765 kb]

(3990 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1554 Views)

Full-Text: (743 Views)

Introduction

Health Literacy (HL) is a rapidly growing topic in healthcare. In the past few years, the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution has renovated the creation and sharing of health-related information, and people can live in the flow of health-related information. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health literacy as: ‘The cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to access, understand, and use information in ways that maintain and promote good health” [1]. HL includes a range of critical skills that allow individuals to empower themselves to promote health behaviors. Individual and social behavior can be changed towards a healthy lifestyle. This is recognized as shared health responsibility, which is significantly associated with HL.

Low Health Literacy (LHL) is recognized as a global problem that can result in difficulty reading and understanding health information, lower medication compliance, higher rates of hospitalization, and 1.5 to 3 times greater poor health status [2]. Healthcare professionals may not recognize factors associated with HL and may not be sufficiently aware of their impact on health outcomes. LHL can lead to failure to acquire or correctly understand health information. It will have negative impacts on individual’s health and can lead to health disparities. So, it is crucial to identify the factors related to HL. It can help to better understand HL and improve health status and quality of life. Although the effects of HL have been widely studied, only a few have investigated the factors associated with HL.

Environmental, political and social factors can determine health. They include a wide range of skills that people acquire throughout their lives to search for, evaluate, and use health information. They can use the right information to make better decisions, reduce health risks, and improve quality of life. These skills can be influenced by cultural beliefs, understanding of the health system, and health information. Health literacy skills are essential as contemporary health care systems, and people are commonly expected to make the best decisions regarding health care.

This study aimed to review the articles related to health literacy in the last 20 years and explain the factors associated with health literacy or predict it.

Information and Methods

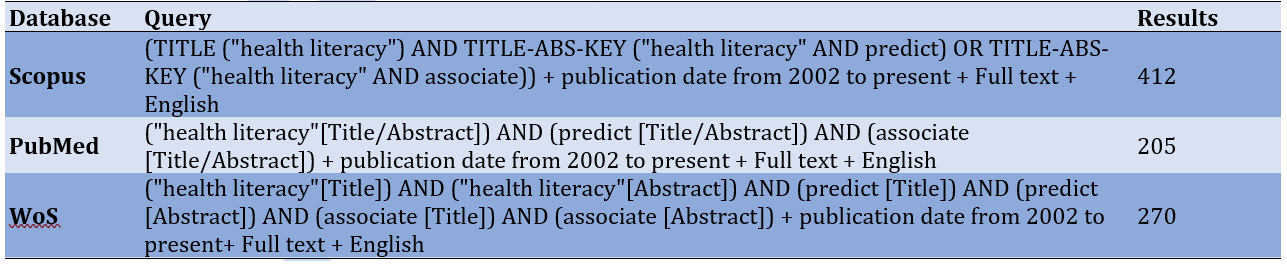

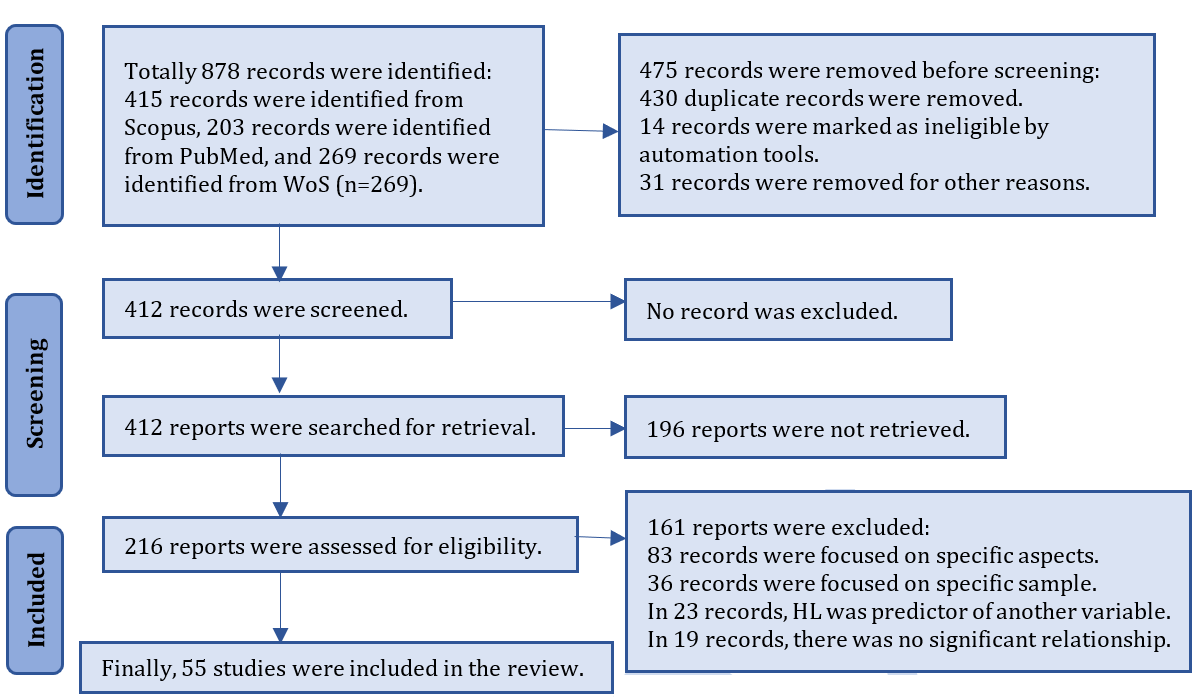

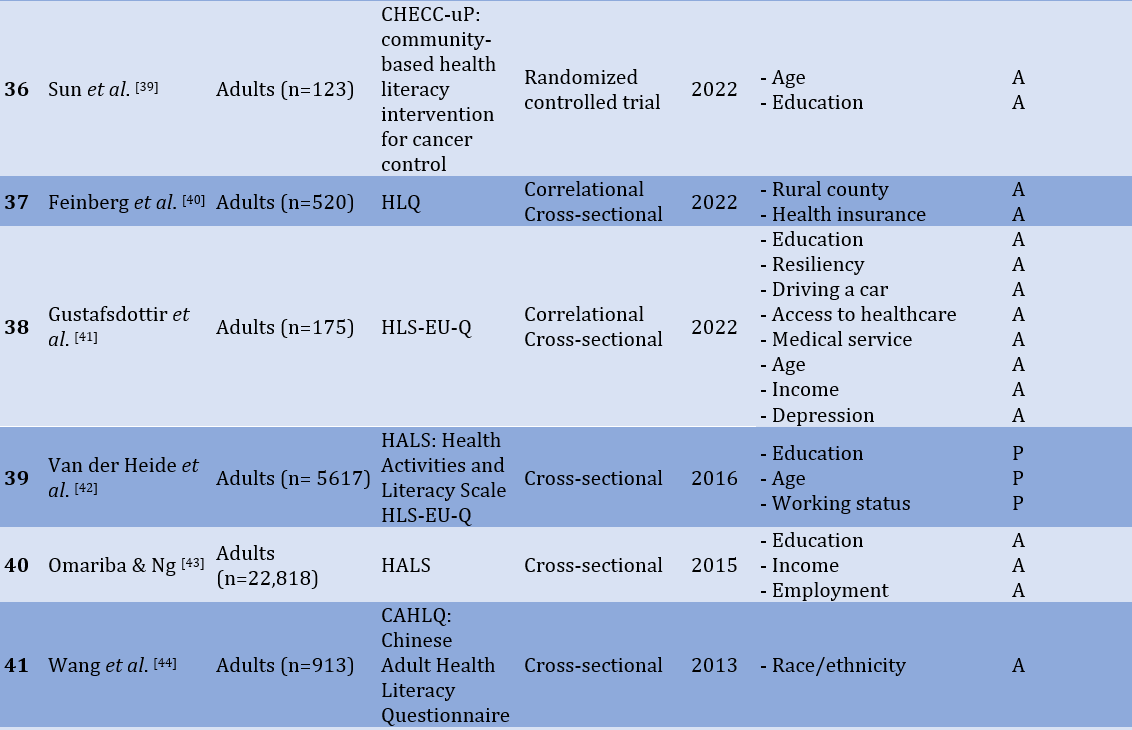

This systematic review examined quantitative research articles published from 2002 to 2022 to explore factors that predict or are associated with HL. Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science (WoS) databases were searched. Table 1 shows the search reports in all databases and the number of retrieved records.

Table 1) Database search construction

The inclusion criteria were:

1. Research articles

2. Quantitative method

3. Focusing on factors that can predict HL or associate with it

4. English full-text is available.

5. Focusing on adults in sampling

6. Publication date between 2002 to 2023

The exclusion criteria were:

1. Articles that focused on specific aspects of HL (e.g., oral HL, media HL).

2. Articles that focused on specific sample (e.g., nurses, immigrants, women).

3. Articles that HL was a predictor of other variables.

4. Articles with no significant relation

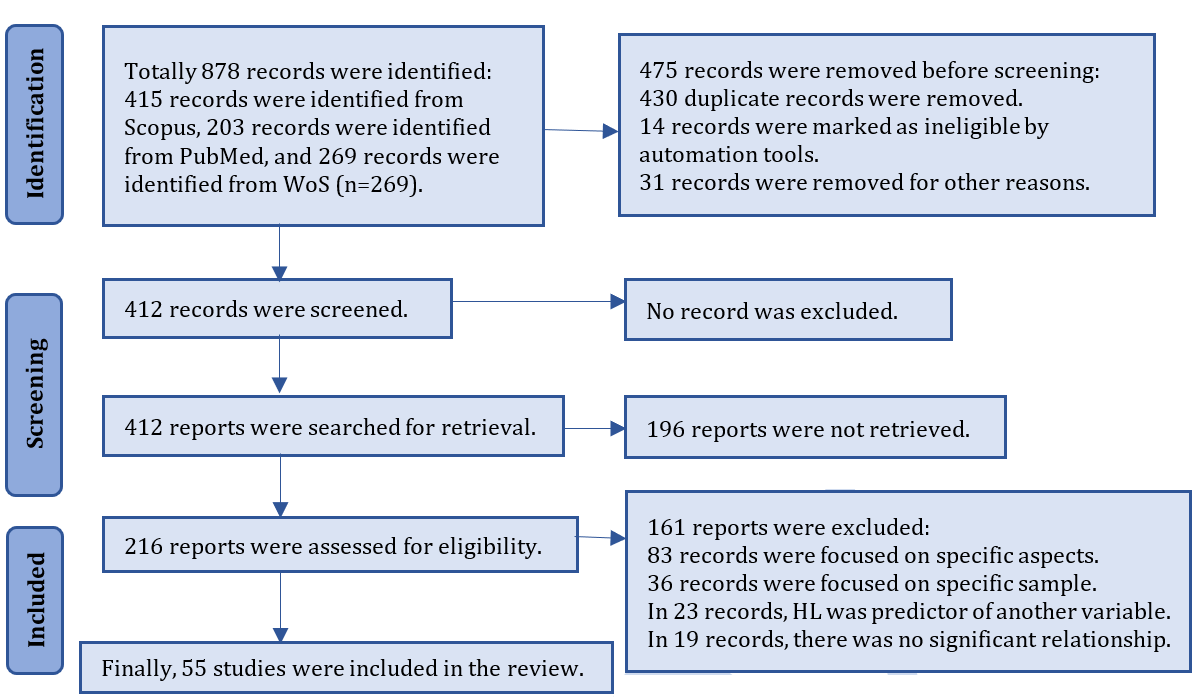

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses framework (PRISMA) [3] was used to conduct a transparent process. Figure 1 shows the final item reporting process.

Figure 1) PRISMA flow chart for new systematic reviews

The role of factors (prediction or association) was determined based on the most repeated. For example, race/ethnicity role was predictor in 7 articles and association in 5 articles. So, it was considered as a predictor. The most frequent factors had a prediction role.

Findings

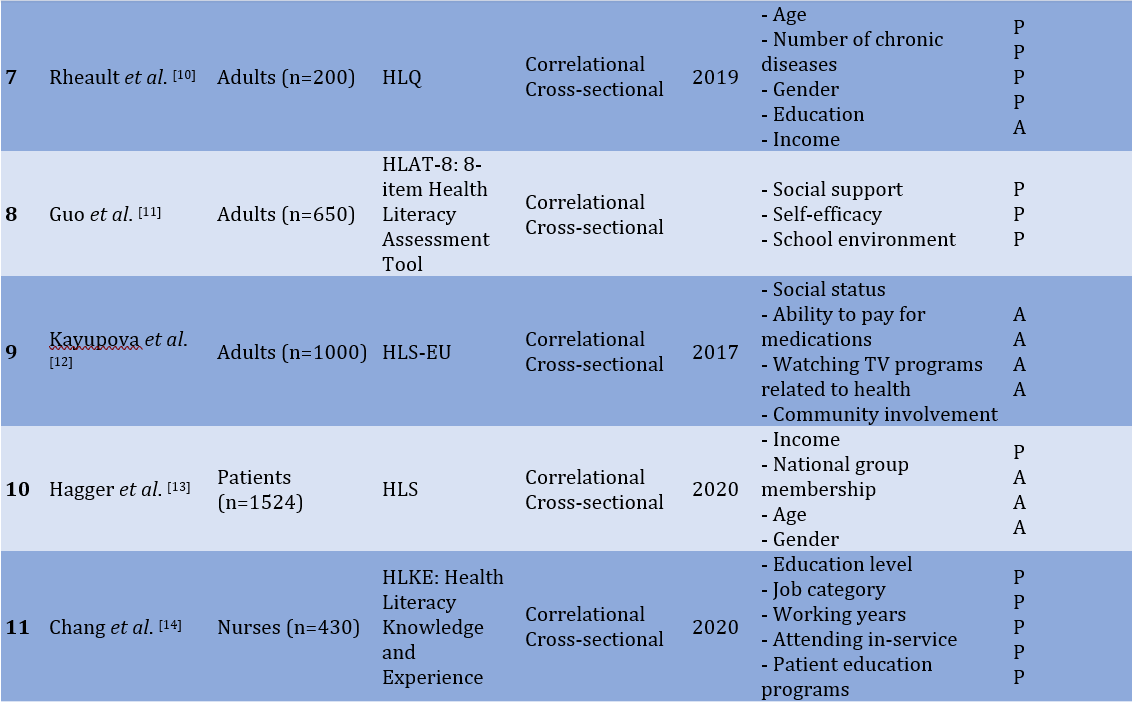

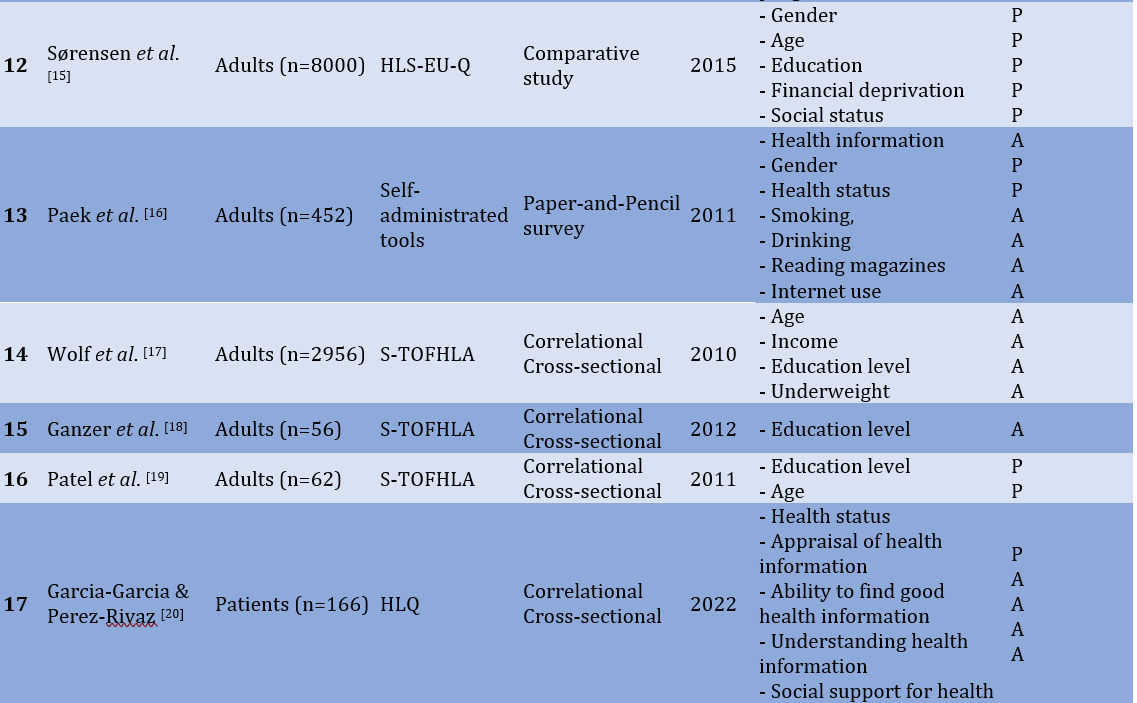

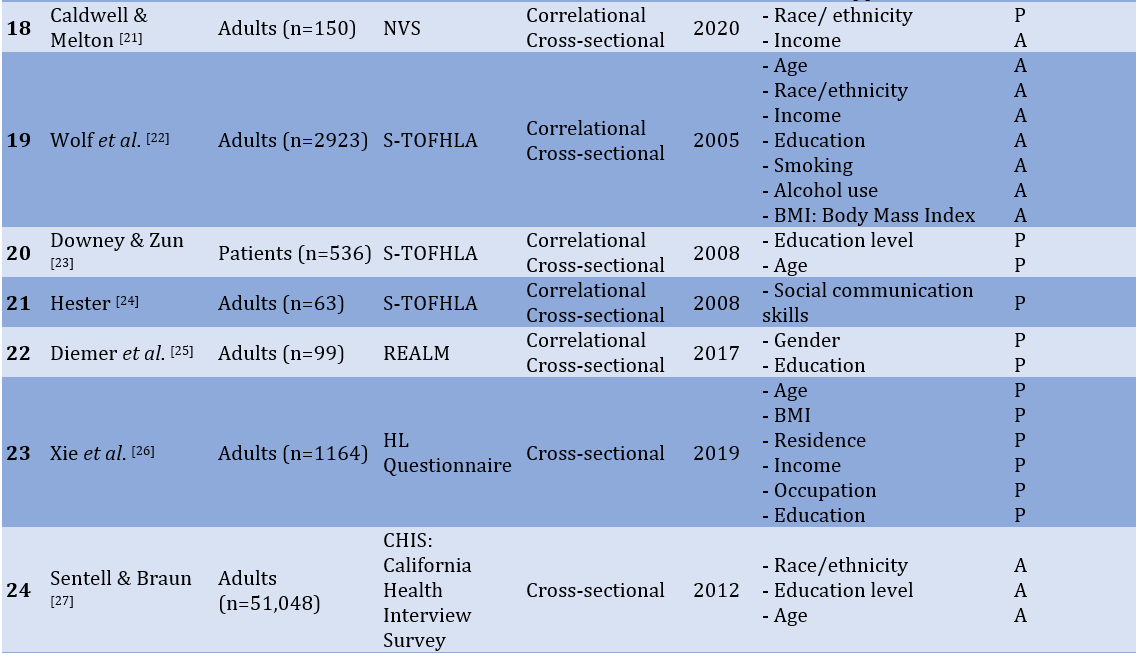

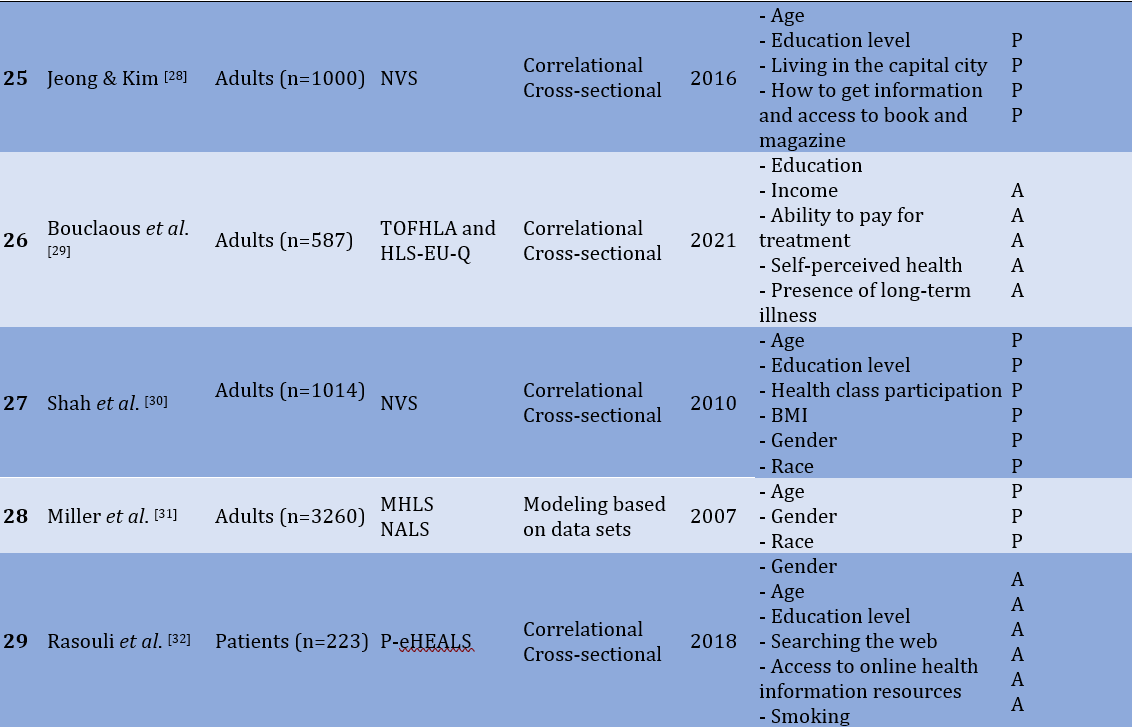

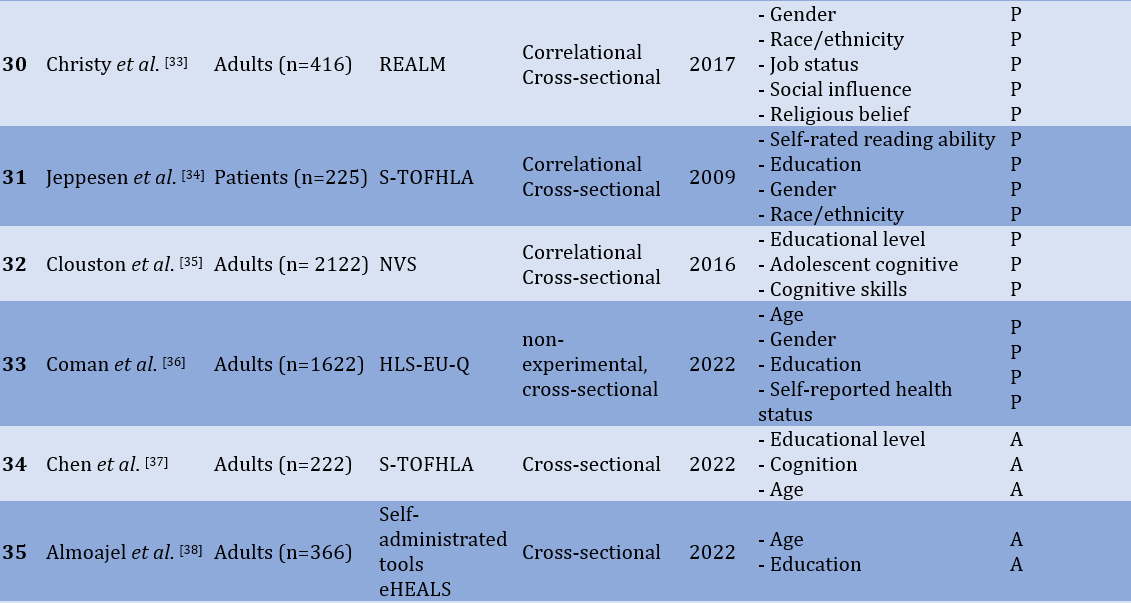

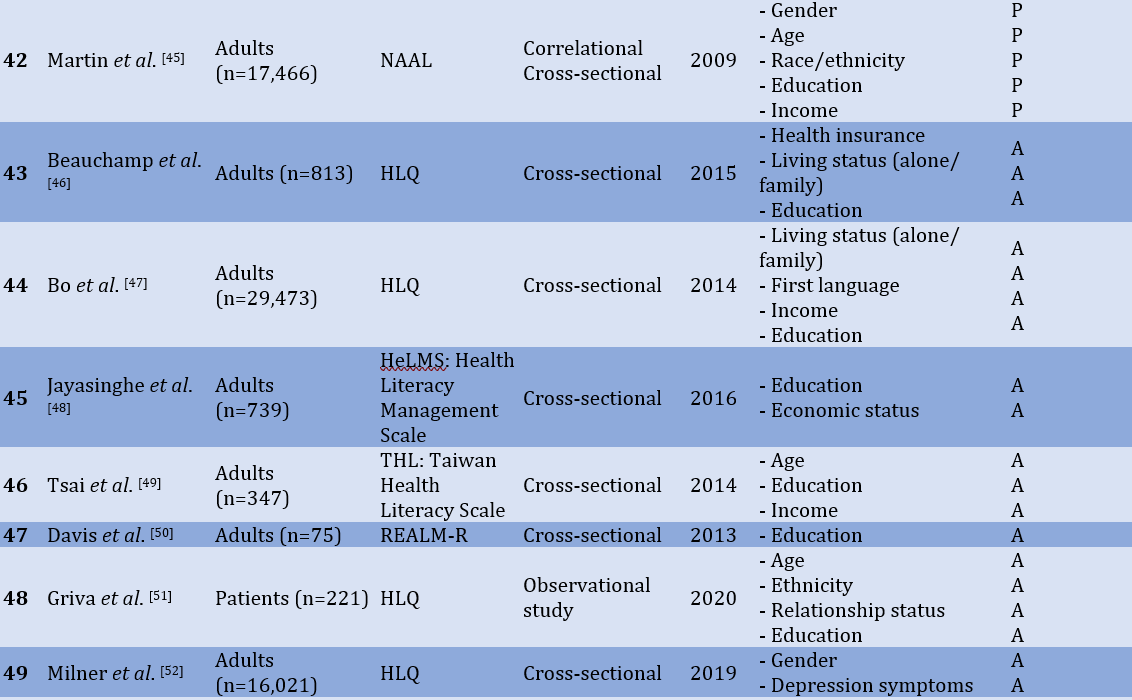

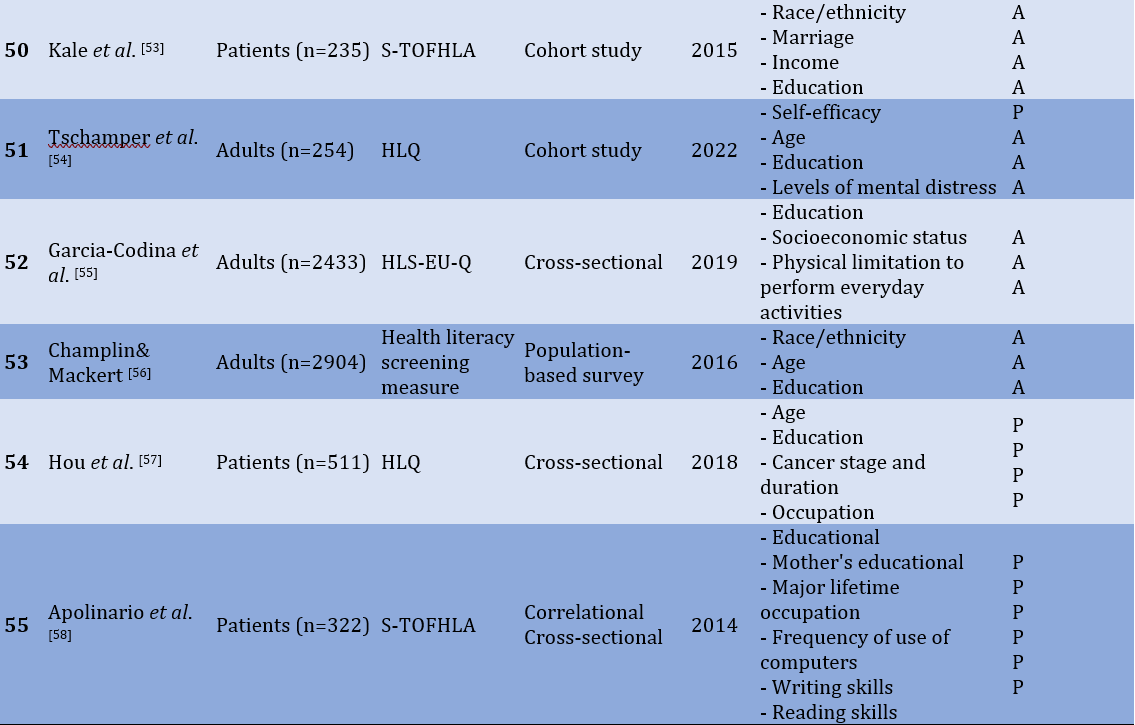

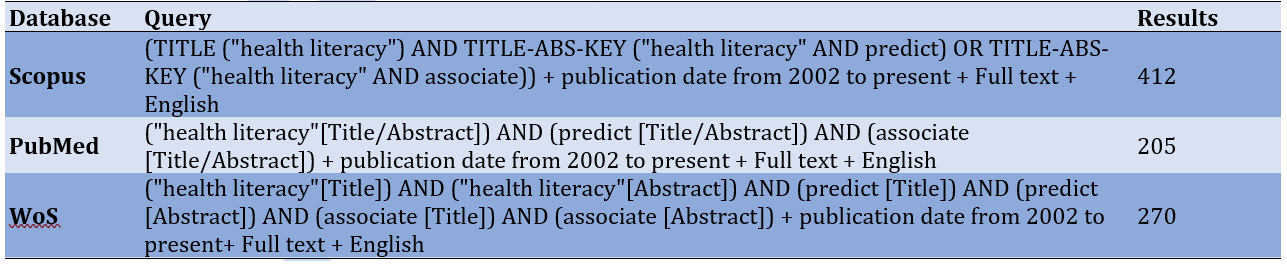

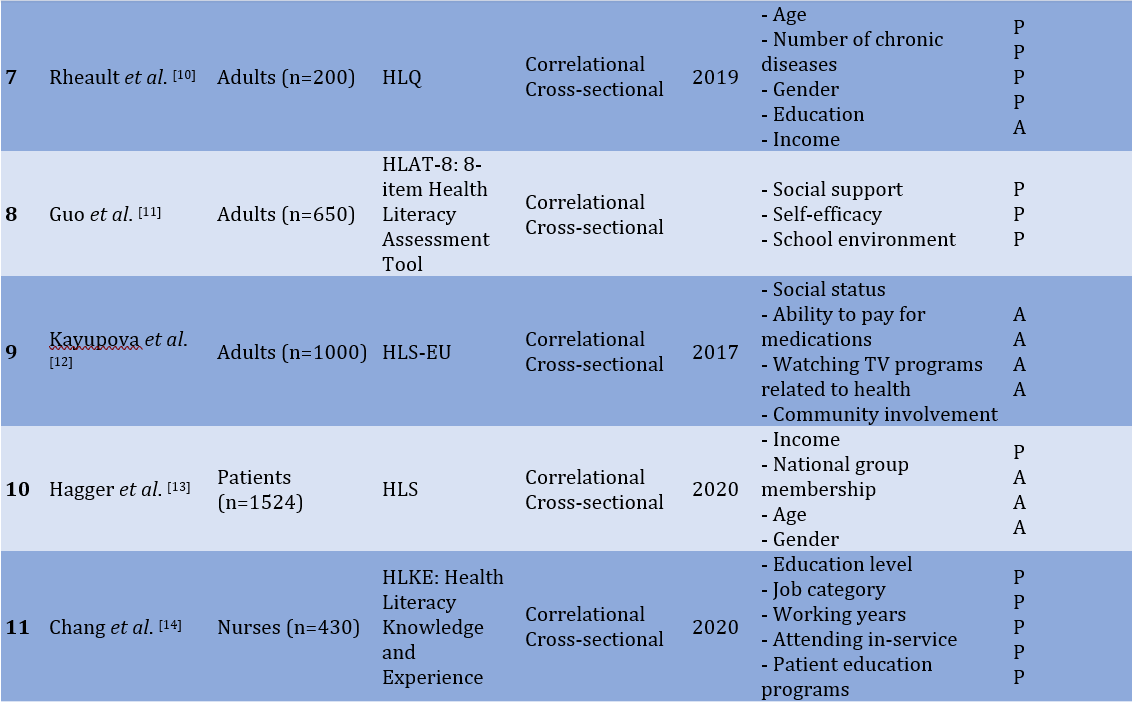

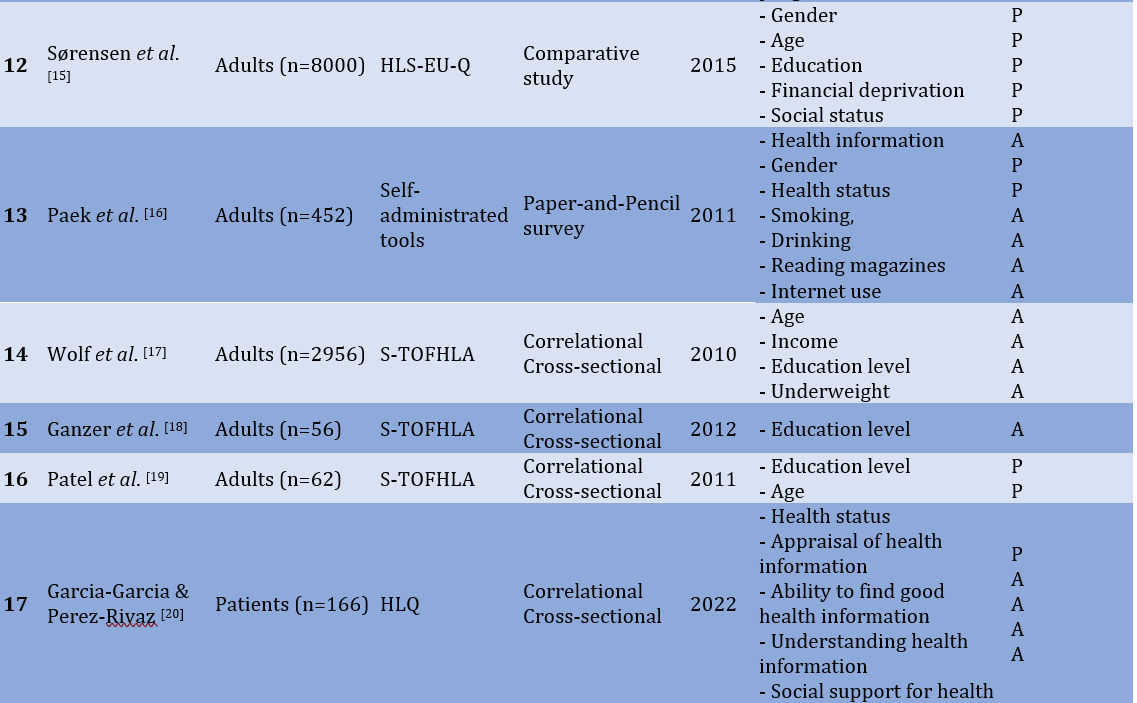

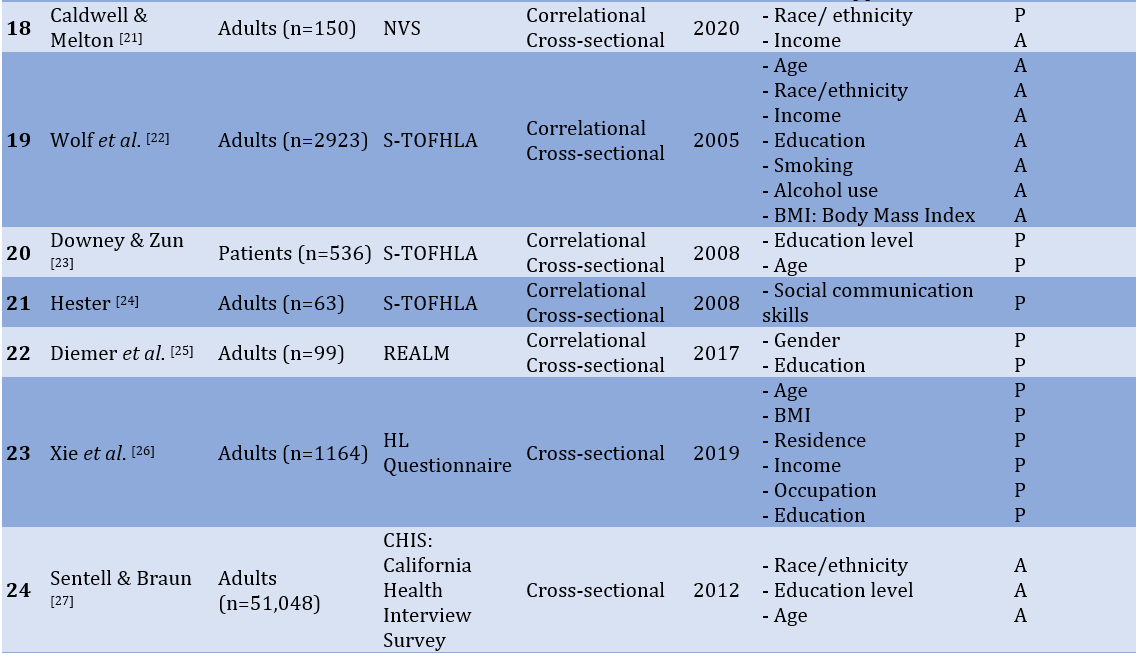

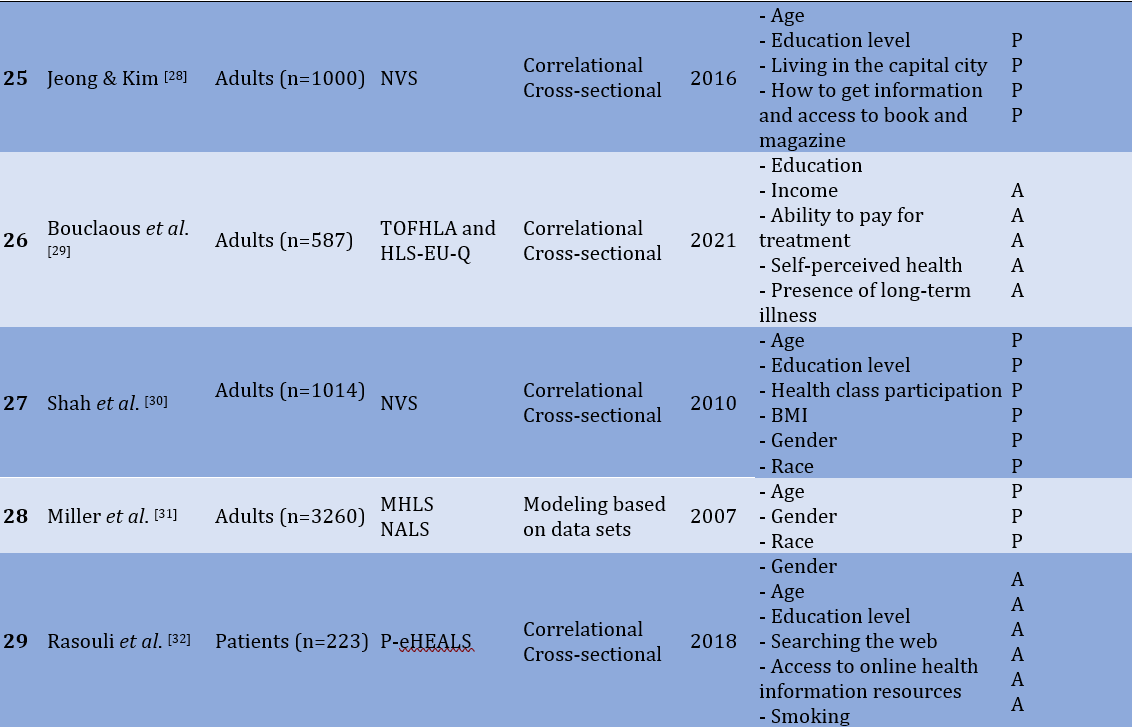

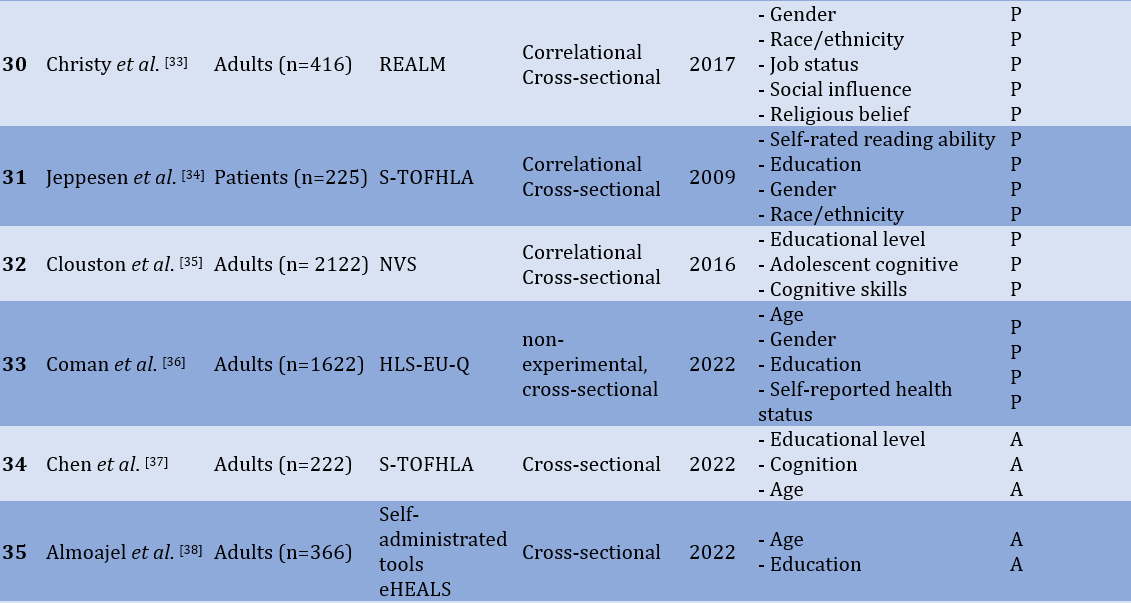

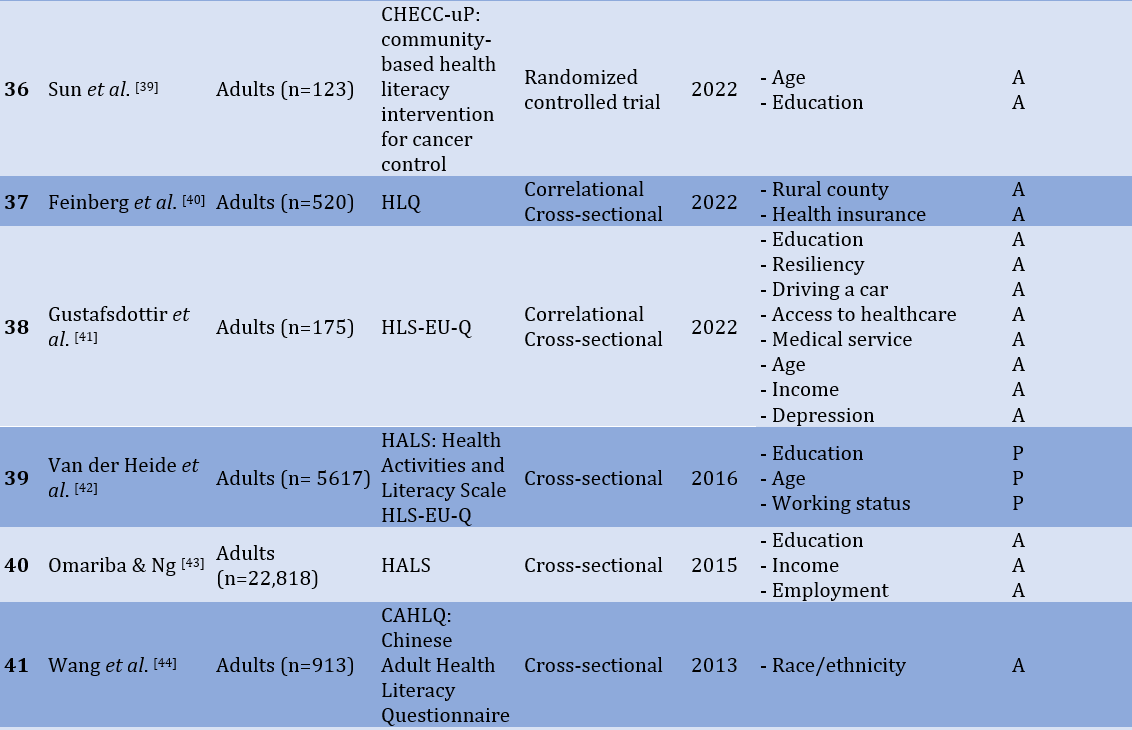

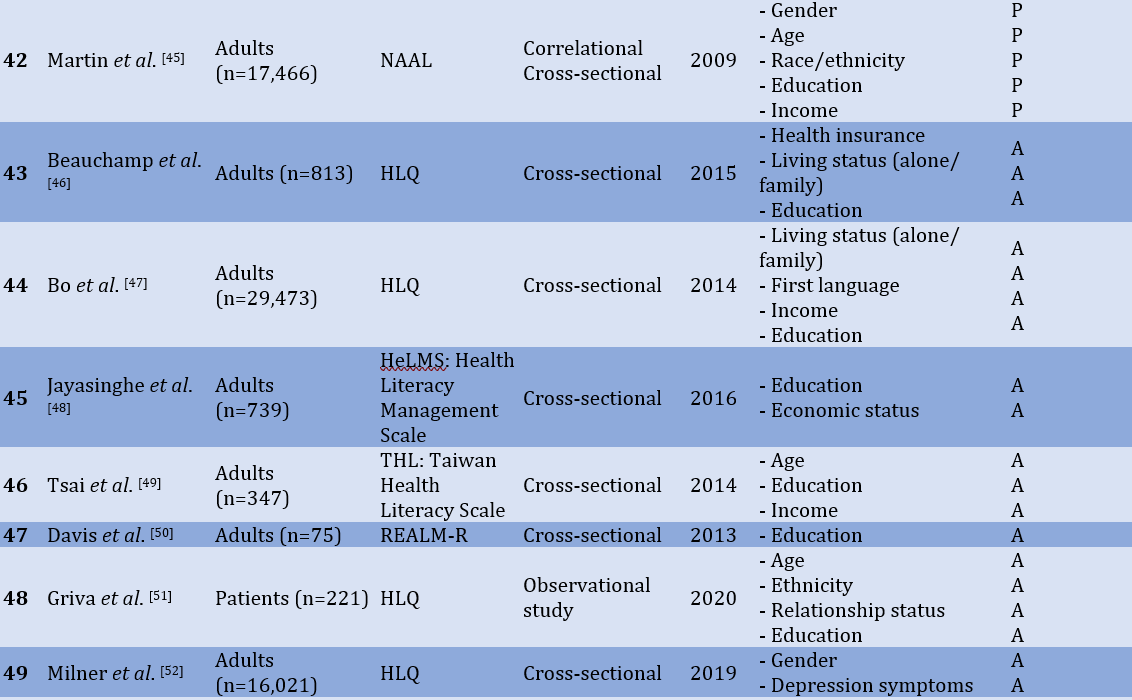

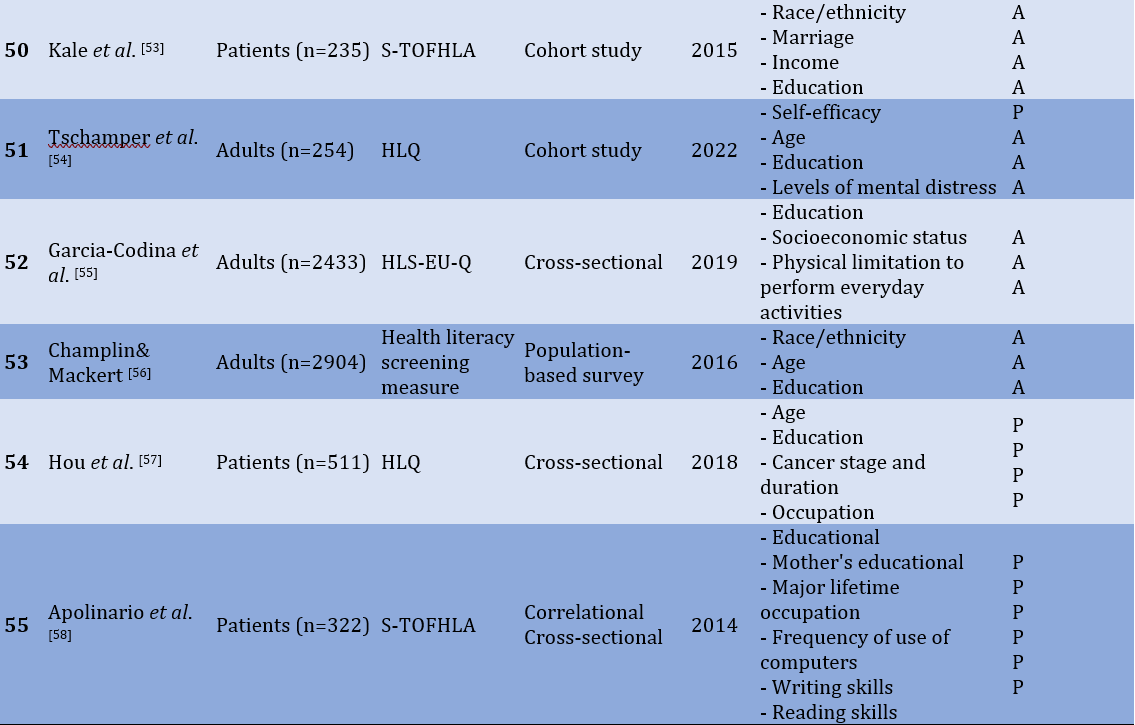

55 articles were reviewed considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Most participants were patients, adults, immigrants, nurses, and parents. The most frequent methods were "cross-sectional correlation" and "exploratory and modeling". The most frequent tools were National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), short version of TOHFLA (s-TOHFLA), Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), and Health Literacy Survey (HLS). Table 2 shows the results of this review.

Table 2) Factors that predict or are related to health literacy

There were more than 20 factors associated with HL, with the most frequent factors (3 times or more) were reported and discussed. These factors were age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, social status, occupation status, individual income, knowledge level, and health status.

26 studies showed that age can predict HL [4, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 19, 22, 23, 26-28, 30-32, 36-38, 41, 42, 45, 49, 51, 54, 56, 57]. 11 studies showed that race/ethnicity can predict Hl in adults [9, 21, 22, 27, 33, 34, 44, 45, 51, 53, 56]. 12 studies demonstrate that there is a significant relationship between gender and HL [10, 13, 15, 16, 25, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36, 45, 52] and, most of them show a strong relationship that gender can predict HL. There were 39 studies that found a direct and significant relationship between education level and HL [4, 7, 8, 10, 14, 15, 17-19, 22, 23, 25, 27-30, 32, 34-39, 41-43, 45-51, 53-58], and it is able to predict HL. Six studies showed that there is a direct significant relationship between social status and HL [11, 12, 15, 20, 24, 33], and can predict HL. There were seven studies that showed a significant direct relationship between occupational status and HL [11, 14, 26, 33, 42, 57, 58], and most of them can predict HL. In 14 studies, there was a significant direct relationship between individual income and HL scores [7, 10, 13, 17, 21, 22, 26, 29, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 53]. Five studies found that knowledge was associated with HL [9, 16, 20, 28, 32]. Ten studies concluded that health status was significantly associated with HL [7, 10, 16, 17, 22, 29, 30, 36, 54, 55], and most of them showed that it can predict HL.

Discussion

This is a systematic review of 56 articles on factors associated with or predicting HL. Many factors (individual or social) are associated with HL. The most frequent factors significantly associated with HL were age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, social status, occupational status, individual income, knowledge level, and health status.

There was an indirect relationship between HL and age, indicating that the youngest participants had higher HL scores. Online information sources such as the Internet and social media can be related to literacy. Therefore, using the Internet to search for health care information can be considered the development of HL skills. Since the use of the Internet and other online information sources is less in older age groups and older adults, it can be one of the influential. Some researchers concluded that older adults are less confident in their ability to use online health information to make health decisions and their ability to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality online health resources. In addition, the decline in cognitive ability associated with aging may reduce health literacy. Some indicators such as “abstract reasoning”, “verbal memory”, and “individual declines” [21, 28] in abstract reasoning can be related to HL.

The researchers focused on different races and ethnic groups (e.g., Asian, American, Hispanic, Korean, Chinese, white, and non-white). Most of them focused on race/ethnicity as a social inequality leading to disparities in health-related outcomes. Two important findings were that racial/ethnic differences influenced self-reported health and that HL was significantly associated with health status. In people whose native language is not English, Limited English proficiency (LEP) can be an essential factor in explaining differences in self-reported health status. On the other hand, discordance between the language used for data collection and the native language should be considered. In immigrants, some factors, such as differences in education, employment status, income, and health support services, in addition to the difficulty of living in a foreign country, can be noticed. The results showed that white people and native people had higher scores in HL.

Women had higher HL scores than men. Some studies asked women to read and interpret food labels, instructions for using medicines, the best way to deal with children’s fever, the best action to deal with a heart attack, how to deal with epileptic attacks, etc., and it was shown that they have good skills. It may be because of being more familiar due to traditional gender roles regarding healthcare and nutrition. Other possible reasons for the higher HL scores in women could be the greater respect for health standards in women, more attention to health/medical recommendations such as periodic examinations, and women's greater interest in acquiring, learning, and using health information.

People with higher education have better levels of HL and can understand health instructions better. These people have higher health information and perform better in applying health recommendations. Education level can contribute to the understanding of spoken instructions and is very important in health care. Although there is an extensive literature on spoken information processing (in the fields of education, communication studies, cognitive psychology, and gerontology), relatively little is known about people's ability to understand common spoken instructions and the relationship to reading skills. People with a low level of education have a low ability to find appropriate health information and understand health information to know what to do [37]. The results emphasize the importance of bridging the educational gap by providing educational materials with appropriate reading levels. It is an essential concept for health care providers to ensure that their health communication and written educational materials are sufficiently simplified (especially at the reading level) to improve understanding and reduce health disparities. A low level of education can harm an individual's functional HL and other domains of HL. Clinicians and policymakers should be attuned to these factors when communicating with people and designing healthcare systems to improve outcomes.

The researchers paid attention to economic well-being, social support, socially integrated, social communication, and social influence to investigate self-assessed social status. Social support (i.e., perceived support from family, friends, and significant others) will be more important in health conditions. Solving health problems can influence the improvement of the health status of the population as a whole. People with high social support had better scores in HL. People with limited financial and social resources are more likely to have limited health literacy. People who are socially integrated are healthier than others. Social communication and understanding the social network structure can help connect it. People who are socially well connected can receive more health services because they are informed about the health services of the community. HL can be distributed through social networks. Social communication skills allow a person to comment, explain, question, request, clarify, respond, and inform in a social context [59]. Social influence has seven principles, which are social learning, social comparison, social norms, social facilitation, social cooperation, social competition, and social cognition [60].

Researchers investigated occupation status, considering job categories, employment type, and job history. There is a significant difference between different job categories and HL scores [14]. Health resources should be rationally allocated to different occupational groups to enhance the efficiency of their utilization [26] and can promote HL. Employment type (e.g., employed, not employed, retired, and disabled) was strongly associated with HL, and those who were employed had higher HL scores. In addition, lifetime main occupation was associated with HL, and individuals with lifetime main occupation had higher scores on HL [58]. Occupation status can play an essential role in decision-making and self-rated health status and can finally affect HL.

Researchers considered income as an important factor associated with HL. Some researchers focused on total income (family income), and others on individual income. There were two limitations to the income survey: Some participants preferred not to declare individual income [10], and homemakers did not have a certain income (considering the role of gender in HL and higher HL in women). People with higher income have high level of HL. Higher income is associated with having adequate health information [10], and they can make better health decisions. Low-income people have more restrictions on accessing health care and are less likely to seek health care [13]. This finding should be paramount in the health policy by politicians. They should have some interventions, such as additional support in lower-income communities for health management [7]. It can help low-income people take care of their health and potentially prevent health disparities.

Knowledge is awareness, understanding, or information obtained by experience or study, which can be in a person’s mind [29]. In the field of health, knowledge can be used to know and understand health information and the ability to find good health information and understanding enough to know what to do (decision making). It can be noted that mostly in patients, for example in diabetic patients, diabetes knowledge scores were predictive of HL level [7]. The crucial role of socialization factors such as interpersonal factors (e.g., parents, friends) and media (e.g., traditional and non-traditional) in the distribution of health information and the teaching of health-related skills should be considered. This information is positive for the perception of HL [16]. HL is the capacity to understand basic health information, and the use of valid information can enhance the level of knowledge and promote HL.

Health is a state of body, mind, or spirit that is related to all aspects of human life. As sickness is a different situation, it may affect the quality of life and health literacy. Researchers considered self-reported health status, number of chronic diseases, underweight, BMI, depression, and distress. In healthy people, education, age, health status, gender, social status, BMI (fit or underweight), race/ethnicity, and job status are the most predictors of HL. Therefore, online health information and the ability to find good information, income, healthcare insurance, and social support are the most critical factors associated with HL. However, in patients, age, education, race/ethnicity, knowledge, and income are predictors of HL, and gender and online health information is associated with HL. So, it can be said that health status determines the predictors of HL.

This study concluded that younger people, white people, females, people with higher education levels, good social status, occupation, especially lifetime main occupations, higher individual income, higher knowledge level, and healthy people have high levels of HL. Regarding lower levels of HL in older adults, it can be said that addressing health literacy at an early age can develop the ability to understand health information and promote interactions with the healthcare system, leading to positive health outcomes later. It should be said that the specific vulnerable groups, e.g., non-whites, older adults, males, and social status in communities, should be considered in the HL survey. It is an essential implication for health care providers to ensure that their health communication and written educational materials are sufficiently simplified (especially at the reading level) to improve patient understanding and reduce health disparities. The health system can pay attention to the improvement of the health status of people with a low social base and low income by providing information and holding health education courses at no cost or a small cost. Increasing the levels of HL can develop more capacity in each person in health behaviors, realizing shared responsibility for their health, developing the person to improve the quality of life individually. Socially, increasing health literacy will contribute to the development of equity and sustainability of changes in public health.

Conclusion

Many factors (individual or social) are associated with health literacy. The most common factors significantly associated with health literacy are age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, social status, occupational status, individual income, knowledge level, and health status. Health literacy includes different constructs and may vary based on socio-economic and demographic characteristics in different communities (e.g., men/women, black/non-black, patient/healthy, employed/unemployed, young/adult, different social status, different individual income).

Author contribution: There is one author.

Acknowledgements: This is an individual study.

Ethical Permission: Nothing to report.

Conflict of Interests: Nothing to report.

Authors’ Contribution: Sabaghinejad Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (100%)

Funding: Nothing to report.

Health Literacy (HL) is a rapidly growing topic in healthcare. In the past few years, the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution has renovated the creation and sharing of health-related information, and people can live in the flow of health-related information. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health literacy as: ‘The cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to access, understand, and use information in ways that maintain and promote good health” [1]. HL includes a range of critical skills that allow individuals to empower themselves to promote health behaviors. Individual and social behavior can be changed towards a healthy lifestyle. This is recognized as shared health responsibility, which is significantly associated with HL.

Low Health Literacy (LHL) is recognized as a global problem that can result in difficulty reading and understanding health information, lower medication compliance, higher rates of hospitalization, and 1.5 to 3 times greater poor health status [2]. Healthcare professionals may not recognize factors associated with HL and may not be sufficiently aware of their impact on health outcomes. LHL can lead to failure to acquire or correctly understand health information. It will have negative impacts on individual’s health and can lead to health disparities. So, it is crucial to identify the factors related to HL. It can help to better understand HL and improve health status and quality of life. Although the effects of HL have been widely studied, only a few have investigated the factors associated with HL.

Environmental, political and social factors can determine health. They include a wide range of skills that people acquire throughout their lives to search for, evaluate, and use health information. They can use the right information to make better decisions, reduce health risks, and improve quality of life. These skills can be influenced by cultural beliefs, understanding of the health system, and health information. Health literacy skills are essential as contemporary health care systems, and people are commonly expected to make the best decisions regarding health care.

This study aimed to review the articles related to health literacy in the last 20 years and explain the factors associated with health literacy or predict it.

Information and Methods

This systematic review examined quantitative research articles published from 2002 to 2022 to explore factors that predict or are associated with HL. Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science (WoS) databases were searched. Table 1 shows the search reports in all databases and the number of retrieved records.

Table 1) Database search construction

The inclusion criteria were:

1. Research articles

2. Quantitative method

3. Focusing on factors that can predict HL or associate with it

4. English full-text is available.

5. Focusing on adults in sampling

6. Publication date between 2002 to 2023

The exclusion criteria were:

1. Articles that focused on specific aspects of HL (e.g., oral HL, media HL).

2. Articles that focused on specific sample (e.g., nurses, immigrants, women).

3. Articles that HL was a predictor of other variables.

4. Articles with no significant relation

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses framework (PRISMA) [3] was used to conduct a transparent process. Figure 1 shows the final item reporting process.

Figure 1) PRISMA flow chart for new systematic reviews

The role of factors (prediction or association) was determined based on the most repeated. For example, race/ethnicity role was predictor in 7 articles and association in 5 articles. So, it was considered as a predictor. The most frequent factors had a prediction role.

Findings

55 articles were reviewed considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Most participants were patients, adults, immigrants, nurses, and parents. The most frequent methods were "cross-sectional correlation" and "exploratory and modeling". The most frequent tools were National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), short version of TOHFLA (s-TOHFLA), Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), and Health Literacy Survey (HLS). Table 2 shows the results of this review.

Table 2) Factors that predict or are related to health literacy

There were more than 20 factors associated with HL, with the most frequent factors (3 times or more) were reported and discussed. These factors were age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, social status, occupation status, individual income, knowledge level, and health status.

26 studies showed that age can predict HL [4, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 19, 22, 23, 26-28, 30-32, 36-38, 41, 42, 45, 49, 51, 54, 56, 57]. 11 studies showed that race/ethnicity can predict Hl in adults [9, 21, 22, 27, 33, 34, 44, 45, 51, 53, 56]. 12 studies demonstrate that there is a significant relationship between gender and HL [10, 13, 15, 16, 25, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36, 45, 52] and, most of them show a strong relationship that gender can predict HL. There were 39 studies that found a direct and significant relationship between education level and HL [4, 7, 8, 10, 14, 15, 17-19, 22, 23, 25, 27-30, 32, 34-39, 41-43, 45-51, 53-58], and it is able to predict HL. Six studies showed that there is a direct significant relationship between social status and HL [11, 12, 15, 20, 24, 33], and can predict HL. There were seven studies that showed a significant direct relationship between occupational status and HL [11, 14, 26, 33, 42, 57, 58], and most of them can predict HL. In 14 studies, there was a significant direct relationship between individual income and HL scores [7, 10, 13, 17, 21, 22, 26, 29, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 53]. Five studies found that knowledge was associated with HL [9, 16, 20, 28, 32]. Ten studies concluded that health status was significantly associated with HL [7, 10, 16, 17, 22, 29, 30, 36, 54, 55], and most of them showed that it can predict HL.

Discussion

This is a systematic review of 56 articles on factors associated with or predicting HL. Many factors (individual or social) are associated with HL. The most frequent factors significantly associated with HL were age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, social status, occupational status, individual income, knowledge level, and health status.

There was an indirect relationship between HL and age, indicating that the youngest participants had higher HL scores. Online information sources such as the Internet and social media can be related to literacy. Therefore, using the Internet to search for health care information can be considered the development of HL skills. Since the use of the Internet and other online information sources is less in older age groups and older adults, it can be one of the influential. Some researchers concluded that older adults are less confident in their ability to use online health information to make health decisions and their ability to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality online health resources. In addition, the decline in cognitive ability associated with aging may reduce health literacy. Some indicators such as “abstract reasoning”, “verbal memory”, and “individual declines” [21, 28] in abstract reasoning can be related to HL.

The researchers focused on different races and ethnic groups (e.g., Asian, American, Hispanic, Korean, Chinese, white, and non-white). Most of them focused on race/ethnicity as a social inequality leading to disparities in health-related outcomes. Two important findings were that racial/ethnic differences influenced self-reported health and that HL was significantly associated with health status. In people whose native language is not English, Limited English proficiency (LEP) can be an essential factor in explaining differences in self-reported health status. On the other hand, discordance between the language used for data collection and the native language should be considered. In immigrants, some factors, such as differences in education, employment status, income, and health support services, in addition to the difficulty of living in a foreign country, can be noticed. The results showed that white people and native people had higher scores in HL.

Women had higher HL scores than men. Some studies asked women to read and interpret food labels, instructions for using medicines, the best way to deal with children’s fever, the best action to deal with a heart attack, how to deal with epileptic attacks, etc., and it was shown that they have good skills. It may be because of being more familiar due to traditional gender roles regarding healthcare and nutrition. Other possible reasons for the higher HL scores in women could be the greater respect for health standards in women, more attention to health/medical recommendations such as periodic examinations, and women's greater interest in acquiring, learning, and using health information.

People with higher education have better levels of HL and can understand health instructions better. These people have higher health information and perform better in applying health recommendations. Education level can contribute to the understanding of spoken instructions and is very important in health care. Although there is an extensive literature on spoken information processing (in the fields of education, communication studies, cognitive psychology, and gerontology), relatively little is known about people's ability to understand common spoken instructions and the relationship to reading skills. People with a low level of education have a low ability to find appropriate health information and understand health information to know what to do [37]. The results emphasize the importance of bridging the educational gap by providing educational materials with appropriate reading levels. It is an essential concept for health care providers to ensure that their health communication and written educational materials are sufficiently simplified (especially at the reading level) to improve understanding and reduce health disparities. A low level of education can harm an individual's functional HL and other domains of HL. Clinicians and policymakers should be attuned to these factors when communicating with people and designing healthcare systems to improve outcomes.

The researchers paid attention to economic well-being, social support, socially integrated, social communication, and social influence to investigate self-assessed social status. Social support (i.e., perceived support from family, friends, and significant others) will be more important in health conditions. Solving health problems can influence the improvement of the health status of the population as a whole. People with high social support had better scores in HL. People with limited financial and social resources are more likely to have limited health literacy. People who are socially integrated are healthier than others. Social communication and understanding the social network structure can help connect it. People who are socially well connected can receive more health services because they are informed about the health services of the community. HL can be distributed through social networks. Social communication skills allow a person to comment, explain, question, request, clarify, respond, and inform in a social context [59]. Social influence has seven principles, which are social learning, social comparison, social norms, social facilitation, social cooperation, social competition, and social cognition [60].

Researchers investigated occupation status, considering job categories, employment type, and job history. There is a significant difference between different job categories and HL scores [14]. Health resources should be rationally allocated to different occupational groups to enhance the efficiency of their utilization [26] and can promote HL. Employment type (e.g., employed, not employed, retired, and disabled) was strongly associated with HL, and those who were employed had higher HL scores. In addition, lifetime main occupation was associated with HL, and individuals with lifetime main occupation had higher scores on HL [58]. Occupation status can play an essential role in decision-making and self-rated health status and can finally affect HL.

Researchers considered income as an important factor associated with HL. Some researchers focused on total income (family income), and others on individual income. There were two limitations to the income survey: Some participants preferred not to declare individual income [10], and homemakers did not have a certain income (considering the role of gender in HL and higher HL in women). People with higher income have high level of HL. Higher income is associated with having adequate health information [10], and they can make better health decisions. Low-income people have more restrictions on accessing health care and are less likely to seek health care [13]. This finding should be paramount in the health policy by politicians. They should have some interventions, such as additional support in lower-income communities for health management [7]. It can help low-income people take care of their health and potentially prevent health disparities.

Knowledge is awareness, understanding, or information obtained by experience or study, which can be in a person’s mind [29]. In the field of health, knowledge can be used to know and understand health information and the ability to find good health information and understanding enough to know what to do (decision making). It can be noted that mostly in patients, for example in diabetic patients, diabetes knowledge scores were predictive of HL level [7]. The crucial role of socialization factors such as interpersonal factors (e.g., parents, friends) and media (e.g., traditional and non-traditional) in the distribution of health information and the teaching of health-related skills should be considered. This information is positive for the perception of HL [16]. HL is the capacity to understand basic health information, and the use of valid information can enhance the level of knowledge and promote HL.

Health is a state of body, mind, or spirit that is related to all aspects of human life. As sickness is a different situation, it may affect the quality of life and health literacy. Researchers considered self-reported health status, number of chronic diseases, underweight, BMI, depression, and distress. In healthy people, education, age, health status, gender, social status, BMI (fit or underweight), race/ethnicity, and job status are the most predictors of HL. Therefore, online health information and the ability to find good information, income, healthcare insurance, and social support are the most critical factors associated with HL. However, in patients, age, education, race/ethnicity, knowledge, and income are predictors of HL, and gender and online health information is associated with HL. So, it can be said that health status determines the predictors of HL.

This study concluded that younger people, white people, females, people with higher education levels, good social status, occupation, especially lifetime main occupations, higher individual income, higher knowledge level, and healthy people have high levels of HL. Regarding lower levels of HL in older adults, it can be said that addressing health literacy at an early age can develop the ability to understand health information and promote interactions with the healthcare system, leading to positive health outcomes later. It should be said that the specific vulnerable groups, e.g., non-whites, older adults, males, and social status in communities, should be considered in the HL survey. It is an essential implication for health care providers to ensure that their health communication and written educational materials are sufficiently simplified (especially at the reading level) to improve patient understanding and reduce health disparities. The health system can pay attention to the improvement of the health status of people with a low social base and low income by providing information and holding health education courses at no cost or a small cost. Increasing the levels of HL can develop more capacity in each person in health behaviors, realizing shared responsibility for their health, developing the person to improve the quality of life individually. Socially, increasing health literacy will contribute to the development of equity and sustainability of changes in public health.

Conclusion

Many factors (individual or social) are associated with health literacy. The most common factors significantly associated with health literacy are age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, social status, occupational status, individual income, knowledge level, and health status. Health literacy includes different constructs and may vary based on socio-economic and demographic characteristics in different communities (e.g., men/women, black/non-black, patient/healthy, employed/unemployed, young/adult, different social status, different individual income).

Author contribution: There is one author.

Acknowledgements: This is an individual study.

Ethical Permission: Nothing to report.

Conflict of Interests: Nothing to report.

Authors’ Contribution: Sabaghinejad Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (100%)

Funding: Nothing to report.

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Health Literacy

Received: 2023/08/31 | Accepted: 2023/11/4 | Published: 2023/11/10

Received: 2023/08/31 | Accepted: 2023/11/4 | Published: 2023/11/10

References

1. Nutbeam D, Kickbusch I. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int. 1998;13(4):349-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/13.4.349]

2. DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x]

3. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71):1-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.n71]

4. Caldwell EP. Health literacy in adolescents with sickle cell disease: The influence of caregiver health literacy. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2020;25(2):e12284. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jspn.12284]

5. Manganello JA, Sojka CJ. An exploratory study of health literacy and African American adolescents. Comprehens Child Adolesc Nurs. 2016;39(3):221-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/24694193.2016.1196264]

6. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x]

7. Cutilli CC, Simko LC, Colbert AM, Bennett IM. Health literacy, health disparities, and sources of health information in U.S. older adults. Orthop Nurs. 2018;37(1):54-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NOR.0000000000000418]

8. Haun J, Luther S, Dodd V, Donaldson P. Measurement variation across health literacy assessments: Implications for assessment selection in research and practice. J Health Commun. 2012;17(sup3):141-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2012.712615]

9. Azreena E, Suriani I, Juni MH, Fuziah P. Factors associated with health literacy among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus patients attending a government health clinic, 2016. Int J Public Health Clin Sci. 2016;3(6):50-64 [Link]

10. Rheault H, Coyer F, Jones L, Bonner A. Health literacy in Indigenous people with chronic disease living in remote Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):523. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-019-4335-3]

11. Guo S, Davis E, Yu X, Naccarella L, Armstrong R, Abel T, et al. Measuring functional, interactive and critical health literacy of Chinese secondary school students: reliable, valid and feasible? Glob Health Promot. 2018;25(4):6-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1757975918764109]

12. Kayupova G, Turdaliyeva B, Tulebayev K, Van Duong T, Chang PW, Zagulova D. Health literacy among visitors of district polyclinics in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(8):1062-70. [Link]

13. Hagger MS, Hardcastle SJ, Hu M, Kwok S, Lin J, Nawawi HM, et al. Health literacy in familial hypercholesterolemia: A cross-national study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(9):936-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2047487318766954]

14. Chang Y-W, Li T-C, Chen Y-C, Lee J-H, Chang M-C, Huang L-C. Exploring knowledge and experience of health literacy for chinese-speaking nurses in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7609. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17207609]

15. Sørensen K, Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, Ganahl K, Slonska Z, Doyle G, et al. Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):1053-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckv043]

16. Paek H-J, Reber BH, Lariscy RW. Roles of interpersonal and media socialization agents in adolescent self-reported health literacy: a health socialization perspective. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(1):131-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/her/cyq082]

17. Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson J, Baker DW. In search of 'low health literacy': Threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1335-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.013]

18. Ganzer CA, Insel KC, Ritter LS. Associations between working memory, health literacy, and recall of the signs of stroke among older adults. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(5):236-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182666231]

19. Patel PJ, Joel S, Rovena G, Pedireddy S, Saad S, Rachmales R, et al. Testing the utility of the newest vital sign (NVS) health literacy assessment tool in older African-American patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):505-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.014]

20. García-García D, Pérez-Rivas FJ. Health literacy and its sociodemographic predictors: a cross-sectional study of a population in Madrid (Spain). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11815. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph191811815]

21. Caldwell EP, Melton K. Health literacy of adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;55:116-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2020.08.020]

22. Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(17):1946-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/archinte.165.17.1946]

23. Downey LVA, Zun LS. Assessing adult health literacy in urban healthcare settings. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1304-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31509-1]

24. Hester EJ. An investigation of the relationship between health literacy and social communication skills in older adults. Commun Disord Q. 2008;30(2):112-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1525740108324040]

25. Diemer FS, Haan YC, Nannan Panday RV, van Montfrans GA, Oehlers GP, Brewster LM. Health literacy in Suriname. Soc Work Health Care. 2017;56(4):283-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00981389.2016.1277823]

26. Xie Y, Ma M, Zhang Yn, Tan X. Factors associated with health literacy in rural areas of Central China: structural equation model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-019-4094-1]

27. Sentell T, Braun KL. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. J Health Commun. 2012;17(sup3):82-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2012.712621]

28. Jeong SH, Kim HK. Health literacy and barriers to health information seeking: a nationwide survey in South Korea. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(11):1880-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.015]

29. Bouclaous CH, Salem S, Ghanem A, Saade N, El Haddad J, Bou Malham M, et al. Health literacy levels and predictors among Lebanese adults visiting outpatient clinics in Beirut. Health Lit Res Pract. 2021;5(4):e295-309. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/24748307-20211012-02]

30. Shah LC, West P, Bremmeyr K, Savoy-Moore RT. Health literacy instrument in family medicine: the "newest vital sign" ease of use and correlates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(2):195-203. [Link] [DOI:10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.070278]

31. Miller MJ, Degenholtz HB, Gazmararian JA, Lin CJ, Ricci EM, Sereika SM. Identifying elderly at greatest risk of inadequate health literacy: A predictive model for population-health decision makers. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2007;3(1):70-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2006.06.001]

32. Rasouli HR, Farajzadeh M, Tadayon AH. Evaluation of e-health literacy and its predictor factors among patients referred to a military hospital in Tehran, Iran, 2017. J Milit Med. 2018;20(1):83-92. [Persian] [Link]

33. Christy SM, Gwede CK, Sutton SK, Chavarria E, Davis SN, Abdulla R, et al. Health literacy among medically underserved: the role of demographic factors, social influence, and religious beliefs. J Health Commun. 2017;22(11):923-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2017.1377322]

34. Jeppesen KM, Coyle JD, Miser WF. Screening questions to predict limited health literacy: a cross-sectional study of patients with diabetes mellitus. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):24-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1370/afm.919]

35. Clouston SAP, Manganello JA, Richards M. A life course approach to health literacy: the role of gender, educational attainment and lifetime cognitive capability. Age Ageing. 2016;46(3):493-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afw229]

36. Coman MA, Forray AI, Van den Broucke S, Chereches RM. Measuring Health Literacy in Romania: Validation of the HLS-EU-Q16 Survey Questionnaire. Int J Public Health. 2022;67:1604272. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/ijph.2022.1604272]

37. Chen P, Callisaya M, Wills K, Greenaway T, Winzenberg T. Cognition, educational attainment and diabetes distress predict poor health literacy in diabetes: a cross-sectional analysis of the SHELLED study. PloS One. 2022;17(4):e0267265. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0267265]

38. Almoajel A, Alshamrani S, Alyabsi M. The relationship between e-health literacy and breast cancer literacy among Saudi women. Front Public Health. 2022;10:841102. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2022.841102]

39. Sun C-A, Chepkorir J, Jennifer Waligora Mendez K, Cudjoe J, Han H-R. A descriptive analysis of cancer screening health literacy among black women living with HIV in Baltimore, Maryland. Health Lit Res Pract. 2022;6(3):e175-81. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/24748307-20220616-01]

40. Feinberg I, Tighe EL, Ogrodnick MM. Strengthening the case for universal health literacy: The dispersion of health literacy experiences across a Southern U.S. State. Health Lit Res Pract. 2022;6(3):e182-90. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/24748307-20220620-01]

41. Gustafsdottir SS, Sigurdardottir AK, Mårtensson L, Arnadottir SA. Making Europe health literate: including older adults in sparsely populated Arctic areas. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):511. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-12935-1]

42. van der Heide I, Uiters E, Sørensen K, Röthlin F, Pelikan J, Rademakers J, et al. Health literacy in Europe: the development and validation of health literacy prediction models. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(6):906-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckw078]

43. Omariba DWR, Ng E. Health literacy and disability: differences between generations of Canadian immigrants. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(3):389-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00038-014-0640-0]

44. Wang C, Li H, Li L, Xu D, Kane RL, Meng Q. Health literacy and ethnic disparities in health-related quality of life among rural women: results from a Chinese poor minority area. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):153. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-11-153]

45. Martin LT, Ruder T, Escarce JJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Sherman D, Elliott M, et al. Developing predictive models of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1211-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11606-009-1105-7]

46. Beauchamp A, Buchbinder R, Dodson S, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, McPhee C, et al. Distribution of health literacy strengths and weaknesses across socio-demographic groups: a cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):678. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-015-2056-z]

47. Bo A, Friis K, Osborne RH, Maindal HT. National indicators of health literacy: ability to understand health information and to engage actively with healthcare providers - a population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1095. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1095]

48. Jayasinghe UW, Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, van Driel M, Mazza D, et al. The impact of health literacy and life style risk factors on health-related quality of life of Australian patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):68. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12955-016-0471-1]

49. Tsai HM, Cheng CY, Chang SC, Yang YM, Wang HH. Health literacy and health-promoting behaviors among multiethnic groups of women in Taiwan. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(1):117-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1552-6909.12269]

50. Davis DW, Jones VF, Logsdon MC, Ryan L, Wilkerson-McMahon M. Health promotion in pediatric primary care: importance of health literacy and communication practices. Clin Pediatr. 2013;52(12):1127-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0009922813506607]

51. Griva K, Yoong RKL, Nandakumar M, Rajeswari M, Khoo EYH, Lee VYW, et al. Associations between health literacy and healthcare utilization and mortality in patients with coexisting diabetes and end-stage renal disease: A prospective cohort study. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(3):405-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12413]

52. Milner A, Shields M, King T. The influence of masculine norms and mental health on health literacy among men: Evidence from the ten to men study. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13(5):1557988319873532. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1557988319873532]

53. Kale MS, Federman AD, Krauskopf K, Wolf M, O'Conor R, Martynenko M, et al. The association of health literacy with illness and medication beliefs among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0123937. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0123937]

54. Tschamper MK, Wahl AK, Hermansen Å, Jakobsen R, Larsen MH. Parents of children with epilepsy: Characteristics associated with high and low levels of health literacy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;130:108658. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.yebeh.2022.108658]

55. Garcia-Codina O, Juvinyà-Canal D, Amil-Bujan P, Bertran-Noguer C, González-Mestre MA, Masachs-Fatjo E, et al. Determinants of health literacy in the general population: results of the Catalan health survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1122. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-019-7381-1]

56. Champlin S, Mackert M. Creating a screening measure of health literacy for the health information national trends survey. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(4):291-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0890117116639557]

57. Hou WH, Huang YJ, Lee Y, Chen CT, Lin GH, Hsieh CL. Validation of the integrated model of health literacy in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(6):498-505. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000540]

58. Apolinario D, Mansur LL, Carthery-Goulart MT, Brucki SM, Nitrini R. Detecting limited health literacy in Brazil: development of a multidimensional screening tool. Health Promot Int. 2014;29(1):5-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/dat074]

59. Ukrainetz TA. Contextualized language intervention: Scaffolding PreK-12 literacy achievement. 1st Edition. Greenville, SC: Thinking Publications; 2007. [Link]

60. Stibe A, Cugelman B. Social influence scale for technology design and transformation. In: Human-Computer Interaction-INTERACT 2019: 17th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Paphos, Cyprus, September 2-6, 2019, Proceedings, Part III 17; 2019: Springer. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-29387-1_33]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |