Volume 11, Issue 3 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(3): 389-398 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Saadati M, Kazemi F, Taheri S, Isfahani P, Afshari M. Virtual Learning Policies in Medical Sciences Universities during COVID-19; a Systematic Review. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (3) :389-398

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-69033-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-69033-en.html

1- Department of Health Sciences Management, School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Health Management, Faculty of Health Sciences, European University of Lefke, Lefke, Turkey

4- Department of Health Sciences Management, School of Public Health, Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Zabol, Iran

5- Department of Health Sciences Management, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Saveh University of Medical Sciences, Saveh, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Health Management, Faculty of Health Sciences, European University of Lefke, Lefke, Turkey

4- Department of Health Sciences Management, School of Public Health, Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Zabol, Iran

5- Department of Health Sciences Management, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Saveh University of Medical Sciences, Saveh, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 846 kb]

(3055 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1124 Views)

Full-Text: (373 Views)

Introduction

Crises can significantly impact societies' economic, environmental, and social aspects [1]. The first human cases of COVID-19 were identified in late December 2019 in Wuhan, China [2]. It then rapidly spread throughout the world [3]. COVID-19 is considered the biggest challenge the world has faced since World War II. South Korea, Italy, and Iran were among the countries significantly affected by COVID-19 shortly after China [4]. As a rapidly evolving condition, COVID-19 has affected entire populations and severely disrupted all aspects of life [5]. Reduced physical contact has been the most common strategy to prevent the spread of the pandemic worldwide, including the closure of schools/universities and restrictions on public transportation and travel [3, 6].

The educational system is one of the key areas affected by COVID-19 [6]. Universities worldwide reacted quickly to this crisis and announced immediate closure [7]. According to a 2020 UNESCO report, more than 1.5 billion students from 190 countries were affected by school and university closures at the peak of the crisis, with many institutions switching from face-to-face to online learning [8]. Medical schools and health-related disciplines have been more significantly impacted by COVID-19 due to their sensitive nature (e.g., high exposure of medical students in healthcare settings) [9]. In addition, time constraints, lack of healthcare resources, and poor support have further undermined education in healthcare settings [10]. No developed or developing country has been exempt from these fundamental changes [10]. Medical schools can make emergency arrangements that allow students to complete the semester remotely. In general, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted medical education, challenging the ability of medical faculty to adapt to this unique situation [9].

Most educational institutions worldwide have switched to e-learning in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic [11]. Specifically, medical schools quickly changed their entire curriculum to online formats [12]. Online education has traditionally faced resistance due to insufficient competence and institutional support. In addition, the nature of medical and health sciences requires a more practical and hands-on approach to education, and the practicality associated with face-to-face teaching methods may not be observable in a virtual online platform [6]. Among other challenges of virtual education in universities during the corona epidemic period, the following important issues can be mentioned: Insufficient skill of faculty members in using appropriate media, relative weakness of faculty members in using virtual resources, web-based technologies, online consulting services and technical supports, weakness in the faculty members' relative use of educational content production platforms in the virtual space, the poor condition of the available bandwidth in universities, the insufficient speed of development in the field of updating digital materials, and the lack of adaptation of the existing curriculum dimensions to virtual education [13]. In one study, most students (74.7%) agreed that COVID-19 has significantly disrupted their medical education [14]. The aggregation and integration of educational policies applied in medical schools around the world are necessary for evidence-based decision-making by educational policymakers to address these challenges [15].

On the other hand, Kalvani et al. investigated higher education scenarios after the COVID-19 crisis and the future strategic directions of education. They said that the epidemic of COVID-19 had a great impact on higher education; although online education was immediately after the epidemic, professors and universities were not prepared for it. This crisis will greatly impact higher education in the coming years. While the severity of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis is still unknown, higher education institutions are trying to understand the future of this industry. They seek extraordinary measures to deal with future events [16].

The sudden shift to e-learning without prior preparation created problems for medical science education that must be corrected. Also, the lessons learned are helpful for future epidemics or critical situations. If appropriate and effective solutions and interventions are used, there is a great chance to improve and expand the e-learning process. However, research that fully identifies the challenges of e-learning during the COVID-19 epidemic and extracts the interventions of different countries has not been done. Also, along with the challenges of this alternative educational method during the epidemic, there are several benefits for learners and teachers, whose identification can guide policymakers. Therefore, the present research aimed to identify the educational policies of medical schools during COVID-19.

Information and Methods

This systematic review was performed on virtual education policies in medical schools between December 2019 and January 10, 2022. This is done using the six-step protocol of Arksey & O’Malley [17]; (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant literature; (3) selecting studies; (4) mapping out the data; (5) summarizing, synthesizing, and reporting the results; and (6) consulting with experts regarding the findings.

This research focused on studies published in Persian and English on English databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) and Persian databases (SID and Magiran). Google Scholar was also searched to ensure access to relevant studies (Table 1). The following search terms and their Persian equivalents were searched along with appropriate Boolean(AND/OR) operators: “Medical education policies”, “policy-making process”, “COVID-19”, “policy”, “education”, and “covid”. Studies published in any language other than Persian or English, those published after January 10, 2022, and those for which the full text is unavailable were excluded. A total of 13,030 articles were extracted from the six databases. These studies were entered into EndNote 20. In the first stage, the abstracts and titles were reviewed by three researchers, and disagreements were resolved by a fourth reviewer. In total, 38 articles were included in this review. A checklist was developed to collect the information from the articles, including title, lead author, type of study, research method and tools, country, sample, findings, conclusions, and solutions. Qualitative data was analyzed using content analysis, and MAXQDA 10 was used to code the data and identify the underlying themes, patterns, and meanings. All ethical considerations in review research were observed in this study. The researchers took measures to avoid bias during the data collection, analysis, and reporting stages. The PRISMA-ScR checklist was used to report the findings [18].

Table 1. Database search strategies and the number of articles obtained from each database

Overall, 13,073 articles were extracted through the database search. After removing duplicates, 10756 studies remained for the title and abstract screening, of which 10688 were also removed, resulting in 36 articles on educational policies in medical schools during COVID-19. After carefully reviewing the remaining articles, 32 studies outside the field of educational policy were removed. Moreover, two additional articles were obtained from the reference lists of the articles. Finally, 38 articles were used in this research (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process

Findings

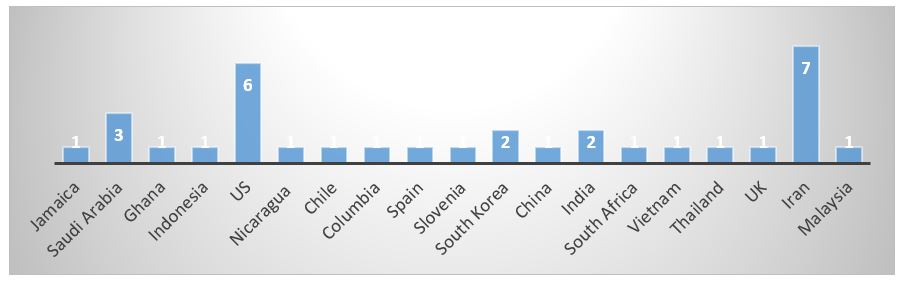

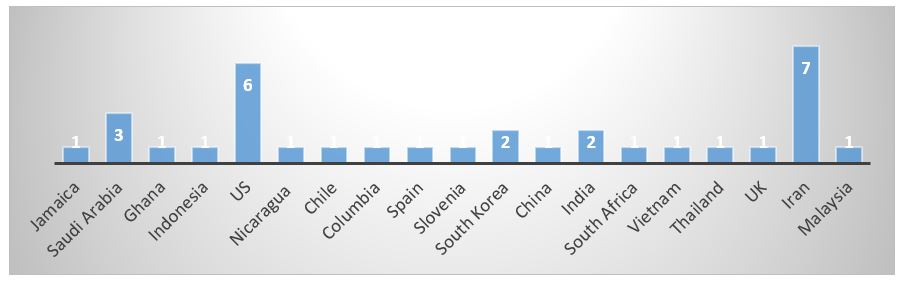

Of the 38 articles included in the review, 58% were conducted in 2020, 39% in 2021, and 3% in 2022. About 65.8% of the studies were cross-sectional, 18.4% were reviewed, 7.9% were editorial, and the rest were a survey, an interventional, and a trial study. Iran, the United States, and Saudi Arabia were the most common settings of the reviewed studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of studies on virtual education policies in medical schools during COVID-19 by setting.

The findings were categorized into five main domains, i.e., learner, teaching-learning process, technical infrastructure, instructor, and evaluation process. The advantages and challenges of virtual education were identified for each domain, along with solutions. Based on this classification, a model for virtual education policies in medical schools during COVID-19 is developed. Overall, 27 advantages, 34 challenges, 62, and solutions were identified (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Frequency distribution of challenges, solutions, and advantages of distance medical education during COVID-19.

Learner Domain

Challenges

The most important challenges in the learner domain were Students’ unfamiliarity with electronic systems that existed before the pandemic; students’ unpreparedness for e-learning, students’ poor technological skills; disruption of students’ work-life balance; students’ lack of motivation, anxiety, and social/psychological harm caused by the pandemic; students’ financial problems due to job loss; perceived ineffectiveness of e-learning and student dissatisfaction; and reduced opportunity to interact with patients. Medical students' most frequently cited challenges regarding e-learning during COVID-19 were anxiety and social/psychological damage caused by the pandemic (5 studies) and students’ poor technological skills (4 studies).

Solutions

The most important solutions in the learner dimension were Redefining the culture of professionalism and altruism for medical and non-medical students; issuing certificates and licenses for students who volunteer to work in various departments; setting a schedule for students’ stay in the dormitory and issuing licenses for practical and clinical; providing financial aid to disadvantaged students (Tuition discount, free education, electronic equipment with the help of donors, free internet access with the cooperation of telecommunications companies, etc.); allowing students to withdraw from certain courses or the semester, providing personal protective equipment to medical teams and interns; allocating one bedroom to each student during exams; providing counseling and psychological support to students; developing appropriate meal plans and ensuring food security for students volunteering for clinical work; establishing ethical principles to increase academic and clinical competencies given the limited logistical resources; developing a multi-profession and cross-departmental training team; encouraging cooperation between public health students/graduates and different clinics/departments; creating safe retreats for students in hospitals; and using learner-centered andragogical approaches. The most frequently cited solutions for addressing students’ challenges were counseling and psychological support (7 studies) and providing financial aid to disadvantaged students (5 studies).

Advantages

The advantages of distance medical education for students during the COVID-19 epidemic were Reduced risk of getting sick; development of students’ technical and computer skills; increased classroom interactions among students without reticence; preparation of students for clinical rotations; consideration of students’ psychological and social status; consideration of students’ economic status; greater educational justice; improvement of the ethical environment and increased student resilience; improving students’ academic performance and increasing their motivation; improved student’s patient care and clinical skills; and increased learner independence and self-efficacy. The most frequently cited advantages in the learner domain were Consideration of students’ psychological and social status (5 studies), consideration of students’ economic status (4 studies), and development of students’ technical and computer skills (4 studies).

Teaching-Learning Process

Challenges

The challenges of distance medical education in this domain were as follows: Suspension of clinical rotation/practical programs and the slowing down of the learning process; reduced interaction between professors and students; lack of a clear and unified classroom policy; reduced learning quality; poor quality of the virtual education system; limited international experience due to unpreparedness of universities for the pandemic; compulsory e-learning and hasty introduction of related technologies; reduced access to educational content; high cost of Internet access; and concerns over security of personal information across platforms. The most frequently cited challenges in this domain were the suspension of clinical rotation/practical programs, the slowing down of the learning process (6 studies), and reduced interaction between professors and students (3 studies).

Solutions

Several interventions have been used worldwide to address the challenges associated with the teaching-learning process domain. The main interventions were virtualizing classes and classroom activities for both students and interns (19 studies); sustainable financing of distance medical education (3 studies); redefining the educational landscape, strategic planning, mission, values, goals, and plans to turn challenges into opportunities (3 studies); sustainable financing of distance medical education (2 studies); and postponing internships until COVID-19 is contained (2 studies). The most frequently cited intervention is virtualizing classes and educational activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of e-learning platforms that existed before the pandemic, building on previous remote learning experiences, the use of “virtual patient” technologies, development of digital laboratories and medical libraries, production of online/offline electronic content, and the combination of distance and face-to-face education were examples of solutions that medical schools have used to keep education going during the pandemic.

Advantages

The process of distance education has significant advantages such as: Strengthening management, leadership, and planning for future crises; continuity of education, cost-effectiveness; flexible access to educational material; ability to watch videos and revisit educational material without limitation; continuity of administrative work, albeit at a slow pace; the opportunity for cooperation and establishment of new councils that encourage participation by universities, students, and other stakeholders in the development of educational/clinical policies; greater creativity in educational management and implementation; development of medical education activities in the cyberspace and social media; the appeal of online scientific discussion; and development of research networks. The most frequently cited advantages were cost-effectiveness (4 studies), the development of medical education activities in cyberspace and social media (4 studies), flexible access to educational material (3 studies), and greater creativity in educational management and implementation (3 studies).

Technical Infrastructure Domain

Challenges

The most frequent challenges related to technical infrastructure were Low bandwidth and lack of seamless Internet connectivity (3 studies); time, personal protection equipment, and physical space constraints (2 studies); financial constraints (2 studies); and shortage of human resources (2 studies).

Solutions

The main solutions for addressing technical infrastructure challenges in distance medical education were Using alternative technologies to improve remote learning of anatomy and laboratory work, such as remote robotic microscopy, artificial intelligence, digital libraries, clinical simulation laboratories, and virtual haptic laboratory; developing an online IT support system to answer questions and solve technical problems; integrating online education technologies; using Adobe Connect to create and manage virtual classes; using various software programs to hold synchronous virtual classes, including Big Blue Button, Skype, Skyroom, and Zoom; using social media, academic websites, and video sharing platforms such as YouTube; enhancing servers; improving the security of systems and platforms; using various technologies and social media to streamline and optimize virtual conferences; assessing the di-agnostic skills of dentistry students by performing clinical procedures during examination; and clinical reasoning and critical thinking in the absence of clinical procedures. The most frequently cited technical intervention is using alternative technologies to improve remote learning of anatomy and laboratory work (5 studies).

Advantages

The technical infrastructure of distance medical education has two major advantages: The development of distance learning software and technologies such as artificial intelligence, telemedicine, simulation, and AI-assisted platforms (7 studies) and the reliability of e-learning technologies (2 studies).

Instructor Domain

Challenges

There were many challenges in teaching medical sciences electronically. The most important challenges instructors faced were unfamiliarity with electronic systems before the pandemic; poor technological skills; lack of motivation; and pedagogic barriers. The most frequently cited challenges were poor technological skills (4 studies) and lack of motivation (3 studies). During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical school faculty face technical challenges due to the sudden shift to online platforms and their lack of experience with online teaching methods. In addition, school closures and reduced interaction with students, other professors, and the faculty environment can lead to a loss of motivation.

Solutions

Effective interventions for addressing the challenges of the instructor domain were granting scholarships to faculty members with increased workload (e.g., those producing video lessons); using mentorship in online education; giving faculty members and educational groups the authority to decide on the volume of synchronous/asynchronous face-to-face and online training according to the nature of the course and the conditions of students/faculty members; providing training (Online, offline, face-to-face) on how to work with software and electronic infrastructure to faculty members who were less familiar with virtual education; developing content creation software to help instructors in preparing multimedia educational material; creating a website for teaching faculty members about distance education infrastructure and software; encouraging participation by faculty members in preparing electronic content and educational packages; communicating with faculty members to solve their issues and exchange information; conducting a needs assessment to control the quality of e-content by contacting students/trainees and preparing them before starting online learning programs; conducting research on e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of students and professors; and removing pedagogic barriers and redefining how the content is created and presented to students. The most frequently cited solutions were Conducting research on e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of students and professors (4 studies), and training faculty members (Online, offline, face-to-face) on how to work with software and electronic infrastructure (2 studies).

Advantages

The advantages of distance medical education in the instructor domain were the development of instructors’ technical and computer skills (4 studies) and the development of mentoring and coaching skills (2 studies). The interventions that medical schools have used to address the challenges of faculty members during COVID-19 have ultimately resulted in the development of professors' technical and technological skills in working with computers and distance learning software. Moreover, mentoring and coaching skills were considered in education to help students manage small groups.

Evaluation

Challenges

In the evaluation domain, the most important challenges of distance medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic were the lack of a clear and unified policy for conducting and grading online exams, the lack of tools to evaluate the effectiveness of distance education interventions for nursing or medical interns; and concerns about the integrity of online exams. The sudden cancellation of exams, uncertainty about how to evaluate students, the unintegrated approach to evaluation, and the lack of specific tools for measuring the interventions that have replaced face-to-face education were the most important challenges of distance medical education during COVID-19. Furthermore, the sudden shift to online exams and electronic evaluations has not given instructors the necessary confidence in their student evaluations.

Solutions

The main solutions to evaluation challenges in distance medical education were Conducting online exams; replacing face-to-face final exams with assignments, projects, and classroom activities; diversifying and changing teaching/evaluation methods; and allocating 30-50% of course credits to assignments, projects, and exercises and 50-70% to the final exams. The most important solution cited in five studies is to evaluate the number of uploaded contents, assignments and exercises, formative tests, the number of activities provided by instructors, the number of activities performed by students, and the number of feedbacks and exchanges with professors.

Advantages

The most important advantages of evaluation during COVID-19 were Reduced interval between evaluations, repeated evaluation of the activities of instructors and students, and the ability to evaluate medical education methods better.

Discussion

The spread of COVID-19 worldwide has required governments to take rapid and efficient preventive measures [2]. One of the important areas in this field is the continuity of education, especially medical training. In the wake of the pandemic, countries shifted from face-to-face to distance learning [11, 20-22]. For example, preventive policies initiated by the Chinese government were not limited to social distancing and school closures. The Chinese government implemented an emergency plan called “Suspending Classes Without Stopping Learning, " which means switching from traditional to online education [22].

The purpose of the present scoping review was to investigate the virtual education policies of medical schools during COVID-19. Between 2020 and 2022, 38 articles were published on this topic, from which 34 challenges, 62 solutions, and 27 advantages were identified and categorized into the five key domains: Learner, teaching-learning process, technical infrastructure, instructor, and evaluation. These domains and elements were then presented as a matrix titled the “Fabric of Virtual Medical Education Policies during the COVID-19 Pandemic”.

Nine challenges, 13 solutions, and 11 advantages were identified in the learner domain. One of the most important challenges in this domain is the anxiety and social/psychological damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A study in Malaysia found that students experienced significant anxiety levels during the pandemic and subsequent lockdown. In this study, the main stressors included financial constraints, remote online teaching, and uncertainty about the future with regard to academics [18]. Harries et al. reported that the pandemic moderately affected college students’ stress and anxiety levels, with 84.1 percent of respondents feeling at least somewhat anxious. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the education of US medical students in their clinical training years. Most students wished to return to clinical rotations and were willing to accept the risk of infection. Students were mostly concerned about having adequate personal protective equipment if allowed to return to clinical activities [14].

The results of the present study showed that educational systems should adopt e-learning policies and use reliable technology and communication tools in efficient online platforms to shift from traditional to web-based education in emergencies and increase learners’ access. To balance student safety and well-being with the time-sensitive need to train future physicians and paramedics, students must be made aware of the pressures on the healthcare system so that they can be more patient with the educational impacts of the pandemic [14].

Ten challenges, 49 solutions, and 11 advantages were identified in the teaching-learning process domain. The most frequently cited challenges were the suspension of clinical rotations and practical programs, the slowing down of the learning process, and the reduction of teacher-student interaction. Studies have shown that early in the pandemic, only the teaching platform was changed [23, 24]. Instead of shifting to virtual education, virtual education replaced face-to-face education with its traditional features and methods. In contrast, transitioning to virtual education requires specific goals, content, teaching methods, educational design, and evaluation methods.

Several suggestions have been made for improving the e-learning process. Using hybrid learning strategies, including practical/in-person clinical training, effectively improves the e-learning process [25]. Providing technical training to staff and students, having an exam policy in place for times when internet connectivity is disrupted (e.g., offering more time for completing exams and allowing multiple attempts), making greater use of videos for educational material, having an effective system that detects and prevents cheating, encouraging active interaction between the instructor and the learner [26], providing opportunities for online access to educational resources and open-source materials [27], supporting the instructional design and delivery mechanisms using set learning objectives including teaching strategies, and embedding feedback and evaluation [28] were other solutions for facilitating the learning process.

The present study identified eight challenges, ten solutions, and two advantages in the technical infrastructure domain. Among the challenges discussed were problems with Internet access and poor technology skills. In a study on the e-learning experience of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia, Al Zahrani identified inadequate tools to facilitate online learning, poor internet connection, and lack of technological skills by educators and students as the main challenges of e-learning [11].

Similarly, Alhassan found that health trainees were constrained by low bandwidth and lack of seamless Internet connectivity within their learning environments to take full advantage of e-learning opportunities [25]. The transition to online platforms has led to disparities in access to learning. While students may use their mobile phones to access resources, the type and capacity of the device can be problematic as there is not enough memory space to download the platforms used for learning. The battery life of these devices is also a limitation [29].

It is agreed that the success of e-learning programs depends largely on the learning tools and technical support available to users [30]. Moreover, appropriate technical support and maintenance of existing hardware and software are crucial to professors' and students' optimal use of technology [31, 32]. Each e-learning system builds a core set of computers, networks, communications, technical facilities, and IT professionals to maintain and continuously upgrade the system, train users, and provide technical support [33]. A good example is e-learning standards for higher education in Sau-di Arabia, which were made in accordance with leading international standards and include technology, training and support, design, interaction, equity and access, and assessment and evaluation [11].

Four challenges, 11 solutions, and two advantages were identified in the teacher domain. Among the challenges in this domain were Instructors’ unfamiliarity with the electronic systems that existed before the pandemic, poor technological skills, and lack of motivation. It must be noted that the active role of instructors and their responsiveness and feedback are crucial to student satisfaction with online education because the professor is the key element of success in the e-learning environment [34]. Sun et al. examined the instructors’ role in the success of e-learning by focusing on two specific indicators: the instructor’s response timeliness and attitude toward e-learning. They found a positive and significant relationship between these aspects and student satisfaction [35]. Similar findings were reported by Sideral et al. They documented a positive relationship between instructor attitudes toward e-learning and user satisfaction [36]. In addition, Al-Fraihat et al. found a positive relationship between instructor quality and students’ perceived satisfaction with the e-learning system [37].

A survey of 178 special needs students from different Indonesian universities showed that teaching presence, cognitive and social presence, and content quality directly and indirectly affect satisfaction with e-learning [38]. Providing online training for instructors, livestreaming classes, pre-recording lectures, facilitating discussions on an electronic platform, and providing assessment and feedback [39] can improve instructors’ ability to conduct online classes. Farajollahi et al. stress that the success of online learning is contingent upon both professors’ and students’ readiness to shift from traditional face-to-face learning to online learning [40].

This study identified three challenges, nine solutions, and two advantages in the evaluation domain. One of the main challenges is the lack of a clear and unified policy and a suitable tool for conducting and grading online exams. Studies show that the evaluation method significantly affects students’ approach to learning [41]. Providing formative feedback to students is essential to their learning as it provides guidance on student performance [42]. However, feedback has often been limited due to faculty and students being too busy transitioning to remote education. Other methods of providing meaningful feedback should also be considered, including audio or video and peer feedback, which can help reduce the burden while maintaining educational quality [43].

Stress and concerns caused by the pandemic and changes in learning/evaluation affect student performance, and high-stakes exams increase students’ anxiety levels [43]. In his research on undergraduate students, Cann discusses that students favor audio feedback over written feedback [44]. He also emphasizes that the content of the feedback is as important as its timeliness [44]. Therefore, it is possible to improve student performance by teaching instructors how important it is to provide feedback in evaluations [45].

Conclusion

Education in COVID-19 time should be distinguished from the normal state of affairs. As such, embracing flexibility while ensuring accountability is a priority. In other words, we must ensure that learning outcomes are achieved without covering the entire content of the curriculum (e.g., providing some practical sessions that must be canceled due to lockdown). The identified challenges can be overcome through a comprehensive hybrid model that includes simulation-based online training, reducing face-to-face training in practical courses, training learners and instructors to take advantage of existing platforms, upgrading the technical infrastructure, and improving virtual education processes.

Acknowledgments: Not applicable.

Ethical Permission: This study was conducted with approval from the Research Ethics Committee (IR.SAVEHUMS.REC.1401.015).

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Saadati M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (25%); Kazemi F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%); Taheri S (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Isfahani P (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/ Assistant Researcher (15%); Afshari M (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: Saveh University of Medical Sciences.

Crises can significantly impact societies' economic, environmental, and social aspects [1]. The first human cases of COVID-19 were identified in late December 2019 in Wuhan, China [2]. It then rapidly spread throughout the world [3]. COVID-19 is considered the biggest challenge the world has faced since World War II. South Korea, Italy, and Iran were among the countries significantly affected by COVID-19 shortly after China [4]. As a rapidly evolving condition, COVID-19 has affected entire populations and severely disrupted all aspects of life [5]. Reduced physical contact has been the most common strategy to prevent the spread of the pandemic worldwide, including the closure of schools/universities and restrictions on public transportation and travel [3, 6].

The educational system is one of the key areas affected by COVID-19 [6]. Universities worldwide reacted quickly to this crisis and announced immediate closure [7]. According to a 2020 UNESCO report, more than 1.5 billion students from 190 countries were affected by school and university closures at the peak of the crisis, with many institutions switching from face-to-face to online learning [8]. Medical schools and health-related disciplines have been more significantly impacted by COVID-19 due to their sensitive nature (e.g., high exposure of medical students in healthcare settings) [9]. In addition, time constraints, lack of healthcare resources, and poor support have further undermined education in healthcare settings [10]. No developed or developing country has been exempt from these fundamental changes [10]. Medical schools can make emergency arrangements that allow students to complete the semester remotely. In general, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted medical education, challenging the ability of medical faculty to adapt to this unique situation [9].

Most educational institutions worldwide have switched to e-learning in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic [11]. Specifically, medical schools quickly changed their entire curriculum to online formats [12]. Online education has traditionally faced resistance due to insufficient competence and institutional support. In addition, the nature of medical and health sciences requires a more practical and hands-on approach to education, and the practicality associated with face-to-face teaching methods may not be observable in a virtual online platform [6]. Among other challenges of virtual education in universities during the corona epidemic period, the following important issues can be mentioned: Insufficient skill of faculty members in using appropriate media, relative weakness of faculty members in using virtual resources, web-based technologies, online consulting services and technical supports, weakness in the faculty members' relative use of educational content production platforms in the virtual space, the poor condition of the available bandwidth in universities, the insufficient speed of development in the field of updating digital materials, and the lack of adaptation of the existing curriculum dimensions to virtual education [13]. In one study, most students (74.7%) agreed that COVID-19 has significantly disrupted their medical education [14]. The aggregation and integration of educational policies applied in medical schools around the world are necessary for evidence-based decision-making by educational policymakers to address these challenges [15].

On the other hand, Kalvani et al. investigated higher education scenarios after the COVID-19 crisis and the future strategic directions of education. They said that the epidemic of COVID-19 had a great impact on higher education; although online education was immediately after the epidemic, professors and universities were not prepared for it. This crisis will greatly impact higher education in the coming years. While the severity of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis is still unknown, higher education institutions are trying to understand the future of this industry. They seek extraordinary measures to deal with future events [16].

The sudden shift to e-learning without prior preparation created problems for medical science education that must be corrected. Also, the lessons learned are helpful for future epidemics or critical situations. If appropriate and effective solutions and interventions are used, there is a great chance to improve and expand the e-learning process. However, research that fully identifies the challenges of e-learning during the COVID-19 epidemic and extracts the interventions of different countries has not been done. Also, along with the challenges of this alternative educational method during the epidemic, there are several benefits for learners and teachers, whose identification can guide policymakers. Therefore, the present research aimed to identify the educational policies of medical schools during COVID-19.

Information and Methods

This systematic review was performed on virtual education policies in medical schools between December 2019 and January 10, 2022. This is done using the six-step protocol of Arksey & O’Malley [17]; (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant literature; (3) selecting studies; (4) mapping out the data; (5) summarizing, synthesizing, and reporting the results; and (6) consulting with experts regarding the findings.

This research focused on studies published in Persian and English on English databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) and Persian databases (SID and Magiran). Google Scholar was also searched to ensure access to relevant studies (Table 1). The following search terms and their Persian equivalents were searched along with appropriate Boolean(AND/OR) operators: “Medical education policies”, “policy-making process”, “COVID-19”, “policy”, “education”, and “covid”. Studies published in any language other than Persian or English, those published after January 10, 2022, and those for which the full text is unavailable were excluded. A total of 13,030 articles were extracted from the six databases. These studies were entered into EndNote 20. In the first stage, the abstracts and titles were reviewed by three researchers, and disagreements were resolved by a fourth reviewer. In total, 38 articles were included in this review. A checklist was developed to collect the information from the articles, including title, lead author, type of study, research method and tools, country, sample, findings, conclusions, and solutions. Qualitative data was analyzed using content analysis, and MAXQDA 10 was used to code the data and identify the underlying themes, patterns, and meanings. All ethical considerations in review research were observed in this study. The researchers took measures to avoid bias during the data collection, analysis, and reporting stages. The PRISMA-ScR checklist was used to report the findings [18].

Table 1. Database search strategies and the number of articles obtained from each database

Overall, 13,073 articles were extracted through the database search. After removing duplicates, 10756 studies remained for the title and abstract screening, of which 10688 were also removed, resulting in 36 articles on educational policies in medical schools during COVID-19. After carefully reviewing the remaining articles, 32 studies outside the field of educational policy were removed. Moreover, two additional articles were obtained from the reference lists of the articles. Finally, 38 articles were used in this research (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process

Findings

Of the 38 articles included in the review, 58% were conducted in 2020, 39% in 2021, and 3% in 2022. About 65.8% of the studies were cross-sectional, 18.4% were reviewed, 7.9% were editorial, and the rest were a survey, an interventional, and a trial study. Iran, the United States, and Saudi Arabia were the most common settings of the reviewed studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of studies on virtual education policies in medical schools during COVID-19 by setting.

The findings were categorized into five main domains, i.e., learner, teaching-learning process, technical infrastructure, instructor, and evaluation process. The advantages and challenges of virtual education were identified for each domain, along with solutions. Based on this classification, a model for virtual education policies in medical schools during COVID-19 is developed. Overall, 27 advantages, 34 challenges, 62, and solutions were identified (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Frequency distribution of challenges, solutions, and advantages of distance medical education during COVID-19.

Learner Domain

Challenges

The most important challenges in the learner domain were Students’ unfamiliarity with electronic systems that existed before the pandemic; students’ unpreparedness for e-learning, students’ poor technological skills; disruption of students’ work-life balance; students’ lack of motivation, anxiety, and social/psychological harm caused by the pandemic; students’ financial problems due to job loss; perceived ineffectiveness of e-learning and student dissatisfaction; and reduced opportunity to interact with patients. Medical students' most frequently cited challenges regarding e-learning during COVID-19 were anxiety and social/psychological damage caused by the pandemic (5 studies) and students’ poor technological skills (4 studies).

Solutions

The most important solutions in the learner dimension were Redefining the culture of professionalism and altruism for medical and non-medical students; issuing certificates and licenses for students who volunteer to work in various departments; setting a schedule for students’ stay in the dormitory and issuing licenses for practical and clinical; providing financial aid to disadvantaged students (Tuition discount, free education, electronic equipment with the help of donors, free internet access with the cooperation of telecommunications companies, etc.); allowing students to withdraw from certain courses or the semester, providing personal protective equipment to medical teams and interns; allocating one bedroom to each student during exams; providing counseling and psychological support to students; developing appropriate meal plans and ensuring food security for students volunteering for clinical work; establishing ethical principles to increase academic and clinical competencies given the limited logistical resources; developing a multi-profession and cross-departmental training team; encouraging cooperation between public health students/graduates and different clinics/departments; creating safe retreats for students in hospitals; and using learner-centered andragogical approaches. The most frequently cited solutions for addressing students’ challenges were counseling and psychological support (7 studies) and providing financial aid to disadvantaged students (5 studies).

Advantages

The advantages of distance medical education for students during the COVID-19 epidemic were Reduced risk of getting sick; development of students’ technical and computer skills; increased classroom interactions among students without reticence; preparation of students for clinical rotations; consideration of students’ psychological and social status; consideration of students’ economic status; greater educational justice; improvement of the ethical environment and increased student resilience; improving students’ academic performance and increasing their motivation; improved student’s patient care and clinical skills; and increased learner independence and self-efficacy. The most frequently cited advantages in the learner domain were Consideration of students’ psychological and social status (5 studies), consideration of students’ economic status (4 studies), and development of students’ technical and computer skills (4 studies).

Teaching-Learning Process

Challenges

The challenges of distance medical education in this domain were as follows: Suspension of clinical rotation/practical programs and the slowing down of the learning process; reduced interaction between professors and students; lack of a clear and unified classroom policy; reduced learning quality; poor quality of the virtual education system; limited international experience due to unpreparedness of universities for the pandemic; compulsory e-learning and hasty introduction of related technologies; reduced access to educational content; high cost of Internet access; and concerns over security of personal information across platforms. The most frequently cited challenges in this domain were the suspension of clinical rotation/practical programs, the slowing down of the learning process (6 studies), and reduced interaction between professors and students (3 studies).

Solutions

Several interventions have been used worldwide to address the challenges associated with the teaching-learning process domain. The main interventions were virtualizing classes and classroom activities for both students and interns (19 studies); sustainable financing of distance medical education (3 studies); redefining the educational landscape, strategic planning, mission, values, goals, and plans to turn challenges into opportunities (3 studies); sustainable financing of distance medical education (2 studies); and postponing internships until COVID-19 is contained (2 studies). The most frequently cited intervention is virtualizing classes and educational activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of e-learning platforms that existed before the pandemic, building on previous remote learning experiences, the use of “virtual patient” technologies, development of digital laboratories and medical libraries, production of online/offline electronic content, and the combination of distance and face-to-face education were examples of solutions that medical schools have used to keep education going during the pandemic.

Advantages

The process of distance education has significant advantages such as: Strengthening management, leadership, and planning for future crises; continuity of education, cost-effectiveness; flexible access to educational material; ability to watch videos and revisit educational material without limitation; continuity of administrative work, albeit at a slow pace; the opportunity for cooperation and establishment of new councils that encourage participation by universities, students, and other stakeholders in the development of educational/clinical policies; greater creativity in educational management and implementation; development of medical education activities in the cyberspace and social media; the appeal of online scientific discussion; and development of research networks. The most frequently cited advantages were cost-effectiveness (4 studies), the development of medical education activities in cyberspace and social media (4 studies), flexible access to educational material (3 studies), and greater creativity in educational management and implementation (3 studies).

Technical Infrastructure Domain

Challenges

The most frequent challenges related to technical infrastructure were Low bandwidth and lack of seamless Internet connectivity (3 studies); time, personal protection equipment, and physical space constraints (2 studies); financial constraints (2 studies); and shortage of human resources (2 studies).

Solutions

The main solutions for addressing technical infrastructure challenges in distance medical education were Using alternative technologies to improve remote learning of anatomy and laboratory work, such as remote robotic microscopy, artificial intelligence, digital libraries, clinical simulation laboratories, and virtual haptic laboratory; developing an online IT support system to answer questions and solve technical problems; integrating online education technologies; using Adobe Connect to create and manage virtual classes; using various software programs to hold synchronous virtual classes, including Big Blue Button, Skype, Skyroom, and Zoom; using social media, academic websites, and video sharing platforms such as YouTube; enhancing servers; improving the security of systems and platforms; using various technologies and social media to streamline and optimize virtual conferences; assessing the di-agnostic skills of dentistry students by performing clinical procedures during examination; and clinical reasoning and critical thinking in the absence of clinical procedures. The most frequently cited technical intervention is using alternative technologies to improve remote learning of anatomy and laboratory work (5 studies).

Advantages

The technical infrastructure of distance medical education has two major advantages: The development of distance learning software and technologies such as artificial intelligence, telemedicine, simulation, and AI-assisted platforms (7 studies) and the reliability of e-learning technologies (2 studies).

Instructor Domain

Challenges

There were many challenges in teaching medical sciences electronically. The most important challenges instructors faced were unfamiliarity with electronic systems before the pandemic; poor technological skills; lack of motivation; and pedagogic barriers. The most frequently cited challenges were poor technological skills (4 studies) and lack of motivation (3 studies). During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical school faculty face technical challenges due to the sudden shift to online platforms and their lack of experience with online teaching methods. In addition, school closures and reduced interaction with students, other professors, and the faculty environment can lead to a loss of motivation.

Solutions

Effective interventions for addressing the challenges of the instructor domain were granting scholarships to faculty members with increased workload (e.g., those producing video lessons); using mentorship in online education; giving faculty members and educational groups the authority to decide on the volume of synchronous/asynchronous face-to-face and online training according to the nature of the course and the conditions of students/faculty members; providing training (Online, offline, face-to-face) on how to work with software and electronic infrastructure to faculty members who were less familiar with virtual education; developing content creation software to help instructors in preparing multimedia educational material; creating a website for teaching faculty members about distance education infrastructure and software; encouraging participation by faculty members in preparing electronic content and educational packages; communicating with faculty members to solve their issues and exchange information; conducting a needs assessment to control the quality of e-content by contacting students/trainees and preparing them before starting online learning programs; conducting research on e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of students and professors; and removing pedagogic barriers and redefining how the content is created and presented to students. The most frequently cited solutions were Conducting research on e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of students and professors (4 studies), and training faculty members (Online, offline, face-to-face) on how to work with software and electronic infrastructure (2 studies).

Advantages

The advantages of distance medical education in the instructor domain were the development of instructors’ technical and computer skills (4 studies) and the development of mentoring and coaching skills (2 studies). The interventions that medical schools have used to address the challenges of faculty members during COVID-19 have ultimately resulted in the development of professors' technical and technological skills in working with computers and distance learning software. Moreover, mentoring and coaching skills were considered in education to help students manage small groups.

Evaluation

Challenges

In the evaluation domain, the most important challenges of distance medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic were the lack of a clear and unified policy for conducting and grading online exams, the lack of tools to evaluate the effectiveness of distance education interventions for nursing or medical interns; and concerns about the integrity of online exams. The sudden cancellation of exams, uncertainty about how to evaluate students, the unintegrated approach to evaluation, and the lack of specific tools for measuring the interventions that have replaced face-to-face education were the most important challenges of distance medical education during COVID-19. Furthermore, the sudden shift to online exams and electronic evaluations has not given instructors the necessary confidence in their student evaluations.

Solutions

The main solutions to evaluation challenges in distance medical education were Conducting online exams; replacing face-to-face final exams with assignments, projects, and classroom activities; diversifying and changing teaching/evaluation methods; and allocating 30-50% of course credits to assignments, projects, and exercises and 50-70% to the final exams. The most important solution cited in five studies is to evaluate the number of uploaded contents, assignments and exercises, formative tests, the number of activities provided by instructors, the number of activities performed by students, and the number of feedbacks and exchanges with professors.

Advantages

The most important advantages of evaluation during COVID-19 were Reduced interval between evaluations, repeated evaluation of the activities of instructors and students, and the ability to evaluate medical education methods better.

Discussion

The spread of COVID-19 worldwide has required governments to take rapid and efficient preventive measures [2]. One of the important areas in this field is the continuity of education, especially medical training. In the wake of the pandemic, countries shifted from face-to-face to distance learning [11, 20-22]. For example, preventive policies initiated by the Chinese government were not limited to social distancing and school closures. The Chinese government implemented an emergency plan called “Suspending Classes Without Stopping Learning, " which means switching from traditional to online education [22].

The purpose of the present scoping review was to investigate the virtual education policies of medical schools during COVID-19. Between 2020 and 2022, 38 articles were published on this topic, from which 34 challenges, 62 solutions, and 27 advantages were identified and categorized into the five key domains: Learner, teaching-learning process, technical infrastructure, instructor, and evaluation. These domains and elements were then presented as a matrix titled the “Fabric of Virtual Medical Education Policies during the COVID-19 Pandemic”.

Nine challenges, 13 solutions, and 11 advantages were identified in the learner domain. One of the most important challenges in this domain is the anxiety and social/psychological damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A study in Malaysia found that students experienced significant anxiety levels during the pandemic and subsequent lockdown. In this study, the main stressors included financial constraints, remote online teaching, and uncertainty about the future with regard to academics [18]. Harries et al. reported that the pandemic moderately affected college students’ stress and anxiety levels, with 84.1 percent of respondents feeling at least somewhat anxious. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the education of US medical students in their clinical training years. Most students wished to return to clinical rotations and were willing to accept the risk of infection. Students were mostly concerned about having adequate personal protective equipment if allowed to return to clinical activities [14].

The results of the present study showed that educational systems should adopt e-learning policies and use reliable technology and communication tools in efficient online platforms to shift from traditional to web-based education in emergencies and increase learners’ access. To balance student safety and well-being with the time-sensitive need to train future physicians and paramedics, students must be made aware of the pressures on the healthcare system so that they can be more patient with the educational impacts of the pandemic [14].

Ten challenges, 49 solutions, and 11 advantages were identified in the teaching-learning process domain. The most frequently cited challenges were the suspension of clinical rotations and practical programs, the slowing down of the learning process, and the reduction of teacher-student interaction. Studies have shown that early in the pandemic, only the teaching platform was changed [23, 24]. Instead of shifting to virtual education, virtual education replaced face-to-face education with its traditional features and methods. In contrast, transitioning to virtual education requires specific goals, content, teaching methods, educational design, and evaluation methods.

Several suggestions have been made for improving the e-learning process. Using hybrid learning strategies, including practical/in-person clinical training, effectively improves the e-learning process [25]. Providing technical training to staff and students, having an exam policy in place for times when internet connectivity is disrupted (e.g., offering more time for completing exams and allowing multiple attempts), making greater use of videos for educational material, having an effective system that detects and prevents cheating, encouraging active interaction between the instructor and the learner [26], providing opportunities for online access to educational resources and open-source materials [27], supporting the instructional design and delivery mechanisms using set learning objectives including teaching strategies, and embedding feedback and evaluation [28] were other solutions for facilitating the learning process.

The present study identified eight challenges, ten solutions, and two advantages in the technical infrastructure domain. Among the challenges discussed were problems with Internet access and poor technology skills. In a study on the e-learning experience of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia, Al Zahrani identified inadequate tools to facilitate online learning, poor internet connection, and lack of technological skills by educators and students as the main challenges of e-learning [11].

Similarly, Alhassan found that health trainees were constrained by low bandwidth and lack of seamless Internet connectivity within their learning environments to take full advantage of e-learning opportunities [25]. The transition to online platforms has led to disparities in access to learning. While students may use their mobile phones to access resources, the type and capacity of the device can be problematic as there is not enough memory space to download the platforms used for learning. The battery life of these devices is also a limitation [29].

It is agreed that the success of e-learning programs depends largely on the learning tools and technical support available to users [30]. Moreover, appropriate technical support and maintenance of existing hardware and software are crucial to professors' and students' optimal use of technology [31, 32]. Each e-learning system builds a core set of computers, networks, communications, technical facilities, and IT professionals to maintain and continuously upgrade the system, train users, and provide technical support [33]. A good example is e-learning standards for higher education in Sau-di Arabia, which were made in accordance with leading international standards and include technology, training and support, design, interaction, equity and access, and assessment and evaluation [11].

Four challenges, 11 solutions, and two advantages were identified in the teacher domain. Among the challenges in this domain were Instructors’ unfamiliarity with the electronic systems that existed before the pandemic, poor technological skills, and lack of motivation. It must be noted that the active role of instructors and their responsiveness and feedback are crucial to student satisfaction with online education because the professor is the key element of success in the e-learning environment [34]. Sun et al. examined the instructors’ role in the success of e-learning by focusing on two specific indicators: the instructor’s response timeliness and attitude toward e-learning. They found a positive and significant relationship between these aspects and student satisfaction [35]. Similar findings were reported by Sideral et al. They documented a positive relationship between instructor attitudes toward e-learning and user satisfaction [36]. In addition, Al-Fraihat et al. found a positive relationship between instructor quality and students’ perceived satisfaction with the e-learning system [37].

A survey of 178 special needs students from different Indonesian universities showed that teaching presence, cognitive and social presence, and content quality directly and indirectly affect satisfaction with e-learning [38]. Providing online training for instructors, livestreaming classes, pre-recording lectures, facilitating discussions on an electronic platform, and providing assessment and feedback [39] can improve instructors’ ability to conduct online classes. Farajollahi et al. stress that the success of online learning is contingent upon both professors’ and students’ readiness to shift from traditional face-to-face learning to online learning [40].

This study identified three challenges, nine solutions, and two advantages in the evaluation domain. One of the main challenges is the lack of a clear and unified policy and a suitable tool for conducting and grading online exams. Studies show that the evaluation method significantly affects students’ approach to learning [41]. Providing formative feedback to students is essential to their learning as it provides guidance on student performance [42]. However, feedback has often been limited due to faculty and students being too busy transitioning to remote education. Other methods of providing meaningful feedback should also be considered, including audio or video and peer feedback, which can help reduce the burden while maintaining educational quality [43].

Stress and concerns caused by the pandemic and changes in learning/evaluation affect student performance, and high-stakes exams increase students’ anxiety levels [43]. In his research on undergraduate students, Cann discusses that students favor audio feedback over written feedback [44]. He also emphasizes that the content of the feedback is as important as its timeliness [44]. Therefore, it is possible to improve student performance by teaching instructors how important it is to provide feedback in evaluations [45].

Conclusion

Education in COVID-19 time should be distinguished from the normal state of affairs. As such, embracing flexibility while ensuring accountability is a priority. In other words, we must ensure that learning outcomes are achieved without covering the entire content of the curriculum (e.g., providing some practical sessions that must be canceled due to lockdown). The identified challenges can be overcome through a comprehensive hybrid model that includes simulation-based online training, reducing face-to-face training in practical courses, training learners and instructors to take advantage of existing platforms, upgrading the technical infrastructure, and improving virtual education processes.

Acknowledgments: Not applicable.

Ethical Permission: This study was conducted with approval from the Research Ethics Committee (IR.SAVEHUMS.REC.1401.015).

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Saadati M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (25%); Kazemi F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%); Taheri S (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Isfahani P (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/ Assistant Researcher (15%); Afshari M (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: Saveh University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Technology of Health Education

Received: 2023/05/10 | Accepted: 2023/08/26 | Published: 2023/10/18

Received: 2023/05/10 | Accepted: 2023/08/26 | Published: 2023/10/18

References

1. Mofijur M, Fattah IMR, Alam MA, Islam A, Ong HC, Rahman SMA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustain Prod Consum. 2021;26:343-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.spc.2020.10.016]

2. Perlman S. Another decade, another coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):760-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMe2001126]

3. Guo Y, Huang Y, Huang J, Jin Y, Jiang W, Liu P, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: global epidemiological trends and China's subsequent preparedness and responses. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(5):642-7. [Link]

4. McIntosh K, Hirsch M, Bloom A. COVID-19: Epidemiology, virology, and prevention [Internet]. Alphen aan den Rijn: UpToDate 2021- [cited 2021 March 18]. Available from: https://www uptodate com/contents/covid-19-epidemiology-virology-and-prevention. [Link]

5. Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, Dulebohn S, Di Napoli R. Features, evaluation, and treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls. 2022. [Link]

6. Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.5227]

7. Doshmangir L, Ahari AM, Qolipour K, Azami S, Kalankesh L, Doshmangir P, et al. East Asia's strategies for effective response to COVID-19: Lessons learned for Iran. Qua J Manag Strategies Health Sys. 2020;4(4). [Link] [DOI:10.18502/mshsj.v4i4.2542]

8. Affouneh S, Salha S, Khlaif ZN. Designing quality e-learning environments for emergency remote teaching in coronavirus crisis. Interdisciplinary J Virtual Learn Med Sci. 2020;11(2):135-7. [Link]

9. Karimian Z, Farrokhi MR, Moghadami M, Zarifsanaiey N, Mehrabi M, Khojasteh L, et al. Medical education and COVID-19 pandemic: A crisis management model towards an evolutionary pathway. Educ Inf Technol. 2021;27(3):3299-320 [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10639-021-10697-8]

10. McKibbin W, Fernando R. The economic impact of COVID-19. London: CEPR Press; 2020. [Link]

11. Al Zahrani EM, Al Naam YA, AlRabeeah SM, Aldossary DN, Al-Jamea LH, Woodman A, et al. E-Learning experience of the medical profession's college students during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-021-02860-z]

12. Said JT, Schwartz AW. Remote medical education: Adapting Kern's Curriculum design to tele-teaching. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(2):805-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40670-020-01186-7]

13. Mansoury Khosraviyeh Z, Araghieh A, Barzegar N, Mehdizadeh AH, Jahed HA. Challenges and harms of e-learning at university during the Corona epidemic. Technol Educ J. 2022:16(4):805-18. [Persian] [Link]

14. Harries AJ, Lee C, Jones L, Rodriguez RM, Davis JA, Boysen-Osborn M, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: A multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02462-1]

15. Karimian Z, Kajouri J, Saqib MM. An analysis of evidence-based medical course teaching methods in domestic and foreign universities. Interdisciplinary J Virtual Learn Med Sci. 2015;6(1):64-75. [Persian] [Link]

16. Kalavani K, Dehnavieh R, Emadi S. Post-Covid-19 higher education scenarios and future strategic orientations of education. J Med Educ Dev. 2021;16(2):142-3. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/jmed.v16i2.7147]

17. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/1364557032000119616]

18. Sarkis-Onofre R, Catalá-López F, Aromataris E, Lockwood C. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):117. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z]

19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.n71]

20. Evans O. Socio-economic impacts of novel coronavirus: The policy solutions. BizEcons Qua. 2020;7:3-12. [Link]

21. Almaghaslah D, Ghazwani M, Alsayari A, Khaled A. Pharmacy students' perceptions towards online learning in a Saudi Pharmacy School. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26(5):617-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2018.03.001]

22. Zhang W, Wang Y, Yang L, Wang C. Suspending classes without stopping learning: China's education emergency management policy in the COVID-19 outbreak. J Risk Financial Manag. 2020;13(3):55. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jrfm13030055]

23. Karademir A, Yaman F, Saatçioglu Ö. Challenges of higher education institutions against COVID-19: The case of Turkey. J Pedagogical Res. 2020;4(4):453-74. [Link] [DOI:10.33902/JPR.2020063574]

24. Perrotta D. Universities and Covid-19 in Argentina: From community engagement to regulation. Stud Higher Educ. 2021;46(1):30-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03075079.2020.1859679]

25. Alhassan RK. Assessing the preparedness and feasibility of an e-learning pilot project for university level health trainees in Ghana: A cross-sectional descriptive survey. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):465. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02380-2]

26. Regmi K, Jones L. A systematic review of the factors-enablers and barriers-affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):96. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6]

27. Moule P, Ward R, Lockyer L. Nursing and healthcare students' experiences and use of e‐learning in higher education. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(12):2785-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05453.x]

28. Lewis KO, Cidon MJ, Seto TL, Chen H, Mahan JD. Leveraging e-learning in medical education. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44(6):150-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.01.004]

29. Honey M. Undergraduate student nurses' use of information and communication technology in their education. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;250:37-40. [Link]

30. Gray JA, DiLoreto M. The effects of student engagement, student satisfaction, and perceived learning in online learning environments. Int J Educ Leadersh Preparation. 2016;11(1). [Link]

31. Eimer C, Duschek M, Jung AE, Zick G, Caliebe A, Lindner M, et al. Video-based, student tutor-versus faculty staff-led ultrasound course for medical students-a prospective randomized study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):512. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02431-8]

32. Wentink MM, Siemonsma P, van Bodegom-Vos L, De Kloet A, Verhoef J, Vlieland T, et al. Teachers' and students' perceptions on barriers and facilitators for eHealth education in the curriculum of functional exercise and physical therapy: A focus groups study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):343. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-019-1778-5]

33. Ibrahim NK, Al Raddadi R, AlDarmasi M, Al Ghamdi A, Gaddoury M, AlBar HM, et al. Medical students' acceptance and perceptions of e-learning during the Covid-19 closure time in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. J Infection Public Health. 2021;14(1):17-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.11.007]

34. Cheng YM. Antecedents and consequences of e‐learning acceptance. Inf Sys J. 2011;21(3):269-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2010.00356.x]

35. Sun PC, Tsai RJ, Finger G, Chen YY, Yeh D. What drives a successful e-Learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction. Comput Educ. 2008;50(4):1183-202. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2006.11.007]

36. Cidral WA, Oliveira T, Di Felice M, Aparicio M. E-learning success determinants: Brazilian empirical study. Comput Educ. 2018;122:273-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2017.12.001]

37. Al-Fraihat D, Joy M, Sinclair J. Evaluating E-learning systems success: An empirical study. Comput Human Behav. 2020;102:67-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.004]

38. Amka A, Dalle J. The satisfaction of the special need'students with e-learning experience during COVID-19 pandemic: A case of educational institutions in indonesia. Contemporary Educ Technol. 2022;14(1):ep334. [Link] [DOI:10.30935/cedtech/11371]

39. Almaghaslah D, Alsayari A. The effects of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak on academic staff members: A case study of a pharmacy school in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:795. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/RMHP.S260918]

40. Farajollahi M, Zarifsanaee N. Distance teaching and learning in higher education: A conceptual model. Int Perspectives Distance Learn Higher Educ. 2012:13-32. [Link] [DOI:10.5772/35321]

41. Myyry L, Joutsenvirta T. Open-book, open-web online examinations: Developing examination practices to support university students' learning and self-efficacy. Active Learn Higher Educ. 2015;16(2):119-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1469787415574053]

42. Harlen W, Crick RD, Broadfoot P, Daugherty R, Gardner J, James M, et al. A systematic review of the impact of summative assessment and tests on students' motivation for learning. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, University of London Institute of Education; 2002. [Link]

43. Jaam M, Nazar Z, Rainkie DC, Hassan DA, Hussain FN, Kassab SE, et al. Using assessment design decision framework in understanding the impact of rapid transition to remote education on student assessment in health-related colleges: A qualitative study. PloS One. 2021;16(7):e0254444. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0254444]

44. Cann A. Engaging students with audio feedback. Bioscience Educ. 2014;22(1):31-41. [Link] [DOI:10.11120/beej.2014.00027]

45. Fraser BJ. Identifying the salient facets of a model of student learning: A synthesis of meta analyses. Int J Educ Res. 1987;11(2):187-212. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |