Volume 11, Issue 3 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(3): 447-454 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yunanto R, Susanto T, Hairrudin H, Indriana T, Rahmawati I, Nistiandani A. A Community-Based Program for Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle Among Farmers in Indonesia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (3) :447-454

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-69120-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-69120-en.html

1- Department of Emergency and Critical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Jember, Jember, Indonesia

2- Department of Community, Family & Geriatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

3- Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

4- Department of Biomedicine, Faculty of Dentistry, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

5- Departement of Maternal and Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

6- Department of Medical and Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

2- Department of Community, Family & Geriatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

3- Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

4- Department of Biomedicine, Faculty of Dentistry, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

5- Departement of Maternal and Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

6- Department of Medical and Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Jember, Jember, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 899 kb]

(3378 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1441 Views)

Figure 2) The Transtheoretical Model-Lead Intervention to promote healthy life among farmers in Indonesia

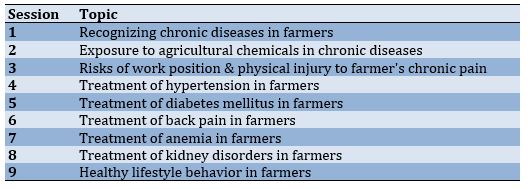

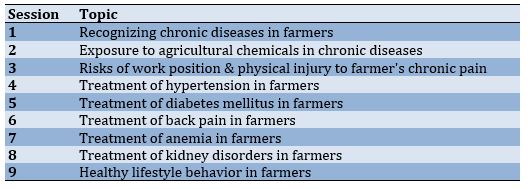

Table 1) The intervention topics

Measurement

The outcome measure was assessed at baseline (pre-test) and at week 24 (post-test). The measurement instrument had two sections. The first section assessed the demographic information of the participants (age, gender, ethnic group, history of diseases of the cardiovascular or urinary systems, hypertension status, education, allergy history, body weight, body height, abdominal circumference, and waist circumference). Physical indicators, such as weight (kg), height (centimeter), waist (WC), and hip circumference (HC) were measured according to standards. Meanwhile, the second part consisted of six questionnaires: (1) an organophosphate pesticide exposure questionnaire; (2) a questionnaire on knowledge, attitude, and behavior of general health conditions of farmers; (3) a nutrition knowledge questionnaire; (4) a Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ); (5) a Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WRUSS-21) questionnaire; and (6) a Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) questionnaire.

The organophosphate pesticide exposure questionnaire was used to assess the characteristics of exposure to pesticides in agricultural workers. This questionnaire consists of 37 questions to explore (1) labor conditions during the application of organophosphates; (2) use of personal protective equipment (PPE); (3) workplace conditions related to organophosphate exposure, and (4) home conditions related to organophosphate exposure. The maximum score of each questionnaire was 54 points. A higher score indicates a greater risk of exposure to pesticides and health effects. Questions answered as 'not applicable' scored zero (0) [21].

The knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding farmers’ general health conditions were measured using a structured questionnaire from previous research. This questionnaire consisted of three parts: (1) knowledge about pesticides (15 items); (2) attitude in using pesticides (13 items); and (3) practice regarding farmers’ general health conditions (13 items). For the knowledge about pesticides, farmers were asked to answer all 15 questions. Each correct answer was given a score of one, while incorrect and missing values were given a score of zero. Attitude to using pesticides was scored on a four-point Likert scale from one (totally disagree) to four (totally agree). Meanwhile, practice regarding farmers' general health condition was scored on a five-point Likert scale from one (never) to five (always). This questionnaire has been tested for validity and reliability with a Cronbach's alpha of >0.6. The total scores of the three parts of the questionnaire are then summed and the maximum potential score obtained is 132 [22].

The nutritional knowledge of farmers was assessed using a validated General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. This questionnaire consists of four domains: (1) advice from health experts (11 items), (2) food groups and food sources (71 items), (3) food choices (12 items), and (4) diet-disease (22 items). Farmers were asked to answer all questions. Each correct answer is given a score of one, while incorrect and missing values are given a score of zero. Subscale scores are calculated for each domain. The total scores of the four domains are then summed and the maximum potential score obtained is 116 [23].

The NMQ is a simple, standardized questionnaire that is used to detect and analyze musculoskeletal symptoms felt by individuals in various parts of the body. It has 28 items covering the body regions from top to bottom, such as "Have you at any time during the last 12 months had trouble (ache, pain, discomfort) in: ...", followed by a list and body diagram. The respondent then filled in each part of the body that felt sick. The score is from zero to three depending on the intensity of pain felt by the farmer. The total scores of the NMQ are then summed ranging from 0-81. The higher the score obtained, the higher the musculoskeletal problems experienced by farmers [24].

The WRUSS-21 questionnaire was used to assess respiratory symptoms in farmers. Its 19 items are valid and reliable. This questionnaire measures ten specific symptoms, including runny nose, stuffy nose, sneezing, sore throat, scratchy throat, cough, hoarseness, stuffy head, chest congestion, and fatigue. Nine functional items are also covered to assess the ability to think clearly, sleep well, breathe easily, exercise, work inside and outside the home, complete daily activities, interact with others, and lead a personal life. All items are scored on an eight-point Likert scale: zero (no or no impairment), one (very mild), three (mild), five (moderate), and seven (severe) [25, 26].

The MBI-GS questionnaire was used to measure the burnout syndrome experienced by farmers. This questionnaire was developed with items of emotional exhaustion (nine questions), depersonalization (five questions), and decreased personal achievement (eight questions). It consisted of 22 items scored on a seven-point Likert scale (0=never, 1=several times a year, 2=once a month or less, 3=several times a month, 4=once a week, 5=several times a week, and 6=every day). This questionnaire was proven to be valid and reliable based on the results of the previous studies (r>0.05) [27, 28].

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the raw data were screened for accuracy and normality. A descriptive statistic was used for the characteristics of the respondents (age, gender, ethnic group, history of diseases of the cardiovascular or urinary systems, hypertension status, education, allergy history, body weight, body height, abdominal circumference, and waist size). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the distribution of variables. Normally distributed variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD), and those with no normal distribution are presented as the median and interquartile range (P25-P75).

An intra-group comparison using the paired t-test was carried out on the organophosphate pesticide exposure, knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers about general health conditions of farmers, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory symptoms, and burnout of farmers to test the effectiveness of the CP2HL program performed before and after follow-up. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess the effectiveness of CP2HL intervention adjusted for education, duration of hypertension, and baseline measurement. Adjustment measures were determined taking into account the important factors related to the results based on a review of the literature. The comparison results were corrected using the Bonferroni test.

Ethical considerations

This study considered ethical feasibility as an important aspect of research. The researchers guarantee that in carrying out the research process, research respondents had the right to either participate or object to participating in the research process. They provided verbal and/or written consent and the principle of respondents’ information confidentiality was observed. This research was carried out after the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Jember approved the research proposal under the number 1753/UN25.8/KEPK/DL/2022.

Findings

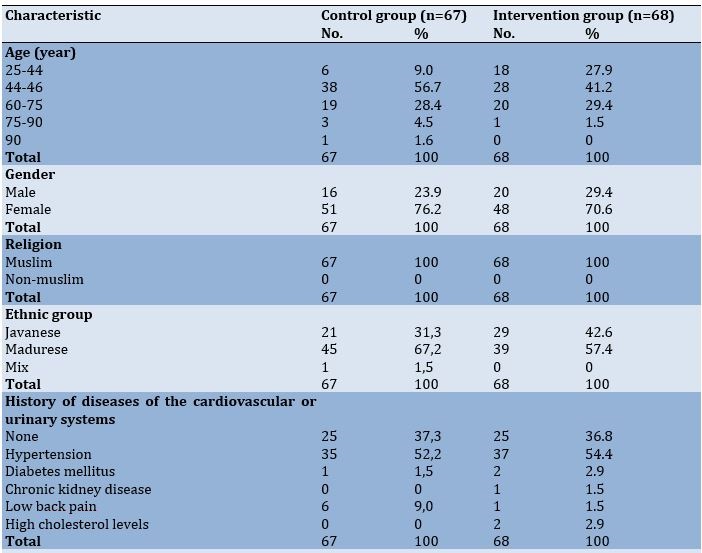

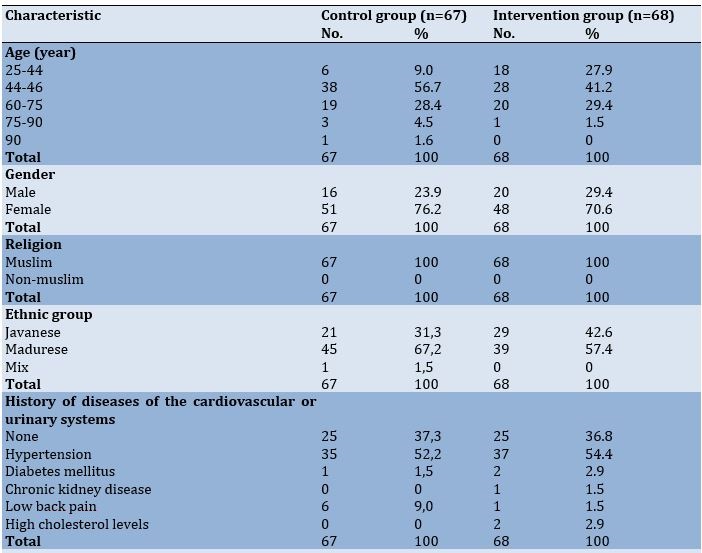

Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics of the participants. The participants of the CON (n=67) and INT (n=68) groups were mostly Muslim middle-aged female farmers. Most participants were Madurese (CON: 67.2% and INT: 57.4%). Furthermore, most respondents had hypertension (CON: 52.2% and INT: 54.4%) for less than five years (31.3% and 26.5%). The majority of the respondents only finished elementary school (59.7% and 58.8%). Participants in the CON and INT groups had a mean body weight of 51.6 and 54.7 kg, a height of 151.7 and 152.6cm, abdominal circumference of 84.4 and 86.7 cm, and waist circumference of 92.5 and 92.6 cm, respectively.

Table 2) Baseline participants’ characteristics

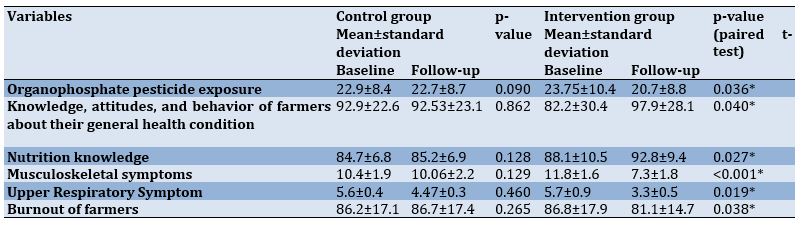

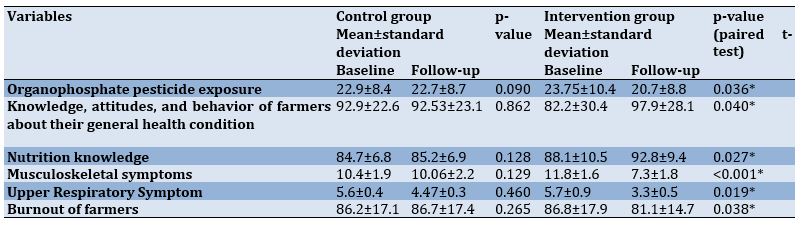

Table 3 presents the analysis results of the differences between the intervention and control groups regarding the dependent variables. There was no significant difference in organophosphate pesticide exposure before and after the procedure in the CON group (p-value=0.090). However, there was a significant difference before and after the procedure in the INT group (p-value=0.036). There was no significant difference between the CON and INT groups in farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about their general health conditions before and after the procedure (CON: p-value=0.862; INT: p-value=0.040). Similar results were obtained for the nutrition knowledge (CON: p-value=0.128; INT: p-value=0.027), musculoskeletal symptoms (CON: p-value=0.129; INT p-value=<0.001), upper respiratory infection symptoms (CON: p-value=0.460; INT: p-value=0.019), and farmer burnout (CON: p-value=0.265; INT: p-value=0.038).

Table 3) Changes in the control and intervention group after 24 weeks of intervention

Analyses of the intervention effectiveness after adjusting for education, duration of hypertension, and baseline measurement, revealed significant differences between the CON and INT groups in organophosphate pesticide exposure, Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers about general their health condition, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory symptoms, and burnout of farmers (Table 4).

Table 4) Comparison of the final adjusted mean scores according to group

Discussion

The current study concluded that CP2HL is effective in modifying farmers’ healthy lifestyles. The CP2HL carried out to promote a healthy lifestyle among farmers was able to provide significant changes in organophosphate pesticide exposure, knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory infection symptoms, and farmers’ burnout, respectively. During the 20-week follow-up period, the improvement rate of farmers’ healthy lifestyles in the intervention group was greater than that in the control group.

Farmers' exposure to organophosphate pesticides experienced better improvement after the intervention. On the other hand, the exposure to organophosphate pesticides in the intervention group was lower than that in the control group. This change shows that the CP2HL implemented on farmers had a significant effect on promoting farmers' safe behavior in using pesticides. Implementation of the CP2HL intervention for farmers for 24 weeks was effective, as evidenced by a reduction in post-test scores, indicating a reduction in pesticide exposure for farmers. Some previous studies conducted among Egyptian pesticide users with a focus on behavior change have shown an increase in awareness of the dangers of pesticides and using PPE after the intervention [29]. Other studies have also stated that implementing interventions to reduce pesticide exposure could be generally effective if focusing on participants’ education or behavior [30]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce pesticide exposure experienced by farmers.

The knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers about their general health conditions also improved. Farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in the intervention group were higher than that in the control group. Thus, the implementation of the CP2HL intervention was effective, as evidenced by the increase in the post-test scores, showing that the farmer’s knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding health increased. Previous research revealed that the intervention had an impact on increasing farmers’ knowledge as a whole. Meanwhile, the greatest increase in behavior as a result of the intervention was targeted at farmers who faced many farm health problems [31]. Other studies have also conducted interventions regarding health in general as well as pre- and post-tests indicating significant changes in farmers’ basic health knowledge [32]. This shows that community-based program interventions for promoting a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to improve farmers' knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding health in general.

Farmers’ nutrition knowledge after CP2HL also improved. Based on the results, nutrition knowledge in the intervention group was higher than that in the control group. Therefore, the implementation of the CP2HL intervention was effective as proven by an increase in the post-test scores.t. Previous studies have shown that nutritional knowledge interventions are effective in improving farmers' nutritional knowledge as seen in the increased percentage of correct answers after nutrition education [33]. This shows that the community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) are effective and can be used to increase farmers’ nutrition knowledge.

Musculoskeletal symptoms felt by farmers after CP2HL also decreased. Musculoskeletal symptoms of farmers in the intervention group were lower than in the control group. This is because the CP2HL intervention was effective as evidenced by the decrease in the post-test scores, which means that the muscle pain experienced by farmers subsided. There was a decrease in musculoskeletal complaints after farmers received interventions, such as stretching activities accompanied by ergonomic-based health education [34, 14]. Other studies also have found that interventions are effective in physical conditions and in preventing pain and injury [35]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce musculoskeletal symptoms in farmers.

CP2HL also positively affected the upper respiratory infection symptoms in farmers. Based on these results, upper respiratory disorders among farmers in the intervention group were lower than those in the control group. This is because the CP2HL intervention was effective as evidenced by a decrease in the post-test scores, indicating that the farmers' upper respiratory problems had subsided. Farmers easily experience upper respiratory infection symptoms due to pesticide exposure. The used interventions were effective in reducing upper respiratory infection symptoms by providing ongoing outreaches and training programs about potential health risks as well as hygienic and safety behaviors [36]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce the upper respiratory infection symptoms felt by farmers.

Farmers’ burnout also decreased after CP2HL. CP2HL can be said to be effective as evidenced by a decrease in the post-test scores, which means that burnout experienced by farmers subsided. Mental health interventions carried out among farmers by combining physical and mental health education resulted in significant changes in farmers’ physical and mental health and their lifestyles that could reduce burnout [32]. Earlier interventions carried out by educating people on mental health literacy and social-related activities reduced farmers’ burnout [37, 38]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce farmers’ burnout.

Conclusion

The CP2HL carried out to promote a healthy lifestyle among farmers was able to significantly influence organophosphate pesticide exposure, farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory infection symptoms, and farmers’ burnout. It can be concluded that CP2HL interventions can promote and significantly improve farmers’ healthy lifestyles.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their deepest appreciation to the Faculty of Nursing of the University of Jember, the Institute for Research and Community Service of the University of Jember, the nurses in the public health centers in Jember, and the farmers in the rural areas of Jember Regency, Indonesia for their invaluable support and contribution in the completion of this research.

Ethical Permission: This research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Jember (1753/UN25.8/KEPK/DL/2022).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Yunanto RA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (35%); Susanto T (Second Author), Methodologist/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Hairrudin H (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (10%); Indriana T (Fourth Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (10%); Rahmawati I (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%); Nistiandani A (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by the Kementerian Riset, Teknologi dan Pendidikan Tinggi (Ministry of Research, Technology & Higher Education (RISTEK-DIKTI); IDB 2022).

Full-Text: (315 Views)

Introduction

The development of biotechnology in agriculture has had many impacts on farmers' lives, both positive impacts on agricultural output and negative impacts on farmers' health. Negative impacts that can arise on the health of farmers are related to the use of biotechnology products to increase productivity, such as pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and other chemicals in supporting agricultural productivity. Exposure to chemicals with frequent intensity to farmers certainly affects the health status of the farmers, their family members, and the community. In addition, this condition is supported by the inadequate knowledge, attitudes, and behavior patterns of Indonesian farmers in safely use of biotechnology in the agricultural sector [1-7].

The use of chemicals, such as organophosphates in the long term will have a direct poisoning effect and cause chronic diseases in farmers [8, 9]. These health problems are not limited to one kind of chronic disease but also include cardiovascular problems [10], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [11], as well as negative effects on pregnancy that can eventually cause congenital defects [12]. Research conducted on farmers in the agricultural area of Jember Indonesia shows that most farmers experience chronic diseases, such as hypertension, vascular problems, heart problems, respiratory problems, muscle and spinal disorders, and anemia [13, 14]. Some of the factors that have been analyzed and become the cause of this health problem include ignorance of prevention, lack of motivation, and the inability of farmers to control exposure to the agrochemicals they use. Chronic diseases that have been suffered by farmers require changes in appropriate healthcare so that farmers' quality of life can be enhanced by addressing risk factors for exposure to controllable chemicals [15].

The Indonesian government through the Ministry of Health has made efforts to facilitate treatment for people with chronic diseases through the Posbindu PTM (Integrated Non-Communicable Disease Development Program) program in all parts of Indonesia. The program has been implemented in 50.6% of villages throughout Indonesia, but the prevalence of chronic disease risk factors is still increasing [16]. Evaluation of the inhibiting factors that contribute to this problem includes the lack of follow-up by the health team conducted by medical/paramedical personnel for Posbindu PTM participants so that so far participants only receive treatment when the program is implemented once a month. Treatment in this way will have less impact on changes in health problems experienced by people with chronic diseases in the community [17]. A specific intervention is needed to change the behavior of people with chronic diseases in carrying out healthcare independently and reduce the risk of exposure to agents that can exacerbate their illness. Therefore, it is necessary to make a change to obtain maximum results in influencing the health behavior of farmers who suffer from chronic diseases to live optimally.

Strategies that can be devised to change farmers' knowledge and behavior so that they can adopt a healthy lifestyle are integrating health education activities, supervision, follow-up, assistance in achieving the main goal of healthy living and strengthening skills to implement a healthy lifestyle [18]. The transtheoretical model (TTM) is a strategy that meets the activity criteria. TM is one of the activity methods that is widely used in changing the behavior of an individual or the behavior of a group. TTM has been proven to be able to change the behavior of a person or group of people based on an adaptation process that allows progressive change to occur [18, 19]. Five steps can be done in this process, including pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance [20]. This study aimed to analyze the effect of the community-based program in promoting a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) using the TTM approach to Indonesian farmers.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study employed a randomized control trial (RCT) based on community program interventions and was conducted From May to November 2022. We conducted this research in four public health centers in Indonesia (Panti, Sukorambi, Banjarsengon, and Pakusari).

Participants

The population of this study was active farmers suffering from chronic non-communicable diseases at four public health centers in Indonesia. The sample size was calculated using G*Power with a statistical significance level of 0.05.. Using an effect size of 0.25 and a power of 0.80, 130 farmers were selected, and considering a 10% increase in the number of samples, 143 participants were recruited to prevent a significant dropout. The research sample was divided into two groups: The intervention group (INT; CP2HL; n=72) and the control group (CON; receiving the intervention according to the community health center service program; n=71). The inclusion criteria were: (1) working as a farmer (owning land or being a farmworker), (2) being in a designated Posbindu area, (3) suffering from a chronic cardiovascular disease and/or kidney disease, and (4) willing to sign a consent form to participate in our research. After 24 weeks of intervention, four participants in each group did not continue the intervention due to health and personal reasons. At the end of the intervention, the number of participants was 135: (CON: n=67 and INT: n=68; Figure 1).

Figure 1) Consort flow diagram.

Intervention

This study was conducted for 24 weeks, with the intervention performed at weeks 1-4 and follow-ups performed at weeks 5-24 in four public health centers in Jember (Sukorambi, Panti, Banjarsengon, and Pakusari). The INT group received a farmer's health service program to influence their behavior with a transtheoretical model-based community intervention program approach. TTM consists of several stages: (1) pre-contemplation; (2) contemplation; (3) preparations; (4) action, and (5) maintenance (Figure 2). We conducted a series of outreaches and training for respondents on the topics compiled in a guidebook (Table 1). The outreaches and training were carried out in nine sessions over four weeks. Each session lasted for 180 minutes under the direct supervision of the researchers and the team. After the training process, the respondents directly practiced healthcare for chronic diseases while being assisted for 19 weeks. We assessed the respondents at the beginning and the end of the intervention. The CON group received regular care from the non-communicable diseases integrated development program in the Public Health Center in Jember.

The development of biotechnology in agriculture has had many impacts on farmers' lives, both positive impacts on agricultural output and negative impacts on farmers' health. Negative impacts that can arise on the health of farmers are related to the use of biotechnology products to increase productivity, such as pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and other chemicals in supporting agricultural productivity. Exposure to chemicals with frequent intensity to farmers certainly affects the health status of the farmers, their family members, and the community. In addition, this condition is supported by the inadequate knowledge, attitudes, and behavior patterns of Indonesian farmers in safely use of biotechnology in the agricultural sector [1-7].

The use of chemicals, such as organophosphates in the long term will have a direct poisoning effect and cause chronic diseases in farmers [8, 9]. These health problems are not limited to one kind of chronic disease but also include cardiovascular problems [10], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [11], as well as negative effects on pregnancy that can eventually cause congenital defects [12]. Research conducted on farmers in the agricultural area of Jember Indonesia shows that most farmers experience chronic diseases, such as hypertension, vascular problems, heart problems, respiratory problems, muscle and spinal disorders, and anemia [13, 14]. Some of the factors that have been analyzed and become the cause of this health problem include ignorance of prevention, lack of motivation, and the inability of farmers to control exposure to the agrochemicals they use. Chronic diseases that have been suffered by farmers require changes in appropriate healthcare so that farmers' quality of life can be enhanced by addressing risk factors for exposure to controllable chemicals [15].

The Indonesian government through the Ministry of Health has made efforts to facilitate treatment for people with chronic diseases through the Posbindu PTM (Integrated Non-Communicable Disease Development Program) program in all parts of Indonesia. The program has been implemented in 50.6% of villages throughout Indonesia, but the prevalence of chronic disease risk factors is still increasing [16]. Evaluation of the inhibiting factors that contribute to this problem includes the lack of follow-up by the health team conducted by medical/paramedical personnel for Posbindu PTM participants so that so far participants only receive treatment when the program is implemented once a month. Treatment in this way will have less impact on changes in health problems experienced by people with chronic diseases in the community [17]. A specific intervention is needed to change the behavior of people with chronic diseases in carrying out healthcare independently and reduce the risk of exposure to agents that can exacerbate their illness. Therefore, it is necessary to make a change to obtain maximum results in influencing the health behavior of farmers who suffer from chronic diseases to live optimally.

Strategies that can be devised to change farmers' knowledge and behavior so that they can adopt a healthy lifestyle are integrating health education activities, supervision, follow-up, assistance in achieving the main goal of healthy living and strengthening skills to implement a healthy lifestyle [18]. The transtheoretical model (TTM) is a strategy that meets the activity criteria. TM is one of the activity methods that is widely used in changing the behavior of an individual or the behavior of a group. TTM has been proven to be able to change the behavior of a person or group of people based on an adaptation process that allows progressive change to occur [18, 19]. Five steps can be done in this process, including pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance [20]. This study aimed to analyze the effect of the community-based program in promoting a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) using the TTM approach to Indonesian farmers.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study employed a randomized control trial (RCT) based on community program interventions and was conducted From May to November 2022. We conducted this research in four public health centers in Indonesia (Panti, Sukorambi, Banjarsengon, and Pakusari).

Participants

The population of this study was active farmers suffering from chronic non-communicable diseases at four public health centers in Indonesia. The sample size was calculated using G*Power with a statistical significance level of 0.05.. Using an effect size of 0.25 and a power of 0.80, 130 farmers were selected, and considering a 10% increase in the number of samples, 143 participants were recruited to prevent a significant dropout. The research sample was divided into two groups: The intervention group (INT; CP2HL; n=72) and the control group (CON; receiving the intervention according to the community health center service program; n=71). The inclusion criteria were: (1) working as a farmer (owning land or being a farmworker), (2) being in a designated Posbindu area, (3) suffering from a chronic cardiovascular disease and/or kidney disease, and (4) willing to sign a consent form to participate in our research. After 24 weeks of intervention, four participants in each group did not continue the intervention due to health and personal reasons. At the end of the intervention, the number of participants was 135: (CON: n=67 and INT: n=68; Figure 1).

Figure 1) Consort flow diagram.

Intervention

This study was conducted for 24 weeks, with the intervention performed at weeks 1-4 and follow-ups performed at weeks 5-24 in four public health centers in Jember (Sukorambi, Panti, Banjarsengon, and Pakusari). The INT group received a farmer's health service program to influence their behavior with a transtheoretical model-based community intervention program approach. TTM consists of several stages: (1) pre-contemplation; (2) contemplation; (3) preparations; (4) action, and (5) maintenance (Figure 2). We conducted a series of outreaches and training for respondents on the topics compiled in a guidebook (Table 1). The outreaches and training were carried out in nine sessions over four weeks. Each session lasted for 180 minutes under the direct supervision of the researchers and the team. After the training process, the respondents directly practiced healthcare for chronic diseases while being assisted for 19 weeks. We assessed the respondents at the beginning and the end of the intervention. The CON group received regular care from the non-communicable diseases integrated development program in the Public Health Center in Jember.

Figure 2) The Transtheoretical Model-Lead Intervention to promote healthy life among farmers in Indonesia

Table 1) The intervention topics

Measurement

The outcome measure was assessed at baseline (pre-test) and at week 24 (post-test). The measurement instrument had two sections. The first section assessed the demographic information of the participants (age, gender, ethnic group, history of diseases of the cardiovascular or urinary systems, hypertension status, education, allergy history, body weight, body height, abdominal circumference, and waist circumference). Physical indicators, such as weight (kg), height (centimeter), waist (WC), and hip circumference (HC) were measured according to standards. Meanwhile, the second part consisted of six questionnaires: (1) an organophosphate pesticide exposure questionnaire; (2) a questionnaire on knowledge, attitude, and behavior of general health conditions of farmers; (3) a nutrition knowledge questionnaire; (4) a Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ); (5) a Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WRUSS-21) questionnaire; and (6) a Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) questionnaire.

The organophosphate pesticide exposure questionnaire was used to assess the characteristics of exposure to pesticides in agricultural workers. This questionnaire consists of 37 questions to explore (1) labor conditions during the application of organophosphates; (2) use of personal protective equipment (PPE); (3) workplace conditions related to organophosphate exposure, and (4) home conditions related to organophosphate exposure. The maximum score of each questionnaire was 54 points. A higher score indicates a greater risk of exposure to pesticides and health effects. Questions answered as 'not applicable' scored zero (0) [21].

The knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding farmers’ general health conditions were measured using a structured questionnaire from previous research. This questionnaire consisted of three parts: (1) knowledge about pesticides (15 items); (2) attitude in using pesticides (13 items); and (3) practice regarding farmers’ general health conditions (13 items). For the knowledge about pesticides, farmers were asked to answer all 15 questions. Each correct answer was given a score of one, while incorrect and missing values were given a score of zero. Attitude to using pesticides was scored on a four-point Likert scale from one (totally disagree) to four (totally agree). Meanwhile, practice regarding farmers' general health condition was scored on a five-point Likert scale from one (never) to five (always). This questionnaire has been tested for validity and reliability with a Cronbach's alpha of >0.6. The total scores of the three parts of the questionnaire are then summed and the maximum potential score obtained is 132 [22].

The nutritional knowledge of farmers was assessed using a validated General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. This questionnaire consists of four domains: (1) advice from health experts (11 items), (2) food groups and food sources (71 items), (3) food choices (12 items), and (4) diet-disease (22 items). Farmers were asked to answer all questions. Each correct answer is given a score of one, while incorrect and missing values are given a score of zero. Subscale scores are calculated for each domain. The total scores of the four domains are then summed and the maximum potential score obtained is 116 [23].

The NMQ is a simple, standardized questionnaire that is used to detect and analyze musculoskeletal symptoms felt by individuals in various parts of the body. It has 28 items covering the body regions from top to bottom, such as "Have you at any time during the last 12 months had trouble (ache, pain, discomfort) in: ...", followed by a list and body diagram. The respondent then filled in each part of the body that felt sick. The score is from zero to three depending on the intensity of pain felt by the farmer. The total scores of the NMQ are then summed ranging from 0-81. The higher the score obtained, the higher the musculoskeletal problems experienced by farmers [24].

The WRUSS-21 questionnaire was used to assess respiratory symptoms in farmers. Its 19 items are valid and reliable. This questionnaire measures ten specific symptoms, including runny nose, stuffy nose, sneezing, sore throat, scratchy throat, cough, hoarseness, stuffy head, chest congestion, and fatigue. Nine functional items are also covered to assess the ability to think clearly, sleep well, breathe easily, exercise, work inside and outside the home, complete daily activities, interact with others, and lead a personal life. All items are scored on an eight-point Likert scale: zero (no or no impairment), one (very mild), three (mild), five (moderate), and seven (severe) [25, 26].

The MBI-GS questionnaire was used to measure the burnout syndrome experienced by farmers. This questionnaire was developed with items of emotional exhaustion (nine questions), depersonalization (five questions), and decreased personal achievement (eight questions). It consisted of 22 items scored on a seven-point Likert scale (0=never, 1=several times a year, 2=once a month or less, 3=several times a month, 4=once a week, 5=several times a week, and 6=every day). This questionnaire was proven to be valid and reliable based on the results of the previous studies (r>0.05) [27, 28].

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the raw data were screened for accuracy and normality. A descriptive statistic was used for the characteristics of the respondents (age, gender, ethnic group, history of diseases of the cardiovascular or urinary systems, hypertension status, education, allergy history, body weight, body height, abdominal circumference, and waist size). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the distribution of variables. Normally distributed variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD), and those with no normal distribution are presented as the median and interquartile range (P25-P75).

An intra-group comparison using the paired t-test was carried out on the organophosphate pesticide exposure, knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers about general health conditions of farmers, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory symptoms, and burnout of farmers to test the effectiveness of the CP2HL program performed before and after follow-up. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess the effectiveness of CP2HL intervention adjusted for education, duration of hypertension, and baseline measurement. Adjustment measures were determined taking into account the important factors related to the results based on a review of the literature. The comparison results were corrected using the Bonferroni test.

Ethical considerations

This study considered ethical feasibility as an important aspect of research. The researchers guarantee that in carrying out the research process, research respondents had the right to either participate or object to participating in the research process. They provided verbal and/or written consent and the principle of respondents’ information confidentiality was observed. This research was carried out after the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Jember approved the research proposal under the number 1753/UN25.8/KEPK/DL/2022.

Findings

Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics of the participants. The participants of the CON (n=67) and INT (n=68) groups were mostly Muslim middle-aged female farmers. Most participants were Madurese (CON: 67.2% and INT: 57.4%). Furthermore, most respondents had hypertension (CON: 52.2% and INT: 54.4%) for less than five years (31.3% and 26.5%). The majority of the respondents only finished elementary school (59.7% and 58.8%). Participants in the CON and INT groups had a mean body weight of 51.6 and 54.7 kg, a height of 151.7 and 152.6cm, abdominal circumference of 84.4 and 86.7 cm, and waist circumference of 92.5 and 92.6 cm, respectively.

Table 2) Baseline participants’ characteristics

Table 3 presents the analysis results of the differences between the intervention and control groups regarding the dependent variables. There was no significant difference in organophosphate pesticide exposure before and after the procedure in the CON group (p-value=0.090). However, there was a significant difference before and after the procedure in the INT group (p-value=0.036). There was no significant difference between the CON and INT groups in farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about their general health conditions before and after the procedure (CON: p-value=0.862; INT: p-value=0.040). Similar results were obtained for the nutrition knowledge (CON: p-value=0.128; INT: p-value=0.027), musculoskeletal symptoms (CON: p-value=0.129; INT p-value=<0.001), upper respiratory infection symptoms (CON: p-value=0.460; INT: p-value=0.019), and farmer burnout (CON: p-value=0.265; INT: p-value=0.038).

Table 3) Changes in the control and intervention group after 24 weeks of intervention

Analyses of the intervention effectiveness after adjusting for education, duration of hypertension, and baseline measurement, revealed significant differences between the CON and INT groups in organophosphate pesticide exposure, Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers about general their health condition, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory symptoms, and burnout of farmers (Table 4).

Table 4) Comparison of the final adjusted mean scores according to group

Discussion

The current study concluded that CP2HL is effective in modifying farmers’ healthy lifestyles. The CP2HL carried out to promote a healthy lifestyle among farmers was able to provide significant changes in organophosphate pesticide exposure, knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory infection symptoms, and farmers’ burnout, respectively. During the 20-week follow-up period, the improvement rate of farmers’ healthy lifestyles in the intervention group was greater than that in the control group.

Farmers' exposure to organophosphate pesticides experienced better improvement after the intervention. On the other hand, the exposure to organophosphate pesticides in the intervention group was lower than that in the control group. This change shows that the CP2HL implemented on farmers had a significant effect on promoting farmers' safe behavior in using pesticides. Implementation of the CP2HL intervention for farmers for 24 weeks was effective, as evidenced by a reduction in post-test scores, indicating a reduction in pesticide exposure for farmers. Some previous studies conducted among Egyptian pesticide users with a focus on behavior change have shown an increase in awareness of the dangers of pesticides and using PPE after the intervention [29]. Other studies have also stated that implementing interventions to reduce pesticide exposure could be generally effective if focusing on participants’ education or behavior [30]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce pesticide exposure experienced by farmers.

The knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of farmers about their general health conditions also improved. Farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in the intervention group were higher than that in the control group. Thus, the implementation of the CP2HL intervention was effective, as evidenced by the increase in the post-test scores, showing that the farmer’s knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding health increased. Previous research revealed that the intervention had an impact on increasing farmers’ knowledge as a whole. Meanwhile, the greatest increase in behavior as a result of the intervention was targeted at farmers who faced many farm health problems [31]. Other studies have also conducted interventions regarding health in general as well as pre- and post-tests indicating significant changes in farmers’ basic health knowledge [32]. This shows that community-based program interventions for promoting a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to improve farmers' knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding health in general.

Farmers’ nutrition knowledge after CP2HL also improved. Based on the results, nutrition knowledge in the intervention group was higher than that in the control group. Therefore, the implementation of the CP2HL intervention was effective as proven by an increase in the post-test scores.t. Previous studies have shown that nutritional knowledge interventions are effective in improving farmers' nutritional knowledge as seen in the increased percentage of correct answers after nutrition education [33]. This shows that the community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) are effective and can be used to increase farmers’ nutrition knowledge.

Musculoskeletal symptoms felt by farmers after CP2HL also decreased. Musculoskeletal symptoms of farmers in the intervention group were lower than in the control group. This is because the CP2HL intervention was effective as evidenced by the decrease in the post-test scores, which means that the muscle pain experienced by farmers subsided. There was a decrease in musculoskeletal complaints after farmers received interventions, such as stretching activities accompanied by ergonomic-based health education [34, 14]. Other studies also have found that interventions are effective in physical conditions and in preventing pain and injury [35]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce musculoskeletal symptoms in farmers.

CP2HL also positively affected the upper respiratory infection symptoms in farmers. Based on these results, upper respiratory disorders among farmers in the intervention group were lower than those in the control group. This is because the CP2HL intervention was effective as evidenced by a decrease in the post-test scores, indicating that the farmers' upper respiratory problems had subsided. Farmers easily experience upper respiratory infection symptoms due to pesticide exposure. The used interventions were effective in reducing upper respiratory infection symptoms by providing ongoing outreaches and training programs about potential health risks as well as hygienic and safety behaviors [36]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce the upper respiratory infection symptoms felt by farmers.

Farmers’ burnout also decreased after CP2HL. CP2HL can be said to be effective as evidenced by a decrease in the post-test scores, which means that burnout experienced by farmers subsided. Mental health interventions carried out among farmers by combining physical and mental health education resulted in significant changes in farmers’ physical and mental health and their lifestyles that could reduce burnout [32]. Earlier interventions carried out by educating people on mental health literacy and social-related activities reduced farmers’ burnout [37, 38]. This shows that community-based program interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle (CP2HL) can be used to reduce farmers’ burnout.

Conclusion

The CP2HL carried out to promote a healthy lifestyle among farmers was able to significantly influence organophosphate pesticide exposure, farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior, nutrition knowledge, musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory infection symptoms, and farmers’ burnout. It can be concluded that CP2HL interventions can promote and significantly improve farmers’ healthy lifestyles.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their deepest appreciation to the Faculty of Nursing of the University of Jember, the Institute for Research and Community Service of the University of Jember, the nurses in the public health centers in Jember, and the farmers in the rural areas of Jember Regency, Indonesia for their invaluable support and contribution in the completion of this research.

Ethical Permission: This research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Jember (1753/UN25.8/KEPK/DL/2022).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Yunanto RA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (35%); Susanto T (Second Author), Methodologist/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Hairrudin H (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (10%); Indriana T (Fourth Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher (10%); Rahmawati I (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%); Nistiandani A (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: This research was funded by the Kementerian Riset, Teknologi dan Pendidikan Tinggi (Ministry of Research, Technology & Higher Education (RISTEK-DIKTI); IDB 2022).

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2023/05/14 | Accepted: 2023/08/26 | Published: 2023/09/18

Received: 2023/05/14 | Accepted: 2023/08/26 | Published: 2023/09/18

References

1. Sapbamrer R. Pesticide use, poisoning, and knowledge and unsafe occupational practices in Thailand. New Solut. 2018;28(2):283-302. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1048291118759311]

2. Öztaş D, Kurt B, Koç A, Akbaba M, Ilter H. Knowledge level, attitude, and behaviors of farmers in çukurova region regarding the use of pesticides. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6146509. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2018/6146509]

3. Sibel C, Babaoglu UT, Bakar C. Evaluating pesticide use and safety practices among farmworkers in Gallipoli. Southeast Asian J Tropical Med Public Health. 2011;46(1):143-54. [Link]

4. van der Hoek W, Konradsen F, Athukorala K, Wanigadewa T. Pesticide poisoning: A major health problem in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(4-5):495-504. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00193-7]

5. Chowdhury AN, Banerjee S, Brahma A, Weiss MG. Pesticide practices and suicide among farmers of the Sundarban region in India. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28(2 suppl):381-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/15648265070282S218]

6. Cole DC, Orozco T F, Pradel W, Suquillo J, Mera X, Chacon A, et al. An agriculture and health inter-sectorial research process to reduce hazardous pesticide health impacts among smallholder farmers in the Andes. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(2 suppl):S6. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1472-698X-11-S2-S6]

7. Colémont A, Van den Broucke S. Measuring determinants of occupational health related behavior in flemish farmers: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J Safety Res. 2008;39(1):55-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsr.2007.12.001]

8. Zhang X, Zhao W, Jing R, Wheeler K, Smith GA, Stallones L, et al. Work-related pesticide poisoning among farmers in two villages of Southern China: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:429. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-11-429]

9. Toe AM, Ouedraogo M, Ouedraogo R, Ilboudo S, Guissou PI. Pilot study on agricultural pesticide poisoning in Burkina Faso. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2013;6(4):185-91. [Link] [DOI:10.2478/intox-2013-0027]

10. Sekhotha MM, Monyeki KD, Sibuyi ME. Exposure to agrochemicals and cardiovascular disease: A review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(2):229. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph13020229]

11. Fontana L, Lee SJ, Capitanelli I, Re A, Maniscalco M, Mauriello MC, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in farmers. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(8):775-88. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001072]

12. Chowdhary AN, Banerjee S, Brahma A, Biswas MK. Pesticide poisoning in nonfatal , deliberate self-harm : A public health issue. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(2):25-8. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.33259]

13. Susanto T, Purwandari R, Wuri Wuryaningsih E. Prevalence and associated factors of health problems among Indonesian farmers. Chinese Nurs Res. 2017;4(1):31-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cnre.2017.03.008]

14. Susanto T, Rahmawati I, Wantiyah. Community-based occupational health promotion programme: An initiative project for Indonesian agricultural farmers. Health Educ. 2020;120(1):73-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/HE-12-2018-0065]

15. Park YH, Chang H. Effect of a health coaching self-management program for older adults with multimorbidity in nursing homes. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:959-70. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S62411]

16. Rahadjeng E, Nurhotimah E. Evaluasi pelaksanaan posbindu penyakit tidak menular (Posbindu Ptm) di lingkungan tempat tinggal. J Ekologi Kesehatan. 2020;19(2):134-47. [Link] [DOI:10.22435/jek.v19i2.3653]

17. Andayasari L, Opitasari C. Implementasi program pos pembinaan terpadu penyakit tidak menular di provinsi jawa barat Tahun 2015. J Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pelayanan Kesehatan. 2020;3(3):168-81. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.22435/jpppk.v3i3.2713]

18. Wang L, Chen H, Lu H, Wang Y, Liu C, Dong X, et al. The effect of transtheoretical model-lead intervention for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: A cluster randomized trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):134. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13075-020-02222-y]

19. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38-48. [Link] [DOI:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38]

20. Hashemzadeh M, Rahimi A, Zare-Farashbandi F, Alavi-Naeini A, Daei A. Transtheoretical model of health behavioral change: A systematic review. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2019;24(2):83-90. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_94_17]

21. Muñoz-Quezada MT, Lucero B, Bradman A, Baumert B, Iglesias V, Muñoz MP, et al. Reliability and factorial validity of a questionnaire to assess organophosphate pesticide exposure to agricultural workers in Maule, Chile. Int J Environ Health Res. 2019;29(1):45-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09603123.2018.1508647]

22. ERMA S, Widi E. Pengaruh perilaku penggunaan pestisida terhadap kondisi kesehatan umum petani di kecamatan kalisat kabupaten Jember. Jember: Universitas Jember; 2020. [Link]

23. Parmenter K, Wardle J. Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53(4):298-308. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600726]

24. Ramdan IM, Duma K, Setyowati DL. Reliability and validity test of the indonesian version of the nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire (NMQ) to measure musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) in traditional women weavers. Global Med Health Commun. 2019;7(2). [Link] [DOI:10.29313/gmhc.v7i2.4132]

25. Barrett B. Rasch analysis of the WURSS-21 dimensional validation and assessment of invariance. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2016;3(2):00076. [Link] [DOI:10.15406/jlprr.2016.03.00076]

26. Barrett B, Brown RL, Mundt MP, Thomas GR, Barlow SK, Highstrom AD, et al. Validation of a short form Wisconsin upper respiratory symptom survey (WURSS-21). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:76. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-7-76]

27. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ editors. Evaluating stress: A book of resources. Lanham: Scarecrow Press; 1997. pp. 191-218. [Link]

28. Yulianto H. Maslach burnout inventory-human services survey (MBI-HSS) Versi Bahasa Indonesia: Studi Validasi Konstruk pada Anggota Polisi. J Pengukuran Psikologi dan Pendidikan Indonesia. 2020;9(1):19-29. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.15408/jp3i.v9i1.13329]

29. Röösli M, Fuhrimann S, Atuhaire A, Rother HA, Dabrowski J, Eskenazi B, et al. Interventions to reduce pesticide exposure from the agricultural sector in Africa: A workshop report. J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):8973. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19158973]

30. Afshari M, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Khoshravesh S, Besharati F. Effectiveness of interventions to promote pesticide safety and reduce pesticide exposure in agricultural health studies: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245766. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0245766]

31. Coman MA, Marcu A, Chereches RM, Leppälä J, van den Broucke S. Educational interventions to improve safety and health literacy among agricultural workers: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):1114. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17031114]

32. Hagen BNM, Albright A, Sargeant J, Winder CB, Harper SL, O'Sullivan TL, et al. Research trends in farmers' mental health: A scoping review of mental health outcomes and interventions among farming populations worldwide. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0225661. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0225661]

33. Bundala N, Kinabo J, Jumbe T, Rybak C, Stuetz W, Sieber S. A tailored nutrition education intervention improves women's nutrition knowledge and dietary practices in farming households of Tanzania. J Nutrit Health Food Sci. 2020;8(1):1-14. [Link] [DOI:10.15226/jnhfs.2020.001168]

34. Krismawati LDE, Dinata IMK, Sutjna DP, Adiputra LMISH, Griadhi PA. implementation of stretching exercise with ergonomic based health education approach to reduce musculoskeletal complaints and fatigue in orange farmers in Bayunggede village. J Res Community Serv. 2022;3(11):1031-45. [Link] [DOI:10.36418/dev.v3i11.211]

35. Volkmer K, Lucas Molitor W. Interventions addressing injury among agricultural workers: A systematic review. J Agromedicine. 2019;24(1):26-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1536573]

36. Mahawati E. Effect of safety and hygiene practices on lung function among Indonesian farmers exposed to pesticides. South East Eur J Public Health. 2022;2 [Link] [DOI:10.56801/seejph.vi.262]

37. Jones-Bitton A, Hagen B, Fleming SJ, Hoy S. Farmer burnout in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):5074. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16245074]

38. Susanto T, Purwandari R. Lifestyle and work situation to joint/bone pain and health status of non communicale diseases among Tobbacos' farmers at the rural area of Jember Regency, east Java province, Indonesia. 2nd International Nursing Conference Nursing Role for Sustainable Development Goal Achievement Based on Community Empowerment; 2015; Jember, Indonesia. School of Nursing, University of Jember; 2015. p. 95-101. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |