Volume 11, Issue 3 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(3): 333-339 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bahmani A, Golmohamadi S, Taymoori P, Bahrami M. The Effect of a School-based Intervention on Boys' ear and Hearing-Related Health literacy in Iran. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (3) :333-339

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-69427-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-69427-en.html

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

Keywords: Ear [MeSH], Health Literacy [MeSH], Hearing [MeSH], Ear Protective Devices [MeSH], Students [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 738 kb]

(3303 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1295 Views)

Full-Text: (394 Views)

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.1 billion young people aged 12 to 35 years are at risk for hearing loss (HL) or reduction because of a lack of sufficient education, dangerous and unprotected use of music devices, and exposure to high noise from music players and places that emit intense noise [1]. The survey conducted in Iran showed that 13.5 people out of every 1000 people suffer from one of the disabilities, including deafness and HL [2]. Another study in Iran reported adequate ear and hearing-related health literacy in 2.8% of samples and inadequate in 97.2% [3]. According to the estimate of the WHO, at least half of the cases of deafness and HL worldwide can be avoided through prevention, early detection, and appropriate management [1].

Exposure to loud noise can result in physical, psychological, socioeconomic, and intellectual health problems, as well as decreased productivity and academic performance [4]. Improper use of music players has destructive effects on hearing, and in people who listen to music daily for at least one year with an intensity of more than 50% of the output of the device, the threshold of cochlear hair cell damage is reduced [5]. HL caused by noise is increasing among young people who are exposed to noise from recreational situations and music devices due to a lack of awareness or misconceptions about the effects of exposure to noise [6]. The potential for portable listening device (PLD) use to cause music-induced hearing loss (MIHL) has recently been raised as a public health concern [7]. Currently, a considerable body of research has established that exposure to loud sounds and music can have a significant and detrimental effect on the auditory system. In addition, the current generation of PLDs is capable of producing output levels high enough to elicit MIHL with prolonged exposure [8-10].

In recent years, the field of hearing and related problems has been the focus of Iran's health policymakers, and related statistics report a high prevalence (about 5-6%) of HL in Iran (2). The state of health literacy in the field of ear and hearing care is unfavorable in Iran (5, 6). The results of a survey showed that the level of health literacy related to ears and hearing among Iranian youths and adolescents and the skills in the field of ear health literacy, including searching, understanding, evaluating, and using information and services related to ear health, were insufficient or low [3]. Young people frequently have no idea that they are losing their hearing (5). Personal listening devices, such as mobile phones, can lead to dangerous levels of noise exposure, especially among users who listen at high volumes for extended periods, putting children and teenagers at risk for long-term HL [11].

Therefore, there is a need for new approaches to maintain and promote hearing health and prevent and manage ear diseases. This approach emphasizes the implementation of promotional programs to promote public awareness and increase hearing health literacy (HHL) and prevention and early detection of HL [3, 12].

People in an empowered society have the cognitive skills to recognize and address health problems [13]. Health literacy refers to making informed decisions, gathering the data needed to address a health issue, obtaining relevant information, evaluating its quality, and choosing the best way to apply it[14]. The idea of health literacy has grown, and it now covers more than just being able to read and write [15]. Health literacy combines interactive health promotion skills and reading and writing competence. It is the ability to access, interpret, and use fundamental health information and services to promote health [16].

Epidemiologic surveys of HL in different parts of the world and among different ethnic groups with widely varying marital habits, socioeconomic status, and environment help understand its frequency in specific areas and its predisposing factors [12]. Adolescents and youth learn healthy habits and behaviors; therefore, suitable treatments can reduce the negative effects of low HHL in this group. Teenagers and young people are more exposed to loud music and improper use of hands-free. This study explored how an educational intervention affects ear and hearing-related health literacy in boys from Sanandaj.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This experimental study was conducted in Sanandaj, west of Iran, in 2021. Schools were selected by random cluster sampling from two districts (in terms of socio-economic context) of Sanandaj so that eight high schools were selected from districts. Ten students from each school were randomly selected from the list of all students. Based on Martin et al.'s study, who reported a 30% increase in awareness (as the proportion of the desired outcome in the intervention group), and considering a confidence interval of 95%, a power of 20%, and the following formula, from each selected school, 40 students were randomly selected (40 cases per group):

n=(z1-α/2+z1-β)2 [p1q1+p2q2]/(p1-p2)2

(z1-α/2+z1-β)2=7.85

Where, P1 represents the proportion of the desired outcome in the intervention group (30%) and P2 is the proportion of the desired outcome in the control group (10%); assuming a 30% increase in the intervention group and 10% in the control groups, the minimum sample size was estimated to be 36 people in each group, and finally, 40 people were considered for each group.

Method

Inclusion criteria were having a smartphone, informed consent, and willingness to participate. Before the study, students were made aware of its goals. Also, parents and students signed consent forms. The ethics committee of the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences authorized the study (IR.MUK.REC.1400.101). The Kurdistan Education Department allowed the research to be performed in four male high schools. Intervention and control groups received self-reported questionnaires. Two weeks after the last educational session, the questionnaires were re-distributed among the intervention and control groups.

Research tools

The required data were obtained using a researcher-made questionnaire. The content and face validity of the questionnaire were checked using the viewpoints of six experts related to the health fields of hearing and health education. Using a literature review based on the general framework of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adolescents (TOFHLA) (13, 14) as well as ear and hearing-related health literacy (7, 15-19), the primary items of the instrument were collected. The primary items were developed to include the three skills of applying hearing health information, communicating, and comprehension and evaluation. After preparing the initial version of the questionnaire, which had 44 questions, 39 items were confirmed based on content and face validity. These 39 questions contained three questions about demographic information, 14 questions about the ability to apply hearing health information, 13 questions about communicating skills, and 12 questions about comprehension and evaluation skills. The content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were computed. To determine the CVR, items with the range (necessary, not essential, but useful, not necessary) were reviewed according to the Lawshe table, and items with a CVR value greater than 0.99 were preserved. To calculate the CVI, questions with a CVI greater than 0.7 were retained using Waltz and Bausell's CVI. According to Cronbach's alpha, the questionnaire's general validity and reliability were 0.84% and 0.86%, respectively. The three domains were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree). A score of 100 was given to always/strongly agree, 75 to often agree, 50 to sometimes/relatively agree, 25 for rarely disagree, and zero to never or strongly disagree.

Intervention

This study was conducted online due to the spread of COVID-19. Educational programs were implemented through WhatsApp and groups named "School Research Team" were formed separately for each of the intervention schools on this app. A pre-post-test was considered, the students were given instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. The intervention group received six sessions of 50-65 minutes of virtual education. The educational content contained topics about ear and hearing-related health literacy [17-21]. The topics included information about the ear and auditory system, noise and its effect on the hearing system, symptoms of HL, preventive recommendations, dangers of personal listening devices, symptoms that may be an early indication of HL (e.g. tinnitus), and some methods of reducing mental conflicts. The educational interventions also aimed at informing students of the measures that can be taken to reduce exposure to loud sounds, such as reducing the volume and time of exposure, reducing unsafe exposure to sounds, and giving advice for safe listening in accordance with the listening safe guideline (WHO) [22]. This intervention also addressed the relationship between normative or incorrect attitudes as well as peer effects on reducing the likelihood of music-induced HL. Educational videos, audio files, pamphlets, educational slides, and educational tracts were used as educational material. Education was presented with an interval of one week to allow questions and mutual feedback. The control group received no educational sessions but received the educational pamphlets after the administration of the final follow-up questionnaires.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 23 software and described by descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequency, mean, and standard deviation. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables between the two study groups. A significance level of less than 0.05 was considered.

Findings

The average age of students in the intervention and control groups was 14.08±0.83 and 14.08±0.83 years, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of age (p=0.054), grade (p=0.014), and the source of students' hearing information (p=0.94).

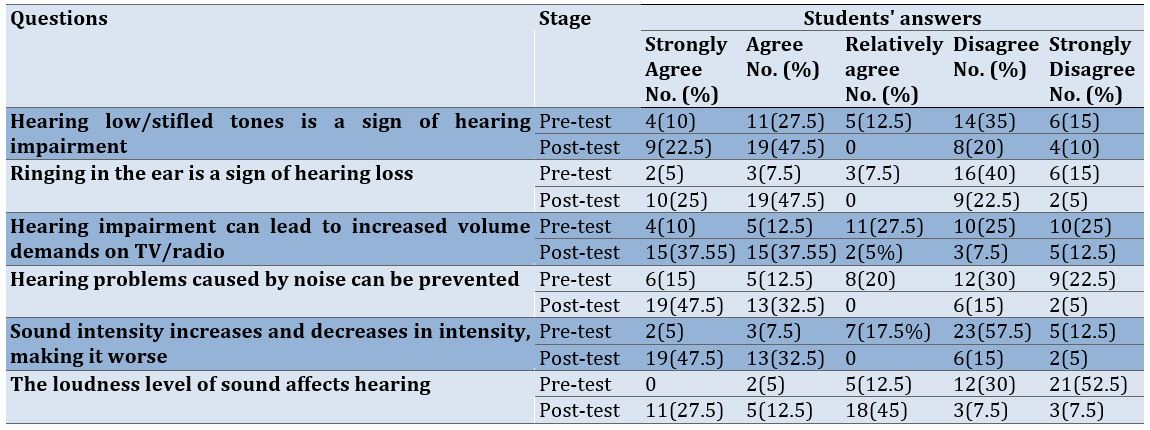

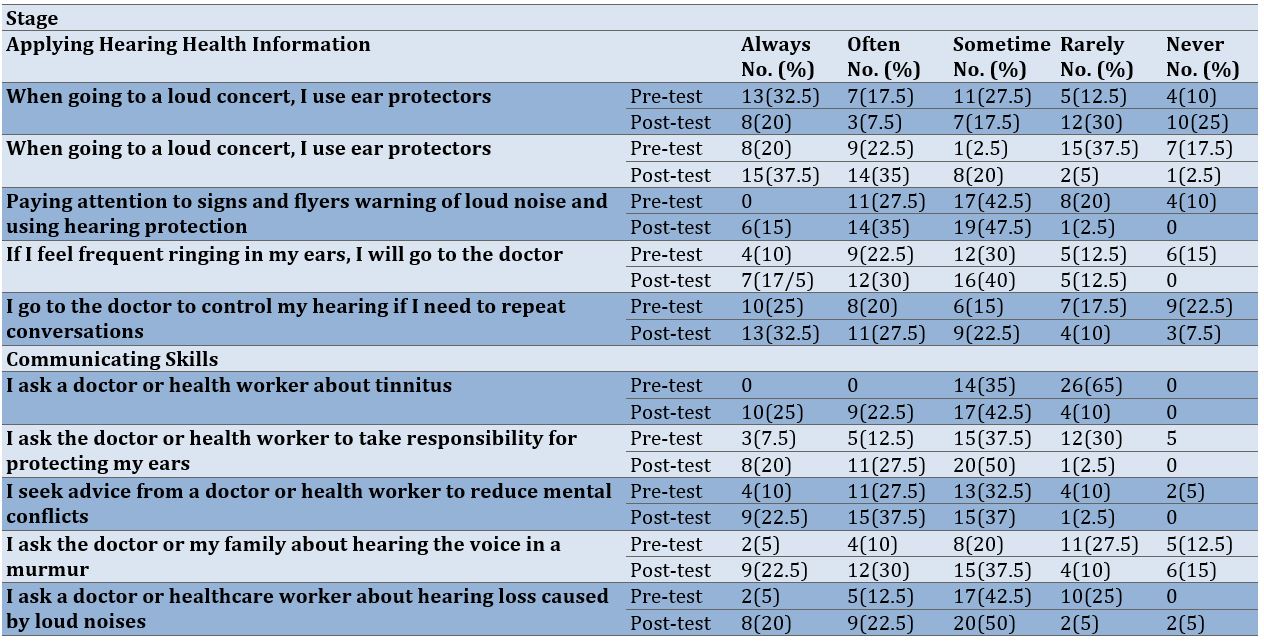

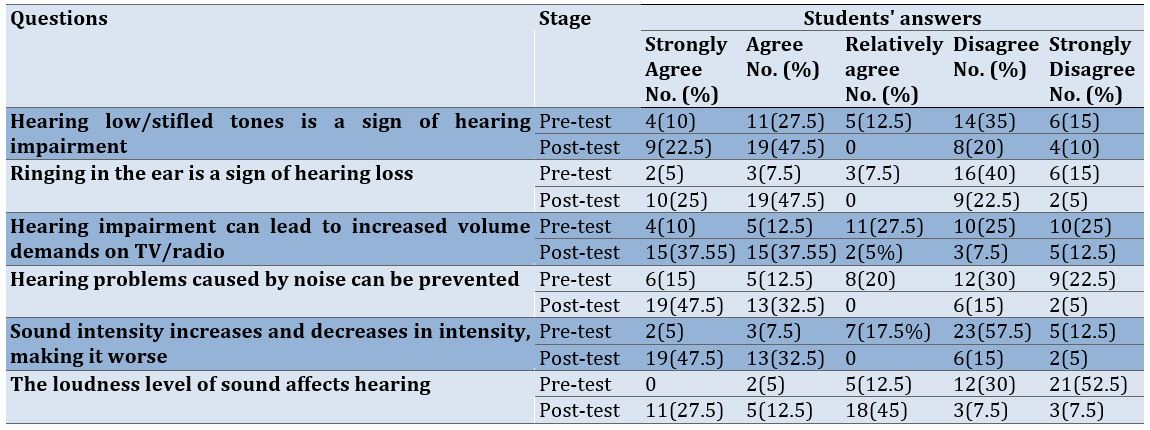

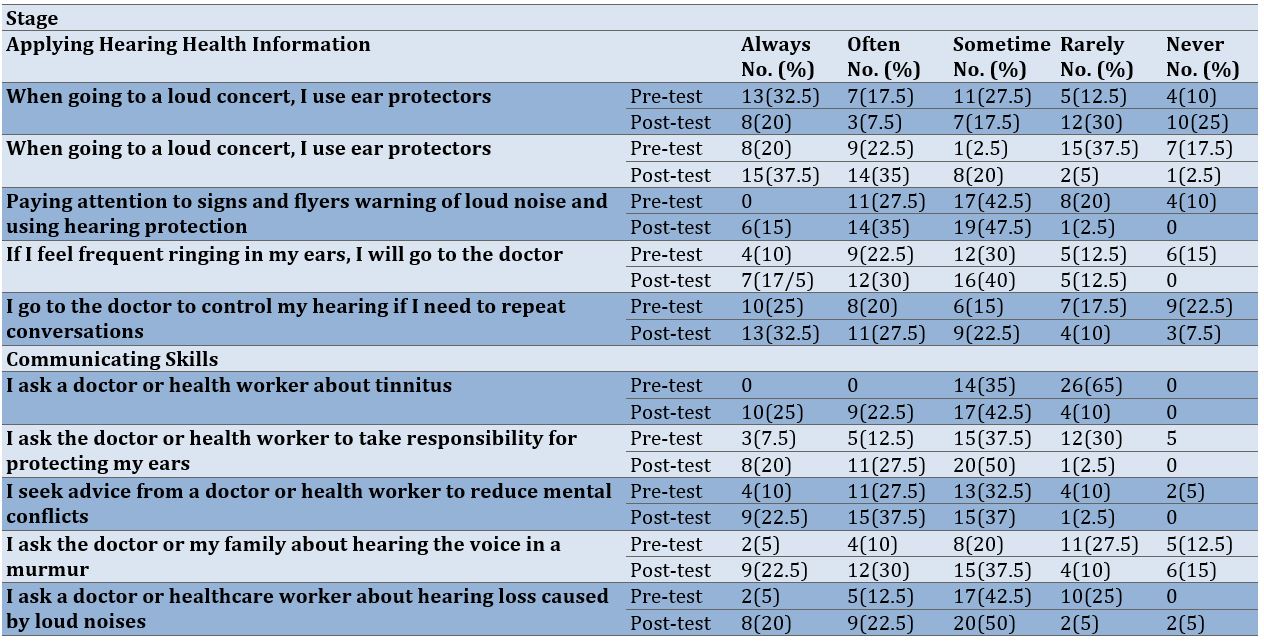

The frequency distribution of students' answers to the related hearing health literacy questions before and after the intervention is shown in Tables 1 and 2. After the intervention, hearing health literacy improved and increased significantly in all areas. Before the intervention, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the mean score of the students in the domains of ear and hearing-related health literacy (applying hearing health information, communicating, and comprehension and evaluation; p>0.05).

Table 1) Students' mean scores for comprehension and evaluation skills before and after the intervention in the intervention group

Table 2) Frequency of the intervention group students' responses to questions about applying hearing health information and communicating skills before and after the intervention

After the intervention, the mean score of applying hearing health information in the intervention group was 56.9±11.9, which was significantly higher than the control group (28.4±13.2), and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). Also, the mean score of communicating skills and comprehension and evaluation in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the control group (p<0.001). Unlike the control group, after the educational program, the ear and hearing-related health literacy scores of the intervention group improved, and the difference between the scores before and after the intervention was significant (p<0.001). Table 3 shows the comparison of the mean scores of ear and hearing-related health literacy during the pre-test to the post-test.

Table 3) Comparison of mean scores (range: 0-100) of ear and hearing-related health literacy from pre-test to post-test

Discussion

Hearing health literacy has been studied in an effort to gain a greater understanding of it. No study has investigated hearing health literacy programs for Iranian boys. Our findings may provide detailed information for health promotion planners regarding hearing-related health literacy and appropriate interventions. The results of this research may have critical implications beyond the creation of interventions to enhance the auditory and hearing health of Iranian students. Many younger individuals, for instance, inaccurately attribute HL to old age. Another example is that if a person's right earrings, it is a sign of receiving happy news, and for the left ear, it is a sign of receiving bad news in Iranian culture. After the intervention, a significant proportion of the students' perceptions positively changed in this regard, and they perceived ear ringing as a sign of HL (before the intervention, 5% of students agreed, which after it, reached 29%). Understanding the frequency of HL in specific areas and among specific ethnic groups with widely varying habits, sociocultural status, and environment is aided by global and ethnically diverse HL prevalence surveys, which also contribute to general knowledge about the predisposing factors of HL [23, 24]. Iran is a Muslim country, and in this cultural environment, the existence of dance clubs is prohibited. As a result, young people may try to experience pleasures that have normative limits with music players that are very loud and change their intensity in short intervals. Their interest is experiencing excitement and they are either unaware of its consequences or do not take its consequences seriously. The percentage of agreement with the negative consequences of changing the sound intensity increased from 5% to 32%.

Users of portable listening devices report them as a means of modulating their emotional states [25-27]. The loud volume of music, as a component of teenage culture, acts as a symbol of transgression and estrangement from an older generation [7]. As a distinguishing characteristic of teenage identity or as a potent stimulant for mood alteration, loud music is enjoyed and tolerated more by adolescents and young adults than by children and older people [25, 28]; listening to loud music is a popular pastime among today's youth as a means of relieving stress [25]. The current intervention program advises students to address their mental conflicts by seeking guidance and counseling from healthcare professionals and parents instead of listening to loud music. Several techniques were also instructed to reduce mental dissonance. Asking a doctor for advice to get rid of mental conflicts, instead of listening to loud music improved from 28% to 39%, resulting in an improvement of 11%. The results offer insights into the personal factors that affect adolescents' use of loud music as a means of regulating their emotions. The implementation of educational interventions led to noteworthy enhancements in the intervention group's comprehension and evaluation, communication, and ability to apply hearing health information skills in comparison to the control group. These findings are in line with previous studies that have demonstrated the notable impact of education on students' attitudes, perceptions, intentions, and motivation concerning recreational noise exposure [29]. Other research findings indicated that educational programs in the field of hearing protection had a positive impact on the knowledge levels of students and teens [23, 29-31]. Young adults and teenagers may not be aware of the risks associated with noise (30). According to research by Seedat et al., more than a quarter of health science students thought they would not need to worry about tinnitus or HL until they were much older. Their research indicated that a significant proportion of students in the health sciences field held the belief that concerns regarding tinnitus or HL would not be relevant until a later stage in life. Specifically, more than 25% of the participants expressed this viewpoint [32]. Therefore, if people are educated, they might be able to prevent unfavorable outcomes associated with their hearing health. This shows the importance of making the public informed about the importance of protecting their hearing [33-35].

False beliefs about peer behavior are an example of a socially normative issue that must be addressed in any intervention [36, 37]. Adolescents have no social motivation to minimize their exposure if they think all of their peers are listening loudly. Therefore, we paid attention to the influences of normative views and peers in the education program. For example, discussing the consequences of high-decibel noise with peers, talking about the harmful effects of loud noise with friends, and telling peers that good hearing means not having a hearing problem were included in the curriculum. In addition, discussing the dangers of loud decibels with peers, warning them that good hearing is not indicative of no hearing impairment, and telling peers that good hearing is not indicative of no hearing impairment were included in education programs.

No similar study explored the HHL domains in Iran, except for a cross-sectional by Shams et al. [3]. Due to the questionnaire's similarities, some of the present study's findings are compared to that study. Before the instruction, the mean HHL scores of the intervention and control groups were 39.7±8.5 and 40.1±6.2, respectively. Shams et al. found a mean HHL score of 30.81±3.75 among a sample of 4890 Iranian youth [3]. Our findings confirmed their findings that students were weak in comprehension and evaluation, communication, and hearing health information application. Shams et al. revealed that women had a significantly higher degree of adequate HHL compared to men. However, insufficient HHL was reported by both genders. Because our study was an intervention on male students, the effect of gender on HHL cannot be compared to the study by Shams et al. The prevalence of HL in the population of adolescents and young adults in Iran is generally low [3]. These findings suggest that young Iranians (12-25 years old) may be at risk for developing ear and hearing problems. As such, these findings highlight the need for considering all dimensions of health literacy when designing interventions that improve HHL among young Iranians. Differences in the study's methodology make it difficult to derive public health implications. Nevertheless, the integration of these initiatives into our training programs promises to increase the effectiveness of the hearing training program.

Our findings demonstrated that virtual education increased ear and hearing-related health literacy in school students. Therefore, interpersonal interactive educational interventions are more successful and continue longer than internet-based education, and they can effectively improve school students' hearing health literacy [38]. Adolescent interventions should be monitored over time to ensure that improvements in hearing health literacy are maintained.

Conclusion

Education enhances hearing-related health literacy. Young people in Iran have a generally poor knowledge of ear and hearing health. The findings of our study indicate that maintaining a healthy ear should be prioritized and appropriate measures should be taken to prevent this non-contagious health issue. Our results show that protecting healthy hearing and preventing this non-communicable disease should be a top priority. Our six sessions of instructional interventions improve schoolchildren's ear and hearing health literacy. This result may contribute to future studies and intervention development.

Acknowledgments: This article is the result of Sina Golmohamadi's master's thesis in the field of health education and health promotion entitled “The effect of a school-based intervention on boys' ear and hearing-related health literacy in Sanandaj, Iran”. The authors would like to thank the students and schools that made this study possible.

Ethical Permission: This article was derived from a research project approved by the Research and Technology Deputy of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUK.REC.1400.101).

Authors’ Contribution: Golmohamadi S (First Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Bahmani A (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Taymoori P (Third Author), Methodologist/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Bahrami M (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%)

Conflicts of interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Funding/Support: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.1 billion young people aged 12 to 35 years are at risk for hearing loss (HL) or reduction because of a lack of sufficient education, dangerous and unprotected use of music devices, and exposure to high noise from music players and places that emit intense noise [1]. The survey conducted in Iran showed that 13.5 people out of every 1000 people suffer from one of the disabilities, including deafness and HL [2]. Another study in Iran reported adequate ear and hearing-related health literacy in 2.8% of samples and inadequate in 97.2% [3]. According to the estimate of the WHO, at least half of the cases of deafness and HL worldwide can be avoided through prevention, early detection, and appropriate management [1].

Exposure to loud noise can result in physical, psychological, socioeconomic, and intellectual health problems, as well as decreased productivity and academic performance [4]. Improper use of music players has destructive effects on hearing, and in people who listen to music daily for at least one year with an intensity of more than 50% of the output of the device, the threshold of cochlear hair cell damage is reduced [5]. HL caused by noise is increasing among young people who are exposed to noise from recreational situations and music devices due to a lack of awareness or misconceptions about the effects of exposure to noise [6]. The potential for portable listening device (PLD) use to cause music-induced hearing loss (MIHL) has recently been raised as a public health concern [7]. Currently, a considerable body of research has established that exposure to loud sounds and music can have a significant and detrimental effect on the auditory system. In addition, the current generation of PLDs is capable of producing output levels high enough to elicit MIHL with prolonged exposure [8-10].

In recent years, the field of hearing and related problems has been the focus of Iran's health policymakers, and related statistics report a high prevalence (about 5-6%) of HL in Iran (2). The state of health literacy in the field of ear and hearing care is unfavorable in Iran (5, 6). The results of a survey showed that the level of health literacy related to ears and hearing among Iranian youths and adolescents and the skills in the field of ear health literacy, including searching, understanding, evaluating, and using information and services related to ear health, were insufficient or low [3]. Young people frequently have no idea that they are losing their hearing (5). Personal listening devices, such as mobile phones, can lead to dangerous levels of noise exposure, especially among users who listen at high volumes for extended periods, putting children and teenagers at risk for long-term HL [11].

Therefore, there is a need for new approaches to maintain and promote hearing health and prevent and manage ear diseases. This approach emphasizes the implementation of promotional programs to promote public awareness and increase hearing health literacy (HHL) and prevention and early detection of HL [3, 12].

People in an empowered society have the cognitive skills to recognize and address health problems [13]. Health literacy refers to making informed decisions, gathering the data needed to address a health issue, obtaining relevant information, evaluating its quality, and choosing the best way to apply it[14]. The idea of health literacy has grown, and it now covers more than just being able to read and write [15]. Health literacy combines interactive health promotion skills and reading and writing competence. It is the ability to access, interpret, and use fundamental health information and services to promote health [16].

Epidemiologic surveys of HL in different parts of the world and among different ethnic groups with widely varying marital habits, socioeconomic status, and environment help understand its frequency in specific areas and its predisposing factors [12]. Adolescents and youth learn healthy habits and behaviors; therefore, suitable treatments can reduce the negative effects of low HHL in this group. Teenagers and young people are more exposed to loud music and improper use of hands-free. This study explored how an educational intervention affects ear and hearing-related health literacy in boys from Sanandaj.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This experimental study was conducted in Sanandaj, west of Iran, in 2021. Schools were selected by random cluster sampling from two districts (in terms of socio-economic context) of Sanandaj so that eight high schools were selected from districts. Ten students from each school were randomly selected from the list of all students. Based on Martin et al.'s study, who reported a 30% increase in awareness (as the proportion of the desired outcome in the intervention group), and considering a confidence interval of 95%, a power of 20%, and the following formula, from each selected school, 40 students were randomly selected (40 cases per group):

n=(z1-α/2+z1-β)2 [p1q1+p2q2]/(p1-p2)2

(z1-α/2+z1-β)2=7.85

Where, P1 represents the proportion of the desired outcome in the intervention group (30%) and P2 is the proportion of the desired outcome in the control group (10%); assuming a 30% increase in the intervention group and 10% in the control groups, the minimum sample size was estimated to be 36 people in each group, and finally, 40 people were considered for each group.

Method

Inclusion criteria were having a smartphone, informed consent, and willingness to participate. Before the study, students were made aware of its goals. Also, parents and students signed consent forms. The ethics committee of the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences authorized the study (IR.MUK.REC.1400.101). The Kurdistan Education Department allowed the research to be performed in four male high schools. Intervention and control groups received self-reported questionnaires. Two weeks after the last educational session, the questionnaires were re-distributed among the intervention and control groups.

Research tools

The required data were obtained using a researcher-made questionnaire. The content and face validity of the questionnaire were checked using the viewpoints of six experts related to the health fields of hearing and health education. Using a literature review based on the general framework of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adolescents (TOFHLA) (13, 14) as well as ear and hearing-related health literacy (7, 15-19), the primary items of the instrument were collected. The primary items were developed to include the three skills of applying hearing health information, communicating, and comprehension and evaluation. After preparing the initial version of the questionnaire, which had 44 questions, 39 items were confirmed based on content and face validity. These 39 questions contained three questions about demographic information, 14 questions about the ability to apply hearing health information, 13 questions about communicating skills, and 12 questions about comprehension and evaluation skills. The content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) were computed. To determine the CVR, items with the range (necessary, not essential, but useful, not necessary) were reviewed according to the Lawshe table, and items with a CVR value greater than 0.99 were preserved. To calculate the CVI, questions with a CVI greater than 0.7 were retained using Waltz and Bausell's CVI. According to Cronbach's alpha, the questionnaire's general validity and reliability were 0.84% and 0.86%, respectively. The three domains were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree). A score of 100 was given to always/strongly agree, 75 to often agree, 50 to sometimes/relatively agree, 25 for rarely disagree, and zero to never or strongly disagree.

Intervention

This study was conducted online due to the spread of COVID-19. Educational programs were implemented through WhatsApp and groups named "School Research Team" were formed separately for each of the intervention schools on this app. A pre-post-test was considered, the students were given instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. The intervention group received six sessions of 50-65 minutes of virtual education. The educational content contained topics about ear and hearing-related health literacy [17-21]. The topics included information about the ear and auditory system, noise and its effect on the hearing system, symptoms of HL, preventive recommendations, dangers of personal listening devices, symptoms that may be an early indication of HL (e.g. tinnitus), and some methods of reducing mental conflicts. The educational interventions also aimed at informing students of the measures that can be taken to reduce exposure to loud sounds, such as reducing the volume and time of exposure, reducing unsafe exposure to sounds, and giving advice for safe listening in accordance with the listening safe guideline (WHO) [22]. This intervention also addressed the relationship between normative or incorrect attitudes as well as peer effects on reducing the likelihood of music-induced HL. Educational videos, audio files, pamphlets, educational slides, and educational tracts were used as educational material. Education was presented with an interval of one week to allow questions and mutual feedback. The control group received no educational sessions but received the educational pamphlets after the administration of the final follow-up questionnaires.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 23 software and described by descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequency, mean, and standard deviation. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables between the two study groups. A significance level of less than 0.05 was considered.

Findings

The average age of students in the intervention and control groups was 14.08±0.83 and 14.08±0.83 years, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of age (p=0.054), grade (p=0.014), and the source of students' hearing information (p=0.94).

The frequency distribution of students' answers to the related hearing health literacy questions before and after the intervention is shown in Tables 1 and 2. After the intervention, hearing health literacy improved and increased significantly in all areas. Before the intervention, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the mean score of the students in the domains of ear and hearing-related health literacy (applying hearing health information, communicating, and comprehension and evaluation; p>0.05).

Table 1) Students' mean scores for comprehension and evaluation skills before and after the intervention in the intervention group

Table 2) Frequency of the intervention group students' responses to questions about applying hearing health information and communicating skills before and after the intervention

After the intervention, the mean score of applying hearing health information in the intervention group was 56.9±11.9, which was significantly higher than the control group (28.4±13.2), and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). Also, the mean score of communicating skills and comprehension and evaluation in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the control group (p<0.001). Unlike the control group, after the educational program, the ear and hearing-related health literacy scores of the intervention group improved, and the difference between the scores before and after the intervention was significant (p<0.001). Table 3 shows the comparison of the mean scores of ear and hearing-related health literacy during the pre-test to the post-test.

Table 3) Comparison of mean scores (range: 0-100) of ear and hearing-related health literacy from pre-test to post-test

Discussion

Hearing health literacy has been studied in an effort to gain a greater understanding of it. No study has investigated hearing health literacy programs for Iranian boys. Our findings may provide detailed information for health promotion planners regarding hearing-related health literacy and appropriate interventions. The results of this research may have critical implications beyond the creation of interventions to enhance the auditory and hearing health of Iranian students. Many younger individuals, for instance, inaccurately attribute HL to old age. Another example is that if a person's right earrings, it is a sign of receiving happy news, and for the left ear, it is a sign of receiving bad news in Iranian culture. After the intervention, a significant proportion of the students' perceptions positively changed in this regard, and they perceived ear ringing as a sign of HL (before the intervention, 5% of students agreed, which after it, reached 29%). Understanding the frequency of HL in specific areas and among specific ethnic groups with widely varying habits, sociocultural status, and environment is aided by global and ethnically diverse HL prevalence surveys, which also contribute to general knowledge about the predisposing factors of HL [23, 24]. Iran is a Muslim country, and in this cultural environment, the existence of dance clubs is prohibited. As a result, young people may try to experience pleasures that have normative limits with music players that are very loud and change their intensity in short intervals. Their interest is experiencing excitement and they are either unaware of its consequences or do not take its consequences seriously. The percentage of agreement with the negative consequences of changing the sound intensity increased from 5% to 32%.

Users of portable listening devices report them as a means of modulating their emotional states [25-27]. The loud volume of music, as a component of teenage culture, acts as a symbol of transgression and estrangement from an older generation [7]. As a distinguishing characteristic of teenage identity or as a potent stimulant for mood alteration, loud music is enjoyed and tolerated more by adolescents and young adults than by children and older people [25, 28]; listening to loud music is a popular pastime among today's youth as a means of relieving stress [25]. The current intervention program advises students to address their mental conflicts by seeking guidance and counseling from healthcare professionals and parents instead of listening to loud music. Several techniques were also instructed to reduce mental dissonance. Asking a doctor for advice to get rid of mental conflicts, instead of listening to loud music improved from 28% to 39%, resulting in an improvement of 11%. The results offer insights into the personal factors that affect adolescents' use of loud music as a means of regulating their emotions. The implementation of educational interventions led to noteworthy enhancements in the intervention group's comprehension and evaluation, communication, and ability to apply hearing health information skills in comparison to the control group. These findings are in line with previous studies that have demonstrated the notable impact of education on students' attitudes, perceptions, intentions, and motivation concerning recreational noise exposure [29]. Other research findings indicated that educational programs in the field of hearing protection had a positive impact on the knowledge levels of students and teens [23, 29-31]. Young adults and teenagers may not be aware of the risks associated with noise (30). According to research by Seedat et al., more than a quarter of health science students thought they would not need to worry about tinnitus or HL until they were much older. Their research indicated that a significant proportion of students in the health sciences field held the belief that concerns regarding tinnitus or HL would not be relevant until a later stage in life. Specifically, more than 25% of the participants expressed this viewpoint [32]. Therefore, if people are educated, they might be able to prevent unfavorable outcomes associated with their hearing health. This shows the importance of making the public informed about the importance of protecting their hearing [33-35].

False beliefs about peer behavior are an example of a socially normative issue that must be addressed in any intervention [36, 37]. Adolescents have no social motivation to minimize their exposure if they think all of their peers are listening loudly. Therefore, we paid attention to the influences of normative views and peers in the education program. For example, discussing the consequences of high-decibel noise with peers, talking about the harmful effects of loud noise with friends, and telling peers that good hearing means not having a hearing problem were included in the curriculum. In addition, discussing the dangers of loud decibels with peers, warning them that good hearing is not indicative of no hearing impairment, and telling peers that good hearing is not indicative of no hearing impairment were included in education programs.

No similar study explored the HHL domains in Iran, except for a cross-sectional by Shams et al. [3]. Due to the questionnaire's similarities, some of the present study's findings are compared to that study. Before the instruction, the mean HHL scores of the intervention and control groups were 39.7±8.5 and 40.1±6.2, respectively. Shams et al. found a mean HHL score of 30.81±3.75 among a sample of 4890 Iranian youth [3]. Our findings confirmed their findings that students were weak in comprehension and evaluation, communication, and hearing health information application. Shams et al. revealed that women had a significantly higher degree of adequate HHL compared to men. However, insufficient HHL was reported by both genders. Because our study was an intervention on male students, the effect of gender on HHL cannot be compared to the study by Shams et al. The prevalence of HL in the population of adolescents and young adults in Iran is generally low [3]. These findings suggest that young Iranians (12-25 years old) may be at risk for developing ear and hearing problems. As such, these findings highlight the need for considering all dimensions of health literacy when designing interventions that improve HHL among young Iranians. Differences in the study's methodology make it difficult to derive public health implications. Nevertheless, the integration of these initiatives into our training programs promises to increase the effectiveness of the hearing training program.

Our findings demonstrated that virtual education increased ear and hearing-related health literacy in school students. Therefore, interpersonal interactive educational interventions are more successful and continue longer than internet-based education, and they can effectively improve school students' hearing health literacy [38]. Adolescent interventions should be monitored over time to ensure that improvements in hearing health literacy are maintained.

Conclusion

Education enhances hearing-related health literacy. Young people in Iran have a generally poor knowledge of ear and hearing health. The findings of our study indicate that maintaining a healthy ear should be prioritized and appropriate measures should be taken to prevent this non-contagious health issue. Our results show that protecting healthy hearing and preventing this non-communicable disease should be a top priority. Our six sessions of instructional interventions improve schoolchildren's ear and hearing health literacy. This result may contribute to future studies and intervention development.

Acknowledgments: This article is the result of Sina Golmohamadi's master's thesis in the field of health education and health promotion entitled “The effect of a school-based intervention on boys' ear and hearing-related health literacy in Sanandaj, Iran”. The authors would like to thank the students and schools that made this study possible.

Ethical Permission: This article was derived from a research project approved by the Research and Technology Deputy of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUK.REC.1400.101).

Authors’ Contribution: Golmohamadi S (First Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Bahmani A (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Taymoori P (Third Author), Methodologist/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Bahrami M (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%)

Conflicts of interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Funding/Support: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Communication

Received: 2023/05/26 | Accepted: 2023/07/3 | Published: 2023/07/20

Received: 2023/05/26 | Accepted: 2023/07/3 | Published: 2023/07/20

References

1. National Library of Medicine. Hearing loss and deafness: Normal hearing and impaired hearing [Internet]. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2015 May- [cited 2023 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390300/ [Link]

2. Moradi G, Mostafavi F, Hajizadeh M, Amerzade M, Bolbanabad AM, Alinia C, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in different types of disabilities in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(3):427-34. [Link]

3. Shams M, Farhadi M, Maleki M, Shariatinia S, Mahmoudian S. Ear and hearing-related health literacy status of iranian adolescent and young people: A national study. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2020;25(1):43-53. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/sjku.25.1.43]

4. Stansfeld S, Clark C. Health effects of noise exposure in children. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2(2):171-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40572-015-0044-1]

5. Sharifian Alborzi M, Naderi S, Jafari Z, Tabatabai SM. The effect of listening to music on young personal listening device users. Sci J Rehabil Medi. 2015;4(4):80-8. [Persian] [Link]

6. Afshari M, Khazaei S, Bahrami M, Merati H. Investigating adult health literacy in Tuyserkan city. J Educ Community Health. 2014;1(2):48-55. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.20286/jech-010248]

7. Portnuff CD. Reducing the risk of music-induced hearing loss from overuse of portable listening devices: understanding the problems and establishing strategies for improving awareness in adolescents. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:27-35. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/AHMT.S74103]

8. Muchnik C, Amir N, Shabtai E, Kaplan-Neeman R. Preferred listening levels of personal listening devices in young teenagers: Self reports and physical measurements. Int J Audiol. 2012;51(4):287-93. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/14992027.2011.631590]

9. Pienkowski M. Loud music and leisure noise is a common cause of chronic hearing loss, tinnitus and hyperacusis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4236. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18084236]

10. Feder K, Marro L, McNamee J, Michaud D. Prevalence of loud leisure noise activities among a representative sample of Canadians aged 6-79 years. J Acoust Soc Am. 2019;146(5):3934-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1121/1.5132949]

11. Hussain T, Chou C, Zettner E, Torre P, Hans S, Gauer J, et al. Early indication of noise-induced hearing loss in young adult users of personal listening devices. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127(10):703-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0003489418790284]

12. Al-Mendalawi MD. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among Iranian deaf children: The first report from Iran. J Clin Neonatol. 2015;4(2):150. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2249-4847.154550]

13. Brach C, Harris LM. Healthy people 2030 health literacy definition tells organizations: Make information and services easy to find, understand, and use. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(4):1084-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11606-020-06384-y]

14. Robatsarpooshi D, Tavakoly Sany SB, Alizadeh Siuki H, Peyman N. Assessment of health literacy studies in Iran: Systematic review. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2019;25(6):793-807. [Persian] [Link]

15. Esposito L, Chiappero‐Martinetti E. Eliciting, applying and exploring multidimensional welfare weights: Evidence from the field. Rev Income Wealth. 2019;65(S1):S204-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/roiw.12407]

16. Liu C, Wang D, Liu C, Jiang J, Wang X, Chen H, et al. What is the meaning of health literacy? a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(2):e000351. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/fmch-2020-000351]

17. Bakshi SS, Kalidoss VK, Ramesh S, Shankar MK. How harmful is your personal listening device: A knowledge and attitude survey among college-going students of India. Saudi J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;23(1):41. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/sjoh.sjoh_55_20]

18. Gilles A. Effectiveness of a preventive campaign for noise-induced hearing damage in adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(4):604-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.01.009]

19. Crandell C, Mills TL, Gauthier R. Knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes about hearing loss and hearing protection among racial/ethnically diverse young adults. J National Med Assoc. 2004;96(2):176-86. [Link]

20. Levey S, Fligor BJ, Ginocchi C, Kagimbi L. The effects of noise-induced hearing loss on children and young adults. Contemporary Issue Communicat Sci Disord. 2012;39:76-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1044/cicsd_39_F_76]

21. Diviani N, Zanini C, Amann J, Chadha S, Cieza A, Rubinelli S. Awareness, attitudes, and beliefs about music-induced hearing loss: Towards the development of a health communication strategy to promote safe listening. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(8):1506-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2019.03.013]

22. World Health Organization. Toolkit for Safe Listening Devices and Systems. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Link]

23. Keppler H, Dhooge I, Vinck B. Hearing in young adults. Part II: The effects of recreational noise exposure. Noise Health. 2015;17(78):245-52. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1463-1741.165026]

24. Bennett A. Cultures of popular music. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2001. [Link]

25. Skånland MS. Everyday music listening and affect regulation: The role of MP3 players. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2013;8(1):20595. [Link] [DOI:10.3402/qhw.v8i0.20595]

26. Linnemann A, Ditzen B, Strahler J, Doerr JM, Nater UM. Music listening as a means of stress reduction in daily life. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:82-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.008]

27. De Witte M, Spruit A, van Hooren S, Moonen X, Stams GJ. Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: A systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health Psychol Rev. 2020;14(2):294-324. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17437199.2019.1627897]

28. Epstein JS. Adolescents and their music: If it's too loud, you're too old. Oxfordshire: Routledge; 2016. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9781315622590]

29. Sameni SJ, Rahbar N, Soleimani M, Soltanparast S, Pourbakht A. The impact of hearing preservation education on the young adults' listening behavior. Auditory Vestibular Res. 2022;32(1). [Link] [DOI:10.18502/avr.v32i1.11320]

30. Dell SM, Holmes AE. The effect of a hearing conservation program on adolescents' attitudes towards noise. Noise Health. 2012;14(56):39-44. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1463-1741.93333]

31. Keppler H, Ingeborg D, Sofie D, Bart V. The effects of a hearing education program on recreational noise exposure, attitudes and beliefs toward noise, hearing loss, and hearing protector devices in young adults. Noise Health. 2015;17(78):253-62. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1463-1741.165028]

32. Seedat R, Ehlers R, Lee Y, Mung'omba C, Plaatjies K, Prins M, et al. Knowledge of the audiological effects, symptoms and practices related to personal listening devices of health sciences students at a South African university. J Laryngol Otol. 2020;134(1):20-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0022215120000092]

33. Danhauer JL, Johnson CE, Byrd A, DeGood L, Meuel C, Pecile A, et al. Survey of college students on iPod use and hearing health. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20(1):5-27. [Link] [DOI:10.3766/jaaa.20.1.2]

34. Santana BA, Alvarenga KdF, Cruz PC, Quadros IAd, Jacob Corteletti LCB. Prevention in a school environment of hearing loss due to leisure noise. Audiol Commun Res. 2016;21. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/2317-6431-2015-1641]

35. Chung JH, Des Roches CM, Meunier J, Eavey RD. Evaluation of noise-induced hearing loss in young people using a web-based survey technique. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):861-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1542/peds.2004-0173]

36. Widén SE, Erlandsson SI. Risk perception in musical settings- a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health and Well-being. 2007;2(1):33-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17482620601121169]

37. Gilliver M, Carter L, Macoun D, Rosen J, Williams W. Music to whose ears? the effect of social norms on young people's risk perceptions of hearing damage resulting from their music listening behavior. Noise Health. 2012;14(57):47-51. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1463-1741.95131]

38. Martin WH, Griest SE, Sobel JL, Howarth LC. Randomized trial of four noise-induced hearing loss and tinnitus prevention interventions for children. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:S41-9. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/14992027.2012.743048]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |