Volume 11, Issue 1 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(1): 159-165 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shirvani A, Sadooghiasl A, Kazemnejad A. Correlation between Professional Quality of Life and Caring Behaviors in Nurses Working During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (1) :159-165

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-67075-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-67075-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Compassion Fatigue [MeSH], Professional Burnout [MeSH], Empathy [MeSH], Nurses [MeSH], Covid-19 [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 2065 kb]

(943 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1538 Views)

Full-Text: (414 Views)

Introduction

Care is defined as an important service that nursing can provide to humanity [1]. Caring is an instrumental and expressive behavior [2]. Caring is a two-dimensional phenomenon including, emotional and physical. The emotional dimension of care includes providing emotional support to the patient through acceptance of feelings, empathy, trust, hope [3], appropriate therapeutic communication, listening to the patient and his feelings, and recognizing his wishes [4]. The physical dimension of care refers to activities such as healthcare, meeting needs, promoting physical comfort, diagnostic interventions [3] or specialized tests, giving medicine, and taking blood samples [4]. Because of the increase in complex care of patients and Lack of time, there is a risk that nursing practice will be pushed more to the technical aspect of care without emotional care. Care needs nurses who focus on connecting with people through seeing, understanding and accepting responsibility [5].

The outbreak of the Covid-19 crisis has faced problems in clinical work, especially in the nursing profession, because nurses are the front line of the healthcare system, who are directly exposed to Covid-19 and take care of patients [6]. Exposure to disease and increased risk of disease transmission among patients, families, and healthcare workers, lack of protective equipment and personal safety, lack of staff, high mortality rate, unfamiliar work environment, lack of experience in the care of infectious diseases, and prioritizing care behaviors have had a negative impact on nurses and has led to increased work stress and reduced patient safety. Therefore, caring for patients during the Covid-19 pandemic exposes nurses to both physical and emotional challenges [7].

Generally, healthcare professionals are at risk of professional stress and compassion fatigue due to their constant exposure to highly distressing situations, such as illness, suffering, and death [8]. Also, the existence of these pressures can reduce the quality of their professional life [9]. Considering that nurses are the largest group of healthcare professionals who provide direct and indirect care for all patients [10], it is important to pay attention to the quality of their professional life, and nurses should have a good professional quality of life so that they can take care of the patients in an optimal way [11]. In fact, Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) refers to a person's positive and negative feelings about his job [12], which includes two positive (compassion satisfaction) and negative (compassion fatigue) aspects [13]. Compassion fatigue includes the two main negative aspects of burnout and secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) [14] and refers to the “cost of care” incurred by health professionals while caring for those who are suffering [15]. Global estimates of the prevalence of compassion fatigue among nurses during the pre-pandemic period ranged from 22% to 60% and were found to be influenced by numerous factors, including personal, work-related, and psychosocial factors [16]. Satisfaction from compassion to emotional satisfaction, such as joy and pleasure from helping other people, is based on nursing professional knowledge. Compassionate satisfaction can be interpreted as an emotional state that reduces secondary traumatic stress [17].

A study by Mostafazadeh et al. [18] and a study by Buselli et al. [19] showed that 60-70% of nurses who care for patients with Covid-19 experience moderate to severe occupational stress, which has various consequences, including quality reduction.

The results of Orrù et al.'s study showed that during the Covid-19 pandemic, healthcare workers who are faced with physical pain, psychological suffering, and death of patients are more likely to suffer from STS [20].

According to Stamm [13], when compassion satisfaction is high, and burnout and compassion fatigue are low, professional quality of life improves. Professional quality of life is a balance between compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. When the quality of people's professional life is balanced, they will experience more flourishing in practice, as a result, nurses will have favorable caring behaviors. Nurses can communicate with patients and their families through the concept of empathy and compassion, which can prevent exhaustion and compassion fatigue and provide quality care to patients [21]. In addition, the satisfaction of compassion, as a source of strength, makes nurses continue to work despite dangerous working conditions and high levels of stress [17]. Job burnout and caring behaviors and the relationship between the two, since they are related to the professional quality of life of nurses, are of vital importance in the quality of care provided and the well-being of patients [22]. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the relationship between professional quality of life and caring behaviors of nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the correlation between professional quality of life and the caring behaviors of nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Instruments and Methods

This cross-sectional and correlational study was conducted in selected hospitals of Iran University of Medical Sciences in 2022. The selected hospitals were Imam Sajjad Hospital in Shahryar, Sardar Soleimani Hospital in Quds City, and Hazrat Fatimah Hospital in Rabat Karim. The study populawas were all nurses working in the study environment and having the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were working in the study environment as a nurse, having a bachelor's degree in nursing or higher, having work experience in the Covid-19 department, and willing to participate in the study. We excluded the questionnaires which were not completed. The samples were selected by convenience method.

To calculate the sample size, we used the findings of Inocian et al.'s study [23]. We considered a confidence interval of 95% and an accuracy of 1. The sample size was equal to 124 people, which was determined to be 150 people by taking into account the 20% attrition rate.

For gathering data, we used three self-report questionnaires, including a demographic and occupational information form, Stumm's professional quality of life questionnaire, and Wolf's caring behaviors of nurses’ questionnaire.

To comply with the health guidelines for the prevention of the spread of the Covid-19 disease, all questionnaires were prepared electronically using Google Forms. Full explanations related to the objectives of the study, obtaining informed consent, and how to complete the questions were included at the beginning of the questionnaire.

The link of the questionnaire was provided to the head nurse of each department to be sent to the WhatsApp group of each department, and thus it was provided to the nurses. Nurses opened the link using their smart phones and entered the questionnaire. With this method, the mobile number of the participant was not known to the researcher, and confidentiality was completely respected. All nurses were free to participate in the study or leave.

Research questionnaires

Demographic and occupational information forms included age, gender, marital status, nursing work experience, level of education, and work position in the department.

The Professional Quality of Life questionnaire (ProQOL) is a self-report questionnaire that was designed and developed by Stamm in 1990 [24]. In the present study, ProQOL version 5 (2010) was used to assess professional quality of life. Professional quality of life tool includes compassion satisfaction, with 10 questions and compassion fatigue (job burnout, with 10 questions and secondary traumatic stress, with 10 questions). A 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always) is used for scoring. The total score of each participant is calculated based on adding up his/her score in 30 options. The average score in each section is 50. A total score of 22 or less for each dimension indicates its low level. Score between 23 and 41 indicates an average level, and score of 42 or more indicates a high level of the same dimension. Persian version of professional quality of life questionnaire validated in Moradinejad's study. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by calculating Cronbach's alpha. Cronbach's alpha was 0.91 in the compassion satisfaction subscale, 0.86 in the burnout subscale, and 0.83 in the secondary trauma subscale [25]. In the current study, 10 nurses from the study population completed the questionnaire, and the internal consistency of the questionnaire was calculated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.75 that was acceptable.

The Caring Behaviors Inventory (CBI) was designed by Wolf in 1981. CBI was the first tool to measure nurses' caring behaviors. The first version of this questionnaire contained 75 items, which was revised and revised by Larrabee and Putnam in 2006 and reduced to 24 items and validated (Cronbach's alpha = 0.96). This 24-item questionnaire is graded on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The range of scores is 24-96, and a higher score indicates a higher caring behavior [26]. This scale has four subgroups, including assurance of human presence (8 items), knowledge and skills (5 items), respect for the patient (6 items), and communication and positive attitude (5 items) [27]. This tool was translated and validated in the Persian language in Kamali's study, and its Cronbach's alpha was reported as 0.976 [26]. In the current study, 10 nurses from the study population completed the questionnaire, and the internal consistency of the questionnaire was calculated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.91.

We used SPSS 22 software to analyze data. Mean and Standard Deviation (SD) were used to describe quantitative variables, and frequency and percentage were used to describe qualitative variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of data distribution. Spearman's correlation test, Mann-Whitney test, and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to check the correlation between variables. Linear regression methods were used to determine the relationship between the main variables of the study.

Findings

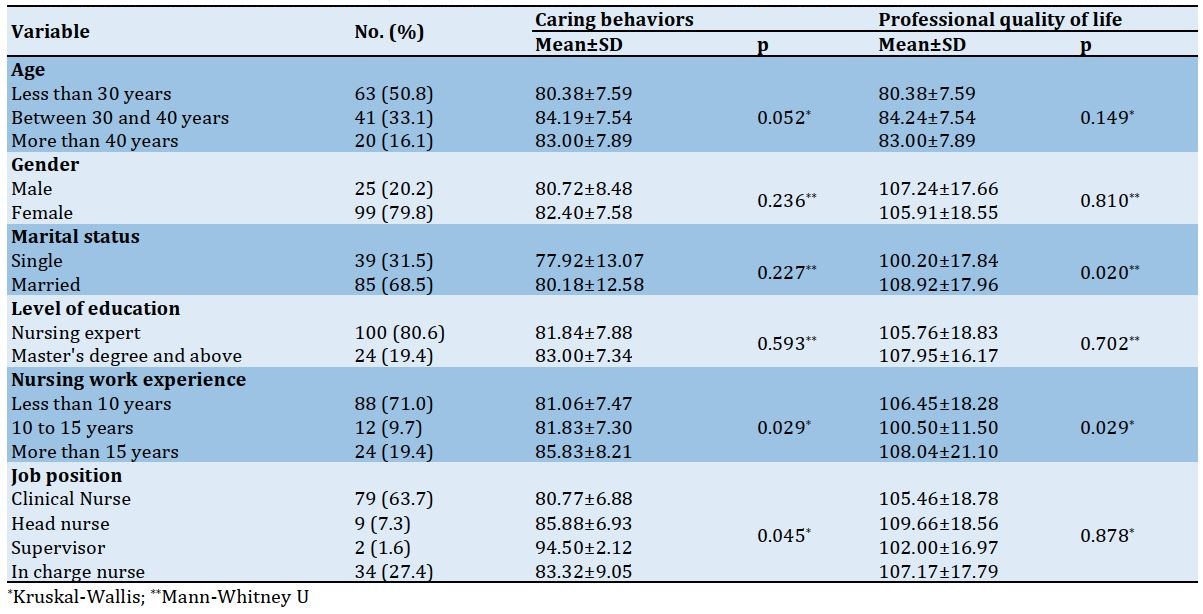

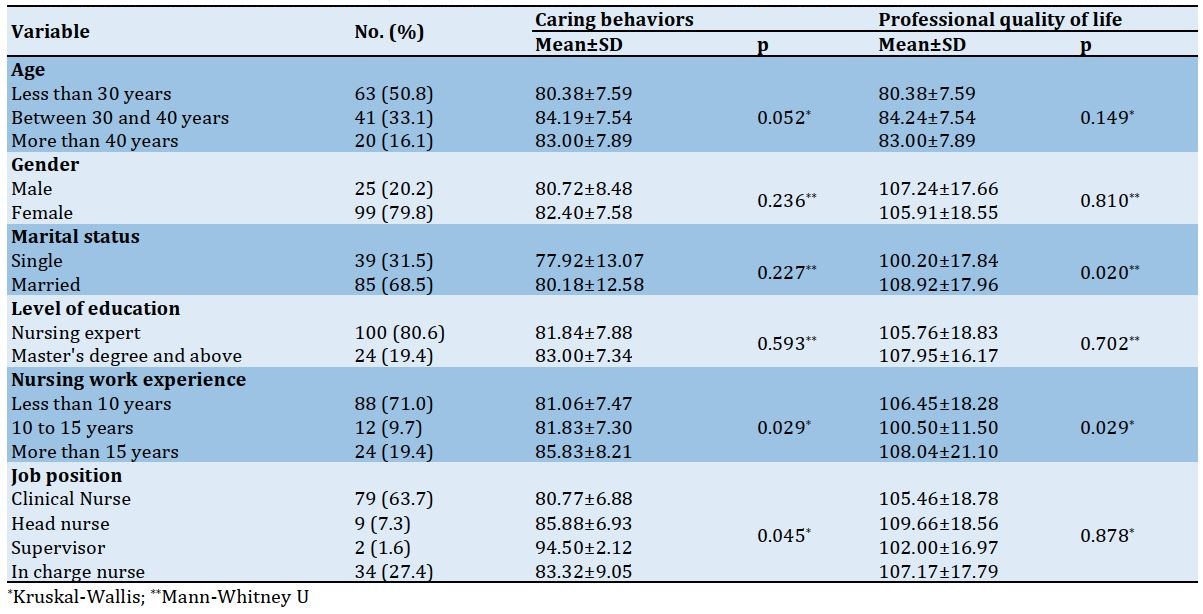

Most of the participants were female (79.8%), married (68.5%), had a bachelor's degree in nursing (80.6%), worked as a clinical nurse (63.7%), were under 30 years old (50.8%) and had less than 10 years of work experience (70%). A statistically significant correlation was found between professional quality of life with marital status (p=0.020) and nursing experience (p=0.029). The mean score was higher among nurses with more than 15 years of experience and who are married. There was no statistically significant correlation between the level of education with two main variables of the study (p>0.05; Table 1).

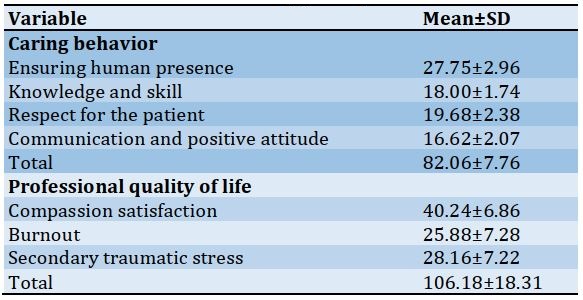

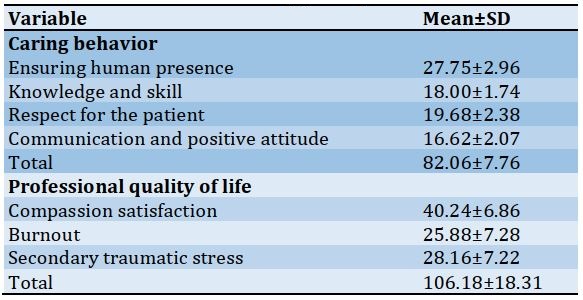

The overall mean score of caring behaviors was 82.06±7.76, and the overall mean score of professional quality of life was 106.18±18.31. The highest score was assigned to satisfaction after compassion (Table 2).

There was a significant and direct correlation between the professional quality of life and caring behaviors of nurses working in the Covid-19 epidemic (r=0.435; p<0.001), which means that the higher the professional quality of life of nurses, the better the behavior, and their care is also higher.

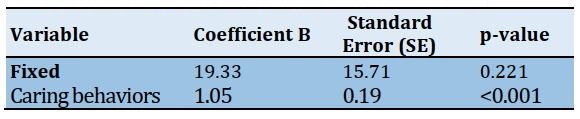

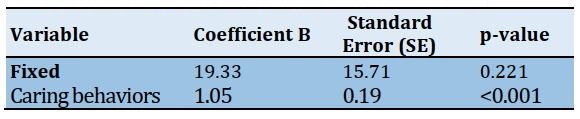

Also, the linear relationship between the care behavior variable and the professional life quality variable was significant, with a coefficient of 1.05 (Table 3).

The regression equation of this relationship will be as follows:

E (Professional quality of life score) = 1.05 (Caring behavior score) + 19.33

Table 1) Numerical indicators of caring behavior and professional quality of life of the studied nurses according to demographic changes

Table 2) Mean scores of caring behavior and professional quality of life and their subscales in study participants

Table 3) Linear regression model of correlation between nurses' caring behaviors and nurses' professional quality of life

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the relationship between professional quality of life and caring behaviors of nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to the results, there was a significant and direct linear relationship between professional quality of life and care behaviors, which means that the higher the quality of nurses' professional life, the higher their care behavior. The results of this study were in line with the results of Inocian et al. in Saudi Arabia during the epidemic of Covid-19 [23], Burtson and Stichler in the southwestern region of the United States [28], and Mohammadi [29].

The results of Burtson and Stichler showed that there was a statistically significant and positive correlation between compassion satisfaction and nurses' caring behaviors, and there was a statistically significant and negative correlation between compassion fatigue and nurses' caring behaviors. There was a relationship between stress and the caring behaviors of nurses. The author suggested that fostering compassion satisfaction and opportunities for social interaction among nurses may improve nurses' caring behaviors and potentially create long-term recovery in the patient [28].

In their study, Trumello et al. stated that healthcare workers who were directly in contact with patients with Covid-19 had higher levels of anxiety, stress, and depression than their colleagues. These results showed the need for early and effective identification of healthcare workers with mild symptoms of stress and anxiety to prevent more complex problems in this field [30].

Inocian et al.'s study in 2021 showed that the majority of respondents reported an average level of satisfaction with compassion (57.9%), burnout (54.4%), and secondary traumatic stress (66.9%) in the field of professional quality of life. Also, the results showed the positive and negative aspects of professional quality of life had an impact on nurses' caring behaviors. Therefore, nursing leaders can use this evidence base and implement programs for clinical nurses to deal with the professional quality of life issues and increase caring behaviors [23].

Mohammadi et al. stated that improving the professional quality of life in critical care nurses may increase their ability to care and thus lead to better and more effective nursing care. Increasing the awareness of critical care nursing managers about the phenomenon of compassion fatigue (secondary traumatic stress and job burnout) and its effect on the quality of critical care can be useful in planning more specific strategies and preventing the onset and progression of these symptoms [31].

Al Ma'mari et al. stated that the job burnout in nurses can reduce the quality of nurses' care behaviors and patient safety [32]. Also, the findings of Kim and Lee showed that nurses who were able to provide compassionate care to patients had a lower level of burnout [33].

Durkin et al. stated in their study that satisfaction with greater compassion was also positively related to compassion for others. In fact, higher professional quality of life is associated with more compassion for patients [21], which can improve the caring behavior of personnel.

Labrague and de Los Santos argued that frontline nurses were at risk of compassion fatigue during a pandemic. Compassion fatigue has a negative effect on the job satisfaction of nurses on the frontline of the fight against Covid-19, increasing the intention to leave the service and reducing the quality of nurses' caring behaviors [16].

During the epidemic of Covid-19, it is necessary for everyone to pay attention to their physical health and mental health. In this situation, due to the change in lifestyle and the presence of disease pressure, mental disorders and pressures have become very significant. Based on the results obtained from previous studies that were obtained during the outbreak of SARS and Ebola, health care workers suffer from some psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression and stress, which can severely affect the quality of their activity and service delivery [34].

Our findings showed that the studied nurses had an average level of professional quality of life. The existence of compassion fatigue in nurses was consistent with the data obtained in other countries involved in the serious crisis of Covid-19, such as Spain [35] and also with studies conducted before the pandemic, such as Jahangiri's study [11], which showed that contact continuity with suffering patients can increase compassion fatigue among health care professionals. Also, the results of this study are in line with the results of Pashib et al.'s study (the average level of professional quality of life), with the difference that in the present study, satisfaction with compassion was the highest score, but in Pashib's study, burnout was assigned to it [36]. Compassion satisfaction and job burnout scores of this study were in line with Ruiz-Fernández et al.'s study in Spain during the Covid-19 crisis and were at an average level, but the secondary trauma stress level in Ruiz Fernandez's study was low [37]. The moderate level of compassion fatigue for nurses is not surprising, as the Covid-19 pandemic has seriously affected the working conditions of healthcare professionals [38].

Compassion satisfaction levels obtained among nurses in the current study were also higher than the levels reported among Iranian nurses in recent studies conducted before the pandemic [39]. We believe that the special conditions created by this pandemic give nurses this opportunity. It has given them to rediscover their inner drive to provide care, which inspired them to choose the nursing profession through their unconditional effort and commitment to alleviate the pain and suffering of patients in a situation. The extreme difficulty and uncertainty of this pandemic have increased the visibility of the nursing profession and show society's need for highly skilled and specialized professionals, elements considered necessary to improve the social image of the nursing profession [35].

This study showed that there was a statistically significant relationship between the score of professional quality of life and marital status, and the score was higher in married people and nurses with more than 15 years of experience. The results of the present study about marital status are in line with the results of Mohammadi's study [29]. Given that married people have the opportunity to talk about workplace problems with their spouses, marital status seems to act more as a support. Concerning work experience, the results of the study were also consistent with the results of Roney's study [40], so it can be said that with high work experience, nurses can adapt to manage stress and tension.

The limitation of this study was the self-reported data collection, so it is possible that the findings do not reflect the actual caring behaviors and self-compassion of nurses. The research environment in this study was three hospitals located in the western cities of Tehran province. The specific characteristics of the participants can affect the generalizability of the data.

According to the findings of this study, suggestions are given for future studies:

- Conducting a similar study with larger sample size and in different environments

- Examining the relationship between care behavior and nurses' productivity and nurses' job satisfaction

- Investigating the factors affecting nurses' care behavior and the quality of nurses' professional life and strategies to improve it

Based on the results of the study, clinical and nursing managers should implement practical and comprehensive programs to increase compassion satisfaction and reduce compassion fatigue in nurses. Improving the working conditions of nurses may improve the satisfaction of nurses and patients as well as the quality of care. Considering that in this study, a significant relationship was found between professional quality of life and caring behaviors, improving the professional quality of life of employees can be effective in providing better and more quality care.

Conclusion

The professional quality of life is significantly and directly correlated with caring behaviors in nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, improving the professional quality of life of employees can be effective in providing better and more quality care.

Acknowledgements: We hereby express our gratitude to the research assistant of Tarbiat Modares University for supporting this research. Also, the dear nurses who cooperated in this research are sincerely thanked and appreciated.

Ethical Permissions: This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of research and regulations in terms of confidentiality of data, anonymity, and provision of informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Tarbiat Modares University (Ethical code: IR.MODARES.REC.1400.346). We obtained written and oral informed consent after providing a full explanation of the study objectives and participating method to participants. Participants were free to participate in the study or leave the study. Confidentiality and anonymity of all participants were considered.

Conflict of Interests: There was no conflict of interest.

Authors Contribution: Shirvani A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Sadooghiasl A (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (40%); Kazemnejad A (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding: This article is based on the first author's master's thesis in community health nursing at Tarbiat Modares University and has been supported by that university.

Care is defined as an important service that nursing can provide to humanity [1]. Caring is an instrumental and expressive behavior [2]. Caring is a two-dimensional phenomenon including, emotional and physical. The emotional dimension of care includes providing emotional support to the patient through acceptance of feelings, empathy, trust, hope [3], appropriate therapeutic communication, listening to the patient and his feelings, and recognizing his wishes [4]. The physical dimension of care refers to activities such as healthcare, meeting needs, promoting physical comfort, diagnostic interventions [3] or specialized tests, giving medicine, and taking blood samples [4]. Because of the increase in complex care of patients and Lack of time, there is a risk that nursing practice will be pushed more to the technical aspect of care without emotional care. Care needs nurses who focus on connecting with people through seeing, understanding and accepting responsibility [5].

The outbreak of the Covid-19 crisis has faced problems in clinical work, especially in the nursing profession, because nurses are the front line of the healthcare system, who are directly exposed to Covid-19 and take care of patients [6]. Exposure to disease and increased risk of disease transmission among patients, families, and healthcare workers, lack of protective equipment and personal safety, lack of staff, high mortality rate, unfamiliar work environment, lack of experience in the care of infectious diseases, and prioritizing care behaviors have had a negative impact on nurses and has led to increased work stress and reduced patient safety. Therefore, caring for patients during the Covid-19 pandemic exposes nurses to both physical and emotional challenges [7].

Generally, healthcare professionals are at risk of professional stress and compassion fatigue due to their constant exposure to highly distressing situations, such as illness, suffering, and death [8]. Also, the existence of these pressures can reduce the quality of their professional life [9]. Considering that nurses are the largest group of healthcare professionals who provide direct and indirect care for all patients [10], it is important to pay attention to the quality of their professional life, and nurses should have a good professional quality of life so that they can take care of the patients in an optimal way [11]. In fact, Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) refers to a person's positive and negative feelings about his job [12], which includes two positive (compassion satisfaction) and negative (compassion fatigue) aspects [13]. Compassion fatigue includes the two main negative aspects of burnout and secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) [14] and refers to the “cost of care” incurred by health professionals while caring for those who are suffering [15]. Global estimates of the prevalence of compassion fatigue among nurses during the pre-pandemic period ranged from 22% to 60% and were found to be influenced by numerous factors, including personal, work-related, and psychosocial factors [16]. Satisfaction from compassion to emotional satisfaction, such as joy and pleasure from helping other people, is based on nursing professional knowledge. Compassionate satisfaction can be interpreted as an emotional state that reduces secondary traumatic stress [17].

A study by Mostafazadeh et al. [18] and a study by Buselli et al. [19] showed that 60-70% of nurses who care for patients with Covid-19 experience moderate to severe occupational stress, which has various consequences, including quality reduction.

The results of Orrù et al.'s study showed that during the Covid-19 pandemic, healthcare workers who are faced with physical pain, psychological suffering, and death of patients are more likely to suffer from STS [20].

According to Stamm [13], when compassion satisfaction is high, and burnout and compassion fatigue are low, professional quality of life improves. Professional quality of life is a balance between compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. When the quality of people's professional life is balanced, they will experience more flourishing in practice, as a result, nurses will have favorable caring behaviors. Nurses can communicate with patients and their families through the concept of empathy and compassion, which can prevent exhaustion and compassion fatigue and provide quality care to patients [21]. In addition, the satisfaction of compassion, as a source of strength, makes nurses continue to work despite dangerous working conditions and high levels of stress [17]. Job burnout and caring behaviors and the relationship between the two, since they are related to the professional quality of life of nurses, are of vital importance in the quality of care provided and the well-being of patients [22]. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the relationship between professional quality of life and caring behaviors of nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the correlation between professional quality of life and the caring behaviors of nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Instruments and Methods

This cross-sectional and correlational study was conducted in selected hospitals of Iran University of Medical Sciences in 2022. The selected hospitals were Imam Sajjad Hospital in Shahryar, Sardar Soleimani Hospital in Quds City, and Hazrat Fatimah Hospital in Rabat Karim. The study populawas were all nurses working in the study environment and having the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were working in the study environment as a nurse, having a bachelor's degree in nursing or higher, having work experience in the Covid-19 department, and willing to participate in the study. We excluded the questionnaires which were not completed. The samples were selected by convenience method.

To calculate the sample size, we used the findings of Inocian et al.'s study [23]. We considered a confidence interval of 95% and an accuracy of 1. The sample size was equal to 124 people, which was determined to be 150 people by taking into account the 20% attrition rate.

For gathering data, we used three self-report questionnaires, including a demographic and occupational information form, Stumm's professional quality of life questionnaire, and Wolf's caring behaviors of nurses’ questionnaire.

To comply with the health guidelines for the prevention of the spread of the Covid-19 disease, all questionnaires were prepared electronically using Google Forms. Full explanations related to the objectives of the study, obtaining informed consent, and how to complete the questions were included at the beginning of the questionnaire.

The link of the questionnaire was provided to the head nurse of each department to be sent to the WhatsApp group of each department, and thus it was provided to the nurses. Nurses opened the link using their smart phones and entered the questionnaire. With this method, the mobile number of the participant was not known to the researcher, and confidentiality was completely respected. All nurses were free to participate in the study or leave.

Research questionnaires

Demographic and occupational information forms included age, gender, marital status, nursing work experience, level of education, and work position in the department.

The Professional Quality of Life questionnaire (ProQOL) is a self-report questionnaire that was designed and developed by Stamm in 1990 [24]. In the present study, ProQOL version 5 (2010) was used to assess professional quality of life. Professional quality of life tool includes compassion satisfaction, with 10 questions and compassion fatigue (job burnout, with 10 questions and secondary traumatic stress, with 10 questions). A 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always) is used for scoring. The total score of each participant is calculated based on adding up his/her score in 30 options. The average score in each section is 50. A total score of 22 or less for each dimension indicates its low level. Score between 23 and 41 indicates an average level, and score of 42 or more indicates a high level of the same dimension. Persian version of professional quality of life questionnaire validated in Moradinejad's study. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by calculating Cronbach's alpha. Cronbach's alpha was 0.91 in the compassion satisfaction subscale, 0.86 in the burnout subscale, and 0.83 in the secondary trauma subscale [25]. In the current study, 10 nurses from the study population completed the questionnaire, and the internal consistency of the questionnaire was calculated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.75 that was acceptable.

The Caring Behaviors Inventory (CBI) was designed by Wolf in 1981. CBI was the first tool to measure nurses' caring behaviors. The first version of this questionnaire contained 75 items, which was revised and revised by Larrabee and Putnam in 2006 and reduced to 24 items and validated (Cronbach's alpha = 0.96). This 24-item questionnaire is graded on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The range of scores is 24-96, and a higher score indicates a higher caring behavior [26]. This scale has four subgroups, including assurance of human presence (8 items), knowledge and skills (5 items), respect for the patient (6 items), and communication and positive attitude (5 items) [27]. This tool was translated and validated in the Persian language in Kamali's study, and its Cronbach's alpha was reported as 0.976 [26]. In the current study, 10 nurses from the study population completed the questionnaire, and the internal consistency of the questionnaire was calculated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.91.

We used SPSS 22 software to analyze data. Mean and Standard Deviation (SD) were used to describe quantitative variables, and frequency and percentage were used to describe qualitative variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of data distribution. Spearman's correlation test, Mann-Whitney test, and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to check the correlation between variables. Linear regression methods were used to determine the relationship between the main variables of the study.

Findings

Most of the participants were female (79.8%), married (68.5%), had a bachelor's degree in nursing (80.6%), worked as a clinical nurse (63.7%), were under 30 years old (50.8%) and had less than 10 years of work experience (70%). A statistically significant correlation was found between professional quality of life with marital status (p=0.020) and nursing experience (p=0.029). The mean score was higher among nurses with more than 15 years of experience and who are married. There was no statistically significant correlation between the level of education with two main variables of the study (p>0.05; Table 1).

The overall mean score of caring behaviors was 82.06±7.76, and the overall mean score of professional quality of life was 106.18±18.31. The highest score was assigned to satisfaction after compassion (Table 2).

There was a significant and direct correlation between the professional quality of life and caring behaviors of nurses working in the Covid-19 epidemic (r=0.435; p<0.001), which means that the higher the professional quality of life of nurses, the better the behavior, and their care is also higher.

Also, the linear relationship between the care behavior variable and the professional life quality variable was significant, with a coefficient of 1.05 (Table 3).

The regression equation of this relationship will be as follows:

E (Professional quality of life score) = 1.05 (Caring behavior score) + 19.33

Table 1) Numerical indicators of caring behavior and professional quality of life of the studied nurses according to demographic changes

Table 2) Mean scores of caring behavior and professional quality of life and their subscales in study participants

Table 3) Linear regression model of correlation between nurses' caring behaviors and nurses' professional quality of life

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the relationship between professional quality of life and caring behaviors of nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to the results, there was a significant and direct linear relationship between professional quality of life and care behaviors, which means that the higher the quality of nurses' professional life, the higher their care behavior. The results of this study were in line with the results of Inocian et al. in Saudi Arabia during the epidemic of Covid-19 [23], Burtson and Stichler in the southwestern region of the United States [28], and Mohammadi [29].

The results of Burtson and Stichler showed that there was a statistically significant and positive correlation between compassion satisfaction and nurses' caring behaviors, and there was a statistically significant and negative correlation between compassion fatigue and nurses' caring behaviors. There was a relationship between stress and the caring behaviors of nurses. The author suggested that fostering compassion satisfaction and opportunities for social interaction among nurses may improve nurses' caring behaviors and potentially create long-term recovery in the patient [28].

In their study, Trumello et al. stated that healthcare workers who were directly in contact with patients with Covid-19 had higher levels of anxiety, stress, and depression than their colleagues. These results showed the need for early and effective identification of healthcare workers with mild symptoms of stress and anxiety to prevent more complex problems in this field [30].

Inocian et al.'s study in 2021 showed that the majority of respondents reported an average level of satisfaction with compassion (57.9%), burnout (54.4%), and secondary traumatic stress (66.9%) in the field of professional quality of life. Also, the results showed the positive and negative aspects of professional quality of life had an impact on nurses' caring behaviors. Therefore, nursing leaders can use this evidence base and implement programs for clinical nurses to deal with the professional quality of life issues and increase caring behaviors [23].

Mohammadi et al. stated that improving the professional quality of life in critical care nurses may increase their ability to care and thus lead to better and more effective nursing care. Increasing the awareness of critical care nursing managers about the phenomenon of compassion fatigue (secondary traumatic stress and job burnout) and its effect on the quality of critical care can be useful in planning more specific strategies and preventing the onset and progression of these symptoms [31].

Al Ma'mari et al. stated that the job burnout in nurses can reduce the quality of nurses' care behaviors and patient safety [32]. Also, the findings of Kim and Lee showed that nurses who were able to provide compassionate care to patients had a lower level of burnout [33].

Durkin et al. stated in their study that satisfaction with greater compassion was also positively related to compassion for others. In fact, higher professional quality of life is associated with more compassion for patients [21], which can improve the caring behavior of personnel.

Labrague and de Los Santos argued that frontline nurses were at risk of compassion fatigue during a pandemic. Compassion fatigue has a negative effect on the job satisfaction of nurses on the frontline of the fight against Covid-19, increasing the intention to leave the service and reducing the quality of nurses' caring behaviors [16].

During the epidemic of Covid-19, it is necessary for everyone to pay attention to their physical health and mental health. In this situation, due to the change in lifestyle and the presence of disease pressure, mental disorders and pressures have become very significant. Based on the results obtained from previous studies that were obtained during the outbreak of SARS and Ebola, health care workers suffer from some psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression and stress, which can severely affect the quality of their activity and service delivery [34].

Our findings showed that the studied nurses had an average level of professional quality of life. The existence of compassion fatigue in nurses was consistent with the data obtained in other countries involved in the serious crisis of Covid-19, such as Spain [35] and also with studies conducted before the pandemic, such as Jahangiri's study [11], which showed that contact continuity with suffering patients can increase compassion fatigue among health care professionals. Also, the results of this study are in line with the results of Pashib et al.'s study (the average level of professional quality of life), with the difference that in the present study, satisfaction with compassion was the highest score, but in Pashib's study, burnout was assigned to it [36]. Compassion satisfaction and job burnout scores of this study were in line with Ruiz-Fernández et al.'s study in Spain during the Covid-19 crisis and were at an average level, but the secondary trauma stress level in Ruiz Fernandez's study was low [37]. The moderate level of compassion fatigue for nurses is not surprising, as the Covid-19 pandemic has seriously affected the working conditions of healthcare professionals [38].

Compassion satisfaction levels obtained among nurses in the current study were also higher than the levels reported among Iranian nurses in recent studies conducted before the pandemic [39]. We believe that the special conditions created by this pandemic give nurses this opportunity. It has given them to rediscover their inner drive to provide care, which inspired them to choose the nursing profession through their unconditional effort and commitment to alleviate the pain and suffering of patients in a situation. The extreme difficulty and uncertainty of this pandemic have increased the visibility of the nursing profession and show society's need for highly skilled and specialized professionals, elements considered necessary to improve the social image of the nursing profession [35].

This study showed that there was a statistically significant relationship between the score of professional quality of life and marital status, and the score was higher in married people and nurses with more than 15 years of experience. The results of the present study about marital status are in line with the results of Mohammadi's study [29]. Given that married people have the opportunity to talk about workplace problems with their spouses, marital status seems to act more as a support. Concerning work experience, the results of the study were also consistent with the results of Roney's study [40], so it can be said that with high work experience, nurses can adapt to manage stress and tension.

The limitation of this study was the self-reported data collection, so it is possible that the findings do not reflect the actual caring behaviors and self-compassion of nurses. The research environment in this study was three hospitals located in the western cities of Tehran province. The specific characteristics of the participants can affect the generalizability of the data.

According to the findings of this study, suggestions are given for future studies:

- Conducting a similar study with larger sample size and in different environments

- Examining the relationship between care behavior and nurses' productivity and nurses' job satisfaction

- Investigating the factors affecting nurses' care behavior and the quality of nurses' professional life and strategies to improve it

Based on the results of the study, clinical and nursing managers should implement practical and comprehensive programs to increase compassion satisfaction and reduce compassion fatigue in nurses. Improving the working conditions of nurses may improve the satisfaction of nurses and patients as well as the quality of care. Considering that in this study, a significant relationship was found between professional quality of life and caring behaviors, improving the professional quality of life of employees can be effective in providing better and more quality care.

Conclusion

The professional quality of life is significantly and directly correlated with caring behaviors in nurses working during the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, improving the professional quality of life of employees can be effective in providing better and more quality care.

Acknowledgements: We hereby express our gratitude to the research assistant of Tarbiat Modares University for supporting this research. Also, the dear nurses who cooperated in this research are sincerely thanked and appreciated.

Ethical Permissions: This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of research and regulations in terms of confidentiality of data, anonymity, and provision of informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Tarbiat Modares University (Ethical code: IR.MODARES.REC.1400.346). We obtained written and oral informed consent after providing a full explanation of the study objectives and participating method to participants. Participants were free to participate in the study or leave the study. Confidentiality and anonymity of all participants were considered.

Conflict of Interests: There was no conflict of interest.

Authors Contribution: Shirvani A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (40%); Sadooghiasl A (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (40%); Kazemnejad A (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding: This article is based on the first author's master's thesis in community health nursing at Tarbiat Modares University and has been supported by that university.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Healthy Life Style

Received: 2022/12/27 | Accepted: 2023/03/8 | Published: 2023/04/4

Received: 2022/12/27 | Accepted: 2023/03/8 | Published: 2023/04/4

References

1. Devi B, Pradhan MS, Giri MD, Lepcha MN. Watson's theory of caring in nursing education: challenges to integrate into nursing practice. J Posit Sch Psychol. 2022;6(4):1464-71. [Link]

2. Pajnkihar M, Kocbek P, Musović K, Tao Y, Kasimovskaya N, Štiglic G, et al. An international cross-cultural study of nursing students' perceptions of caring. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;84:104214. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104214]

3. Alikari V, Fradelos EC, Papastavrou E, Alikakou S, Zyga S. Psychometric properties of the Greek version of the caring behaviors inventory-16. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15186. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.15186]

4. Safa A, Rayat F, Arbabi Z, Abedzadeh M. The relationship between nurses' care behaviors and patients' satisfaction in public hospitals of Kashan. Q J Nurs Manag. 2021;10(3):1-10. [Persian] [Link]

5. Karlsson M, Pennbrant S. Ideas of caring in nursing practice. Nurs Philos. 2020;21(4):e12325. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/nup.12325]

6. Ibrahim MH, Allawy MEA. Relation between nurses' caring behaviors and satisfaction of patients with COVID-19. Egyp J Health Care. 2021;12(4):373-80. [Link] [DOI:10.21608/ejhc.2021.199768]

7. Hajibabaee F, Salisu WJ, Akhlaghi E, Farahani MA, Dehi MMN, Haghani S. The relationship between moral sensitivity and caring behavior among nurses in iran during COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):58. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12912-022-00834-0]

8. Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses' empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:1-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015]

9. Razaghpour H, Rejeh N, Heravi Karimooi M, Tadrisi SD. The study of relationship between self-compassion and job stress of nurses in intensive care units. Med Ethics J. 2021;15(46):e4. [Persian] [Link]

10. Khodayarimotlagh Z, Ahmadi F, Sadooghiasl A, Vaismoradi M. Professional protection as the strategy of nurse managers to deal with nursing negligence. Int Nurs Rev. 2022;69(4):442-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/inr.12744]

11. Azizkhani R, Heydari F, Sadeghi A, Ahmadi O, Meibody AA. Professional quality of life and emotional well-being among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Frontiers in Emergency Medicine. 2022;6(1):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/fem.v6i1.7674]

12. Tirgari B, Azizzadeh Forouzi M, Ebrahimpour M. Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout in Iranian psychiatric nurses. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2019;57(3):39-47. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/02793695-20181023-02]

13. Stamm BH. The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale. 2nd Edition. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org. [Link]

14. Delaney MC. Caring for the caregivers: Evaluation of the effect of an eight-week pilot mindful self-compassion (MSC) training program on nurses' compassion fatigue and resilience. PloS One. 2018;13(11):e0207261. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0207261]

15. Andersen JP, Papazoglou K, Collins P. Association of authoritarianism, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction among police officers in North America: An exploration. Int J Crimin Justice Sci. 2018;13(2):405-19. [Link]

16. Labrague LJ, de Los Santos JAA. Resilience as a mediator between compassion fatigue, nurses' work outcomes, and quality of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;61:151476. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151476]

17. Lee HJ, Lee M, Jang SJ. Compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout among nurses working in trauma centers: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7228. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18147228]

18. Mostafazadeh A, Ghorbani-Sani S, Seyed-Mohammadi N, Ghader-jola K, Habibpour Z. Resilience and its relationship with occupational stress and professional quality of life among nurses in COVID-19 isolation wards. Res Square. 2021:1-11 [Link] [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-240339/v1]

19. Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Chiumiento M, Del Lupo E, Dell'Oste V, et al. Professional quality of life and mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6180. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17176180]

20. Orrù G, Marzetti F, Conversano C, Vagheggini G, Miccoli M, Ciacchini R, et al. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1):337. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18010337]

21. Durkin M, Beaumont E, Martin CJH, Carson J. A pilot study exploring the relationship between self-compassion, self-judgement, self-kindness, compassion, professional quality of life and wellbeing among UK community nurses. Nurse Educa Today. 2016;46:109-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.030]

22. Shen A, Wang Y, Qiang W. A multicenter investigation of caring behaviors and burnout among oncology nurses in China. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(5):E246-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000680]

23. Inocian EP, Cruz JP, Saeed Alshehry A, Alshamlani Y, Ignacio EH, Tumala RB. Professional quality of life and caring behaviours among clinical nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Clin Nurs. 2021;10.1111/jocn.15937. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jocn.15937]

24. Gerami Nejad N, Hosseini M, Mousavi Mirzaei S, Ghorbani Moghaddam Z. Association between resilience and professional quality of life among nurses working in intensive care units. Iran J Nurs. 2019;31(116):49-60. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijn.31.116.49]

25. Moradnezhad M, Seylani K, Navab E, Esmaeilie M. Spiritual intelligence of nurses working at the intensive care units of hospitals affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Nurs Pract Today. 2017;4(4):170-9. [Link]

26. Kamali SH, Imanipour M, Emamzadeh Ghasemi HS, Zahra Razaghi Z. Effect of programmed family presence in coronary care units on patients' and families' anxiety. J Caring Sci. 2020;9(2):104-12. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/JCS.2020.016]

27. Erol F, Turk G. Assessing the caring behaviours and occupational professional attitudes of nurses. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(6):783-7. [Link]

28. Burtson PL, Stichler JF. Nursing work environment and nurse caring: relationship among motivational factors. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(8):1819-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05336.x]

29. Mohammadi M. Relationshipe between professional quality of life and caring ability among critical care nurses of teaching hospitals affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences [Dissertation]. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2012. [Persian] [Link]

30. Trumello C, Bramanti SM, Ballarotto G, Candelori C, Cerniglia L, Cimino S, et al. Psychological adjustment of healthcare workers in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences in stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction between frontline and non-frontline professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8358. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17228358]

31. Mohammadi M, Peyrovi H, Mahmoodi M. The relationship between professional quality of life and caring ability in critical care nurses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(5):273-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/DCC.0000000000000263]

32. Al Ma'mari Q, Sharour LA, Al Omari O. Fatigue, burnout, work environment, workload and perceived patient safety culture among critical care nurses. Br J Nurs. 2020;29(1):28-34. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjon.2020.29.1.28]

33. Kim C, Lee Y. Effects of compassion competence on missed nursing care, professional quality of life and quality of life among Korean nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(8):2118-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13004]

34. Momenifar F, Raji A, Jafarnezhadgero A. A comparative study of professional ethics, depression, anxiety and stress in athletic and non-athletic nurses during COVID-19. Sci J Rehabil Med. 2021;10(4):768-79. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/SJRM.10.4.12]

35. Ruiz‐Fernández MD, Ramos‐Pichardo JD, Ibáñez‐Masero O, Carmona‐Rega MI, Sánchez‐Ruiz MJ, Ortega‐Galán ÁM. Professional quality of life, self‐compassion, resilience, and empathy in healthcare professionals during COVID‐19 crisis in Spain. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44(4):620-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nur.22158]

36. Pashib M, Abbaspour S, Tadayyon H, Khalafi A. Quality of professional life among Nurses of hospitals in Torbat Heydariyeh City in 2016. J Torbat Heydariyeh Univ Med Sci. 2016;4(1):36-41. [Persian] [Link]

37. Ruiz-Fernández MD, Pérez-García E, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Quality of life in nursing professionals: Burnout, fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1253. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17041253]

38. Lluch-Sanz C, Galiana L, Vidal-Blanco G, Sansó N. Psychometric properties of the self-compassion scale-short form: study of its role as a protector of Spanish nurses professional quality of life and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Rep. 2022;12(1):65-76. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nursrep12010008]

39. Darvehi F, Zoghi Paidar M, Yarmohammadi vasel M, Imani b. The impact of mindful self-compassion on aspects of professional quality of life among nurses. Clin Psychol Stud. 2019;9(34):89-108. [Persian] [Link]

40. Roney LN. Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among emergency department registered nurses [Dissertation]. New Haven, Connecticut: Southern Connecticut State University; 2010. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |