Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 593-602 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Adeli M, Moghaddam-Banaem L, Shahali S, Ghandi N. Changes in Sexual Life in Women with Genital Warts: A Qualitative Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :593-602

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61529-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61529-en.html

1- Department of Reproductive Health and Midwifery, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

2- “Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine” and “Autoimmune Bullous Diseases Research Center, Razi Hospital”, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine” and “Autoimmune Bullous Diseases Research Center, Razi Hospital”, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 790 kb]

(3925 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2009 Views)

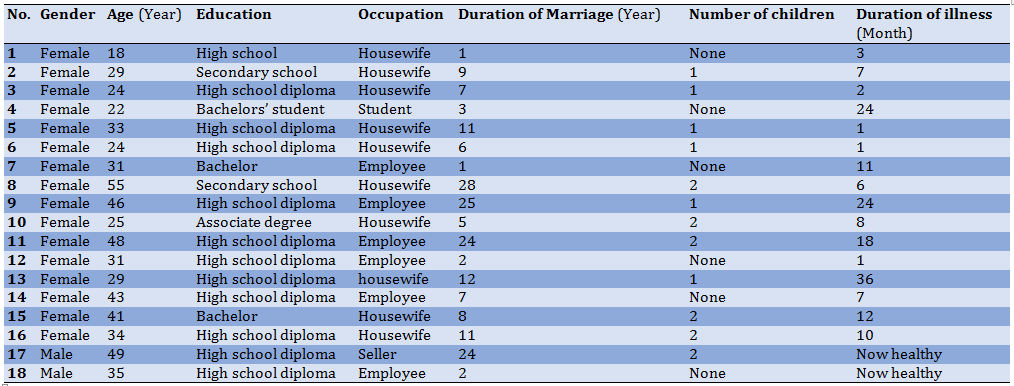

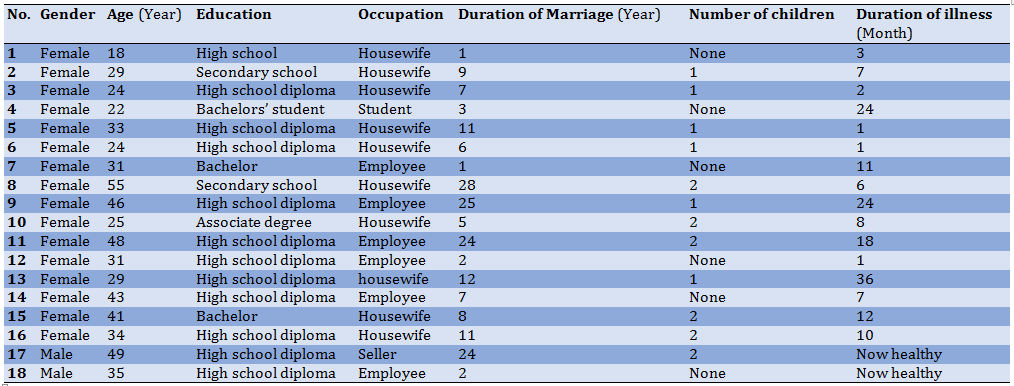

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of the participants

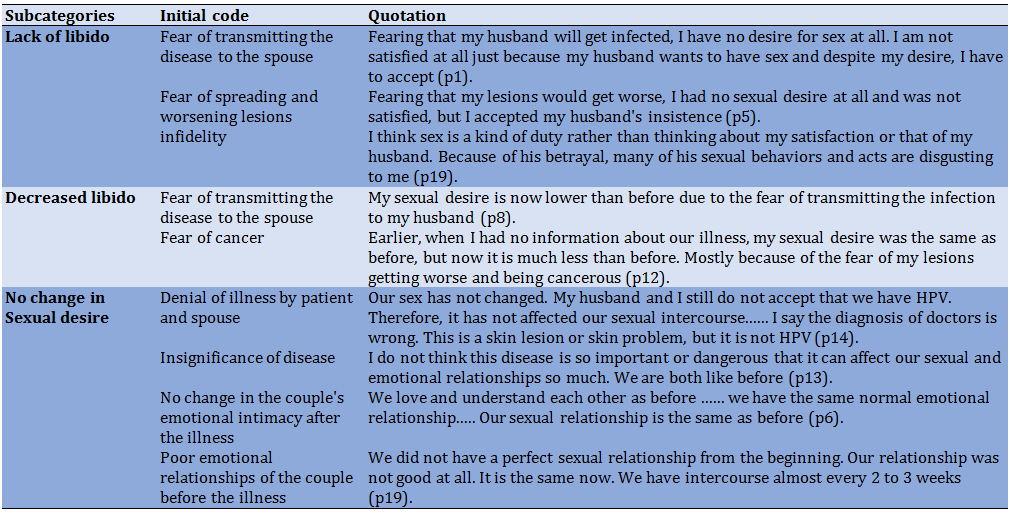

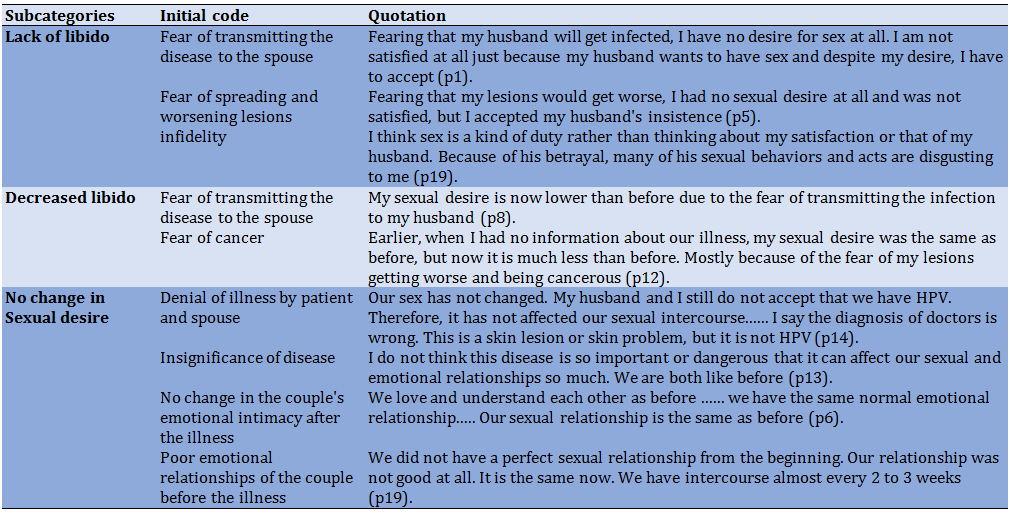

Table 2) Abstraction of a category of changes in the patient and spouse desire from a semantic unit

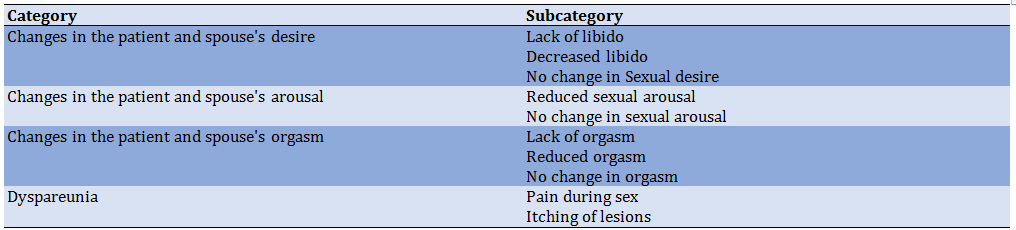

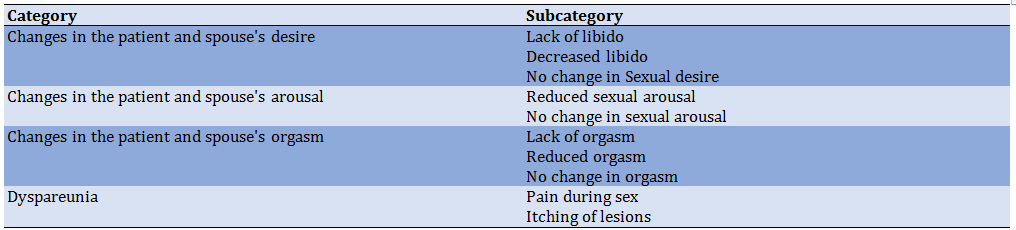

Table 3) Instability in sexual function theme abstraction process

The instability in sexual function theme, which was extracted from data from the experiences of women with genital warts states that genital warts have a significant impact on some aspects of sexual function in patients. Couples were exposed to this phenomenon and specialists were aware of it in their patients.

Changes in the patient and spouse's desire

Genital warts can affect this aspect of sexual function so most women with genital warts have reported a decrease in their sexual desire after infection:

“I did not have any sexual desire at all and I was not satisfied, but I accepted my husband's wishes and insistence” (p5).

Sometimes the decrease in sexual desire of the patient causes a change in some of her sexual behaviors. The purpose of this change in sexual behaviors is to reduce the sexual desire of the husband and reduce the demand for sex by the husband. In this regard, a participant said that: “For my husband to come to me demand less for sex, I no longer wear clothes like before ... I wore revealing and short clothes at home. I have always loved beauty, but now I do not dress like that anymore. Although it is difficult for me to wear pants and clothes, it has been very effective in reducing my husband's sexual desire” (p5).

Decreased libido in patients mostly occurs early in the disease, which in most cases improves over time. Mental conflict, confusion, and restlessness which are the results of recognizing the disease and its complications have been mentioned as the most important reasons for decreased libido.

“I was very upset for only about 20 days and my mind was busy so I did not want to have sex during that time. Although at that time we did not have full sexual intercourse. But I did not want the same superficial intercourse” (p4).

Conversely, sometimes the passing of time increases patients' awareness and information about genital warts, resulting in increased fear and anxiety. This increase in awareness indirectly reduces a person's sexual desire. For example, one of these concerns is the fear of spreading lesions and cancer, which affects sexual desire.

“Earlier, when I had no information about my illness, my sexual desire was the same as before, but now my sexual desire is much less. Mostly because of the fear that my lesions will get worse and that I will get cancer” (p12).

Fear of transmitting the disease to the spouse is another reason for the decrease in the patient's sexual desire.

“Now my sexual desire is less than before due to the fear of transferring warts to my husband” (p8).

Fear of infidelity is also one of the main concerns of these patients, which harms women's sexual desire. For example, an infectious disease specialist says: “Another problem of these women is that they think their husband has committed infidelity. This hurts their sexuality. They no longer want to have sex with their husbands” (p15).

Having sex with reluctance and coercion is another concern of patients. In some cases, reluctance and aversion to sex occur as a result of infidelity, and the patient states that she has to have sex because of obedience and sexual duty, and this is annoying for her.

“I think sex is a duty so I do not think about myself or my husband. I just want to show my fidelity. ... I do not like sex with my husband at all (p19).

Despite the decrease in sexual desire in patients, they stated that genital warts did not affect their husbands' sexual desire. In some cases, husbands have been concerned about the transmission of genital warts from the patient to themselves, but this concern has not affected the husband's sexual desire.

“I also have those worries of my wife. I am afraid of getting worse or worrying about the transfer of warts, but this has not affected my sexual desire” (p22).

In some cases, genital warts have not had a significant effect on reducing the sexual desire of the patient and the spouse.

“We are like before in terms of sexual desire, just as my wife said, we observe a series of things” (p21).

Change in the number of sexual intercourse is one of the most obvious changes in the sexual function of patients so most patients spoke about a decrease in the number of sexual intercourse following genital warts:

“Before the disease, we had sex once or twice a week, but now it occurs once a month” (p3).

Changes in the patient and spouse's arousal

Another aspect of sexual function found to be affected by genital warts in the present study is sexual arousal, as some patients have expressed that genital warts have caused a reduction in their sexual arousal.

“Sexual arousal is very low in me. It is only the first 5 seconds that I get aroused, after that I cannot and do not want to continue but I was not like this at all before the illness” (p1).

Concerns about the spread of lesions or recurrence of lesions following sexual intercourse were another reason for the decrease in sexual arousal in affected women.

“I think the stress and fear of spreading the lesions or the recurrence of the lesions during sexual intercourse have caused us not to experience arousal and orgasm as before” (p11).

Sometimes this concern of patients is transmitted to their husbands and indirectly affects their sexual arousal. For example, the husband of one of the patients points out that:” Well, this disease reduces the quality of arousal and orgasm. It's mostly because of my wife's worries. My wife is afraid that her lesions will get worse and this will affect me. I'm sorry to say, but during sex, my mind is constantly on the issue of warts not recurring or getting worse. This negatively affects my orgasm and arousal” (p21).

Data analysis showed that suspicion of infidelity and focus on how the disease has occurred can indirectly reduce the sexual arousal of infected women.

“For me, sexual arousal and orgasm are not the same as before and have gotten worse, and the reason is the suspicion of my husband's infidelity” (p20).

Some patients also experience sexual arousal as before and report that the disease did not affect their sexual arousal.

“I do not think this disease is so important or dangerous that it can affect our sexual function so much. My husband and I are the same as before” (p13).

Changes in the patient and spouse's orgasm

Orgasm has also been considered an aspect of sexual function and patients' experience in this field has been recorded. In this regard, some patients report that having genital warts has reduced their orgasms; they mention different reasons for this experience. For example, one participant states that the fear of transmitting the disease to the spouse causes them not to experience orgasm as in the past.

“Now that I have genital warts, I have no sexual feelings and I cannot orgasm because I am afraid of transmitting the disease to my husband” (p1).

It seems that incorrect information and perceptions and lack of sufficient sexual knowledge and skills play an important role in patients not experiencing orgasm. As one participant states that after the infection, due to not having sexual intercourse, the experience of orgasm is not possible or the quality of orgasm had decreased. In fact, she considered the experience of orgasm to be subject to sexual intercourse with penetration.

“Now my orgasm and arousal are not as good as before and I am getting tired of this situation. In general, I do not care much about reaching orgasm because I think it will not occur. For women, penetration plays an important role in orgasm. I know that you can reach orgasm with foreplay and superficial sex, but its quality is definitely not like perfect sex, so in these circumstances, reaching orgasm is less important to me” (p6).

Another participant states that after having had genital warts for several months, she had only had superficial sex and only reached the stage of sexual arousal, but never experienced orgasm. She also believes that the experience of orgasm in women is possible only with penetration.

Suspicion of infidelity and focus on how the disease occurred can indirectly reduce the orgasm of infected women.

“For me, sexual arousal and orgasm are not the same as before and have gotten worse, and the reason is my suspicion of my husband” (p20).

Stress and anxiety about the spread or recurrence of lesions after sexual intercourse were also mentioned as other reasons for reducing the experience of orgasm in patients.

“I think that the same stress and fear of spreading lesions or recurrence of lesions during sexual intercourse has caused me and my husband not to experience arousal and orgasm as before” (p11).

Changing sexual behaviors following genital warts that are not acceptable to husbands is another reason for the reduced quality of orgasm in the husbands of infected women. For example, not having sex with penetration in some men caused dissatisfaction and reduced sexual pleasure. For this reason, infected women are concerned about this issue and pay more attention to sexual pleasure in their husbands, and this in itself causes a lack of attention to sexual satisfaction and the experience of orgasm in patients.

“My husband also has ejaculation and orgasm most of the time, but he does not like this form of orgasm (without penetration), but now he has accepted that we should continue the same procedure until our treatment is completed. My biggest concern is getting my husband to orgasm, and I try my best to please my husband and make him orgasm. if we had complete sex, I did not have this worry and I was sure that he would finally reach orgasm” (p6).

Although changes in couples' sexual behaviors due to genital warts, reduced orgasm, and sexual satisfaction in some men, rarely this change in behaviors was pleasant for some husbands and improved orgasms. For example, a participant states the fact that he was forced to use a condom during sex, calmed him and reduced his worries about unwanted pregnancies, resulting in a better orgasm.

“My husband says that now that we have to use a condom because of genital warts, I am much more comfortable because we also prevent unwanted pregnancies. That is why I experience a better orgasm” (p13).

In most cases, reduced orgasm occurs only in infected women, and sexual arousal and orgasm in these women's husbands are the same as before and do not change.

“I do not think genital warts have affected my husband's arousal or orgasm. It is the same as before” (p8).

Some patients experience orgasms as they did before, and reported that the disease did not affect their sexual function.

“I do not think the disease has an effect. Arousal and orgasm are the same as before for me” (p13).

Dyspareunia

Pain during sexual intercourse is another aspect of sexual function that few patients experience and report. According to the participants, this pain seems to have more of a psychological root because it is experienced by patients who, after learning about the disease, especially in the first days, have a lot of stress and anxiety and do not have peace of mind, while none of the patients complained about pain in the area of the lesions, or experienced this pain before the diagnosis.

“I have a lot of pain. In such a way that my abdomen and pelvis ache during sex so that even my tears come and I do not want our sex to continue ... Exactly since I was informed about our illness, I had pain in our last two intercourses... I think because I think a lot, this pain also has a mental and intellectual aspect, that is, my worries caused it” (p1).

More patients complained of itchy lesions, with some reporting that itching caused the lesions to become noticeable. Sometimes these itches are reported as horrible and indescribable. Also, patients' experience shows that scratching and injuring the lesions leads to the spread of the lesions. Itching of the lesions in some cases reduced the number of sexual intercourse and sexual desire. Therefore, it hurts sexual function.

“The lesions are very itchy. So severe that sometimes due to excessive scratching, the lesions become bloody. For this reason, my sexual desire has decreased a lot and the number of our sexual intercourse has also decreased” (p10).

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that in most participants, genital warts (GWs) had a negative effect on sexual life. In this regard, many studies have confirmed that GWs, directly and indirectly, cause sexual dysfunction in patients [20, 30-32]. Changes in sexual life, which are extracted from the experiences of women with genital warts, couples exposed to this phenomenon, and specialists related to these patients, indicate that GWs have a significant effect on different aspects of sexual function in patients. The results of the studies are in line with the findings of the present study; they also confirmed that GWs can cause disorders in different aspects of sexual function including libido, arousal, orgasm, pain, and sexual satisfaction. They also confirmed that these changes were more pronounced in the domains of libido, and the number of sexual intercourses [20, 30, 31]. On the other hand, the results of the study by Tas et al. conducted on 100 refugees in Turkey reported that GWs cannot change the prevalence of sexual disorders in refugees [33]. Perhaps one of the most important reasons for the inconsistency of their finding with other studies is the difference in the study population, which was immigrants with GWs. It is very important to keep in mind that different socio-cultural and ideological contexts or deteriorating living conditions of such patients may affect life priorities, understanding of the quality of life, health expectations, self-assessment of diseases, and even the severity of sexual and psychological effects of GWs. Thus, the lack of awareness of refugees about this disease, difficult living conditions, and less importance of GWs for them should be considered.

Also, in a study by Dominiak et al. in which the sexual function of women with normal cervical cytology, borderline nuclear malformations, CIN 1, 2, 3, VIN 2, 3, GWs, and history of GWs in healthy women were compared in the general British population; sexual dysfunction was reported only in the VIN group. One of the reasons the researchers cited this finding is the age difference between the groups. Most people with VIN are in a higher age range, while most women with GWs are younger. Therefore, the effect of age on sexual function should not be ignored [34].

As mentioned, the findings of the present study show the negative effects of GWs on all aspects of sexual function, one of which is sexual desire, so most women with genital warts complained of decreased libido after infection. Decreased libido in patients occurs early in the disease, which in most cases improves over time. Mental conflict, confusion, and restlessness that are induced because of recognizing the disease and its complications have been mentioned as the most important reasons for this phenomenon. Conversely, sometimes the passing of time increases patients' awareness and information about GWs, resulting in increased fear and anxiety. This increase in awareness indirectly reduces a person's sexual desire. For example, one of these concerns is the fear of spreading lesions, and getting cancer, which affects sexual desire. Other concerns of these patients that can be mentioned as reasons for the reduced sexual desire include fear of transmitting the disease to their spouse, fear, and suspicion of infidelity, having sex with reluctance, and coercion. In some cases, reluctance and aversion to sexual intercourse occur because of infidelity, and the patient states that she engages in sexual intercourse solely for the sake of sexual obedience and duty, and this is annoying for her. Despite the decrease in sexual desire in patients, GWs did not affect the sexual desire of the husbands of the affected women.

In a study by Campaner et al. that compared the sexual psychological effects of GWs on 29 women with those of 46 women with CIN 2, 3, the findings showed that 72.4% of GWs patients suffered from decreased libido [31]. A study by El-esawy et al. on 50 married women with GWs showed that women's sexual function decreased in domains of libido, arousal, orgasm, sexual pain, sexual moisture, and sexual satisfaction. Among these, decreased libido was more common and prominent [20]. The study by Escalas et al., which examined the quality of life in people with HPV, also reported that 72% of people with HPV had decreased libido (or lack of libido), 47% of which experienced a decrease in sexual desire for a complete year [18]. A qualitative study by Jeng et al. to investigate the effects of HPV on marital relationships in 20 women with high-risk HPV in Taiwan found that half of the patients had sexual problems, the most important of which was decreased libido and decreased number of sexual intercourses [35]. Thus, the studies [20, 22, 30] are consistent with the findings of the present study, while the study of Tas et al. suggested that GWs in immigrants in Turkey did not change the sexual desire of patients; the most probable reasons for this discrepancy have already been explained [33]. Also, a cross-sectional study by Parkpinyo et al. showed that although GWs caused sexual dysfunction in other sexual aspects, there was no statistically significant difference in the aspect of libido [22]. Therefore, the studies on the effect of GWs on the libido of patients [22, 33] are not consistent with the findings of the present study.

Another aspect of sexual function that is affected by GWs is sexual arousal, which according to the findings of the present study can be reduced in patients. Concerns about the spread of lesions, or recurrence of lesions following sexual intercourse are among the reasons for the decrease in sexual arousal in women. Sometimes this concern is passed on to spouses and indirectly affects their sexual arousal. The results of studies also reported that the most important concerns of women with GWs and HPV are fear of transmitting the disease to a sexual partner or husband, worsening of the lesions, or recurrence of lesions through sexual intercourse [19, 36, 37]. Also, suspicion of infidelity, and focus on how they got the disease can also indirectly reduce the sexual arousal of infected women. Similar studies [38, 39] confirmed that after being diagnosed with HPV, some women either rejected it or reluctantly accepted it. A few women reported non-sexual issues as the route of infection transmission. Many of them suspected their husband, or sexual partner as the source of the infection.

In contrast to most affected women who reported a decrease in sexual arousal, some patients also experienced sexual function and arousal as before GWs and reported that the disease did not affect their sexual function. in this regard, the results of the studies [2, 22, 30] are consistent with the results of the present study. While Tas reported that GWs did not affect any aspects of immigrants' sexual function [33].

Orgasm is another aspect of sexual function that is affected by GWs, so most women with GWs complain of reduced orgasms. It seems that incorrect information and perceptions, and lack of sufficient sexual knowledge and skills play important roles in patients not experiencing orgasm. Some women think that after the infection, due to not having sex with penetration, the experience of orgasm is not possible, or the quality of orgasm will be lower. The experience of orgasm is considered subject to sexual intercourse with penetration. On the other hand, suspicion of infidelity and focusing on how they got the disease can indirectly reduce the orgasm of infected women.

Emotional stress and concern about the spread or recurrence of lesions following sexual intercourse are other causes of decreased orgasm experience. Sometimes the worries and stress of patients are passed through to spouses and reduce the quality of orgasm in spouses. Changing sexual behaviors following GWs, which is not acceptable by husbands, is another reason for the decrease in the quality of orgasm in the husbands of infected women. For example, having sex without penetration in some men causes dissatisfaction and reduced sexual pleasure. For this reason, infected women are concerned about this issue and pay more attention to the sexual pleasure of their husbands, and this in itself causes a lack of attention to sexual satisfaction and the experience of orgasm in women. Paradoxically, in a few cases, this behavior change is pleasurable for some husbands and improves orgasm. Sometimes the obligation to use a condom during sex calms and reduces the husbands' worries about unwanted pregnancy, as a result, they experience a better orgasm. In most cases, reduced orgasm occurs only in infected women, and arousal and orgasm in the husbands of these women are the same as in the past and do not change. Finally, a small number of patients experience orgasm as they did before having GWs, and reported that the disease did not affect their sexual function.

Kazeminejad et al. also reported that 70% of patients with genital warts suffer from decreased sexual quality and orgasm [32]. The results of the study by Jeng et al. also showed that 68% of HPV patients experienced reduced orgasm, 19% were rejected by their sexual partner, and 71% of patients reported that they could not approach a new partner [35]. Campaner et al. in a study that evaluated and compared the psychological effects of sex in the two groups of patients with GWs and CIN2,3, showed that 57.1% complained of reduced orgasm [31]. El-esawy, Nahidi, and Parkpinyo also agreed with the findings of the present study in this field and confirmed that GWs can reduce orgasm in patients [20, 22, 30]. While the results of a study do not agree with the findings of the present study [33].

Pain during sexual intercourse is another aspect of sexual function that few patients experience and report. It seems that this pain has more of a psychological root because it is experienced by patients who, after learning about the disease, especially in the first days, have a lot of stress and anxiety, do not have peace of mind, and none of them complained of pain from the lesions, nor had experienced pain during intercourse before the diagnosis of GWs. Consistent with the results of the present study, studies [20, 22, 30] also reported that GWs can increase pain disorders during sexual intercourse. While Tas reported that genital warts did not affect this aspect of the sexual function of infected migrants [33].

Also, in the present study, some patients complained of itching of the lesions, so some of them reported that this itching had caused them to notice and recognize the lesions. Sometimes these itches were reported as terrible and indescribable. Patients experience also showed that scratching and injuring the lesions led to the spread of lesions. Sometimes the itching of the lesions was so intolerable for the patients that it disrupted their presence in public. It is possible that the itching of the lesions, as well as the experience of pain during sexual intercourse in some cases, has a psychological cause. The results of the present study showed that the itching of the lesions can also reduce sexual desire and the number of sexual intercourse. It should be noted that no similar study was found in this field to compare the results.

The selection of participants from one hospital was one of the limitations of this study. However, because this hospital is the only public dermatology hospital, and the main dermatology center in Tehran, many specialists refer patients with GWs to this center for treatment.

Conclusion

This study revealed the perceptions and experiences of women with GWs about sexual function and changes in their sexual life, which are often not expressed in quantitative studies. The results showed that GWs have significant negative effects on various aspects of female sexual function. It seems that recognizing women's sexual dysfunction after getting GWs may help healthcare professionals and patients to take effective and practical measures to improve their sexual function and health.

Acknowledgments: This study was part of a reproductive health Ph.D. dissertation at the Faculty of Medicine, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. We sincerely thank Razi Hospital officials who allowed the cooperation, and all participants who kindly gave their precious time.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tarbiat Modares University (IR.MODARES.REC.1397.100).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Adeli M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (50%); Moghaddam-Banaem L (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Shahali Sh (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Ghandi N (Forth Author), Introduction Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: It was funded by Tarbiat Modares University.

Full-Text: (1255 Views)

Introduction

Genital warts (GWs) are common complications of human papillomavirus (HPV) [1], which are benign lesions caused by epidermal proliferation by the virus [2]. HPV infection is one of the most important Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), and its prevalence is increasing all over the world [3]. Over 130 different types of this virus have been identified [4] Although many HPV infections are clinically silent, they are divided into low-risk and high-risk categories [5, 6]. Most HPVs are low risk; types 6 and 11 cause cervical lesions with low malignancy potential, pharyngeal/ oral lesions, and GWs [6-8]. In a review study that Patel et al. conducted in 2013, the annual prevalence of GWs in the world is generally reported in men and women to be 160-289 per 100,000 [9, 10]. The age group at peak incidence of GWs in men is 25-29 years old and in women is 24-20 years old [11-13]. In Iran, accurate information on the prevalence of GWs is not available, while the diagnosis of GWs has been reported to be mostly among people aged 20-30 years old [14].

The most common factors affecting the incidence of GWs include: age, sex, level of education, race, marital status, age at first sexual contact, new sexual partner, number of sexual partners, condom use, smoking, family history, socioeconomic status, other sexually transmitted infections, oral contraceptive pills, and alcohol use; some of which have been confirmed and some are still under discussion [10, 15-17].

According to studies, HPV and GWs have many physical and psychological effects on patients. Initial reactions of patients include anger, depression, isolation, shame, and guilt [18]. GWs may reduce sexual life, self-image, self-esteem, and quality of life by changing emotions, and daily activities, causing pain and discomfort, anxiety, and depression [19]. Almost all studies confirm that GWs threaten people's sexual health and cause obvious changes in their sex life.

Female sexual function is a four-step response cycle that includes libido, sexual arousal, orgasm, and rest [20, 21]. Sexually transmitted infections can threaten a couple's sexual function. GWs directly affect women's sexual function, and they not only cause pain and discomfort for patients but also reduce sexual desire [22]. Lack of sexual satisfaction causes physical and mental stress. A study in Australia reported that 88% of men and 80% of women believe that healthy sex is very effective in improving the sense of vitality [23]. Sexual dysfunction can lead to a growing rate of divorce, which is true in Iran as well. The findings show that 50-60% of divorces are because of problems in the couple's sexual relations [24, 25]. Many of these problems are due to a lack of awareness and a lack of sexual skills [26].

Unfortunately, there are few studies about the changes in the sexual life of women with GWs. Also, no qualitative studies were found in this field. Considering the increasing prevalence of GWs among women and their dire consequences on a couple's sexual function, and that qualitative studies, by deeply discovering the participants' experiences, provide more and better information about problems, this study was conducted with a qualitative approach to explore women's perception and experience of sexual function following genital warts.

Participants and Methods

This study was qualitative, with a conventional content analysis approach, and conducted from January 2019 to February 2020 in the dermatology clinic of Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran. To select samples with rich experiences, the women or couples who had the experience of living with genital warts were selected from the dermatology clinic of Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran by using purposeful sampling. The inclusion criteria were: age of at least 18 years old, having sexual activity, having genital warts diagnosed by the gynecologist or dermatologist or infectious diseases specialist, and having no history of genital malignancy.

Data collection was performed from January 2019 to February 2020 using unstructured, in-depth individual interviews. According to the participant's preference, all interviews were conducted in a private room in the Dermatology Clinic of Razi Hospital in Tehran (Dermatology Hospital). Before the interview, the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of information and recording of interviews were explained to them, and if they agreed to participate, their written consent to enter the study was obtained. If the patient attending the dermatology clinic was eligible, her consent was obtained, and then the appropriate time and place for the interview were determined with the opinion of the participant.

Before data collection and after approving the proposal in the research council of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, the study was approved by the ethics committee of Tarbiat Modares University, and permission to enter the clinical field was obtained from relevant hospital officials. All ethical principles in research such as obtaining informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, and participants' authority to leave the study were undertaken. There were no withdrawals from the study by any of the participants, before or during the interviews. At the beginning of the interviews, simple general questions were asked to make the researcher more familiar with the participants and create a cordial atmosphere. Then questions were guided towards open, more specific questions such as” How the diagnosis and treatment of genital warts have affected your sex life?”. To get deeper information and clarify the concept under study, in-depth questions based on the information provided by the participant were asked, such as: “What do you mean?” Or “Please explain more about this”, “Can you explain more what you mean with an objective example?”. The Duration of each interview varied between 30 and 100 minutes (average 60 minutes). The first author audio-recorded all interviews with the consent of the participants. Then word by word transcription along with mentioning non-verbal gestures and postures was implemented and typed in Word software. The interview process was evaluated and critiqued by the second and third authors of the article, who are experts in reproductive health and qualitative research. In addition to the interview, field notes [27] were used in the data collection process.

Simultaneously, the analysis was performed using a conventional qualitative content analysis approach according to Graneheim & Lundman's steps [28]. The steps of the approach were as follows: First, the researcher read the typed texts several times to get acquainted with the text of the data, and after immersing in the data, the storyline was identified. After determining the semantic units of phrases, sentences, and paragraphs, the initial codes were extracted. Similar primary codes were grouped into a subcategory and similar subcategories into main categories (this process of category extraction from textual data. Also, some subcategories were re-coded and renamed. Finally, the theme was extracted from the main categories. All extracted codes and categories were reviewed and approved by the second and third authors of this article.

Four Lincoln & Guba criteria were used to ensure the robustness of the findings [27, 29]. For the credibility of the findings, all the extracted codes from the two interviews with the participants were checked and corrected if necessary (Member check). Data collection and analysis took more than a year, and the first author had a prolonged engagement with the study subject matter. In data collection, in addition to interviewing women with genital warts, their husbands and specialists were also interviewed (data triangulation). In addition to the interview, observation and field notes were used (triangulation method). To confirm the findings' ability, all the extracted texts, codes, and categories were reviewed and approved by the second and third authors of this article (peer check) and two faculty members outside the research team (faculty check). For dependability, the steps and process of the research were recorded and reported as accurately and step-by-step as possible (Audit trial). We tried to include a variety of participants in terms of age, education, occupation, duration of the marriage, and duration of illness (maximum variation), which in addition to credibility also contributes to transferability.

Findings

In order to increase the accuracy of the data, we tried to interview women with genital warts who had the maximum variation in age, education, occupation, duration of marriage, as well as the duration of illness. Their demographic characteristics varied in terms of education from middle school to bachelor's degree, duration of marriage from 1 to 28 years, duration of illness from 1 month to 3 years, and age from 18 to 55 years. Demographic characteristics of the spouses of these patients also include the average age of 42 years, the average duration of marriage of 13 years, and the level of high school education (Table 1).

After conducting 23 interviews with 18 participants about understanding and experiencing sexual function following genital warts, a total of 224 initial codes were extracted. The central theme of “instability in sexual function” was abstracted which includes 4 main categories: “Changes in the patient and spouse desire “, “Changes in the patient and spouse arousal”, and “Changes in the patient and spouse orgasm “and” dyspareunia”.

Genital warts (GWs) are common complications of human papillomavirus (HPV) [1], which are benign lesions caused by epidermal proliferation by the virus [2]. HPV infection is one of the most important Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), and its prevalence is increasing all over the world [3]. Over 130 different types of this virus have been identified [4] Although many HPV infections are clinically silent, they are divided into low-risk and high-risk categories [5, 6]. Most HPVs are low risk; types 6 and 11 cause cervical lesions with low malignancy potential, pharyngeal/ oral lesions, and GWs [6-8]. In a review study that Patel et al. conducted in 2013, the annual prevalence of GWs in the world is generally reported in men and women to be 160-289 per 100,000 [9, 10]. The age group at peak incidence of GWs in men is 25-29 years old and in women is 24-20 years old [11-13]. In Iran, accurate information on the prevalence of GWs is not available, while the diagnosis of GWs has been reported to be mostly among people aged 20-30 years old [14].

The most common factors affecting the incidence of GWs include: age, sex, level of education, race, marital status, age at first sexual contact, new sexual partner, number of sexual partners, condom use, smoking, family history, socioeconomic status, other sexually transmitted infections, oral contraceptive pills, and alcohol use; some of which have been confirmed and some are still under discussion [10, 15-17].

According to studies, HPV and GWs have many physical and psychological effects on patients. Initial reactions of patients include anger, depression, isolation, shame, and guilt [18]. GWs may reduce sexual life, self-image, self-esteem, and quality of life by changing emotions, and daily activities, causing pain and discomfort, anxiety, and depression [19]. Almost all studies confirm that GWs threaten people's sexual health and cause obvious changes in their sex life.

Female sexual function is a four-step response cycle that includes libido, sexual arousal, orgasm, and rest [20, 21]. Sexually transmitted infections can threaten a couple's sexual function. GWs directly affect women's sexual function, and they not only cause pain and discomfort for patients but also reduce sexual desire [22]. Lack of sexual satisfaction causes physical and mental stress. A study in Australia reported that 88% of men and 80% of women believe that healthy sex is very effective in improving the sense of vitality [23]. Sexual dysfunction can lead to a growing rate of divorce, which is true in Iran as well. The findings show that 50-60% of divorces are because of problems in the couple's sexual relations [24, 25]. Many of these problems are due to a lack of awareness and a lack of sexual skills [26].

Unfortunately, there are few studies about the changes in the sexual life of women with GWs. Also, no qualitative studies were found in this field. Considering the increasing prevalence of GWs among women and their dire consequences on a couple's sexual function, and that qualitative studies, by deeply discovering the participants' experiences, provide more and better information about problems, this study was conducted with a qualitative approach to explore women's perception and experience of sexual function following genital warts.

Participants and Methods

This study was qualitative, with a conventional content analysis approach, and conducted from January 2019 to February 2020 in the dermatology clinic of Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran. To select samples with rich experiences, the women or couples who had the experience of living with genital warts were selected from the dermatology clinic of Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran by using purposeful sampling. The inclusion criteria were: age of at least 18 years old, having sexual activity, having genital warts diagnosed by the gynecologist or dermatologist or infectious diseases specialist, and having no history of genital malignancy.

Data collection was performed from January 2019 to February 2020 using unstructured, in-depth individual interviews. According to the participant's preference, all interviews were conducted in a private room in the Dermatology Clinic of Razi Hospital in Tehran (Dermatology Hospital). Before the interview, the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of information and recording of interviews were explained to them, and if they agreed to participate, their written consent to enter the study was obtained. If the patient attending the dermatology clinic was eligible, her consent was obtained, and then the appropriate time and place for the interview were determined with the opinion of the participant.

Before data collection and after approving the proposal in the research council of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, the study was approved by the ethics committee of Tarbiat Modares University, and permission to enter the clinical field was obtained from relevant hospital officials. All ethical principles in research such as obtaining informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, and participants' authority to leave the study were undertaken. There were no withdrawals from the study by any of the participants, before or during the interviews. At the beginning of the interviews, simple general questions were asked to make the researcher more familiar with the participants and create a cordial atmosphere. Then questions were guided towards open, more specific questions such as” How the diagnosis and treatment of genital warts have affected your sex life?”. To get deeper information and clarify the concept under study, in-depth questions based on the information provided by the participant were asked, such as: “What do you mean?” Or “Please explain more about this”, “Can you explain more what you mean with an objective example?”. The Duration of each interview varied between 30 and 100 minutes (average 60 minutes). The first author audio-recorded all interviews with the consent of the participants. Then word by word transcription along with mentioning non-verbal gestures and postures was implemented and typed in Word software. The interview process was evaluated and critiqued by the second and third authors of the article, who are experts in reproductive health and qualitative research. In addition to the interview, field notes [27] were used in the data collection process.

Simultaneously, the analysis was performed using a conventional qualitative content analysis approach according to Graneheim & Lundman's steps [28]. The steps of the approach were as follows: First, the researcher read the typed texts several times to get acquainted with the text of the data, and after immersing in the data, the storyline was identified. After determining the semantic units of phrases, sentences, and paragraphs, the initial codes were extracted. Similar primary codes were grouped into a subcategory and similar subcategories into main categories (this process of category extraction from textual data. Also, some subcategories were re-coded and renamed. Finally, the theme was extracted from the main categories. All extracted codes and categories were reviewed and approved by the second and third authors of this article.

Four Lincoln & Guba criteria were used to ensure the robustness of the findings [27, 29]. For the credibility of the findings, all the extracted codes from the two interviews with the participants were checked and corrected if necessary (Member check). Data collection and analysis took more than a year, and the first author had a prolonged engagement with the study subject matter. In data collection, in addition to interviewing women with genital warts, their husbands and specialists were also interviewed (data triangulation). In addition to the interview, observation and field notes were used (triangulation method). To confirm the findings' ability, all the extracted texts, codes, and categories were reviewed and approved by the second and third authors of this article (peer check) and two faculty members outside the research team (faculty check). For dependability, the steps and process of the research were recorded and reported as accurately and step-by-step as possible (Audit trial). We tried to include a variety of participants in terms of age, education, occupation, duration of the marriage, and duration of illness (maximum variation), which in addition to credibility also contributes to transferability.

Findings

In order to increase the accuracy of the data, we tried to interview women with genital warts who had the maximum variation in age, education, occupation, duration of marriage, as well as the duration of illness. Their demographic characteristics varied in terms of education from middle school to bachelor's degree, duration of marriage from 1 to 28 years, duration of illness from 1 month to 3 years, and age from 18 to 55 years. Demographic characteristics of the spouses of these patients also include the average age of 42 years, the average duration of marriage of 13 years, and the level of high school education (Table 1).

After conducting 23 interviews with 18 participants about understanding and experiencing sexual function following genital warts, a total of 224 initial codes were extracted. The central theme of “instability in sexual function” was abstracted which includes 4 main categories: “Changes in the patient and spouse desire “, “Changes in the patient and spouse arousal”, and “Changes in the patient and spouse orgasm “and” dyspareunia”.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 2) Abstraction of a category of changes in the patient and spouse desire from a semantic unit

Table 3) Instability in sexual function theme abstraction process

The instability in sexual function theme, which was extracted from data from the experiences of women with genital warts states that genital warts have a significant impact on some aspects of sexual function in patients. Couples were exposed to this phenomenon and specialists were aware of it in their patients.

Changes in the patient and spouse's desire

Genital warts can affect this aspect of sexual function so most women with genital warts have reported a decrease in their sexual desire after infection:

“I did not have any sexual desire at all and I was not satisfied, but I accepted my husband's wishes and insistence” (p5).

Sometimes the decrease in sexual desire of the patient causes a change in some of her sexual behaviors. The purpose of this change in sexual behaviors is to reduce the sexual desire of the husband and reduce the demand for sex by the husband. In this regard, a participant said that: “For my husband to come to me demand less for sex, I no longer wear clothes like before ... I wore revealing and short clothes at home. I have always loved beauty, but now I do not dress like that anymore. Although it is difficult for me to wear pants and clothes, it has been very effective in reducing my husband's sexual desire” (p5).

Decreased libido in patients mostly occurs early in the disease, which in most cases improves over time. Mental conflict, confusion, and restlessness which are the results of recognizing the disease and its complications have been mentioned as the most important reasons for decreased libido.

“I was very upset for only about 20 days and my mind was busy so I did not want to have sex during that time. Although at that time we did not have full sexual intercourse. But I did not want the same superficial intercourse” (p4).

Conversely, sometimes the passing of time increases patients' awareness and information about genital warts, resulting in increased fear and anxiety. This increase in awareness indirectly reduces a person's sexual desire. For example, one of these concerns is the fear of spreading lesions and cancer, which affects sexual desire.

“Earlier, when I had no information about my illness, my sexual desire was the same as before, but now my sexual desire is much less. Mostly because of the fear that my lesions will get worse and that I will get cancer” (p12).

Fear of transmitting the disease to the spouse is another reason for the decrease in the patient's sexual desire.

“Now my sexual desire is less than before due to the fear of transferring warts to my husband” (p8).

Fear of infidelity is also one of the main concerns of these patients, which harms women's sexual desire. For example, an infectious disease specialist says: “Another problem of these women is that they think their husband has committed infidelity. This hurts their sexuality. They no longer want to have sex with their husbands” (p15).

Having sex with reluctance and coercion is another concern of patients. In some cases, reluctance and aversion to sex occur as a result of infidelity, and the patient states that she has to have sex because of obedience and sexual duty, and this is annoying for her.

“I think sex is a duty so I do not think about myself or my husband. I just want to show my fidelity. ... I do not like sex with my husband at all (p19).

Despite the decrease in sexual desire in patients, they stated that genital warts did not affect their husbands' sexual desire. In some cases, husbands have been concerned about the transmission of genital warts from the patient to themselves, but this concern has not affected the husband's sexual desire.

“I also have those worries of my wife. I am afraid of getting worse or worrying about the transfer of warts, but this has not affected my sexual desire” (p22).

In some cases, genital warts have not had a significant effect on reducing the sexual desire of the patient and the spouse.

“We are like before in terms of sexual desire, just as my wife said, we observe a series of things” (p21).

Change in the number of sexual intercourse is one of the most obvious changes in the sexual function of patients so most patients spoke about a decrease in the number of sexual intercourse following genital warts:

“Before the disease, we had sex once or twice a week, but now it occurs once a month” (p3).

Changes in the patient and spouse's arousal

Another aspect of sexual function found to be affected by genital warts in the present study is sexual arousal, as some patients have expressed that genital warts have caused a reduction in their sexual arousal.

“Sexual arousal is very low in me. It is only the first 5 seconds that I get aroused, after that I cannot and do not want to continue but I was not like this at all before the illness” (p1).

Concerns about the spread of lesions or recurrence of lesions following sexual intercourse were another reason for the decrease in sexual arousal in affected women.

“I think the stress and fear of spreading the lesions or the recurrence of the lesions during sexual intercourse have caused us not to experience arousal and orgasm as before” (p11).

Sometimes this concern of patients is transmitted to their husbands and indirectly affects their sexual arousal. For example, the husband of one of the patients points out that:” Well, this disease reduces the quality of arousal and orgasm. It's mostly because of my wife's worries. My wife is afraid that her lesions will get worse and this will affect me. I'm sorry to say, but during sex, my mind is constantly on the issue of warts not recurring or getting worse. This negatively affects my orgasm and arousal” (p21).

Data analysis showed that suspicion of infidelity and focus on how the disease has occurred can indirectly reduce the sexual arousal of infected women.

“For me, sexual arousal and orgasm are not the same as before and have gotten worse, and the reason is the suspicion of my husband's infidelity” (p20).

Some patients also experience sexual arousal as before and report that the disease did not affect their sexual arousal.

“I do not think this disease is so important or dangerous that it can affect our sexual function so much. My husband and I are the same as before” (p13).

Changes in the patient and spouse's orgasm

Orgasm has also been considered an aspect of sexual function and patients' experience in this field has been recorded. In this regard, some patients report that having genital warts has reduced their orgasms; they mention different reasons for this experience. For example, one participant states that the fear of transmitting the disease to the spouse causes them not to experience orgasm as in the past.

“Now that I have genital warts, I have no sexual feelings and I cannot orgasm because I am afraid of transmitting the disease to my husband” (p1).

It seems that incorrect information and perceptions and lack of sufficient sexual knowledge and skills play an important role in patients not experiencing orgasm. As one participant states that after the infection, due to not having sexual intercourse, the experience of orgasm is not possible or the quality of orgasm had decreased. In fact, she considered the experience of orgasm to be subject to sexual intercourse with penetration.

“Now my orgasm and arousal are not as good as before and I am getting tired of this situation. In general, I do not care much about reaching orgasm because I think it will not occur. For women, penetration plays an important role in orgasm. I know that you can reach orgasm with foreplay and superficial sex, but its quality is definitely not like perfect sex, so in these circumstances, reaching orgasm is less important to me” (p6).

Another participant states that after having had genital warts for several months, she had only had superficial sex and only reached the stage of sexual arousal, but never experienced orgasm. She also believes that the experience of orgasm in women is possible only with penetration.

Suspicion of infidelity and focus on how the disease occurred can indirectly reduce the orgasm of infected women.

“For me, sexual arousal and orgasm are not the same as before and have gotten worse, and the reason is my suspicion of my husband” (p20).

Stress and anxiety about the spread or recurrence of lesions after sexual intercourse were also mentioned as other reasons for reducing the experience of orgasm in patients.

“I think that the same stress and fear of spreading lesions or recurrence of lesions during sexual intercourse has caused me and my husband not to experience arousal and orgasm as before” (p11).

Changing sexual behaviors following genital warts that are not acceptable to husbands is another reason for the reduced quality of orgasm in the husbands of infected women. For example, not having sex with penetration in some men caused dissatisfaction and reduced sexual pleasure. For this reason, infected women are concerned about this issue and pay more attention to sexual pleasure in their husbands, and this in itself causes a lack of attention to sexual satisfaction and the experience of orgasm in patients.

“My husband also has ejaculation and orgasm most of the time, but he does not like this form of orgasm (without penetration), but now he has accepted that we should continue the same procedure until our treatment is completed. My biggest concern is getting my husband to orgasm, and I try my best to please my husband and make him orgasm. if we had complete sex, I did not have this worry and I was sure that he would finally reach orgasm” (p6).

Although changes in couples' sexual behaviors due to genital warts, reduced orgasm, and sexual satisfaction in some men, rarely this change in behaviors was pleasant for some husbands and improved orgasms. For example, a participant states the fact that he was forced to use a condom during sex, calmed him and reduced his worries about unwanted pregnancies, resulting in a better orgasm.

“My husband says that now that we have to use a condom because of genital warts, I am much more comfortable because we also prevent unwanted pregnancies. That is why I experience a better orgasm” (p13).

In most cases, reduced orgasm occurs only in infected women, and sexual arousal and orgasm in these women's husbands are the same as before and do not change.

“I do not think genital warts have affected my husband's arousal or orgasm. It is the same as before” (p8).

Some patients experience orgasms as they did before, and reported that the disease did not affect their sexual function.

“I do not think the disease has an effect. Arousal and orgasm are the same as before for me” (p13).

Dyspareunia

Pain during sexual intercourse is another aspect of sexual function that few patients experience and report. According to the participants, this pain seems to have more of a psychological root because it is experienced by patients who, after learning about the disease, especially in the first days, have a lot of stress and anxiety and do not have peace of mind, while none of the patients complained about pain in the area of the lesions, or experienced this pain before the diagnosis.

“I have a lot of pain. In such a way that my abdomen and pelvis ache during sex so that even my tears come and I do not want our sex to continue ... Exactly since I was informed about our illness, I had pain in our last two intercourses... I think because I think a lot, this pain also has a mental and intellectual aspect, that is, my worries caused it” (p1).

More patients complained of itchy lesions, with some reporting that itching caused the lesions to become noticeable. Sometimes these itches are reported as horrible and indescribable. Also, patients' experience shows that scratching and injuring the lesions leads to the spread of the lesions. Itching of the lesions in some cases reduced the number of sexual intercourse and sexual desire. Therefore, it hurts sexual function.

“The lesions are very itchy. So severe that sometimes due to excessive scratching, the lesions become bloody. For this reason, my sexual desire has decreased a lot and the number of our sexual intercourse has also decreased” (p10).

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that in most participants, genital warts (GWs) had a negative effect on sexual life. In this regard, many studies have confirmed that GWs, directly and indirectly, cause sexual dysfunction in patients [20, 30-32]. Changes in sexual life, which are extracted from the experiences of women with genital warts, couples exposed to this phenomenon, and specialists related to these patients, indicate that GWs have a significant effect on different aspects of sexual function in patients. The results of the studies are in line with the findings of the present study; they also confirmed that GWs can cause disorders in different aspects of sexual function including libido, arousal, orgasm, pain, and sexual satisfaction. They also confirmed that these changes were more pronounced in the domains of libido, and the number of sexual intercourses [20, 30, 31]. On the other hand, the results of the study by Tas et al. conducted on 100 refugees in Turkey reported that GWs cannot change the prevalence of sexual disorders in refugees [33]. Perhaps one of the most important reasons for the inconsistency of their finding with other studies is the difference in the study population, which was immigrants with GWs. It is very important to keep in mind that different socio-cultural and ideological contexts or deteriorating living conditions of such patients may affect life priorities, understanding of the quality of life, health expectations, self-assessment of diseases, and even the severity of sexual and psychological effects of GWs. Thus, the lack of awareness of refugees about this disease, difficult living conditions, and less importance of GWs for them should be considered.

Also, in a study by Dominiak et al. in which the sexual function of women with normal cervical cytology, borderline nuclear malformations, CIN 1, 2, 3, VIN 2, 3, GWs, and history of GWs in healthy women were compared in the general British population; sexual dysfunction was reported only in the VIN group. One of the reasons the researchers cited this finding is the age difference between the groups. Most people with VIN are in a higher age range, while most women with GWs are younger. Therefore, the effect of age on sexual function should not be ignored [34].

As mentioned, the findings of the present study show the negative effects of GWs on all aspects of sexual function, one of which is sexual desire, so most women with genital warts complained of decreased libido after infection. Decreased libido in patients occurs early in the disease, which in most cases improves over time. Mental conflict, confusion, and restlessness that are induced because of recognizing the disease and its complications have been mentioned as the most important reasons for this phenomenon. Conversely, sometimes the passing of time increases patients' awareness and information about GWs, resulting in increased fear and anxiety. This increase in awareness indirectly reduces a person's sexual desire. For example, one of these concerns is the fear of spreading lesions, and getting cancer, which affects sexual desire. Other concerns of these patients that can be mentioned as reasons for the reduced sexual desire include fear of transmitting the disease to their spouse, fear, and suspicion of infidelity, having sex with reluctance, and coercion. In some cases, reluctance and aversion to sexual intercourse occur because of infidelity, and the patient states that she engages in sexual intercourse solely for the sake of sexual obedience and duty, and this is annoying for her. Despite the decrease in sexual desire in patients, GWs did not affect the sexual desire of the husbands of the affected women.

In a study by Campaner et al. that compared the sexual psychological effects of GWs on 29 women with those of 46 women with CIN 2, 3, the findings showed that 72.4% of GWs patients suffered from decreased libido [31]. A study by El-esawy et al. on 50 married women with GWs showed that women's sexual function decreased in domains of libido, arousal, orgasm, sexual pain, sexual moisture, and sexual satisfaction. Among these, decreased libido was more common and prominent [20]. The study by Escalas et al., which examined the quality of life in people with HPV, also reported that 72% of people with HPV had decreased libido (or lack of libido), 47% of which experienced a decrease in sexual desire for a complete year [18]. A qualitative study by Jeng et al. to investigate the effects of HPV on marital relationships in 20 women with high-risk HPV in Taiwan found that half of the patients had sexual problems, the most important of which was decreased libido and decreased number of sexual intercourses [35]. Thus, the studies [20, 22, 30] are consistent with the findings of the present study, while the study of Tas et al. suggested that GWs in immigrants in Turkey did not change the sexual desire of patients; the most probable reasons for this discrepancy have already been explained [33]. Also, a cross-sectional study by Parkpinyo et al. showed that although GWs caused sexual dysfunction in other sexual aspects, there was no statistically significant difference in the aspect of libido [22]. Therefore, the studies on the effect of GWs on the libido of patients [22, 33] are not consistent with the findings of the present study.

Another aspect of sexual function that is affected by GWs is sexual arousal, which according to the findings of the present study can be reduced in patients. Concerns about the spread of lesions, or recurrence of lesions following sexual intercourse are among the reasons for the decrease in sexual arousal in women. Sometimes this concern is passed on to spouses and indirectly affects their sexual arousal. The results of studies also reported that the most important concerns of women with GWs and HPV are fear of transmitting the disease to a sexual partner or husband, worsening of the lesions, or recurrence of lesions through sexual intercourse [19, 36, 37]. Also, suspicion of infidelity, and focus on how they got the disease can also indirectly reduce the sexual arousal of infected women. Similar studies [38, 39] confirmed that after being diagnosed with HPV, some women either rejected it or reluctantly accepted it. A few women reported non-sexual issues as the route of infection transmission. Many of them suspected their husband, or sexual partner as the source of the infection.

In contrast to most affected women who reported a decrease in sexual arousal, some patients also experienced sexual function and arousal as before GWs and reported that the disease did not affect their sexual function. in this regard, the results of the studies [2, 22, 30] are consistent with the results of the present study. While Tas reported that GWs did not affect any aspects of immigrants' sexual function [33].

Orgasm is another aspect of sexual function that is affected by GWs, so most women with GWs complain of reduced orgasms. It seems that incorrect information and perceptions, and lack of sufficient sexual knowledge and skills play important roles in patients not experiencing orgasm. Some women think that after the infection, due to not having sex with penetration, the experience of orgasm is not possible, or the quality of orgasm will be lower. The experience of orgasm is considered subject to sexual intercourse with penetration. On the other hand, suspicion of infidelity and focusing on how they got the disease can indirectly reduce the orgasm of infected women.

Emotional stress and concern about the spread or recurrence of lesions following sexual intercourse are other causes of decreased orgasm experience. Sometimes the worries and stress of patients are passed through to spouses and reduce the quality of orgasm in spouses. Changing sexual behaviors following GWs, which is not acceptable by husbands, is another reason for the decrease in the quality of orgasm in the husbands of infected women. For example, having sex without penetration in some men causes dissatisfaction and reduced sexual pleasure. For this reason, infected women are concerned about this issue and pay more attention to the sexual pleasure of their husbands, and this in itself causes a lack of attention to sexual satisfaction and the experience of orgasm in women. Paradoxically, in a few cases, this behavior change is pleasurable for some husbands and improves orgasm. Sometimes the obligation to use a condom during sex calms and reduces the husbands' worries about unwanted pregnancy, as a result, they experience a better orgasm. In most cases, reduced orgasm occurs only in infected women, and arousal and orgasm in the husbands of these women are the same as in the past and do not change. Finally, a small number of patients experience orgasm as they did before having GWs, and reported that the disease did not affect their sexual function.

Kazeminejad et al. also reported that 70% of patients with genital warts suffer from decreased sexual quality and orgasm [32]. The results of the study by Jeng et al. also showed that 68% of HPV patients experienced reduced orgasm, 19% were rejected by their sexual partner, and 71% of patients reported that they could not approach a new partner [35]. Campaner et al. in a study that evaluated and compared the psychological effects of sex in the two groups of patients with GWs and CIN2,3, showed that 57.1% complained of reduced orgasm [31]. El-esawy, Nahidi, and Parkpinyo also agreed with the findings of the present study in this field and confirmed that GWs can reduce orgasm in patients [20, 22, 30]. While the results of a study do not agree with the findings of the present study [33].

Pain during sexual intercourse is another aspect of sexual function that few patients experience and report. It seems that this pain has more of a psychological root because it is experienced by patients who, after learning about the disease, especially in the first days, have a lot of stress and anxiety, do not have peace of mind, and none of them complained of pain from the lesions, nor had experienced pain during intercourse before the diagnosis of GWs. Consistent with the results of the present study, studies [20, 22, 30] also reported that GWs can increase pain disorders during sexual intercourse. While Tas reported that genital warts did not affect this aspect of the sexual function of infected migrants [33].

Also, in the present study, some patients complained of itching of the lesions, so some of them reported that this itching had caused them to notice and recognize the lesions. Sometimes these itches were reported as terrible and indescribable. Patients experience also showed that scratching and injuring the lesions led to the spread of lesions. Sometimes the itching of the lesions was so intolerable for the patients that it disrupted their presence in public. It is possible that the itching of the lesions, as well as the experience of pain during sexual intercourse in some cases, has a psychological cause. The results of the present study showed that the itching of the lesions can also reduce sexual desire and the number of sexual intercourse. It should be noted that no similar study was found in this field to compare the results.

The selection of participants from one hospital was one of the limitations of this study. However, because this hospital is the only public dermatology hospital, and the main dermatology center in Tehran, many specialists refer patients with GWs to this center for treatment.

Conclusion

This study revealed the perceptions and experiences of women with GWs about sexual function and changes in their sexual life, which are often not expressed in quantitative studies. The results showed that GWs have significant negative effects on various aspects of female sexual function. It seems that recognizing women's sexual dysfunction after getting GWs may help healthcare professionals and patients to take effective and practical measures to improve their sexual function and health.

Acknowledgments: This study was part of a reproductive health Ph.D. dissertation at the Faculty of Medicine, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. We sincerely thank Razi Hospital officials who allowed the cooperation, and all participants who kindly gave their precious time.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tarbiat Modares University (IR.MODARES.REC.1397.100).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Adeli M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (50%); Moghaddam-Banaem L (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Shahali Sh (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Ghandi N (Forth Author), Introduction Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: It was funded by Tarbiat Modares University.

Article Type: Qualitative Research |

Subject:

Sexual Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2022/04/4 | Accepted: 2022/06/27 | Published: 2022/07/24

Received: 2022/04/4 | Accepted: 2022/06/27 | Published: 2022/07/24

References

1. Chan A, Brown B, Sepulveda E, Teran-Clayton L. Evaluation of fotonovela to increase human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and intentions in a low-income Hispanic community. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:615. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13104-015-1609-7]

2. Zhang Y, Jiang S, Lin H, Guo X, Zou X. Application of dermoscopy image analysis technique in diagnosing urethral condylomata acuminata. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2018;93(1):67-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186527]

3. Yu X, Zheng H. Infections after photodynamic therapy in Condyloma acuminatum patients: incidence and management. Environl Sci Pollut Res. 2018:1-6. [Link] [DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.23996]

4. Khopkar US, Rajagopalan M, Chauhan AR, Kothari-Talwar S, Singhal PK, Yee K, et al. Prevalence and burden related to genital warts in India. Viral immunol. 2018;31(5):346-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/vim.2017.0157]

5. Daugherty M, Byler T. Genital wart and human papillomavirus prevalence in men in the United States from penile swabs: results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(6):412-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000761]

6. Hasanzadeh Mofrad M, Jedi L, Ahmadi S. The role of human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccines in prevention of Cervical Cancer, review article. Iranian J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2016;19(21):22-9. [Persian] [Link]

7. Mahdavi S, Kamalinejad M, Emtiazy M, Enayatrad M, Naghshi M. The epidemiologic investigation of genital warts within the females referred to Shahid Sadoughi hospital in Yazd-a case series study. J Community Health Res. 2015;4(3):168-76. [Persian] [Link]

8. Herweijer E, Ploner A, Sparén P. Substantially reduced incidence of genital warts in women and men six years after HPV vaccine availability in Sweden. Vaccine. 2018;36(15):1917-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.097]

9. Patel H, Wagner M, Singhal P, Kothari S. Systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of genital warts. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):39. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-13-39]

10. Taheri R, Bayatani N, Razavi M, Mirmohammadkhani M. Risk factors for genital wart in men. KOOMESH. 2017;19(2):320-6. [Persian] [Link]

11. Bollerup S, Baldur-Felskov B, Blomberg M, Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, Kjaer SK. Significant reduction in the incidence of genital warts in young men 5 years into the danish human papillomavirus vaccination program for girls and women. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(4):238-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000418]

12. Canvin M, Sinka K, Hughes G, Mesher D. Decline in genital warts diagnoses among young women and young men since the introduction of the bivalent HPV (16/18) vaccination programme in England: an ecological analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(2):125-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/sextrans-2016-052626]

13. Park IU, Introcaso C, Dunne EF. Human papillomavirus and genital warts: a review of the evidence for the 2015 centers for disease control and prevention Sex Transm Dis treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61 Suppl 8:S849-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/cid/civ813]

14. Soori T, Hallaji Z, Noroozi-Nejad E. Genital warts in 250 Iranian patients and their high-risk sexual behaviors. Arch Iranian Med. 2013;16(9):518-20. [Link]

15. Akcali S, Goker A, Ecemis T, Kandiloglu AR, Sanlidag T. Human papilloma virus frequency and genotype distribution in a Turkish population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(1):503-6. [Link] [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.1.503]

16. Behzadi P, Behzadi E, Ranjbar R, Saberfar E. Cervical cancer and human papilloma virus (HPV)-viral cervical cancer. MOJ Cell Sci Rep. 2015;2(3):55-8. [Link] [DOI:10.15406/mojcsr.2015.02.00026]

17. Jahdi F, Khademi K, Khoei EM, Haghani H, Yarandi F. Reproductive factors associated to human papillomavirus infection in Iranian woman. J Fam Reprod Health. 2013;7(3):145. [Link]

18. Escalas J, Rodriguez-Cerdeir C, Guerra-Tapia A. Impact of HPV infection on the quality of life in young women. Open Dermatol J. 2009;3:137. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1874372200903010137]

19. Drolet M, Brisson M, Maunsell E, Franco EL, Coutlée F, Ferenczy A, et al. The impact of anogenital warts on health-related quality of life: a 6-month prospective study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(10):949-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182215512]

20. El-esawy FM, Ahmed HM. Effect of genital warts on female sexual function and quality of life: an Egyptian study. Human Androl. 2017;7(2):58-64. [Link] [DOI:10.21608/ha.2017.3919]

21. Aslan E, Fynes M. Female sexual dysfunction. Int Urogynecol Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(2):293-305. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00192-007-0436-3]

22. Parkpinyo N, Chayachinda C, Thamkhantho M. Factors associated with sexual dysfunction in women experiencing anogenital warts at Siriraj hospital. J Med Assoc Thail. 2020;103:359-64. [Link]

23. Zargar Shoushtari S, Afshari P, Abedi P, Tabesh H. The effect of face-to-face with telephone-based counseling on sexual satisfaction among reproductive aged women in Iran. J Sex Mar Ther. 2015;41(4):361-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2014.915903]

24. Parva M, Lotfi R, Nazari MA, Kabir K. The effectiveness of sexual enrichment counseling on sexual assertiveness in married women: a randomized controlled trial. Shiraz E Med J. 2018;19(1):e14552. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/semj.14552]

25. Mahdoodizaman M, Razaghi S, Amirsardari L, Hobbi O, Ghaderi D. The relationship between interpersonal cognitive distortions and attribution styles among divorce applicant couples and its impact on sexual satisfaction. Iranian J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2016;10(3):e5644. [Link] [DOI:10.17795/ijpbs-5644]

26. Farbod E, Ghamari M, Majd MA. Investigating the effect of communication skills training for married women on couples' intimacy and quality of life. SAGE Open. 2014;4(2). [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2158244014537085]

27. Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Link]

28. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x]

29. Zhang Y, Wildemuth B. Qualitative analysis of content. USA: Libraries Unlimited Inc; 2009. [Link]

30. Nahidi M, Nahidi Y, Kardan G, Jarahi L, Aminzadeh B, Shojaei P, et al. Evaluation of sexual life and marital satisfaction in patients with anogenital wart. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2019;110(7):521-5. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.adengl.2018.08.001]

31. Campaner AB, Junior NV, Giraldo PC, Passos MRL. Adverse psychosexual impact related to the treatment of genital warts and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Sex Transm Dis. 2013;2013:264093. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2013/264093]

32. Kazeminejad A, Yazadani Charati J, Rahmatpour G, Masoudzadeh A, Bagheri S. Comparison of quality of life in anogenital warts with control group. Tehran Univ Med J. 2019;76(10):692-8. [Link]

33. Tas B, Kulacaoglu F, Altuntas M. Effects of sociodemographic sexual and clinical factors and disease awareness on psychosexual dysfunction of refugee patients with anogenital warts in Turkey: a cross-sectional study. BiomedRes. 2017;28(12):5601-8. [Link]

34. Dominiak-Felden G, Cohet C, Atrux-Tallau S, Gilet H, Tristram A, Fiander A. Impact of human papillomavirus-related genital diseases on quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing: results of an observational, health-related quality of life study in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1065. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1065]

35. Jeng CJ, Lin H, Wang LR. The effect of HPV infection on a couple's relationship: a qualitative study in Taiwan. Taiwane J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;49(4):407-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1028-4559(10)60090-3]